Abstract

Virtual brand communities are one of the most important ways for companies to strengthen ties with consumers and cultivate brand loyalty. Consumers, as the main participants of virtual brand communities, play an important role in their own literacy for the healthy and sustainable development of the communities. This study explores the connotation and structure of consumer literacy in virtual brand communities from the perspective of consumers, and develops and tests a scale. First, based on relevant literature, case studies, and semi-structured in-depth interviews with 38 consumers who have browsed virtual brand communities, the study defined the concept of consumer literacy and qualitatively summarized the potential dimensions. The study then used the SPSS26.0 and AMOS24.0 software to analyze the data obtained from the questionnaire survey, and combined the methods of exploratory factor analysis, confirmatory factor analysis, and nomological validity analysis to identify the three dimensions of consumer literacy in the virtual brand community, including brand knowledge, engagement skills, and conceptual knowledge, and obtained a scale with good reliability and validity. The results provide a measurement tool for the study of consumer literacy in virtual brand communities and a scientific basis for further improving the management of the communities.

1. Introduction

With the continuous development of digital information technology, more and more companies are setting up their own virtual brand communities to establish social connections with consumers [1]. Companies utilize virtual brand communities to allow consumers to co-create value through interaction, obtain information useful to them, and thus, improve relationship quality and brand loyalty [2]. Consumers are attracted by virtual brand communities and take the initiative to participate in innovative activities such as product design, product development, and product feedback [3]. Taking the Xiaomi community as an example, as of March 2023, the monthly activity of the global and mainland China MIUI communities has grown to 595 million and 146 million, respectively, of which the number of postings in each cell phone circle has broken 10,000. Many consumers are active in the circles they are interested in, exchanging and communicating by posting, wanting to create value for themselves.

However, although virtual brand communities inspire consumers to participate in brand communication and interaction, not all consumers are able to use the resources provided by the platform for positive interaction. As the main participant of the community, consumers, for their own reasons, lack the ability to use the resources provided by themselves or the enterprise, resulting in negative interactions that may lead to the co-destruction of value [4]. This not only violates the original intention of the enterprise that wants to maintain a good customer–enterprise relationship and co-create value, but also may produce negative information about the brand to be transmitted to more consumers, forming a potential threat and damaging the brand’s reputation [5]. Companies have also tried to take some measures, such as setting access questions and sending brand information text messages to improve consumer awareness of the brand. Thus, it can be seen that consumers’ personal literacy plays a key role in establishing and maintaining the relationship between consumers and companies [6,7]. Consumers with low literacy tend to face more difficulties, more decision-making biases, and lower satisfaction in the interaction process [7]. In the long run, consumer literacy (CL) is very important for realizing the sustainable development of brand communities. In the new era, the goal of sustainable development of virtual brand communities is not trivial [8]. Therefore, understanding and improving CL in virtual brand communities is an important issue for brand community managers who are committed to creating value with their consumers.

Currently, there is a lack of academic research on the concept of CL. Although scholars have defined and studied CL in different research contexts [9,10,11], most of these studies are based on conceptual discussions only and lack the scales needed for empirical research, which makes it impossible to carry out in-depth studies that can be operationalized subsequently. In addition, although some scholars have proposed the concepts of “marketplace literacy” [12], “financial literacy” [13], “information literacy” [14], and other concepts around the concept of “literacy” and conducted empirical studies, these concepts focus on different levels and are not the same as the concept of CL. So if they are directly used to analyze CL in the context of virtual brand communities, it is inevitable that there will be a problem of “incompatibility”. As a new type of online platform community, no scholars have paid attention to CL in the context of virtual brand communities, and there is a lack of exploration of its conceptual connotation and structural dimensions, as well as no relevant measurement scale. If this problem is not solved, the research on CL in the context of virtual brand communities cannot be carried out in depth. In order to further meet the needs of CL research, the study of CL is broadened to the field of virtual brand communities to make up for the existing deficiencies. From the perspective of consumers, this study explores the constituent dimensions of CL in virtual brand communities, develops a measurement scale for CL, provides an operationalized measurement tool for empirical research on CL in virtual brand communities, and provides a scientific basis for promoting enterprise managers to improve CL in virtual brand communities.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. The Connotation of Virtual Brand Communities

Virtual brand communities are a new type of brand community born with the rapid development of Internet technology, in which consumers communicate information, express their views and opinions, and express their love for a specific brand [15]. At present, many scholars have conducted rich exploratory studies on virtual brand communities, but have not yet reached a consensus on the definition of the concept of virtual brand communities. Kozinets [16] first defined the concept of the virtual brand community, which, according to him, is an online platform for members to communicate brand experiences and share brand attitudes. The study by Amine and Sitz [17] points out that a virtual brand community is a platform for brand experience and sharing of brand knowledge, values, etc., among enthusiasts of the same brand online, without geographical restrictions, using Internet technology. There are two main types of virtual brand community, the first one is initiated and established by companies [18], where members can exchange relevant content about the brand on the platform provided by the company. The second type is freely formed by brand enthusiasts or third parties [19], an online community that is not limited by geographical scope based on social relationships among consumers [20]. The object of this paper is a company-initiated virtual brand community, which is created by a company to establish and maintain social connections with consumers and potential consumers, so as to obtain timely and effective feedback from consumers on brand products or services [21]. Among the studies on virtual brand communities that have been conducted, some scholars have pointed out that virtual brand communities provide excellent conditions for value co-creation. For example, Tang and Jiang [22] argue in their study that value co-creation behavior relies on the environmental characteristics of the platform (e.g., ease of use of technology) and the connection characteristics among consumers (e.g., the interpersonal network established by interaction with each other). Based on the above studies, it can be seen that virtual brand communities have the following points in common: (1) the Internet as a technological tool, free from geographical constraints; (2) interactive communication as a basic form; (3) participants share the same brand preferences; and (4) positive effects on both brand merchants and consumers. Therefore, this study concludes that virtual brand communities are a kind of online co-creation value platform established by companies or brand operators to provide interactive communication for consumers with the same brand preferences. Although virtual brand communities are typical platforms for value co-creation, they also provide opportunities for value co-destruction to occur [23]. Whether communities are value co-creative or co-destructive, the level of consumers’ own literacy plays a key role.

