Sustainability Education as a Predictor of Student Well-Being Through Mindfulness and Social Support: A Mediated Moderation Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Mindfulness-to-Meaning Theory and Social Support Theory

2.2. Student Well-Being

2.3. Sustainability Education

2.4. Mindfulness

2.5. Social Support

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection Procedure

3.2. Instruments

Sustainability Education

3.3. Mindfulness

3.4. Social Support

3.5. Student Well-Being

4. Results

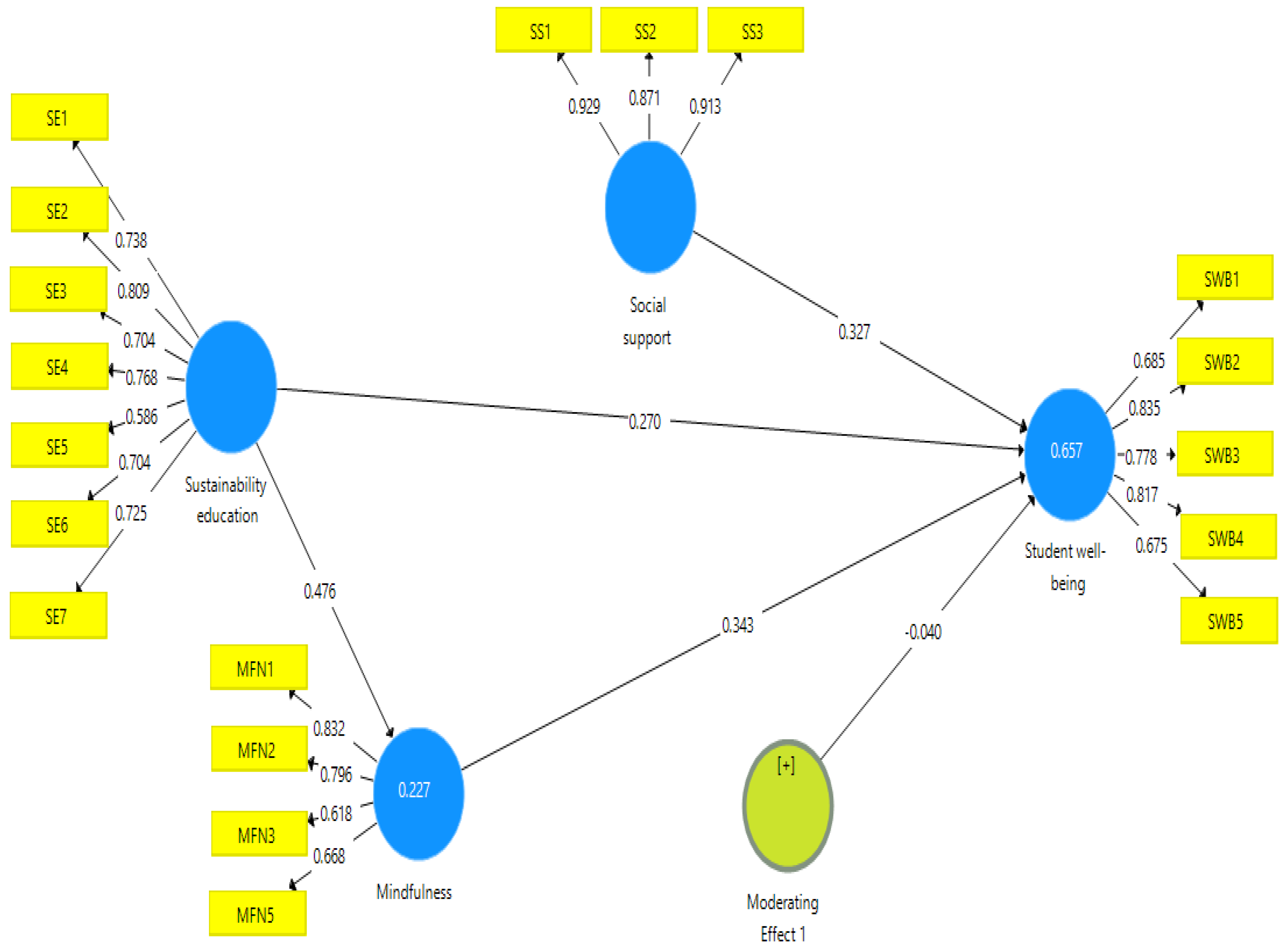

4.1. Partial Least Square-Structural Equation Modeling

4.2. Measurement Model

4.3. Structural Model

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Practical Contributions

6. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rudolf, R.; Bethmann, D. The paradox of wealthy nations’ low adolescent life satisfaction. J. Happiness Stud. 2023, 24, 79–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry, S.; Tandon, A.; Shinde, S.; Bhattacharya, A. Student psychological well-being in higher education: The role of internal team environment, institutional, friends and family support and academic engagement. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0297508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H. Psychological wellbeing in Chinese university students: Insights into the influences of academic self-concept, teacher support, and student engagement. Front. Psychol. 2024, 14, 1336682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stress Management and Student Well-Being. 2024. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/journal/education/special_issues/0V4C780SC4 (accessed on 16 October 2024).

- Bakker, A.B.; Mostert, K. Study demands–resources theory: Understanding student well-being in higher education. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2024, 36, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puiu, S.; Udriștioiu, M.T.; Petrișor, I.; Yılmaz, S.E.; Pfefferová, M.S.; Raykova, Z.; Yildizhan, H.; Marekova, E. Students’ Well-Being and Academic Engagement: A Multivariate Analysis of the Influencing Factors. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khatri, P.; Duggal, H.K.; Lim, W.M.; Thomas, A.; Shiva, A. Student well-being in higher education: Scale development and validation with implications for management education. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2024, 22, 100933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birtwell, K.; Williams, K.; Van Marwijk, H.; Armitage, C.J.; Sheffield, D. An exploration of formal and informal mindfulness practice and associations with wellbeing. Mindfulness 2019, 10, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slator, E. Mindfulness and Well-Being: Foundations. 