Cross-Border E-Commerce and Urban Entrepreneurial Vitality—A Quasi-Natural Experiment Evidence from China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Research on the Effect of Cross-Border E-Commerce

2.2. Research on the Influencing Factors of Entrepreneurship

2.3. Research on the Intersection between Cross-Border E-Commerce and Entrepreneurship

3. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypothesis

3.1. The Impact of CECPA on Entrepreneurial Vitality in Chinese Cities

3.2. The Mechanism of CECPA Affecting Urban Entrepreneurial Vitality

4. Methods, Variable and Data

4.1. Methods Selection

4.1.1. Benchmark Regression Model

4.1.2. Dynamic Model

4.1.3. Mediation Mechanism Test Model

4.1.4. Spatial Spillover Effects Test Model

4.2. Variable Selection

4.2.1. Explained Variable

4.2.2. Core Explanatory Variable

4.2.3. Mechanism Variables

- (1)

- Business Environment

- (2)

- Industrial Synergy Agglomeration

- (3)

- Market Consumer Demand

4.2.4. Control Variable

4.3. Data Declaration

5. Empirical Results

5.1. Benchmark Regression Results

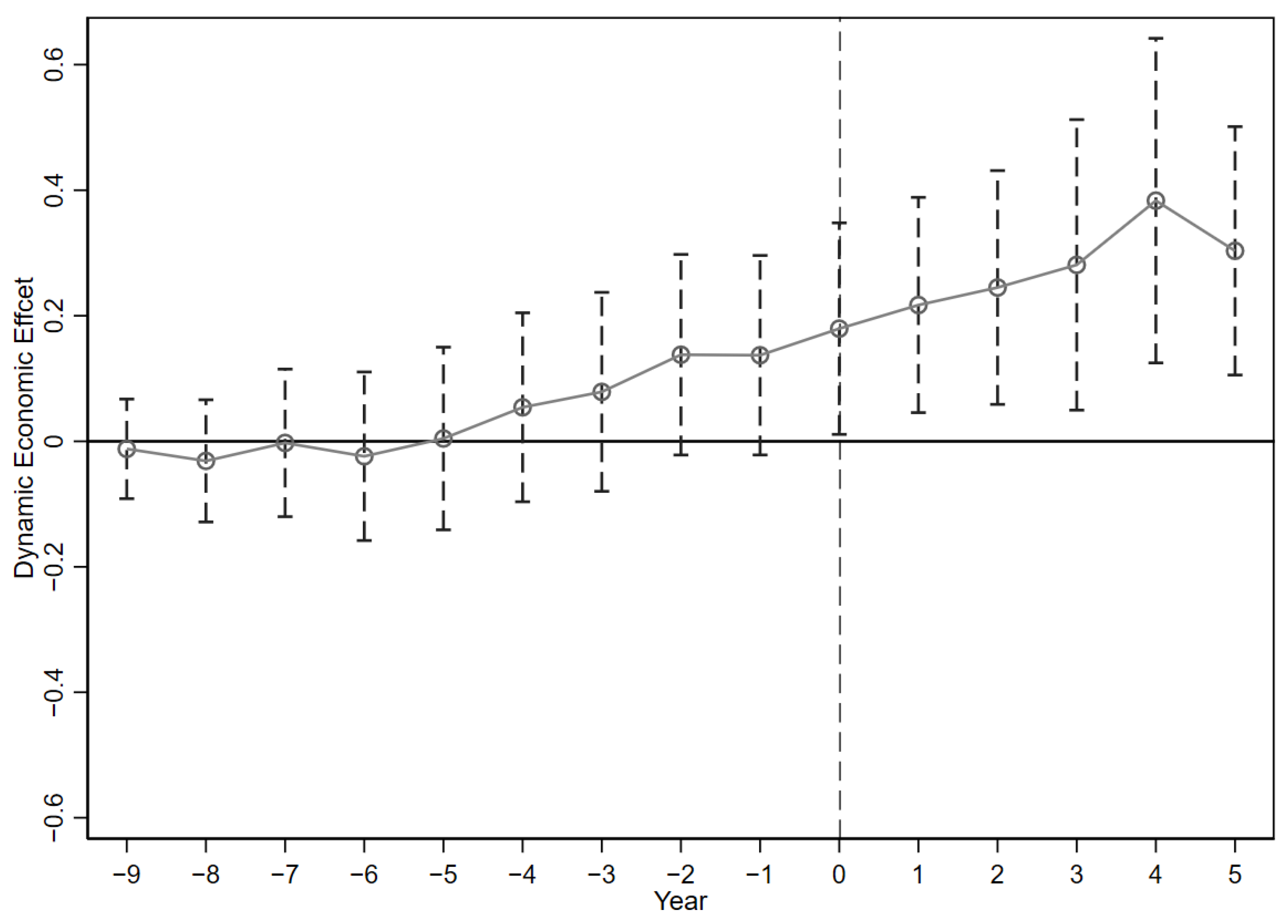

5.2. Parallel Trend Test

5.3. Robustness Test

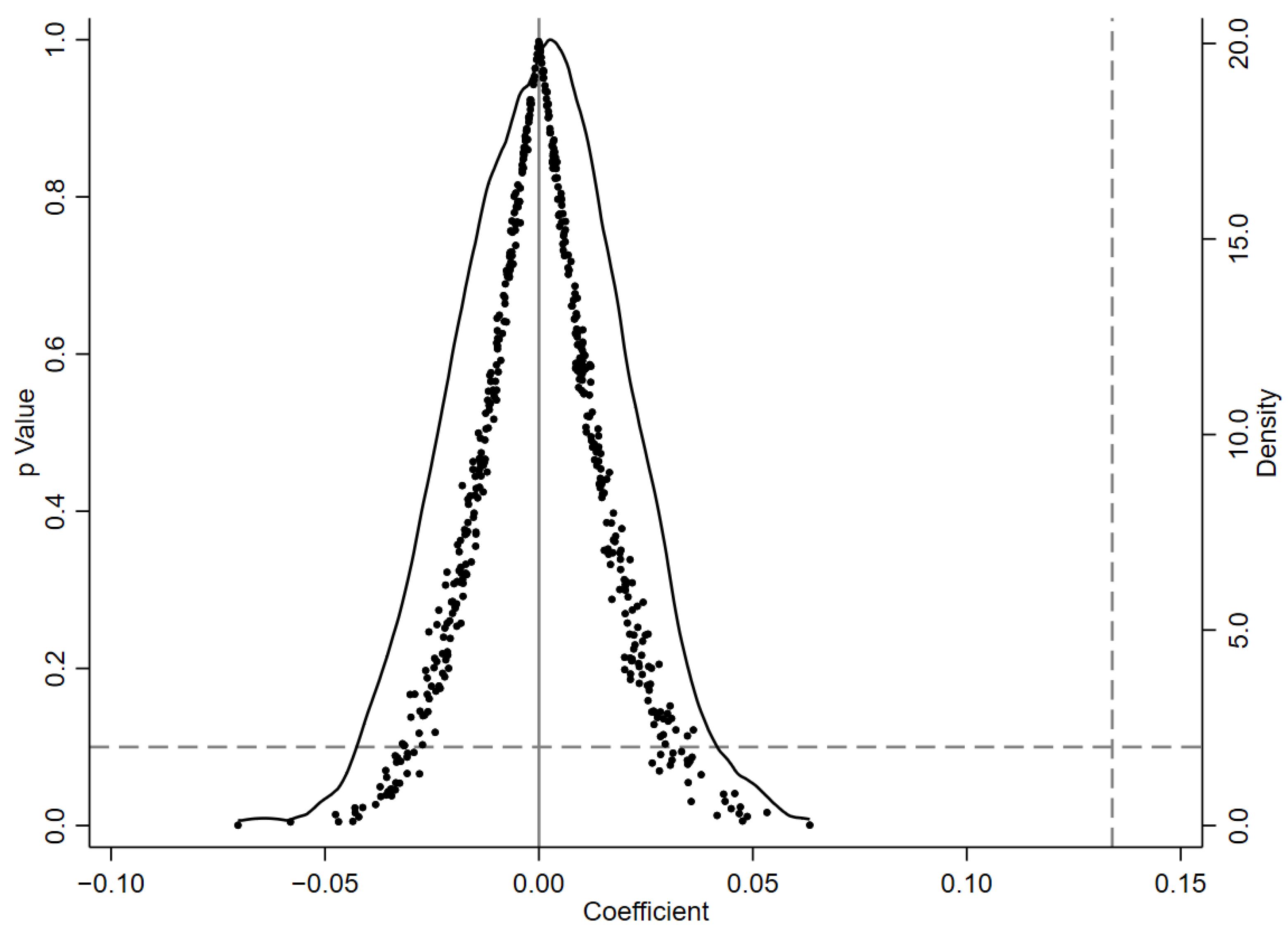

5.3.1. Placebo Test

5.3.2. PSM-DID Test

5.3.3. Endogeneity Analysis

5.3.4. Recalculation of Key Variables

5.3.5. Eliminating the Interference of Other Policies

