Abstract

The participation of young people in agriculture is crucial in generating job opportunities and fostering the growth of agri-food systems in developing countries, particularly in Africa. This study aims to provide an in-depth review of existing studies on young people’s perceptions and factors influencing their participation in agribusiness. Additionally, the study aims to investigate the impact of the skill training intervention on youth engagement in agribusiness. The study also identifies and analyzes the constraints that hindered their engagement. The PRISMA guideline was followed to analyze 57 studies across Sub-Saharan Africa. Studies published from 2012 to 2022 were retrieved from various digital libraries, such as Google Scholar, Emerald Insight, Taylor & Francis Online, Wiley Online Library, and Science Direct. The review findings highlight that many young people in Africa view agriculture as a profitable industry and a means of subsistence. However, it was also observed that there are divergent opinions regarding agribusiness among young individuals. Factors such as access to finance, education, skills training, perceived social support, and prior experience in farming emerged as critical determinants influencing their decision to engage in agribusiness. Moreover, the study reveals that skill training programs positively impact youth participation in agribusiness. These interventions enhance their skills, increasing productivity, income, and employment opportunities. Nevertheless, access to finance and other essential resources, such as land and extension support, were identified as significant barriers to the involvement of young people in agribusiness. In order to promote the advancement of agri-food systems in Africa through youth participation, youth policies must prioritize access to various resources, including but not limited to capital, education, skills training, land, extension support, social support, mentoring, and private-sector involvement.

1. Introduction

Youth unemployment is one of the most critical development challenges in developing countries, particularly in Africa [1,2]. The unemployment crisis is associated with an increasing population, a stagnating economy, many unskilled workers, and the aging and deteriorating agricultural sector [3]. The growing prevalence of unemployment and poverty has forced the youth to engage in unlawful behavior or embark on risky journeys to developed countries in search of better opportunities [2,4]. The United Nations defines youth as individuals between 15 and 24 years old [5]. On the other hand, the African Youth Charter defined youth as those between the ages of 15 and 35 [5]. This specific demographic represents 60% to 70% of the total population of Africa [5,6,7]. Recent research by [6,8] has projected a substantial increase of approximately 35% in the African youth demographic by 2030. The projected demographic transition is expected to compound further the preexisting challenges of unemployment and poverty within the continent [2]. A report by [9] revealed that the unemployment rate among young people in the African region in 2022 was 12.7%, which exceeded the global average of 11.5%. It is also higher than the unemployment rate among adults in Africa, which is 10.9%.

Moreover, a higher proportion of young workers (63%) experienced poverty in Africa compared to those aged 25 and above, who accounted for 50% of the people living in poverty [9]. According to [10], most African youth not in education, employment, or training (NEET) effectively participate in subsistence labor on their family agricultural enterprises. Similarly, young people in urban areas classified as NEET often engage in short-term informal work, education (including dropping out of formal schooling), and training through unpaid apprenticeships with family members [11].

The agricultural sector in Africa remains a viable source of employment opportunities for the considerable youth population [6]. In particular, the agribusiness sector has excellent promise as it integrates farming with other industries and services across the value chain. The studies above [8,9,10,11,12] highlight the potential of this interdependent system to stimulate economic expansion and employment opportunities at various stages of the agricultural value chain, which encompasses agriculture, processing, wholesale, and retail. The youth population in Africa is positioned to assume a crucial and influential position in the development and transformation of the agricultural sector. According to [11], participating in agri-food-related endeavors encompasses various aspects such as entrepreneurial initiatives, value chain operations, policy development, and advocacy efforts. The author emphasized the significance of involving young people in agriculture significantly and consistently, as they can contribute to the sector’s advancement and progress.

Recently, there has been a surge in efforts to engage young people in the agricultural business sector in Africa. The implementation of several initiatives serves as evidence for this claim. These initiatives include the adoption of the African Youth Charter (AYC) by the African Union in 2006, the declaration of the Youth Decade Plan of Action (2009 to 2018), and the establishment of the Youth Desk within the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD). These developments demonstrate a growing political determination to address the issue. Additionally, initiatives such as ENABLE (Empowering New Agribusiness-Led Employment for Young People in African Agriculture) receive support from the African Development Bank and the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA). These initiatives are designed to encourage recent university graduates to pursue professional endeavors within the agribusiness sector. The Comprehensive African Agriculture Development Program (CAADP) is a significant initiative, as highlighted in [6]. Previous efforts represent a constructive step toward tackling the issue of unemployment among young people in Africa while simultaneously fostering the advancement of the agricultural industry and its economic prosperity. Efforts have been made within these programs to help participants conduct successful agribusinesses by teaching them how to create effective business plans and apply for loans. Several African governments are implementing it: Cameroon, Cote d’Ivoire, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ghana, Madagascar, Nigeria, and Sudan [6]. Furthermore, projects such as agribusiness parks in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Morocco’s IAA Program, Senegal’s Jeunes Agriculteurs, and Zambia’s UniBRAIN initiative have all contributed to better competitiveness, higher agricultural productivity, higher value crops, and better connections between young farmers and new markets. Other examples include the Next Generation Youth in Cocoa Programme (MASO) in Ghana [13], the N-power Agro Program [14], and the Fadama Graduate Unemployed Youths and Women Support (GUYS) program in Nigeria [15].

Despite the considerable progress in promoting youth engagement in agriculture via skills training on the continent, the intended outcomes have yet to be fully realized [16]. The task of engaging youths in agriculture and its related value chains has proven to be challenging [17]. Reports from several academic studies have shown that few young people are engaged in agriculture [18,19,20]. The findings from these studies indicated that young people associated the agricultural sector with low-skilled labor, low social status, and tedious work, resulting in many people moving to urban areas for better job opportunities. Therefore, to make agribusiness sustainable and attractive to youth, effort is needed to address climate-induced events that continue to impact agricultural productivity and food insecurity negatively [21]. Climate change is a significant threat to agriculture, affecting crop productivity and livestock through fluctuations in rainfall patterns, prolonged droughts, heatwaves, increased pests and diseases, water shortages, and consequent food scarcity [22]. A study in Cameroon found that a temperature rise of 1.5°C reduces income by approximately 4.3%, increasing to 7.3% at 2.5 °C [23]. Climate change also expedites land degradation, impacting livelihoods and exacerbating poverty [23,24]. Therefore, there is a need for substantial investments in infrastructure, such as sustainable irrigation expansion, power generation and grid development, and road construction [18].

Multiple studies have been conducted on the perspective of young people on agriculture and their levels of interest and participation [6,20,25,26,27,28,29]. Numerous impediments have been identified as persistent barriers that impede the active involvement of young people in this field. These obstacles include education, skills, land, financial assistance, access to the market, and institutions. However, few studies comprehensively examine the effects of interventions on the involvement of young individuals in agribusiness. This research argues that the influence of training programs will surely encourage more children to participate in agriculture, even if conventional indicators are crucial to youth participation in agriculture. Against this backdrop, we set out to review and synthesize previous studies on youth in African agribusiness from 2012 to 2022. The review seeks to provide answers to the following questions:

- What are the attitudes and perceptions of youth in agribusiness in Africa?

- What are the main factors influencing youth engagement in agribusiness?

- How effective are the training interventions on youth in agribusiness?

- What are the constraints young people face in agribusiness in Africa?

This measure is expected to facilitate the formulation of effective policies that foster the participation of young people in agribusiness.

This paper is outlined as follows. The next section presents the theoretical background. Section 2 presents the review methodology, which explains how relevant studies were identified and analyzed. Then, the results are presented in Section 3, focusing on the perceptions, interests, and factors influencing youth participation in agriculture and the impact of training interventions and challenges faced by those involved in agriculture. Finally, the paper concludes with recommendations and suggestions for future research.

