Abstract

Indigenous understanding of sustainability is embedded in close relations to land and environment, Indigenous Knowledge systems, Indigenous epistemologies and ontologies, and Indigenous languages. However, the sustainability of Indigenous peoples’ livelihoods is significantly affected by various global change drivers. In the Arctic, Indigenous peoples’ livelihoods are impacted by environmental, social, and cultural changes, including climate change, environmental pollution, economic processes, and resource extraction. This paper aims to review and synthesize recent academic and gray literature on the sustainability of Indigenous communities in Sakha Republic, Northeast Siberia, Russia in the face of global change with a particular focus on land- and water-based traditional activities, native language, and the Indigenous Knowledge system.

1. Introduction

Indigenous understanding of sustainability is embedded in close relations to land and environment, Indigenous Knowledge systems, Indigenous epistemologies and ontologies, and Indigenous languages (often deemed as endangered) [1,2]. However, the sustainability of the Indigenous peoples is strongly affected by various global change drivers. The Arctic is facing environmental, social, and cultural changes that are partially or fully originated from outside, including climate change, pollution, global economic processes, and resource extraction [3]. The most remarkable global change driver in the Arctic is climate change, with temperatures rising four times as fast as the global average—a phenomenon called the Arctic amplification [4,5]. As a result of climate change, the Arctic is experiencing rapid transformation in its ecosystems, including the invasion of southern new species [6,7], a decline in numbers of the endemic species [8,9], permafrost degradation [10,11], coastal and riverine erosion [12], wildfires [13,14], and other changes that create existential threats for the Indigenous peoples. Indigenous livelihoods are directly affected by the loss of natural resources, diminishing traditional food security, difficulties in accessing land and sea, growing weather unpredictability, and other climate-driven factors [15,16].

The impacts of climate change in the Russian Arctic are likely more intense compared to other Arctic regions due to its massive territory, wider and deeper permafrost coverage, large wetland areas, and intensive industrial development. In addition to climate-induced changes, Arctic Indigenous communities’ livelihoods are compromised by other global change drivers such as sociopolitical transformations, industrial development, colonization, cultural assimilation, and language loss. For example, fishing regulations in Russia have undermined Indigenous communities in the Arctic Sakha Republic by imposing quotas and temporal limitations and restrictions in fishing gear size [9]. Extractive industries in Russia construct massive infrastructural facilities in close proximity to grazing fields, hunting or fishing grounds, and pass along the water bodies or migration routes of wild animals [17,18,19,20]. Understanding the response of Arctic Indigenous communities to global change is crucial because Indigenous communities and their livelihoods are highly dependent on ecosystems for food, clothing, shelter, and spiritual wealth [21,22]; their livelihoods are marginalized [23], and Arctic ecosystems are the most fragile and vulnerable [24].

Research of Indigenous sustainability is limited, although there is a growing academic literature and attention in the media on this topic [25]. It is necessary to examine Indigenous sustainability since the Indigenous peoples have been the stewards of their environment for millennia, and as the world is “facing potential environmental catastrophe [due to climate change] and not in the distant future,” they are “the only communities standing between humankind and the realization of such a catastrophe” [26]. Indigenous peoples inhabit the lands which contain 80% of the world’s biodiversity, which they have been protecting and living sustainably with for millennia; therefore, Indigenous sustainability research will help to tackle climate change [27]. Moreover, Indigenous sustainability research will help to develop adaptive strategies and policies at the global and local levels, and thus advance climate change mitigation [28]. In addition, the current tense geopolitical situation in the world has led to the cancellation or suspension of many international research projects on global change impacts on Indigenous communities in the Russian Arctic, and this pause thus may exacerbate knowledge gaps in the future.

This paper aims to review and synthesize recent academic and gray literature on the sustainability of Indigenous communities in the Republic of Sakha in the face of global change. We place a particular focus on land- and water-based traditional activities, native language, and Indigenous Knowledge systems. To examine how the sustainability of Indigenous communities in Sakha Republic has been affected by key global change drivers (climate change, economic development, and institutional transformations), the paper will first discuss the concept of Indigenous sustainability (in contrast to the Western conceptualizations) and address Indigenous dimensions of sustainability, and will finally describe global change drivers and their impacts on the Indigenous peoples.

1.1. Indigenous Understanding of Sustainability

The concepts of sustainability and sustainable development have become widespread after the release of the United Nations World Commission on Environment and Development’s Brundtland Report in 1987, where sustainable development was defined as “meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” [29]. The main idea of sustainability at that time was based on the assumption that global environmental issues stemmed from extreme poverty in the Global South and unsustainable consumption and production in the Global North. The report has raised an awareness of the importance of the interrelations between the economy and its dependence upon natural resources, and has called for a stewardship for the future and the environment. However, the report has been strongly criticized for paying too much attention to economic development rather than human well-being. Graf et al. argued that the Brundtland Report “vindicates the hegemony of the classes and interests, which are the present beneficiaries of the International economic order” [30]. Crate criticized the report for being a “dominant, western top-down economic worldview that bases ecosystem management on generalized prescription rather than specific context” [31]. Sondegaard condemned the Brundtland Report for excluding culture and traditions from the concept, which may have a crucial role for Indigenous peoples as they depend upon natural resources for livelihoods through traditional practices of hunting, fishing, herding, and gathering [32]. Furthermore, although the current modified definition of sustainable development may have improved, its goals still remain exclusive, especially in regard to the Indigenous peoples, and strives to satisfy the global community.

Alternatively, Degai and Petrov suggest to indigenize the sustainable development, and UN Sustainable Development Goals in particular, by creating five new goals based on Arctic Indigenous peoples’ knowledge and longing for sustainable development, which include sustainable governance and Indigenous rights; resilient Indigenous societies, livelihoods, and knowledge systems; life on ice and permafrost; equity and equality in access to natural resources; as well as investments in youth and future generations [33].

Nevertheless, sustainability research lacks flexibility and local context [31] as local and Indigenous understandings of sustainability and sustainable development may differ significantly from that of Western or “global” views. Graybill and Petrov define Arctic sustainable development as “the development that improves health, well-being and security of Arctic communities and residents while conserving ecosystem structures, functions and resources” [34]. Sustainable development in the Arctic should be conceived as a decolonial concept that pursues Indigenous communities’ own sustainable goals and aims to empower them to drive their own destinies [33,35].

There is no word for “sustainability” or “sustainable development” in Indigenous peoples’ worldviews. However, similarly to the Brundtland Report, the Indigenous concept of sustainability aims at future generations to which Indigenous Knowledge, worldviews, cultures, and traditions are transmitted. Indigenous understandings of sustainability are holistic and may not be compatible with Western understandings, which are Eurocentric and reflect the priorities of capitalism [36]. Moreover, Western conceptualizations of sustainability separate humans from nature and emphasize the maintenance of productivity, conservation, and other object-like relationships with nature. In contrast, reciprocal relations between humans, non-humans, and nature itself are key components of Indigenous understandings of sustainability, which are determined by the surrounding environment and which the Indigenous people are obliged to steward the land through daily spiritual and physical practices and interactions [33].

