Unveiling Sustainable Co-Creation Patterns in Entrepreneurial Ecosystems of Shanghai’s High-Density Urban Communities

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Works

2.1. Defining the Community-Supported Entrepreneurial Ecosystem (CSEE)

2.2. Co-Creation in CSEEs

2.3. Research Gap

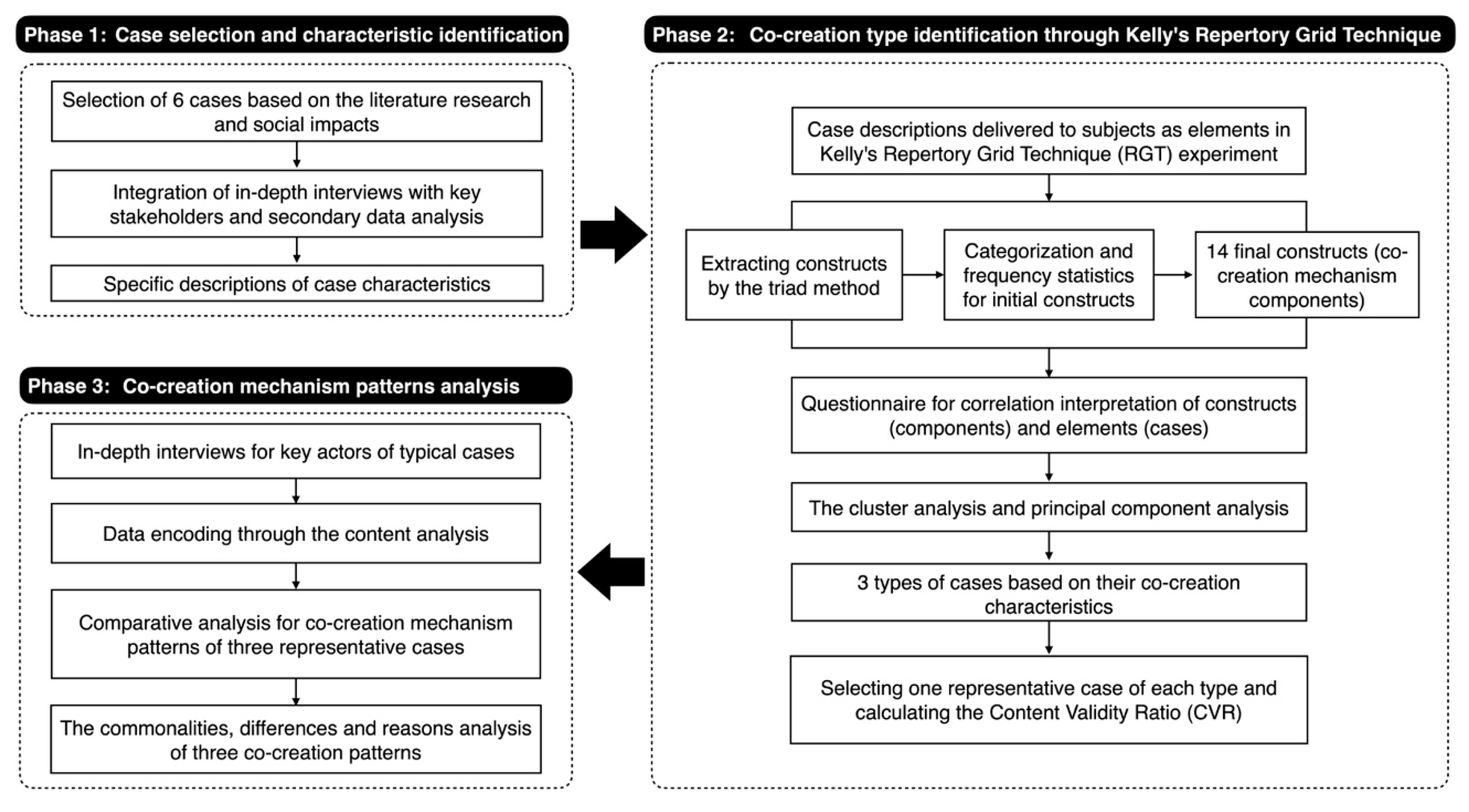

3. Method

- (a)

- Phase 1: Identification of Case Characteristics through Stakeholder Interviews

- (b)

