Abstract

This study integrates the concept of green entrepreneurship into the entrepreneurship education system, and grasps the correct way to promote the green entrepreneurship intention of college students. The model of promoting college students’ green entrepreneurship intention with policy support is constructed to answer the following research questions: what is the internal mechanism of green entrepreneurship education in promoting green entrepreneurship intention of college students in Guangxi, and how does green entrepreneurship policy affect its internal mechanism? Through a questionnaire survey of 304 college students from major cities in Guangxi, China, this paper investigates how college green entrepreneurship education affects college students’ green entrepreneurship intention through the desirability and feasibility of green entrepreneurship and actively explores the regulatory role of the institutional environment. The results show that the desirability and feasibility of green entrepreneurship play a mediating role between green entrepreneurship education and the promotion of college students’ green entrepreneurship intention, and the regulatory environment positively moderates the positive effect of desirability and feasibility of green entrepreneurship on green entrepreneurship intention. This study contributes to the literature on green entrepreneurship. On the one hand, by studying the mediating mechanism of green entrepreneurship desirability and feasibility, this study has added empirical evidence on the promotion effect of green entrepreneurship education on the green entrepreneurship intention of college students. On the other hand, this study emphasizes the impact of policy regulation on the strengthening process of college students’ green entrepreneurial intention. This study will help to build a characteristic and effective green entrepreneurship education system in colleges and universities, enhance college students’ green entrepreneurship intention and green core competitiveness, and drive them to enhance their sense of social responsibility and build “green development” values.

1. Introduction

The convergence of economic growth and environmental protection is often challenging, impeding the sustainable development of society [1,2]. Green entrepreneurship is recognized as a viable approach to advancing sustainable development and fostering innovation within society, offering a means to address economic, social, and environmental issues [3,4]. The concept of green entrepreneurship emerged in response to the urgent need for environmentally sustainable practices in business [5]. It has evolved from traditional entrepreneurship, but with a strong emphasis on environmental responsibility, social impact, and economic viability. Green entrepreneurs are individuals or organizations that identify opportunities to create environmentally friendly products, services, or processes while considering their ecological and social implications [6,7]. The convergence of entrepreneurship and ethics is particularly evident in green entrepreneurship [8]. At the individual level, scholars have found that personal traits, age, education, and cultural identity can significantly influence tendencies toward green entrepreneurship [9,10,11,12]. In addition, preserving cultural identity and promoting cultural industries can equally serve as motivations and goals for green entrepreneurship [7,13,14]. Some scholars have also proposed from a green management and strategy perspective that SMEs create competitive advantages by developing green business strategies [15,16] and adopting green management practices [17], which, in turn, enhances the firm’s green economic benefits. As the tension between economic development and environmental protection intensifies, green entrepreneurship is gaining traction globally [18], representing not only a means of achieving profits through green competitiveness but also reflecting a commitment to environmental and social responsibility. Consequently, it is increasingly becoming a focal point and primary area of research in entrepreneurship.

College students are important participants in green entrepreneurship and the main force for building an innovative society in the future. According to the Ministry of Education, PRC, there are expected to be 11.79 million college graduates in China in 2024, and in terms of the number of college graduates, more than 300,000 will join the ranks of start-up businesses in 2024. According to the “2022 College students Micro-entrepreneurship Action Project Analysis Report” released by China Youth Daily, college students tend to take the initiative to align with national strategies and tasks and attach great importance to the impact of college entrepreneurship education and support for entrepreneurial practice. Chinese college students have shown a strong interest and innovative spirit in the field of green entrepreneurship. Many cases show that college students not only pay attention to green development, but also promote pollution and carbon reduction through entrepreneurial projects, and most of these projects are co-created by college students or teachers and students. This embodies the application of scientific research accumulation and scientific and technological innovation in universities. Therefore, mobilizing college students’ green innovation thinking and awareness to cultivate green core competitiveness is essential for promoting the overall construction of a green society [19]. Universities serve as ideal platforms for connecting individuals with entrepreneurial experience to those with entrepreneurial intentions [20]. The studies conducted by Yi et al. [21] and Amankwah et al. [22] both indicate that there is a direct positive relationship between green entrepreneurial intention (GEI) and green entrepreneurial behavior. In other words, the intention of college students to engage in green entrepreneurship can translate into actual green entrepreneurial actions. Therefore, enhancing the entrepreneurial intention of college students has also become the focus of scholars’ research in recent years [23]. Factors such as risk propensity, self-efficacy, social networks, government support, educational support, and cultural values have been shown to influence the entrepreneurial intention of university students [24,25,26]. Most studies conducted in the past have indicated that university entrepreneurship education has a positive impact on the entrepreneurial intentions of university students [27]. This positive effect has also been confirmed in the field of green entrepreneurship [21,25].

Based on the entrepreneurial event model [28,29], individual satisfaction with anticipated green entrepreneurial opportunities and the willingness to take action toward green entrepreneurship can enhance GEI. University entrepreneurship education provides knowledge and support for students’ entrepreneurship [27,30]. The educational support provided by universities can be categorized into two types: cognitive-emotional support, which aims to articulate the cultural values of entrepreneurship, and informational-tool support, which aims to provide information, resources, and material help for the realization of entrepreneurial intentions [31]. Green entrepreneurship education (GEE) can provide university students with cognitive–affective support to improve their green entrepreneurial desirability (GED) and informational-tool support to improve their green entrepreneurial feasibility (GEF). Therefore, GED and GEF were chosen in this study to mediate the relationship between GEE and GEIs. The purpose of conducting green entrepreneurship education is to create and foster an attitude of support for green entrepreneurship among students and to provide them with the entrepreneurial knowledge to view entrepreneurship as a viable career option [32]. Although many studies and actual data show that the proportion of college students with entrepreneurial intention is not very high after graduation, the entrepreneurial intention of college students is the main predictor of their entrepreneurial behavior [33]. Improving entrepreneurial intention will help college students to make a key transition from entrepreneurial decision making to entrepreneurial behavior, marking the transition from individual identity to entrepreneurial identity [34], which will have a positive impact on their entrepreneurial career for a long time in the future.

