1. Introduction

Since the initiation of economic reforms and opening up, China has developed rapidly, with an annual growth rate of 9.7% of GDP, and became the second largest economy in the world in 2010, gaining recognition as the “China growth miracle” and attracting widespread global attention. However, due to substantial inherent disparities between China and other developed nations across various critical domains, such as technological innovation and talent cultivation, the extraordinary pace of economic growth seems to lack a fully justifiable and rational explanation. Scholars have extensively debated this issue, and Li’an Zhou’s theory of the “political promotion tournament” provides robust theoretical support for analyzing this phenomenon [

1,

2]. According to this theory, within China’s centralized political system, the central government primarily assesses and promotes local officials based on economic growth, thereby motivating local officials to vigorously develop the economy in pursuit of political advancements.

However, this singular dimension of the performance assessment mechanism gradually reveals its inherent flaws and issues. Under the “strong incentives” of the economic performance promotion and assessment system, some local governments, to pursue GDP or fiscal revenue, prioritize economic development over environmental protection. They emphasize a “resource-intensive” development model that focuses on attracting investment, infrastructure construction, and natural resource exploitation—practices involving high investments, energy consumption, and short-term economic benefits [

3,

4,

5]. Although such practices have led to significant economic achievements, they have also resulted in problems of environmental pollution, resource waste, and suboptimal non-economic public welfare. Among these challenges, air pollution poses a particularly severe threat, as acid rain and dust pollution have seriously compromised the health of Chinese residents. According to a World Bank report titled “Cost of Pollution in China” published in 2007, only 1% of urban residents in China live in accordance with the World Health Organization’s standard of an average daily concentration of inhalable particles below 40 micrograms, while 58% of urban residents live in air with concentrations exceeding 100 micrograms. Simultaneously, the economic losses caused by environmental pollution nationwide in 2004 amounted to USD 61.84 billion, accounting for 3.05% of that year’s GDP. Severe air pollution acts as a warning sign from nature against the extensive growth model. To improve the environment, it is imperative to address the thorough governance of emission pollutants such as sulfur dioxide. The significance no longer solely lies in environmental governance itself, but also in achieving a transformation of China’s economic development towards sustainable and high-quality growth.

In the early process of pollution control, the Chinese government implemented a series of atmospheric governance measures, including the implementation of the “Law on the Prevention and Control of Atmospheric Pollution” and the establishment of “Two Control Zones” (acid rain control zone and sulfur dioxide pollution control zone). The subsequent “10th Five-Year Plan” (The five-year plans in China serve as the government’s strategic blueprints for economic and social development, reviewed and revised every five years. The Tenth Five-Year Plan (2001–2005) prioritized economic restructuring and societal advancement, while the Eleventh Five-Year Plan (2006–2010) emphasized the transition in the economic growth approach and regional coordinated development. These plans collectively propelled the healthy growth of the Chinese economy.) set a target of a 10% reduction in sulfur dioxide emissions and implemented total pollutant control, marking the beginning of large-scale pollution control efforts. However, the governance effectiveness of such environmental regulation policies appears to be suboptimal. The sulfur dioxide emissions within the “two control zones” in 2005 were far from the 20% reduction target. In fact, during the “10th Five-Year Plan” period, there was an increase in sulfur dioxide emissions, with a 27.5% rise in emissions from 2000 to 2005. This severe air pollution situation persisted until the “11th Five-Year Plan” period when it was finally broken.

In response to air pollution challenges and to guide local governments towards greater focus on sustainable development, the central government made significant adjustments to the official assessment system. At the end of 2005, the central government took the reduction in SO

2 emissions as the main performance evaluation standard of the mayor and party secretary of the county, and, for the first time, included the emission quota into the performance evaluation system, which brought great changes to the lives of these local bureaucrats. Through the transformation of the development concept, system adjustment, and the adjustment of local assessment indicators, the central government has expanded the opportunities and channels for local officials to achieve promotion, which means that the “strong incentive” of single economic performance appraisal is gradually transformed into “weak incentive” multi-task assessment, which highlights environmental governance and public welfare. And the expectations and actions of local officials have also changed [

2]. Under the multi-tasking promotion assessment system, the emission of sulfur dioxide pollution has been finally controlled and decreased each year.

From the perspective of principal–agent theory, a principal–agent relationship is effectively formed between the central government and local governments. Under a multi-target performance evaluation system, local officials are driven by these evaluation targets to take actions [

6,

7,

8], often resulting in them seeking a delicate balance among multiple objectives. When the promotion incentive mechanism changes, local governments need to balance the dual tasks of environmental protection and local economic growth. Existing studies on the measurement of local economic performance mainly examine from the perspective of regional gross domestic product (GDP). Research by Chen et al. found that when environmental regulations are included in the assessment of local officials, officials may sacrifice a portion of local GDP growth to meet the environmental regulations [

9]. Although there is a positive correlation between fiscal revenue and GDP—typically, GDP growth means an increase in fiscal revenue—the relationship between the two is not a simple linear one. Fiscal revenue is the foundation for the operation of local governments and the provision of public services. It directly reflects the benefits of local governments in economic activities, serving as an important indicator for evaluating the governance capacity and effectiveness of local governments. It directly determines the quality and quantity of public services and infrastructure that the government can provide. Compared to GDP or other economic aggregate indicators, fiscal revenue more concretely reflects the role and influence of the government in economic life. Therefore, in-depth exploration of the assessment of environmental regulations and local fiscal revenue becomes particularly important.

On this basis, with the samples of 207 prefecture-level cities in China from 2002 to 2010 and taking the historical event of China’s initial adjustment of the target assessment system for local officials—the central government incorporated the SO2 emission quota into the performance evaluation system of local officials in 2005—as a quasi-natural experiment, this paper utilizes the difference-in-differences (DID) method to examine the impact of environmental regulation assessment pressure on local fiscal revenue and tries to answer the following questions: Can environmental regulation pressure generate momentum for fiscal growth? Will local governments sacrifice some financial growth in order to meet the assessment targets of environmental regulation? Is it win–win or win–lose between the two different targets? The findings indicate that local environmental regulation pressure indeed stimulates fiscal growth, and for each 0.01 increase in the targets of pollution emission reduction, local fiscal revenue increases by 0.204%.

It is worth noting the following question: why choose to study China? China has introduced environmental regulations into the evaluation criteria for local officials, providing a unique research background. This policy adjustment is rare on a global scale, positioning China as an excellent setting to investigate the effects of such regulations. Analyzing the impact of this policy adjustment on local government behavior and financial outcomes can offer valuable insights and references for other nations. Secondly, as a representative of a transitioning economy, for China, as the world’s largest developing country and transitioning economy, the changes in government governance structure and incentive mechanisms are of significant importance in understanding government behavior during economic transition. Studying the behavior strategies of Chinese local governments under the pressure of environmental regulation assessment can offer valuable insights for other transitioning economies.

