Global Threats to Sustainability: Evolving Perspectives of Latvian Students (2016–2022)

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Sustainability

1.2. Citizenship Education

1.3. Students’ Attitudes as a Potential Predictor of Future Actions

1.4. Background Aspects and Citizenship Knowledge

1.5. Study Purpose and Hypotheses

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

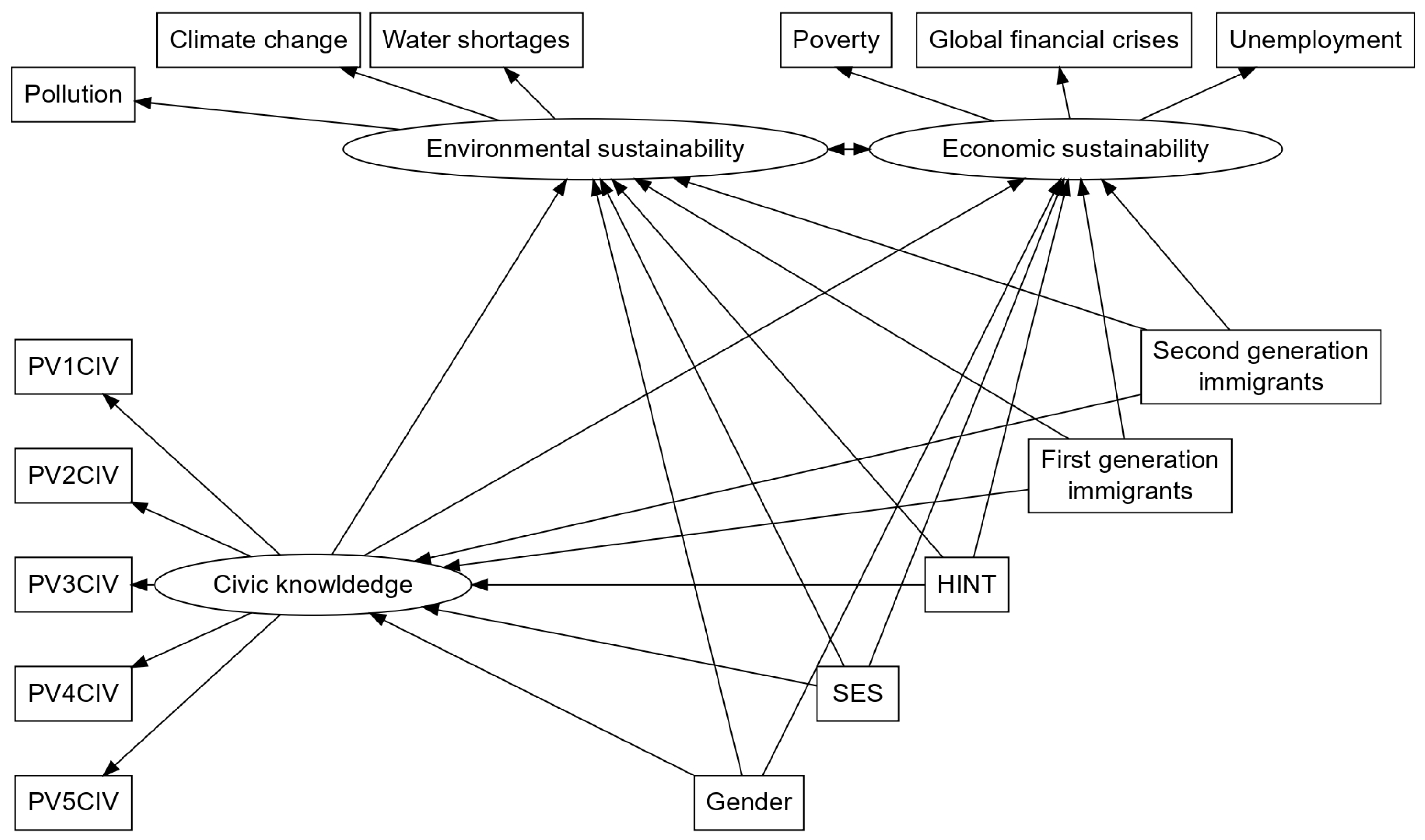

3.2. Model Construction

3.3. Model Results

3.3.1. Gender

3.3.2. Socioeconomic Status (SES)

3.3.3. Parental Interest in Political and Social Issues (S_HINT)

3.3.4. Immigration Status

3.3.5. Civic Knowledge

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations. Youth. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/global-issues/youth?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 3 December 2024).

