An IPA Analysis of Tourist Perception and Satisfaction with Nisville Jazz Festival Service Quality

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Location of the Study Area

3.2. Instrument

3.3. Collecting Data

3.4. Respondents

3.5. Methods

4. Results

4.1. Factor Analysis of the Quality of Cultural and Other Content of the Festival

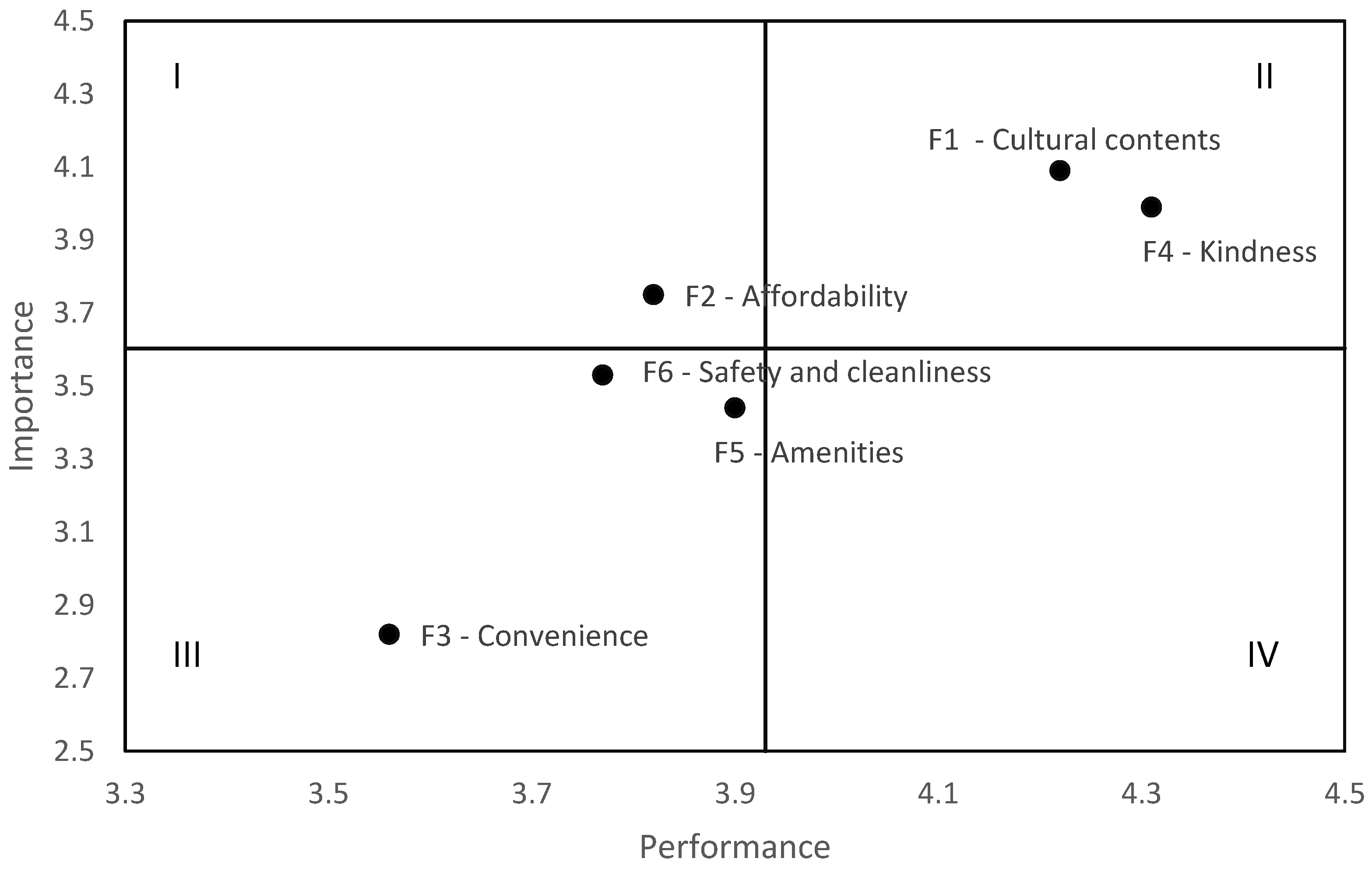

4.2. IPA Analysis of the Factors Extracted in the Factor Analysis

4.3. t-Test Results—Observed Factors Between Genders

4.4. Differences in Average Ratings of Observed Factors

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gibson, C.; Connell, J. Music Festivals and Regional Development in Australia; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, B.T. Sustainable tourism and the role of festivals in the Caribbean—Case of the St. Lucia Jazz (& Arts) Festival. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2019, 44, 258–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sales, F.; Ryan, C. Jazz and knitwear: Factors that attract tourists to festivals. Tour. Manag. 1993, 14, 289–297. [Google Scholar]

