1. Introduction

Since the mid-20th century, above all, food and farming systems have been facing new challenges as a result of the deregulation and globalization of markets [

1,

2]. The gradual, ongoing process of standardization and industrialization of food has pushed agriculture towards a highly specialized, productivity-centered system, which has affected rural areas and, in particular, mountain areas because of their limited capacity to adapt to this new globalized world [

3]. Farms have been forced to adapt to the new demands of the market by increasing productivity and cutting production costs so as to remain competitive. This has limited farmers’ decision-making capacity when it comes to choosing what types of food to produce and how to produce them [

4,

5]. As a result, traditional crops that were well adapted to the regional space have been replaced by others that are more attractive to the market and easier to sell, and traditional, environmentally-friendly agricultural practices have been pushed aside in favor of other large-scale production methods with a much greater environmental impact [

6]. This has led to a far-reaching transformation of rural and in particular mountain areas, encouraging the abandonment of farmland, high levels of depopulation, and a disconnection between farm products and the territory. This has resulted in a dramatic loss of biodiversity and, in particular, agricultural biodiversity [

7,

8], which in turn has contributed to the degradation of cultural landscapes with high heritage value [

9,

10].

At the same time, the industrialization of agrifood systems has concentrated the control of the market in the hands of just a few organizations that dominate each transaction, drastically limiting the negotiating power of farmers, who are obliged to accept unfair contractual conditions [

11]. At the same time, a crisis of confidence has occurred amongst consumers faced with mass production with no place and no face. The literature suggests that there is an increasing disconnection between agriculture/food and producers/consumers which has helped create an agrifood model that is far from transparent [

12,

13,

14]. Faced with this situation, it seems vital to explore the potential of different emerging distribution methods to mobilize traditional products that guarantee high levels of agricultural biodiversity in the countryside and decent incomes for farmers. The cultivation of high-quality differentiated products, such as traditional crop varieties, and their sale to consumers interested in supporting local agriculture could offer an opportunity to mitigate the low levels of development endured by the rural world [

15].

In recent decades, faced with the dysfunctions of the dominant agrifood system, the growing demand from consumers for quality food products that are environmentally friendly, locally produced, and ethically correct has helped develop new retail models that are positioning themselves as an alternative to the current system [

16]. These new social, economic, and environmental innovations in the agrifood sector known as “Alternative Food Networks” (AFNs) are emerging as mechanisms that respond to a need for a shift towards more territorialized, collaborative, and sustainable food systems [

17].

Since the 1990s, academic research has centered more and more on analyzing, and understanding AFNs and the role they play for the territories [

18]. There is a wide body of research including studies by Mastronardi et al. [

19] and Prima et al. [

20], which argue that alternative agrifood networks can offer important solutions outside the conventional market, which can breathe new life into the local agrifood system and develop new market niches. In spite of the complexity of the concept of AFNs, which covers a plethora of non-conventional retail formulas, academics agree in describing them as constant, experience-based learning systems, whose main innovative features lie in social interactions and closer links with the rest of the cultural and economic activities in the territory, rather than in a search for technical solutions [

21,

22]. AFNs share a common base idea of recovering a close connection between producers and consumers of food which will foster new forms of governance of the network of stakeholders in the territory while promoting and strengthening a redistribution of the value of primary products linked to the local area and local biodiversity [

23,

24]. For this reason, in terms of their potential contribution to rural development with a territorial base, AFNs appear as tools that are capable of reinforcing social capital, promoting and relocating new associative and market-governance models, and incorporating agrifood products with a sense of geographical origin, thus re-establishing the link between agriculture and society and between the rural and urban worlds [

25,

26].

Alternative Food Networks are therefore regarded as an ideal instrument in the design of rural development strategies centered around the agrifood sector and increasing the value of local agriculture, enhancing processes of transition towards more sustainable socioeconomic models with added value [

27]. The result has been a progressive increase in the number of stakeholders involved, both public and private, who view these models as a chance to bolster regional economies via schemes to boost and promote local products [

28]. AFNs are viewed as an opportunity to regenerate lost trust and transparency via the diversification and transformation of modern agrifood chains on the basis of socio-environmental and social justice ethics [

29]. Nonetheless, although in the scientific literature on this question, and within their theoretical complexity, AFNs stand out as a rich group of practices that contrast with the prevailing conventionalism [

30], there is still a serious lack of knowledge as to how these initiatives work and their capacity to penetrate local and regional food markets. More research is therefore necessary to assess the potential of these alternative models in the development of projects in rural areas with a strong commitment to the environment and agricultural biodiversity. With this in mind, in this study, we will be assessing the possible introduction of local varieties in these circuits. These local or traditional varieties are a form of genetic heritage that is in decline worldwide. Concern about the loss of these phytogenetic resources has resulted in international agreements that promote their sustainable use and conservation. These include the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture, approved by the FAO in 2001 [

31], and the EU Biodiversity Strategy [

32], introduced in 2012, one of whose objectives is to support traditional agriculture for the conservation of crop biodiversity and associated traditional knowledge and skills, as an integral part of agricultural biodiversity. This is combined with the conviction that agricultural biodiversity is a key resource to enable farmers to respond to climate change. Since 2019, the European Union, as part of its Green Deal and in line with the “From Farm to Fork” strategy [

33], has been introducing measures that make it easier for traditional varieties, adapted to local conditions, to reach the market.

This research study was conducted in the region known as the Alpujarra Granadina, in the Sierra Nevada mountain range in southeast Spain, which has a rich biocultural and landscape heritage in which its unique agricultural biodiversity stands out. However, as a result of the socioterritorial crisis affecting the mountain areas of Europe in the mid-20th century, together with the continuing geographic isolation that characterizes them, its agricultural ecosystems are currently at risk due to their incapacity to adapt to the new global economy. In spite of this, and bearing in mind the direction that European policies on this issue have been taking, we believe that the agricultural genetic heritage accumulated in the region, as in other Spanish mountain areas, could provide an important opportunity for development. The traditional varieties of plants are better adapted to the local environment and to less intensive cultivation systems, as well as being more resistant to disease, which could reduce production costs [

34,

35]. In addition, their excellent distinctive flavors and organoleptic qualities have led to growing interest on the part of consumers and an increase in the use of quality labels such as Geographical Indication (GI) or Protected Designation of Origin (PDO). In the Alpujarra we have identified over one hundred traditional varieties, above all of broad beans, tomatoes, peppers, and pumpkins, which could be viewed as important resources for the local agrifood sector [

36]. In this study, our aim is therefore to assess whether these unique, high-quality products, which have firm roots in the territory, could be distributed through the AFNs extended throughout the region itself and the metropolitan area of the city of Granada as the nearest economic hub.

Our initial hypothesis is that the AFNs in Spain and in particular in the Granada urban area have a sufficiently lengthy history and a high degree of social and environmental commitment as to make them ideal channels for the sale and distribution of local varieties, which could be readily introduced into the AFNs’ product range, thus contributing to the conservation of crop biodiversity by providing small farmers with a channel for the distribution of their products.

The general objective of this research is to evaluate those questions that could indicate how suitable the different associations and cooperatives may be for mobilizing and promoting local varieties as differentiated local products. In particular, we aim to find out more about: (i) the objectives and principles of these organizations; (ii) the maturity of these alternative channels; (iii) their capacity to connect producers with consumers; (iv) their attitude towards traditional crop varieties; and (v) their capacity to act in rural areas.

