Abstract

The sustainability of healthcare systems is challenged by the international migration of health workers in many countries. Like other Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries, a great number of health professionals from Hungary have emigrated recently, increasing the shortage of health workers in the country. The aim of this study is to explore the migration attitudes of Hungarian health workers, applying a micro-level approach of push–pull factors. For this purpose, semi-structured interviews have been conducted with practicing and inactive Hungarian health professionals living in Hungary and abroad. The interviews were subjected to a thematic analysis, and the following groups of factors were revealed and discussed: wealth and income, workplace, human capital, quality of life, family, personal network, and personality. In addition, geography and life stage (life course) as two overarching, integrative categories are also discussed. The results point to the role of income, work environment, and family in migration decisions. As a new factor, the importance of geographical characteristics (local context, distance) is also explored, which has received less attention in previous studies. A novelty of our study is the CEE post-socialist point of view, mirrored by the life-path elements of the interviews. Another novelty is the qualitative and micro-level approach, forming the basis of policy recommendations presented at the end of our study.

1. Introduction

Health professionals and human resource management are among the fundamental “pillars” or “building blocks” of the health system [1,2]. This means that an appropriate number and composition of the labor force in health are essential for the system to properly function. Recently, the COVID-19 pandemic also demonstrated that having adequate information on the basic processes related to the operation of the healthcare sector from the perspective of its employees is essential. Such emergency situations represent an additional burden on health workers, thus ultimately endangering the safety of care and the sustainability of the healthcare system (e.g., [3]). In Hungary, health professionals are among the critical elements of healthcare for various reasons. In recent years, a lot of Hungarian health workers have emigrated, and the shortage of qualified healthcare staff has become permanent, which has negative consequences for the performance of the system, and this process has also attracted the attention of policy makers [4,5]. Therefore, this study focuses on the migration of Hungarian health professionals.

In relation to healthcare, the issue of sustainability has already been investigated in numerous studies. At the level of the entire healthcare system, sustainability can be interpreted as whether the system is able to provide adequate quality care efficiently and continuously (e.g., [6]). However, the concept can also be defined more broadly; for example, according to the widely used triple-bottom-line approach, environmental, economic, and social dimensions of sustainability can be identified in healthcare [7,8,9]. Some researchers use other approaches to the sustainability of healthcare systems, highlighting different aspects. Marimuthu and Paulose [10], for example, emphasize the following dimensions of sustainability in relation to healthcare based on a systematic literature review: environment-oriented, customer-oriented, employee-oriented, and community-oriented dimensions. One of the common features of the above approaches is that health workers are also part of healthcare sustainability, along with factors such as workplace environment, employee satisfaction, education, training, employment conditions, and migration.

Among the dimensions and elements of sustainability in healthcare, we focus on health workers in this study. A fundamental question related to sustainable health workforce management is whether the number and qualification mix of the available workforce are sufficient to carry out the necessary tasks, and how to ensure the continuous availability of these workers. Within the framework of national health systems, sustainability means that national self-sufficiency is realized in terms of human resources. In other words: what is the proportion of health professionals trained in a given country within the total number of health workers employed in that country [11]? However, the sustainability of national systems can also be understood as the system in which a given country is able to deal with inequalities caused by the market (e.g., uneven geographical distribution) to retain a healthcare workforce, including workers trained abroad, and to improve the performance of its workforce [12]. According to our approach, the essence of the sustainability concept with relation to the workforce is to ensure a continuous supply of health professionals who are able to provide healthcare services in accordance with emerging social needs (see also [13]).

Ensuring the sustainability of healthcare workforce is a considerable challenge in numerous countries. This phenomenon has been thoroughly explored even in countries in the Global North, such as Australia, the United Kingdom, or the United States of America (e.g., [14,15,16]). However, in recent years, the problems of other regions, such as the Global South, have also appeared in studies within this field. These studies have pointed out how the global migration of health workers creates unequal and unjust situations and threatens the sustainability of the health systems in the sending countries (e.g., [17,18]).

Recent studies on European healthcare systems, including in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), conceptualize the sustainability of healthcare in several ways: budgetary/fiscal/financing, access [19,20], and environmental sustainability [21]. One of the causes as well as the consequences of these sustainability problems is the crisis of the medical workforce (e.g., [22]). National healthcare systems in this region struggle with significant sustainability problems, partly due to the migration of health workers. In fact, too much reliance on foreign labor poses a risk to the sustainability of European healthcare systems and increases the workforce deficit in the sending countries [23]. Furthermore, policy changes can have a negative effect on the immigration of healthcare workers and thus may risk the sustainability of healthcare. For example, stricter immigration policies introduced after the United Kingdom left the European Union reduced the number of doctors arriving in the country [24]. The international mobility of healthcare professionals in CEE was significantly increased by the accession of these countries to the European Union (EU), causing a human resource shortage and sustainability problems, especially in “some poorly served regions and some rare specialties, which threatens the goal of adequate service provision” [25] (p. 85).

The migration motivations of healthcare professionals in CEE are diverse. Several studies have pointed out that the main reasons for migration from this region to Western EU countries are wage differences, working conditions, and training and career opportunities [26,27]. However, several other motivational factors were also revealed in these countries. Studies from Poland have found that, in addition to wage levels, good working conditions, such as a proportionate workload and adequate equipment, are important for retaining health professionals [28,29]. Other factors also influence the migration intentions of these people, such as new experiences, family reasons [30], balance between work and family life, political dependence [31], or hierarchical power relations within healthcare [32]. In the case of Romania, the shortcomings of the domestic healthcare system as well as higher wages and better living and working conditions abroad proved to be crucial factors [33,34]. Motivational factors appearing in studies from Serbia include professional development, learning a foreign language, a friend or relative living abroad, acquiring foreign experience, (the lack of desired) domestic job opportunities, and quality of life [35] as well as state-supported training opportunities [36]. In Croatia, a recent study has shown that, in addition to social factors, the characteristics of a person’s personality and the sense of belonging to a social environment (e.g., ethnocentrism) play an important role in the formation of attitudes towards emigration [37]. In Slovakia, Williams and Balaž [38] scrutinized the migration intentions of doctors and found that, in addition to better salaries, the opportunity for professional development was the main motivating factor. Similarly, Genelyte [39] conducted a survey among Lithuanian health workers who had migrated to Sweden, and the following motivating factors proved to be the most important: low level of wages and social respect, poor working conditions, and structural problems of healthcare in their home country (e.g., uncertainty due to constant reforms).

In Hungary, similarly to other CEE countries, the international migration of health professionals became a political issue after the enlargement of the EU in the 2000s and early 2010s. In general, the mobility level and the willingness to emigrate among Hungarian health professionals is higher than the national average [40,41]. Research shows that the primary reasons of these health professionals to work abroad are low wages and unfavorable working conditions in Hungary [42,43,44,45,46]. However, other factors also play a role in their migration decisions. For example, ethical considerations [47], career opportunities, working conditions, perception of the social environment [43], exhaustion, depersonalization, and burnout [48] significantly increase the willingness of health workers to leave. In conclusion, economic factors are presumably the dominant motives for the migration of Hungarian health workers, but recent studies suggest that the complexity of motives needs to be further investigated.