China has integrated green practices into its economic system to pursue a path of sustainable development. In order to promote the growth of green entrepreneurship, the country has implemented various policies nationwide. Located in southwest China, Guangxi is the only ethnic minority autonomous region in China that is located near the sea. It serves as an important gateway for China to ASEAN. China’s Guangxi Zhuang autonomous region will have more than 430,000 college graduates in 2024, and more than 10,000 will become freelancers and entrepreneurs. From the perspective of entrepreneurship education, the higher education institutions in Nanning, Guilin, and Liuzhou in the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region represent the highest level of higher education in Guangxi, and entrepreneurship education is carried out the most in these cities. In terms of natural conditions, Guangxi is endowed with good green entrepreneurial resources, such as unique geological conditions, rich biodiversity, water resources, hydropower resources, etc. From the perspective of the economic environment of green entrepreneurship, the industrial development of Guangxi is far behind that of the central and eastern provinces of China. The employment opportunities of college graduates and the local industries need to be further developed, so some students who want to develop locally in Guangxi and have the willingness and ability to carry out green entrepreneurship will be stimulated to try green entrepreneurship. Focusing on cultivating the green entrepreneurship intention and ability of Guangxi college students can not only promote the sustainable development of Guangxi itself, but also provide theoretical and practical reference for green entrepreneurship education in other regions.

Based on the entrepreneurial event model and the theory of planned behavior, this study tries to explore the enhancement of college students’ GEI against the background of green development and to find the mediating effect of GED and GEF in which the green entrepreneurial concept is integrated into the entrepreneurial education system of college students by establishing a model with policy support. This study will provide useful insights and guidance for GEE in colleges and universities in theory and practice. This study aims to investigate the enhancement of college students’ GEI in the context of sustainable development, identifying the mediating effects of GED and GEF by integrating the concept of green entrepreneurship into the entrepreneurial education system for college students. This will be achieved by establishing a model with policy support, providing valuable insights and guidance for GEE in colleges and universities, both in theory and practice.

2. Literature Review and Research Hypothesis

2.1. Green Entrepreneurship Education and Green Entrepreneurial Intentions

Education is a social activity to cultivate human beings, and GEE is an educational program focused on promoting environmental conservation and sustainable economic progress. Green entrepreneurial intention refers to the willingness of individuals to engage in entrepreneurial behavior oriented to environmental protection and sustainable economic development. According to the analysis of motivational behavior theory, the connotation of green entrepreneurial intention includes the value pursuit of an individual’s own green entrepreneurial behavior and the ability judgment of an individual to engage in green entrepreneurial behavior. Since entrepreneurship education aims to enhance the recipients cognitively and behaviorally, GEE is centered on fostering green innovation awareness and cultivating green entrepreneurial competence [35,36]. The concept of GEE is deeply rooted in people’s minds as it contributes to sustainable socio-economic development [37]. In modern higher education, particularly in traditional business education, GEE can play a crucial role in preparing aspiring green entrepreneurs for sustainable development [38]. The integration of entrepreneurship education and higher education positions universities as key drivers of sustainable economic growth and technological advancement [39,40]. GEE equips students with knowledge of sustainable development and entrepreneurial skills [41], while also enhancing their environmental consciousness. This accumulation of knowledge and attitudes contributes to enhancing the GEI of university students. Therefore, GEE has the potential to enhance college students’ GEI. To ensure the rigor of our hypothesis, we introduced and designed the incorporated competing hypotheses, which led to the formulation of Hypothesis H1a and Hypothesis H1b.

H1a.

GEE will positively affect GEI.

H1b.

GEE will not affect GEI.

2.2. The Mediating Role of Green Entrepreneurial Feasibility and Desirability

The entrepreneurial event model [28,29] emphasizes the significance of entrepreneurial feasibility and desirability in the entrepreneurial process. Green entrepreneurial feasibility refers to the operability of an individual to engage in green entrepreneurship, which reflects whether an individual perceives themself to have the ability to carry out green entrepreneurship smoothly. Green entrepreneurship desirability refers to the satisfaction degree of an individual with the expected prospect of green entrepreneurship, which reflects whether the result of an individual’s green entrepreneurial behavior is in line with their own value pursuit. Under the GEE system, universities offer scientific entrepreneurship courses that cover topics such as company creation, corporate tax treatment, employee recruitment and training, and more. Furthermore, they provide a range of extracurricular activities, including business plan competitions, business mentoring, entrepreneurship-related club activities, and business incubation bases [30]. Notably, support for green entrepreneurship is also extended, encompassing entrepreneurship courses for rural revitalization, green entrepreneurship plan competitions, and additional financial backing for environmentally friendly business incubation, among other initiatives. These educational components equip students with the necessary knowledge and skills for entrepreneurship and even offer a certain amount of start-up capital for green entrepreneurship. Through GEE, the sharing and learning of entrepreneurial knowledge among college students can inspire confidence in their own entrepreneurial abilities, improve college students’ perception of the feasibility of green entrepreneurship, and enhance their attitudes toward entrepreneurship [39]. In addition, GEE provides college students with a valuable blueprint for becoming entrepreneurs. Compared to working for others, becoming a green entrepreneur not only offers higher income and greater autonomy, but also allows individuals to make a greater contribution to society and achieve a stronger sense of self-worth. This aligns more closely with college students’ future expectations, ultimately improving their GED.

Self-efficacy theory states that individuals with a high level of confidence in their abilities to accomplish tasks in a specific domain are more proactive in approaching tasks and working within that domain [42]. In the field of green entrepreneurship, an individual’s self-efficacy is reflected in their perceived GEF [43]. Previous studies have indicated a positive correlation between GEF and GEI [44,45,46,47]. When college students perceive green entrepreneurship as highly feasible, their belief in possessing the necessary knowledge, skills, and resources to successfully implement green projects increases, which in turn enhances their self-efficacy. This boost in confidence encourages them to approach the challenges of green entrepreneurship with greater enthusiasm, resulting in a stronger entrepreneurial intention. This is because individuals are more inclined to invest effort in activities they believe they can excel at.

