Navigating Sustainable Value Creation Through Digital Leadership Under Institutional Pressures: The Moderating Role of Environmental Turbulence

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Institutional Theory

2.2. Digital Leadership

2.3. Environmental Turbulence

2.4. Sustainable Performance

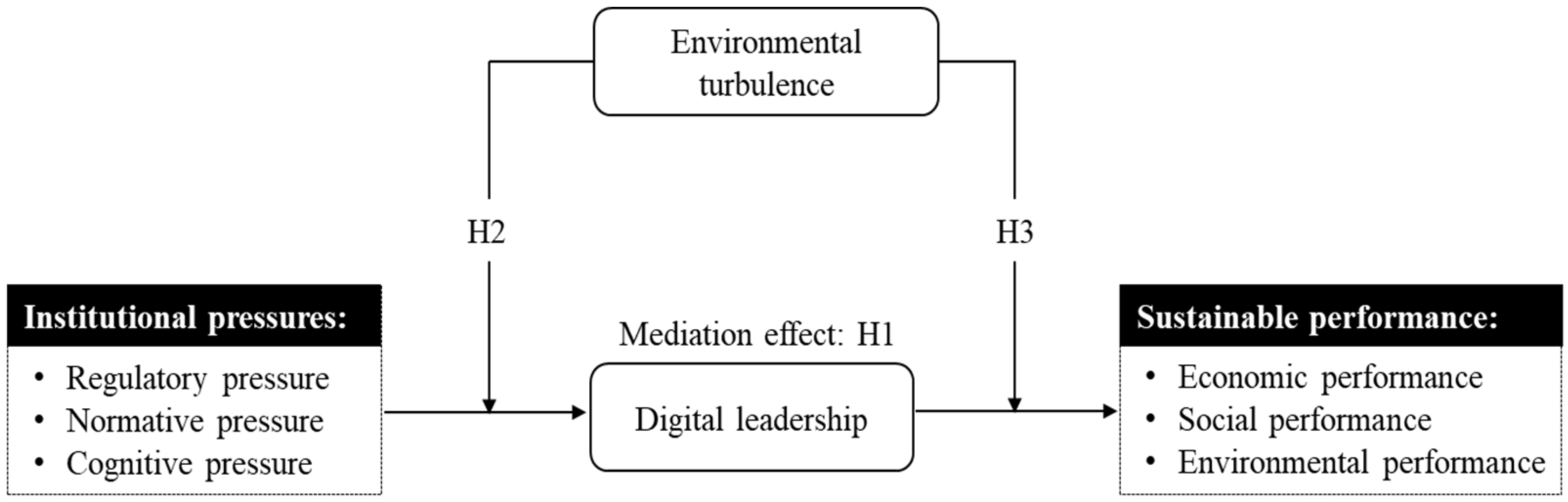

3. Hypothesis Development

3.1. The Mediating Role of Digital Leadership

3.2. The Moderating Role of Environmental Turbulence

4. Methodology

4.1. Research Context and Sample Collection

4.2. Measures

4.3. Common Method Bias Test

4.4. Analysis Methods and Measurement Assessment

4.5. Hypotheses Tests

5. Discussion and Implications

5.1. Discussion

5.2. Theoretical Contributions

5.3. Practical Implications

5.4. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Measurement and Factor Loadings

| Constructs | Measures | Loadings |

| Regulatory pressure [14] | ||

| - Adhering to the government’s stringent regulations is crucial for our firm. | 0.946 | |

| - Government policy (e.g., preferential tax) increases our firm’s willingness to implement innovation. | 0.958 | |

| - Implementing innovation makes it beneficial for our firm to receive the local government’s favorable treatment. | 0.922 | |

| Normative pressure [14] | ||

| - Customers put pressure on our firm’s management to adopt practices. | 0.924 | |

| - Suppliers put pressure on our firm’s management to adopt practices. | 0.910 | |

| - The actions of our competitors have put pressure on our management to adopt practices. | 0.916 | |