The migration motivations of the workforce, including health workers, are often analyzed using a micro-level approach. According to these analytical frameworks, the main reasons for migration are on the one hand the individual’s expectations and intentions, and on the other, the situation and attitudes of the individual’s family or other people living in the same household. Furthermore, the environment in which the individual is socialized also affects migration-related decisions [49,50,51,52]. For example, according to the push–pull framework [53], positive and negative factors at the origin and destination guide individuals in making the decision to migrate or stay. In addition, there are ‘intermediate’ (e.g., national policies) and individual factors (e.g., how the person perceives various external factors) that also influence the decision. The neoclassical micro-level theory [54] considers migration as an individual investment in human capital, in the development of human productivity. Therefore, the theory suggests that individuals make rational decisions, weighing the expected benefits and costs of migration, and if the former outweighs the latter, the individual will choose to migrate. In contrast, the core idea of the behaviorist approach [55] is that while migration is the result of a conscious decision of the individual, this decision is not purely rational. People’s knowledge of the world (e.g., about the destination country) is subjective and limited, and their own space for action and motivations are influenced by individual characteristics (e.g., age) and the environment (e.g., social norms). According to the theory of social systems [56], migrants navigate in a global system of power relations and status differences. They move to another country in the pursuit of a higher social status, but if the host country is at a higher level on the global prestige scale compared to their country of origin, then they are unlikely to achieve a high social status at their destination. Therefore, these immigrants will probably belong to the lowest stratum of the destination country’s society in terms of socioeconomic status, and even the lower-status strata of the native population will generally have a higher level of social mobility than them. In this study, we use the model of push–pull factors to explore the migration motivations of Hungarian health workers in as much detail as possible.

The push and pull factors influencing the migration decisions of health workers are often categorized into three groups: macro-, mezzo-, and micro-level factors (Table 1). Macro-level drivers are global- and national-level economic, social, political, and cultural factors. These include, for example, global phenomena and processes affecting migration, the performance of the national economy, peculiarities of the sociocultural environment and national health system, and the discourses and policies related to migration. Among the mezzo-level factors are aspects related to the health profession, the institutional system, and certain specialties within healthcare. This group contains drivers such as working conditions, professional and career development opportunities, and social relations at the workplace. Micro-level factors include individual, household, and family characteristics that push and pull migrants towards (non-) migration. Some of them stem from the individual’s personality, social background, life circumstances, and goals. Other micro-level factors, however, are based on the influence of the individual’s family and other household members [24,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67].

Table 1.

Drivers of health workforce migration.

In our research approach, we separate the analytical level of migration (e.g., whether the focus is on aggregate migration trends or on individual migration decisions) and the level on which the factors causing migration operate (see the macro- and mezzo- and micro-level factors in Table 1). Thus, in this study, we use the push–pull framework, examining the micro-level factors that influence Hungarian health workers’ decisions to migrate, but we also take into account how these individuals perceive various mezzo- and macro-level factors. Thus, our analytical framework is broader than the group of micro-level factors listed in Table 1 (for further details see the Section 2).

The main aim of this study is to explore the migration intentions and motivations of Hungarian health workers. The study also aims to expand and deepen the existing knowledge on the subject, revealing the complexity of motivating factors and their background mechanisms. Therefore, the research questions addressed in this study are as follows: What factors influence the migration intentions of Hungarian health professionals, and how do these factors operate? To answer these questions, we conducted qualitative research: semi-structured interviews have been conducted with Hungarian doctors and other health professionals who work in the healthcare system of Hungary or another country, or who have already left the healthcare career.

Our contribution to this research field can be summarized as follows. First, we examine the migration of health professionals from a CEE perspective. Although there have already been several studies on the migration of health workers in CEE (e.g., [25,26,27,29,68]), the region shows several peculiarities. During the era of state socialism, there was essentially no shortage of health professionals in these countries, as the health systems here could develop in isolation from international processes and market mechanisms due to state paternalism. However, after 1990, these systems became exposed to various processes such as external and internal migration or the absorbing effect of the private sector on workforce supply. The interviews conducted by our research team contain several life-path elements, which reveal some of the peculiarities of the above processes in a historical perspective, based on the real-life experiences of the interview partners.

The second main contribution comes from our qualitative approach. The international mobility of high-skilled professionals in general, and that of health workers in particular, has already been examined in numerous studies. However, articles discussing the sustainability of healthcare systems from the perspective of human resources often ignore the role of the individual’s micro-environment in making migration decisions and examine macrostructures, analyzing migration processes and policies on a global or national scale instead [12,16,18]. However, by using interviews as a research method, we also reveal underlying factors and background processes that would hardly be possible with a large-scale statistical analysis or questionnaire survey. In this way, we can expand the knowledge about the migration motivations of health professionals, and we can also provide new recommendations for policy makers.

The rest of the study is divided into the following structural units. In the section following the current theoretical introduction, the data collection and analytical methods are presented. In the subsequent section, the Hungarian national context is briefly described. Next, the main results of our interview research are presented. In the following section, the results are compared with the previous findings of the relevant literature in the context of a discussion. Finally, the paper ends with some concluding thoughts and policy recommendations.

2. Materials and Methods

For this study, we used a qualitative data collection technique, conducting semi-structured interviews with Hungarian doctors and other health workers. In selecting the interviewees, a key criterion was to assemble as diverse a group as possible in terms of gender, age, specialty, place of residence (e.g., urban or rural), and migration status (e.g., emigrated, re-migrated, decided against migration). Therefore, the respondents were selected nonrandomly through nonprobability sampling, a process in which our research team regularly checked the composition of the sample. On the one hand, purposive sampling was used to meet the above ‘diversity’ criteria. On the other hand, the snowball technique was also used, with respondents suggesting other health workers among their colleagues.

All the interviewees are health professionals who were either born in Hungary or born abroad but are currently working or have worked for some time in the Hungarian health system. The group of interviewees was divided into four main categories: (1) those who have worked only in Hungary so far, (2) those who are currently working abroad, (3) those who started their careers in Hungary, then emigrated but have already returned to Hungary, and (4) others, such as those who were born in other countries and started their career there but are currently working in the Hungarian health system.

In total, 58 interviews have been conducted, involving a total of 62 interviewees. The group of the participants included 39 doctors and 23 other health professionals. The gender ratio was 35 women to 27 men. Of the interviewees, 17 were working abroad at the time of the interview, 22 had only worked in Hungary before the interview and never abroad, 8 had worked abroad but returned to Hungary before the interview, 4 had a health professional qualification but had already left the profession, and 7 belonged to the “other” category.

The interviews were conducted between 16 July 2019 and 5 August 2020. The potential interviewees were approached directly via already-existing professional channels or via the snowball sampling method. Some of the interviews were carried out online due to the COVID-19 pandemic and travel restrictions, while others were conducted face-to-face, partly in private (e.g., the interviewee’s home) and partly in office spaces (e.g., the interviewee’s workplace). Of the interviews, the shortest lasted 15 min and the longest 115 min, with an average interview length of 54 min. For consistency, we used the same interview guide for each interviewee, but due to the semi-structured nature of the interviews, we omitted topics that were irrelevant (e.g., we did not discuss the circumstances of emigration and life abroad for those interviewees who had worked only in Hungary until the time of the interview). We also kept the same flexibility to allow interviewees to talk about new topics if they arose.

