1. Introduction

The evolving business environment makes competition more and more aggressive, and managing change is now one of the biggest challenges that requires particular attention. Contemporary organizations find themselves compelled to embrace organizational transformation as a strategic imperative for sustaining competitiveness in an environment characterized by continual evolution and instability. Scholars within the domain of management studies acknowledge that these profound transformations hold the potential to engender detrimental repercussions on employee attitudes and job performance [

1]. The expanding quantity of literature on the causes, consequences, and adopted techniques for organizational transformation is the outcome of important concerns and the complexity of workplace changes [

2,

3]. Leaders are the primary drivers of performance in every organization. Their vision, strategic thinking, enthusiasm, skill set, attitude, and behavior have a huge influence on how people perform under them to achieve company goals. One of the classic cases that caused Nokia, a big ICT company, to go bankrupt years ago was its failure to adjust its ambitions and operations to the smartphone revolution [

4]. As indicated previously in the examination, organizational transformation is a big topic presently, and many academics have been investigating this worldwide issue since the early days [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. Future research will focus on resistance, employee involvement, leadership style, corporate culture as a vehicle for successful organizational change, and organizational performance [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25].

Furthermore, the quantity of publications attests to the topic’s prominence, as several studies have been conducted in this sector during the last 20 years. Kurt Lewin was a pioneer researcher on organizational change who outsourced his job of changing workplace conditions by bringing new manners, ideas, and cultures from social psychology and human behaviors. The findings emphasize the importance of group dynamics in dealing with any organizational difficulties in a varied context [

12]. In his research, Hernaus [

26] highlights an overview of existing transformation models as well as a generic transformation model that may ensure change smoothly. While his contributions are noteworthy, his transformation model lacks empirical proof and has not been verified in real-world scenarios. It also requires the engagement of a third party (workers and management) to work. To analyze his impact on organizational performance, Khatoon et al. [

27] investigated organizational change via the lens of involvement, quality of communication toward change, leadership, top management attitude toward change, preparedness for change, and balanced scorecard viewpoints. The findings emphasize a favorable association between aspects of change and organizational success while emphasizing the significance of two-way communication at all stages. Mangundjaya et al., in their work [

28], discovered no beneficial association between change leadership and employee readiness to change in state-owned financial enterprises, but they can improve job satisfaction to easily develop employee readiness to change. Their findings contradict Balogun [

8], which underlines the need for change-ready leadership. Ref. [

24] conducted a 7-year study on the Kenyan postal service and discovered a strong and favorable influence of organizational reform on performance. Technology change has improved overall performance, but involving the entire organization during the transition period has specific advantages. When addressing organizational transformation, consider career growth, new positions and responsibilities, company culture, and employee dedication.

Observing the findings from Guberina et al. [

29] regarding entrepreneurial leadership (EL) style, it is suggested to examine EL by breaking down its components, given the intricate and multi-faceted nature of these constructs. While the research primarily addresses the fear of COVID-19 and its impact on psychological well-being, it underscores the significance of entrepreneurial leadership elements like empowerment as crucial elements in navigating uncertainties.

The majority of research reports on change management have concentrated on developed countries, particularly the world’s largest economies, in large organizations with change capacity [

9,

10,

13,

15,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39]. Few of them have been carried out in developing countries [

24,

36] particularly in West Africa.

As a result, the contribution is threefold. To begin, as pioneer research in Côte d’Ivoire, this study serves as a steppingstone by studying the function of employee involvement in organizational change effectiveness, which is a step in the right direction. Second, by addressing employee involvement through employee participation, empowerment, and teamwork, as well as organizational change with humble leadership as a mediator, the paper adds to the growing body of research on organizational change, as no previous studies on the topic have been conducted jointly [

40,

41,

42,

43]. Third, the author creates a change roadmap based on readings and existing models to complete the organization’s change methodologies. Consequently, the study contributes to the literature by achieving the following objectives:

To investigate the criticality of organizational change and its impact on business survival;

To identify barriers that impede the effectiveness of change and how to mitigate them;

To share recommendations with managerial implications to minimize related risks.

The remainder of the document is organized into the following sections:

Section 1 covers the introduction;

Section 2 exposes the literature review;

Section 3 discusses materials and methodology;

Section 4 presents the study’s findings and analysis; and

Section 5 addresses conclusions, limitations, and future research directions.