2. Methodology

The research takes the form of case studies and applies a qualitative methodological approach based on semi-structured interviews in which the information gathered is processed using the content analysis technique. Most of our data was obtained from interviews although complementary information were also gathered by searching on the Internet and through participant observation at the Granada ecomarket and other events such as the Huéscar Agriculture and Livestock Fair (Feria Agroganadera de Huéscar), the 19th Andalusia Agricultural Biodiversity Fair (XIX Feria Andaluza de la Biodiversidad Agrícola), the 1st Conference for the Dissemination of Biodistricts (I Jornadas de divulgación de biodistritos), the Fruit and Vegetable Festival (Festival Hortofrutícola), and the Snowflake Potato Fair in Nigüelas. Various different tasting sessions for local variety products have also been held.

From late 2022 and throughout 2023, fieldwork was carried out in the Alpujarra Granadina and in the Granada metropolitan area. These two study areas were selected on the basis of our desire to find out more about the different types of alternative agrifood initiatives both in the region of origin of the local variety crops and in the closest regional market with the greatest purchasing capacity. Given the exploratory objectives of the research, a series of semi-structured interviews were carried out with a qualitative approach. Interviews of this kind with a preset questionnaire enable the interviewee to answer certain specific questions in much greater depth and detail [

37,

38].

The case studies focused on AFNs that met two criteria. These were, firstly, having been set up using innovative associative formulas and secondly, having links to the food sector, and in particular to the production, sale and distribution of fresh fruit and vegetables. The case study selection process was initially based on the use and consultation of secondary sources such as the websites of the different AFN initiatives in Granada, our presence in events related with local food strategies organized by public bodies such as own councils or the Granada Provincial Council, and informal meetings with members of both the Granada Agroecological Network (Red Agroecológica de Granada—RAG) and the Alpujarra Agroecological Network (Red Agroecológica de la Alpujarra—RAA). These preliminary contacts enabled us to draw up an initial list of varied initiatives of great interest for our research objectives. After these initial approaches, we then carried out numerous visits to alternative retail outlets in the city of Granada and in the main towns and villages of the Alpujarra. These visits produced new contacts and enabled us to broaden and complete our original sample group. In the end, 11 AFNs met our selection criteria, 9 from the Granada metropolitan area and 2 from the Alpujarra.

In the end, however, three of the organizations in the Granada metropolitan area declined to participate in the study. As a result, the final sample group had eight Alternative Food Networks, 72.73% of the total, which turned out to be quite representative and illustrative. Six were situated in the Granada metropolitan area and two were situated in the Alpujarra Granadina, as can be seen in

Figure 1.

The interviews were carried out face-to-face with members and managers of the different associations identified. These took place either directly in the facilities of the associations or via previously arranged appointments at a particular place. The interviews lasted between 1 h 45 min and 2 h 30 min and were all recorded after receiving prior consent from the interviewees. The questionnaire for the semi-structured interview was agreed on and drawn up by the research team according to the quality criteria established by Naz et al. [

39] and Husband [

40]. Two pilot trials were conducted to validate the quality of the information obtained and rephrase certain questions.

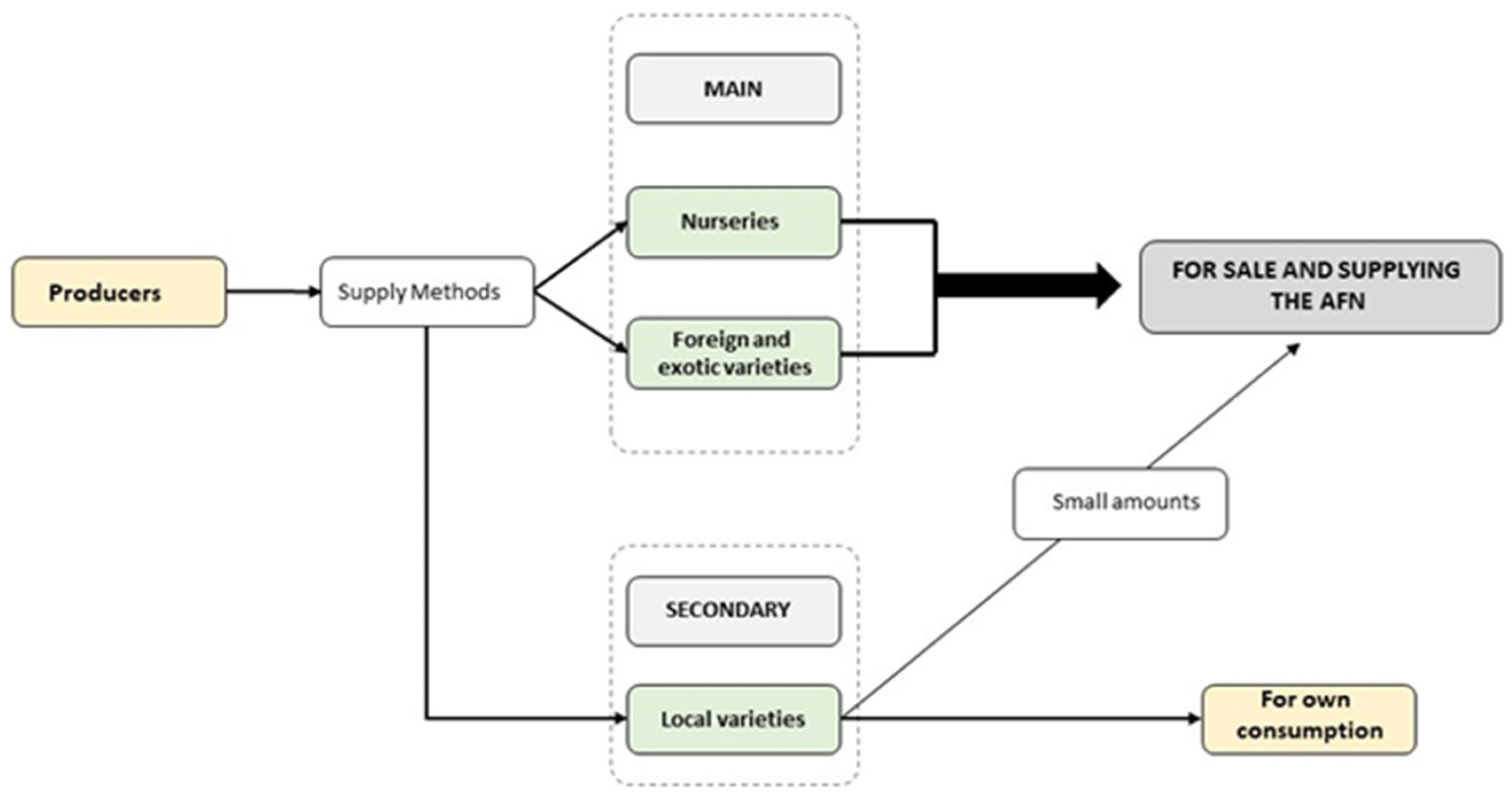

The content analysis method was used to analyze the interviews. Taking the transcriptions of the interviews as a basis for this analysis, the first step was to select units of meaning. We then codified and condensed these units of meaning before finally classifying them into six large categories: (a) degree of maturity of the AFN initiatives, (b) business models or social movements, (c) AFN connections, (d) supply, sale, and distribution models, (e) AFNs and local crop varieties, and (f) AFNs and local development. In this way, we identified common positions and situations, as well as differences between the various AFNs. Although software programmes for processing qualitative data are widely used by researchers today, we decided to codify the information manually so as to prevent important ideas from being lost during this process [

41,

42]. The conceptual framework for our analysis is shown in

Figure 2.

