The Concept of Utilizing Waste Generated During the Production of Crispbread for the Production of Corn-Based Snacks

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Snack Preparation

2.2. Moisture Content and Water Activity

2.3. Density and Porosity

2.4. Expansion Index

2.5. Water Solubility Index (WSI) and Water Adsorption Index (WAI)

2.6. Moisture Sorption Properties

2.7. Texture Evaluation

2.8. Sensory Evaluation

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Water Activity

3.2. WAI and WSI

3.3. Sorption Properties

3.4. Density and Porosity

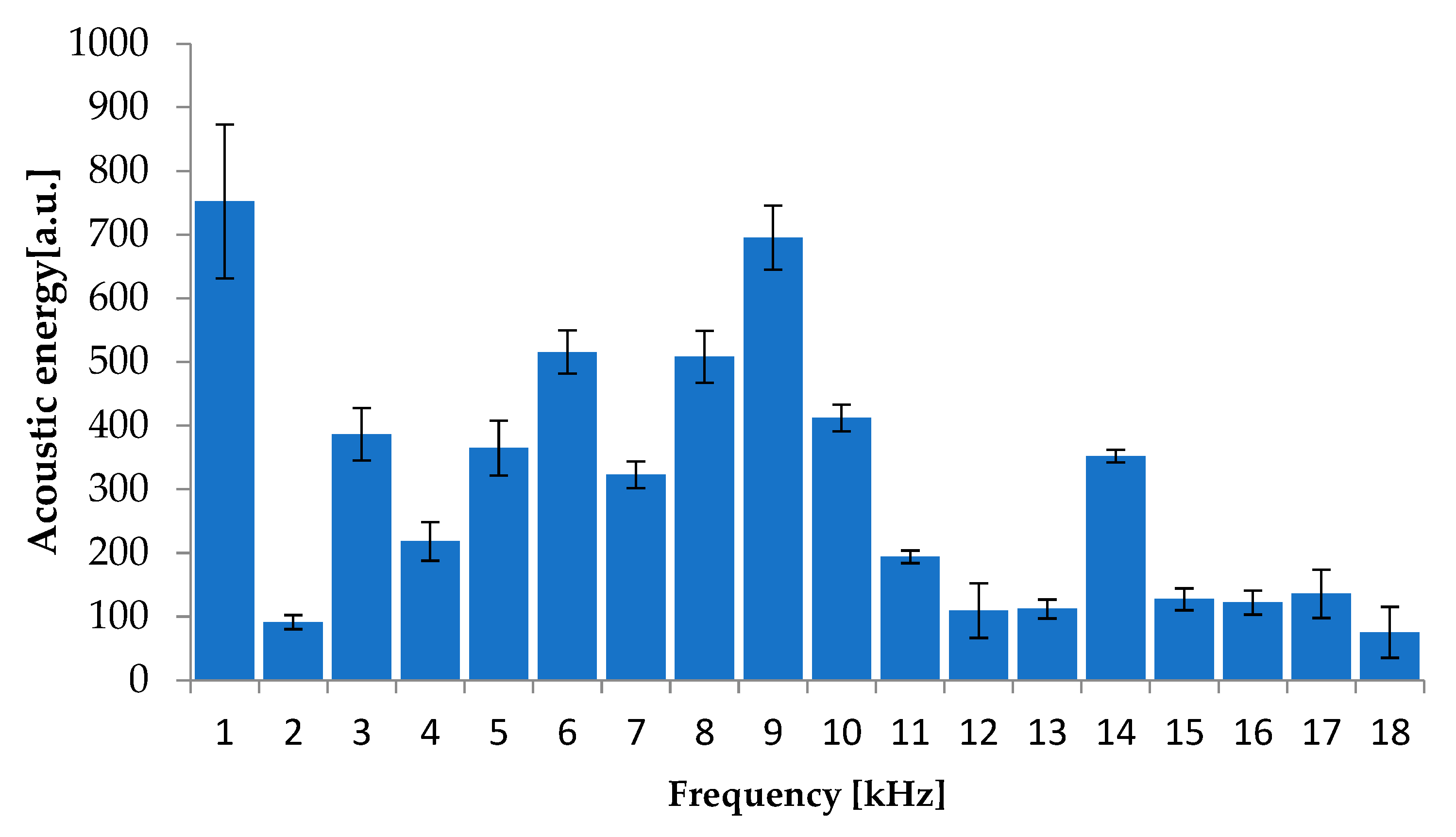

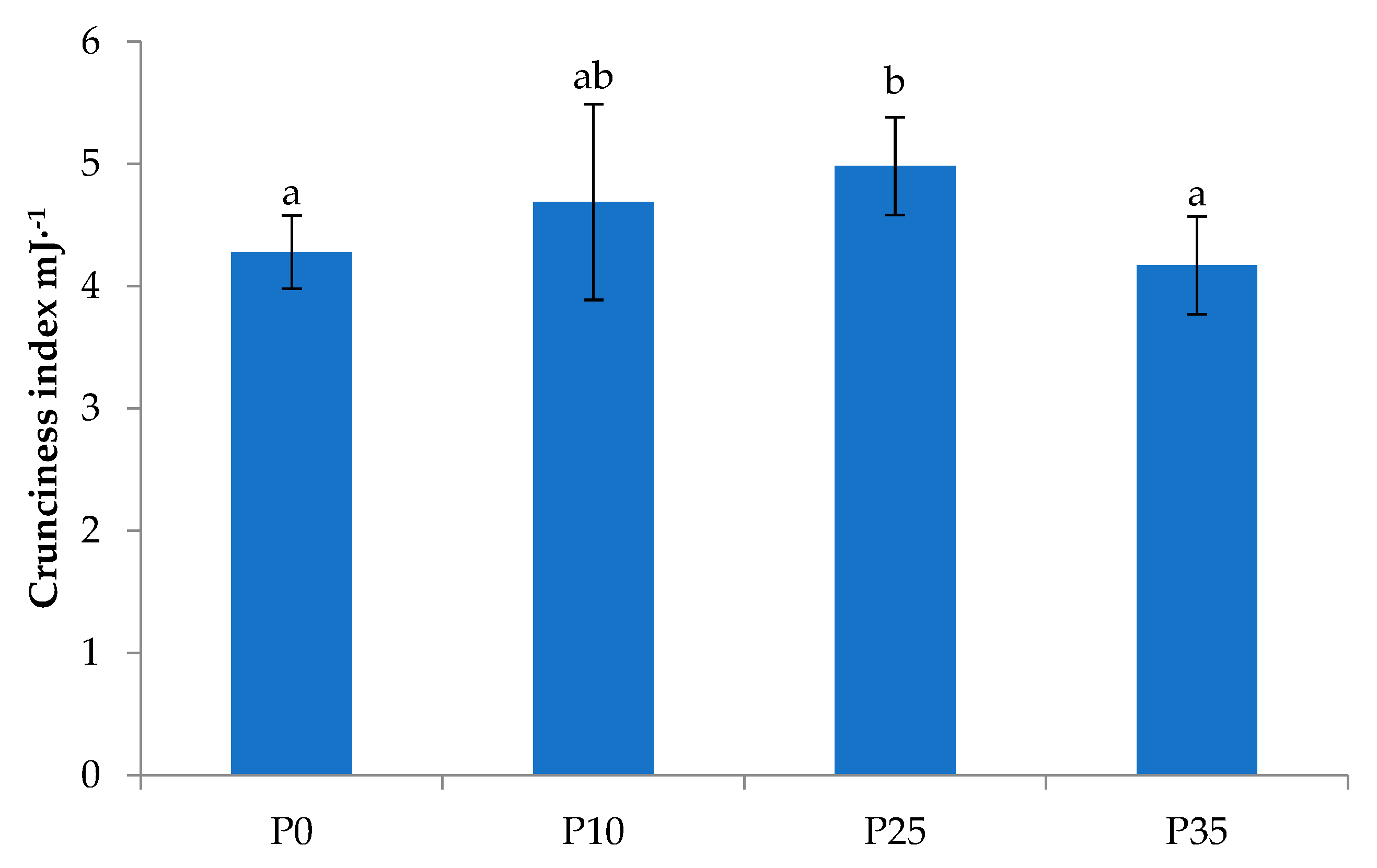

3.5. Texture Properties

3.6. Sensory Properties

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gu, B.J.; Kowalski, R.J.; Ganjyal, G.; Bordoloi, R.; Ganguly, S. Extrusion technique in food processing and a review on its various technological parameters. Indian J. Sci. Res. Technol. 2014, 2, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Kazemzadeh, M. Chapter 1: Introduction to extrusion technology. In Advances in Food Extrusion Technology; Contemporary Food Engineering Series; Maskan, M., Altan, A., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014; Volume 13, pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mironeasa, S.; Coţovanu, I.; Mironeasa, C.; Ungureanu-Iuga, M. A Review of the Changes Produced by Extrusion Cooking on the Bioactive Compounds from Vegetal Sources. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, C.; Brennan, M.; Derbyshire, E.; Tiwari, B.K. Effects of extrusion on the polyphenols, vitamins and antioxidant activity of foods. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 22, 570–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boczula, M.; Wójtowicz, A.; Piszcz, M.; Soja, J.; Lewko, P.; Ignaciuk, S.; Milanowski, M.; Kupryaniuk, K.; Kasprzak-Drozd, K. Corn-Based Gluten-Free Snacks Supplemented with Various Dried Fruits: Characteristics of Physical Properties and Effect of Variables. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 10678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghan-Shoar, Z.; Hardacre, A.K.; Brennan, C.S. The physico-chemical characteristics of extruded snacks enriched with tomato lycopene. Food Chem. 2010, 123, 1117–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, N.P.; Roman, L.; Shiva Swaraj, V.J.; Ragavan, K.V.; Simsek, S.; Rahimi, J.; Kroetsch, B.; Martinez, M.M. Enhancing the nutritional value of cold-pressed oilseed cakes through extrusion cooking. