Abstract

The concept of emotional salary refers to the non-monetary rewards granted to workers, focusing on improving interpersonal relationships, strengthening productivity, and enhancing the competitiveness of organizations. The topic of emotional salary is still recent and lacks empirical studies demonstrating its beneficial effects for both workers (e.g., job satisfaction) and organizations (e.g., performance). Therefore, to expand knowledge about the benefits of emotional salary, the present study used the self-determination theory to hypothesize that motivation and satisfaction would serve as affective mechanisms linking emotional salary to workers’ performance. Through a non-experimental correlational study, an online questionnaire was administered to 215 workers from various organizations. The results showed that emotional salary influenced performance (task, contextual, and adaptive) by increasing motivation and job satisfaction. The results also indicated evidence of a serial mediation path between emotional salary, motivation, satisfaction, and then performance. From a management perspective, considering emotional salary as an organizational resource capable of motivating and satisfying workers is a starting point for acknowledging the practical and theoretical importance of this concept, as well as a strategy to contribute to organizational sustainability.

1. Introduction

Currently, new and sustainable methods and practices of employee compensation based on their performance in the organization have emerged. One recently introduced approach is emotional salary. This is a practice aimed at addressing the personal and professional needs of employees that monetary compensation alone cannot fulfill [1].

According to Huete [2], emotional salary is the ability to make people feel well compensated for their efforts with something more than money. Plus, Martínez, Cagua, and Gómez [3] defined it as the non-monetary reasons that lead a worker to carry out their activities happily and committed to the organization. Gómez [4] emphasized that rewards should be directed toward satisfying the emotional and psychological needs of workers, as these influence their emotional well-being and productivity and the organization’s competitiveness. Emotional salary is framed in sustainable organizational practices because it aims to create conditions for employees to feel motivated and happier at work. Therefore, emotional salary should be part of the company’s strategic planning, as one of the organizational objectives that, in turn, motivates employees [5]. Therefore, there are various definitions of emotional salary, but they all lead to the same conclusion: emotional salary is a non-monetary reward to motivate the employee.

Nevertheless, research on emotional salary is still scarce. In other words, despite the assumption that emotional salary can motivate and satisfy employees, as well as positively influence certain organizational outcomes, to date, there are still few studies demonstrating its beneficial effect on performance (task, contextual, and adaptive) [6].

Therefore, this study used the self-determination theory [7] as a theoretical framework to examine how emotional salary can positively influence performance. SDT has shifted its focus toward various forms of motivation, ranging from autonomous to controlled motivation, to predict outcomes such as performance. The theory differentiates between autonomous and controlled motivations. Autonomous motivation entails acting with a complete sense of volition, endorsement, and choice, while being controlled involves feeling externally pressured or compelled to behave, whether due to the promise of a contingent reward, fear of punishment, ego involvement, or other external factors. SDT further proposes that there are fundamental psychological needs that must be universally fulfilled for individuals to undergo continuous growth, maintain integrity, and experience overall well-being and satisfaction. These essential needs include the need for competence, autonomy, and relatedness.

Numerous studies have demonstrated that individuals who are autonomously motivated, either by intrinsic motivation or well-internalized (and thus autonomous) forms of extrinsic motivation, exhibit higher levels of interest and satisfaction, leading to improved performance [7]. Hence, relying on the SDT, we argued that emotional salary will promote conditions for employees to experience autonomous motivation that will help them to fulfill their competence, autonomy, and relatedness needs. This, in turn, will make them more satisfied with their work and, as a result, lead to improved performance. As such, this study aimed to (1) analyze the relation between emotional salary and (a) motivation, (b) satisfaction, and (c) performance, and (2) test the mediating role of (a) motivation and (b) satisfaction in the relation between emotional salary and performance.

Considering the previously mentioned, it is of utmost relevance to investigate the mechanisms that connect emotional salary to performance. Only in this way will it be possible to advance knowledge about this phenomenon, outline the concept of emotional salary more consistently, understand its components, and ultimately draw theoretical and practical conclusions about it. Everyone is unique with distinct needs, so it is crucial to understand what each person needs before applying emotional salary. A worker with a family will not have the same needs and ambitions as a young and single worker, so it does not make sense for a company to provide both with a daycare voucher, for example. Therefore, understanding the practical implications that emotional salary can bring to companies and how they can address them becomes fundamental.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Emotional Salary

One of the methods that organizations have used to reward employees for their performance is economic compensation, i.e., monetary remuneration [8]. However, a recent challenge has emerged for modern organizations—talent retention. This may be because organizations seem to assume that the only form of compensation for employees is economic and not emotional [9]. It was in this context that the concept of emotional salary emerged.

The emotional salary is about rewarding employees with something more than monetary compensation, addressing their psychological and emotional needs, both personal and professional, as a way to add value and improve their quality of life [8]. According to Puyal [10], emotional salary should include satisfaction, both in terms of quality and quantity, considering that each employee has different needs and interests. Also, González and De Avice [11] defined emotional salary as all non-economic rewards that a worker receives to help meet their personal and family needs; it essentially has a non-monetary nature with a symbolic impact on people’s quality of life and productivity. For Salvador-Moreno and colleagues [5], emotional salary encompasses three factors that foster employee satisfaction and enable professional and family development: a positive work environment (e.g., having positive relationships with colleagues), opportunities for personal and professional development (e.g., training, workshops, coaching), and flexibility given to the worker (e.g., telework or flexible hours). Emotional salary should therefore be an organizational strategy based on the individual characteristics and flexibilities of each employee without implying monetary expenses [12], as emotional salary should correspond to creative and personalized actions that lead to the satisfaction of each worker [5].

In summary, emotional salary is more than tangible benefits; instead, it focuses on providing intangible benefits that address the needs of workers and contribute to improving their motivation and satisfaction with work and life in general.

2.2. The Relation between Emotional Salary and Performance

Performance is a factor of competitiveness for organizations and is one of the main outputs, generating value for individuals and organizations. For several authors, performance is a behavioral construct that allows the achievement of organizationally significant objectives through an action or a set of actions [13]. It has also been proposed as a multidimensional construct, including three dimensions: adaptive performance, task performance, and contextual performance [14].