2. Literature Review and Development of Hypotheses

In the disciplines of employee involvement (EI) and leadership styles, the literature review indicates that the two have been separately linked to organizational change success. Employee participation, empowerment, teamwork and leadership have all been examined in relation to crisis management and organizational change individually by several studies [

34,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48], as well as leadership styles and the influence of business change by some studies [

28,

49]. The effects of humble leadership in non-bank organizations and independently have been studied only briefly, despite its benefits.

Ref. [

50] defines organizational change as the adjustment in behavior or ideas within an organization in response to internal or external factors. Organizational change aims to enhance the overall performance of a company and can be prompted by the proactive or reactive strategies of the organization’s management as well as crises. It is crucial to note that organizational change represents a profound transformation within the organization itself. Moreover, rapid transformations are becoming increasingly common in businesses due to highly competitive environments, driving organizations to seek greater competitiveness, increased sales and revenue, and overall expansion [

51]. The concept of organizational change encompasses a wide range of changes on a global scale, including changes in mission statements, cultural changes, operational methods, partnership agreements, merger decisions, and so on, which encompass a wide range of alterations. Through insightful research, ref. [

21] emphasizes that achieving growth and prosperity objectives necessitates an exceptional level of employee commitment and responsibility. Recent insights from [

52] perceive transformation as an ongoing, perpetual process, devoid of distinct starting or ending points.

In the research conducted by Zhao, Zhang, Qiu, Yu, and Hu [

53,

54], there is a highlighted necessity for the government to establish a clear policy to spearhead transformative initiatives, with strong recommendations advocating for it. Conversely, the situation in Ivory Coast presents a notable contrast. While the government has played a significant role in shaping the country’s development, organizational changes seem to be primarily motivated by market dynamics and the imperative to adapt to evolving economic circumstances rather than government directives. Recently introduced, the Numeric Strategic Plan 2021–2025 [

55,

56] focuses on digitizing public services and engaging workers through the establishment of a National Council Committee.

Employee involvement encompasses various dimensions and has been conceptualized in diverse ways. Firstly, as proposed by [

57,

58,

59], it can be viewed as a form of democratization, aimed at streamlining daily administrative processes, fostering consensus, and prioritizing the well-being of the majority. The extent of employee involvement plays a pivotal role in influencing an organization’s success. Secondly, according to insights from [

20], the commitment of the organization, the active engagement of middle-level managers, and group participation significantly impact the attainment of strategic information system planning objectives. A higher degree of commitment and involvement correlates with a greater likelihood of achieving these strategic goals. The third perspective focuses on enhancing employee input in decisions that impact both organizational performance and their welfare. Ref. [

60] summarizes this perspective into four essential elements: power, information, knowledge, and skills, as well as rewards, all geared towards empowering the workforce. Additionally, the perspective presented by [

61] underscores the importance of continual collaborative learning among employees. This involves the exchange and sharing of individual experiences, facilitating mutual learning. The active engagement of employees in implementing organizational changes not only enhances their value but also establishes conditions for sustainable organizational development in an environment marked by continuous change [

62]. To conclude, employee participation, empowerment, and teamwork emerge as three critical dimensions within these four perspectives of employee involvement, aligning with [

63]’s categorizations.

2.1. Employee Participation

The idea of employee participation (EP) has been a focal point for studies and exercise for many years. For many years, the concept of employee participation (EP) has been a focal point for research and exercise. The willingness and readiness of employees closer to the alternative procedure are critical to the overall success or failure of the change that each corporation seeks. Human actions are motivated by the desire for pleasure, which determines a person’s attitude. It is thus necessary to identify the employee needs that motivate them to participate in the change process [

64]. According to [

65], The disposition of some employees has an effect on and influence on the responses and attitudes of other employees toward organizational change. The positive attitude of employees toward change in an organization is undeniably the bedrock of the entire process’s success. Existing change management literature only provides frameworks and methodologies for managing change, and there is a need to incorporate change management. However, 70% of most change initiatives fail because most management fails to recognize the importance of employee resistance to organizational change and the development of negative attitudes toward organizational change, which affects their morale, productivity, and turnover intentions [

66,

67]. In their findings, ref. [

34] emphasizes the importance of involving employees in any process or change that may affect them; this can also help to reduce resistance to change. Ref. [

68] agrees with the cited authors that employee voice participation is a positive predictor of organizational innovation. Ref. [

69] demonstrates that designing performance metrics with employee participation appears to be beneficial from the perspective of managers. Aside from the fact that they are improving the quality of the metrics, it is also beneficial for employees to be involved in management strategies. We do not doubt the relationship between participation and change based on the evidence presented above.