- Del Barrio, M.J.; Devesa, M.; Herrero, L.C. Evaluating intangible cultural heritage: The case of cultural festivals. City Cult. Soc. 2012, 3, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Reverté, F.; Miralbell-Izard, O. Managing music festivals for tourism purposes in Catalonia (Spain). Tour. Rev. 2009, 64, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayazlar, R.A.; Ayazlar, G. The festival motivation and its consequences: The case of the Fethiye International Culture and Art Festival, Turkey. J. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 3, 53–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Maneenetr, T.; Tran, T.H. Developing cultural tourism through local festivals: A case study of the Naga Fireball Festival, Nong Khai Province, Thailand. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2014, 5, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lee, T.H.; Hsu, F.Y. Examining how attending motivation and satisfaction affects the loyalty for attendees at Aboriginal festivals. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2011, 15, 18–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felsenstein, D.; Fleischer, A. Local festivals and tourism promotion: The role of public assistance and visitor expenditure. J. Travel Res. 2003, 41, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruger, M.; Saayman, M. ‘All that jazz’: The relationship between music festival visitors’ motives and behavioural intentions. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 22, 2399–2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, R.; Vignali, C. Creating local experiences of cultural tourism through sustainable festivals. Eur. J. Tour. Hosp. Recreat. 2010, 1, 51–67. [Google Scholar]

- Baum, T.; Hagen, L. Responses to seasonality: The experiences of peripheral destinations. Int. J. Tour. Res. 1999, 1, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, M.; Picard, D.; Long, P. Introduction—Festival tourism: Producing, translating, and consuming expressions of culture(s). Event Manag. 2004, 8, 187–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, D.; Andersson, T. Sustainable festivals: On becoming an institution. Event Manag. 2008, 12, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, P.; Folgado-Fernández, J.A.; Hernández-Mogollón, J.M. Measurement of the impact of music festivals on destination image: The case of a WOMAD festival. Event Manag. 2018, 22, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pivac, T.; Blešić, I.; Kovačić, S.; Besermenji, S.; Lesjak, M. Visitors’ satisfaction, perceived quality, and behavioral intentions: The case study of Exit Festival. J. Geogr. Inst. Cvijic 2019, 69, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.D.; Var, T.; Lee, S. Messina Hof Wine and Jazz Festival: An economic impact analysis. Tour. Econ. 2002, 8, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lashua, B.; Spracklen, K.; Long, P. Introduction to the special issue: Music and tourism. Tour. Stud. 2014, 14, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, D. Event Management & Event Tourism; Cognizant Communication Corporation: Toronto, ON, Canada, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, H.; Daniels, M. Does the music matter? Motivations for attending a music festival. Event Manag. 2005, 9, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnautović, J.S. Muzički Festivali u Srbiji u prvoj Deceniji 21. veka kao Mesta Interkulturalnih Dijaloga. [Music Festivals in Serbia in the First Decade of the Twenty-First Century as Places of Intercultural Dialogues]. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Arts, Belgrade, Serbia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Campos, A.C.; Mendes, J.; Valle PO, D.; Scott, N. Co-creation of tourist experiences: A literature review. Curr. Issues Tour. 2018, 21, 369–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armbrecht, J. Event quality, perceived value, satisfaction and behavioural intentions in an event context. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2021, 21, 169–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edensor, T. Staging tourism: Tourists as performers. Ann. Tour. Res. 2000, 27, 322–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/travel/2016/apr/20/top-10-jazz-festivals-europe-montreux-umbria-cork (accessed on 19 December 2023).