Currently, adaptation is one of the main essential capabilities for the survival and success of an organization; thus, adaptive performance relates to work behaviors that enable individuals to adapt to change and uncertain situations, as well as their integration into contexts with different people and cultures. Adaptive performance is a determining factor for the growth, development, and success of organizations and employees [15]. For example, adapting to new software is part of adaptive performance.

Task performance, on the other hand, is specific to the type of work or formal function, influenced mainly by individuals’ capabilities and knowledge, and is associated with formal reward systems [16]. Thus, task performance encompasses a set of requirements described and established by the function [17]. For example, achieving task goals is an indicator of task performance.

In turn, contextual performance consists of behaviors that do not directly contribute to organizational performance but positively promote the social and psychological environment of organizations. It includes activities that cut across most jobs and are influenced by motivation and personality; further, unlike task performance, it is not rewarded by formal reward systems [16] but can be enhanced through practices of emotional salary. Helping a colleague is an example of contextual performance.

The relation between salary policy, benefits, and performance has shown that compensation and benefits policies impact employee turnover, performance, and attitudes. Companies need to maintain a balanced relationship between incentives and contributions, as each employee makes contributions to the organization in terms of work, dedication, effort, and time while receiving incentives in return, such as salary, benefits, recognition, awards, and promotions. Organizations, in turn, are willing to incur certain costs to obtain results and contributions from employees. Thus, each party invests to obtain returns from the other, comparing costs and benefits—as argued by the norm of reciprocity proposed by social exchange theory [18,19].

Emotional salary has been approached as a contribution to improving job performance, taking into account the non-monetary benefits and compensations offered to employees [20]. According to Cervantes [21], an employee’s value is measured through their performance and the value that this contribution adds to the organization, not by the overtime hours worked, for example. Buqueras and Cagigas [22] indicated that an employee’s performance decreases after a certain number of hours worked, which is entirely natural, leading to the establishment of a standard daily working schedule, such as 8 h. These authors commented that having a rewarding presence is not synonymous with good performance but rather working toward goals and results. This does not mean working less but rather doing it better, optimizing time through punctuality, planning, and organizing time and tasks, among other factors [22]. Therefore, organizations that focus on time management can gain a competitive advantage in the medium and long term, reflected in the optimization of working time; flexible schedules; the balance between the employee’s personal, professional, and family life; and consequently, increased levels of productivity and performance [22].

According to Marshall [23], establishing compensation or salary incentives based on performance is certainly a way to stimulate the growth of productivity, which is equally reflected in the performance of workers. Therefore, it is said that emotional salary has the primary purpose of developing a more productive and meaningful life for workers and, thus, promoting the balance between professional and personal life. This benefit is used by companies seeking to increase their standards of quality and productivity while simultaneously reducing absenteeism and turnover rates [6].

Thus, relying on the central asset of the social exchange theory, the reciprocity norm [19], we hypothesized the following:

Hypothesis 1.

Emotional salary has a positive relation with (a) adaptive, (b) task, and (c) contextual performance.

2.3. The Mediating Role of Motivation

Motivation and satisfaction play a crucial role in employees’ behavior and attitudes. The self-determination theory (SDT; [24,25]) is a theory of human motivation that has demonstrated effectiveness in predicting motivated behavior across various contexts and populations and for a variety of behaviors [24], including performance [7,26,27]. The principles of the self-determination theory consider that individuals’ motivations are different, determined, and guided by contexts of psychological needs, naturally manifesting in distinct ways. This complexity makes motivation a multidetermined phenomenon that can only be inferred by observing behavior, whether in real performance situations or through self-reporting [28,29]. The SDT is unique among motivation theories due to its focus on the quality of motivation, not just quantity [30]. This theory emphasizes the importance of the type of motivation driving people’s behavior, along with considerations of the degree to which individuals are motivated.

Central to the theory is the distinction between self-determined or autonomous forms of motivation and non-self-determined or controlled forms [7,24]. These motivational subtypes reflect the degree to which actions are fully endorsed by the individual. This suggests that there are two types of motivation guiding behavior: extrinsic motivation (i.e., to obtain a reward or consequence separate from the activity itself) and intrinsic motivation (i.e., doing something because of an inherent inclination or interest; [31]). Furthermore, extrinsic motivation can be divided into four types, ranging from less to more autonomous: external (i.e., for reward or praise), introjected (i.e., to avoid guilt or anxiety), identified (e.g., because the person sees value in the activity), and integrated (e.g., because the person has internalized the reasons for engaging in the behavior; [31]).

Another key premise of the theory is that the quality of individuals’ motivation when they act is determined by the extent to which they see their actions as consistent and in service of three basic psychological needs—autonomy, competence, and relatedness [7,24]. These needs are considered universal and are implicated in the process that gives rise to the type of motivation experienced in behavioral contexts (i.e., features) of each of the three psychological needs. The need for autonomy reflects actions freely chosen and self-endorsed, reflecting individuals’ need to have a sense of ownership and responsibility for their actions. The need for competence refers to the experience of being effective in one’s environment, mastering tasks mentally or physically, tackling challenging tasks, and perceiving that one has sufficient capability to perform actions. The need for relatedness reflects the need to feel accepted and respected and to create a mutual bond with other important individuals [7,24]. Some studies have reinforced the primacy of the needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness above other needs [32] and across different contexts [33]. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that the satisfaction of these needs mediates the associations between autonomous motivation and behavioral persistence in multiple contexts, including performance behaviors [26]. Similarly, it has been shown that the frustration of these basic psychological needs mediates the associations between controlled forms of motivation, behavioral distancing, and lower performance [34].

When employees lack motivation, the problem, most of the time, lies in one of five areas: in selection; in goal setting; in the performance evaluation system; in the reward system; or in the manager’s inability to align the employee’s perspectives with the performance evaluation and reward system [35].

