Quality Evaluation and Optimization of Idle Goods Swap Platform Based on Grounded Theory and Importance–Performance Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

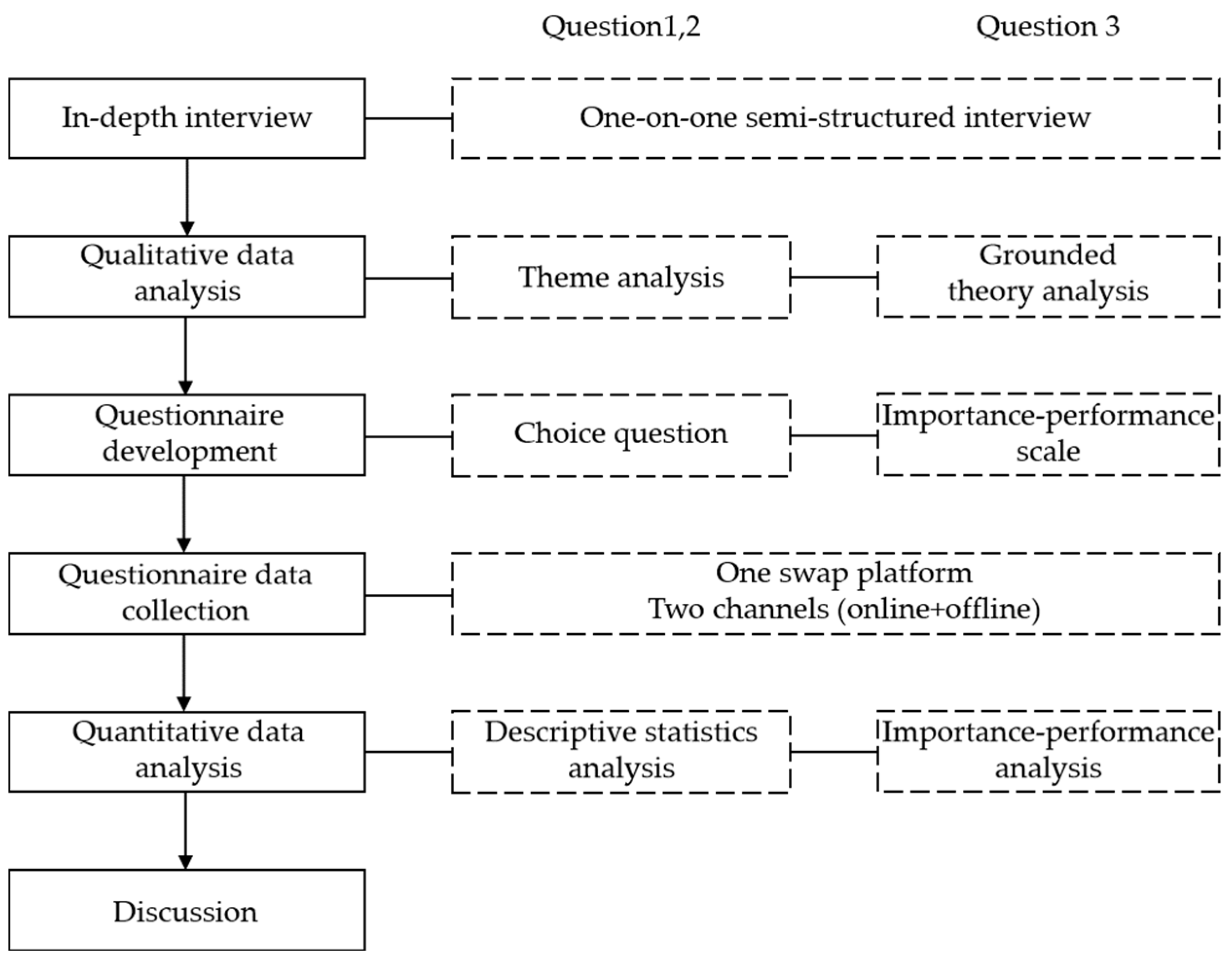

2.1. Procedure

2.2. Materials and Data Collection

2.2.1. Interview Design

2.2.2. Questionnaire Development

2.2.3. Participants and Data Collection

2.3. Analysis Methods

2.3.1. Grounded Theory

- (1)