Compared with the existing research, the main innovation and contribution of this study are as follows: Firstly, the measurement of the environmental regulation of this policy in the existing literature mostly relies on dummy variables [

9,

10], which fail to accurately reflect the intensity of environmental regulation. For the first time, this study systematically collected and organized the emission control target indicators for major pollutants at the prefectural level during the “11th Five-Year Plan” period. These indicators were utilized to measure the intensity of environmental regulation while simultaneously constructing a continuous difference-in-differences (DID) model to investigate the impact of environmental regulation. It is worth noting that, due to the limited availability of target indicator data, existing studies have mainly been conducted at the provincial level or have used formulas to decompose provincial-level data into the prefecture level for analysis [

11]. However, the data obtained in this way deviate significantly from the data indicated in the actual policy documents of local governments. To address this gap in the existing literature, this study manually collected the indicator data, which not only effectively resolves the biased estimation based on city-level research in the existing literature but also enables a comprehensive examination of the impact of multi-tasking assessment on fiscal development from an urban perspective.

Secondly, the purpose of this study is to reveal the changes in local governments’ behaviors when the promotion evaluation system of officials shifts from pursuing a single-dimensional economic growth to emphasizing the multi-dimensional development of ecological environment and economy. A comprehensive review of the literature revealed that existing studies mainly examined the impact of this policy from perspectives such as the reduction of relevant pollutants [

12,

13], foreign direct investment (FDI) [

14], regional GDP [

9], total industrial output value [

15], enterprise exports [

16], fixed asset investment [

17], the development of the banking industry [

18], and local tax rates [

10]. Unlike previous research, this study expands its scope beyond cities in the two control zones to investigate the impact of this historical event on all prefecture-level cities. Secondly, it focuses on the perspective of local fiscal revenue.

Thirdly, this study addresses the limitations of existing research, which has primarily focused on the “grabbing hand” behaviors of local governments in response to financial pressures since the fiscal decentralization reform in 1994. It enriches our understanding of fiscal centralization reforms and local government behavior in the Chinese-style fiscal decentralization system. The findings of this study reveal that when confronted with financial pressures resulting from environmental regulations, local governments employ not only the “grabbing hand” approach of extracting fiscal revenues from the market (e.g., through increased revenues from pollution fines to alleviate short-term financial pressures), but also the “helping hand” approach to develop financial resources (e.g., by enhancing tax administration efficiency to augment local tax revenues). It is the interplay between these two behaviors that gives rise to the diversity and complexity of local government behavior trajectories under Chinese-style decentralization.

Fourthly, previous studies have investigated the correlation between fiscal pressure and the impetus for financial resource growth by considering the abolition of agricultural tax reform [

19,

20,

21]. In contrast, this study aims to explore the connection between local fiscal pressure and the growth of financial resources resulting from environmental regulation, specifically focusing on the transformation of the incentive mechanism for the promotion of local officials.

2. Literature Review

In the face of escalating global environmental challenges, environmental regulation has become an essential policy tool for governments worldwide. Integrating environmental regulation into the assessment system of local officials aims to incentivize the greater involvement of local governments in environmental protection efforts. However, the effectiveness of this policy initiative in achieving a balance between ecological and economic dimensions has become a focal point of current research. A review of the literature reveals that existing studies on the impact of integrating environmental regulation into the assessment of local officials can be broadly categorized into ecological effects and economic effects.

2.1. Ecological Effects of Environmental Regulation

Integrating environmental regulation into the assessment system of local officials contributes to enhancing the emphasis of local governments on environmental protection. Numerous studies have indicated that this measure can significantly reduce pollutant emissions, improve air and water quality, and consequently enhance the overall ecological environment quality. For instance, research by Kahn et al., Chen et al., Chen B and He Y all confirm the positive impact of environmental regulation in improving the ecological environment [

9,

12,

22].

2.2. Economic Effects of Environmental Regulation

Firstly, from the perspective of enterprises, the economic effects of environmental regulations are examined, mainly focusing on the Pollution Haven Hypothesis [

23] and the Porter Hypothesis [

24]. The Pollution Haven Hypothesis suggests that stricter environmental regulations lead to the relocation of polluting industries to regions with lower environmental standards. Studies by Cai et al. and Li et al. support this view, noting a decrease in foreign direct investment due to stringent environmental regulations [

14,

25]. However, research also indicates that environmental regulations can incentivize firms to engage in technological innovation, thereby enhancing production efficiency. For instance, the study by Zhang and Zhao demonstrates that incorporating environmental regulations into the assessment of local officials stimulates innovation among local businesses [

26]. Moreover, Li et al. find in the garment industry that environmental regulations promote an increase in total factor productivity, confirming the Porter Hypothesis [

27]. Furthermore, environmental regulations can influence firms’ export behavior. Research by Shi and Xu shows that in pollution-intensive industries, stringent environmental regulations reduce the likelihood and volume of exports, indicating a certain impact of environmental regulations on firms’ international market competitiveness [

16].

Secondly, from a local perspective, environmental regulations may have a negative impact on the local economy. Research by Chen et al. confirms that when environmental regulations are integrated into the assessment system of local officials, these officials may sacrifice a portion of local GDP growth to meet the regulatory requirements [

9]. This suggests a certain balance between environmental regulations and local economic development. When formulating environmental policies, it is crucial to fully consider the capacity and development needs of the local economy. Additionally, a study by Zhang Jun et al. reveals a significant inhibitory effect of environmental regulations on local fixed asset investment [

17]. This could be attributed to the fact that companies need to allocate funds for pollution control, thus crowding out space for other investments.

Additionally, environmental regulations may also bring new opportunities for local economic development. Research by Luo Z and Qi B C found that among 85 cities in the Yangtze River Basin, strengthening environmental regulations did not negatively impact the banking sector; instead, it significantly boosted the coordinated development of the regional banking industry [

18]. This indicates the potential role of environmental regulations in driving the optimization of local industrial structures and the development of green finance. Moreover, environmental regulations may affect local tax rates. A study by Ye B and Lin L revealed that integrating environmental regulations into the assessment system of local officials can lead to an increase in local tax rates [

10]. This could be attributed to fiscal measures taken by local governments to offset environmental governance costs and improve public service levels.

2.3. Literature Review

In reviewing the literature, it is evident that environmental regulations play a complex and crucial role in balancing ecological protection and economic development. While existing studies have yielded rich results on the ecological and economic effects of environmental regulations, there are still some shortcomings and controversies. Particularly, research on how environmental regulations specifically impact local fiscal revenues remains relatively scarce. Despite a few studies (such as the studies by Luo Z and Qi B C, 2019) examining the relationship between environmental regulations and fiscal revenues from the perspective of local tax rates [

18], direct studies on the influence of regulatory assessment pressure on local fiscal revenues are lacking. This study aims to address this research gap by empirically analyzing the specific impact and mechanisms of environmental regulatory assessment pressure on local fiscal revenues. Changes in fiscal revenues can sensitively reflect the behavioral adjustments of local governments in response to regulatory assessment pressure. When environmental regulations are integrated into the assessment of local officials, local governments may adjust tax policies, increase non-tax revenues, and balance the relationship between economic development and environmental protection. These adjustments will be directly reflected in changes in fiscal revenues, providing a window through which to observe the behavioral adaptations of local governments.

