Abstract

One of the Sustainable Development Goals of the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development is Decent Work and Economic Growth (SDG 8). While the actions suggested to reach this goal target numerous actors in the labor market, such as entrepreneurs running small and medium-sized enterprises, unemployed people, students and young people, persons with disabilities, children and adults forced to work, and migrant workers, these are not the only important groups to focus on. This paper discusses a group receiving less attention: self-employed workers. Through a review of literature and the legislative framework on the social benefits of self-employment across 31 European countries, challenges to the self-employed achieving decent work are identified. The most prominent challenges are that, in many countries, these workers lack social protection against unemployment or accidents at work and that the conditions for their entitlement to social benefits are more demanding than for employees. These constitute impediments to achieving SDG 8‘s goal of “decent work for all”, and SDG 10′s aim to “reduce inequalities”.

1. Introduction

One of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development is Decent Work and Economic Growth (SDG 8), aiming to “promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all” [1]. Actions suggested to achieve this goal target a wide range of actors in the labor market: entrepreneurs running small and medium-sized enterprises, unemployed people, students and young people, persons with disabilities, children and adults forced to work, and migrant workers [2]. While it is important to focus on these categories, a group so far given relatively little consideration is self-employed workers. Nevertheless, many self-employed workers are micro-entrepreneurs who could become employers and, thus, provide work opportunities for unemployed people [3]. Moreover, the number of self-employed workers has grown in recent years [4,5,6], as have the forms of self-employment [7]. This is not least due to technological advancements making online, remote, and freelancing work possible and easier [5,6,7,8,9]. The rise of digital platforms intermediating “the supply of and demand for paid labor” [10] has expanded work opportunities for online or offline service providers [7,11,12]. Using platforms such as Uber, Airbnb, Deliveroo, TaskRabbit or Foodora [13,14,15], people can easily find companies or individual clients in need of on-location work (e.g., cleaning, gardening, baby- or pet-sitting), remote work (e.g., data entry, application or website development, web design, influencer marketing) or other services like property renting, transporting or delivery [11,12,14,15]. In relation to such platform work [10], service providers (workers) have been commonly treated as self-employed rather than employees [12,16]. The COVID-19 pandemic further accelerated this rise of online, platform, and freelance work, and the digital economy overall [17,18]. Another key reason for the growth of self-employment is due to the advantages for many of this types of work, especially own-account platform work [11,12]. These advantages include providing an opportunity to work for unemployed people [4,12], flexible working hours [4,5,11,12,19], and greater control and freedom for workers [5].

However, there are also disadvantages. Many national legal frameworks do not offer self-employed workers the same rights as employees (e.g., collective bargaining, social dialogue, trade unions [7,20,21,22]), nor do they protect them in the same way they protect the latter [5,7,13,22,23,24,25]. For example, self-employed workers often have less entitlement to unemployment or sickness benefits than employees [26,27,28]. Moreover, in some countries, taking maternity leave is difficult (and sometimes even impossible) for self-employed workers, which is not the case for employees [29]. As an illustration, in Austria, self-employed women can only take maternity leave if they hire a full-time worker to replace them, which is often difficult for solo self-employed women or those self-employed with micro or small businesses [29]. The pandemic extenuated such disparities in entitlement between the self-employed and employees in many other countries, because self-employed workers were often not able to obtain the same degree of financial support as employees during the lockdown period [21,27].

These examples of discrepancies in entitlement to social benefits between the self-employed and employees are a challenge for at least two of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development’s goals. Firstly, the lack of social protection is an impediment to achieving SDG 8 [30], since some missing statutory benefits for the self-employed workers could challenge its aim of “decent work for all” [31]. However, the International Labour Organization (ILO) explicitly mentions that “all workers have the right to decent work, not only those working in the formal economy, but also the self-employed, casual and informal economy workers” [32]. Secondly, disparities between self-employed and employees challenge the goal of SDG 10 to “reduce inequalities within and among countries”, particularly since one of this goal’s targets is to “adopt policies, especially fiscal, wage and social protection policies, and progressively achieve greater equality” (10.4) [31].

Based on this recognition, the aim of this paper is to evaluate the challenges for achieving the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, especially SDG 8 and SDG 10, presented by the unequal entitlement to social protection by self-employed workers. To accomplish this, two secondary objectives are pursued: (1) to evaluate the current level of social benefits of self-employed workers across 31 European countries, and (2) to compare these social benefits with those of employees. Until now, previous papers have highlighted that self-employed workers have less social protection than employees, and have suggested policy initiatives to bridge this gap [4,7,20,21,29,33,34,35,36]. However, previous scholarship has not discussed this in the context of SDGs. Rather, they discuss the social protection of self-employed workers in general, without specifying in detail how this varies cross-nationally. The few studies that do examine these cross-national variations are out-of-date, using data from 2015 and 2019, and are limited in scope, focusing on only four particular social benefits: unemployment benefits [4,33], sickness benefits [4,29,33], old-age pensions [4,29,33], and maternity benefits [29,33]. Meanwhile, a report from the European Commission [37] investigated a larger array of social benefits, but only with data from 2017, and it does not discuss the challenges for achieving the SDGs. To fill these identified gaps, this paper aims to explore the social protection of self-employed workers for achieving the SDGs through an up-to-date in-depth review of the literature, and the legislation on the social protection of self-employed workers in 31 European countries.

To achieve this, the paper is structured as follows. Firstly, the concept of self-employment is explained. Secondly, we elaborate on the concept of social protection. After that, we analyze the social protection that 31 European countries offer self-employed workers, and compare this with the benefits offered to employees. The implications of the disparities are then discussed, not least for the achievement of SDG 8 and SDG 10. Finally, we draw conclusions and, based on them, make policy suggestions for both workers and policymakers. Limitations and further research suggestions are also included at the end of the paper.

2. Literature Review

2.1. What Is Self-Employment and Who Engages in Self-Employment?

In their systematic literature review of self-employment, Skrzek-Lubasinska and Szaban [38] highlight that there is no universally accepted definition of this concept. Even if official institutions such as the ILO, European Union or Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) do provide definitions for self-employment, individual countries often use their own definitions, because they adapt them to their national labor law [38]. However, broadly speaking, self-employment is a legal form of employment [20] within which the worker works in their own business, farm or professional practice, regardless of the type of contract they have or whether they employ other persons [38]. Therefore, a self-employed worker could be an entrepreneur who runs their own enterprise and hires other people at that enterprise, a family member who helps that entrepreneur with their business operations (without necessarily having a formal contract or a regular remuneration within the enterprise, since the entrepreneur could just be sharing the income with the contributing family members), but also a so-called ‘solo self-employed’ worker (i.e., a self-employed worker who does not hire others, but works on their own account alone) [38]. Concerning the solo self-employed workers, they can be either entrepreneurs/farmers/craftsmen working on their own business/farm/production hall without hiring any other employees [38,39], or freelancers providing professional knowledge or services for companies or individual clients [9,38]. The difference between these would be the fact that the former usually sell their goods, products or services, while the latter sell their professional knowledge and skills [40]. Another difference is that the former are more independent, while the latter (though still qualified as self-employed) have less control over the deadlines and sometimes even the means of production once they accept to work on a project for a client/company [9,38,40].

