Research on the Effectiveness of Virtual Endorsers: A Study Based on the Match-Up Hypothesis and Source Credibility Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Foundation and Hypotheses

2.1. Virtual Endorsers

2.2. Match-Up Hypothesis

2.3. Source Credibility

2.4. Source Credibility as a Mediator of the Relationship between Endorser–Product Fit and Product Attitude

2.5. Moderating Effect of Product Type

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Collection Procedure

3.2. Measures

4. Data Analysis and Results

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

4.2. Data Analysis

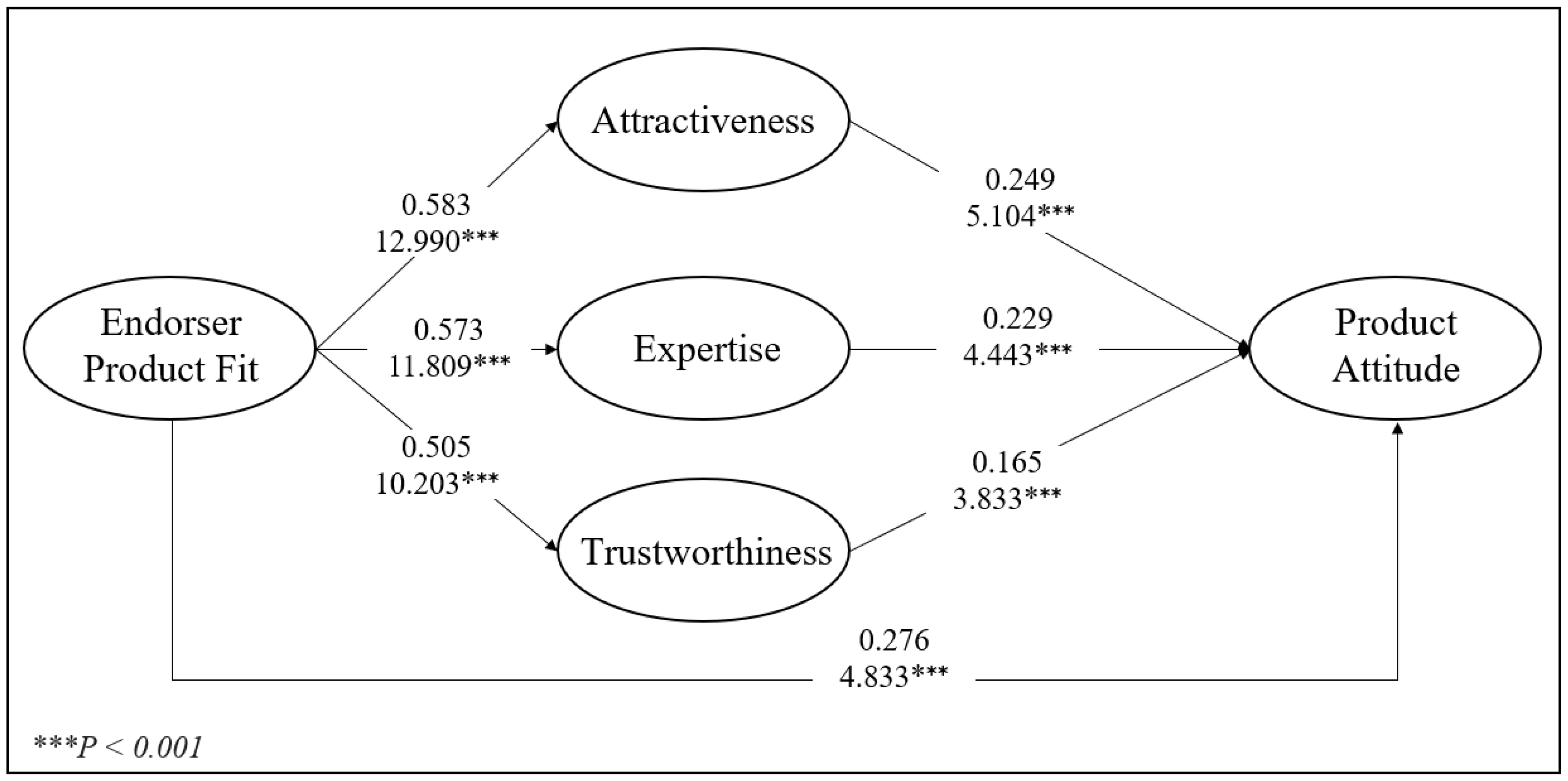

4.3. Mediating Effect of Source Credibility

4.4. Moderating Effect of Product Type

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Managerial Implications

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UN (2021) Sustainable Development Goals. Goal 12: Ensure Sustainable Consumption and Production Patterns, United Nations. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-consumption-production/ (accessed on 17 November 2023).

