Enhancing Supportive and Adaptive Environments for Aging Populations in Jordan: Examining Location Dynamics

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Aging in Place: Home and Neighborhood Environments

2.2. Rural Aging in Place and Place Attachment

2.3. Attachment to Place as Home

2.4. Aging in Place and Control

2.5. Home Modification and Aging in Place

2.6. Aging and Personalization

3. Research Methods

3.1. Sampling and Data Collection

3.2. Research Instruments

3.3. Research Setting and Study Models

3.4. Research Questions and Constructs

3.5. Hypotheses of the Study

3.6. Study Variables and Measures

- Independent Variable—Location. This refers to the location of the sampled governorates. The independent variable is location, which is measured by one of the seven governorates: (1) Irbid, (2) Jerash, (3) Ajloun, (4) Mafraq, (5) Zarqa, (6) Salt, (7) Madaba.

- Dependent Variable 1: Overall Sense of Control—this refers to the ability of elderly individuals to feel that they have control over the physical and social aspects of their lives. The first dependent variable is an overall sense of control, which is measured using two levels: (1) Control 1—Control of opinion (measured using two levels); and (2) Control of activities (measured using two levels).

- Dependent Variable 2: Space Personalization—this variable explains how adaptable the environment is for elderly individuals. It includes the marking of specific places with objects or items that have value to them. The second dependent variable is space personalization, which is measured using five levels: Average of (Managed objects + Freedom of displays + No intrusion to objects + Placement choice + Fixated (cannot be given)).

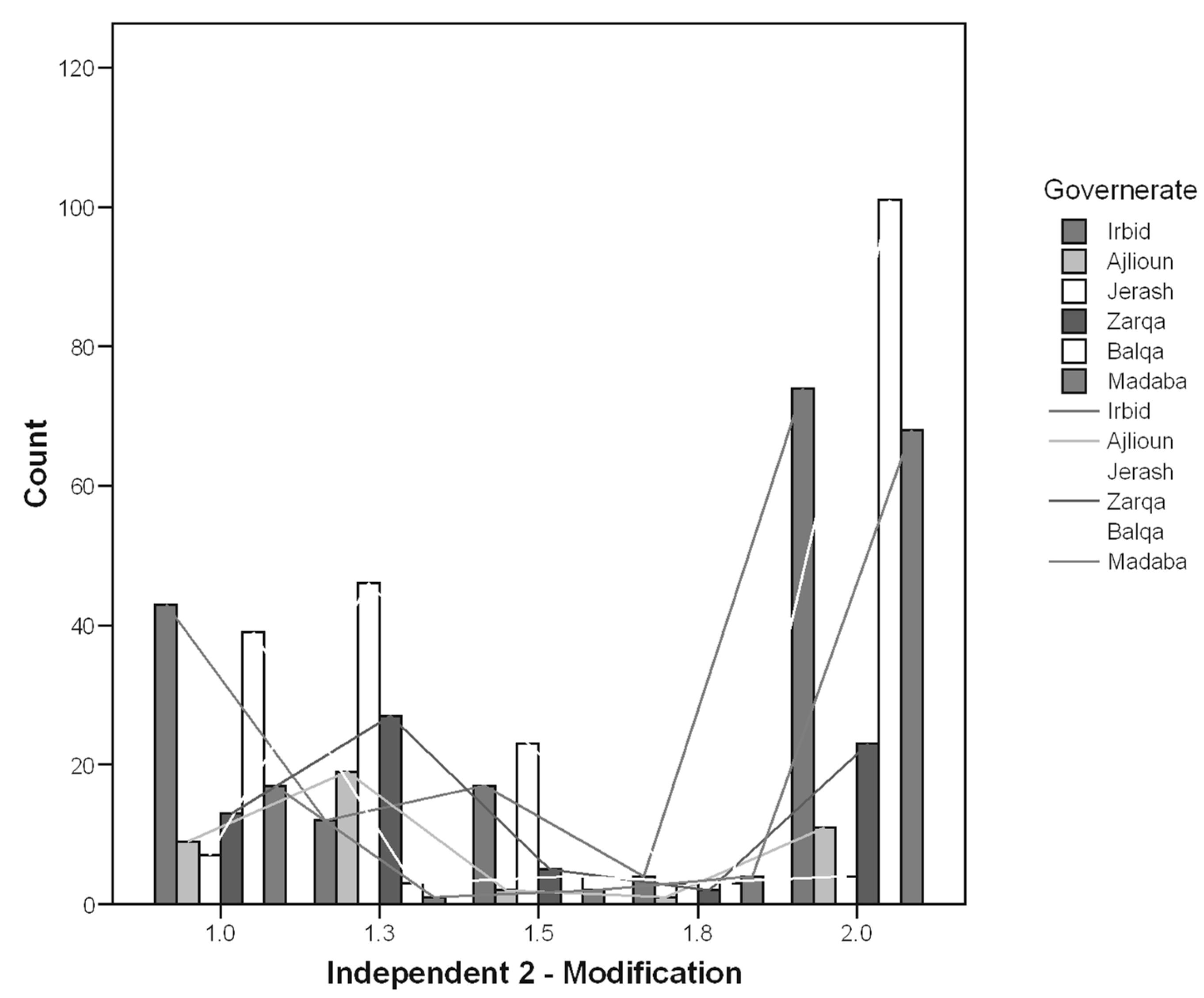

- Dependent Variable 3: This variable explains how supportive the environment is for the elderly individuals in their homes. It includes any modifications or changes that were made to their living space to accommodate their needs. The third dependent variable is home modification, which is measured using four levels: Average of (Modification of kitchen + bedroom + living room + reception room).