- Olsson, D.; Gericke, N.; Boeve-de Pauw, J. Students’ Action Competence for Sustainability and the Effectiveness of Sustainability Education. Environ. Sci. Proc. 2022, 2, 14011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LIKUMI.LV. Latvijas Republikas Satversme. Available online: https://likumi.lv/ta/en/en/id/57980-the-constitution-of-the-republic-of-latvia (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- Europa.eu. Organisation of the Education System and of Its Structure. Available online: https://eurydice.eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-education-systems/latvia/organisation-education-system-and-its-structure (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung. 2022 Youth Study Baltic Countries; Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung e.V.: Bonn, Germany, 2022; Available online: https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/id/19168-20220509.pdf (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- Hjūza, D.; Boržs Borbējs, T. Jauniešu Bezdarbs: Mūslaiku Krīze. Mūžilga Karjeras Atbalsta Rīcībpolitiks Nozīme Darba Piedāvājuma un Pieprasījuma Jomā. Eiropas Mūžilga Karjeras Atbalsta Politikas Tīkls (EMKAPT). Available online: https://euroguidance.viaa.gov.lv/mod/book/view.php?id=53&chapterid=360 (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- Medne, D.; Lastovska, A.; Lāma, G.; Grava, J. The Development of Civic Competence in Higher Education to Support a Sustainable Society: The Case of Latvian Higher Education. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleespies, M.; Dierkes, P. The Importance of the Sustainable Development Goals to Students of Environmental and Sustainability Studies—A Global Survey in 41 Countries. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2022, 9, 1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinchenko, V. Global Institutional Transformations and Modern Educational and Scientific Strategies for the Paradigm of Sustainable Development of Society. Skhid 2022, 3, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Education for Sustainable Development: A Roadmap. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000374802 (accessed on 27 September 2024).

- UNESCO. Education for Sustainable Development Goals: Learning Objectives; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau, J.-J. The Social Contract; Dutton: New York, NY, USA, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, J. Democracy and Education; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1916. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, T.H. Citizenship and Social Class and Other Essays; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Torney-Purta, J.; Schwille, J.; Amadeo, J.-A. Civic Education Across Countries: Twenty-Four National Case Studies from the IEA Civic Education Project; IEA: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Westheimer, J.; Kahne, J. What Kind of Citizen? The Politics of Educating for Democracy. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2004, 41, 237–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, D. Citizenship Education in Comparative Context. In International Civic and Citizenship Education Study (ICCS); Schulz, W., Ainley, J., Fraillon, J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2010; pp. 9–29. [Google Scholar]

- Biesta, G.J.J. Beyond Learning: Democratic Education for a Human Future; Paradigm Publishers: Boulder, CO, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz, W.; Ainley, J.; Fraillon, J.; Losito, B.; Agrusti, G.; Damiani, V.; Friedman, T. Education for Citizenship in Times of Global Challenge; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz, W.; Ainley, J.; Fraillon, J.; Losito, B.; Agrusti, G.; Friedman, T. Becoming Citizens in a Changing World: IEA International Civic and Citizenship Education Study 2016 International Report; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ștefanachi, B.; Grecu, S.-P.; Chiriac, H.C. Mapping Sustainability across the World: Signs, Challenges and Opportunities for Democratic Countries. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Report 2021. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2021/The-Sustainable-Development-Goals-Report-2021.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2024).

