Abstract

Historical thinking plays a key role in the education of critical citizens who are committed to the world in which they live. Socio-cultural sustainability promotes respect for one’s own cultural roots (and those of others), averts the consequences of cultural homogenisation and fosters identification with fundamental values and human rights. The main objective of this study is to analyse the consistency between the perception of teaching–learning processes and the historical knowledge of secondary school students following the implementation of a teaching unit based on the methodological theory of historical thinking. A quasi-experimental design with a non-equivalent control group was applied to 93 baccalaureate students (16–18 years of age) from the Region of Murcia (Spain). Two teaching units with different methodologies (experimental and control) were developed and compared. The results show a moderate degree of consistency between perceptions and knowledge in some variables in the analysis of the experimental group. Thus, it can be stated that historical thinking as a methodological theory contributes to promoting the idea of multiculturalism and has good academic results in terms of historical learning. In conclusion, the role of historical thinking as an influential factor in the perception and acquisition of knowledge is clear. In addition, it helps to preserve socio-cultural sustainability via community participation, the promotion of social justice and respect for other cultures.

1. Introduction

The 21st century should aspire to become the century of education for life due to the emergence of the critical curriculum, which is committed to the development and education of citizens who think, are capable of solving social and cultural problems, are emotionally engaged and are respectful of history. International curriculums today have a greater influence on this issue than they did 50 years ago. It is becoming increasingly common to carry out work in the classroom on skills that problematise social and cultural content, teaching students to think independently, to engage with other people’s opinions, to understand other cultures and forms of expression and to focus on global concerns or key issues of public life, such as the lack of protection of heritage, climate change, gender prejudice, discrimination, the isolation of minorities and belief in dogmas imposed from above [1].

The concept of sustainability has been discussed from different perspectives. Vallance et al. [2] advocate a three-pronged approach involving the following aspects: ‘development sustainability’, focusing on basic needs, the creation of social capital, justice, etc.; ‘bridge sustainability’, which involves changes in people’s behaviour to achieve biophysical environmental goals; and ‘maintenance sustainability’, which refers to socio-cultural preservation.

Along these lines, two decades ago, Sachs [3] introduced the concept of social sustainability, which he defined as education based on the fundamental values of equality and democracy, including respect for human rights, via civil, political, social, economic and cultural education. He also stressed its relationship with cultural sustainability, which involves balancing social change from within, in institutional and preventive terms.

Socio-cultural sustainability must invest in a model of citizen education that respects multiculturalism and teaches civic-mindedness, dialogue, respect and good practices that benefit society. In this regard, multiculturalism as an element of sustainability refers to the capacity of a society or community to maintain and preserve cultural diversity as an integral part of its sustainable development. By embracing multiculturalism in education and in public life, a richness is created that aims, over time, to build a more inclusive, fairer and more resilient society.

Historical thinking as a methodological theory, based on the postulates of its English-speaking proponents [4], has a crucial role to play in leading younger generations to determine socio-cultural sustainability by teaching them to understand and value the history and culture of their societies. This model of education forestalls cultural homogenisation and the acritical acceptance of dominant cultures that threaten respect for diversity and extol prejudices based on identity. Thus, interpreting the lessons of the past encourages an analysis that enables today’s societies to learn from the mistakes that have been so detrimental to the evolution of society and culture, promoting a historical perspective that analyses and understands these historical contexts and improves sustainability in the medium term [5].

This paper presents a model of classroom work that enables students to learn about the past through historical competences, as a preliminary step to educating young people in civic engagement, heritage protection, intercultural dialogue, empathy and respect for those who are different. These are the fundamental signs of socio-cultural preservation. Based on this methodological approach, the following research question is posed:

Is there coherence between secondary school students’ perceptions of the teaching–learning processes and the historical knowledge they possess depending on the methodology employed?

This contribution seeks to answer this question through the study of a case in the Region of Murcia (Spain) in which two teaching methodologies are compared in order to highlight the qualities and benefits of historical thinking as a methodology and a factor for social and cultural improvement.

2. Review of the Literature

2.1. Socio-Cultural Sustainability: A Vision of Global Citizenship

The concept of socio-cultural sustainability is understood here to be the process of preserving and strengthening the identities, traditions and social relations of a community, ensuring that all its members have access to culture and actively participate in its development. In social and cultural terms, education and its teaching processes are crucial in this regard as they influence the future development of human capital, a key element for the sustainable development and social and economic progress of societies [6]. As stated by Keitumetse [7], people inhabit and modify their environments through socio-cultural and psychosocial behaviours and processes, in such a way that the adoption of cultural competences will have its continuity in intellectual education. In this sense, the knowledge acquired in educational institutions becomes one of the most important factors in the quest for social harmony [8]. Issues such as cultural heritage, respect for multiculturalism and the adoption of social strategies and skills in the teaching of history are key issues that should define the learning process. With regard to heritage, for example, it is essential that strategies be designed which facilitate collaboration between museums and schools, with the aim of using the former as a learning resource in the classroom, functioning as a repository of valuable artefacts upon which activities can be developed to build collaborative learning projects [9]. Indeed, approaching the issue of heritage at school (specifically in the area of social sciences) can be a valuable teaching resource, either as part of the curriculum, attributing importance to it in textbooks, or via its presence in teaching and learning processes in educational materials and cultural policies in overall terms [10].

The teaching of the social sciences must be based on a global commitment. In the current socio-cultural context, a comprehensive and multicultural educational strategy must be pursued, even if it is situated in a local context [11]. When this is achieved, teachers must also do their bit, in such a way that teaching processes can be developed that take into account the pursuit of sustainable development goals, more particularly in this case quality education. To this end, intercultural research can and must promote more sustainable and educational practices [12].

Based on the above, socio-cultural teaching has long been justified via the social studies education approach, which emerged at the turn of the 20th century, due largely to the role of the National Education Association (NEA) and the Social Studies Committee [13]. Since its expansion, this approach, which gathers research on issues-centred social studies teaching, has been adopted by other countries, although it may be expressed in different ways or from different perspectives. One example concerns the teaching of controversial issues, typical in English-speaking countries [14,15,16], or the “questions socialment vives” of the French-speaking world [17,18,19,20]. Such issues are defined as open debates within society and its points of reference in terms of knowledge [19]. This approach to teaching has also been analysed as an approach to socio-scientific issues or problems [21,22] and as an approach to burning social conflicts [23]. In Spain, this approach is relatively recent, as it has been employed (mainly in secondary education) as a result of the actions of groups advocating the educational reform that emerged in the final decades of the 20th century, such as Germanía 75, Llavors, Garbí, Aula Sete, Cronos, Gea-Clío, Asklepios, etc. [24].

