Abstract

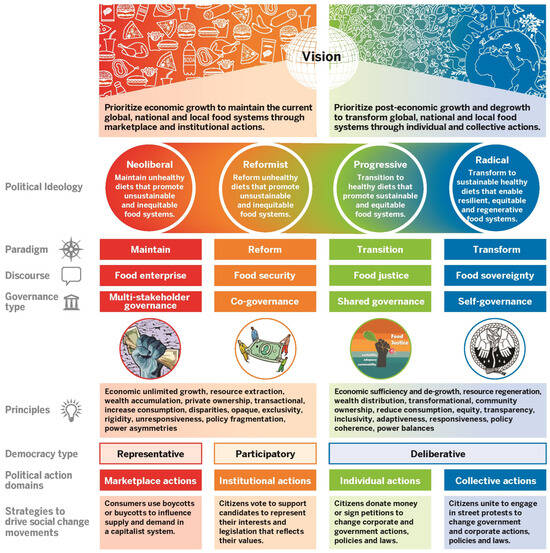

Effective governance is essential to transform food systems and achieve the United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals 2030. Different political ideologies and paradigms inhibit or drive social change movements. This study examined how food systems governance has been described. Thereafter, we reviewed graphic frameworks and models to develop a typology for civil society actors to catalyze social change movements to transform food systems for people and the planet. The scoping review involved (1) formulating research questions; (2) developing a search strategy to identify evidence from four English-language electronic databases and reports, 2010–2023; and (3–4) selecting, analyzing, and synthesizing evidence into a narrative review. Results yielded 5715 records, and 36 sources were selected that described and depicted graphic frameworks and models examined for purpose, scale, political ideology, paradigm, discourse, principles, governance, and democracy. Evidence was used to develop a graphic food systems governance typology with distinct political ideologies (i.e., neoliberal, reformist, progressive, radical); paradigms (i.e., maintain, reform, transition, transform); discourses (i.e., food enterprise, food security, food justice, food sovereignty); types of governance (i.e., multistakeholder, shared, self); and democracy (i.e., representative, participatory, deliberative). This proof-of-concept typology could be applied to examine how change agents use advocacy and activism to strengthen governance for sustainable diets, regenerative food systems, and planetary health.

1. Introduction

Human actions are undermining the Global Commons that support human and planetary health [1]. Effective governance is needed to ensure the co-existence of the natural systems upon which humans depend to survive and thrive [1]. Strengthening intersectoral governance capacity and resilience to respond to natural and human-induced shocks is essential to safeguard human and planetary health for future generations [2].

Food systems contribute up to one-third of global greenhouse gas emissions that accelerate the climate crisis and are vulnerable to climate change impacts by undermining the resilience and food security of people worldwide [3]. The United Nations (UN) system has prioritized the transformation of food systems with high-impact initiatives to address challenges that exacerbate hunger, undernutrition, and food insecurity worldwide, support climate and biodiversity goals, and promote health equity and human rights [3,4]. In 2022, about 783 million people worldwide experienced hunger, and 2.5 billion people were food insecure, worsened by civil conflict, climate change, global pandemics, food and energy supply shortages, and economic hardships that prevented the affordability of healthy nutrient-dense diets from reducing all forms of malnutrition [3].

The UN system defines food systems transformation as the “need for the change to be intentional and profound, based on factual understandings and societal agreements and aimed at achieving outcomes at scale” [5] (p. vi). The UN leads the advancement of 17 goals and 169 targets in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) 2030 agenda [5]. The UN Decade of Action on Nutrition (2016–2025) has also prioritized healthy, equitable, and sustainable diets under a changing climate [6]. The UN Secretary-General António Guterres urged world leaders at the 2023 SDG Summit to develop a Rescue Plan for People and the Planet, given that 50 percent of 140 SDG targets were off track, and a third of the targets were at or below 2015 baseline levels [7]. Effective governance is an important cross-cutting issue identified by the Food System Countdown Initiative, which emerged from the 2021 UN Food Systems Summit, to monitor progress in transforming food systems to achieve the SDG agenda by 2030 [8].

The 2022 Global Nutrition Report concluded that a broader constituency of food system actors is needed to strengthen commitments, governance, and improve food and nutrition security to reduce all forms of malnutrition [9]. While there is agreement that diets and agri-food systems must be more resilient, equitable, and sustainable, there is no consensus about how humanity may build a healthy and just food future that transcends current boundaries [10].

1.1. Strengthening Civil Society’s Capacity to Address Policy Inertia to Strengthen Governance

The 2019 Lancet Commission on the Global Syndemic identified policy inertia as a major systemic driver of global malnutrition (i.e., undernutrition and obesity) and climate change [11]. Policy inertia results from the nexus of weak leadership and governance of government decision-makers, opposition by commercial vested business interests to maintain the status quo, and a lack of sufficient public and civil society demand for changing food systems [11]. Policy inertia perpetuates unhealthy, inequitable, and unsustainable systems that drive the Global Syndemic of undernutrition, obesity, and climate change [11]. The Lancet Global Syndemic Commission [11] and other reports [12] identified the need to strengthen civil society’s capacity to demand social and political change from governments to strengthen national and international governance levers to fully implement policy actions that have been agreed upon by through international resolutions and treaties [11]. The Lancet Global Syndemic Commission also suggested that civil society could also help to transform business models, and to hold public- and private-sector actors accountable for actions that impede or undermine food systems transformation.

Civil society actors use different forms of advocacy and activism to catalyze social and political change movements to shift attitudes and social norms and address power differentials between other actors [13,14]. Advocacy and activism can change institutional policies and practices, and re-distribute power and resources to promote safer, healthier, and more sustainable food communities and environments [14,15]. Public health practitioners have used social movements to advance environmental justice, gender empowerment, health equity, and indigenous peoples’ sovereignty to support sustainable food systems [16].

The International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems (IPES-Food) and ETC Group [17] have encouraged civil society actors to engage in a long food movement to transform food systems by 2045 [17]. However, a conceptual model is needed to mobilize change agents to catalyze social movements and transform food systems to achieve the UN SDG 2030 agenda and mitigate the adverse effects of climate change.

1.2. Study Purpose

The published literature has not summarized different terms used to describe food systems governance or the range of graphic food systems governance frameworks and models to depict useful concepts that may be integrated into one visual typology to understand social change movement strategies to transition and transform current agri-food systems. This paper examines how food systems governance has been described and graphically depicted. We synthesize diverse literature to develop a food systems governance typology to enable change agents to drive social movements to support sustainable diets, regenerative food systems, and planetary health. First, we synthesize literature that discusses how governance processes influence agri-food systems. Second, we describe food systems governance terms. Third, we examine existing food system typologies and whether and how they address governance processes. Thereafter, we describe the rationale and steps taken to conduct a scoping review of the evidence for graphic frameworks and models analyzed for specific constructs of interest to develop a graphic food systems governance typology with strategies that civil society actors could use to catalyze social change movements for sustainable diets, regenerative food systems, and planetary health.

1.3. Synthesizing Literature That Describes Food Systems Governance

Governance involves the system of rules, institutions, and authority that collectively coordinate and manage society, including the political, organizational, and administrative institutions, rules, and processes used by stakeholders (state and non-state actors) to articulate their interests, exercise their legal rights, make decisions, mediate differences, and meet their obligations [18,19,20,21,22].