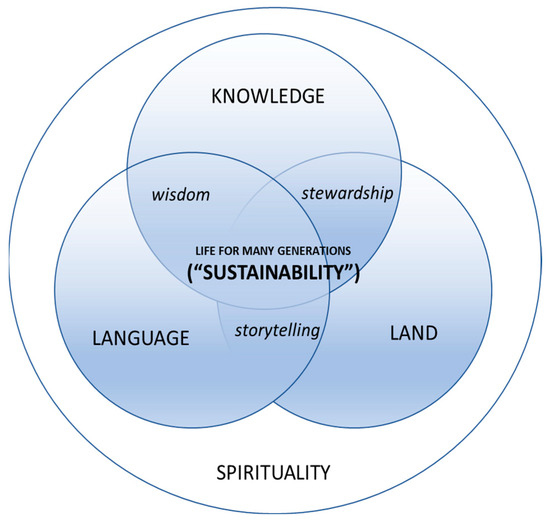

Unlike the Western concept, the Indigenous concept of sustainability highlights a deeper understanding of the relationships between humans and land. This relationship is protected by customary laws and an understanding of this relationship is possible through native language. Thus, Indigenous understanding has three dimensions: land, language, and the knowledge system [2] (Figure 1). Land provides subsistence, which is a key aspect of Indigenous sustainability as Indigenous peoples have been for millennia dependent upon their environment for food, shelter, transportation, and well-being through hunting, fishing, herding, and gathering [22,37]. Moreover, land usually referred to as Mother Earth, is perceived as a source of cultural, mental, and spiritual well-being. Language presents an integral part of all Indigenous cultures and serves as a treasury of Indigenous Knowledge embedded in native languages and transmitted to future generations [2]. Indigenous languages constitute ancestral wisdom, and if lost or not transmitted, then this wisdom is lost to future generations as well [38]. Ferguson and Weaselboy argue that language and land are interconnected and inseparable in Indigenous understandings of sustainability as language derives from the land, operates within and through the land, and is inherently connected to human and non-human beings on that land [39]. Furthermore, mental and physical well-being of the Indigenous peoples depends on the maintenance of Indigenous languages and sustainable relationships with the land [39]. The Indigenous Knowledge system is central in pursuing Indigenous sustainability. Pre-colonial Indigenous societies were sustainable mainly because of their advanced understanding of nature gained from their daily interactions with the environment, which helped them to sustain livelihoods and adapt to changes for millennia [40]. Indigenous Knowledge systems and their related conceptions (e.g., Traditional Ecological Knowledge) have served the Indigenous peoples for centuries by facilitating considerate and thorough human–nature relations, thereby inducing environmental sustainability [41]. Indigenous Knowledge enables stewardship of land, a reciprocal relationship of respect and care for things and beings created to inhabit Mother Earth. In Sakha worldview, language is key to understanding Indigenous Knowledge, and transmitting it to future generations through many traditional rituals with spirits, ontologies, and ecological practices take place in Sakha language, which thus helps to maintain the sustainability of the Sakha people [42]. Finally, and very importantly, Indigenous understandings of human–nature relations are underpinned by Indigenous spirituality manifested through ceremony and reverence to the human and non-human worlds. Spirituality percolates knowledge and language, giving meaning and value to the relationships with land in the past, present, and future.

Figure 1.

Indigenous understanding of sustainability.

Although Indigenous understandings and perceptions of sustainability may be somewhat universal for most of the Indigenous peoples worldwide, localized definitions remain necessary as Indigenous communities differ from each other despite the strong sense of solidarity and empowerment among all Indigenous peoples. Crate distinguishes two key determinants of Indigenous sustainable development in the Arctic: self-governance and self-determination [31]. There are relatively successful examples in this regard in the Western Arctic: the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (1971), Greenland Home Rule (1979), Sami Parliament (1989), and the foundation of the Nunavut Territory (1999). However, when it comes to the Russian Arctic, it looks quite the opposite. Sustainable development in the Russian context has more economic meaning and aims to gain more material well-being (e.g., [43]). Moreover, it is difficult to find an appropriate equivalent term for “sustainable development” in Russian, and it would be directly translated as “stable development” due to the differences in people’s worldviews and compatibility of the concept in the Russian context [44].

The literature addressing sustainability and sustainable development in Russia largely focuses on socioeconomic development and environmental situation and pays less or no attention to the Indigenous components of sustainability. Not surprisingly, the literature lacks place-based Sakha conceptualizations of sustainability. In the context of Bülüü communities in western Sakha Republic, Crate defines sustainability as “the building of local diversified economies, communities, and health via strong local leadership, a shared vision to work toward common goals, the reinstatement of local knowledge, and rights to land and resources” [31]. However, Crate’s interviews posed questions from a purely Western perspective in its initial definition introduced by the Brundtland Report, excluding Indigenous elements mentioned above, and focusing more on economic development, empowerment, health, and state support. Ferguson viewed the sustainability of the Sakha people through language, which is perceived as animate (having a spirit) and sustaining the relationship as well as a source of sustenance for the speaker [45].

1.2. Global Change Drivers

Direct and indirect drivers of global change affect the sustainability of the Arctic Indigenous peoples. Direct drivers of global change include climate change, habitat degradation and restoration, pollution, biological invasions, and overexploitation; indirect drivers encompass governance systems and institutions, economic development, international trade and finances, technological development, population, and demographic trends, as well as human development [46]. Indirect drivers impact social–ecological systems through altering direct drivers [47]. This review will focus on three key drivers impacting the sustainability of Indigenous communities in Sakha Republic: climate change, governance systems and institutions, as well as economic development.

Climate change is more intense in the Arctic and the warming rate has been four times higher than on the global average since 1979 [5]. Mean air temperature in the Republic of Sakha has increased over the last decades and so has the mean annual precipitation [48]. As a result, permafrost thawing in many Sakha uluuses (districts) has intensified; devastating floods have also become more frequent; the area and number of catastrophic forest fires have soared as well [49,50,51]. Permafrost thawing jeopardizes local infrastructures; frequent floods damage settlements; forest fires destroy millions of hectares of territories, and thus cost the economy billions of rubles [11]. Furthermore, climate change-related emergencies have negatively affected ecosystems and Indigenous livelihoods: the northward expansion of southern invasive species forced out native endemic species; the immigration of taiga predators threatens traditional economies and local people’s lives and health; warming causes accidents with fishers or hunters [6]. In addition to climate-induced changes, Indigenous communities in Sakha Republic are affected by governance systems and institutions as well as economic development.

Institutional transformations, and in particular, Soviet policies and practices of collectivization, sedentarization, Russification, boarding schools, ban of shamanism and other colonial instruments brought about the decline in traditional practices, attrition of native languages, assimilation, issues with ethnic identity, and erosion of the Indigenous Knowledge. Current governance models in the Russian Arctic are very centralized, top–down, and hierarchical, with limited bottom–up feedback loops and effective communication mechanisms. For example, fishing regulations in Russia imposed restrictions on Indigenous fishers, which are often inappropriate and challenging [9]. Russia’s laws, regulations, and other governance instruments are relatively inflexible, although often are not enforced or circumvented. Although the Sakha Republic was able to develop its own regional legal frameworks that are more responsive to regional needs, including those of the Indigenous communities, the effectiveness of these governance innovations is still limited by the federal system and is increasingly curtailed [52]. The Federal law amendment on Indigenous languages adopted in 2018 may eradicate Indigenous languages, traditions, and knowledge systems as they have become optional or have lost the status of instructional language at schools [53]. The ongoing process of creating Indigenous people’s registry with very strict definitions of indigeneity will also likely impact the Indigenous communities, especially small ethnic groups [54]. Harsh economic conditions for practicing traditional activities of reindeer herding, hunting, or fishing are unfavorable, and therefore many young people prefer collecting mammoth tusks, which are much more profitable [55]. In this case, traditional subsistence practices might experience decline or loss [56].

Economic development implies the consumption of natural resources, which in one way or another affects ecosystems and the Indigenous peoples [57]. Global extractivism has a sizable and long-existing footprint in the Arctic that has recently become even more dramatic. Extensive extraction of oil, gas, diamonds, and gold in Sakha Republic has inflicted damage to grazing fields, hunting, and fishing grounds important for traditional practices of the Indigenous peoples [19,20,58]. Moreover, construction of pipelines, open pit mines, and other infrastructural facilities generated stacks of undisposed hazardous materials, abandoned and misused equipment, excessive waste, and other human footprints on ecosystems [18]. The interplay of these dramatic events significantly affects the sustainability of the Indigenous peoples in Sakha Republic and it is necessary to understand their response to global change impacts.

1.3. Indigenous Communities in the Republic of Sakha

This literature review is based on case studies in the Sakha Republic, Northeastern Siberia, Russia (see Figure 2), where various Indigenous communities reside. The Sakha Republic is the largest province in Russia based on its territory covering three million square kilometers (18% of the Russian Federation); however, the population is scarce, with only one million people living in the region. The Sakha Republic has a vast area with diverse biomes and ecosystems. A large portion of the region is covered by taiga forest (70%), the rest is occupied by tundra, forest-tundra, as well as Arctic desert. The entire area sits on the permafrost [59]. Permafrost makes ecosystems in the region fragile and less resistant to external effects of global change [60]. The ecosystems in Sakha Republic are represented by native endemic plant and animal species, many of which are endangered and protected.

Figure 2.

Republic of Sakha. Image: Semyon Drozdetsky.