3. Policy Background and Theoretical Hypotheses

3.1. Policy Background

3.1.1. Pollutant Emissions and Government Environmental Regulation: A Turning Point

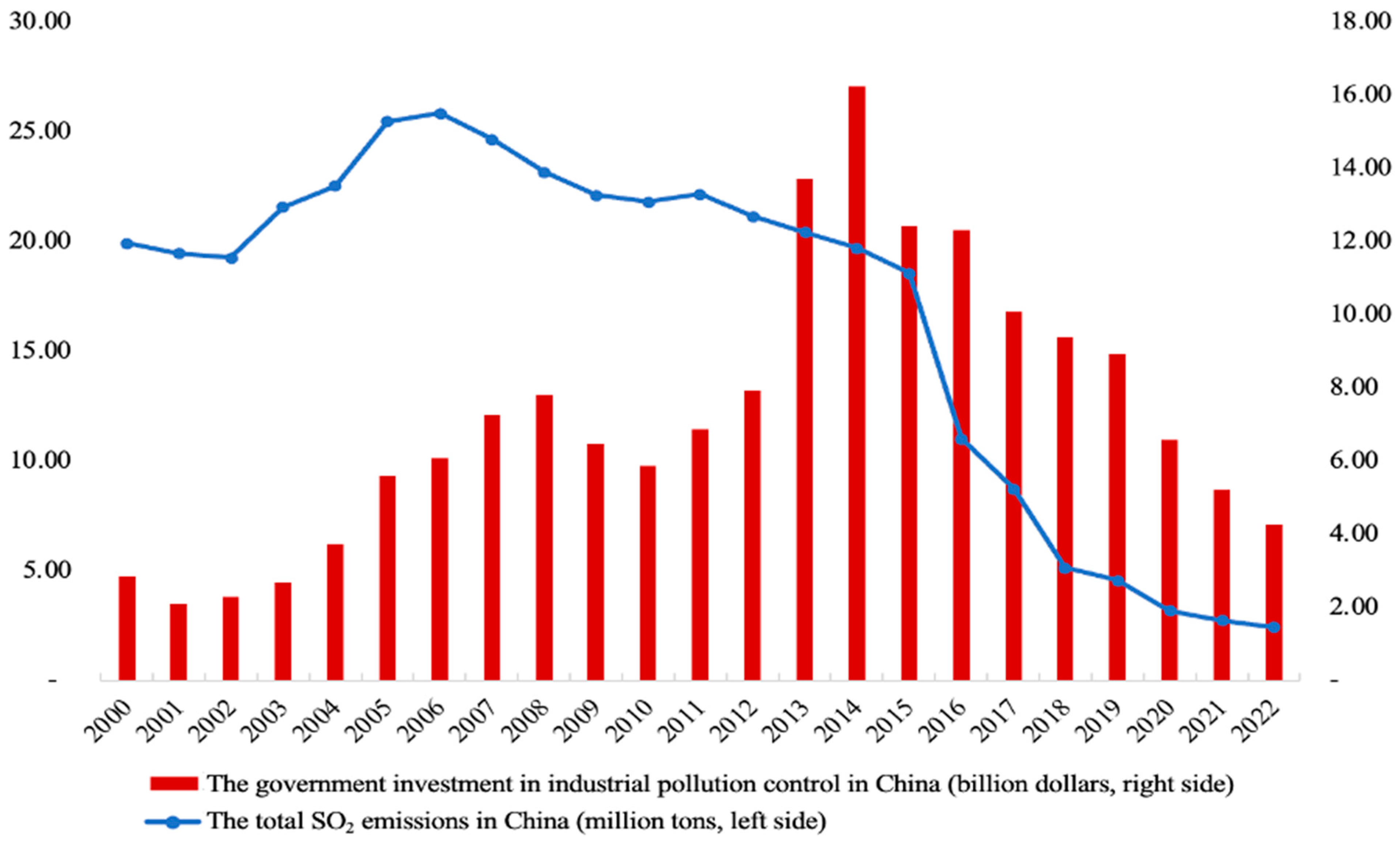

In the 1980s, China embarked on a path of reform and opening up, recognizing that environmental pollution posed a significant obstacle to sustainable economic development. Consequently, various levels of government introduced a range of measures aimed at atmospheric governance, including the implementation of the “Law on the Prevention and Control of Atmospheric Pollution” and the establishment of “Two Control Zones”. Despite the adoption of diverse policies and increased government investment in pollution control, the initial efforts to curb pollutant emissions proved unsatisfactory. As demonstrated in

Figure 1, sulfur dioxide emissions initially experienced a brief decline in 2000–2001, only to subsequently exhibit an upward trend, reaching a historic peak in 2005–2006, which contradicted the original policy objectives. In response, the central government incorporated emission targets of key pollutants into the assessment of local officials, thus directly challenging the detrimental trend of SO

2 emissions not decreasing, but instead increasing.

3.1.2. Conflict of Multi-tasks between Environmental Regulation and Fiscal Resource Growth

This study gathered data on the fiscal revenue target growth rates at the prefectural level across China from 2004 to 2018 by examining government work reports. As shown in

Figure 2, the temporal trends were characterized using the average and median values of the annual target growth rates at the city level. It was observed that the trends shown by the average and median values were generally consistent. Specifically, the fiscal revenue target growth rates exhibited an overall upward trend compared to 2005, despite fluctuations before 2013. This indicates the continued challenges in government financial resource growth even after the inclusion of environmental regulations in the promotion assessment of local officials. Local governments not only need to fulfill the task of reducing relevant pollutants but also have to consider the growth task of local fiscal revenue. In 2013, the Organization Department of the Communist Party of China made further structural adjustments to the assessment system for local officials, explicitly reducing the weight of GDP growth rate assessment. Only then did the fiscal revenue target growth rates of local governments at all levels start to decrease significantly.

After the fiscal decentralization reform in 1994, the mismatch between the self-owned revenue and expenditure responsibilities has led to long-term fiscal scarcity for local governments. Local governments have shouldered significant administrative responsibilities with limited fiscal authority, resulting in a severe fiscal deficit. Under existing financial pressures, certain behaviors of local governments have been distorted and alienated. For instance, there has been a focus on investment attraction, infrastructure development, and the exploitation of natural resources, which are characterized by high input, high energy consumption, and significant short-term economic benefits, known as the extensive development model [

3,

4,

5]. Undoubtedly, this has caused serious environmental pollution in the jurisdiction area. As shown in

Figure 3 below, we can observe an escalating severity of industrial SO

2 emissions since 2001, accompanying the continuous increase in the proportion of local government fiscal revenues. However, the trend of increasing the share of local fiscal revenues did not last for long, as there was a temporary setback between 2004 and 2006. One possible explanation for this is the gradual implementation of a pilot program to cancel agricultural taxes, which directly reduced the local tax base and thus negatively affected local financial resources.

