Abstract

The growing food waste phenomenon is recognised as a global issue with significant social, economic, and environmental burdens. This is a major concern in developed nations, where consumers are the largest contributors to the total volume of food waste production. As a leading cause of food and water insecurity, economic inequality, and environmental degradation, preventing and minimising consumer food waste is a key objective for policymakers and practitioners. Due to the complex consumer behaviours and practices associated with food waste generation, current understandings of why food waste occurs remain scattered. The purpose of this review is therefore to map the history and development of consumer food waste research over time, highlighting key themes and inconsistencies within the existing literature. Adopting a narrative approach, the literature is organised into three distinct themes to explore and identify the various internal and external determinants of consumer food waste. Our analysis highlights consumer food waste as a complex and multi-faceted challenge which cannot be attributed to one single variable, but rather a combination of behaviours determined by various societal, individual, and behavioural factors. While previous research tends to frame food waste as mainly a consumer issue, this review identifies several collective actors who are central to the problem. These findings call for a holistic view across the food supply chain to help identify opportunities for multi-stakeholder actions that prevent and reduce food waste at the consumer level. Drawing upon these new insights, we provide practical recommendations to assist policymakers, retailers, and consumers in mitigating consumer-related food waste.

1. Introduction

Food waste (FW) represents one of the biggest global challenges facing contemporary society. As globalisation drives the trends in urbanisation, increased wealth, market liberalisation and foreign direct investment, the subsequent redefinition of consumer tastes drives demand for greater food availability and diversity [1] While food supply chains are growing to fulfil this demand, the extended journey from farm to table has increased the volume of food lost or wasted at each stage [2]. Estimates suggest that approximately 1.3 billion tonnes of food is wasted each year, equal to around one-third of all food produced for human consumption [3,4,5]. Such vast quantities of waste provoke a number of environmental, social and ethical burdens, including unsustainable resource exploitation; water scarcity; land degradation; increased greenhouse gas emissions; higher food prices; and food insecurity [3,6,7] Minimising FW is directly linked to enhancing environmental and food security as well as food justice. FW mitigation is therefore recognised as a complex global issue, which must be prioritised by the multiple actors and institutions operating within the food supply system [8].

While the number of peer-reviewed articles reporting on FW have markedly increased over the last 10 years, there are still significant knowledge gaps surrounding this issue of global environmental importance. Such knowledge gaps relate to identifying which intervention strategies are most effective at minimising FW along the supply chain and throughout consumption [5]. Studies must further focus on addressing the cross-cultural dynamics of FW behaviours across all societies to allow for targeted interventions to be situation-specific and custom-made to address its underlying determinants [4,9]. Additionally, studying choice architecture, specific consumer groups and consumption profiles, and developing a standard method for identifying behavioural characteristics remain crucial areas of investigation for FW research [9,10]. Schanes et al. [7] outline that there remains a relative dearth of research on the subject of consumer-generated food waste in the context of private households. Specifically, little is known about the determinants of consumer FW practices and the underlying factors that facilitate, maintain, or impede food waste behaviours and practices [7,11,12]

Consequently, further study is necessary should issues of food loss and food wastage be addressed, and to ensure that environmental, social, and economic objectives are met. In so doing, this narrative review undertakes an in-depth analysis of the existing body of consumer FW literature, exploring the various factors influencing consumer FW behaviours both in-store and at home. This narrative review explores the determinants of consumer food waste practices by reviewing selected peer-reviewed articles between 2010 and 2023. Three key determinants are presented, namely individual, societal, and behavioural. These determinants are then narratively reviewed. This is followed by strategic recommendations for policy and practice, which aim to support pro-environmental behavioural changes that prevent and reduce FW at the consumer level.

2. Contextualising Determinants of Consumer Food Waste Practices

Defining FW is a contentious topic, with definitions often established on a situational basis due to difficulties in defining what constitutes FW, at which stage of the supply chain it originates, and how it is created and discarded [13]. Consequently, there is not yet a standardised, legal, or universally accepted definition. According to the FAO [3], FW is delimited by two notions, namely food losses and food wastage. While food losses tend to occur during the production, post-harvest, processing and distribution stages of the supply chain, losses incurred throughout the retail and consumption stages are typically recognised as food waste [14]. FW is therefore regarded as an issue relating to consumer behaviour, attitudes, and habits [14,15,16].

The role of consumers within the FW issue is especially pertinent in developed nations, where households are responsible for contributing approximately 53% of the total food wasted throughout the supply chain [17]. A recent US study found the average American household wastes 31.9% of total food purchases, generating economic losses valued at $240 billion per year [18]. In the UK, volumes of domestic FW equate to 6.6 million tonnes, 70% of which is generally still fit for consumption [2].

The drivers of consumer FW behaviours are manifold; many of which are deeply embedded within the routines of daily life [19]. Consumers not only waste a large proportion of food when performing food-related routines associated with storage, preparation, cooking, serving, and disposal [20], but their purchasing behaviours and perceptions of food have a significant influence on stakeholder decisions throughout the supply chain [21]. Downward development is possible, however, with FW reduction being facilitated through specific actions such as policy regulations and information campaigns [22]. To mitigate consumer FW, it is critical to gain an in-depth understanding of the many internal (e.g., attitudes, emotions, motivations) and external (e.g., social norms, information campaigns, infrastructures) factors that enable or prevent sustainable consumer FW practices.

To push consumers’ waste reduction efforts, synergistic actions are required between policymakers, societal stakeholders, and retailers [19]. An analysis of the existing body of consumer FW research can therefore assist policymakers in implementing well-defined regulations, developing suitable infrastructures, and designing appropriate interventions to improve consumers’ understanding of the FW issue and promote sustainable practices. A deeper understanding of this issue will also benefit food marketers and retailers, whose efforts can be streamlined and optimised to focus on modifying or eliminating the in-store practices which increase consumer FW.

3. Methodology

In preparation for the narrative review, a preliminary literature search was conducted to identify the existing body of consumer FW research. This confirmed that a sufficient number of research papers were available for analysis. To identify reputable articles, the ABS 2018 Academic Journal Guide was used to curate a selection of highly ranked peer-reviewed academic journals to target. These journals included the Journal of Cleaner Production, Journal of Consumer Behaviour, International Journal of Consumer Studies and the British Food Journal. For the topic in question, it was also necessary to include the following non-ABS ranked journals: Appetite, Sustainability, and Resources, Conservation and Recycling.

To ensure the review remained feasible, it was necessary to set specific parameters for the literature search. Key concepts related to the topic were therefore converted into search terms, or keywords, to define the scope of the search (see Table 1). Several selection criteria were also employed to permit the retrieval of all relevant studies and eliminate outdated papers. These criteria involved peer-reviewed articles, for which full-text were available, published in English, and dated between 2010 and 2023. The usage of Boolean operators (presented in Table 1) facilitated a more precise search and enabled a combination of descriptive keywords and synonyms to be included. Once established, the keywords and selection criteria were entered into the Bournemouth University’s ‘mySearch’ search engine to locate relevant articles. Each search yielded between 3 and 789 articles. Additional searches were conducted through the ScienceDirect and JSTOR databases to provide a reasonable breadth of coverage and depth on the topic.

Table 1.

Keywords and search terms.