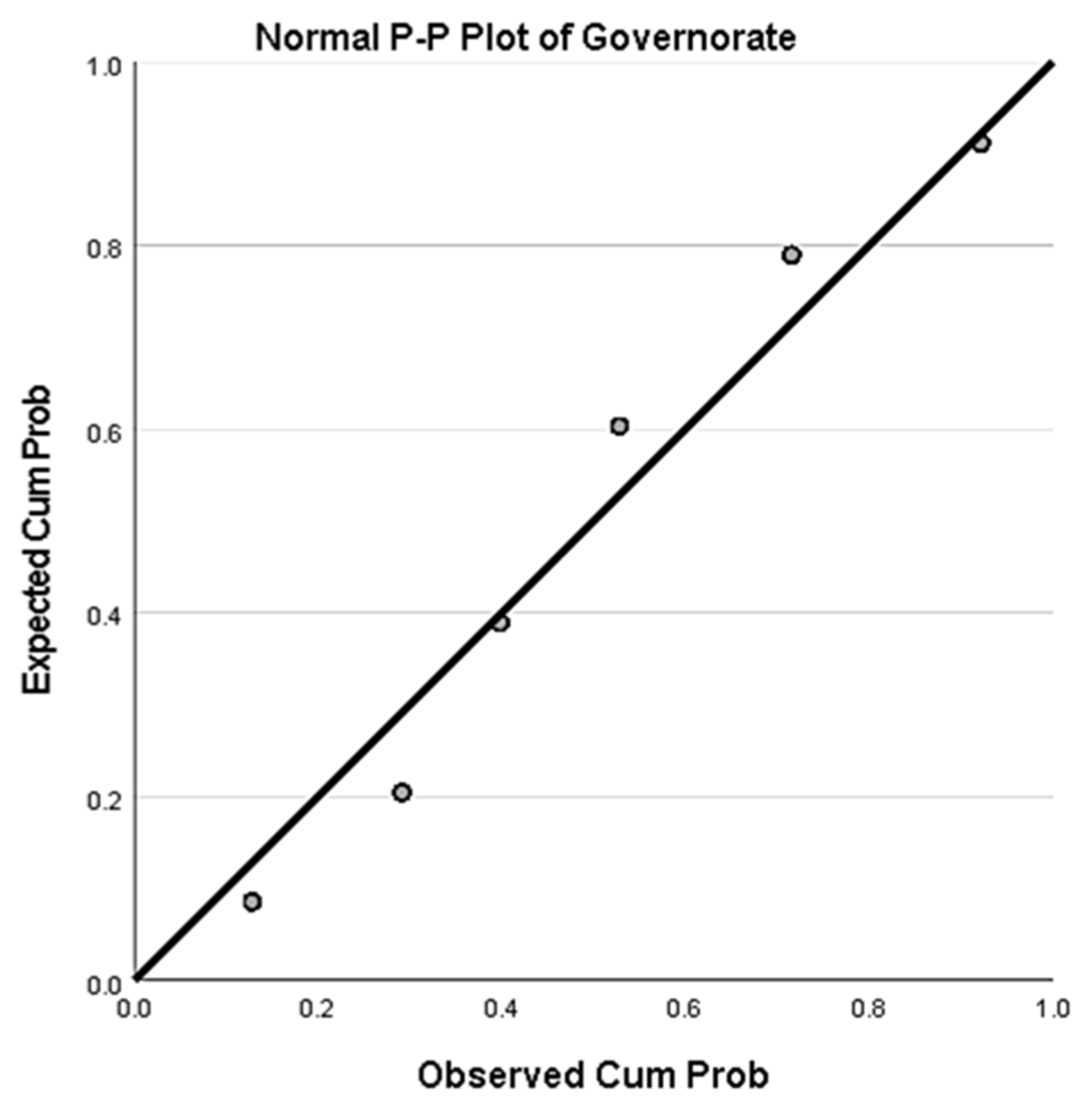

3.7. Anticipated Data Analysis

- Quantitative analysis includes the following steps:

- Data entry and data management using SPSS statistical software version 27.

- Descriptive analysis and Hypothesis testing using ANOVA and Multiple Regression.

- Qualitative analysis includes the following steps:

- Summary of the interviews

- Analysis by extraction of codes: First step: Identifying codes from Individual interviews: This involves reading through the interview transcripts and noting down any specific ideas, concepts, or themes that are discussed). Second step: Collapse codes from interviews.

- Analysis by extraction of themes: First step: Extract themes from Individual interviews. Second step: Collapse themes from Individual interviews.

3.8. Sampling Error and Bias

- Sampling Methodologies:

- Convenient Sampling for Interviews: Convenient sampling was used for selecting the interview participants. The people who happened to be conveniently available shared diverse characteristics.

- Random Sampling for Surveys: The use of random sampling for surveys helped to mitigate sampling bias, as it attempted to ensure that every individual in the target population has an equal chance of being selected.

- Sample Size and Generalizability: The larger sample size for the surveys offers a robust data set.

- Data Collection Instruments: Using both structured and open-ended questionnaires allows for both breadth and depth. These instruments were designed to capture the diverse experiences and views of the senior population. Poorly designed questions can introduce bias if they lead or limit responses.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

4.1.1. Socio-Economic Demographic Characteristics of the Participants

4.1.2. Descriptive Analysis of the Independent Variable—Location

4.1.3. Descriptive Analysis of the Dependent Variables

- Kitchen: M = 1.51, SD = 0.50

- Bedroom: M = 1.57, SD = 0.50

- Living room: M = 1.64, SD = 0.48

- Reception room: M = 1.65, SD = 0.48

4.2. Hypotheses Testing

4.3. Qualitative Analysis

- Theme 1: Rural villages with a hierarchical physical setting, agriculture and livestock as the main livelihood, presence of schools and varying heights of fences.

- Theme 2: Random street layout in towns with services like mosques, health centres, schools, and parks, some areas lacking infrastructure like paved roads, electricity, and entertainment services.

- Theme 3: Different house typologies in the area, from old constructions to modern ones, traditional houses with wells for drinking water, and apartments on top of commercial strips.

- Theme 4: Strong kinship and communal activities in the village, periodic meetings for the elderly, good neighboring relationships, and changes in social structure due to working/studying outside the village.

- Theme 5: Extended family structure, sufficient income for farming and livestock, middle-class income level, inheritance of houses and land, basic furniture, and good health.

- Theme 6: Values include caring for elders, communal living, practicing generosity and religion, and striving to be self-sufficient.

- Theme 7: Individuals have control over various aspects of their lives, with age and health impacting their sense of control, and different levels of control based on family size and age.

- Theme 8: Attachment to village, house, family, community, tools, sentimental objects, cultural significance, and memories.