Indigenous population in the Republic of Sakha accounts for 54% of the total and comprises Chukchi, Dolgan, Evenki, Eveny, Sakha, and Yukaghir, with Sakha being by far the largest group. The concept of indigeneity is a contested issue in Russia and only ethnic groups numbering less than 50,000 are considered as Indigenous in the official documents. Larger ethnic groups such as Sakha (whose population totals 466,500 people as of 2021 [61]) are deemed as titular, and do not have equal rights as the so called “numerically small Indigenous peoples of the North, Siberia and Far East” [62]. However, International organizations such as the United Nations and the International Labor Organization advocate the right of self-identification as the major criterion of indigeneity, and so do the authors of this paper, an Indigenous Sakha scholar and a western scholar as an ally.

Most of the Indigenous peoples in the Sakha Republic work in public sectors of education, health care, and governance; some people are employed in extractive companies, services, and trade, and a small number of people are engaged in agriculture. Besides official employment, many Indigenous citizens practice traditional activities of hunting, fishing, gathering, and herding. There are also individuals who pursue these traditional practices professionally. People fish chir (broad whitefish) (we used Sakha terminology throughout the paper since Sakha is the predominant Indigenous language in the study region; however, we recognize that other Indigenous groups have alternative terminologies), muksun (Arctic whitefish), sobo (crucian carp), sordoŋ (northern pike), hunt kuobakh (hare), kus (duck), khaas (geese), kiis (sable), gather djedjen (wild strawberry), khaptaghas (red currant), moonn’oghon (black currant), and tellei (mushroom). Horse and cattle breeding is an important subsistence economy in Sakha. Breeding of horses and cattle is predominantly practiced in central and western uluuses of Sakha Republic, whereas reindeer herding can usually be found in northern tundra and southern taiga areas. These activities are not only important as a subsistence but also as an economy, transportation, clothes, shelter, social cohesion, cultural, social, and spiritual identity [22,63,64]. The Sakha Republic is rich in fossil fuels and mineral resources. Diamond reserves account for 80%, uranium—61%, and oil and gas—35% of total reserves in Russia [65]. Consequently, Indigenous livelihoods are strongly impacted by past and present extractivism.

1.4. Methodology

The authors of this paper are Indigenous and non-Indigenous scholars who have close relationships to the study area. Stanislav Saas Ksenofontov identifies himself as Sakha who was born and raised in the Republic of Sakha on the pristine Amma river. All the issues described in this article concern Stanislav personally as his unconditional care for his homeland continues to thrive. Andrey Petrov is a Western scientist who has conducted many years of research in the Arctic, working closely with the Indigenous peoples. Both authors have Western training in geography and employ decolonial Indigenous approaches to research.

The scope of this review is limited to three global change drivers and one specific region. Therefore, the selection of academic papers was based on two criteria: (1) regional—the papers addressed global changes in Sakha Republic; (2) temporal—the papers addressed global changes over the last 10 years. Sources include academic pieces of published literature and their references, gray literature found on various governmental websites and media platforms as well as autoethnographic accounts of SK. The languages of sources were Sakha, Russian, and English. While there is a relatively extensive literature on the topic of non-Indigenous researchers, the authors aimed to select sources mostly of Indigenous (Sakha) scholars.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Climate Change

Climate change presents one of the most significant global change drivers affecting ecosystems and Indigenous peoples’ livelihoods in the Arctic (Table 1). Warming in the Arctic is four times more intense than on the global average [5] and Arctic ecosystems are very susceptible to climatic changes, while Arctic Indigenous communities are already marginalized by colonialism and thus are compromised in their ability to respond and adapt to a rapid change. Overall, the research on climate change in Sakha Republic demonstrates the mean annual air temperature increase across the entire region. Over the last several decades, mean annual air temperature has grown by 1.1 °C to 2.1 °C [66]. In June 2020, the record summer temperature of 38 °C was reported in the northern town of Verkhoyansk. Annual precipitation amount across much of the Sakha Republic is increasing. The positive trend of annual precipitation is observed in southwestern and northern uluuses [67]. However, a cyclicity of wet and dry seasons also affects the precipitation patterns [49]. Some uluuses witness little rain in summer, which negatively impacts traditional practices and is unfavorable for extinguishing forest fires. Rain on snow events in October have become more frequent with detrimental impacts on foraging of reindeer and horses. For example, in 2019, due to late rain in October when snow had already fallen, an ice crust was formed, which blocked access to food for reindeer and horses as they dug out the grass under the snow [68].

Table 1.

Climate change impacts on sustainability of Indigenous peoples in Sakha.

Many studies revealed the frequency of extreme events such as floods, forest fires, and permafrost thaw as a result of climate change [50,51,69,70,71,72]. Between 2012 and 2022, several massive floods occurred in Sakha Republic. Floods caused direct and indirect damages. Among direct damages, one can distinguish damage and destruction of residential industrial buildings, roads, power and communication lines, loss of livestock and crops, destruction and damage of raw materials, fuel, food, feed, and fertilizers, as well as costs imposed to a temporary evacuation of people and transportation of supplies. Indirect damages include purchase and delivery of food, clothes, medicines, building materials, machinery, livestock forage, suspension of industrial and agricultural production, and a worsening of people’s living conditions [72]. One of the most recent devastating floods took place in SK’s home uluus of Amma in 2018, when many households in several villages lost their possessions, including houses, furniture, and livestock. His fellow community members of Amma have not witnessed such a disastrous flood for decades. In the village of Sahyl, many houses were swept away by huge blocks of ice (Figure 3). Tananaev et al., in their study, reported that this exact flood was caused by the formation of an ice jam which occurs when the fluctuation of warm and cold temperatures in spring intensifies snowmelt and enhances ice cover stability [50]. Estimated economic damage from this flood to the Amma community accounted for RUB 5.1 billion (USD 75.1 M as of 2018) [48]. Similar disastrous floods take place annually in other Sakha uluuses with the only difference being that the places where floods occur and economic losses or social implications vary every year. In July 2022, heavy rainfall in Üöhee Jaaŋy uluus in north Sakha Republic caused a catastrophic flood which destroyed houses, schools, hospitals, and kindergartens in several settlements, inflicting economic losses of millions of rubles. Agricultural losses and damages included 18 mares, 2 stud horses, 11 foals, 38 hens, 3.53 ha of potato crop area, 626 tons of hay, and 11 hay harvesting fields, which accounted for RUB 11.2 billion (USD 180 M as of 2022) [73]. In order for livestock to overwinter and survive, commercial and subsistence breeders needed thousands of tons of forage. As these cases demonstrate, frequent climate-induced floods enormously affect traditional practices and social infrastructures of the Indigenous communities in Sakha Republic. To recover from these emergencies, the localities depend on millions of rubles of government aid.

Figure 3.

Houses swept away by huge blocks of ice in the village of Sahyl, Amma uluus, 2018. Photo by Nikolaeva L.

Another serious climate change-related issue over the past decades in the Republic of Sakha is forest fires. Between 2017 and 2020, more than 2000 forest fires occurred in the region [74]. The largest forest fire in recent years took place in 2021, when 17 million ha of forest and other land mass have burnt down over the summer, releasing tons of CO2, decreasing air quality of many settlements hundreds of times than recommended by international standards and affecting the health and well-being of many people [75]. At the time, there were 267,000 fire hotspots, which was about 5.8 times larger than the average number of forest fires since 2002 [76]. Most of the forest fires occur due to dry thunderstorms, anthropogenic factors (including arson), and agricultural burnings [71]. However, droughts, scarce precipitation, high temperatures, dry weather, strong winds, and extremely low humidity of air and soil are deemed to be the major reasons for many forest fires [77,78]. Forest fires, first of all, impact the environment. The dying out of trees and microorganisms, the burning of grasses, shrubs, mosses, and lichens, the damaging of soils, soil depletion, permafrost thaw, and biodiversity loss are only a few of the environmental consequences of forest fires [77]. Moreover, Arctic ecosystems are fragile, and it may take decades for tundra and forests to fully recover from the damage. The forest fires bring about direct losses of houses, backyard buildings, livestock, land, as well as significant impacts on human health, fodder for animal husbandry, fisheries, and agriculture [51].