Salary can have a significant impact on motivation; however, merely paying high salary levels does not guarantee motivation for performance. As Caetano and Vala [35] pointed out, individuals accustomed to high salaries tend not to give as much importance to money, and therefore, salary alone is not sufficient to motivate performance. Koopmans and colleagues [14] also asserted that, despite fixed compensation still prevailing in most organizations, it cannot motivate people; it functions only as a stable factor and does not encourage the acceptance of risks and responsibilities. It has become insufficient to motivate and encourage people to exhibit proactive, entrepreneurial, and effective behavior in the pursuit of goals and excellent results. Motivation continues to be a function of aspects such as the perception of mobility opportunities, flexible working hours, career advancement, positive relationships in the organization, and satisfaction with and at work, among other variables grounded in emotional salary and organizational benefits [30]. Other aspects to consider for achieving motivation at work include employment, professional development, autonomy and participation, work environment, working conditions, and recognition of achievements [36]. The rewards system and salary practices can have a greater or lesser impact on attracting and retaining individuals, potentially motivating performance-oriented behaviors [36]. One of the benefits of motivation at work is the commitment achieved by employees, as they tend to work in alignment with the management’s proposed strategy, contribute with innovative and creative ideas, and perform better [37].

Therefore, using the premises underlying the SDT, the following hypothesis was formulated:

Hypothesis 2.

Motivation mediates the positive relation between emotional salary and (a) adaptive, (b) task, and (c) contextual performance.

2.4. The Mediating Role of Satisfaction

Motivation appears to be a predictor of job satisfaction [38]. Among the proposed definitions, one of the most accepted and used in the literature is that of Locke [39]; according to him, satisfaction allows for a positive emotional state if the worker’s expectations, desires, and needs are fulfilled. For Locke [39], job satisfaction is related to the content of the job, promotion opportunities, recognition, working conditions, the work environment, relationships with others, supervision and leadership characteristics, and organizational policies (e.g., salary).

Job satisfaction is an indicator of the extent to which people enjoy their work [40]. Satisfaction itself is an attitude resulting from the interpretation of conditions or situations that allow individuals to meet their needs and interests [41]. In the workplace, this state is achieved through strategies implemented by companies that care about the needs of their employees [42] and ensure a positive work environment [43]. Thus, it can be concluded that satisfaction is an emotional response and an attitude that occurs as a result of the interaction between workers’ values regarding their work and the benefits gained from it, seen as a crucial condition for the effective performance of organizations [42,44].

Considering that job satisfaction can affect organizational processes, product quality, and expected productivity, workers are relevant resources that need to be kept motivated and satisfied [45] as they determine performance [46]. Job satisfaction has been linked to performance, as it corresponds to “more satisfied workers are more productive” [19]. Although monetary salary is an important factor, it is not the only one that promotes employee motivation and satisfaction [47]. Currently, the job market is much more competitive, and organizations must adopt strategies to adapt to the new challenges and interests of internal and external stakeholders [48]. Addressing individual needs of employees involves addressing the delivery of benefits that may be included in an emotional salary plan that contributes to increasing productivity, performance, and satisfaction levels [42].

Thereby, relying on the literature, the following hypothesis was defined:

Hypothesis 3.

Motivation mediates the positive relation between emotional salary and job satisfaction.

2.5. The Serial Mediation Model

Emotional salary is associated with non-monetarily compensated activities that can motivate employees, leaving them more satisfied and inclined to perform with increased productivity [49]. According to SDT, organizational practices like emotional salary management can help satisfy the needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness [7]. Managing emotional salary as a practice that creates conditions to meet workers’ needs is a motivational factor that autonomously determines performance-related behavior (e.g., helping a colleague) by leaving the individual more satisfied.

To understand the factors influencing performance, many researchers have studied practices such as fair compensation allocation or processes related to individual needs to satisfy such requirements [50]. Most studies have suggested that benefits (tangible and intangible) motivate individuals by satisfying their basic psychological needs [7]. Researchers have considered factors affecting an employee’s motivation and satisfaction. For example, emotional salary has been regarded as an important predictor of motivation for performance [51], with evidence demonstrating that motivation and satisfaction together are the strongest predictors of performance [52]. Other research focused on motivation, showing that motivated employees find it easier to regulate their emotions, feel satisfied, and be productive [53,54]. A meta-analysis by Kammeyer-Mueller and colleagues [55] also emphasized that satisfaction influences performance: those with higher satisfaction levels tend to be more committed to work and exhibit higher performance levels, while those with lower satisfaction levels tend to distance themselves from work and the organization, resulting in lower performance levels.

Thus, based on SDT and the literature, the following hypothesis was formulated:

Hypothesis 4.

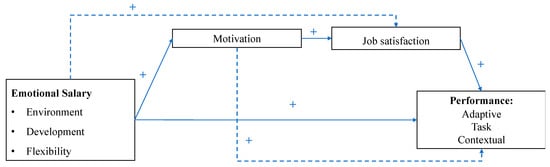

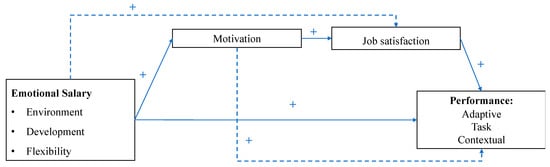

Emotional salary has a positive relation with (a) adaptive, (b) task, and (c) contextual performance through the mediation of motivation and, consequently, through job satisfaction (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The conceptual serial mediation model.

3. Methods

3.1. Procedure and Participants

The Ethics committee of the first author’s university approved the study before its conduction. For data collection, a questionnaire was developed and made available on the Google Forms platform, distributed electronically via email to contacts within the researchers’ professional network. Hence, a convenience non-probabilistic sampling was employed, using Portuguese workers. The electronic access to the form facilitated the efficiency of data acquisition. Before responding to the questionnaire, participants were provided with information about the study’s objectives and the assurance of anonymity and confidentiality. Participants were also asked to sign an informed consent form before receiving the questionnaire link; after signing and sending the consent via email, participants received a new email containing the link to the questionnaire. Out of the 303 emails sent, 215 valid responses were received (response rate = 71%). Data collection took place over a week, from 9 February 2023 to 16 February 2023.