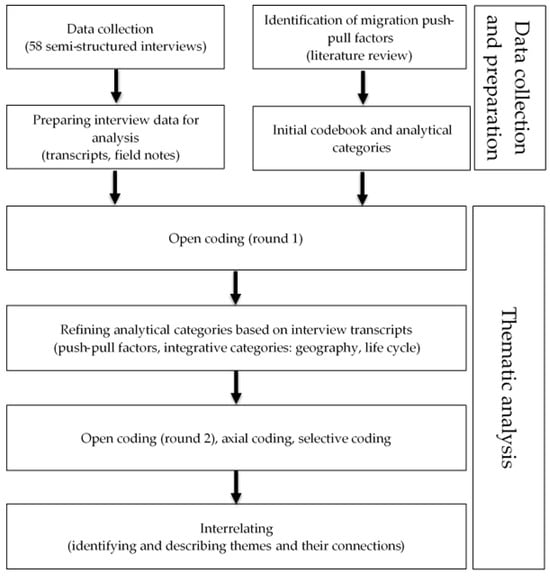

For the qualitative data analysis, field notes and interview transcripts were analyzed using thematic analysis. A three-member research team performed the coding and analysis so that codes and data could be checked and reviewed more efficiently (not depending on the subjectivity of a single individual). The key aspect of the analysis was the definition and identification of micro-level factors influencing the migration decisions of health workers. Our analytical approach was based on the individual’s interpretations, attitudes, and experiences: how interviewees reacted to and evaluated various factors. These subjective interpretations and reactions were considered as micro-level factors. At the beginning of the analysis, a code book and analytical categories were prepared based on the literature, which were supplemented after reviewing the interview transcripts. Thus, the following analytical categories were identified: wealth and income, workplace, human capital, quality of life, family, personal networks, and personality. According to the interviews, geographical factors (e.g., distance, the importance of place) and life cycle/stage of life were also of great importance in the migration decisions of the interviewees. However, since these are integrative categories that cover almost all push–pull factors, we present them in the Discussion section. Segments of the interview texts were classified into these categories, looking for patterns in the interviewees’ narratives. In order to increase the reliability of the analysis, each member of the research team checked the quotes and their categorization. For a quote to be included in the analysis, all members had to agree on the interpretation. It is worth mentioning that the themes were often overlapping; thus, certain interview quotes were associated to multiple themes. During the analysis, we examined how and in what context the abovementioned topics were mentioned by the interview partners. If a certain theme was mentioned, what kinds of attitudes can be identified? How did the identified factor influence the migration-related attitudes and decisions of the interview partner? The process of the data collection, preparation, and analysis is summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The process of data collection, preparation, and analysis.

3. The Context of the Research

Like other post-socialist countries in CEE, Hungary became involved in the international migration of health professionals relatively late, after the collapse of the state socialist regime [25,43,44,69,70]. Mainly political and ideological reasons contributed to this delay since the borders were closed before 1990. This immobility was further reinforced by a practice when patients unofficially paid extra money to health professionals for potential benefits in the public healthcare system, which was otherwise free and relatively well-equipped with human resources but was inefficiently operating due to the shortcomings of the centrally planned economy. This was the ‘gratuity’ system [71]. This practice of informal payments survived even after the political changes of the 1990s and supplemented the otherwise low official income of health professionals [72,73]. Thus, the health workers who received ‘gratuity payments’ were less motivated to emigrate when viewed from the income side as well.

After Hungary’s accession to the EU, the obstacles in the way of the international labor flow were gradually removed, encouraging the traditionally less mobile Hungarian workers to find a job abroad [74]. Emigration was especially attractive for those who were highly qualified, having easily convertible knowledge, like the health professionals [25]. Nevertheless, fewer doctors migrated from Hungary to Western Europe than, for example, from Poland or the Baltic states [75]. However, doctors and other health professionals working abroad induced a considerable shortage of human resources in Hungary’s healthcare system [45], and even immigration (which was significantly smaller than emigration) could not compensate for this [40,76,77].

Hungary’s health policy also reacted to the dysfunctions caused by the shortage of human resources, using both negative (prohibitive) and positive (encouraging) measures. One of the negative measures was the prevention of emigration with administrative means, for example, students who graduated at a Hungarian university are/were obliged by law to work in Hungary for a certain period of time. In addition, the acceptance and giving of informal gratuity payments was strictly prohibited [73]. On the other hand, as an incentive, doctors’ wages were raised, and the technical infrastructure of the healthcare sector was also improved.

The emigration of health workers from Hungary, the resulting shortage of human resources, and the effects of the policy measures applied are widely discussed in academic literature, and they also influence newer policies. These studies primarily tried to reveal the characteristics of the migration of Hungarian health workers on a macro-level, based on available statistics and using quantitative methods [43,44,46,78], and they also tried to create models to explain the migration process [44,79]. Others aimed to find out the motivations to work abroad, using mainly questionnaire surveys, involving already practicing health professionals [75,80] and students in higher education [4,47,81]. Based on their results, the main destination countries of Hungarian health professionals are Austria, Germany, and the United Kingdom. Foreign health workers coming to Hungary are mainly from neighboring countries and most of them are ethnic Hungarians [76]. According to recent studies, the lack of human resources in public healthcare is not only caused by emigration, but also by the fact that a lot of professionals run private practices in addition to their jobs in public healthcare, or become completely employed by private service providers, or leave the profession. Due to the labor shortages, overtime is common [73,82], and it has also become a common practice for health professionals to work simultaneously in several institutions. This factor has resulted in the increased workload and burnout of health professionals, pushing them to emigrate [48]. It was observed that the lack of human resources is more severe in peripheral areas [83,84], and the appearance of non-Hungarian, foreign patients places an additional burden on the health system [85,86].

Due to the limitations of quantitative studies, neither the detailed reasons and the complexity of the motivations for migration could be entirely revealed, nor the role of several primarily micro-level factors that play a role in the decision-making process. Nevertheless, exploring these factors would be useful because policy interventions could cover a wider spectrum, be more targeted in this way, eventually leading to a more sustainable healthcare.

4. Research Results: Migration Motivations of Hungarian Health Professionals

The main results of the interviews are presented in this chapter, with a special focus on the migration motivations of the interviewees. The results are presented in accordance with the categories described in the methodological chapter, i.e., wealth and income, workplace, human capital, quality of life, family, personal network, and personality.

4.1. Wealth and Income

Based on previous research, one of the most important motivating factors for the migration of health professionals is the attainable higher income and whether the individual has enough financial resources to mobilize for moving. This was confirmed by the interviews, but the financial factors appeared with less emphasis than expected.