Climate change causes permafrost thaw. Permafrost thaw significantly affects Indigenous livelihoods, resulting in landslides to roads that connect settlements, and thus blocking transportation of people, food, and other important supplies. It also damages houses and other buildings, posing threats to human health and life and consequently result in a reduction in areas suitable for construction and agricultural use [79]. For instance, in summer 2013, as a result of heavy rainfall and permafrost thaw, a massive landslide damaged the road between SK’s home village of Amma and Yakutsk—the capital city of Sakha Republic—which left Amma residents without a transportation network and grocery supply. Permafrost thaw floods buluus (traditional ice cellars) in Sakha Republic used for the storage of harvested food (fish, game), fermented food, and blocks of ice for drinking water [80]. This complicates the utilization of the buluus and many households abandon them. Permafrost thaw also waterlogs or deforms grazing and hay harvesting fields, turning them into lakes or complex terrain, thereby making it difficult to practice cattle and horse breeding [81] (Figure 4). Many households either buy hay for winter forage or quit practicing cattle and horse breeding. Doloisio and Vanderlinden identified categories of permafrost thaw impacts on various aspects of livelihoods in Sakha Republic, including impacts on natural resources (rivers, soils, mammoth tusks, flora, and fauna), impacts on infrastructure (roads, buildings, and pipelines), impacts on health and mental well-being, and impacts on Indigenous Knowledge [56]. Thawing cemeteries, increasing numbers of mammoth tusks on the ground, or forced displacements induced by permafrost degradation transform not only the material and physical environment, but also, and most importantly, cultural landscapes, symbolic representations, and emotional ties to the native land filled with memories and life experiences, and thus “might lead to an occasional or irreversible inner fragmentation and socio-cultural rupture” [54].

Figure 4.

SK observed a dramatic permafrost thaw and land deformation in his home uluus of Amma, where the land used to be flat in the 1990s and has become deformed when he last visited his hometown in 2019.

2.2. Economic Development

Economic growth entails, among other things, natural resource consumption largely driven by outside actors and global demand [57]. The extractive industry is a major actor in the Arctic and presents both opportunity and threat to the Indigenous peoples. Sakha Republic is rich in globally needed natural resources and many Russian state-controlled extractive companies operate in close proximity to Indigenous communities who practice traditional reindeer herding, fishing, hunting, gathering, and cattle or horse breeding. Many companies provide employment opportunities for local people, share benefits or compensate for damages to ecosystems, and make agreements on corporate social responsibility with local communities [82]. However, even if formally compensated, these damages are profound, benefit sharing is minimal, tax revenues are transferred only at the construction stage, local employment is limited in favor of fly-in-fly-out workers, and access to roads is complicated via the travel permit system [83].

Oil and gas large-scale megaprojects built to connect resources to global markets, such as the “Power of Siberia” (PoS) and “East Siberia—Pacific Ocean” (ESPO), imply the construction of infrastructural facilities along their routes in south and west Sakha Republic (Figure 5), which is thus expected to affect ecosystems and Indigenous communities. Yakovleva reported that the construction of the ESPO pipeline and the railway in Aldan uluus in the south of the Republic of Sakha had a negative effect on hunting, reindeer herding, as well as the migration of animals and fish [20]. Furthermore, specific natural characteristics of the region (e.g., permafrost, seismic activity, formation of glaciers, and floods) may cause the damage of pipelines along the route and consequently result in oil spill [60]. Oil leakages at the ESPO station in Ölüökhüme uluus in west Sakha Republic occurred in 2006 and 2010 as a result of human error during repairs [84]. Later, in 2018, researchers from the Oil and Gas Institute of Sakha Republic reported high concentrations of oil contamination in soils [85]. The PoS has affected many Indigenous communities in Aldan and Nüörüŋgürü uluuses in south Sakha Republic by disrupting traditional lands, migration routes of reindeer and wild animals, as well as traditional harvesting and herding practices [58]. Moreover, the project management has not provided an expected number of new employment contracts with the local people as initially promised by the Russian energy corporation Gazprom [18]. Another example demonstrates that the development of the Northern Sea Route along the coast of Sakha Republic has resulted in ecosystem degradation, the loss of fish stocks and reindeer pasture, as well as a decline in marine and terrestrial subpopulation important for the traditional economies of local Indigenous peoples [86]. Furthermore, tremendous in-migration of labor force from other regions during industrialization periods in the 1930s and 1950s caused a decline in traditional values, environmental ethics, and de-ethnicization of Indigenous Peoples, which significantly affected the sustainability of Indigenous communities [87].

Figure 5.

Routes of PoS and ESPO in Sakha Republic. Image: S. Drozdetsky.

Land in Russia, including the territories for traditional practices, are owned by the federal government and Indigenous communities are allowed to utilize their traditional lands (so called TTP—“Territories of Traditional Nature Use”) free of charge; however, the registration process to claim the use of land for traditional practices is complicated and there are bureaucratic hurdles around registration [20]. Forest land auctions have become another factor to affect the availability of traditional land use territories and hunting grounds, which negatively impacts traditional activities and limits access of subsistence resources [88]. Forest land auctions in Russia imply land rentals for various activities, including logging, commercial harvesting, and industrial extraction, and auctioneers accept applications from both individual entrepreneurs and commercial organizations from all over the country. Thus, open auctions of forest land may make it possible to legally exploit traditional lands of the Indigenous peoples for up to 49 years in favor of commercial organizations and individuals. In 2019, the Russian logging company from Irkutsk oblast rented land in Aldan uluus on the upstream of the Amma river to cut down trees and export them to China. When SK learnt about this, he started a campaign against deforestation and they were able to stop the company’s activity in the region. However, in 2022, the loggers came back and started cutting trees in the area. The potential damage from logging is expected to be significant, especially with respect to the clean and fragile river of Amma and surrounding forests. In 2020, an Evenk hunter from Aldan uluus was arrested for illegally hunting on public territory that is meant for common use and not allowed for traditional practices, although the area was historically inhabited by Evenk hunters and reindeer herders. The large portion of these traditional territories were converted into lands of common use by regional authorities in order to eventually grant licenses to extractive industries to operate on these lands [89].

2.3. Governance Systems and Institutional Transformations

Governance systems and institutions shape the societies’ organization and functioning. In this review, we focus on governmental decisions originating outside of the Indigenous regions that affect the sustainability of Indigenous peoples’ livelihoods, namely policies of the Soviet regime, fishing and hunting regulations, and policies on native languages. In broad terms, these institutional arrangements and policies reflect the practices of global colonialism that can have various forms and manifestations, but invariably imposes externally driven governance regimes across Indigenous lands and territories.

Policies introduced during the USSR have significantly affected Indigenous peoples’ livelihoods in the Republic of Sakha with long-lasting consequences for many generations to come. One can distinguish five major Soviet policies that have become life-changing for many Indigenous peoples: (1) collectivization in the 1930s when many Indigenous households forfeited their reindeer and other livestock [90]; (2) forced sedentarization in the 1950s when many nomadic families had to settle in villages [91]; (3) the policy of eliminating “unpromising villages” in the 1950s and 1960s when smaller settlements were shut down and relocated to larger ones [92]; (4) the Russification of the education system in the 1950s when the instruction language in most ethnic schools was Russian [93]; and (5) the dissolution of the USSR in 1991. All these policies and events impacted not only traditional practices of Indigenous peoples, but also cultural, mental, and social well-being and sustainability [94,95,96]. As a wealthy peasant who possessed a farm, SK’s great-grandfather in Amma had lost his livestock and all of his means during collectivization. Not wanting to give away his belongings and tortured for several days by the Bolsheviks for that, SK’s great-grandfather eventually killed himself. In order to hide his family from the Bolsheviks, he asked his children not to contact each other. The children had lost their contacts since then. In 2019, SK discovered that his classmate was in fact his cousin, which meant that he had spent 37 years unaware of his own relative. Sedentarization brought about a loss of familiarity with particular landscapes and adaptation to new, more limited territories, including the decay of nomadic traveling skills and a lack of ability to adjust to new living conditions in a house after leaving a tent [97]. As a result of the policy of “unpromising villages”, many families had abandoned their homes and experienced not only economic costs and damage, but also social difficulties such as a heritage disruption and a loss of roots [98]. The Russification brought about a native language attrition and loss of native ethnic identity as many children had to study in Russian at a local or at a boarding school [99]. The USSR collapse created new challenges to Indigenous peoples, especially those practicing traditional activities, as transition to a new market economy had terminated central state support and inaugurated new governmental regulations [9,100,101]. Soviet policies also caused cultural assimilation, Christianization, and the suppression of shamanism, which in turn had resulted in a loss of spirituality among many Indigenous peoples in Sakha Republic.