From the overall sample, 69% were female with a mean age of 33 years old (SD = 11.91) and a mean organizational tenure of 11.57 years (SD = 11.18). Participants reported working about 38.56 h per week (SD = 13.32). Most participants had at least a graduate degree (51.6%) followed by those who had a high school diploma (42%).

3.2. Measures

To measure emotional salary, the Emotional Salary Questionnaire [5] was used. It included 18 items divided into three dimensions: environment (e.g., “developed friendships with colleagues”), development (e.g., “there are opportunities for career progression based on merit”), and flexibility (e.g., “has flexibility in working hours in case of emergencies”). We averaged the composite measure of overall emotional salary. Participants responded on a five-point Likert scale (1—never; 5—always). The scale’s Cronbach’s alpha was 0.95.

Performance was measured using two questionnaires. First, three items from the Individual Adaptive Performance Scale [13] were used to measure adaptive performance. An example item is “I adapt well to changes in main tasks.” Participants indicated their responses on a 5-point Likert scale (1—very little; 5—very much). The scale’s Cronbach’s alpha was 0.81. To measure contextual (e.g., “I take on challenging tasks when available”) and task performance (e.g., “I can manage my time well at work”), six items from the Individual Work Performance Questionnaire [14] were used. Responses were given on a 5-point Likert scale (1—never/almost never; 5—always/almost always). The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.74 (for contextual performance) and 0.73 for task performance.

To measure job satisfaction, three items from the Job Satisfaction Survey by Sharma and Stol [56] were used to measure satisfaction. An example item is “I am satisfied with my job.” Responses were given on a 5-point Likert scale (1—completely disagree to 5—completely agree). The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.74.

To measure motivation, the Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction at Work Scale [57] was used. Two items were used for measuring competence (e.g., “I have felt competent and capable.”), two for autonomy (e.g., “I have felt that I can be myself at work.”), and two for relatedness (e.g., “I feel close and connected to people at work.”). We averaged the composite measure of overall motivation. Responses were given on a 5-point Likert scale (1—not at all to 5—extremely). Cronbach’s alpha varied between 0.74 and 0.87.

Regarding control variables, sex, and age were used to control for the model’s effect, as some studies have shown variations in the mediating variables (motivation and satisfaction) and the criterion variable (performance) according to the participant’s age group and sex [24].

3.3. Data Analysis

To obtain results from the questionnaire used in the research, Google Forms, Excel, and the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, version 29; https://www.ibm.com/support/pages/downloading-ibm-spss-statistics-29, accessed on 5 January 2024) were employed. Initially, internal consistencies and descriptive analyses of the variables under study, along with their correlations, were examined. Subsequently, to test hypotheses 1a–c, linear regression analyses were conducted. Hypotheses 2 and 3 were tested using Model 4 from the PROCESS macro [58]. To examine hypothesis 4, i.e., the serial mediations, Model 6 from the PROCESS macro [58] was used. The variables were centered on their mean values, and the bootstrapping method (5000 times) was employed to obtain confidence intervals (CIs).

4. Results

4.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

First, the multivariate normality was assessed by checking Mardia’s statistics [59] using the Web Power tool available at https://webpower.psychstat.org/models/kurtosis/ (accessed on 5 January 2024). This gives information about the skewness and kurtosis coefficients and the p-value. Byrne [60] emphasized that Mardia’s standardized coefficient should be greater than the threshold of 5 (p > 0.05) to consider the data to be normally distributed. The result showed that the data followed multivariate normality (Mardia’s coefficient skewness = 14.00, p > 0.05; Mardia’s coefficient kurtosis = 142.16, p > 0.05). Further, we performed a full collinearity test, whereby the highest pathological VIF for all constructs was 2.13, which is below the recommended threshold of 3.3 [61]; plus, tolerance values ranged between 0.3 and 0.72; hence, multicollinearity was not an issue in this study.

Second, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to test if the variables were empirically distinct. Various model fit indices were considered to assess their acceptability. A model is considered acceptable if the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) is <0.06, the comparative fit index (CFI) is >0.90, the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) is >0.90, and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) is <0.08 [62]. Moreover, having three to four fit indices within acceptable ranges is considered sufficient evidence for model fit [63]. The result revealed that the four-factor measurement model (emotional salary [environment, development, flexibility], motivation [autonomy, competence, relationship needs], job satisfaction, and performance [adaptive, task, contextual]) had the best fit to the data (χ2/df = 2.56, RMSEA = 0.08, CFI = 0.98, TLI = 0.98, SRMR = 0.07). It was also compared with indices from alternative models: the three-factor model (combining motivation and job satisfaction into a single latent factor along with emotional salary and performance) (χ2/df = 3.78, RMSEA = 0.11, CFI = 0.97, TLI = 0.96, SRMR = 0.10) and the two-factor model (combining motivation, job satisfaction, and performance into a single latent factor along with emotional salary) (χ2/df = 4.63, RMSEA = 0.13, CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.96, SRMR = 0.10). Finally, a single-factor model combining all four variables as a single latent factor was created. Comparing the goodness-of-fit statistics of the single-factor model with the proposed model indicated insufficient fit (χ2/df = 8.30, RMSEA = 0.18, CFI = 0.92, TLI = 0.92, SRMR = 0.14). This result also suggests that common method bias did not pose a significant threat in this study.

4.2. Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics, along with correlations and internal consistency indices for the variables under study. According to Field [64], relatively small standard deviations compared to the mean scores suggest that the calculated means represent the observed data. The result of skewness and kurtosis levels shows that variable values were not greater than 10 [65]. From the measurement model, composite reliability, discriminant validity, convergent validity, and bivariate correlations of the variables under study are presented in Table 1. As we can see, the composite reliability of variables was above the recommended threshold of 0.70, in line with Fornell and Larcker [66]. The results of the convergent validity, measuring how indicators of the latent construct correlate with each other, revealed that the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) for all latent constructs in the study was above 0.5. Discriminant validity also demonstrated that indicators for each latent variable are distinct (see CFA results). Thus, reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity were confirmed for this study. Based on the validity of the instruments used, hypotheses were then tested.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics.