5.4. Heterogeneity Analysis

5.4.1. Regional Heterogeneity

5.4.2. Urban Scale Heterogeneity

5.4.3. Urban Innovation Level Heterogeneity

5.4.4. Heterogeneity in the Scale of Registered New Enterprises

5.4.5. Heterogeneity in Industry Types

6. Further Discussion: Impact Mechanism and Spatial Spillover Effects

6.1. Mechanism: Optimizing the Business Environment

6.2. Mechanism: Industrial Synergy Agglomeration Effect

6.3. Mechanism: The Expansion of Market Consumer Demand

6.4. Spatial Spillover Effects

7. Conclusions and Recommendations

7.1. Conclusions

- (1)

- The pilot policies of CECPA significantly stimulate entrepreneurial vitality of cities. Compared to nonpilot cities, the number of newly registered enterprises in pilot areas increased by approximately 13.3%. This conclusion is still valid after conducting robustness tests such as parallel trends analysis, placebo tests, and endogeneity tests, thereby validating Hypothesis 1. Furthermore, cross-border e-commerce has also facilitated sustainable entrepreneurship, primarily by promoting entrepreneurial development in underdeveloped regions such as Western China, small and medium-sized cities, and cities with lower levels of innovation. It also promotes entrepreneurial activities among small and microenterprises, providing them with equal opportunities to compete with large enterprises. Additionally, cross-border e-commerce exhibits strong entrepreneurial vitality in the service industry.

- (2)

- The mechanisms used to promote the entrepreneurial vitality of the city can be categorized into three aspects: optimizing the business environment, promoting industrial agglomeration and synergy, and expanding the market scale. Firstly, the sustainable development of entrepreneurial cannot be achieved without a sound business environment. The pilot policy of CECPA can enhance the urban business environment by improving government efficiency, promoting privatization, opening up to the outside world, digitization, digital financial development, and legal institutionalization. This, in turn, reduces transaction costs associated with entrepreneurship and enhances entrepreneurial vitality, thus validating Hypothesis 2. Secondly, the CECPA promotes industrial agglomeration, particularly in manufacturing and productive service industries. By increasing the linkages between upstream and downstream industries and leveraging the agglomeration, sharing, and spillover effects of entrepreneurial resources, the zones have an impact on entrepreneurial activities, which supports Hypothesis 3. Lastly, the CECPA expands market boundaries through digital platforms, providing potential entrepreneurs with more opportunities, which validates Hypothesis 4.