2. Theoretical Background

Social cognitive career theory (SCCT) is one of several theories offered to explain career development and decision-making [30]. The theory posited that people drive influential power through three fundamental social cognitive mechanisms crucial for career development: self-efficacy, outcome expectations, and personal goals [30]. Self-efficacy is related to the belief in one’s ability to learn or perform actions at the desired level [31]. It has a significant impact on individuals’ vocational interests and their aspirations for their future careers. Outcome expectations are linked to individuals’ beliefs about the results of engaging in activities. Goals reflect an individual’s aspirations to engage in an activity or attain a specific level of performance [31]. According to SCCT, numerous factors can help or hinder an individual’s career choices. These factors include economic and emotional resources, career role models, and the influence of gender stereotypes [30]. Strong social and family support shapes individuals’ understanding of their career aspirations and influences their decision-making behavior. Individuals with enough guidance from role models are more likely to develop a positive mindset when faced with challenges. This, in turn, enhances their belief in their abilities [30].

Young people’s engagement in agribusiness in SSA may be better understood through the lens of SCCT [30]. According to SCCT, a decision to engage in career choice, particularly in agribusiness, is influenced by a combination of internal and external factors. As proposed by SCCT, individuals’ ideas, attitudes, and behaviors are shaped by what they see, hear, and do in their surroundings. Young people’s views on agriculture can be affected by characteristics such as their gender, level of education, and socioeconomic factors. For example, young people who view agriculture as a lucrative and rewarding career are more likely to work in agribusiness [25,32]. On the other hand, those who perceived the sector as not profitable are less likely to take it as a career choice [16,29]. Young people with strong social networks like family and friends are more likely to engage in agribusiness. Moreover, engagement in training intervention is perceived to positively influence youth to participate in agribusiness. The intervention will equip them with skills making them more productive and efficient. However, young people with limited access to resources such as finance and land are less likely to pursue agribusiness [25,32]. Many researchers have utilized the SCCT theory in their studies to explore the career behaviors of young people, highlighting its significance in this area of investigation. For example, [33] applied the model to determine the career decision-making intention of agriculture students at Kermanshah University. Likewise, [34], in their review on cooking and food skill intervention, used the SCT and indicated that SCCT is a practical framework for explaining intervention outcomes. Based on these proceedings, this systematic review leverages support from the SCT model to review publications on young people’s perceptions, interest, and involvement in agribusiness in Africa.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Research Design

We conducted a comprehensive analysis of scholarly literature by performing a systematic literature review (SLR) using peer-reviewed articles from four databases: Google Scholar, Emerald Insight, Taylor & Francis Online, Wiley Online Library, and Science Direct, published from 2012 to 2022. The Scopus database was chosen as it is often used in various reviews, particularly in the entrepreneurship literature, and is considered the most significant abstract and citation database of peer-reviewed literature, with approximately 70 million records and over 21,600 peer-reviewed journals from over 4000 international publishers in different scientific areas [35,36].

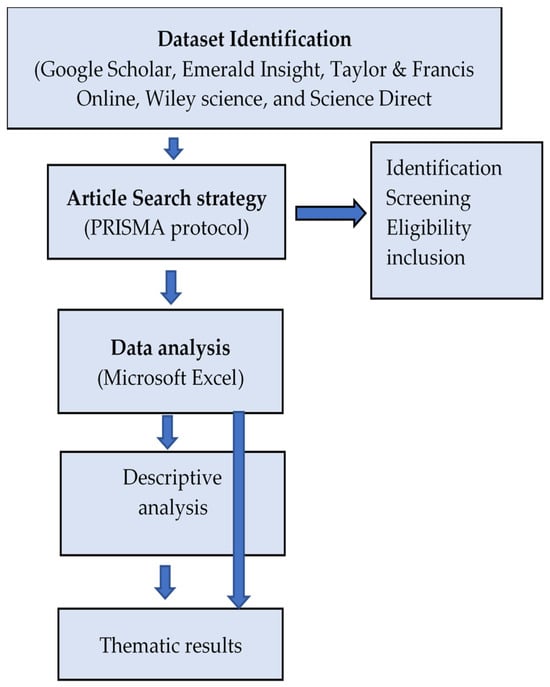

We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) protocol for conducting a systematic review [37]. PRISMA is an iterative procedure comprising a four-phase flow diagram and a 27-item checklist. It is a widely recognized framework that facilitates the conduct and reporting of systematic reviews [37]. It offers a well-organized method to guarantee the review process’s openness, reliability, and quality [37]. The PRISMA statement allowed for a search for phrases associated with youth participation in agriculture in Africa. Hence, the review methodology is structured around three distinct phases: dataset identification, article search technique, and data processing, as seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the research methodology [38].

3.2. Dataset Identification

The databases mentioned above were selected for the dataset identification phase due to their comprehensive collection of indexed and peer-reviewed academic journals. These databases are widely recognized and utilized by scholars globally for systematic literature reviews. The desk review commenced by searching for articles on young participation in agriculture, determinants of involvement in agribusiness, and the impact of training and challenges in Sub-Saharan Africa. We began our search by using the most prevalent keywords in the relevant literature: agriculture, participation, youth, training, and challenges. Literature search terms/keywords used included ‘agriculture’ with the synonym ‘farming’. The term “participation” or “involvement” was the second most searched word, followed by “youth”, which included related phrases such as “young people”, “adolescence”, and “young adulthood”. These keywords were further linked with others using Boolean operations such as ‘youth AND agriculture’, ‘young men AND agriculture’, ‘young women AND agriculture participation’, ‘agribusiness’, ‘engagement’, ‘participation’, ‘involvement’, ‘perception’, ‘youth AND intervention’, ‘impact on employment’, ‘Impact on productivity’, ‘youth AND agriculture challenges’, and ‘rural enterprises’, ‘young men AND agriculture participation’.

3.3. Article Search Strategy

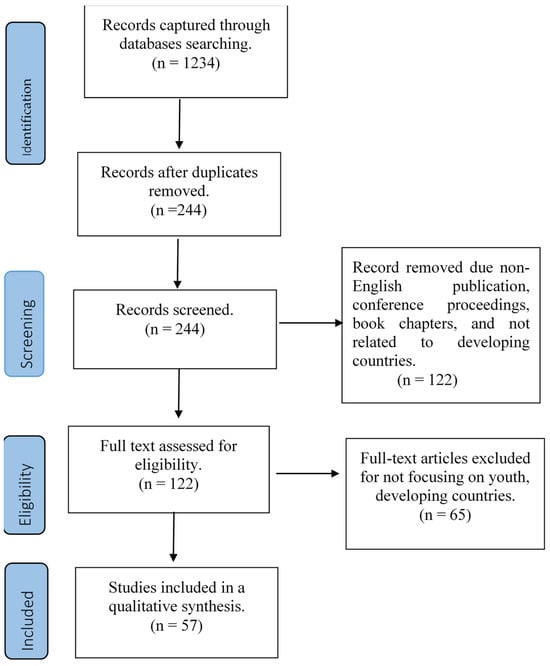

Review findings were reported using the PRISMA flowchart (Figure 2). The initial literature search found 1234 articles that were screened for eligibility. During the title screening process, 990 publications were removed due to duplicate content, and 244 abstracts were further reviewed to determine eligibility. Out of the 122 articles that were deemed relevant, full-text versions were obtained for subsequent evaluation. However, 122 research were excluded since they had no bearing on the topic under investigation. Of the initial 122 research articles, 65 were excluded during the full-article screening phase. A total of 57 articles met the selection criteria and were included in the study. A data extraction template (Table A1) was used to document all of the information of interest in the 57 studies.

Figure 2.

Flowchart representing the systematic review procedure adopted from [34].

3.4. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The systematic review relied on well-defined analytical criteria, as shown in Table 1, and applies explicit exclusion and inclusion criteria to maintain focus on research questions. First, the desk review was based on a publication on youth in agribusiness in Africa between 2012 and 2022. The period coincided with the African Youth Decade Plan of Action [16]. Second, only articles originally written in English were considered for the search. The focus on English publications was based on the understanding that the transmission of scientific information mainly occurs in English and is a commonly used criterion in numerous literature reviews [39]. Third, the review focuses on research conducted in African countries. Studies from Asia and the developed world were excluded. The logic was to find out the trend of studies on youth engagement in agriculture across Africa. Fourth, the scope of the review was limited to “peer review research articles” and “Review” papers since these types of publications are considered to provide the most current and influential information in the field [15,39]. Additionally, some “grey” literature sources, including government publications, conference proceedings, and book chapters, were included to provide supplemental information for the systematic review. Finally, the selected articles must focus on young people in agriculture.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for the review.