The very concept of AFNs has evolved quickly due to the incessant appearance of new models and retail formulas and of social relations that have little to do with those of conventional agrifood markets. The complexity of this concept has meant that there is no standard or definitive classification of AFNs. In spite of this, research studies such as those by Ammirato et al. [

2], Ibáñez et al. [

7], or Sánchez [

43] have analyzed this problem within the framework of their research and proposed a basic classification of the different types of AFNs. Basing ourselves on these studies and taking into account how the different AFNs define themselves, we classified our case studies by type. By the end of this process, we had identified a total of four different types of association in the study area, as can be seen in

Table 1.

3. Results

3.1. Degree of Maturity of the AFNs

These organizations first appeared in Spain at the beginning of the 1990s, above all in Andalusia and Catalonia, and from the year 2000 onwards, they began to spread across the entire country. Our analysis of the interviews revealed that Granada played an important early role in these movements, and in particular El Encinar, which was one of the first associations of producers and consumers of organic products in Spain, together with others such as Germinal, the first association formed in Catalonia or La Ortiga in Seville, all of which appeared in 1993. Other important initiatives include Las Torcas, which has been operating for 24 years, or Hortigas with 18 years’ experience. Another AFN known as Valle y Vega has been operating as such for 11 years, after being created via the merger of two smaller pre-existing associations. The interviews revealed, as can be seen in

Table 1, that almost all of the AFNs have been operating for more than 10 years, with the exception of La Bolina and La Retornable, which have been functioning for less than 5 years. The interviewees highlighted the large number of projects of this kind that have appeared in recent years in the province of Granada, this helping to increase the visibility of these associations as a whole.

As regards possible changes in these organizations over the years, in general, the interviewees agreed that the number of members had remained stable or even grown, although the typical profile and their habits had changed. The spokespeople for the organizations explained that the general level of participation and commitment of the members has declined, while for their part, consumers have become harder to please, increasingly tending to associate the quality of the project with its appearance and presentation. In addition, some consumers join up for reasons that have little to do with the values of the association, such as obtaining a series of benefits when it comes to purchasing the products. We found different membership models, the most common of which was via the payment of a fixed subscription that enables members to take an active part in decision-making within the organization and enjoy more favourable buying conditions. Almost all of these associations and cooperatives are also open to non-member consumers, who can buy from them through different sales channels such as the Eco-Market that they organize periodically in Granada or through specialized brick-and-mortar and online shops, as happens with El Encinar, Valle y Vega, and Las Torcas. The only one that does not sell its products is Hortigas. In this case, all of the members cultivate a common piece of land and share both the work and the harvested fruit and vegetables in a planned way. In the case of Como de Graná, the consumers personally contact the associated farmers to buy what they need, thus establishing a direct consumer–producer relationship.

As regards their presence in the market, which they have been building up over time, the interviewees highlighted the limited capacity of AFNs when it comes to finding the right mechanisms to reach a wider audience. Many of those interviewed agreed that the main methods used to publicize their association were word-of-mouth recommendations and the creation of networks such as the Granada Agroecological Network (Red Agroecológica de Granada). This allows them to maintain a shared website, hold a monthly market in the city of Granada, and organize various different events. In some cases, the associations find universities to be a good source of large groups of young people who are interested in the new challenges facing the way we understand and consume food while at the same time helping care for the environment and local areas. University students form a floating population that helps to maintain a constant flow of new members, thus providing a replacement mechanism that guarantees the continuity of some associations. One example is Hortigas, which, by organizing events at Granada University contacted students who were interested in their ideas and objectives. In the case of large rural areas such as the Alpujarra, replacement is more complicated as there is no solid social capital, with the result that in this case, it is the foreign and “neo-rural” population who play an essential role within these organizations. In addition, the communication and promotion of these associations for the production and consumption of food products is benefiting from the use of social networks and websites to broaden their sales and distribution channels and transmit their values and their agrifood model to society. One of the main concerns they expressed in the interviews was the poor level of support received from public bodies. They made clear that these bodies made little effort to raise awareness about the benefits of this agrifood model or to help them inform the wider general public about the range of sustainable products that they have on offer. In spite of the increasing presence of these products in our everyday lives and in the objectives of European Rural Development and Research policies, they insist that the lack of institutional support makes it difficult to reach the public directly.

Another sign of the development and maturity achieved by the networks that we studied are the changes they have made in their legal status. Many of these organizations have gradually developed over time or intend to do so soon, from their first initial registration as an association to later becoming a cooperative. This is what has happened, for example, in the case of Las Torcas and Valle y Vega (which was formed when two associations merged to form a cooperative). Others such as El Encinar and La Retornable plan to make this change in the short term. Among the reasons put forward by the interviewees is the fact that many of the public subsidies or grants that they received as organic farming organizations no longer exist. In addition, the cooperative system requires members to show a higher level of commitment and responsibility to the organization than in an association. These legal changes have taken place in the longest established networks, whose business model now has a sounder footing, after shifting away from the participative models which on occasion were overly restrictive when it came to setting out in new directions.

3.2. Business Models or Social Movements

In spite of the fact that all of the organizations we analyzed operate in the food sector, in half of the cases studied, the associations were founded within social movements that were not necessarily linked to food or agriculture. Half of those interviewed stated that for their association, their social mission was a top priority and was closely linked with the protection of the environment. These values spurred them to develop projects relating to agroecology, a form of agriculture which they define as “environment-friendly and sustainable” as well as contributing to food that is “healthier for consumers”. In the case of La Bolina, for example, agroecology connected very well with its more social and humanitarian objective of helping immigrants and refugees to integrate into society.

In general, they all emphasized the social benefits that their projects provide through agroecology by promoting more sustainable consumption models that are also fairer for farmers. These models respect agricultural cycles, offering more diverse, healthier food products and creating social capital by contributing to the setting up of short distribution channels that operate as groups of people who come together in support of a specific mission. They also strengthen the identity of the territories in question and their surrounding area.

The fact that they consider their mission more important than the profitability of their activities makes them more attractive to young people who are interested in joining these groups and to possible new members in general. The spokespeople from the organizations explained that part of the charm of these initiatives is that they are places for exchanging information and ideas where people can become more aware of the problems affecting society and the environment. They can share their experiences and their concerns and many bonds of friendship are formed. It could be argued that they are established more as spaces for socialization than as businesses with a firm commitment to local and ecological agriculture, objectives that in most cases seem of secondary importance. Only Las Torcas and La Retornable give priority to the economic dimension and maintain a more business-like approach, but without forgetting their social dimension.