2024. Available online: https://www.coursera.org/learn/foundations-of-mindfulness (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Soares, F.; Lopes, A.; Serrão, C.; Ferreira, E. Fostering humanization in education: A scoping review on mindfulness and teacher education. Front. Media SA 2024, 9, 1373500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.; McCaw, C.T.; Van Dam, N.T. Mindfulness in education: Critical debates and pragmatic considerations. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2024, 50, 2111–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthias, C.; Bu, C.; Cohen, M.; Jones, M.V.; Hearn, J.H. The role of mindfulness in stress, productivity and wellbeing of foundation year doctors: A mixed-methods feasibility study of the mindful resilience and effectiveness training programme. BMC Med. Educ. 2024, 24, 834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. Which Countries Contribute Most to the Global Emissions? 2024. Available online: https://www.statista.com/markets/408/topic/949/emissions/#overview (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- Hakkarainen, V.; King, J.; Brundiers, K.; Redman, A.; Anderson, C.B.; Goodall, C.N.; Pate, A.; Raymond, C.M. Online sustainability education: Purpose, process and implementation for transformative universities. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2024, 25, 333–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. Greenhouse Gas Emissions Reduction Associated with Green Recovery Measures in Emerging Markets* Between 2020 and 2030, by Sector. 2024. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1258763/greenhouse-gases-emissions-reduction-by-sector/ (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- Blom, R.; Karrow, D.D. Environmental and sustainability education in teacher education research: An international scoping review of the literature. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2024, 25, 903–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muarifah, A.; Widyastuti, D.A.; Fajarwati, I. The effect of social support on single mothers’ subjective well-being and its implication for counseling. J. Kaji. Bimbing. Dan Konseling 2024, 4, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szkody, E.; Stearns, M.; Stanhope, L.; McKinney, C. Stress-buffering role of social support during COVID-19. Fam. Process 2021, 60, 1002–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, Z.; Zhang, R.; Xiao, J. Social media use, perceived social support, and well-being: Evidence from two waves of surveys peri-and post-COVID-19 lockdown. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2024, 41, 1279–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, A.; Rehna, T. Self-Compassion and Psychological Wellbeing Among Patients With Hepatitis-C: Social Support as Moderator. Pak. J. Psychol. Res. 2024, 39, 173–194. [Google Scholar]