4.3. Hypotheses Testing

To test the hypothetical model, a hierarchical linear regression analysis was conducted. Additionally, the procedure proposed by Taylor et al. [67] was followed to test serial mediation. For the first hypothesis, emotional salary was regressed on performance (adaptive, task, and contextual). To test hypothesis 2 (indirect effect of emotional salary on performance via motivation), performance was regressed on motivation while controlling for emotional salary. To test hypothesis 3 (indirect effect of emotional salary on job satisfaction via motivation), job satisfaction was regressed on motivation while controlling for the effect of emotional salary. Finally, to test hypothesis 4 (indirect effect of emotional salary on performance through motivation and job satisfaction), performance was regressed on job satisfaction while controlling for the effects of emotional salary and motivation. The proposed indirect effect for hypotheses 2, 3, and 4 was examined through confidence interval estimates (CIs) corrected using bootstrap analysis (5000 bootstrap samples). The results are described in Table 2.

Table 2.

Hypothesis testing: results of the regression and indirect effects on adaptive performance.

Hypothesis 1: Hypothesis 1 assumed that emotional salary significantly predicted (a) adaptive, (b) task, and (c) contextual performance. The results of linear regression showed that emotional salary had a positive and significant relation with (a) adaptive performance (B = 0.50, F (1,213) = 92.54, p < 0.001 with R2 = 0.30), (b) task performance (B = 0.43, F (1,213) = 52.45, p < 0.001 with R2 = 0.19), and (c) contextual performance (B = 0.42, F (1,213) = 56.61, p < 0.001 with R2 = 0.21). Thus, hypotheses 1a–c were supported by the data.

For hypotheses 2a–c, bootstrap analysis results showed that the indirect effect of emotional salary on (a) adaptive, (b) task, and (c) contextual performance through motivation was significant (adaptive performance: B = 0.11; SE = 0.04, p < 0.01; 95% CI [0.05, 0.19]; task performance: B = 0.15; SE = 0.04, p < 0.01; 95% CI [0.08, 0.25]; and contextual performance: B = 0.10; SE = 0.04, p < 0.01; 95% CI [0.04, 0.18]), supporting hypotheses 2a–c (see Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4).

Table 3.

Hypothesis testing: results of regression and indirect effects on task performance.

Table 4.

Hypothesis testing: results of regression and indirect effects on contextual performance.

The results for hypothesis 3 also showed that the indirect effect of emotional salary on job satisfaction through motivation was significant (B = 0.11, SE = 0.04, 95% CI [0.05, 0.19]). Therefore, hypothesis 3 was supported by the data.

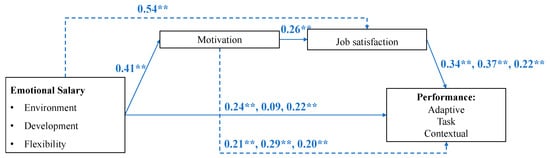

Finally, results for hypothesis 4 (a–c) revealed that the serial indirect effect of emotional salary on (a) adaptive, (b) task, and (c) contextual performance through motivation and job satisfaction was significant (adaptive performance: B = 0.03; SE = 0.01, p < 0.01; 95% CI [0.01, 0.06]; task performance: B = 0.04; SE = 0.02, p < 0.01; 95% CI [0.01, 0.07]; and contextual performance: B = 0.03; SE = 0.01, p < 0.01; 95% CI [0.01, 0.05]), thus supporting hypothesis 4a–c (see Figure 2 for a summary of results).

Figure 2.

The serial indirect effect results. ** p < 0.01.

5. Discussion

This study examines how emotional salary, as an organizational strategy, influences performance (task, adaptive, and contextual). It hypothesizes a serial indirect effect in which the satisfaction of three basic psychological needs and job satisfaction are identified as explanatory mechanisms in the relation between emotional salary and performance.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

First, the results show that emotional salary has a positive relation with (a) adaptive, (b) task, and (c) contextual performance. In other words, the more organizations invest in the strategy of creating emotional salary policies for their employees, the higher their task, adaptive, and contextual performance tends to be. Despite there being few studies on the role of emotional salary, Peñafiel and Zambrano [68] demonstrated that it positively influenced the performance of workers in public institutions. Thus, emotional salary can be a precursor to task, adaptive, and contextual performance.

Second, emotional salary has an indirect effect on performance through workers’ motivation. That is, emotional salary practices motivate workers to do more and better, as evidenced by higher levels of task, contextual, and adaptive performance. Managing emotional salary not only contributes to the organization’s competitiveness but also motivates and values employees, encouraging them to seek a humane and balanced work activity. Similar to other motivating job characteristics (autonomy), emotional salary may sustain employees’ motivational states and encourage them to do more and better [69]. Thus, in general, it can be concluded that managing emotional salary involves motivating workers, and this motivation, in turn, translates into higher levels of performance.

Third, emotional salary has an indirect effect on job satisfaction through motivation. This means that managing an emotional salary not only motivates workers but also tends to make them more satisfied. Emotional salary is any form of non-monetary compensation, remuneration, or consideration that a worker receives in exchange for their work. This non-monetary compensation involves considering specific factors of the worker, such as their family, hobbies, and emotional and physical state, and recognizing that each worker is an individual with different needs [70]. Similarly, Carpio and colleagues [71] demonstrated the positive impact of emotional salary on the job satisfaction of workers in small and medium-sized enterprises. Additionally, Solís Granda and Burgos Villamar [72], in their literature review, showed a significant positive correlation between emotional salary and job satisfaction. Therefore, emotional salary should contribute positively to worker motivation and satisfaction.