2.2. The Connotation of Consumer Literacy

Literacy is acquired through acquired learning and is the ability of an individual to use information in order to develop knowledge and potential, achieve personal goals, and adapt to society [24], and in essence is the ability to integrate various types of knowledge and skills to adapt to a specific social situation [25]. CL is the combination of the concept of general literacy and the consumer context [26]. There have been studies on CL in which different scholars have presented different views on the definition of the concept. One view is that CL refers to the general cultural literacy that consumers possess, mainly literacy and mathematical skills [27,28], such as information browsing, product price comparison, etc., that consumers may involve in their decision-making process. In these activities, CL plays a direct constraining role in their final decisions [7,24]. Another view considers CL as the knowledge and skills that consumers possess during the consumption process, such as knowing how to obtain product information, knowing how to compare products’ value for money, knowing how to respond to merchants’ promotions, etc. [29,30]. The first view tends to treat CL as general cultural literacy; however, such literacy cannot play a key role in influencing consumers in the process of consumer decision making, i.e., high literacy does not mean that one can have the same knowledge and skills in the consumer domain. Thus, most scholars prefer to investigate the second viewpoint, which further investigates CL as knowledge and skills in the consumption domain. For example, Park et al. [10] define CL as the ability necessary for consumers to consume effectively and rationally in a changing marketplace. Viswanathan et al. [12] directly introduced the concept of “marketplace literacy” in their study of education in poor areas of India, arguing that marketplace literacy is the knowledge and skills necessary for entrepreneurs and consumers to participate in market transactions. Chinedu et al. [11], based on previous studies, further suggest that literate consumers need to have certain cognitive abilities and be able to adopt some protective behaviors to avoid themselves from being cheated during market transactions. The above studies show that although the definition of CL varies slightly among scholars, they all take a goal-oriented approach and consider CL as the knowledge and skills that can help consumers to successfully complete the consumption process.

In addition, CL under the second view is influenced by the research context, and the structure and content of CL vary across contexts. In this view, CL is context-dependent and is influenced by specific consumer contexts or consumer products. For example, the literacy that consumers need to possess when purchasing electronic products online includes knowledge of hardware and software related to electronic products, the ability to search for information about the products, and the ability to defend their rights after purchase [10], while the literacy that consumers need to possess when purchasing financial products includes knowledge of financial risks such as inflation and interest calculation skills [31].

The above studies show that the connotations and dimensions of CL differ in different contexts, and that the concept of CL is different from the concepts of “marketplace literacy” and “financial literacy” mentioned by previous scholars. The concept of “marketplace literacy” emphasizes market transactions and is required for both entrepreneurs and consumers [32]. Marketplace literacy consists of three main types of knowledge and skills, namely, “know-what”, “know-how”, and “know-why”. These refer to basic objective knowledge (e.g., knowing what products to buy), procedural skills (e.g., knowing how to compare product attributes), and conceptual knowledge (e.g., knowing the value of a product). The concept of “financial literacy” focuses on the knowledge and skills in the financial sector [33]. Financial literacy encompasses the dimensions of awareness (understanding of financial concepts), skills (numerical and cognitive abilities), and experience (knowledge of financial products). This paper focuses on CL in virtual brand communities. Referring to the definition of consumer-related literacy in previous studies, this paper defines CL in virtual brand communities as the knowledge and skills that consumers need to possess when navigating virtual brand communities, including understanding brand information, interacting with brand merchants or other consumers, etc.

3. Dimension Exploration of Consumer Literacy in Virtual Brand Communities

There is no research on CL in the context of virtual brand communities in the existing literature, nor has a CL scale been developed. This study uses qualitative analysis such as semi-structured in-depth interviews, a literature analysis, and on-site observation to qualitatively summarize the dimensions of CL in virtual brand communities and generate an initial scale for measuring CL.

Since the CL scale in virtual brand communities should not only inherit the existing research results on CL, but also reflect the characteristics of virtual brand communities and consumers, the initial questions of the scale were obtained in the following three ways: first, we collected and reviewed a large amount of authoritative literature related to CL, and summarized and identified the characteristics and roles of CL from it; then, we read some cases of successful virtual brand communities to understand the behavior of consumers in them, so as to have a basic judgment on the performance of CL; finally, we adopted the method of semi-structured in-depth interviews, and the selection of interviewees was based on gender, age, community browsing experience, occupation, etc. Finally, 38 consumers with extensive browsing experience in the virtual brand community were eventually interviewed, among which 16 were male, accounting for 42.11%; 18 people were aged between 18 and 25 years old, accounting for 47.37%; 10 people were aged between 26 and 35 years old, accounting for 26.32%; 19 people were students, accounting for 50%; and 19 people were various types of workers, including corporate employees, teachers, civil servants, etc.; in terms of education level, 52.63% of the respondents had received undergraduate education, and the remaining 47.37% of the respondents had received a master’s degree or above; in terms of the time of community involvement, 36.84% of the respondents said they had been involved in the community for more than 2 years, 31.58% said they had been involved in the community for between 1 and 2 years, and the remaining 26.32% had been involved in the community for less than 1 year.