- (3)

- Through the analysis of spatial spillover effects, it is found that the CECPA not only enhances local entrepreneurial vitality but also has a positive impact on the entrepreneurial vitality of geographically proximate or economically similar cities, demonstrating significant radiation effects. This conclusion indicates that the CECPA can promote regional coordinated development and is of great significance to sustainable development. It also represents a further extension of the research conducted by Qin and Xie [26].

7.2. Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Available online: http://dzsws.mofcom.gov.cn/article/ztxx/ndbg/202306/20230603415404.shtml (accessed on 28 September 2023).

- Available online: http://www.cnipr.com/sj/zx/202312/t20231227_253493.html (accessed on 1 February 2024).

- Duan, C.; Kotey, B.; Sandhu, K. The Effects of Cross-Border E-Commerce Platforms on Transnational Digital Entrepreneurship: Case Studies in the Chinese Immigrant Community. J. Glob. Inf. Manag. 2011, 30, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Lee, S. The Effect of Cross-Border E-Commerce on China’s International Trade: An Empirical Study Based on Transaction Cost Analysis. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Hu, Z. The effect of cross-border E-commerce on the portfolio of export risks facing Chinese firms. Fin. Trade Econ. 2022, 43, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Gu, C. The Impact of Cross-border E-commerce on Enterprise Participation in Global Value Chains: Empirical Evidence Based on Micro Data. Stat. Res. 2022, 39, 72–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carballo, J.; Rodriguez Chatruc, M.; Salas Santa, C.; Volpe Martincus, C. Online business platforms and international trade. J. Int. Econ. 2022, 137, 103599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, L.; Liu, Z. Cross-border E-commerce and producer services agglomeration. J. World Econ. 2023, 46, 63–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, J.; Yan, Z. Cross-border E-commerce Comprehensive Pilot Areas and Regional Coordinated Development: Window Radiation or Siphon Effect. J. Financ. Econ. 2023, 49, 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Song, Y. Cross-border E-commerce Reform and Wage Income: A New Open Perspective. J. Financ. Econ. 2022, 48, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Q.; Ji, Y. How does Cross-border E-commerce affect Enterprise Labor Employment: Based on the Quasi-natural Experiment of Cross-border E-commerce Comprehensive Pilot Area. Ind. Econ. Res. 2023, 1, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djankov, S.; Qian, Y.; Roland, G.; Zhuravskaya, E. Who Are China’s Entrepreneurs? Am Econ. Rev. 2006, 96, 348–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaFave, D.; Thomas, D. Farms, Families, and Markets: New Evidence on Completeness of Markets in Agricultural Settings. Econometrica 2016, 84, 1917–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, M.; Bobba, M. Liquidity, Risk, and Occupational Choices. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2013, 80, 491–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Tao, Z. Determinants of entrepreneurial activities in China. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, B.; Zhao, Y.; Elahi, E.; Wan, A. Does the business environment improve the competitiveness of start-ups? The moderating effect of cross-border ability and the mediating effect of entrepreneurship. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 1173–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, J.; Sun, W. Institutional Innovation, Business Environment and Entrepreneurial Vitality: Evidence from the China Pilot Free Trade Zone. J. Quant. Tech Econ. 2023, 40, 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhang, X.; Dong, X.; Yan, Q.; Zeng, L.; Wang, Z. The impact of smart cities on entrepreneurial activity: Evidence from a quasi-natural experiment in China. Resour. Policy 2023, 81, 103333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, S.; Mcdowell, W.; Ribeiro-Soriano, D.E.; Rodríguez-García, M. The role of innovation and knowledge for entrepreneurship and regional development. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2021, 33, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afawubo, K.; Noglo, Y.A. ICT and entrepreneurship: A comparative analysis of developing, emerging and developed countries. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2022, 175, 121312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troise, C.; Ben-Hafaïedh, C.; Tani, M.; Yablonsky, S.A. Guest editorial: New technologies and entrepreneurship: Exploring entrepreneurial behavior in the digital transformation era. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2022, 28, 1129–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niebel, T. ICT and economic growth—Comparing developing, emerging and developed countries. World Dev. 2018, 104, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Sawang, S.; Yang, H.S. How is entrepreneurial marketing shaped by E-commerce technology: A case study of Chinese pure-play e-retailers. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2023. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elia, G.; Margherita, A.; Passiante, G. Digital entrepreneurship ecosystem: How digital technologies and collective intelligence are reshaping the entrepreneurial process. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 150, 119791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabbous, A.; Barakat, K.A.; Kraus, S. The impact of digitalization on entrepreneurial activity and sustainable competitiveness: A panel data analysis. Technol. Soc. 2023, 73, 102224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, F.; Xie, K.; Wang, J. Effects of E-commerce Development on Entrepreneurship: Evidence from Microdata of Households. Financ. Trade Econ. 2023, 44, 154–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Wang, S.; Jiang, H. Would Trade Liberalization Promote Entrepreneurship? Financ. Trade Econ. 2020, 41, 111–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Fu, X.; Li, Y. SME participation in cross-border e-commerce as an entry mode to foreign markets: A driver of innovation or not? Electron. Commer. Res. 2023, 23, 2327–2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreneche García, A. Analyzing the determinants of entrepreneurship in European cities. Small Bus. Econ. Group 2014, 42, 77–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melitz, M.J. The Impact of Trade on Intra-Industry Reallocations and Aggregate Industry Productivity. Econometrica 2003, 71, 1695–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manjon, M.; Aouni, Z.; Crutzen, N. Green and digital entrepreneurship in smart cities. Ann. Reg. Sci. 2022, 68, 429–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; van Gorp, D.; Kievit, H. Digital technology and national entrepreneurship: An ecosystem perspective. J. Technol. Transf. 2023, 48, 1077–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamine, W.; Fayolle, A.; Jack, S.; Audretsch, D. Impact of digital technologies on entrepreneurship: Taking stock and looking forward. Technovation 2023, 126, 102823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bah, E.H.; Fang, L. Impact of the business environment on output and productivity in Africa. J. Dev. Econ. 2015, 114, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbano, D.; Audretsch, D.; Aparicio, S.; Noguera, M. Does entrepreneurial activity matter for economic growth in developing countries? The role of the institutional environment. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2020, 16, 1065–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, M. The response of small ONTARIO businesses to a changing business environment. J. Small Bus. Entrep. 1995, 12, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Kelley, D.J.; Levie, J. Market-driven entrepreneurship and institutions. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 113, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaeser, E.L.; Kerr, W.R. Local Industrial Conditions and Entrepreneurship: How Much of the Spatial Distribution Can We Explain? J. Econ. Manag. Strategy 2009, 18, 623–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, M.; Porter, M.E.; Stern, S. Clusters and entrepreneurship. J. Econ. Geogr. 2010, 10, 495–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciriello, R.F.; Richter, A.; Schwabe, G. Digital Innovation. Bus. Inf. Syst. Eng. 2018, 60, 563–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, F.; Gao, J.; Wang, L.; Cai, Y. Co-location of manufacturing and producer services in Nanjing, China. Cities 2017, 63, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audretsch, D.B.; Heger, D.; Veith, T. Infrastructure and entrepreneurship. Small Bus. Econ. Group 2015, 44, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Zhang, Z.; Liang, S. Digital Economy, Entrepreneurship, and High-Quality Economic Development: Empirical Evidence from Urban China. J. Manag. 2020, 36, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, M.; Mullainathan, D.S. How Much Should We Trust Differences-in-Differences Estimates? Q. J. Econ. 2004, 119, 249–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Lin, W.; Wei, W. How does digital technology promote carbon emission reduction? Empirical evidence based on e-commerce pilot city policy in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 325, 116524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, M.; Leonard, D.; Sing, T.F. Spatial-difference-in-differences models for impact of new mass rapid transit line on private housing values. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2017, 67, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Liu, W.; Zhang, D. Exploring the role of co-agglomeration of manufacturing and producer services on carbon productivity: An empirical study of 282 cities in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 399, 136674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, C.D. The, Market as a Factor in the Localization of Industry in the United States. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 1954, 44, 315–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Deng, M.; Li, H. How does e-commerce city pilot improve green total factor productivity? Evidence from 230 cities in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 289, 112520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, M.; Liao, L.; Shi, Y. Aging Populations and Regional Entrepreneurship: A Study Using Entrepreneurship Data from Qixinbao. J. Financ. Res. 2022, 2, 80–97. Available online: www.jryj.org.cn/CN/Y2022/V500/I2/80 (accessed on 28 September 2023).