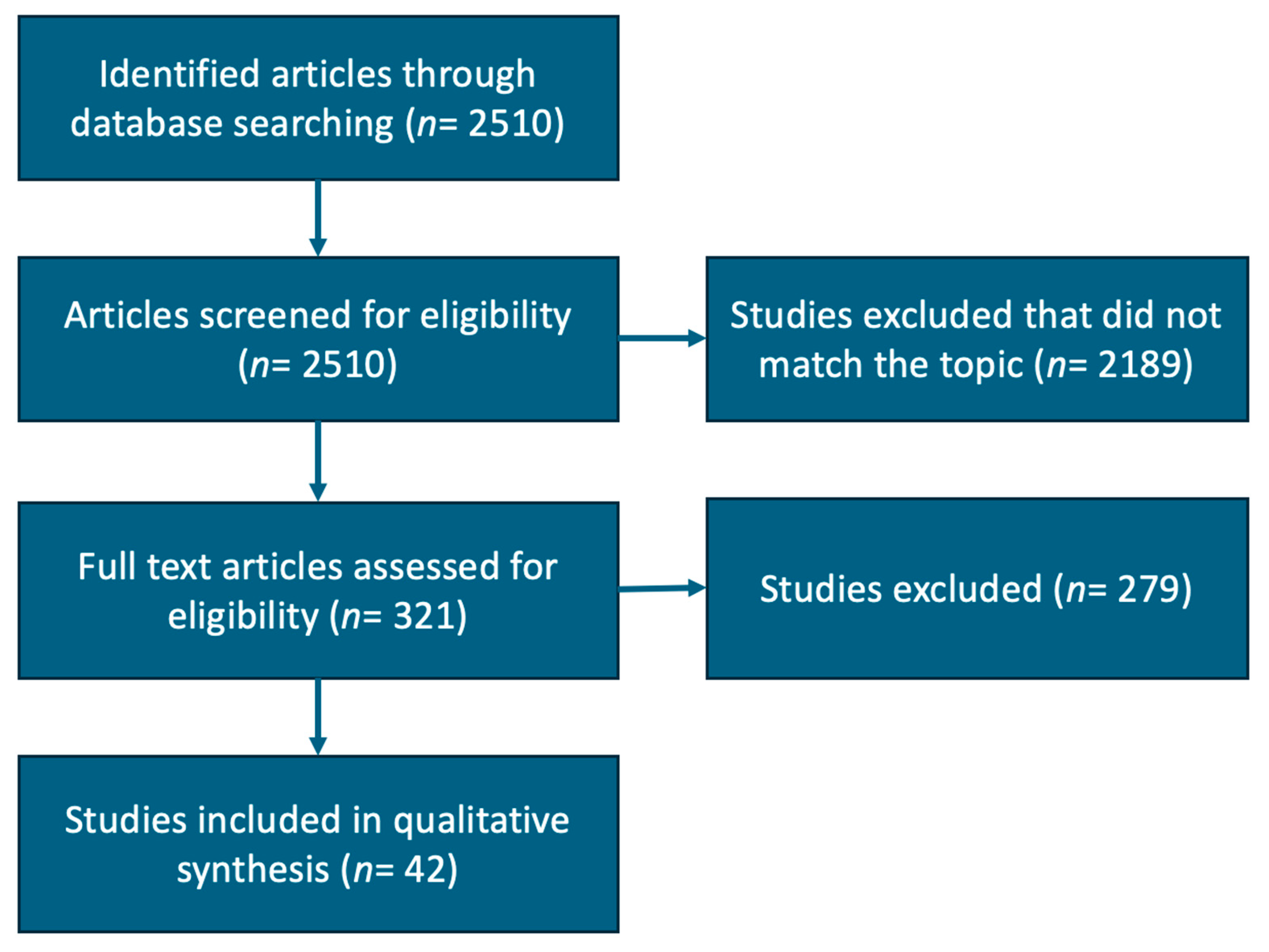

Once the primary bulk of articles were obtained, additional studies were identified through a manual search among the most cited references. The selection was subsequently refined by discarding any non-empirical studies and critically evaluating the suitability of each article based on the rigour of empirical methods, the interpretation and quality of results, and the impact of contributions in the field. The number of papers was ultimately reduced from 279 to 42. The process of selecting articles for inclusion are outlined in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The process of narrative review followed in this study.

A narrative literature review has been selected to provide a history and trace the development of consumer-related food waste practices over time. The purpose of this is to gather the published research in this field and provide a comprehensive, critical, and objective analysis of the existing literature [23]. In so doing, a narrative review offers a summary of the general debates within the existing body of knowledge and highlights the gaps or inconsistencies to be addressed in future research [24]. A systematic review has a clearly defined question with pre-defined protocols and selection criteria, identifying clear inclusion and exclusion criteria used to select studies for review [25]. In contrast, a narrative review relies primarily on the authors’ intuition and research experience, and may not have strict inclusion and exclusion criteria. Rather, a simple description of the selection criteria is provided, along with a description of study findings [25]. Though systematic reviews are based on data and may be viewed as more objective, narrative reviews may contain biases or omissions by the authors’ subjective intention [25]. To overcome some of the inherent biases, a description of the search criteria and a brief overview of the selection criteria are presented above, with a diagrammatic representation of the process followed in this study (Figure 1). Despite these biases, there are inherent advantages that narrative reviews demonstrate that systematic reviews may fail to capitalise upon; for example, narrative reviews are valuable for providing broad overviews of topics in a rapid time frame and useful for generating new ideas and research questions [26,27].

Unlike a systematic review, a narrative review is not restricted by a pre-determined research question [28]. A narrative review provides a synthesis of the literature without using quantitative methods; therefore, the limitations of this approach lie in its interpretive–qualitative nature [24]. There is potential for misleading conclusions to arise from various sources, including selection bias, the subjective evaluation of selected studies, and unspecified inclusion criteria [29]. Unlike quantitative reviews, however, which have narrowly defined parameters and limited selection rules, narrative reviews offer increased flexibility and the potential inclusion of individual insights and speculations [24]. The ability of a narrative review to consider the personal nature of the research process therefore permits the generation of a wider and more inclusive picture of the existing literature [24].

4. Determinants of Consumer Food Waste Practices

Food waste is still a developing and emerging field of research, providing fruitful opportunities to explore the interlinkages between the various stages of the food supply chain. In this narrative review, an organising template for the existing research is provided. Identified from previous systematic literature reviews [5,9,10,30], this template has been organised around three emergent streams of research, namely the societal, individual, and behavioural factors influencing consumer FW behaviours. Like Li et al. [30], we structure our results of the narrative review by identifying the societal, individual, and behavioural determinants of food waste.

The research within each stream is methodologically similar, with the literature mainly dominated by qualitative research. The most common methods of data collection are surveys, followed by interviews and focus groups. While these studies offer depth and detailed insights into the underlying reasons behind consumer FW, they are also more time consuming and resource intensive. It should therefore be noted that these studies are often limited to smaller samples, which presents challenges for generalising these findings to a wider population [31]. Moreover, the research findings cannot be generalised universally due to the differences in culture which influence consumer behaviour [32]. Issues with validity and reliability are also a major criticism, as qualitative analysis is subjective in nature and open to interpretation [31]. Other studies have attempted to quantify the consumer–FW relationship through FW diaries. However, a drawback of the FW diary method is the reliance on self-reported behaviour which can be prone to social desirability bias [33]. Drawing on research which highlights FW as an emotional topic, it is also likely that some participants underestimated the volume and frequency of FW to adhere to accepted social norms [34].

4.1. Societal Factors

The first stream of societal factors examines the external and material contexts of influence on consumer FW behaviours, with a particular focus on supply chain and retail factors. This stream considers the influential factors which may be beyond consumers’ control, such as packaging attributes, marketing strategies, and supportive infrastructures. The selected studies are summarised in Table 2.

Table 2.

Societal factors: selected studies.

