Can ESG Disclosure Stimulate Corporations’ Sustainable Green Innovation Efforts? Evidence from China

Abstract

1. Introduction

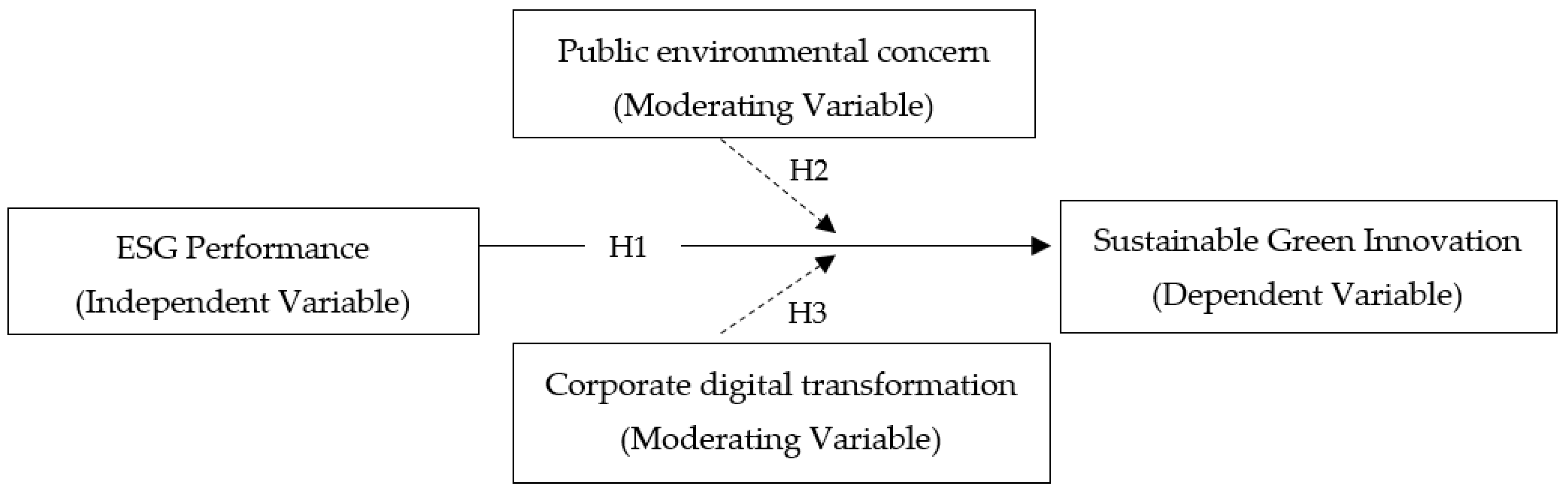

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. ESG Disclosure and Firms’ Sustainable Green Innovation

2.2. Moderation Effect of Public Environmental Concern (PEC) and Corporate Digital Transformation (CDT)

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Sample Selection and Data Sources