Low wages are a strong push factor, which is not always offset by good working conditions or good relations with colleagues. In certain life stages, the importance of wage level is particularly high, for example, in the event of divorce, having a child, and the illness or death of a relative. Such cases can increase the willingness to migrate. The practice of patients’ informal payments, which compensate the low official income of health professionals, was rejected by several interviewees and mentioned as a factor that strengthened their intention to emigrate:

“And gratuity payments was one of the main reasons why we left, and it’s not so much about how much you can earn but rather just how you can […] go to bed at the end of the day, with how a clear conscience you can fall asleep.”—(male, cardiologist, United Kingdom, small town)

The interviewees consider not only the current or short-term income to be important but also the opportunities to save or invest their money and the pension they can expect in the future. In other words, signs of long-term thinking can be observed in the interviews. This is related to the fact that in several interviews, income appears as a means of achieving a higher quality of living, for example, through a stress-free everyday life, the same or higher income that can be achieved with less work, or general living conditions:

“When I went to England, I suddenly started earning much more than that [income in Hungary], and it took a couple of months before I realized it, and it was such an interesting revelation when I told my wife that ‘hey, I know that we will never have financial problems again’, and then on the one hand it was a very good feeling.”—(male, surgeon, United Kingdom, major city)

Financial aspects also proved to be relevant in relation to housing, since access to accommodation that meets the needs can be an incentive to either stay or emigrate:

“I never wanted to leave my country, but as young people, we feel so helpless, in terms of house building and so on, even though we have been working since I was 19–20 years old, and my partner as well, we cannot create the financial security for ourselves, with which we can have a child, in the long term. Anyway, after graduation I will think about moving abroad but not before graduation.”—(female, nurse, Hungary, village)

If the interviewee sees that achieving decent housing is hopeless from the income that can be earned in their home country, they will be more open to emigration, whereas, for example, if the employer provides accommodation, then it strengthens the intentions to stay. Providing company housing also requires a kind of commitment, so it can have a longer-term effect.

In recent years, the various scholarship schemes and research projects that have played an increasingly important role in Hungarian government policies aimed at retaining and attracting health workers have a pull effect but not only from a financial point of view. In addition to the higher salary or additional income available, such initiatives represent a professional challenge on the one hand, and on the other, the tasks associated with them represent a more long-term commitment which the interviewees want to meet:

“…there was an opportunity at home, so there was money, and I won an OTKA [Hungarian Scientific Research Fund] grant, and because of this, I am now bound here until 2022, but if the money runs out or we can’t win a new one, then I have to think about taking one or two years out, or even three, in order to pull myself together in terms of the number of publications and ability to apply. I am committed until 2022 in total […] well, I have four PhD students to supervise, two of whom are half-way through, which means that they must complete their training until 2022 at the latest.”—(female, assistant professor at a university, Hungary, major city)

The legal environment also spurs the interviewees to stay. The conditions of some scholarships include that the health professional undertakes work in Hungary for a certain period.

A recurring theme in the interviews is that although money and higher income are important, they can be offset by other factors, such as personal relationships, compliance with one’s own values, or domestic career opportunities. Existential fear was formulated as a factor motivating the interviewees to stay, and in connection with this, the high costs of maintaining a divided family or higher living costs abroad appeared the most often.

4.2. Workplace

Based on the interviews, workplace is one of the most important areas in the lives of the interviewed health professionals, and its characteristics influence their migration decisions in several ways. One of the factors included here is workplace environment and atmosphere. For example, among the main push factors, the interviewees mentioned personal conflicts with colleagues, overload due to inadequate work organization, lack of skilled staff, insufficient equipment, and psychological problems and burnout due to the above-listed factors:

“I didn’t like the amount of ‘elbowing’ at the clinic and the fact that people were back-stabbing each other, and in Nagykőrös [a small town in Hungary], I didn’t like that there were no work tools […]. And here, where I just ended up, it’s usually fine.”—(male, dentist, Hungary, major city)

At the same time, good working conditions can also be retaining or pull factors that can ultimately either facilitate or hinder migration. During the interviews, for example, it turned out that elements of the work environment can encourage migration for a new job but can also keep the interviewee at the current workplace. For the interviewees, such an attractive element is, for example, if a workplace is patient-centered, the equipment is of high quality, the appearance of the workplace is esthetic, or the relationship between employees is harmonious. Regarding the latter, interviewees also mentioned that it is appealing to them if they are personally invited to work at a given healthcare institution, if the new workplace arouses sympathy in them at the beginning of their professional relationship, and if they generally feel well in the given workplace environment:

“I have been to several places abroad, but this is something different. On the one hand, the hospital is beautiful and clean. And they don’t reside in a cold, cramped place. It is full of colors: curtains, colorful walls, bedding. […] The second thing is the modernization that I experienced there. Everything is computerized. That caught my attention. Patient-centered care is the way nurses approach patients. And how the patient relates to the staff! This was great to see. And the way colleagues behave towards each other. I experienced this in Finland before.”—(female, nurse, Hungary, major city)

Based on the interviewees’ narratives, professional development and career advancement opportunities are particularly important. Spectacular short-term work results and satisfaction, chances to acquire new knowledge, trainings, diverse professional challenges, and research opportunities emerged as the main push and pull factors. The prestige of the workplace is also a notable factor, i.e., the level of care provided by the institution, the quality of the work there, and the social and professional recognition that the institution receives:

“This is the leading ophthalmology clinic in Denmark. For me, high quality was a very, very important factor in the decision, and, eventually, I managed to get a job here.”—(male, ophthalmologist, Denmark, major city)

However, a career path can also be repulsive if it is considered to be too challenging. According to the interviewees, one of the sources of frustration is to consider the difficulties of promotion due to fierce competition, or that the collective is too withdrawn in their new workplace, where they have problems establishing themselves as new employees. The interviewees also suggested that it is more difficult to succeed in certain geographic locations that in principle offer better opportunities, for example, in a major urban center or abroad due to greater competition, if they have to restart their career almost from scratch. As one interviewee, living in Portugal and no longer working in the health sector, said:

“But in order to get here, I had to leave the [medical] profession to some extent. And after that, I somehow got back, but this would not have been possible from Hungary following a simple medical career path. So, for this, I had to move away from the well-paved medical career. Because this was one of the interesting aspects of a medical career for me, that on the one hand there is a lot of freedom, so as a doctor you can do many different things. However, it is also closed. So, this diversity in turn means a very specific path. Thus, when you decide to become a surgeon or a neurologist or an epidemiologist or whatever, each has its own steps, and then you go through this practically until you retire.”—(male, general practitioner leaving the healthcare sector, Portugal, small town)

Not all of the interviewees emigrated, and even immobility can be a strategy or a source of pride, which can be related to the personality and values of the interviewees. Commitment and love of job can also be retaining or pull factors. For example, there were interviewees feeling proud to have worked at only one workplace in their life:

“I’m proud to say that I have only had one job, that I spent my whole life at a single medical institution. […] It must have meant a lot to me because I have held the position of chief assistant since ‘93, when I was quite young. […] That’s why I wasn’t motivated to try myself elsewhere.”—(male, nurse, Hungary, major city)

However, it is worth considering that in such cases, workplace atmosphere and rapid career advancement are also factors that can encourage health professionals to stay.