- Theme 9: House modifications made to accommodate the size of the family.

- Theme 10: Group conflict among individuals aged 20–30.

- Theme 11: Negative situations faced by some elderly individuals, including loneliness, isolation, poverty, and neglect, often due to lack of proper care from busy children and inadequate housing.

- Theme 12: Positive emotions towards the elderly, recognizing their beauty and the importance of cultural traditions in ensuring their well-being.

- These where further collapsed in relation to the adaptation of the elderly to home can be identified:

- Physical Environment and Infrastructure: The physical setting of the villages, including the layout of houses, availability of basic services like electricity and sanitation, and the condition of housing structures, plays a key role in the adaptation of the elderly. Issues such as poorly insulated windows, inadequate bathroom facilities, and cracked walls impact their comfort and safety at home.

- Control and Autonomy: Elderly individuals often value a sense of control and autonomy over their living environment. The level of control they feel over their homes and possessions can affect their overall well-being and satisfaction with their living situation.

- Attachment and Sentimentality: Older individuals may feel a strong attachment to their homes, belongings, and the community they have lived in for many years. The sentimental value attached to their living space can influence their adaptation and feelings of comfort and security.

- Social Support and Community Engagement: The involvement of the elderly in community activities, social gatherings with neighbors, and support from family members can enhance their adaptation to home. Loneliness, isolation, and lack of care from family members were identified as challenges that impact the well-being of older individuals at home.

- Cultural Traditions and Practices: Cultural activities and traditions can contribute to a sense of fulfillment and purpose for elderly individuals living at home. Upholding cultural values such as caring for elders and maintaining social connections within the community can support their adaptation to home and overall quality of life.

- The thematic analysis of the interviews among the older participants revealed new key themes:

- Adaptation and coping strategies: Older individuals adapt to changes in their environment by modifying their homes, seeking support from their community, and finding ways to stay connected with their social network. They also cope with negative situations by maintaining a positive attitude, seeking help when needed, and utilizing their resources effectively.

- Aging in place: The concept of aging in place is important for the older participants, as they value staying in their familiar environment surrounded by their community and family. They make modifications to their homes to ensure they can continue living independently and safely as they age.

- Sense of identity and belonging: Older individuals in the villages have a strong sense of identity tied to their homes, families, and communities. They feel a deep sense of belonging to their surroundings and take pride in their cultural heritage and traditions.

- Importance of intergenerational relationships: The older participants value their relationships with younger generations and see them as a source of support and companionship. They pass down their knowledge and wisdom to the younger members of the community, fostering a sense of continuity and connection between generations.

5. Discussion

5.1. Thematic Discussion

- Sense of Control: The analysis breaks down the perceived control over both personal opinions and activities. Participants express a high sense of control, particularly in managing personal activities. This is crucial for elderly residents who value autonomy and decision-making in their living environments. Designing spaces that enable easy access, mobility, and independence can help maintain this sense of control. Elderly individuals cherish control over their lives, including domestic matters and decision-making processes. The design of living spaces needs to facilitate this control, even as physical abilities might decline with age. Architectural solutions like open floor plans, easily navigable spaces, and adaptable features (e.g., adjustable shelves and lighting) can help sustain this autonomy. Gender differences in control may also necessitate tailored approaches for a design that acknowledges different needs and societal roles.

- Space Personalization: This aspect focuses on the adaptability and customization of living areas. The study highlights that respondents place high importance on managing objects and being able to personalize their environment. For elderly individuals, the ability to personalize their space according to their preferences enhances comfort and psychological well-being. Personal spaces within homes significantly contribute to an individual’s sense of control and belonging. This can be achieved through flexible designs that allow for customization, such as movable partitions, multi-functional furniture, and design elements that enable residents to modify their environment according to personal preferences. This adaptability supports psychological well-being and allows homes to evolve with occupants’ lifestyles and family dynamics.

- Home Modification: The data reflect a modest level of home modifications reported by participants, with the reception room being the most frequently modified space. This suggests that living spaces need to support modifications that cater to the changing needs of elderly residents, such as improved accessibility or safety features. Products like adjustable furniture, wider doorways, and non-slip floors can accommodate these needs. Many older homes may not meet the needs of elderly residents due to poor infrastructure, outdated facilities, and safety hazards. Thus, retrofitting existing homes with modern amenities—like accessible bathrooms, better insulation, and reinforced structures—can significantly enhance comfort and safety. Emphasis should also be placed on preserving cultural and sentimental elements within homes, which strengthen emotional connections and enhance the feeling of belonging.

- Theme 1: Feel of Control and Its Manifestations: Individuals have authority in several ways: they are consulted on many issues; they exert control over family members; they manage the house and its contents; males exert more control than females; those living alone have more control, though living with sons reduces this; private families often have elders in control; smaller families equate to a greater sense of control; assigned private spaces enhance control; control decreases with age and health; individuals aged 60 to 70 generally have substantial control, while those between 70 and 80, 80% experience relative control, and 20% have complete control. Types of control include physical and social control, social and opinion-based control, and some decline the need for control, experiencing no sense of control.

- Theme 2: Attachment in Various Forms: People can be attached to their village, house, family, community, land, farming, and agriculture rather than tools. Gender differences exist, with females generally more attached than males. Objects, especially handmade or culturally significant ones, can carry value. Memories can influence attachment. Health and income can impact perceived control over one’s life.

- Theme 3: Negative Situations: Some elderly individuals experience loneliness, isolation, poverty, neglect, and lack of care. Contributing factors include busy children unable to provide care, and unsuitable housing conditions like poorly insulated windows, inadequate bathroom facilities, and structural issues.

- Theme 4: Cultural Practices: Elders often engage in cultural activities and traditions, providing them with a structured role within society.

5.2. Relevant Home Modifications

- Home Modifications for Suitability: Homes in rural areas have been upgraded over time to better accommodate the size of growing families, addressing some elderly residents’ needs. Despite this, certain houses remain unsuitable for elderly individuals due to inadequate insulation, insufficient bathroom facilities, and structural damage.

- Space Personalization: Elderly residents have personalized their living spaces, converting them into environments that cater to their comfort and well-being. This personalization involves assigning private spaces within homes which contribute significantly to their sense of control and belonging.