Governance is an expression of different political ideologies, defined as a set of ideals, principles, doctrines, and symbols of a political party or social movement that enable one to interpret and evaluate the morality and appropriateness of one’s own and other’s behavior and those of government [23]. Democracy is a form of governance where a majority of citizens either directly or indirectly elect leaders to represent their interests through legislation and laws [24]. Anderson (2023) described democracy as being “threatened by authoritarian governments, lack of respect for the rule of law, polarization of public opinion, disinformation and criminalization of dissent” [25]. Corporate power is growing in every sector of the food system that influences domestic and international governance forums [25]. Food democracy, food justice, and food sovereignty are concepts related to governance by supporting social equity, healthy food access, community participation, environmental sustainability, and food system transformation [25,26,27]. Anderson (2023) suggests that achieving food democracy will require alternative ways for communities to produce and consume food beyond what is provided by large corporations [25]. A deliberative democratic approach to changing unhealthy and unsustainable food systems will require public discourse and accountability to shift the power imbalances in the governance structures of food movements [28].

Food systems are complex and adaptive and involve interactions among diverse actors at many levels who often have competing interests, values, and perspectives. Food systems governance involves the interactions of diverse actors to bridge the institutional silos across the agriculture, education, public health, nutrition, and planning sectors [29]. Food systems governance operates at many levels and scales within and across space, time, and geographies [30]. While governments have an important leadership role in improving food systems, governance is not limited to government actors’ decisions [31].

More than a dozen different terms have been used to describe food systems governance in the published and grey literature that vary based on the actors, context, geography, scale, level, and type of governance processes that influence diets and agri-food systems. These terms include food, nutrition, and/or food systems governance [21,32,33,34,35]; food safety governance [36]; food security governance [37]; aquaculture governance [38]; agri-food chain and agroecosystems governance [39]; sustainability governance for food systems [40]; and private or corporate food governance [17,41,42,43]. Many UN system and grey literature sources described aspirational principles to transform food systems, such as collaborative shared governance [44], inclusive food systems and rights-based governance [45,46,47,48], good governance [49,50], responsible governance [51], regulatory and accountable governance [52], and transformative food governance [53].

Recent work has described efforts to transition and transform current food systems to become more sustainable and regenerative [54,55,56,57,58,59,60]. Transition involves “incrementalism that suggests moving from one place or state to another” whereas transformation refers to reinventing or reshaping to create a “deep, rapid and radical global systems change” [61] (p. 787). Global South scholars have emphasized that an equitable transition is needed to achieve sustainable food systems to promote dietary diversity for socially marginalized populations [62]. Collective actions to transform food systems at global, regional, national, and local levels have been proposed but present many challenges.

Governance actors interact at different levels and have competing visions, discourses, and narratives for sustainable healthy diets and sustainable food systems based on disciplinary views [30,63,64]. A vision is the ability to develop an idea or image in one’s mind of what something could be in the future [65]. A paradigm is a set of assumptions, beliefs, ideas, and values that represent a way of thinking of individuals, groups, or society [66]. A discourse is the language used in social life that is interconnected with other elements in wider society [67], whereas a narrative tells a story with a sequence of events [68].

Béné et al. (2019) [63] described four distinct narratives about the current food systems and solutions to promote sustainability. These narratives include the (1) agricultural view based on insufficient food to address the yield gap to promote food security through increased efficiency of production; (2) diet and health view to address the nutrient gap to support diet quality and population health; (3) environmental view to reduce food systems’ footprints by shifting supply and demand; and (4) social justice view to decentralize power and promote grassroots autonomy and action to transform food systems.

There is currently no agreement about whether and how governments and civil society actors should engage with international business alliances and global networks that have contributed to unhealthy diets and unsustainable food systems and also represent powerful stakeholders who influence governance processes and outcomes [69]. Strong democratic bottom-up and participatory processes are needed to drive policies and systems changes that shift existing economic incentives to prioritize social equity and food and nutrition security domains, especially within low-income countries [62].

1.4. Existing Food System Typologies

A food system encompasses the elements and activities to grow, harvest, process, package, transport, and market food and beverage products to people, as well as the reuse and disposal of food waste and packaging in the environment [70]. Sustainable healthy diets promote all dimensions of an individual’s health and well-being; are accessible, affordable, safe and equitable; and culturally acceptable [70]. Regenerative food systems support sustainable healthy diets, ecosystems, and planetary health [55].

Conceptual advancements have described various food system models over the past decade. Food systems have been described as food chains, food cycles, food webs, and food contexts at various spatial levels, including community, local, national, regional, and global [71]. The High Level Panel of Experts (HLPE) on Food Security and Nutrition advises the FAO Committee on World Food Security, which describes traditional, intermediate, and modern food systems based on food supply and food environments [72]. Scholars have further developed the FAO’s food environment typologies that describe wild, cultivated, and built food environments [73] and other factors that influence food environments, such as kin and community, informal and formal retail, and food aid [74].

The Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition, in collaboration with the FAO and several universities, developed the Food Systems Dashboard in 2020 that conceptualized five distinct food system typologies to help decision-makers identify effective policies to improve human and planetary health outcomes based on the political economy context within low-, middle-, and high-income countries [75,76]. The five food system typologies include type 1: rural and traditional; type 2: informal and expanding; type 3: emerging and diversifying; type 4: modernizing and formalizing; and type 5: industrial and consolidated [75,76]. These typologies are complemented by diagnostic tools to enable policymakers to strengthen food systems governance and accountability to improve food security, nutrition, environmental, and health outcomes [77].

Loring (2022) [55] described a food systems typology with four quadrants to show the flexibility of livelihoods versus the diversity of available resources. A regenerative food system is more flexible and diverse when compared to degenerative, coerced, or impoverished food system types [55]. Another distinct typology was proposed to guide government-led, public-sector engagement with food and beverage industry actors through public–private partnerships while vetting the type of engagement when businesses profit from products detrimental to human and planetary health [44]. Existing typologies describe tools or approaches to help stakeholders analyze food system challenges and inform policy actions. However, the typologies discussed above do not provide graphic depictions of food systems governance. These typologies also do not explicitly examine different political ideologies and paradigms that may inhibit or drive social change movements for civil society to use advocacy and activism to strengthen governance that will support sustainable diets, regenerative food systems, and planetary health. This study addresses these knowledge gaps.

2. Materials and Methodology

A scoping review was selected as the methodology rather than a systematic evidence review due to the breadth of a large body of interdisciplinary literature, existing knowledge gaps discussed in the previous section, and to clarify concepts and definitions related to food systems governance frameworks and models [78,79]. This work could serve as a foundation for others to conduct a critical review or systematic evidence review. The lead author (VIK) conducted a preliminary search of electronic databases to identify published reviews of food systems governance between 2006 and 2021 [19,20,21,31,80] that informed the search strategy. None of these review articles had analyzed graphic frameworks and models for food systems governance. There are distinct differences between theoretical and conceptual frameworks or models across inductive and deductive research approaches. However, many studies do not distinguish between these terms. We used the terms interchangeably for this study.

The co-investigators adapted the five scoping review steps described by Arksey and O’Malley (2005) [78] to (1) formulate the research questions; (2) identify relevant evidence; (3) select, organize, and analyze evidence; and (4) synthesize, and summarize the results.

- Step 1: Formulate the research questions

This scoping review was guided by three research questions (RQ) described below.

- RQ1: What types of visual or graphic food systems governance frameworks and models have been published to describe how actors maintain, reform, transition, or transform food systems?

- RQ2: How do the graphic food system governance frameworks and models differ by purpose, application (scale and level), political ideology, paradigm, discourse, principles, and types of governance and democracy?

- RQ3: How can the evidence be synthesized into a food systems governance typology with strategies to promote healthy, equitable, resilient, and sustainable food systems for people, ecosystems, and planetary health?

