Human-Centric and Integrative Lighting Asset Management in Public Libraries: Insights and Innovations on Its Strategy and Sustainable Development

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology, Hypothesis, Review, and SDG Alignment

2.1. Research Methodology, Focus, and Scope

- State-of-the-Art Review: We conducted an exhaustive review of the existing literature to establish a solid theoretical foundation. This review spanned various dimensions of human-centric and integrative lighting, the complexities of lighting asset management, and current standards in library lighting.

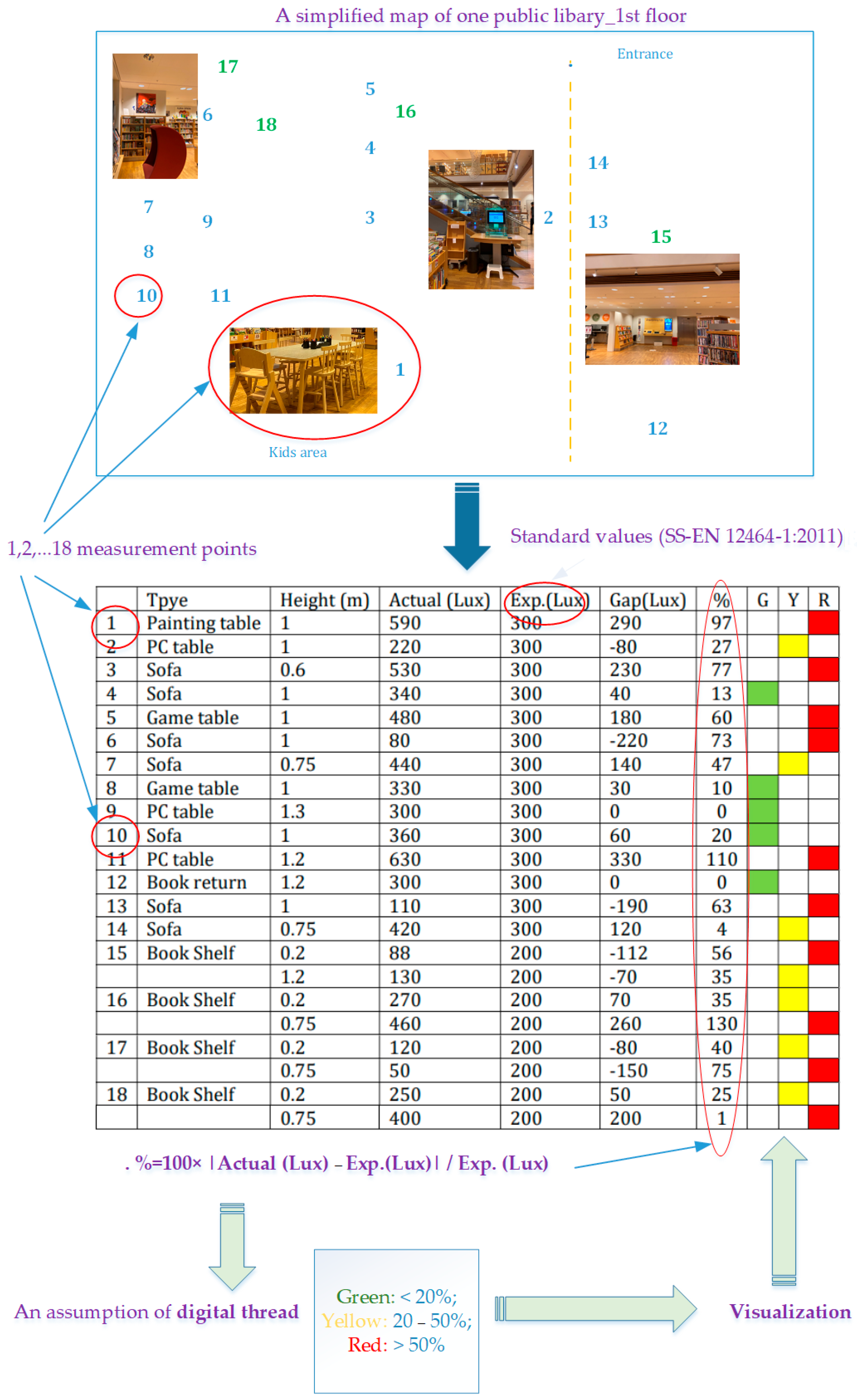

- On-Site Observations: Detailed observations were made in 20 Swedish public libraries. These observations aimed to uncover both the evident and subtle challenges in the lighting environment, capturing the user perspective through participant observations. These findings were instrumental in shaping our understanding of the practical aspects of library lighting.

- Stakeholder Engagements: Our research included comprehensive interactions with diverse stakeholders, encompassing interviews and surveys with lighting professionals, library staff, and users. Over 100 responses were collected during these engagements, providing valuable insights into the real-world application of lighting strategies in libraries.

2.2. Connecting Hypotheses with the Study’s Aim and Content

- Hypothesis 1 and Optimization of Lighting Environments: The first hypothesis directly supports our aim by proposing that such lighting strategies can optimize library environments. Our research methodology includes context identification and user feedback analysis to validate this hypothesis, thereby contributing to the optimization of lighting environments.

- Hypothesis 2 and Alignment with SDGs: The second hypothesis is explored through our study’s component that evaluates how lighting strategies in libraries can contribute to global sustainability objectives. By demonstrating this alignment, the study reaffirms its aim of advocating light as a tool for comprehensive human betterment.

- Hypothesis 3 and Effective Management Strategies: The third hypothesis is directly related to our study’s exploration of a management framework and the application of ISO 55000 principles. By examining the effectiveness of staff training and awareness programs, our study aims to reinforce the role of the lighting asset manager and the implementation of foundational strategies for optimal lighting management.