In recent decades, curriculums have gradually adopted a more modern approach to history, incorporating the methodology and teaching of the historical method as a mediating element, since it encourages creative and critical thinking and the development of historical thinking skills [25]. Along these lines, history education today has advanced and become more innovative in terms of fostering critical, reflective and creative thinking. The teaching of the social sciences (not only history) now encourages decision-making in relation to socio-political problems and circumstances [26]. In other words, as Benejam [27] states, education should enable students to play an active role in society and to be able to find their vision of the future, developing a socially and culturally committed attitude. Indeed, controversy fosters critical awareness, favours the reasoned construction of opinions and judgements, promotes discrepancy and, ultimately, links conflicts and the complexity of the world with the knowledge learned at school [16]. This, in the words of Eulie [28], constitutes the heart of democracy. This is what socio-cultural sustainability, advocated in this paper, is all about; a commitment to rigorous educational processes and the teaching of history via building bridges, whilst not neglecting the critical nature of knowledge, heritage education, respect for multicultural contexts or learning to manage controversial issues that connect the past with the present and define the future.

2.2. Thinking History: Emerging Competences

In order to investigate the complex scenario described above and to promote the education and shaping of knowledgeable young people committed to the world in which they live, social and cultural empowerment is essential. In this process, one of the most important aims of history teaching is to instil historical thinking skills in students, in addition to problematising this subject as a basis for critical knowledge grounded in reflection.

Society achieves historical consciousness as a result of its cultural development, the intercultural contact between its people or the education they receive. However, this trend, popularised by authors such as Rüsen [29,30,31,32] and Körver [33,34], among others, has received criticism for being an absurdly Eurocentric model of progress, in which Western culture possesses historical consciousness while the rest of the world does not until Western models of understanding are attained [35]. For this reason, in the final decades of the 20th century, and thanks to the influence of Dickinson [36,37,38], the way was paved for the appearance of a new conception of historical thinking in the first quarter of the 21st century. This was achieved under the guidance of the Centre for the Study of Historical Consciousness and the History Assessments of Thinking (HATs) and, above all, thanks to the theories of Seixas and Morton [4,5], which were taken up in the English-speaking world by authors such as Wineburg [39,40] and Levésque [41,42], among others.

This research trend argues that for students to be socio-culturally competent, it is essential that they learn about the past using the skills traditionally employed by historians. Indeed, as Kitson et al. [43] argue, there would be little to understand and enjoy of the world if we were not able to interpret it with historical perspective and critical thinking or if we did not possess other qualities that are essential to culture and life in society. These factors of historical thinking, upon which younger generations should be educated, are understood as the following: the ability to reflect on what is important to study from the past and how this selection process is carried out (historical significance); the use of sources as historical evidence on which societies have been built (historical evidence); the ability to identify advances and setbacks in the course of history, to reflect on the impact of historical changes or on the commemoration of continuities in the form of rites and festivities (change and continuity); the art of combining events and their implicit historical processes through the justification of causal discourse (causes and consequences); the ability of adolescent students to learn about history by their being situated in critical multicultural positions, in which they have to take a standpoint from multiple past contexts (historical perspective); and the rigour to judge past actions from culturally and socially sustainable points of view, according to ethical models of conduct (ethical dimension) [4].

Based on the well-perceived studies by Gómez et al. [44,45] and Rodríguez-Medina et al. [46] in which teaching units based on these historical thinking skills were implemented, involving changes in teaching methodology, a study was carried out with a teaching programme based on historical competences in order to subsequently analyse baccalaureate students’ perceptions and historical knowledge. The results showed that the methodology based on historical thinking skills not only increased students’ motivation, satisfaction and perceived transfer of historical knowledge, but also improved levels of historical knowledge, according to a controlled assessment test [47].

This research complements the above studies but aims to go a step further. To do so, it analyses whether or not students’ perceptions determine their historical knowledge, looking in depth at the consistency between what they think and their academic results, depending on whether or not they receive an education based on historical thinking skills as a factor that can be extrapolated to social and cultural sustainability behaviour.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Objectives of the Research

The general objective of this research is to study the coherence between the perception of history classes and the historical knowledge of secondary school students after the application of a programme based on the theory of historical thinking as a socio-cultural factor. This general objective can be broken down into the following specific objectives:

- To analyse the degree of consistency between perceptions of the teaching–learning process and the degree of knowledge of baccalaureate students in the experimental group, on an overall level and according to sex.

- To analyse the degree of consistency between the perception of the teaching–learning process and the degree of knowledge in baccalaureate students in the control group, at an overall level and according to sex.

- To analyse the degree of consistency between the factors of historical thinking as a reason for socio-cultural sustainability.

3.2. Design and Participants

In order to respond to the objectives set, a research design with a quantitative approach was chosen. Specifically, a design with pretest and posttest and control group was used [48]. This may also be termed a semi-experimental design with pretest–posttest and non-equivalent groups [49]. According to this design, the subjects receive a pretest at the same time. Then, one of the two groups receives the experimental treatment while the other does not (control group). Finally, the posttest is also administered to both groups at the same time [48]. The main feature of this design is that both receive a pretest and a posttest but they do not have pre-experimental sampling equivalence. Rather, the groups are made up of natural entities; in this case, intact classes [50]. Initially, an evaluative survey and a written assessment test were administered. Then, the consistency or range of correlation between the degree of the students’ perceptions of the teaching of history and the actual knowledge acquired was analysed in both groups, in accordance with the results of the posttest of both tests, with the aim of seeking a descriptive and comparative purpose. The research was planned in good time and was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Murcia (Spain).

As for the participants, although the initial plan was for 100 secondary school students to take part, the final useful sample was 93 Spanish adolescents enrolled in three secondary schools in the Region of Murcia (Spain), specifically in the first year of the baccalaureate (16–17 years old). Five intact classes were selected, two of which constituted the experimental group (34 participants) and three the control group (59 participants). All of the students participated in this study on a voluntary basis.