- Enhancing Living Conditions: Modifications are made to ensure that the elderly can age in place, maintaining a sense of independence and safety as they live within their familiar environments. This entails adjustments that enhance accessibility and ease of mobility within their homes.

- Addressing Loneliness and Isolation Through Modifications: The study identifies challenges like loneliness and isolation among some elderly, which can be mitigated through home modifications and community engagement. Such changes can foster better social interactions and provide more inviting spaces for family visits.

- Community Support and Engagement: The involvement of the community and support from family through periodic meetings and maintenance of cultural practices are integral to the well-being of the elderly, adding a layer of emotional stability through social connections.

- Cultural Tradition and Attachment: Modifications also respect cultural traditions, enabling the elderly to maintain cultural practices and heritage within their personalized home environments, thus enhancing their attachment to the place.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

- Cultural and Traditional Integration:

- Design living environments that reflect cultural values and traditions, such as community gardens for agriculture to maintain connectivity to land and farming practices.

- Include spaces dedicated to cultural or religious practices that help elders remain connected to their heritage.

- Policy and Regulations:

- Advocate for policies that support community-based elder care, ensuring accessible healthcare and social services.

- Encourage regulatory frameworks that incorporate elder-friendly design into new housing developments and renovations.

- Community-Based Support Systems:

- Establish community centers that provide social activities, health services, and emotional support, to counteract social isolation and loneliness.

- Foster intergenerational programs that encourage interaction between the elderly and younger community members, reinforcing community bonds.

- Environment and Infrastructure Improvements:

- Improve infrastructure to enhance mobility and accessibility, such as better public transport options and pedestrian-friendly pathways.

- Address housing inadequacies by improving insulation, structural integrity, and energy efficiency to ensure comfortable living conditions.

- Health and Safety Enhancements:

- Integrate technology solutions, like emergency response systems and smart home devices, that promote health monitoring and immediate assistance.

- Develop partnerships with local health services to provide regular health check-ups and home visits.

- Home Design and Modification:

- Encourage home modifications that enhance safety and accessibility, such as installing handrails, ramps, and wider doorways.

- Implement age-friendly design elements that improve comfort and usability, particularly in bathrooms and kitchens.

- Personalization of Space:

- Enable personalized spaces within the home that allow older adults to maintain a sense of control and authority, such as dedicated rooms or areas where personal items and mementos can be showcased.

- Support housing designs that allow for adaptability over time, accommodating changing mobility and health needs.

- Research and Development:

- Encourage ongoing research to continue evaluating the effectiveness of implemented solutions and explore innovative strategies to further support the aging population.

- Expand studies to include more regions and diverse populations within Jordan to tailor solutions that address varied needs across different settings.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hussein, S.; Ismail, M. Ageing and elderly care in the Arab region: Policy challenges and opportunities. Ageing Int. 2017, 42, 274–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sibai, A.M.; Yamout, R. Family-based old-age care in Arab countries: Between tradition and modernity. In Population Dynamics in Muslim Countries: Assembling the Jigsaw; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 63–76. [Google Scholar]

- UN. The Sustainable Development Goals Report, 2017. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2017/ (accessed on 21 March 2024).

- Pynoos, J. Meeting the Needs of Older Persons to Age in Place: Findings and Recommendations for Action; Retrieved 28 April 2004; Andrus Gerontology Center, The National Resource Center for Supportive Housing and Home Modification: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Maddox, G.L. Aging Differently. Gerontologist 1987, 27, 557–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- North, M.S.; Fiske, S.T. Modern attitudes toward older adults in the aging world: A cross-cultural meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2015, 141, 993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, L.; Ralston, M. Valued elders or societal burden: Cross-national attitudes toward older adults. Int. Sociol. 2017, 32, 731–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, C.N.; Bayen, U.J. Attitudes toward aging and older adults in Arab culture: A literature review. Z. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2019, 52, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, L.-J.; Imtiaz, F.; Su, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Bowie, A.C.; Chang, B. Culture, Aging, Self-Continuity, and Life Satisfaction. J. Happiness Stud. 2022, 23, 3843–3864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornadt, A.E.; de Paula Couto, C.; Rothermund, K. Views on Aging–Current Trends and Future Directions for Cross-Cultural Research. Online Read. Psychol. Cult. 2022, 6, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vauclair, C.M.; Hanke, K.; Huang, L.L.; Abrams, D. Are Asian cultures really less ageist than Western ones? It depends on the questions asked. Int. J. Psychol. 2017, 52, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fänge, A.; Iwarsson, S. Changes in ADL dependence and aspects of usability following housing adaptation—A longitudinal perspective. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2005, 59, 296–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, K.R. A Home Modifications Program for Older Persons, 2001. Available online: https://archives.joe.org/joe/2001december/iw3.php (accessed on 21 March 2024).

- Park, S.; Park, J.; Jung, M. Trend Analysis of Domestic Studies on Home Modification for Older Adults: Home Modification as a Way of Supporting Aging in Place. Korean J. Occup. Ther. 2020, 28, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Jawad, T. The Proper Modern House. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1982, 324, 64–75. [Google Scholar]

- Touman, I.A.; Al-Ajmi, F.F. Privacy in Arabian architecture: Past and present differential understanding—Part I: Egyptian house designing. Art Des. Rev. 2017, 5, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnaim, M.M. The typology of courtyard space in Najdi Architecture, Saudi Arabia: A response to human needs, culture, and the environment. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2023, 23, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsheshtawy, Y. The Emirati Sha ‘bī house: On transformations, adaptation and modernist imaginaries. Arab. Humanit. Rev. Int. D’archéologie Sci. Soc. Péninsule Arab./Int. J. Archaeol. Soc. Sci. Arab. Penins. 2019, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Remali, A.M.; Salama, A.M.; Wiedmann, F.; Ibrahim, H.G. A chronological exploration of the evolution of housing typologies in Gulf cities. City Territ. Archit. 2016, 3, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Badayneh, D. Tatwir meqyas lel etejahat naho kebar al-sen fe al-mojtama’al-ordony [Development of an attitudes toward elderly scale in the Jordanian society]. Majallat Al-Olom Al-Ejtema’iya 2001, 29, 79–117. [Google Scholar]