- Jung, S.; Tanford, S. What contributes to convention attendee satisfaction and loyalty? A meta-analysis. J. Conv. Event Tour. 2017, 18, 118–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozak, M. Comparative assessment of tourist satisfaction with destinations across two nationalities. Tour. Manag. 2001, 22, 391–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.; Uysal, M. An examination of the effects of motivation and satisfaction on destination loyalty: A structural model. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, G.Q.; Qu, H. Examining the structural relationships of destination image, tourist satisfaction and destination loyalty: An integrated approach. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 624–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szmigin, I.; Bengry-Howell, A.; Morey, Y.; Griffin, C.; Riley, S. Socio-spatial authenticity at co-created music festivals. Ann. Tour. Res. 2017, 63, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B. What facilitates a festival tourist? Investigating tourists’ experiences at a local community festival. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2015, 20, 1005–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, A.; Parker, A.; Stockport, G. The relationship of hygiene, motivator, and professional strategic capabilities to the performance of Australian music festival event management organizations. Event Manag. 2018, 22, 767–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangpikul, A. Acquiring an in-depth understanding of assurance as a dimension of the SERVQUAL model in regard to the hotel industry in Thailand. Curr. Issues Tour. 2023, 26, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmaki, A. Tourism and hospitality internships: A prologue to career intentions? J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2018, 23, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, A.Y.; Makki, A.A. A DEMATEL-ISM integrated modeling approach of influencing factors shaping destination image in the tourism industry. Adm. Sci. 2023, 13, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.Y.; Lee, K.C.; Lee, K.S.; Babin, J.B. Festivalscapes and patrons’ emotions, satisfaction, and loyalty. J. Bus. Res. 2008, 61, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babin, B.J.; Griffin, M. The nature of satisfaction: An updated examination and analysis. J. Bus. Res. 1998, 41, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, R.N.; Lemon, K.N. A dynamic model of customers’ usage of services: Usage as an antecedent and consequence of satisfaction. J. Mark. Res. 1999, 36, 171–186. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, S.T.; Illum, S.F. Examining the mediating role of festival visitors’ satisfaction in the relationship between service quality and behavioral intentions. J. Vacat. Mark. 2006, 12, 160–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Johnson, M.D.; Anderson, E.W.; Cha, J.; Bryant, B.E. The American customer satisfaction index: Nature, purpose, and findings. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDougall, G.H.; Levesque, T. Customer satisfaction with services: Putting perceived value into the equation. J. Serv. Mark. 2000, 14, 392–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kyle, G.; Scott, D. The mediating effect of place attachment on the relationship between festival satisfaction and loyalty to the festival hosting destination. J. Travel Res. 2012, 51, 754–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.J.; Lin, S.Y. The service satisfaction of jazz festivals in structural equation modeling under conditions of value and loyalty. J. Conv. Event Tour. 2016, 17, 266–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Monteagudo, A.; Curras-Perez, R. Live and online music festivals in the COVID-19 era: Analysis of motivational differences and value perceptions. Rev. Bras. Gestão Negócios 2022, 24, 420–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrucci, L.; Forlani, F.; Splendiani, S. The economic-impact evaluation of cultural events: The case of the Umbria Jazz Festival. Anatolia 2022, 33, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, S.F.A.; Ahsan, F.T.; Nadi, A.H.; Ahmed, M.; Neyamah, H. Exploring the role of technology application in tourism events, festivals and fairs in the United Arab Emirates: Strategies in the post pandemic period. In Technology Application in Tourism Fairs, Festivals and Events in Asia; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 313–330. [Google Scholar]

- Ezeuduji, I.O. Cultural events and tourism in Africa. In Cultural Heritage and Tourism in Africa; Routledge: London, UK, 2023; p. 26. [Google Scholar]

- Bakić, S.; Cuenca, J.; Cuenca-Amigo, M. Measuring the audience experience at the Jazzaldia Festival, San Sebastian, Spain. Event Manag. 2023, 27, 163–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šušić, V.; Bratić, M.; Milovanović, M. Demographic and socioeconomic characteristics and motives of the visitors to the tourist manifestation Nisville Jazz Festival. Teme 2016, 1, 123–137. [Google Scholar]