Hypothesis 1 (H1). Employee participation is positively related to the effectiveness of organizational change.

2.2. Empowerment

Because of the various perspectives, empowerment (EMP) is both difficult to define and difficult to apply (from employees to managers). Refs. [

70,

71,

72] defined empowerment as the process of increasing feelings of self-efficacy among employees by identifying situations that foster powerlessness and eliminating them with the aid of each organizational practice and casual techniques of providing efficacy information. Empowerment was initially introduced as an individual-level construct and grounded in work on employee involvement [

12]. The importance of empowerment as a management strategy that can benefit entire organizations was asserted by [

73]. Her findings highlight empowerment as a tool for uniting employees in pursuit of organizational goals and performance. Empowerment is not only beneficial for change, but it is also a strategy for co-creating corporate social responsibilities. According to the [

74] argument, employees should be empowered to co-construct CSR decisions to increase their ownership and improve their relationship with the company. Empowerment benefits technological change and life satisfaction by increasing employee autonomy, commitment, and job satisfaction. As a result, empowerment may have a greater impact on organizational change [

75].

Hypothesis 2 (H2). Empowerment positively affects the effectiveness of organizational change.

2.3. Teamwork

Teamwork (TW), a central aspect of organizational behavior, has attracted considerable attention from both scholars and practitioners. In other words, teamwork fosters collaboration among employees, enhances individual skill sets, and facilitates constructive feedback without generating interpersonal conflicts [

76]. According to this perspective, employees who are engaged in team-based work are likely to be more productive than those who do their work independently. Teamwork is widely recognized as a critical component of effective management and as a tool for increasing the effectiveness of organizations as a whole. Furthermore, team environments can enhance employee productivity and performance by facilitating knowledge sharing and mutual learning. Consequently, there is a widely held belief that embracing collaborative efforts among team members can significantly amplify the potential for shared learning and heightened productivity. Prior research has demonstrated that teamwork correlates positively with job satisfaction [

77,

78] and organizational commitment [

79,

80]. Specifically, working within teams empowers employees, contributing to autonomy cultivation, which emerges as a fundamental driver of heightened organizational commitment and stress mitigation. This approach diminishes organizational hierarchies and amplifies employee involvement [

81]. In their work, ref. [

82] underscores the critical significance of team training, knowledge dissemination, and mutual support as instrumental components for performance enhancement. Consequently, it is evident that teamwork not only holds the potential to catalyze organizational change but also stands as a linchpin for augmenting overall organizational performance.

Hypothesis 3 (H3). Teamwork positively influences the effectiveness of organizational change.

2.4. Humble Leadership

Traditional leadership approaches characterized by rigid hierarchies and a significant distance between leaders and followers are becoming increasingly outdated and ineffective. In today’s organizations, which grapple with intricate, interdependent tasks, leadership needs to adopt a more personal approach to foster open and trust-based communication. This, in turn, enables collaborative problem-solving and promotes innovation. Leadership, as defined, is “the process by which one individual influences other group members toward the achievement of defined group or organizational goals” [

83]. These definitions underscore that leadership is not merely about holding a position but involves interaction, rallying followers, and contributing positively to a shared vision. The core function of leadership revolves around task completion [

84]. The successful implementation of changes hinges on various factors that interact at the organizational level and on the hierarchical distance from top to bottom management. These factors include organizational culture and the propensity to resist or embrace change, among other contextual elements shaping how different leadership styles are applied to drive change. Some research even suggests that leaders often struggle to effectively implement change, sometimes even serving as a significant obstacle or resistor to change [

85]. This underscores the critical need for apt and proficient leadership to achieve the desired outcomes from change initiatives. Additional research highlights that the ability to motivate others and communicate effectively are the two most crucial leadership behaviors for the successful execution of change [

86]. Organizations will continue to grapple with productivity and quality issues if their reward systems prioritize individual competition and climbing the corporate ladder over open and trust-based communication. Acknowledging this, ref. [

87] calls for an emerging breed of leadership that aligns with contemporary trends such as relationship building, complex group work, diverse workforces, remote work arrangements, and fostering a culture of psychological safety. Humble Leadership (HL), advocated by [

88], is seen as essential at all levels and within all working groups to foster the creativity, adaptability, and agility that organizations need to not only survive but thrive. Leadership style, resistance to change, employee commitment, and change implementation outcomes all intertwine to influence organizational effectiveness. Ref. [

89] found a positive correlation between humility and patient satisfaction, trust, and openness in medical encounters. Similarly, ref. [

90] emphasized the significance of expressed humility in achieving organizational performance. This underscores the critical role of leadership at all levels in the change process.