- Shoqeirat, M.; Al-Nawaiseh, S. Etejahat al-amelin fe al-qeta’al-sehhy al-hyokomy fe mohafathat Al-Karak naho kebar al-sen wa alaqat thalek beba’d al-motaghayerat al-demografia [Attitudes of health workers at Al-Karak district toward elderly and their relationship to some demographical variables]. Majallat Al-Olom Al-Tarbawiya Wal Nafsiya 2002, 3, 81–124. [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett, H.; Carroll, M. Ageing in place down under. Glob. Ageing: Issues Action 2011, 7, 25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Han, J.H.; Kim, J.-H. Variations in ageing in home and ageing in neighbourhood. Aust. Geogr. 2017, 48, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Hees, S.; Horstman, K.; Jansen, M.; Ruwaard, D. Photovoicing the neighbourhood: Understanding the situated meaning of intangible places for ageing-in-place. Health Place 2017, 48, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiles, J.L.; Leibing, A.; Guberman, N.; Reeve, J.; Allen, R.E. Te meaning of “aging in place” to older people. Gerontologist 2012, 52, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrew, N.; Meeks, S. Fulfilled preferences, perceived control, life satisfaction, and loneliness in elderly long-term care residents. Aging Ment. Health 2018, 22, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhury, H.; Oswald, F. Advancing understanding of person-environment interaction in later life: One step further. J. Aging Stud. 2019, 51, 100821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalinkara, V.; Kapikiran, Ş. Yerinde yaşlanma ölçeğinin geliştirilmesi ve psikometrik özellikleri. Yaşlı Sorunları Araştırma Derg. 2017, 10, 54–66. [Google Scholar]