- Denoncourt, J. Companies and UN 2030 sustainable development goal 9 industry, innovation, and infrastructure. J. Corp. Law Stud. 2020, 20, 199–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosário, A.T.; Dias, J.C. The New Digital Economy and Sustainability: Challenges and Opportunities. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henninger, C.E.; Niinimäki, K.; Blazquez, M.; Jones, C. Sustainable Fashion Management; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2023; pp. 147–177. [Google Scholar]

- Appel, G.; Grewal, L.; Hadi, R.; Stephen, A.T. The Future of Social Media in Marketing. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 2020, 48, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franke, C.; Groeppel-Klein, A.; Müller, K. Consumers’ Responses to Virtual Influencers as Advertising Endorsers: Novel and Effective or Uncanny and Deceiving? J. Advert. 2022, 52, 523–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustakas, E.; Lamba, N.; Mahmoud, D.; Ranganathan, C. Blurring Lines between Fiction and Reality: Perspectives of Experts on Marketing Effectiveness of Virtual Influencers. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Cyber Security, Dublin, Ireland, 15–19 June 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Huang, J.; Li, Y. Examining the Effects of Authenticity Fit and Association Fit: A Digital Human Avatar Endorsement Model. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 71, 103230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wielki, J. Analysis of the Role of Digital Influencers and Their Impact on the Functioning of the Contemporary On-Line Pro-motional System and Its Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, E.S.; Bonetti, F. Digital Humans in Fashion: Will Consumers Interact? J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 60, 102430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, F.; Kozlenkova, I.V.; Wang, H.; Xie, T.; Palmatier, R.W. An Emerging Theory of Avatar Marketing. J. Market. 2022, 86, 67–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Chuenterawong, P.; Lee, H.; Chock, T.M. Anthropomorphism in CSR Endorsement: A Comparative Study on Humanlike vs. Cartoonlike Virtual Influencers’ Climate Change Messaging. J. Promot. Manag. 2023, 29, 705–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, R.; Luck, E.; Mathews, S.; Schuster, L. Creating Persuasive Environmental Communicators: Spokescharacters as Endorsers in Promoting Sustainable Behaviors. Sustainability 2023, 15, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohanian, R. Construction and Validation of a Scale to Measure Celebrity Endorsers’ Perceived Expertise, Trustworthiness, and Attractiveness. J. Advert. 1990, 19, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamins, M.A. An Investigation into the “Match-up” Hypothesis in Celebrity Advertising: When Beauty May Be Only Skin Deep. J. Advert. 1990, 19, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Till, B.D.; Busler, M. The Match-up Hypothesis: Physical Attractiveness, Expertise, and the Role of Fit on Brand Attitude, Purchase Intent and Brand Beliefs. J. Advert. 2000, 29, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schouten, A.P.; Janssen, L.; Verspaget, M. Celebrity vs. Influencer Endorsements in Advertising: The Role of Identification, Credibility, and Product-Endorser Fit; Leveraged Marketing Communications; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2021; pp. 208–231. [Google Scholar]

- Janssen, L.; Schouten, A.P.; Croes, E.A. Influencer Advertising on Instagram: Product-Influencer Fit and Number of Followers Affect Advertising Outcomes and Influencer Evaluations Via Credibility and Identification. Int. J. Advert. 2022, 41, 101–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaied, A.M.; Rached, K.S.B. The Congruence Effect between Celebrity and the Endorsed Product in Advertising. J. Market. Manag. 2017, 5, 27–44. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, V.L.; Fowler, K. Close Encounters of the AI Kind: Use of AI Influencers as Brand Endorsers. J. Advert. 2021, 50, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Veirman, M.; Cauberghe, V.; Hudders, L. Marketing through Instagram influencers: The impact of number of followers and product divergence on brand attitude. Int. J. Advert. 2017, 36, 798–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Territory Influence. Virtual Influencers and Their Social Media Appeal to Brands in the Metaverse. Available online: https://www.territory-influence.com/virtual-influencers-and-their-social-media-appeal-to-brands-in-the-meteverse/ (accessed on 16 September 2023).