| Cognitive pressure [14] | ||

| - Awareness of eco-friendly strategies of producers of the same or substitute products. | 0.943 | |

| - Awareness of industry best practices. | 0.966 | |

| - Customers’ environmental consciousness. | 0.949 | |

| Digital leadership [72] | ||

| - Awareness of employees about the risks associated with digital technology. | 0.901 | |

| - Awareness of the digital technology that can be used to improve organizational processes. | 0.898 | |

| - Efforts to reduce resistance to digital technology innovation. | 0.942 | |

| - Efforts to share experience and know-how on technical possibilities. | 0.884 | |

| Environmental turbulence [47] | ||

| - Customer tastes and preferences in our market are highly unpredictable. | 0.909 | |

| - Our market faces intense competition. | 0.908 | |

| - The technology in our industry evolves rapidly. | 0.871 | |

| - Technological advancements present significant opportunities in our industry. | 0.916 | |

| Economic performance [3] | ||

| - Our profit growth outperforms major industry competitors. | 0.938 | |

| - Our return on investment growth exceeds that of industry leaders. | 0.953 | |

| - Our return on sales growth surpasses that of key industry competitors. | 0.926 | |

| Social performance [3] | ||

| - Reduces social inequality, including polarization and regional income disparity. | 0.965 | |

| - Promotes social values such as labor rights and revitalization of local communities. | 0.968 | |

| - Improves worker or community health and safety. | 0.963 | |

| Environmental performance [3] | ||

| - Reduces energy consumption. | 0.958 | |

| - Decreases waste emissions, including air, water, and solid waste. | 0.959 | |

| - Minimizes the environmental impact of its products or services. | 0.969 | |

References

- Hosta, M.; Zabkar, V. Antecedents of environmentally and socially responsible sustainable consumer behavior. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 171, 273–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.-J.; Roh, T. Unpacking the sustainable performance in the business ecosystem: Coopetition strategy, open innovation, and digitalization capability. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 412, 137433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.J.; Pak, A.; Roh, T. The interplay of institutional pressures, digitalization capability, environmental, social, and governance strategy, and triple bottom line performance: A moderated mediation model. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 5247–5268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhu, X.; Lee, M.-J. Exploring institutional pressures, green innovation, and sustainable performance: Examining the mediated moderation role of entrepreneurial orientation. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. 25 years ago I coined the phrase “triple bottom line”. Here’s why it’s time to rethink it. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2018, 25, 2–5. [Google Scholar]