3.2. Variable Selection

3.2.1. Independent Variable

3.2.2. Dependent Variable

3.2.3. Moderation Variables

3.2.4. Control Variables

3.3. Empirical Model

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics Analysis

4.2. Regression Results and Analysis

4.3. Robustness Test

4.3.1. Alternative Independent Variable

4.3.2. Alternative Dependent Variable

4.3.3. Endogeneity Tests

5. Further Analysis: Heterogeneity Test and Moderation Effect Analysis

5.1. Heterogeneity Test

5.1.1. Heterogeneity Analysis on Firm Level

5.1.2. Heterogeneity Analysis on Regional Level

5.2. Moderation Effect Analysis

5.2.1. Informal External Pressure Moderation: Public Environmental Concern (PEC)

5.2.2. Internal Development Moderation: Corporate Digital Transformation (CDT)

6. Conclusions and Implications

6.1. Conclusions

6.2. Implications

6.3. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kim, S.; Yoon, A. Analyzing active fund managers’ commitment to ESG: Evidence from the United Nations Principles for Responsible Investment. Manag. Sci. 2023, 69, 741–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Yi, X.; Hu, K.; Lyulyov, O.; Pimonenko, T. The effect of ESG performance on corporate green innovation. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y.; Wu, W. How does green innovation improve enterprises’ competitive advantage? The role of organizational learning. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 26, 504–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintana-García, C.; Marchante-Lara, M.; Benavides-Chicón, C.G. Towards sustainable development: Environmental innovation, cleaner production performance, and reputation. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 1330–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Van der Linde, C. Toward a new conception of the environment-competitiveness relationship. J. Econ. Perspect. 1995, 9, 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flammer, C. Corporate social responsibility and shareholder reaction: The environmental awareness of investors. Acad. Manag. J. 2013, 56, 758–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, P.; Sautner, Z.; Tang, D.Y.; Zhong, R. The effects of mandatory ESG disclosure around the world. J. Account. Res. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, G.; Liu, Y.; Chen, F. Research on the impact of environment, society, and governance (ESG) on firm risk: An explanation from a financing constraints perspective. Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 58, 104038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giakoumelou, A.; Salvi, A.; Bekiros, S.; Onorato, G. ESG and FinTech funding in the EU. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2024, 69, 102233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Tian, M.; Yang, J.; Xu, G. Does environmental inspection led by the central government improve the air quality in China? The moderating role of public engagement. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Liu, X.; Ding, Y.; Wang, W. How does environmental regulation affect haze pollution governance? An empirical test based on Chinese provincial panel data. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 695, 133905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Diamond, J. China’s environment in a globalizing world. Nature 2005, 435, 1179–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Fan, C.; Chen, S. The impact of campaign-style enforcement on corporate environmental action: Evidence from China’s central environmental protection inspection. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 290, 125881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robiou du Pont, Y.; Rogelj, J.; Hsu, A.; Van Vuuren, D.; Hoepner, A.G. Corporate emissions targets and the neglect of future innovators. Science 2024, 384, 388–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Qin, X.; Liu, L. The interaction effect between ESG and green innovation and its impact on firm value from the perspective of information disclosure. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tidd, J.; Bessant, J.R. Managing Innovation: Integrating Technological, Market and Organizational Change; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 18–20. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.C.; Rasiah, R.; Furuoka, F. The corporate environmental and financial performance nexus: A comparison of corporations in China and Japan. Energy Effic. 2024, 17, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Yu, Y. An adoption-implementation framework of digital green knowledge to improve the performance of digital green innovation practices for industry 5.0. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 363, 132608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Li, Y. A study on the impact of digital transformation on corporate ESG performance: The mediating role of green innovation. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, R.V.; Rupp, D.E.; Williams, C.A.; Ganapathi, J. Putting the S back in corporate social responsibility: A multilevel theory of social change in organizations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 836–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Loh, L.; Wu, W. How do environmental, social and governance initiatives affect innovative performance for corporate sustainability? Sustainability 2020, 12, 3380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kanno, M. Does ESG performance improve firm creditworthiness? Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 55, 103894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.L.; Ahuja, G. Does it pay to be green? An empirical examination of the relationship between emission reduction and firm performance. Bus. Strategy Environ. 1996, 5, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhang, L.; Sun, J.; He, P. Can public participation constraints promote green technological innovation of Chinese enterprises? The moderating role of government environmental regulatory enforcement. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 174, 121198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Ho, K.C.; Yan, C.; Gozgor, G. Public environmental concern, CEO turnover, and green investment: Evidence from a quasi-natural experiment in China. Energy Econ. 2021, 100, 105379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Ren, Y. Public environmental concern and corporate ESG performance. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 61, 104991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, T.; Matt, C.; Benlian, A.; Wiesböck, F. Options for formulating a digital transformation strategy. MIS Q. Exec. 2016, 15, 123–139. [Google Scholar]