While this section does not aim to be an exhaustive analysis of the concept of self-employment (for that, see Skrzek-Lubasinska and Szaban [38]), it is important to answer the question “who engages in self-employment?” Indeed, a recent phenomenon has been to recognize that many self-employed workers are classified as such, despite having most of the characteristics of a dependent employee [25]. These workers are referred to using multiple terms, such as “bogus”, “false”, “fake”, “dependent”, “misclassified’’ self-employment or “disguised employment” [25,38]. Some authors find slight differences between these, but others see them all under the same umbrella: dependent self-employment in general [25]. This represents workers who identify/register themselves as self-employed and work for companies/clients under a contract that is different from the traditional employment contract, but actually meet most of the criteria for being classified as dependent employees: they have one major or a small number of clients from which they get their income or access to the market, they receive direct indications on how to do get the work done, and they do not have the authority to hire employees [25,41]. The main reason the phenomenon of dependent self-employment happens is related to the benefits for the employer. It is cheaper and more convenient for employers to have contracts with self-employed individuals than to hire employees [42]. In the latter case, they need to pay the workers during their holidays or sick days, to offer compensation in case of dismissal, and to respect a minimum wage for the salary, which is not the case if they choose the former option [25]. Thus, some employers explicitly ask (or even force) their employees to be registered as self-employed, even if they are, in fact, dependent employees [25]. However, dependent self-employment can also appear unintentionally. For example, the platform workers mentioned in the introduction sometimes might falsely and unintentionally classify themselves as self-employed even if they are, in fact, employees of a specific platform [42]. Whether it is intentional or unintentional, the workers are disadvantaged in dependent self-employment situations. Synthesizing the literature, Horodnic and Williams [25] explain that in general, within dependent self-employment, the workers have to rely on a major (or very few) client(s). Therefore, they become more prone to poorer working conditions which they have no choice but to accept (or else they lose their main source of income). Examples of these poorer working conditions are poorer physical working environment, tighter deadlines, less control over the workflow, work duration, or even the order or way to do the necessary tasks, and less involvement in important decisions [25]. Since all these aspects indicate precarious work, which could hinder workers’ well-being and level of work engagement, dependent self-employment is not truly sustainable in the long term, as Navajas-Romero et al. note [43]. The same was found in a report of Eurofound [44]. This explores the sustainability of work (which refers to achieving individual, social and economic goals within the labor market without jeopardizing workers’ capacity to work in the future) within self-employment through three sets of indicators: financial sustainability, work engagement, and health and well-being. The finding is that, indeed, dependent self-employed workers face more strained jobs, health problems, and physical and emotional exhaustion [44].

While it is stated that dependent self-employed workers face poorer working conditions than genuine self-employed workers, this is also the case if we compare self-employed workers in general (whether they are dependent self-employed or genuine self-employed) to employees. As mentioned in the Section 1, in many cases, self-employed workers do not have the same rights as employees (e.g., collective bargaining, social dialogue, trade unions [7,20,21]), nor the same social security entitlement [5,7,13,23,24,25]. This has significant implications for the achievement of the SDGs [45]. Therefore, the next subsection explores the concept of social protection through the lens of self-employment.

2.2. Social Protection. What Is It and What Does It Look like for Self-Employed Workers?

Social protection (often termed as social security, though this term is rather used in developed countries [46]) refers to public actions taken to address (i.e., prevent, reduce, and overcome) vulnerabilities, risks, and deprivation within a society [46,47]. To understand what vulnerabilities, risks and deprivation referred to in this context, it is important to note who is addressed through social protection, namely individuals, households, and communities [47]. To be more precise, the concept deals with the needs of two main categories within a society: (1) those who are vulnerable, poor or deprived of basic rights or needs, and (2) those who are non-poor or not necessarily vulnerable, but who need a guarantee that they are protected in case of different events in a human (and/or) worker life-cycling: pregnancy and childbirth, sickness, job loss, death, etc. [46]. Therefore, social protection deals with aspects such as poverty [46,48,49,50,51,52,53], economic growth [46,50], inequalities (and promotion of equality for all) [46,48,49,50,54], inclusion and non-discrimination [50], the social status of those who are marginalized [47,53], social justice [54,55], and many other vulnerabilities that members of a society can have (whether these vulnerabilities are temporary, like sickness or pregnancy, or permanent) [49,50,54], in order to improve their overall well-being [46,56]. Most definitions of the term do not limit social protection only to workers [46,47,48,50]. However, Barrientos [49], for example, explicitly mentions that the concept refers to programs, norms, and institutions a government uses to offer basic living standards to workers and their households [49]. Indeed, relying on the view that social protection has two main components, namely social assistance (non-contributory, usually residence-based) and social insurance (contributory, work-based) [46,56], the former targets workers. While social assistance (which is tax financed) [49] targets people in poverty, with disabilities, single parents in need of financial help, students in need of help after graduation, etc. [46,49,53,56] (usually regardless their employment status [37]), social insurance targets people who work and contribute with an amount of money from their earnings to resources they can eventually use when in need (health insurance, maternity benefits, pensions, unemployment benefits in case of dismissal, etc.) [46,49,53]. Even if this paper does not position itself as seeing social protection limited to workers, we will, however, focus on the social benefits of the self-employed workers, because this is the scope of this article.

To begin with, the standard employment relationship, which refers to permanent, full-time dependent employees, has been a key factor in guaranteeing labor rights and social protection [25,26,57]. This is because, in general, it is the employer that must meet some social obligations when they hire workers (i.e., they usually directly pay the social contributions of an employee by taking out an amount of their salary for that) [58,59]. Nevertheless, there are also other types of employment on the labor market, which can be referred to as non-standard employment relationships: part-time employment, temporary employment (under a fixed-term contract), multi-party employment (when an employee has an employment contract within a company which pays them, but they actually perform work or tasks for a different company), and others [37,60]. While in many countries efforts are made to provide the non-standard employees with the same social benefits as standard employees, a category that has been neglected is self-employed workers [25,37,57]. This can happen because, according to some definitions of the concept of non-standard employment, self-employed workers are not even included under this umbrella [37]. Another reason can be that, in multiple states, to be eligible for social insurance benefits, the criteria that workers must meet are more attuned to standard employees than self-employed workers (and non-standard workers in general), because they were designed for salaried employees from the outset [37]. For example, if the eligibility criteria for receiving a specific benefit requires a minimum number of contributing months or a minimum level of contribution, the self-employed can face difficulties if they have interrupted contribution periods [37]. Moreover, even when they manage to meet these criteria for social benefits, self-employed workers must often wait longer periods of time to receive them, or get the benefits only partially or for shorter periods of time compared with employees [37]. Indeed, in many countries, some specific categories of self-employed workers are completely excluded from access [37]. These disparities between the social benefits of employees and self-employed workers could be problematic, unfair, and even inefficient in many regards [37]. Before discussing this, we will investigate whether there are major differences between the benefits received by these two categories nowadays. In the next subsection, we present the social benefits of self-employed workers from 31 European countries and compare these benefits to those of employees.

