Age-Inclusive Healthcare Sustainability: Romania’s Regulatory and Initiatives Landscape in the European Union Context

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Self-Sufficiency and Healthcare

3. European Context toward Age-Friendly Environments

3.1. Age-Friendly Environments Reflected in Scientific Literature

3.2. The Frame at the European Union Level

- European Innovation Partnership on Active and Healthy Ageing—EIP-AHA: http://www.scale-aha.eu (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- Reference Site Collaborative Network—RSCN: https://www.rscn.eu/ (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- European Centre Social Welfare Policy: https://www.euro.centre.org/ (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- European Health Telematics Association—EHTEL: https://www.ehtel.eu/ (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- AGE platform Europe: https://www.age-platform.eu/ (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- European Innovation Partnership on Active and Healthy Ageing [55,56]: https://www.rscn.eu/ (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- ECHAlliance: https://echalliance.com/ (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- Global Network for Age-friendly Cities and Communities: https://extranet.who.int/agefriendlyworld/who-network/ (accessed on 10 July 2023).

4. Age-Friedly Environments in Romania

4.1. Romania Characteristics

4.2. National Regulations and Recommendations

4.3. Networks and Associations

4.4. Current Funded Age-Friendly Projects

4.5. Future Regional and National Project Calls

5. Limitations and Further Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Environmentally Sustainable Health Systems: A Strategic Document. 7 February 2017. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-EURO-2017-2241-41996-57723 (accessed on 27 January 2024).

- Sustainable Healthcare. Encyclopedia, Science News & Research Reviews. Available online: https://academic-accelerator.com/encyclopedia/sustainable-healthcare (accessed on 27 January 2024).

- European Commission, Directorate General for Environment. Sustainable Development 2020. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/sustainabledevelopment (accessed on 27 January 2024).

- European Commission. Energy Intelligent, Energy Europe; Towards Zero Carbon Hospitals with Renewable Energy Systems, 2020. (Updated on September 2020). Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/energy/intelligent/projects/en/projects/res-hospitals (accessed on 27 January 2024).

- Muschol, J.; Heinrich, M.; Heiss, C.; Hernandez, A.M.; Knapp, G.; Repp, H.; Schneider, H.; Thormann, U.; Uhlar, J.; Unzeitig, K.; et al. Economic and Environmental Impact of Digital Health App Video Consultations in Follow-up Care for Patients in Orthopedic and Trauma Surgery in Germany: Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e42839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickard Strange, M.; Booth, A.; Akiki, M.; Wieringa, S.; Shaw, S.E. The Role of Virtual Consulting in Developing Environmentally Sustainable Health Care: Systematic Literature Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e44823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fragão-Marques, M.; Ozben, T. Digital transformation and sustainability in healthcare and clinical laboratories. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2022, 61, 627–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, A.; Severn, M. Reducing the Environmental Impact of Clinical Care: CADTH Horizon Scan; Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2023. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK596637/ (accessed on 27 January 2024).

- Samuel, G.; Sims, J.M. Drivers and constraints to environmental sustainability in UK-based biobanking: Balancing resource efficiency and future value. BMC Med. Ethics 2023, 24, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zohouri, M.; Ghaderi, A. The Significance of Biobanking in the Sustainability of Biomedical Research: A Review. Iran. Biomed. J. 2020, 24, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samuel, G.; Lucivero, F.; Lucassen, A.M. Sustainable biobanks: A case study for a green global bioethics. Glob. Bioeth. 2022, 33, 50–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cresswell, K.; Anderson, S.; Montgomery, C.; Weir, C.J.; Atter, M.; Williams, R. Evaluation of Digitalisation in Healthcare and the Quantification of the “Unmeasurable”. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2023, 38, 3610–3615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaihlanen, A.M.; Laukka, E.; Nadav, J.; Närvänen, J.; Saukkonen, P.; Koivisto, J.; Heponiemi, T. The effects of digitalisation on health and social care work: A qualitative descriptive study of the perceptions of professionals and managers. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarpani, R.R.Z.; Gallego-Schmid, A. Environmental impacts of a digital health and well-being service in elderly living schemes. Clean. Environ. Syst. 2024, 12, 100161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Cohen, G.; Sharma, B.; Yin, H.; McConnell, R. Sustainability in Health Care. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2022, 47, 173–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Ageing Europe. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/cache/digpub/ageing (accessed on 7 July 2023).

- European Commission, Economic and Financial Affairs. The 2018 Ageing Report: Underlying Assumptions and Projection Methodologies. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/publications/economy-finance/2018-ageing-report-underlying-assumptions-and-projection-methodologies_en (accessed on 7 July 2023).

- Fleck, A. Where Do People Retire The Earliest (And Latest)? Available online: https://www.statista.com/chart/29570/european-average-effective-labor-market-exit-ages/ (accessed on 20 December 2023).

- Bloom, D.E.; Chatterji, S.; Kowal, P.; Lloyd-Sherlock, P.; McKee, M.; Rechel, B.; Rosenberg, L.; Smith, J.P. Macroeconomic implications of population ageing and selected policy responses. Lancet 2015, 385, 649–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ezeh, A.C.; Bongaarts, J.; Mberu, B. Global population trends and policy options. Lancet 2012, 380, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prince, M.J.; Wu, F.; Guo, Y.; Gutierrez Robledo, L.M.; O’Donnell, M.; Sullivan, R.; Yusuf, S. The burden of disease in older people and implications for health policy and practice. Lancet 2015, 385, 549–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OECD. Elderly Population. Available online: https://data.oecd.org/pop/elderly-population.htm (accessed on 20 December 2023).