Until the end of 2005, the inclusion of major pollutant emissions in the assessment of local officials marked a significant transformation in their promotion mechanism. This shift moved away from a sole focus on economic performance towards prioritizing the synergistic development of environmental protection and economic construction. As a result, there has been a consistent decline in the emission of SO2 pollutants over the years. Interestingly, our empirical evidence reveals that the implementation of environmental regulation policies did not negatively affect local finances. From 2006 to 2010, during the period of the Eleventh Five-Year Plan, the reduction in SO2 emissions corresponded with a year-on-year increase in the proportion of local fiscal revenue, overturning the previous declining trend. This demonstrates a win–win achievement among different goals and tasks for officials.

3.2. Theoretical Hypotheses

On the one hand, it is noteworthy that there seems to be a trade-off between environmental regulation and local fiscal growth. When the promotion evaluation system of officials shifts from pursuing a single-dimensional economic growth to emphasizing the multi-dimensional development of ecological environment and economy, firstly, local governments may begin to reduce investments in industries with high pollution, which could partially hinder local economic growth [

17]. Chen et al. discovered that environmental regulation in the “two control zones” significantly reduced sulfur dioxide emissions in the affected areas after 2005 [

9]; however, this reduction came at the cost of sacrificing a portion of local GDP growth. Secondly, under strict environmental regulation policies, numerous polluting enterprises may reduce or halt production, leading to a deteriorating balance sheet and making it difficult for them to repay bank loans [

18]. Ultimately, they may be forced to withdraw from the market due to an inability to bear the costs associated with clean production, which would result in a loss of local tax revenue. Additionally, as the intensity of environmental regulation increases, non-economic expenditures such as pollution control investments also rise, which may potentially squeeze out constructive investments and further weaken the financial capacity of local governments.

On the other hand, it is also possible to achieve a harmonious coexistence between environmental regulations and local financial growth. Under the mechanism of multiple goal assessment for officials, the financial pressure brought about by environmental regulations could serve as a catalyst for revenue growth. Firstly, incentivized by financial pressure, local governments are inclined to strengthen tax collection and management, expand taxation sources and bases, and directly generate fiscal revenue from the market, which is a trend for the government’s “helping hand” to shift towards a “grabbing hand” [

28,

29]. Secondly, to meet pollution emission targets, the government imposes stricter limits on enterprises, such as increasing fees for pollution treatment and emissions, thereby augmenting administrative charges and confiscated income, and ultimately bolstering local fiscal revenue. Additionally, in order to meet the assessment of pollutant reduction targets, the government will impose stricter pollution emission limits on enterprises, such as enhancing the collection of pollution fees from enterprises. The additional administrative charges and confiscated income will also enhance local fiscal revenue. Furthermore, a substantial body of literature supports the validation of the Porter Hypothesis, which proposes that environmental regulations can stimulate innovation in businesses and facilitate urban industrial transformation [

30,

31,

32].

Therefore, based on the above analysis, this study proposes competitive hypothesis 1:

H1a. Holding other conditions constant, integrating environmental regulations into the assessment of local officials will increase local fiscal revenues.

H1b. Holding other conditions constant, integrating environmental regulations into the assessment of local officials will decrease local fiscal revenues.

4. Estimation Strategy

4.1. Estimation Framework

The inclusion of pollution emission quotas in the performance evaluation system of local officials has been a subject of past empirical research primarily based on the triple differences method, which dissects the industry, region, and time dimensions to discern the impact of environmental regulations on various economic and social indicators. Due to data constraints, this study could not extend the examination to the industry level for local fiscal revenue. Another segment of empirical research relies on the double differences method to identify the environmental regulation policy, using whether local emission reduction targets exceed the median of all sample reduction targets to categorize high-emission-reduction-target regions. These regions are treated as the experimental group, while the low-reduction-target regions serve as the control group. However, a critical prerequisite of this method is that the implementation of the policy should not affect the local fiscal revenue of the control group, allowing it to serve as a counterfactual reference group for the experimental group, as mandated by the Stable Unit Treatment Value Assumption (SUTVA). Nevertheless, this assumption may not hold true when dealing with environmental regulation policies, as even areas with lower reduction targets may face some influence from the regulatory policy, albeit to a lesser extent. Hence, the traditional DID method may struggle to accurately capture the marginal impact of changes in environmental regulation intensity on local fiscal revenue. Additionally, this study focuses on the impact of environmental regulation assessment pressure on local fiscal revenue. This impact is likely to be continuous rather than discrete, considering the broad range within which environmental regulation intensity can vary. A continuous DID model can better capture this continuous impact, thus providing more precise estimates. With a continuous DID model, we can estimate the policy net effect of a one-unit change in environmental regulation intensity (i.e., pollution emission quotas). This method allows for a more nuanced analysis, aiding in uncovering the nonlinear relationship between environmental regulation and local fiscal revenue, which is unattainable through traditional DID analysis.

Therefore, in order to avoid this potential threat and to test the proposed competitive hypothesis (H1), this study takes the historical event of the initial adjustment of the target assessment system for local officials in China—the central government incorporated the SO

2 emission quota into the performance evaluation system of local officials in 2005—as a quasi-natural experiment, and utilizes the difference-in-differences (DID) method to examine whether local officials can achieve a win–win situation between environmental regulation and fiscal growth under the multi-tasking evaluation system. The DID estimation specification is presented in Equation (1):

where

contains our outcomes of concern (logarithm of the general budget revenue of local government) in city i at year t;

is the sulfur dioxide reduction target of local governments in city i during the Eleventh Five-Year Plan period, which refers to a measure of regulation stringency;

is a time dummy variable, and if t > 2005, Post = 1; otherwise = 0.

is the pre-determined variable which denotes the determinants of pollutant emission quota targets measured in the pre-treatment period, such as the standard deviation of the land slope (roughness), the average altitude (elevation), the annual average wind speed in the region from 2000 to 2003 (Wind_Speed), and average soil PH level of the topsoil (Soil_PH).

is a third-order polynomial function.

represents city-level control variables, including the degree of openness (trade), which is calculated by dividing the total import and export trade volume by the regional gross domestic product; foreign direct investment (FDI_RG), the total population at the end of the year (population); and the urbanization rate (urbanization). It should be noted that, in order to ensure the same trends of the control variables during the pre-policy period and further mitigate endogeneity issues, this study introduces an interaction between the time-invariant pre-determined variable and a third-order polynomial time trend.

represents city fixed effects,

represents year fixed effects, and

represents the random error term.

In addition, this study conducted a multicollinearity test on the above model, where the maximum Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) for a single variable was 4.25, and the average VIF for all variables was 3.74, which is less than 5. This indicates that the model does not suffer from severe multicollinearity issues.

The specific variable definitions and descriptive statistics are presented in

Table 1 below:

4.2. Data Source

This study takes 207 prefecture-level cities in China from 2002 to 2010 as samples. The core explanatory variable in this study, the target reduction rate of sulfur dioxide (target), was manually compiled from relevant government policy documents and official government websites. Since the emission reduction targets of prefecture-level cities are mostly formulated by municipal governments based on provincial government documents and are not uniformly published, a total of 207 city emission reduction targets were collected considering data availability. The explained variable and the control variables were sourced from the “China Urban Statistics Yearbook” and “China Regional Economic Statistics Yearbook”, while the pre-determined variables were sourced from the “China Regional Statistics Yearbook”.