2.3. A Legislative Framework Review Regarding the Social Benefits of Self-Employed Workers in 31 European Countries

To explore the social benefits received by self-employed workers across European countries, we opted for a comparative social policy analysis, as this was the approach suggested by the literature [61]. Although there is no universally accepted definition of comparative social policy analysis [62], generally, this refers to how social policies are delivered in different countries, and/or what outcome their implementation might produce [62]. Data was retrieved from the Mutual Information System on Social Protection (MISSOC) [63], which is a common source of information in studies treating the topic of social protection in Europe [64,65,66]. MISSOC is coordinated by the European Commission [67], and provides information (twice per year) on social protection systems of all the 27 European Union members, plus Norway, Iceland, Liechtenstein, and Switzerland (in the past, it also did so for the United Kingdom, until 2019) [68]. Data is gathered through collaboration with official representatives of ministries and institutions responsible for social protection from every participating country. These representatives periodically update the information on MISSOC [67].

Table 1, Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4 below document the social protection legislation of every country available on MISSOC (since all these countries are members of the United Nations). Data was last updated on 1st January 2023, and is presented, for a more comprehensible display, by region (Eastern Europe, Southern Europe, Northen Europe, and Western Europe, respectively), relying on United Nations’s Standard Country or Area Codes for Statistical Use [69].

For every presented country, the tables use two rows. The upper row displays whether the self-employed workers are covered by insurance schemes for certain social benefits. If they are not, a “No” appears in the table. If they are, we mention if the coverage is based on a residence-based scheme or a work-based scheme. This distinction is necessary because, while we look at differences between employees and self-employed workers in terms of their social benefits, a residence-based scheme guaranteeing a certain social benefit therefore implies no difference between the workers (because they receive the respective benefit only by being a resident in that state, regardless of their employment status). When covered by a work-based scheme, we mention if the system is compulsory (i.e., the self-employed workers are obliged to pay contributions from their income for being insured against the risk) or voluntary (i.e., self-employed workers are covered against the risk if they voluntarily choose to be and pay contributions). The lower row mentions if there are differences between employees and the self-employed workers regarding the conditions to access the benefits. If the conditions to be entitled to the benefits are the same for both types of workers, we use the letter “S”. If there are some differences, brief explanations are given. As such, the following abbreviations are used in the tables:

- No: meaning that the self-employed workers are not covered against the risk at all;

- NS: meaning that in that country, there is no specific scheme against the respective risk, but self-employed workers are or can be covered through other schemes (e.g., there is no specific scheme for long-term care, because that is already included under the healthcare scheme);

- R: meaning that people are covered against the risk based on a residence scheme, not on a work-based scheme. In this case, it does not matter if they are regular employees or self-employed workers, because they are covered anyway;

- C: meaning that self-employed workers are covered against that risk based on a compulsory work-based scheme;

- V: meaning that self-employed workers are covered against that risk based on a voluntary (opt-in or opt-out) scheme;

- S: meaning that conditions to be entitled to the social benefits are the same for both employees and self-employed workers;

- NA: not applicable (used in the lower row when comparing conditions to access benefits; i.e., if the self-employed workers are not covered against a specific risk at all, a comparison between their and employees’ conditions to access the benefits is not applicable);

- SE: meaning self-employed workers (used in the lower row to compare conditions for access to social benefits between self-employed workers and employees);

- E: meaning employees (used in the lower row to compare conditions for access to social benefits between self-employed workers and employees);

- **: meaning that exceptions exist.

Table 1.

Social benefit entitlements of self-employed workers in Eastern European countries.

Table 1.

Social benefit entitlements of self-employed workers in Eastern European countries.

| Country | Social Protection | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthcare | Sickness Cash Benefits | Maternity/Paternity | Invalidity | Old Age | Survivors | Accidents at Work | Family Benefits | Unemployment | Guaranteed Minimum Resources | Long Term Care | |

| Bulgaria | C | V | V | C | C | C | No | R | No | R | R |

| S | S | S | S | S | S | NA | S | NA | S | S | |

| Czech Republic | C | V | V | C | C | C | No | R | C | R | NS |

| S | S ** | S ** | S | S | S | NA | S | S | S | S | |

| Hungary | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C ** | C | No ** | NS |

| S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | |

| Poland | C | V ** (C for farmers) | V ** (C for farmers) | C | C | C | C | R | C ** | R | NS |

| S | At least 30 days to be insured continuously prior the sickness for E, 90 days for SE | S | S ** | S ** | S | S ** | S | S ** | S | S | |

| Romania | C | C | C | C | C, but V also possible | C, but V also possible | No | R | V | R | NS |

| S | S | S | S | S | S | NA | S | S | S | S | |

| Slovakia | C | C | C | C | C | C | No | R | V | R | NS |

| S | S | S ** | S | S | S | NA | S | S | S | S | |

Source: Own processing using MISSOC’s databases [63]. Clarifications and more details regarding the schemes can be found at the cited source.

In Eastern European countries, in general, self-employed workers are covered against most of the risks through work-based, compulsory schemes. Residence-based schemes are less common, but they are offered by five out of the six countries (i.e., all except Hungary) when it comes to family benefits and guaranteed minimum resources. Talking about risks self-employed workers are not covered against, the most common are accidents at work (in four out of six countries, with only Hungary and Poland offering protection), unemployment (in Bulgaria) and guaranteed minimum resources (in Hungary, with some exceptions).

Regarding conditions to be entitled to social benefits, Bulgaria, Hungary, and Romania demand the same from both self-employed workers and employees for all social benefits. The other countries are either more demanding with self-employed workers (i.e., Poland) or are susceptible to more exceptions (i.e., Poland, Czech Republic, and Slovakia) concerning these conditions.

Table 2.

Social benefit entitlements of self-employed workers in Southern European countries.

Table 2.