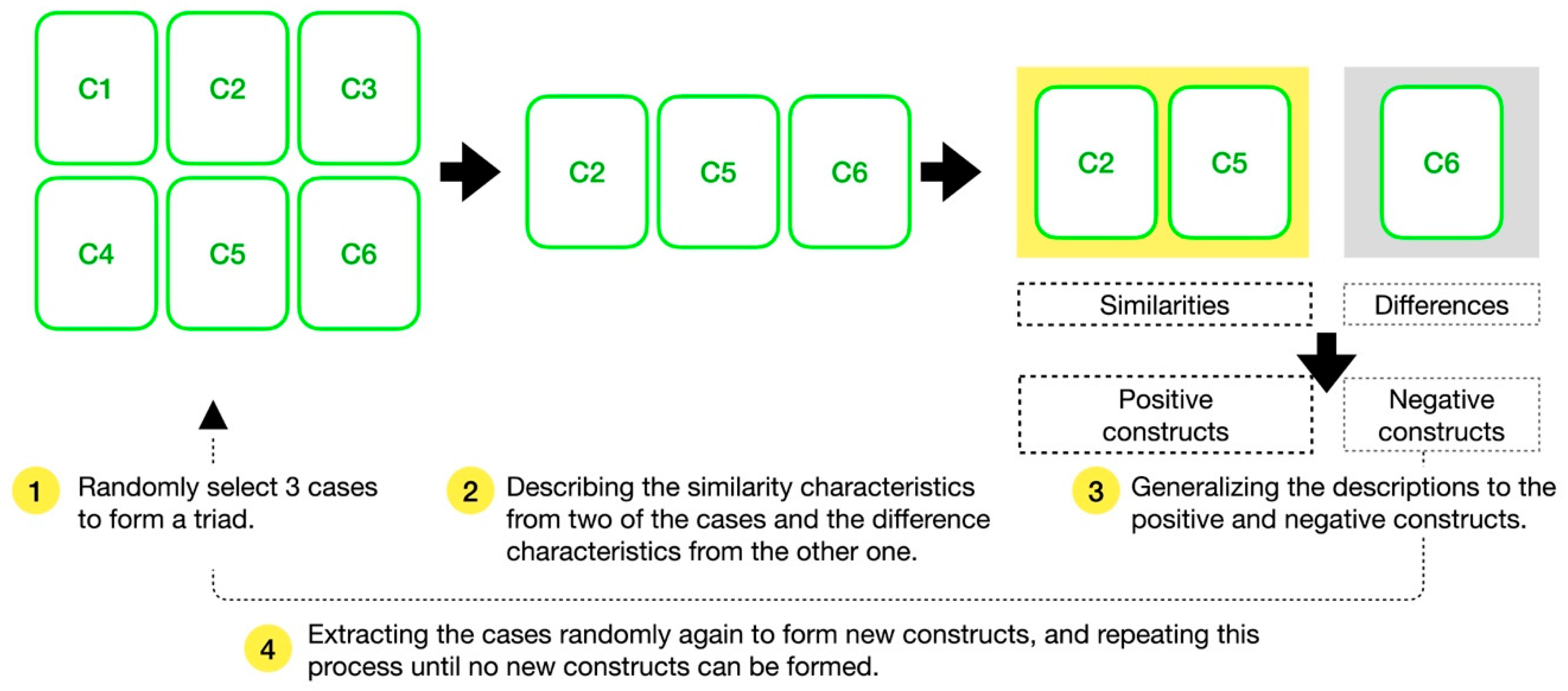

- Phase 2: Classification of Co-Creation Typologies Using Kelly’s Repertory Grid Technique

- (c)

- Phase 3: Visualization and Comparative Analysis of Co-Creation Mechanism Patterns Using a Typical Case Analysis