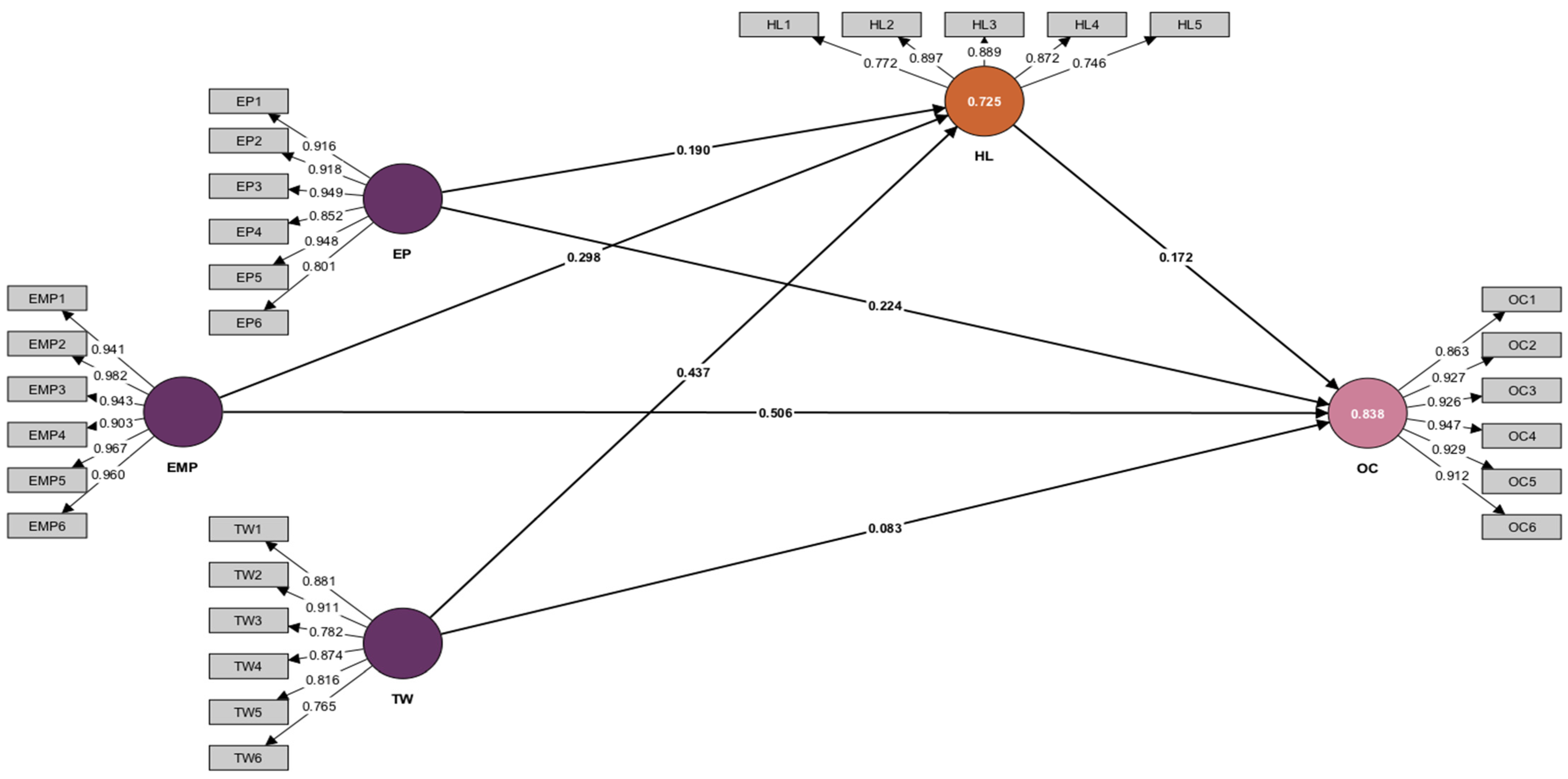

Figure 1 graphically shows the connections among those constructs.