Social benefit entitlements of self-employed workers in Southern European countries.

| Country | Social Protection | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthcare | Sickness Cash Benefits | Maternity/Paternity | Invalidity | Old Age | Survivors | Accidents at Work | Family Benefits | Unemployment | Guaranteed Minimum Resources | Long Term Care | |

| Croatia | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | R | R | R | R |

| S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | |

| Cyprus | C | C | C | C | C | C | No | R | No | V | NS/V |

| S | S | S | S | S | S | NA | S | NA | S | S | |

| Greece | C | C | C | C | C | C | NS | R & V | C ** (No for farmers) | R & V | NS |

| Two months of insurance during the previous year required for SE. 50 days for E | SE must be insured on the day the illness occurs. E are required 120 days of work | Better conditions for SE (no minimum number of days worked required for them. 200 required for E | S | S | S | S | S | Differences based on the insurer | S | S | |

| Italy | C | No ** | R in kind, C in cash | C | C | C | C** | R | No ** | R | NS |

| S | NA ** | S ** | S | S | S | S | S | NA ** | S | S | |

| Malta | C | C for self-occupied/No for SE | R for Maternity Benefit, C for Maternity Leave Benefit. Only for self-occupied | C for self-occupied/No for SE | C | C | C for self-occupied/No for SE | R | C for self-occupied/No for SE | R | NS |

| S | S | S | S | Different calculation methods for pension rate | S | S | S | S | S | S | |

| Portugal | R | C | R in kind, C in cash | C | C | C | C | R | C ** | R | NS |

| S | More contributions needed from the SE | S | S | Flexible age of retirement impossible for SE | S | S | S | Different conditions based on type of SE | S | S | |

| Slovenia | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | R | C | R | NS |

| S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | |

| Spain | R | C ** | R in kind, C in cash | C | C | C | C ** | R | C ** | R | NS |

| S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S ** | S | S | |

Source: Own processing using MISSOC’s databases [63]. Clarifications and more details regarding the schemes can be found at the cited source.

As in Eastern European countries, in Southern European countries, in general, self-employed workers are covered against most of the risks through work-based compulsory schemes. However, in these countries, there are more residential-based schemes, these being offered in terms of family benefits (in all the countries in this region), guaranteed minimum resources (in all the countries in this region except Cyprus, which has a voluntary scheme), healthcare (in Portugal and Spain), unemployment, long-term care (both in Croatia) and maternity and paternity benefits. Regarding the last one, in Italy, Portugal and Spain, benefits in kind/care are offered based on a residential scheme, but benefits in cash can be obtained only based on contributions (i.e., they are offered based on a contributory, compulsory scheme). At the same time, in countries from this region, we can notice more cases in which self-employed workers are not covered against certain risks at all. Most frequently, they are not covered against unemployment (in Greece for farmers, Italy with some exceptions, and Cyprus), sickness (Italy), and accidents at work (in Cyprus). To these, we add the case of Malta, which does not offer benefits for the self-employed when it comes to sickness, maternity, invalidity, and accidents at work. However, it must be noted that this country distinguishes between self-employed and self-occupied. The latter is considered a self-employed person who earns more than EUR 910 per year. The former is defined as a resident of Malta, aged below 65 and who is not self-occupied [63]. Therefore, in terms of sickness, maternity, invalidity, and accidents at work, Malta does not offer benefits for self-employed but does for the self-occupied.

Concerning the conditions to be entitled to social benefits, the southern region presents the only country (from all four tables) where, regarding certain benefits, conditions are more relaxed for self-employed workers than employees. It is the case of Greece, which requires, for example, less or no worked days to be entitled to sickness cash benefits or maternity/paternity benefits. Such aspects could constitute one of the reasons this country also presents the highest percentage of self-employed workers in Europe (over 30% from the total employment) [37,70] but, of course, this is supplemented by other factors like the multitude of agricultural and tourism based economic activities [70]. By contrast, Portugal is more demanding on self-employed workers (e.g., more contributions required from self-employed for sickness cash benefits) and Italy and Spain apply some exceptions to their conditions to be entitled to benefits. Still, these countries are known to have high portions of self-employed workers due to various factors [37,70]. One of these could be the fact that the social security systems in these countries are less lavish with unemployed people or marginalized groups. For example, in the case of unemployment, the social protection offered by these countries is often nonexistent or based on previous work and contributions. Therefore, people who have never worked before and are unemployed, and other marginalized, vulnerable groups have no other choice but to start their own business to make a living [70].

Table 3.

Social benefit entitlements of self-employed workers in Northern European countries.

Table 3.

Social benefit entitlements of self-employed workers in Northern European countries.

| Country | Social Protection | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthcare | Sickness Cash Benefits | Maternity/Paternity | Invalidity | Old Age | Survivors | Accidents at Work | Family Benefits | Unemployment | Guaranteed Minimum Resources | Long Term Care | |

| Denmark | R | C | C | R | R | V | NS/V | R | V | R | R |

| S | At least 6 months worked for SE and at least 240 h for E | Conditions for E more relaxed (e.g., lower minimum no. of days worked required) | S | S | S | S | S | S ** (SE must close their entire activity) | S | S | |

| Estonia | C | C | C | R | C | C | NS | R | No ** | R | NS |

| S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | NA ** | S | S | |

| Finland | C | C | C | C | C | C | V ** | R | C | R | NS |

| S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | Longer employment required for SE | S | S | |

| Iceland | R | R | C ** | R & C | R & C | R & C | C | R | C | NA | NS |

| S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | NA | S | |

| Ireland | C ** | No** | C | C | C | C | No | R ** | C | R | R |

| S | S | S | S | S | 5 years paid insurance required for SE | NA | S | Lower minimum no. of weeks worked required for E + they can get the benefit if they work for up to 3 days per week, while SE need to stop activity | S | S | |

| Latvia | R | C | C | C | C | C | No | R for Family State Benefit + Child Raise Allowance, C for Parental Benefit | No | R | NS |

| S | S | S | S | S | S | NA | S | NA | S | S | |

| Lithuania | C | C | C | C | C, V for second-pillar pension scheme | C | No | R for Child Benefits, C for Childcare Benefits | C ** (only some categories of SE covered) | R | NS |

| S | S | S | S | S | S | NA | S | S | S | S | |

| Norway | C | C + V (to get the same coverage as E) | C for parental Benefit due to birth or adoption, R for Lump sum Maternity | C | C | C | V | C | No ** | R | NS |

| S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | NA | S | S | |

| Sweden | R | C | R in kind, C in cash | C ** | R for guaranteed pension, C for income-related pension | Same as for old age | No | R | C ** | R | NS |

| S | S | S | S | S | S | NA | S | S | S | S | |

Source: Own processing using MISSOC’s databases [63]. Clarifications and more details regarding the schemes can be found at the cited source.