- Martín-Santana, J.D.; Beerli-Palacio, A.; Nazzareno, P.A. Antecedents and consequences of destination image gap. Ann. Tour. Res. 2017, 62, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, E.H.; Kinnunen, M. Reminiscence and wellbeing–Reflecting on past festival experiences during COVID lockdowns. Int. J. Event Festiv. Manag. 2023, 15, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutabarat, P.M. Music tourism potentials in Indonesia: Music festivals and their roles in city branding. J. Vokasi Indones. 2022, 7, 44–54. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, L.J.; Mansfield, S.; McKenna, U.; Jones, S.H. Enhancing inclusivity and diversity among cathedral visitors: The Brecon Jazz Festival and psychographic segmentation. J. Beliefs Values 2022, 44, 563–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán, T.L. Satisfaction and loyalty in musical festivals: Study based on the level of jazz musical knowledge. Tec Empres. 2022, 17, 95–104. [Google Scholar]

- Raine, S.; Medbøe, H.; Dias, J. Jazz festivals in the time of COVID-19: Exploring exposed fragilities, community resilience and industry recovery. In Rethinking the Music Business: Music Contexts, Rights, Data, and COVID-19; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Swizerland, 2022; pp. 109–127. [Google Scholar]

- Swamidoss, S.B.E.; Venkatesan, D.G.; Arun, R. Impact of Hospitality Services on Tourism Industry in Coimbatore District. J. Namib. Stud. Hist. Politics Cult. 2023, 33, 2381–2393. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, D.; Clarke, J. Reflection on tourism satisfaction research: Past, present and future. J. Vacat. Mark. 2002, 8, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spasić, V.; Pavlović, D. Poslovanje Turističkih Agencija i Organizatora Putovanja; Univerzitet Singidunum: Beograd, Serbia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Przybytnowski, J.W. Servqual method in studying service quality of travel insurance. Bus. Theory Pract. 2023, 24, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Dong, H. Research on Service Quality Improvement of Tianmu Lake Scenic Spot Based on SERVQUAL Model. In 2022 2nd International Conference on Management Science and Software Engineering (ICMSSE 2022); Atlantis Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 608–612. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, T.S.; Chan, J.K.L. Experience attributes and service quality dimensions of peer-to-peer accommodation in Malaysia. Heliyon 2023, 9, e18403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowalska, N.; Ostręga, A. Using SERVQUAL method to assess tourist service quality by the example of the Silesian Museum established on the post-mining area. Land 2020, 9, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajić, T.; Petrović, M.D.; Radovanović, M.M.; Tretiakova, T.N.; Syromiatnikova, J.A. Possibilities of turning passive rural areas into tourist attractions through attained service quality. Eur. Countrys. 2020, 12, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://nisville.com/sr/istorijat-festivala/ (accessed on 23 November 2023).

- Available online: https://nisville.com/sr/o-nisville-jazz-festivalu/ (accessed on 24 November 2023).

- Blešić, I.; Popov-Raljić, J.; Uravić, L.; Stankov, U.; Đeri, L.; Pantelić, M.; Armenski, T. An importance-performance analysis of service quality in spa hotels. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraživanja 2014, 27, 483–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A.; Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L. Servqual: A multiple-item scale for measuring consumer perc. J. Retail. 1988, 64, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Trišić, I.; Štetić, S.; Maksin, M.; Blešić, I. Perception and Satisfaction of Residents with the Impact of the Protected Area on Sustainable Tourism-the Case of Deliblatska Peščara Special Nature Reserve, Serbia. Geogr. Pannonica 2021, 25, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martilla, J.A.; James, J.C. Importance-performance analysis. J. Mark. 1977, 41, 77–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzler, K.; Bailom, F.; Hinterhuber, H.H.; Renzl, B.; Pichler, J. The asymmetric relationship between attribute-level performance and overall customer satisfaction: A reconsideration of the importance–performance analysis. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2004, 33, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duke, C.R.; Persia, M.A. Performance-importance analysis of escorted tour evaluations. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 1996, 5, 207–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, M.R.; Chon, K.S. Formulating and evaluating tou rism policy using importance-Performance analysis. Hosp. Educ. Res. J. 1989, 13, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, D.J.; Eagles, P.F. The use of importance–performance analysis and market segmentation for tourism management in parks and protected areas: An application to Tanzania’s national parks. J. Ecotourism 2003, 2, 196–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGee, K. Gendered Interventions in European Jazz Festival Programming: Keychanges, Stars, and Alternative Networks. In The Routledge Companion to Jazz and Gender; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; pp. 190–204. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, C.; Delgado, N.; García-Bello, M.Á.; Hernández-Fernaud, E. Exploring crowding in tourist settings: The importance of physical characteristics in visitor satisfaction. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 20, 100619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, L.J.; Robbins, M.; Annis, J. The Gospel of Inclusivity and Cathedral Visitors. In Anglican Cathedrals in Modern Life: The Science of Cathedral Studies; Francis, L.J., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 189–214. [Google Scholar]