- World Health Organization Active Ageing: A Policy Framework. 2002. Available online: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2002/WHO_NMH_NPH_02.8.pdf?ua=1 (accessed on 20 December 2023).

- WHO. Global Age-Friendly Cities: A Guide; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/51971/retrieve (accessed on 7 July 2023).

- European Innovation Partnership on Active and Healthy Ageing. Available online: https://www.esn-eu.org/european-innovation-partnership-active-and-healthy-ageing (accessed on 7 July 2023).

- Dantas, C.; van Staalduinen, W.; Jegundo, A.; Ganzarain, J.; Van Der Mark, M.; Rodrigues, F.; Illario, M.; De Luca, V. Smart Healthy Age-Friendly Environments—Policy Recommendations of the Thematic Network SHAFE. Transl. Med. UniSa 2019, 19, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dantas, C.; van Staalduinen, W.; Jegundo, A.; Ganzarain, J. Smart Healthy Age-Friendly Environments—Funding models and best practices. Int. J. Integr. Care 2019, 19, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Regional Office for Europe. Creating Age-Friendly Environments in Europe: A Handbook of Domains for Policy Action; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2017; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1302607/retrieve (accessed on 7 July 2023).

- WHO Regional Office for Europe. Age-Friendly Environments in Europe: Indicators, Monitoring and Assessments. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1302979/retrieve (accessed on 7 July 2023).

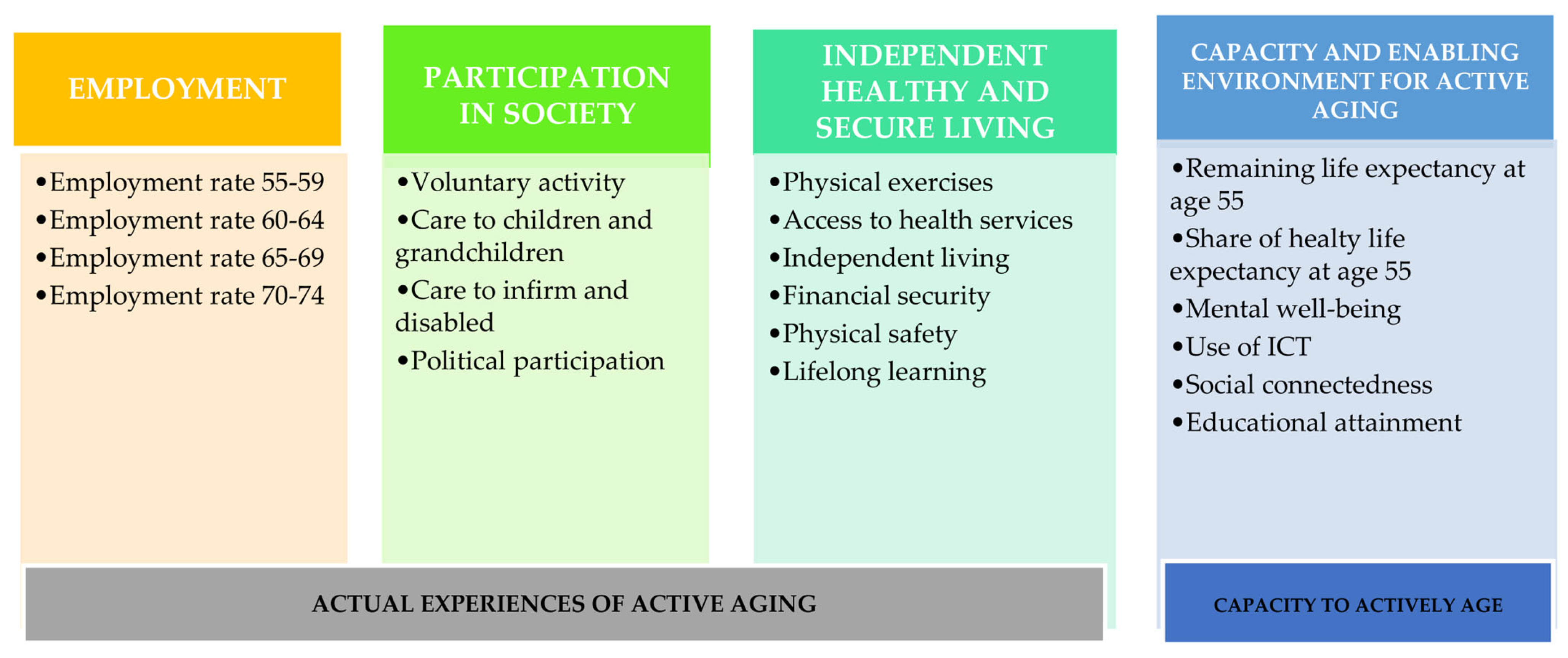

- UNECE. Active Ageing Index; United Nations Economic Commission for Europe: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; Available online: https://statswiki.unece.org/display/AAI (accessed on 7 July 2023).

- WHO. Measuring the Age-Friendliness of Cities: A Guide to Using Core Indicators; World Health Organization: Kobe, Japan, 2015; Available online: http://www.who.int/kobe_centre/publications/AFC_guide/en/ (accessed on 7 July 2023).

- Active Ageing Index Home. III. Do it Yourself! Active Aging Index; United Nations Economic Commission for Europe: Geneva, Switzerland; Available online: https://statswiki.unece.org/pages/viewpage.action?pageId=76287845 (accessed on 7 July 2023).