The interviewees pointed out that these collectives put much more emphasis on maintaining the coherence and solid foundations of the ideals and values that they wish to represent with their organizations than on rapid growth that might distort them. Likewise, many of the case studies declared that they operate in the market more as a means of subsistence, to enable the organization to remain solvent and survive over time, rather than with a business purpose in the strict sense. They explained that this is due to the fact that the profit margins that they obtain from the subscriptions paid by the members are too tight to provide these organizations with the necessary stability, which means that they must also support their activities with business development strategies to expand and diversify their income, so as not to put their continued survival at risk.

It is worth emphasizing that although they still operate in a participative way, the AFNs admit that as time has gone by, their collaborative ethos has become increasingly blurred in favor of relations of a more transactional nature for the sale and purchase of goods. Among the reasons for this, the interviewees repeatedly explained that many of their founding members are now quite old and that the new generations have not connected with the participative philosophy of old and that their involvement is more irregular. In addition, the assembly-type structures in which decisions are taken in many of these organizations have given rise to intense debates which have sometimes resulted in arguments between members, demotivation and sometimes even people leaving the association. As for the farmers, given that these kinds of initiatives cannot absorb their entire production, although they continue working with them and maintain close relations of trust, in most cases, they are not actually members of the organization, so as to avoid limiting their different possible outlets.

3.3. Connections Between the AFNs

Our analysis of the case studies revealed that all of these organizations know each other and maintain strong interconnections. Given that they are part of the same social movement, there are frequent links between them in which we identified the exchange of ideas, information, resources, and technical knowledge, thus creating an atmosphere of trust and innovation that helps increase the social capital in the areas in which they operate. In addition, in all of the cases analyzed, the organizations maintain contact and exchange with other AFN projects such as ecoshops, Km0 projects, bulk food shops, etc. There are many examples of these connections at a local, regional, and national level and, sometimes, they can even transcend international borders. For example, Valle y Vega has links with other ecological cooperatives such as La Subética Ecológica or Guadalhorce Ecológico; La Retornable has connections with consumer groups in Barcelona, among others; and Las Torcas sells to consumer groups in Germany.

We noted how from these initial links a stable community is gradually established with a strong territorial identity around related ideals and economic activities. In this way, as various authors have made clear, these organizations are established as genuine ecosystems of initiatives and innovation [

44]. In the case of Granada, the collaboration between the different organizations that support an alternative agrifood system has been formalized via the setting up of the Granada Agroecological Network, which brings together and represents the vast majority of these associations across the province and makes them more visible. This network has organized a formal space known as the Ecomercado or Eco-Market, which operates in two public spaces in the city. This is a market where local products are offered to consumers, where friendlier, more direct relations can be established between clients and producers, and which also serves as a space for dissemination and learning through the purchasing experience itself and through participation in a range of activities and workshops. Communication is a task carried out collectively by the various organizations as a whole and individually by each one and often involves the holding of workshops, talks, and events of different kinds such as those organized by El Encinar, Hortigas, Valle y Vega, or Las Torcas, among others.

Another idea that was frequently repeated in the interviews is that none of the AFNs view the others as “competitors”. They believe that by working together, they can make the ideals they are defending more visible and raise awareness amongst consumers and the general public as to the beneficial effects of their particular farming model, at the same time as encouraging demand for locally grown products. They feel that competing with each other would weaken the objectives that of all these networks share. Similarly, many of the interviewees said that they were convinced that there were potentially large numbers of consumers who were committed to more sustainable methods of food production and consumption. Nonetheless, greater efforts are required to raise awareness and improve coordination between these different networks and relevant public bodies so as to reach out to more people, which is why maintaining this strong collaboration between the different AFNs is so important. The desire to collaborate is based on their shared desire to establish a fairer, more sustainable agrifood system, although the messages regarding the specific objectives of each organization may vary. For example, in La Bolina, they target consumers who are interested in the role agriculture can play in the integration of poor people in society, while La Retornable is aimed at people who are interested in the circular economy and the best use of resources. For its part, in Como de Graná, the essential commitment is to small farmers from the fertile plain around the city known as La Vega.

3.4. Sales and Distribution Models

There are notable differences between these organizations as regards supply methods. The interviews revealed that five of these networks have members who are small producers who supply the association. In contrast, La Retornable and Las Torcas work directly with non-associated producers with whom they have a close relationship of trust, however. In general, the relations between the farmers and the other members of the network are typically very close, stable, and long-lasting. In many cases, they are small professional farmers who work with seasonal products, although, in projects such as Valle y Vega, La Colmena, and La Bolina, there is a considerable presence of “neo-rural” and beginner farmers for whom agriculture is not their main activity. In the case of Hortigas, whose products are consumed directly by members, the rules state that all members, even those with no experience, must work in the fields. They also have three professional farmers who are engaged in working in the main vegetable garden and teaching the members. Other initiatives, such as El Encinar, have a significant group of small producers with whom they agree on an annual basis on what they are going to produce and the prices they will pay for each product. In this way, they try to stabilize the supply and the prices for clients and producers, so as to reduce the instability that often affects the food market. One special case is Como de Graná, an association that was originally founded by the producers who supplied it. During this initial period, the producers established the prices of their products. However, as time went by, these farmers stopped being members and although they maintained close, friendly links, they were much less actively involved. In this way, they do not have to commit themselves to selling all of their production to the organization and have more room for maneuver when it comes to selling their products through different channels and securing the best possible price in each situation. It also frequently happens that the association cannot absorb all of its seasonal produce and they therefore have to look for other outlets.

The interviewees also mentioned that they often work with other small producers who do not belong to the associations, so as to complete or broaden the range of products with foods that are out of season or to cover shortfalls of certain products that their associated farmers have not been able to supply satisfactorily. They also explained that the different associations often buy and sell products from each other when one of them has a shortage and the other has a surplus. If they have a specific need at a certain time, they contact the producers from other associations informally to purchase their products. The better established the organizations are, the more they tend to sacrifice part of their values and philosophy to adapt to the demands of consumers, selling products that are out of season or from other countries or buying from intensive organic greenhouses. Certain products such as tomatoes must be available all year round because they are in constant demand. For Valle y Vega, El Encinar, and Las Torcas, they explained that there is a widespread lack of awareness amongst consumers and limitations in terms of communication to inform them about agricultural cycles and other similar questions. This means that they have to be flexible on certain principles, so as to maintain their clients’ loyalty and not lose them.

Almost all (7 out of 8) establish as a basic requirement that the product should be organic, and the most common requirement is for products to have to undergo a control procedure involving the implementation of Participative Guarantee Systems (PGS) for organic products. These are independent systems, which appeared as an alternative to the conventional certification system and guarantee that the products have passed certain protocols and standards established by the group regarding their respect for the local area and the environment. Associations such as El Encinar have their own PGS for their producers and even offer these services to other organizations so as to guarantee that the products they obtain comply with the principles of agroecology. These guarantee systems have little in common with the costly and complex official certification process, which they describe as “extortionate”. In addition, the ecological PGS also encourages the forging of high-quality relationships of mutual trust between the producers and the members of the AFN. In contrast, the associations with more developed sales channels such as La Retornable or Las Torcas oblige the producers to present official ecological certification. Both of these AFNs, which are legally constituted as ecological cooperatives, can only sell officially certified products and must undergo relevant inspections.