The fishing regulations introduced after the dissolution of the USSR imposed fishers with quotas, temporal restrictions, and limitations on fishing gear size. The quotas are an allocated number of the fish per person or community by weight, temporal restrictions imply a ban of fishing for a month in spring or autumn, and limitations on fishing gear size entail the utilization of only certain types of fishing tools. Fishers in the northern Sakha Republic’s uluuses of Bulun and Allaikha criticized the fishing regulations and policies for being problematic as they were developed and implemented without taking local Arctic conditions into account [9]. Overall, the federal government designs regulations first and then they are adapted to the local conditions by regional authorities. However, the adaptation of these regulations does not take place with the consideration of local specificities or scientific data (personal communication with workshop participants in Yakutsk, 2019). Pavlova reported that federal authorities exert an enormous influence on the setting of traditional fishing quotas as well as regulatory guidelines as it takes a long time to examine water bodies to establish quotas, and at times, it takes two years to increase the allowed volume of catch [102]. The allocated quotas are not enough for communities to meet dietary needs for a healthy life [98]. Moreover, state policy on fishing is poorly developed, inadequate, and ineffective with a huge lack of proper planning and projection [103].

There are also significant shortcomings in hunting regulations in Russia. Malysheva and Grenaderova pointed out three major issues of the hunting industry in Sakha Republic: (1) a poor state monitoring of wild animals and their habitat due to an inadequate hunting management plan, as well as its slow realization; (2) implementation gaps of Indigenous peoples’ priority rights for hunting; and (3) an inadequate legislation of compensation for damages caused to wildlife and their habitat by industrial companies [104]. Moreover, hunting is also restricted by quotas which cannot be compensated by the state due to a shortfall of funding [100]. Many hunters ceased hunting fur animals as the market price for their fur has dropped significantly [6]. The main reason for the price drop is the government’s misperception of the importance of sustainable development and consequently a lack of control over natural resource use [105]. Legal ban to utilize traps has also enormously decreased the hunting of animals for fur [106]. The state monitoring of hunting resources in the Republic of Sakha is carried out based on the winter migration route census, an aerial count of wild ungulates, hunters’ surveys, and state reports of hunters. State subsidies for the conservation of hunting resources and hunting monitoring have been reduced by more than twice since 2014 and thus, hunting has become complicated [105]. Moreover, it is increasingly more expensive to hunt, and the number of hunters is constantly decreasing [106,107].

A Federal Law on native languages adopted in 2018 allows school children in ethnic regions to choose an instruction and native language at school, either Russian or native. Many parents prefer their children to be taught in Russian as this is an “advantageous/prospective language” which will help in their future career and life. In this case, all classes are taught in Russian and native language classes become optional. In many ethnic regions, the number of native language classes has reduced enormously, and native language teachers retrain as a Russian language teacher [108]. This, in turn, affects native language proficiency and might eventually attrite its knowledge for good.

There are many other regulations and policies that undermine Indigenous peoples’ rights. One of the recent contested regulations is a law on a Federal Registry of Indigenous Persons which recognizes Russian citizens as Indigenous based on “the territory of traditional settlement of their ancestors”, who is “maintaining a traditional way of life, economy and trades”, and “considering themselves a distinct ethnic community” [109]. By applying multiple strict criteria, such as a place of residence, the registry ignores the legacies of colonialism and limits Indigenous rights as many Indigenous people do not live in places of their ancestors and moved to urban settlements for education or employment opportunities, since many Indigenous peoples do not practice traditional way of living on a full-time basis but work as a teacher, doctor, administrative worker, and so forth [110]. This law may deprive some Indigenous peoples of their right for traditional activities of hunting and fishing which they carry out from time to time, and thus, they may lose their ethnic identity [111].

2.4. Global Change: Implications for Indigenous Sustainability

The Indigenous peoples possess a holistic, comprehensive knowledge of their environment as they have been inhabiting the area for millennia and thus may adapt to changing climate and environment. However, when it comes to external factors such as institutional transformations, rapid climate change and industrial development dramatically impact Indigenous livelihoods, causing their adaptive capacity to be limited and sustainability to be compromised. Importantly, all three components of the Indigenous understandings of sustainability (land, native language, and Indigenous Knowledge system) are interconnected with the retention of one component helping to preserve the others [1]. These three elements are also interconnected by spirituality that underpins relationships, reciprocity, and respect embedded in the Indigenous visions of sustainability (Figure 1).

Land. Indigenous communities in Sakha Republic are significantly affected by climate change, transitions in governance systems and institutions, as well as economic development. Climate change-related emergencies and hazards damage infrastructure, worsen living conditions, and negatively impact the health of Indigenous peoples. Existing governance systems and institutions complicate pursuing traditional practices and maintaining native languages and knowledge, while industrial development forces out Indigenous peoples from their homelands and deteriorates traditional lands and waters.

All three global change drivers considered in this synthesis have been identified as factors related to forest fires. Kirillina et al. pointed out that rapid industrialization, predominantly in mining exploration, exploitation, and refining, large-scale agricultural industries, changes in forestry legislation, and increased deforestation are critical causes of forest fires in Sakha Republic [70]. Moreover, forest fires are believed to occur as a result of gradual warming since 2011 when several industrial projects were launched, such as a timber logging and processing facility in Amma and Guornay uluus, the expansion of cement production and gasification in Khaŋalas uluus, road construction in Üöhee Bülüü uluus, and the development and construction of a gas condensate field as well as a processing complex in Bülüü uluus [68]. Forest fire fighting measures in Sakha Republic were insufficient as authorities were slow in declaring emergency, asking for assistance from other Russian regions, and funding for fire extinguishing was not enough compared to that of western Russia (RUB 6.1 per ha in Sakha vs. RUB 200 per ha in western Russia) [51,71]. Many Sakha bloggers and entrepreneurs living abroad started their campaigns to help combat the recent massive forest fire in 2021. Some of them sent drones and other equipment, while others helped financially. The utilization of drones is advantageous as it does not require the use of airplanes, is easy to organize fire prevention measures, makes it possible to detect forest fires in advance, and prevents its further escalation; moreover, forest fire inspection can take place remotely with drones [74]. Indigenous peoples have been using fire as a land management tool for many centuries. Removing and burning forests from dead trees, branches, fallen needles, and leaves is deemed to be a fire-fighting measure [49]. However, the ban of such burnings combined with climatic changes caused severe forest fires over the last decades.

Permafrost thaw may be attributed not only to climate change, but also to other global change drivers. Varlamov in his study reported that the construction of the railway embankment between the towns of Aldan in the south and Allaraa Besteekh in central Sakha Republic caused a significant deepening of the active layer, an increase in the thaw depths, as well as a ground temperature rise [112]. This in turn may result in the ice-rich permafrost degradation in the cut slopes and ditches in the cut sections [108]. Similarly, the active layer had increased and thermal erosion had widely developed along the gas pipeline route in central Sakha Republic in the 1980s–1990s as a result of the construction work [113]. In the 1980s, permafrost thaw also occurred on the arable lands on forest clearings in central Sakha Republic that were eventually abandoned due to soil surface subsidence and devastation [114]. There is also a cultural and spiritual belief that the permafrost thaws because of mammoth tusk hunting on frozen grounds. The mammoth is believed to be the God of the underworld and taking its bone or tusk opens up the underworld and brings about troubles to traditional worldviews, traditional beliefs, and interconnections between younger and older generations [54]. Permafrost is an important sociocultural phenomenon for the Sakha people as alaas—a permafrost-based ecosystem—provides forage and fodder for horse and cattle subsistence in summer [115]. However, permafrost thaw alters alaas landscapes and they may no longer be suitable for traditional practices.