3.3. Training Process and Socio-Cultural Mediation

The teaching process consisted of an eight-session teaching unit with both groups, related to the subject of the Second World War. In the control group, a traditional teaching model (non-treatment) was followed, based on the use of the textbook, note-taking, diagrams, copying activities; in short, rote learning. The experimental group, on the other hand, studied the same topic but incorporated a teaching process based on historical competences as a driving factor for issues related to socio-cultural coexistence, the development of social values and reflective and critical thinking. Furthermore, in this group, students were encouraged to work with historical and heritage sources, research strategies, group dynamics, empathetic didactic challenges, complex debates and multicultural practical assumptions. In other words, a working model with a markedly social, cultural and historical character was employed.

Given the fallible nature of science, mastering epistemology and developing a teaching and learning process based on criticism and reflective argumentation enables students to question their own learning, rethink their knowledge and understand that history should not be understood as finished and buried knowledge, but as learning that can be updated, that influences people’s personality and builds citizens capable of giving a more democratic response to society. The research plan was designed with this perspective in mind, following a critical and interpretative, historicist view of the past. In addition, quality historical content was offered, adjusted to the reality of the conflict and including the most recent advances and discoveries.

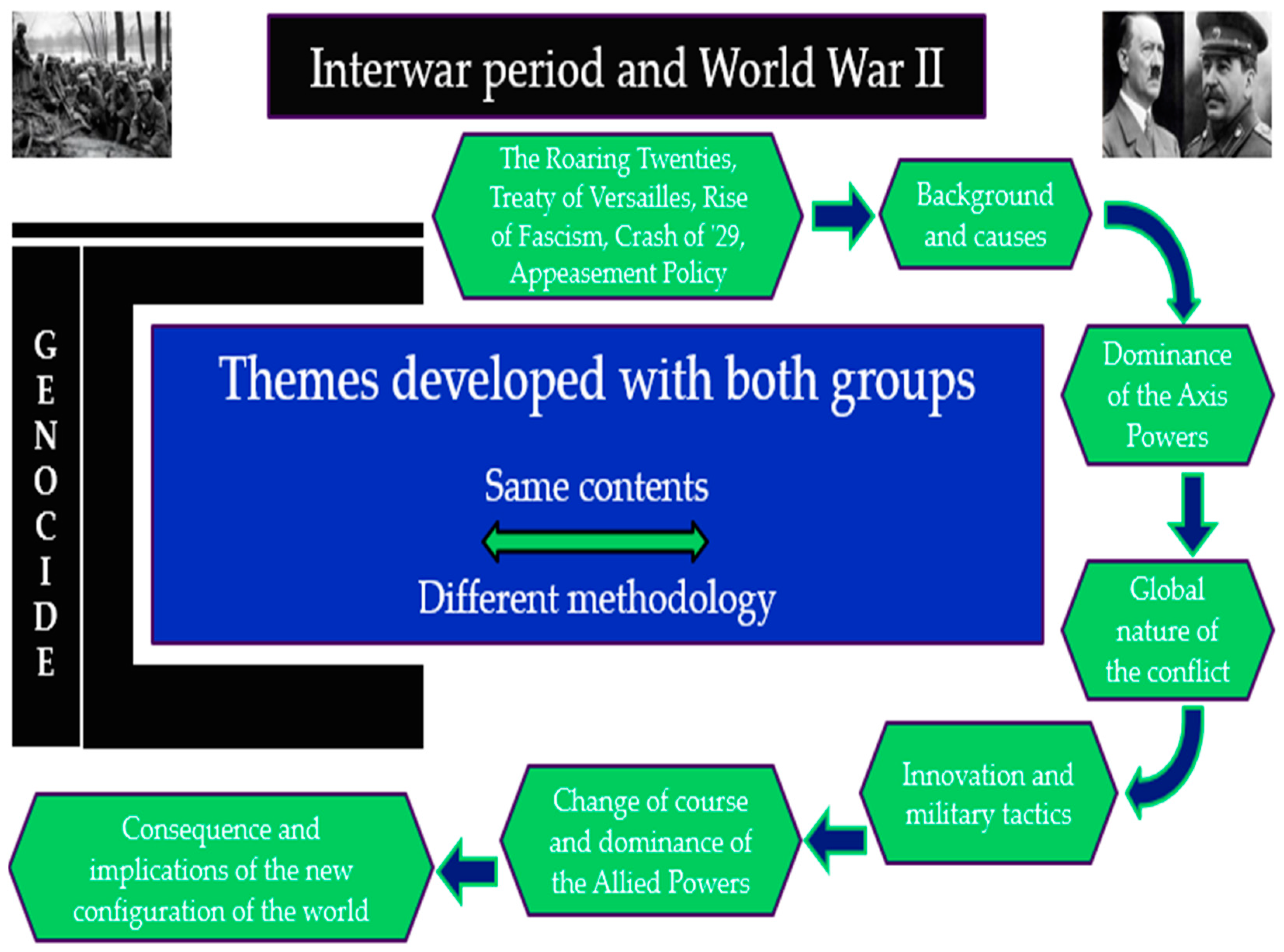

Figure 1 shows the thematic issues addressed by the two groups during the training sessions.

Figure 1.

Content taught to both groups in the teaching unit.

The figure outlines the main events addressed in the teaching–learning process: the inter-war period, Nazi Germany’s initial victories (1939–1942), the Allied turning of the tide (1942–1945), innovations, military tactics, the Holocaust and the economic, social, cultural and territorial consequences of the War.

To clarify the approach employed with the experimental group, Table 1 presents the socio-cultural intervention factors, articulated around the six historical thinking skills [4].

Table 1.

Historical skills as a factor of socio-cultural intervention.

Table 1 shows that the socio-cultural work enabled the students in this group to appreciate diversity as something of value, built on respect, tolerance and dialogue between cultures, transcending ideas. Thus, the work on historical empathy enabled them to adopt complex roles, learning to reflect from multiple contexts on what guided the decision-making processes of the main characters of the War. Other examples can be found in the study of identities and respect for cultural roots, developed through iconographic analysis to recognise and value historical changes and cultural permanence, or in the construction of posters and evaluative infographics on the genocide carried out by Nazi Germany. To this end, visual representations of the period were analysed through different sources such as photographs, propaganda posters, works of art and visual documents that define diverse cultural contexts, such as the Holocaust, the resistance movements in Europe or the colonial forces in the conflict, from comparative frameworks.