4. Results

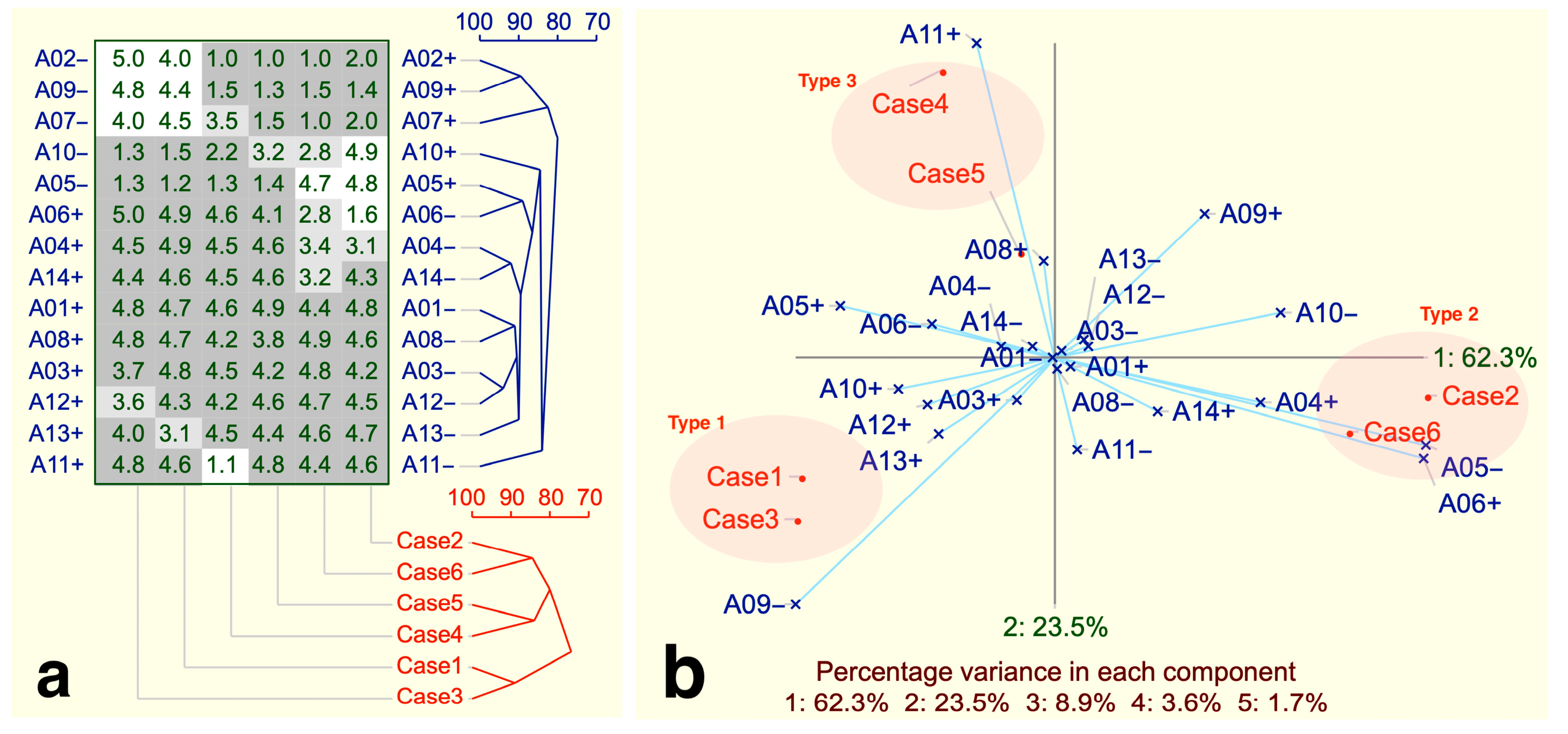

4.1. Co-Creation Mechanism Components and Case Typology Identification

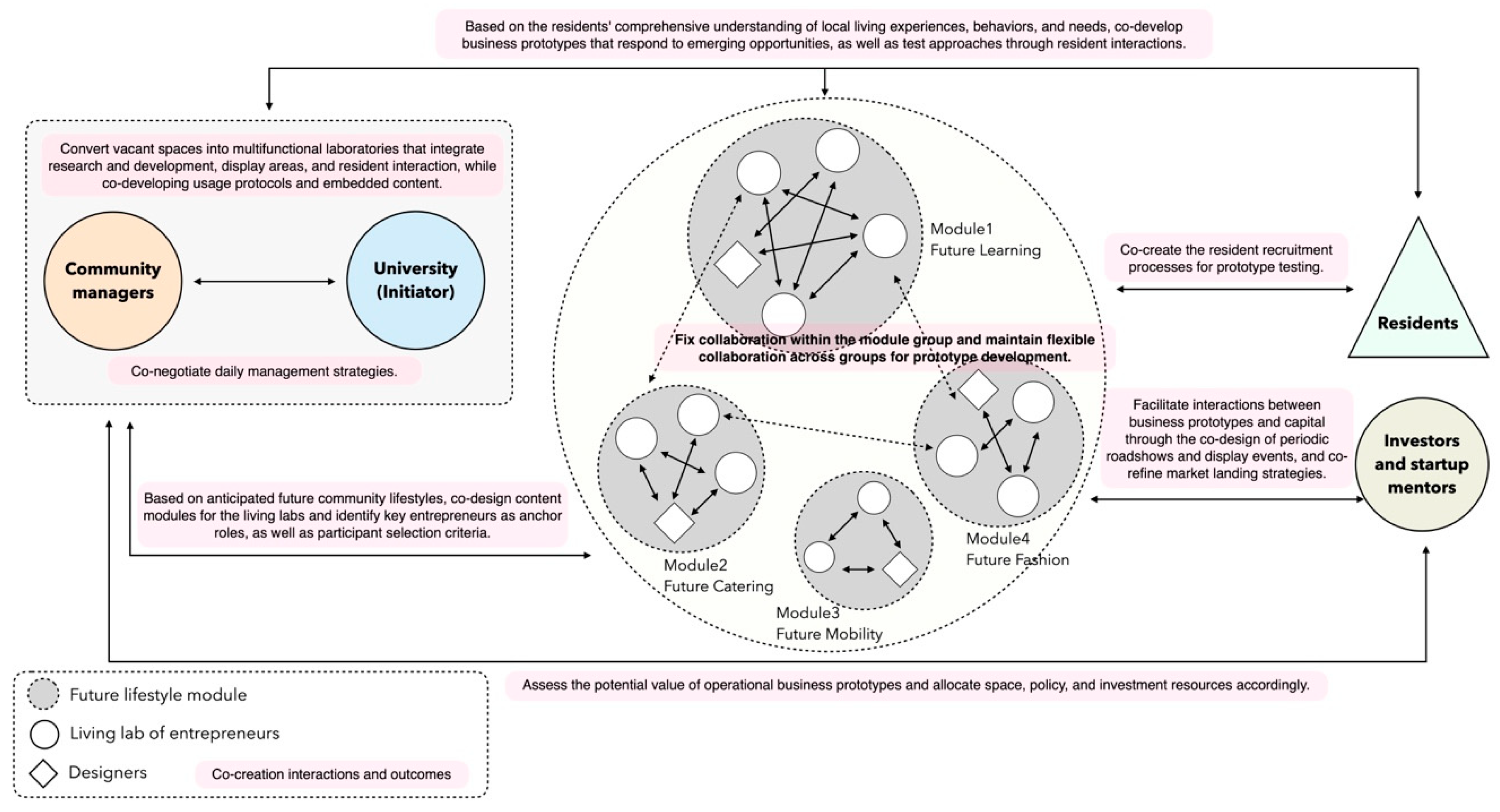

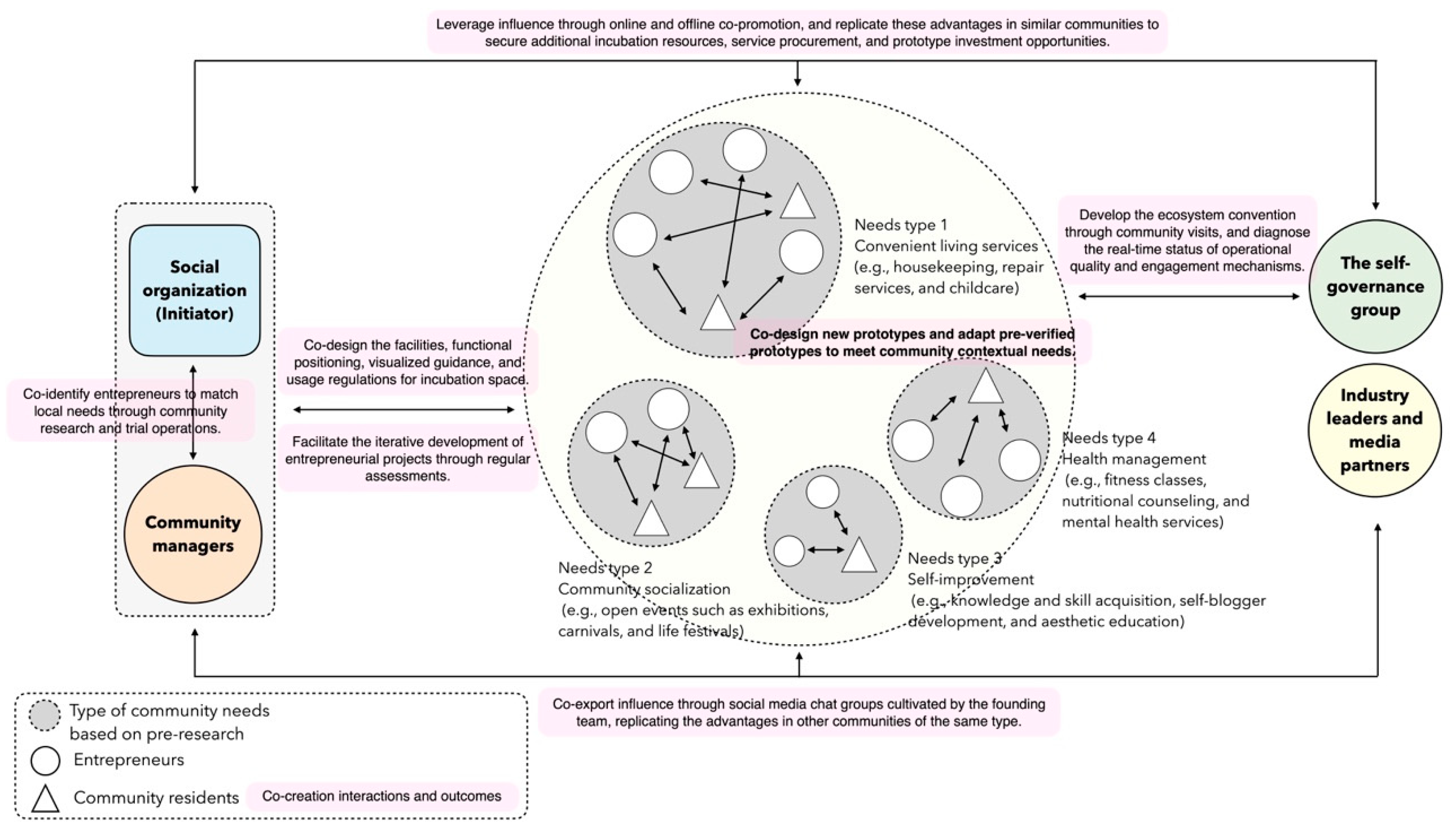

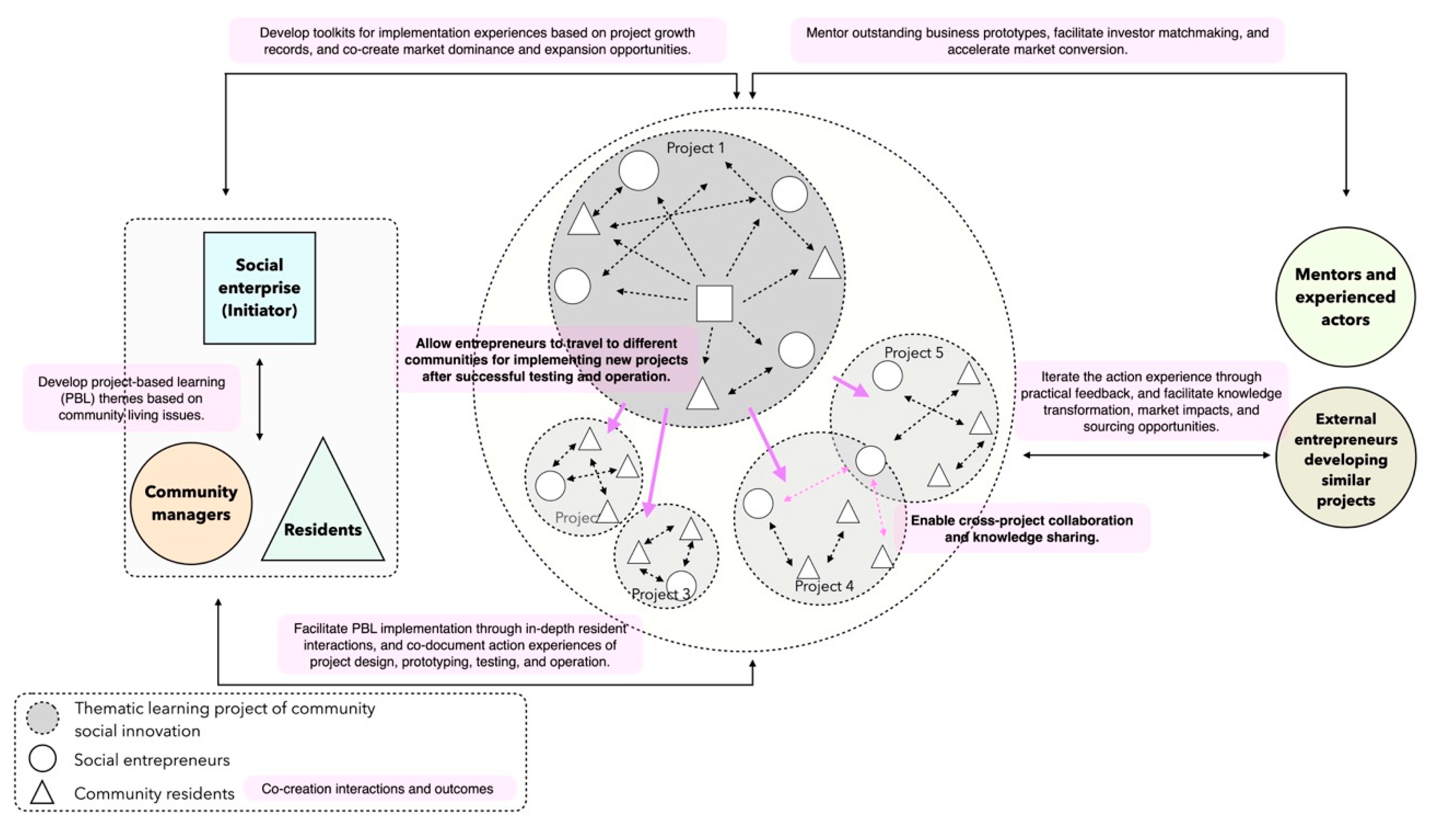

4.2. Co-Creation Mechanism Pattern Comparison

4.3. The Shaping Factors of Commonalities and Differences in Representative Cases

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- Implementation process of co-creation mechanisms: This research highlights that successful implementation relies on explicit and implicit resource connections, contextual adaptations, and the strategic engagement of social media channels. These channels not only support prototype testing and promotion, but also uncover new entrepreneurial opportunities, enhancing the scalability of co-creation practices.

- (2)

- Variation in co-creation mechanisms: This study demonstrates that intermediaries such as universities, social organizations, and social enterprises introduce varying degrees of differences in co-creation goals, process management, and evaluation methods. These variations are shaped by resource origins, entrepreneurial positioning, and participant selection, which in turn influence entrepreneurial outputs, such as user targeting, prototype conversion efficiency, and capital interactions.

- (3)

- Community benefits and local role development: Effective CSEE co-creation mechanisms not only address small-scale community needs, but also contribute significantly to enhancing community vitality and attracting social investment. The findings also emphasize the importance of empowering local stakeholders to ensure the sustainability of innovation after the departure of external advisory teams.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhao, N.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J. “Co-production” as an alternative in post-political China? Conceptualizing the legitimate power over participation in neighborhood regeneration practices. Cities 2023, 141, 104462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Luo, X.; Ying, W. Multi-level governance in the uneven integration of the city regions: Evidence of the Shanghai City Region, China. Habitat Int. 2022, 121, 102518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Qiu, B.; Wu, Y. Exploration of urban community renewal governance for adaptive improvement. Habitat Int. 2024, 144, 102999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanghai Municipal Human Resources and Social Security Bureau. Notice from the Office of the Leading Group for Employment Work in Shanghai on the Announcement of the Third Batch of Municipal-Level Characteristic Entrepreneurial Communities 2022. Available online: https://rsj.sh.gov.cn/tjypx_17737/20220715/t0035_1408379.html (accessed on 13 August 2024).