- Robinson, B. Towards an Ontology and Ethics of Virtual Influencers. Australas. J. Inf. Syst. 2020, 24, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, E.; Lovegrove, R. Discordant storytelling, ‘honest fakery’, identity peddling: How uncanny CGI characters are jamming public relations and influencer practices. Public Relat. Inq. 2021, 10, 265–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, C.; Kiew, S.T.J.; Chen, T.; Lee, T.Y.M.; Ong, J.E.C.; Phua, Z. Authentically fake? How consumers respond to the influence of virtual influencers. J. Advert. 2022, 52, 540–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsenyan, J.; Mirowska, A. Almost human? A comparative case study on the social media presence of virtual influencers. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2021, 155, 102694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamins, M.A.; Gupta, K. Congruence between Spokesperson and Product Type: A Matchup Hypothesis Perspective. Psychol. Market. 1994, 11, 569–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J.; Na, J.H. Effects of Celebrity Athlete Endorsement on Attitude Towards the Product: The Role of Credibility, Attractiveness and the Concept of Congruence. Int. J. Sports Market. Sponsor. 2007, 8, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.W.; Jin, Y.J. Reverse Transfer Effect of Celebrity-Product Congruence on the Celebrity’s Perceived Credibility. J. Promot. Manag. 2015, 21, 666–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koernig, S.K.; Boyd, T.C. To Catch a Tiger or Let Him Go: The Match-Up Effect and Athlete Endorsers for Sport and Non-Sport Brands. Sport Mark. Q. 2009, 18, 25–37. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, A.S.; Roy, S.; Bailey, A.A. Exploring brand personality–celebrity endorser personality congruence in celebrity endorsements in the Indian context. Psychol. Mark. 2015, 32, 1158–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.J.; Lin, L.M. The Effects of Match-Ups on the Consumer Attitudes Toward Internet Celebrities and Their Live Streaming Contents in the Context of Product Endorsement. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 52, 101934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breves, P.L.; Liebers, N.; Abt, M.; Kunze, A. The Perceived Fit between Instagram Influencers and the Endorsed Brand: How Influencer–Brand Fit Affects Source Credibility and Persuasive Effectiveness. J. Advert. Res. 2019, 59, 440–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowling, N.A.; Beehr, T.A.; Johnson, A.L.; Semmer, N.K.; Hendricks, E.A.; Webster, H.A. Explaining potential antecedents of workplace social support: Reciprocity or attractiveness? J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2004, 9, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, W.J.; Lindzey, G.; Aronson, E. Handbook of social psychology. In Attitudes and Attitude Change; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 1985; pp. 233–346. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, P.; Augusto, M.; Matos, M. Antecedents and Outcomes of Digital Influencer Endorsement: An Exploratory Study. Psychol. Mark. 2019, 36, 1267–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Park, M. Virtual influencers’ attractiveness effect on purchase intention: A moderated mediation model of the Product–Endorser fit with the brand. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2023, 143, 107703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, C.; Yuan, S. Influencer marketing: How message value and credibility affect consumer trust of branded content on social media. J. Interact. Advert 2019, 19, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rungruangjit, W. What Drives Taobao Live Streaming Commerce? The Role of Parasocial Relationships, Congruence and Source Credibility in Chinese Consumers’ Purchase Intentions. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siemens, J.C.; Smith, S.; Fisher, D.; Jensen, T.D. Product expertise versus professional expertise: Congruency between an endorser’s chosen profession and the endorsed product. J. Target. Meas. Anal. Mark. 2008, 16, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Lynch, J.G., Jr.; Chen, Q. Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and Truths about Mediation Analysis. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrook, M.B.; Hirschman, E.C. The Experiential Aspects of Consumption: Consumer Fantasies, Feelings, and Fun. J. Consum. Res. 1982, 9, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar, R.; Wertenbroch, K. Consumer Choice between Hedonic and Utilitarian Goods. J. Mark. Res. 2000, 37, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adaval, R. Sometimes It Just Feels Right: The Differential Weighting of Affect-Consistent and Affect-Inconsistent Product Information. J. Consum. Res. 2001, 28, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voss, K.E.; Spangenberg, E.R.; Grohmann, B. Measuring the Hedonic and Utilitarian Dimensions of Consumer Attitude. J. Mark. Res. 2003, 40, 310–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sela, A.; Berger, J. How Attribute Quantity Influences Option Choice. J. Mark. Res. 2012, 49, 942–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, A.; Kenning, P. Utilitarian and Hedonic Motivators of Shoppers’ Decision to Consult with Salespeople. J. Retail. 2014, 90, 428–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, G.; Park, J.; Feick, L. The Role of Product Type and Country—Of—Origin in Decisions about Choice of Endorser Ethnicity in Advertising. Psychol. Mark. 2006, 23, 487–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.; Kim, J.; Sung, Y. The Effect of Gender Stereotypes on Artificial Intelligence Recommendations. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 141, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longoni, C.; Cian, L. Artificial Intelligence in Utilitarian vs. Hedonic Contexts: The “Word-of-Machine” Effect. J. Mark. 2022, 86, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista Research Development. Social Media Usage in South Korea—Statistics & Facts. Available online: https://www.statista.com/topics/5274/social-media-usage-in-south-korea/#topicOverview (accessed on 17 November 2023).