3.5. Quality Assessment Analysis

After determining publications that meet the inclusion criteria, we assessed their quality using a PRISMA checklist developed by [40] and modified by [41]. The PRISMA guideline serves several benefits in the review process. Firstly, it guides the explicit formulation of research questions as required by the PRISMA checklist. Secondly, it promotes organized and transparent reporting, as outlined in the PRISMA flowchart. Thirdly, the PRISMA checklist establishes precise criteria for including and excluding relevant information. Each article in the evaluation was assessed based on the items included in the PRISMA 2020 and abstract checklists. To enhance the quality of abstracts, it is necessary to have exclusion criteria, risk of bias evaluation techniques, statistical approaches, and limits of evidence.

3.6. Risk of Bias Assessment

Two reviewers, MB and AA, extracted the data separately and later collaborated to resolve any discrepancies in a situation where there was disagreement. The studies were analyzed after a thorough quality assessment to determine the presence of bias, including the potential for distorted outcomes, significant confounding factors, and the probability of chance occurrences [40,41]. The review value was assessed by evaluating three questions: “Do the results exhibit any form of biased inclination?” Are there significant confounding variables or other factors that can introduce bias or distortion into the findings? Additionally, is there a reasonable probability that the observed results are due to random chance? If the responses to these three summary questions were negative, the research findings were likely characterized by a low likelihood of bias. After the quality and risk of bias evaluations, it was evident that all research papers exhibited methodological rigor and demonstrated minimal vulnerability to bias.

3.7. Data Analysis

The data was organized, categorized, and examined in this stage using Microsoft Excel. A Microsoft Excel spreadsheet was populated with all appropriate information regarding the 57 selected papers, including titles, abstracts, keywords, authors’ names and affiliations, journals’ names, and years of publication. The emphasis was on articles that directly addressed the research questions. The qualitative content analysis methodology was used to determine the overarching themes associated with the participation of young people in agriculture in Africa, the impact of the intervention program on their participation, and the challenges they faced in running agriculture enterprise.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Characteristics of the Included Studies

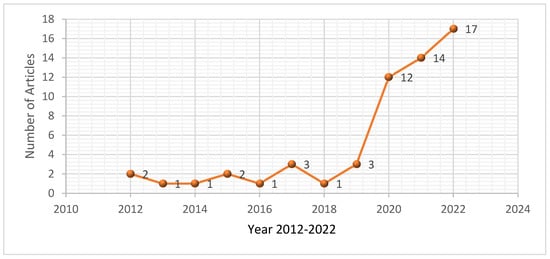

Figure 3 illustrates that 57 articles were considered relevant and included in the research review. These articles were selected based on the inclusion criteria for publications between 2012 and 2022. The findings suggest a significant rise in the literature on youth in agribusiness in Africa. The increasing scholarly interest in this subject matter is evident from the upward trend, highlighting its growing significance. Most publications were issued between 2020 and 2022, with the majority published in 2022. The proliferation of scholarly articles concerning youth engagement in promoting agribusiness development in Africa might manifest the African governments’ determination to attain the objectives outlined in Sustainable Development Goals 1, 2, and 8, which focus on reducing poverty, eradicating hunger, employment generation, and decent work.

Figure 3.

Total number of articles (2012–2022).

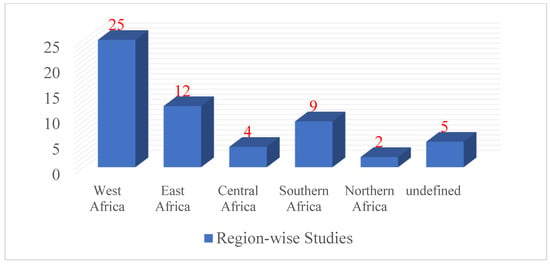

Figure 4 shows the geographical distribution of 57 research articles on youth in agribusiness. The findings shows that West Africa had the highest number of studies, with 25 articles, accounting for 44% of the research. East Africa followed with 12 articles, representing 21% of the total. Southern Africa had nine articles, which is 16% of the total. Central and North Africa had the lowest number of studies, with only four articles combined. Interestingly, these regions had the lowest number of studies on youth in agribusiness. It should be noted that five articles were not defined, indicating that they covered the entire African continent without any specific regional focus. Although various databases have addressed this topic, the findings presented in this study provide valuable insights into the regional distribution of studies on youth in agribusiness.

Figure 4.

Regional-wise studies.

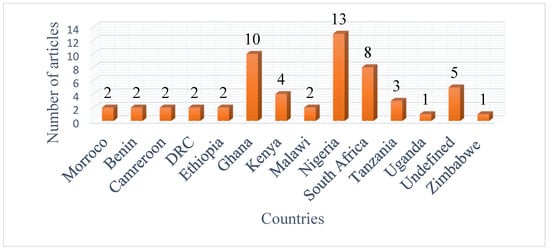

The distribution of the country-wise studies is presented in Figure 5. The findings showed that most studies (13) were conducted in Nigeria, which can be attributed to the country’s large population and significant agricultural sector. Ten of the total sample studies were from Ghana. Around eight articles were from South Africa. These findings suggest that Nigeria, Ghana, and South Africa were the countries with many studies on youth participation in agriculture in sub-Saharan Africa. Four articles were published in Kenya and three in Tanzania. Only one study was found in Uganda and Zimbabwe, while [6,7,42,43,44] studies were not specific to any country. This could be attributed to the nature of the survey because three of these studies were review articles, and one was a research article. In addition, it was observed that there are limited studies in other African countries. Therefore, future researchers need to explore these areas.

Figure 5.

Total articles per country (2012–2022).

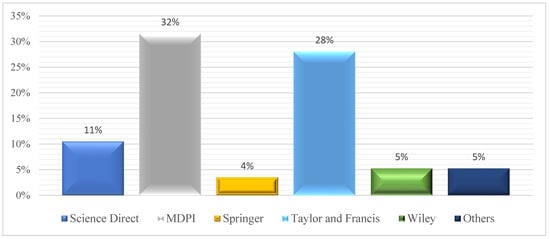

Figure 6 presents the results of the research articles per database. According to the findings, MDPI had the most published research papers (18), followed by Taylor and Francis with 16, Emerald Insight with 9, and ScienceDirect with 6. Surprisingly, Springer and Wiley, well-known and respected sources, had only two and three articles on young agricultural participation. This could suggest that young agricultural involvement is not an area highly researched for these databases or that researchers in this field need to publish their work through these channels. Three articles came from other sources, which could have been open access or smaller, more niche databases. Although these sources may not be as well known as more extensive databases, they can still provide valuable insights and information.

Figure 6.

Research articles per database.

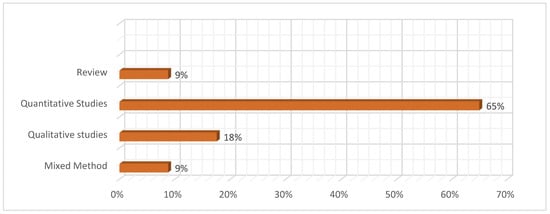

Figure 7 presents an overview of the research methodologies used in the 57 included articles, offering insight into the methods and techniques employed by researchers in this field. The results revealed that the majority (65%, 37) of the research articles were quantitative research. Of the 57 studies, ten (18%) applied qualitative research techniques. Qualitative research typically involves collecting non-numerical data through interviews, focus groups, and observation and then analyzing those data to find themes and patterns. The results also show that five of the included articles were review articles that synthesize and summarize the findings of multiple studies on a particular topic. The review and mixed method were the least explored, with only five articles each. This suggested that there is a need for more studies in this direction. Mixed-methods research can provide a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of a particular phenomenon, allowing researchers to collect numerical and non-numerical data and analyze it in several ways.

Figure 7.

Research methodologies.