In the Northern European region, we notice a higher number of residence-based schemes including social benefits such as: guaranteed minimum resources (in all the countries in the table except Iceland), family benefits (in all the countries in the table except Norway and with some exceptions in Ireland, Latvia, and Lithuania), healthcare (in Denmark, Iceland, Latvia and Sweden), invalidity (in Denmark, Estonia, and Iceland), old-age benefits (in Denmark, Iceland and Sweden for guaranteed pension), long-term care (in Denmark, Ireland), sickness cash benefits (in Iceland), and survivor benefits (in Iceland and partially in Sweden). A reason for so many residential-based schemes could be the fact that northern countries are generally well-developed countries, with lavish and more protective social security systems when it comes to vulnerable citizens [37,70]. Even if they offer multiple residential-based schemes, these countries still offer less benefits to self-employed people for accidents at work (with only five out of nine countries offering protection) and unemployment (with only six out of nine countries offering protection). At the same time, in Denmark, Finland and Ireland, conditions to be entitled to certain benefits (based on working schemes, not residence-based schemes) are harsher for self-employed workers than for employees. For example, in Denmark, a lower minimum number of days worked is required from employees to receive sickness cash and maternity/paternity benefits compared to self-employed workers.

The various residence-based schemes and the more demanding conditions required to be entitled to social benefits for self-employed workers (compared to employees), along with less protection offered to self-employed workers against unemployment and accidents at work, could be reasons why Northern European countries are known to have the lowest share of self-employed workers [37,70]. Surely, there are also other reasons, such as the fact that these countries have more active labor policies, which prevent informal work (often common within self-employment) [70]. At the same time, self-employment is sometimes seen as a way out of unemployment for people, but in these developed countries, citizens are more likely to be helped and integrated into the labor markets as employees [37,70].

Table 4.

Social benefit entitlements of self-employed workers in Western European countries.

Table 4.

Social benefit entitlements of self-employed workers in Western European countries.

| Country | Social Protection | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthcare | Sickness Cash Benefits | Maternity/Paternity | Invalidity | Old Age | Survivors | Accidents at Work | Family Benefits | Unemployment | Guaranteed Minimum Resources | Long Term Care | |

| Austria | C ** | C ** | C ** | C ** | C ** | C ** | C ** | R | V ** | R | R |

| S | S ** | S ** | S ** | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | |

| Belgium | C | C | C | C | C | C | NS | C | No ** | NS | NS |

| Contributions required for the first quarter of activity for SE, but not for E | Conditions for E more relaxed (e.g., more time for declaring work incapacity) | Conditions for E more relaxed (e.g., lower min. no. of days worked required) | S | S | S | NA | S | NA | S | S | |

| France | C | C | C | C | C | C | V ** | R ** | V ** | R | NS |

| S | Conditions for E more relaxed (e.g., lower minimum no. of months worked) | S ** | S ** | S | S | In agriculture, the accident must be declared within 8 days | S | SE must have worked minimum 2 years, without interruption and within the same company | S | S | |

| Germany | C ** | C **/No for farmers | C ** | C ** | C ** | C ** | V ** | R | V | R | C |

| S | S | S | S** (for farmers, minimum insurance of 5 years) | S ** | S** (for farmers, minimum insurance of 5 years) | S ** | S | S | S | S | |

| Liechtenstein | C | V | V | C | C | C | V | C | No | R | NS |

| S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | NA | S | S | |

| Luxembourg | C ** | C ** | C **/No paternity benefits | C ** | C ** | C ** | C ** | R | C | R | C ** |

| S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | At least 2 years of national insurance for SE, but they can also use the periods worked as employees | S | S | |

| Netherlands (Kingdom of the) | C | V | C + V, No for paternity | V | R for first pillar, V for other pillars | C | NS | R | No | R | C |

| S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | NA | S | S | |

| Switzerland | C | V | C | C for 1st pillar, V for 2nd pillar | C for 1st pillar, V for 2nd pillar | C for 1st pillar, V for 2nd pillar | V | C | No | NS | NS |

| S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | NA | S | S | |

Source: Own processing using MISSOC’s databases [63]. Clarifications and more details regarding the schemes can be found at the cited source.

In Western European countries, the social protection situation is like in Eastern Europe. In most cases, self-employed people are covered against risks through work-based, compulsory schemes. There are, however, more voluntary schemes in this cluster, especially due to the case of Liechtenstein. Residence-based schemes are less common but can be found when analyzing the guaranteed minimum resources (in all the countries except Belgium and Switzerland, which do not have a specific scheme for this, but cover workers through other schemes), family benefits (in Austria, France, Germany with some exceptions, Luxembourg, and The Netherlands), and long-term care (in Austria). Conditions to be entitled to social protection benefits are usually more relaxed for regular workers compared to self-employed workers.

3. Discussion

Regarding the first objective of the study, to evaluate the social benefit entitlements of self-employed workers across 31 European countries, it can be noted that, in general, self-employed workers are covered against multiple risks either through residential-based or work-based (contributory) schemes. As discussed above, work-based (usually compulsory) are more common in Eastern, Southern and Western European countries, while Northern European countries offer more residential-based protection schemes to their citizens (regardless of their employment status). This, amongst others, could be the reason why northern countries have the lowest share of self-employed workers (as a percentage of the total number of workers), while Eastern and Southern Europe have the highest rates of self-employed workers [70]. Nevertheless, most frequently, self-employed workers are not covered against unemployment (in 10 out of 31 countries in total) and accidents at work (in 9 out of 31 countries in total). Indeed, these two were highlighted in previous papers as being amongst the most challenging aspects regarding social protection of self-employed workers [28,37].

Turning to our second objective, which regarded a comparison between the social benefit entitlements of self-employed workers and those of employees, it is worth noting that even if self-employed workers can benefit from social protection in multiple other aspects (except the unemployment and accidents at work), there are still many steps to take to obtain equality between these two groups. Whilst self-employed workers are or can voluntarily opt to be covered against some risks, they are often required to fulfill more conditions to access the benefits than employees. With the exception of Greece (where, for example, in terms of sickness and maternity benefits, conditions to be entitled to these benefits are friendlier to self-employed workers than employees), in many other countries (such as Belgium, France, Portugal, Ireland, Poland or Finland), self-employed workers are required to overcome more hurdles to be entitled to these benefits. The most frequent difference between the self-employed and employees regards the minimum number of days worked required to be entitled to receive some benefits, which is usually higher for the former than for the latter (see, for example Belgium, Ireland, France, Poland, or Finland). Other examples of differences not favorable to self-employed workers are that, in Belgium, in cases of sickness or work incapacity, employees have more time to declare this aspect in order to receive the benefits compared to self-employed workers, or the fact that in Ireland, employees can still get unemployment benefits if they work for up to 3 days per week as employees, while self-employed workers need to completely cease activity. Besides these inequalities, there are indeed countries where conditions to be entitled to all the social benefits are the same for self-employed and regular workers (such as Croatia or Slovenia). Still, as mentioned in the Section 2, even in such cases, it is often more difficult for the self-employed to achieve the conditions (e.g., if the eligibility criteria for receiving a specific benefit requires a minimum number of contributing months or a minimum level of contribution, self-employed could face difficulties if they had interrupted contribution periods) [37].