- Pickering, J.; Hickmann, T.; Bäckstrand, K.; Kalfagianni, A.; Bloomfield, M.; Mert, A.; Ransan-Cooper, H.; Lo, A.Y. Democratising Sustainability Transformations: Assessing the Transformative Potential of Democratic Practices in Environmental Governance. Earth Syst. Gov. 2022, 11, 100131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Education Monitoring Report Team. Global Education Monitoring Report. Leadership in Education: Lead for Learning. 2024. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000391406 (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Haduong, P.; Jeffries, J.; Pao, A.; Webb, W.; Allen, D.K.; Kidd, D. Who am I and what do I care about? Supporting civic identity development in civic education. Educ. Philos. Theory 2023, 19, 185–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kals, E.; Müller, M. Education for sustainability. In Handbook of Moral and Character Education Sustainability Education; Nucci, L., Krettenauer, T., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Van Poeck, K.; Vandenabeele, J. Learning from sustainable development: Education in the light of public issues. Environ. Educ. Res. 2012, 18, 541–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araneda, E.Z.; Palavecino, A.C.; Menzel, S. Acerca de las creencias, actitudes y visión ecológica del mundo en estudiantes chilenos. Summa Psicol. 2013, 3, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICCS|IEA.nl. Available online: https://www.iea.nl/data-tools/repository/iccs (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- Schulz, W.; Carstens, R.; Losito, B.; Fraillon, J.; Eichhorn, C.; Serrano, L.; Isac, M.M.; Ainley, J. ICCS 2022 International Report: Citizenship Education in an Age of Uncertainty; International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement: Amsterdam, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Are Students Ready to Take on Environmental Challenges? OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Embedding Values and Attitudes in Curriculum: Shaping a Better Future; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. PISA 2018 Results (Volume VI): Are Students Ready to Thrive in an Interconnected World? OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, D.; Gericke, N. The Adolescent Dip in Students’ Sustainability Consciousness—Implications for Education for Sustainable Development. J. Environ. Educ. 2015, 47, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, S.; Watted, S.; Zion, M. Contribution of an Intergenerational Sustainability Leadership Project to the Development of Students’ Environmental Literacy. Environ. Educ. Res. 2021, 27, 1723–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balundė, A.; Perlaviciute, G.; Truskauskaitė-Kunevičienė, I. Sustainability in Youth: Environmental Considerations in Adolescence and Their Relationship to Pro-Environmental Behavior. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 582920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundermann, A.; Fischer, D. How Does Sustainability Become Professionally Relevant? Exploring the Role of Sustainability Conceptions in First Year Students. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakaria, N.F.; Rahim, H.A.; Paim, L.; Zakaria, N.F. The Mediating Effect of Sustainable Consumption Attitude on Association between Perception of Sustainable Lifestyle and Sustainable Consumption Practice. Asian Soc. Sci. 2019, 15, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainley, J.; Schulz, W.; Friedman, T. ICCS 2009 Encyclopedia: Approaches to Civic and Citizenship Education Around the World; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cheah, S.; Huang, L. Environmental citizenship in a Nordic civic and citizenship education context. Nordic J. Comp. Int. Educ. 2019, 3, 38–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ozanne, L.K.; Humphrey, C.; Smith, P.M. Gender, environmentalism, and interest in forest certification: Mohai’s Paradox revisited. Soc. Nat. Resour. 1999, 12, 455–467. [Google Scholar]