Authorities in Russia did not consider fish spawning season and climate change when developing fishing regulations, which led to discrepancies in spawning season and fishing seasonal ban [9]. Furthermore, fishing gear size and the legal ban of utilizing certain types of fishing nets (normally only up to 25 cm) as well as a mismatch in the distribution of fish quotas by weight (as the Arctic fish does not fit a small fishing gear and at times might weigh hundreds of kilograms) have caused local people to catch only small quantities of fish (conversation between Indigenous communities and the Ministry of Nature Conservation at the workshop in Yakutsk, Sakha, 2019). Participants of the workshop also complained about an extremely low price for fish trade to incoming fish companies and an abundance of commercial fishing ships on the sea that catch all the fish. Extractive industries destroy the native land upon which Indigenous peoples highly depend for sustaining traditional practices and spiritual and cultural well-being. For Western people, the land is perceived as a resource base, and for Indigenous peoples, it is everything.

Knowledge. Climatic and environmental changes impact Indigenous Knowledge since the weather is becoming unpredictable, and thus so is the knowledge as it is no longer possible to utilize it in the people’s livelihoods [54]. At the same time, government decisions made without considering Indigenous Knowledge threaten the very existence of the Indigenous peoples. In recent decades, floods have been affecting an increasing number of remote rural settlements. However, these floods could have been prevented or could have been less severe if the settlements had been constructed according to Indigenous Knowledge. Indigenous peoples in Siberia were initially practicing a nomadic lifestyle, moving around their homelands as an adaptive strategy to extreme ecosystems as well as climatic and environmental changes; however, the Soviet government forced the Indigenous peoples to settle down in villages to maximize production based on the Soviet industrial and economic model [116]. Moreover, smaller villages that were shut down and relocated to bigger ones brought about the loss of native language, cultural activities, and hunting grounds caused by unfamiliar living conditions in the new setting, insufficient living space, alcoholism, depression, and homesickness [117]. In addition, sedentarization led to a gradual loss of the skills, routes, and landmarks the nomads used to know previously when they lived on their land [97]. Soviet policies still continue to affect the sustainability of Indigenous communities. Thus, the Russification policy has deprived many Indigenous peoples of their native language and ethnic identity, which also affects many future generations; currently, many young people do not speak their mother tongue and possess fractured ethnic identity [118]. Previous floods in 1998 and 2001—when several villages were flooded in Lensky uluus in west Sakha Republic and then relocated to higher grounds—demonstrate that the Soviet settlement system along the rivers did not consider construction on a higher location [119]. Indigenous knowledge considers river break-ups in the construction of summer and winter settlements, whereby in spring, households move to summer settlements in alaas far from the river and move back to winter settlements when the summer is over. The de-indigenized settlement system is also dangerous because the settlements built along the river banks may collapse due to the coastal erosion as a result of climate change.

Language. In the Indigenous view of sustainability, the loss of one element leads to the deterioration of all. Native language is not only a means of communication, but also a storehouse of Indigenous Knowledge and a paramount instrument of knowledge transfer to future generations [2]. It is also a way to fully understand the land because frequent participation in the land-based practices is necessary to know and understand the language [38]. Native languages may erode as a result of educational regulations, shift from traditional practices to more profitable jobs, and climate change, as people will not be able to pursue traditional activities. Without native languages, it is hardly possible to maintain Indigenous Knowledge since many traditional, cultural, spiritual, and other phenomena are referred to in native languages. Traditional snow classification in Sakha, for example, showcases a close connection of the language, traditional practices, and knowledge system [120].

Spirituality. Spirituality may also be lost if other elements of Indigenous sustainability are diminished by global change drivers. When practicing water- and land-based activities, and in relation with their natural environment, Indigenous peoples express respect and reciprocity to Mother Earth. When moving with the reindeer, herders know the environmental conditions and timing of the migration start [121]. Hunters and fishers are familiar with the harvesting season, animal behavior, and other important features without which harvesting may become impossible. Therefore, they usually follow many traditional customs such as “nourishing” the spirit of forests and animals Baianai, Mother Earth, and Ebe (Grandmother—river and lake) by offering food to make them generous in gifting a prey. With the decline in the traditional practices due to climate change, economic development, and governmental regulations, all these sacred spiritual activities will diminish as well. Hence, it is important to pay careful attention to global change drivers to prevent such catastrophes.

3. Conclusions

The review and synthesis have demonstrated that global change drivers of climate change, governance system, and institutions, as well as economic development, compromise the sustainability of the Indigenous peoples in the Russian Arctic. The Indigenous understandings of sustainability differ from that of Western science and policy. A connection to land, native language, and the Indigenous Knowledge system constitute important elements of Indigenous sustainability and help Indigenous peoples to retain their economic, cultural, social, and spiritual well-being. Climate change-induced floods, forest fires, and permafrost thaw in Sakha Republic have caused infrastructural damage, economic costs, health issues, and other serious implications. Governmental regulations for fishing, hunting, native languages, and Indigenous persons registry negatively affected the sustainability of the Indigenous peoples by restricting traditional fishing and hunting activities, eroding native languages and potentially excluding Indigenous individuals from being as such. Industrial development in Sakha Republic has brought about traditional land grabbing, contamination of sacred water bodies, air pollution, a change in the migration routes of animals and fish, and many other negative consequences for the sustainability of the Indigenous peoples. Impacts of global change drivers may be less severe if authorities and industrial companies consider Indigenous Knowledge in their decision-making processes. Centuries-old Indigenous Knowledge has been utilized by the Indigenous peoples to adapt to harsh ecosystems as well as environmental and climatic changes to avoid natural disasters in the construction of their shelters and in practicing traditional activities. Indigenous knowledge is key in maintaining the sustainability of Indigenous peoples, coping with and adapting to new environmental and climatic conditions. In other words, Indigenous Knowledge is the main source of resilience and adaptation in Arctic Indigenous communities. Another necessary component for attaining sustainability on Indigenous terms is self-determination and self-governance. Only the Indigenous peoples who are recognized and empowered to make their own choices, use their knowledge systems, manage their resources, and set their own priorities may succeed in ensuring life and well-being for many generations to come.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S.K.; writing—original draft preparation, S.S.K.; writing—review and editing, A.N.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Science Foundation, research project “Measuring Urban Sustainability in Transition (MUST), grant number 2127366, and “Frozen Commons” grant number 2127345.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Semyon Drozdetsky for helping in creating maps. SK thanks his community for the constant inspiration and immense support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Biddle, N.; Swee, H. The Relationship between Wellbeing and Indigenous Land, Language and Culture in Australia. Aust. Geogr. 2012, 43, 215–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Throsby, D.; Petetskaya, E. Sustainability Concepts in Indigenous and Non-Indigenous Cultures. Int. J. Cult. Prop. 2016, 23, 119–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, N. Sustainable Development Considerations in the Arctic. In Environmental Security in the Arctic Ocean; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 37–58. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J.; Screen, J.A.; Furtado, J.C.; Barlow, M.; Whittleston, D.; Coumou, D.; Francis, J.; Dethloff, K.; Entekhabi, D.; Overland, J.; et al. Recent Arctic Amplification and Extreme Mid-Latitude Weather. Nat. Geosci. 2014, 7, 627–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rantanen, M.; Karpechko, A.Y.; Lipponen, A.; Ruosteenoja, K.; Vihma, T.; Laaksonen, A.; Nordling, K.; Hyvärinen, O. The Arctic Has Warmed Nearly Four Times Faster than the Globe since 1979. Commun. Earth Environ. 2022, 3, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ksenofontov, S.; Backhaus, N.; Schaepman-Strub, G. ‘There Are New Species’: Indigenous Knowledge of Biodiversity Change in Arctic Yakutia. Polar Geogr. 2019, 42, 34–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walther, G.R.; Roques, A.; Hulme, P.E.; Sykes, M.T.; Pyšek, P.; Kühn, I.; Zobel, M.; Bacher, S.; Botta-Dukát, Z.; Bugmann, H.; et al. Alien Species in a Warmer World: Risks and Opportunities. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2009, 24, 686–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ficke, A.; Myrick, C.; Hansen, L. Potential Impacts of Global Climate Change on Freshwater Fisheries. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 2007, 17, 581–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ksenofontov, S.; Backhaus, N.; Schaepman-Strub, G. ‘To Fish or Not to Fish?’: Fishing Communities of Arctic Yakutia in the Face of Environmental Change and Political Transformations. Polar Rec. 2017, 53, 289–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streletskiy, D.; Anisimov, O.; Vasiliev, A. Permafrost Degradation. In Snow and Ice-Related Hazards, Risks, and Disasters; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 303–344. ISBN 978-0-12-394849-6. [Google Scholar]