4.3. Human Capital

In addition to financial capital, various other symbolic forms of capital also play an important role in the migration of health professionals. However, in this subsection, we only discuss the relevance of human capital among these symbolic capitals, since based on the preliminary literature review and our field research, it has utmost importance in the migration decisions of the interviewed Hungarian health workers.

Two types of human capital were highlighted in the interviews as push or pull factors. The first one is the need for gaining new medical knowledge and skills. It can be observed that professional development is very important for the interviewees in connection with mobility. The main themes emerging from the interviews are the following: learning about new medicines, treatments, or just “new things” through emigration; broadening medical knowledge (“preventing narrow-mindedness”); foreign experience giving a competitive advantage in the field and making health workers more credible in their work; and medical knowledge and skills can be used to find a job almost anywhere in the world (increases individual flexibility and mobility):

“I wanted to go to a place where I could learn, where I would get to know these new things, because I told [myself] that the profession had changed so much during the last 13 years, that I had been working there continuously, that it is unbelievable.”—(female, dentist, Hungary, major city)

However, there are interviewees who re-migrated to Hungary because of certain trainings or who think that the possibility of professional development abroad is not adequate. In other words, although the demand to deepen professional knowledge is basically a motivating factor in finding a job abroad among the interviewed health workers, for some of them, it is more of a factor keeping them in their home country, especially in the case of certain types of specialization:

“I lived abroad in Sweden for three and a half years, so I also lived here, and after that I decided to return home. There were several reasons for this, but I didn’t want to lose this Swedish connection. And then, I had the opportunity to get a substitute job, and for a while, I even worked from home like this, well, not on Skype, but it’s a kind of intranet, which, on the other hand, is like talking to patients on Skype from home, but it’s like a private network. And so, one of the biggest reasons for this was professional, that is, that I wanted to attend certain training courses that were in Hungary or that were more attracting to me there, and then I chose this solution.”—(female, psychiatrist, Sweden, small town, commutes between Sweden and Hungary)

The other important type of human capital that emerged during the interviews is language skills or the lack thereof. According to the narratives of the interviewees, knowing or not knowing foreign languages can be a factor that facilitates or hinders mobility. Some interviewees decided to work abroad to improve their skills in the language of the destination country, whereas others emigrated from a certain country because they did not want to use its official language (the latter can be observed primarily among interviewees who came to Hungary from the Hungarian diaspora in the neighboring countries):

“I actually didn’t want to stay in Serbia because I knew that I wouldn’t be able to make a living there like in a mother-tongue country like Hungary.”—(female, physiotherapist, Hungary, major city)

Lack of language skills can reduce mobility: those interviewees who could not find a job abroad in their profession due to the lack of language skills, according to their statements, did not necessarily want to emigrate:

“But no other languages were taught that time, and the fact that I only knew Russian held me back a little. And I was a little afraid of learning the German language from scratch and then graduating college in German. So that held me back a little.”—(female, nurse, Hungary, major city)

Overall, among the forms of human capital mentioned during the interviews, knowledge of a foreign language and healthcare expertise stood out. Based on the thematic analysis, while the former is more of a factor facilitating migration, the perception of the latter is more diverse.

4.4. Quality of Life

The range of factors influencing quality of life in connection with migration is quite broad. These include, for example, the living environment, the hope for a better life, more and quality free time, a stressful or stress-free living situation, self-realization, personal safety, or even freedom from the intrusion of politics into everyday (private) life.

The interviewees usually associate the above-listed factors with different geographical scales and interpret them in the context of those scales. More specifically, the characteristics of quality of life appearing in the interviews are linked to three geographical scales: the national (country, society), the settlement or neighborhood, and the micro-scale (e.g., personal housing) of the individual.

The characteristics of certain countries and regions, and their society, can be both push and pull factors, or factors that hinder migration. Regarding international mobility, the interviewed health professionals are generally attracted by the fact that the living conditions of the chosen or potential migration destination countries seem fundamentally more favorable. For example, some consider Scandinavia, and especially Sweden, to be a symbol of prosperity and harmony, emphasizing its inclusive social environment. In the case of the United Kingdom, the democratic system of values within society, as well as the better, more child-friendly schooling opportunities are highlighted, so these are factors that attract or keep the interviewed health workers there:

“In addition, the value-based, relatively democratic system of British and Scottish society that dates back several centuries and treats everyone in their place was very positive. Especially when I contrast this with conditions in Hungary, whether it’s about wages, whether it’s about the ethical distribution of available goods, whether it’s about obtaining research funds.”—(male, anesthesiologist, Hungary, major city)

Other interviewees, on the other hand, consider the general features of some (even the abovementioned) countries to be repulsive and discourage them from emigrating.

The living conditions in Hungary are generally judged negatively by the interviewed health workers, and they are specifically considered to be a push factor. According to the interviewees’ narratives, the average life expectancy at birth is generally low, in addition, health workers in Hungary can expect a shorter life (compared to the general population), it is difficult to maintain a home, there is a fear of the collapse of the pension system, it is considered very unfair that one has to do a lot of overtime for a higher income, and this is related to workplace stress too. For others, experiencing the intrusion of politics into everyday (private) life and being disillusioned with this phenomenon are also push factors:

“The statistics in Hungary are quite bad. Just read about how many surgeons reach retirement age. Not too many. I want to live until I’m 80. I’m not saying that everyone dies before it, but there is this moonlighting, we go to the private practice and continue [working] there.”—(male, orthopedic and accident specialist, Germany, small town)

An important aspect regarding quality of life is the living environment, which is a term defined by the interviewees in various ways. They usually referred to the type of settlement (e.g., big city, small town, village), but they also mentioned specific settlements in connection with migration and even smaller local spaces such as districts or streets.

According to some interviewees, living in a small town or in a rural area (a village) provides them with a peaceful life, so they would not move away under any circumstances. For health professionals belonging to this group, family atmosphere and the feeling of home are highlighted, which can be such strong anchoring factors that even domestic migration is considered unthinkable. Others experience this environment as “boring” and “peripheral”, which can be a motivation for emigration or at least domestic migration. The situation is similar with urban environments: some people are attracted by cities because of the numerous opportunities or their central location; others are repelled by the crowds characterizing urban centers, and they think that too large settlements are unfavorable. In the narratives, the immediate living environment (e.g., neighborhood, street) also appears as a bonding element, the positive aspects of which are emphasized (e.g., silence, tranquility, neighbors).