- Saayman, M.; Rossouw, R. The Cape Town international jazz festival: More than just jazz. Dev. South. Afr. 2010, 27, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arasli, H.; Abdullahi, M.; Gunay, T. Social media as a destination marketing tool for a sustainable heritage festival in Nigeria: A moderated mediation study. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elisa, S.; Elena, C.M.; Botella-Nicolás, A.M.; Isusi-Fagoaga, R. The importance of research on cultural festivals. Int. J. Arts Manag. 2022, 24, 4–12. [Google Scholar]

- Folgado-Fernández, J.A.; Di-Clemente, E.; Hernández-Mogollón, J.M. Food festivals and the development of sustainable destinations. The case of the cheese fair in Trujillo (Spain). Sustainability 2019, 11, 2922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigala, M. Tourism and COVID-19: Impacts and implications for advancing and resetting industry and research. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez García, J.; Bigné Alcañiz, J.E. Influencia del contenido informativo de la publicidad y de la implicación en un modelo de actitudes. Rev. Eur. Dir. Econ. Empresa 2001, 10, 85–102. [Google Scholar]

- Pavluković, V.; Stankov, U.; Arsenović, D. Social impacts of music festivals: A comparative study of Sziget (Hungary) and Exit (Serbia). Acta Geogr. Slov. 2020, 60, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warith, M.F.A. Using Importance-Performance Analysis to Identify Factors Affecting the Sustainable Events: Tourists’ Perspective. J. Fac. Tour. Hotel.-Univ. Sadat City 2021, 5, 39–58. [Google Scholar]

- Rašovská, I.; Kubickova, M.; Ryglová, K. Importance–performance analysis approach to destination management. Tour. Econ. 2021, 27, 777–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, B. Communication skills for success: Tourism industry specific guidelines. Mag. Glob. Engl. Speak. High. Educ. 2011, 3, 13–14. [Google Scholar]

- Barjaktarović, D. Upravljanje kvalitetom u hotelijerstvu [Quality Management in the Hotel Industry]; Univerzitet Singidunum: Beograd, Serbia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Getz, D. Event tourism: Definition, evolution, and research. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 403–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavluković, V.; Armenski, T.; Alcántara-Pilar, J.M. Social impacts of music festivals: Does culture impact locals’ attitude toward events in Serbia and Hungary? Tour. Manag. 2017, 63, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitrović, M.; Vulić, T. Nisville in the Media; Facta Universitatis, Series: Visual Arts and Music; Facta Universitatis: Nis, Serbia, 2020; pp. 153–162. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S.; Hsu, C.H.; Chan, A. Tour guide performance and tourist satisfaction: A study of the package tours in shanghai. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2010, 34, 3–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Frequency | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 100 | 44.1 |

| Female | 127 | 55.9 |

| Age | ||

| 18–19 | 34 | 15.0 |

| 20–29 | 93 | 41.0 |

| 30–39 | 34 | 15.0 |

| 40–49 | 30 | 13.2 |

| 50–59 | 30 | 13.2 |

| Over 60 | 6 | 2.6 |

| Educational attainment | ||

| Primary education | 11 | 4.8 |

| Secondary education | 62 | 27.3 |

| Higher education | 45 | 19.8 |

| Higher education (University) | 109 | 48.0 |

| Type | ||

| Domestic visitors | 195 | 84.9 |

| Foreign visitors | 32 | 15.1 |

| Loading | Eigenvalue | % of Explained Variance | Cronbach’s α | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 Cultural content | Music | 0.848 | 3.348 | 15.218 | 0.846 |

| A large number of famous performers | 0.773 | ||||

| Event authenticity | 0.765 | ||||

| Quality of accompanying content | 0.676 | ||||

| Specificity of the venue | 0.521 | ||||

| Open stage | 0.505 | ||||

| F2 Affordability | Ticket price | 0.855 | 3.175 | 14.433 | 0.884 |

| Price of ticket packages | 0.829 | ||||

| Beverage prices | 0.804 | ||||

| Food price | 0.780 | ||||

| F3 Convenience | The quality of boarding accommodation | 0.864 | 2.198 | 9.992 | 0.741 |