3.4. Instruments

For this section, it is important to differentiate between the instrument used to analyse the students’ perceptions on the one hand and the instrument used to assess their knowledge on the other.

In relation to the analysis of the degree of perception, from which the mean values of the four rating variables (methodology, motivation, satisfaction, and effectiveness and transfer) used in the subsequent consistency analysis were calculated, both versions (pretest and posttest) of the Perception of Secondary Education Students (PALUSE in its Spanish acronym) questionnaire were used. In order to be able to make use of this instrument, an adaptation and revalidation of its original version was carried out [46]. This provided extremely good empirical results in terms of internal consistency with a reliability of 0.896 (pretest) and 0.918 (posttest). Its construct validity was excellent [51], with a Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) fit index of 0.802 in the pretest and 0.885 in the posttest and a factor structure with principal component analysis in which 69.64% of the variance in the pretest was explained by nine factors. In the posttest, 72.28% of the variance was explained by seven factors. This questionnaire begins with an introductory and presentation section, followed by a series of nominal independent variables. Its main section consists of a Likert scale with five possible options that express the participants’ degree of agreement, from 1 to 5. It ends with a section of remarks and a final acknowledgement of gratitude.

As far as the instrument for assessing the participants’ historical knowledge is concerned, a written test for assessing historical knowledge, called the Evaluation on the Second World War (ESEGMU in its Spanish acronym), was designed from scratch, consisting of multiple-choice and open-ended questions. As Rodríguez [52] states, open-response tests have the advantage of being able to assess the subject’s ability to organise ideas and integrate different sources of information, while measuring the student’s creativity and learning about their judgements, among other factors. In its validation process, this test was trialled in a pilot study of 20 students in order to ascertain how and to what degree its dimensions provided a good fit to the objective of the test. In this stage, any items or questions that did not work were eliminated or modified. This process was complemented by a focus group of five university experts and secondary school teachers in which the suitability of the test was assessed, improvements were discussed and its content was finalised. The test begins with an introductory section, followed by the main part, which is divided into two blocks: firstly, a section with identification data, and secondly, a section with three dimensions that aim to measure the participants’ degree of historical knowledge regarding the Second World War. The first of the three dimensions consists of ten items, nine of which are multiple-choice items, with one open-response item on the Holocaust. The second dimension assesses the interpretation of an image from the Yalta Conference via a visual thinking task showing the main historical characters of the War. The third dimension is a narrative about the significance of the Second World War for the history of humankind in which students could demonstrate their historical knowledge as well as their ability to think historically and to understand the socio-cultural problems arising from this conflict. The calculation of the mean values of this test would later make it possible for a comparative correlation to be established with the rest of the variables analysed from the perception instrument.

4. Results

In order to achieve the proposed research objectives, the consistency between the different variables (four related to perception and one linked to knowledge) was analysed using Spearman’s rho correlation coefficient, which is used when the variables to be analysed are ordinal [53]. The procedure consisted of obtaining the mean values of the dependent variables and then establishing a categorised grouping for each block. The knowledge block had to be previously transformed into a discrete variable in order to carry out the analysis.

4.1. Objective 1

In order to analyse the degree of consistency between the perception of the teaching and learning process and the degree of knowledge, first of all, the mean values of the five dependent variables presented were calculated: the four analysing the students’ perceptions (methodology, motivation, satisfaction, and effectiveness and transfer of historical thinking), in evaluative terms, and the variable concerning historical knowledge, derived from the scores of the assessment test described above. Subsequently, the correlation among all of them was calculated (Table 2).

Table 2.

Relationship between the perceptions and the degree of knowledge of the experimental group on an overall level.

With reference to Table 2, the overall analysis shows a positive and significant correlation between the motivation rating and the satisfaction rating regarding the teaching and learning process (r = 0.64; p < 0.001), as well as in the rating between motivation and the effectiveness and transfer of learning historical competences (hereafter, effectiveness and transfer) (r = 0.63; p < 0.001). Similarly, the satisfaction variable relates in a highly positively way to the effectiveness and transfer variable (r = 0.71; p < 0.001). Therefore, there is consistency between three of the four variables related to perception, but not with regard to the knowledge variable. These results are supported by the proposals of several authors [54,55] who consider that this coefficient should range between −1 (negative perfect relationship) and 1 (positive perfect relationship). An absence of a relationship, therefore, would be a value close to 0. Likewise, other authors have stated that a positive correlation higher than 0.50 [56] or 0.70 [57] can be considered to be high.

As far as sex is concerned, Table 3 presents the correlational analysis between the five dependent variables analysed.

Table 3.

Relationship between perception and level of knowledge in the experimental group according to sex.

With regard to males, the motivation variable correlates positively and significantly with the effectiveness and transfer variable (r = 0.55; p < 0.05), while the latter correlates with the satisfaction variable (r = 0.58; p < 0.05). In the analysis of the female group, there is a relationship between motivation and the satisfaction (r = 0.86; p < 0.001) and effectiveness and transfer (r = 0.74; p = 0.001) variables, and a high degree of consistency is also found between the variables of satisfaction and effectiveness and transfer (r = 0.87; p < 0.001). These results make it possible to state that in the female group, the number of significant correlations is somewhat higher (three) than in the case of males (two). What is more, these relationships have a higher degree of consistency, with a level of significance of less than 0.01 (bilateral).

Likewise, an analysis was also carried out with certain categories of some of the variables analysed in this study in an attempt to verify whether there were new relationships of consistency between perception and knowledge, according to the independent variable ‘sex’. For this purpose, reference is made in this section to the grouping of the participants in the experimental group according to the categorisation of knowledge into pass and fail grades (knowledge, new categorisation). In this analysis, the results do not reveal any relationships with respect to the knowledge variable in males. However, there is consistency with respect to females, as shown in the crossing of variables in Table 4.

Table 4.

Relationship between the perception of the teaching and the degree of knowledge of the experimental group, according to the categorisation of pass and fail grades among females.

According to Table 4, the analysis derived from grouping the knowledge variable into pass and fail grades (new categorisation) shows a moderately positive and statistically significant correlation between the satisfaction and the knowledge variables (r = 0.51; p < 0.05) [57], in addition to the three relationships that have already been described above between the variables of the teaching perception dimension (Table 3).