Furthermore, existing research has demonstrated that perceived desirability among entrepreneurs has a positive and significant influence on entrepreneurial intentions [46,47,48]. This is because individuals are more willing to become entrepreneurs when they perceive that entrepreneurship aligns more with their expectations than working for others. The desire to become an entrepreneur serves as a positive motivation for individuals aspiring to start their own businesses. Therefore, the more aware college students are of the future prospects of green entrepreneurship, the more interested they become in engaging in it.

According to the theory of planned behavior, external factors indirectly impact intentions through individuals’ personal contextual perceptions of the feasibility and desirability of entrepreneurship [29]. Research has demonstrated that perceived entrepreneurial feasibility and desirability are key determinants of entrepreneurial intentions [48]. Furthermore, the perception of GEF and GED is influenced by the exogenous factor of GEE [49]. Therefore, by receiving GEE, college students’ perception of the skills necessary for green entrepreneurship is developed, while at the same time, their self-confidence in the success of green entrepreneurship as a behavior is strengthened, leading to an enhancement in the perceived feasibility of green entrepreneurship. This, in turn, stimulates the desire to engage in green entrepreneurship, resulting in an increase in the intention to pursue green entrepreneurship. Furthermore, by incorporating green entrepreneurship education, university students may develop elevated aspirations for the advancement of environmentally conscious entrepreneurial practices. This heightened perception of GED subsequently bolsters the intention to engage in such behavior.

H2.

GEE will indirectly influence GEI through GEF, with GEF acting as a mediator.

H3.

GEE will indirectly influence GEI through GED, with GED acting as a mediator.

2.3. The Moderating Role of the Regulatory Environment

Institutions play a significant role in influencing the identification, development, and utilization of innovation and entrepreneurship opportunities [50]. The regulatory environment (RE) of a country or region is composed of various types of local rules and conditions and consists of three dimensions: regulatory, normative, and cognitive [51]. Regulatory elements refer to government regulations and legal policies that either enable or restrict specific entrepreneurial behaviors [52]. The RE of entrepreneurship has been found to be an important factor influencing entrepreneurial behavior [53]. Different legal policy regimes and social rules can lead to varying entrepreneurial outcomes, and scholars generally agree that the RE of different regions are significant factors contributing to differences in entrepreneurial behavior [54,55]. In institutional theory, organizations are required to follow and implement the rules and requirements in the RE in order to gain support and legitimacy status [56].

In institutional theory, the rules and requirements in the RE are what organizations must follow and implement in order to gain support and legitimacy status [57]. The RE significantly influences individuals’ social cognitive traits or alleviates the relationship between individual cognitive traits and their proximal decision-making behaviors. In countries with a robust legal system, entrepreneurs have a stronger inclination towards green entrepreneurship [58]. At the same time, previous studies have shown that the RE has more of a moderating effect on entrepreneurial activity [57,59]. Thus, there is a fundamental underlying hypothesis that green entrepreneurial behavior is influenced by the specific institutional arrangements in the region. Within a favorable RE, despite the challenges green entrepreneurship faces in terms of resource acquisition and technological mastery, positive factors such as policy incentives, financial support, and broad social acceptance can greatly enhance college students’ confidence and willingness to pursue green entrepreneurship, encouraging them to tackle challenges and join the green entrepreneurial wave. Additionally, such an environment fosters positive public opinion and societal recognition, significantly boosting students’ perception of the long-term value and social importance of green entrepreneurship, thereby increasing their entrepreneurial intent. Conversely, in an unfavorable RE, even if students hold some interest or value recognition towards green entrepreneurship, the lack of social endorsement and support may dampen their willingness to engage in it.

While in some contexts, the RE may negatively affect entrepreneurial intentions or activities due to overly strict regulations or inappropriate policy implementations, this study focuses on the specific domain of green entrepreneurship. The intrinsic environmental benefits and social value associated with green entrepreneurship make it more likely to receive support from both the government and society, which reduces the probability of negative impacts.

H4.

RE will positively moderate the positive correlation among GED, GEF, and GEI.

