Abstract

When examining the crucial role of civic competence in fostering sustainable societies, economies, and ecosystems, its significance for cultivating responsible and engaged citizens in our ever more interconnected global landscape must be recognized. Notably, education influences the development of civic competence throughout the learning experience at all levels of education. This research aims to explore the evolution of students’ self-assessment in terms of civic competence and its three subcompetences. The objective is to comprehend the present status of students’ self-assessments and explore their potential impact on the formation of a sustainable society. Data were collected for this study using an assessment tool elaborated in the ESF project “Development and Implementation of the Education Quality Monitoring System” for students’ generic competences. The tool, presented in a digital form using the QuestionPro platform, measures six generic competences, including civic competence. A total of 1166 bachelor’s degree students and 354 master’s degree students participated in this study, representing 22 Latvian higher education institutions. This study’s findings indicate that civic competence in the sample is considerably lower than the other generic competences measured, with a greater dispersion of results. The results also highlight specific areas within universities that require improvement during the learning process to cultivate individuals who are sustainable and socially responsible members of society.

1. Introduction

Sustainable development, recognized as a major global challenge, is an inclusive concept applicable to all countries worldwide. It plays a central role in the collective human effort to shape the world through globalization [1]. Shifting toward a sustainable future necessitates a reevaluation of what, where, and how we learn. This rethinking aims to cultivate the knowledge, skills, values, and attitudes essential for making informed decisions and undertaking individual and collective actions in response to local, national, and global urgencies [2]. In light of the uncertainty and division exacerbated by events like the COVID-19 pandemic and the conflict in Ukraine, there is a pressing need for a shift in skills to navigate these challenges and ensure survival. This means that people must adapt to living together sustainably on this planet. Such adaptation requires a fundamental shift in both individual and societal thinking and behavior. Consequently, education must evolve to foster the values and skills necessary for creating a peaceful and sustainable world. By doing so, we can secure the survival and prosperity of not only current but also future generations [2].

UNESCO has taken a leading role in education for sustainable development (ESD) since the United Nations Decade of Education (2005–2014). ESD is widely acknowledged as a fundamental component of Agenda 2030, particularly in relation to Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG 4), which focuses on transforming all aspects of the learning environment through a holistic institutional approach to ESD [2]. This approach aims to empower learners to embody what they learn and apply their knowledge to real-life situations.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) emphasizes the importance of providing students with opportunities to understand global developments, fostering critical and realistic perspectives on current affairs. This involves equipping students with tools for analyzing diverse cultural practices, engaging them in intercultural relations, and promoting the value of diversity [3]. Despite this, there is a scarcity of academic studies that validate the effective acquisition of civic knowledge, skills, and attitudes aligned with the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) using a specific validated framework or dedicated pedagogies [4].

In the realm of education, the discussion revolves around examining the evolution of generic civic competence and assessing the manifestation of its components across various educational levels. The positioning of civic education within educational frameworks is grounded in the notion that democracy, being a noninherent human condition, cannot be consistently assumed to be cultivated solely within the home and family environment. Therefore, it is advocated for and implemented in a secure educational setting and embedded in school curricula [5]. As such, civic education is considered vital to the development of civic competence for both this and future generations [6].

In the present context, civic education is acknowledged as a potential remedy for numerous social challenges, ranging from political uninterest and the mitigation of youth unemployment to the imperative of guiding young adults toward actively participating in addressing public issues [7]. It is crucial to highlight that the education system, as a whole, is recognized as a pivotal force in shaping civil society and fostering the development of civic competence. According to the European Commission Education and Training Monitor, education serves as a fundamental resource for internalizing core civic values. It also plays a key role in educating individuals about citizens’ rights and responsibilities while promoting social integration, with a specific emphasis on diminishing prejudiced attitudes toward marginalized groups [8] as well as encouraging learners to comprehend their democratic rights, fostering cooperation, and promoting critical thinking through the evaluation of media information. This, in turn, instills a sense of belonging to various communities, the state, and the broader European Union. The significance of this matter extends across all levels of education, including higher education.

Higher education, being a stage that concurrently addresses the preparation of highly skilled professionals for the labor market, the cultivation and rejuvenation of research human capital, and the establishment of a knowledge base fundamental for generating new knowledge, technologies, and innovations, holds particular importance. The overarching objective of sustainable education is to shape individuals who not only coexist harmoniously with nature and diverse cultures but also possess the capacity to fully realize themselves within society and the national economy. This involves ensuring the long-term and thoughtful utilization of resources. A person educated in this manner comprehends local issues and views them in a global context. They appreciate and respect other cultures, maintain healthy relationships across all societal levels, and actively contribute to economic development. In doing so, they play a role in fostering the longevity and sustainability of society [9].

In the current political and economic landscape, particularly in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, the readiness of individuals to fulfill their roles as citizens becomes a pivotal question. This is a moment where the dynamics of democracy, civic participation, political philosophy, and ethics not only come to the forefront but also undergo significant changes. The themes of uncertainty and dynamic change continue to hold relevance, especially in the realm of higher education and across professional sectors more broadly [9]. Given this context of uncertainty, the configuration of the university education process becomes a highly pertinent issue. The knowledge and understanding of citizenship, along with the social perceptions and attitudes cultivated in students, are crucial determinants of their behavior in situations of uncertainty and challenges. Consequently, the organization and content of civic education within study programs, as well as the qualifications and experience of educators, are simultaneously brought into focus. Addressing these aspects becomes essential in preparing students for active and informed citizenship in an ever-changing and uncertain world.