4.2. Objective 2

As for the analysis of the degree of consistency between the responses of the control group in the five variables under study, the mean of these blocks of variables was also calculated in order to enable correlation, as presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Relationship between perception and level of knowledge of the control group on an overall level.

As shown in Table 5, in the analysis derived from the responses of the control group, there is a weak positive and significant relationship between the methodology variable and the motivation variable (r = 0.42; p = 0.001) and an even weaker one between the methodology and the effectiveness and transfer variables (r = 0.31; p < 0.05). Cohen [56] established that a correlation of 0.30 is equivalent to an average or typical effect, while if it rises to 0.50, the effect is greater than average. On the other hand, consistency increases in the motivation variable when correlated with satisfaction (r = 0.65; p = 0.000) and effectiveness and transfer (r = 0.71; p = 0.000). This is also the case in the correlation between the satisfaction and effectiveness and transfer variables (r = 0.58; p = 0.000), which is below the significance level of 0.01 (bilateral). Mateo [57] points out that a correlation between 0.40 and 0.70 is moderate, while anything exceeding 0.70 is high. These results make it possible to affirm the existence of positive correlations and, therefore, consistency, between four of the five dependent variables analysed in this group, the highest correlations being between the motivation, satisfaction, and effectiveness and transfer variables.

Breaking this analysis down in terms of sex, Table 6 shows the correlation between the four rating variables and the knowledge variable, according to the responses of males and females in the control group.

Table 6.

Relationship between perception and level of knowledge of the control group according to sex.

According to Table 6, in the male group, there is a high degree of consistency, with positive and significant correlations between the motivation and the satisfaction variables (r = 0.78; p = 0.000), between the motivation and the effectiveness and transfer variables (r = 0.84; p = 0.000) and between the latter and the satisfaction variable (r = 0.62; p = 0.001). On the other hand, consistency decreases slightly in the female group, although it remains at moderate levels [57]. The methodology variable correlates positively and significantly with the motivation variable (r = 0.49; p < 0.01), the motivation variable with the satisfaction variable (r = 0.54; p = 0.001) and with the effectiveness and transfer variable (r = 0.62; p = 0.000), while the latter correlates positively and significantly with the satisfaction variable (r = 0.56; p = 0.001).

Therefore, the rank coefficient data indicate that the number of significant correlations is slightly higher in females (four) than in males (three), with the degree of consistency of their relationships being moderate. For males, on the other hand, it remains at high values, with a significance of 0.01 (bilateral) in both groups. As with the analysis of the experimental group, where relationships of consistency were found (in females), correlation was also calculated for the control group by grouping the knowledge variable in the categories of pass and fail grades. However, no relationships were found between the assessment variables and the grouped knowledge variable.

4.3. Objective 3

In order to respond to this objective, which refers to the calculation of the degree of consistency between the students’ perceptions of the historical thinking factors as a reason for socio-cultural sustainability, the effectiveness and transfer variable was broken down, extracting the scores on those items based on historical thinking that relate to respect for multiculturalism and the value of human relationships. Subsequently, the rank correlation coefficient was also calculated to measure the possible consistency between the values of these factors in both groups. These results are presented in Table 7.

Table 7.

Relationship between the perception of historical thinking factors as a reason for socio-cultural sustainability in the experimental group.

As shown in Table 7, as far as the experimental group is concerned, the items based on historical competences derived from this construct correlate significantly with each other 20 times with a medium (typical), moderate or high effect size [56,57]. However, for reasons of space, only the highest consistency indices will be described here. In this case, item 1, referring to the learning attained in the teaching process regarding historical facts, correlates highly and significantly with item 2, which focuses on learning about the main historical figures (r = 0.771; p = 0.000), and with item 3, which concerns the work performed on chronology in the class sessions (r = 0.728; p = 0.000). This item, in turn, maintains a high degree of consistency with item 2 defined above (r = 0.671; p = 0.000) and with item 4, the historical thinking factor that focuses on the use of historical sources to understand the past from its multicultural context (r = 0.616; p = 0.000). Finally, it is striking in this group that item 9, which addresses how classroom sessions help to increase respect for people from other cultures or who may have opposing views, has a consistent relationship with item 10, which describes the impact of the topic sessions in helping students to understand and discuss current issues of interest (r = 0.625; p = 0.000). Evidently, the relationships described, with an effect close to or above 0.70, are based on Mateo’s [57] thesis that between 0.40 and 0.70, the relationship is moderate, while it is high if these values are exceeded.

With the degree of consistency obtained in the responses of the experimental group having been described, Table 8 presents the relationships derived from the analysis carried out with the control group.

Table 8.

Relationship between the perception of historical thinking factors as a reason for socio-cultural sustainability in the control group.

There are 44 relationships between the different items analysed for which the effect size is medium (typical) or higher (r > 0.30), in accordance with Cohen [56]. Of these, as in the experimental group, those with a moderate or high effect above 0.60 are described here [57]. In the first place, the highest consistency relationship is observed between items 1 and 2 (r = 0.813; p = 0.000), which address learning about historical facts and characters, respectively. Other relationships of a moderate nature occur significantly between items 1 and 5 (r = 0.607; p = 0.000), which deal with learning about changes and continuities in history, and between items 1 and 6 (r = 0.689; p = 0.000), which focus on learning about causes and consequences in history classes. Also worthy of note is the degree of consistency of item 4, on the use of sources to learn about the past, with item 8 (r = 0.647; p = 0.000), which deals with the appreciation of the cultural heritage of the environment, and with item 10 (r = 0.601; p = 0.000), related to an improvement in the understanding and discussion of current issues. Item 5, which focuses on the identification of processes of historical change and continuity, is related to item 6, which explains how to develop historical narratives by connecting causes and consequences (r = 0.668; p = 0.000). The latter, in turn, fits with item 7, which refers to the critical appraisal of the past, i.e., how students learn to reflect on and evaluate the reasons why historical figures acted in a certain way (r = 0.680; p = 0.000). Finally, the same item (item 7) shows a remarkable correlation effect with item 8, which describes how students are able to evaluate common heritage more positively (r = 0.607; p = 0.000), and with item 10, which justifies the extent to which the subject studied is able to prepare the student to understand and debate current issues (r = 0.613; p = 0.000).