- Ling, T.-Y.; Lu, H.-T.; Kao, Y.-P.; Chien, S.-C.; Chen, H.-C.; Lin, L.-F. Understanding the Meaningful Places for Aging-in-Place: A Human-Centric Approach toward Inter-Domain Design Criteria Consideration in Taiwan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prattley, J.; Buffel, T.; Marshall, A.; Nazroo, J. Area effects on the level and development of social exclusion in later life. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 246, 112722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenwohl-Mack, A.; Schumacher, K.; Fang, M.-L.; Fukuoka, Y. Experiences of aging in place in the United States: Protocol for a systematic review and meta-ethnography of qualitative studies. Syst. Rev. 2018, 7, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AARP. These four walls. In Americans 45+ Talk About Home and Community; AARP: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Adams-Price, C.; Riaz, M.; Ralston, M.; Gardner, A. Attachment to home and community in older rural African Americans in Mississippi. Innov. Aging 2020, 4 (Suppl. S1), 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, B. Rural place attachment and urban community integration of Chinese older adults in rural-to-urban relocation. Ageing Soc. 2022, 42, 1299–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Feng, L.; Hu, L.; Cao, Y. Older residents’ sense of home and homemaking in rural-urban resettlement: A case study of “moving-merging” community in Shanghai. Habitat Int. 2022, 126, 102616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butcher, E.; Breheny, M. Dependence on place: A source of autonomy in later life for older Māori. J. Aging Stud. 2016, 37, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, M.; Kang, J.; Kwon, H.J. The concept of aging in place as intention. Gerontologist 2020, 60, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martens, C.T. Aging in which place? Connecting aging in place with individual responsibility, housing markets, and the welfare state. J. Hous. Elder. 2018, 32, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, T.; Kearns, R. The role of bluespaces in experiencing place, aging and wellbeing: Insights from Waiheke Island, New Zealand. Health Place 2015, 35, 206–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottoni, C.A.; Sims-Gould, J.; Winters, M.; Heijnen, M.; McKay, H.A. Benches become like porches: Built and social environment influences on older adults’ experiences of mobility and wellbeing. Soc. Sci. Med. 2016, 169, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogelsang, E.M. Older adult social participation and its relationship with health: Rural-urban differences. Health Place 2016, 42, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffel, T.; Phillipson, C.; Scharf, T. Experiences of neighbourhood exclusion and inclusion among older people living in deprived inner-city areas in Belgium and England. Ageing Soc. 2013, 33, 89–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenkmann, A.; Poland, F.; Burns, D.; Hyde, P.; Killett, A. Negotiating and valuing spaces: The discourse of space and ‘home’ in care homes. Health Place 2017, 43, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menec, V.; Means, R.; Keating, N.; Parkhurst, G.; Eales, J. Conceptualising age-friendly communities. Can. J. Aging 2011, 30, 479–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iecovich, E. Aging in place: From theory to practice. Anthropol. Noteb. 2014, 20, 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Carnemolla, P.; Bridge, C. A scoping review of home modification interventions–Mapping the evidence base. Indoor Built Environ. 2020, 29, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, E.O.H.; Endut, E.; Saruwono, M. Personalisation of the Home. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 49, 328–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesthrige, J.W.; Cheung, S.L. Critical evaluation of ‘ageing in place’in redeveloped public rental housing estates in Hong Kong. Ageing Soc. 2020, 40, 2006–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portegijs, E.; Lee, C.; Zhu, X. Activity-friendly environments for active aging: The physical, social, and technology environments. Front. Public Health 2023, 10, 1080148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Steenwinkel, I.; de Casterlé, B.D.; Heylighen, A. How architectural design affords experiences of freedom in residential care for older people. J. Aging Stud. 2017, 41, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnemolla, P.; Bridge, C. Housing design and community care: How home modifications reduce care needs of older people and people with disability. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, L.; Betz-Hamilton, A.; Albright, B.; Lee, S.-J.; Vasquez, K.; Cantrell, R.; Peek, G.; Carswell, A. Home Modification for Older Adults Aging in Place: Evidence from the American Housing Survey. J. Aging Environ. 2022, 38, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchings, B.L.; Olsen, R.V.; Moulton, H.J. Environmental evaluations and modifications to support aging at home with a developmental disability. J. Hous. Elder. 2008, 22, 286–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, E.; Cummings, L.; Sixsmith, A.; Sixsmith, J. Impacts of home modifications on aging-in-place. J. Hous. Elder. 2011, 25, 246–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, B.; Tilse, C.; De Jonge, D. Restoring and sustaining home: The impact of home modifications on the meaning of home for older people. J. Hous. Elder. 2008, 22, 195–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, B.R.; Sanford, J.A.; Long, R.G.; Archea, C.K.; Turner, C.S. Home modifications and performance of routine household activities by individuals with varying levels of mobility impairments. Technol. Disabil. 1993, 2, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schorderet, C.; Ludwig, C.; Wüest, F.; Bastiaenen, C.H.; de Bie, R.A.; Allet, L. eeds, benefits, and issues related to home adaptation: A user-centered case series applying a mixed-methods design. BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thordardottir, B.; Fänge, A.M.; Chiatti, C.; Ekstam, L. Participation in everyday life before and after a housing adaptation. J. Aging Environ. 2020, 34, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, T.; Wiles, J. Being with objects of meaning: Cherished possessions and opportunities to maintain aging in place. Gerontologist 2020, 60, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazhoothundathil, N.; Bailey, A. Cherished possessions, home-making practices and aging in care homes in Kerala, India. Emot. Space Soc. 2020, 36, 100706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, M.Z.; Kahn, D.L.; Steeves, R.H. Hermeneutic Phenomenological Research: A Practical Guide for Nurse Researchers; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Lovatt, M. Relationships and material culture in a residential home for older people. Ageing Soc. 2021, 41, 2953–2970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phenice, L.A.; Griffore, R.J. The importance of object memories for older adults. Educ. Gerontol. 2013, 39, 741–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degnen, C. Socialising place attachment: Place, social memory and embodied affordances. Ageing Soc. 2016, 36, 1645–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, M. Poetry, Language, Thought. By Martin Heidegger. Translated by Albert Hofstadter. New York. Harper and Row, 1971. Pp. 229, $7.95. Dialogue Can. Philos. Rev./Rev. Can. Philos. 1973, 12, 372–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroger, J.; Adair, V. Symbolic meanings of valued personal objects in identity transitions of late adulthood. Identity Int. J. Theory Res. 2008, 8, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCracken, G. Culture and consumption among the elderly: Three research objectives in an emerging field. Ageing Soc. 1987, 7, 203–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, B.R. Reducing inventory: Divestiture of personal possessions. J. Women Aging 1992, 4, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubinstein, R.L. The significance of personal objects to older people. J. Aging Stud. 1987, 1, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wapner, S.; Demick, J.; Redondo, J.P. Cherished possessions and adaptation of older people to nursing homes. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 1990, 31, 219–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krafft, C.; Razzaz, S.; Keo, C.; Assaad, R. The Number and Characteristics of Syrians in Jordan: A Multi-Source Analysis; Economic Research Forum: Giza, Egypt, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Löckenhoff, C.E.; De Fruyt, F.; Terracciano, A.; McCrae, R.R.; De Bolle, M.; Costa, P.T.; Aguilar-Vafaie, M.E.; Ahn, C.-K.; Ahn, H.-N.; Alcalay, L. Perceptions of aging across 26 cultures and their culture-level associates. Psychol. Aging 2009, 24, 941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taani, I. Analysis of the Health Situation of the Elderly in the City of Irbid; Jordan University of Science and Technology: Ar-Ramtha, Jordan, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bongaarts, J.; Zimmer, Z. Living Arrangements of Older Adults in the Developing World: An Analysis of DHS Household Surveys [Arabic]; Population Council: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- van Melik, R.; Pijpers, R. Older people’s self–selected spaces of encounter in urban aging environments in the Netherlands. City Community 2017, 16, 284–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, L.; Mirza, R.M.; Austen, A.; Hsieh, J.; Klinger, C.A.; Kuah, M.; Liu, A.; McDonald, L.; Mohsin, R.; Pang, C. More than just a room: A scoping review of the impact of homesharing for older adults. Innov. Aging 2020, 4, igaa011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, S.; Nayyar, P. Crowding effects of density and personal space requirements among older people: The impact of self-control and social support. J. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 140, 721–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trierweiler, R. Personal space and its effects on an elderly individual in a long-term care institution. J. Gerontol. Nurs. 1978, 4, 21–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, M.A. Personal Space: Considerations for the older adult. Educ. Horiz. 1978, 56, 192–195. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.; Lee, M.J.; Kang, J. Exploring Differences in Home Modification Strategies According to Household Location and Occupant Disability Status: 2019 American Housing Survey Analysis. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2023, 43, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, H.Y.; MacLachlan, M.; Clarke, M.; Mannan, H. Accessible home environments for people with functional limitations: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Demographics | Percent |

|---|---|

| Governorate | |

| Irbid | 25.6% |

| Ajloun | 7.2% |

| Jerash | 14.1% |

| Zarqa | 11.9% |

| Balqa | 25.6% |

| Madaba | 15.7% |

| Gender | |

| Male | 53% |

| Female | 47% |

| Age | |

| >90 Years | 4.4% |

| >80–90 Years | 10.4% |

| >70–80 Years | 35.4% |

| >60–70 Years | 49.7% |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 0.9% |

| Married | 65.4% |

| Divorced | 0.9% |

| Widowed | 32.9% |

| Assigned private room | |

| No | 21.5% |

| Yes | 78.5% |

| Ownership | |

| Charity | 6.8% |

| Owned | 87.6% |

| Rented | 5.7% |

| Length of residence | |

| <10 | 17.30% |

| >10–20 | 20.00% |

| >20–30 | 22.50% |

| >40 | 40.20% |

| Number of family members at home | |

| None | 9.20% |

| 1–5 | 56.50% |

| >5–10 | 28.60% |

| >10 | 5.70% |

| Number of rooms | |

| 1–4 | 72.50% |

| >4 | 27.50% |

| Dependent Variables | N | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Std. Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent 1—Overall sense of control | 587 | 1.0 | 6.0 | 4.08 | 1.10 |

| Control 1 (Control of opinion) | 587 | 1.0 | 6.0 | 4.31 | 0.86 |

| Control 1 (Control of opinion)—Consulted on general issues | 587 | 1 | 6 | 4.21 | 1.05 |