| Close to the hotel | 0.802 | ||||

| Parking | 0.659 | ||||

| F4 Kindness | Kindness | 0.822 | 2.197 | 9.984 | 0.723 |

| Warmth | 0.790 | ||||

| Attractiveness of the locality | 0.591 | ||||

| F5 Amenities | Workshops | 0.709 | 2.112 | 9.599 | 0.709 |

| Traffic position | 0.687 | ||||

| Accessibility | 0.675 | ||||

| F6 Safety and cleanliness | Hygiene | 0.788 | 2.058 | 9.356 | 0.748 |

| Space equipment | 0.724 | ||||

| Safety | 0.657 |

| Importance | Performance | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean | Std. Dev | Mean | Std. Dev | |

| F1—Cultural content | 227 | 4.09 | 0.71 | 4.22 | 0.78 |

| Music | 227 | 4.60 | 0.81 | 4.40 | 0.93 |

| A large number of famous performers | 227 | 4.07 | 1.01 | 4.03 | 1.06 |

| Event authenticity | 227 | 4.30 | 0.96 | 4.38 | 0.89 |

| Quality of accompanying content | 227 | 4.00 | 1.07 | 4.18 | 0.97 |

| Specificity of the venue | 227 | 3.62 | 1.29 | 4.19 | 1.08 |

| Open stage | 227 | 3.94 | 1.20 | 4.28 | 0.90 |

| F2—Affordability | 227 | 3.75 | 0.99 | 3.82 | 0.94 |

| Ticket price | 227 | 3.82 | 1.23 | 3.82 | 1.14 |

| Price of ticket packages | 227 | 3.95 | 1.22 | 3.99 | 1.06 |

| Beverage prices | 227 | 3.76 | 1.20 | 3.77 | 1.10 |

| Food price | 227 | 3.49 | 1.26 | 3.71 | 1.09 |

| F3—Convenience | 227 | 2.82 | 1.21 | 3.56 | 0.93 |

| The quality of boarding accommodation | 227 | 2.71 | 1.35 | 3.54 | 1.15 |

| Close to the hotel | 227 | 2.81 | 1.38 | 3.84 | 1.08 |

| Parking | 227 | 2.93 | 1.44 | 3.29 | 1.18 |

| F4—Kindness | 227 | 3.99 | 0.88 | 4.31 | 0.69 |

| Kindness | 227 | 4.31 | 0.95 | 4.48 | 0.79 |

| Warmth | 227 | 4.22 | 1.04 | 4.52 | 0.76 |

| Attractiveness of the locality | 227 | 3.44 | 1.37 | 3.93 | 1.03 |

| F5—Amenities | 227 | 3.44 | 0.99 | 3.90 | 0.80 |

| Workshops | 227 | 3.49 | 1.26 | 3.89 | 1.00 |

| Traffic position | 227 | 3.21 | 1.34 | 3.76 | 1.03 |

| Accessibility | 227 | 3.63 | 1.20 | 4.05 | 0.98 |

| F6—Safety and cleanliness | 227 | 3.53 | 0.99 | 3.77 | 0.80 |

| Hygiene | 227 | 3.27 | 1.23 | 3.48 | 0.99 |

| Space equipment | 227 | 3.38 | 1.26 | 3.73 | 0.94 |

| Safety | 227 | 3.95 | 1.25 | 4.08 | 1.01 |

| Importance | Performance | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genders | N | Mean | Std. Dev | T | sig | Mean | Std. Dev | t | sig | |

| F1 Cultural content | Male | 101 | 3.92 | 0.75 | −3.264 | 0.001 | 101 | 4.10 | −2.148 | 0.033 |

| Female | 129 | 4.22 | 0.64 | 129 | 4.32 | |||||

| F2 Affordability | Male | 101 | 3.51 | 0.99 | −3.286 | 0.001 | 101 | 3.76 | −0.849 | 0.397 |

| Female | 129 | 3.93 | 0.95 | 128 | 3.87 | |||||

| F3 Convenience | Male | 101 | 2.65 | 1.14 | −1.903 | 0.058 | 101 | 3.54 | −0.281 | 0.779 |