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2022, 77, 102956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasso, S. Extruded snacks from industrial by-products: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 99, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ek, P.; Ganjyal, G.M. Chapter 1: Basics of extrusion processing. In Extrusion Cooking: Cereals and Grains Processing; Ganjyal, G.M., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Dey, D.; Richter, J.K.; Ek, P.; Gu, B.-J.; Ganjyal, G.M. Utilization of Food Processing By-products in Extrusion Processing: A Review. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 4, 603751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Gu, B.-J.; Ganjyal, G.M. Impacts of the inclusion of various fruit pomace types on the expansion of corn starch extrudates. LWT 2019, 110, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figuerola, F.; Hurtado, M.L.; Estévez, A.M.; Chiffelle, I.; Asenjo, F. Fibre concentrates from apple pomace and citrus peel as potential fibre sources for food enrichment. Food Chem. 2005, 91, 395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkerd, S.; Wanlapa, S.; Puttanlek, C.; Uttapap, D.; Rungsardthong, V. Expansion and functional properties of extruded snacks enriched with nutrition sources from food processing by-products. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 53, 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grigelmo-Miguel, N.; Martin-Belloso, O. Comparison of dietary fibre from by-products of processing fruits and greens and from cereals. Food Sci. Technol. 1999, 32, 503–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Alves, P.L.; Berrios, J.D.J.; Pan, J.; Ascheri, J.L.R. Passion fruit shell flour and rice blends processed into fiber-rich expanded extrudates. CyTA J. Food 2018, 16, 901–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selani, M.M.; Brazaca, S.G.C.; dos Santos Dias, C.T.; Ratnayake, W.S.; Flores, R.A.; Bianchini, A. Characterisation and potential application of pineapple pomace in an extruded product for fibre enhancement. Food Chem. 2014, 163, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaisangsri, N.; Kowalski, R.J.; Wijesekara, I.; Kerdchoechuen, O.; Laohakunjit, N.; Ganjyal, G.M. Carrot pomace enhances the expansion and nutritional quality of corn starch extrudates. LWT 2016, 68, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altan, A.; McCarthy, K.L.; Maskan, M. Evaluation of snack foods from barley-tomato pomace blends by extrusion processing. J. Food Eng. 2008, 84, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasimowski, E.; Grochowicz, M.; Szajnecki, Ł. Preparation and Spectroscopic, Thermal, and Mechanical Characterization of Biocomposites of Poly(butylene succinate) and Onion Peels or Durum Wheat Bran. Materials 2023, 16, 6799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ying, D.; Hlaing, M.M.; Lerisson, J.; Pitts, K.; Cheng, L.; Sanguansri, L.; Augustin, M.A. Physical properties and FTIR analysis of rice-oat flour and maize-oat flour based extruded food products containing olive pomace. Food Res. Int. 2017, 100, 665–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luithui, Y.; Baghya Nisha, R.; Meera, M.S. Cereal by-products as an important functional ingredient: Effect of processing. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 56, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarzycki, P.; Sykut-Domanska, E.; Sobota, A.; Teterycz, D.; Krawecka, A.; Blicharz-Kania, A.; Andrejko, D.; Zdybel, B. Flaxseed enriched pasta-chemical composition and cooking quality. Foods 2020, 9, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Bai, X.; Zhang, Z. Extrusion process improves the functionality of soluble dietary fiber in oat bran. J. Cereal Sci. 2011, 54, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktas-Akyildiz, E.; Masatcioglu, M.T.; Köksel, H. Effect of extrusion treatment on enzymatic hydrolysis of wheat bran. J. Cereal Sci. 2020, 93, 102941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schanes, K.; Dobernig, K.; Gözet, B. Food waste matters-A systematic review of household food waste practices and their policy implications. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 182, 978–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dymchenko, A.; Geršl, M.; Gregor, T. Trends in bread waste utilisation. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 132, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samray, M.N.; Masatcioglu, T.M.; Koksel, H. Bread crumbs extrudates: A new approach for reducing bread waste. J. Cereal Sci. 2019, 85, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PN EN ISO 6540:2010; Maize—Determination of Moisture Content (On Milled Grains And On Whole Grains). Polish Committee for Standardization: Warsaw, Poland, 2010.