- Open Coding

- (2)

- Axial Coding

- (3)

- Selective Coding

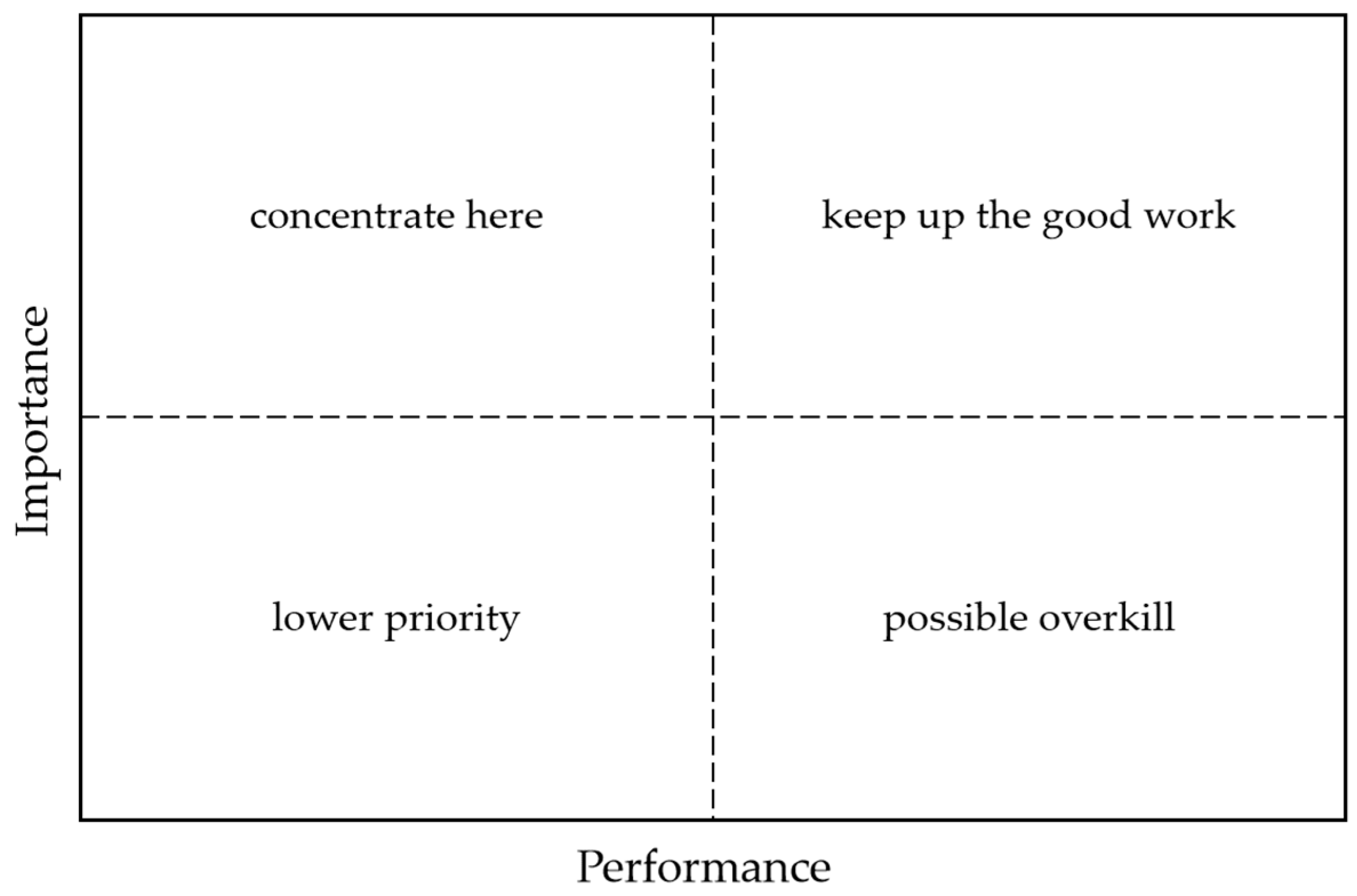

2.3.2. Importance–Performance Analysis

- (1)

- “Concentrate here” (high importance, low performance): The platform should focus on improving these areas.