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Secondary school classrooms bear direct witness to a lack of political and civic literacy among young people, which, on many occasions, even highlights a socio-cultural education based on prejudices and stereotypes, far removed from any hint of epistemological reflection [58]. This paper has attempted to overturn this situation via a commitment to teaching and learning processes in history that focus on culture, respect for heritage, the development of social skills, the promotion of empathy, critical thinking and the ability to contrast historical information and assume different ways of thinking.

To put this study into context, it is important to complement it with results from a previous paper [47] in which other variables were analysed, providing better scores for the experimental group in terms of perception, as well as a substantial improvement in knowledge in comparison with the control group. However, further steps were required in this direction. For this reason, this paper aimed to understand whether or not these perception values shown by the students determined their knowledge as this would make it possible to discern whether or not what they think corresponds to their actual learning levels and to the different historical thinking variables. Therefore, based on the established objectives, the consistency between the young people’s perceptions of the teaching and learning process and the degree of knowledge they obtain has been analysed, using Spearman’s rho correlation coefficient in order to verify whether there are relationships between the five variables involved.

As for the experimental group, the analysis revealed a positive and significant relationship between the motivation, satisfaction, and effectiveness and transfer of historical thinking variables. This relationship of dependence is due to the fact that they influence each other; in other words, the perception found in each of the variables positively influences the assessment made of the others. On examining this relationship in greater depth in terms of sex, it can be observed that in the analysis of female participants, there is a higher consistency, with a high degree of dependence between these three variables. However, in the case of the male subjects, this dependence is reduced to the correlation between motivation and the effectiveness and transfer variable and between the latter and the satisfaction variable. This means that, for males, having greater motivation in some areas, such as motivation to learn and making an effort in class, does not imply that they feel more satisfied in other tasks, such as group work. Likewise, after the subjects were classified into pass and fail grades, a moderately positive and statistically significant correlation between the satisfaction variable and the knowledge variable was found among female participants [57], in addition to the other described relationships of dependence. This means that the general satisfaction shown by this group has an influence on the number of pass or fail grades and, therefore, on the degree of knowledge obtained.

In the analysis of consistency in the control group, a positive and significant relationship was found between the methodology variable and the motivation and effectiveness and transfer variables, albeit with a medium (typical) effect [56]. However, this relationship increases between the motivation and satisfaction variables, between the motivation and effectiveness and transfer variables and, finally, between the satisfaction and the effectiveness and transfer variables. In terms of sex, there is a similar consistency between male and female participants, which affects the relationship between the motivation, satisfaction, and effectiveness and transfer variables, being slightly lower in the female group. However, the female subjects also showed a moderate degree of consistency between the methodology and motivation variables. This would explain that their perception of the overuse of the textbook, the importance attributed to examinations, the lack of group work or debates, the absence of research or the scarce use of historical empathy or other socio-cultural tasks has a moderate influence on their degree of motivation.

Finally, breaking down the effectiveness and transfer of historical thinking variable and analysing its factors in relation to each other clarified how those views are related to socio-cultural issues, the sustainability of which is essential for the construction of a global citizenship which is more civilised, empathetic and respectful with other cultures. Thus, twice as many relationships of consistency were found in the results of the control group as in the experimental group. However, according to the established values [57], the experimental group had two relationships above the threshold considered as high (r = 0.070), compared to only one for the control group.

The fact that there are more consistent relationships in the control group could be precisely due to the fact that the neutral (and sometimes low) degree of perception shown by this group with regard to the historical thinking variables corresponds to the low value this group placed on socio-cultural sustainability. This may be the case taking into account how little this group worked on the values of citizenship, respect among equals, empathy in debates or the work of heritage as a common inheritance as they were taught in a traditional manner. In other words, this group was not able to interpret the relationship between historical thinking and the values of socio-cultural work. On the other hand, it is understandable that the experimental group did not show so many consistent relationships between variables. This could be explained by the fact that they are aware of which specific competences develop socio-cultural parameters. In other words, some historical thinking skills serve to foster attitudes of respect and tolerance, social empathy, appreciation of other cultures and a social perspective on history, which the students in the experimental group were able to identify. This could be explained by the prior work performed by this group during the class sessions, in which they learnt about these aspects in depth, based on the model proposed by Seixas and Morton [4].

In conclusion, according to the set of analyses and variables studied, it has been shown that, in the experimental group, the female subjects present a statistically significant correlation between what they think about the variables involved in the teaching and learning processes and the historical knowledge they possess, with a moderate effect size [57]. With the due caution that this issue requires, these findings could be explained by the difference in ratings given by the male and female participants (almost one point higher for females) [47]. This would justify the greater coherence between their perception and the grades obtained, although future studies will be required to determine whether this issue is confirmed or whether the relationship is the result of chance. In contrast, in the control group, no consistent relationship was observed between the students’ perceptions and their historical knowledge, which may be attributed to the traditional methodology employed.

The findings found justify that the development of historical thinking in the classroom seems to have an important value as a promoter of more democratic attitudes, based on respect, empathy or positive valuation of other cultures. The experimental group, which had previously worked on the competencies of historical thinking presented, was able to show more clearly and precisely the relationship with socio-cultural values, which may be indicative of the need to propose didactic approaches in classrooms that integrate this methodology in a definitive way, not only to facilitate the understanding of the past, but also to build a more civilised and socially committed citizenry.

In conclusion, it seems that the consistent relationships found in the variables analysed in both groups have a notorious impact on the way history is taught and learned, as well as on the relationships with the socio-cultural context. Undoubtedly, promoting global citizenship practices while teaching historical knowledge is better than not doing so, as they articulate significant connections between key concepts that allow working towards preserving a socio-cultural heritage from which new generations benefit, based on respect, tolerance and criticality through debates that generate links and reciprocities among themselves and also with other cultures or collectives.