- Generation MZ. Available online: http://www.koreanlii.or.kr/w/index.php/Generation_MZ?ckattempt=1 (accessed on 17 November 2023).

- Girard, T.; Dion, P. Validating the Search, Experience, and Credence Product Classification Framework. J. Bus. Res. 2010, 63, 1079–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Danks, N.P.; Ray, S. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R: A Workbook; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 115–138. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Matthews, L.M.; Matthews, R.L.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: Updated Guidelines on Which Method to Use. Int. J. Multivar. Data Anal. 2017, 1, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A New Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Variance-Based Structural Equation Modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a Silver Bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V.G. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM): An Emerging Tool in Business Research. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, T.K.; Henseler, J. Consistent and Asymptotically Normal PLS Estimators for Linear Structural Equations. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2015, 81, 10–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Hubona, G.; Ray, P.A. Using PLS Path Modeling in New Technology Research: Updated Guidelines. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2016, 116, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The Moderator–Mediator Variable Distinction in Social Psychological Research: Conceptual, Strategic, and Statistical Considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and Resampling Strategies for Assessing and Comparing Indirect Effects in Multiple Mediator Models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitzl, C.; Roldan, J.L.; Cepeda, G. Mediation Analysis in Partial Least Squares Path Modeling: Helping Researchers Discuss More Sophisticated Models. Ind. Manage. Data Syst. 2016, 116, 1849–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keil, M.; Tan, B.C.Y.; Wei, K.K.; Saarinen, T.; Tuunainen, V.; Wassenaar, A. A Cross-Cultural Study on Escalation of Commitment Behaviors in Software Projects. MIS Q. 2000, 24, 299–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alboqami, H. Trust me, I’m an influencer!-Causal recipes for customer trust in artificial intelligence influencers in the retail industry. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 72, 103242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S.; Chang, H.; Zhang, L. An Integrated Model of Congruence and Credibility in Celebrity Endorsement. Int. J. Advert. 2022, 41, 1358–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Henninger, C.E.; Le Normand, A.; Blazquez, M. Sustainable what…? The role of corporate websites in communicating material innovations in the luxury fashion industry. J. Des. Bus. Soc. 2021, 7, 83–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolova, K.; Kefi, H. Instagram and YouTube bloggers promote it, why should I buy? How credibility and parasocial interaction influence purchase intentions. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 53, 101742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schifferstein, H.N.; Cleiren, M. Capturing product experiences: A split-modality approach. Acta Psychol. 2005, 118, 293–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheehan, K. Who, Moi? Exploring the Fit Between Celebrity Spokescharacters and Luxury Brands. J. Curr. Issues Res. Advert. 2020, 41, 144–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazzola, P.; Colombo, G.; Pezzetti, R.; Nicolescu, L. Consumer empowerment in the digital economy: Availing sustainable purchasing decisions. Sustainability 2017, 9, 693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.V.; Ryu, E.; Muqaddam, A. I trust what she’s# endorsing on Instagram: Moderating effects of parasocial interaction and social presence in fashion influencer marketing. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2021, 25, 665–681. [Google Scholar]