Finally, the results show that emotional salary has a positive indirect relation with (a) adaptive, (b) task, and (c) contextual performance through motivation and, consequently, job satisfaction. It can be observed that, in general, emotional salary influences motivation, which, in turn, makes individuals more satisfied with their work and, consequently, enhances their performance. In other words, emotional salary influences performance (task, contextual, and adaptive) by increasing motivation and job satisfaction. These results reinforce the importance of emotional salary from the perspective of individual appreciation and organizational competitiveness. When organizations have more motivated and satisfied workers who strive for distinctive performance, they can achieve greater profitability and organizational success [71]. Emotional salary is a non-economic reward composed of extrinsic and intrinsic factors that motivate and satisfy the expectations and needs of workers, providing them with well-being and willingness to contribute more to the organization [73]. In summary, even though it is an underexplored topic [44], it appears that emotional salary, motivation, and satisfaction influence employees’ performance, leading to increased productivity and positive results for the organization.

5.2. Practical Implications

Emotional salary is a variable that appears to be relevant in the workplace for keeping workers motivated, satisfied, and consequently, more engaged with their work and the company’s objectives. It appears that organizations should pay attention to salary benefits and how they can motivate and satisfy workers, taking into account the individual needs of each one.

Despite the seemingly positive results of emotional salary, national and international companies still hesitate to implement it, considering it an expense rather than an investment. For instance, providing career plans, creating a relaxation space for employees, and offering gift vouchers, among other benefits, are viewed as an investment. Additionally, there is uncertainty about whether these changes guarantee the retention, performance, and motivation of employees [6].

It is becoming increasingly necessary for companies to resort to these methods to gain a competitive advantage and generate human value. In a competitive world, it is crucial to value and understand the needs of workers so that the organization can achieve the desired results through implemented objectives. Many companies consider emotional salary an essential factor in the organization. For example, Millennium BCP offers various benefits to its employees, such as medical treatments at the Navarra clinic and fully paid trips and accommodation for both the employee and their family [74]. Somague, for instance, implements benefits that motivate employees, including health insurance and private transportation. They also provide three extra days of vacation, payments for Via Verde, childcare allowance, and gym memberships [75]. However, before considering the implementation of emotional salary management, it is crucial to diagnose the needs of the organization’s workers first. This ensures that benefits align with what each individual needs and values. Failure to do so may result in the benefits gained through emotional salary being lost.

For several years, some institutions have been investigating this topic, and only recently has the need for reconciliation and harmonization between personal and professional life been recognized. It is crucial for organizations to value this initiative and prioritize the well-being of their employees so that they can attract, retain, and capitalize on talent within the organization.

5.3. Limitations and Future Directions

One limitation of this study is the use of self-report measures and the limited sample size. The small sample size makes it challenging to generalize the obtained results. On the other hand, the use of self-report measures can introduce common method bias. However, Junça-Silva and Menino [30] suggested that self-reports are a suitable method to collect data on internal affective states, such as motivation and satisfaction. Plus, measures were taken to understand the degree of common method bias in the data. According to the indicators from confirmatory analyses, common method bias does not appear to be a significant issue in the sample.

Moreover, despite the use of composite variables (emotional salary and motivation), the indirect effects between the specific dimensions present the same pattern of results.

Furthermore, the cross-sectional nature of the data and the convenience sampling design were also limitations that can limit the generalizability of the findings. Therefore, future research should conduct longitudinal studies to cross-validate the findings.

Additionally, various professional occupations were covered; hence, it will be necessary to test the model in different sectors and professional areas to determine if there are sectors where the influence is more pronounced than others. For example, in the retail and food industries, a major motivation challenge is the fact that workers receive very low wages, and the chances of promotions or other benefits are limited. The more conventional approaches observed in these sectors include offering flexible schedules and job opportunities for students or individuals with lower financial needs.

It will also be important to consider studying the application of various salary benefits in different professional areas and age ranges to understand how they can influence motivation and, consequently, the performance of workers in equal or different ways.

Therefore, given the known positive relation of emotional salary with performance and how it influences motivation and satisfaction, future studies should aim to identify how organizations can implement this method, taking into account the needs of each worker, so that they feel motivated and satisfied in their professional and personal lives.

6. Conclusions

Overall, the findings appear to show that when emotional salary is promoted, employees satisfy their psychological needs of autonomy, competence, and relatedness, which leaves them satisfied with their work and, as a result, improves their performance (adaptive, task, and contextual). Thus, one may conclude that emotional salary practices are a form of sustainable practices that enhance not only employees’ motivation but also their performance. All in all, this contributes to both employees and organizations which means that emotional salary may be a sustainable investment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.J.S.; Methodology, A.J.S., A.R.B. and J.F.d.C.; Validation, J.F.d.C.; Formal analysis, A.J.S.; Investigation, A.R.B. and J.F.d.C.; Data curation, A.R.B.; Writing—original draft, A.J.S.; Visualization, J.F.d.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, grant UIDB/00315/2020 (DOI: 10.54499/UIDB/00315/2020).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of ISCTE—Instituto Universitário de Lisboa (protocol code 09012022, September 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Blanch, G.S. El Salario Emocional Para el Equilibrio de la Vida Personal y Profesional en los Centro Universitarios. Tese de Doutoramento; Facultat de Psicologia, Ciències de L’Educació e de L’Esport Blanquerna, Universitat Ramon Llull: Barcelona, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Huete, L.M. Servicios y Beneficios; Deusto: Barcelona, Spain, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, C.M.; Cagua, N.Y.; Gómez, Y.C. Cornisa: Modelo de Salario Emocional Para Cardiocolombia S.A.S.; Universidade de Bogotá Jorge Tadeo Lozano: Bogotá, Colombia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, C. El Salario Emocional. Borrador de Administración, nº 47; Colegio de Estudios Superiores de Administración: Bogotá, Colombia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Salvador-Moreno, J.E.; Torrens-Perez, M.E.; Vega-Falcon, V.; Norona-Salcedo, D.R. Diseño y validación de instrumento para la inserción del salario emocional ante la COVID-19. Rev. De Cienc. De La Adm. Y Econ. 2021, 11, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza, A.K.; Moctezuma, J.A. Salario Emocional: Una solución alternativa para la mejora del rendimiento laboral. Nova Rua 2020, 12, 72–89. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory. In Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness; American Psychological Association Inc.: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- García, S.M. La Satisfacción Laboral en Relación con el Salario Emocional. Dissertação; Faculdade de Direito, Universidade de La Laguna: La Laguna, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Gomez, M.; Breso, E.; Giorgi, G. Could Emotional Intelligence Ability Predict Salary? A Cross-Sectional Study in a Multioccupational Sample. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puyal, F.G. El salario emocional, clave para reducir el estrés. Gestión Práctica De Riesgos Laborales Integr. Y Desarollo De La Gestión De La Prevención 2006, 33, 44–47. [Google Scholar]

- González, F.; De Avice, A.D. Qué es y cómo se paga el salario emocional. Rev. De Neg. Del IEEM 2017, 80. Available online: https://www.hacerempresa.uy/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/IEEM-agosto-RRHH.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2024).