The quality assurance standards and guidelines within the European higher education space articulate the concept that higher education institutions bear the responsibility of fostering a sustainable culture. This involves the development of specific principles centered around student-focused learning, teaching, and assessment [10,11]. Generic competences encompass essential skills that can be acquired and are vital for effectively navigating change and leading a productive and meaningful life [12]. Notably, the cultivation of generic competences among students is important, especially in the context of economic sustainability. This emphasis serves to advance workforce preparation and contribute to long-term economic success [13].

To furnish the citizens of Latvia with modern, high-quality, and competitive higher education that fosters professional development, robust content development, and research and innovation capacity and enhances competitiveness in the labor market, a comprehensive review of the curriculum’s content and form is imperative. In line with this rationale, the Ministry of Education and Science (IZM) and the University of Latvia (UL) entered into a collaboration agreement for the ESF project “Assessment of the competences of students in higher education and the dynamics of their development during the study period”. The study’s primary objective was to examine students’ competences—specifically, innovation, research, digital, entrepreneurship, global, and civic—to identify the dynamics of their development in specific fields of study, namely, RIS 3 (smart specialization strategy for research and innovation) fields, creative industries, public management, and education. One of this project’s research dimensions focuses on the theoretical framework of the content of civic competence and the determination of its indicators in behavioral manifestations at various levels of higher education. This inquiry aims to contribute valuable insights to the enhancement of civic competence within the higher education landscape in Latvia.

It is important to mention that the criteria for civic competence can vary across countries, regions, and educational systems. For instance, in the United States, the National Standards for Civics and Government outlines expectations for civic competence [14]. The European Union has established key competences, including civic competence, as part of the European Framework of Key Competences for Lifelong Learning [15]. In England, the national curriculum includes citizenship education, delineating the knowledge, skills, and understanding students are expected to develop in relation to civic competence [16]. Similarly, the Australian curriculum incorporates content related to civics and citizenship education, specifying what students should know and be able to do in this area [17]. Civic education expectations are also outlined in provincial/territorial curriculum documents, such as in Ontario, where the “Civics and Citizenship” course delineates expectations for civic competence [18].

Drawing upon a review of the existing literature during the implementation of the ESF project “Assessment of the competences of students in higher education and the dynamics of their development during the study period”, a set of criteria for civic competence was formulated. These criteria encapsulate three key dimensions, emphasizing the multifaceted nature of civic competence: (1) knowledge and application of principles of democratic society; (2) involvement in the community; and (3) civic capacity [19]. In order to examine how civic competence may influence the establishment of a sustainable society and environment, it is first crucial to ascertain whether and in what manner each of the subcompetences is interconnected with sustainability.

1.1. Application of the Principles of a Democratic Society in the Development of a Sustainable Society

The knowledge and application of the principles of a democratic society entails an understanding of one’s own and one’s fellow citizens’ civil rights and responsibilities, recognizing their interrelationships and levels of proactive engagement [20]. It also involves grasping the concept of social justice as a foundational element for peaceful and prosperous coexistence at the community, national, and global levels. Additionally, it encompasses understanding and actively addressing various forms of prejudice, barriers, and social exclusion to mitigate associated risks [21]. Furthermore, civic competence equips individuals with knowledge and comprehension of various issues, including laws and regulations, democratic processes, media literacy, human rights, the economy, sustainable development, the global community, justice, equality, freedom, and autonomy [22,23]. This is crucial because the role of democracy involves promoting economic growth on the one hand and distributing the benefits of growth and reducing poverty on the other [24,25]. Knowledge of democratic society principles plays a significant role in the functioning and sustainability of democracies where the establishment of democratic structures and institutions is essential for social sustainability. In order to uphold and promote social sustainability, individuals need the freedom to engage in democratic behavior [26].

Democracies empower civil society to exert a significant influence on issues related to sustainable development, particularly addressing the challenges emphasized in the 2030 Agenda. In democratic settings, civil society plays a powerful role in advocating for inclusivity and ensuring that the benefits of sustainable development reach all segments of the population [25].

1.2. Application of the Involvement in the Community in the Development of a Sustainable Society

Community involvement is characterized by individuals’ understanding of the activities, management principles, and structure of local and national nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) (religious, business, cultural, social, sports, parental, professional). It involves individuals taking proactive initiatives at various levels of action in the implementation of social initiatives at both the local and national levels [20]. This subcompetence encompasses individuals’ understanding of EU and global NGOs, including their operating and management principles and structures. Individuals are expected to take proactive actions at different levels of EU and global NGOs. Community involvement is about individuals’ understanding of the ways in which the right to express an opinion is implemented at an individual level, the possibilities of resolving binding issues (problematic issues) in a legal manner, and their proactive engagement at various levels in addressing current issues [19].

The definition of community posits that it constitutes a framework comprising individuals, influences, and activities [27]. A community characterized by solidarity manifests a distinct social structure and shared identities. Additionally, the community is intertwined with its economic autonomy and resource utilization. This coherent framework demonstrates a considerable growth in industry, exemplified by steadfast and organized labor, underscoring the pivotal role of the community in conceptualizing and achieving communal objectives [28]. Sustainable development at the community level is shaped by the fundamental interactions between the public and individual levels [29]. Typically, these community responses converge and rely on addressing specific issues integral to the community’s concerns. However, groups of individuals with limited financial resources may find it challenging to enact meaningful changes within their own community [27,29].