- Step 2: Identify relevant evidence

The lead author (VIK) searched four English-language electronic databases (i.e., Academic Search Complete, PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science). Evidence sources were included if they were published between 1 January 2010 and 31 August 2023. VIK and KNL supplemented the search for peer-reviewed publications using Google and Google Scholar search engines (first 100 hits) and the UN digital library database to identify frameworks and models in grey literature reports. Records that did not explicitly describe food systems governance mechanisms or approaches that were not described in the inclusion criteria were excluded. We excluded non-English articles and grey literature sources that did not explicitly describe or visually depict a food systems governance framework or model and records that focused only on food systems or governance but not both concepts. Table 1 describes the search strategy used to conduct the evidence-scoping review with inclusion and exclusion criteria, search platforms, and terms.

Table 1.

Search strategy used for the scoping review of evidence about food systems governance frameworks and models.

- Steps 3 and 4: Select, organize, analyze, synthesize, and summarize the evidence

We selected published articles and grey literature sources that described and depicted a visual or graphic conceptual framework or model related to food systems governance. The first author (VIK) selected, organized, identified, and coded themes relevant to the stated purpose and application of the framework or model and documented whether the constructs of interest were discussed for political ideology, paradigm, discourse, principles, and types of governance and democracy. Given the exploratory nature of the research questions, we did not assess the quality of the evidence or the risk of bias for studies included.

We included peer-reviewed published articles or book chapters and grey literature reports that presented graphic depictions through frameworks or models that discussed food systems governance with a designated purpose. We first summarized the names of each graphic framework or model in an evidence table. Thereafter, we developed a protocol to search each document included in the scoping review to conduct a thematic analysis that compared each framework or model for specific constructs of interest in a separate evidence table. The constructs of interest included purpose, political ideology, paradigm, discourse, principles, and types of governance and democracy.

Three categories were established to describe the intended purpose of the framework or model, including causal/assessment: monitoring and evaluation, advocacy or activism, and regulatory. Six categories were created to describe the application of the framework or model at various scales and levels, including multilevel, global, regional, national, and local or municipality. Four categories describe the political ideology, including neoliberal, reformist, reformist, progressive, and radical. Five categories described the distinct paradigms, including maintain, reform, transition, transform, and other. Five categories described the discourse, including food enterprise, food security, food justice, food sovereignty, and other. Several principles included transparency, coherent policies, inclusivity, adaptiveness, responsiveness, and address power symmetries. Three categories were established to describe the type of democracy, including representation, participatory, and deliberative. The categories were refined after the co-authors independently reviewed the papers and met to discuss any differences in the interpretation to reach a consensus on categorizing the constructs for each framework and model. The findings were synthesized in a narrative review below and a supplemental table. We also extracted the image for each graphic framework or model with the source in a supplemental figure.

3. Results

The scoping review yielded 5715 records identified through four electronic databases. Table 2 summarizes 36 frameworks and models analyzed for purpose, scale, political ideology, paradigm, discourse, and types of governance and democracy. The majority (n = 25) were identified from peer-reviewed articles [81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105], and 23 of these were published between 2017 and 2023. Fewer frameworks (n = 11) and models were found in grey literature reports [106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116]; eight of these were published between 2017 and 2023. Of the 36 sources reviewed, 11 described models, 19 described frameworks, one described a schema, and five UN agency reports did not use either framework or model in the name of the conceptual graphic. None used the term food systems governance typology.

Table 2.

Food system governance frameworks and models included in the review.

Table 3 defines 13 constructs used in the scoping review for graphic food systems governance frameworks and models. Table 4 summarizes the thematic analysis and sources for these constructs used to develop the food systems governance typology. Supplemental Table S1 provides detailed evidence used to develop the typology with social change strategies to maintain, reform, transition, or transform food systems.

Table 3.

Constructs used in the scoping review for graphic food systems governance frameworks and models.

Table 4.

Constructs analyzed for the food systems governance frameworks and models.

3.1. Purpose and Application of the Frameworks and Models

The 36 frameworks and models included in the scoping review were causal or analytic and could be used to assess, monitor, and/or evaluate food system governance outcomes and to learn from and adapt strategies to strengthen governance. Three models were designed to guide advocacy or activism strategies to transform food systems governance [84,95,96], and one model described regulatory food systems governance [81].

A majority of the frameworks and models were intended to be applied at many levels or scales, including local, state or province, national, regional, and global. The networked governance framework [100] was developed to examine how multistakeholder governance and networked governance (i.e., shared, brokered, and fragmented) evolved for agricultural policy development across several countries in Africa and South Asia. Five frameworks and models were discussed within a national context for Australia, Japan, the Netherlands, South Africa, and Sri Lanka [87,91,101,103,116]. Two models were developed to foster democracy and collaborative governance to strengthen local food systems [90,94].

Several models and frameworks were designed to identify and analyze actors involved in food systems governance interactions and processes [81,83,85,88,92,98,100,101]. Some were developed as tools to improve or enhance agri-food value chains [82,106], promote sustainable food enterprises and entrepreneurship [91,103,108], support food finance architecture that incorporates health, environmental, and societal concerns into financial decision-making; and strengthen economic development and stability for food systems governance [113,114] (Supplemental Table S1).

3.2. Political Ideology, Paradigm, and Discourse

A political ideology is a set of ideals, principles, doctrines, and symbols of a political party or movement that enable one to interpret and evaluate the morality and appropriateness of a government’s and one’s own and others’ behaviors and policies [22]. Nine sources critiqued the neoliberal capitalist model described as the dominant political ideology that influences current food systems governance (Table 4). Holt Giménez and Shattuck (2011) [89] and Clark et al. (2021) [83] described the most comprehensive frameworks with a continuum of four distinct political ideologies underlying the corporate food regime (neoliberal and reformist) and food movements (progressive and radical). Lozano-Cabedo and Gómez-Benito (2017) [96] described a food citizenship model that emphasized the need for social change movements to be integrated into food sovereignty approaches to challenge the status quo in the neoliberal governance model.

A paradigm is a set of assumptions, beliefs, ideas, and values that represent the mindset of a group, culture, or society and present ways of thinking by individuals and larger groups [65]. Four sources discussed or critiqued the maintenance of the current dominant paradigm, four sources discussed a reform paradigm, eight sources discussed a transition to more sustainable food systems governance models, and 15 sources described a paradigm to transform food systems. Lawrence et al. (2015) suggested the need to strategically combine all three orders of food systems change to adjust (first order), reform (second order), and transform (third order) to dissuade policymakers from selecting one over another because insights from all three orders of change represent a more holistic and systems approach to transform food systems [92].

Other terms used to describe the neoliberal food systems governance approach were the industrial food systems paradigm [81], development paradigm [106], productivism paradigm [85], and the pragmatic research paradigm to identify feasible solutions [84]. Ruben et al. (2021) discussed a food systems analysis framework and presented a transformation pyramid with five components (i.e., anchoring, responsiveness, connectivity, goals, and purpose) to help drive a paradigm shift to transform food systems to be healthy, inclusive and sustainable for people in the future [99].

Discourse is a way of framing, viewing, and communicating ideas about practices that give meaning to social and political realities [66]. Discourses have a broader meaning than narratives, which often use personal stories to describe and enable people to understand the discourse about certain realities [67]. Fifteen sources discussed food systems governance within the context of food security; six sources discussed food enterprise; seven sources discussed food justice; and seven sources discussed food sovereignty.

Other discourses were identified. Baker and Demaio (2019) observed that food movements in countries have developed discourses and alternative institutional spaces and policies to govern healthy, sustainable food systems [81]. Some sources emphasized the need to shift the current discourse from malnutrition to healthy diets [88], foster an iterative and deliberative discourse [90], shift the societal discourse coalitions [93], create spaces to foster discourse about the local food system to promote food democracy [94], distinguish between the role of the citizen versus the consumer in discourses about food citizenship [96], and shift from food security to a food system resilience discourse [99].