The importance of societal factors cannot be understated. Approximately one-quarter to one-third of food produced in the world is lost or wasted through the food supply chain [45]. In Canada, 40% of food is wasted, generating an economic loss of $31 billion each year [45]. Globally, the annual value of wasted food is estimated at $1 trillion from 2.5 billion tons of food [46]. Many elements within societal factors shape food waste, including packaging and package size [47,48,49]. These myriad elements are narratively reviewed in this section.

In the context of supply chain factors, packaging is recognised as a key barrier to FW reduction. The relationship between packaging and FW was investigated by Williams et al. [42] in a study of 61 Swedish households. The results of questionnaires and FW diaries indicated that 20 to 25% of domestic FW was attributed to packages that were oversized; difficult to empty; or expired. Interestingly, lower quantities of FW were reported in more environmentally conscious households, which suggests that information may promote positive behaviour changes towards FW reduction [42]. More recently, Williams et al. [43] developed this research to explore the FW–packaging relationship across various product categories. Employing interviews as an additional methodology, an analysis of 37 households confirmed that packaging design was a key driver of household FW. The role of packaging varied across categories; however, versatile packaging size and the provision of food safety information were two particular attributes which reduced FW across all categories [43].

There has also been interest in the utility of information campaigns designed to increase consumer awareness of the FW issue. The impacts of poor social marketing and a lack of environmental education were identified by Wakefield and Axon [12] as a barrier to minimising household FW in the UK. Based on a survey of 100 consumers, it was found that poor understandings of the FW issue hindered FW reduction. In addition, focus group discussions revealed that poor understandings were attributed to a lack of action from policymakers and practitioners to address the FW issue, which in turn, left individuals feeling confused and un-incentivised to act on their environmental concerns [12].

Retailers’ expertise and wide reach can influence consumer choice and food-related practices both in-store and at home. This was documented in a study by Young et al. [44], which examined the effectiveness of a UK retailer in reducing consumer FW through interventions. Over a 21-month period, customers’ self-reported FW data were tracked after exposure to waste reduction messages across various communication channels. The findings from 631 surveys indicated that repetitive interventions through combined communication channels had a significantly positive and long-term impact on FW reduction. This was also relevant in the case of participants who failed to recall any interventions, highlighting the wider influence of retailer-led FW initiatives [44].

Whilst raising consumer awareness of the FW issue is widely accepted as an effective means to support positive behaviour change, the most effective type of information to guide campaign design is not yet determined. To investigate this, Kim et al. [38] applied a mixed-method design to gather consumer insights into preferred target behaviours and campaign strategy. In this study of 658 Australian households, respondents expressed a preference for targeting leftover re-use behaviour and using technology as a core campaign strategy. An additional study by Neubig et al. [40] compared the influence of system versus action-related information on intentions to reduce FW in Belgium, Germany, and the UK. Based on 2248 survey responses, action-related information was found to significantly increase intentions to reduce FW, while system information had no effect. To clarify, knowledge about how to reduce FW (i.e., action-related) was more effective than knowledge related to the impact of FW (i.e., system-related) in supporting opportunities for positive FW behaviour change [40].

According to Mondéjar-Jimenez et al. [39], the effectiveness of FW interventions can be diminished by the situational factors which characterise the context of purchase. These authors distributed surveys among 380 consumers in Italy and Spain to explore the effects of marketing strategies on FW behaviours [39]. The findings indicated that sales tactics had a direct negative influence on consumer FW behaviours, highlighting the important role of retailers in preventing FW generation. Specifically, sales promotions and product layouts were linked to excess purchases in-store, which contributed to FW generation in domestic settings [39].

Interestingly, some studies have demonstrated the ways in which marketing strategies can reduce consumer-related FW and encourage the acceptance of suboptimal products. For example, de Hooge et al. [36] conducted an online choice experiment to assess the factors influencing preferences for suboptimal products among 4214 Northern European consumers. The findings indicated that price discounts increased the willingness to purchase and consume products which varied in shape, best-before dates, or damaged packaging. However, participants required higher discounts for items which deviated in colour, as these items were perceived as unattractive, unsafe to consume, and unpalatable [36]. Additionally, van Giesen and de Hooge [41] explored the influence of positioning strategies on the acceptance of suboptimal food in the Netherlands. Based on a purchase pricing experiment involving 1804 consumers, it was found that positioning suboptimal goods to highlight genuineness, origin or naturalness (i.e., authenticity positioning) was most effective at increasing purchase intentions and quality perceptions. Conversely, positioning suboptimal goods in a manner which emphasised sustainable aspects (i.e., sustainability positioning) required moderate price discounts to be effective [41].

Whilst raising awareness and offering economic incentives are key measures to prevent and reduce household FW, some authors argue that FW cannot solely be attributed to consumers’ individual decision making. Like Mondéjar-Jimenez et al. [39], Dobernig and Schanes [37] investigated how the contextual factors framing food-related routines contribute towards household FW in Austria. Assessing the influence of retail infrastructures on in-store and household food practices, qualitative data were gathered from 24 households via FW diaries, interviews, and focus groups [37]. The findings indicated that consumers’ food-related routines were shaped by the characteristics of food retail infrastructures. In particular, a high density of accessible retail outlets was found to increase shopping frequency, which in turn prevented excess purchases and reduced the volume of food purchased per trip. Moreover, high shopping frequency reduced the likelihood of expiration resulting from prolonged storage, and thus, decreased the likelihood of domestic FW [37].

Similarly, Bernstad [35] conducted a case study of 1632 Swedish households to investigate the role of supportive infrastructures on household FW separation behaviour. Employing waste weights in a repeated treatment design, Bernstad [35] measured the effects of written information and the installation of waste segregation equipment on domestic FW generation. While the findings indicated that informational leaflets had no significant effect on FW quantities or source separation, the amounts of collected FW increased by 49% after the installation of segregation equipment. These findings therefore emphasised the importance of accessibility to, and convenience of, supportive infrastructures to promote consumer engagement with FW reduction behaviours [35].

Li et al. [30] summarise the societal determinants of FW in their review. They outline that the distance of retailers from storage warehouses increases FW along the distribution chain. Yet, Li et al. [30] also found that awareness campaigns, effective management of market facilities, packaging formats, and legislation and regulations have reducing effects on FW. Packaging formats have been explored in depth, and minimising large and unnecessary packaging, specifically individually wrapped items, has been revealed to dramatically reduce FW and broader wasteful behaviour [45,47].

4.2. Individual Factors

The second stream of research considers the individual factors influencing consumer-related FW. These factors are intrinsic to individual consumers, such as socio-demographic and psychographic variables. In this stream, Ajzen’s Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) is a commonly applied framework to predict behavioural intentions. This theory postulates that intentions to engage in a particular behaviour are predicted by three factors, namely attitudes; subjective norms; and perceived behavioural control (PBC) [50]. Strong intentions to perform a behaviour are formed when attitudes are positive, subjective norms are favourable, and PBC is high [50]. Selected studies are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Individual factors: selected studies.

The predictive power of socio-demographic variables with regard to household FW generation is unclear. For example, the influence of socio-demographic factors on FW generation was investigated in Finland by Koivupuro et al. [54]. The results of a FW diary study and questionnaire from 380 households found that household size was clearly correlated with domestic FW quantities—the more occupants in a household, the more FW was generated. In a per capita context, single occupant households wasted more than other household types, particularly single females [54]. In addition, FW was considerably higher in households where females were primarily responsible for grocery shopping. Conversely, no correlation was detected between FW and the variables of age, area and type of residence, educational level, and occupation [54].