- Finkelstein, R.; Garcia, A.; Netherland, J.; Walker, J. Toward an Age-Friendly New York City: A Findings Report; The New York Academy of Medicine: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Plouffe, L.; Kalache, A. Towards global age-friendly cities: Determining urban features that promote active aging. J. Urban Health 2010, 87, 733–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggs, S.; Tinke, A. What Makes a City Age-Friendly? London’s Contribution to the World Health Organisation’s Age-Friendly Cities Project; Institute of Gerontology, King’s College London (University of London) and Help the Aged: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- The Ontario Senior’s Secretariat, The Accessibility Directorate of Ontario, The University of Waterloo, McMaster University (2013) Finding the Right Fit—Age-Friendly Community Planning. Available online: http://www.seniors.gov.on.ca/en/resources/AFCP_Eng.pdf (accessed on 7 July 2023).

- Centre for Mental Health Research, Australian National University (2011) A Baseline Survey of Canberra as an Age-Friendly City. Available online: http://www.cepar.edu.au/media/112955/age_friendly_canberra_final_version.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- Wong, M.; Chau, P.H.; Cheung, F.; Phillips, D.R.; Woo, J. Comparing the age-friendliness of different neighbourhoods using district surveys: An example from Hong Kong. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, 31526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chui, C.H.; Tang, J.Y.M.; Kwan, C.M.; Fung Chan, O.; Tse, M.; Chiu, R.L.H.; Lou, V.W.Q.; Chau, P.H.; Leung, A.Y.M.; Lum, T.Y.S. Older Adults’ Perceptions of Age-friendliness in Hong Kong. Gerontologist 2019, 59, 549–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, M.; Yu, R.; Woo, J. Effects of Perceived Neighbourhood Environments on Self-Rated Health among Community-Dwelling Older Chinese. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Au, A.; Lai, D.W.L.; Yip, H.M.; Chan, S.; Lai, S.; Chaudhury, H.; Scharlach, A.; Leeson, G. Sense of Community Mediating Between Age-Friendly Characteristics and Life Satisfaction of Community-Dwelling Older Adults. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, R.; Moses, W.; Jean, W. Perceptions of neighborhood environment, sense of community, and self-rated health: An age-friendly city project in Hong Kong. J. Urban Health 2018, 96, 276–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menec, V.H.; Nowicki, S. Examining the relationship between communities’ ‘age-friendliness’ and life satisfaction and self-perceived health in rural Manitoba, Canada. Rural. Remote Health 2014, 14, 2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.J. Understanding Aging in Place: Home and Community Features, Perceived Age-Friendliness of Community, and Intention Toward Aging in Place. Gerontologist 2022, 62, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, C.T.; Lim, X.J.; Supramaniam, P.; Chew, C.-C.; Ding, L.-M.; Rajan, P. Perceived Gap of Age-Friendliness among Community-Dwelling Older Adults: Findings from Malaysia, a Middle-Income Country. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buffel, T.; McGarry, P.; Phillipson, C.; De Donder, L.; Dury, S.; De Witte, N.; Smetcoren, A.-S.; Verté, D. Developing age-friendly cities: Case studies from Brussels and Manchester and implications for policy and practice. J. Aging Soc. Policy 2014, 26, 52–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziganshina, L.E.; Yudina, E.V.; Talipova, L.I.; Sharafutdinova, G.N.; Khairullin, R.N. Smart and Age-Friendly Cities in Russia: An Exploratory Study of Attitudes, Perceptions, Quality of Life and Health Information Needs. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiraphat, S.; Buntup, D.; Munisamy, M.; Nguyen, T.H.; Yuasa, M.; Nyein Aung, M.; Myint, A.H. Age-Friendly Environments in ASEAN Plus Three: Case Studies from Japan, Malaysia, Myanmar, Vietnam, and Thailand. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molina-Martínez, M.Á.; Marsillas, S.; Sánchez-Román, M.; del Barrio, E. Friendly Residential Environments and Subjective Well-Being in Older People with and without Help Needs. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Info Package: Mastering Depression in Primary Care, Version 2.2; Regional Office for Europe, Psychiatric Research Unit: Frederiksborg, Denmark, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Monachesi, P. Age Friendly Characteristics and Sense of Community of an Italian City: The Case of Macerata. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Barrio, E.; Pinzón, S.; Marsillas, S.; Garrido, F. Physical Environment vs. Social Environment: What Factors of Age-Friendliness Predict Subjective Well-Being in Men and Women? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, J.L.; Vaz, C.T.; Pinheiro, L.C.; Braga, L.; Moreira, B.; Oliveira, C.; Lima-Costa, M. The relationship between loneliness and healthy aging indicators in Brazil (ELSI-Brazil) and England (ELSA): Sex differences. Public Health 2023, 216, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camarinha-Matos, L.M.; Rosas, J.; Oliveira, A.I.; Ferrada, F. Care Services Ecosystem for Ambient Assisted Living. Enterp. Inf. Syst. 2015, 9, 607–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousquet, J.; Illario, M.; Farrell, J.; Batey, N.; Carriazo, A.; Malva, J.; Hajjam, J.; Colgan, E.; Guldemond, N.; Perälä-Heape, M.; et al. The Reference Site Collaborative Network of the European Innovation Partnership on Active and Healthy Ageing. Transl. Med. UniSa 2019, 19, 66–81. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Illario, M.; De Luca, V.; Onorato, G.; Tramontano, G.; Carriazo, A.M.; Roller-Wirnsberger, R.E.; Apostolo, J.; Eklund, P.; Goswami, N.; Iaccarino, G.; et al. Interactions Between EIP on AHA Reference Sites and Action Groups to Foster Digital Innovation of Health and Care in European Regions. Clin. Interv. Aging 2022, 17, 343–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malva, J.O.; Amado, A.; Rodrigues, A.; Mota-Pinto, A.; Cardoso, A.F.; Teixeira, A.M.; Todo-Bom, A.; Devesa, A.; Ambrósio, A.F.; Cunha, A.L.; et al. The Quadruple Helix-Based Innovation Model of Reference Sites for Active and Healthy Ageing in Europe: The Ageing@Coimbra Case Study. Front. Med. 2018, 5, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Staalduinen, W.H.; Ganzarain, J.G.; Dantas, C.; Rodriguez, F.; Stiehr, K.; Schulze, J.; Fernandez-Rivera, C.; Kelly, P.; McGrory, J.; Pritchard, C.; et al. Learning to implement Smart Healthy Age-Friendly Environments. Transl. Med. UniSa 2020, 23, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dantas, C.; Louceiro, J.; Vieira, J.; van Staalduinen, W.; Zanutto, O.; Mackiewicz, K. SHAFE Mapping on Social Innovation Ecosystems. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 20, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surd, V.; Kassai, I.; Giurgiu, L. Romania disparities in regional development. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 19, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hapenciuc, C.-V.; Neamțu, D.-M.; Bejinaru, R. Comparative statistical analysis of existing differences in the regional development of Romania regarding the main socio-economic indicators. In Knowledge Management and Innovation: From Soft Stuff to Hard Stuff; SNSPA: Bucharest, Romania, 2016; pp. 560–574. [Google Scholar]