- Hjort, J.; Streletskiy, D.; Doré, G.; Wu, Q.; Bjella, K.; Luoto, M. Impacts of Permafrost Degradation on Infrastructure. Nat. Rev. Earth Env. 2022, 3, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irrgang, A.M.; Bendixen, M.; Farquharson, L.M.; Baranskaya, A.V.; Erikson, L.H.; Gibbs, A.E.; Ogorodov, S.A.; Overduin, P.P.; Lantuit, H.; Grigoriev, M.N.; et al. Drivers, Dynamics and Impacts of Changing Arctic Coasts. Nat. Rev. Earth Env. 2022, 3, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masrur, A.; Petrov, A.N.; DeGroote, J. Circumpolar Spatio-Temporal Patterns and Contributing Climatic Factors of Wildfire Activity in the Arctic Tundra from 2001–2015. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 014019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witze, A. The Arctic Is Burning like Never before—And That’s Bad News for Climate Change. Nature 2020, 585, 336–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brander, K. Impacts of Climate Change on Fisheries. J. Mar. Syst. 2010, 79, 389–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, J.D.; Pearce, T.; Canosa, I.V.; Harper, S. The Rapidly Changing Arctic and Its Societal Implications. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 2021, 12, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuklina, M.; Savvinova, A.; Filippova, V.; Krasnoshtanova, N.; Bogdanov, V.; Fedorova, A.; Kobylkin, D.; Trufanov, A.; Dashdorj, Z. Sustainability and Resilience of Indigenous Siberian Communities under the Impact of Transportation Infrastructure Transformation. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozawa, M.; Chyong, C.K.; Lin, K.C.; Reilly, T.; Humphrey, C.; Wood-Donnelly, C. The Power of Siberia: A Eurasian Pipeline Policy ‘Good’ for Whom. In In Search of Good Energy Policy; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019; ISBN 978-1-108-63943-9. [Google Scholar]

- Yakovleva, N. Oil Pipeline Construction in Eastern Siberia: Implications for Indigenous People. Geoforum 2011, 42, 708–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakovleva, N. Land, Oil and Indigenous People in the Russian North: A Case Study of the Oil Pipeline and Evenki in Aldan. In Natural Resource Extraction and Indigenous Livelihoods: Development Challenges in an Era of Globalization; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 147–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkes, F. Indigenous Knowledge and Resource Management Systems in the Canadian Subarctic. In Linking Social and Ecological Systems; Berkes, F., Folke, C., Colding, J., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998; pp. 98–127. [Google Scholar]

- Nuttall, M.; Berkes, F.; Forbes, B.; Kofinas, G.; Vlassova, T.; Wenzel, G. Hunting, Herding, Fishing, and Gathering: Indigenous Peoples and Renewable Resource Use in the Arctic. In Arctic Climate Impact Assessment; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005; pp. 649–690. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-Castillo, A.; Castellanos, E.J.; Galloway McLean, K. Indigenous Peoples, Local Communities and Climate Change Mitigation. Clim. Change 2017, 140, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, T. Are Arctic Ecosystems Vulnerable? Norsk Polarinstitut: Oslo, Norway, 1985; p. 27. [Google Scholar]

- Petrov, A.N.; BurnSilver, S.; Chapin III, F.S.; Fondahl, G.; Graybill, J.; Keil, K.; Nilsson, A.E.; Riedlsperger, R.; Schweitzer, P. Arctic Sustainability Research: Past, Present and Future; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; ISBN 978-0-367-21910-9. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, N. Chomsky: World Indigenous People Only Hope for Human Survival. Available online: https://www.telesurenglish.net/news/Chomsky-World-Indigenous-People-Only-Hope-for-Human-Survival-20160726-0040.html (accessed on 14 September 2023).

- Etchart, L. The Role of Indigenous Peoples in Combating Climate Change. Palgrave Commun. 2017, 3, 17085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petzold, J.; Andrews, N.; Ford, J.D.; Hedemann, C.; Postigo, J.C. Indigenous Knowledge on Climate Change Adaptation: A Global Evidence Map of Academic Literature. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 113007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWCED. Our Common Future. Available online: http://www.un-documents.net/wced-ocf.htm (accessed on 29 January 2018).

- Graf, W.D.; Dossa, S.; Dreimanis, J. Sustainable Ideologies and Interests: Beyond Brundtland. Third World Q. 1992, 13, 553–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crate, S.A. Investigating Local Definitions of Sustainability in the Arctic: Insights from Post-Soviet Sakha Villages. Arctic 2006, 59, 294–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sondergaard, J.S. When Words Matter: The Concept of “Sustainable Development” Derailed with Words like “Economy”, “Social” and “Environment.” In Arctic Yearbook; Northern Research Forum: Akureyri, Iceland, 2018; pp. 106–122. [Google Scholar]

- Degai, T.S.; Petrov, A.N. Rethinking Arctic Sustainable Development Agenda through Indigenizing UN Sustainable Development Goals. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2021, 28, 518–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graybill, J.; Petrov, A. Introduction to Arctic Sustainability: A Synthesis of Knowledge. In Arctic Sustainability, Key Methodologies and Knowledge Domains; Routledge: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2020; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Riedlsperger, R.; Goldhar, C.; Sheldon, T.; Bell, T. Meaning and Means of “Sustainability”: An Example from the Inuit Settlement Region of Nunatsiavut, Northern Labrador. In Northern Sustainabilities: Understanding and Addressing Change in the Circumpolar World; Fondahl, G., Wilson, G.N., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 317–336. ISBN 978-3-319-46150-2. [Google Scholar]

- Grey-Eagle, J. Sustainability from an Indigenous Perspective. Available online: www.wakantipi.org (accessed on 16 September 2023).

- Corntassel, J. Our Ways Will Continue On: Indigenous Approaches to Sustainability. In The Internationalization of Indigenous Rights: UNDRIP in the Canadian Context; Centre for International Governance Innovative: Waterloo, ON, Canada, 2014; pp. 65–71. [Google Scholar]

- Chiblow, S.; Meighan, P.J. Language Is Land, Land Is Language: The Importance of Indigenous Languages. Hum. Geogr. 2022, 15, 206–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, J.; Weaselboy, M. Indigenous Sustainable Relations: Considering Land in Language and Language in Land. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2020, 43, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maragia, B. The Indigenous Sustainability Paradox and the Quest for Sustainability in Post-Colonial Societies: Is Indigenous Knowledge All That Is Needed? Georget. Int. Environ. Law Rev. 2006, 18, 197–247. [Google Scholar]

- Nadya, M.; Elizabeth, T.; Huaman, S.; Mccarty, T.L.; Tom, M.N. Indigenous Knowledges as Vital Contributions to Sustainability. Int. Rev. Educ. 2019, 65, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidorova, E.J.; Ferguson, J. Feeding the Land: The Importance of Paying Attention to Sakha Language with Traditional Ecological Knowledge. Anthropol. Humanism 2023, 48, 6–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepanova, N.; Gritsenko, D.; Gavrilyeva, T.; Belokur, A. Sustainable Development in Sparsely Populated Territories: Case of the Russian Arctic and Far East. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stammler-Gossman, A. “Translating” Vulnerability at the Community Level: Case Study from the Russian North. In Community Adaptation and Vulnerability in Arctic regions; Hovelsrud, G.K., Smit, B., Eds.; Springer Science + Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 2010; pp. 131–162. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, J. Language Has a Spirit: Sakha (Yakut) Language Ideologies and Aesthetics of Sustenance. Arct. Anthropol. 2016, 53, 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamante, M.; Helmer, E.H.; Schill, S.; Belnap, J.; Brown, L.K.; Brugnoli, E.; Compton, J.E.; Coupe, R.H.; Hernández-Blanco, M.; Isbell, F.; et al. Chapter 4: Direct and Indirect Drivers of Change in Biodiversity and Nature’s Contributions to People. In IPBES (2018): The IPBES Regional Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services for the Americas; Secretariat of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services: Bonn, Germany, 2018; pp. 295–435. [Google Scholar]