- Anderson, R.A.; Conway, H.F.; Peplinski, A.K. Gelatinization of corn grits by roll cooking, extrusion cooking and steaming. Starch 1970, 22, 130–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gondek, E.; Lewicki, P.P. Kinetics of water vapour sorption by selected ingredients of muesli-type mixtures. Pol. J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2007, 57, 23–26. [Google Scholar]

- Gondek, E.; Lewicki, P.P.; Ranachowski, Z. Influence of water activity on the acoustic properties of breakfast cereals. J. Texture Stud. 2009, 37, 497–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewicki, P.P.; Marzec, A.; Kuropatwa, M. Influence of water activity on texture of corn flakes. Acta Agrophysica 2007, 9, 79–90. [Google Scholar]

- Lewicki, P.P. Water as the determinant of food engineering properties. A review. J. Food Eng. 2002, 61, 483–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubczyk, E.; Linde, M.; Gondek, E.; Kamińska-Dwórznicka, A.; Samborska, K.; Antoniuk, A. The effect of phytosterols addition on the textural properties of extruded crisp bread. J. Food Eng. 2015, 167, 156–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gondek, E.; Lewicki, P.P. Antiplasticization of cereal-based products by water. Part II: Breakfast cereals. J. Food Eng. 2006, 77, 644–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gondek, E.; Jakubczyk, E.; Herremans, E.; Verlinden, B.; Hertog, B.; Vandendriessche, T.; Verboven, P.; Antoniuk, A.; Bongaers, E.; Estrade, P.; et al. Acoustic, mechanical and microstructural properties of extruded crisp bread. J. Cereal Sci. 2013, 58, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanvrier, H.; Jakubczyk, E.; Gondek, E.; Gumy, J.C. Insights into the texture of extruded cereals: Structure and acoustic properties. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2014, 24, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubczyk, E.; Gondek, E.; Tryzno, E. Application of novel acoustic measurement techniques for texture analysis of co-extruded snacks. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 75, 582–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaworska, D.; Mojska, H.; Gielecińska, I.; Najman, K.; Gondek, E.; Przybylski, W.; Krzyczkowska, P. The effect of vegetable and spice addition on the acrylamide content and antioxidant activity of innovative cereal products. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2019, 36, 374–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouvier, J.M.; Campanella, O.H. Extrusion Processing Technology: Food and Non-Food Biomaterials; Wiley Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oikonomou, N.A.; Krokida, M.K. Literature Data Compilation of WAI and WSI of Extrudate Food Products. Int. J. Food Prop. 2011, 14, 199–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisharat, G.; Katsavou, I.; Panagiotou, N.; Krokida, M.; Maroulis, Z. Investigation of functional properties and color changes of corn extrudates enriched with broccoli or olive paste. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 2015, 21, 613–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jafari, M.; Koocheki, A.; Milani, E. Effect of extrusion cooking on chemical structure, morphology, crystallinity and thermal properties of sorghum flour extrudates. J. Cereal Sci. 2017, 75, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wójtowicz, A.; Kolasa, A.; Mościcki, L. The influence of buckwheat addition on physicalproperties, texture and sensory characteristic of extruded corn snacks. Pol. J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2013, 63, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wójtowicz, A.; Oniszczuk, A.; Oniszczuk, T.; Kocira, S.; Wojtunik, K.; Mitrus, M.; Kocira, A.; Widelski, J.; Skalicka-Woźniak, K. Application of Moldavian dragonhead (Dracocephalum moldavica L.) leaves addition as a functional component of nutritionally valuable cornsnacks. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 54, 3218–3229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crank, J. The Mathematics of Diffusion, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: London, UK, 1975; pp. 69–88. [Google Scholar]