- Lou, Y.; Ma, J. Growing a community-supported ecosystem of future living: The case of NICE2035 living line. In Cross-Cultural Design Appli-Cations in Cultural Heritage, Creativity and Social Development, Proceedings of the 10th International Conference (CCD 2018), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 15–20 July 2018; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; Part II 10; pp. 320–333. [Google Scholar]

- Nylund, P.A.; Ferràs-Hernández, X.; Pareras, L.; Brem, A. The emergence of entrepreneurial ecosystems based on enabling technologies: Evidence from synthetic biology. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 149, 728–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S. The creative spatio-temporal fix: Creative and cultural industries development in Shanghai, China. Geoforum 2019, 106, 310–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Jian, I.Y.; Chan, E.H.; Chen, W. Cultural regeneration and neighborhood image from the aesthetic perspective: Case of heritage conservation areas in Shanghai. Habitat Int. 2022, 129, 102689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeever, E.; Jack, S.; Anderson, A. Embedded entrepreneurship in the creative re-construction of place. J. Bus. Ventur. 2015, 30, 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leick, B.; Leßmann, G.; Ströhl, A.; Pargent, T. Place-based entrepreneurs and their competitiveness: A relational perspective on small regional banks. J. Small Bus. Entrep. 2024, 36, 75–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhu, D. Co-creation of community micro-renewals: Model analysis and case studies in Shanghai, China. Habitat Int. 2023, 142, 102951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, F.; Wu, F. The contribution of intergroup neighbouring to community participation: Evidence from Shanghai. Urban Stud. 2020, 57, 1224–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roundy, P.T.; Fayard, D. Place-based advantages in entrepreneurship: How entrepreneurial ecosystem coordination reduces transaction costs. J. Behav. Appl. Manag. 2020, 20, 115–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florida, R. The Rise of the Creative Class--Revisited: Revised and Expanded; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Von Wirth, T.; Fuenfschilling, L.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Coenen, L. Impacts of urban living labs on sustainability transitions: Mechanisms and strategies for systemic change through experimentation. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2019, 27, 229–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varady, D.; Kleinhans, R.; Van Ham, M. The potential of community entrepreneurship for neighbourhood revitalization in the United Kingdom and the United States. In Entrepreneurial Neighbourhoods; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2017; pp. 203–228. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, C.; Xiao, Y.; Cao, H. Co-Creating for Locality and Sustainability: Design-Driven Community Regeneration Strategy in Shanghai’s Old Residential Context. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Waley, P. Who builds cities in China? How urban investment and development companies have transformed Shanghai. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2020, 44, 636–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, L.; Ye, C. Spatial production in the process of rapid urbanisation and ageing: A case study of the new type of community in suburban Shanghai. Habitat Int. 2023, 139, 102883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, D.; Dentchev, N.A. Ecosystems in support of social entrepreneurs: A literature review. Soc. Enterp. J. 2021, 17, 329–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazadi, K.; Lievens, A.; Mahr, D. Stakeholder co-creation during the innovation process: Identifying capabilities for knowledge creation among multiple stakeholders. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 525–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuunanen, T.; Lumivalo, J.; Vartiainen, T.; Zhang, Y.; Myers, M.D. Micro-level mechanisms to support value co-creation for design of digital services. J. Serv. Res. 2024, 27, 381–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Re, B.; Magnani, G. Value co-creation in circular entrepreneurship: An exploratory study on born circular SMEs. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 147, 189–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, K.R.; Read, S. An ecosystem perspective synthesis of co-creation research. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2021, 99, 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán, F.; Paswan, A.K.; Kennedy, E. Consumer brand value co-creation typology. J. Creat. Value 2019, 5, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spigel, B.; Harrison, R. Toward a process theory of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2018, 12, 151–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stam, E.; Van de ven, A. Entrepreneurial ecosystem elements. Small Bus. Econ. 2021, 56, 809–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spigel, B.; Stam, E. Entrepreneurial ecosystems. In SAGE Handbook of Small Business and Entrepreneurship; Blackburn, R., Clercq, D.D., Heinonen, J., Eds.; SAGE Publishing: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018; p. 21. [Google Scholar]

- Osano, H.M. Universities in entrepreneurial ecosystems and MSME revitalization. J. Int. Counc. Small Bus. 2021, 2, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pique, J.M.; Miralles, F.; Berbegal-Mirabent, J. Areas of innovation in cities: The evolution of 22@ Barcelona. Int. J. Knowl.-Based Dev. 2019, 10, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.; Mason, C. Looking inside the spiky bits: A critical review and conceptualisation of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Small Bus. Econ. 2017, 49, 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lado-Sestayo, R.; Neira-Gómez, I.; Chasco-Yrigoyen, C. Entrepreneurship at regional level: Temporary and neighborhood effects. Entrep. Res. J. 2017, 7, 20170111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, A.V. Entrepreneurial Ecosystem Developments in Malaysia-Existing Actors Moving from a Cluster to a Countrywide Role and the Emergence of New Actors. World Technopolis Rev. 2019, 8, 43–58. [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves, L.; Faccin, K.; Garay, J.; Zarpelon, F.; Balestrin, A. The development of Innovation and entrepreneurial ecosystems in cities: An institutional work approach. Cities 2024, 146, 104747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumpkin, G.; Bacq, S.; Pidduck, R.J. Where change happens: Community-level phenomena in social entrepreneurship research. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2018, 56, 24–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zollet, S.; Qu, M. Revitalising rural areas through counterurbanisation: Community-oriented policies for the settlement of urban newcomers. Habitat Int. 2024, 145, 103022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audretsch, D.B.; Belitski, M. Entrepreneurial ecosystems in cities: Establishing the framework conditions. J. Technol. Transf. 2017, 42, 1030–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, P.A.; Kibler, E.; Mandakovic, V.; Amorós, J.E. Local entrepreneurial ecosystems as configural narratives: A new way of seeing and evaluating antecedents and outcomes. Res. Policy 2022, 51, 104065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoraki, C.; Dana, L.-P.; Caputo, A. Building sustainable entrepreneurial ecosystems: A holistic approach. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 140, 346–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mens, J.; van Bueren, E.; Vrijhoef, R.; Heurkens, E. A typology of social entrepreneurs in bottom-up urban development. Cities 2021, 110, 103066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaringella, L.; Radziwon, A. Innovation, entrepreneurial, knowledge, and business ecosystems: Old wine in new bottles? Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2018, 136, 59–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, M.; Larsson, J.P. Local entrepreneurship clusters in cities. J. Econ. Geogr. 2016, 16, 39–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, K.R.; Read, S. Value co-creation: Concept and measurement. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2016, 44, 290–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahhar, Y.; Loohuis, R. Characterizing the spaces of consumer value experience in value co-creation and value co-destruction. Eur. J. Mark. 2022, 56, 105–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karami, M.; Read, S. Co-creative entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. 2021, 36, 106125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Silva, M.; Wright, M. Entrepreneurial co-creation: Societal impact through open innovation. RD Manag. 2019, 49, 318–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemser, G.; Perks, H. Co-creation with customers: An evolving innovation research field. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2015, 35, 660–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Omoush, K.S.; de Lucas, A.; del Val, M.T. The role of e-supply chain collaboration in collaborative innovation and value-co creation. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 158, 113647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siaw, C.A.; Sarpong, D. Dynamic exchange capabilities for value co-creation in ecosystems. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 134, 493–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, V.; Goyal, P.; Jebarajakirthy, C. Value co-creation: A review of literature and future research agenda. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2022, 37, 612–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, Y.; Parkinson, J.; Thaichon, P. Influencer marketing: Homophily, customer value co-creation behaviour and purchase intention. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 66, 102904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, M.L.; Natalia, N.; Hsieh, C. Reconceptualizing value creation: Exploring the role of goal congruence in the Co-creation process. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 66, 102947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busser, J.A.; Shulga, L.V. Role of commercial friendship, initiation and co-creation types. J. Serv. Theory Pract. 2019, 29, 488–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngongoni, C.N.; Grobbelaar, S.S.S. Value co-creation in entrepreneurial ecosystems: Learnings from a Norwegian perspective. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE AFRICON, Cape Town, South Africa, 18–20 September 2017; pp. 707–713. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, M.J.; Hazenberg, R. An evolutionary perspective on social entrepreneurship ‘ecosystems’. In A Research Agenda for Social Entrepreneurship; de Bruin, A., Tesdale, S., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2019; pp. 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Wurth, B.; Stam, E.; Spigel, B. Toward an entrepreneurial ecosystem research program. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2022, 46, 729–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dentoni, D.; Bitzer, V.; Pascucci, S. Cross-sector partnerships and the co-creation of dynamic capabilities for stakeholder orientation. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 135, 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spigel, B. Developing and governing entrepreneurial ecosystems: The structure of entrepreneurial support programs in Edinburgh, Scotland. Int. J. Innov. Reg. Dev. 2016, 7, 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, S.M.C.; Romero, J.; Bilro, R.G. Stakeholder engagement in co-creation processes for innovation: A systematic literature review and case study. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 119, 388–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B.C.A. Foundation. 2021 China Sustainable Design Award-Winning Works|Community Participatory Museum & Leisure Cooperative, Beijing. 2021. Available online: https://www.trueart.com/news/435115.html (accessed on 13 August 2024).