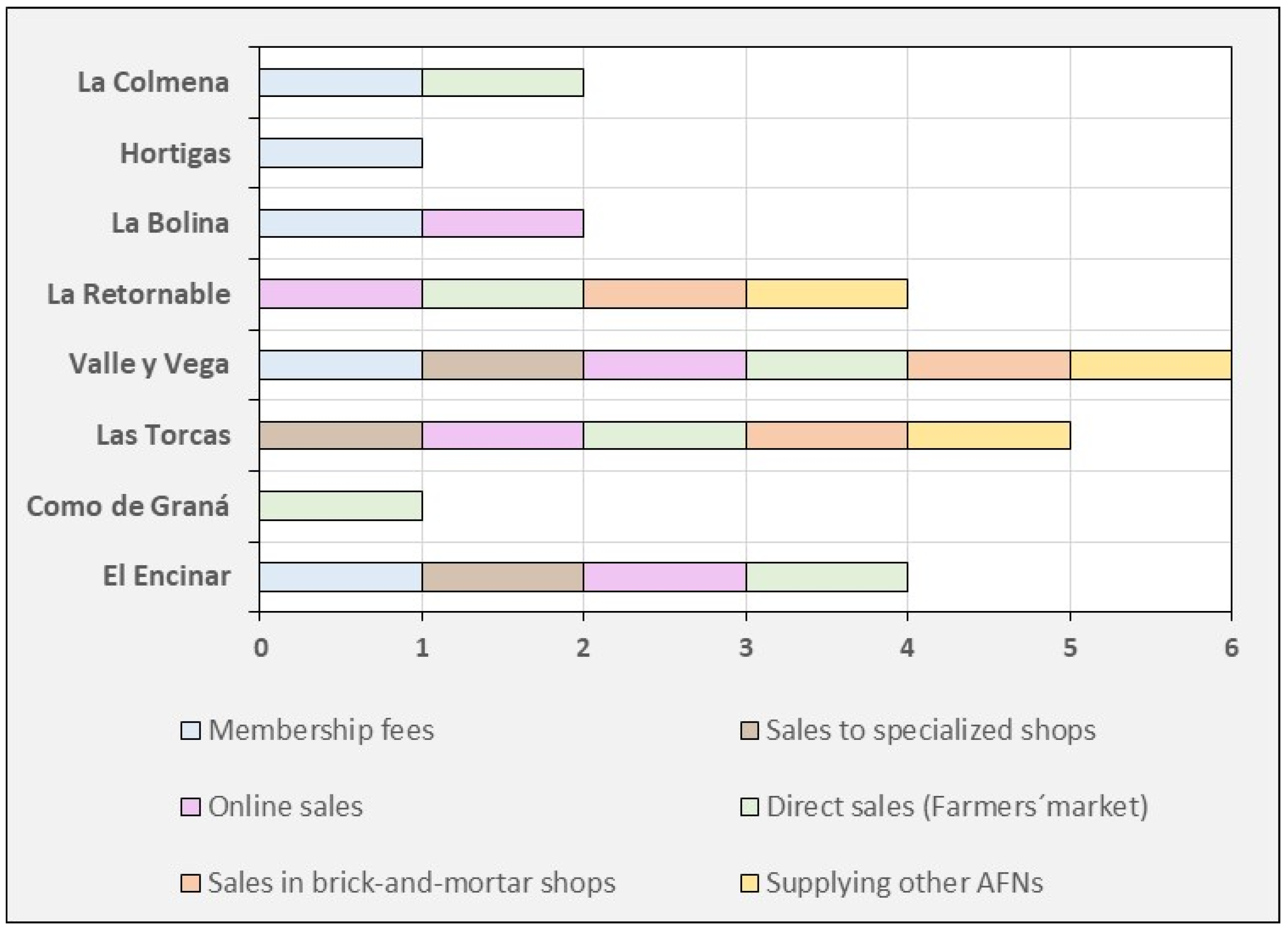

In terms of the sale and distribution of these products, a wide range of varied formulas are used by different organizations. In

Figure 3, we can see that the AFNs that function as ecological cooperatives or have plans to do so have the widest range of distribution channels and that Valle y Vega employs all the possible options. As mentioned earlier, one of the main ways of getting the products to consumers is the sale of products to the members themselves by different formulas such as the weekly delivery of a vegetable box, as happens in La Bolina, the ordering of products directly from the farmer, in the case of Como de Graná, or purchase in the shop with discounted prices, as happens in El Encinar, among others. However, these are not the only ways of sale and distribution, as in all of the case studies, with the exception of Hortigas whose members consume what they grow, there are various sales channels open to both members and consumers who are non-members. These include direct sale at farmer’s markets and in particular in the Ecomercado of Granada, in which La Retornable, Las Torcas, Valle y Vega, El Encinar, and Como de Graná all participate. They assured us that the personal contact between producers and consumers creates an atmosphere of trust, participation, and proximity which strengthens loyalty and reinforces a fair, sustainable agrifood model. Another widely used method is the supply of specialized retail establishments such as eco-shops, other associations with a strong commitment to organic food production, and different commercial establishments or restaurants committed to a food system that is respectful of the environment and the territory. As they explained, these methods go beyond the associated consumers and enable the entire production to be offered for sale on the market and obtain sufficient income to give the project stability. Sale through brick-and-mortar shops is also very important as they bring these products closer to local people (whether they are members or not) and provide a place where consumers can meet and exchange ideas and opinions. This method is used by El Encinar, Las Torcas, and Valle y Vega. Most of the organizations make clear that using multiple sales channels enables them to publicize themselves better and create links with consumers of different kinds. Organizations such as Valle y Vega or Las Torcas stated that even though they have well-established sales channels, they also participate in other channels so as to heighten their local presence and try to get the local population involved in their ideals to promote more sustainable agrifood systems.

3.5. AFNs and Local Crop Varieties

In general, in the answers offered by the interviewees, there was a high degree of confusion and indeed ignorance in relation to the concept of “local variety”, as defined as “heterogeneous local adaptations of cultivated plants that have a historical root, a distinct identity, often associated with genetic diversity, farmers’ seed selection and field practices” [

45]. In most of their answers, local crop varieties were identified with products cultivated in the local area even if they came from plants brought in nurseries that work with commercial seeds. Local or traditional variety products were identified with local products. In some cases, the term “local product” even encompassed regional or national products. This lack of knowledge is to some extent a sign of very limited interest in products of this kind. The analysis of the interviews revealed that the Granada AFNs were most interested in the production and consumption of organic foods and in agroecological cultivation methods. However, some associations such as La Bolina expressed some interest in traditional varieties, “we try to ensure that they are local seeds”. Those interviewees who did understand the meaning of local or traditional varieties explained that it is a concept that the Granada AFNs are gradually becoming aware of, although it is still relatively unknown, both for the people who move in these alternative circles and for the public at large.

There is a generalized belief that, given the characteristics of the current food market, these products would not be very attractive to consumers who tend to assess fruit and vegetables according to certain preset standards in relation to their homogeneous shape and appearance, even if their taste is highly valued. As the interviewees from El Encinar, Valle y Vega, or Las Torcas made clear, consumers are often quite traditional and reluctant to try unknown products, which is understandable given that “you are fighting against an advertising monster which preconditions the consumers’ ideas about what a product should look like”. This means that the shapes, textures, and colors of these varieties do not respond to the demands of customers who associate quality with a predetermined appearance.