Achieving sustainable development demands consistent and challenging efforts, and such endeavors may place a particular burden on communities that lack initiative, engagement, and resources. Community economic development involves an interactive process through which a community can initiate and address its inherent economic challenges, subsequently establishing enduring community foundations and fostering a blend of economic, social, and ecological objectives. Attaining sustainable community economic development entails a focus on sustaining employment and financial benefits by managing economic demand in a sustainable manner [30].

Individuals embracing sustainable development do not merely sustain the essence of life but markedly enhance it. To implement sustainable development methods, community members must acknowledge their capacity to shape their own lives, address their challenges, and mold their own future. This transforms the entire community into an informal organization, fostering assistance for everyone and expanded, strengthened participation and cooperation with individuals, institutions, organizations, and governments [31].

1.3. Impact of Civic Capacity on Sustainable Development

Civic capacity pertains to the ability to assess the potential for community capacity building, viewing oneself as a catalyst for change in the local community. It involves describing the level of participation and engagement in advancing community capacity and implementing sustainable development goals [20]. Furthermore, this subcompetence encompasses the understanding and capability to plan, execute, and assess activities on an international scale concerning the implementation of sustainability goals. It also includes the ability to compare different strategies for addressing global issues and evaluating all the evidence and arguments involved in the process [19].

Embodied within a diverse group of stakeholders collaborating to tackle a critical policy matter, civic capacity encompasses the establishment of common problem definitions and collective commitments involving a wide spectrum of both influential figures and grassroots participants [32]. Existing research on civic capacity has predominantly centered on assessing or tracing the evolution of these shared problem definitions and joint commitments [32,33,34,35]. However, a fundamental challenge in fostering shared understandings of problems arises when the definition of a problem and the relationships among stakeholders are contentious, leading to disputes over conceptions of knowledge [36].

Civic capacity can manifest at various levels, including associations, neighborhoods, cities, or nations [37]. The collective civic capacity is influenced by available resources, local institutions, and culture [35], shaping the potential for civic engagement and participation [37].

1.4. Sum-Up

The literature on civic competence underscores its significant role in shaping a sustainable society where individuals actively participate in local, national, and international political, economic, and cultural processes. The topic remains highly relevant in Latvia, especially considering the ongoing debate within the post-Soviet educational space. In this context, there exists a notable lack of understanding of critical thinking, democratic consciousness, and a partial or misunderstood comprehension of an active civic stance [38,39,40]. Civic competence encompasses the active participation of citizens in elections and the practice of democratic values. This is particularly crucial in light of ongoing hostilities in Ukraine, threats posed by Russia to the Baltic states, and the concerning low electoral turnout among Latvian citizens.

Therefore, to ensure the provision of contemporary, high-quality, and competitive higher education for the Latvian workforce, fostering professional development, research capacity, and competitiveness in the labor market leading to professional autonomy, a thorough review of the curriculum’s content and structure is imperative. Assessing the situation of Latvian higher education students entering or preparing to enter the labor market, their potential to establish nongovernmental and commercial businesses, and their role as citizens is also crucial.

This research explores the evolution of students’ self-assessments in terms of civic competence and the three subcompetences described above. The objective is to comprehend the present status of students’ self-assessments and explore their potential impact on the formation of a sustainable society.

2. Materials and Methods

Data were collected for this study using an assessment tool for students’ transversal competences developed in the ESF project “Development and implementation of the education quality monitoring system” (8.3.6.2/17/I/001) [41,42], which consists of an online survey that can be filled out in written form using the QuestionPro platform. The tool was constructed to measure six transversal competences: digital competence, innovative competence, entrepreneurial competence, research competence, civic competence, and global competence. This study used a stratified sample, but participants were selected on an accessibility basis. However, their selection was adjusted according to each subgroup’s size. This article deals only with bachelor’s and master’s students (from various fields) and only civic competence.

A 7-point Likert scale was used for competence evaluation, as a 7-point scale provides a wider variety of options, which, in turn, increases the probability of accurately assessing the objective reality of students [43]. This study examined civic competence based on three subcompetences: knowledge and application of democratic society principles (three statements), involvement in the community (three statements), and civic capacity (two statements).

First- and final-year students took part in this study. In total, 1166 bachelor’s students (756 from the first study year and 410 from the last study year) and 354 master’s students (181 from the first study year and 173 from the last study year) participated. These students represented 22 Latvian higher education institutions. In total, there are 24,687 students in the first or last year of their bachelor’s or master’s studies in Latvia [44], 1520 of whom participated in this study. Therefore, with a 95% confidence level, the margin of error is 2.45%. The average age of the participants was 26 years (Me = 22, SD = 9.58).

Cronbach’s alpha was used to determine the reliability of the Likert scale. Additionally, a Mann–Whitney U test was carried out to determine whether there were significant differences between the first and last study year civic subcompetence scores. Finally, a network analysis was carried out using the glasso (or graphical lasso) procedure to determine a network with edges defined by partial correlation coefficients [45]. Each edge represents the relationship between two variables. The graphical representation of the networks is based on the Fruchterman–Reingold algorithm, which places nodes with stronger and/or more connections closer together [46].