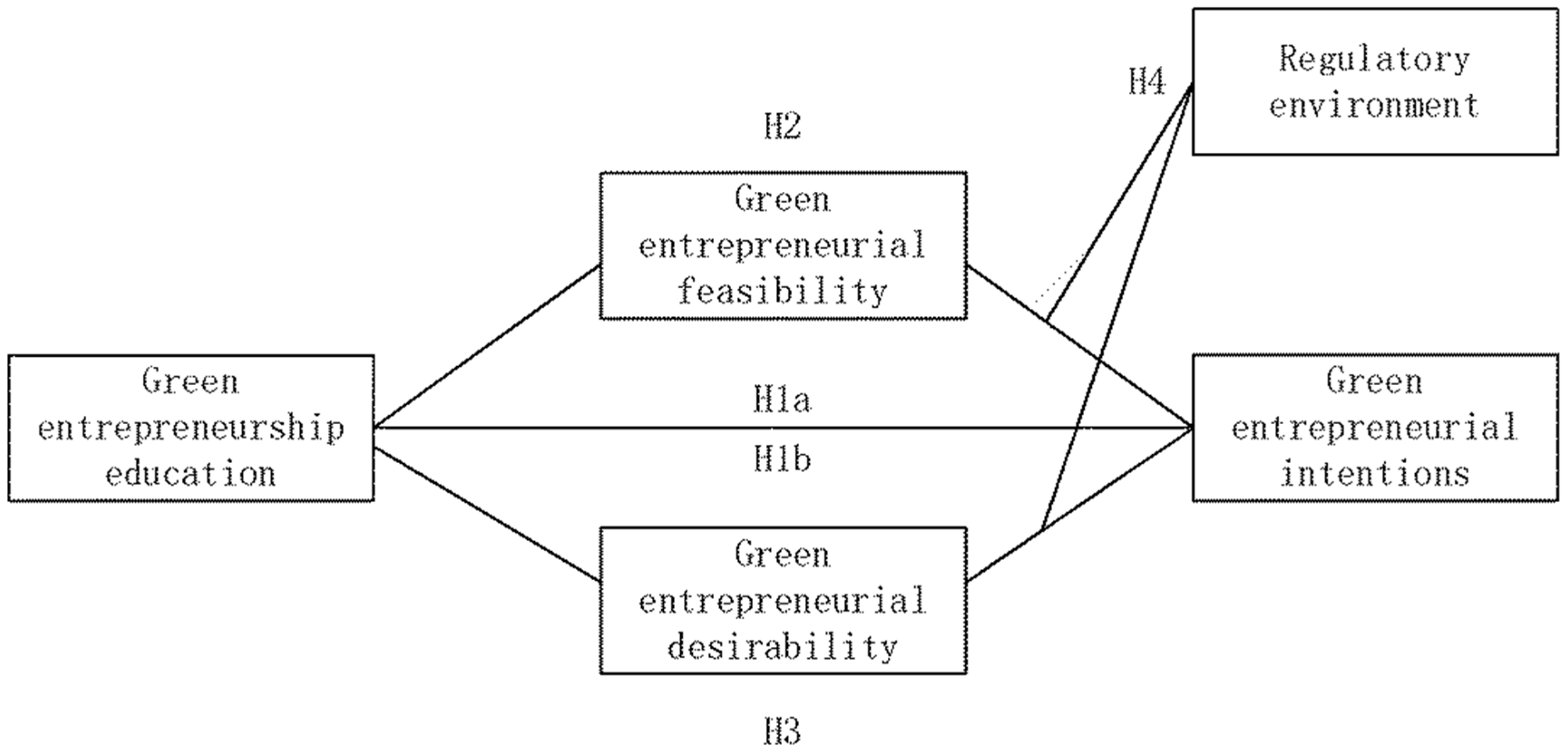

The relationships between all hypothesis and variables are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Theoretical model.

3. Variable Design and Sample Selection

3.1. Variable Design

The questionnaire consisted of six segments: demographic information, GEE, GEF, GED, RE, and GEI. All the scales except demographic information are based on a 5-point Likert scale from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”, as indicated by the numbers “1” to “5”. Control variables, including gender, education, and familial entrepreneurial experience, were incorporated within the demographic information section.

The GEE variable refers to Yi et al. [21] and consists of four possible options: “My university offers green entrepreneurship courses”; “My university encourages students to start green businesses”; “My university provides students with the financial and policy tools for entrepreneurship”; and the reverse option, “My university does not pay attention to the impact of students’ entrepreneurial projects on the natural environment and social sustainability”, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.850.

The RE variable is derived from Banerjee’s [56] study, which examines the degree of local government support for green entrepreneurship and the degree of regulation of corporate environmental responsibility. Positive answers include the following: “Local government introduces policies and regulations and monitors their implementation to protect the legal rights of green entrepreneurs” and “Local policy environment provides incentives (e.g., subsidies, grants, tax exemptions, etc.) for firms’ environmental protection programs and behaviors”, as well as “The local government regulates or penalizes enterprises with serious pollution” and the reverse question “Local enterprises do not have to consider the impact of their business activities on the natural and social environments”. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.849.

The measures of GED and GEF are derived from Hattab’s [60] study, which “greened” the traditional measures of entrepreneurial desirability and entrepreneurial feasibility. In particular, GED consists of positive responses such as “Creating my own green start-up is something that appeals to me”, “I would love to start my own business”, “If I were to start a green business, I would be I would be passionate about it”, and the reverse, “I am nervous and scared about starting a green business” with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.869. The feasibility of starting a green business consisted of the positive response “Green business is feasible for me” and the negative option “Green business is not feasible for me”. Furthermore, there are options such as “Entrepreneurship is feasible for me”, “If I start a green business on my own, I am sure that I will be successful”, “I have enough knowledge to support me to start a green business”, and the reverse option, “Green business is very challenging for me” and “Entrepreneurship is very challenging and almost unattainable for me”, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.868.

The GEI variable was measured by Huggins and Thompson [61], which consisted of the following five choices: “I intend to start a green, sustainable company in the future”, “I have taken the time to learn how to start a green company”, and “I have considered my own green entrepreneurial program”, and another five reverse options, including, “I have never sought out green entrepreneurial opportunities”, “I have never read about green entrepreneurship”, and “I have considered my own green entrepreneurship program”. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.886.

3.2. Sample Selection

It is important to note that colleges and universities in the Guangxi region, including Nanning, Liuzhou, and Guilin, have introduced courses on GEE. Subsequently, a questionnaire survey was conducted among university students in Guangxi. From 10 September 2023 to 10 October, we took field visits to colleges and universities in Guilin and Nanning, and obtained survey data from 80 questionnaires with the other questionnaires made available online. On 30 October 2023, we completed the data collection work. A total of 363 questionnaires were sent out, and 332 were returned. Out of these, 304 questionnaires were deemed valid. Among the 304 questionnaires, there were 142 males and 162 females. Additionally, there were 40 postgraduates, 135 undergraduates, and 129 people with the rest of the academic qualifications. Out of the total respondents, 120 reported having family members with entrepreneurial experience, while 184 had no entrepreneurial experience, as described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics.

4. Results

4.1. Common Method Variance (CMV)

Validated factor analysis was conducted using AMO24.0 for green entrepreneurship education (GEE), green entrepreneurial feasibility (GEF), green entrepreneurial desirability (GED), regulatory environment (RE), and green entrepreneurial intention (GEI). The results are shown in Table 2, where the five-factor model has the best fit compared to the other models (χ2/df < 3; RMSEAA < 0.08; CFI > 0.8; IFI > 0.9; TLI > 0.9; PGFI > 0.5); therefore, the discriminant validity of the five variables in the research model is considered good.