Together with these difficulties linked to consumer preferences, the AFNs who have worked with local varieties explained that these products are very delicate to transport in that they bruise or crack easily. They are also more perishable and must be sold quickly, all of which require additional efforts in terms of distribution and raising clients’ awareness. In addition, AFNs such as Las Torcas, Valle y Vega, Como de Graná, and el Encinar explained that very few farmers work with local varieties as they are not worthwhile in business terms, “in terms of yield, they are not [profitable]”, when compared with other more commercial varieties. Obtaining the seeds and making their own seedlings involves a very significant additional effort for farmers, which is not compensated in the sales price. They mentioned that many farmers grow local varieties for their own personal consumption: “I plant them just to have them, but they are not commercially viable” and because “they are always the best in terms of flavour and organoleptic qualities” but they do not believe they would be commercially successful, as can be seen in

Figure 4. In spite of everything, most of the interviewees stated that their clients are increasingly prepared to buy products produced nearby and return to “the tastes we always enjoyed” and to consume sustainable products that help more farmers. However, the concept of local variety still remains something of an unknown. For this reason, associations and cooperatives stress the need to improve the communication and promotion of local varieties and the benefits they provide, while demanding more support from public institutions. They are convinced that in spite of the difficulties in terms of logistics, sales, and distribution, the introduction of local varieties from the Alpujarra in their networks could be viable on a trial basis.

Going back to the disadvantages of local varieties in terms of production, all of those interviewed—both the farmers who were members of these networks and others who supplied them—confirm that although they grow some seedlings from seeds, most of their fields are planted with organic seedlings from nurseries in which “Saliplant has a monopoly” in the province of Granada. They mentioned that this is the most reliable, quickest method for ensuring a stable level of production that ensures a minimum amount of fruit and vegetables to keep their business going and that the seedlings they grow themselves are a complementary product, normally for their own consumption. In spite of the fact that almost all of the seeds come from nurseries, they always try to choose “varieties from the area”, preferring not to cultivate varieties with no links to the territory, as part of their respect for the area in which they are based. One particularly interesting case was the Hortigas network, which explained the efforts they are making to recover local agricultural biodiversity by creating a seed bank that minimizes the dependence of their association (and of any others who might wish to join them) on conventional seeds and seedlings. There are various signs therefore that these organizations are making an effort little by little to recover these seeds, so as to maintain local diversity and self-sufficiency.

In our analysis of the interviews, we also observed a tendency to diversify the products on offer as part of a strategy to improve sales. This has resulted in the inclusion of various exotic and foreign varieties in the territory. The interviewees explained that these exotic varieties were being introduced in response to new market demands, as has happened in La Bolina, where they try “to have very specific varieties for the Syrian market, such as for example mini-courgettes”. In some cases, these foreign varieties are introduced by new settlers of foreign origin who grow them in their fields, as happens in La Colmena in the Alpujarra. There is also a need to supply basic products such as tomatoes all year round. This has led to some extent to them working outside normal cultivation cycles, receiving supplies from areas of intensive greenhouse production or from outside Spain. This has led to conflicts within the organizations with accusations that they are moving away from the agroecological principles that they have always proudly defended. One member of Valle y Vega argued that “I would do more to promote the importance of eating local produce for health reasons or for maintaining local resources and helping combat climate change” and that “I would highlight local varieties much more on the cooperative’s website and locally-grown and seasonal produce”.

3.6. AFNs and Local Development

Our analysis of the interviews also revealed a preference amongst the AFNs for locations in periurban areas as opposed to more rural areas with difficult access such as the Alpujarra. Most of the people interviewed explained that these organizations preferred to be located in the metropolitan area of Granada because it is the most dynamic economic space in the province. Important social capital has been built up in this area, linked initially to ecological production. It also has a good communications network that enables mobility and is near highly productive agricultural areas such as the Vega de Granada. Another advantage is that it is easier to find employment to complement their agricultural income. Above all, it is where most of the consumers in the alternative market are concentrated and it is therefore a key objective to be located near them. Associations such as La Bolina were considering various different locations including the Alpujarra, although they ultimately rejected it “because it was very isolated with only three buses a day and because communication between people in the area is less likely to bring people together than in the city”.

The interviewees explained that when it comes to transporting and delivering the goods, good communication is paramount, in that the AFNs manage their own logistics and that this has costs in time and money (in fuel) which are difficult for the members to bear. Being near the city and having small farmers in the immediate area of the Vega de Granada or the nearby Lecrín Valley is very practical when it comes to making efficient deliveries and creating a product that is more economical and more flexible than in more remote, more distant areas. In addition, the typical profile of the farmers associated with this type of AFN is one of periurban producers and new farmers who have no history or tradition in the sector and whose main activity is not agriculture. This means that their production is relatively small and their commitment to alternative networks of this kind does not involve large economic risks. In the specific case of the Alpujarra, it is precisely this group of new farmers that have enabled collective actions and associative movements of the kind that build and supply the AFNs. In general, they are people of local and foreign origin with an attitude of respect for the environment and the local area, who are interested in farming but whose very low level of agricultural activity does not imply a significant economic reactivation of agriculture in the region.

In the case of professional farmers, many have given up being members of these associations so as not to commit their entire production to a single organization, which frequently cannot absorb all their produce. This enables them to operate in the conventional market and, depending on the situation at the time, obtain better prices for their goods. “When [these professional farmers] have products that the network cannot sell, they have to look for alternatives”. In many cases, this requires more work and time to move and find buyers for all of their goods, sometimes obliging them to travel to other provinces such as Cordoba, Seville, or Malaga.

In the interviews, they also highlighted that the market in the metropolitan area of Granada in particular and in the province in general is saturated, as there is “more supply than demand” for the type of products that these ecological cooperatives and associations produce. Likewise, some of the interviewees such as the spokesperson from El Encinar claimed that “people are not prepared to pay a little extra for something, especially in Granada where people have to count their pennies more carefully, so their first priority is to watch their pockets”, in reference to the province’s weak economy, which together with the fact that these movements are largely unknown amongst the general public greatly restricts the potential market in the area. This leads us to conclude that, for the moment at least, the AFNs are not a solid business outlet for the small professional farmers linked to these initiatives. Interest in these alternative distribution models does not seem to be growing; in fact, quite the contrary, as farmers who are not yet connected with alternative circuits of this kind are reluctant to get involved, especially in rural areas.

In the case of the Alpujarra Granadina, as well as having a very small social capital, if we measure this in terms of the density of its associative fabric, another of the added difficulties for the development and successful implementation of initiatives of this kind, as explained by the representatives of La Colmena and Las Torcas, is the widespread presence of family-run vegetable gardens in this area. This is a very common feature of rural mountain areas and leads to the spontaneous exchange of seasonal products between family members and neighbors which tends to discourage the creation of formal alternative associations. As the interviewee from La Colmena explained, this is why most of the products that they promote within this association are from their winter harvest for which there is more local demand, as people do not plant so many vegetables in the winter.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

The results of this research offer an insight into the potential and limitations of the alternative agrifood formulas in the city of Granada and the nearby mountainous region of the Alpujarra in the distribution of local varieties of fruit and vegetables from the region. In particular, our analysis revolved around those questions that could indicate the degree to which the different associations and cooperatives could be considered suitable channels for mobilizing and publicizing these differentiated local products. To this end, we analyzed their objectives and principles; their level of maturity; their capacity to connect producers with consumers; their attitudes towards traditional crop varieties; and their capacity to act in rural areas. All of these questions were covered by structuring this section into three blocks where we try to establish whether the particular features of these AFNs are positive for the distribution of local varieties, whether these varieties already play a role in these organizations, and whether AFNs could help dynamize the rural world.