3.3. Principles

Of the 36 frameworks and models, 26 sources discussed one or more guiding principles for food systems governance (Table 4 and Table S1). Five sources highlighted business principles to understand, improve, and measure business performance to achieve sustainable food value chains that are market-driven, dynamic and systems-based, scalable, green, multilateral, inclusive, and profitable; reduce economic costs and maximize profits; and to maintain or reform food systems to achieve food enterprise or food security outcomes [91,95,97,106,113].

Twelve sources described principles to support progressive political ideologies to transition to more local, regional, and sustainable diets and food systems. Tribaldos and Kortetmäki (2022) [102] discussed different forms of justice rooted in principles to inform a low-carbon transition to rights-based, equitable, and sustainable food systems. Three sources discussed agroecological principles, including human and social value, responsible governance, co-creation of knowledge, preserving culture and food traditions, circular economy, diversity, synergies, resilience, recycling, regulation, and efficiency [87,104,109]. Herens et al. (2022) suggested principles such as systems-based problem-solving, boundary-spanning, adaptability, and inclusiveness [88]. Two sources described food sovereignty principles that emphasized spirituality, balance with nature, biocentrism, collective rights, communal resources, circularity, equity, collective reciprocity, solidarity, sustainability, and resilience [87,107]. The FAO [107] described the PANTHER principles to promote human rights, which include participation, accountability, non-discrimination, transparency, human dignity, empowerment, and the rule of law.

3.4. Types of Governance

Fifteen sources discussed multistakeholder governance, of which five sources described shared collaborative governance models [83,90,96,98,99], and two sources discussed co-governance models [83,101]. Clark et al. (2021) described a governance engagement continuum 2.0 model [83], adapted from the corporate food regime and food movements framework developed by Holt Giménez and Shattuck 2011 [89] and Andrée et al. (2019) [13], which discussed three forms of governance (i.e., multi-stakeholder, co-governance, and self-governance) to show how social movement organizations could create new deliberative governance spaces through convening to change power dynamics.

3.5. Types of Democracy

Lorenzini (2019) described three forms of democracy (i.e., representative, participatory, and prefigurative) across three political action domains (i.e., market-based, institutional, and protest) [95]. Respecting and protecting human rights were highlighted in four frameworks to achieve food democracy where less influential actors regain democratic control over food system decisions to enable a more sustainable transformation [94,107,110,115]; and justice and nutrition and health equity for populations [86,97,102]. Two sources explicitly mentioned food democracy [92,94], and three sources described the need for democratic governance and accountability [101,104,107].

4. Discussion

This study scoped the relevant published and grey literature to integrate constructs of interest related to social and political change movements to transform food systems governance. We wanted to understand how current unhealthy and unsustainable food systems are maintained or reformed or to transform food systems to support sustainable diets, ecosystems, and planetary health. We found that many different terms are used in the literature to describe food systems governance, including food, nutrition, and food systems governance; agri-food chain governance, agroecosystem governance, food safety governance, governance for sustainable food systems, private food governance, and corporate food system governance; local, regional, and global food system governance; multilevel, multistakeholder, networked and collaborative governance; networked governance for the quality and safety of agri-food systems; good governance; and innovative, inclusive, responsible, transformative, and regulatory governance.

The evidence synthesized from the scoping review showed that food systems governance involves many interactions among diverse actors at different levels. Different political ideologies, paradigms, and discourses are reflected by distinct values-based principles. Distinct tensions exist within the local versus regional and global food system discourses, which could be addressed using resilience thinking and approaches to inform viable solutions to improve governance at many scales to transform food systems [36]. The four types of food systems governance are supported by various forms of democracy and political actions. Food systems governance may lead to different outcomes to maintain or reform current food systems through marketplace and institutional mechanisms or transition and transform food systems to be more equitable, healthy, resilient, and sustainable using democratic processes at different scales and in various contexts.

Several papers critiqued the principles for maintaining or reforming current food systems, such as prioritizing economic growth, resource extraction, wealth accumulation, private ownership, disparities, exclusivity, policy fragmentation, and power asymmetries. Other papers proposed governance principles to transition and transform food systems to reduce consumption and support degrowth and a restorative economy. These principles highlighted the need for transparency, coherent policies, inclusivity, adaptiveness, responsiveness, and addressing power asymmetries between governance actors [29,118].

Extensive literature has described guiding principles for food systems transition and transformation. Interventions must be implemented to target strategic leverage points. Moreover, food governance actors must commit to the principles of transparency, independence, policy coherence, inclusivity, connectivity, adaptiveness, responsiveness, renewability, resilience, equity, consultation, and evidence-informed approaches [46,47,119]. Applying these principles will reconnect people to nature and restructure institutions and skills to achieve food system sustainability and resilience [47,55,120,121,122].

Recent models and frameworks have emphasized that multilevel and multistakeholder coordination, cooperation, and collaboration are essential to support the transformation of food systems [5,18,88,96,111,112,116]. UN agencies have encouraged five building blocks to advance food systems transformation that include (1) fostering broad multi-stakeholder participation; (2) ensuring a clear understanding of the food system; (3) nurturing inclusive and effective collaborations; (4) defining a compass and roadmap; and (5) securing sustainability of the collaboration [5]. Leeuwis et al. (2021) suggested that effective strategies will depend on the capacity of actors to navigate their differences to work toward a mutually acceptable future [93]. Others have cautioned that corporate governance models that encourage technological solutions but fail to engage people and communities through democratic approaches will not effectively change power inequities, ownership, and control over resources to support a food systems transformation [17,43].

Two frameworks included in the scoping review described agroecological principles to support food systems transition and transformation [102,107]. These frameworks align with the concept of regenerative food systems [55,56,57], agroecosystem governance described by Allen et al. (2018) {39], and the HLPE recommendation for stakeholders to include agroecological principles in responsible food systems governance [17]. Recently published work has described agroecology as a social movement to support climate change adaptation and mitigation in order to shift from a dependency on fossil fuels and to strengthen biodiversity, resiliency, nutrition security, democracy, and equity for all people [123,124]. An agroecology assessment framework is available to evaluate projects for their alignment with the HLPE’s agroecological principles [17,125].

Figure 1 shows a proof-of-concept food systems governance typology that integrated constructs from the most relevant frameworks and models analyzed through the scoping review [83,87,89,90,92,94,95,96,102,105]. This typology is organized by vision, political ideology, paradigm, discourse, principles, types of governance and democracy, and political action domains. Supplemental Figure S1 presents the 36 graphic frameworks and models analyzed to develop the food systems typology. Table 3 defines key constructs analyzed and used to develop the food systems governance typology.

Figure 1.

A governance typology with strategies to maintain or transform diets and food systems to be sustainable and regenerative for people, ecosystems, and planetary health.

The graphic food systems governance typology has two contrasting visions. The first vision is to support a food systems governance model that prioritizes economic growth to maintain the current global, national, and local food systems through marketplace and institutional political actions. The second vision is a food system governance model that prioritizes post-economic growth and degrowth to transform global, national, and local food systems for people, animals, the environment, and the planet through communities empowered by individual and collective political actions. The typology is grounded in four distinct political ideologies (i.e., neoliberal, reformist, progressive, and radical); paradigms (i.e., maintain, reform, transition, and transform); discourses (i.e., food enterprise, food security, food justice, and food sovereignty); and types of governance (i.e., multistakeholder, co-governance, shared governance and self-governance); and democracy (i.e., representative, participatory and deliberative).

The neoliberal ideology maintains, and a reformist ideology makes small incremental changes to the current food systems that prioritize economic growth to maintain the current global, regional, national, and local food systems through marketplace and institutional political actions. The food enterprise and food security paradigms prioritize economic growth, resource extraction, increased consumption, and wealth accumulation [29,53].