Table 2.

Validation factor analysis.

Since all scales were filled out by college students, in order to test the common method bias test, this study was conducted using the Harman one-way test. A total of five factors were extracted with unrotated factor eigenvalues greater than 1. The cumulative explained variance was 70.220%, which is higher than 50%. Among them, the maximum factor loading was 35.699%, which did not exceed the critical value of 40%. In summary, there is no common method bias in this study, i.e., there is no situation where a single factor explains all of the variance.

4.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis

Validity analysis conducted using SPSS 26.0 software reveals that the KMO sampling adequacy measure is 0.904, with p = 0.000 < 0.001. Additionally, all factor loading coefficients are greater than 0.7, AVE values are greater than 0.5, and CR values are greater than 0.65. These results indicate that the questionnaire has good validity (refer to Table 3).

Table 3.

Convergent validity.

4.3. Correlation Analysis

This study was analyzed using SPSS 26.0 software. As shown in Table 4, the relationship between the variables was analyzed using the Pearson correlation coefficient. The five primary variables included in the research model all exceed the average value, with the mean central tendency ranging from 3.298 to 3.407. The majority of respondents hold a positive attitude toward green entrepreneurship. The standard deviation is confined to a range of 0.865 to 0.960, which is below the threshold of 1.000. Additionally, the results of the correlation studies affirm that all variables are positively and significantly correlated. Thus, these results support the adoption of the proposed multiple mediation–moderation research model. As shown in the table, gender, education level, and family entrepreneurial experience as control variables have no significant correlation with green entrepreneurial intention. It indicates that the above variables do not significantly affect green entrepreneurship education and intention.

Table 4.

Mean, standard deviation, and correlation coefficient of variables.

To evaluate the multicollinearity in the sample data, we employed the SPSS26.0 analysis software for diagnosis. According to prevailing research, a VIF (Variance Inflation Factor) below 5 suggests low autocorrelation among the selected sample questionnaire data and insignificant multicollinearity. As shown in Table 5, the VIF for each dimension of the main variables is below the accepted threshold of 5. This indicates that the sample questionnaire data in this study do not exhibit autocorrelation issues or significant multicollinearity, thereby meeting the requirements of the research.

Table 5.

Multicollinearity.

4.4. Hypothesis Testing

Using SPSS26.0 as a research tool, we tested the hypotheses using hierarchical regression. The tests of mediating and moderating roles were analyzed with reference to the study conducted by MacKinnon et al. From Table 6, it can be seen that the standardized path coefficient value for the impact of GEE on GED is 0.393 > 0. This path is significant at the 0.01 level (z = 7.443, p = 0.000 < 0.01), indicating a significant positive impact relationship between GEE and GED. The standardized path coefficient value of GEE for GEF is 0.319 > 0, and this path shows a 0.01 level of significance (z = 5.864, p = 0.000 < 0.01), thus indicating that GEE will have a significant positive impact on GEF. The standardized path coefficient value is 0.197 > 0 when GEE has an effect on GEI, and this path shows significance at the 0.01 level (z = 3.976, p = 0.000 < 0.01), thus suggesting that GEE will have a significant positive influence on GEI. The standardized path coefficient value for GED for GEI is 0.342 > 0 and this path shows significance at the 0.01 level (z = 7.244, p = 0.000 < 0.01), thus suggesting that GED will have a significant positive impact relationship on GEI. The standardized path coefficient value for GEF for GEI is 0.374 > 0 and this path shows significance at the 0.01 level (z = 8.154, p = 0.000 < 0.01), thus suggesting that GEF will have a significant positive impact relationship on GEI.

Table 6.

Model regression coefficient.

The mediating effects of green entrepreneurship desirability and feasibility were verified according to Baron and Kenny’s causal step test, after adding three control variables, namely, gender, level of education, and whether or not a family member has entrepreneurial experience. Table 6 includes a total of four regression models for GEE and GEI, GEE and GED, GEE and GEF, and GEE, GED, GEF, and GEI, which all include control variables. As shown in Table 7, GEE has a significant positive effect on GEI (adjusted R2 of 0.185, B-value of 0.419, p < 0.01), GEF (adjusted R2 of 0.09, B-value of 0.324, p < 0.01), and GED (adjusted R2 of 0.161, B-value of 0.0.351, p < 0.01) all had significant positive effects. GEF mediated a significant effect between GEE and GEI, and GED also mediated a significant effect between GEE and GEI (adjusted R2 of 0.466, B-value of 0.188, 0.340, and 0.343, respectively, p < 0.01).

Table 7.

Regression model test in mediating effect.

Using the percentile Bootstrap method, the mediating role was tested and the results are presented in Table 8. Both GEF and GED play a partially mediating role between GEE and GEI.

Table 8.

Summary of mediating effect test results.

When analyzing the moderating effect of the RE, as shown in Table 9, the moderating effect is divided into six models, including GED in Model 1, and three control variables such as gender, level of education, and whether or not your family members have entrepreneurial experience; Model 3 adds the RE on the basis of Model 1, and Model 5 adds the interaction term on the basis of Model 2. For Model 1, it can be seen that GED shows significance (t = 11.742, p = 0.000 < 0.05) without considering the interference of the moderating variable RE. It means that GED will have a significant impact relationship on GEI. The interaction term between GED and RE shows significance (t = 6.271, p = 0.000 < 0.05), which means that when GED affects GEI, the magnitude of the effect of the moderating variable (RE) is significantly different at different levels, i.e., there is a moderating effect. Similarly, Models 2, 4, and 6 analyze the moderating effect of RE between GEF and GEI. The purpose of Model 2 is to investigate the effect of GEF on the dependent variable GEI when the interference of the moderating variable RE is not considered. As presented in Table 9, GEF shows significance (t = 11.947, p = 0.000 < 0.05), implying that GEF will have a significant impact relationship on GEI. The data in Model 6 show that the interaction term between GEF and RE presents significance (t = 5.184, p = 0.000 < 0.05), implying that the moderating variable RE has a significant difference in the magnitude of the effect when the GEF influences GEI.