At the beginning of the present paper, the research question was posed as to whether there is coherence or consistency between what secondary school students think about teaching and learning processes and the degree of historical knowledge they show, depending on the methodology applied. It is important to emphasise that the results found correspond to the responses of a specific group of students and, therefore, cannot be extrapolated to the population, but they represent a scientific advance that should be complemented with other studies of similar characteristics. For this reason, once all the variables of analysis have been analysed, it can be affirmed, with due caution, that the methodology implemented in the classroom, as well as the concepts, procedures and attitudes worked on, can exert a notable influence on young people’s way of thinking, even in terms of knowledge. However, certain socio-cultural factors of classroom work can only be developed (and be made visible) if teachers prioritise an alternative teaching model, putting aside traditional approaches based on memorisation and uncritical learning. In the future, it is necessary to continue to move towards educational options that promote social dialogue, tolerance and respect, active participation, work with sources and intercultural education. In such a way, future generations can be taught to think about history, and these thinking skills can be reinforced.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, A.L.-G. and P.M.-M.; methodology, A.L.-G.; software, A.L.-G.; validation, A.L.-G.; formal analysis, A.L.-G.; investigation, A.L.-G. and P.M.-M.; resources, A.L.-G. data curation, A.L.-G. and P.M.-M.; writing (original draft preparation), A.L.-G.; writing (review and editing), P.M.-M.; visualisation, A.L.-G. and P.M.-M.; supervision, P.M.-M.; project administration, P.M.-M.; funding acquisition, P.M.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This publication is a result of the research project “Teaching and learning of historical competencies in Baccalaureate: a challenge to achieve a critical and democratic citizenship” (PID2020-113453RB-100), funded by the Ministry of Science and Innovation and State Investigation Agency of Spain (MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033). The APC was funded by this same project.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Murcia (protocol code 2351/2019, 20 May 2019) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data are contained in the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants in the research for their support of this study, as well as the staff of the schools, for their willingness to contribute to the success of this work. The authors would also like to thank Paul Lacey for his review and translation of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Barton, K.C.; Ho, L.-C. Curriculum for Justice and Harmony: Deliberation, Knowledge, and Action in Social and Civic Education; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallance, S.; Perkins, H.C.; Dixon, J.E. What is social sustainability? A clarification of concepts. Geoforum 2011, 42, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, I. Social sustainability and whole development: Exploring the dimension of Sustainable Development. In Sustainability and the Social Sciences: A Cross-Disciplinary Approach to Integrating Environmental Considerations into Theoretical Reorientation; Becker, E., Jahn, T., Eds.; Zed Books: London, UK, 1999; pp. 25–36. [Google Scholar]

- Seixas, P.; Morton, T. The Big Six Historical Thinking Concepts; Nelson Education: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Seixas, P. A Model of Historical Thinking. Educ. Philos. Theory 2017, 49, 593–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlasov, M.; Polbitsyn, S.N.; Olumekor, M.; Haddad, H. Exploring the Role of Socio-Cultural Factors on the Development of Human Capital in Multi-Ethnic Regions. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keitumetse, S.O. Cultural Resources as Sustainability Enablers: Towards a Community-Based Cultural Heritage Resources Management (COBACHREM) Model. Sustainability 2013, 6, 70–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlasov, M.; Polbitsyn, S.N.; Olumekor, M.; Oke, A. The Influence of Socio-Cultural Factors on Knowledge-Based Innovation and the Digital Economy. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex 2022, 8, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escribano-Miralles, A.; Serrano-Pastor, F.J.; Miralles-Martínez, P. The use of activities and resources in archaeological museums for the teaching of history in formal education. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Fuster, M.C.; Miralles-Martínez, P.; Serrano-Pastor, F.J. School trips and local heritage as a resource in primary education: Teachers’ perceptions. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carm, E. Rethinking Education for All. Sustainability 2013, 5, 3447–3472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchis-Giménez, L.; Tamarit, A.; Prado-Gascó, V.J.; Sánchez-Pujalte, L.; Díaz-Rodríguez, L. Psychosocial Risks in Non-University Teachers: A Comparative Study between Spain and Mexico on Their Occupational Health. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, A.E. El origen de los Estudios Sociales en el Currículo de Estados Unidos. REIDICS 2019, 5, 129–145. [Google Scholar]

- García, F. Ciudadanía participativa y trabajo en torno a problemas sociales y ambientales. In Una Mirada al Pasado y un Proyecto de Futuro: Investigación e Innovación en Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales; Pagés, A., Santisteban, A., Eds.; Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 2014; Volume 1, pp. 119–126. Available online: https://idus.us.es/handle/11441/26470 (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Pagès Blanch, J.; Santisteban, A.; Evans, R.W.; Tutiaux-Guillon, N.; Brusa, A.; Musci, E.; Funes, A.; López Facal, R.; Anguera Cerarols, C.; Gonzalez Valencia, G.; et al. Les Qüestions Socialment Vives i L’ensenyament de les Ciències Socials; Servei de Publicacions de la UAB: Barcelona, Spain, 2011; Available online: https://ddd.uab.cat/record/197111 (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Santisteban, A. La enseñanza de las ciencias sociales a partir de problemas sociales o temas controvertidos: Estado de la cuestión y resultados de una investigación. Futuro Pasado 2019, 10, 57–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpe, Y.; Barthes, A. De la question socialement vive à l’objet d’enseignement: Comment légitimer des savoirs incertains? Doss. Sci. L’éducation 2013, 29, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevallard, Y. Questions vives, savoirs moribonds: Le problème curriculaire aujourd’hui. In Proceedings of the Actes du Colloque Défendre et Transformer L’école Pour Tous, Université de Provence, Marseille, France, 3–5 October 1997; Available online: http://eloge-des-ses.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Chevallard-Questions-vives.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Legardez, A. L’enseignement des questions sociales et historiques, socialement vives. In Le Cartable de Clio; Heimberg, C., Ed.; Loisirs et Pédagogie: Lausanne, France, 2003; Volume 3, pp. 245–253. Available online: https://www.atistoria.ch/all-contents?task=download.send&id=298:le-cartable-de-clio-numero-3-2002&catid=98 (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Marquat, C.; Rafaitin, Y.; Diemer, A. Des Controversial Issues (CI) aux Questions Socialement Vives (QSV): Une clé d’entrée pour comprendre l’éducation au développement durable. Rev. Francoph. Développement Durable 2014, 4, 6–20. Available online: https://acortar.link/dLSk5C (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Hodson, D. Time for action: Science education for an alternative future. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2003, 25, 645–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeidler, D.L.; Sadler, T.D.; Simmons, M.L.; Howes, E.V. Beyond STS: A Research-Based Framework for Socioscientific Issues Education. Sci. Educ. 2005, 89, 357–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Facal, R.; Santidrián, V.M. Los «conflictos sociales candentes» en el aula. Íber Didáctica Cienc. Soc. Geogr. Hist. 2011, 69, 8–20. Available online: https://acortar.link/AJWE2M (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Molina, S.; Monteagudo, J.; Miralles, P. Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales; Editum: Murcia, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Escribano-Miralles, A.; Serrano-Pastor, F.J.; Miralles-Martínez, P. Perceptions of educational agents regarding the use of school visits to museums for the teaching of history. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miralles, P.; López-García, A.; Zaragoza, M.V. Didáctica y Divulgación de las Ciencias Sociales; Editum: Murcia, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Benejam, P. Las finalidades de la educación social. In Enseñar y Aprender Ciencias Sociales, Geografía e Historia; Benejam, P., Pagés, J., Eds.; Horsori/ICE-UB: Barcelona, Spain, 1997; pp. 33–52. Available online: https://acortar.link/flNViF (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Eulie, J. Controversial issues and the social studies. Clear. House 1966, 41, 89–91. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/30180531 (accessed on 1 September 2024). [CrossRef]