- (2)

- “Keep up the good work” (high importance, high performance): The platform should continue its current efforts in these areas.

- (3)

- “Low priority” (low importance, low performance): The platform should allocate some effort to improve these areas gradually.

- (4)

- “Possible overkill” (low importance, high performance): The platform may have over-invested in these areas and could reduce investment if necessary.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Question 1: Characteristics of Swap Participants

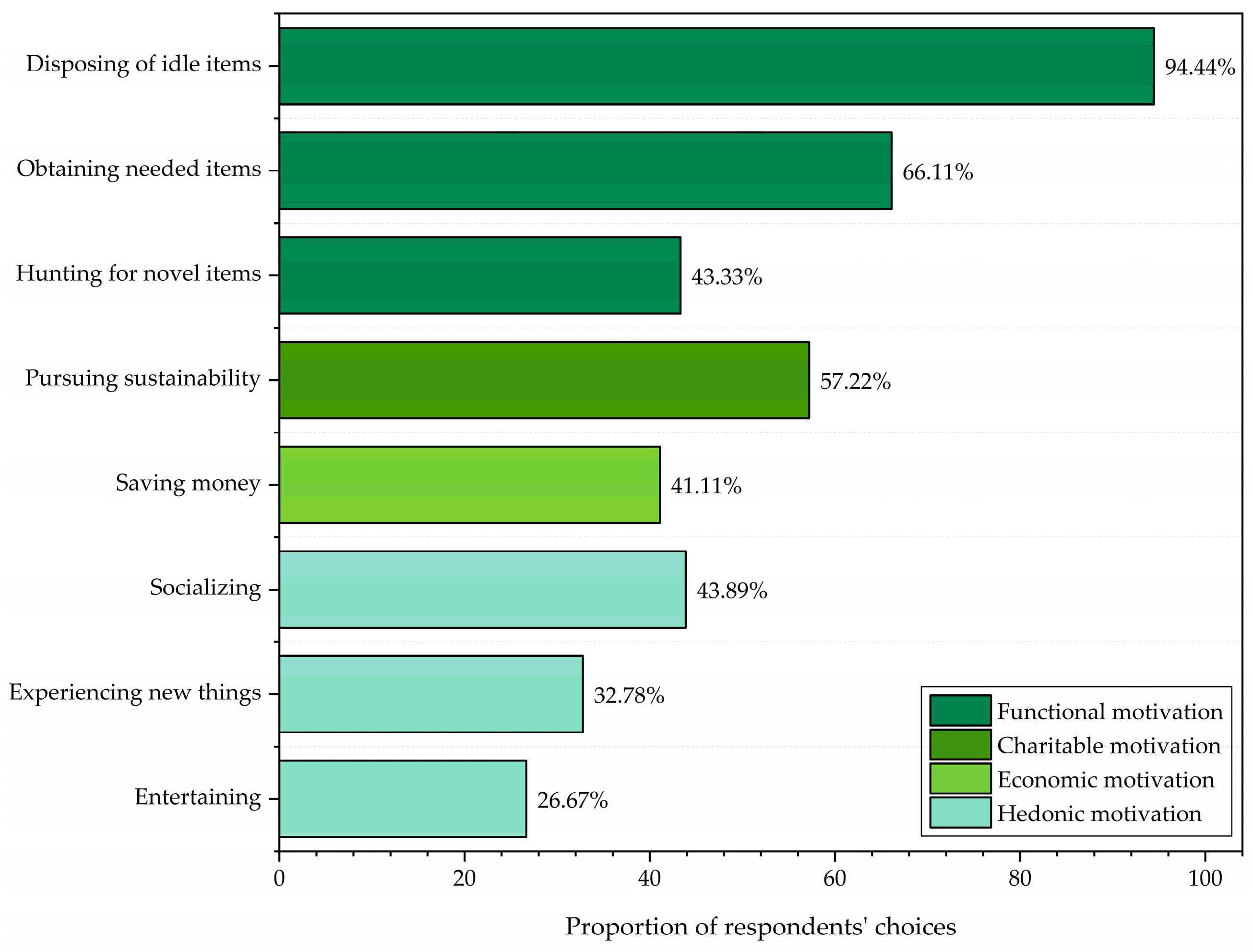

3.2. Question 2: Motivations for Participating in Swaps

3.3. Question 3: Quality Evaluation of Swap Platform

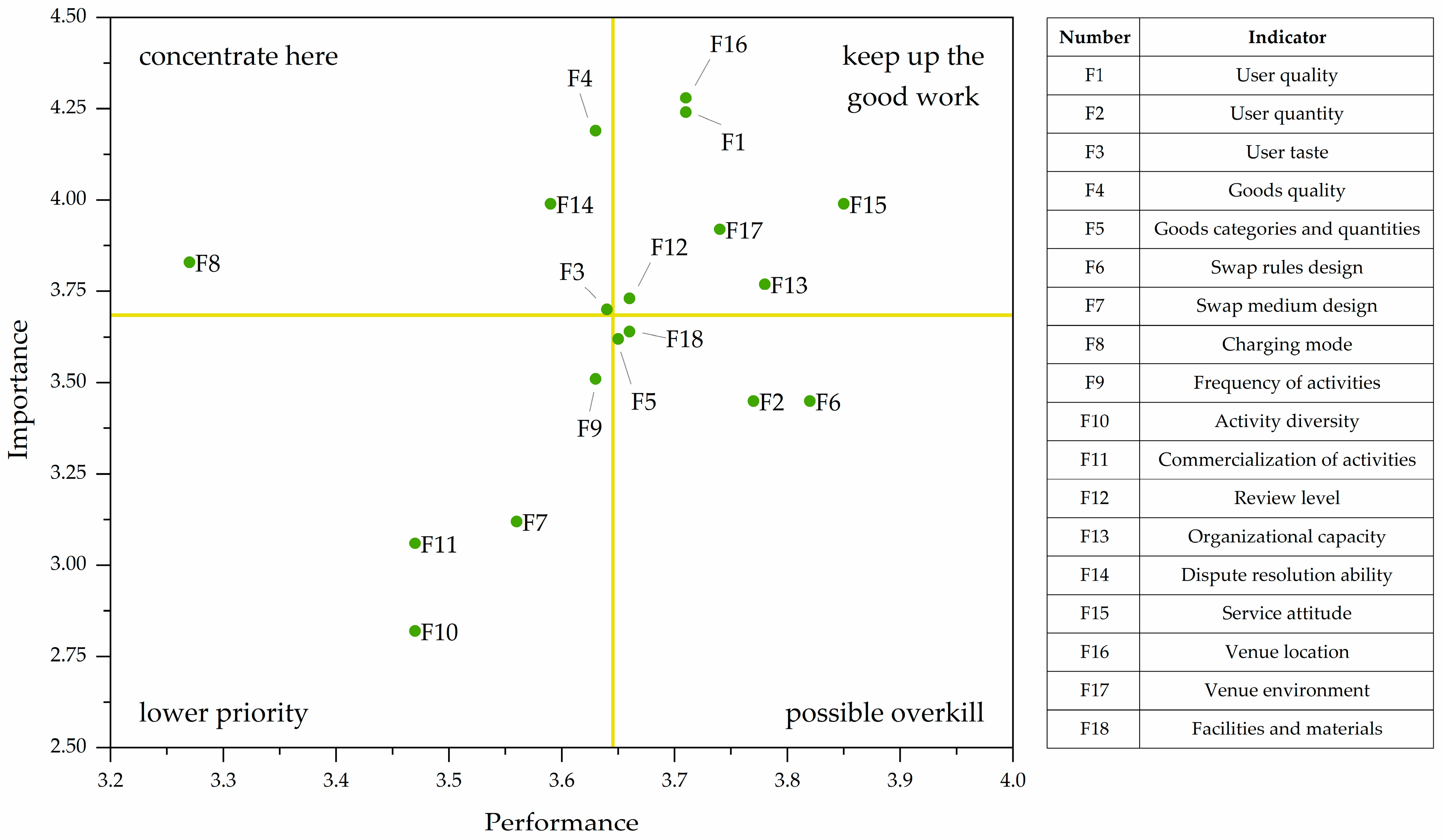

- (1)

- Construction of Quality Evaluation Indicator System by Grounded Theory Analysis

- (2)

- Development of Quality Assessment Model by IPA

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wahlen, S.; Laamanen, M. Collaborative consumption and sharing economies. In Routledge Handbook on Consumption; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 94–105. [Google Scholar]

- Botsman, R.; Rogers, R. What’s Mine Is Yours: The Rise of Collaborative Consumption; Harper Collins: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hamari, J.; Sjklint, M.; Ukkonen, A. The sharing economy: Why people participate in collaborative consumption. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2016, 67, 2047–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcneill, L.; Venter, B. Identity, self-concept and young women’s engagement with collaborative, sustainable fashion consumption models. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2019, 43, 368–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/zh/development-agenda/ (accessed on 21 October 2024).