| Control 1 (Control of opinion)—Consulted on my issues | 587 | 1 | 6 | 4.42 | 0.88 |

| Control 2 (Control of activities) | 587 | 1.0 | 6.0 | 4.32 | 0.90 |

| Dependent 2—Personalization | 587 | 1.0 | 6.0 | 4.47 | 0.98 |

| Personalization 1—Managed objects | 587 | 1 | 6 | 4.57 | 1.08 |

| Personalization 2—Freedom of display | 587 | 1 | 6 | 4.56 | 1.07 |

| Personalization 3—No intrusion into objects | 587 | 1 | 6 | 4.34 | 1.30 |

| Personalization 4—Placement choice | 587 | 1 | 6 | 4.40 | 1.26 |

| Personalization 5—Fixated (Cannot be given) | 587 | 1 | 6 | 4.50 | 1.24 |

| Dependent 3—Home modification | 587 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 1.592 | 0.42 |

| Modification of kitchen | 587 | 1 | 2 | 1.51 | 0.50 |

| Modification of bedroom | 587 | 1 | 2 | 1.57 | 0.50 |

| Modification of living room | 587 | 1 | 2 | 1.64 | 0.48 |

| Modification of reception room | 587 | 1 | 2 | 1.65 | 0.48 |

| Governorate | Statistics | Dependent—Overall Sense of Control |

|---|---|---|

| Irbid | Mean | 4.55 |

| N | 150 | |

| Std. Deviation | 0.86 | |

| Ajloun | Mean | 3.62 |

| N | 42 | |

| Std. Deviation | 0.96 | |

| Jerash | Mean | 3.95 |

| N | 83 | |

| Std. Deviation | 0.88 | |

| Zarqa | Mean | 3.33 |

| N | 70 | |

| Std. Deviation | 1.02 | |

| Balqa | Mean | 3.99 |

| N | 150 | |

| Std. Deviation | 1.25 | |

| Madaba | Mean | 4.36 |

| N | 92 | |

| Std. Deviation | 1.02 | |

| Total | Mean | 4.08 |

| N | 587 | |

| Std. Deviation | 1.10 |

| Sum of Squares | Df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The overall sense of control Governorate | Between groups | (Combined) | 91.87 | 5 | 18.37 | 17.41 | 0.00 |

| Linearity | 8.05 | 1 | 8.05 | 7.63 | 0.00 | ||

| Deviation from linearity | 83.82 | 4 | 20.96 | 19.85 | 0.00 | ||

| Within groups | 613.37 | 581 | 1.06 | ||||

| Total | 705.24 | 586 | |||||

| Dependent Variable | (I) Govern | (J) Govern | Mean Difference (I-J) | Std. Error | Sig. | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The overall sense of control | Irbid | Ajloun | 0.93 | 0.18 | 0.00 | 0.34 | 1.53 |

| Jerash | 0.60 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.13 | 1.07 | ||

| Zarqa | 1.23 | 0.15 | 0.00 | 0.73 | 1.72 | ||

| Balqa | 0.57 | 0.12 | 0.00 | 0.17 | 0.96 | ||

| Madaba | 0.20 | 0.14 | 0.84 | –0.26 | 0.65 | ||

| Ajloun | Irbid | –0.93 | 0.18 | 0.00 | –1.53 | –0.34 | |

| Jerash | –0.33 | 0.20 | 0.71 | –0.982 | 0.32 | ||

| Zarqa | 0.29 | 0.20 | 0.84 | –0.38 | 0.96 | ||

| Balqa | –0.37 | 0.18 | 0.52 | –0.97 | 0.23 | ||

| Madaba | –0.74 | 0.19 | 0.01 | –1.38 | –0.10 | ||

| Jerash | Irbid | –0.60 | 0.14 | 0.00 | –1.07 | –0.13 | |

| Ajloun | 0.33 | 0.19 | 0.71 | –0.32 | 0.98 | ||

| Zarqa | 0.62 | 0.17 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 1.18 | ||

| Balqa | –0.03 | 0.14 | 1.00 | –0.50 | 0.43 | ||

| Madaba | –0.41 | 0.16 | 0.23 | –0.93 | 0.11 | ||

| Zarqa | Irbid | –1.22 | 0.15 | 0.00 | –1.72 | –0.73 | |

| Ajloun | –0.29 | 0.20 | 0.84 | –0.96 | 0.38 | ||

| Jerash | –0.62 | 0.17 | 0.02 | –1.18 | –0.07 | ||

| Balqa | –0.66 | 0.15 | 0.00 | –1.16 | –0.16 | ||

| Madaba | –1.03 | 0.16 | 0.00 | –1.57 | –0.49 | ||

| Balqa | Irbid | –0.57 | 0.12 | 0.00 | –0.96 | –0.17 | |

| Ajloun | 0.37 | 0.18 | 0.52 | –0.23 | 0.97 | ||

| Jerash | 0.04 | 0.14 | 1.00 | –0.43 | 0.50 | ||

| Zarqa | 0.66 | 0.15 | 0.00 | 0.16 | 1.16 | ||

| Madaba | –0.37 | 0.14 | 0.19 | –0.83 | 0.08 | ||

| Madaba | Irbid | –0.20 | 0.14 | 0.84 | –0.65 | 0.26 | |

| Ajloun | 0.74 | 0.19 | 0.01 | 0.10 | 1.38 | ||

| Jerash | 0.41 | 0.16 | 0.23 | –0.11 | 0.93 | ||

| Zarqa | 1.03 | 0.16 | 0.00 | 0.49 | 1.57 | ||

| Balqa | 0.37 | 0.14 | 0.19 | –0.08 | 0.83 | ||

| Governorate | Statistics | Independent 1—Personalization |

|---|---|---|

| Irbid | Mean | 5.14 |

| N | 150 | |

| Std. Deviation | 0.74 | |

| Ajloun | Mean | 3.98 |

| N | 42 | |

| Std. Deviation | 0.76 | |

| Jerash | Mean | 4.22 |

| N | 83 | |

| Std. Deviation | 0.76 | |

| Zarqa | Mean | 3.95 |

| N | 70 | |

| Std. Deviation | 0.96 | |

| Balqa | Mean | 4.24 |

| N | 150 | |

| Std. Deviation | 0.84 | |

| Madaba | Mean | 4.63 |

| N | 92 | |

| Std. Deviation | 1.21 | |

| Total | Mean | 4.47 |

| N | 587 | |

| Std. Deviation | 0.98 |

| Sum of Squares | Df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Governorates Personalization | Between groups | (Combined) | 110.61 | 5 | 22.12 | 28.34 | 0.00 |