This study carried out the following steps to engage participants:

- An email was sent to all Latvian institutions of higher education requesting participation in this study and a brief description of the study and questionnaire.

- Within the framework of this study, a study course for lecturers of the institution of higher education was organized at the University of Latvia where lecturers helped to organize survey distribution among students of their represented faculties as a part of the course.

- The participants of this study addressed the lecturers of different institutions of higher education through personal contacts, asking them to help to organize student participation in the study.

The questionnaire was available for completion from 26 November 2022 to 30 June 2023, and the data were analyzed using SPSS Statistics version 21, Microsoft Excel, and JASP 0.14.1. This study followed all ethical research standards in accordance with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). The questionnaire was completed anonymously, and participation was entirely voluntary. Approval for conducting this research was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of Social Sciences and Humanities of the University of Latvia (08.02.2023. Nr.71-46/35).

3. Results

Cronbach’s alpha was calculated to assess the internal consistency of the Likert scale. Given that Cronbach’s alpha is 0.912, the Likert scale’s reliability is considered to be high [47].

Analyzing the bachelor’s students’ self-assessments of their civic competence, they can be considered low (Table 1): the mean and median values of all subcompetence self-assessments for first-year bachelor’s students are lower than 3 on the 7-point Likert scale. These students self-assessed their involvement in the community (mean = 2.57, median = 2.33) and civic capacity subcompetences (mean = 2.56, median = 2.00) as the least developed. This points to the fact that students need to develop their competences to initiate social events, participate in the activities of NGOs at a global or EU level, actively engage in legal protests, and organize cooperation on a local and global basis, identifying the diverse needs of partners.

Table 1.

Self-assessments of bachelor’s-level students’ civic competence.

The self-assessments of final-year bachelor’s students show a similar trend. These students self-assessed their knowledge and application of democratic society principles (mean = 3.20, median = 3.00) as the most developed of all subcompetences and their involvement in the community (mean = 2.67, median = 2.33) and civic capacity (mean = 2.75, median = 2.50) as the least developed.

In each of the evaluated subcompetences, final-year bachelor’s students’ self-assessments were higher compared to those of first-year students. Subsequently, a Mann–Whitney U test was carried out to determine whether these differences were statistically significant (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of bachelor’s students’ self-assessment rankings (Mann–Whitney U test).

The results indicate a statistically significant difference between first- and final-year bachelor’s students’ self-assessments of their knowledge and application of the democratic society principles subcompetence (z = −3.102, p < 0.05). However, there is no statistically significant difference in their self-assessments of the involvement in the community subcompetence (z = −0.466, p > 0.05) and the civic capacity subcompetence (z = −1.773, p > 0.05). It can therefore be concluded that students’ competence in systematically following topics in local, national, or EU political and legal frameworks, engaging in collaborative projects at different levels, and communicating with different types of institutions with a view to preventing problems and/or improving the quality of social or political processes increases during bachelor’s studies.

Turning to master’s students’ civic competence self-assessments, it can be concluded that the results are in line with bachelor’s students’ self-assessments (Table 3). The knowledge and application of the democratic society principles subcompetence was self-assessed as most developed by both first-year students (mean = 3.42, median = 3.33) and final-year students (mean = 3.65, median = 3.67). Master’s students self-assessed the involvement in the community and civic capacity subcompetences as less developed. However, the median and mean values of the self-assessments are relatively low, indicating that revising the higher education study process by integrating activities that enable students to improve their civic competence is necessary.

Table 3.

Self-assessments of master’s students’ civic competence.

The median and mean values of final-year master’s students’ self-assessments are higher compared to first-year master’s students for all subcompetences of civic competence. The exception is the involvement in the community subcompetence, which has the same median value for both first- and final-year students. Subsequently, a Mann–Whitney U test was carried out to determine whether the differences between the first- and final-year master’s students’ self-assessments were statistically significant (Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of master’s students’ self-assessment rankings (Mann–Whitney U test).

The results indicate that master’s students’ civic competence does not significantly improve during their studies. However, it should be kept in mind that master’s studies in Latvia last for two years, while bachelor’s programs last for three or four years and are therefore significantly longer. Additionally, first- and final-year students’ responses were gathered at the same time, meaning that there was only a one-year difference between first- and final-year master’s students but a two- or three-year difference between first- and final-year bachelor’s students.

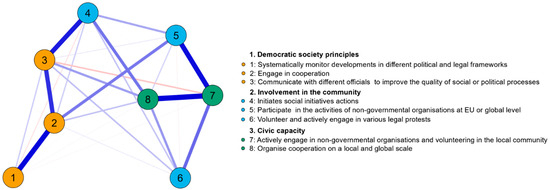

Network analysis was performed to examine the relationships between the subcompetences (Figure 1). The connections between nodes in the graph indicate whether there is a significant partial correlation. All eight nodes form mutually significant connections, and all 28 possible connections are formed with a sparsity value of 0.000.

Figure 1.

Network graph of all subcompetences of civic competence.

It can be concluded that the subcompetences of civic competence are interconnected. For instance, systematically monitoring developments in different frameworks is connected with cooperation, which is connected with communication and, further, with the initiation of social initiatives. Therefore, we can see a procedural scheme from knowledge or information to collaboration via communication to social initiatives. Similarly, there is a significant correlation between participation in NGOs and volunteering in the local community, which is further connected with organizing cooperation.