- Henninger, C.E.; Bürklin, N.; Niinimki, K. The clothes swapping phenomenon—When consumers become suppliers. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2019, 23, 327–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, R.W.; Sherry, J.J.F.; Wallendorf, M. A Naturalistic Inquiry into Buyer and Seller Behavior at a Swap Meet. J. Consum. Res. 1988, 14, 449–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, D.; Hodges, N.N. Clothing Swaps: An Exploration of Consumer Clothing Exchange Behaviors. Fam. Consum. Sci. Res. J. 2016, 45, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.F.; Shih, H.C.; Yu, Z.; Pi, S.; Yang, H. A study on perceptual depreciation and product rarity for online exchange willingness of second-hand goods. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 241, 118315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guldenbrein, S. Convivial Clothing: Engagement with Decommodified Fashion in Portland, OR. Master’s Thesis, Portland State University, Portland, OR, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Henninger, C.E.; Brydges, T.; Iran, S.; Vladimirova, K. Collaborative fashion consumption—A synthesis and future research agenda. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 319, 128648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iran, S.; Geiger, S.M.; Schrader, U. Collaborative fashion consumption—A cross-cultural study between Tehran and Berlin. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 212, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, C.M.; Niinimki, K.; Lang, C.; Kujala, S. A Use-Oriented Clothing Economy? Preliminary Affirmation for Sustainable Clothing Consumption Alternatives. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 24, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, C.M.; Niinimaki, K.; Kujala, S.; Karell, E.; Lang, C. Sustainable product-service systems for clothing: Exploring consumer perceptions of consumption alternatives in Finland. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 97, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Almeida, A.R. Exploring Consumers’ Second-Hand Apparel Consumption Intention and Main Influential Factors. Master’s Thesis, Universidade do Porto, Porto, Portugal, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Song, K. A Study on the Determinants of Intention to Use Collaborative Consumption—Moderating Effect of Cooperative Local Governance. E-Bus. Stud. 2022, 23, 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, F.; Roby, H.; Dibb, S. Sustainable clothing: Challenges, barriers and interventions for encouraging more sustainable consumer behaviour. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2016, 40, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, C.; Joyner Armstrong, C.M. Collaborative consumption: The influence of fashion leadership, need for uniqueness, and materialism on female consumers’ adoption of clothing renting and swapping. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2018, 13, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, C.; Armstrong, C.M.; Liu, C. Creativity and sustainable apparel retail models: Does consumers’ tendency for creative choice counter-conformity matter in sustainability? Fash. Text. 2016, 3, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chunmin, L.; Joyner, A.C.M. Fashion leadership and intention toward clothing product-service retail models. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2018, 22, 571–587. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, S.; Lynes, J.; Young, S.B. Fashion interest as a driver for consumer textile waste management: Reuse, recycle or disposal. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2017, 41, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, C.; Zhang, R. Second-hand clothing acquisition: The motivations and barriers to clothing swaps for Chinese consumers. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2019, 18, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.L.; Woo, H.; Ramkumar, B. The role of product history in consumer response to online second-hand clothing retail service based on circular fashion. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 60, 102457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netter, S.; Pedersen, E.R.G. Motives of Sharing: Examining Participation in Fashion Reselling and Swapping Markets. In Sustainable Fashion: Consumer Awareness and Educatio; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 37–52. [Google Scholar]