- Kyngäs, H.; Mikkonen, K.; Kääriäinen, M. The Application of Content Analysis in Nursing Science Research; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Klapper, R.G. A role for George Kelly’s repertory grids in entrepreneurship education? Evidence from the French and Polish context. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2014, 12, 407–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plumeyer, A.; Kottemann, P.; Böger, D.; Decker, R. Measuring brand image: A systematic review, practical guidance, and future research directions. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2019, 13, 227–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, J.-C.; Nagai, Y.; Shih, M.-C. Establishing Design Strategies and an Assessment Tool of Home Appliances to Promote Sustainable Behavior for the New Poor. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz-Na, E.; Sönmez, E. Unravelling early childhood pre-service teachers’ implicit stereotypes of scientists by using the repertory grid technique. Discip. Interdiscip. Sci. Educ. Res. 2023, 5, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghestani, A.R.; Ahmadi, F.; Tanha, A.; Meshkat, M. Bayesian critical values for Lawshe’s content validity ratio. Meas. Eval. Couns. Dev. 2019, 52, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadley, G.; Grogan, M. Using repertory grids as a tool for mixed methods research: A critical assessment. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2023, 17, 209–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukuku, O.D. Addressing Venture Growth in Nigeria Through ’Entrepreneur-Centered’ Design: A Framework for Accelerating Entrepreneurship Development Applied to Consumer Brand Entrepreneurs. Doctoral Dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Tjandra, N.C.; Ensor, J.; Thomson, J.R. Co-creating with intermediaries: Understanding their power and interest. J. Bus.-to-Bus. Mark. 2019, 26, 319–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, P.C.G.; Sjödin, D.; Nair, S.; Parida, V. Managing start-up–incumbent digital solution co-creation: A four-phase process for intermediation in innovative contexts. Ind. Innov. 2024, 31, 579–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaswamy, V.; Ozcan, K. What is co-creation? An interactional creation framework and its implications for value creation. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 84, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balta, M.; Valsecchi, R.; Papadopoulos, T.; Bourne, D.J. Digitalization and co-creation of healthcare value: A case study in Occupational Health. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 168, 120785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leone, D.; Schiavone, F.; Appio, F.P.; Chiao, B. How does artificial intelligence enable and enhance value co-creation in industrial markets? An exploratory case study in the healthcare ecosystem. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 129, 849–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| EE | CSEE | |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial features | Downtown areas or university surroundings. | Urban or suburban residential communities. |

| Outputs | Unlimited types of commercial entrepreneurship. | Commercial and social entrepreneurships driven by future community lifestyle, needs, and well-being. |

| Targets | Establishing new enterprises, controlling costs, and achieving profit growth. | Providing sustainable solutions for community issues, needs, and social relationships, accelerating market transformation through the utilization of community resources for prototype development. |

| Stakeholders | Entrepreneurs, anchor enterprises, and universities. | Entrepreneurs, universities, NGOs, and local stakeholders (such as residents, community managers, and workers) with implicit and explicit resources. |

| Investment | Investors and capital companies. | Investors, capital companies, and community crowdfunding. |

| References | [28,29,41] | [5,7,8,16,17,34,42] |

| Number | Case | Location Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| C1 | NICE 2035 | Located in the Si Ping Community of Yangpu District, adjacent to Tongji University, the project is surrounded by several workers’ new village-style communities established in the 1960s. |

| C2 | Xianxialai Cooperative | The project is situated in an underground air-raid shelter in the Hong Xian Community, Changning District. The space includes a community center offering daily services to residents and a co-creation center supporting young entrepreneurs. |

| C3 | Kangjian Future Artistic Living Co-Creative Space | The project is situated in the Kangjian Community of Xuhui District, home to a permanent population of 87,500, with a high proportion of elderly residents, making it a typical large residential community in Shanghai’s central urban area. It is adjacent to the Shanghai Institute of Technology and several other higher education institutions, boasting abundant educational resources. |

| C4 | GGB Community | Originally located on Handan Road in Yangpu District (now relocated due to spatial adjustments), the project benefits from proximity to several universities, attracting a significant influx of young entrepreneurs from nearby communities. The aim is to support the incubation of youth entrepreneurship projects through community-based experimentation. |

| C5 | Upbeing | The project is located in the Dinghai Community of Yangpu District, once a gathering area for industrial workers, with heritage buildings from a century-old industrial civilization. The project aims to guide public engagement in action learning, both online and offline, based on social issues or visions, thereby fostering social entrepreneurship incubation and co-creating a sustainable community. |