Similarly, Grasso et al. [52] examined the socio-demographic predictors of consumer FW behaviours in Denmark and Spain. Based on a survey of 3029 consumers, Grasso et al. [52] confirmed that household size was positively correlated with FW behaviours in Denmark. However, in terms of gender, males in Denmark reported more FW behaviours than females [54]. This discrepancy suggests that the gender–FW relationship varies between country, and thus, findings cannot be generalised to all nations. Grasso et al. [52] also observed a relationship between FW and the variables of age and unemployment status; in both countries, less FW behaviour was linked to being older, unemployed, and in part-time employment. Despite this, these variables only explained little of the variance in FW behaviours, and Grasso et al. [52] subsequently concluded that socio-demographics are only modest predictors of consumer FW.

Adopting a psychology-oriented approach to explain FW behaviours, Graham-Rowe et al. [51] applied an extended TPB model to predict intentions to reduce household FW in the UK. In addition to the core TPB constructs, the model was augmented to include self-identity, anticipated regret, moral norm, and descriptive norm. Based on 204 survey responses, the findings confirmed that the extended TPB model accounted for 64% of the variance in intentions to reduce FW, with the core TPB variables, anticipated regret, and self-identity emerging as the most significant determinants.

In a similar vein, Visschers et al. [57] investigated the determinants of FW in Switzerland using an extended TPB model. This model adopted the typical TPB constructs, with the additional determinants of food knowledge, household planning habits, personal norms, and the good provider identity. Based on a survey of 796 consumers, the findings confirmed that the TPB was a useful predictor of household FW [57]. The good provider identity and personal norms regarding FW also emerged as additional key predictors. Interestingly, it was also revealed that some individuals experienced conflicting attitudes in regard to FW. For example, some individuals held negative attitudes and norms towards FW; however, they often discarded food due to health concerns over consuming leftovers or expired items. Similarly, while some individuals had intentions to minimise FW, their attempts were hindered by a desire to be a good provider and prepare sufficient amounts of food for the household [57].

Conversely, Stefan et al. [56] contested the use of intentions as a proxy measure of FW behaviour. This exploratory study investigated whether combining psychological variables with food-related routines offered a better predictive utility of household FW than psychological factors in isolation. A survey of 244 Romanian consumers found that planning and shopping routines were key predictors of FW, rather than intentions. These routines were influenced by moral attitudes (i.e., guilt) and PBC regarding the food-related routines of planning, shopping, and cooking [56]. Likewise, the exploratory power of intentional and routinised paths to FW behaviour were examined by Stancu et al. [56]. The results from a survey of 1062 Danish participants identified the main drivers of FW as PBC and routines related to shopping, leftover re-use, and planning.

Several studies have also illustrated the complex relationship between emotions and FW. Graham-Rowe et al. [11] conducted semi-structured interviews with 15 household purchasers to investigate the psychological motivations and barriers to domestic FW reduction in the UK. The findings identified two key motives for reducing FW, namely waste concerns and doing the ‘right’ thing. In addition, four barriers to minimising FW were also evident, including a ‘good’ provider identity; minimising inconvenience; low priority; and exemption from responsibility. Echoing findings by Visscher et al. [57], this research highlighted potential conflict between personal goals which hinder attempts to minimise household FW. It was subsequently suggested that these opposing motivations were “underpinned by the desire to avoid experiencing negative emotions” [11] (p. 21).

The finding that FW can evoke negative emotions was also documented by Jagau and Vyrastekova [53]. In this observational study, 2156 Dutch university students were exposed to an informational campaign designed to trigger emotional responses towards, and stimulate awareness of, the FW issue. The messages encouraged individuals with smaller appetites to request reduced servings. During the campaign, observational findings indicated that consumers were more likely to ask for smaller portions at the same price of standard portions. Moreover, 62 responses from a post-experiment survey revealed that approximately 50% of participants experienced negative emotions of guilt and shame when reflecting on FW behaviours, which were associated with intentions to reduce FW by requesting smaller servings [53].

Similarly, Russell et al. [34] underscored the importance of emotions as predictors of intentions and behaviours to minimise FW. Over a 14-month period, questionnaire data were collected from 172 UK participants to measure emotions related to FW, habits, the TPB constructs, intentions to reduce FW, and self-reported FW behaviours. In contrast to Jagau and Vyrastekova [53], however, Russell et al. [34] found that negative emotions were positively correlated with higher levels of FW behaviours. These findings therefore demonstrate that negative emotional experiences do not necessarily translate intentions to reduce FW into actual behaviours [34].

Li et al. [30], in their review, indicate that women preparing or eating food and higher incomes have increasing effects on FW, while awareness, feelings of guilt, social norms, and environmental concerns have a reducing effect. Furthermore, Li et al. [30] found that age, high educational attainment, and household size and composition have uncertain or unclear effects depending on the variable being studied. Vittuari et al. [10], in their systematic review, outline various factors that act as drivers of FW, specifically awareness, attitudes, and emotions. While some of these drivers are familiar to previous studies, outlining emotional components, e.g., healthy relationships with and enjoyment of food, indicates specific engagements with food quantity and quality.

4.3. Behavioural Factors

The third research stream explores the behavioural factors directly influencing the food-related routines and practices carried out by consumers in retail and domestic settings. These factors encompass various stages within the purchase and consumption cycle, such as planning, purchasing, storage, preparation, consumption, and disposal. Selected studies are outlined in Table 4.

Table 4.

Behavioural factors: selected studies.

In the context of food planning, insufficient planning behaviours are generally considered a barrier to FW reduction. Jörissen et al. [63] assessed the influence of household food-related behaviours on FW generation in 404 Italian and German households. In both countries, survey results identified shopping list use as a key behaviour linked to lower quantities of FW [63]. This ties in with research by Di Talia et al. [61], which investigated the FW knowledge of Italian consumers. Based on questionnaire data, Di Talia et al. [61] categorised a sample of 213 consumers into distinct consumer profiles. ‘Non-aware’ consumers were careless about household FW and were unable to recognise the negative implications associated with wasted food. Among this group, failure to use a shopping list was linked to unnecessary purchases in-store [61]. Conversely, ‘conscious’ consumers were concerned by the FW issue and actively adopted virtuous behaviours to reduce household FW, such as using a shopping list to avoid making unnecessary purchases [61].

The finding that unplanned purchasing was linked to negative in-store behaviours was also documented by Bravi et al. [59]. In this comparison study, the factors affecting household FW were assessed in Italy, Spain, and the UK. Based on 3233 survey responses, the findings indicated that unplanned purchasing caused consumers to make impulsive and excess purchases in retail settings, particularly in the case of British consumers. Similarly, British consumers adopted the habit of checking date labels much less frequently than their Italian and Spanish counterparts. Conversely, leftover re-use emerged as a positive behaviour to prevent and reduce household FW in all countries [59].

Consumer FW behaviours are also underpinned by the knowledge and awareness of the FW issue. This was investigated by Principato et al. [67] in a study of 233 Italian youths. Similar to Di Talia et al. [61], questionnaire findings indicated that greater awareness and concern regarding the FW issue was linked to less FW and the use of shopping lists to plan purchases [67]. In contrast, participants’ inadequate knowledge to judge food edibility resulted in concerns over food freshness, which in turn were linked to higher volumes of FW [67]. Likewise, a series of 12 interviews and 17 observations conducted by Farr-Wharton et al. [62] identified three factors causing FW behaviours in Australian households. First, poor supply knowledge was linked to a tendency to overprovision and stockpile. Second, poor location knowledge linked to improper storage resulted in food items being misplaced, forgotten, and eventually expired before consumption. Finally, poor food literacy hindered consumers’ ability to draw upon existing knowledge and use sensory perceptions to assess food edibility [62].