- Mun, J. Online Collaborative Consumption: Exploring Meanings, Motivations, Costs, and Benefits. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Otero, J.C.; Pettersen, I.N.; Boks, C. Consumer engagement in the circular economy: Exploring clothes swapping in emerging economies from a social practice perspective. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 28, 279–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.L.; Jin, B.E. Why buy new when one can share? Exploring collaborative consumption motivations for consumer goods. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2020, 44, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albinsson, P.A.; Perera, B.Y. Alternative marketplaces in the 21st century: Building community through sharing events. J. Consum. Behav. 2012, 11, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuksel, C.U.; Kaya, C. Traces of cultural and personal values on sustainable consumption: An analysis of a small local swap event in Izmir, Turkey. J. Consum. Behav. 2020, 20, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echegaray, F.; Hansstein, F. Share a ride, rent a tool, swap used goods, change the world? Motivations to engage in collaborative consumption in Brazil. Local Environ. 2020, 25, 891–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poldner, K.; Overdiek, A.; Evangelista, A. Fashion-as-a-Service: Circular Business Model Innovation in Retail. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.T. A theory-driven evaluation perspective on mixed methods research. Res. Sch. 2006, 13, 75–83. [Google Scholar]

- Likert, R.; Likert Rensis, A.; Rensis, L. A Technique for the Measurements of Attitudes; Columbia University: New York, NY, USA, 1932. [Google Scholar]

- Neuman, W.L. Social Research Methods: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches; Allyn and Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Crocker, L.; Algina, J. Introduction to Classical and Modern Test Theory; Holt, Rinehart and Winston: Orlando, FL, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Hennink, M.M.; Kaiser, B.N.; Marconi, V.C. Code Saturation Versus Meaning Saturation: How Many Interviews Are Enough? Qual. Health Res. 2017, 27, 591–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taber, K.S. The Use of Cronbach’s Alpha When Developing and Reporting Research Instruments in Science Education. Res. Sci. Educ. 2017, 48, 1273–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B.; Strauss, A.; Strutzel, E. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Aldine Publishing Company: Chicago, IL, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Martilla, J.A.; James, J. Importance-Performance Analysis. J. Mark. 1977, 41, 77–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillemot, S.; Privat, H. The role of technology in collaborative consumer communities. J. Serv. Mark. 2019, 33, 837–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charnley, F.; Knecht, F.; Muenkel, H.; Pletosu, D.; Rickard, V.; Sambonet, C.; Schneider, M.; Zhang, C. Can Digital Technologies Increase Consumer Acceptance of Circular Business Models? The Case of Second Hand Fashion. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaska, E.; Werenowska, A.; Balińska, A. Environmentally and Socially Sustainable Behaviors of Generation Z in Poland Stimulated by Mobile Applications. Energies 2022, 15, 7904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domina, T.; Koch, K. Convenience and Frequency of Recycling: Implications for Including Textiles in Curbside Recycling Programs. Environ. Behav. 2002, 34, 216–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, M.D. Craft of Usership: A Qualitative Exploration of the Consumer’s Characteristics and Decision-Making Processes Leading to Extended Product Life. Ph.D. Thesis, Iowa State University, Ames, IA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, L.; Joergens, C. Ethical fashion: Myth or future trend? J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2006, 10, 360–371. [Google Scholar]