4.1. Characteristics and Behavior That Make AFNs Effective Channels Through Which Local Variety Products Can Reach Consumers

This research highlights that AFNs form part of the same social movement with common principles aimed at consolidating nearer, more sustainable, more independent communities with closer links to the place where they are established [

46,

47]. In this sense, they offer market circuits that adapt better to the socio-environmental practices behind local crop varieties. These varieties are differentiated products that are part of the biodiversity provided by agriculture to managed ecosystems or agroecosystems and with the protection of traditional ways of working that are closely connected with the needs of crops that are adapted to the specific conditions of the place. This is directly linked with the environmental awareness shown by the AFNs of Granada in their transformative vision of the dominant agrifood system, a vision which they share with initiatives of this kind all over the world [

48]. In short, the AFNs we analyzed want to help create a more territorialized agrifood system that could include the incorporation of these differentiated products from the Alpujarra. Other authors have also explored the suitability of AFNs for promoting the conservation of agricultural biodiversity. These include Pinna [

49], with a study of two rural parks in Italy, and Corsi et al. [

50], who came to the conclusion that without the distribution channels provided by AFNs (direct sales at farms, local markets, and festivals), the farmers who continue to grow traditional varieties in Tuscany would find it very difficult to sell their products.

In their role as channels for the distribution of fruit and vegetables from the Alpujarra, it could be argued that in spite of their relatively small size, which prevents them from moving large volumes of products, the AFNs of Granada have achieved a significant degree of maturity and are well established in the territory. Their experience gives them in-depth knowledge of alternative markets, which together with their ability to collaborate with each other and operate within networks inside and outside Granada means that they have the potential to expand their market share, as they improve their ability to convey their values and principles to consumers and make them aware of the benefits of the products they sell. Studies such as those by Sgroi and Marino [

51] or Berti and Mulligan [

52] show that in other parts of the world with extensive development of AFNs, there is growing demand for local, sustainable food products and that the AFNs are searching for the right mechanisms to enable them to operate at a suitable scale to transfer a higher volume of local products to consumers.

All of the AFNs analyzed herein work with very small volumes of production and preferentially with local products. This adapts well to the progressive introduction of local varieties—fresh seasonal products cultivated in limited quantities by small local farmers-into the AFN distribution channels. At the same time, the commitment of these associations to obtain a fair price for farmers could encourage a more decisive push to plant these varieties which would open opportunities for these small farmers to reach specialized markets, at the same time as helping revive local culture. In addition, these organizations and their clients are very sensitive to the values of the product in terms of its taste, quality, and authenticity. For all of these reasons, AFNs would be more open to including local varieties in their product range. In addition, at present, potential clients cannot buy these food products easily in that almost all of these varieties are only grown for consumption by the producers themselves or perhaps for informal exchange, which means that the AFNs could offer a unique product of great value. In fact, our research has shown that many of these organizations would be quite willing to incorporate local varieties into their product range.

However, even though the AFNs appear willing to work with local varieties, the producers do not receive sufficient returns on their crops when they work solely as members or suppliers of these associations and cooperatives. Farmers must face the difficult task of selling all their products on the alternative market and are obliged to engage in continuous negotiation processes in relation to the amounts they produce and the sales price. Local varieties require more work and are less productive. This means that on many occasions, the price that farmers obtain does not cover the work and the costs involved. In addition, in line with other research studies such as those by Manganelli et al. [

53] or Vercher [

54], the fact that the producers’ aspirations with regard to obtaining a price guarantee are not always satisfied means that many of them prefer having AFNs as just one of several sales and distribution channels rather than as a space to which they have to commit themselves 100%. This is understandable in the sense that many AFNs are more like social movements than businesses in the strict sense.

For this reason, it is necessary to maintain constant communication and agreement between the two ends of the chain such that the farmer is guaranteed the sale of his/her crops and the consumers have a sustained supply of these local variety products. Our research shows that the AFNs still have to learn more to improve the organization and professionalization of their relations with farmers.

4.2. Role Played by Local Varieties in These Networks and the Need to Strengthen This Role

As has been seen throughout this study, local varieties comply well with the general principles of AFNs in that they fulfill consumers’ aspirations for sustainable high-quality products. They are characterized by a strong commitment to local society, culture, and the environment, which seems perfectly compatible with the need to protect agricultural biodiversity, food security, and local genetic heritage as a resource for endogenous development. In addition, the Granada AFNs work with certified, mainly organic products, an aspect worth highlighting given that as we have discovered in this study many of the producers in the Alpujarra who decide to cultivate local varieties already work with organic foods or are involved in agroecology. In the same way, the Granada AFNs see local varieties as an attractive, differentiated product in a market niche that has yet to be exploited. Indeed, Pérez-Caselles et al. [

55] identified certain market segments that show a preference for traditional varieties.

Nonetheless, although it is true that some of the AFNs we analyzed are encouraging the introduction of traditional varieties, they continue to play a very limited role. They are largely unknown, to the point that the concepts of “local product” and “local variety” are often confused. Chiffoleau, et al. [

56] conclude that in spite of the fact that agricultural biodiversity was viewed positively in a survey carried out in seven European countries, the interviewees displayed limited knowledge of this subject. This explains their very limited presence in both the discourses and the interests of these organizations and in the list of products that they offer, in that we have hardly noted any products advertised as such on the websites, in the shops, or in the monthly market for direct sale to consumers. Furthermore, the stakeholders interviewed observed that there was no specific demand for these products and that when on occasion they were offered for sale, their acceptability to clients was negatively affected by their less attractive appearance. This means that additional efforts must be made to encourage clients to try these “new” products, a task which, in spite of everything, we believe that AFNs are more capable of carrying out successfully than conventional retail outlets. Furthermore, the need to fill the shelves or weekly vegetable boxes with a wide variety of products all year round is a priority for these organizations and is something that can be achieved with organic products but not with local varieties.

Some of the AFNs clearly had greater knowledge and more interest in local varieties than others, although even in these cases, the contribution these varieties could make to a more sustainable agrifood system is often unappreciated (biodiversity, genetic heritage, cultural heritage, and resilience to climate change or food security). This means that they do not acquire the added value that AFNs attribute to organic products, for example.