- Hekkert, P.; Thurgood, C.; Whitfield, T.A. The Mere Exposure Effect for Consumer Products as a Consequence of Existing Familiarity and Controlled Exposure. Acta Psychol. 2013, 144, 411–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darley, W.K.; Smith, R.E. Gender Differences in Information Processing Strategies: An Empirical Test of the Selectivity Model in Advertising Response. J. Advert. 1995, 24, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Article 23 of the Personal Information Protection Act. Available online: https://elaw.klri.re.kr/eng_service/lawView.do?hseq=53044&lang=ENG (accessed on 4 August 2023).

- Article 33 of the Statistics Act (Personal Information Protection). Available online: https://law.go.kr/LSW/lsEfInfoP.do?lsiSeq=252677# (accessed on 4 August 2023).

| Constructs | Items |

|---|---|

| Attractiveness | ATT1: The endorser has a strong attractiveness. |

| ATT2: The endorser has a very beautiful face. | |

| ATT3: The endorser is very lively. | |

| Expertise | EXP1: The endorser has expertise in her field. |

| EXP2: The endorser has product experience. | |

| EXP3: The endorser has extensive product knowledge. | |

| Trustworthiness | TRU1: The endorser is an honest person |

| TRU2: The endorser is trustworthy. | |

| TRU3: The endorser is a reliable source of information. | |

| Endorser Product Fit | EPF1: The characteristic of the endorser is consistent with the attributes of the product that she promotes and sells. |

| EPF2: The product attributes that the endorser promotes and sells are highly appropriate for her. | |

| EPF3: The pairing of the endorser with the product is natural. | |

| Product Attitude | PA1: I think the products or services recommended by the endorser are good. |

| PA2: I have a positive impression of the products or services recommended by the endorser. | |

| PA3: I like the products or services recommended by the endorser. | |

| PA4: I have a positive attitude towards the products or services recommended by the endorser. |

| Variables | Category | Total N = 376 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Percentage (%) | ||

| Gender | Male | 186 | 49.5% |

| Female | 190 | 50.5% | |

| Age | Below 20 | 42 | 11.2% |

| 20–29 | 83 | 22.2% | |

| 30–39 | 142 | 37.7% | |

| 40–49 | 65 | 17.3% | |

| Above 50 | 44 | 11.6% | |

| Education Level | Middle school or below | 26 | 6.9% |

| High school | 69 | 18.4% | |

| Undergraduate or bachelor | 153 | 40.7% | |

| Postgraduate or above | 88 | 23.4% | |

| Other | 40 | 10.6% | |

| Occupation | Student | 67 | 17.5% |

| Company Employee | 127 | 33.8% | |

| Govt. Employee | 61 | 16.2% | |

| Freelancer | 75 | 19.9% | |

| Self-employed | 32 | 8.5% | |

| other | 14 | 3.7% | |

| Monthly Income (KRW) | Below 500,000 | 86 | 22.9% |

| 500,001–1,000,000 | 74 | 19.7% | |

| 1,000,001–2,000,000 | 75 | 19.9% | |

| 2,000,001–3,000,000 | 80 | 21.3% | |

| 3,000,001–4,000,000 | 37 | 9.8% | |

| Above 4,000,000 | 24 | 6.4% | |

| Constructs | Loadings | Cronbach’s Alpha | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attractiveness | 0.865 | 0.766 | 0.864 | 0.680 |

| 0.812 | ||||

| 0.795 | ||||

| Expertise | 0.815 | 0.787 | 0.876 | 0.702 |

| 0.855 | ||||

| 0.842 | ||||

| Trustworthiness | 0.823 | 0.784 | 0.874 | 0.689 |

| 0.858 | ||||

| 0.826 | ||||

| Endorser Product Fit | 0.815 | 0.797 | 0.881 | 0.712 |

| 0.866 | ||||

| 0.849 | ||||

| Product Attitude | 0.783 | 0.791 | 0.864 | 0.614 |

| 0.804 | ||||

| 0.764 | ||||

| 0.784 |

| ATT | EXP | TRU | EPF | PA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATT | 0.824 | ||||