The specific interview questions were designed as follows: (1) Now, please recall an impressive experience of participating in a virtual brand community and describe the basic circumstances of the experience, including what information you obtained or contributed, and how it helped you to purchase or use the product. (2) Do you think this experience is related to your own accumulated knowledge and skills? If so, what knowledge and skills do you think helped you? Please describe in detail. (3) What knowledge and skills do you think you need to have in addition to your current knowledge and skills in order to get useful information for yourself in this virtual brand community, and how will these knowledge and skills help you to participate in the community? Please elaborate as much as possible. In addition to focusing on the three questions above, some research-related questions were designed, such as what role do you play in a virtual brand community (listening or advising or managing, etc.)? Overall, what impact do you think your current CL has had on your life? What knowledge and skills do you feel are most important in your daily consumption? What needs to be corrected in the virtual brand communities you currently frequent, etc. All respondents were invited to participate in the survey voluntarily and were informed prior to the interview that the interview data would be used for research purposes only. The paper does not contain any information that could identify the identities of the respondents.

3.1. Extraction and Categorization of Knowledge and Skills

The study began with a content analysis of the interview data obtained, which consisted of approximately 10,000 words, to extract and categorize the knowledge and skills included in CL. Based on the interviewees’ responses, a description of “what knowledge and skills help navigate the community” was obtained. By carefully reading and analyzing the content of each interviewee’s description, we summarized their own experiences in browsing virtual brand communities, and then combined and analyzed the descriptions of similar or overlapping experiences to come up with 5 main categories and 16 sub-categories of knowledge and skills included in CL (as shown in Table 1). “Focused grasp” refers to consumers’ knowledge of how to filter the key information that is useful to them when browsing the virtual brand community, and how important this information is to them, and how they can translate the information that is useful to them into actual use of the product. “Skill mastery” means that consumers know that there are some tips and tricks for using or buying products in the community, and that they can use these tips and tricks to help them use the products more easily or buy them at a better price.

Table 1.

Knowledge and skills categorization of CL in virtual brand communities.

3.2. High-Frequency Vocabulary Extraction

Based on the classification of knowledge and skills included in CL, this study began to extract the high-frequency vocabulary of CL. Then, we used the ROSTCM6 software (professional word frequency statistics software designed and developed by the ROST virtual learning team at Wuhan University) to sort the documents into words, and eliminated the words that were obviously not related to CL in the virtual brand community. Finally, the high-frequency words obtained from the word separation and the initial text content of the interviews were compared, and some words with roughly the same meaning were combined to form the final word frequency statistics (see Table 2), and 20 high-frequency words were selected as the basis for the next analysis.

Table 2.

Vocabulary frequency statistics table.

3.3. Category Construction

Categories or indicators are items and criteria designed to categorize the content of information according to research needs. Mutual exclusion and exhaustion are the two basic principles of constructing categories, and constructing categories means that all units of analysis can be assigned to the corresponding categories, and each unit of analysis can only be assigned to one category [34]. In this study, based on the five main categories and 20 high-frequency words of CL in virtual brand communities summarized in the previous subsection, and combined with the relevant information obtained from the literature analysis, we further analyzed the composition of CL in virtual brand communities and summarized four potential dimensions of CL in virtual brand communities (see Table 3). Basic knowledge is the most basic knowledge that consumers need to have to browse virtual brand communities, with the accumulation of the most basic knowledge, consumers can better grasp the information in virtual brand communities; participation ability is the skills of consumers in participating in virtual brand communities, these skills are a higher level than the basic knowledge, and can help consumers search for information more effectively and protect their rights and interests; professional knowledge and skill knowledge, which were generalized in this study through in-depth interviews, are higher-level knowledge. Consumers with this knowledge will be more aware of the importance of virtual brand communities for themselves and will better understand why their participation in virtual brand communities can lead to greater benefits for them.

Table 3.

Qualitative summary of the components of CL in virtual brand communities.

4. Scale Development of Consumer Literacy in Virtual Brand Communities

4.1. Initial Question Item Generation and Refinement

The process of generating and refining the initial items in this study was as follows: First, based on some previous studies on CL and qualitative research such as in-depth interviews conducted in this paper, we initially obtained 30 items on CL in virtual brand communities [36]. Six master’s degree students from universities with research interests in consumer behavior were invited to merge and delete the initial 30 items in a back-to-back manner. In this process, items that were considered semantically repetitive, contained multiple semantics, and were not related to CL constructs in the virtual brand community were first removed, and those that were inconsistent or uncertain were eliminated after discussion and agreement [37]. A total of 24 items were retained after the initial elimination. After that, four PhD students with extensive experience in virtual brand communities were invited as expert virtual brand community participants to streamline the items based on the same principles, revise and improve the poorly worded, poorly phrased, difficult to answer, and easily confused items to help the respondents understand the items to the greatest extent possible, reduce the cognitive burden of the respondents, and strive to minimize the subsequent measurement errors [38], with 20 measurement items remaining after modification. Finally, two professors in brand management were invited to evaluate the measurement items, mainly to finalize the content validity of the items, including the language and wording of the items, and to revise and improve the form and semantic expression of the measurement items based on their feedback and suggestions [23], finally forming the initial item bank containing 18 measurement items.