- Nambisan, S.; Wright, M.; Feldman, M. The digital transformation of innovation and entrepreneurship: Progress, challenges and key themes. Res. Policy 2019, 48, 103773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wu, Y.; Cao, D.; Wang, Y. Organizational mindfulness towards digital transformation as a prerequisite of information processing capability to achieve market agility. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 122, 700–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chu, E. Shifting focus from end-of-pipe treatment to source control: ESG ratings’ impact on corporate green innovation. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 354, 120409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Hu, H.; Hong, Z. Green finance policy, ESG rating, and cost of debt—Evidence from China. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2024, 92, 103051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H. ESG performance, investors’ heterogeneous beliefs, and cost of equity capital in China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 992559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Hou, W.; Liu, Z.; Yang, Z. How can public environmental concerns enhance corporate ESG performance?—Based on a dual perspective of external pressure and internal concerns. Sci. Sci. Manag. S. T. 2023, 1–28. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- McBrayer, G.A. Does persistence explain ESG disclosure decisions? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 1074–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Zhou, H.; Ding, J. Research on the impact of technological diversification on the persistence of innovation at firm-level. Stud. Sci. Sci. 2017, 35, 1896–1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Hu, D. Corporate ESG performance and innovation—Evidence from A-share listed companies. Econ. Res. J. 2023, 58, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Shi, M.; Liu, J.; Tan, Z. Public environmental concern, government environmental regulation and urban carbon emission reduction—Analyzing the regulating role of green finance and industrial agglomeration. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 924, 171549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, C.; Wang, W.; Li, X. How does digital transformation affect corporate total factor productivity? Financ. Trade Econ. 2021, 42, 114–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Hu, H.; Lin, H.; Ren, X. Corporate digital transformation and capital market performance—Evidence from stock liquidity. Manag. World 2021, 37, 130–144. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, D.; Liu, S.; Wang, Y. Market competition, property rights, and government subsidies. Econ. Res. J. 2013, 2, 13. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Y.; Zhu, Z. The effect of ESG rating events on corporate green innovation in China: The mediating role of financial constraints and managers’ environmental awareness. Technol. Soc. 2022, 68, 101906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Ruan, X. Digital transformation, green technology innovation, and corporate ESG performance—The moderating role of environmental regulation. J. Harbin Univ. Commer. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2023, 5, 34–47. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D. Can digital finance empowerment reduce extreme ESG hypocrisy resistance to improve green innovation? Energy Econ. 2023, 125, 106756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attig, N.; Boubakri, N.; El Ghoul, S.; Guedhami, O. Firm internationalization and corporate social responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 134, 171–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimson, E.; Karakaş, O.; Li, X. Active ownership. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2015, 28, 3225–3268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.J.; Lyu, X. Responsible multinational investment: ESG and Chinese OFDI. Econ. Res. J. 2022, 57, 83–99. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.; Luo, X.; Lu, W.-Z. Public perceptions of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) based on social media data: Evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 387, 135840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Xiao, Z. Heterogeneous Environmental Regulation Tools and Green Innovation Incentives: Evidence from Green Patents of Listed Companies. Econ. Res. J. 2021, 55, 192–208. Available online: https://kns.cn.jingshi2015.com/kcms2/article/abstract?v=IylmbgxpP4Rkd0jYN38Q1dBMmHoB4Vm56wVnyRqLmkpVC8ArzrQTAtxTn1wP9V6b75U4VFMCFvuLwk5za8LjyBCN01qxeLb7Z7QuUYdJhJumVfPlrIHCBbUGRCPvP3DqChqxHKa7Bl-v6cpxeB2jE5uYqQDJTMjkr3llSBVcU5k=&uniplatform=NZKPT (accessed on 25 October 2024). (In Chinese).

- Chouaibi, S.; Rossi, M.; Siggia, D.; Chouaibi, J. Exploring the moderating role of social and ethical practices in the relationship between environmental disclosure and financial performance: Evidence from ESG companies. Sustainability 2021, 14, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouaibi, S.; Affes, H. The effect of social and ethical practices on environmental disclosure: Evidence from an international ESG data. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2021, 21, 1293–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boons, F.; Lüdeke-Freund, F. Business models for sustainable innovation: State-of-the-art and steps towards a research agenda. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 45, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, D.; Wang, J.; Tang, Q. Has digital economy realized the “Increase of Quantity and Improvement of Quality” of green innovation. J. Shanxi Univ. Financ. Econ. 2023, 45, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardyment, R. Measuring Good Business: Making Sense of Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Data; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2024; pp. 188–238. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, F.; Koelbel, J.F.; Rigobon, R. Aggregate confusion: The divergence of ESG ratings. Rev. Financ. 2022, 26, 1315–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Zhong, Y.; Wu, Y. The Manifestation, Cause and Countermeasures of the Differences in ESG Rating at Home and Abroad. J. Univ. South China (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | Variable | Description |