- Rocco, M. Satisfacción Laboral y Salario Emocional: Una Aproximación Teórica. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidade de Chile, Santiago, Santiago, Chile, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, M.A.; Neal, A.; Parker, S.K. A New Model of Work Role Performance: Positive Behavior in Uncertain and Interdependent Contexts. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 327–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopmans, L.; Bernaards, C.M.; Hildebrandt, V.H.; Van Buuren, S.; Van der Beek, A.J.; De Vet, H.C. Improving the individual work performance questionnaire using rasch analysis. J. Appl. Meas. 2014, 15, 160–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cró, F.L. A Relação da Autoeficácia e da Autonomia com o Desempenho Adaptativo: O Papel Mediador da Satisfação no Trabalho; ISPA—Instituto Universitário Ciências Psicológicas, Sociais e da Vida: Lisboa, Portugal, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rosa, A.P. Análise da Mediação do Desempenho Contextual na Relação Entre a Prestação de Contas e o Bem-Estar Afetivo no Trabalho e do Papel Moderador da Cultura de Gestão do Erro; ISPA—Instituto Universitário: Lisboa, Portugal, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sonnentag, S.; Volmer, J.; Spychala, A. Job performance. Sage Handb. Organ. Behav. 2008, 1, 427–447. [Google Scholar]

- Blau, P. Exchange and Power in Social Life; Wiley: New York, NJ, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Cropanzano, R.; Anthony, E.L.; Daniels, S.R.; Hall, A.V. Social Exchange Theory: A Critical Review with Theoretical Remedies. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2017, 11, 479–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Quispe, B.L.; Roque Barrios, D.N. El salario emocional y la satisfacción laboral. Impuls. Rev. de Adm. 2022, 2, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervantes, M. Las Ventajas de la Empresa Flexible. UCJC Business and Society Review (Formerly Known as Universia Business Review), (5). 2005. Available online: https://journals.ucjc.edu/ubr/article/view/524 (accessed on 7 January 2024).

- Buqueras, I.; Cagigas, J. Dejemos de Perder el Tiempo: Los Beneficios de Optimizar los Horarios; Lid Editorial: Madrid, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, A. La relación salarios-productividad: Incentivos salariales en los convenios colectivos industriales. Trab. Y Soc. 2016, 26, 5–22. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The “What” and “Why” of Goal Pursuits: Human Needs and the Self-Determination of Behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Self-determination theory. In Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology; Sage Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012; Volume 1, pp. 416–436. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, J.Y.; Ntoumanis, N.; Thøgersen-Ntoumani, C.; Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M.; Duda, J.L.; Williams, G.C. Self-determi- nation theory applied to health contexts: A meta-analysis. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2012, 7, 325–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patrick, H.; Williams, G.C. Self-determination theory: Its application to health behavior and complementarity with motivational interviewing. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2012, 9, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guimarães, S.E.; Bzuneck, J.A. Propriedades psicométricas de um instrumento para avaliação da motivação de universitários. Ciências Cognição Ilha Do Fundão 2008, 13, 101–113. [Google Scholar]

- Junça-Silva, A. The Furr-Recovery Method: Interacting with Furry Co-Workers during Work Time Is a Micro-Break That Recovers Workers’ Regulatory Resources and Contributes to Their Performance. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Junça-Silva, A.; Menino, C. How Job Characteristics Influence Healthcare Workers’ Happiness: A Serial Mediation Path Based on Autonomous Motivation and Adaptive Performance. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagné, M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and work motivation. J. Organ. Behav. 2005, 26, 331–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, K.M.; Elliot, A.J.; Kim, Y.; Kasser, T. What is satisfying about satisfying events? Testing 10 candidate psychological needs. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 80, 325–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Sin, S.-C.J.; Theng, Y.-L.; Lee, C.S. Why Students Share Misinformation on Social Media: Motivation, Gender, and Study-level Differences. J. Acad. Libr. 2015, 41, 583–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haerens, L.; Aelterman, N.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Soenens, B.; Van Petegem, S. Do perceived autonomy-supportive and controlling teaching relate to physical education students’ motivational experiences through unique pathways? Distinguishing between the bright and dark side of motivation. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2015, 16, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caetano, A.; Vala, J. Gestão de Recursos Humanos—Contextos, Processos e Técnicas, 3rd ed.; Editora RH, Lda: Lisboa, Portugal, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Shukla, S.A. Employee engagement-role of demographic variables and personality factors. Amity Glob. HRM Rev. 2015, 5, 66–73. [Google Scholar]

- Quispe, E.L. La Motivación laboral en la productividad empresarial. Voz Zootenista 2014, 4, 28–30. [Google Scholar]

- Saifuddin Khan Saif, D.A. Synthesizing the theories of Job-Satisfaction across the Cultural/Attitudinal Dementions. Interdiscip. J. Contemp. Res. Bus. 2012, 3, 1382–1396. [Google Scholar]

- Locke, E.A. The nature and causes of job satisfaction. In Em M. Dunnette, Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology; M.D. Dunnette: Chicago, IL, USA, 1976; Volume 1, pp. 1297–1343. [Google Scholar]

- Alegre, I.; Mas-Machuca, M.; Berbegal-Mirabent, J. Antecedents of employee job satisfaction: Do they matter? J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 1390–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcon, H.R.; Cea, B.G. Diseño y validación de un modelo de medición del clima organizacional basado en percepciones y expectativas. Rev. Ing. Ind. 2007, 6, 6. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=5006105 (accessed on 7 January 2024).