- Veres, V.; Benedek, J.; Török, I. Changes in the Regional Development of Romania (2000–2019), Measured with a Multidimensional PEESH Index. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibinceanu Onica, M.C.; Cristache, N.; Dobrea, R.C.; Florescu, M. Regional Development in Romania: Empirical Evidence Regarding the Factors for Measuring a Prosperous and Sustainable Economy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TAB. 1.03.2_RPL2021—1.3.2 Resident Population by Age Group, by Counties and Municipalities, Cities, Communications, on 1 December 2021. Available online: https://www.recensamantromania.ro/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/Tabel-1.03_1.3.1-si-1.03.2.xls (accessed on 19 August 2023). (In Romanian).

- OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. Romania: Country Health Profile 2021, State of Health in the EU; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Average Age, Median Age, Demographic Aging Index and Demographic Dependency Ratio of the Resident Population (Sexes, Age Groups)—Table 1.23_updated. Available online: https://www.recensamantromania.ro/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/1.23_actualizat.xlsx (accessed on 19 August 2023).

- Portrait of a Romanian Personality, Ana Aslan. Banca Națională a României. Available online: https://www.bnr.ro/Portrait-of-a-Romanian-Personality,-Ana-Aslan-17513-Mobile.aspx (accessed on 19 August 2023).

- Ivan, L.; Beu, D.; van Hoof, J. Smart and Age-Friendly Cities in Romania: An Overview of Public Policy and Practice. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamfir, M.; Ciobanu, I.; Zamfir, M.V. Vatra Luminoasă, age-friendly-study of intergenerational architecture in a Bucharest neighborhood. Smart Cities 2021, 9, 437–460. [Google Scholar]

- Duduciuc, A. Age-friendly Advertising: A Qualitative Research on the Romanian Silver Consumers. Rom. J. Commun. Public Relat. 2017, 19, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Law No. 17 of March 6, 2000 (**Republished**) On Social Assistance for the Elderly**). Available online: https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocument/196545 (accessed on 22 August 2023). (In Romanian).

- Law No. 16 of March 6, 2000 Regarding the Establishment, Organization and Functioning of the National Council of the Elderly. Available online: https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocumentAfis/21307 (accessed on 22 August 2023). (In Romanian).

- Decision No. 886 of October 5, 2000 for the Approval of the National Grid for the Assessment of the Needs of the Elderly. Available online: https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocumentAfis/24673 (accessed on 22 August 2023). (In Romanian).

- Decision No. 499 of April 7, 2004 Regarding the Establishment, Organization and Functioning of the Civic Dialogue ADVISORY Committees for the Problems of the Elderly, within the Prefectures. Available online: http://www.legex.ro/Hotararea-499-2004-44747.aspx (accessed on 22 August 2023). (In Romanian).

- Decision No. 1317 of October 27, 2005 Regarding the Support of Volunteer Activities in the Field of Home Care Services for the Elderly. Available online: https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocument/66007 (accessed on 22 August 2023).

- Decision No. 997/2009 on the Establishment, Organization and Operation of the National Committee for Population and Development. Available online: https://lege5.ro/Gratuit/gezdonzzgq/art-1-hotarare-997-2009?dp=gqydimzqg4ydc (accessed on 22 August 2023). (In Romanian).

- Social Assistance Law no. 292/2011. Available online: https://lege5.ro/Gratuit/gi4diobsha/sistemul-de-servicii-sociale-lege-292-2011?dp=gu4tinbrha4dg (accessed on 22 August 2023). (In Romanian).

- Decision No. 566 of July 15, 2015 (*Updated*) Regarding the Approval of the National Strategy for the Promotion of Active Aging and the Protection of the Elderly for the Period 2015–2020, the Operational Action Plan for the period 2016–2020, and the Mechanism for Their Integrated Monitoring and Evaluation *). Available online: https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocument/170600 (accessed on 22 August 2023). (In Romanian).

- Government Emergency Ordinance No. 196 of November 18, 2020 for the Amendment and Completion of Law No. 95/2006 on Health Reform. Available online: https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocumentAfis/233458 (accessed on 22 August 2023). (In Romanian).