Finally, to achieve the main overall objective of this paper, namely exploring challenges for achieving the goals of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development of the disparities facing self-employed workers in gaining access to social protection, based on the data in Table 1, Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4, there are problematic aspects. Two main issues previously highlighted in the extant but out-of-date literature [26,27,28,37] are still present today: (1) the fact that self-employed workers lack social insurance regarding some aspects (mainly unemployment and accidents at work), and (2) the fact that when they are entitled to social benefits, they encounter more impediments than employees.

On the first issue, this is problematic for numerous reasons. Firstly, since social protection is a potential contributor to reducing the risk of poverty [21], the lack of it could bring self-employed workers higher risks regarding this phenomenon [37,71,72], because they can fall into bankruptcy easier in case of unemployment, and they also have to face higher costs when in need of certain benefits which they are not entitled to [37]. Therefore, this could be problematic for achieving SDG 1 (“End poverty in all its forms everywhere”). Secondly, the under-insurance could be linked with informal (undeclared or under-declared) work and tax avoidance, because not being covered against certain risks demotivates self-employed workers to declare their legal form of employment [37]. By not legally registering (or by under-registering) their activity, self-employed workers completely or partially lose social benefits [24,73], and governments lose taxes from undeclared transactions [24,74,75]. Moreover, the informal economy itself is considered an impediment for achieving SDGs and sustainability overall [24,76], mostly because it implies no regulations over the working conditions [64].

On the second issue, besides contradicting the general mission of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development to leave “no one behind” [31], these disparities could directly affect the achievement of SDG 10, aiming to “reduce inequalities within and among countries”, especially because one of this goal’s targets is to “adopt policies, especially fiscal, wage and social protection policies, and progressively achieve greater equality” (10.4) [31]. Moreover, SDG 8 is of particular concern here due to a contradiction it implies. To elaborate on this, even if directing young people to self-employment (and entrepreneurship) was seen as a possible short-term strategy to reduce youth not in employment [77], which represents SDG 8′s sixth target, through its disadvantages for workers, self-employment challenges other targets (e.g., 8.5. “Achieving full and productive employment and decent work for all […]” or 8.8. “Protect labor rights and promote safe and secure working environments for all workers […]”) [31]. Nevertheless, even if other researchers suggest that social protection could contribute to achieving some SDGs, such as SDG 2, SDG 3, SDG 4, SDG 5 or SDG 16 [78], the social protection of self-employed workers is a hindrance.

4. Conclusions

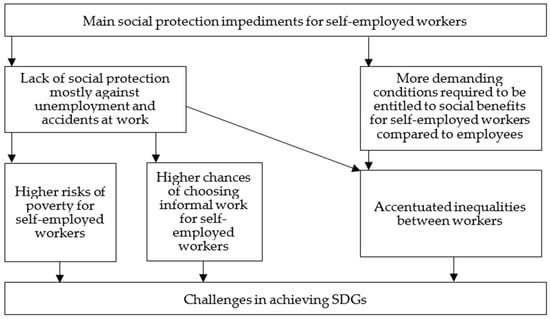

Through a review of the literature and the legislative framework of 31 European countries, this paper has drawn attention to the social protection of self-employed workers, which currently disadvantages these workers compared with employees. The most prominent issues are shown in the conceptual framework below (Figure 1). These are the lack of social protection against unemployment and accidents at work and the inequalities between employees and self-employed workers in terms of the necessary conditions to be entitled to access certain social benefits. They hinder the achievement of SDG 8, SDG 10, as well as other SDGs (for example, SDG 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework of the main findings of the study.

To tackle these disparities, governments should take actions to better protect self-employed workers and put them on an equal footing with employees. One suggestion is to strengthen the role of workers’ organizations that could mediate the dialogue between workers and social protection institutions [7]. Introducing more compulsory insurance schemes (and reducing exceptions for contributions payments and voluntary schemes as well) could also ensure better protection for self-employed workers and decrease their poverty risks [37]. Another approach would be to introduce more non-contributory, tax-financed and/or universal systems so that every citizen is guaranteed at least a basic level of social protection [13,37]. Here, of course, the solution rather relies on a combination of social insurance benefits and tax-financed (universal) benefits [13]. Lastly, another approach for achieving better social protection for self-employed workers could be simplifying and improving the transparency of the current regulatory systems, suggested by other authors [13,79,80], but also by the Council of the European Union [81]. Many legislative systems are too complex and, because of this, some self-employed workers may not be aware of their rights or obligations in terms of their social protection entitlements, not least because their form of employment is confronted by specific rules, different from those of employees [79].

This study also has limitations. One of them is that it is a theoretical and legislative review, which does not empirically explore the topic. Further studies could comparatively and empirically explore SDG indicators in different countries (for example, in countries with well-established social protection systems versus in countries with less benefits for self-employed workers). Such treatises would contribute to the discussion on the lower social protection or inequalities in terms of social benefits and how these issues hinder the achievement of SDG indicators.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.A.H. and M.M.-Z.; methodology, I.A.H. and C.C.W.; validation, I.A.H. and C.C.W.; formal analysis, M.M.-Z. and I.A.H.; investigation, M.M.-Z.; resources, M.M.-Z., I.A.H. and G.C.N.; data curation, M.M.-Z. and I.A.H.; writing—original draft preparation, M.M.-Z. and I.A.H.; writing—review and editing, I.A.H., C.C.W. and G.C.N.; visualization, M.M.-Z., I.A.H. and G.C.N.; supervision, I.A.H. and C.C.W.; project administration, I.A.H.; funding acquisition, I.A.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://www.missoc.org/missoc-database/self-employed/ (accessed on 10 January 2024).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- United Nations. THE 17 GOALS|Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 3 January 2024).

- United Nations. #Envision2030 Goal 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth. Available online: https://social.desa.un.org/issues/disability/envision-2030/envision2030-goal-8-decent-work-and-economic-growth (accessed on 3 January 2024).

- ILO. Report of the Director-General: Decent Work. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/public/english/standards/relm/ilc/ilc87/rep-i.htm (accessed on 3 January 2024).

- Fondeville, N.; Ozdemir, E.; Lelkes, O.; Ward, T. Recent Changes in Self-Employment and Entrepreneurship across the EU; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- IPSE. What Makes a Freelancer? Understanding the Rise of Self-Employment. 2019. Available online: www.ipse.co.uk/static/uploaded/57fe2c56-ecb8-40a8-a0a8191c7535d0eb.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2024).

- Khan, T.H.; MacEachen, E.; Premji, S.; Neiterman, E. Self-employment, illness, and the social security system: A qualitative study of the experiences of solo self-employed workers in Ontario, Canada. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ILO; OECD. Ensuring Better Social Protection for Self-Employed Workers. 2020; Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---ddg_p/documents/publication/wcms_742290.pdf (accessed on 28 December 2023).

- Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC). SDG 8: Promote Sustained, Inclusive and Sustainable Economic Growth, Full and Productive Employment and Decent Work for All in Latin America and the Caribbean. 2019; Available online: https://www.cepal.org/sites/default/files/static/files/sdg8_c1900794_press.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2024).

- Markovic, M.R.; Vujicic, S.; Nikitovic, Z.; Milojevic, A. Resilience for freelancers and self-employed. J. Entrep. Bus. Resil. 2021, 4, 30–36. [Google Scholar]

- Eurofound. Employment and Working Conditions of Selected Types of Platform Work; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mațcu, M.; Zaiț, A.; Ianole-Călin, R.; Horodnic, I.A. Undeclared activities on digital labour platforms: An exploratory study. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2023, 43, 740–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horodnic, I.A.; Williams, C.C.; Apetrei, A.; Mațcu, M.; Horodnic, A.V. Services purchase from the informal economy using digital platforms. Serv. Ind. J. 2023, 43, 854–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrendt, C.; Nguyen, Q.A.; Rani, U. Social protection systems and the future of work: Ensuring social security for digital platform workers. Int. Soc. Secur. Rev. 2019, 72, 17–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piasna, A.; Zwysen, W.; Drahokoupil, J. The Platform Economy in Europe. Results from the Second ETUI Internet and Platform Work Survey; Working Paper 2022.05; ETUI: Brussels, Belgium, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, C.C.; Horodnic, I.A. Regulating the sharing economy to prevent the growth of the informal sector in the hospitality industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 2261–2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez Garcıa, M.; Hospido, L. The challenge of measuring digital platform work. Econ. Bull. Banco Esp. 2022, 3, 1–18. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4022440 (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- ILO. Digital Platforms and the World of Work in G20 Countries: Status and Policy Action. 2021; Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---ddg_p/documents/publication/wcms_829963.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Khan, F.S.; Khalid, M.; Ali, A.H.; Bazighifan, O.; Nofal, T.A.; Nonlaopon, K. Does freelancing have a future? Mathematical analysis and modeling. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2022, 19, 9357–9370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Migai, C.O.; de Jong, J.; Owens, J.P. The sharing economy: Turning challenges into compliance opportunities for tax administrations. eJournal Tax Res. 2018, 16, 395–424. [Google Scholar]

- Anttila, J.; Jousilahti, J.; Kinnunen, N.; Koponen, J. Self-Employment in a Changing World of Work; UNI Europa Global Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2020; Available online: https://www.uni-europa.org/old-uploads/2021/04/EN-UE_Report-on-Self-Employment-2.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2024).

- ILO. World Social Protection Report 2020–22: Social Protection at the Crossroads—In Pursuit of a Better Future; International Labour Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Health, Decent Work and the Economy; World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- ILO. Decent Work in the Circular Economy: An Overview of the Existing Evidence Base. 2023; Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_dialogue/---sector/documents/publication/wcms_881337.pdf (accessed on 3 January 2024).

- Amarante, V. Informality and the Achievement of SDGs. Background Paper for United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Sustainable Development Outlook 2021. 2021. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/wp-content/uploads/sites/45/publication/SDO_BG2_Informality_and_achievement.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2024).

- Horodnic, I.A.; Williams, C.C. Evaluating the working conditions of the dependent self-employed. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2020, 26, 326–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forde, C.; Stuart, M.; Joyce, S.; Oliver, L.; Valizade, D.; Alberti, G.; Hardy, K.; Trappmann, V.; Umney, C.; Carson, C. The Social Protection of Workers in the Platform Economy; European Parliament: Brussels, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Schoukens, P.; Weber, E. Unemployment Insurance for the Self-Employed: A Way forward Post-Corona; IAB Discussion Paper No. 32/2020; Institut für Arbeitsmarkt und Berufsforschung: Nürnberg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Avlijaš, S. Social Situation Monitor. Comparing Social Protection Schemes for the Self Employed across EU 27. Focus on Sickness, Accidents at Work and Occupational Diseases, and Unemployment Benefits; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Avlijaš, S. The Dynamism of the New Economy: Non-Standard Employment and Access to Social Security in EU-28; LEQS Paper No. 141/2019; The London School of Economics and Political Science: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC). Making the 2030 Agenda a Reality through a New Social Contract. Workers and Trade Unions Major Group Sectoral Position Paper to the High-Level Political Forum. 2023; Available online: https://www.ituc-csi.org/IMG/pdf/wtumg_-_hlpf_submission_2023_en.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2024).

- United Nations. Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015. 2015; Available online: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/A_RES_70_1_E.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2024).

- ILO. Gender Equality and Decent Work: Selected ILO Conventions and Recommendations That Promote Gender Equality as of 2012; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012; ISBN 978 92 2 125535 2. [Google Scholar]

- Matsaganis, M.; Özdemir, E.; Ward, T.; Zavakou, A. Non-Standard Employment and Access to Social Security Benefits; Research Note 8/2015; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- ILO. Social Protection Spotlight. Extending Social Protection to Informal Workers in the COVID-19 Crisis: Country Responses and Policy Considerations. 2020; Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_protect/---soc_sec/documents/publication/wcms_754731.pdf (accessed on 21 January 2024).

- Schoukens, P.; Bruynseraede, C. Access to Social Protection for Self-Employed and Non-Standard Workers. An Analysis Based upon the EU Recommendation on Access to Social Protection, 1st ed.; Academische Coöperatieve Vennootschap cv: Leuven, Belgium, 2021; ISBN 978-94-6414-410-9. [Google Scholar]