- Odrowąż-Coates, A. Definitions of sustainability in the context of gender. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Amar, W.; Chang, M.; McIlkenny, P. Board gender diversity and corporate response to sustainability initiatives: Evidence from the Carbon Disclosure Project. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 132, 705–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franz-Balsen, A. Gender and (un)sustainability—Can communication solve a conflict of norms? Sustainability 2014, 6, 1973–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreby, J.; Stutz, L. Making something of the sacrifice: Gender, migration and Mexican children’s educational aspirations. Child. Soc. 2011, 25, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsberg, S. The symbolic gift of education in migrant families and compromises in school choice. Brit. J. Sociol. Educ. 2022, 43, 349–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, T.; Ee, M.; Anh, H.L.; Yeoh, B. Securing a better living environment for left-behind children: Implications and challenges for policies. Asia Pac. Migr. J. 2013, 22, 421–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mónus, F. Environmental education policy of schools and socioeconomic background affect environmental attitudes and pro-environmental behavior of secondary school students. Environ. Educ. Res. 2022, 28, 196–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, A.; Petocz, P.; Taylor, P. Business students’ conceptions of sustainability. Sustainability 2009, 1, 662–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzalbs, A. Common Agricultural Policy in Latvia: Sustainability Assessment. RTU Constr. Sci. 2023, 24, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, W.; Losito, B.; Carstens, R.; Fraillon, J. ICCS 2016 Technical Report. IEA International Civic and Citizenship Education Study 2016; International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement: Amsterdam, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz, W.; Friedman, T.; Fraillon, J. ICCS 2022 Technical Report. IEA International Civic and Citizenship Education Study 2022; International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement: Amsterdam, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Afana, Y.; Brese, F.; Kowolik, H.; Cortés, D.; Schulz, W. ICCS 2022 User Guide for the International Database; International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement: Amsterdam, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, K.H.; Brese, S.; Schulz, F.; Carstens, W.R. ICCS 2016 User Guide for the International Database; International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement: Amsterdam, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024; Available online: https://www.r-project.org/ (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- Lumley, T. Analysis of Complex Survey Samples. J. Stat. Softw. 2014, 9, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosseel, R. Lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. J. Stat. Softw. 2012, 48, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberski, D. Lavaan. survey: An R package for complex survey analysis of structural equation models. J. Stat. Softw. 2014, 57, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, T.S.; Michel, J.; Bryan, A.; Canosa, E.; Gamalski, C.; Jones, K.; Moghtader, J. An Exploration of the Relationship between Sustainability-Related Involvement and Learning in Higher Education. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido-Capurro, V.; Olivera-Carhuaz, E.; García-Salazar, G.; Acevedo-Flores, J.; Morillo-Flores, J. Actitud y Comportamiento de los Estudiantes de una Universidad Privada y su Compromiso con la Sostenibilidad Ambiental. J. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 11, e415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, D.; Gericke, N. The effect of gender on students’ sustainability consciousness: A nationwide Swedish study. J. Environ. Educ. 2017, 48, 357–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dictoro, V.P.; Lourenço, A.B.; Malheiros, T. Práticas de sustentabilidade em uma parceria escola-universidade: Percepções de alunos e professores. Rev. Bras. Educ. Ambient. 2023, 18, 171–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čekse, I.; Kiris, K.; Alksnis, R.; Geske, A.; Kampmane, K. The New Reference Point for Civic Education in Latvia: First International and Latvian Results from the International Civic Education Study IEA ICCS 2022; LU PPMF Izglītības Pētniecības Institūts: Riga, Latvia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Perrault, E.K.; Clark, S.K. Sustainability in the University Student’s Mind: Are University Endorsements, Financial Support, and Programs Making a Difference? J. Geosci. Educ. 2017, 65, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R. A corpus-assisted discourse study of Chinese university students’ perceptions of sustainability. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1124909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullis, I.V.S.; von Davier, M.; Foy, P.; Fishbein, B.; Reynolds, K.A.; Wry, E. PIRLS 2021 International Results in Reading; TIMSS & PIRLS International Study Center at Boston College: Chestnut Hill, MA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Davier, M.; Kennedy, A.; Reynolds, K.; Fishbein, B.; Khorramdel, L.; Aldrich, C.; Bookbinder, A.; Bezirhan, U.; Yin, L. TIMSS 2023 International Results in Mathematics and Science; TIMSS & PIRLS International Study Center at Boston College: Chestnut Hill, MA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolter, I.; Braun, E.; Hannover, B. Reading is for girls!? The negative impact of preschool teachers’ traditional gender role attitudes on boys’ reading related motivation and skills. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, J.M.; Tirrell, A.; Moomaw, W.R.; Ragueneau, O. Sustainability. In Routledge Handbook of Global Environmental Politics; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; pp. 217–227. [Google Scholar]