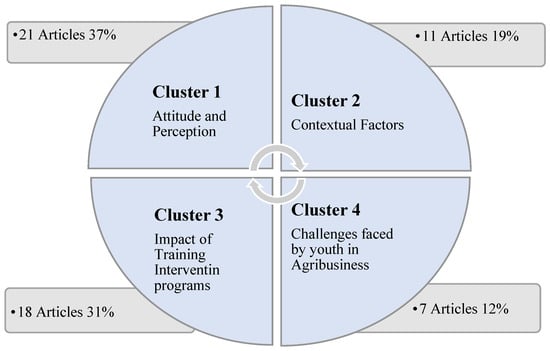

4.2. Themes Identified from the Analysis

Following Social Cognitive Theory, we have identified 57 articles and categorized them into four clusters based on their similarities in content. Of the 57 studies reviewed, 21 articles (37%) concentrated on the perception and interest of young people in pursuing agribusiness as a career (Attitude and Perception—cluster 1). A total of 11 studies, representing 19%, focused on the factors that affect youth engagement in agribusiness (Contextual Factors—cluster 2). Around 31% (equivalent to 18 publications) focused on analyzing the impact of intervention programs on the involvement of young people in agriculture (Impact of Training Intervention—cluster 3). Seven articles (12%) presented findings on the challenges that hinder young people from engagement in agribusiness (Challenges faced by youth in agribusiness—cluster 4). The identified themes were analyzed using content analysis. This methodology proves valuable in examining patterns, content understanding, and meaning interpretation [45,46]. To reduce biases, two authors independently read the 57 articles used in this study and classified these studies into four major clusters, as illustrated in Figure 8 and Table A1 (refer to Appendix A).

Figure 8.

Research topics in themes.

4.2.1. Attitude and Perception Youth in Agribusiness

Among the 21 papers examined, 11 articles [7,19,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55] investigated young individuals’ intentions and career choices in agribusiness. Of the thirteen publications analyzed, five papers [7,50,51,52,56,57] focused on young people’s desire to engage in agricultural activities. In addition, two scholarly publications evaluated students’ inclination to pursue a profession in agriculture [48,52]. Four studies examined the level of interest among young people in engaging in the agricultural value chain [47,49,55,58]. Two studies [47,58] evaluated the inclination of young people toward engaging in the whole agricultural value chain. Eight studies [13,16,25,26,28,32,59,60] explored young individuals’ perceptions of agriculture. Of these eight articles, four papers [25,32,54,61] reported that young people had a favorable view of agriculture. According to these papers, young people perceived agriculture as a lucrative sector capable of offering job opportunities and serving as a means of sustenance. The other four articles [16,29,59,62] concluded that young people associate agriculture as a rural activity for poor people. They perceived the sector as laborious, tedious, and not lucrative.

4.2.2. Contextual Factors

- a.

- Access to finance

Five out of the thirteen studies [58,62,63,64,65] explored the role of access to finance as a significant determinant affecting the involvement of young people in agribusiness activities. The availability of finance is a major driver stimulating youth to engage in agribusiness, but the challenge of accessing funds to initiate agribusiness in most African countries remains a concern [58,66]. A study by Chandio et al. [35] concluded that access to formal agricultural credit positively and significantly affected sugarcane yield in Pakistan. Tadesse [36] argued that access to financial services enhances securing other resources such as land, labor, and farm tools. However, the lack of access to financial resources has resulted in a decreased inclination among young individuals in Ethiopia to engage in agricultural activities [64]. Furthermore, scholarly research from the Democratic Republic of the Congo [54] highlighted that the limited availability of financial resources was a significant obstacle to young people’s participation in agriculture.

- b.

- Access to land

Four studies [49,61,62,65] looked at the issue of access to land as an essential determinant of young people’s involvement in agribusiness. The land is an important farm input in agribusiness enterprises. It is a crucial determinant of young people’s participation in the agriculture sector. However, reference [52] reported that Malawi’s high land cost was a significant impediment discouraging young people from showing interest in engaging in agricultural activities and pursuing opportunities in the agribusiness sector. This phenomenon was also observed in Ghana, as documented by [67], who highlighted that inflated prices and competition from residential developers constitute significant obstacles that hinder the ability of young individuals to acquire agricultural land. Moreover, it is worth noting that in sub-Saharan Africa, the practice of inheriting lands is characterized by tiny land parcels due to the ongoing partition of property among various family members [65].

- c.

- Access to a training program

Eight papers [19,26,49,50,52,55,68,69] examined the effects of access to a training program on the engagement of young people in agribusiness. Bello et al. [69] found that skills development, engagement in non-agricultural pursuits, affiliation with youth organizations, availability of financial services, and access to additional resources significantly influenced the level of involvement of young people in the Youth in Agriculture Program. According to Baloyi et al. [47], access to agricultural training information and communication technology significantly impacted youth engagement in agribusiness.

- d.

- Access to technology

Five studies [19,25,70,71,72] focused on the role of information in influencing young people towards agribusiness. Some studies indicated that facilitating youth access to technology may increase engagement and productivity in the agriculture sector [71,72]. The advancement of technology has significantly reduced the accessibility of market price data, weather predictions, and suggested farming techniques for young individuals [20]. Jolex and Tufa [71] reported that young agribusiness owners had a notable improvement in productivity and profitability via the use of information and communication technologies (ICTs) in their agricultural operations. Therefore, using technology may effectively foster the growth of young entrepreneurs in the agricultural sector by facilitating information sharing and fostering relationships among aspiring business owners. More importantly, the use of Internet channels to promote and sell commodities can enhance the economic prospects of young people and facilitate the expansion of agricultural business.

- e.

- Socioeconomic factors

The role of socioeconomic characteristics, including age, gender, education, and income, on the interest of young individuals in engaging in agribusiness was examined in six studies [2,55,56,64,65]. Most of the studies have emphasized the importance of education in cultivating positive perceptions and fostering interest in agriculture among youth. Mdege et al. [56] reported that implementing agricultural education has increased the involvement of young people in agribusiness across many countries. The authors observed a notable disposition among educated rural youth towards agriculture and agribusiness [56]. However, one study [54] found that those with a greater level of education have a negative perception of the field of agriculture. Hence, agricultural institutions may prioritize practical training to provide students with the necessary competencies to excel in agriculture [7].

The influence of gender on young engagement in agriculture has appeared in several studies [2,48,56,65]. These studies have shown that gender norms, preconceptions, and discriminations substantially impact the extent of young male and female engagement in the agricultural sector. The presence of preexisting gender preconceptions and prejudices often leads to limited opportunities for young women in agriculture, leading to adverse effects on their financial earnings, job security, and overall socioeconomic status. In contrast, it is observed that young boys tend to participate in agricultural activities to a greater extent, irrespective of their personal preferences, due to cultural norms and expectations.

- f.

- Influences of parents, family members, and friends on youth participation in agriculture

Five studies [7,50,53,73,74] looked at the influence of social factors in promoting young adults’ involvement in agribusiness. The findings of the research suggest that social pressure from family and friends had a significant effect on the career choices of young people. Anyidoho et al. [53] indicated that involvement in social networking platforms, such as participation in cooperatives, had a significant positive influence on the aspirations of young people to engage in agriculture. Hence, promoting social networks and community development is vital to foster young peoples’ participation in the agricultural sector. The results indicated that fostering social ties, community development, and addressing challenges associated with societal norms and views are crucial to fostering youth agricultural engagement. Enhancing access to financial and technical resources and promoting agricultural expertise and knowledge may increase engagement in agripreneurship. By implementing these strategies, policymakers and stakeholders may encourage youth engagement and facilitate the advancement of sustainable farm expansion.

4.2.3. Intervention and Its Impact on Youth Participation in Agribusiness

- a.

- Productivity and Income

Out of the 18 studies centered on intervention programs, four studies [42,75,76,77] provided results about the influence of the training program on productivity and revenue. For example, one study [77] revealed that the implementation of contract farming resulted in a notable rise of 17%, 34%, and 37.5% in French bean yields and earnings for young producers, respectively. These research findings indicated that skill training programs substantially impact agricultural productivity, resulting in a subsequent rise in income. Research shows that the active engagement of young people in agricultural activities can significantly enhance rice output and overall income [42].