2.3. State-of-the-Art Review

2.4. Alignment with Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

3. Context Identification in Public Library Settings

3.1. Context I: External Environmental Factors

- Geographic Location: The amount and quality of natural light available in a certain location can greatly affect integrative lighting design. Locations closer to the equator receive more sunlight year-round than those closer to the poles, influencing the amount and type of artificial lighting needed.

- Seasonal Changes: Changes in seasons can affect the amount of natural daylight available, which can influence the timing and intensity of artificial lighting. For instance, during winter months, more artificial lighting may be needed.

- Circadian Rhythms: Light has a significant impact on our circadian rhythms, which are physical, mental, and behavioral changes following a daily cycle. Properly timed and tuned lighting can support healthy circadian rhythms, improving sleep and overall health. For example, cooler, brighter light in the morning can help increase alertness, while warmer, dimmer light in the evening can promote relaxation.

- Occlusion Effects: This refers to how buildings or other structures might block sunlight. If a building is in a location where other structures block sunlight, the interior may require more artificial lighting or innovative solutions to direct natural light indoors.

- Sunlight Intensity: Sunlight intensity directly influences the amount and type of artificial lighting needed. On brighter days, less artificial lighting might be required, and the lighting system should be adaptable to these changes to save energy and maintain comfort.

- Temperature Variations: Extreme temperatures can affect the performance of some lighting technologies. For example, LED efficiency improves at lower temperatures, while high temperatures can reduce the lifespan of the light source.

- Humidity: Humidity can also impact the efficiency and lifespan of certain lighting systems. High humidity can cause some lights to fail earlier or may require more robust fixture designs.

- Air Quality: Poor air quality, such as high levels of dust or pollution, can scatter and absorb light, reducing its effectiveness. This may necessitate more or stronger lighting to achieve the same level of visibility. Also, poor air quality might cause faster degradation of lighting fixtures, necessitating more frequent maintenance or replacement.

3.2. Context II: Interior Design Factors

- Building:

- ○

- Building Material Characteristics: The materials used in the construction and interior design of a building can significantly impact how light behaves in the space. Lighter materials reflect more light, which can help illuminate a space naturally and reduce the need for artificial light. The texture and color of the materials also influence the color and quality of reflected light.

- ○

- Daylight Interaction: The amount and quality of natural light in a building depend on the design and orientation of the building, including the size, type, and placement of windows, skylights, and other openings. Optimizing this interaction can create a more pleasant and productive environment, reduce energy consumption, and help regulate occupants’ circadian rhythms.

- Furniture (Excluding Bookshelf). In our study, we initially categorized furniture and bookshelves separately, although their influence on lighting considerations appears similar. Our rationale for this distinction lies in the different user interactions and durations associated with these elements. Typically, users spend more time using furniture, such as chairs or sofas, for activities like reading or learning, compared to the relatively shorter time spent at bookshelves searching for books. This difference in usage significantly impacts the considerations for human-centric lighting solutions, as areas with prolonged user presence, like seating areas, have a more pronounced effect on human health and well-being:

- ○

- Furniture Position: The positioning of furniture can affect the distribution and reflection of light in the space. It can cause shadows or glare, depending on its location relative to light sources.

- ○

- Furniture Characteristics: The color, material, and texture of furniture can also influence how light is reflected or absorbed, affecting the overall illumination of the space.

- Bookshelf:

- ○

- Bookshelf Position: The positioning of bookshelves can impact light distribution, potentially creating shadowy areas that require additional lighting.

- ○

- Bookshelf Characteristics: The material and color of the bookshelves can affect how much light they reflect or absorb. Darker shelves may require more lighting for people to see the books clearly.

- Fixed Lighting:

- ○

- Lighting Position: The position of fixed lighting affects the distribution of light, which can impact visibility and create different moods or effects.

- ○

- Lighting Characteristics: The type of light bulbs used (LED, fluorescent, incandescent, etc.) and their color temperature and luminosity can significantly impact the ambiance of the space.

- ○

- Human–Lighting Interactivity: This refers to how individuals can interact with and control the lighting system. Effective systems allow users to adjust lighting to their needs, enhancing comfort and productivity.

- Adjustable Lighting:

- ○

- Lighting Characteristics: Adjustable lighting offers flexibility, allowing individuals to modify lighting conditions according to their needs or preferences, including brightness, direction, and color.

- ○

- Human–Lighting Interactivity: As with fixed lighting, the ability for individuals to interact with and control adjustable lighting can significantly enhance the usability and comfort of a space, making it more human-centric.

3.3. Context III: User Factors

- Asset Manager:

- ○

- Guidance to Operators and Customers: The asset manager’s role in providing clear instructions regarding the operation and benefits of the lighting system is crucial. This guidance can help operators use the lighting system more effectively and can help customers understand the intent behind the lighting design. For example, explaining the benefits of circadian lighting might encourage customers to appreciate and benefit from different lighting settings throughout the day.

- Operator:

- ○

- Operators’ Behavior on Lighting: How the operator uses and controls the lighting system can greatly affect the lighting conditions in a space. This includes turning lights on or off, adjusting brightness or color temperature, and managing natural light. If operators understand and value the concepts of integrative/human-centric lighting, they are more likely to implement lighting changes that promote comfort, health, and productivity.

- Customer:

- ○

- Age: Lighting needs can vary with age. A human-centric lighting design considers the diverse needs of different age groups. For instance, in areas of the library like the magazine and newspaper section, which are frequently used by older adults, implementing lighting with higher illuminance would be more appropriate. This approach not only caters to their specific visual requirements but also enhances their overall library experience.

- ○

- Gender: Although it is not a primary factor, there are studies suggesting that gender may influence light perception and preferences, which should be considered in an integrative/human-centric approach. An existing gender difference in color preference for lighting could be a critical factor in enhancing certain areas of the library. For instance, considering that the staff at library counters are predominantly female, tailoring the lighting in these areas to align with research findings on color preferences among women could improve the working environment. This might involve adjusting the color temperature of the lighting to create a more comfortable and visually appealing workspace for the staff, thus acknowledging and addressing gender-specific preferences in lighting.