- Cordero-Guzmán, D.B.-T.-P. Cultura organizacional y salario emocional. Rev. Venez. De Gerenc. 2022, 27, 132–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.J.; Pinto, D. Training under an extreme context: The role of organizational support and adaptability on the motivation transfer and performance after training. Pers. Rev. 2024; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, G.; Almorza Gomar, D.; González Arrieta, G. How does Emotional Salary Influence Job Satisfaction? A Construct to be Explored. Anduli Rev. Andal. Cienc. Soc. 2023, 23, 57–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, J.A.E.; Melo, F.M. O clima organizacional e a satisfação dos funcionários de um Centro Médico Integrado. Rev. Psicol. Organ. E Trab. 2003, 3, 11–26. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, D.; Ruch, W. Fusing character strengths and mindfulness interventions: Benefits for job satisfaction and performance. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2019, 24, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restrepo, P.L. La flexibilidad laboral y el salario emocional. Aglala 2014, 5, 34–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmedo, P. El Empleo en el Ecuador-Una Mirada a la Situación y Perspectivas para el Mercado Laboral Actual; Fiedrich Ebert Stittung: Bonn, Germany, 2018; pp. 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Lópera, I.C.P.; López, C.Q.; Santacruz, J.S.R. Development of an emotional salary model: A case of application. Indian J. Sci. Technol. 2019, 12, 10–17485. [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel, A.S.; Cheshin, A.; Moran, C.M.; van Kleef, G.A. Enhancing emotional performance and customer service through human resources practices: A systems perspective. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2016, 26, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabbott, M.; Tsarenko, Y.; Mok, W.H. Emotional intelligence as a moderator of coping strategies and service outcomes in circumstances of service failure. J. Serv. Res. 2011, 14, 234–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, D.L.; Newman, D.A. Emotional intelligence: An integrative meta-analysis and cascading model. J. Appl. Psychol. 2010, 95, 54–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, N.-W.; Grandey, A.A.; Diamond, J.A.; Krimmel, K.R. Want a tip? Service performance as a function of emotion regulation and extraversion. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 1337–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T.A.; Woolf, E.F.; Hurst, C. Is emotional labor more difficult for some than for others? A multilevel, experience-sampling study. Pers. Psychol. 2009, 62, 57–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kammeyer-Mueller, J.D.; Rubenstein, A.L.; Long, D.M.; Odio, M.A.; Buckman, B.R.; Zhang, Y.; Halvorsen-Ganepola, M.D.K. A Meta-Analytic Structural Model of Dispositonal Affectivity and Emotional Labor. Pers. Psychol. 2012, 66, 47–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G.G.; Stol, K.J. Exploring onboarding success, organizational fit, and turnover intention of software professionals. J. Syst. Softw. 2020, 159, 110–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M.; Gagné, M.; Leone, D.R.; Usunov, J.; Kornazheva, B.P. Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction at Work Scale (BPNS-W); APA Psyctests. 2001. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2Ft71065-000 (accessed on 7 January 2024).

- Hayes, A.F. Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Commun. Monogr. 2018, 85, 4–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardia, K.V. 9 Tests of unvariate and multivariate normality. Handb. Stat. 1980, 1, 279–320. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, G. A Statistical Primer: Understanding Descriptive and Inferential Statistics. Évid. Based Libr. Inf. Pract. 2007, 2, 32–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N.; Lynn, G.S. Stevens Institute of Technology Lateral Collinearity and Misleading Results in Variance-Based SEM: An Illustration and Recommendations. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2012, 13, 546–580. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Gabriel, M.L.; Patel, V.K. Modelagem de Equações Estruturais Baseada em Covariância (CB-SEM) com o AMOS: Orientações sobre a sua aplicação como uma Ferramenta de Pesquisa de Marketing. Rev. Bras. Mark. 2014, 13, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publication: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 2nd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, A.B.; MacKinnon, D.P.; Tein, J.-Y. Tests of the Three-Path Mediated Effect. Organ. Res. Methods 2007, 11, 241–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñafiel, J.V.I.; Zambrano, M.I.Z. Análisis del salario emocional y su impacto en el rendimiento del talento humano de las instituciones públicas de Portoviejo, Ecuador: Analysis of the emotional salary and its impact on the performance of human talent in the public institutions of Portoviejo. Ecuador. Rev. Espac. 2023, 44, 59–75. [Google Scholar]

- Junça-Silva, A.; Caetano, A. Uncertainty’s impact on adaptive performance in the post-COVID era: The moderating role of perceived leader’s effectiveness. BRQ Bus. Res. Q. 2023, 27, 40–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Cardona, I.; Vera, M.; Marrero-Centeno, J. Job resources and employees’ intention to stay: The mediating role of meaningful work and work engagement. J. Manag. Organ. 2021, 29, 930–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpio, D.A.; Urbano, B. How to foster employee satisfaction by means of coaching, motivation, emotional salary and social media skills in the agri-food value chain. New Medit Mediterr. J. Econ. Agric. Environ. Rev. Méditerranéenne Dʹeconomie Agric. et Environ. 2021, 20, 39–56. [Google Scholar]

- Solís Granda, L.E.; Burgos Villamar, I.S. Emotional salary in the job satisfaction of SME employees. Bibliographical review. Podium 2023, 43, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valero, E.R.; Jiménez, M.B. El salario emocional. Una revisión sistemática a la literatura: The Emotional salary. A systematic review of the literature. InnOvaciOnes NegOciOs 2023, 20, 102–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taborda, A. A Minicidade BCP, nº 277; Exame: Tokyo, Japan, 2007; p. 58. [Google Scholar]

- Camara, P.; Guerra, P.B.; Rodrigues, J.V. Novo Humanator—Recursos Humanos e Sucesso Empresarial; Dom Quixote: Lisboa, Portugal, 2007. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).