4.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis

4.2.1. Distribution and Analysis of Questionnaires

In this study, the questionnaires were distributed online, using a random sampling method, and a link was generated using the Questionnaire Star platform, which was sent to WeChat groups, QQ groups, Douban, and other online social media platforms, and respondents were invited to fill out the questionnaire. The scope of the online survey was mainly in China. At the beginning of the questionnaire, the definition of virtual brand community was introduced, and then the respondents were asked to confirm whether they had ever browsed a virtual brand community, and then they were asked to recall the most impressive browsing experience and answer the items carefully. The items were scored on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree), and each item was a compulsory question that could only be submitted if all the questions were answered, ensuring the integrity of the sample data. A total of 273 questionnaires were collected, 46 wrong answers and invalid questionnaires were deleted, and 227 valid questionnaires were finally obtained, with an effective rate of 83.15%. The basic information characteristics of the valid samples are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Basic information characteristics of the valid samples.

4.2.2. Scale Correction

First, the reliability of each item was determined using the corrected item-total correlation (CITC) coefficient, and the items with insignificant CITCs and correlations less than 0.4 were removed, and the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the scale increased or remained unchanged after the items were removed [39]. Accordingly, the items such as “I can join the brand community I want to join”, “I know how to use the product correctly”, “I know how to post to other consumers for help”, etc., were deleted. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the initial scale for the remaining 12 items was 0.851, indicating that the reliability of the initial scale was high [40]. Next, KMO and Bartlett’s sphere tests were performed on the data of the 12 measures, and the data showed a KMO value of 0.845 and a Bartlett’s sphere test value of 0.000, indicating suitability for factor analysis. Then, the factors were extracted by principal component analysis, the factors were rotated by the method of great variance, and the common factors were extracted according to the criterion of eigenvalues greater than 1. In order to further ensure the simplicity of the scale and the reliability of the items, the items with factor loadings lower than 0.6 and cross-factor loadings more than 0.4 were deleted [41], and the items such as “I know how to participate in corporate-sponsored topics or creative activities” were removed. Two items were deleted, including “I know how to participate in company-initiated topics or creative activities”, and the final number of remaining items was 10. Further exploratory factor analysis was conducted on the remaining 10 items, and a total of three common factors with eigenvalues greater than 1 were extracted (see Table 5 for the names of the factors and corresponding items). Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was used to analyze the reliability of the scale. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the overall scale was 0.853, and the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the three sub-dimensions of brand knowledge, participation skills, and conceptual knowledge were 0.840, 0.799, and 0.850, respectively, which were all greater than 0.7. As an exploratory study, the reliability of the scale was able to meet the needs of the study.

Table 5.

Results of exploratory factor analysis of CL in virtual brand communities.

It should be noted that because the measurement items were refined, the final three factors formed by exploratory factor analysis were different from the potential dimensions of CL previously classified, mainly because the dimensions obtained by previous qualitative generalization crossed over with other dimensions, so in the process of scale purification some dimensions’ measurement items were deleted or merged in order to make the scale concise. Two of the professional knowledge measures and one of the skill knowledge measures were combined into one factor. By analyzing the content of these items, this study concluded that these three items emphasize consumers’ understanding of the importance of the product, i.e., that consumers can understand the value of the product itself into actual use value, and that consumers can maximize the use value they can obtain through their knowledge. Therefore, this study renames this knowledge as conceptual knowledge (conceptual knowledge refers to the in-depth understanding of the interrelationship of knowledge units in market transactions), drawing on Rittle et al. [35]. In addition, since the subject of the study is CL in the virtual brand community, based on existing research [32,33], in order to make the dimensions more appropriate to the research context, the term “basic knowledge” is changed to “brand knowledge” and “ participation ability “ is replaced with “engagement skills”.

In summary, the study initially obtained a CL measurement scale with 10 items and three dimensions (see Table 6). Brand knowledge consists of three items, which mainly cover the basic knowledge related to brand products that consumers need to have in browsing virtual brand communities, which can be acquired through daily learning or life experiences; engagement skills are composed of four items, which are consumers’ ability to perform some process-specific behaviors to complete the browsing of the community or after sales of products, which help consumers better participate in community interacions and protect their rights and interests [42]; conceptual knowledge, as the highest level of CL, is composed of three items, which emphasize consumers’ ability to understand the relationship between the value of a product and its actual use, and to understand the importance of the product to them and to create the most value for themselves.

Table 6.

Dimensions and measures of CL in virtual brand communities.