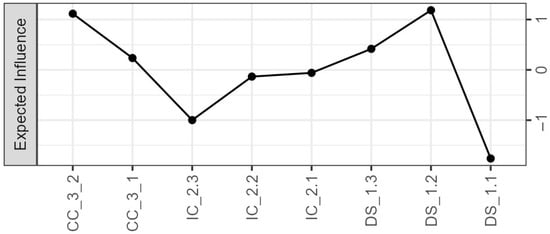

The expected influence graph indicates that the engaging in cooperation and cooperation organization subcompetences are the ones with the highest expected influence on other subcompetences (Figure 2). Therefore, it is advised to develop these subcompetences to facilitate the development of other subcompetences.

Figure 2.

Centrality measures of the expected influence of subcompetences.

4. Discussion

Sustainable development is acknowledged as a significant global challenge, and a crucial aspect of addressing this challenge is fostering a sustainable society with well-developed civic competences [1]. Moreover, civic competences are widely regarded as essential for democracy and social cohesion [48], a significance that becomes even more pronounced during times when a country’s democratic security is under threat. There has been a growing concern among Western democracies that active citizenship is in decline, with the lack of political engagement posing a significant risk to democracy [49]. This decline in participation is often attributed to younger generations, who are perceived as increasingly unwilling to fulfill the necessary duties for democracy to thrive, particularly in terms of voting [50]. However, while there is a close relationship between civic competences and democracy, it is important to note that this association does not imply causation in a single direction [48]. Some scholars argue that causality may run in the opposite direction, with democracy shaping civic competences rather than the other way around [51,52].

In this research, which was conducted to comprehend the present status of students’ civic competences, students self-assessed their civic competences as low. First-year bachelor’s students’ self-assessments’ mean values were all below 3 on a 7-point Likert scale. Students do improve their civic competences throughout their bachelor’s studies, but even the final-year master’s students’ self-assessments’ mean values do not exceed 4 and should thus be considered as low. The results also indicate that civic competences are interconnected: knowledge or information is connected with collaboration, which is connected to communication, which is connected to social initiative. All these subcompetences represent a chain of potential action, and if one of these subcompetences is underdeveloped, it could lead to social inactivity.

The low indicators of civic competence are to be expected, considering that the performance of Latvian students in the civic education test falls below the average achievements of all EU Member States. This trend has persisted since the IEA ICCS (International Civic and Citizenship Education Study) 2009 research cycle, indicating that both formal and informal methods of acquiring civic knowledge in Latvia are incomplete [48]. The IEA ICCS has been recognized as the gold standard for measuring civic understanding among school-age children since its inaugural survey in 1999 [53]. IEA ICCS results reveal that students with higher civic knowledge often point to scientists as authority figures, but their sense of belonging to Latvia is mostly promoted by their family, its history, and Latvian culture and nature. To express their opinion, students with higher civic knowledge most often post on social media networks, turn to their parents, or involve their peers [54]. Previous research indicated that civic engagement as students is associated with future civic engagement as adults [55].

A deeper exploration of students’ low involvement and limited sense of responsibility, particularly in taking the initiative, could benefit from a historical perspective. Considering that Latvia was annexed by the Soviet Union in 1940 and only regained independence in 1991, it is essential to recognize the historical context. During the Soviet-era occupation, Latvia’s education system adopted a “teacher-centered” pedagogy aimed at indoctrination. This approach discouraged multiple perspectives and deliberations on different viewpoints [53] while promoting the socialist agenda as sacrosanct [56]. Although it has been more than three decades since the restoration of independence, and the Latvian Ministry of Education has launched a nationwide reform of standards and pedagogy [57], knowledge of civic education has not shown significant improvements. Updating and enhancing civic education within the school setting is essential. This involvement is vital as it reflects students’ orientation toward citizenship, with implications for their potential engagement in future social and political activities [58]. At the core of democracy lies participation, requiring citizens to feel empowered to take action. The sustained engagement of citizens is, at least in part, influenced by their beliefs and perceptions regarding their role as citizens and their attitudes toward democracy [59].

An indispensable element in the construction of a democratic society is guaranteeing that all members possess the ability to influence social structures, processes, and outcomes. In contrast to corporatocracy or oligarchy, where social ideas, processes, and outcomes are tied to the control of financial resources, social democracy champions the active participation of people in the design and decision making of social constructs. It serves as a deterrent against social oppression fueled by power and money [60,61]. Research conducted on financial literacy and capability has established that financial decisions significantly impact the socio-economic well-being of individuals and families—fundamental building blocks of a democratic society [62].

In 2022, 22.5% of the population in Latvia was at risk of poverty—the same as in 2021, according to data from the population survey conducted by the Central Statistics Office in 2023. As a result of the impact of the pandemic and the war in Ukraine, Latvia’s economic situation has not improved lately. Although the proportion of the population at risk of poverty or social exclusion has decreased by 4.4 percentage points since 2014, Latvia still has one of the highest rates in this respect among all EU Member States. The latest available data show that Latvia has the fifth-highest proportion of the population at risk of poverty or social exclusion among all EU Member States [63]. A question thus arises as to whether one’s financial situation can be a factor influencing civic competence, as higher levels of socio-economic inequality are typically associated with a negative impact on civic engagement. In various contexts, both the incidence and the amount of charitable giving, volunteering, and nonprofit membership tend to be negatively affected by inequality. Research findings consistently demonstrate a negative relationship, particularly for charitable giving, nonprofit membership, and the quantity of volunteering. However, the evidence is less conclusive when examining the incidence of volunteering [64].