In a similar vein, Parizeau et al. [65] investigated the household dynamics of FW production in Canada. Data obtained from 68 households via waste weights and surveys revealed that conscientiousness regarding FW and its impacts was linked to lower volumes of FW production. The most commonly wasted food among this sample was trim from food preparation, followed by spoiled food items [65]. In addition, the most common approach to determine food edibility was to assess appearance and odour, followed by date labels. Interestingly, the findings indicated that households using multiple criteria to assess food edibility had more rationale to categorise food as waste, which subsequently led to more household FW [65].

While many consumers rely on date labels to assess food edibility, inconsistency in label practices often leads to widespread confusion and misinterpretation of label meanings. This was observed in a study by Davenport et al. [60], which examined the relationship between product characteristics and household FW in the US. A survey of 169 consumers confirmed that individuals frequently rely on institutional (i.e., date labels) signals to assess food safety and quality; however, these signals were not well understood [60]. The date-label phrases ‘best by’ and ‘use by’ had a negative effect on household food utilisation, reflecting consumers’ concerns over foodborne illnesses and an over-reliance on date labels to guide decision-making relating to food disposal [60]. These findings therefore provide strong evidence that uncertainties in label interpretation can lead to edible food being prematurely discarded. This was confirmed in a later study by Kavanaugh and Quinlan [64], which conducted a survey of 1042 US consumers to assess knowledge and behaviours regarding date labelling and FW. While the findings indicated that 81.6% of participants regularly referred to food date labels, only 37.2% were able to correctly define ‘sell by’, ‘best before’, and ‘use by’ dates [64]. Furthermore, 58.3% of respondents stated that they would dispose of food which still appeared edible, but was not worth consuming due to the potential health risks involved. In line with Davenport et al. [60], Kavanaugh and Quinlan’s [64] research emphasises the need to reduce consumer confusion through standardised labelling practices, and address concerns with consuming foods of diminished quality through date-labelling education.

To understand the FW issue on a wider scale, Porpino et al. [66] investigated the antecedents of household food disposal in a developing country context. In this research, empirical data were gathered from 14 Brazilian households via observations, interviews, photographs and focus groups. The findings revealed that excess purchases, over-preparation, and leftover avoidance were key drivers of FW, which were explained by the influence of cultural aspects such as hospitality and a good provider identity [66]. Similar to Farr-Wharton et al. [62], improper storage relating to a lack of knowledge was identified as an additional antecedent. Interestingly, many households dealt with over-preparation by offering leftovers to pets, which was subsequently not perceived as wastage [66]. The drivers of household FW in an emerging country context were also assessed by Aschemann-Witzel et al. [58]. Exploring the causes of FW in Uruguay, qualitative survey data were gathered from 540 households. The main reasons for food disposal among this sample were sub-optimality, prolonged storage, and excess leftovers. This confirms consumers’ concerns regarding food safety [60,64], tendencies to over-prepare [66], and overprovision [62,66].

Summarising key behavioural determinants, Li et al. [30] found that over-purchasing food, the sensory preference of freshness or taste, and large serving sizes had increasing effects on FW, while knowledge of food production being translated into practice, accessibility to cooking fuels, and refrigerator ownership had reducing effects on FW. With respect to actively reducing FW, many interventions have been successful. Reynolds et al. [68] identify that plate size interventions resulted in an up to 57% FW reduction, while information campaigns had up to 28% reduction. Identifying effective interventions has been a crucial area of research [69,70]. Read and Muth [71], for example, identify four interventions, including awareness campaigns, the standardisation of date labels, food waste tracking services, and spoilage prevention packaging to have substantial environmental impacts with reduced food wastage.

5. Implications and Recommendations

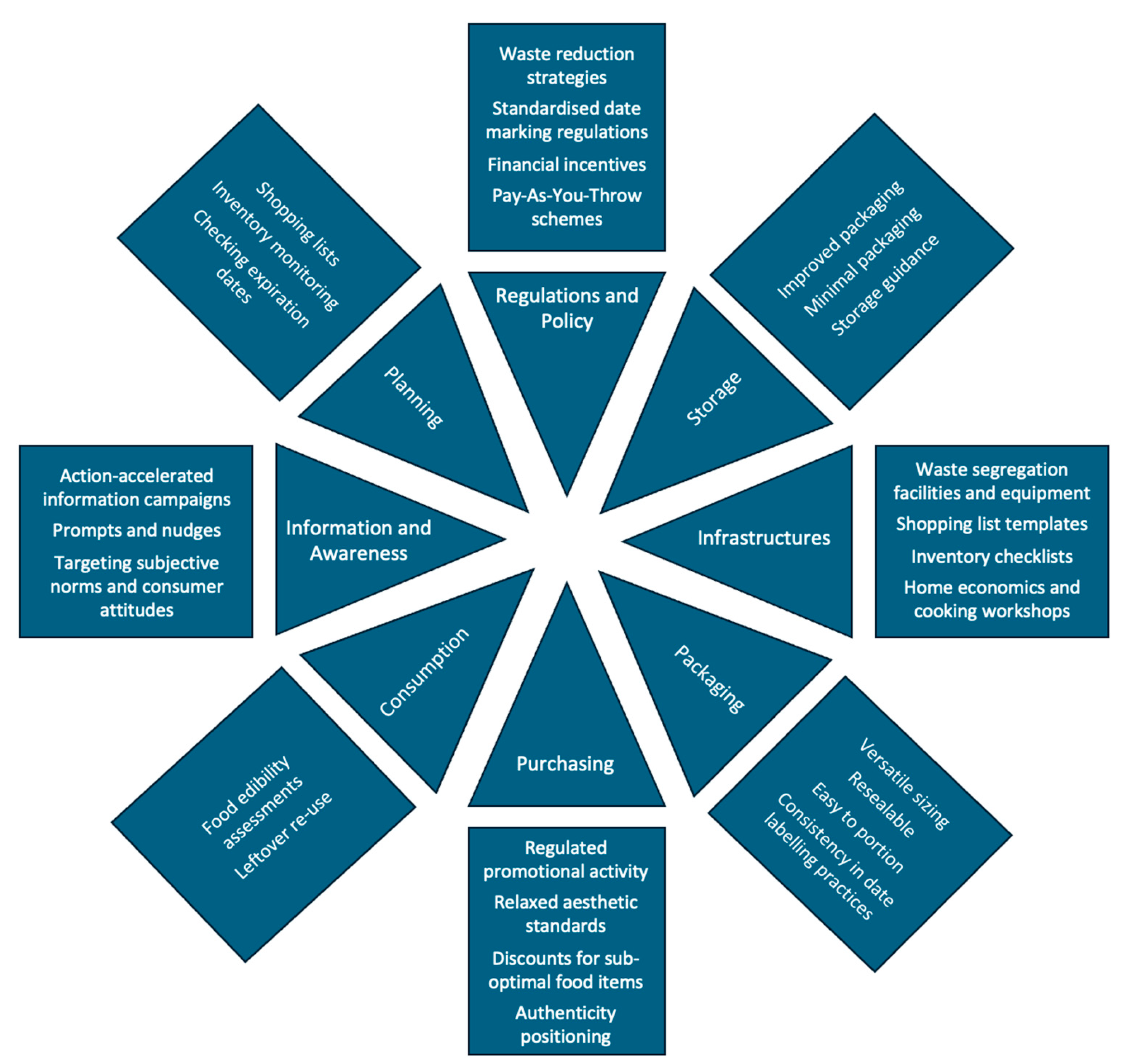

The integrated narrative review explored the nature of the key determinants influencing consumer FW behaviours. To identify distinct themes within the existing body of consumer FW research, the selected studies are organised into three streams, namely societal; individual; and behavioural factors. Societal and individual factors are considered to directly impact behavioural factors. While these streams approach the topic from different perspectives, they offer complementary and overlapping insights into the drivers of consumer FW behaviours. In this section, these insights are translated into practical implications that will assist policymakers and practitioners in designing effective solutions to combat consumer FW. The key drivers of consumer-related FW and recommendations for strategic action are outlined in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Food waste drivers and strategic recommendations.