Faced with this lack of knowledge of local varieties, both on the part of the organizations and of consumers in general, which makes it more difficult for them to enter even these alternative markets, the interviewees agreed that significant efforts would be required in terms of communication. We agree with authors such as Opitz et al. [

28] that AFN participation enhances consumers’ learning about food and agricultural production, although our results show that their communicative capacity is still very limited when it comes to local varieties. For this reason, public institutions have a vital role to play in raising the profile of these products and teaching the public about their benefits, so that consumers can appreciate the full value of these products and the contribution they make to rural sustainability [

57]. Poças Ribeiro et al. [

58] and Berti [

11] also stress the need for governmental actors to play a more active role by promoting a healthier, more sustainable diet, as well as making it easier for AFNs to obtain public contracts, set up collection points. etc. Similarly, the lack of a brand or label that clearly identifies local varieties from the Alpujarra makes it much harder to recognize them. As made clear in studies such as Jiménez et al. [

6] and Mora and Menozzi [

59], if they were grouped together under an identifiable brand label such as for example “Natural Park of Andalusia” or “Spanish Biosphere Reserves” or a Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) or Geographical Indication (GI), this would give these varieties added value as has been observed in experiences of a similar kind in other European countries [

60,

61,

62].

4.3. AFNs as an Opportunity for the Development of Rural Spaces

The idea that AFNs can be viewed as assets for rural development has been a key feature of research by authors such as Floriš and Schwarcz [

63], Kiss et al. [

64], and Hava-di-Nagy [

65], who confirm the potential of short food chains as a motor for rural development, while emphasizing the need for institutional support and educating producers and consumers about sustainable consumption. Our research suggests that in our study area, these associative movements are beginning to be seen as an opportunity for the sale of products produced by small rural producers. Nonetheless, the AFNs still show a clear preference for operating in the urban area around the city of Granada in which they have managed to establish a strong presence. The dynamics of growth and innovation in this area allow them to build on what is already a significant accumulated social capital, thus making the metropolitan area the most competitive, most stable environment for these organizations. Meanwhile in rural areas with weaker demographic and socioeconomic structures such as the Alpujarra, the establishment of powerful organizations and the creation of social capital in relation to agriculture and food is much more limited. On the positive side, the arrival of new actors with neo-rural profiles could act as a stimulus for the introduction of new ideas in relation to agrifood and the promotion of associative projects in the Alpujarra.

In spite of the difficulties encountered by these organizations when trying to establish themselves in rural areas, there have been various success stories in the Alpujarra. These networks are well connected with the Granada network as a whole, which encourages one to think that these formulas will continue to be explored in the future. Indeed, the close interconnection and collaboration between the different AFNs in Granada encompasses not only those that operate in the metropolitan area but also the rural areas of the province such as the Alpujarra, which could be considered an important indicator of the degree of maturity achieved by these networks in the region. This could help increase the size of their target market and enable the introduction of local varieties from Alpujarra via a consolidated distribution network in expansion. As shown in this study, there are organizations that link together all of the AFNs in the province and share one of its best showcases, the Granada Eco-Market in which strong relations between the associations and the people of the province are forged.

Within the framework of these interrelations, the networks set up in rural areas can expand their field of action to regional, national, and even international spheres. Reaching European markets is something that the Las Torcas cooperative has already achieved. In the same way, together with the broad range of formulas for sale and marketing used by the AFNs, digital and online sales make it possible to reach a larger number of consumers and buying groups who could be attracted to the local varieties of a region, the Alpujarra, that enjoys its own clearly recognizable identity.

In spite of the opportunities that are beginning to appear, the truth is that most of the producers who work with AFNs come from periurban areas and are not always professional farmers who receive most of their income from agriculture. As such, they cannot be viewed as powerful references for producers in rural areas. The farmers in the Alpujarra who cultivate traditional varieties or would be prepared to do so do not have sufficient guarantees that their production could enter the market through these alternative distribution networks and prefer to take a more conservative approach, often selling their entire production to large cooperatives on the coast. For their part, the AFNs in operation today in the Alpujarra are especially focused on organic production and agroecology and have so far not shown much interest in the conservation and commercialization of local varieties.

Lastly, it is possible that if the farmers decide to cultivate these local products, presumably the supply will increase at a quicker rate than demand. The AFNs often have difficulties in absorbing all of the products produced by their farmer members or their regular suppliers, thus demonstrating their limited distribution capacity. This could be an important obstacle when it comes to creating trust among the farmers who also have to bear the additional costs associated with the cultivation of local varieties. As Bruce and Som [

66] point out, there are important obstacles that make the financial viability and social sustainability of alternative production methods more difficult to achieve. In general, in the associations and cooperatives we analyzed, advances in the scale at which they operate advances take place very slowly so as not to distort the projects in any way. It would therefore be difficult for producers in rural areas to view them as an alternative in the short term. Normally, these networks are designed not so much for rapid growth as for being replicated by others, and they expand by increasing the number of new small- and medium-sized units. In other words, the size of the entire network increases, although the size of the individual projects remains more or less stable. One innovative solution proposed in the literature to address the challenges of scale faced by AFNs in the distribution and consumption of local products is shared logistical infrastructures such as food hubs [

51,

67].

In conclusion, we believe that given the difficulties that local varieties face when trying to reach the conventional market, AFNs could provide an alternative distribution channel for these differentiated food products that form part of the biocultural heritage of peripheral rural territories such as the Alpujarra. This is because these organizations are not bound purely by economic interests and instead should be viewed as social movements with a strong commitment to a series of social and environmental values that could easily be extended to the protection of crop biodiversity, a form of heritage cultivated by local farmers for centuries. These networks are also spaces for innovation which are open to new proposals and challenges. The study highlights that in spite of their limited knowledge of local variety products, these organizations are receptive to the idea of working with them because they are optimistic about their future potential. Local varieties and locally sourced food form an integral part of the philosophy behind this new vision of agrifood systems. Furthermore, the Granada AFNs have achieved an important degree of maturity, as manifested in their long history in the agrifood sector and in the increasing complexity of their networked operations. This makes them expert agents with an in-depth knowledge of alternative markets and distributors of products with less conventional values. In addition, the local varieties would be produced in small volumes, a fact that also fits well with these business models for small-scale retail.

Nonetheless, we have also identified a long list of obstacles that stand in the way of AFNs becoming a solid outlet for the sale and distribution of local varieties. Among other questions referred to earlier is the fact that these farmers, especially those in more remote rural areas, are unsure as to whether to use these sales channels in that they do not offer sufficient guarantees for selling their entire harvest. Their commitment to these organizations is very fragile. In addition, the social fabric in rural areas is weaker and as a result, the AFNs tend to establish themselves around cities. For consumers and even for the managers of the associations, the difficulty with local varieties is that they know little about them or their properties. Another problem is our ingrained mindset when shopping, which directs us towards products with a more regular, more attractive appearance in line with established conventional standards.

While this study has achieved its exploratory objectives, it would be desirable in future research to continue investigating the capacity of AFNs to act as an outlet for these specific local products, analyzing in depth both the positions of the farmers involved in these networks and the potential consumers so as to provide more solidly grounded evidence. We suggest three key directions for future research. Firstly, to study the AFNs that operate with local varieties so as to identify the logistical difficulties that they encounter when working with food products of this kind. Secondly, the analysis of the decision-making system of small farmers and the weight of the different factors that lead to the abandonment of local variety crops, and thirdly, the study of the motivations of consumers for shopping for local varieties.

Given the importance of transferring our results to local society, we could conclude by saying that our research shows that the AFNs could provide a sales outlet for the local varieties of the Alpujarra, although without depending exclusively on them as the sole distribution channel. On a trial basis, the farmers could increase their production of the varieties with the most potential and distribute them through the available short-supply channels, with the support of a campaign by public institutions to promote the benefits of these varieties.