| Variables | Meaning | Definition | Mean | Sd |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enterp | Entrepreneurial vitality | Number of new startups | 9.14 | 1.06 |

| DID | Cross-border E-commerce Comprehensive pilot area | Approved as a comprehensive test area is 1, otherwise it is 0 | 0.07 | 0.25 |

| Rgdp | Economic development | Log of GDP per capita | 10.67 | 0.59 |

| FDI | Opening degree | Foreign investment/GDP | 0.016 | 0.017 |

| Tech | Technology expenditure | Technology expenditure /government expenditure | 0.017 | 0.018 |

| Finance | Financial development | Balance of RMB loans of financial institutions at the end of the year | 0.83 | 0.63 |

| Upgrade | Industrial structure | Index of industrial structure rationalization | 2.29 | 0.15 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enterp | Enterp | Enterp | Enterp | |

| DID | 1.851 *** | 0.222 *** | 0.099 *** | 0.133 *** |

| (0.117) | (0.051) | (0.037) | (0.031) | |

| Rgdp | 0.219 *** | 0.496 *** | ||

| (0.073) | (0.068) | |||

| FDI | 0.378 | 2.569 *** | ||

| (1.586) | (0.926) | |||

| Tech | 4.807 ** | 3.985 *** | ||

| (2.356) | (1.168) | |||

| Finance | 0.152 *** | −0.015 | ||

| (0.049) | (0.020) | |||

| Upgrade | 0.325 | 0.215 * | ||

| (0.209) | (0.128) | |||

| Stud | 0.161 *** | 0.093 ** | ||

| (0.034) | (0.041) | |||

| Intnet | 0.614 *** | 0.161 *** | ||

| (0.048) | (0.041) | |||

| Urbanratio | −0.099 | 0.619 ** | ||

| (0.311) | (0.259) | |||

| _cons | 9.008 *** | 0.092 | 9.130 *** | 0.808 |

| (0.048) | (0.715) | (0.003) | (0.979) | |

| Fixed Effects | N | N | Y | Y |

| N | 3058 | 3058 | 3058 | 3058 |

| Adj-R2 | 0.196 | 0.753 | 0.932 | 0.944 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PSM-DID | IV1 | IV2 | |

| DID | 0.1000 *** | 0.3429 ** | 0.3815 *** |

| (0.038) | (2.3048) | (3.3176) | |

| _cons | 0.7037 | - | - |

| (1.179) | - | - | |

| Control Variables | Y | Y | Y |

| Fixed Effects | Y | Y | Y |

| N | 2649 | 3058 | 2420 |

| Adj-R2 | 0.912 | 0.746 | 0.759 |

| LM | - | 30.17 | 37.61 |

| F statistic | - | 258.7 | 394.5 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of New Entrepreneurial Enterprises per 100 People | Self-Employment Rate | Entrepreneurship Index | |