Table 9.

Moderating effect model.

According to the empirical test results, it can be concluded that (1) GEE has a positive effect on GEI, GEF, and GED; GEF and GED are capable of positively influencing GEI; GEF and GED play a mediating role between GEE and GEI; and H1a, H2, and H3 verification is established. (2) In the empirical test results of the model that GEE positively affects GEI through the mediating variables of GED and GEF, it is found that the RE positively regulates GEF and GED, which ultimately affects GEI; thus, it indicates that the RE can positively moderate the positive relationship between GED and GEI and between GEF and GEI. H4 is valid.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

Numerous academic studies have been conducted in the past on entrepreneurship education and the entrepreneurial intentions of college students, as both students and higher education institutions play a crucial role in entrepreneurship [47,62,63]. The emergence of green entrepreneurship as a concept has added vitality to the field of entrepreneurship and sparked a new round of discussion [49]. This study builds upon previous research by examining the relationship between (GEE and college students’ GEI). It also introduces the RE variable to explore the factors influencing green entrepreneurship at the government, school, and student levels. This study focuses on the university environment in Guangxi and investigates the connection between GEE and college students’ GEI. It constructs a theoretical model of mediation and regulation and successfully validates four hypotheses.

First, the study confirms that GEE effectively increases college students’ GEI, aligning with the previous literature [47,49]. GEE improves students’ perceptions of the feasibility of green entrepreneurship programs and increases their confidence in pursuing green entrepreneurship opportunities. Additionally, GEE strengthened students’ interest and motivation to pursue green entrepreneurship and enhanced their positive attitudes toward this field.

Second, GED mediated between GEE and GEI. This implies that education not only directly influences students’ intentions but also indirectly influences their intentions by enhancing their perceptions and attitudes toward green entrepreneurship. This finding aligns with the significant role of education in the entrepreneurial process [35,38], which extends beyond the mere transmission of knowledge and has the potential to shape students’ attitudes and beliefs.

Third, GEF mediates between GEE and GEI. Higher education is able to leverage students’ core competencies in creativity, knowledge, and technology by developing their diverse skills [64]. Based on the theory of the entrepreneurial program model [28,29], the acquisition of entrepreneurial knowledge and skills by college students through GEE is a necessary prerequisite for their entrepreneurial activities [27] and for the development of college students’ GEIs.

Finally, RE plays a positive moderating role. Entrepreneurship is essentially a regulatory environment [51,65], and the environmental conditions for green entrepreneurship become more favorable as the intensity of the RE increases, and as policies and laws encourage green sustainability and penalize environmentally destructive economic behavior.

To sum up, on the one hand, this study confirms the mediating mechanism of green entrepreneurship desirability and feasibility, increases the empirical evidence of the promoting effect of green entrepreneurship education on green entrepreneurship intention of college students, puts forward the corresponding theoretical model, expands the boundary of green entrepreneurship research field, and provides more theoretical paths for follow-up research. On the other hand, it enriches the existing research results of entrepreneurial education in the context of sustainable development, extends the theoretical research of entrepreneurial education, and increases the explanatory power of the theoretical system of entrepreneurial education.

5.2. Practical Implications

The outcomes of this investigation carry significant implications for higher education institutions and policymakers in the region of Guangxi. One potential avenue for advancement involves the expansion of practical opportunities and the fostering of industry collaboration to enhance students’ practical skills and confidence in GEE. By promoting the teaching of green entrepreneurship, colleges and universities contribute to the social benefits and value associated with this field, thereby encouraging college students to engage in green entrepreneurship. It is essential to explore successful examples of green entrepreneurship to promote sustainable green development, aligning with societal demands and realizing social value, thereby providing high-quality nourishment for GEE. Additionally, shaping the expectations of college students regarding green entrepreneurship and instilling green entrepreneurial values in entrepreneurship education is crucial to enable the target audience of GEE to better understand and embrace its value propositions. Incorporating green entrepreneurial values into entrepreneurship education can effectively strengthen college students’ motivation toward green entrepreneurship. Furthermore, colleges and universities need to thoroughly analyze and reevaluate the approach to teaching green entrepreneurship in higher education, considering students’ characteristics, understanding, and proficiency in current and future entrepreneurial resources. This should involve developing personalized green entrepreneurial plans that are logically feasible and supported by scientific evidence to enhance the practicality and feasibility of green entrepreneurship, thereby increasing students’ willingness to engage in green entrepreneurial activities.

On the other hand, governments have the potential to advance sustainable development and foster innovation through the implementation of policies that support environmentally conscious entrepreneurship and provide increased assistance to students. When introducing GEE, it is essential to educate students about the regulatory environment in which they will operate their businesses and the fundamental principles of green entrepreneurship within that specific context. Moreover, it is critical to ensure that students have a comprehensive understanding of the RE for green entrepreneurship within their own living environment. Familiarity with the regulatory environment reinforces students’ commitment to green entrepreneurship, enhances the viability of environmentally conscious business ventures, and encourages the development and strengthening of GEI.

5.3. Research Shortcomings and Recommendations

This study has several limitations. Firstly, the timeframe of the study is restricted. Given that GEE is a gradual process in practice, the findings of this study are only applicable to the short-term analysis of the relationship between the regulatory environment, GEE, and green entrepreneurial intention. It is necessary to further investigate whether these variables play the same intermediary and moderating roles in the long term. Secondly, the study samples were exclusively drawn from university students in various cities in Guangxi, limiting the scope of the research. It is imperative to broaden the geographical scope of the sample and involve a more diverse group of university students in future research to assess the generalizability of the study’s conclusions to a wider range of GEE. This expansion will contribute to the enhancement of theoretical research, refinement of the current model, and improvement of its applicability in both theoretical and practical contexts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.Y.; software, S.Y.; formal analysis, C.Y.; investigation, C.Y.; resources, C.Y. and X.Z.; data curation, S.Y.; writing—original draft, C.Y.; writing—review & editing, C.Y. and X.Z.; supervision, S.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Pearl River-Xijiang River Economic Belt Development Research Institute Scientific Research Grants for the Key Research Bases of Humanities and Social Sciences of Guangxi Colleges and Universities, grant number [ZX2023050]. This research was also funded by Research Project on the Theory and Practice of Ideological and Political Education of College Students in Guangxi (College Counselors’ Work), grant number [2020LSZ085].