- Nazaryan, H.; Mkrtchyan, A.; Tumanyan, G. Information Sphere Challenges in the Processes of Formulation of Armenian Civil Identity. Soc. Bull. Yerevan Univ. 2021, 12, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serdeczny, O. The Effects of Political Knowledge Use by Developing Country Negotiators in Loss and Damage Negotiations. Glob. Environ. Politics 2023, 23, 12–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, E.S.; Mistry, R.S. Parent Civic Beliefs, Civic Participation, Socialization Practices, and Child Civic Engagement. Appl. Dev. Sci. 2015, 20, 44–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pancer, S.M. The Influence of Parents, Families, and Peers on Civic Engagement. In The Psychology of Citizenship and Civic Engagement; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Central Statistical Bureau of Latvia. Population Growth in 2022 Due to Immigration. Available online: https://stat.gov.lv/en/statistics-themes/population/population/press-releases/12338-number-population-latvia-2022 (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- PROVIDUS. Immigrant Integration in Latvia: Latvian Language Learning and Civic Education; Centre for Public Policy. 2011. Available online: https://providus.lv/petijumi/imigrantu-integracija-latvija-valsts-valodas-apguve-un-pilsoniska-izglitiba (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Vogel, D.; Triandafyllidou, A. Civic Activation of Immigrants–An Introduction to Conceptual and Theoretical Issues. Available online: https://migrant-integration.ec.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2009-01/docl_6946_222021887.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Li, R.; Jones, B.M. Why Do Immigrants Participate in Politics Less than Native-Born Citizens? A Formative Years Explanation. J. Race Ethn. Politics 2019, 5, 62–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Settling in 2018 Indicators of Immigrant Integration; Paris Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD): Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