When talking about specific settlements, the interviewed health professionals usually mentioned the advantages of these places. For example, some settlements (these are mostly small- or medium-sized towns) have an “appropriate size”, where everything is easily accessible, whereas in the case of other settlements, the interviewees acknowledged other positive features such as livability, beautiful surroundings, orderliness, and good transport. Furthermore, in other settlements (especially larger ones), the wide range of services can be a pull or retaining factor:

“So, when you have a medical school three bus stops away, why would you go anywhere else? When you can find a job three bus stops away, again, why would you go anywhere else? If your friends are here, your family is here, why would you go anywhere else? So, I spent my life in a solid, small-town, comfortable environment until I was 36 years old.”—(male, dermatologist, Hungary, major city)

Self-realization also plays a role in migration-related decisions for several interviewees (e.g., time that can be spent on research and education). It can also be observed that self-realization can be possible in their current life situation without migration, as interviewees generally reported that they were satisfied with their life in Hungary and could live a full life there. In the interviews, the smallest scale of quality of life, linked to the micro-scale of the individual, is usually related to the experience of a life situation or a macro-level factor. For some, for example, existential, physical, and financial security are essential; therefore, escaping from a situation that is considered a threat to physical security (e.g., fear of armed conflicts or the criminalization of a big city) is important.

4.5. Family

Based on the empirical results, family relations and values, as well as family-related life situations, play important roles in the migration of the interviewed health professionals. During the analysis, by “family” we mean the nuclear, elementary family unit.

In the interviews, geographical distance from or proximity to the family is mentioned by the interviewees as a motivation for migration, and it is also one of the aspects of staying or re-migrating. One of the typical aspirations expressed by the interviewees is for the family to be physically together, i.e., geographically close to each other. Consequently, it prevents migration if the emigrating health professional has to leave their family and they cannot be in physical contact on a daily basis, and they cannot be a part of each other’s lives. This can also outweigh financial considerations and appears not only in international but also in domestic migration:

“I would have had the opportunity for professional development here at the state university, to go to Újvidék [Novi Sad] to study pediatric dentistry, but I didn’t want that because it’s 100 km far and I didn’t want to be so far from my family.”—(female, dentist, Hungary, major city)

The need to take care of family members typically emerged as a motivating factor for re-migration during the interviews:

“The third thing is that my family, my parents, lived here. My parents were already getting older, my father was approaching retirement, and I thought that I just didn’t want to leave them alone.”—(male, anesthesiologist, Hungary, major city)

According to the interviewees, family members actively influence migration decisions. It was common in the interviews that health workers used first-person plural pronouns when talking about the decision-making process (migration or stay):

“So, if we had gone, maybe it would have been just my husband and I. So, if the children hadn’t been born yet, and he had said that he had a job opportunity abroad, of course, I would have gone out with him. […] Well, the opportunity arose when the children were already there, and then the children didn’t want to go. And so, he took that into account. The majority decided.”—(female, graduate nurse, Hungary, major city)

The relationship between the family and migration is influenced by the question of schooling as well, when the dilemma arises whether the more familiar socialization environment of children in their home country is more important than the high-quality education that can be received through emigration. The interviews also show that it is more difficult for people with small children to decide in favor of emigration:

“There is only one thing in my mind that I will probably do, and that is when my children become teenagers, I want to go with them to an English-speaking country for a year, to learn the language and to see the world, and [to see] that there is a world outside of Hungary too. So, this will motivate me to stay abroad next time, so that my children will have English language skills and a vision for the future.”—(male, dermatologist, Hungary, major city)

Getting married is also an important motivation; the interviewees mentioned two typical cases in this respect. First, if the emigrant finds a partner abroad, marriage is an obstacle to re-migration, making this relationship an anchoring factor. Second, if the spouse is a foreigner (here: not Hungarian), this fact strengthens emigration:

“I remarried in 2014, my wife is American […] and I moved here to Minnesota and have been living here since 2014.”—(male, general practitioner, United States of America, village/rural area)

In conclusion, the results show the crucial role of the family in the migration of the interviewed Hungarian healthcare workers. In addition to the aspects mentioned above, the following factors are also notable: family members living abroad, the opportunities available in the migration target area for the family or one of its members, mobility or immobility as part of the family value system, and socialization. An important factor preventing migration is if one of the family members of the healthcare professional cannot find a suitable job or becoming employed would require too much sacrifice. In addition, the stage of life has outstanding significance in family-related factors: the same factor has a different effect in different stages of life.

4.6. Personal Network

Other personal relationships outside the (nuclear) family also play a decisive role in the migration decisions of the interviewed health workers. On the one hand, expatriate relatives, friends, and other acquaintances represent a social capital that improves job opportunities and facilitates integration abroad. On the other hand, patients, schoolmates, and friends strengthen the intention to stay as part of the secure and familiar environment.

Similar to family, friends, acquaintances, and colleagues can also serve as role models. For example, if there is an emigrant in this circle, it can increase the chance that the interviewee will also decide to migrate:

“The girl who was in Oxford for two years, she actually worked with my partner at the time as a health consultant, and since she knew my ex-partner and me as well, we got a little bit of inspiration that if she was in Oxford, then why we shouldn’t come to Oxford either.”—(female, nurse, United Kingdom, major city)

The prestige of emigrating and working abroad within the family and a group of friends can also be important: the opinions and attitudes of significant others influence the interviewees’ decisions:

“Because my father is a fairly well-known doctor, and working in England is such a big deal for the members of his generation.”—(male, general practitioner leaving the field, Portugal, small town not far from Lisbon)

Professional relationships can also play a dual role. If someone can work together with previous mentors, a positive experience can strengthen their stay because they interpret the emerging working relationship as a professional recognition and a step forward in their career:

“…and then I already knew that I wanted to stay in Szeged and continue working with my supervisor, and we are currently writing articles, and that is why I definitely wanted to continue my studies in Szeged.”—(female, physiotherapist, Hungary, major city)

However, previous professional relationships, e.g., joint projects and research collaborations, often form the basis of a migration decision. Due to the previous working relationship and the resulting mutual positive experiences, the jobs the interviewees apply for abroad may be at a former colleague’s institution, or such partners can help finding a job abroad.

Personal sympathy based on group identity and membership can be attractive too, such as belonging to the Hungarian diaspora. Ethnic Hungarians moving to Hungary from neighboring countries, for example, reported that the positive attitude in Hungary was attractive to them:

“Well, that’s why I went to the hospital because my colleagues supported me in 1987, in the late 1980s. The colleagues welcomed everyone who came from Transylvania, and not only in the medical field, with great empathy. I have also seen in other fields that the people from there are welcome. They [residents of the host community] are happy to… how can I say it… they are happy to help them.”—(male, pediatrician, Hungary, major city)

To conclude, personal networks provide security, whether it is about staying or emigrating; therefore, their role is important in migration decisions. Nevertheless, as the interviews show, this group of factors is also often connected with other factors.

4.7. Personality

The personality traits of the interviewees are of great importance, mostly in the relationships formed in the various spheres of social life, in the attachment to individual actors, and in general social embeddedness. The attachment can be of several types, and there are several nodes in the life of health professionals at which this attachment can be realized. Regarding the health professionals interviewed, such bonds develop mainly with family, friends, and patients:

“I say again: why should I leave my patients here? [Abroad] they can’t give as much … as much as … and I … I was very sorry when I left Nagykőrös.”—(male, dentist, Hungary, major city)

Bonding is an element that keeps some health professionals abroad even after emigration. Several interviewees emphasized that they liked the host environment and were able to integrate quickly, so this factor may have contributed to their settling abroad. The opposite of the above is when the interviewed health worker highlights the lack of attachment, which may encourage them to return to Hungary.