- Rüsen, J. Historical consciousness: Narrative structure, moral function and ontogenetic development. In Theorizing Historical Consciousness; Seixas, P., Ed.; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2004; pp. 63–85. Available online: https://compress-pdf.obar.info/ (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Rüsen, J. History: Narration, Interpretation, Orientation; Berghahn: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rüsen, J. Jörn Rüsen e o Ensino de História; Schmidt, M.A., Barca, I., de Rezende E.C., Orgs.; UFPR: Curitiba, Brazil, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rüsen, J. Teoria da História. Uma Teoria da História Como Ciência; de Rezende, E.C., Translator; UFPR: Curitiba, Brazil, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Körber, A. Historical consciousness and the moral dimension. Hist. Encount. 2017, 4, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Körber, A. Historical consciousness, knowledge, and competencies of historical thinking: An integrated model of historical thinking and curricular implications. Hist. Encount. 2021, 8, 97–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seixas, P. (Ed.) Theorizing Historical Consciousness; Toronto University Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson, A.; Lee, P. (Eds.) History Teaching and Historical Understanding; Heinemann: London, UK, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson, A.K.; Lee, P.J.; Rogers, P.J. (Eds.) Learning History; Heinemann: London, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson, A.; Gordon, P.; Lee, P.; Slater, J. (Eds.) International Yearbook of History Education; Routledge: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wineburg, S.; Martin, D.; Monte-Sano, C. Reading Like a Historian. Teaching Literacy in Middle & High School History Classrooms; Teacher College Press: Columbia, SC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wineburg, S. Why Learn History (When It’s Already on Your Phone); University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lévesque, S. Thinking Historically: Educating Students for the 21st Century; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lévesque, S.; Clark, P. Historical Thinking: Definitions and Educational Applications. In The Wiley International Handbook of History Teaching and Learning; Metzger, S.A., Harris, L.M., Eds.; Wiley Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 119–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitson, A.; Husbands, C.; Steward, S. Enseñanza y Aprendizaje de la Historia 11–18: Comprensión del Pasado; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, C.J.; Rodríguez-Medina, J.; Miralles, P.; Arias, B.V. Effects of a teacher training program on the motivation and satisfaction of history secondary students. Rev. Psicodidáctica 2021, 26, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, C.J.; Rodríguez-Medina, J.; Miralles-Martínez, P.; López-Facal, R. Motivation and Perceived Learning of Secondary Education History Students. Analysis of a Programme on Initial Teacher Training. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 661780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Medina, J.; Gómez-Carrasco, C.J.; Miralles-Martínez, P.; Aznar-Díaz, I. An Evaluation of an Intervention Programme in Teacher Training for Geography and History: A Reliability and Validity Analysis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-García, A.; Maquilón-Sánchez, J.; Miralles-Martínez, P. Perception versus Historical Knowledge in Baccalaureate: A Comparative Study Mediated by Augmented Reality and Historical Thinking. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, R.; Fernández-Collado, C.; Baptista, P. Metodología de la Investigación, 4th ed.; McGraw-Hill: Mexico City, Mexico, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- McMillan, J.H.; Schumacher, S. Investigación Educativa, 5th ed.; Sánchez, J., Ed.; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, D.T.; Stanley, J.C. Diseños Experimentales y Cuasiexperimentales en la Investigación Social; Kitaigorodzki, M., Ed.; Amorrortu Editores: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- George, D.; Mallery, P. SPSS for Windows Step by Step: A Simple Guide and Reference. 11.0 Update, 4th ed.; Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, M.J. Test y otras pruebas escritas u orales. In Principios, Métodos y Técnicas Esenciales Para la Investigación Educativa; Nieto, S., Ed.; Dykinson: Madrid, Spain, 2010; pp. 191–219. [Google Scholar]

- Pardo, A.; Ruiz, M.A. SPSS 11. Guía para el Análisis de Datos; McGraw Hill: Madrid, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández Pina, F.; Cuesta, J.D. Métodos cuantitativos de investigación. In Competencias Científicas Para la Realización de Una Tesis Doctoral. Guía Metodológica de Elaboración y Presentación; Colás, M.P., Buendía, L., Hernández-Pina, F., Eds.; Davinci Continental: Barcelona, Spain, 2009; pp. 63–96. [Google Scholar]

- Monroy, F.; Maquilón, J.J. Correlación y regresión. In Investigación y Análisis de Datos para la Realización de TFG, TFM y Tesis Doctoral; Hernández Pina, F., Maquilón, J.J., Cuesta, J.D., Izquierdo, T., Eds.; Compobell: Murcia, Spain, 2015; pp. 131–156. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateo, J. La investigación ex post-facto. In Metodología de la Investigación Educativa; Bisquerra, R., Ed.; La muralla: Madrid, Spain, 2009; pp. 195–230. [Google Scholar]

- Arias, L.; Egea, A.; Sánchez, R.; Domínguez, J.; García, F.J.; Miralles, P. ¿Historia olvidada o historia no enseñada? El alumnado de Secundaria español y su conocimiento sobre la Guerra Civil. Rev. Complut. Educ. 2019, 30, 461–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).