Hypothesis 4 (H4a–c). Employee participation (a), empowerment (b), and teamwork (c) have a positive relationship with humble leadership.

Hypothesis 5 (H5). Humble leadership is positively related to the effectiveness of organizational change.

3. Research Methods

Employee data has been collected using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). In this study, respondents were chosen using purposeful sampling. It means that participants are chosen for inclusion based on a predetermined variable. The population for this study consists of employees from the telecommunications and refinery sectors who hold various positions in Abidjan, the capital city of Côte d’Ivoire. The questionnaire approach was chosen for several reasons. First, a large amount of data can be collected, standardized, and compared [

91,

92]. The Survey Monkey tool was used to collect data, and approximately 500 questionnaires were distributed. The study considered both primary and secondary data. In addition to primary data, secondary data is critical for any type of research, especially when primary data is collected through a sample. The use of multiple lines of evidence allows for triangulation [

93]. This triangulation protects against the development of the researcher’s bias [

94]. Secondary data has been gathered from a variety of sources, including books, journals, websites, and agency research reports.

3.1. Sampling and Analysis Technique

This study targets telecommunications and refinery workers. Ref. [

92] suggests that a larger sample size enhances result accuracy, and for this study, the sample size was calculated using the [

95] formula, considering the total population of 3246 employees. This formula was chosen for its simplicity, precision, and level of confidence. The study employed purposive sampling, a non-probability technique where researchers select participants based on their relevance to the study [

96].

The formula is as follows:

where

n = study sample; N = study’s population; 1 = constant; and

e = precision at 95% confidence level.

A total of 412 employees were chosen as the study population. The survey used non-probability sampling, including convenience and snowball sampling, with respondents selected based on their ability to complete the survey. These methods were chosen to mitigate sampling errors, with snowball sampling helping to better define the target population [

97].

Smart PLS 4 and Microsoft Excel v16.83 were also used for analysis purposes. PLS-SEM 4 was chosen for data analysis due to its superior predictive capabilities compared to factor-based SEM, enabling the estimation of relationships among various independent and dependent variables within a structural model, including multiple latent observed or unobserved variables. Additionally, PLS is considered advantageous for decision-making and management-centric issues, particularly in studies emphasizing prediction.

3.2. Measurements

We used the questionnaires from different studies shown in the below

Table 1 and adapted them for the study purpose.

5. Discussions

The results of the present investigation indicate that humble leadership plays a crucial role in facilitating organizational change by fostering an atmosphere of trust and openness, thereby enabling employees to confront future challenges intentionally [

40,

87]. This conducive environment created by humble leadership aids in reducing resistance to change among employees [

115]. The growing focus of scholars and managers on leadership styles underscores their significance in contemporary contexts. Through a thorough examination of the specific circumstances within the study sample, the importance of employee involvement has been highlighted, leading to recommendations for effectively navigating organizational uncertainty.

The correlation between employee involvement and the success of organizational change has been validated by research conducted by [

34] and Shin et al. [

68], who emphasized the enhancement of organizational innovation through allowing employees to contribute their insights on innovation strategies. Similarly, ref. [

116] examined employee participation through the lens of dynamic capabilities, revealing the pivotal role of engaging employees in identifying business prospects, fostering trust, and establishing informal control mechanisms.

Hypothesis 2 underscores the positive impact of empowerment on the effectiveness of organizational change. This aligns with the research by Liu, Han, and Zhang [

117], which demonstrates empowerment as a key driver of employee service innovation within the Chinese context. Similarly, a study in Sri Lanka [

118] highlights the importance of empowerment in addressing service failures within the hotel industry. While employee training yields benefits for both employers and employees, greater job autonomy can further enhance the wellbeing of service workers. Moreover, the influence of cultural beliefs on employee empowerment is acknowledged, as highlighted by Wen et al. [

119], who explored the role of empowerment in work engagement as a critical component for overall performance. Our findings resonate with these studies.

Regarding Hypothesis 3, which pertains to teamwork and its effectiveness in organizational change, ref. [

120] highlighted the significant impact of genuine collaborative efforts among physicians on enhancing patient safety outcomes. The findings from studies conducted by [

121] offer compelling evidence linking enhanced teamwork to the improvement of critical thinking abilities. Moreover, increased teamwork and higher levels of motivation were found to correlate with improved critical thinking, while a better understanding of teamwork was associated with enhanced future work skills. Our findings are consistent with those of [

122], who emphasized the importance of considering various factors such as the working environment, organizational structure, personnel, and tools as inputs to mitigate medical errors resulting from patient handoffs. Their results underscore the multidimensional nature of the process, involving the organization, teams, healthcare providers, and patients, all of which contribute to improving overall outcomes.