The progressive political ideology aims to transition toward healthy, sustainable diets and regenerative food systems for people, ecosystems, and planetary health. A radical political ideology fosters an alternative agroecological paradigm to transform food systems to be healthy, equitable, resilient, and regenerative for people and animals to support ecosystems and planetary health. These latter two approaches are supported by the principles of economic sufficiency and degrowth, resource regeneration, reduced consumption, wealth distribution, community ownership, equity, transparency, inclusivity, adaptiveness, and responsiveness [29].

This typology aligns with the perspective of Anderson and Rivera-Ferre (2021) [53], who described contrasting views based on an extractive food system narrative influenced by a neoliberal political ideology, in contrast to a regenerative food system narrative led by a food sovereignty discourse and grounded in agroecological principles and practices. The proposed food systems governance typology is adapted from Lorenzini (2019) [95] and has three types of democracy (i.e., representative, participatory, and deliberative) across four political action domains [24]. Democratic principles and processes (i.e., responsibility, plurality, collaboration, and openness) have been proposed to guide transformative food systems research and practice [126].

4.1. Strategies to Drive Social and Political Change

Advocacy and activism may help to democratize multilateral and multistakeholder governance approaches and address complex food systems challenges [39]. Lorenzini (2019) described types of food activism and citizens’ democratic engagement with food systems organized by different political actions [95]. Figure 1 shows different strategies to drive social change movements across political action domains. Examples of marketplace politics are consumers using boycotts or buycotts as a form of political consumerism to influence marketplace norms and practices. Institutional politics encourage citizens to vote to support candidates who advance legislation that represents their interests, views, and values. Individual protest politics are shown by citizens who donate money or sign petitions to change corporate or government decisions, policies, and laws. Collective protest politics is a form of civil disobedience when citizens unite to participate in street protests as committed activists to change unjust government or corporate decisions, policies, and laws [95].

Swinburn et al. (2019) [11] proposed that philanthropic entities invest financially in supporting civil society organizations to strengthen advocacy for complementary policy actions to tackle the Global Syndemic of undernutrition, obesity, and climate change. There is a need to examine how advocacy and activism strategies that use different forms of participatory governance and deliberative democracy may encourage public discourse and actor accountability to change the power concentration of transnational food and beverage firms that influence political agenda setting and policies that negatively impact people, animals, ecosystems, and the planet [127,128,129]. There is a need to build alliances among diverse constituencies to support democratically driven food justice and food sovereignty movements across different settings, as well as how to use the legislative and legal systems to advance goals [129,130]. This governance framework may assist researchers and civil society organizations to monitor progress toward governance indicators (i.e., shared vision and strategic planning, effective implementation, and accountability) for the Food Systems 2030 Countdown Initiative that emerged from the 2021 UN Food Systems Summit [8,131]. Future research could explore how change agents may use different advocacy and activism strategies across this food systems governance typology to drive social and political changes to support sustainable healthy diets, regenerative food systems, and planetary health.

4.2. Study Strengths and Limitations

A study strength was the broad interdisciplinary evidence examined to describe food systems governance at various scales, levels, and contexts. This study had several limitations. As an exploratory study, we did not conduct a comprehensive critical review or systematic evidence review of food systems governance. Several reviews were published in 2023 that we cited in this paper, but these did not offer insights into graphic frameworks and models or all constructs (i.e., types of political ideologies, governance approaches, and democracy) that have been linked to social change. Another limitation was that we may not have identified all potential governance frameworks or models published in the grey literature that discussed different concepts that are important to consider for the future applications of this governance typology. Another limitation was the focus on selected constructs that influence governance through social change movements and political processes. An in-depth analysis of advocacy or activism strategies to address power inequities among actors was beyond the scope of this study. Finally, this paper did not examine the political economy considerations needed for food systems transformation that have been addressed by other investigators [132].

5. Conclusions

Existing food systems typologies enable decision-makers to analyze food system challenges but do not explicitly examine or illustrate different governance approaches to transform food systems. This paper summarized the findings for a scoping review of graphic food systems governance frameworks and models to develop a proof-of-concept graphic food systems governance typology that could be applied to understand how existing unsustainable diets and food systems are maintained or reformed and how governance approaches may support food systems transition and transformation. Given the concurrent challenges of unsustainable and unhealthy food systems manifested by the Global Syndemic [11], future research could use this food systems governance typology to examine how change agents may use various forms of traditional and digital advocacy and activism to transform food systems, and the acceptability and effectiveness of these strategies. Examples of advocacy and activism include consumer boycotts or buycotts, citizens voting for candidates who represent their interests and values, citizens donating money or signing petitions to change corporate and government policies and practices, and citizens engaging in civil disobedience such as participating in mass street protests to change socially and environmentally unjust government policies and practices. Taken together, these strategies may help to drive social and political change movements that will shift the paradigm and discourse and encourage shared governance approaches to advance sustainable healthy diets, regenerative food systems, and planetary health.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su16041469/s1. Figure S1: Graphic frameworks and models analyzed to develop the food systems governance typology (n = 36). Table S1: Evidence for food system governance frameworks and models used to develop the typology with strategies to maintain, reform, transition, or transform food systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.I.K. and K.L.N. methodology, V.I.K.; formal analysis, V.I.K. and K.L.N.; writing—original draft preparation, V.I.K.; writing—review and editing, V.I.K. and K.L.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

V.I.K. received partial funding from the Department of Human Nutrition, Foods, and Exercise at Virginia Tech to support a staff salary to complete this paper. V.I.K. and K.L.N. did not receive funding from commercial or private-sector entities to support this manuscript. The Department of Human Nutrition, Foods, and Exercise and the Department of Agriculture, Leadership, and Community Education in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences at Virginia Tech provided funding to enable open access publishing.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The supplemental evidence used in Table S1 and Figure S1 upon which the primary literature was analyzed and synthesized are available upon request.

Acknowledgments

We thank Juan Quirarte for designing the figure. We are grateful to Cozette Comer, Research Librarian at Virginia Tech, for guidance on designing and implementing the search strategy for this scoping review; and thank Paige Harrigan and Eranga Galappaththi for their input on the study design and search process. We appreciate the insightful comments provided by Molly Anderson on an earlier draft of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

V.I.K. and K.L.N. have no conflicts of interest related to the content of this manuscript.

References

- Center for Global Commons. Safeguarding the Global Commons for Human Prosperity and Environmental Sustainability; The Global Commons Stewardship Framework: A Discussion Paper; Sustainable Development Solutions Network: New York, NY, USA, 2022; Available online: https://resources.unsdsn.org/safeguarding-the-global-commons-for-human-prosperity-and-environmental-sustainability (accessed on 4 February 2024).

- Clark, H. Governance for planetary health and sustainable development. Lancet 2015, 386, e39–e41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- FAO; IFAD; UNICEF; World Food Programme; World Health Organization (WHO). The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2023. Urbanization, Agrifood Systems Transformation and Healthy Diets Across the Rural-Urban Continuum; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2023; Available online: https://www.fao.org/documents/card/en/c/cc3017en (accessed on 4 February 2024).

- United Nations. Food Systems Transformation: Transforming Food Systems for a Sustainable World without Hunger; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2023; Available online: https://hlpf.un.org/sites/default/files/2023-09/Food%20Systems%20Transformation%20Brochure.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2024).

- United Nations Environmental Program (UNEP); Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO); United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Rethinking Our Food Systems: A Guide for Multi-Stakeholder Collaboration; United Nations Environmental Program (UNEP): Nairobi, Kenya; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy; United Nations Development Programme (UNDP): New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO; WHO. UN Decade of Action Secretariat. United Nations Decade of Action on Nutrition, 2016–2025: Mid-Term Review; Foresight Paper; 2020. Available online: https://www.unscn.org/en/topics/un-decade-of-action-on-nutrition?idnews=2038 (accessed on 4 February 2024).