|---|---|---|

| ESG_score | ESG Composite Rating | All listed companies were rated by ESG rating score |

| Innovation | Firms’ Sustainable Green Innovation | The year-over-year growth rate of (the total number of patent applications between years t − 1 and t) compared to (the total from years t − 2 to t − 1), multiplied by (the combined total of patent applications for years t − 1 and t). |

| Baidu_Index | Public Environmental Concern | Baidu Search Index—Daily Average |

| DIGI_score | Digital transformation | Using text analysis and expert scoring methods to measure. |

| tpq | Firm size | Tobin’s Q. |

| age | Firm age | The logarithm of the total days since the firm was first listed. |

| holder | Equity concentration | The proportion of shares owned by the 5 largest shareholders. |

| board | Number of directors | The log-transformed count of board directors. |

| hindex | Industry concentration | Measurement based on the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index. |

| gdp | GDP | The log value of the provincial GDP. |

| Firm | Firm control | Firm-specific fixed effects are accounted. |

| Year | Year control | Time-specific fixed effects are accounted. |

| Variable | Obs | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Innovation | 19,637 | 0.010 | 0.127 | 0.000 | 15.931 |

| ESG_score | 19,637 | 4.124 | 1.163 | 0.000 | 7.750 |

| Baidu_Index | 19,637 | 2.353 | 2.316 | 0.000 | 12.740 |

| DIGI_score | 19,637 | 0.140 | 0.347 | 0.000 | 5.890 |

| tpq | 19,637 | 0.022 | 0.065 | 0.006 | 7.296 |

| age | 19,637 | 10.351 | 7.752 | 1.000 | 32.000 |

| share | 19,637 | 5.527 | 1.613 | 0.000 | 9.847 |

| board | 19,637 | 8.583 | 1.802 | 0.000 | 21.000 |

| Hindex | 19,637 | 0.205 | 0.186 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| gdp | 19,637 | 1.073 | 0.029 | 0.946 | 1.164 |

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Innovation | 1 | |||||||||

| ESG_score | 0.151 *** | 1 | ||||||||

| Baidu_Index | 0.054 *** | 0.033 *** | 1 | |||||||

| DIGI_score | 0.149 *** | 0.076 *** | 0.246 *** | 1 | ||||||

| tpq | −0.077 *** | −0.151 *** | 0.078 *** | 0.078 *** | 1 | |||||

| age | −0.006 | −0.064 *** | 0.063 *** | 0.059 *** | −0.031 *** | 1 | ||||

| share | 0.021 *** | 0.137 *** | 0.043 *** | −0.097 *** | −0.121 *** | −0.204 *** | 1 | |||

| board | 0.060 *** | 0.055 *** | −0.057 *** | −0.105 *** | −0.137 *** | 0.104 *** | 0.090 *** | 1 | ||

| Hindex | −0.030 *** | −0.059 *** | 0.023 *** | 0.032 *** | 0.013 * | −0.042 *** | 0.066 *** | 0.029 *** | 1 | |

| gdp | −0.050 *** | 0.016 ** | −0.173 *** | −0.229 *** | 0.032 *** | −0.344 *** | 0.088 *** | 0.070 *** | 0.031 *** | 1 |