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research has passed the ethical review of the Human Ethics Committee of Guangxi Normal University, and the ethical review number is 202410190.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Carree, M.A.; Thurik, A.R. The Impact of Entrepreneurship on Economic Growth. In Handbook of Entrepreneurship Research: An Interdisciplinary Survey and Introduction; Acs, Z.J., Audretsch, D.B., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Bell, R. Behavioural entrepreneurial mindset: How entrepreneurial education activity impacts entrepreneurial intention and behaviour. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2022, 20, 100639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusu, V.D.; Roman, A. Entrepreneurial Activity in the EU: An Empirical Evaluation of Its Determinants. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, T.J.; McMullen, J.S. Toward a theory of sustainable entrepreneurship: Reducing environmental degradation through entrepreneurial action. J. Bus. Ventur. 2007, 22, 50–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaak, R. The Making of the Ecopreneur. Greener Manag. Int. 2002, 38, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patzelt, H.; Shepherd, D.A. Recognizing Opportunities for Sustainable Development. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2011, 35, 631–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, K.; Gibbs, D. Rethinking green entrepreneurship—Fluid narratives of the green economy. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2016, 48, 1727–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiose, D.; Keen, S. Understanding the Relationships between Environmental and Social Risk Factors and Financial Performance of Global Infrastructure Projects. iBusiness 2017, 9, 80–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hoogendoorn, B.; van der Zwan, P.; Thurik, R. Sustainable Entrepreneurship: The Role of Perceived Barriers and Risk. J. Bus. Ethic. 2019, 157, 1133–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kummitha, H.R.; Kummitha, R.K.R. Sustainable entrepreneurship training: A study of motivational factors. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2021, 19, 100449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baber, H.; Fanea-Ivanovici, M.; Sarango-Lalangui, P. The influence of sustainability education on students’ entrepreneurial intentions. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2023, 25, 390–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misztal, A.; Kowalska, M. Factors of green entrepreneurship in selected emerging markets in the European Union. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 25, 13819–13836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiVito, L.; Bohnsack, R. Entrepreneurial orientation and its effect on sustainability decision tradeoffs: The case of sustainable fashion firms. J. Bus. Ventur. 2017, 32, 569–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lin, Y.; Lai, Y. The determinants of green entrepreneurship: The perspectives of leadership, culture, and creativity. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2022, 32, 3432–3444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, S.; Singh, S.; Gupta, H. Green entrepreneurship and digitalization enabling the circular economy through sustainable waste management—An exploratory study of emerging economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 422, 138433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Niu, Q. Enhancing green radical product innovation through sustainable entrepreneurship orientation and sustainable market orientation for sustainable performance: Managerial implications from sports goods manufacturing enterprises of China. Econ. Res. Istraz. 2022, 36, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhloufi, L.; Zhou, J.; Siddik, A.B. Why green absorptive capacity and managerial environmental concerns matter for corporate environmental entrepreneurship? Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 102295–102312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Razzaq, A.; Mohsin, M.; Irfan, M. Spatial spillovers and threshold effects of internet development and entrepreneurship on green innovation efficiency in China. Technol. Soc. 2022, 68, 101844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimante, D.; Tambovceva, T.; Atstaja, D. Raising environmental awareness through education. Int. J. Contin. Eng. Educ. Life-Long Learn. 2016, 26, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparicio, S.; Urbano, D.; Audretsch, D. Institutional factors, opportunity entrepreneurship and economic growth: Panel data evidence. Technol. Forecast. Soc. 2016, 102, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, G. From green entrepreneurial intentions to green entrepreneurial behaviors: The role of university entrepreneurial support and external institutional support. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2021, 17, 963–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amankwah, J.; Sesen, H. On the Relation between Green Entrepreneurship Intention and Behavior. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, F.; Fayolle, A. A systematic literature review on entrepreneurial intentions: Citation, thematic analyses, and research agenda. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2015, 11, 907–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, I.; Nazir, M.; Hashmi, S.B.; Di Vaio, A.; Shaheen, I.; Waseem, M.A.; Arshad, A. Green and Sustainable Entrepreneurial Intentions: A Mediation-Moderation Perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Risco, A.; Mlodzianowska, S.; García-Ibarra, V.; Rosen, M.A.; Del-Aguila-Arcentales, S. Factors Affecting Green Entrepreneurship Intentions in Business University Students in COVID-19 Pandemic Times: Case of Ecuador. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabowo, H.; Ikhsan, R.B.; Yuniarty, Y. Drivers of Green Entrepreneurial Intention: Why Does Sustainability Awareness Matter Among University Students? Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 873140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabi, G.; Liñán, F.; Fayolle, A.; Krueger, N.; Walmsley, A. The Impact of Entrepreneurship Education in Higher Education: A Systematic Review and Research Agenda. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2017, 16, 277–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapero, A.; Shapero, A.; Sokol, L. The social dimensions of entrepreneurship. In Encyclopaedia of Entrepreneurship; Kent, C., Sexton, D., Vesper, K., Eds.; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1982; pp. 72–90. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger, N.F., Jr.; Reilly, M.D.; Carsrud, A.L. Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. J. Bus. Ventur. 2000, 15, 411–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Nguyen, L.T.P.; Phan, H.T.T.; Vu, A.T. Impact of Entrepreneurship Extracurricular Activities and Inspiration on Entrepreneurial Intention: Mediator and Moderator Effect. SAGE Open 2021, 11, 21582440211032174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arranz, N.; Ubierna, F.; Arroyabe, M.F.; Perez, C.; de Arroyabe, J.F. The effect of curricular and extracurricular activities on university students’ entrepreneurial intention and competences. Stud. High. Educ. 2017, 42, 1979–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldureanu, G.; Ionescu, A.M.; Bercu, A.-M.; Bedrule-Grigoruță, M.V.; Boldureanu, D. Entrepreneurship Education through Successful Entrepreneurial Models in Higher Education Institutions. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, B.C.; Lu, S.G. A Study on the Influencing Factors of College Graduates’ Entrepreneurial Intention and the Mechanism Involved. J. Xi’an Jiaotong Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2022, 42, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrielsson, M.; Raatikainen, M.; Julkunen, S. Accelerated Internationalization Among Inexperienced Digital Entrepreneurs: Toward a Holistic Entrepreneurial Decision-Making Model. Manag. Int. Rev. 2022, 62, 137–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Song, Z.; Gu, C. Research on the construction of green entrepreneurship education system. Guangxi Soc. Sci. 2020, 3, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hockerts, K. Determinants of Social Entrepreneurial Intentions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2017, 41, 105–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teodoreanu, I. Sustainable Business Education—A Romanian Perspective. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 109, 706–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lans, T.; Blok, V.; Wesselink, R. Learning apart and together: Towards an integrated competence framework for sustainable entrepreneurship in higher education. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 62, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, S.; Biemans, H.J.A.; Lans, T.; Chizari, M.; Mulder, M. The Impact of Entrepreneurship Education: A Study of Iranian Students’ Entrepreneurial Intentions and Opportunity Identification. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2016, 54, 187–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba-Sánchez, V.; Atienza-Sahuquillo, C. Entrepreneurial motivation and self-employment: Evidence from expectancy theory. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2017, 13, 1097–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacq, S.; Alt, E. Feeling capable and valued: A prosocial perspective on the link between empathy and social entrepreneurial intentions. J. Bus. Ventur. 2018, 33, 333–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, R.F.; Adams, J.S.; Carley, S.S.; Wiebe, F.A. Role Model Performance Effects on Development of Entrepreneurial Career Preference. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1989, 13, 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, D.A.; Patzelt, H. The New Field of Sustainable Entrepreneurship: Studying Entrepreneurial Action Linking “What is to be Sustained” with “What is to be Developed”. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2011, 35, 137–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanohov, R.; Baldacchino, L. Opportunity recognition in sustainable entrepreneurship: An exploratory study. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2017, 24, 333–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nițu-Antonie, R.D.; Feder, E.-S.; Stamenovic, K.; Brudan, A. A Moderated Serial–Parallel Mediation Model of Sustainable Entrepreneurial Intention of Youth with Higher Education Studies in Romania. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Huang, T.; Xiao, Y. Assessing the impact of entrepreneurial education activity on entrepreneurial intention and behavior: Role of behavioral entrepreneurial mindset. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 26292–26307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuorio, A.M.; Puumalainen, K.; Fellnhofer, K. Drivers of entrepreneurial intentions in sustainable entrepreneurship. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2017, 24, 359–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Hussain, S.; Zhang, Y. Factors That Can Promote the Green Entrepreneurial Intention of College Students: A Fuzzy Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 776886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarma, S.; Sun, S.L. The genesis of fabless business model: Institutional entrepreneurs in an adaptive ecosystem. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2017, 34, 587–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, R.W. Institutions and Organizations: Ideas, Interests & Identities [Internet]. Institutions and Organizations: Ideas, Interests, and Identities. 2013. Available online: http://www.researchgate.net/publication/235413341_Institutions_and_Organizations_Ideas_and_Interests (accessed on 27 November 2023).