Considering the fiscal reform of China implemented in 2002, which turned income tax revenue into shared tax revenue between the central and local governments, leading to a further reduction in local government tax revenues, and the conclusion of the “Eleventh Five-Year” plan in 2010, the sample period for this study was selected as 2002–2010.

5. Main Results

5.1. Baseline Estimates

Table 2 reports the regression results of the baseline model specified in Equation (1). Column 1 presents results with only the city and year fixed effects included. The interaction between

and

is positive and statistically significant, indicating that the implementation of target-based environmental regulations has contributed to the growth of local revenue after the change in the promotion and evaluation mechanism for local officials. To alleviate the concern that our estimate is biased due to the non-random formulation of SO

2 reduction targets, we include interactions between pre-determined variables and a third-order polynomial function of time in column 2. We continue to find a positive and statistically significant estimate of

. And in column 3, we further include city-level control variables, and the estimate of

remains consistently positive and statistically significant. Additionally, for each 0.01 growth of the SO

2 reduction target, there is a corresponding 0.204% increase in local fiscal revenue.

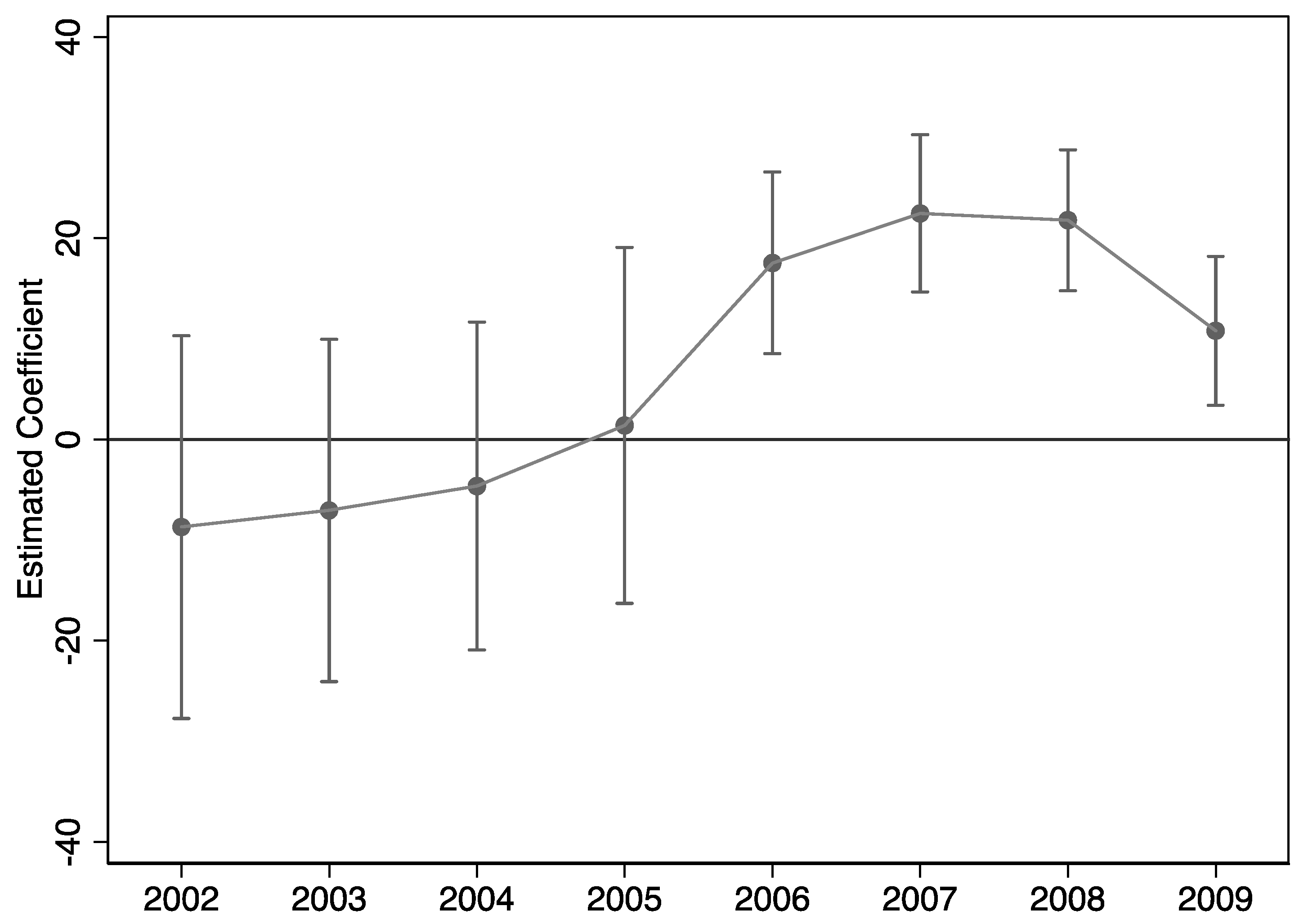

5.2. Dynamic Effects Analysis

This study employs the event study method to conduct a dynamic effects analysis. The specification is given by

where

is a time dummy variable and the other variables are the same as those in Equation (1). In this analysis, the focus is on the interaction coefficient,

, which determines whether the parallel trend assumption holds or not. The results in

Table 3 reveal that regardless of the inclusion of control variables, using 2005 as the baseline, the estimated coefficients for the pre-policy period (2002–2005) are not statistically significant, whereas the post-policy period (2006–2009) coefficients are significantly positive. This validates the assumption of parallel trends and the exogeneity of the policy. Moreover, it suggests that incorporating sulfur dioxide pollution emissions into the evaluation of local officials has sustained positive effects on local fiscal development. The dynamic effects of the core explanatory variable’s regression coefficient in column 2 of

Table 3 are visually represented in the graph, which displays the 95% confidence intervals.

The dynamic effects of the regression coefficient of the core explanatory variable in the second column of

Table 3 are visualized in

Figure 4, with a confidence interval of 95%. As depicted in the figure, prior to the implementation of the policy, the correlation coefficient fluctuated within a range close to zero without statistical significance. However, after the policy was implemented, the correlation coefficient exhibited a significant positive value, further corroborating the fulfillment of the parallel trend assumption.