- ○

- Height: This can influence how individuals perceive a space, including lighting. For example, higher-positioned lights might create shadows that shorter individuals find disruptive.

- ○

- Activities: Different activities require different lighting conditions. For instance, reading requires focused, brighter light, while a social gathering might benefit from softer, more diffuse lighting.

- ○

- Customer’s Behavior: The way customers interact with the lighting system, their preferences, and their feedback can provide valuable information for improving the lighting design. If customers tend to adjust the lighting a certain way, or if they express comfort or discomfort with certain settings, these cues can guide adjustments to better meet their needs.

3.4. Context IV: Cost Factors

- Energy Consumption: One of the main costs associated with lighting is energy consumption. Efficient lighting technologies, such as LEDs, can reduce this cost significantly. However, the interplay between natural light and artificial light in integrative lighting design can also help optimize energy use. For instance, the use of daylight sensors can reduce the need for artificial light during the day, which can lower energy costs.

- Purchase: The initial purchase cost of lighting systems can vary significantly. More advanced, energy-efficient, and adjustable lighting systems may have a higher upfront cost, but they may offer greater benefits in terms of energy savings, lifespan, and user satisfaction in the long run.

- Installation: The complexity of the lighting system will influence the installation cost. Integrative lighting systems often involve a combination of different light sources, controls, and sensors, which may require professional installation. However, well-planned installations can provide long-term benefits in terms of energy efficiency, ease of use, and comfort.

- Operation: Operating costs include the regular cost of energy, as well as any costs associated with the control systems used to adjust the lighting. Smart controls can help optimize energy use and adapt the lighting to the needs and preferences of users, which can lead to increased satisfaction and productivity, potentially offsetting some of the operational costs.

- Maintenance: All lighting systems require some level of maintenance, including cleaning, bulb replacement, and potential repairs. While some lighting technologies, like LEDs, have longer lifespans and lower maintenance requirements, they still need to be considered in the overall cost. The design of an integrative lighting system should consider ease of maintenance to minimize disruption and cost.

3.5. Context IV: Regulation Factors

- Asset Management Strategies/Regulations: Efficient asset management strategies and regulations can significantly improve the performance and lifespan of a lighting system. This includes regular maintenance schedules, inventory management, and compliance with safety regulations. Proper asset management ensures that the lighting system operates optimally, reducing the likelihood of malfunctions that can disrupt the human-centric lighting experience.

- Circular Economy/Sustainability/Societal Impacts: In a circular economy, products are designed to be used as long as possible, and at the end of their life, the components are reused or recycled. When it comes to lighting, this means choosing durable, energy-efficient lighting systems that can be easily repaired or upgraded, reducing waste and environmental impact. This aligns with sustainability principles and has positive societal impacts, such as reduced energy consumption and lower greenhouse gas emissions. It also encourages manufacturers to design lighting products that are easy to maintain and recycle, which can lead to more sustainable and user-friendly lighting solutions.

- Smart Buildings/Digitalization: With the advent of smart buildings, lighting systems can be controlled and monitored digitally, providing valuable data about their usage and performance. This can enable better energy management, help detect issues early, and allow for more personalized lighting settings, enhancing the human-centric approach. Furthermore, digitalization can enable the integration of lighting with other systems, such as heating or shading, for more holistic and efficient building management.

- Human-centric/Integrative Factors: Regulations that emphasize human-centric and integrative factors in lighting design can lead to better quality lighting environments. For example, regulations might stipulate the use of adjustable lighting that can mimic the natural progression of daylight, supporting the human circadian rhythm. They might also encourage the use of natural light and the creation of different lighting zones to cater to different tasks and preferences. These factors can significantly enhance the comfort, well-being, and productivity of users, which is the ultimate goal of human-centric lighting.

4. Framework Development for Effective Lighting Asset Management

4.1. Overall Lighting Asset Management Purpose and Objectives

- Clearly define the overall purpose and objectives of lighting asset management: This involves establishing specific targets and outcomes that the lighting asset management process aims to achieve. The goals should be aligned with the organization’s overall objectives.

- Incorporate human-centric and integrative requirements into the overall purpose and objectives: This aspect highlights the importance of considering human factors, user experience, and integrative design principles when setting lighting asset management goals. Human-centric and integrative requirements emphasize the health and well-being of the people who interact with the lighting systems. Examples of human-centric and integrative requirements may include the following:

- Providing lighting conditions that promote comfort and productivity.

- Considering the visual needs and preferences of different user groups.

- Designing lighting systems that contribute to the overall aesthetics and ambiance of the space.

- Incorporating controls and automation features that enhance user convenience and flexibility.

- Ensuring lighting systems support human circadian rhythms and promote well-being.

- Integrating lighting with other building systems to create a cohesive and harmonious environment.

4.2. Lighting Asset Management System

- Establish the necessary standards, rules, and regulations for lighting asset management:

- This involves defining a set of guidelines and criteria that govern the management of lighting assets in public libraries.

- Standards may include technical specifications, recommended practices, and performance criteria specific to lighting systems in library environments.

- Rules and regulations may encompass safety guidelines, electrical codes, and other compliance requirements relevant to lighting installations.

- Ensure compliance with industry best practices and relevant regulations:

- It is crucial to align lighting asset management practices with established industry best practices and regulations.

- This may involve considering standards and guidelines set by organizations such as the Illuminating Engineering Society (IES), Building Owners and Managers Association (BOMA), or relevant local, regional, and national regulatory bodies.

- Compliance with these standards helps ensure that lighting assets are managed efficiently, safely, and in line with recognized benchmarks.

- Safety: Lighting systems must adhere to safety standards to minimize the risk of electrical hazards and ensure the well-being of library patrons and staff.