Consequently, governments need to prioritize establishing skill training initiatives within the agricultural sector, aiming to enhance production levels within the industry. Furthermore, it is imperative to make concerted endeavors to foster greater engagement of the younger generation in agricultural pursuits, given their shown potential to enhance agricultural production. Policies and acts of this kind can substantially impact a nation’s general economic growth and development, with a particular emphasis on rural areas that heavily rely on agriculture as their primary source of revenue.

- b.

- Employment outcome and poverty reduction

Five papers [14,69,70,75,78] focused on the effect of training intervention programs on youth employment and poverty reduction. One of the studies conducted by [70] revealed that the engagement of young people in agricultural initiatives had a substantial impact on poverty alleviation, resulting in a noteworthy 28% decrease in the likelihood of experiencing poverty in the future. Based on the findings of [6,14], implementing skill training interventions virtually facilitates acquiring gainful work opportunities within the agricultural value chain among young people. Consequently, this has resulted in a notable decrease in poverty levels. Hence, policymakers should give precedence to implementing initiatives centered on cultivating skills and capabilities among young people, facilitating their active engagement in the agricultural domain.

- c.

- Technical Skills

Seven papers [66,71,72,77,79,80,81] concentrated on the efficacy of the training intervention on the technical abilities of young individuals and fostering their engagement and enthusiasm towards agriculture. Two studies conducted by researchers, [71,72], examined the impact of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) on youth involvement in the agricultural sector. The authors determined that using ICT was crucial in improving the profitability of young farmers [71]. Additionally, it enables young farmers to access market information and social networks conveniently [72]. Based on the results above, it is essential to disseminate emerging livelihood skills programs to enhance young people’s employability and equip them with the necessary competencies for the labor market.

- d.

- Awareness creation

An investigation by [79] assessed the efficacy of the “Cocoana Chocolate” musical campaign, which sought to engage more young people in agriculture to generate revenue. The study results revealed that most participants demonstrated knowledge of the agricultural subject matter in the album, reported having listened to it on six separate occasions, and could recall its content. However, 54.9 percent disagreed with their capacity to mobilize resources and expressed a need for further financial support. The study’s findings suggest that the interventions adopted by African governments and development partners have had favorable outcomes in several domains. Implementing interventions resulted in a shift in the view of agriculture among young people, thereby repositioning it as a viable and competitive career option.

Furthermore, there has been an enhancement in their accessibility to productive resources and proficiency in business administration, along with a notable rise in the utilization of information and communication technologies (ICT) in agriculture [26,34,69]. Furthermore, the initiatives have not only facilitated enhanced market access and business networks, but they have also effectively pushed the youth towards engaging in agribusiness activities. Additionally, these interventions have successfully fostered the establishment of young firms and generated job opportunities in agricultural value chains [15,76]. The findings of this study provide evidence of the effectiveness of interventions in addressing the challenges encountered by African adolescents in the agriculture industry.

4.2.4. Challenges Faced by Youth Involved in the Value Chain of Agribusiness

Challenges that impact young people’s involvement in agriculture were examined and studied in seven studies [43,65,67,82,83,84]. Most of the concerns documented in the scholarly literature arise from a desire for access to or authority over resources related to production, finance, knowledge and information, extension services, innovation, or technology.

- a.

- Financial challenges

Financial challenges are one of the critical barriers limiting youth participation in agriculture. A study by [58] demonstrated that inadequate access to information on agricultural finance, the uncertainty of credit default, and the unavailability of Microfinance Institutions prevented tomato growers from accessing agricultural credit services. Similar findings were reported by [66], who highlighted that adequate access to credit discouraged youth from engaging in agriculture. According to research conducted in Nigeria [15], the primary obstacle hindering youth involvement in agriculture was the need for more access to financial resources. Many young individuals associate their limited engagement in agribusiness with high interest rates, unfavorable repayment arrangements, and insufficient collateral to secure loans [85]. Hence, policymakers and other relevant stakeholders must develop innovative financing structures and products specifically designed to meet the distinctive needs of young farmers. To facilitate the optimal development of young people in agriculture, the programs above must prioritize cultivating financial literacy, establishing market links, and implementing risk management strategies.

- b.

- Social barriers

This review highlighted that social pressure from close relatives, friends, and peers negatively affects young people’s desire to participate in agribusiness. Most of the previous studies demonstrated that young people are discouraged due to pressure emanating from family members and friends, and gender may have an impact on the level of engagement of young individuals in the field of agriculture. In several societal contexts, women encounter discriminatory barriers while attempting to obtain land, loans, and other resources, impeding their engagement in agricultural activities.

- c.

- Inadequate training

Inadequate training in agribusiness appeared to be one of the critical challenges affecting young people’s engagement in the sector. A study conducted by [76] revealed apart from credit constrains, the impediments to the economic engagement of young people include insufficiencies in formal schooling, dearth of career guidance, lack of marketable skills, absence of good role models, inadequate access to resources, and absence of policies that foster their involvement.

- d.

- Inadequate support services

As per the proponents of the sustainable livelihood plan, the primary obstacles to economic development were identified as limitations in physical capital, including service delivery, market accessibility, infrastructure, and technological advancement [65,82]. The literature often identified human and financial capital, including resources like education and health care, as a commonly mentioned hindrance [43,65,82].

- e.

- Inadequate access to land

The unfriendly traditional practices governing land acquisition and owners usually lowers the chances to secure land and often discourage youths considering agribusiness as a career path [22]. For example, [45,54] indicated that the younger generation in Malawi and Kenya mostly secure land through inheritance, which poses challenges for them to establish and operate a viable agribusiness enterprise. Therefore, the active engagement of young people in the agricultural sector may be facilitated by granting them access to land, leading to enhanced productivity, profitability, and the promotion of sustainable development.

5. Discussion

This systematic review examined the prevalence factors influencing youth attitude towards involvement in agribusiness in Africa. The review also assessed studies that focus on the effect of youth intervention programs, and the challenges associated with their engagement in agribusiness activities.

The findings from the systematic review revealed a diverse spectrum of perspectives among young people in agribusiness. Most research papers revealed that youth consider agribusiness as a very profitable business that offers many employment prospects. The results support the previous study conducted by [85], who reported that the pursuit of financial gain primarily influences the motivation and involvement of rational investors in business activities. However, four of the review papers reported that young people viewed agribusiness as a tedious occupation with relatively low remuneration. The findings are consistent with the previous studies of [86,87] in Malaysia which revealed that young people perceived the sector as drudgery, with lack of financial gain and an association with rural life. Therefore, effort is needed to change the negative perception in a bid to encourage more young people to accept farming as a career. For example, one study [29] found that young cocoa farmers that benefited from agricultural training had considered agriculture as a viable option for career development. Their negative perception had changed because of their exposure to agricultural training. In another study [18], the author noted that investment is needed for more skills training and support in the form of grants and loans to encourage their continued participation in the agricultural sector. Aside from that, the author emphasized the need to address the issue of land accessibility, financial resources, and gender-related obstacles [18].

Our analysis revealed a range of factors influencing youth involvement in agribusiness. These factors include access to finance, land, technology, and training as key determinant of youth involvement in agribusiness. Socio-economic factors such as age, gender, and education were reported in several studies as key drivers of youth involvement in agribusiness [7,50,53,73,74]. The findings from this review underscore the need to tackle socioeconomic disparities that negatively impact the involvement of young adults in the agricultural sector. The research findings emphasized the need to rectify gender disparities within the agricultural sector to promote the inclusion of all young people, irrespective of gender. Interventions, including mentorship programs, education initiatives, and training endeavors, can foster equity and engender increased interest among young people, irrespective of gender, in pursuing agriculture as a viable and purposeful career path [18].