6. Robustness Test

To ensure the robustness of the regression results, this study conducted the following robustness tests:

6.1. Inclusion of Other Policies

During the “Eleventh Five-Year Plan”, the central government not only incorporated the pollution reduction targets into the performance evaluation system of local officials, but also specified energy consumption reduction targets. However, there is an endogeneity problem between energy consumption reduction targets and the production of enterprises. In order to minimize interference caused by variations in the energy consumption reduction targets of different cities, this study draws on the method of Han C et al. (2017), analyzing only the samples of 20 cities (The 20 cities included in this analysis are Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei, Liaoning, Heilongjiang, Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Anhui, Jiangxi, Henan, Hubei, Hunan, Chongqing, Sichuan, Guizhou, Shaanxi, Gansu, Ningxia, and Xinjiang. The energy consumption reduction targets of other cities are Shanxi: 25%; Inner Mongolia: 25%; Jilin: 30%; Fujian: 16%; Shandong: 22%; Guangdong: 16%; Guangxi: 15%; Hainan: 12%; Yunnan: 17%; Tibet: 12%; and Qinghai: 17%.) that align with the target of reducing energy consumption per unit of GDP by 20% [

33]. Moreover, there is another reform concerned that may impact the results, which began in 2000 by regulating and strengthening the distribution system of agricultural taxes and ended in 2006 with the abolition of agricultural taxes. To control for the impact of this reform, we further included the proportion of primary industry GDP (PriGDP) as a control in Equation (1). The regression results are presented in column 1 of

Table 4. Controlling for these relevant policies, the coefficient of

remains significantly positive. Additionally, the coefficient of PriGDP is significantly negative, indicating that regions with a higher proportion of agricultural sectors face more challenges in local fiscal development when subjected to stricter environmental regulations.

6.2. Replacing the Continuous Treatment Variable Targeti with 0–1 Dummy Variable

In this study, the continuous treatment variable

was replaced with a 0–1 dummy variable by grouping it according to the median. Specifically, the reduction targets of each city were compared to the median reduction target of the entire sample in order to differentiate between regions with high and low emission reduction targets. If the reduction target in city i is greater than the median, the

= 1 (indicating high-reduction-target areas); if it is smaller, the

= 0 (indicating low-reduction-target areas). The regression results, displayed in column 2 of

Table 4, demonstrate that the coefficient of

remains significantly positive, indicating that incorporating pollutant emission quotas into the evaluation of local officials promotes local revenue growth with higher emission reduction targets.

6.3. Exclusion of Summer Olympic Games Venue Cities

The 2008 Summer Olympics presented stricter requirements for urban environmental regulations. In order to assess whether the estimates in this study were affected by the hosting cities, we excluded three co-hosting cities (Shenyang, Qinhuangdao, and Qingdao) from the sample and re-estimated Equation (1). From the results presented in column 3 of

Table 4, we continue to find a positive and statistically significant estimate of

, suggesting that the estimate in this study is not driven by these potential cities.

6.4. Replacing the Local Fiscal Revenue with Local GDP

Fiscal revenue represents the monetary income obtained by the government sector and serves as an important indicator for measuring government fiscal capacity. The scope and quantity of public goods and services provided by the government in social and economic activities are largely determined by the adequacy of fiscal revenue. In contrast, a city’s gross domestic product (GDP) is the total output value of the region, reflecting its economic performance. In this study, we replaced the variable of fiscal revenue with the proportions of local GDP contributed by the primary, secondary, and tertiary industries. This approach allows us to examine the impact of environmental regulations on regional industrial transformation and upgrading. The regression results, as shown in columns 4–6 of

Table 4, reveal that the estimate of

on the secondary industry is negative and statistically significant, while the estimate of

on the tertiary industry is positive and statistically significant. This indicates that the industrial structures of cities are gradually transforming and upgrading as the regional environmental regulations become increasingly stringent. Compared to manufacturing or industry, the tertiary sector is less negatively affected by environmental regulations. Regional environmental improvements can promote the development of high-end service industries, real estate, tourism, and other sectors, thereby driving the coordinated development of local fiscal resources. However, this shift in industrial structure may also be a passive result of declining output in the secondary sector due to the impact of environmental regulations.

6.5. Inclusion of Regional Linear Time Trend

In order to control for the aggregate time trend, this study includes the regional linear time trend terms in Equation (1), i.e.,

, where these terms cover four regions: Northeast, East China, Central China, and West China. The results, as shown in column 7 of

Table 4, reveal that the estimate of

remains positive and statistically significant, which indicates that the estimated values of this study are not affected by the aggregate trend.

6.6. Inclusion of Additional Time-Varying City Characteristics

The total investment in local pollution control (Invest_pollu), the total investment in urban environmental facilities (Invest_faci), and the number of employees in urban water, environmental, and public facility management (Envir_worker) also have an impact on environmental regulation. Therefore, we included these three control variables in Equation (1). From the results presented in column 8 of

Table 4, we continue to find a positive and statistically significant estimate of

.

The robustness tests conducted above indicate that the main regression conclusions in this study are robust. Therefore, we can reasonably derive a core finding of this study: under the incentive of the political promotion mechanism for officials, the pressure of environmental regulation for local officials can provide impetus for the growth of local fiscal revenue, thereby achieving a win–win situation among multiple objectives.

7. Endogenous Problems

The endogeneity problems in this study mainly arise from the non-random determination of the SO2 emission targets for local officials, leading to a biased estimation of β. To alleviate the adverse impact of endogeneity on the research results, this study controls for a range of various urban feature variables as much as possible. Although the dynamic test of the policy in this study may partially reflect the exogeneity of this policy, we still have concerns about the influence of other potential contemporaneous confounding factors. Thus, in order to further address the aforementioned endogeneity issue, we further employed the instrumental variables (IVs) strategy for estimation.

Based on the studies of Hering and Poncet, Cai et al., and Shi X, Xu Z F, this study utilizes the ventilation coefficient as an instrumental variable for the environmental regulation policy [

14,

16,

34]. According to the Box model, the diffusion of atmospheric pollutants is mainly determined by two variables: wind speed, where higher wind speeds facilitate the horizontal dispersion of pollutants, and atmospheric boundary layer height, which affects the vertical dispersion of pollutants [

35]. The ventilation coefficient is a variable calculated based on the product of wind speed and mixing height. The specification is given by

where the variables

represent the ventilation coefficient, windspeed, and atmospheric boundary layer height of city i in year t, respectively. In this study, meteorological data for windspeed and atmospheric boundary layer height at a height of 10 m were collected from the European Center for Medium-Term Weather Forecasting (ECMWF) ERA database. These data, which were used to measure the mixed layer height of 75 × 75 grid cells, were then matched with the latitude and longitude of each city using the ArcGIS (10.8) software. The ventilation coefficient used in this study was the average coefficient of the nearest grid cell to each city from 1999 to 2004. A higher ventilation coefficient indicates a faster diffusion speed of air pollution, which may lead to lower concentrations of SO

2, thereby necessitating stricter environmental regulations [

34].

The use of instrumental variables must meet the underlying assumptions of both relevance and exogeneity. It requires a strong correlation with the endogenous variable (SO2 target reduction) while being unrelated to the error term. On the one hand, a higher value of the ventilation coefficient indicates a lower observed level of SO2 emissions, suggesting stricter local environmental regulations. Therefore, there is an expected positive correlation between the ventilation coefficient and the stringency of environmental regulations, satisfying the relevance assumption of instrumental variables. On the other hand, the ventilation coefficient is determined by intricate meteorological systems and geographical conditions, which satisfies the exogeneity assumption of instrumental variables. It is worth emphasizing that using the ventilation coefficient as the instrumental variable can help to effectively control for the spatial spillover effects of SO2 pollution, enabling an accurate identification of the governance effectiveness of government environmental regulations.