It is clear from the literature review that consumer FW mitigation requires multi-stakeholder collaboration and a combination of FW prevention measures. First and foremost, policymakers must introduce regulatory approaches such as waste reduction targets. These approaches have already been introduced in various European countries, such as France’s National Pact Against Food Waste, which aims to achieve a 50% reduction in FW by 2025 [71,72]. Additionally, it is critical for policymakers to establish clear regulations on date marking. Inconsistent and ambiguous date-label practices are responsible for widespread confusion, premature food disposal, and increasing FW at the consumer level [60,64]. To circumvent this issue and promote improved understandings, date-label terminologies must be clearly defined and standardised.

While FW prevention should remain the key priority, a significant amount of FW is unavoidable. However, a sustainable method of extracting value from this waste is to convert recycled FW into renewable energy and fertiliser [73]. It is therefore recommended that local governments mandate institutional changes in FW collection schemes and provide supportive infrastructures (e.g., composting caddies and bags). There is evidence to suggest that consumer participation in recycling activities can be sustained over longer-term timelines when infrastructures are convenient and accessible [35]. Furthermore, it is also likely that financial incentives could encourage consumers to reduce household FW. For example, reductions in FW have been observed when household FW generation is charged using “Pay-As-You-Throw” (PAYT) weight-based fee systems [74,75]. In addition to economic (dis)incentives such as PAYT schemes, technological innovations such as smart refrigerators, food-tracking services, and digital platforms for food sharing are further interventions that could be established to complement economic incentives [71].

Retailers can support consumer FW reduction by altering their marketing strategies. This includes marketing promotions such as “buy one get one free”, which negatively influence FW behaviours by encouraging consumers to purchase more than they require [39]. While it is possible for policymakers to directly regulate and ban these activities, a more collaborative approach is for retailers to take voluntary action and develop their own regulations. This has been trialled by UK retailer Tesco with a “buy one, get one free later” scheme, which allowed consumers to claim their free product at a later date and avoid unused items expiring at home. Retailers can also employ price reductions as a strategy to clear excess stocks and encourage the consumption of suboptimal goods [36]. Several UK supermarkets observed an increase in sales after relaxing aesthetic standards and introducing “wonky” fruit and vegetable boxes at a reduced price. Such initiatives may also generate more favourable consumer responses when an authenticity positioning strategy is used to highlight the genuineness, origin, or naturalness of suboptimal products [41].

Packaging attributes such as size, design, and information must also be optimised to help consumers reduce household FW. This includes packaging improvements which support FW reduction through functionalities such as being easy to portion, serve, and re-seal [42,43]. Moreover, packaging labels should serve as information touchpoints to educate consumers about date-label usage and support their assessments of food edibility. Similarly, food labels can also communicate the environmental impacts associated with the respective food’s production. This information can increase consumer awareness about FW and its consequences.

Consumers’ poor understanding of the FW issue stems from a lack of policymaker and practitioner action [12]. Yet, a greater awareness of FW and its consequences is linked to reduced volumes of household FW [61,67]. This necessitates a multi-stakeholder approach, where government, industry, and consumers share responsibility and action for FW mitigation efforts. Consequently, stakeholders must take action to develop information campaigns which increase consumer FW knowledge, shape positive FW attitudes, and increase intentions to perform FW reduction behaviours. When conducted on a repetitive basis through combined channels of communication, information campaigns can have positive long-term impacts on household FW reduction [44]. Graham-Rowe et al. [51] and Visschers et al. [57] suggested that intentions to reduce FW are predicted by subjective norms and attitudes towards FW. Future interventions may therefore benefit from directly targeting these determinants, such as strengthening the belief that FW is bad, avoidable, and immoral [57].

The effectiveness of information campaigns can be enhanced when combined with alternative forms of intervention, such as prompts and nudges [71,76]. Such interventions can offer consumers a shortcut solution to mitigate their planning insufficiencies [53] and enable them to prioritise FW reduction over other personal goals [77]. This is especially pertinent given Graham-Rowe et al. [11] identified conflicting personal goals as a barrier to FW reduction. The underlying cause of consumers’ conflicting motivations is an inclination to avoid negative emotions such as guilt and shame [11,53]. Based on the finding that FW can evoke negative emotions, it may seem effective to utilise guilt appeals as a motivational tool to encourage FW reduction. Conversely, Russell et al. [34] found that negative emotional experiences did not translate intentions to reduce FW into actual behaviours. Adopting a purely negative approach in campaign design is therefore not advised, as such appeals can induce compensation behaviours to mitigate negative emotions, including denials of personal responsibility or severity of the issue itself [77].

Stakeholders should consider collective investment into consumer education campaigns to improve knowledge and awareness regarding FW prevention. Neubig et al. [40] demonstrated that action-related information is most effective in supporting opportunities for consumer behaviour change. Education campaigns should therefore aim to enhance consumers’ skills and knowledge to improve their management of food-related routines [55,56]. With regard to meal planning, consumers must learn how to accurately plan meals and prevent overbuying [51,59,63]. Efforts should therefore be directed towards giving consumers the practical tools required to manage their planning routines, such as providing shopping list templates and inventory checklists. Moreover, it is crucial to educate consumers on date-label meanings and storage practices to improve their assessments of food safety and edibility [62,64,65]. Household economics and cooking courses can also help reduce FW by improving consumers’ cooking skills and providing recipe ideas for leftover re-use [38,58,59].

6. Conclusions

Food waste is a global issue with direct implications for food security, environmental sustainability, and economic growth. In this narrative review, three contributing factors influencing consumer FW have been discussed, namely societal; individual; and behavioural factors. The literature offers strong evidence to suggest that consumer FW stems from a complex set of behaviours, which are determined by various internal and external factors. Specifically, consumer FW is influenced by motivations (i.e., awareness, attitude, and subjective norms), opportunities (i.e., access to supportive infrastructures), and capabilities (i.e., knowledge and skills) to manage FW behaviours.

A contemporary culture of overconsumption has led FW to be framed as mainly a consumer issue, with responsibility for FW reduction primarily placed on consumers themselves. However, this review has identified a number of collective actors central to the issue. This finding exemplifies the need for collaborative action from all stakeholders to mitigate global FW. Application of the knowledge gained during this review has provided a number of actionable recommendations for minimising FW at the consumer level. This includes adopting an integrated approach to FW reduction through improved policy regulations, supportive infrastructures, retail marketing practices, information interventions, and education campaigns. It is hoped that developing these strategies will drive a change in societal mentality, improve consumer understandings and attitudes towards the FW issue, and positively reinforce FW reduction behaviours to combat FW at the consumer level.

Many systematic reviews have been, and continue to be, conducted on elements of food waste. This article applied a narrative review to identify key determinants of consumer food waste. In doing so, a distinctive approach to reviewing the societal, individual, and behavioural determinants of consumer food waste is therefore presented. Few narrative reviews are published, given the perception that they lack the rigour that systematic reviews have. Yet, the value of a narrative review is that they develop clear implications and future research strategies on a topic.