- Performance: Defined standards enable the consistent performance of lighting systems, ensuring optimal illumination levels, color rendering, and energy efficiency.

- Consistency: Having established rules and regulations promotes consistency in lighting asset management practices across different library branches or locations.

- Compliance: Adhering to relevant regulations and codes helps libraries meet legal requirements and ensures they are operating within the prescribed guidelines.

- Accountability: Having a framework of standards and rules provides a basis for accountability in the management and maintenance of lighting assets.

4.3. Plan

- Set up lighting asset management goals:

- Identify and prioritize integrative/human-centric requirements for lighting assets specific to public libraries.

- This involves understanding the unique needs and preferences of library users and aligning the lighting asset management goals accordingly.

- Goals may include providing comfortable lighting for reading areas, optimizing energy efficiency, and enhancing the visual appeal of the library space. Examples of lighting asset management goals may include the following:

- ○

- Enhancing the reliability and performance of lighting assets.

- ○

- Minimizing downtime and disruptions caused by lighting asset failures.

- ○

- Optimizing maintenance efforts and resource allocation.

- ○

- Ensuring the safety and well-being of users in the lit environment.

- ○

- Improving energy efficiency and sustainability of lighting systems.

- ○

- Enhancing the visual comfort and quality of lighting for occupants.

- Set up a database for lighting assets:

- Establish a comprehensive database to store information related to lighting assets in public libraries.

- Store asset information such as specifications, maintenance history, and condition data.

- Classify lighting assets based on various criteria, such as location, type, or function.

- Perform criticality analysis to prioritize maintenance efforts based on the assets’ importance and impact on library operations.

- Develop a maintenance plan:

- Define the maintenance strategy for lighting assets to ensure their optimal performance and longevity.

- Create a detailed maintenance plan that outlines schedules, tasks, and procedures for maintaining lighting assets.

- Allocate necessary maintenance resources, such as personnel, tools, and materials, to execute the maintenance plan effectively.

- Establish lighting asset management processes:

- Develop maintenance processes that outline step-by-step procedures for executing maintenance tasks on lighting assets.

- Implement fault management processes to address lighting asset failures promptly and effectively.

- Establish spare-part management processes to ensure timely replacement of faulty components and minimize downtime.

- Develop a lighting data/information management plan:

- Determine the data requirements for effective lighting asset management.

- Establish protocols for data collection, storage, and analysis, ensuring data integrity and accessibility.

- Utilize data to monitor asset performance, identify maintenance needs, and make informed decisions.

- Create a lighting sustainable development plan:

- Incorporate sustainability considerations into lighting asset management practices for public libraries.

- Explore energy-efficient lighting solutions, such as LED technology or daylight harvesting, to reduce environmental impact.

- Consider sustainable procurement practices and disposal/recycling options for lighting assets.

4.4. Do

- Execute the lighting asset management plan:

- Collect and verify data on lighting assets:

- ○

- Regularly gather relevant data, including asset specifications, maintenance records, and condition data.

- ○

- Verify the accuracy and completeness of the collected data to ensure their reliability for decision making.

- Execute planned work orders for scheduled maintenance:

- ○

- Implement the maintenance plan by performing scheduled maintenance tasks according to the predefined schedule.

- ○

- Adhere to the established procedures and guidelines for carrying out maintenance activities.

- Address unplanned work orders and emergencies promptly:

- ○

- Respond to unplanned maintenance requests and emergencies related to lighting assets.

- ○

- Prioritize and address these work orders promptly to minimize disruptions and ensure the safety of library users.

- Manage fault occurrences and perform necessary repairs:

- ○

- Detect and diagnose faults in lighting assets promptly.

- ○

- Perform repairs or replacement of faulty components to restore the proper functioning of lighting systems.

- Provide feedback on completed work orders and condition monitoring:

- ○

- Document the completion of work orders, including details of tasks performed and any observations made.

- ○

- Conduct condition monitoring to assess the health and performance of lighting assets and record the findings.

- Execute lighting asset management processes:

- Follow established maintenance, fault management, and spare-part management processes:

- ○

- Adhere to the predefined processes and procedures for carrying out maintenance tasks, managing faults, and handling spare parts.

- ○

- Ensure that the processes are consistently followed to maintain operational efficiency and standardize practices.

- Ensure adherence to relevant procedures and guidelines:

- ○

- Comply with applicable regulations, industry standards, and internal guidelines related to lighting asset management.

- ○

- Adhere to safety protocols to minimize risks associated with maintenance activities.

4.5. Study

- Define key performance indicators (KPIs) for lighting asset management:

- Establish a set of KPIs that reflect the critical aspects of lighting asset management in public libraries. In alignment with the goals, it is essential to incorporate human-centric and integrative requirements into the KPIs.

- KPIs may include the following:

- ○

- Asset availability and reliability: Measure the percentage of time that lighting assets are available and operational.

- ○

- Data quality: Assess the accuracy, completeness, and reliability of data collected for lighting assets.

- ○

- Lighting asset performance: Evaluate the performance of lighting assets, such as luminance levels, color rendering, and maintenance history.

- ○

- Work execution and improvement: Monitor the execution of planned work orders, track improvement initiatives, and measure the effectiveness of maintenance efforts.

- ○

- Gap analysis: Identify discrepancies between planned maintenance tasks and their actual execution to identify areas for improvement.

- ○

- Maintenance resource utilization: Evaluate the effectiveness and efficiency of maintenance resources, including personnel, tools, and materials.

- ○

- Energy efficiency of lighting assets: Measure the energy consumption of lighting assets and assess their efficiency.

- ○

- Effectiveness of support systems: Evaluate the performance and impact of support systems, such as lighting controls or automation.

- Analyze KPI results to gain insights into asset performance and identify areas for improvement:

- Regularly analyze the data collected from the defined KPIs to assess the performance of lighting assets.

- Identify trends, patterns, and areas that require attention or improvement.