The two-stage estimation results of the instrumental variable approach are reported in

Table 5. The first-stage estimation reveals a significantly positive correlation between the instrumental variable ventilation coefficient and the endogenous variable, satisfying the relevance assumption of instrumental variables. Additionally, the first-stage F-value exceeds the critical value of 10, indicating the absence of weak instruments [

36]. In the second-stage estimation, we continue to find a positive and statistically significant estimate of

, reveling that our results do not suffer from significant endogeneity bias.

8. Heterogeneity Analysis

In the analysis of heterogeneity, our main focus lies in the heterogeneity effects of fiscal self-sufficiency. We aim to determine the fiscal revenue growth effects of environmental regulatory pressures on regions with high and low fiscal self-sufficiency of the local government. Fiscal self-sufficiency refers to the ratio between general budgetary revenue and expenditure, primarily measuring the financial capacity of the government. A higher fiscal self-sufficiency indicates a more abundant government finance and stronger resilience. Based on the tertiles of fiscal self-sufficiency, we separated the sample into three groups: high, moderate, and low levels.

The results of the heterogeneity tests are reported in columns 1–3 of

Table 6. We find that the estimates for

do not exhibit statistical significance within the groups of high and low fiscal self-sufficiency, whereas they demonstrate statistical significance within the medium-level fiscal self-sufficiency group. This is due to the fact that cities with high fiscal self-sufficiency possess strong fiscal capabilities, resulting in a reduced impact from environmental regulatory pressures and less apparent motivation for fiscal development. Conversely, cities with low fiscal self-sufficiency exhibit weak fiscal strength and insufficient resilience, making it difficult to convert the pressure of environmental regulations into a motivation for fiscal growth. Fiscal self-sufficiency implies that local government expenditures primarily rely on their own financial resources. Cities with medium-level fiscal self-sufficiency must exert more effort to mitigate the fiscal pressure resulting from environmental regulations, thereby cultivating a stronger impetus to enhance fiscal revenue.

9. Mechanism Analysis

The regression results above indicate that, driven by the incentives in the promotion mechanism for local officials, local fiscal revenues increase significantly along with the strengthening of pollution control. This suggests that environmental regulatory pressure can generate the momentum for fiscal development, leading to a win–win situation in achieving multiple policy goals. However, these empirical findings only establish the correlation between environmental regulation and revenue growth, without revealing the mechanisms.

Following the transformation of the promotion incentive mechanism, local officials encounter pressure from two primary aspects: Firstly, they are strongly motivated to allocate more fiscal funds towards pollution control to fulfill SO2 reduction targets, consequently exerting increased financial burden on local governments. Secondly, within the framework of stringent environmental regulations, certain enterprises in high-pollution industries may find it unfeasible to bear the costs of pollution treatment, compelling their exit from the market and leading to a further decline in local tax revenue. The amalgamation of these diverse pressures significantly manifests as financial burden upon local governments. As a result, actively pursuing fiscal revenue becomes a crucial approach for local officials to address such pressures, culminating in the distinctive Chinese-style “pressure-based” fiscal incentives.

When confronted with financial pressures resulting from environmental regulations, local governments employ not only the “grabbing hand” approach, which involves extracting fiscal revenues from the market by reducing the fixed assets investment of local governments and enhancing the collection of pollution fees from enterprises, but also the “helping hand” approach to develop financial resources, such as enhancing tax administration efficiency by cracking down on the under-reporting of profits and income tax evasion among enterprises. Therefore, this section will focus on analyzing and examining various possible approaches at the level of both the “grabbing hand” and the “helping hand” for local governments.

9.1. Environmental Regulation and Non-Tax Revenue of Local Governments

On the one hand, local governments may adopt a contractionary fiscal policy, such as reducing expenditures on high-polluting infrastructure construction and fixed asset investments, which can alleviate fiscal pressure and facilitate the return of certain financial resources. On the other hand, with the inclusion of environmental regulations in officials’ performance assessments, governments will be motivated to impose stricter pollution emission restrictions on enterprises, whether to meet emission targets or to mitigate the fiscal pressure from environmental regulations. This may involve expanding the collection of pollution treatment fees, discharge fees, and other administrative charges, which can contribute to an increase in local government revenue.

Based on the aforementioned analysis, the pathways for local revenue growth to be examined in this study include reducing fixed asset investment (FA) and strengthening the collection of pollution treatment fees from enterprises (Sewage_fee). The regression results of the relevant mechanism analysis are shown in

Table 7. From column 1, we find a negative and statistically significant estimate of

. Fixed asset investment is generally associated with high-polluting and energy-intensive industries. After changes in the officials’ assessment mechanism, local governments tend to prefer environmentally friendly production factors, such as human resources, and reduce their investments in fixed assets, directly alleviating certain fiscal pressures. From column 2, we find a positive and statistically significant estimate of

, indicating that in order to meet the assessment targets of environmental regulations, governments will compete to raise the threshold for pollution emissions. As a result, some enterprises may choose to bear the high costs of penalties due to their inability to meet emission standards. Ultimately, these costs incurred by companies become a part of the growth in local revenue.

9.2. Environmental Regulation and Tax Revenue of Local Governments

Generally, there are three main approaches to develop local fiscal revenue: firstly, expanding the tax base, which involves increasing taxpayers’ tax-paying capacity; secondly, enhancing tax collection efforts by strengthening the management and collection of taxes from enterprises; and lastly, increasing transfers from the central government to local governments. It should be noted that the mechanism analysis focuses more on revealing the results of local government proactive actions rather than examining market changes. Therefore, the first approach is not analyzed here. Additionally, due to the limited availability of data, the third approach of transfer payments cannot be verified. The present research narrowly concentrates on the second approach, which is to estimate whether environmental regulations can develop local fiscal resources by strengthening the efficiency of tax collection from enterprises. The specification is given by

where the subscript i represents the prefecture-level city, the subscript p represents the enterprise, and the subscript t represents the year. According to previous studies, the dependent variables

primarily consist of the following: (1) VATrate is the actual value-added tax rate, which is defined as “enterprise’s value-added tax/enterprise added value”; (2) Cor_taxrate is the actual corporate income tax rate, defined as “enterprise income tax payable/total corporate profits”; (3) Profit_Gaprate is the rate of corporate profit misreporting, defined as “(estimated profit − reported profit)/total value-added”, where “estimated profit = sales − intermediate inputs − financial expenses − total wages paid − depreciation − tax paid on value-added − profit before tax” [

19,

21,

37]. The control variables

not only include city-level control variables as mentioned in the baseline model (1), but also incorporate some enterprise-level control variables (capital, sales, SOE, and mobility) whose specific definitions are provided in

Table 1. The remaining variables are consistent with the baseline model (1).