- United Nations. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2023: Special Edition. Towards a Rescue Plan for People and Planet; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2023; Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2023/The-Sustainable-Development-Goals-Report-2023.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2024).

- The Food Systems Countdown Initiative. The Food Systems Countdown Report 2023: The State of Food Systems Worldwide; Columbia University: New York, NY, USA; Cornell University: Ithaca, NY, USA; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy; Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN): Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Nutrition Report. Global Nutrition Report: Stronger Commitments for Greater Action; Development Initiatives: Bristol, UK, 2022; Available online: https://globalnutritionreport.org/reports/2022-global-nutrition-report/ (accessed on 4 February 2024).

- Anderson, M.D. AFHVS 2020 presidential address: Pushing beyond the boundaries. Agric. Hum Values 2021, 38, 607–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swinburn, B.A.; Kraak, V.I.; Allender, S.; Atkins, V.J.; Baker, P.I.; Bogard, J.R.; Brinsden, H.; Calvillo, A.; De Schutter, P.O.; Devarajan, R.; et al. The global syndemic of obesity, undernutrition, and climate change: The Lancet Commission report. Lancet 2019, 393, 791–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesbroek, S.; Kok, F.J.; Tufford, A.R.; Bloem, M.W.; Darmon, N.; Drewnowski, A.; Fan, S.; Fanzo, J.; Gordon, L.J.; Hu, F.B.; et al. Toward healthy and sustainable diets for the 21st century: Importance of sociocultural and economic considerations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2219272120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrée, P.; Clark, J.K.; Levkoe, C.Z.; Lowitt, K.; Johnston, C. The governance engagement continuum: Food movement mobilization and the execution of power through governance arrangements. In Civil Society and Social Movements in Food System Governance; Andrée, P., Clark, J.K., Levkoe, C.Z., Lowitt, K., Eds.; 2019; pp. 19–42. Available online: http://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/25951 (accessed on 4 February 2024).

- Brown, T.M.; Fee, E. Social movements in health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2014, 35, 385–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvanathan, H.P.; Jetten, J. From marches to movements: Building and sustaining a social movement following collective action. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2020, 35, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, P.; Lacy-Nichols, J.; Williams, O.; Labonte, R. The political economy of healthy and sustainable food systems: An introduction to a special issue. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2021, 10, 734–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems (IPES-Food) and ETC Group. A Long Food Movement: Transforming Food Systems by 2045; 2021; Available online: https://www.ipes-food.org/_img/upload/files/LongFoodMovementEN.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2024).

- Margulis, M. The global governance of food security. In Handbook of Inter-Organizational Relations; Koops, J., Biermann, R., Eds.; Palgrave: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friel, S.; Baker, P.; Lee, J.; Nisbett, N.; Buse, K. Global Governance for Nutrition and the Role of the UNSCN; United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2017; Available online: https://www.unscn.org/uploads/web/news/GovernPaper-EN-WEB-.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2024).

- Canfield, M.C.; Duncan, J.; Claeys, P. Reconfiguring food systems governance: The UNFSS and the battle over authority and legitimacy. Development 2021, 64, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guijt, J.; de Steenhuijsen Piters, B.; Smaling, E. Transforming Food Systems Governance for Healthy, Inclusive and Sustainable Food Systems; Wageningen University & Research: Wageningen, The Nederlands, 2021; Available online: https://edepot.wur.nl/554386 (accessed on 4 February 2024).

- Hospes, O.; Brons, A. Food system governance: A systematic literature review. In Food Systems Governance: Challenges for Justice, Equality and Human Rights; Kennedy, A., Liljeblad, J., Eds.; Routeledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; Available online: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9781315674957-2/food-system-governance-otto-hospes-anke-brons (accessed on 4 February 2024).

- Freeden, M. Ideology: Political Aspects. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences; Smelser, N.J., Baltes, P.B., Eds.; Pergamon: Oxford, UK, 2001; pp. 7174–7177. [Google Scholar]

- Curato, N.; Dryzek, J.S.; Ercan, S.A.; Hendriks, C.M.; Niemeyer, S. Twelve key findings in deliberative democracy research. Dædalus J. Am. Acad. Arts Sci. 2017, 146, 28–38. Available online: https://www.amacad.org/daedalus/prospects-limits-deliberative-democracy (accessed on 4 February 2024). [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.D. Expanding food democracy: A perspective from the United States. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1144090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, S.; Gale, F.; Adams, D.; Dalton, L. A scoping review of the conceptualisations of food justice. Public Health Nutr. 2023, 26, 725–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levkoe, C.Z. Learning democracy through food justice movements. Agric. Hum. Values 2006, 23, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M.S.; Cochrane, A.; Hopma, J. Democratising food: The case for a deliberative approach. Rev. Int. Stud. 2020, 46, 435–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGreevy, S.R.; Rupprecht, C.D.; Niles, D.; Wiek, A.; Carolan, M.; Kallis, G.; Kantamaturapoj, K.; Mangnus, A.; Jehlička, P.; Taherzadeh, O.; et al. Sustainable agrifood systems for a post-growth world. Nat. Sustain. 2022, 5, 1011–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, C. New geographical directions for food systems governance research. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2022, 47, 66–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, K.J. An Independent Dialogues Special Synthesis Report: Food Systems Governance. In Blue Marble Evaluation; 2021; Available online: https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/2021/12/fssd_deepdive_governance.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2024).

- Bump, J. Undernutrition, obesity and governance: A unified framework for upholding the right to food. BMJ Glob. Health 2018, 3, e000886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Valle, M.M.; Shields, K.; Alvarado Vázquez Mellado, A.S.; Boza, S. Food governance for better access to sustainable diets: A review. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6, 784264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thow, A.M.; Ravuvu, A.; Iese, V.; Farmery, A.; Mauli, S.; Wilson, D.; Farrell, P.; Johnson, E.; Reeve, E. Regional governance for food system transformations: Learning from the Pacific Island region. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, A.; Queiroz, C.; Deutsch, L.; González-Mon, B.; Jonell, M.; Pereira, L.; Sinare, H.; Svedin, U.; Wassénius, E. Reframing the local-global food systems debate through a resilience lens. Nat. Food 2023, 4, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrobaish, W.S.; Vlerick, P.; Luning, P.A.; Jacxsens, L. Food safety governance in Saudi Arabia: Challenges in control of imported food. J. Food Sci. 2021, 86, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeon, N. Global food governance. Development 2021, 64, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partelow, S.; Asif, F.; Béné, C.; Bush, S.; Manlosa, A.O.; Nagel, B.; Schlüter, A.; Chadag, V.M.; Choudhury, A.; Cole, S.M.; et al. Aquaculture governance: Five engagement arenas for sustainability transformation. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2023, 65, 101379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, K.E.; Quinn, C.E.; English, C.; Quinn, J.E. Relational values in agroecosystem governance. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2018, 35, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebinck, A.; Zurek, M.; Achterbosch, T.; Forkman, B.; Kuijsten, A.; Kuiper, M.; Nørrung, B.; Veer, P.V.; Leip, A. A sustainability compass for policy navigation to sustainable food systems. Glob. Food Secur. 2021, 29, 100546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, D.; Kalfagianni, A. The causes and consequences of private food governance. Bus. Politics 2010, 12, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorado, D.; Monsalve, S.; Naik, A.; Suárez, A.M. Towards building comprehensive legal frameworks for corporate accountability in food governance. Development 2021, 64, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems (IPES)-Food. Whose Tipping the Scales? The Growing Influence of Corporations on the Governance of Food Systems, and How to Counter It; 2023; Available online: http://www.ipes-food.org/pages/tippingthescales (accessed on 4 February 2024).