- Use the insights gained from the analysis to make informed decisions regarding maintenance strategies, resource allocation, and process improvements.

- Adjust and refine lighting asset management practices based on the findings to optimize performance and enhance user experience.

4.6. Act

- Conduct benchmarking and customer needs analysis:

- Engage with library users, work staff, and asset managers to understand their requirements and gather feedback on lighting asset management.

- Evaluate the effectiveness of the existing asset management and information systems.

- Consider energy efficiency and sustainability aspects to align with environmental goals and regulations.

- Perform integrated fault analysis:

- Analyze faults in lighting assets holistically to identify underlying systemic issues.

- Look beyond individual failures and consider patterns or common root causes.

- Develop strategies to address recurring or critical faults and prevent future occurrences.

- Review and optimize the lighting asset management strategy:

- Regularly review the effectiveness of the current asset management strategy in meeting the defined goals and objectives.

- Identify areas for optimization and implement necessary changes to improve efficiency and performance.

- Consider advancements in technology, industry best practices, and user feedback when refining the strategy.

- Optimize asset management resources:

- Provide training and skill development opportunities for maintenance staff to enhance their capabilities and expertise.

- Optimize spare inventory management to minimize costs and ensure timely availability of necessary components.

- Consider business process reengineering (BPR) to enhance operational efficiency:

- Evaluate existing processes and identify opportunities for streamlining and optimizing workflows.

- Redesign processes to eliminate bottlenecks, reduce redundancies, and improve overall efficiency.

- Incorporate new design and renewal strategies for lighting assets:

- Stay updated with advancements in lighting technology and design trends.

- Integrate new lighting solutions or upgrade existing systems to enhance performance, energy efficiency, and user experience.

- Optimize the KPI system to effectively measure and track performance:

- Continuously evaluate and refine the KPIs used to measure the performance of lighting asset management.

- Ensure that the KPIs align with the defined goals and provide meaningful insights for decision making.

4.7. Digitalization and Visualization Support Systems and Tools

- Leverage digital technologies and tools to enhance lighting asset management:

- Embrace digitalization and utilize technology solutions to streamline and improve lighting asset management processes.

- Adopt digital platforms, such as computerized maintenance management systems (CMMS), to centralize data, automate workflows, and facilitate efficient asset management.

- Utilize visualization techniques for data analysis and decision making:

- Implement visualization tools and techniques to analyze and present lighting asset data in a visual and intuitive format.

- Utilize dashboards, graphs, and charts to visualize trends, performance metrics, and maintenance information.

- This enables easier comprehension of complex data, facilitates data-driven decision making, and enhances communication among stakeholders.

- Implement relevant software solutions and platforms for asset management:

- Identify and implement software solutions specifically designed for lighting asset management.

- Utilize software tools that offer features such as asset tracking, maintenance scheduling, data management, and performance analysis.

- Choose platforms that align with the integrative/human-centric approach and support the specific needs of public libraries.

- Improved efficiency: Digital technologies automate manual processes, reduce paperwork, and streamline workflows, resulting in increased efficiency and productivity in managing lighting assets.

- Enhanced data analysis: Visualization techniques enable easier interpretation and analysis of lighting asset data, facilitating better insights, trend identification, and informed decision making.

- Centralized information: Digital platforms centralize data, ensuring easy access to asset information, maintenance records, and condition data, enhancing collaboration and information sharing among stakeholders.

- Timely maintenance: Software solutions help schedule and track maintenance tasks, ensuring timely execution and reducing downtime or disruptions in library services.

- Cost optimization: Digital tools enable effective resource allocation, including optimizing maintenance staff schedules, spare-part-inventory management, and energy consumption analysis, resulting in cost savings.

- Improved communication: Visualization tools facilitate the clear and concise communication of lighting asset performance, maintenance needs, and progress reports to stakeholders, enhancing collaboration and transparency.

5. Maturity Assessment Model with an Accompanying Matrix

- Initial: This is the starting point for the use of a new or undocumented repeat process.

- Repeatable: The process is at least repeatable, possibly with consistent results. Process discipline is unlikely to be rigorous, but where it exists, it may help ensure that existing processes are maintained during times of stress.

- Defined: The process is defined/confirmed as a standard business process and decomposed to levels 0, 1, and 2 (the latter being Work Instructions).

- Managed: The process is quantitatively managed in accordance with agreed-upon metrics.

- Optimizing: Process management includes deliberate process optimization/improvement.

| Stage I. Initial | Stage II. Repeatable | Stage III. Defined | Stage IV. Managed | Stage V. Optimizing | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strategy | Overall | No formal strategy: decisions are ad hoc | Some consistency in decisions | Formal asset management | Strategy is implemented and monitored | Strategy is continuously refined |

| ISO55000 | No principles or guidelines outlined in ISO 55000 | Early understanding of ISO 55000 | Aligned with ISO 55000 | Regular reviews against ISO 55000 | ||

| Maintenance | Corrective | Preventive | Predictive | Proactive | ||

| Process | Defined | No | Repeatable | Yes | ||

| Documented | No | Yes | ||||

| Standardized | No | Yes | ||||

| Monitored | No | Begin to monitor process performance | Regular monitoring and reporting of process performance | |||

| Controlled | No | Processes are consistently followed and controlled | ||||

| Optimization | No | Proactive process optimization based on performance data; best practices are benchmarked and implemented | ||||

| Data | Collected | Data collection is inconsistent or non-existent | Some data are collected | Data collection is part of the standard procedure | ||

| Analyzed | No | Analysis is minimal or absent | Analysis is part of the standard procedure | Comprehensive data analysis supports decision making; begin to use predictive analytics | Advanced analytics and AI are used for predictive and prescriptive insights | |

| Decision Support | Decisions are based on individual experience or intuition | Some use of data in decision making | Defined criteria for decision making; regular use of data analysis | Decision making is data-driven; use of analytics for predictive insights | Decision making is proactive and strategic, supported by predictive and prescriptive analytics | |

| Continuous Improvement | No formal improvement initiatives | Early efforts to improve efficiency and performance | Improvement objectives are defined and linked to strategy | Performance is regularly reviewed, and improvements are made | Continual, proactive improvement across cost, energy efficiency, and human-centric considerations | |

| Digitalization | Little to no use of digital tools | Early adoption of digital tools | Digital tools are part of standard procedures | Digital tools are fully integrated | Advanced digital technologies (e.g., IoT, AI) are adopted | |

| Visualization | Little to no use of visualization | Minimal use of visualization | Begin to use visualization for data analysis | Regular use of visualization for decision making | Visualization is used for advanced analytics and strategic decision making | |