The low civic competence self-assessment scores suggest that changes need to be made, and numerous studies have underscored the importance of both formal and nonformal learning within the educational environment. In particular, nonformal learning has positive effects on students’ self-esteem [20] and their active involvement in civic participation [65]. The quality of interpersonal relationships within the educational environment [66,67] and specific study settings [68,69] are foundational elements for effective civic education. In educational contexts characterized as “democratic learning environments”, students encounter opportunities to experience relationships, attitudes, and behaviors aligned with the principles of a democratic society founded on openness, mutual respect, and appreciation for diversity. Actively participating in decision-making processes and management cultivates students’ confidence in democratic and participatory practices [20].

When addressing issues that impact students’ attitudes toward sustainability, it is crucial to integrate sustainability topics across all disciplines. This holistic approach aims to provide individuals with the necessary skills for systematic and critical thinking [70]. Achieving comprehensive sustainability entails a paradigm shift in thinking. It is imperative that environmental resources are not sacrificed in the pursuit of greater economic benefits [71]. Therefore, civically responsible behavior involves directing efforts toward economic development while concurrently upholding environmental sustainability.

There is a need for a comprehensive evaluation and improvement of civic education. A paradigm shift is required in civic participation at every level of the educational environment, as the current emphasis on environmental conservation and social, political, and sustainability activities in education is insufficient. Strengthening civic education and participation is crucial to mitigating long-term challenges and risks and contributing to the development of a critically thinking, resilient, and sustainable society in Latvia that is less susceptible to both external and internal manipulation.

5. Conclusions

In this study, Latvian students self-assessed their civic competences as low in accordance with a general trend observed since 2009. Despite education reforms, civic knowledge remains incomplete. Historical factors, like Soviet-era indoctrination, contribute to students’ limited initiative. Civic education needs updating to focus on student involvement for improved citizenship orientation. Financial literacy impacts civic engagement, especially in Latvia’s socio-economic circumstances. Formal and nonformal learning, democratic environments, and sustainability integration across disciplines are stressed in the research as ways to enhance civic competence. A paradigm shift in civic education is crucial for Latvia’s long-term resilience and sustainability.

6. Limitations

Self-assessment surveys are less accurate than objective ability tests or behavioral observations because responses can be affected by participants’ limited ability to recall specific examples of their behavior and by a general tendency to assess themselves and their competences higher than they actually are [19,41,42].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.M. and A.L.; methodology, G.L.; software, G.L.; validation, D.M. and A.L.; formal analysis, G.L. and A.L.; resources, D.M.; data curation, D.M. and J.G.; writing—original draft preparation, A.L. and G.L.; writing—review and editing, A.L.; visualization, G.L.; supervision, D.M. and J.G.; funding acquisition, D.M. and J.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the project “Vectors of societal cohesion: from cohesion around the nation-state (2012–2018) to a cohesive civic community for the security of the state, society and individuals (2024–2025)” (No. VPP-KM-SPASA-2023/1-0002). This research was supported by the project “Assessment of the Students’ Competences in Higher Education and their Development Dynamics during Study Period” as part of ESF project 8.3.6.2, “Development and Implementation of the Education Quality Monitoring System” 8.3.6.2/17/I/001 (23-12.6/22/2).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Latvia (08.02.2023. Nr. 71-46/35).

Informed Consent Statement

All the respondents were informed about the use of their research data and read the following statement: “By filling in this questionnaire, you agree that the information provided will be used anonymously in the research. You can stop filling in the form if you feel that you do not wish to answer any of the questions”.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Brunold, A. Civic Education for sustainable development and its consequences for German civic education didactics and curricula of higher education. Discourse Commun. Sust. Educ. 2015, 6, 30–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- UNESCO. Education for Sustainable Development: A Roadmap; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Preparing Our Youth for an Inclusive and Sustainable World: The OECD PISA Global Competence Framework; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Esteban, S. Telecollaboration for civic competence and SDG development in FL teacher education. Eur. J. Educ. 2020, 3, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Print, M. Reversing democratic decline through political education. In Who’s Afraid of Political Education? The Challenge to Teach Civic Competence and Democratic Participation; Tam, H., Ed.; Bristol University Press: Bristol, UK, 2023; pp. 180–194. [Google Scholar]

- Muleya, G. Curriculum policy and practice of civic education in Zambia: A reflective perspective. In The Palgrave Handbook of Citizenship and Education; Peterson, A., Stahl, G., Soong, H., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 185–194. [Google Scholar]

- Mouritsen, P.; Jaeger, A. Designing Civic Education for Diverse Societies: Models, Tradeoffs, and Outcomes; Migration Policy Institute Europe: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Education and Training. MONITOR 2018; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2018.

- Medne, D.; Jansone-Ratinika, N. Professional mastery of academics in higher education: The case of Latvia. In Innovations, Technologies and Research in Education; Daniela, L., Ed.; University of Latvia Press: Riga, Latvia, 2019; pp. 591–600. [Google Scholar]

- Cirlan, E.; Loukkola, T. Internal Quality Assurance in Times of COVID-19; European University Association: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Standards and Guidelines for Quality Assurance in the European Higher Education Area (ESG); EURASHE: Brussels, Belgium, 2015; Available online: https://www.enqa.eu/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/ESG_2015.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2024).