| Female | 129 | 2.95 | 1.25 | 128 | 3.57 | |||||

| F4 Kindness | Male | 101 | 3.86 | 0.82 | −2.006 | 0.046 | 101 | 4.19 | −2.441 | 0.015 |

| Female | 128 | 4.09 | 0.91 | 128 | 4.41 | |||||

| F5 Amenities | Male | 101 | 3.34 | 0.93 | −1.412 | 0.159 | 101 | 3.84 | −1.056 | 0.292 |

| Female | 129 | 3.52 | 1.02 | 128 | 3.95 | |||||

| F6 Safety and cleanliness | Male | 101 | 3.30 | 0.96 | −3.290 | 0.001 | 101 | 3.71 | −0.969 | 0.333 |

| Female | 129 | 3.72 | 0.98 | 128 | 3.81 | |||||

| Importance | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Until 19 | 20–29 | 30–39 | 40–49 | 50–59 | over 60 | F | Sig | |

| F1 Cultural content | Mean | 3.61 | 4.12 | 4.15 | 4.36 | 4.28 | 3.69 | 5.520 | 0.000 |

| St. Dev. | 0.88 | 0.65 | 0.70 | 0.47 | 0.61 | 0.69 | |||

| F2 Affordability | Mean | 3.31 | 3.80 | 3.77 | 3.77 | 3.83 | 4.58 | 2.330 | 0.043 |

| St. Dev. | 1.12 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.91 | 1.03 | 0.49 | |||

| F3 Convenience | Mean | 3.00 | 2.51 | 3.20 | 2.94 | 2.97 | 3.11 | 2.410 | 0.037 |

| St. Dev. | 1.18 | 1.20 | 1.24 | 1.19 | 1.16 | 0.91 | |||

| F4 Kindness | Mean | 3.67 | 3.98 | 4.04 | 4.07 | 4.19 | 4.22 | 1.369 | 0.237 |

| St. Dev. | 0.97 | 0.82 | 0.95 | 0.83 | 0.89 | 0.81 | |||

| F5 Amenities | Mean | 3.33 | 3.40 | 3.45 | 3.60 | 3.61 | 3.11 | 0.566 | 0.726 |

| St. Dev. | 1.06 | 0.91 | 0.88 | 1.13 | 1.09 | 1.26 | |||

| F6 Safety and cleanliness | Mean | 3.27 | 3.52 | 3.60 | 3.94 | 3.57 | 2.89 | 1.959 | 0.086 |

| St. Dev. | 1.01 | 0.99 | 0.86 | 0.87 | 1.00 | 1.60 | |||

| Performance | |||||||||

| Age | Until 19 | 20–29 | 30–39 | 40–49 | 50–59 | Over 60 | F | Sig | |

| F1 Cultural content | Mean | 3.68 | 4.27 | 4.35 | 4.29 | 4.45 | 4.28 | 4.276 | 0.001 |

| St. Dev. | 0.96 | 0.76 | 0.46 | 0.70 | 0.76 | 0.99 | |||

| F2 Affordability | Mean | 3.55 | 3.69 | 4.07 | 4.08 | 3.93 | 4.13 | 0.2.078 | 0.069 |

| St. Dev. | 0.92 | 0.94 | 0.93 | 0.83 | 0.94 | 1.08 | |||

| F3 Convenience | Mean | 3.47 | 3.57 | 3.52 | 3.74 | 3.43 | 3.78 | 0.444 | 0.817 |

| St. Dev. | 0.87 | 0.82 | 0.88 | 1.11 | 1.19 | 1.19 | |||

| F4 Kindness | Mean | 4.08 | 4.37 | 4.41 | 4.35 | 4.19 | 4.56 | 1.381 | 0.233 |

| St. Dev. | 0.86 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.72 | 0.58 | |||

| F5 Amenities | Mean | 3.49 | 4.01 | 3.98 | 4.00 | 3.94 | 3.28 | 3.084 | 0.010 |

| St. Dev. | 0.93 | 0.67 | 0.91 | 0.84 | 0.71 | 0.77 | |||

| F6 Safety and cleanliness | Mean | 3.62 | 3.76 | 3.72 | 4.06 | 3.87 | 3.11 | 1.942 | 0.088 |