5.1. Stage I: Initial

5.2. Stage II: Repeatable

5.3. Stage III: Defined

- Level 0: An overarching process such as “Maintain Lighting System”, which encompasses all activities related to maintaining the lighting assets in the library.

- Level 1: This might break down the Level 0 process into several major subprocesses, such as “Perform Regular Inspections”, “Replace Burnt-out Bulbs”, “Clean Lighting Fixtures”, etc.

- Level 2: At this level, each Level 1 process is further decomposed into specific work instructions. For instance, “Perform Regular Inspections” might include detailed steps on how to inspect different types of light fixtures, what to look for during inspections, how often inspections should be performed, etc.

5.4. Stage IV: Managed

5.5. Stage V: Optimizing

6. Sustainable Development to Systematic and Sustainable Advancements

6.1. The Mandate of Lighting Asset Manager

- Designing integrative lighting: The asset manager may work with lighting designers to develop an efficient lighting plan that meets the needs of the library and its patrons.

- Conducting a lighting audit: An asset manager may conduct a lighting audit to assess the current lighting system in the library, identify any areas for improvement, and determine the energy consumption of the lighting system.

- Developing a lighting management plan: Based on the findings of the lighting audit, the asset manager may develop a lighting management plan that includes strategies for reducing energy consumption, optimizing lighting levels, and minimizing maintenance costs.

- Ensuring energy efficiency and reducing the environmental impact of the lighting system: The asset manager should ensure that the library’s lighting system is as energy efficient as possible. This can be achieved using energy-efficient lighting fixtures, controls, and other technologies.

- Ensuring maintenance implementation: The asset manager should ensure that the library’s lighting system is maintained in a cost-effective manner. This can include regular inspections, preventative maintenance (cleaning, replacement of light bulbs and other components, etc.), and predictive maintenance (repairs as needed).

- Implementing lighting upgrades: The asset manager may oversee the implementation of lighting upgrades, such as installing energy-efficient lighting fixtures (incl., LED), upgrading control systems (incl. implementing occupancy sensors to turn off lights when areas are unoccupied), and incorporating daylight harvesting systems to maximize natural light.

- Budgeting: The asset manager should work with the library’s budget to ensure that adequate funds are available for lighting upgrades and maintenance.

- Monitoring and analyzing lighting data: The asset manager may regularly monitor and analyze lighting data to ensure that the lighting system is performing as intended and functioning effectively and efficiently, as well as identify any areas for further improvement.

- Training and educating staff: The asset manager may train and educate library staff on the proper use of the lighting system and best practices for lighting management.

6.2. Paving the Way to ISO 55000

- Establishing an asset management policy and ensuring that lighting assets are aligned with the library’s strategic objectives: ISO 55000 requires the development of an asset management policy that defines the objectives, scope, and responsibilities for managing assets, including lighting assets in public libraries. By applying ISO 55000, the library can ensure that its lighting assets are aligned with its broader strategic objectives. This can help ensure that the lighting assets are designed and managed to support the library’s goals, such as improving the user experience, reducing energy consumption, or increasing safety.

- Conducting a risk assessment and providing guidance on risk management: A risk assessment helps identify potential risks and opportunities associated with lighting assets in public libraries. This includes identifying the risks of lighting failures, potential hazards, and the costs associated with maintenance and replacement. ISO 55000 provides guidance on how to identify and manage risks associated with asset management. In the case of lighting assets, this can help ensure that any safety risks associated with lighting (such as the risk of fire or electrical shock) are identified and mitigated.

- Developing an asset management plan: Based on the risk assessment, an asset management plan is developed that outlines the strategies and actions required to manage lighting assets in public libraries. This includes maintenance schedules, repair and replacement plans, and investment strategies.

- Implementing asset management activities and promoting cost-effective maintenance: The asset management plan is implemented by carrying out maintenance activities, monitoring asset performance, and continually reviewing and improving the management of lighting assets in public libraries. By following ISO 55000 guidelines for maintenance, the library can ensure that lighting assets are maintained in a cost-effective manner. This can include regular inspections, preventative maintenance, and predictive maintenance (repairs as needed).

- Monitoring and review: ISO 55000 requires regular monitoring and review of asset management activities to ensure they remain effective and efficient. This includes reviewing asset performance, assessing the effectiveness of asset management strategies, and identifying opportunities for improvement.

- Ensuring compliance with regulations and standards: ISO 55000 provides guidance on complying with relevant regulations and standards. In the case of lighting assets, this can include ensuring compliance with building codes, electrical safety regulations, and environmental standards.

- Overall, by applying the principles, requirements, and guidelines of ISO 55000 to human-centric and integrative lighting asset management in public libraries, the library can ensure that its lighting assets are managed in a systematic and sustainable way and that they support the library’s broader goals and objectives.

6.3. Maturity Model Aligned with ISO 55000

- Initial: At this stage, organizations have an inconsistent or ad hoc approach to managing their lighting assets. There may be no standardized procedures, and any existing practices rely heavily on the individual knowledge and experience of personnel. The organization has not yet implemented the principles or guidelines outlined in ISO 55000.