| Linearity | 29.29 | 1 | 29.29 | 37.53 | 0.00 | ||

| Deviation from linearity | 81.31 | 4 | 20.33 | 26.04 | 0.00 | ||

| Within groups | 453.52 | 581 | 0.781 | ||||

| Total | 564.12 | 586 | |||||

| Dependent Variable | (I) Govern | (J) Govern | Mean Difference (I-J) | Std. Error | Sig. | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personalisation | Irbid | Ajloun | 1.16 | 0.15 | 0.00 | 0.64 | 1.67 |

| Jerash | 0.91 | 0.12 | 0.00 | 0.51 | 1.31 | ||

| Zarqa | 1.19 | 0.13 | 0.00 | 0.76 | 1.61 | ||

| Balqa | 0.89 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.55 | 1.23 | ||

| Madaba | 0.51 | 0.12 | 0.00 | 0.12 | 0.90 | ||

| Ajloun | Irbid | –1.16 | 0.15 | 0.00 | –1.67 | –0.64 | |

| Jerash | –0.25 | 0.17 | 0.82 | –0.81 | 0.31 | ||

| Zarqa | 0.03 | 0.17 | 1.00 | –0.55 | 0.60 | ||

| Balqa | –0.27 | 0.15 | 0.70 | –0.78 | 0.25 | ||

| Madaba | –0.65 | 0.17 | 0.01 | –1.20 | –0.10 | ||

| Jerash | Irbid | –0.91 | 0.12 | 0.00 | –1.31 | –0.51 | |

| Ajloun | 0.25 | 0.17 | 0.82 | –0.31 | 0.81 | ||

| Zarqa | 0.28 | 0.14 | 0.60 | –0.20 | 0.75 | ||

| Balqa | –0.02 | 0.12 | 1.00 | –0.42 | 0.39 | ||

| Madaba | –0.40 | 0.13 | 0.11 | –0.85 | 0.04 | ||

| Zarqa | Irbid | –1.19 | 0.13 | 0.00 | –1.61 | –0.76 | |

| Ajloun | –0.03 | 0.17 | 1.00 | –0.60 | 0.55 | ||

| Jerash | –0.28 | 0.14 | 0.60 | –0.75 | 0.20 | ||

| Balqa | –0.29 | 0.13 | 0.38 | –0.72 | 0.13 | ||

| Madaba | –0.68 | 0.14 | 0.00 | –1.15 | –0.21 | ||

| Balqa | Irbid | –0.89 | 0.10 | 0.00 | –1.23 | –0.55 | |

| Ajloun | 0.27 | 0.15 | 0.70 | –0.25 | 0.78 | ||

| Jerash | 0.02 | 0.12 | 1.00 | –0.39 | 0.42 | ||

| Zarqa | 0.29 | 0.13 | 0.38 | –0.13 | 0.72 | ||

| Madaba | –0.39 | 0.12 | 0.06 | –0.78 | 0.01 | ||

| Madaba | Irbid | –0.51 | 0.11 | 0.00 | –0.90 | –0.12 | |

| Ajloun | 0.65 | 0.17 | 0.01 | 0.10 | 1.20 | ||

| Jerash | 0.40 | 0.13 | 0.11 | –0.04 | 0.85 | ||

| Zarqa | 0.68 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.21 | 1.15 | ||

| Balqa | 0.39 | 0.12 | 0.06 | –0.01 | 0.78 | ||

| Tests | Value | Df | Asymp. Sig. (2-Sided) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pearson Chi-square | 262.97 | 20 | 0.00 |

| Likelihood Ratio | 274.19 | 20 | 0.00 |

| Linear-by-Linear association | 21.85 | 1 | 0.00 |

| N of Valid Cases | 587 |

| Multiple R | Sign. |

|---|---|

| R Square | 0.01 |

| Adjusted R Square | 0.01 |

| Std. The error in the Estimate | 1.00 |

| Sum of Squares | Df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression | 8.05 | 1 | 8.05 | 7.91 | 0.01 |

| Residual | 595.74 | 585 | 1.02 | ||

| Total | 603.79 | 586 |

| Unstandardized Coefficients | Beta | T | Sig. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. Error | B | Std. Error | B | |

| (Constant) | 1.73 | 0.84 | 2.08 | 0.04 | |

| Independent 1—Personalization | 0.52 | 0.19 | 0.47 | 2.81 | 0.01 |

| Multiple R | 0.08 |

|---|---|

| R2 | 0.01 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.01 |

| Std. Error of the estimate | 1.41 |

| Sum of Squares | Df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression | 8.05 | 1 | 8.05 | 4.04 | 0.05 |

| Residual | 1166.76 | 585 | 1.99 | ||

| Total | 1174.81 | 586 |

| Unstandardized Coefficients | Beta | T | Sig. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. Error | B | Std. Error | B | |

| (Constant) | 6.36 | 1.14 | 5.60 | 0.00 | |

| Independent 2—Modification | –1.43 | 0.71 | –0.55 | –2.01 | 0.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al-Homoud, M. Enhancing Supportive and Adaptive Environments for Aging Populations in Jordan: Examining Location Dynamics. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10978. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162410978

Al-Homoud M. Enhancing Supportive and Adaptive Environments for Aging Populations in Jordan: Examining Location Dynamics. Sustainability. 2024; 16(24):10978. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162410978

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl-Homoud, Majd. 2024. "Enhancing Supportive and Adaptive Environments for Aging Populations in Jordan: Examining Location Dynamics" Sustainability 16, no. 24: 10978. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162410978

APA StyleAl-Homoud, M. (2024). Enhancing Supportive and Adaptive Environments for Aging Populations in Jordan: Examining Location Dynamics. Sustainability, 16(24), 10978. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162410978