- Larraz, N.; Vázquez, S.; Liesa, M. Transversal skills development through cooperative learning. Training teachers for the future. Horizon 2017, 25, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rios, J.A.; Ling, G.; Pugh, R.; Becker, D.; Bacall, A. Identifying critical 21st-century skills for workplace success: A content analysis of job advertisements. Educ. Res. 2020, 20, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center for Civic Education. National Standards for Civics and Government; Center for Civic Education: Calabasas, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- European Union. Key Competences for Lifelong Learning—A European Reference Framework; Office for Official Publications of the European Communities: Luxembourg, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- National Curriculum in England: Citizenship Program of Study. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-curriculum-in-england-citizenship-programmes-of-study (accessed on 13 January 2024).

- Civics and Citizenship (Version 8.4). Available online: https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/f-10-curriculum/humanities-and-social-sciences/civics-and-citizenship/ (accessed on 13 January 2024).

- Civics and Citizenship. Available online: https://www.dcp.edu.gov.on.ca/en/curriculum/canadian-and-world-studies/courses/chv2o/overview (accessed on 13 January 2024).

- Rubene, Z.; Dimdiņš, G.; Miltuze, A.; Baranova, S.; Medne, D.; Jansone-Ratinika, N.; Āboltiņa, L.; Bernande, M.; Āboliņa, A.; Demitere, M.; et al. Evaluation of the Competences of Students in Higher Education and Their Development Dynamics during the Study Period. Round 1 Final Report; University of Latvia: Riga, Latvia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Council of the European Union. Council Recommendation on Key Competences for Lifelong Learning (Text with EEA Relevance) (2018/C 189/01); Council of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium.

- Medne, D.; Rubene, Z.; Bernande, M.; Illiško, D. Conceptualisation of University Students’ Civic Transversal Competence. In Technologies and Quality of Education, 2021; Daniela, L., Ed.; University of Latvia: Riga, Latvia, 2021; p. 1148. ISBN 978-9934-18-735-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boadu, K. Teachers’ perception on the importance of teaching citizenship education to primary school children in Cape Coast, Ghana. J. Arts Humanit. 2013, 2, 137–147. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, A.B.; Caetano, A.; Menezes, I. Citizenship education, educational policies and NGOs. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2016, 42, 646–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knutsen, C.H. The Business Case for Democracy. Working Paper 111; The Varieties of Democracy Institute, University of Gothenburg: Gothenburg, Sweden, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Banik, D. Democracy and sustainable development. Anthr. Sci. 2022, 1, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünal, F.; Kaygın, H. Citizenship education for adults for sustainable democratic societies. Sustainability 2020, 12, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mia, M.T.; Islam, M.; Sakin, J.; Al-Hamadi, J. The role of community participation and community-based planning in sustainable community development. Asian People J. 2022, 5, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, J. Theorizing community development. Community Dev. 2004, 34, 5–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, A.; Newman, L. Sustainable community development, networks and resilience. Environments 2006, 34, 34–45. [Google Scholar]

- Oláh, J.; Kitukutha, N.; Haddad, H.; Pakurár, M.; Máté, D.; Popp, J. Achieving sustainable e-commerce in environmental, social and economic dimensions by taking possible trade-offs. Sustainability 2019, 11, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattanno, K.; Swisher, M.E.; Moore, K.N. Sustainable Community Development Step 2: Conduct a Community Assessment. FCS7215-Eng; Institute of Food and Sciences, University of Florida: Gainesville, FL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, C.E.; Henig, J.R.; Jones, B.D.; Pierannunzi, C. Building Civic Capacity: The Politics of Reforming Urban Schools; University of Kansas Press: Lawrence, KS, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Marschall, M.; Shah, P. Keeping policy churn off the agenda: Urban education and civic capacity. Policy Stud. J. 2005, 33, 161–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, C.E. Civic capacity and urban education. Urban Aff. Rev. 2001, 36, 595–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, X.S. Democracy as Problem Solving: Civic Capacity in Communities across the Globe; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Page, S. A strategic framework for building civic capacity. Urban Aff. Rev. 2015, 52, 439–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letki, N. Civic capacity. In Encyclopedia of Governance; Bevir, M., Ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007; pp. 84–85. [Google Scholar]

- Rubene, Z. Topicality of critical thinking in the post-Soviet educational space: The case of Latvia. Eur. Educ. 2010, 41, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubene, Z.; Daniela, L.; Medne, D. Wrong hand, wrong children? The education of left-handed children in Soviet Latvia. Acta Paedagog. Vilnensia 2019, 42, 10–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubene, Z.; Svece, A. Development of critical thinking in education of Latvia: Situation analysis and optimisation strategy. In Innovations, Technologies and Research in Education; Daniela, L., Ed.; University of Latvia Press: Riga, Latvia, 2019; pp. 405–421. [Google Scholar]

- Miltuze, A.; Dimdiņš, G.; Oļesika, A.; Āboliņa, A.; Lāma, G.; Medne, D.; Rubene, Z.; Slišāne, A. Manual for the Use of the Competency Assessment Tool for Students Studying in Higher Education; Kaļķe, B., Ed.; University of Latvia: Riga, Latvia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Dimdins, G.; Miltuze, A.; Oļesika, A. Development and Initial Validation of an Assessment Tool for Student Transversal Competences. In Proceedings of the 80th International Scientific Conference of the University of Latvia, Riga, Latvia, 11 February 2022; pp. 449–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, A.; Kale, S.; Chandel, S.; Pal, D. Likert scale: Explored and explained. Br. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2015, 7, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Statistical System of Latvia. Available online: https://data.stat.gov.lv/pxweb/en/OSP_PUB/ (accessed on 30 June 2023).