- Spasova, S.; Bouget, D.; Ghailani, D.; Vanhercke, B. Self-employment and social protection: Understanding variations between welfare regimes. J. Poverty Soc. Justice 2019, 27, 157–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spasova, S.; Bouget, D.; Ghailani, D.; Vanhercke, B. Access to Social Protection for People Working on Non-Standard Contracts and as Self-Employed in Europe: A Study of National Policies 2017; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Skrzek-Lubasińska, M.; Szaban, J.M. Nomenclature and harmonised criteria for the self-employment categorisation. An approach pursuant to a systematic review of the literature. Eur. Manag. J. 2019, 37, 376–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milasi, S.; Mitra, A. Solo Self-Employment and Lack of Paid Employment: An Occupational Perspective across EU Countries; European Commission Background Paper No. 5; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kazi, A.G.; Yusoff, R.; Khan, A.; Kazi, S. The Freelancer: A Conceptual Review. Sains Humanika 2014, 2, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, D.; Leslie, K. Statistical Definition and Measurement of Dependent “Self-Employed” Workers. Rationale for the Proposal for a Statistical Category of Dependent Contractors; ICLS-Room Document 6; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, C.C.; Llobera Villa, M.; Horodnic, A. Tackling Undeclared Work in the Collaborative Economy and Bogus Self-Employment; European Platform Tackling Undeclared Work; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navajas-Romero, V.; Díaz-Carrión, R.; Ariza-Montes, A. Decent Work as Determinant of Work Engagement on Dependent Self-Employed. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurofound. Self-Employment in the EU: Job Quality and Developments in Social Protection; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Sharp, L.; Torp, S.; van Hoof, E.; de Boer, A.G.E.M. Cancer and its impact on work among the self-employed: A need to bridge the knowledge gap. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2017, 26, e12746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norton, A.; Conway, T.; Foster, M. Social Protection: Defining the Field of Action and Policy. Dev. Policy Rev. 2002, 20, 541–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avato, J.; Koettl, J.; Sabates-Wheeler, R. Definitions, Good Practices, and Global Estimates on the Status of Social Protection for International Migrants; World Bank Social Protection & Labour Discussion Paper No. 0909; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Aleksandrova, M.; Costella, C. Reaching the poorest and most vulnerable: Addressing loss and damage through social protection. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2021, 50, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrientos, A. Social protection and poverty. Int. J. Soc. Welf. 2011, 20, 240–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunori, P.; O’Reilly, M. Social Protection for Development: A Review of Definitions. European Report on Development. 2011. Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/29495/1/MPRA_paper_29495.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2024).

- Schmitt, C.; Lierse, H.; Obinger, H. Funding social protection: Mapping and explaining welfare state financing in a global perspective. Glob. Soc. Policy 2020, 20, 143–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robalino, D.A.; Rawlings, L.; Walker, I. Building Social Protection and Labor Systems Concepts and Operational Implications. Background Paper for the World Bank 2012–2022 Social Protection and Labor Strategy. 2012. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/671741468320349030/pdf/676080NWP012020Box367885B00PUBLIC0.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2024).

- Nyamu-Musembi, C.; Cornwall, A. What Is the “Rights-Based Approach” All About? Perspectives from International Development Agencies; IDS Working Paper 234; Institute of Development Studies: Brighton, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rana, I.A.; Khaled, S.; Jamshed, A.; Nawaz, A. Social protection in disaster risk reduction and climate change adaptation: A bibliometric and thematic review. J. Integr. Environ. Sci. 2022, 19, 65–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devereux, S.; McGregor, J.A. Transforming Social Protection: Human Wellbeing and Social Justice. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2014, 26, 296–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roelen, K.; Delap, E.; Jones, C.; Karki Chettri, H. Improving child wellbeing and care in Sub-Saharan Africa: The role of social protection. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 2017, 73, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C.C.; Horodnic, I.A. Introduction. In Dependent Self-Employment. Theory, Practice and Policy; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2019; pp. 1–13. ISBN 978 1 78811 882 8. [Google Scholar]

- Nyland, C.; Smyth, R.; Zhu, C.J. What Determines the Extent to which Employers will Comply with their Social Security Obligations? Evidence from Chinese Firm-level Data. Soc. Policy Adm. 2006, 40, 196–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Euzeby, A. Reduce or Rationalize Social Security Contributions to Increase Employment. Int. Lab. Rev. 1995, 134, 227. [Google Scholar]

- ILO. Non-Standard Employment around the World: Understanding Challenges, Shaping Prospects; International Labour Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; ISBN 978-92-2-130386-2. [Google Scholar]

- Bártová, A.; Emery, T. Measuring policy entitlements at the micro-level: Maternity and parental leave in Europe. Community Work Fam. 2018, 21, 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chasen, J. Defining comparative social policy. In A Handbook of Comparative Social Policy, 2nd ed.; Kennett, P., Ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2013; pp. 71–83. [Google Scholar]

- Mutual Information System on Social Protection (MISSOC). Self-Employed. Available online: https://www.missoc.org/missoc-database/self-employed/ (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Kolek, A. Public Tributes Imposed on Age-Related Benefits—A Comparative Analysis. Polityka Społeczna 2022, 18, 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariaans, M.; Linden, P.; Wendt, C. Worlds of long-term care: A typology of OECD countries. Health Policy 2021, 125, 609–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmahl, G. The Slovak Long-Term Care System. J. East. Eur. Res. Bus. Econ. 2022, 2022, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Social Protection Systems—MISSOC. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?catId=815&langId=en (accessed on 19 January 2024).

- What Is MISSOC. Available online: https://www.missoc.org/ (accessed on 19 January 2024).

- Standard Country or Area Codes for Statistical Use (M49). Available online: https://unstats.un.org/unsd/methodology/m49/ (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Hatfield, I. Self-Employment in Europe; Institute for Public Policy Research: London, UK, 2015; Available online: http://www.ippr.org/publications/self-employment-in-europe (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Fisher, M.; Lewin, P.A.; Wornell, E.J. Self-Employment among the Poor: Does It Pay off? J. Poverty 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conen, W.; Buschoff, K.S. Precariousness among solo self-employed workers: A German–Dutch comparison. J. Poverty Soc. Justice 2019, 27, 177–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deganis, I.; Tagashira, M.; Yang, W. Digitally Enabled New Forms of Work and Policy Implications for Labour Regulation Frameworks and Social Protection Systems; United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (DESA) Policy Brief No. 113; United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (DESA): New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C.C. Tackling Undeclared Self-Employment in South-East Europe: From Deterrents to Preventative Policy Measures. Econ. Altern. 2021, 2, 280–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horodnic, I.A.; Williams, C.C.; Țugulea, O.; Stoian Bobâlcă, I.C. Exploring the Demand-Side of the Informal Economy during the COVID-19 Restrictions: Lessons from Iași, Romania. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özgür, G.; Elgin, C.; Elveren, A.Y. Is informality a barrier to sustainable development? Sustain. Dev. 2021, 29, 45–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jianu, E.; Pîrvu, R.; Axinte, G.; Toma, O.; Cojocaru, A.V.; Murtaza, F. EU Labor Market Inequalities and Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cluver, L.D.; Orkin, F.M.; Meinck, F.; Boyes, M.E.; Yakubovich, A.R.; Sherr, L. Can Social Protection Improve Sustainable Development Goals for Adolescent Health? PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0164808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spasova, S.; Atanasova, A.; Sabato, S.; Moja, F. Making Access to Social Protection for Workers and the Self-Employed More Transparent through Information and Simplification: An Analysis of Policies in 35 Countries; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, G.C.; Leyaro, V.; Kisanga, E.; Byaruhanga, C. Policy Transparency in the Public Sector: The Case of Social Benefits in Tanzania; WIDER Working Paper No. 2018/50; The United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research (UNU-WIDER): Helsinki, Finland, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council Recommendation of 8 November 2019 on Access to Social Protection for Workers and the Self-Employed. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32019H1115 (accessed on 19 January 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).