“Yes, and the environment too. It’s different to be there for a certain time, to feel good, but somehow, I felt alienated. I really, really like to go out and travel, as I still do, but when you stay in one place for a long time … I felt even more that everything is fine, but I don’t belong there.”—(female, dentist, Hungary, village)

However, there are interviewees who highlighted not simply the lack of attachment, but their cosmopolitan, world-traveling, exploratory personality traits in connection with migration. One theme that emerged throughout the interviews was that certain health professionals are highly adaptable and could settle almost anywhere in the world:

“I’m a rover, a cosmopolitan. I don’t care where I am, everything feels good if it’s a good system. I felt the best in Hungary.”—(male, surgeon, Netherlands, major city)

Not only geographical/physical mobility but also staying in or leaving the healthcare profession can be influenced by the personality of the health worker. Among such personality traits, the most important ones are dedication, helping others, and self-realization, as well as (local) patriotism and identity:

“…since I was young, I always wanted to help people somehow.”—(female, nurse, Hungary, village)

“I’m Hungarian … I’m a person connected to my home.”—(male, dentist/maxillofacial surgeon, Hungary, major city)

The interviewees also mentioned religion as a factor that helps them adapt and accept more easily if they have to live far from their homeland:

“As I’ve said, this Christian religious line is important to me … I practically saw it, you know, we can say … as if it was God’s will for us to emigrate.”—(male, general practitioner, United States of America, village/rural area)

In conclusion, the interviewed health workers’ personality-related factors show a relationship with other push–pull factors (family, personal relationships, workplace, quality of life). This is probably rooted in the socialization of the interviewees, that is, what groups, institutions, geographical places, etc. they have interacted with and what expectations they have faced during this process. The narratives of the interviewees about migration also suggest that any policy aimed at managing the health workforce should also take such personality traits into account.

5. Discussion

In this study, we addressed the following research questions: what factors influence the migration intentions of Hungarian health professionals and how do these factors operate? The analysis was conducted at the micro-level, i.e., at the level of the individual, the family, and the household. Furthermore, this study aims to contribute to the discourses related to the migration of health professionals from several aspects, confirming or extending the findings of previous research.

First, some of our results are related to the sustainability of healthcare. Among the three sustainability dimensions of healthcare mentioned in the Introduction, the social pillar has been examined in detail. The results confirm the several claims of previous studies, which refer to the interrelationship among the different dimensions of sustainability (e.g., [8,9]). Although our research focused on the human side of the three dimensions only, the other two also came up regularly in the interviews, showing their interconnectedness and overlapping nature. Regarding workplace environment, for example, factors such as high-quality equipment or the esthetic appearance of the workplace arose, whereas from the economic aspect, the interviewees talked about research and innovation opportunities. All of these contribute to the retention of the workforce and thus to more sustainable healthcare. One of the main contributions of our research is that we explored a segment of the social dimension of healthcare sustainability in depth, pointing out some connections between the underlying processes and background factors with relation to the dimensions of sustainability.

Another strand of our results is related to migration theories. According to some theories, there are rational reasons behind migration decisions (e.g., [54]). In several cases, our research proved the opposite, i.e., the decision to migrate is not necessarily rational, but it involves other (e.g., emotional) elements, as emphasized by other migration theories (e.g., [55]). Among our interviewees, especially those who decided to stay, there is a kind of fear of change, and this can be observed in the arguments for staying, even if this is not stated explicitly. Furthermore, previous research suggests that the influence of the individual’s family members and those living in the same household is essential in terms of mobility [51]. Our results also corroborate that the role of the family is prominent in the individuals’ migration-related decisions. According to the theory of social systems [56], immigrant workers are often at the bottom of the social hierarchy in their destination country; however, based on our interviews, this is not always the case. A possible reason for this phenomenon is that the health workers involved are highly qualified, and there is typically a shortage of such professionals in the host countries. Moreover, in some cases, emigration was associated with upward social mobility among the interviewees, as they managed to break out of the hierarchical environment of Hungarian healthcare, which is in line with some results from research of other CEE countries (e.g., [32]).

The third major topic to which our research is connected is migration motivations. According to the literature, financial incentives and income play an important, but not exclusive, role among the migration motives of health workers. Our research partly supports this, but the role of other factors is also prominent in the interviewees’ narratives. Studies from CEE have drawn attention to the outstanding importance of three factors in healthcare professionals’ migration decisions: income, working conditions, and training and career opportunities [26,27]. Our results confirmed the importance of these factors but also provides a more nuanced understanding of them.

The phenomenon of informal payments emerged as a specific factor regarding financial matters. Based on the literature, informal income, rooted in the state socialist regime, survived in Hungary even after the political changes in the early 1990s and supplemented the otherwise low official income of health professionals. Recently, the Hungarian government has responded to the situation, partly with the criminalization of this informal source of income, but the results of the reform are still dubious [73]. The contradictory role of informal payments is substantiated by the interviews; on the one hand, it keeps some health workers in Hungary by increasing their income, but on the other, it is a significant push factor for others because it is not in line with their moral values. This latter position was typical among the interviewees. Our findings are in line with those studies that highlight the contradictory nature of policies against informal income (e.g., [87,88]). Thus, a health policy should thoroughly understand and reflect on the motivations of workers to deal with the problems connected to informal income.

Based on our research, some of the most important push–pull factors in the migration of the interviewed Hungarian health workers are related to workplace well-being. A fundamental element of the sustainability of the healthcare system is the sustainability of the health workforce, and part of this should be the management of the mobility of health professionals and the improvement of their performance (e.g., [12]). Our results also confirm that the satisfaction of the workforce is very important to prevent them from migrating or changing their job. Compared to some previous studies (e.g., [28,29]), the role of personal relationships at work seemed to be more prominent in the interviews. Besides infrastructural and organizational factors, the interviewees emphasized the importance of local workplace conditions, interpersonal relationships, and workplace atmosphere. If the latter is considered unfavorable, it is a strong push factor, but a good workplace environment has a considerable anchoring effect.

Workplace atmosphere and leadership are usually among the mezzo-level factors considered in migration research (e.g., [59,62]), but in the present study, it was investigated how these are experienced by the individual; this is why we interpret them as micro-level factors. Since the interviews show that good performance is not always fairly rewarded in the Hungarian healthcare system, the system probably does not always promote workforce improvement. This can be a push factor, as the individual experiences the systemic problem without being personally motivated to work more efficiently.

Our results also point to the role of geographical factors and life-cycle events in migration decisions. Both two categories integrate the push–pull factors revealed among the empirical results, and they are also interrelated. These characteristics have been widely discussed in the literature [89,90,91,92].

Among the geographical factors, the role of distance was confirmed and nuanced by the research (e.g., [65]). In addition, the empirical results also shed light on the importance of other geographical aspects, such as spatial obstacles and their overcoming, local characteristics, and attachment to geographical places.