- Decision No. 1492/2022 of December 14, 2022 for the Approval of the National Strategy on Long-Term Care and Active Aging for 2023–2030. Available online: https://mmuncii.ro/j33/images/Documente/Legislatie/HG_1492_2022.pdf (accessed on 22 August 2023). (In Romanian).

- National Strategy on Long-Term Care and Active Aging for 2023–2030. Available online: https://mmuncii.ro/j33/images/Documente/Legislatie/Anexa_HG_1492_2022.pdf (accessed on 22 August 2023). (In Romanian).

- Decision No. 1133 of September 14, 2022 Regarding the Approval of the Methodological Norms for the Implementation of the Provisions of the Government Emergency Ordinance No. 196/2020 for the Amendment and Completion of Law no. 95/2006 on Health Reform. Available online: https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocument/259367 (accessed on 22 August 2023). (In Romanian).

- Romania’s Sustainable Development Strategy 2030. Paideia. 2018. Available online: https://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/rom195029.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2023).

- Tesliuc, E.; Grigoraș, V.; Stanculescu, M. (Eds.) Background Study for the National Strategy on Social Inclusion and Poverty Reduction 2015–2020, Bucharest, 2018, ISBN 978-973-0-20534-3. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/290551467995789441/pdf/103191-WP-P147269-Box394856B-PUBLIC-Background-Study-EN.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2023).

- The National Strategy for the Promotion of Active Aging and the Protection of the Elderly for 2015–2020. Available online: https://epale.ec.europa.eu/ro/resource-centre/content/strategia-nationala-pentru-promovarea-imbatranirii-active-si-protectia (accessed on 19 August 2023). (In Romanian).

- Government Decision on the Approval of the National Health Strategy 2023–2030 and the Action Plan for the Period 2023–2030 in Order to Implement the National Health Strategy. Available online: https://www.ms.ro/ro/transparenta-decizionala/acte-normative-in-transparenta/hot%C4%83r%C3%A2re-a-guvernului-privind-aprobarea-strategiei-na%C8%9Bionale-de-s%C4%83n%C4%83tate-2023-2030-%C8%99i-a-planului-de-ac%C8%9Biuni-pentru-perioada-2023-2030-%C3%AEn-vederea-implement%C4%83rii-strategiei-na%C8%9Bionale-de-s%C4%83n%C4%83tate/ (accessed on 19 August 2023). (In Romanian).

- Decision on the Approval of the National Plan for Research, Development and Innovation 2022–2027. Available online: https://uefiscdi.gov.ro/resource-862401-hg-aprobare-pncdi-iv.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2023). (In Romanian)

- National Council of Retired and Elderly People’s Organizations. Available online: https://www.cnpv.ro/ (accessed on 22 August 2023).

- European Association for Directors and Providers of Long-Term Care Services for the Elderly. Available online: https://ede-eu-archive.ean.care/ (accessed on 22 August 2023).

- Association of Directors of Institutions for the Elderly (A.D.I.V.) from Romania. Available online: https://www.adivromania.ro/despre-noi (accessed on 22 August 2023). (In Romanian).

- SenioriNET Federation. Available online: https://seniorinet.ro/?lang=en (accessed on 22 August 2023).

- Ministry of Labor and Social Solidarity. List of Social Services Addressed to the Elderly, Models of Good Practices in Social Services in Romania Addressed to the Elderly. Available online: https://www.mmuncii.ro/j33/images/Documente/Anunturi/Exemple_bune_practici_122022.pdf (accessed on 22 August 2023). (In Romanian)

- The European Innovation Partnership on Active and Healthy Ageing (EIP on AHA). Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/eip-aha (accessed on 22 August 2023).

- Humana Association—Out of Love for Our Grandparents. Available online: http://www.carecluj.ro/ (accessed on 22 August 2023). (In Romanian).

- HABITAS Association. Available online: https://www.habilitas.ro/ (accessed on 22 August 2023). (In Romanian).

- Omenia National Federation. Available online: https://www.fn-omenia.ro (accessed on 22 August 2023). (In Romanian).

- AGE platform Europe—Toward a Society for All Ages. Available online: https://www.age-platform.eu/ (accessed on 22 August 2023).

- EURAHL—European Coalition for Active and Healthy Living. Available online: https://www.euregha.net/partnerships/eurahl/ (accessed on 22 August 2023).

- Aging Well in the Digital World. Available online: http://www.aal-europe.eu/ (accessed on 22 August 2023).

- Older Adults Co-Creating a Sustainable Age-Friendly City. Available online: https://www.era-learn.eu/network-information/networks/enutc/1st-enutc-call-2021/older-adults-co-creating-a-sustainable-age-friendly-city (accessed on 22 August 2023). (In Romanian).

- GEAC. Available online: https://geac.ro/ (accessed on 22 August 2023). (In Romanian).

- SNSPA. Available online: https://snspa.ro/en/ (accessed on 22 August 2023).

- DigitalScouts. Available online: https://digitalscouts.eu/ (accessed on 22 August 2023).

- NOTRE—Novel Methods Improving Production Innovation Potential with Examples of Senior Care-Related Solutions. Available online: https://www.interregeurope.eu/notre (accessed on 22 August 2023).

- CA19136—International Interdisciplinary Network on Smart Healthy Age-Friendly Environments (NET4AGE-FRIENDLY). Available online: https://www.cost.eu/actions/CA19136/ (accessed on 22 August 2023).

- CA19121—Network on Privacy-Aware Audio- and Video-Based Applications for Active and Assisted Living (GoodBrother). Available online: https://www.cost.eu/actions/CA19121/ (accessed on 22 August 2023).

- Goodbrother—Network on Privacy-Aware Audio- and Video-Based Applications for Active and Assisted Living COST action 19121. Available online: https://goodbrother.eu/ (accessed on 22 August 2023).