Moreover, the analysis revealed that the utilization of technology further contributed to increasing the number of young people in the agricultural sector. Technology facilitates access to market information, weather predictions, and agricultural advice [26,34,69]. Therefore, investments in ICT infrastructure and training are essential in promoting the use of agricultural technologies among young people. This may include Internet and mobile network access, as well as the provision of guidance about the utilization of fundamental software and applications.

Concerning the impact of training programs, this review established that the intervention program reported in most of the papers indicated young individuals were equipped with the requisite skills and information necessary for achieving success in agribusiness venture. The training intervention had provided young people with employment opportunities, reduced poverty, and improved food security. For example, various programs have been implemented in Nigeria, such as the Youth in Agriculture Initiative (YIA), the N-Power Agro program, and the Growth Enhancement Support Scheme (GESS) [14]. These projects have shown promising outcomes in empowering young people and enhancing their sustainable livelihoods [70,88]. Furthermore, it is imperative that these programs have sufficient funding and actively interact with pertinent stakeholders, including youth and community leaders, to guarantee their appropriate design and implementation.

Regarding challenges, the analysis revealed that the lack of access to financial resources is the most significant barrier affecting youth aspiration toward engaging in agricultural activities [76]. The inability of young people to secure loans was associated with limited collateral or credit history. Additionally, they are subjected to high-interest rates and poor repayment conditions. The review further revealed that the lack of access to land was identified as a key factor constraining young individuals from engaging in agricultural activities. A surge in land prices and stiff competition from alternative land use remain a challenge for young individuals to access land for agricultural purposes. However, some papers recommended improvement in infrastructure and other support services to foster young people to embrace agribusiness [22,23]. Capacity building programs can potentially enhance the level of engagement of young people in agriculture.

The outcomes of this desk review contributed to the SCCT framework by capturing the combined effect of internal and external factors in shaping young people’s interest in agribusiness. The findings provide support to the previous review by [76], who reported that behavioral capacity, self-efficacy, and observational learning are the most often seen components of social cognitive theory (SCCT) in interventions focused on cooking and food preparation abilities. Similar findings were observed in [89], which investigated young people’s career choices. Youths from collectivist cultures were primarily influenced by family expectations, with a higher degree of career alignment with their parents, leading to improved professional confidence and self-efficacy [22]. On the other hand, in individualistic settings, the choice of profession was primarily affected by personal interests, and young people tended to make more autonomous career decisions [22]. The findings suggest that several cognitive, behavioral, and environmental variables influence young people’s interest and involvement in agribusiness.

Based on the review findings, it is essential to formulate policies and implement programs to facilitate enhanced accessibility to financial resources for agricultural initiatives among young people. One potential solution to facilitate the acquisition of land for agricultural use by young individuals is the implementation of land tenure law reforms. Expanding the availability of training programs aimed at equipping young people with agricultural skills and knowledge is recommended. Advocating for integrating technological advancements in the agricultural sector enhances the production and efficiency of young people. Promoting female representation and engagement in agricultural education and training initiatives is essential.

6. Limitations

This review focused solely on articles published between 2012 and 2022 in English, potentially overlooking relevant research conducted before 2012 and other publications in other languages like French and Arabic. Furthermore, the study relied heavily on digital libraries, which may have resulted in a bias towards published and readily available studies, potentially disregarding significant grey literature or unpublished research. It is essential to mention that the study focused specifically on Africa. Therefore, the conclusions drawn from the research may only apply to specific regions or countries within that area.

7. Future Research Directions

Future studies should include various sources from the literature to guarantee a comprehensive examination. Identifying traits that influence youth participation in agriculture in various geographic areas would be interesting. In addition, the research explored the perspectives and factors that affect youth participation in agriculture. However, conducting a more in-depth examination of subcategories, such as gender or disparities between rural and urban areas, could yield additional valuable information. Qualitative research is imperative to fully understand young people’s motivations, goals, and obstacles in agriculture.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.B., A.G. and P.P.; methodology, M.U. and A.H.W.; software, M.B.; validation, M.B. and A.H.W.; formal analysis, M.B. and M.U.; investigation, M.B.; data curation, M.B.; writing—original draft preparation, M.B., A.G. and M.U.; writing—review and editing, M.U., P.P., A.F. and R.S.; supervision, A.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Information consent was obtained from all the participants in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this finding are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Summary of the studies included in the review.

Table A1.

Summary of the studies included in the review.

| References | Country | Study Design | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ng’atigwa et al. (2020) [68] | Tanzania | Quantitative | Several factors have been identified as significantly affecting young adult participation in horticultural agribusiness. Positive factors include primary school education, education beyond form IV, management innovation, credit availability, a favorable perception of horticulture for agribusiness, and improved packaging materials. However, sex and land size were found to have a negative and significant effect on adolescent participation in horticulture agribusiness. These findings can inform policymakers and stakeholders in the agricultural sector about the measures to increase adolescent participation in horticulture agribusiness. |

| Akrong and Kotu (2022) [63] | Benin | Quantitative | Young people of wealthier backgrounds are more likely to launch agricultural ventures. In contrast, those from lower-income backgrounds, with less schooling, no experience in business, and living in urban areas are more likely to launch nonagricultural enterprises. |

| Baloyi et al. (2022) [47] | South Africa | Quantitative | The study found that young people in rural areas were enthusiastic about participating in all stages of the agricultural value chain. However, their participation varied according to several factors, including those related to their family and their access to education, land, and technology. Their access to other services and resources and their high dependence on them dampened their enthusiasm for involvement. |

| Ouko et al. (2022) [28] | Kenya | Review | The research revealed that young people in Kenya face socioeconomic barriers that prevent them from pursuing agripreneurship, such as preconceived notions, a lack of skills, a scarcity of resources (such as land, money, and contacts), a lack of knowledge about the market, the effects of climate change, the inadequacy of current policies, and the lack of demand for their products. |

| Kodom et al. (2022) [29] | Ghana | Quantitative | The findings showed that the youth believed that the cultivation of cocoa is an occupation for the elderly, contributing to the lack of interest in cocoa cultivation among the young. Beneficiaries have used the newfound information and abilities to improve the quality and quantity of cocoa fields, shifting public opinion in a favorable direction. |

| Mkong et al. (2021) [48] | Cameroon | Quantitative | The findings highlighted that factor such as the mother’s educational background, family income, and agricultural experience at home have a considerable impact on whether a student chooses agriculture as a college major. Similarly, where a person grew up and their degree of education affect their preferred involvement in the agricultural sub-sector. Increased participation of young people in agricultural and rural economic activities might be achieved by making the agricultural industry more appealing and improving the sector’s working conditions. |

| Adeyanju et al. (2021) [76] | Nigeria | Quantitative | The descriptive result showed that most respondents (56%) reported access to finance as their major barrier to participating in agribusiness and agribusiness training. Other barriers include a need for more mentorship and information. |

| Adeyanju et al. (2021) [76] | Nigeria | Quantitative | The research showed that factors such as age, sex, level of education, family composition, farm characteristics, and individuality played a role in finding whether young people participated in the Fadama Boys programme. The three main challenges were more resources, role models, and knowledge. |

| Unnikrishnan et al. (2022) [75] | Ghana | Quantitative | The results of the impact evaluation suggest that young people who participated in the programme were more willing to become farmers, improve their farming techniques, and increase their cocoa production. In addition, they increased their use of financial institutions, including banks, mobile money, and community lending and savings groups. |

| Bello et al. (2022) [70] | Nigeria | Mixed method | The findings showed that participation in an agricultural programme alleviated poverty among youth, with a 28% decrease in exposure to future poverty. Intervention programmes, such as YIAPs, should be increased and scaled up to promote youth welfare and reduce/eradicate poverty and susceptibility to poverty. |

| Bello et al. (2021) [69] | Nigeria | Mixed method | The success of the YIA programme with young people was significantly affected by factors such as their level of education, access to training, participation in non-farming activities, membership in youth groups, capacity to get loans, production resources, and geographic location. Increasing participation rates and job prospects can be achieved by strengthening social networks, approving credit systems, upgrading vocational education, and progressing in education. |