- Zhao, T.; Liu, H.; Roeder, K.; Lafferty, J.; Wasserman, L. The huge package for high-dimensional undirected graph estimation in R. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2012, 13, 1059–1062. [Google Scholar]

- Dimdiņš, G.; Vanags, E. Network analysis of social measures, culture dimensions, and COVID-19 related behavioural choices. In Proceedings of the 81th International Scientific Conference of the University of Latvia, Riga, Latvia, 10 February 2023; pp. 8–18. [Google Scholar]

- Hinton, P.R.; Brownlow, C.; McMurray, I.; Cozens, B. SPSS Explained; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Print, M.; Lange, D. (Eds.) Civic Education and Competences for Engaging Citizens in Democracies; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R.D. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Wattenberg, M. Is Voting for the Young? Longman: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Barry, B. Sociologists, Economists and Democracy; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitter, P.C.; Karl, T.L. What democracy is … and is not. J. Democr. 1991, 2, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duplass, J.A.; Alksnis, R.; Čekse, I. Students’ perceptions of threats to their world’ future: An introduction to ICCS and global lesson plan. The Councilor 2023, 86, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Čekse, I.; Kiris, K.; Alksnis, R.; Geske, A.; Kampmane, K. The New Reference Point for Civic Education in Latvia: First International and Latvian Results from the International Civic Education Study IEA ICCS 2022; LU PPMF Izglītības Pētniecības Institūts: Riga, Latvia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Pancer, M.S. The Psychology of Citizenship and Civic Engagement; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015; p. 211. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández González, M.J. Cultural and Historical Research on Character and Virtue Education in Latvia in an International Perspective. Available online: https://dspace.lu.lv/dspace/handle/7/46411 (accessed on 13 January 2024).

- SKOLA 2030. Available online: https://www.skola2030.lv/lv (accessed on 13 January 2024).

- Keating, A.; Janmaat, J.G. Education Through Citizenship at School: Do School Activities Have a Lasting Impact on Youth Political Engagement? Parliam. Aff. 2015, 69, 409–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pospieszna, P.; Lown, P.; Dietrich, S. Building active youth in post-Soviet countries through civic education programmes: Evidence from Poland. East. Eur. Polit. 2023, 39, 321–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucey, T.A.; Bates, A.B. Conceptually and developmentally appropriate education for financially literate global citizens. Citizsh. Soc. Econ. Educ. 2012, 11, 160–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleeter, C.E. Teaching for democracy in an age of corporatocracy. Teach. Coll. Rec. 2008, 110, 139–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, M. Financial citizenship as a broader democratic context of financial literacy. Citizsh. Soc. Econ. Educ. 2020, 20, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabadzības Risks un Sociālā Atstumtība Latvijā 2023. gada EU-SILC Apsekojuma Rezultāti [Risk of Poverty and Social Exclusion in Latvia: Results of the 2023 EU-SILC Survey]. Available online: https://admin.stat.gov.lv/system/files/publication/2024-01/Nr_07_Nabadzibas_risks_un_sociala_atstumtiba_Latvija_2022_%2824_00%29_LV.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2024).

- Schröder, J.M.; Neumayr, M. How socio-economic inequality affects individuals’ civic engagement: A systematic literature review of empirical findings and theoretical explanations. Socioecon. Rev. 2023, 21, 665–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheerens, J. (Ed.) Informal Learning of Active Citizenship at School an International Comparative Study in Seven European Countries; Springer: Dordrecht, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bäckman, E.; Trafford, B. Democratic Governance of Schools. Available online: https://theewc.org/resources/democratic-governance-of-schools/ (accessed on 13 January 2024).

- Huddleston, T. From Student Voice to Shared Responsibility: Effective Practice in Democratic School Governance in European Schools; Citizenship Foundation: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cárdenas, M. Developing pedagogical and democratic citizenship competencies: ‘Learning by Participating’ program. In Civics and Citizenship: Theoretical Models and Experiences in Latin America; García-Cabrero, B., Sandoval, A., Treviño, E., Diazgranados Ferrans, S., Pérez Martinez, M.G., Eds.; Sense Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 207–239. [Google Scholar]

- Hahn, C.L. Pedagogy in citizenship education research: A comparative perspective. Citizsh. Teach. Learn. 2016, 11, 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doichinova, K. Learning for sustainability—Competences and expectations. Acta Sci. Nat. 2023, 10, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panula-Ontto, J.; Luukkanen, J.; Vehmas, J.; Kaivo-Oja, J. The Sustainability Window as a Tool for Combining Social and Environmental Dimensions of Sustainability. In Proceedings of the Sustainable Futures in a Changing Climate Conference, Helsinki, Finland, 11–12 June 2014. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).