In the realm of organizational change capabilities, the significance of humble leadership has been explored in scholarly research. Ref. [

123] delves into this aspect, particularly in the context of IT uncertainties, demonstrating the advantages of humble leadership in facilitating organizational adaptability. The study underscores the symbiotic relationship between servant leadership and organizational performance in contemporary organizations. Furthermore, Yang, Zhou, and Luo [

41] investigate the critical role of service quality in healthcare, specifically among nurses, and examine how humble leadership contributes to fostering innovative behaviors among peers, thereby enhancing work engagement. Their findings corroborate the positive impact of humble leadership, aligning with similar conclusions drawn in our own research.

The positive correlation between employee participation (4a), empowerment (4b), and teamwork (4c) and the successful implementation of change within an organization, along with the impact of humble leadership on organizational change effectiveness, is well-documented. Research findings validate the interrelationship among these variables, as elucidated by [

63] in their investigation into achieving organizational performance through enhanced employee involvement and alignment with the ethos of humble leadership. Similarly, Jabber et al. [

124] underscore the pivotal role of servant leadership in fostering collaboration across different management levels within Bangladesh Police offices, reinforcing a parallel perspective.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

This study serves as an inaugural stride in augmenting our comprehension of the pivotal role played by modest leadership in navigating organizational change. Our documented observations carry profound implications for advancing scholarly inquiries into the constituent elements of employee involvement and their consequential effects on the efficacy of transformative initiatives. We elucidated the paramount importance of fostering employee engagement, cultivating collaborative teamwork, and empowering individuals to cultivate an environment conducive to change, notwithstanding its inherent intricacies and uncertainties. The empirical findings gleaned from this inquiry underscore the compelling notion that, by prioritizing employee engagement, embracing diverse managerial perspectives, and fostering synergistic collaborations, organizations can effectively surmount challenges inherent in the change process. Tailored training initiatives tailored for committed employees, clearly delineated change objectives, and steadfast advocacy for the overarching vision are integral strategies for mitigating employee resistance and steering towards desired outcomes. Additionally, the moderating role of humble leadership, alongside broader organizational management’s supportive posture towards transformation, emerges as critical considerations within this scholarly discourse.

To mitigate employee resistance during times of change, it is essential to facilitate transparent communication with all stakeholders. It is also essential to provide targeted training to directly involved employees, articulate clear change objectives, and foster a shared vision. Employee involvement (EI) can be an effective tool for enhancing communication and trust between organizations and their employees. However, for EI to yield maximum benefits, it must be implemented in conjunction with sound change strategies. Since employees are often the most directly impacted by these initiatives, achieving successful change primarily hinges on meeting their needs alongside the organization’s desired outcomes.