The role of geographical distance is fundamental regarding the interviewees’ migration since their spatial mobility usually occurs when some kind of an important resource is not available for them at the place where they live. The experience and perception of geographical distance appear in the narratives of the interviewees, so they can observe distance very differently. This subjectivity can be observed, for example, in the case of family-related push–pull factors. “Long distance” has usually negative connotations for the interviewees (e.g., distance prevented them from meeting their family often/seeing their children/taking care of their parents). It is common in the interviews that those who spoke about the importance of distance would feel that this would be the biggest sacrifice in case of emigration. On the other hand, “proximity” is considered as an advantage (e.g., being able to spend more time with relatives and friends). The location of geographical places is also important. For example, our results concerning push–pull factors related to quality of life revealed that central locations are valued due to good accessibility and available services and jobs, whereas the lack of these resources in peripheral locations is usually a disadvantage—these features can be related to the sustainability of cities and communities as well [9]. It also proved to be important what kind of geographical environment the interviewee comes from because this background influences their residential preferences. In general, attachment to geographic places, identity, and (local) patriotism seem to be connected to elements of personality and quality of life.

Life cycle (life course, stages of life) is the most integrative and comprehensive analytical category based on our results. In almost every analyzed category, the stage of life in which the interviewee faced the decision-making situation related to migration proved to be essential. According to the interviews, individuals experience and interpret the same event in different ways in each life stage (see also [93,94,95]). Several life-cycle events can be identified at which it is more likely that the interviewed health workers will have to decide regarding migration. The most important life situations of this kind are the completion of education and training, the search for a first job, marriage, having children, enrolment and education of children, divorce, and caring for elderly parents. The connection between life cycle and geographical factors is mirrored by the fact that different types of places and related services are important for the interviewees in different life stages. For example, when it comes to educating children or caring for elderly parents, the wider and generally higher-quality range of services available in urban areas is more attractive. Since individuals can give a different migration response to the same situation based on their own perspectives, this study also suggests that migration decisions come to the fore in certain situations, but their nature depends on micro factors.

The results show that the individual push and pull factors are closely related to each other, mainly through the two above-described, integrative categories: life cycle and geography. Thus, this study underlines the role of integrative approaches, such as the life-course analysis framework, in general [90,96], and with regard to health workers in particular [97]. Considering this, one of the advantages of our analytical categories is the detailed exploration of the processes behind each push–pull factor, and the current research could be well complemented by other, more integrative approaches. The push and pull factors in all the analytical categories we used can stimulate either migration or stay, demonstrating the complexity of migration attitudes and decisions, and the need to consider individual, subjective aspects (Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5, Table 6, Table 7 and Table 8).

Table 2.

The role of wealth and income in the migration decisions of healthcare professionals.

Table 3.

The role of workplace in the migration decisions of healthcare professionals.

Table 4.

The role of human capital in the migration decisions of healthcare professionals.

Table 5.

The role of quality of life/well-being in the migration decisions of healthcare professionals.

Table 6.

The role of family in the migration decisions of healthcare professionals.

Table 7.

The role of personal networks in the migration decisions of healthcare professionals.

Table 8.

The role of personality in the migration decisions of healthcare professionals.

Based on the interviews, various types of migration attitudes can be identified: besides the categories used during the selection of interview partners (emigrated, re-migrated, decided against migration), the “hypermobile” and the “determined non-mover” attitude have also emerged. For “hypermobiles”, migration is an essential part of their lifestyle and career path, while determined non-movers have a low intention to migrate due to their attachment ties or fear of unknown cultures and environments.

Finally, it is worth discussing the policy implications of this study, with special attention to the Hungarian context. Our results also support the idea that the role of the recently implemented policy measures in general appears to be contradictory. The Hungarian government intended to prevent emigration with administrative means, according to which, for example, students who graduated from medical schools are obliged to work in Hungary for a certain period of time. Based on our results, the effect of this measure is also controversial. Among our interviewees, there are people who accept it or are not influenced by it, as they do not intend to emigrate, whereas others prefer to face the negative consequences associated with breaking the regulations (e.g., fines) and emigrate anyway. Therefore, this measure is probably only partially able to fulfil the hopes of decision makers. At the same time, the Hungarian government also introduced incentives, such as raising the wages of doctors and improving the technical infrastructure of the health sector. In general, such measures are considered important but not sufficient by the interviewees, and their impact on the migration motivations of health workers seems to be less prominent than in other CEE countries (e.g., [28,29]).

Last but not least, the effects of the pandemic should be also mentioned. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, several measures were introduced in Hungary for a more efficient allocation of healthcare resources. During the epidemiological state of emergency, mobility and job changes (leaving healthcare, transitioning to the private sector) were administratively restricted, which were measures that required the centralization of decision making. Within healthcare, the reduction in autonomy and growing centralization may increase the willingness to migrate or leave the public sector, as individuals may perceive these changes as further worsening “well-being at work”. The measures described above temporarily slowed down the emigration and retirement of health professionals in Hungary, but the number of health workers who apply for the necessary certification to work abroad has increased again recently, i.e., the intention to emigrate seems to be growing again. According to the data, there is still a significant labor shortage in the Hungarian healthcare sector, as the supply of human resources is below the EU average [98] (p. 27). Therefore, although the effects of the reforms should be evaluated in the longer term, it is possible that the policy measures taken so far will prove to be insufficient and not properly targeted. Our position is that the results of this study can inform policy makers by showing that micro-level factors play an important role in the migration decisions of health workers. Therefore, it is necessary to consider these factors for the long-term sustainability of healthcare.

6. Conclusions

In light of existing research, this study, using data stemming from semi-structured interviews, focused on the following research questions: what factors influence the migration intentions of Hungarian health professionals and how do these factors operate? The use of a qualitative research method made it possible to analyze migration attitudes in a more detailed manner. The results show that the topic of migration affects all of the interview partners and all of them were considering the idea of moving; however, their conclusions were varying. Besides the types used during the selection of interview partners (emigrated, re-migrated, decided against migration), additional types of migration attitudes were identified during the analysis: the “hypermobile” and “determined non-movers”. Migration is an essential part of life and career for the hypermobile interviewees, while the determined non-movers have no intention to migrate at all.

Despite their overlapping nature, our analytical categories seem to be useful for the analysis, providing insights into the background of migration-related decisions. In addition to confirming the significance of income and wealth, the results also highlight the importance of family and working environment in the migration decision of healthcare professionals. In relation to family, the role of geographical distance and location seem to be a decisive factor in migration-related decisions. Regarding workplace, while most of the previous studies emphasized the administrative or infrastructural aspects, this research highlights the importance of the relations with co-workers; despite the developments made in workplace equipment, a bad work atmosphere can be a push factor. It is important to highlight that workplace-related issues are the consequences of systematic problems (e.g., stress caused by overwork, one-sided, top-down workplace hierarchies, etc.). Furthermore, geography and location in general seem to be relevant in migration decisions; the interview partners took into account the quality of life, amenities, services, and career opportunities that certain places (e.g., larger towns) provide. Due to the qualitative nature of the research and the overlapping categories, it is not possible to classify the factors according to their importance or quantify the results. However, family and life cycle seem to be the most important factors influencing migration-related attitudes and decisions.