- Garland, E.L.; Gaylord, S.A.; Fredrickson, B.L. Positive reappraisal mediates the stress-reductive effects of mindfulness: An upward spiral process. Mindfulness 2011, 2, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, A.L.; Klussman, K.; Langer, J. Finding meaning in our everyday moments: Testing a novel intervention to increase employee well-being. Balt. J. Manag. 2022, 17, 501–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reshard, J. The Perceptions and Experiences of Employees Who Incorporate Mindfulness Meditation in Their Lives. Ph.D. Thesis, Capella University, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Garland, E.L.; Fredrickson, B.L. Positive psychological states in the arc from mindfulness to self-transcendence: Extensions of the Mindfulness-to-Meaning Theory and applications to addiction and chronic pain treatment. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2019, 28, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sgherza, T.R.; DeMarree, K.G.; Naragon-Gainey, K. Testing the mindfulness-to-meaning theory in daily life. Mindfulness 2022, 13, 2324–2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cobb, S. Social support as a moderator of life stress. Psychosom. Med. 1976, 38, 300–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kort-Butler, L. Social Support Theory. 2018. Available online: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub/774/ (accessed on 14 October 2024).

- Liu, I.; Morrison, P.S.; Zeng, D. Wellbeing heterogeneity within and among university students. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2024, 19, 215–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Wang, K.; Zhang, J.; Li, J.; Zhang, H.; Qi, R.; Xu, W.; Yan, C.; Liu, X.; Zhang, F. Potential sources and occurrence of macro-plastics and microplastics pollution in farmland soils: A typical case of China. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 54, 533–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, M. Climate Change, Air Pollution, and Human Health in the Kruger to Canyons Biosphere Region, South Africa, and Amazonas, Brazil: A Narrative Review. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danziger, J.; Willetts, J.; Larkin, J.; Chaudhuri, S.; Mukamal, K.J.; Usvyat, L.A.; Kossmann, R. Household Water Lead and Hematologic Toxic Effects in Chronic Kidney Disease. JAMA Intern. Med. 2024, 184, 788–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Ding, Y.; Guo, R.; Wang, Q.; Jia, Y. Research on the cascading mechanism of “urban built environment-air pollution-respiratory diseases”: A case of Wuhan city. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1333077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V. Noise pollution. In Textbook of Environment and Ecology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 275–281. [Google Scholar]

- Salas, E.B. Usefulness of Demonstrating for the Protection of the Environment in France. 2020. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1220830/demonstration-for-environment-protection-france/ (accessed on 4 October 2024).

- Biswas Mellamphy, N.; Vangeest, J. Human, all too human? Anthropocene narratives, posthumanisms, and the problem of “post-anthropocentrism”. Anthr. Rev. 2024, 20530196241237249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre-Mills, J.J. Regenerative Education and Safe Habitats for Diverse Species: Caterpillar Dreaming Butterfly Being. In Transformative Education for Regeneration and Wellbeing: A Critical Systemic Approach to Support Multispecies Relationships and Pathways to Sustainable Environments; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 3–29. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, E. Regenerative development as natural solution for sustainability. In The Elgar Companion to Geography, Transdisciplinarity and Sustainability; Sarmiento, F.O., Frolich, L.M., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MS, USA, 2020; Volume 10, pp. 201–218. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, P.; Fischer, D.; Stanszus, L.; Grossman, P.; Schrader, U. Mindfulness as self-confirmation? An exploratory intervention study on potentials and limitations of mindfulness-based interventions in the context of environmental and sustainability education. J. Environ. Educ. 2021, 52, 417–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muela-Bermejo, D.; Pérez-Martínez, L. Enhancing sustainability education through critical reading: A qualitative study in a Spanish primary school. Environ. Educ. Res. 2024, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efferin, S.; Soeherman, B. Mindfulness for sustainable development: A case of accounting education in Indonesia. Account. Educ. 2024, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egan, H.; O’Hara, M.; Cook, A.; Mantzios, M. Mindfulness, self-compassion, resiliency and wellbeing in higher education: A recipe to increase academic performance. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2022, 46, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goretzki, M.; Zysk, A. Using mindfulness techniques to improve student wellbeing and academic performance for university students: A pilot study. JANZSSA J. Aust. N. Z. Stud. Serv. Assoc. 2017, 25, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Fino, E.; Martoni, M.; Russo, P. Specific mindfulness traits protect against negative effects of trait anxiety on medical student wellbeing during high-pressure periods. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. 2021, 26, 1095–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E.; Freedy, J.; Lane, C.; Geller, P. Conservation of social resources: Social support resource theory. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 1990, 7, 465–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolly, P.M.; Kong, D.T.; Kim, K.Y. Social support at work: An integrative review. J. Organ. Behav. 2021, 42, 229–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranking, Q.U. Beijing Normal University, China. Available online: https://www.topuniversities.com/universities/beijing-normal-university (accessed on 7 November 2024).