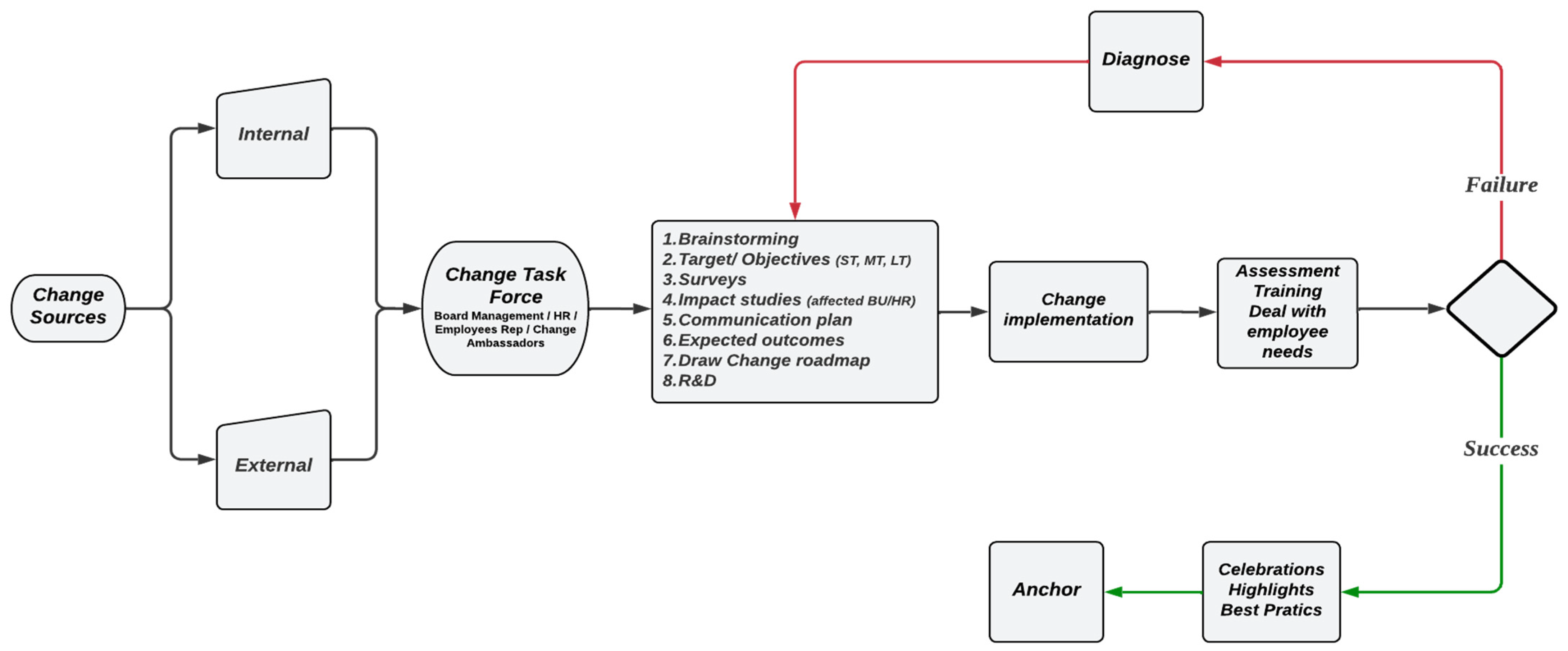

The following change roadmap is based on the initial change process provided by the pioneer of change studies [

30,

37,

125,

126,

127,

128,

129], considering the facts that change can succeed or fail [

5]. One of the well-known practices from previous change methods was to present change as “Change or Die”, implying that the company has no other options. This is possible, but resistance will increase, and employees may not understand the importance of change, as discussed in their recent studies [

13]. Instead of viewing “Change or Die” as a matter of urgency that truly affects businesses in this day and age, managers should frame it as a collaborative process in which employees can learn from one another and share backgrounds and experiences [

52]. In this way, the lower the resistance to change, the greater the involvement and the greater the benefits to the entire organization. Following the preceding steps, change will become a part of daily management rather than a one-time event. In simple terms, leaders must promote a participatory approach that includes a varied business unit as a watcher or actor so that everyone is on the same informational level [

114,

122,

130,

131,

132,

133,

134]. Taking these steps does not guarantee that change will be successful; failure is an option, but it is not fatal. The most important thing is to learn from mistakes and be able to train and strengthen the company’s internal change model. Finally, as recommended by Kurt Lewin [

12], celebrating change is necessary to maintain behaviors and work habits brought about by change while also promoting best practices. From our reading and diverse experiences, we proposed the following change roadmap (see

Figure 3) as a steppingstone for the African context, particularly Ivorian organizations.

5.2. Limitations of the Study

Delving into this subject matter necessitates a substantial population and an extended period of dedicated scholarly research. Consequently, our primary constraint revolves around the relatively modest scale of our research sample. Moreover, while the study was initially conducted in English, it underwent translation into French for survey participants due to their geographical location. This translation introduces the potential for communication bias, which could exert an influence on the quality of both inquiries and responses. It is also pertinent to note that our study exclusively focused on privately held enterprises. In a related academic context, certain scholars have traversed the landscape of subjects such as communication, corporate culture, and their role in steering organizational change [

30,

135]. Hence, it is recommended to conduct a follow-up investigation in varied contexts, possibly with a more consistent sample composition, to corroborate the hypothesized relationships.

5.3. Future Research

In forthcoming academic inquiries, it might be worthwhile to probe the intermediary influence of humble leadership in facilitating change implementation as well as pinpoint the most fitting corporate culture to address change prerequisites. Such investigations could significantly contribute to shaping effective communication avenues and systems to cater to the informational cravings of employees in the context of public organizations or non-mentioned industries to ensure the consistency of the variables.