4.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4.3.1. Data Collection

The measurement scale used for this data collection was revised and refined by exploratory factor analysis, and contained three dimensions and 10 measures in total. At the same time, this research also used a questionnaire on a 7-point Likert scale for consumers who had browsed the virtual brand community. In order to improve the data quality, this research was conducted by modifying the content of the first research Questionnaire Star electronic questionnaire, using the same questionnaire to fill in the link, and adding the restriction that the same IP address can only be used to answer the questionnaire once, which effectively excluded the respondents who had participated in the first questionnaire research. Finally, by excluding the questionnaires that were not filled out carefully, and illogical and other unqualified questionnaires, as well as those with less than 1 min and more than 5 min of response time [43], a total of 203 valid questionnaires were obtained. Of the final respondents, 94 were male, accounting for 46.31%; 142 were aged between 18 and 25, accounting for 69.95%; and 195 had a bachelor’s degree or above, accounting for 96.06%. In terms of the length and frequency of community participation, 71.92% had participated in the community for more than six months, and 87.68% browsed the community for less than one hour each time on average.

4.3.2. Reliability and Validity Analysis

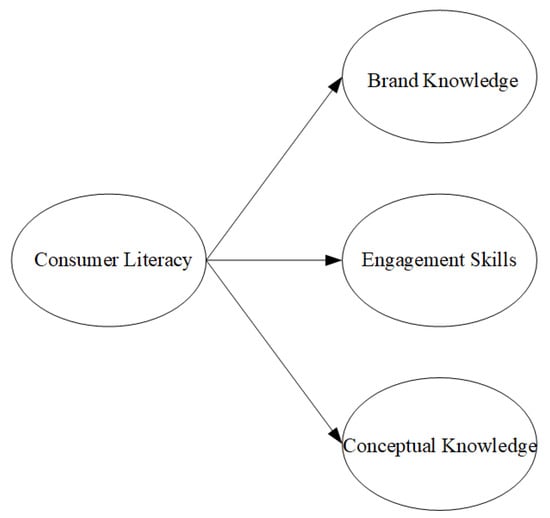

Based on the results obtained from the qualitative analysis and exploratory factor analysis, this study concluded that CL in virtual brand communities is a second-order factor structure, where the first-order factors are three dimensions including brand knowledge and the second-order factor is CL; the structural model is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Structural model of CL in virtual brand communities.

In this study, the second-order factor model of CL was estimated numerically using the AMOS 24.0 software, and the following fit indices were obtained: χ2/df = 1.205, <3; RMSEA = 0.032, <0.05; GFI = 0.965 and AGFI = 0.939, >0.9; NFI = 0.957 and CFI = 0.992, >0.9. From the results, it can be seen that the data and the model fit well. Specifically, the standardized factor loadings for each measure were higher than 0.7 for the relationship between the first-order factor and its measures (see Table 7); the factor loadings for the second-order factor (CL) and its three dimensions of attribution were in the range 0.685–0.822, and all of them were at a more desirable level, indicating that the measures in this study were of high quality.

Table 7.

Reliability and construct validity tests.

In this study, the reliability of the scale was assessed using the overall reliability Cronbach’s alpha coefficient and the combined reliability CR index. The results showed that the overall scale Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.863, and the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for each dimension of the scale ranged from 0.762 to 0.860, and the CR values ranged from 0.766 to 0.863, all of which were greater than 0.7 (see Table 7), indicating that the scale’s overall reliability was good [44].

The content validity of the scale is mainly controlled by qualitative methods. First, as mentioned above, the scale was developed based on existing CL research and in-depth interviews with consumers in virtual brand communities, and it was developed with the aim of being semantically concise and clear, and the suggestions of experts and researchers in related fields were sought. In addition, the content and expression of the measurement items were modified and improved based on the feedback from the respondents in the first questionnaire survey. Therefore, it can be seen that the scale development process of this study was rigorous and standardized, and had a certain reliability in terms of content. Second, this study also examined the construct validity in terms of convergent validity and discriminant validity. The average variance extracted (AVE) of each latent variable was calculated based on the standardized factor loadings of each measure, and the results are shown in Table 7. The AVE values of each latent variable were greater than 0.5, indicating that the scale had good convergent validity [45]. In addition, Table 8 shows that the square root of AVE of each latent variable was greater than the correlation coefficient with other dimensions, indicating that the scale has good discriminant validity.

Table 8.

Schematic table of discriminant validity.

4.3.3. Comparative Analysis of Competitive Models

The previous reliability analysis was able to demonstrate that the second-order factor structure of CL in virtual brand communities fits the pattern of the data, but this study also uses a competitive model comparison analysis to further determine the rationality of the second-order factor structure of CL in virtual brand communities. Specifically, two competitive models were constructed in this study: model 1 is a one-factor model, which is a model in which all 10 measures belong to a single factor of CL; model 2 is a two-factor model in which the two dimensions with the highest correlation coefficients (brand knowledge and engagement skills) are combined to form a two-factor model; and model 3 is a second-order factor model of CL containing the three dimensions proposed in this study. The fit effects of these three models were examined separately, and the results are shown in Table 9. The fits of the one- and two-factor models were significantly worse than that of the three-factor model, indicating that the three-factor model has a good fit.

Table 9.

Comparative results of competitive model analysis.