- Roudaut, G.; Dacremont, C.; Pamies, B.V.; Colas, B.; Le Meste, M. Crispness: A critical review on sensory and material science approaches. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2002, 13, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeleaw, M.; Schleining, G. A review. Crispness in dry foods and quality measurements based on acoustic-mechanical destructive techniques. J. Food Eng. 2011, 105, 387–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Probe ID | Water Content [%] | Water Activity | WSI [%] | WAI [%] | Expansion Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P0 | 5.84 ± 0.04 a | 0.347 ± 0.004 a | 32.79 ± 2.08 a | 7.41 ± 0.45 a | 5.23 ± 0.25 a |

| P10 | 5.77 ± 0.09 ab | 0.322± 0.002 a | 32.12 ± 2.88 a | 6.89 ± 0.25 ab | 4.92 ± 0.41 ab |

| P25 | 5.75 ± 0.09 ab | 0.309 ± 0.006 a | 31.87 ± 2.94 a | 6.56 ± 0.30 bc | 5.01 ± 0.37 ab |

| P35 | 5.65 ± 0.07 b | 0.313 ± 0.001 a | 31.44 ± 2.80 a | 5.93 ± 0.36 c | 4.78 ± 0.36 b |

| Constant | P0 | P10 | P25 | P35 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ue | 24.7 a | 22.8 b | 21.5 b | 18.99 c |

| Deff | 4.49 × 10−9 a | 4.34 × 10−9 ab | 4.06 × 10−9 b | 4.33 × 10−9 ab |

| R2 | 0.97 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.98 |

| χ2 | 3.12 × 10−3 | 4.74 × 10−4 | 1.02 × 10−4 | 1.11 × 10−3 |

| RMS | 4.99 | 2.96 | 2.11 | 3.29 |

| Descriptor | P0 | P10 | P25 | P35 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fmax, N | 15.12 ± 3.12 a | 16.45 ± 2.28 ab | 17.12 ± 4.12 ab | 19.6 ± 4.17 b |

| Number of force peaks | 12.23 ± 5.19 a | 15.63 ± 3.67 a | 20.65 ± 4.79 ab | 21.65 ± 3.19 b |

| Work. mJ | 18.23 ± 2.63 a | 24.05 ± 3.93 b | 27.55 ± 5.91 b | 33.15 ± 4.01 c |

| Total number of AE events | 312 ± 65 a | 451 ± 47 b | 549 ± 39 c | 553 ± 41 c |

| Amplitude EA, mV | 312 ± 45 a | 298 ± 25 a | 299 ± 65 a | 324 ± 67 a |

| Time, µs | 77 ± 1 a | 78 ± 1 a | 77 ± 2 a | 77 ± 1 a |

| Max energy of ac. event, pJ | 326 ± 19 a | 378 ± 29 b | 395 ± 36 b | 452 ± 32 bc |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gondek, E.; Kamińska-Dwórznicka, A.; Stasiak, M.; Ostrowska-Ligęza, E. The Concept of Utilizing Waste Generated During the Production of Crispbread for the Production of Corn-Based Snacks. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10947. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162410947

Gondek E, Kamińska-Dwórznicka A, Stasiak M, Ostrowska-Ligęza E. The Concept of Utilizing Waste Generated During the Production of Crispbread for the Production of Corn-Based Snacks. Sustainability. 2024; 16(24):10947. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162410947

Chicago/Turabian StyleGondek, Ewa, Anna Kamińska-Dwórznicka, Mateusz Stasiak, and Ewa Ostrowska-Ligęza. 2024. "The Concept of Utilizing Waste Generated During the Production of Crispbread for the Production of Corn-Based Snacks" Sustainability 16, no. 24: 10947. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162410947

APA StyleGondek, E., Kamińska-Dwórznicka, A., Stasiak, M., & Ostrowska-Ligęza, E. (2024). The Concept of Utilizing Waste Generated During the Production of Crispbread for the Production of Corn-Based Snacks. Sustainability, 16(24), 10947. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162410947