| St. Dev. | 1.04 | 0.72 | 0.83 | 0.69 | 0.68 | 0.89 | |||

| Importance | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Educational Attainment | Primary Education | Secondary Education | Higher Education | Higher Education (University) | F | Sig | |

| F1 Cultural content | Mean | 3.00 | 3.99 | 4.13 | 4.23 | 11.152 | 0.000 |

| St. Dev. | 0.80 | 0.68 | 0.64 | 0.65 | |||

| F2 Affordability | Mean | 2.73 | 3.82 | 3.85 | 3.75 | 3.984 | 0.009 |

| St. Dev. | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.90 | 0.99 | |||

| F3 Convenience | Mean | 2.80 | 2.88 | 2.89 | 2.75 | 0.231 | 0.874 |

| St. Dev. | 1.14 | 1.15 | 1.23 | 1.25 | |||

| F4 Kindness | Mean | 3.33 | 4.09 | 4.14 | 3.92 | 2.881 | 0.037 |

| St. Dev. | 1.01 | 0.78 | 0.72 | 0.95 | |||

| F5 Amenities | Mean | 2.67 | 3.62 | 3.45 | 3.41 | 2.842 | 0.039 |

| St. Dev. | 0.82 | 0.94 | 0.95 | 1.01 | |||

| F6 Safety and cleanliness | Mean | 2.87 | 3.40 | 3.59 | 3.65 | 2.531 | 0.058 |

| St. Dev. | 0.69 | 1.01 | 1.02 | 0.97 | |||

| Performance | |||||||

| Educational Attainment | Primary Education | Secondary Education | Higher Education | Higher Education (University) | F | Sig | |

| F1 Cultural content | Mean | 3.25 | 4.18 | 4.26 | 4.33 | 6.343 | 0.000 |

| St. Dev. | 1.19 | 0.68 | 0.66 | 0.78 | |||

| F2 Affordability | Mean | 3.15 | 3.79 | 3.98 | 3.84 | 2.211 | 0.088 |

| St. Dev. | 0.38 | 0.99 | 0.81 | 0.97 | |||

| F3 Convenience | Mean | 3.20 | 3.66 | 3.62 | 3.50 | 0.953 | 0.416 |

| St. Dev. | 0.67 | 0.92 | 1.07 | 0.90 | |||

| F4 Kindness | Mean | 3.97 | 4.29 | 4.37 | 4.33 | 1.015 | 0.387 |

| St. Dev. | 0.66 | 0.77 | 0.54 | 0.69 | |||

| F5 Amenities | Mean | 3.13 | 3.94 | 3.93 | 3.93 | 3.319 | 0.021 |

| St. Dev. | 0.88 | 0.79 | 0.74 | 0.80 | |||

| F6 Safety and cleanliness | Mean | 3.27 | 3.71 | 4.03 | 3.74 | 3.138 | 0.026 |

| St. Dev. | 1.20 | 0.86 | 0.69 | 0.74 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bratić, M.; Pavlović, D.; Kovačić, S.; Pivac, T.; Marić Stanković, A.; Vujičić, M.D.; Anđelković, Ž. An IPA Analysis of Tourist Perception and Satisfaction with Nisville Jazz Festival Service Quality. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9616. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16229616

Bratić M, Pavlović D, Kovačić S, Pivac T, Marić Stanković A, Vujičić MD, Anđelković Ž. An IPA Analysis of Tourist Perception and Satisfaction with Nisville Jazz Festival Service Quality. Sustainability. 2024; 16(22):9616. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16229616

Chicago/Turabian StyleBratić, Marija, Danijel Pavlović, Sanja Kovačić, Tatjana Pivac, Anđelina Marić Stanković, Miroslav D. Vujičić, and Željko Anđelković. 2024. "An IPA Analysis of Tourist Perception and Satisfaction with Nisville Jazz Festival Service Quality" Sustainability 16, no. 22: 9616. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16229616

APA StyleBratić, M., Pavlović, D., Kovačić, S., Pivac, T., Marić Stanković, A., Vujičić, M. D., & Anđelković, Ž. (2024). An IPA Analysis of Tourist Perception and Satisfaction with Nisville Jazz Festival Service Quality. Sustainability, 16(22), 9616. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16229616

_Li.png)