- Patay, D.; Ralston, R.; Palu, A.; Jones, A.; Webster, J.; Buse, K. Fifty shades of partnerships: A governance typology for public private engagement in the nutrition sector. Glob. Health 2023, 19, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, S.; Costa, I.; de Schutter, O.; Dedeurwaerdere, T.; Hudon, M. Systemic ethics and inclusive governance: Two key prerequisites for sustainability transitions of agri-food systems. Agric. Hum. Values 2019, 36, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Alliance for the Future of Food. Principles for Food Systems Transformation: A Framework for Action; 2021; Available online: https://futureoffood.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/GA_PrinciplesDoc.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2024).

- Hawkes, C.; Ambikapathi, R.; Anastasiou, K.; Brock, J.; Castronuovo, L.; Fallon, N.; Malapit, H.; Ndumi, A.; Samuel, F.; Umugwaneza, M.; et al. From food price crisis to an equitable food system. Lancet 2022, 400, 413–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD). Transforming Agri-Food Systems via Inclusive Rights-Based Governance; 2023; Available online: https://sdg.iisd.org/commentary/guest-articles/transforming-agri-food-systems-via-inclusive-rights-based-governance/ (accessed on 4 February 2024).

- United Nations (UN) Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights. Good Governance; 2022; Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/en/good-governance/about-good-governance (accessed on 4 February 2024).

- Wilkes, J. Reconnecting with nature through good governance: Inclusive policy across scales. Agriculture 2022, 12, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations. Agroecology Knowledge Hub. Responsible Governance: Sustainable Food and Agriculture Requires Responsible and Effective Governance Mechanisms at Different Scales—From Local to National to Global. 2024. Available online: https://www.fao.org/agroecology/knowledge/10-elements/land-natural-resources-governance/en/ (accessed on 4 February 2024).

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations. Strategic Framework 2022–2031; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2021; Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/cb7099en/cb7099en.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2024).

- Medina-García, C.; Nagarajan, S.; Castillo-Vysokolan, L.; Béatse, E.; Van den Broeck, P. Innovative multi-actor collaborations as collective actors and institutionalized spaces. The case of food governance transformation in Leuven (Belgium). Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 5, 788934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.D.; Rivera-Ferre, M. Food system narratives to end hunger: Extractive versus regenerative. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2021, 49, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sayed, S.; Cloutier, S. Weaving disciplines to conceptualize a regenerative food system. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2022, 11, 23–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loring, P.A. Regenerative food systems and the conservation of change. Agric. Hum. Values 2020, 39, 701–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Food and Land Coalition. Growing Better: Ten Critical Transitions to Transform Food and Land Use; 2019; Available online: https://www.foodandlandusecoalition.org/global-report/ (accessed on 4 February 2024).

- Wigboldus, S. On Food System Transitions & Transformations: Wageningen Centre for Development Innovation; Report WCDI-20-125; Wageningen University: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2020; Available online: https://research.wur.nl/en/publications/on-food-system-transitions-amp-transformations-comprehensive-mapp (accessed on 4 February 2024).

- World Economic Forum. Incentivizing Food Systems Transformation; 2020; Available online: https://www.weforum.org/reports/incentivizing-food-systems-transformation/ (accessed on 4 February 2024).

- Doherty, B.; Bryant, M.; Denby, K.; Fazey, I.; Bridle, S.; Hawkes, C.; Cain, M.; Banwart, S.; Collins, L.; Pickett, K.; et al. Transformations to regenerative food systems: An outline of the FixOurFood project. Nutr. Bull. 2022, 47, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaplowe, S.G.; Hejnowicz, A.; Laeubli Loud, M. Evaluation as a pathway to transformation lessons from sustainable development. In The Palgrave Handbook of Learning for Transformation; Nicolaides, A., Eschenbacher, S., Buergelt, P.T., Gilpin-Jackson, Y., Welch, M., Misawa, M., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 785–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobratee, N.; Davids, R.; Chinzila, C.B.; Mabhaudhi, T.; Scheelbeek, P.; Modi, A.T.; Dangour, A.D.; Slotow, R. Visioning a food system for an equitable transition towards sustainable diets—A South African perspective. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béné, C.; Oosterveer, P.; Lamotte, L.; Brouwer, I.D.; de Haan, S.; Prager, S.D.; Talsma, E.F.; Khoury, C.K. When food systems meet sustainability—Current narratives and implications for actions. World Dev. 2019, 113, 116–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benton, T.G.; Harwatt, H. Sustainable Agriculture and Food Systems: Comparing Contrasting and Contested Versions; Chatham House Research Paper; 2022; Available online: https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/2022-05/2022-05-24-sustainable-agriculture-benton-harwatt_4.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2024).

- Cambridge University Dictionary. Vision. 2023. Available online: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/us/dictionary/learner-english/vision (accessed on 4 February 2024).

- IGI Global. What Is a Paradigm? 2023; Available online: https://www.igi-global.com/dictionary/paradigm/21815 (accessed on 4 February 2024).

- Fairclough, N. Discourse and Social Change; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambridge University Dictionary. Narrative. 2023. Available online: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/learner-english/narrative (accessed on 4 February 2024).

- Kraak, V.I. Advice for food systems governance actors to decide whether and how to engage with the agri-food and beverage industry to address malnutrition within the context of healthy and sustainable food systems. Comment on “challenges to establish effective public-private partnerships to address malnutrition in all its forms”. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2022, 11, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO); World Health Organization. Sustainable Healthy Diets—Guiding Principles; FAO: Rome, Italy; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/ca6640en/ca6640en.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2024).

- Ingram, J. Food system models. In Healthy and Sustainable Food Systems; Lawrence, M., Friel, S., Eds.; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- High Level Panel of Experts (HLPE). Nutrition and food systems. In A Report by the High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition of the Committee on World Food Security; HLPE Report 12; Rome, Italy, 2017; Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/i7846e/i7846e.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2024).