| C6 | Xinhua Community Building Center | Situated in the Xinhua Road community of Changning District, the project encompasses a rich tapestry of historical districts, heritage buildings, old residential complexes, high-end commercial housing, and cultural and office parks. The aim is to catalyze community regeneration and foster entrepreneurial initiatives through a series of community engagement activities and the stimulation of internal community dynamics. |

| Research Phase | Respondents Number and Roles |

|---|---|

| Phase 2 (The RGT process) | 18 researchers participated in RGT constructs elicitation and Likert scale scoring. They had an average of over 6 years of experience in researching community business, co-creation, and entrepreneurial ecosystem issues. (Among them, 5 individuals participated in the CVR verification process for the selection of representative case studies.) |

| Phase 3 (Co-creation mechanism analysis) | 16 respondents (involving co-founders, project managers and tutors, and designers from selected cases). |

| 5 external experts from universities and research institutions participated in CVR for coding results. They had an average of 4 years of experience in researching entrepreneurial ecosystem, stakeholder co-creation, and Shanghai community planning and regeneration. |

| Item | Components | Positive Construct (+) | Negative Construct (–) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A01 | Co-creation goals (CCGs) | Clear objectives unify collaboration and resource sharing. | Unclear co-creation objectives lead to inconsistent participant collaboration and resource use. |

| A02 | Open communication channels (OCCs) | Open and transparent communication channels foster trust and efficiency. | Unopen communication channels result in co-creation misunderstandings and a lack of trust. |

| A03 | Resource integration and allocation (RIA) | Effective integration, circulation, and optimal allocation of resources support co-creation potential realization and quality. | Ineffective integration, circulation, and optimal allocation of resources hinder co-creation potential realization and quality. |

| A04 | Stakeholder capability management (SCM) | Effective management of stakeholder capabilities ensures full utilization of expertise, enhancing co-creation professionalism and efficiency. | Poor management of stakeholder capabilities leads to an ineffective utilization of professional skills, reducing co-creation effectiveness. |

| A05 | Participant empowerment strategies (PESs) | Effective empowerment strategies ignite participants’ innovation, potential, and engagement. | Ineffective empowerment strategies limit participants’ innovation, contribution, and engagement. |

| A06 | Collaborative work mechanism (CWM) | A clear collaborative work mechanism fosters team cooperation and innovation efficiency. | The unclear collaborative work mechanism leads to poor cooperation and low innovation efficiency. |

| A07 | Innovation incentive system (IIS) | Effective innovation incentive system stimulates participants’ enthusiasm and creativity. | Insufficient innovation incentive system hinders the participants’ enthusiasm and creativity. |

| A08 | Coordination intermediary (CI) | An efficient coordination intermediary promotes information sharing, enhancing mutual trust and ensuring participants’ cultural and policy adaptation. | An inefficient coordination intermediary leads to poor information transmission, lack of trust, and barriers to cultural and policy adaptation. |

| A09 | Benefit sharing mechanism (BSM) | A clear and fair mechanism for sharing benefits strengthens co-creation cohesion and willingness. | The absence or unreasonableness sharing benefits leads to internal conflicts and co-creation obstacles. |

| A10 | Dynamic access and exit mechanism (DAEM) | A flexible access and exit mechanism maintain the vitality and adaptability of the ecosystem. | A rigid access and exit mechanism is not conducive to the vitality and adaptability of the ecosystem. |

| A11 | Ongoing evaluation and feedback (OEF) | Effective evaluation and feedback mechanism on the co-creation process and results promote continuous improvement. | Ineffective evaluation and feedback mechanism means that co-creation problems remain unresolved for a long time. |

| A12 | Community manager policy support (CMPS) | Managers provide clear and positive policy support, guiding and safeguarding co-creation activities, and enhancing the stability and predictability of the ecosystem. | Insufficient clear policy guidance or insufficient support from managers leads to uncertainty and potential risks in co-creation activities. |

| A13 | Co-creation process management (CCPM) | Managers provide clear and positive policy support, safeguarding the stability of co-creation activities. | The lack of clear or insufficient policy support leads to uncertainty and potential risks co-creation activities. |

| A14 | Co-creation education and training (CCET) | Effective pre-education and adaptive training enhances participants’ co-creation capabilities and efficiency. | Ineffective pre-education and adaptive training results in insufficient co-creation capabilities and efficiency of participants. |

| C1 | C2 | C5 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A01 (CCG) | To create a 2035 community vision emphasizing “innovation, entrepreneurship, and creation”, focusing on future lifestyle clusters, entrepreneurs, designers, residents, and other resource providers collaboratively develop and test business prototypes. Iterative testing optimizes interactions with users and capital, establishing meaningful co-creation links. | Develop community-oriented entrepreneurial projects that align with local habits and needs, supporting young entrepreneurs in designing and testing business concepts. The co-creation goal emphasizes collaboration with residents, social media practitioners, external consumers, and social organizations for sustainable community development. | Project-based learning rooted in community issues drives resident engagement in social innovation, co-creating learning methods and tools. This approach fosters community governance, empowers facilitators, and incubates social entrepreneurship through an open source action network. |

| A02 (OCC) | Encourage open discussions and feedback through social media discussion groups established by the initiator team. Regular member meetings ensure project transparency and effective communication. | Conduct large-scale home visits and participatory research to ensure community needs and suggestions are heard and aligned with entrepreneurial products and capabilities. Regular meetings are led by the entrepreneur self-governance group to enhance efficiency. | During the development and testing of prototypes, organize reflective sessions with entrepreneurs and users. Participants in online communities are encouraged to provide feedback, which enhances the conversion process of entrepreneurial projects. |

| A03 (RIA) | As the leader, the university consolidates resources for prototype development and testing, including entrepreneurial mentors, co-design participants, resident insights and enthusiasm for product testing, and promotion channels from external users and local government. | The initiating social organization repurposes unused basement spaces, integrates management policies, and leverages social media promotion resources to create a platform for testing and promoting entrepreneurial projects. | The initiator’s long-term engagement in community social innovation-built trust, integrating real-life problems into learning issues and leveraging residents’ and entrepreneurs’ problem-solving skills as resources to incubate entrepreneurial projects focused on local social innovation. |