- Millenium Ecosystem Assessment. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Synthesis; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gorokhov, A.N.; Fedorov, A.N. Current Trends in Climate Change in Yakutia. Geogr. Nat. Resour. 2018, 39, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czerniawska, J.; Chlachula, J. Climate-Change Induced Permafrost Degradation in Yakutia, East Siberia. Arctic 2020, 73, 509–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tananaev, N.I.; Efremova, V.A.; Gavrilyeva, T.N.; Parfenova, O.T. Assessment of the Community Vulnerability to Extreme Spring Floods: The Case of the Amga River, Central Yakutia, Siberia. Hydrol. Res. 2021, 52, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinokurova, L.; Solovyeva, V.; Filippova, V. When Ice Turns to Water: Forest Fires and Indigenous Settlements in the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia). Sustainability 2022, 14, 4759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parlato, N. A Critical Legal Geography of “Territories of Traditional Nature Use” (TTPP): Formation in the Sakha Republic (Yakutia), Russia. Master’s Thesis, University of Northern British Columbia, Prince George, BC, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jankiewicz, S.; Knyaginina, N.; Prina, F. Linguistic Rights and Education in the Republics of the Russian Federation: Towards Unity through Uniformity. Rev. Cent. East Eur. Law 2020, 45, 59–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilous, S. Gaps and Peculiarities of Russian Legislation in Reference to International Instruments on Indigenous Peoples’ Rights. Balt. Yearb. Int. Law Online 2022, 20, 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilyeva, O.V. Is the Extraction of Fossil Mammoth Bone a Form of Traditional Nature Management? Arct. North 2022, 46, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doloisio, N.; Vanderlinden, J.P. The Perception of Permafrost Thaw in the Sakha Republic (Russia): Narratives, Culture and Risk in the Face of Climate Change. Polar Sci. 2020, 26, 100589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPBES. The IPBES Regional Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services for the Americas; Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services: Bonn, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Eige. Final Report of the Project UDF-RUS-10-398 “Support of Democratic Initiatives of the Indigenous Numerically Small People of the North, Siberia and Far East”. Republic of Sakha (Yakutia); Centre for Ecological Awareness of the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) “Eige”: Yakutsk, Russia, 2013; p. 12. Available online: https://www.csipn.ru/projects/proekt-undef/24-projects/534-respublika-sakha-yakutiya-itogovyj-otchet (accessed on 20 September 2023).

- Egorov, E.G.; Ponomareva, G.A.; Fedorova, E.N. Geographical Location and Uniqueness of the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia). Reg. Econ. Teor. Prakt. 2009, 14, 16–21. [Google Scholar]

- Nogovitsyn, D.D.; Nikolaeva, N.A.; Sheina, Z.M. Ecological and Social Problems of the ESPO Pipeline System in Yakutia. In Proceedings of the ESCI, Irkutsk, Russia, 30 August–3 September 2010; pp. 5–13. [Google Scholar]

- Rosstat Vserossiyskaya Perepis Naseleniya (Russian Census). 2021. Available online: https://rosstat.gov.ru/vpn/2020/Tom1_Chislennost_i_razmeshchenie_naseleniya (accessed on 20 September 2023).

- Stammler-Gossmann, A. Who Is Indigenous? Construction of “Indigenousness” in Russian Legislation. Int. Community Law Rev. 2009, 11, 69–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alekseeva, E.K. Transformaciya v Tradicionnom Pitanii Tungusoyazychnyh Etnosov Yakutii. Gumanit. Vektor 2012, 2, 143–147. [Google Scholar]

- Lavrillier, A. Climate Change among Nomadic and Settled Tungus of Siberia: Continuity and Changes in Economic and Ritual Relationships with the Natural Environment. Polar Rec. 2013, 49, 260–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batugina, P.S.; Nogovitsyn, R.R. Mineral Resources in the Economic Development of Sakha Republic. Gorn. Inf.-Anal. Bull. 2009, 5, 50–56. [Google Scholar]

- Zhozhikov, A.; Alekseeva, E.; Nikitina, S.; Egorova, V. Vliyanie izmeneniya klimata na tradicionnyae vidy deyatelnosti korennykh jitelei Respubliki Sakha (Yakutia). Int. Sci. J. 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savvinov, G.N.; Makarov, V.S.; Velichenko, V.V. Ekosystemy Yakutskoi Arkitki: Sovremennye Vyzovy i Ugrozy. Probl. Reg. Ekol. 2023, 2, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- YSIA. Sakhamedia, 18 October 2019. Available online: https://ysia.ru/aleksandr-atlasov-pozdnie-dozhdi-mogut-negativno-skazatsya-na-zimovke-loshadej/ (accessed on 21 September 2023).

- Ignat’eva, V. Sakha Republic (Yakutia): Local Projections of Climate Changes and Adaptation Problems of Indigenous Peoples. In Global Warming and Human—Nature Dimension in Northern Eurasia; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 11–28. [Google Scholar]

- Kirillina, K.; Shvetsov, E.G.; Protopopova, V.V.; Thiesmeyer, L.; Yan, W. Consideration of Anthropogenic Factors in Boreal Forest Fire Regime Changes during Rapid Socio-Economic Development: Case Study of Forestry Districts with Increasing Burnt Area in the Sakha Republic, Russia. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 035009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narita, D.; Gavrilyeva, T.; Isaev, A. Impacts and Management of Forest Fires in the Republic of Sakha, Russia: A Local Perspective for a Global Problem. Polar Sci. 2021, 27, 100573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarskaya, L.E.; Kapitonova, T.A.; Struchkova, G.P. The Economic Damage from the Spring Flood in the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia). IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 459, 052003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebedev, A. Gotov li Verkhoyansky raion k zime? (Is Verkhoyansky district ready for winter?). Sakha Parliam. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Yakovlev, S.E.; Borisov, A.I. Use of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles for Automated Forest Fire Patrols in the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia). IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 839, 052022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenpeace, I. Record Breaking Fires in Siberia; Greenpeace International: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hayasaka, H. Rare and Extreme Wildland Fire in Sakha in 2021. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreev, D.V. Environmental Consequences of Fires. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 981, 032094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrova, A.N.; Efimova, Y.V.; Gromov, A.S. Synoptic Situation over Central Sakha in Summer 2021. In Proceedings of the Geography and Regional Studies in Sakha and Adjacent Territories of Siberia and Far East, Yakutsk, Russia, 25–26 March 2022; pp. 56–62. (In Russian). [Google Scholar]

- Lytkin, V.; Suleymanov, A.; Vinokurova, L.; Grigorev, S.; Golomareva, V.; Fedorov, S.; Kuzmina, A.; Syromyatnikov, I. Influence of Permafrost Landscapes Degradation on Livelihoods of Sakha Republic (Yakutia) Rural Communities. Land 2021, 10, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshikawa, K.; Osipov, D.; Serikov, S.; Permyakov, P.; Stanilovskaya, J.; Gagarin, L.; Kholodov, A. Traditional Ice Cellars (Lednik, Buluus) in Sakha: Characteristics, Temperature Monitoring and Distribution. Arktika. XXI Vek. Estestv. Nauk. 2016, 1, 15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Crate, S.A. Water, Water Everywhere: Perceptions of Chaotic Water Regimes in Northeastern Siberia, Russia. In Global Warming and Human-Nature Dimension in Northern Eurasia; Global Environmental Studies; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Tysiachniouk, M.S.; Petrov, A.N.; Gassiy, V. Towards Understanding Benefit Sharing between Extractive Industries and Indigenous/Local Communities in the Arctic. Resources 2020, 9, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dets, I.A. ESPO Oil Pipeline: Assessment of Impact on Social and Economic Development of Municipal Districts. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 381, 012018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RIA NOVOSTI. Oil Spill in Yakutia Did Not Affect Oil Transportation—Transneft. Available online: https://ria.ru/20100121/205607814.html (accessed on 20 September 2023).

- Lifshits, S.K.; Glyaznetsova, Y.S.; Erofeevskaya, L.A.; Chalaya, O.N.; Zueva, I.N.; Nestroeva, N.I. Ecological Problems of Oil and Gas Industry in the Arctic (Ekologicheskie Problemy Neftegazovykh Kompleksov Arkticheskogo Regiona). In Arkticheskiy Vektor: Strategiya Razvitiya; Academy of Science of Sakha Republic: Yakutsk, Russia, 2019; pp. 221–226. [Google Scholar]

- Gross, M. Arctic Shipping Threatens Wildlife. Curr. Biol. 2018, 28, R803–R805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]