To that end, we underscore that there are clear avenues for future research that deserve further attention. Firstly, further narrative reviews are essential. Many areas of FW scholarship have relied on systematic reviews [69], though identifying the effectiveness and application of FW interventions in various geographic locations is an understudied area of investigation that warrants further study. Secondly, many studies on FW are dependent upon a Theory of Planned Behaviour model [10,78] which may not elicit the broader socio-cultural, socio-material, and socio-historical contexts of FW. Therefore, new conceptual frameworks such as social practice theoretical approaches may identify additional determinants of consumer food waste practice that have yet to be identified. Thirdly, many consumer-related empirical studies are not fully comparable due to the adoption of different measurement approaches. This is a clear avenue for joint academic and practitioner research and practice to focus on to facilitate comparisons between different consumer groups and cultural aspects. Fourthly, and finally, identifying which policy interventions reap the best results in terms of FW reduction remains surprisingly under-researched and necessitates further attention. This is particularly important if a social practice theoretical approach is taken, removing the need for the individual to act, as policy interventions and legislation steer practices towards more sustainable products and services [9]. This is a particularly valuable area of research and practice, given that ‘nudges’ are often applied to reduce FW as a strategy yet are often inconsistently applied. These areas of future research have the potential to unlock further understandings of how FW can be further reduced to minimise environmental and economic losses.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- FAO. Globalization of Food Systems in Developing Countries: Impact on Food Security and Nutrition; FAO Food and Nutrition Paper No. 83; Food and Agricultural Organisation of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2004; pp. 1–26. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/a-y5736e.pdf (accessed on 9 August 2022).

- WRAP. Food Surplus and Waste in the UK—Key Facts. Oxon: Waste & Resources Action Programme. 2020. Available online: https://wrap.org.uk/sites/files/wrap/Food_%20surplus_and_waste_in_the_UK_key_facts_Jan_2020.pdf (accessed on 28 September 2022).

- FAO. Global Food Losses and Food Waste: Extent, Causes and Prevention; Food and Agricultural Organisation of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2011; Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/a-i2697e.pdf (accessed on 11 August 2022).

- Dou, Z.; Toth, J.D. Global primary data on consumer food waste: Rate and characteristics—A review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 168, 105332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Principato, L.; Mattia, G.; Di Leo, A.; Pratesi, C.A. The household wasteful behaviour framework: A systematic review of consumer food waste. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2021, 93, 641–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papargyropoulou, E.; Lozano, R.; Steinberger, J.K.; Wright, N.; bin Ujang, Z. The food waste hierarchy as a framework for the management of food surplus and food waste. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 76, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schanes, K.; Dobernig, K.; Gözet, B. Food waste matters—A systematic review of household food waste practices and their policy implications. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 182, 978–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, L.G.; Keller, P.A.; Vallen, B.; Williamson, S.; Birau, M.M.; Grinstein, A.; Haws, K.L.; LaBarge, M.C.; Lamberton, C.; Moore, E.S.; et al. The Squander Sequence: Understanding Food Waste at Each Stage of the Consumer Decision-Making Process. J. Public Policy Mark. 2016, 35, 292–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijuniclair, J.; dos Santos, A.S.; da Silveira, D.S.; da Costa, M.F.; Duarte, R.B. Consumer behaviour in relation to food waste: A systematic literature review. Br. Food J. 2021, 124, 4420–4439. [Google Scholar]

- Vittuari, M.; Herrero, L.G.; Masotti, M.; Iori, E.; Caldeira, C.; Qian, Z.; Bruns, H.; van Herpen, E.; Obersteiner, G.; Kaptan, G.; et al. How to reduce consumer food waste at household level: A literature review on drivers and levers for behavioural change. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2023, 38, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham-Rowe, E.; Jessop, D.C.; Sparks, P. Identifying motivations and barriers to minimising household food waste. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2014, 84, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakefield, A.; Axon, S. “I’m a bit of a waster”: Identifying the enablers of, and barriers to, sustainable food waste practices. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 275, 122803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gjerris, M.; Gaiani, S. Food Waste and Consumer Ethics. In Encyclopedia of Food and Agricultural Ethics; Kaplan, D.A., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherland, 2019; pp. 1312–1318. [Google Scholar]

- Parfitt, J.; Barthel, M.; McNaughton, S. Food waste within food supply chains: Quantification and potential for change to 2050. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2010, 365, 3065–3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeliotis, K.; Lasaridi, K.; Chroni, C. Attitudes and behaviour of Greek households regarding food waste prevention. Waste Manag. Res. 2014, 32, 237–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Principato, L. Food Waste at Consumer Level: A Comprehensive Literature Review; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Estimates of European Food Waste Levels. Stockholm: European Union. 2016. Available online: https://www.eu-fusions.org/phocadownload/Publications/Estimates%20of%20European%20food%20waste%20levels.pdf (accessed on 13 August 2022).

- Yu, Y.; Jaenicke, E.C. Estimating Food Waste as Household Production Inefficiency. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2020, 102, 525–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebrok, M.; Boks, C. Household food waste: Drivers and potential intervention points for design—An extensive review. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 151, 380–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quested, T.E.; Marsh, E.; Stunell, D.; Parry, A.D. Spaghetti soup: The complex world of food waste behaviours. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2013, 79, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschemann-Witzel, J.; De Hooge, I.; Amani, P.; Bech-Larsen, T.; Oostindjer, M. Consumer-related food waste: Causes and potential for action. Sustainability 2015, 7, 6457–6477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WRAP. Household Food and Drink Waste in the United Kingdom 2012. Final Report. Oxon: Waste & Resources Action Programme. 2012. Available online: https://www.wrap.org.uk/sites/files/wrap/hhfdw-2012-main.pdf.pdf (accessed on 28 September 2022).

- Baumeister, R.F.; Leary, M.R. Writing Narrative Literature Reviews. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 1997, 1, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, M. The SAGE Encyclopedia of Communication Research Methods; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pae, C.-U. Why systematic review rather than narrative review? Psychiatry Investig. 2015, 12, 417–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, B.N.; Johnson, C.D.; Adams, A. Writing narrative literature reviews for peer reviewed journals: Secrets of the trade. J. Chiropr. Med. 2006, 5, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, A.T.; Denniss, A.R. An introduction to writing narrative and systematic reviews—Tasks, tips, and traps for aspiring authors. Heart Lung Circ. 2018, 27, 893–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, J.A. Improving the peer review of narrative literature reviews. Res. Integr. Peer Rev. 2016, 1, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumrill, P.D., Jr.; Fitzgerald, S.M. Using narrative literature reviews to build a scientific knowledge base. Work 2001, 16, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Bremer, P.; Harder, M.K.; Lee MS, W.; Parker, K.; Gaugler, E.C.; Mirosa, M. A systematic review of food loss and waste in China: Quantity, impacts and mediators. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 303, 114092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denzin, N.; Lincoln, Y. Handbook of Qualitative Research; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Howitt, D.; Cramer, D. Research Methods in Psychology; Pearson Education: Essex, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Paulhus, D.L. Two-component models of socially desirable responding. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1984, 46, 598–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, S.V.; Young, C.W.; Unsworth, K.L.; Robinson, C. Bringing habits and emotions into food waste behaviour. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 125, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstad, A. Household food waste separation behavior and the importance of convenience. Waste Manag. 2014, 34, 1317–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Hooge, I.E.; Oostindjer, M.; Aschemann-Witzel, J.; Normann, A.; Loose, S.M.; Almli, V.L. The apple is too ugly for me! Consumer preferences for suboptimal food products in the supermarket and at home. Food Qual. Prefer. 2017, 56, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobernig, K.; Schanes, K. Domestic spaces and beyond: Consumer food waste in the context of shopping and storing routines. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2019, 43, 480–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Rundle-Thiele, S.; Knox, K.; Burke, K.; Bogomolova, S. Consumer perspectives on household food waste reduction campaigns. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 243, 118608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondéjar-Jiménez, J.-A.; Ferrari, G.; Secondi, L.; Principato, L. From the table to waste: An exploratory study on behaviour towards food waste of Spanish and Italian youths. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 138, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubig, C.M.; Vranken, L.; Roosen, J.; Grasso, S.; Hieke, S.; Knoepfle, S.; Macready, A.L.; Masento, N.A. Action-related information trumps system information: Influencing consumers’ intention to reduce food waste. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 261, 121126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Giesen, R.I.; de Hooge, I.E. Too ugly, but I love its shape: Reducing food waste of suboptimal products with authenticity (and sustainability) positioning. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 75, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, H.; Wikström, F.; Otterbring, T.; Löfgren, M.; Gustafsson, A. Reasons for household food waste with special attention to packaging. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 24, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, H.; Lindström, A.; Trischler, J.; Wikström, F.; Rowe, Z. Avoiding food becoming waste in households—The role of packaging in consumers’ practices across different food categories. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 265, 121775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, C.W.; Russell, S.V.; Robinson, C.A.; Chintakayala, P.K. Sustainable Retailing—Influencing Consumer Behaviour on Food Waste. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2018, 27, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, T.; Durif, F.; Robinot, E. Can eco-design packaging reduce consumer food waste? an experimental study. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 162, 120342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recycling Tracking Systems. Food Waste in America in 2024. 2024. Available online: https://www.rts.com/resources/guides/food-waste-america/ (accessed on 17 September 2024).