- Repeatable: Organizations at this stage have established some repeatable procedures for managing lighting assets, though these may not be formally documented or consistently applied. The organization begins to introduce the concepts of ISO 55000, such as recognizing the value of their lighting assets and the importance of managing them effectively.

- Defined: The organization has a clear, documented process for managing lighting assets in alignment with ISO 55000. This includes setting asset management objectives, implementing an asset management plan, and establishing roles and responsibilities for asset management activities. The organization ensures that these processes are followed and understood by all relevant staff members.

- Managed: At this stage, the organization not only has defined processes but also uses key performance indicators and other metrics to monitor and manage the performance of its lighting assets. This is in line with ISO 55000’s emphasis on performance assessment and continual improvement.

- Optimizing: The highest level of maturity. The organization is not just managing its lighting assets but also proactively seeking ways to improve its asset management system. This could involve benchmarking against industry best practices, using predictive analytics to optimize maintenance activities, or implementing advanced technologies like IoT for better asset monitoring and control. The organization continually reviews and adjusts its asset management system based on performance data, feedback, and changing business or regulatory requirements. This reflects ISO 55000’s principle of continual improvement.

6.4. Maturity Assessment Matrix

- Performance Evaluation: It provides a structured framework for evaluating current performance. By comparing actual practices against the criteria in each stage of the matrix, an organization can understand its current maturity level.

- Identifying Areas for Improvement: The matrix helps highlight areas that need improvement. If an organization finds its practices align more with the “Initial” or “Repeatable” stages, it indicates that there are opportunities to enhance its processes and procedures.

- Guiding Progress: The matrix not only reveals where an organization currently stands but also points to what it can aim for. The detailed criteria provide a roadmap for advancing to higher maturity levels.

- Facilitating Communication and Understanding: The matrix can serve as a valuable communication tool. It helps everyone in the organization understand what good performance looks like and what steps need to be taken to achieve it.

- Supporting Strategic Decision Making: By providing a clear picture of current performance and potential improvements, the matrix supports more informed and strategic decision making.

- Continual Improvement: The nature of the matrix supports the philosophy of continual improvement. Organizations are encouraged to progress through the stages over time, constantly enhancing their processes and capabilities.

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Global Lighting Association. Strategic Roadmap of the Global Lighting Industry. 2015. Available online: https://globallightingassociation.org/images/files/GLA_Roadmap_usl_web.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- Zhu, F.; Lin, Y.; Huang, W.; Lu, T.; Liu, Z.; Ji, X.; Kang, A.; Wang, H.; Chen, Z.; Wu, T. Multi-primary human-centric lighting based on the optical power ratio and the CCT super-smooth switching algorithms. Build. Environ. 2023, 228, 109880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO/CIE. Light and Lighting—Integrative Lighting—Non-Visual Effects; International Commission on Illumination: Vienna, Austria, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, L.; Xue, P.; Zhang, L.; Wang, J.; Shi, J.; Liang, Q.; Cao, X.; Xu, N.; Liao, J. Visual and non-visual effects of integrated lighting based on spectral information. Build. Environ. 2023, 242, 110617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madias, E.-N.D.; Christodoulou, K.; Androvitsaneas, V.P.; Skalkou, A.; Sotiropoulou, S.; Zervas, E.; Doulos, L.T. Τhe effect of artificial lighting on both biophilic and human-centric design. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 76, 107293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 55000; Asset Management—Overview, Principles and Terminology. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- ISO 55000; Asset Management—Management Systems—Requirements. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- ISO 55000; Asset Management—Management Systems—Guidelines for the Application of ISO 55001. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- European Commission. Lighting—Energy Labelling and Ecodesign Requirements Apply to This Product. 2019. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/energy-climate-change-environment/standards-tools-and-labels/products-labelling-rules-and-requirements/energy-label-and-ecodesign/energy-efficient-products/lighting_en (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- Veitch, J.A. Achieving Good Lighting Quality with integrative lighting: Opportunities and challenges. In Proceedings of the 11th Biennial Joint meeting, Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 3–4 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, J. The Complicated Role of the Modern Public Library. The National Endowment for the Humanities. 14 October 2023. Available online: https://www.neh.gov/article/complicated-role-modern-public-library (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- Hilliard, W. Stockholm’s Public Libraries: Essential Public Spaces; KTH Royal Institute of Technology: Stockholm, Sweden, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- LightingEurope. Strategic Roadmap 2025 of the European Lighting Industry. 2016. Available online: https://www.lightingeurope.org/images/publications/ar/LE_AR2016.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- Lighting For People. What Is Human Centric Lighting? 2015. Available online: http://lightingforpeople.eu/human-centric-lighting/ (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- Metcalf, K.D. Library Lighting; The Association of Research Libraries: Washington, DC, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Mostafavi, A.; Cruz-Garza, J.G.; Kalantari, S. Enhancing lighting design through the investigation of illuminance and correlated color Temperature’s effects on brain activity: An EEG-VR approach. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 75, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wymelenberg, K.V.D.; Inanici, M. A Critical Investigation of Common Lighting Design Metrics for Predicting Human Visual Comfort in Offices with Daylight. LEUKOS J. Illum. Eng. 2014, 10, 145–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, B.W. Sustainability as a Driving Force in Contemporary Library Design. Libr. Trends 2011, 60, 190–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malman, D. Lighting for Libraries. Architectural Lighting Design, and Provided through the Libris Design Project, Supported by the U.S. Institute of Museum and Library Services under the Provisions of the Library Services and Technology Act, Administered in California by the State Library. 2005. Available online: https://ilovelibrariesblog.wordpress.com/2017/06/21/lighting-for-libraries/ (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- Kilic, D.K.; Hasirci, D. Daylighting Concepts for University Libraries and Their Influences on Users’ Satisfaction. J. Acad. Librariansh. 2011, 37, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhari, A.A.; Alibaba, H.Z. Analysis of Daylighting Quality in Institutional Libraries. Int. J. Electr. Electron. Res. 2019, 7, 6–20. [Google Scholar]

- Bright Ideas for Public Libraries: Efficient Lighting for a Sustainable Future. Energy 5. 30 September 2023. Available online: https://energy5.com/bright-ideas-for-public-libraries-efficient-lighting-for-a-sustainable-future (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- IEC 60050-845; International Electrotechnical Vocabulary (IEV)—Part 845: Lighting. IEC: London, UK, 2020.