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Innovation | Innovation | Innovation | |

| ESG_score | 0.588 *** | 0.545 *** | 0.131 *** |

| (9.979) | (9.229) | (4.872) | |

| tpq | −0.041 *** | 0.005 | |

| (−4.351) | (0.672) | ||

| age | −0.050 | 0.040 | |

| (−1.383) | (0.783) | ||

| share | −2.986 | −5.175 | |

| (−0.297) | (−1.260) | ||

| board | 0.362 ** | 0.077 | |

| (2.167) | (1.145) | ||

| Hindex | −0.143 | −0.090 | |

| (−1.217) | (−1.167) | ||

| gdp | −2.957 *** | 1.280 | |

| (−5.036) | (1.593) | ||

| cons | −0.200 ** | 13.213 *** | −6.588 * |

| (−2.524) | (4.219) | (−1.697) | |

| N | 19,637 | 19,637 | 19,637 |

| adj. R-sq | 0.023 | 0.031 | 0.667 |

| Firm FE | No | No | Yes |

| Year FE | No | No | Yes |

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Innovation | Innovation | Innovation | |

| ESG_r | 0.083 *** | 0.088 *** | 0.088 *** |

| (5.920) | (5.373) | (7.059) | |

| tpq | −0.060 *** | −0.071 *** | |

| (−6.257) | (−7.354) | ||

| age | −0.113 *** | 0.016 | |

| (−3.004) | (0.412) | ||

| share | −4.639 | 7.116 | |

| (−0.449) | (0.908) | ||

| board | 0.324 * | 0.445 *** | |

| (1.852) | (3.674) | ||

| Hindex | −0.222 * | −0.049 | |

| (−1.830) | (−0.633) | ||

| gdp | −3.096 *** | 1.744 | |

| (−5.475) | (1.326) | ||

| cons | 0.494 *** | 14.848 *** | −9.983 |

| (12.431) | (4.919) | (−1.597) | |

| N | 19,637 | 19,637 | 19,637 |

| adj. R-sq | 0.014 | 0.026 | 0.200 |

| Firm FE | No | No | Yes |

| Year FE | No | No | Yes |

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patent | Patent | Patent | |

| ESG_score | 0.437 *** | 0.404 *** | 0.447 *** |

| (9.531) | (8.829) | (9.208) | |

| tpq | −0.032 *** | −0.041 *** | |

| (−4.820) | (−5.616) | ||

| age | −0.029 | 0.065 ** | |

| (−1.043) | (2.159) | ||

| share | 0.058 | 6.244 | |

| (0.008) | (1.154) | ||

| board | 0.266 ** | 0.332 *** | |

| (2.143) | (3.662) | ||

| Hindex | −0.071 | −0.024 | |

| (−0.751) | (−0.384) | ||

| gdp | −1.873 *** | 1.168 | |

| (−4.756) | (1.240) | ||

| _cons | −0.163 *** | 8.183 *** | −7.369 |

| (−2.665) | (3.894) | (−1.647) | |

| N | 19,637 | 19,637 | 19,637 |

| adj. R-sq | 0.023 | 0.031 | 0.210 |

| Firm FE | No | No | Yes |

| Year FE | No | No | Yes |

| Variable | (1) | (2) |

|---|---|---|

| ESG_Score | Innovation | |

| FundN | 0.001 *** | |

| (5.872) | ||

| FundV | 0.002 *** | |

| (4.889) | ||

| ESG_score | 0.986 ** | |

| (2.243) | ||

| tpq | −0.012 *** | 0.014 |

| (−4.251) | (1.422) | |

| age | −0.080 *** | 0.120 |

| (−8.019) | (1.536) | |

| share | 8.498 *** | −12.070 |

| (5.441) | (−1.547) | |

| board | −0.007 | 0.029 |

| (−0.293) | (0.366) | |

| Hindex | −0.051 *** | −0.027 |

| (−2.748) | (−0.386) | |

| gdp | 0.131 | 0.743 |

| (0.663) | (0.982) | |

| Firm FE | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes |

| N | 19,637 | 19,637 |

| Kleibergen–Paap rk LM statistic | 70.933 *** | |

| Kleibergen–Paap Wald rk F statistic | 46.656 *** | |

| Hansen J statistic | Chi-sq (1) p-val = 0.9862 | |

| Endogeneity test | Chi-sq (1) p-val = 0.0086 | |

| F | 46.656 | |

| Based on Industry | Based on Region | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Pollution | Key Pollution | Northeast | Eastern | Central | Western | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Innovation | Innovation | Innovation | Innovation | Innovation | Innovation | |