| 2016 | 2022 | |

|---|---|---|

| Civic knowledge | 492.2 (3.1) | 490.1 (2.8) |

| Civic knowledge by gender | ||

| Boys | 476.3 (3.7) | 473.8 (3.4) |

| Girls | 506.6 (3.8) | 506.6 (3.2) |

| Civic knowledge by SES | 0.344 * (0.02) | 0.382 * (0.02) |

| Civic knowledge by S_HINT | ||

| Not interested at all | 438.4 (16.9) | 445.8 (6.8) |

| Not very interested | 476.9 (5.4) | 471.9 (3.9) |

| Quite interested | 491.5 (3.6) | 497.5 (3.1) |

| Very interested | 507.8 (3.8) | 507.8 (4.6) |

| Civic knowledge by immigration status | ||

| Native | 494.5 (3.0) | 495.7 (2.7) |

| First Generation Immigrants | 449.2 (22.8) | 443.7 (10.8) |

| Second Generation Immigrants | 482.1 (8.1) | 420.1 (16.3) |

| 2016 | 2022 | |

|---|---|---|

| Pollution | ||

| Not at all | 425.0 (37.0) | 397.7 (15.4) |

| To a small extent | 455.9 (13.0) | 415.7 (9.8) |

| To a moderate extent | 470.8 (5.0) | 460.0 (5.0) |

| To a large extent | 501.4 (2.8) | 503.5 (2.7) |

| Climate change | ||

| Not at all | 447.0 (11.2) | 396.2 (9.8) |

| To a small extent | 475.3 (5.2) | 435.6 (6.2) |

| To a moderate extent | 482.6 (3.6) | 469.4 (3.9) |

| To a large extent | 508.0 (3.6) | 510.4 (2.8) |

| Water shortages | ||

| Not at all | 474.8 (13.6) | 414.8 (8.6) |

| To a small extent | 470.0 (5.9) | 460.0 (6.3) |

| To a moderate extent | 479.9 (5.5) | 468.3 (4.6) |

| To a large extent | 501.6 (3.4) | 508.4 (2.7) |

| Poverty | ||

| Not at all | 477.6 (14.0) | 405.8 (12.9) |

| To a small extent | 490.2 (6.9) | 452.6 (5.8) |

| To a moderate extent | 498.1 (4.0) | 495.3 (3.4) |

| To a large extent | 491.8 (3.6) | 504.3 (2.9) |

| Global financial crises | ||

| Not at all | 451.9 (17.1) | 411.4 (12.0) |

| To a small extent | 487.4 (6.1) | 452.9 (7.5) |

| To a moderate extent | 493.9 (3.8) | 490.2 (3.9) |

| To a large extent | 495.7 (3.7) | 505.7 (2.7) |

| Unemployment | ||

| Not at all | 470.1 (10.4) | 414.8 (12.2) |

| To a small extent | 501.0 (6.0) | 459.4 (6.7) |

| To a moderate extent | 503.0 (3.8) | 501.9 (3.5) |

| To a large extent | 483.0 (3.5) | 499.2 (2.8) |

| Effect | Environmental Sustainability (X) | Economic Sustainability (X) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 2022 | Difference | 2016 | 2022 | Difference | |

| Gender → X (Total) | 0.277 *** | 0.289 *** | 0.012 | 0.332 *** | 0.287 *** | −0.045 |

| Gender → X (Direct) | 0.168 ** | 0.148 *** | −0.020 | 0.345 *** | 0.207 *** | −0.138 |

| Gender → X (Indirect) | 0.110 *** | 0.141 *** | 0.031 * | −0.013 | 0.080 *** | 0.093 *** |

| SES → X (Total) | 0.152 *** | 0.126 *** | −0.026 | −0.111 *** | 0.115 *** | 0.225 *** |

| SES → X (Direct) | 0.048 | −0.031 | −0.079 | −0.098 *** | 0.026 | 0.124 ** |

| SES → X (Indirect) | 0.104 *** | 0.157 *** | 0.053 *** | −0.013 | 0.089 *** | 0.101 *** |

| HINT → X (Total) | 0.103 * | 0.106 * | 0.003 | 0.063 * | 0.054 | −0.009 |

| HINT → X (Direct) | 0.078 | 0.049 | −0.029 | 0.066 * | 0.022 | −0.044 |

| HINT → X (Indirect) | 0.026 * | 0.057 *** | 0.031 * | −0.003 | 0.032 *** | 0.035 *** |

| 1st GEN IMMIG → X (Total) | 0.099 | −0.967 * | −1.065 | 0.197 | −0.898 * | −1.095 * |

| 1st GEN IMMIG → X (Direct) | 0.275 | −0.625 | −0.901 | 0.175 | −0.706 * | −0.881 |

| 1st GEN IMMIG → X (Indirect) | −0.176 | −0.341 * | −0.165 | 0.022 | −0.192 * | −0.214 ** |

| 2nd GEN IMMIG → X (Total) | −0.411 * | −0.507 ** | −0.096 | −0.126 | −0.237 | −0.111 |

| 2nd GEN IMMIG → X (Direct) | −0.370 | −0.258 | 0.112 | −0.131 | −0.097 | 0.034 |

| 2nd GEN IMMIG → X (Indirect) | −0.042 | −0.249 ** | −0.208 ** | 0.005 | −0.141 *** | −0.146 *** |

| Civic Knowledge → X | 0.293 *** | 0.427 *** | 0.134 *** | −0.005 | 0.252 *** | 0.257 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Čekse, I.; Alksnis, R. Global Threats to Sustainability: Evolving Perspectives of Latvian Students (2016–2022). Sustainability 2024, 16, 11126. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162411126

Čekse I, Alksnis R. Global Threats to Sustainability: Evolving Perspectives of Latvian Students (2016–2022). Sustainability. 2024; 16(24):11126. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162411126

Chicago/Turabian StyleČekse, Ireta, and Reinis Alksnis. 2024. "Global Threats to Sustainability: Evolving Perspectives of Latvian Students (2016–2022)" Sustainability 16, no. 24: 11126. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162411126

APA StyleČekse, I., & Alksnis, R. (2024). Global Threats to Sustainability: Evolving Perspectives of Latvian Students (2016–2022). Sustainability, 16(24), 11126. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162411126