- Statista. Number of Public Colleges and Universities in Beijing, China from 2010 to 2022. 2024. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1139377/china-number-of-universities-in-beijing/#:~:text=In%202022%2C%20the%20city%20of,high%20in%20global%20university%20rankings (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- Ashraf, R.; Merunka, D. The use and misuse of student samples: An empirical investigation of European marketing research. J. Consum. Behav. 2017, 16, 295–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, K. Sample size determination using Krejcie and Morgan table. Kenya Proj. Organ. (KENPRO) 1970, 38, 607–610. [Google Scholar]

- Mokgele, K.R.; Rothmann, S. A structural model of student well-being. South Afr. J. Psychol. 2014, 44, 514–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, S.; O’Neill, S.; Strnadová, I. What constitutes student well-being: A scoping review of students’ perspectives. Child Indic. Res. 2023, 16, 447–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marx-Pienaar, N.J.; Erasmus, A.C. Status consciousness and knowledge as potential impediments of households’ sustainable consumption practices of fresh produce amidst times of climate change. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2014, 38, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, M.A. South African postgraduate consumer’s attitude towards global warming. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2011, 5, 4215. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WILLIAMS, J.J.; Seaman, A.E. Corporate governance and mindfulness: The impact of management accounting systems change. J. Appl. Bus. Res. 2010, 26, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyar, M.N.; Ali, F.; Shafique, I. Green mindfulness and green creativity nexus in hospitality industry: Examining the effects of green process engagement and CSR. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 2653–2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-S.; Chang, C.-H.; Yeh, S.-L.; Cheng, H.-I. Green shared vision and green creativity: The mediation roles of green mindfulness and green self-efficacy. Qual. Quant. 2015, 49, 1169–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocalevent, R.-D.; Berg, L.; Beutel, M.E.; Hinz, A.; Zenger, M.; Härter, M.; Nater, U.; Brähler, E. Social support in the general population: Standardization of the Oslo social support scale (OSSS-3). BMC Psychol. 2018, 6, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Yuan, T.; Huang, A.; Li, X.; Yang, L.; Wang, C.; Liu, M.; Lei, Y.; Sun, L.; Li, J. Validation of the Chinese version of the Oslo-3 Social Support Scale among nursing students: A study based on Classical Test Theory and Item Response Theory models. BMC Nurs. 2024, 23, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bech, P.; Olsen, L.R.; Kjoller, M.; Rasmussen, N.K. Measuring well-being rather than the absence of distress symptoms: A comparison of the SF-36 Mental Health subscale and the WHO-Five well-being scale. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2003, 12, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, S.D.; Ware Jr, J.E.; Bentler, P.M.; Aaronson, N.K.; Alonso, J.; Apolone, G.; Bjorner, J.B.; Brazier, J.; Bullinger, M.; Kaasa, S. Use of structural equation modeling to test the construct validity of the SF-36 health survey in ten countries: Results from the IQOLA project. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1998, 51, 1179–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarstedt, M.; Liu, Y. Advanced marketing analytics using partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). J. Mark. Anal. 2024, 12, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadella, G.S.; Meduri, K.; Satish, S.; Maturi, M.H.; Gonaygunta, H. Examining E-learning tools impact using IS-impact model: A comparative PLS-SEM and IPMA case study. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2024, 10, 100351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guenther, P.; Guenther, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Zaefarian, G.; Cartwright, S. Improving PLS-SEM use for business marketing research. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2023, 111, 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taber, K.S. The use of Cronbach’s alpha when developing and reporting research instruments in science education. Res. Sci. Educ. 2018, 48, 1273–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagwovuma, M.; Maiga, G.; Nakakawa, A. Discriminant Validity of Factors for Evaluating Performance of eHealth Information Systems. In Rethinking ICT Adoption Theories in the Developing World: Information and Communication Technologies; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 47–70. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samantaray, S.K.; Farhan, M.; Singh, P.; Kakkar, A. Impact of e-NAM on organic agriculture farmers’ economic growth: A SmartPLS approach. Org. Agric. 2024, 14, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J., Jr; Hair, J.F., Jr; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Gudergan, S.P. Advanced Issues in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling; saGe publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, P.; Fischer, D.; Wamsler, C. Mindfulness, education, and the sustainable development goals. Qual. Educ. 2020, 545–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyrbye, L.N.; Shanafelt, T.D. Commentary: Medical student distress: A call to action. Acad. Med. 2011, 86, 801–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, A.; Truscott, J. Meditation in the classroom: Supporting both student and teacher wellbeing? Educ. 3-13 2020, 48, 807–819. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, R.; Chhikara, D. Sustainable consumption and mindfulness: Analysing knowledge-attitude-practice gap among Indian young professionals. Int. J. Sustain. Econ. 2023, 15, 263–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z. Confucianism, modernization and Chinese pedagogy: An introduction. J. Curric. Stud. 2011, 43, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, C. Lide Shuren: National Literacies and Social Status in a Rural and an Urban High School in China; The University of Edinburgh: Edinburgh, Scotland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory. In Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 6229–6235. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, G.; Abu Bakar, R.; Omar, S. Positive psychology and employee adaptive performance: Systematic literature review. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1417260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tourangeau, R.; Yan, T. Sensitive questions in surveys. Psychol. Bull. 2007, 133, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Demographics | Category | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 219 | 53.03 |