In addition, this study also considers CL in virtual brand communities as a first-order, 3-dimensional factor structure (without the higher-order factor of CL). From both empirical and theoretical perspectives, this study still considers the need to retain the higher-order construct of CL for the following reasons: first, from a methodological perspective, when the first-order or low-order confirmatory factor analysis model fits the data well, a higher-order factor is used to explain the correlation between the lower-order factors for model simplification reasons, i.e., a higher-order model is used instead of a lower-order model; and a second-order or higher-order model can separate the unique variance of the first-order factor from the measurement error, which makes the parameter estimation of the model more accurate. Second, since the fit indices obtained after the first-order factor analysis did not improve compared to the fit indices of the model proposed in this study, and the exploratory factor analysis showed that the three factors were significantly correlated with each other, this also proved the existence of a higher-order factor from the data level. Finally, the existing theoretical analysis supports the existence of such a higher-order construct as CL. Thus, this study further confirms that CL in virtual brand communities is composed of three dimensions: brand knowledge, engagement skills, and conceptual knowledge, and that the developed 10-item scale for measuring CL in virtual brand communities is of excellent quality.

4.4. Nomological Validity Analysis

The purpose of this phase of the study was to test the nomological validity of the CL scale in the virtual brand community. A necessary condition for a construct to be recognized is its ability to predict certain other variables [46], which is important for testing the validity of the scale. In this study, the construct of “value co-creation willingness” was selected as the outcome variable based on the correlation between the constructs indicated by existing studies and theories after a theoretical review. If CL can influence value co-creation willingness, it means that the scale developed in this study has nomological validity. The virtual brand community is a typical platform for value co-creation, and the service-dominant logic suggests that the knowledge and skills possessed by consumers play an important role in value co-creation. Companies are responsible for proposing value propositions, consumers invest in operational resources such as knowledge and skills, and both parties co-create value in the interactive process [47]. And previous research has also suggested that consumer knowledge in the tourism industry has a positive relationship with consumer participation in value co-creation [48]. Xiao and Ma’s study demonstrated that consumer knowledge has a direct impact on value co-creation behavioral tendencies in the remodeling industry [49].

4.4.1. Data Sources and Structure

The online questionnaire was distributed through the Questionnaire Star platform, and 246 valid questionnaires were collected. Among the respondents, 126 were male, accounting for 51.22%; 169 were aged between 18 and 25, accounting for 68.70%; and 227 had a bachelor’s degree or above, accounting for 92.28%. In terms of the length and frequency of participation in the community, 81.30% had participated in the community for more than half a year, and 40.65% spent an average of less than one hour browsing the community each time.

4.4.2. Measuring Tool

CL in the virtual brand community adopts the scale developed independently by this study, with 10 measurement items in three dimensions, and the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of each dimension are 0.824, 0.867, and 0.806, respectively. Value co-creation willingness adopts the scale developed by Yi and Gong [50], with five measurement items, and the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient is 0.859, and the scale has good reliability.

4.4.3. Data Analysis

In this study, the nomological validity was tested using SEM, which was analyzed using the AMOS 24.0 software to examine the path relationship between value co-creation willingness as the outcome variable and the three dimensions of CL as the independent variables. The analysis found that the model had a good fit, in which χ2/df = 1.247, less than 3; RMSEA = 0.032, less than 0.05; and the values of GFI/AGFI/CFI/NFI exceeded the standard of 0.9. Overall, the fit between the data and the theoretical model was good. The results of the study are shown in Table 10, and it can be seen that the three dimensions of CL have a significant positive effect on value co-creation willingness, so the scale of CL in virtual brand communities developed in this study has good nomological validity.

Table 10.

Schematic table of nomological validity.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Implications

On the basis of the existing research on CL, this study focuses the research context on virtual brand communities, clarifies the concept and connotation of CL in virtual brand communities, and clarifies the research boundary of CL in virtual brand communities. On this basis, semi-structured in-depth interviews and a literature analysis were used to collect data, explore the structure of CL in virtual brand communities, and make qualitative generalizations about the potential dimensions of CL in virtual brand communities. Then, following the steps and procedures of scale development, this study further identified three dimensions of CL in virtual brand communities, including brand knowledge, engagement skills, and conceptual knowledge, and clarified the conceptual meaning of each dimension. Brand knowledge refers to the basic knowledge related to brand products that consumers need to have when browsing virtual brand communities, which can be acquired through daily learning or life experiences; engagement skills refer to the ability of consumers to perform some process-specific behaviors to complete the browsing of the community or after sales of products, which help consumers better navigate virtual brand communities and protect their rights and interests; conceptual knowledge refers to consumers’ ability to understand the relationship between the product’s own value and its actual use value, to understand the importance of the product to them, and to be able to create the maximum use value for themselves.

In addition, this study developed a second-order measurement scale of CL with good reliability and validity, containing 10 measurement items, which elevates the research on CL in virtual brand communities from the theoretical analysis level to the practical operation level, providing a measurable tool for subsequent scholars to conduct relevant empirical research, and also providing a referable reference value for the measurement of CL in other contexts. In summary, the findings of this study fill the gap in the field of CL research in virtual brand communities, and at the same time enrich the research results on CL.

5.2. Managerial Implications

Improving CL in virtual brand communities is an important step to achieve a win–win situation for both companies and consumers. Improving CL can directly contribute to rational consumption and satisfaction, and it can also motivate business managers to be consumer-centric at all times, strive to improve the quality of products and services, and think about consumer rights.

Specifically, for individual consumers, this study can help consumers to have a clearer perception of their own literacy. This study’s analysis of CL in virtual brand communities helps consumers to take appropriate measures to target themselves to improve their slightly weak literacy in a certain dimension, which in turn enables them to better navigate virtual brand communities and successfully complete their consumption activities.