| Fasakin et al. (2022) [42] | Nigeria | Quantitative | The results of the PSM and IPWRA indicate that a significant increase in youth participation in agriculture may lead to a 1088.78 kg/ha improvement in paddy rice production, with also an increase in their income. The government and other stakeholders must promote easy access to loans and land without collateral to get more young people involved in intensive agriculture. |

| Haggblade et al. (2015) [7] | Undefined | Qualitative | The study’s results suggest that young people from rural areas are drawn to agribusiness because of its lucrative opportunities. On the contrary, young people from urban areas are drawn to the field because of their access to higher education in the sciences. |

| Ogunmodede et al. (2020) [14] | Nigeria | Quantitative | The results revealed that those who participated in N-Power Agro made more money than those who did not. Factors such as age, education level, years in agribusiness, and job status significantly affected the decision to start a business and join the programme. |

| Geza et al. (2021) [88] | Undefined | Review | It was discovered that current agricultural initiatives focus primarily on increasing productivity but result in poor incomes and insufficient social protection. The surveyed youth also shared a pessimistic view that agriculture can improve living conditions. This may be because young people recognize the importance of the agriculture sector for overall economic development but need to be actively involved in it. |

| Geza et al. (2022) [43] | South Africa | Review | The results indicated that the younger generation continues to encounter considerable obstacles in the demand and supply of the labor market. This is due to a lack of access to productive resources, such as land and finance. There is an urgent need for greater inclusiveness in the development and execution of policies, which restricts their participation in agricultural and rural development programmes. |

| Tarekegn et al. (2022) [64] | Ethiopia | Quantitative | According to the results of the probit model, the variables education level, credit-getting bureaucracy, lack of starting capital, fear of the group, risk and uncertainty, and lack of working space all play a significant role in determining whether young people engage in farm businesses. |

| Maïga et al. (2020) [44] | Undefined | Review | Young people who participated in skill building programmes could find employment, start their agriculture businesses, improve their performance, and become involved in agricultural extension service support. |

| Mabe et al. (2020) [49] | Ghana | Quantitative | Participation in cocoa value chain activities is influenced by access to land, participation in training programmes in cocoa production, membership of the Next Generation Cocoa Youth Programme (MASO), access to agricultural credit, and other demographic characteristics. |

| Lachaud et al. (2018) [90] | Zimbabwe | Quantitative | The findings show that between 2011 and 2014, the TREE programme raised recipients’ income by an average of $787 and their child and health spending by an average of $236 and $101, respectively, compared to nonbeneficiaries. |

| Twumasi et al. (2020) [65] | Ghana | Quantitative | Farmers with limited access to credit were more likely to experience a lengthy loan application process and disbursement period and reduced passion for their agricultural endeavors. There was an inverse relationship between credit constraints and levels of education, age, savings, and parental profession. |

| Rogito et al. (2020) [58] | Kenya | Quantitative | Access to agriculture financing in Kakamega County represents a significant barrier, exacerbated by the need for greater participation of youth in the agricultural value chain. This lack of financial services has a negative effect on the entire value chain, excluding the final consumer. |

| Mmbengwa et al. (2021) [66] | South Africa | Mixed method | According to the findings, tenacity, personal drive, innovation, and a good attitude are essential for young entrepreneurs to achieve success. Capacity development centered on technical skills is needed to promote efficient and successful entrepreneurship. Furthermore, adolescents need enough resources and exposure to commercial agricultural activities. |

| Magagula et al. (2020) [25] | South Africa | Quantitative | The study revealed that the youth had a favorable impression of the agricultural sector as an economic opportunity. The combination of this optimism with extensive agricultural instruction in secondary schools and substantial financial assistance has increased the number of people considering or actively engaged in agribusiness. |

| Cheteni, (2016) [62] | South Africa | Quantitative | The results show that the variables youth programmes, programme availability, and resources were statistically significant in explaining the factors that affect youth participation in agricultural activities. |

| Giuliani et al. (2017) [26] | Morroco | Mixed Method | The findings show that young people in rural areas want to work in agriculture, but that more infrastructure investment is needed to prevent them from leaving. Maintaining a rural lifestyle requires prioritizing expanded opportunities for learning and education. |

| Yami et al. (2019) [6] | Undefined | Review | The interventions adopted by African governments and development partners have effectively increased youth participation in agriculture through capacity building, financial assistance, and mentoring. |

| Bonnke et al. (2022) [82] | DRC | Quantitative | The findings show that tomato producers need more access to agricultural credit, with informal sources providing the most cash-based credit. Lack of information, fear of credit default, and the absence of microfinance institutions are the top three obstacles to access. Access to agricultural credit is dependent on total household income, gender, and participation in a cooperative of tomato producers. |

| Ephrem et al. (2021) [50] | DRC | Quantitative | Empirical evidence suggests that the degree of endorsement and respect youth receive from their locality was significantly associated with their involvement in agricultural pursuits. Furthermore, it has been discovered that the psychological capital that individuals possess in their youth plays a key role in shaping their aspirations towards agribusiness. |

| Mdege et al. (2022) [56] | Uganda | Qualitative | The larger community/national environment, individual circumstances, and individual and collective agencies influence the participation of rural youth in sweet potato farming and agribusiness. Strategies to increase young people’s engagement in the agricultural value chain should consider their intersectional identities and address concerns at the national and neighborhood levels. |

| Akrong et al. (2020) [55] | Ghana | Quantitative | The findings of the econometric model suggest that the demographic characteristics of young people exhibit a higher propensity to engage in agricultural activities due to their younger age, educational attainment, and access to credit and extension services. Retired farmers who obtained loans and automobiles also engaged more with high-value marketplaces. |

| Jolex and Tufa (2022) [71] | Malawi | Quantitative | The results show that profitability increases with the number of ICT tools used to receive and send relevant information to agribusinesses. |

| Ikuemonisan et al. (2022) [51] | Nigeria | Quantitative | Most of the students in the study were below the poverty line, and only 27% were interested in a future in agriculture. However, agribusiness was chosen mainly because of how they felt about their school, its learning environment, the quality of its teachers, and the accessibility of its courses. |

| Ikuemonisan et al. (2022) [91] | Nigeria | Quantitative | The study found that entrepreneurial traits significantly influenced youth’s willingness to take advantage of agribusiness opportunities once an individual’s entrepreneurial intention moderated each trait. |

| Fani et al. (2021) [27] | Cameroon | Quantitative | Young women entrepreneurs in agriculture are competitive and have substantial opportunities but should be encouraged to earn greater credit for purchasing improved seed types and agrochemicals. |

| Henning et al. (2022) [33] | South Africa | Quantitative | The study has revealed that the selection of a career in agriculture is little in the aspirations of the youth. However, it is imperative to encourage young people to participate in agriculture by providing them with educational and experiential opportunities. Regrettably, the absence of grants and the predominant notion of agriculture as an unexplored territory impede the participation of youth. |

| Lindsjö et al. 2021 [83] | Malawi | Quantitative | According to our findings, the younger generation has less access to land than the older generations, and the maize yields remained poor between 2008 and 2017. This implies that the potential for sustainable agricultural intensification is still low unless land access and financial assistance for young people are prioritized. |

| Sumberg et al. (2017) [59] | Ghana | Qualitative | These findings highlight the need for a more customized approach to policy and programming that addresses rural employment, as they show that young people have a negative attitude toward farming due to various views and understandings. |

| Sumberg et al. (2012) [92] | Ghana | Qualitative | More data and research must be needed to inform policy responses concerning young people and agriculture in Africa. To combat this, researchers must examine the shifting landscape of job openings in the agricultural and agri-food industries for young people. |

| Okello et al. (2020) [72] | Tanzania | Quantitative | Research discovered that ICT instruments (mobile phones, television, and radio) are interconnected, and factors such as extension contacts, energy installation, buyer confidence, market knowledge, and receiving remittances all influence. |

| Inegbedion and Islam (2020) [52] | Nigeria | Quantitative | According to the results, the most crucial factor was found to be regulation, which boosted motivation to develop an entrepreneurial mindset, learn about new inventions, and start a business after college. |