| DID | 0.3499 *** | 0.0465 ** | 0.1492 *** |

| (0.0931) | (0.0235) | (0.0165) | |

| _cons | −1.4031 | 0.1538 | 2.4126 *** |

| (1.0021) | (0.1726) | (0.2792) | |

| Control Variables | Y | Y | Y |

| Fixed Effects | Y | Y | Y |

| N | 3053 | 3047 | 3058 |

| Adj-R2 | 0.827 | 0.741 | 0.910 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enterp | Enterp | Enterp | Enterp | |

| DID | 0.1335 *** | 0.1331 *** | 0.1146 *** | 0.1303 *** |

| (0.0314) | (0.0316) | (0.0306) | (0.0313) | |

| d2015 | 0.2930 *** | |||

| (0.1023) | ||||

| did_smart | 0.0319 | |||

| (0.0451) | ||||

| did_bbc | 0.1148 *** | |||

| (0.0362) | ||||

| did_inno | 0.1641 *** | |||

| (0.0489) | ||||

| _cons | 0.7240 | 0.8444 | 0.8523 | 0.9095 |

| (0.9385) | (0.9754) | (0.9610) | (0.9767) | |

| Control Variables | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Fixed Effects | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| N | 3058 | 3058 | 3058 | 3058 |

| Adj-R2 | 0.751 | 0.944 | 0.945 | 0.945 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eastern Region | Central Region | Western Region | |

| DID | 0.0933 ** | 0.0568 | 0.1173 * |

| (0.0451) | (0.0481) | (0.0684) | |

| _cons | 0.5134 | −3.6106 ** | 0.5570 |

| (1.5746) | (1.4946) | (1.8845) | |

| Control variables | Y | Y | Y |

| Fixed effects | Y | Y | Y |

| N | 1099 | 1100 | 858 |

| Adj-R2 | 0.957 | 0.922 | 0.931 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Large Cities | Small and Medium-Sized Cities | High Level of Innovation | Low Level of Innovation | |

| DID | −0.0250 | 0.1072 *** | −0.0160 | 0.0917 ** |

| (0.0484) | (0.0371) | (0.0410) | (0.0454) | |

| _cons | 6.9611 *** | −0.9002 | 5.1690 ** | −0.7760 |

| (2.0513) | (1.0897) | (2.3763) | (1.1309) | |

| Control Variables | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Fixed Effects | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| N | 462 | 2596 | 626 | 2424 |

| Adj-R2 | 0.976 | 0.916 | 0.964 | 0.893 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| X ≤ 100000 | 10 < X ≤ 1000 | X > 1000 | |

| DID | 0.1552 ** | 0.3146 ** | 0.0695 * |

| (0.0718) | (0.1444) | (0.0369) | |

| _cons | −0.6738 | 12.1567 *** | 2.5492 *** |

| (1.7155) | (3.9597) | (0.7551) | |

| Control Variables | Y | Y | Y |

| Fixed Effects | Y | Y | Y |

| N | 3058 | 3058 | 3058 |

| Adj-R2 | 0.774 | 0.965 | 0.957 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agriculture | Manufc | Service | Prodservice | Nonproduserv | |

| DID | −0.0277 | 0.0069 | 0.2398 *** | 0.1079 *** | 0.1340 *** |

| (0.0596) | (0.0350) | (0.0374) | (0.0412) | (0.0392) | |

| _cons | 4.7335 *** | 5.9809 *** | 7.5856 *** | 3.6725 *** | 7.4525 *** |

| (1.1476) | (0.6609) | (0.6766) | (1.0063) | (0.6950) | |

| Control Variables | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Fixed Effects | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| N | 3058 | 3058 | 3058 | 3058 | 3058 |

| Adj-R2 | 0.820 | 0.925 | 0.935 | 0.935 | 0.925 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Business | Enterp | Government Efficiency | Nonstate-Owned Economy | Opening Degree | Digital Finance | Digitalization | Legal Environment | |