| A04 (SCM) | Recognizing participants’ prior project experiences and capabilities, entrepreneurs are categorized into thematic modules such as future food, learning, working, and housing. The initiator team cultivates and enhances their entrepreneurial capacities through regular concept co-design and joint decision making. | The initiator team cultivates target user social media groups, leveraging opinion leaders to enhance community engagement and sustain group activity through regular tasks and rewards, thereby creating a resource pool for future prototype design and testing. | Co-create project-based learning tasks with local residents based on real-life issues, transforming these into social entrepreneurial projects. |

| A05 (PES) | Empowering residents in prototype development and testing allows them, as active contributors, to influence the design and improvement of products, services, and business models, as well as entrepreneur evaluation and selection. | Empower young entrepreneurs and residents by establishing co-management teams for daily operations, decision making, and periodic evaluations. These teams hold regular meetings to set pricing guidelines and service regulations, ensuring parallel supervision. | Empower entrepreneurs to conduct research in communities. Grant open access rights to entrepreneurs in similar situations, allowing them to learn from action experiences through toolkits, while collecting market feedback and co-building social influence. |

| A06 (CWM) | Establish collaboration tasks among living labs based on unique knowledge resources, such as pairing future sound labs with digital media design studios to develop sound-based products, interactive sound art performances, and music-centered maker courses. | Divide co-design tasks with residents for space regeneration, including layouts, signage, and functionality. In daily operations, responsibilities are divided among entrepreneurs, with oversight and joint marketing efforts. | Assign tasks, such as learning task design, outcome evaluation, resident interaction, and experience documentation based on each entrepreneur’s capabilities. Additionally, residents are matched with entrepreneurs whose project goals align with the prototype tests. |

| A07 (IIS) | The lab cluster effect has created an innovative system image of mutual benefit, attracting more partners. Regular roadshow events present commercially viable prototypes, incorporating real-life feedback, to investors and government agencies, motivating innovation by connecting directly with resource providers. | For successful projects with positive social feedback, organize themed pop-up events and lifestyle festivals with social media platforms, like Xiaohongshu, featuring live-streaming and co-promotion with influencers and bloggers, to support entrepreneurs in expanding their influence and encouraging sustainable innovation. | Incentivizing ongoing innovation and participating motivation through the entrepreneurial project and personal growth record maps, project impact accounts, online community feedbacks, and project development rewards. |

| A08 (CI) | University designers act as coordinators and co-founders, offering consultations on prototype design, improvement, and test implementation, recruiting residents for testing, and assessing participants’ co-creation behavior and attitudes to plan incubation pathways. | The initiating team serves as a coordinator, overseeing community-themed co-creation, execution, resident feedback analysis, as well as project diagnostics and evaluations. | The initiating team acts as a coordinating intermediary, managing tasks, expanding impact, and facilitating knowledge sharing between residents, entrepreneurs, and community managers. |

| A09 (BSM) | Cooperation agreements clarify the rights and interests of all parties, especially regarding co-design testing activities and joint products, ensuring the sharing of external user attention and internal user data within the community. | Develop a community agreement and benefit-sharing system through extensive research and meetings conducted by the co-management team, focusing on social attention and revenue sharing. | Through the co-promotion with actors from online communities, enable entrepreneurs to share benefits like social attention and procurement opportunities of other community managers. |

| A10 (DAEM) | Develop entry mechanisms based on ecosystem distribution and alignment with future community lifestyles. Set exit mechanisms based on feedback from prototype testing activities, adjusting participants flexibly according to co-creation behaviors, attitudes, and contributions. | Implement entry mechanisms through community visits and local research, testing participant capabilities through trial operations. For exit mechanisms, eliminate and replace participants based on performance, co-creation quality, and user feedback. | Develop entry mechanisms based on the alignment between participants’ project plans and local development issues. For exit mechanisms, assess the incubation quality and completion based on the project growth cycle and feedbacks, and adjust the participants. |

| A11 (OEF) | Regularly organize assessment meetings that involve comprehensive considerations based on market feedback, such as social media shares, comments, new followers, and backend inquiry activity levels. Conduct horizontal comparisons and periodic reviews of the content richness, inclusivity, and attractiveness of lab-provided activities. | Conduct monthly open experience events to showcase and test products and services, reflecting on market reception and execution quality. Initiators refine participant selection criteria to align with local needs. | Track participants’ long term for their project operation. Develop growth maps for entrepreneurs and projects to periodically assessing and analyze their project problems and values. |

| A12 (CMPS) | Community managers provide space usage rights, promote resident engagement, and facilitate investor connections. | Community managers provide space access and co-develop entry policies to ensure projects align with community plans and activities meet community needs. | Community managers provide feedback channels for living problems and needs for co-create learning tasks transformation, and support to build platforms for resident recruitment and promotion. |

| A13 (CCPM) | Pre-plan regular co-creation of new products and services among labs while organizing flexible prototype co-creation and collaborative R&D based on holidays, celebrations, and emerging community needs, delivering co-creation outcomes for social promotion to investors and media partners. | Based on entrepreneurs’ strengths, establish and manage online “content circles” through social media chat groups to analyze user needs and feedback, assess market acceptance, and inform activity planning within these groups. | Manage the online database and toolkits of entrepreneurial action experience, facilitating internal and external knowledge flow. |

| A14 (CCET) | Organize co-learning and co-design workshops involving residents on topics such as community fitness, arts, healthy dining, and skill acquisition, aiming to cultivate residents’ co-creation awareness, willingness, and capabilities. | Regularly organize community meetings and events to provide co-creation training, enhancing the capabilities of residents and entrepreneurs to engage in community building. | Based on local needs, conduct solution discussions and workshops to facilitate both residents and entrepreneurs in becoming familiar with and understanding the co-creation process and targets. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jiang, C.; Huang, R.; Huang, S.; Shen, T. Unveiling Sustainable Co-Creation Patterns in Entrepreneurial Ecosystems of Shanghai’s High-Density Urban Communities. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10642. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162310642

Jiang C, Huang R, Huang S, Shen T. Unveiling Sustainable Co-Creation Patterns in Entrepreneurial Ecosystems of Shanghai’s High-Density Urban Communities. Sustainability. 2024; 16(23):10642. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162310642

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiang, Chenhan, Rui Huang, Shengyu Huang, and Tao Shen. 2024. "Unveiling Sustainable Co-Creation Patterns in Entrepreneurial Ecosystems of Shanghai’s High-Density Urban Communities" Sustainability 16, no. 23: 10642. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162310642

APA StyleJiang, C., Huang, R., Huang, S., & Shen, T. (2024). Unveiling Sustainable Co-Creation Patterns in Entrepreneurial Ecosystems of Shanghai’s High-Density Urban Communities. Sustainability, 16(23), 10642. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162310642