| Osabohien et al. (2021) [2] | Nigeria | Quantitative | The findings indicated that gender and the determination to remain in agriculture increase the likelihood that young people will engage in agriculture as a primary occupation, contributing to household income per capita and reducing poverty by 17%. |

| Bezu and Holden, (2014) [60] | Ethiopia | Quantitative | According to the findings, the dramatic increase in youth emigration over the last six years may be directly attributed to rural southern young people’s lack of access to agricultural land. Our econometric modeling showed that young people need more access to land to pursue farming. |

| Bouichou et al. (2021) [53] | Ghana | Quantitative | The youth in our sample who came from cocoa farming households expressed gratitude for the educational opportunities their family had provided. Farm ownership was seen favorably, and the varied experiences of farmers affected their long-term goals and current approaches. |

| Anyidoho et al. (2012) [32] | Morocco | Qualitative | Binary logistic regression analysis revealed that sociodemographic factors, individual perspectives, prior experience, and cooperative behaviors were statistically significant. The findings also imply that the risks and financial restrictions of agribusiness have a negative effect on the entrepreneurial inclinations of youth and women in agricultural cooperatives. |

| Larue et al. (2021) [57] | Kenya | Mixed Method | The results show that the youth had limited interest in agriculture. This image changes when they cannot choose between mutually exclusive farming options and other livelihood goals. |

| Swarts and Aliber (2013) [84] | South Africa | Qualitative | According to empirical studies, the proclivity of young people towards agriculture is contingent upon the availability of the requisite resources to facilitate their active participation in the field. This suggests that the pursuit of monetary benefits has considerable influence over their actions. |

| Irungu et al. (2015) [19] | Kenya | Qualitative | The use of ICTs in agriculture has broadened opportunities and encouraged young people to work in profitable agriculture. ICT tools should be easy and inexpensive, the material should be valued, cherished, localised, and reliable, and the usage of YouTube, Twitter, and WhatsApp should be increased and widely popularized. |

| Badiru and Akande (2019) [79] | Nigeria | Quantitative | Most of the respondents that had interacted with the records were aware of their agricultural content and remembered it. More (54.9%) had an unfavorable opinion of their mobilization potential and needed more credit facilities. |

| Uduji et al. (2021) [78] | Nigeria | Quantitative | The result of using a bivariate probit model showed that GESS significantly affects the innovations of rural youth in agriculture. |

| Uduji et al. (2021) [80] | Nigeria | Quantitative | The findings of the combined propensity score matching and logit model suggested that the GMoU model has a considerable influence on the growth of informal farm entrepreneurship in general, but it has a negative impact on young rural people in the targeted agricultural clusters. |

| Olanrewaju et al. (2020) [81] | Nigeria | Quantitative | The study results showed that marital status, education, access to credit, and membership in cooperative associations were significant determinants of participation in ABP among young rice farmers. |

| Mpetile et al. (2021) [73] | South Africa | Qualitative | Analyzing the life experiences of aspiring Black farmers as business owners revealed the importance of factors such as personal influences, the role of community, the desire for political power through economic stability, and the impact of socioeconomic factors on the decision to enter the agricultural career path. |

| Marwa and Manda (2022) [77] | Tanzania | Quantitative | Depending on socioeconomic and institutional factors, such as access to extension services, contract farming increased French bean yields and earnings by 17%, 34%, or 37.5%, respectively. |

| Kaki et al., (2022) [54] | Benin | Quantitative | The significant factors influencing agricultural students’ entrepreneurial intention in agribusiness were age, major field of study, type of university attended, previous experience in agribusiness, a role model as a friend, and belief in the agribusiness environment. |

| Yeboah et al. (2019) [74] | Undefined | Qualitative | Family and social ties are essential for young entrepreneurs to access resources such as land, capital, and input. The accumulation of housing, furniture, and savings by young people reflects the dynamism of rural economies, the facilitation of social relations, and hard labor. However, it is difficult to remain afloat due to obstacles and risks. |

| Kidido et al. (2017) [67] | Ghana | Quantitative | Empirical evidence has shown that various demand- and supply side determinants, including exorbitant land prices and rivalry from residential developers, impede the youth’s entry to farming land in rural and peri-urban regions. Further academic research and widespread knowledge dissemination are imperative to address this issue. |

References

- Ackah-Baidoo, P. Youth unemployment in resource-rich Sub-Saharan Africa: A critical review. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2016, 3, 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anser, M.K.; Osabohien, R.; Olonade, O.; Karakara, A.A.; Olalekan, I.B.; Ashraf, J.; Igbinoba, A. Impact of ICT adoption and governance interaction on food security in West Africa. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Proceeding of The Future of Food and Agriculture: Trends and Challenges; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bellows, J.; Miguel, E. War and local collective action in Sierra Leone. J. Public Econ. 2009, 93, 1144–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bersaglio, B.; Enns, C.; Kepe, T. Youth under construction: The United Nations’ representations of youth in the global conversation on the post-2015 development agenda. Can. J. Dev. Stud. 2015, 36, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yami, M.; Feleke, S.; Abdoulaye, T.; Alene, A.D.; Bamba, Z.; Manyong, V. African rural youth engagement in agribusiness: Achievements, limitations, and lessons. Sustainability 2019, 11, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haggblade, S.; Chapoto, A.; Drame-Yayé, A.; Hendriks, S.L.; Kabwe, S.; Minde, I.; Mugisha, J.; Terblanche, S. Motivating and preparing African youth for successful careers in agribusiness: Insights from agricultural role models. J. Agribus. Dev. Emerg. Econ. 2015, 5, 170–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roepstorff, T.; Wiggins, S.; Hawkins, A.T. The Profile of Agribusiness in Africa. In Agribusiness for Africa’s Prosperity; Yumkella, K.K., Kormawa, P.M., Roepstorff, T.M., Hawkins, A.M., Eds.; United Nations Industrial Development Organization: Vienna, Austria, 2011; pp. 38–56. [Google Scholar]

- International Labor Organization. Global Employment Trends for Youth 2022: Investing in Transforming Futures for Young People; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mukembo, S.C.; Edwards, M.C.; Ramsey, J.W.; Henneberry, S.R. Intentions of Young Farmers Club (YFC) Members to Pursue Career Preparation in Agriculture: The Case of Uganda. J. Agric. Educ. 2015, 56, 16–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwaura, G.M. Just farming? Neoliberal subjectivities and agricultural livelihoods among educated youth in Kenya. Dev. Change 2017, 48, 1310–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, K.M.; Filmer, D.P.; Fox, M.L.; Goyal, A.; Mengistae, T.A.; Premand, P.; Ringold, D.; Sharma, S.; Zorya, S. Youth Employment in Sub-Saharan Africa: Abrégé (French); The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Unnikrishnan, V.; Pinet, M.; Marc, L.; Boateng, N.A.; Boateng, E.S.; Pasanen, T.; Atta-Mensah, M.; Bridonneau, S. Impact of an integrated youth skill training program on youth livelihoods: A case study of cocoa belt region in Ghana. World Dev. 2022, 151, 105732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunmodede, A.M.; Ogunsanwo, M.O.; Manyong, V. Unlocking the potential of agribusiness in Africa through youth participation: An impact evaluation of N-power Agro Empowerment Program in Nigeria. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyanju, D.; Mburu, J.; Mignouna, D. Youth agricultural entrepreneurship: Assessing the impact of agricultural training programmes on performance. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- African Union. The African Youth Decade 2009–2018 Plan of Action. In Accelerating Youth Empowerment for Sustainable Development: Road Map towards the Implementation of the African Youth Charter; African Union: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Checkoway, B. What is youth participation? Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2011, 33, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henning, J.I.; Matthews, N.; August, M.; Madende, P. Youths’ perceptions and aspiration towards participating in the agricultural sector: A South African case study. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Fernández, M.C.; Serrano-Bedia, A.M.; Pérez-Pérez, M. Entrepreneurship and family firm research: A bibliometric analysis of an emerging field. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2016, 54, 622–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irungu, K.R.G.; Mbugua, D.; Muia, J. Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) Attract Youth into Profitable Agriculture in Kenya. East Afr. Agric. For. J. 2015, 81, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]