| Characteristics | Frequency, n | Percentage, % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 23 | 12.78 |

| Female | 157 | 87.22 | |

| Age (years) | Under 18 | 0 | 0 |

| 18–25 | 38 | 21.11 | |

| 26–30 | 54 | 30 | |

| 31–40 | 66 | 36.67 | |

| 41–50 | 13 | 7.22 | |

| Over 50 | 9 | 5 | |

| Education level | High school and below | 9 | 5 |

| Junior college | 28 | 15.56 | |

| Undergraduate | 120 | 66.67 | |

| Graduate and above | 23 | 12.78 | |

| Monthly income (RMB) | Below 5000 | 25 | 13.89 |

| 5000–10,000 | 76 | 42.22 | |

| 10,001–15,000 | 48 | 26.67 | |

| Above 15,000 | 31 | 17.22 | |

| Time of first participation in swap | 2021 and earlier | 50 | 27.78 |

| 2022 | 48 | 26.67 | |

| 2023 | 65 | 36.11 | |

| 2024 | 17 | 9.44 | |

| Channels for participating in swap | Swap market | 147 | 81.67 |

| Fixed swap space | 42 | 23.33 | |

| Online chat groups | 97 | 53.89 | |

| Second-hand trading apps | 133 | 73.89 | |

| Main Category | Subcategory | Concept | Concept Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Content factors | User characteristics | User quality | The overall quality of people participating in swaps on the platform |

| User quantity | The number of people participating in swaps on the platform | ||

| User taste | The aesthetics and preferences of people participating in swaps on the platform | ||

| Goods characteristics | Goods quality | The quality of goods circulated on the platform | |

| Goods categories and quantities | The categories and quantity of goods circulated on the platform | ||

| System factors | Rules and models | Swap rules design | The rationality of the rules to be followed during swapping set by the platform |

| Swap medium design | The usability of the intermediary objects for swap designed by the platform | ||

| Charging model | The methods and amounts of fees that the platform charges users | ||

| Activity planning | Frequency of activities | The frequency of swap activities organized by the platform | |

| Diversity of activity forms | The variety of different types of activities arranged by the platform during swap activities | ||

| Commercialization of activities | The involvement of merchants selling non idle goods during swap activities organized by the platform | ||

| Service factors | Organization and management | Review level | The level of review the platform conducts on goods offered by users for swap |

| Organizational capacity | The platform’s ability to organize swap activities | ||

| Dispute resolution ability | The platform’s ability to mediate disputes between users | ||

| Service attitude | The attitude of platform staff towards users | ||

| Venue and materials | Venue location | The geographical conditions of the swap venue, such as distance and transportation convenience | |

| Venue environment | The environmental conditions of the swap venue, such as size, lighting, and whether it is indoor or outdoor | ||

| Facilities and materials | The condition of facilities and materials at the swap venue, such as tables, chairs, and banner stands |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; Li, H. Quality Evaluation and Optimization of Idle Goods Swap Platform Based on Grounded Theory and Importance–Performance Analysis. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9348. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16219348

Wang X, Wang Z, Li H. Quality Evaluation and Optimization of Idle Goods Swap Platform Based on Grounded Theory and Importance–Performance Analysis. Sustainability. 2024; 16(21):9348. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16219348

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Xiaoke, Zhaohui Wang, and Hengtao Li. 2024. "Quality Evaluation and Optimization of Idle Goods Swap Platform Based on Grounded Theory and Importance–Performance Analysis" Sustainability 16, no. 21: 9348. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16219348

APA StyleWang, X., Wang, Z., & Li, H. (2024). Quality Evaluation and Optimization of Idle Goods Swap Platform Based on Grounded Theory and Importance–Performance Analysis. Sustainability, 16(21), 9348. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16219348