The results are reported in

Table 8. It can be seen from column 1 that the estimate of

is negative and statistically significant, which suggests that after incorporating environmental regulations into the assessment of local officials, the local government does not prefer to strengthen the actual tax rate of the income tax for pollution industries as a means to alleviate fiscal pressure. However, this may not contradict the conclusions of this study. From the results in column 3, we observe a negative and statistically significant estimate of

, which implies that the main approach of the local government in administrating the income tax is to combat under-reported profits and tax evasion, rather than increasing the effective tax rate faced by enterprises. Therefore, the strengthening of tax administration leads to an increase in reported profits by enterprises, resulting in a higher amount of income tax payment under a constant effective tax rate.

From column 2 in

Table 8, we find that the estimate for

does not exhibit statistical significance, indicating that there is no significant change in the actual value-added tax (VAT) rate for enterprises after the implementation of environmental regulations. One possible reason for this is that the VAT is collected by the national tax authority, which operates under a vertical management system and is considered independent from the local government in terms of tax administration.

Based on the aforementioned analysis, we can observe several strategies employed by local governments to alleviate the fiscal pressure caused by environmental regulations. Firstly, local governments may reduce fixed asset investments and strengthen the collection of pollution treatment fees to achieve short-term fiscal revenue growth. Secondly, local governments also tend to combat under-reported profits and tax evasion by enterprises as a means to alleviate fiscal pressure.

10. Discussion

This study, through empirical analysis, found a significant impact of environmental regulation assessment pressure on local fiscal revenue. Specifically, when local governments face stricter environmental regulation assessments, they take a series of measures to increase fiscal revenue to alleviate the economic pressure brought about by environmental protection. These measures include strengthening tax collection and expanding non-tax revenue. In comparison with previous studies, the innovation of this study lies in directly focusing on the relationship between environmental regulation assessment pressure and local fiscal revenue and revealing the underlying mechanisms. This finding is of great significance in understanding the behavioral strategies of local governments under environmental regulations. Additionally, the heterogeneity analysis in this study indicates that the level of local fiscal self-sufficiency constrains the extent to which environmental regulations affect fiscal revenue. This finding further emphasizes the important influence of regional economic development levels and fiscal conditions on the strategic choices of local governments.

It is essential to further consider why local governments adopt the strategy of increasing fiscal revenue when facing environmental regulation assessment pressure. This may be related to the promotion incentive mechanisms of local governments. Under the current political–economic system, the evaluation system of local governments often has multiple objectives, with fiscal revenue being an important indicator of economic development performance. Therefore, when facing stricter environmental regulation assessments, local governments may increase fiscal revenue to offset the economic losses caused by environmental protection, ensuring a balance between economic development and environmental protection. Furthermore, Chinese local governments hold significant power. Zhou Li’an proposed the concept of “administrative franchising” as an analytical framework to understand the vertical government relations in China [

38]. The characteristics of administrative franchising involve the distribution of power between the principal and the agent, where the agent enjoys considerable discretion and de facto power to act according to their own methods. Within this framework, local governments will utilize their abundant means to respond to policies.

Of course, it is also necessary to note that there are two shortcomings in this study. First, the empirical testing period is relatively short, which makes the conclusions of this study mainly short-term, focusing on the short-term fiscal revenue growth effect in response to fiscal pressure shocks faced by local governments. The medium-to-long-term effects require further research. Second, using environmental regulations as the impact of fiscal pressure in this study has led to some conclusions with a degree of generality. For example, an increase in fiscal pressure does not inhibit local government’s fiscal construction behaviors, and inappropriate fiscal incentive designs may lead to unintended negative consequences. However, the extended policy implications need to be approached with caution because different fiscal incentive systems and varying market environments at different times can yield different results. Therefore, how to better design fiscal incentive systems requires more in-depth and meticulous theoretical and empirical research. This represents an important future research direction.

11. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

In this study, we examine the effect of a target-based performance evaluation system on SO2 emission reduction. We find that when SO2 emissions quotas were incorporated into the evaluation system for local bureaucrats, local fiscal revenue was significantly increased. Furthermore, for each 0.01 increase in the reduction in environmental regulation targets, there was a corresponding 0.204% increase in local fiscal revenue. Our mechanism analysis further confirms that local governments employ various strategies to alleviate the financial burden induced by environmental regulations. These strategies include, (1) not only adopting the “grabbing hand” approach, which involves extracting fiscal revenues from the market by reducing the fixed asset investment of local governments and enhancing the collection of pollution fees from enterprises, (2) but also utilizing the “helping hand” approach to augment financial resources, such as improving tax administration efficiency by cracking down on profit under-reporting and income tax evasion among enterprises. Our findings contribute to a deeper understanding of the challenges related to multi-tasking agency problems encountered by government agents. Additionally, this study conducted an analysis on the heterogeneous effect of fiscal self-sufficiency. The findings reveal that the fiscal growth effect due to environmental regulatory pressure is not significant in areas with both high and low fiscal self-sufficiency, but it exhibits a positive and significant growth effect in areas with moderate levels of fiscal self-sufficiency. This disparity can be attributed to the fact that areas with high fiscal self-sufficiency have robust fiscal capacities, which mitigate the impact of environmental regulatory pressure and diminish the incentive for fiscal resource development. Conversely, areas with low fiscal self-sufficiency display limited local fiscal capacities, hindering the conversion of regulatory pressure into a driving force for fiscal resource enhancement. Consequently, this results in an insignificant growth effect.

The results of this study demonstrate that although strict environmental regulations may have some negative impacts on the industrial production activities of enterprises, and local governments may invest more in environmental pollution control measures to meet emission reduction targets, overall, this has not led to significant financial pressure on local governments. A healthy environment also contributes to local development, and the pressure from strict environmental regulations for local bureaucrats provides motivation for the coordinated development of local fiscal resources. Therefore, the current implementation of environmental regulations is a win–win situation for both ecological environment protection and fiscal growth, achieving both beautiful natural scenery and economic prosperity. The heterogeneity analysis in this study tells us that when setting environmental regulation targets, it is necessary to consider not only the incentive mechanisms for officials’ promotion, but also macro factors such as the local economic level and the historical geographic environment of the locality, as well as the local financial self-sufficiency capacity.

This study proposes the following policy recommendations: Firstly, the government should further design and improve the performance evaluation system for officials’ environmental pollution control, including the reasonable setting of environmental performance evaluation weights, scenario-based dynamic evaluation based on local initial endowments, and diversified and coordinated supervision and evaluation mechanisms. Secondly, efforts should be made to establish a differentiated and precise coordination and cooperation mechanism for environmental pollution control, including general functional pollution control mechanisms, special rectification and prevention mechanisms, ecological functional zone warning mechanisms, cross-regional pollution control linkage mechanisms, and emergency response mechanisms for major pollution incidents. This will help local officials timely assess, provide feedback, and adjust the scale and structure of attention and resource allocation. Thirdly, the design of fiscal incentive systems should be optimized, giving appropriate policy tools to local governments and guiding them to develop in a direction that is beneficial to economic and social harmony, as well as economic and natural harmony.