| Female | 194 | 46.97 | |

| Age | 18–22 years | 169 | 40.92 |

| 23–27 years | 133 | 32.20 | |

| 28–32 years | 72 | 17.43 | |

| 33 and above years | 39 | 9.45 | |

| Classes | Und-graduation | 259 | 62.71 |

| Graduation | 92 | 22.28 | |

| Post-graduation | 62 | 15.01 | |

| Disciplines | Education | 182 | 44.07 |

| Management | 137 | 33.17 | |

| Law | 67 | 16.22 | |

| Sociology | 27 | 6.54 |

| Variables | Items | OL | CA | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sustainability education | SE1 | 0.738 | 0.849 | 0.883 | 0.521 |

| SE2 | 0.809 | ||||

| SE3 | 0.704 | ||||

| SE4 | 0.768 | ||||

| SE5 | 0.586 | ||||

| SE6 | 0.704 | ||||

| SE7 | 0.725 | ||||

| Mindfulness | MFN1 | 0.832 | 0.711 | 0.821 | 0.539 |

| MFN2 | 0.796 | ||||

| MFN3 | 0.618 | ||||

| MFN5 | 0.668 | ||||

| Social support | SS1 | 0.929 | 0.889 | 0.931 | 0.818 |

| SS2 | 0.871 | ||||

| SS3 | 0.913 | ||||

| Student well-being | SWB1 | 0.685 | 0.816 | 0.872 | 0.579 |

| SWB2 | 0.835 | ||||

| SWB3 | 0.778 | ||||

| SWB4 | 0.817 | ||||

| SWB5 | 0.675 |

| MFN | SS | SWB | SE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MFN | 0.734 | |||

| SS | 0.705 | 0.905 | ||

| SWB | 0.721 | 0.698 | 0.761 | |

| SE | 0.476 | 0.409 | 0.588 | 0.722 |

| Hypothesis | Coefficients | t-Value | p-Value | Decision | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Sustainability Education → Mindfulness | 0.476 | 7.933 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H2 | Mindfulness → Student Well-being | 0.343 | 5.639 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H3 | Sustainability Education → Mindfulness → Student Well-being | 0.163 | 5.040 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H4 | Social Support → Student Well-being | 0.327 | 5.733 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H5 | Social Support × Mindfulness → Student Well-being | −0.040 | 1.207 | 0.228 | Not Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gu, Y.; Sun, B.; He, J.; Huang, W. Sustainability Education as a Predictor of Student Well-Being Through Mindfulness and Social Support: A Mediated Moderation Model. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10508. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162310508

Gu Y, Sun B, He J, Huang W. Sustainability Education as a Predictor of Student Well-Being Through Mindfulness and Social Support: A Mediated Moderation Model. Sustainability. 2024; 16(23):10508. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162310508

Chicago/Turabian StyleGu, Yuanhai, Bo Sun, Jun He, and Wenjuan Huang. 2024. "Sustainability Education as a Predictor of Student Well-Being Through Mindfulness and Social Support: A Mediated Moderation Model" Sustainability 16, no. 23: 10508. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162310508

APA StyleGu, Y., Sun, B., He, J., & Huang, W. (2024). Sustainability Education as a Predictor of Student Well-Being Through Mindfulness and Social Support: A Mediated Moderation Model. Sustainability, 16(23), 10508. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162310508