| EXP | 0.519 | 0.838 | |||

| TRU | 0.434 | 0.433 | 0.836 | ||

| EPF | 0.583 | 0.573 | 0.505 | 0.844 | |

| PA | 0.600 | 0.588 | 0.511 | 0.635 | 0.784 |

| ATT | EXP | TRU | EPF | PA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATT | |||||

| EXP | 0.661 | ||||

| TRU | 0.546 | 0.548 | |||

| EPF | 0.737 | 0.723 | 0.635 | ||

| PA | 0.762 | 0.745 | 0.647 | 0.800 |

| R2 | Adjusted R2 | Q2 | Model Fit | Value (SM) | HI99 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attractiveness | 0.340 | 0.338 | 0.223 | SRMR | 0.062 | 0.088 |

| Expertise | 0.328 | 0.326 | 0.228 | DULS | 0.531 | 0.606 |

| Trustworthiness | 0.255 | 0.253 | 0.172 | DG | 0.224 | 0.298 |

| Product Attitude | 0.544 | 0.539 | 0.327 | NIF | 0.805 |

| Hypothesis | Path | Path Coefficient | T Statistics | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1.1 | Endorser Product Fit → Attractiveness | 0.583 | 12.990 *** | Supported |

| H2.1 | Endorser Product Fit → Expertise | 0.573 | 11.809 *** | Supported |

| H3.1 | Endorser Product Fit → Trustworthiness | 0.505 | 10.203 *** | Supported |

| H1.2 | Attractiveness → Product Attitude | 0.249 | 5.104 *** | Supported |

| H2.2 | Expertise → Product Attitude | 0.229 | 4.443 *** | Supported |

| H3.2 | Trustworthiness → Product Attitude | 0.165 | 3.833 *** | Supported |

| H4 | Endorser Product Fit → Product Attitude | 0.276 | 4.833 *** | Supported |

| Indirect Effect of Moderator | Confidence Interval | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paths | β | STDEV | T Statistics | VAF | 2.50% | 97.50% |

| Endorser Product Fit → Attractiveness →Product Attitude | 0.145 *** | 0.032 | 4.552 | 0.345 | 0.085 | 0.210 |

| Endorser Product Fit → Expertise → Product Attitude | 0.131 *** | 0.033 | 3.951 | 0.322 | 0.071 | 0.200 |

| Endorser Product Fit → Trustworthiness → Product Attitude | 0.083 *** | 0.018 | 3.492 | 0.232 | 0.039 | 0.100 |

| Path | Path Coefficients (T Statistics) | Path Coefficients Diff (T Statistics) | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hedonic (N = 186) | Utilitarian (N = 190) | |||

| Attractiveness → Product Attitude | 0.446 (6.505) | 0.230 (3.348) | 30.512 | Hedonic > Utilitarian |

| Expertise → Product Attitude | 0.215 (2.836) | 0.381 (5.953) | −22.960 | Hedonic < Utilitarian |

| Trustworthiness →Product Attitude | 0.230 (4.669) | 0.263 (3.571) | −5.096 | Hedonic < Utilitarian |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kong, H.; Fang, H. Research on the Effectiveness of Virtual Endorsers: A Study Based on the Match-Up Hypothesis and Source Credibility Model. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1761. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16051761

Kong H, Fang H. Research on the Effectiveness of Virtual Endorsers: A Study Based on the Match-Up Hypothesis and Source Credibility Model. Sustainability. 2024; 16(5):1761. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16051761

Chicago/Turabian StyleKong, Haiyan, and Hualong Fang. 2024. "Research on the Effectiveness of Virtual Endorsers: A Study Based on the Match-Up Hypothesis and Source Credibility Model" Sustainability 16, no. 5: 1761. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16051761

APA StyleKong, H., & Fang, H. (2024). Research on the Effectiveness of Virtual Endorsers: A Study Based on the Match-Up Hypothesis and Source Credibility Model. Sustainability, 16(5), 1761. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16051761