- Regional Operational Program 2021–2027 Central Region—Romania October 2021 Version. Available online: https://mfe.gov.ro/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/2b61c7d53c06121331ea9fb5dfc8516a.pdf (accessed on 22 August 2023). (In Romanian)

- Applicant’s Guide PNRR/2023/C13/MMSS/I4. Day Care and Recovery Centers for the Elderly under the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (PNRR), Component 13—Social Reforms, Investment I4 Creation of a Network of Day Care and Recovery Centers for the Elderly; Public Selection of Competitive Projects—Guide to Public Consultation. Available online: https://mmuncii.ro/j33/index.php/ro/transparenta/anunturi/6887-20230323-pnrr-2023-c13-mmss-i4-ghid-consultare-publica (accessed on 22 August 2023). (In Romanian).

- Inclusion and Social Dignity. Available online: https://www.fonduri-structurale.ro/program-operational/35/incluziune-si-demnitate-sociala (accessed on 22 August 2023). (In Romanian).

- WHO. Active Ageing: A Policy Framework; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/67215/WH0?sequence=1 (accessed on 22 August 2023).

- Jeste, D.V.; Blazer, D.G., 2nd; Buckwalter, K.C.; Cassidy, K.-L.K.; Fishman, L.; Gwyther, L.P.; Levin, S.M.; Phillipson, C.; Rao, R.R.; Schmeding, E.; et al. Age-Friendly Communities Initiative: Public Health Approach to Promoting Successful Aging. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2016, 24, 1158–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portegijs, E.; Lee, C.; Zhu, X. Activity-friendly environments for active aging: The physical, social, and technology environments. Front. Public Health 2023, 10, 1080148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, M.; Gibney, S.; O’Callaghan, D.; Shannon, S. Age-Friendly Environments, Active Lives? Associations Between the Local Physical and Social Environment and Physical Activity Among Adults Aged 55 and Older in Ireland. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2020, 28, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| When? | What? |

|---|---|

| 2020 | Law no. 17/2000 regulates the social assistance of elderly [71] Law no. 16/2000 regulates the establishment, organization, and functioning of the National Council of the Elderly [72] H.G. no. 886/2000 regulates the national grid for assessing the needs of the elderly [73] |

| 2004 | H.G. no. 499/2004 regulates the establishment, organization, and functioning of the civic dialogue advisory committees for the problems of the elderly, within the prefectures [74] |

| 2005 | H.G. no. 1317/2005 regulates the voluntary activities in the field of home care services for the elderly [75] |

| 2009 | H.G. no. 997/2009 regulates the establishment, organization, and operation of the National Commission for Population and Development [76] |

| 2011 | Law 292/2011 on social assistance—introduce the reforms for the social assistance of people with disabilities, and for the social assistance of older people [77] |

| 2015 | H.G. no. 566/2015 regarding the approval of the National Strategy for the promotion of active aging and the protection of the elderly for the period 2015–2020 and the Strategic Action Plan for the period 2015–2020, with subsequent amendments and additions (brought up to 18 January 2018) H.G. for the approval of the National Strategy on long-term care and active aging for the period 2015–2020 [78] |

| 2020 | Governmental Ordinance no. 196/2020, for amending and supplementing Law no. 95/2006 on healthcare reform—the normative act regulates the possibility of providing remote medical services, through telemedicine, by all health professionals [79] |

| >2020 | H.G. for the approval of the National Strategy on long-term care and active aging for the period 2023–2030 [80,81] Government Decision no. 1.133/14 September 2022 Methodological norms for Telemedicine [82], Romania’s Sustainable Development Strategy 2030 [83] |