- LED Life for General Lighting: Definition of Life. ASSIST. 2005. Available online: https://www.lrc.rpi.edu/programs/solidstate/assist/pdf/ASSIST-LEDLife-revised2007.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- Anugrah, M.P.; Munawaroh, A.S. Assessment of Natural Lighting and Visual Comfort of Library. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Engineering and Technology Development, Bandar, Iran, 25–28 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kime, B.A. Comparative Analysis of Day lighting and Artificial Lighting in Library Building; Analyzing the Energy Usage of the Library. Int. J. Adv. Res. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2018, 5, 7665–7680. [Google Scholar]

- Perera, N.; Swaris, N. Good Reading Light: Visual Comfort Perception and Daylight Integration in Library Spaces. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference of Faculty of Architecture Research Unit (FARU), Colombo, Sri Lanka, 8 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- The 17 Sustainable Development Goals. United Nations. 2015. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/about (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- How Lighting Contributes to the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs); LightingEurope: Brussels, Belgium, 2022.

| Aligned SDGs | Direct Alignment | Indirect Alignment |

|---|---|---|

| SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being | Proper visual environment for reading, studying, and computer work directly contributes to the well-being of library users, providing a conducive environment for reading and studying. | Circadian lighting design can indirectly promote psychological health of library users by supporting healthy sleep patterns and promoting alertness. |

| SDG 4: Quality Education | For after-school students, library usually serves as a self-learning center. Proper lighting is essential for creating an environment that supports reading and learning, especially in the afternoon. | In the library, the same environment needs to support flexible and adaptable activity purposes. Therefore, lighting design that accommodates various learning styles and activities indirectly contributes to the quality of education in public libraries. |

| SDG 7: Affordable and Clean Energy | Energy-efficient lighting systems and smart lighting control strategies in public libraries contribute directly to the goal of clean and affordable energy. | With the development of lighting technology, the use of solar tube (solar reflection through ductworks) is an indirect way to power lighting systems with solar energy, which indirectly supports the goal of clean energy. |

| SDG 9: Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure | Moving from energy efficiency to lighting for health and well-being is a big shift that aligns with innovations that add extra value to society. | Exploring digitalization and intelligent lighting systems presents opportunities for innovative implications, contributing to industry and infrastructure development. |

| SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities | Implementing sustainable lighting design in public libraries contributes directly to the goal of sustainable cities and communities. | Incorporating recycled materials or circular lighting design in lighting fixtures supports sustainability and aligns with the goal of sustainable communities. |

| SDG 12: Responsible Consumption and Production | Promoting energy-efficient lighting technologies aligns with responsible consumption and production. | |

| SDG 13: Climate Action | Implementing sustainable lighting design can directly contribute to reducing energy consumption and carbon emissions. | The use of renewable energy sources and energy-efficient lighting control strategies indirectly supports climate action. |

| SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals | Digitalized collaboration between stakeholders to achieve sustainable lighting solutions aligns with the goal of partnerships for achieving the SDGs. | |

| Identified Contexts (Factors) | Class 1 | |

|---|---|---|

| Level I | Level II | |

| External Environmental Factors | Geographic Location, Seasonal Changes, Circadian Rhythm, Occlusion Effects | Sunlight Intensity |

| Temperature Variations | ||

| Humidity | ||

| Air Quality | ||

| Interior Design Factors | Building | Building Material Characteristics |

| Daylight Interaction | ||

| Furniture (Excluding Bookshelf) | Furniture Position | |

| Furniture Characteristics | ||

| Bookshelf | Bookshelf Position | |

| Bookshelf Characteristics | ||

| Fixed Lighting | Lighting Position | |

| Lighting Characteristics | ||

| Human–Lighting Interactivity | ||

| Adjustable Lighting | Lighting Characteristics | |

| Human–Lighting Interactivity | ||

| User Factors | Asset Manager | Guidance to Operators and Customers |

| Operator | Operators’ Behavior on Lighting | |

| Customer | Age | |

| Gender | ||

| Height | ||

| Activities | ||

| Customer’s Behavior | ||

| Cost Factors | Energy Consumption | |

| Purchase | ||

| Installation | ||

| Operation | ||

| Maintenance (Inspection, Cleaning, Replacement, etc.) | ||

| Regulation Factors | Asset Management Strategies/Regulations | |

| Circular Economy/Sustainability/Society Impacts | ||

| Smart Buildings/Digitalization | ||

| Human-centric/Integrative Factors | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lin, J.; Shen, J.; Silfvenius, C. Human-Centric and Integrative Lighting Asset Management in Public Libraries: Insights and Innovations on Its Strategy and Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2096. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16052096

Lin J, Shen J, Silfvenius C. Human-Centric and Integrative Lighting Asset Management in Public Libraries: Insights and Innovations on Its Strategy and Sustainable Development. Sustainability. 2024; 16(5):2096. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16052096

Chicago/Turabian StyleLin, Jing, Jingchun Shen, and Christofer Silfvenius. 2024. "Human-Centric and Integrative Lighting Asset Management in Public Libraries: Insights and Innovations on Its Strategy and Sustainable Development" Sustainability 16, no. 5: 2096. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16052096

APA StyleLin, J., Shen, J., & Silfvenius, C. (2024). Human-Centric and Integrative Lighting Asset Management in Public Libraries: Insights and Innovations on Its Strategy and Sustainable Development. Sustainability, 16(5), 2096. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16052096