| ESG_score | 0.101 ** | 0.155 *** | 0.146 ** | 0.111 *** | 0.133 ** | 0.152 *** |

| (2.416) | (5.365) | (2.128) | (3.555) | (2.323) | (2.870) | |

| tpq | 0.029 *** | −0.002 | 0.015 | 0.002 | 0.019 | 0.001 |

| (3.146) | (−0.260) | (0.621) | (0.301) | (1.562) | (0.093) | |

| age | −0.167 *** | 0.105 *** | −0.405 *** | 0.022 | 0.045 | 0.234 *** |

| (−2.825) | (2.989) | (−3.764) | (0.595) | (0.649) | (2.890) | |

| share | 0.875 | −6.277 | 8.135 | −8.483 ** | −0.724 | 0.403 |

| (0.134) | (−1.592) | (0.562) | (−2.021) | (−0.093) | (0.050) | |

| board | 0.039 | 0.038 | 0.315 * | 0.040 | 0.189 | −0.008 |

| (0.398) | (0.633) | (1.668) | (0.600) | (1.636) | (−0.054) | |

| Hindex | 0.048 | −0.106 ** | −0.371 | −0.103 * | 0.008 | 0.010 |

| (0.323) | (−2.031) | (−1.437) | (−1.804) | (0.048) | (0.106) | |

| gdp | −1.526 | 2.338 *** | −3.085 * | 2.555 *** | 0.824 | −0.198 |

| (−1.547) | (3.524) | (−1.705) | (2.787) | (0.682) | (−0.136) | |

| _cons | 7.767 * | −10.565 *** | 14.672 * | −11.247 *** | −3.959 | 0.626 |

| (1.677) | (−3.393) | (1.736) | (−2.615) | (−0.697) | (0.093) | |

| N | 5384 | 13,939 | 1007 | 12,955 | 3021 | 2737 |

| adj. R-sq | 0.613 | 0.688 | 0.584 | 0.672 | 0.680 | 0.651 |

| Firm FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Variable | (1) | (2) |

|---|---|---|

| Innovation | Innovation | |

| ESG_score | 0.132 *** | 0.119 *** |

| (5.594) | (5.102) | |

| Baidu_Index | −0.005 | |

| (−0.194) | ||

| Baidu_Index × ESG_score | 0.032 | |

| (1.529) | ||

| DIGI_score | 0.039 *** | |

| (5.194) | ||

| DIGI_score × ESG_score | 0.057 *** | |

| (3.543) | ||

| tpq | 0.005 | 0.005 |

| (0. 937) | (0. 966) | |

| age | 0.036 | 0.028 |

| (1.244) | (0.982) | |

| share | −4.956 | −5.697 * |

| (−1.522) | (−1.224) | |

| board | 0.073 | 0.056 |

| (1.422) | (1.081) | |

| Hindex | −0.091 * | −0.091 * |

| (−1.945) | (−1.941) | |

| gdp | 1.224 ** | 1.179 ** |

| (2.266) | (2.182) | |

| _cons | −5.165 ** | −4.869 * |

| (−2.037) | (−1.920) | |

| N | 19,637 | 19,637 |

| adj. R-sq | 0.667 | 0.668 |

| Firm FE | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, M.; Rasiah, R. Can ESG Disclosure Stimulate Corporations’ Sustainable Green Innovation Efforts? Evidence from China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9390. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16219390

Li M, Rasiah R. Can ESG Disclosure Stimulate Corporations’ Sustainable Green Innovation Efforts? Evidence from China. Sustainability. 2024; 16(21):9390. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16219390

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Miao, and Rajah Rasiah. 2024. "Can ESG Disclosure Stimulate Corporations’ Sustainable Green Innovation Efforts? Evidence from China" Sustainability 16, no. 21: 9390. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16219390

APA StyleLi, M., & Rasiah, R. (2024). Can ESG Disclosure Stimulate Corporations’ Sustainable Green Innovation Efforts? Evidence from China. Sustainability, 16(21), 9390. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16219390