| Starting Date | Initiative | Coordinator | Expected Results |

|---|---|---|---|

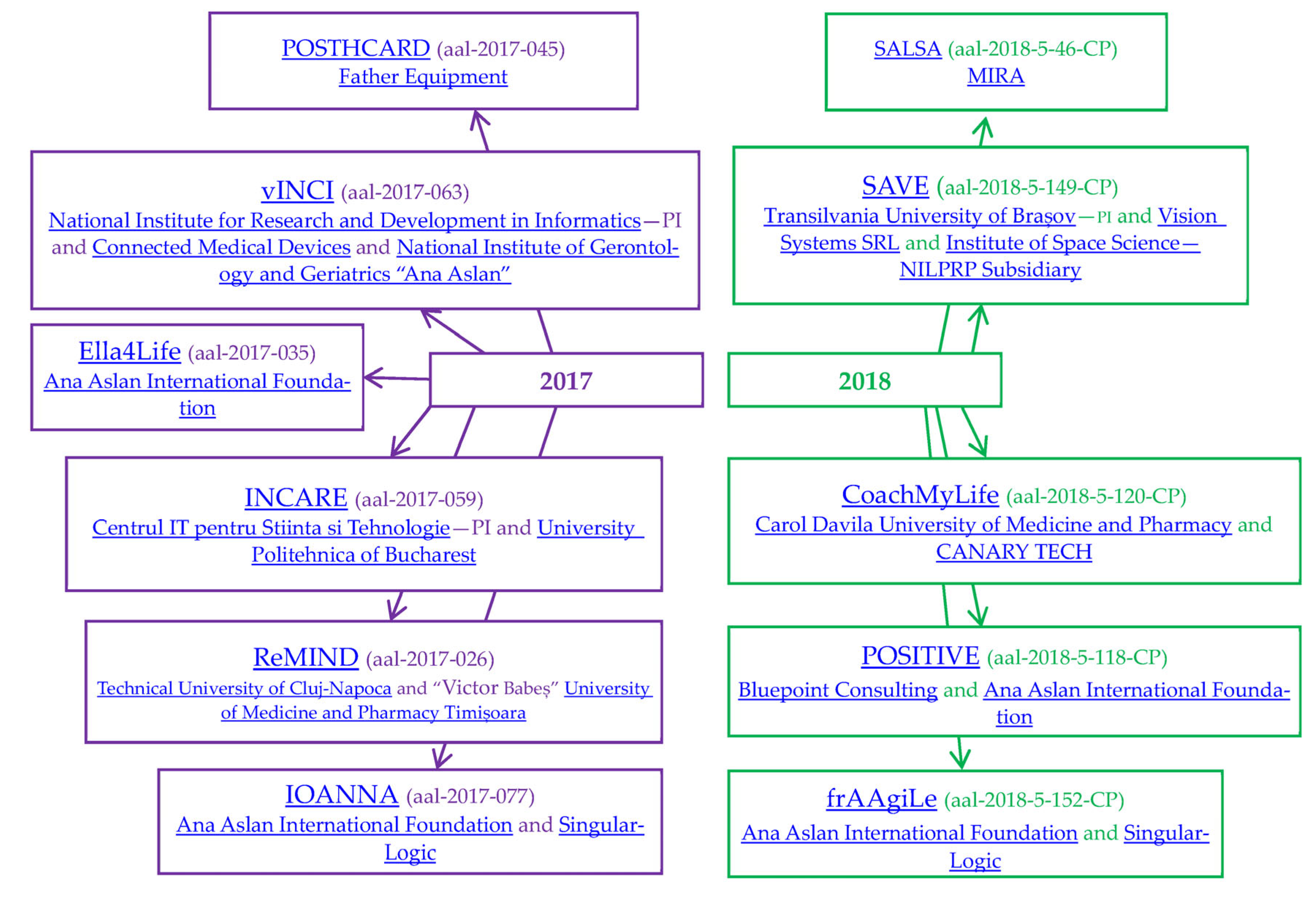

| 1 April 2018 | POSTHCARD | University Hospitals of Geneva, Switzerland | platform for caregivers of Alzheimer patients |

| 1 June 2018 | vINCI | National Institute for Research and Development in Informatics (ICI Bucharest), Romania | evidence-based IoT framework for non-intrusive monitoring of older adults |

| 1 June 2018 | Ella4Life | Virtual Assistant Virtask, The Netherlands | mobile solution that stimulates an active and healthy life |

| 1 October 2018 | INCARE | IT Center for Science and Technology, Romania | technology to support the independence of seniors and to optimize the required care amount |

| 1 October 2018 | ReMIND | Zora Robotics, Belgium | James nursing robot and a table to assist patients with dementia in stimulation of memory, meaningful and physical activity |

| 1 April 2018 | IOANNA | GeoImaging Ltd., Cyprus | online platform to assist seniors to be active citizens |

| February 2019 | SALSA | LIFEtool, Austria | an app-based solution that optionally includes (body) sensors to support physiotherapy |

| September 2019 | SAVE | Transilvania University of Brasov, Romania | solution dedicated to elderly to avoid psychosocial exclusion |

| 1 July 2019 | CoachMyLife | Pharmacie Principale, Switzerland | technology to assist daily living and to reduce/stabilize memory impairment |

| May 2019 | POSITIVE | Reall, Poland | quality of life of seniors platform—meaningfulness, happiness, and wellbeing |

| July 2019 | frAAgiLe | Ideable Solutions S.L., Spain | platform for detecting and preventing frailty and falls |

| February 2020 | DIANA | Cogvis Software and Consulting GmbH, Austria | artificial intelligence digital assistant to optimize the nursing process |

| April 2020 | iCan | GeoImaging Ltd., Cyprus | platform with services useful for the senior’s everyday life |

| April 2020 | H2HCare | Technical University of Cluj-Napoca, Romania | home care management with a social robot |

| 1 March 2021 | T4ME2 | Vienna University of Technology, Austria | new supportive, autonomy-promoting, smart toilet solutions for aging people |

| 1 May 2020 | ACESO | IT Center for Science and Technology, Romania | health and oral-care platform |

| April 2020 | ReMember-Me | Agecare (Cyprus) Ltd., Cyprus | a technical solution to detect and prevent cognitive decline early on |

| 1 May 2021 | WisdomOfAge | Digital Twin SRL, Romania | open digital platform to support elderly people to remain active and contribute toward society |

| 5 April 2021 | HEROES | The Care Hub SRL, Romania | recruitment platform with engagement of older people in recruiting activities |

| 1 April 2021 | SI4SI | DS TECH, Italy | technical solution for seniors—caregiver and health practitioner interaction |

| April 2021 | ORASTAR | MEDICA, Denmark | ambient assisted living technology to support toothbrushing adherence in elderly with cognitive impairments |

| 1 April 2021 | SmartSE | Life Science Innovation North Denmark, Denmark | European-wide digital matchmaking tool to encourage senior entrepreneurship |

| 1 March 2021 | FIND-a-PAL | Społeczna Akademia Nauk, SAN, Poland | platform to prevent social and digital isolation of older people |

| 1 March 2021 | SI-FOOtWORK | Technical University of Denmark, Denmark | solution dedicated to older workers to assist them to prevent, mitigate, and correct risk behaviors when lifting |

| n.a. | SGH | e-Point, Belgium | immersive spaces as tool to reduce the progression of dementia |