| DID | 0.005 ** | 0.095 *** | 0.007 * | −0.016 | 0.005 *** | 0.015 *** | 0.010 *** | 0.010 * |

| (0.003) | (0.028) | (0.004) | (0.010) | (0.002) | (0.006) | (0.003) | (0.005) | |

| Business | 3.572 *** | |||||||

| (0.513) | ||||||||

| _cons | −0.190 *** | 2.123 ** | −0.426 *** | −0.091 | 0.022 | −0.647 *** | 0.001 | 0.003 |

| (0.055) | (0.891) | (0.072) | (0.241) | (0.023) | (0.139) | (0.043) | (0.064) | |

| Control Variables | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Fixed Effects | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| N | 2780 | 2780 | 2780 | 2780 | 2780 | 2780 | 2780 | 2780 |

| Adj-R2 | 0.975 | 0.955 | 0.888 | 0.930 | 0.990 | 0.946 | 0.970 | 0.882 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coagg_New | Enterp | MCP | Enterp | |

| DID | 0.0713 *** | 0.1292 *** | 0.0620 *** | 0.1262 *** |

| (0.0196) | (0.0379) | (0.0235) | (0.0314) | |

| Coagg_new | 0.1235 ** | |||

| (0.0586) | ||||

| MCP | 0.1183 *** | |||

| (0.0439) | ||||

| _cons | 1.0738 ** | −0.1498 | 8.2069 *** | −0.1624 |

| (0.4888) | (1.1349) | (0.6109) | (1.1055) | |

| Control Variables | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Fixed Effects | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| N | 2647 | 2647 | 3058 | 3058 |

| Adj-R2 | 0.835 | 0.944 | 0.979 | 0.944 |

| Variables | (1) Economic Distance Matrix | (2) Spatial Adjacency Matrix | (3) Geographical Distance Matrix |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enterp | Enterp | Enterp | |

| DID | 0.0654 *** | 0.0909 *** | 0.0858 *** |

| (0.0238) | (0.0209) | (0.0188) | |

| W × DID | 0.1274 ** | 1.1214 *** | 0.2318 *** |

| (0.0593) | (0.3153) | (0.0780) | |

| ρ | 0.0674 * | 0.3879 *** | 0.8434 *** |

| (0.0375) | (0.0923) | (0.0260) | |

| Direct | 0.0674 *** | 0.0964 *** | 0.1127 *** |

| (0.0243) | (0.0215) | (0.0208) | |

| Indirect | 0.1429 ** | 1.9318 *** | 1.9743 *** |

| (0.0640) | (0.5794) | (0.5961) | |

| Total | 0.2103 *** | 2.0282 *** | 2.0870 *** |

| (0.0635) | (0.5817) | (0.6034) | |

| Control Variables | Y | Y | Y |

| Fixed Effects | Y | Y | Y |

| N | 3058 | 3058 | 3058 |

| Adj-R2 | 0.4223 | 0.4223 | 0.4223 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yuan, Q.; Ji, Y.; Zhang, W.; Lei, T. Cross-Border E-Commerce and Urban Entrepreneurial Vitality—A Quasi-Natural Experiment Evidence from China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1802. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16051802

Yuan Q, Ji Y, Zhang W, Lei T. Cross-Border E-Commerce and Urban Entrepreneurial Vitality—A Quasi-Natural Experiment Evidence from China. Sustainability. 2024; 16(5):1802. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16051802

Chicago/Turabian StyleYuan, Qigang, Yongsheng Ji, Wei Zhang, and Ting Lei. 2024. "Cross-Border E-Commerce and Urban Entrepreneurial Vitality—A Quasi-Natural Experiment Evidence from China" Sustainability 16, no. 5: 1802. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16051802

APA StyleYuan, Q., Ji, Y., Zhang, W., & Lei, T. (2024). Cross-Border E-Commerce and Urban Entrepreneurial Vitality—A Quasi-Natural Experiment Evidence from China. Sustainability, 16(5), 1802. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16051802