- Meek, W.R.; Pacheco, D.F.; York, J.G. The impact of social norms on entrepreneurial action: Evidence from the environmental entrepreneurship context. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 493–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welter, F.; Smallbone, D. Institutional Perspectives on Entrepreneurial Behavior in Challenging Environments. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2011, 49, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puffer, S.M.; McCarthy, D.J.; Boisot, M. Entrepreneurship in Russia and China: The Impact of Formal Institutional Voids. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2010, 34, 441–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenholm, P.; Acs, Z.J.; Wuebker, R. Exploring country-level institutional arrangements on the rate and type of entrepreneurial activity. J. Bus. Ventur. 2013, 28, 176–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Venaik, S. The Effect of Corporate Political Activity on MNC Subsidiary Legitimacy: An Institutional Perspective. Manag. Int. Rev. 2018, 58, 813–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Tao, Z. Trends and determinants of China’s industrial agglomeration. J. Urban Econ. 2009, 65, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hörisch, J.; Johnson, M.P.; Schaltegger, S. Implementation of Sustainability Management and Company Size: A Knowledge-Based View. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2015, 24, 765–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lembana, D.A.A. The Intentionality-Based View of Company Employees’ Entrepreneurial Motivation and Institutional Environment. Open J. Bus. Manag. 2022, 10, 1436–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattab, H. Impact of Entrepreneurship Education on Entrepreneurial Intentions of University Students in Egypt. J. Entrep. 2014, 23, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huggins, R.; Thompson, P. Human agency, entrepreneurship and regional development: A behavioural perspective on economic evolution and innovative transformation. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2020, 32, 573–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, H.; Ye, Y. Entrepreneurship Education Matters: Exploring Secondary Vocational School Students’ Entrepreneurial Intention in China. Asia-Pac. Educ. Res. 2018, 27, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entrialgo, M.; Iglesias, V. Are the Intentions to Entrepreneurship of Men and Women Shaped Differently? The Impact of Entrepreneurial Role-Model Exposure and Entrepreneurship Education. Entrep. Res. J. 2018, 8, 20170013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ma, Y. Innovation and Entrepreneurship Education in Chinese Universities: Developments and Challenges. Chin. Educ. Soc. 2022, 55, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, J.W.; Gómez, C. The relationship among national institutional structures, economic factors, and domestic entrepreneurial activity: A multicountry study. J. Bus. Res. 2004, 57, 1098–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).