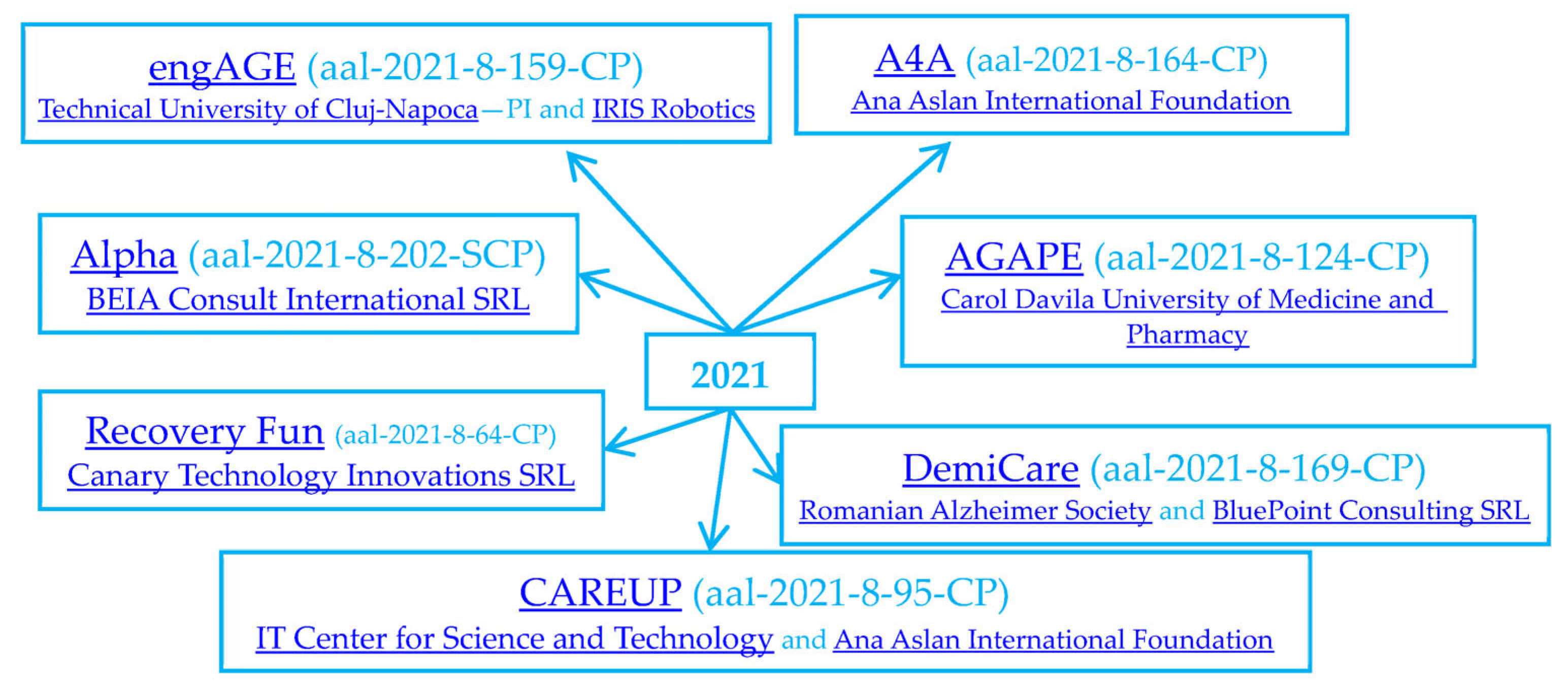

| 1 December 2021 | engAGE | Technical University of Cluj-Napoca, Romania | technical solution to combat or slow down cognitive decline progression in patients with mild cognitive impairment |

| 1 April 2022 | Alpha | Wageningen University, The Netherlands | tool to detect deficiencies in nutrients and amino acids in older persons with plant-based diet |

| 1 January 2022 | Recovery Fun | IRCCS INRCA, Italy | VR-based tele-rehabilitation platform for seniors |

| 1 January 2022 | A4A | Anyware Solutions ApS, Denmark | digital solutions to monitor older adults living alone |

| n.a. | AGAPE | Medea S.R.L., Italy | technology platform enabling active and healthy lifestyle services |

| 1 February 2022 | DemiCare | AIT Austrian Institute of Technology, Austria | personalized and data-driven support for informal caregivers of persons with dementia |

| 1 May 2022 | CAREUP | ECLEXYS Sagl, Switzerland | integrated platform to empower older adults to take care of their own health |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rotaru, F.; Matei, A.; Bolboacă, S.D.; Cordoș, A.A.; Bulboacă, A.E.; Muntean, C. Age-Inclusive Healthcare Sustainability: Romania’s Regulatory and Initiatives Landscape in the European Union Context. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1827. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16051827

Rotaru F, Matei A, Bolboacă SD, Cordoș AA, Bulboacă AE, Muntean C. Age-Inclusive Healthcare Sustainability: Romania’s Regulatory and Initiatives Landscape in the European Union Context. Sustainability. 2024; 16(5):1827. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16051827

Chicago/Turabian StyleRotaru, Flaviana, Andreea Matei, Sorana D. Bolboacă, Ariana Anamaria Cordoș, Adriana Elena Bulboacă, and Călin Muntean. 2024. "Age-Inclusive Healthcare Sustainability: Romania’s Regulatory and Initiatives Landscape in the European Union Context" Sustainability 16, no. 5: 1827. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16051827

APA StyleRotaru, F., Matei, A., Bolboacă, S. D., Cordoș, A. A., Bulboacă, A. E., & Muntean, C. (2024). Age-Inclusive Healthcare Sustainability: Romania’s Regulatory and Initiatives Landscape in the European Union Context. Sustainability, 16(5), 1827. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16051827