- Petit, O.; Lunardo, R.; Rickard, B. Small is beautiful: The role of anticipated food waste in consumers’ avoidance of large packages. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 113, 326–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, L.; Langley, S.; Verghese, K.; Lockrey, S.; Ryder, M.; Francis, C.; Phan-Le, N.T.; Hill, A. The role of packaging in fighting food waste: A systematized review of consumer perceptions of packaging. J. Consum. Prod. 2021, 281, 125276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, R.B.Y. Drivers of divergent industry and consumer food waste behaviours. The case of reclosable and resealable packaging. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 412, 137417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham-Rowe, E.; Jessop, D.C.; Sparks, P. Predicting household food waste reduction using an extended theory of planned behaviour. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2015, 101, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasso, A.C.; Olthof, M.R.; Boevé, A.J.; van Dooren, C.; Lähteenmäki, L.; Brouwer, I.A. Socio-Demographic Predictors of Food Waste Behavior in Denmark and Spain. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagau, H.L.; Vyrastekova, J. Behavioral approach to food waste: An experiment. Br. Food J. 2017, 119, 882–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koivupuro, H.; Hartikainen, H.; Silvennoinen, K.; Katajajuuri, J.; Heikintalo, N.; Reinikainen, A.; Jalkanen, L. Influence of socio-demographical, behavioural and attitudinal factors on the amount of food waste generated in Finnish households. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2012, 36, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stancu, V.; Haugaard, P.; Lähteenmäki, L. Determinants of consumer food waste behaviour: Two routes to food waste. Appetite 2016, 96, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefan, V.; van Herpen, E.; Tudoran, A.A.; Lähteenmäki, L. Avoiding food waste by Romanian consumers: The importance of planning and shopping routines. Food Qual. Prefer. 2013, 28, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visschers, V.H.M.; Wickli, N.; Siegrist, M. Sorting out food waste behaviour: A survey on the motivators and barriers of self-reported amounts of food waste in households. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 45, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschemann-Witzel, J.; Giménez, A.; Ares, G. Household food waste in an emerging country and the reasons why: Consumer’s own accounts and how it differs for target groups. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 145, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravi, L.; Francioni, B.; Murmura, F.; Savelli, E. Factors affecting household food waste among young consumers and actions to prevent it: A comparison among UK, Spain and Italy. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 153, 104586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, M.L.; Qi, D.; Roe, B.E. Food-related routines, product characteristics, and household food waste in the United States: A refrigerator-based pilot study. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 150, 104440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Talia, E.; Simeone, M.; Scarpato, D. Consumer behaviour types in household food waste. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 214, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farr-Wharton, G.; Foth, M.; Choi, J.H. Identifying factors that promote consumer behaviours causing expired domestic food waste. J. Consum. Behav. 2014, 13, 383–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jörissen, J.; Priefer, C.; Bräutigam, K. Food Waste Generation at Household Level: Results of a Survey among Employees of Two European Research Centers in Italy in Germany. Sustainability 2015, 7, 2695–2715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavanaugh, M.; Quinlan, J.J. Consumer knowledge and behaviors regarding food date labels and food waste. Food Control. 2020, 115, 107285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parizeau, K.; von Massow, M.; Martin, R. Household-level dynamics of food waste production and related beliefs, attitudes, and behaviours in Guelph, Ontario. Waste Manag. 2015, 35, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porpino, G.; Parente, J.; Wansink, B. Food waste paradox: Antecedents of food disposal in low-income households. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2015, 39, 619–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Principato, L.; Secondi, L.; Praseti, C.A. Reducing food waste: An investigation on the behaviour of Italian youths. Br. Food J. 2014, 117, 731–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, C.; Goucher, L.; Quested, T.; Bromley, S.; Gillick, S.; Wells, V.K.; Evans, D.; Koh, L.; Kanyama, A.C.; Katzeff, C.; et al. Review: Consumption-stage food waste reduction interventions—What works and how to design better interventions. Food Policy 2019, 83, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casonato, C.; García-Herrero, L.; Caldeira, C.; Sala, S. What a waste! Evidence of consumer food waste prevention and its effectiveness. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2023, 41, 305–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simões, J.; Carvalho, A.; Gaspar de Matos, M. How to influence consumer food waste behaviour with interventions? A systematic literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 373, 133866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, Q.D.; Muth, M.K. Cost-effectiveness of four food waste interventions: Is food waste reduction a “win-win”? Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 168, 105448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourad, M. France Moves Toward a National Policy Against Food Waste. 2015. Available online: https://www.nrdc.org/sites/default/files/france-food-waste-policy-report.pdf (accessed on 28 September 2022).

- WRAP. Household Food and Drink Waste in the UK. 2009. Available online: https://wrap.org.uk/sites/files/wrap/Household_food_and_drink_waste_in_the_UK_-_report.pdf (accessed on 28 September 2022).

- Chalak, A.; Abou-Daher, C.; Chaaban, J.; Abiad, M.G. The global economic and regulatory determinants of household food waste generation: A cross-country analysis. Waste Manag. 2016, 48, 418–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahlén, L.; Lagerkvist, A. Pay as you throw: Strengths and weaknesses of weight-based billing in household waste collection systems in Sweden. Waste Manag. 2010, 30, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stöckli, S.; Niklaus, E.; Dorn, M. Call for testing interventions to prevent consumer food waste. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 136, 445–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Geffen, L.; van Herpen, E.; van Trijp, H. Household Food Waste—How to Avoid It? An Integrative Review. In Food Waste Management: Solving the Wicked Problem; Närvänen, E., Mesiranta, N., Matilla, M., Heikkinen, A., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 27–55. [Google Scholar]

- Deliberador, L.R.; Batalha, M.O.; César, A.d.S.; Azeem, M.M.; Lane, J.L.; Carrijo, P.R.S. Why do we waste so much food? Understanding household food waste through a theoretical framework. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 419, 137974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).