For business managers, this study helps them to better understand the meaning of CL in virtual brand communities, and provides a theoretical basis and strategic guidance for them to solve some problems in the communities. When operating virtual brand communities, managers should not only focus on the technical characteristics of the communities themselves, but also consider the impact of literacy on consumers and take some consumer education measures. In other words, enterprise managers should take the three dimensions of CL as the grasp and footing point to carry out the literacy education of consumers browsing virtual brand communities. For example, the community should be fully introduced to the important knowledge of the product to help consumers to understand the basic information of the product, and to improve the efficiency of consumers to search for information, which will help to improve the satisfaction of consumers in the community, and thus, lead to the occurrence of co-creation-of-value behavior [51]; the layout of various functional sections in the community (posting area, announcement area, communication area of the person in charge, etc.) should be clear and concise to help consumers use it more quickly and efficiently; community managers should develop a sound brand communication plan from the consumer’s perspective [52], emphasizing the high quality of products and after-sales services, not just the introduction of basic product information, but also the impact on consumers, etc. Managers can also provide incentives to encourage knowledge sharing among consumers to help them gain more information, and thus, increase satisfaction and loyalty [53].

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

This study focuses on corporate-initiated virtual brand communities, and it remains to be verified whether the findings hold true in communities formed by consumers on their own initiative. In future research, continued exploration in the area of CL in virtual brand communities will be conducted to analyze the impact of CL in virtual brand communities on strengthening interactions among community members, promoting value co-creation and brand loyalty.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.C.; methodology, Z.C.; software, Z.C. and G.L.; validation, Z.C.; formal analysis, G.L.; investigation, Z.C.; resources, Z.C.; data curation, Z.C.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.C.; writing—review and editing, Z.C. and G.L.; visualization, Z.C.; supervision, Z.C.; project administration, Z.C. and G.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers and editor.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Meng, T. Perceived Manager Support, Perceived Community Support and Customer Innovation Behavior in Brand Community. Bus. Manag. J. 2017, 39, 122–135. [Google Scholar]

- Hajli, N.; Shanmugam, M.; Papagiannidis, S.; Zahay, D.; Richard, M.O. Branding co-creation with members of online brand communities. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 70, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, M.; Bi, X.H.; Xu, Y.S. Research on the effects of governance mechanisms on customer participation in value co-creation behavior in virtual brand communities. Bus. Manag. J. 2020, 42, 144–159. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, X.H.; Xie, L.S. Value co-destruction: Connotation, research topics and prospect. Nankai Bus. Rev. 2019, 22, 88–98. [Google Scholar]

- Nam, K.; Baker, J.; Ahmad, N.; Goo, J. Dissatisfaction, disconfirmation, and distrust: An empirical examination of value co-destruction through negative electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM). Inf. Syst. Front. 2018, 22, 113–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, S. Moderating effects of consumer competency on dietary life satisfaction among one-person households classified by dietary lifestyle. Consum. Policy Educ. Rev. 2018, 14, 55–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, C.R.; Yap, S.F. Low literacy, policy and consumer vulnerability: Are we really doing enough? Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2020, 44, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, N.; Villaseñor, N.; Yagüe, M. Sustainable co-creation behavior in a virtual community: Antecedents and moderating effect of participant’s perception of own expertise. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, L. Competent consumers? Consumer competence profiles in Norway. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2010, 31, 418–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.Y.; Rha, J.Y.; Widdows, R. Toward a digital goods consumer competence index: An exploratory study. Fam. Consum. Sci. Res. J. 2011, 40, 184–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinedu, A.H.; Haron, S.A.; Osman, S. Competencies of Mobile Telecommunication Network (MTN) Consumers in Nigeria. IOSR J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2016, 21, 61–69. [Google Scholar]

- Viswanathan, M.; Sridharan, S.; Gau, R.; Ritchie, R. Designing marketplace literacy education in resource-constrained contexts: Implications for public policy and marketing. J. Public Policy Mark. 2009, 28, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warmath, D.; Zimmerman, D. Financial literacy as more than knowledge: The development of a formative scale through the lens of Bloom’s domains of knowledge. J. Consum. Aff. 2019, 53, 1602–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, W.W.; Yuen, A.H. Developing and validating of a perceived ICT literacy scale for junior secondary school students: Pedagogical and educational contributions. Comput. Educ. 2014, 78, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaglia, M.E. Brand communities embedded in social networks. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozinets, R.V. The field behind the screen: Using netnography for marketing research in online communities. J. Mark. Res. 2002, 39, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amine, A.; Sitz, S. How Does a Virtual Brand Community Emerge? Some Implications for Marketing Research. 2004. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/238671128 (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Sicilia, M.; Palazon, M. Brand Communities on the Internet: A Case Study of Coca-Cola’s Spanish Virtual Community. Corp. Commun. 2008, 13, 255–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yang, W.W. The Impact of Virtual Brand Communities Members’ brand Identification on Brand Loyalty. Manag. Rev. 2012, 24, 96–106. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, M.X.; Liao, J.Y.; Zhou, N. Can Community Experience Lead to Brand Loyalty? A Study of the Effect and Mechanism of Different Experience Dimensions. Nankai Bus. Rev. 2015, 18, 151–160. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, H.; Olfman, L.; Ko, I.; Kim, K.K. The influence of on-line brand community characteristics on community commitment and brand loyalty. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2008, 12, 57–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, F.C.; Jiang, Y.T. Research on customers’ value co-creation behavior in virtual brand community. Manag. Rev. 2018, 30, 131–141. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, B.; Jin, Y.S.; Li, Z.H.; Bu, Q.J. Dimension Exploration and Scale Development of Customer Value Co-destruction Behavior in Virtual Brand Community. Collect. Essays Financ. Econ. 2023, 298, 91–101. [Google Scholar]