- Downs, S.M.; Ahmed, S.; Fanzo, J.; Herforth, A. Food environment typology: Advancing an expanded definition, framework, and methodological approach for improved characterization of wild, cultivated, and built food environments toward sustainable diets. Foods 2020, 9, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogard, J.R.; Andrew, N.L.; Farrell, P.; Herrero, M.; Sharp, M.K.; Tutuo, J. A typology of food environments in the Pacific region and their relationship to diet quality in Solomon Islands. Foods 2021, 10, 2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanzo, J.; Haddad, L.; McLaren, R.; Marshall, Q.; Davis, C.; Herforth, A.; Jones, A.; Beal, T.; Tschirley, D.; Bellows, A.; et al. The Food Systems Dashboard is a new tool to inform better food policy. Nat. Food 2020, 1, 243–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, Q.; Fanzo, J.; Barrett, C.B.; Jones, A.D.; Herforth, A.; McLaren, R. Building a global food systems typology: A new tool for reducing complexity in food systems analysis. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 746512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herforth, A.; Bellows, A.L.; Marshall, Q.; McLaren, R.; Beal, T.; Nordhagen, S.; Remans, R.; Estrada Carmona, N.; Fanzo, J. Diagnosing the performance of food systems to increase accountability toward healthy diets and environmental sustainability. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0270712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.J.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchanan, A.; Keohane, R.O. The legitimacy of global governance institutions. Ethics Int. Aff. 2006, 20, 405–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, P.; Demaio, A. The political economy of healthy and sustainable food systems. In Healthy and Sustainable Food Systems; Lawrence, M., Friel, S., Eds.; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2019; pp. 181–192. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Q.; Knickel, K.; Tesfai, M.; Sumelius, J.; Turinawe, A.; Emegu Isoto, R.; Medyna, G. A framework for assessing food systems governance in six urban and peri-urban regions in Sub-Saharan Africa. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 763352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, J.K.; Lowitt, K.; Levkoe, C.Z.; Andrée, P. The power to convene: Making sense of the power of food movement organizations in governance processes in the Global North. Agric. Hum. Values 2021, 38, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cullerton, K.; Donnet, T.; Lee, A.; Gallegos, D. Effective advocacy strategies for influencing government nutrition policy: A conceptual model. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2018, 15, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delaney, A.; Evans, T.; McGreevy, J.; Blekking, J.; Schlachter, T.; Korhonen-Kurki, K.; Tamás, P.A.; Crane, T.A.; Eakin, H.; Förch, W.; et al. Governance of food systems across scales in times of social-ecological change: A review of indicators. Food Secur. 2018, 10, 287–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friel, S.; Townsend, B.; Fisher, M.; Harris, P.; Freeman, T.; Baum, F. Power and the people’s health. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 282, 114173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunaratne, M.S.; Radin Firdaus, R.B.; Rathnasooriya, S.I. Climate change and food security in Sri Lanka: Towards food sovereignty. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2021, 8, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herens, M.C.; Pittore, K.H.; Oosterveer, P.J.M. Transforming food systems: Multi-stakeholder platforms driven by consumer concerns and public demands. Glob. Food Secur. 2022, 32, 100592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt Giménez, E.; Shattuck, A. Food crises, food regimes and food movements: Rumblings of reform or tides of transformation? J. Peasant Stud. 2011, 38, 109–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Roggio, A.M.; Luna-Reyes, L.F. Governance of local food systems: Current research and future directions. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 338, 130626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawasaki, N. Analysis of entrepreneurship and multisectoral farm business development: Chapter 2. In Entrepreneurship and Innovation in Japanese Agriculture. New Frontiers in Regional Science: Asian Perspectives; Kiminami, A., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; Volume 32, pp. 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, M.A.; Friel, S.; Wingrove, K.; James, S.W.; Candy, S. Formulating policy activities to promote healthy and sustainable diets. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 2333–2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeuwis, C.; Boogaard, B.K.; Atta-Krah, K. How food systems change (or not): Governance implications for system transformation processes. Food Secur. 2021, 13, 761–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Cifuentes, M.; Gugerell, C. Food democracy: Possibilities under the frame of the current food system. Agric. Hum. Values 2021, 38, 1061–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzini, J. Food activism and citizens’ democratic engagements: What can we learn from market-based political participation? Politics Gov. 2019, 7, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano-Cabedo, C.; Gómez-Benito, C. A theoretical model of food citizenship for the analysis of social praxis. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2017, 30, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisbett, N.; Harris, J.; Backholer, K.; Baker, P.; Jernigan, V.B.B.; Friel, S. Holding no-one back: The nutrition equity framework in theory and practice. Glob. Food Secur. 2022, 32, 100605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oñederra-Aramendi, A.; Begiristain-Zubillaga, M.; Cuellar-Padilla, M. Characterisation of food governance for alternative and sustainable food systems: A systematic review. Agric. Econ. 2023, 11, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruben, R.; Cavatassi, R.; Lipper, L.; Smaling, E.; Winters, P. Towards food systems transformation-five paradigm shifts for healthy, inclusive and sustainable food systems. Food Secur. 2021, 13, 1423–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudnick, J.; Niles, M.; Lubell, M.; Cramer, L. A comparative analysis of governance and leadership in agricultural development policy networks. World Dev. 2019, 117, 112–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Termeer, C.J.A.M.; Drimie, S.; Ingram, J.; Pereira, L.; Whittingham, M.J. A diagnostic framework for food system governance arrangements: The case of South Africa. NJAS Wagening. J. Life Sci. 2018, 84, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tribaldos, T.; Kortetmäki, T. Just transition principles and criteria for food systems and beyond. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2022, 43, 244–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Gaast, K.; van Leeuwen, E.; Wertheim-Heck, S. Food systems in transition: Conceptualizing sustainable food entrepreneurship. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2021, 20, 705–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wezel, A.; Herren, B.G.; Kerr, R.B.; Barrios, E.; Gonçalves, A.L.R.; Sinclair, F. Agroecological principles and elements and their implications for transitioning to sustainable food systems. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 40, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitfield, S.; Apgar, M.; Chabvuta, C.; Challinor, A.; Deering, K.; Dougill, A.; Gulzar, A.; Kalaba, F.; Lamanna, C.; Manyonga, D.; et al. A framework for examining justice in food system transformations research. Nat. Food 2021, 2, 383–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations. Developing Sustainable Food Value Chains—Guiding Principles; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2014; Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/i3953e/i3953e.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2024).

- FAO. The Rights to Food and the Responsible Governance of Tenure—A Dialogue Towards Implementation; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2014; Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/i3170e/i3170e.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2024).

- FAO. Sustainable Food Systems: Concept and Framework; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2018; Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/ca2079en/CA2079EN.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2024).

- FAO. The 10 Elements of Agroecology: Guiding the Transition to Sustainable Food and Agricultural Systems; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2019; Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/i9037en/i9037en.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2024).

- FAO. The White Paper on Indigenous People’s Food Systems; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2021; Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/cb4932en/cb4932en.pdf (accessed on 6 February 2024).

- Hawkes, C. Taking a Food Systems Approach to Policymaking: What, How, and Why; Centre for Food Policy, City University of London: London, UK, 2022; Available online: https://r4d.org/wp-content/uploads/R4D-CITY-Food-Systems-Approach-Brief-1.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2024).

- One Planet and United Nations [UN] Environment Programme. Collaborative Framework for Food Systems Transformation: A Multi-Stakeholder Pathway for Sustainable Food Systems. 2019. Available online: https://www.oneplanetnetwork.org/knowledge-centre/resources/collaborative-framework-food-systems-transformation-multi-stakeholder (accessed on 4 February 2024).

- The World Bank; FAO; RUAF Foundation. Urban Food Systems Diagnostic and Metrics Framework. 2017. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/807971522102099658/pdf/Urban-food-systems-diagnostic-and-metrics-framework-roadmap-for-future-geospatial-and-big-data-analytics.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2024).

- The World Bank. Food Finance Architecture: Financing a Healthy, Equitable, and Sustainable Food System; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/agriculture/publication/food-finance-architecture-financing-a-healthy-equitable-and-sustainable-food-system (accessed on 4 February 2024).

- UN Sustainable Development Group. UN Sustainable Development Cooperation Framework; 2022; Available online: https://unsdg.un.org/2030-agenda/cooperation-framework (accessed on 4 February 2024).

- Wood, M.S.; Palmer, J.; Mason-D’Croz, D.; Bogard, J.; McMillan, L.; Hall, A.; Juliano, P.; Battaglia, M.; Herrero, M. CSIRO Convened United Nations Food Systems Summit Dialogue: Achieving Healthy Diets from Sustainable Food Systems by 2030—What Key Science, Innovation and Actions Are Needed in Australia? Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO): Brisbane, Australia, 2022. [CrossRef]

- High Level Panel of Experts (HLPE) on Food Security and Nutrition. Food Security and Nutrition: Building a Global Narrative towards 2030; A Report by the High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition of the Committee on World Food Security; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020; Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/ca9731en/ca9731en.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2024).

- Paulson, L.; Büchs, M. Public acceptance of post-growth: Factors and implications for post-growth strategy. Futures 2022, 143, 103020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, S.; Baker, P.; Lawrence, M. An analysis of the transformative potential of major food system report recommendations. Glob. Food Secur. 2022, 32, 100610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]