- Jae, H.; DelVecchio, D. Decision making by low-literacy consumers in the presence of point-of-purchase information. J. Consum. Aff. 2004, 38, 342–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengtsson, A.; Firat, F. Brand literacy: Consumers’ sense-making of brand management. ACR North Am. Adv. 2006, 33, 375–380. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G.F.; Zhang, M. A Review and Prospect of Consumer Competency. Chin. J. Appl. Psychol. 2022, 28, 147–156. [Google Scholar]

- Adkins, N.R.; Ozanne, J.L. The low literate consumer. J. Consum. Res. 2005, 32, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DelVecchio, D.S.; Jae, H.; Ferguson, J.L. Consumer aliteracy. Psychol. Mark. 2019, 36, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anna, F.; Riina, V.; Nuria, R.P.; Yves, P. Background Review for Developing the Digital Competence Framework for Consumers. JRC Tech. Rep. EUR 2016, 28196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gronhoj, A. The consumer competence of young adults: A study of newly formed households. Qual. Mark. Res. 2007, 10, 243–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.W.; Luo, H.H. The Influence of Financial Literacy on College Students’ Consumption Behavior by Internet Loan—Based on the Survey Data of College Students from Hunan Province. Huabei Financ. 2021, 531, 33–45. [Google Scholar]

- Viswanathan, M.; Umashankar, N.; Sreekumar, A.; Goreczny, A. Marketplace literacy as a pathway to a better world: Evidence from field experiments in low-access subsistence marketplaces. J. Mark. 2021, 85, 113–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lone, U.M.; Bhat, S.A. Impact of financial literacy on financial well-being: A mediational role of financial self-efficacy. J. Financ. Serv. Mark. 2022, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuo, Y.Z.; Bai, C.H.; Wang, L. Tourist Well-being: Conceptualization and Scale Development. Nankai Bus. Rev. 2020, 23, 166–178. [Google Scholar]

- Rittle-Johnson, B.; Siegler, R.S.; Alibali, M.W. Developing conceptual understanding and procedural skill in mathematics: An iterative process. J. Educ. Psychol. 2001, 93, 346–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- She, S.X.; Xu, H.R.; Xu, D.Y. The Study of Consumer Psychological Contract to Commercial Anchor in Live Streaming Marketing: Scale Development and Dynamic Evolution. Collect. Essays Financ. Econ. 2022, 286, 93–102. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, W.; Zhou, H.J.; Song, S.G. Craftsman Spirit Scale Development and Validation of Time—honored Enterprise Employees. Chin. J. Manag. 2023, 20, 221–230. [Google Scholar]

- Boateng, G.O.; Neilands, T.B.; Frongillo, E.A.; Melgar-Qui Onez, H.R.; Young, S.L. Best practices for developing and validating scales for health, social, and behavioral research: A primer. Front. Public Health 2018, 6, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bearden, W.O.; Netemeyer, R.G.; Teel, J.E. Measurement of consumer susceptibility to interpersonal influence. J. Consum. Research 1989, 15, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronbach, L.J. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Brodie, R.J.; Ilic, A.; Juric, B.; Hollebeek, L. Consumer engagement in a virtual brand community: An exploratory analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.L.; Curran, P.G.; Keeney, J.; Poposki, E.M.; Deshon, R.P. Detecting and deterring insufficient effort responding to surveys. J. Bus. Psychol. 2012, 27, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacon, D.R.; Sauer, P.L.; Young, M. Composite reliability in structural equations modeling. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1995, 55, 394–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: A comment. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, L.S.; Newman, D.A. Construct development and validation in three practical steps: Recommendations for reviewers, editors, and authors. Organ. Res. Methods 2023, 26, 574–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Service-dominant logic: Continuing the evolution. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2008, 36, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.C.; Chen, P.S.; Chien, Y.H. Customer expertise, affective commitment, customer participation, and loyalty in B & B services. Int. J. Organ. Innov. 2014, 6, 174–183. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, M.; Ma, Q.H. The effects of customer resources on customer value co-creation behavior—The moderating role of perceived control and subjective norm. J. Northeast. Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2019, 21, 149–155. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, Y.; Gong, T. Customer value co-creation behavior: Scale development and validation. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1279–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, N.; Villaseñor, N.; Yagüe, M.J. Influence of Value Co-Creation on Virtual Community Brand Equity for Unichannel vs. Multichannel Users. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, P.Y.; Wan, D.M.; Wu, J.Q. The Influence Mechanism of Virtual Brand Community Quality on the Consumers’ Sense of Brand Well-being: Empirical Test of Mediating Path and Its Boundary Conditions. J. Cent. Univ. Financ. Econ. 2022, 419, 100–114. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.; Liao, J.Y.; Chen, J.W.; Hu, Y.H.; Du, P. Motivation for users’ knowledge-sharing behavior in virtual brand communities: A psychological ownership perspective. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2022, 34, 2165–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).