- Dmytriyev, S.D.; Freeman, R.E.; Hörisch, J. The relationship between stakeholder theory and corporate social responsibility: Differences, similarities, and implications for social issues in management. J. Manag. Stud. 2021, 58, 1441–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Feijoo, B.; Romero, S.; Ruiz, S. Effect of stakeholders’ pressure on transparency of sustainability reports within the GRI framework. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 122, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, G.; Merrill, R.K.; Schillebeeckx, S.J. Digital sustainability and entrepreneurship: How digital innovations are helping tackle climate change and sustainable development. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2021, 45, 999–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Zhao, C.; Lee, M.-J. Institutional Pressures on Sustainability and Green Performance: The Mediating Role of Digital Business Model Innovation. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alda, M. Corporate sustainability and institutional shareholders: The pressure of social responsible pension funds on environmental firm practices. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 1060–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunarathne, A.N.; Lee, K.H.; Hitigala Kaluarachchilage, P.K. Institutional pressures, environmental management strategy, and organizational performance: The role of environmental management accounting. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 825–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodstein, J.D. Institutional pressures and strategic responsiveness: Employer involvement in work-family issues. Acad. Manag. J. 1994, 37, 350–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colwell, S.R.; Joshi, A.W. Corporate ecological responsiveness: Antecedent effects of institutional pressure and top management commitment and their impact on organizational performance. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2013, 22, 73–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, N.K.; Panda, A.; Choudhary, P. Institutional pressures and circular economy performance: The role of environmental management system and organizational flexibility in oil and gas sector. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 3509–3525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, T.N.; Baird, K. The comprehensiveness of environmental management systems: The influence of institutional pressures and the impact on environmental performance. J. Environ. Manag. 2015, 160, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, R.; Gunasekaran, A.; Ali, S.S. Exploring the relationship between leadership, operational practices, institutional pressures and environmental performance: A framework for green supply chain. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2015, 160, 120–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kindermann, B.; Beutel, S.; de Lomana, G.G.; Strese, S.; Bendig, D.; Brettel, M. Digital orientation: Conceptualization and operationalization of a new strategic orientation. Eur. Manag. J. 2021, 39, 645–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavez, R.; Yu, W.; Sadiq Jajja, M.S.; Lecuna, A.; Fynes, B. Can entrepreneurial orientation improve sustainable development through leveraging internal lean practices? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 2211–2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Vaio, A.; Varriale, L. Blockchain technology in supply chain management for sustainable performance: Evidence from the airport industry. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 52, 102014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamble, S.S.; Gunasekaran, A.; Gawankar, S.A. Achieving sustainable performance in a data-driven agriculture supply chain: A review for research and applications. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 219, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadova, G.; Delgado-Marquez, B.; Pedauga, L.E. The curvilinear relationship between digitalization and firm‘s environmental performance. In Academy of Management Proceedings; Academy of Management: Briarcliff Manor, NY, USA, 2021; p. 13605. [Google Scholar]

- Corbett, C.J. How sustainable is big data? Prod. Oper. Manag. 2018, 27, 1685–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Dai, J.; Cui, L. The impact of digital technologies on economic and environmental performance in the context of industry 4.0: A moderated mediation model. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 229, 107777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calantone, R.; Garcia, R.; Dröge, C. The effects of environmental turbulence on new product development strategy planning. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2003, 20, 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, K.-P.; Chou, C. The impact of open innovation on firm performance: The moderating effects of internal R&D and environmental turbulence. Technovation 2013, 33, 368–380. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Qureshi, I.; Guo, F.; Zhang, Q. Corporate Social Responsibility and Disruptive Innovation: The moderating effects of environmental turbulence. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 139, 1435–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.e.; Teng, X.; Le, Y.; Li, Y. Strategic orientations and responsible innovation in SMEs: The moderating effects of environmental turbulence. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 2522–2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Geng, C.; Yao, N. How does green digitalization affect environmental innovation? The moderating role of institutional forces. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 3088–3105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coreynen, W.; Matthyssens, P.; Vanderstraeten, J.; van Witteloostuijn, A. Unravelling the internal and external drivers of digital servitization: A dynamic capabilities and contingency perspective on firm strategy. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020, 89, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broccardo, L.; Truant, E.; Dana, L.-P. The interlink between digitalization, sustainability, and performance: An Italian context. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 158, 113621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghobakhloo, M. Industry 4.0, digitization, and opportunities for sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 252, 119869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-S. The driver of green innovation and green image–green core competence. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 81, 531–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L.; Hu, D.; Wang, Y. How do firms achieve sustainability through green innovation under external pressures of environmental regulation and market turbulence? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 2695–2714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, W.R.; Meyer, J.W. Institutional Environments and Organizations: Structural Complexity and Individualism; Sage: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Jepperson, R.L.; Meyer, J.W. Institutional Theory: The Cultural Construction of Organizations, States, and Identities; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, W.R. Institutions and Organizations: Ideas and Interests; Sage: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ritala, P.; Baiyere, A.; Hughes, M.; Kraus, S. Digital strategy implementation: The role of individual entrepreneurial orientation and relational capital. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 171, 120961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broccardo, L.; Zicari, A.; Jabeen, F.; Bhatti, Z.A. How digitalization supports a sustainable business model: A literature review. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 187, 122146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, G.; Schillebeeckx, S.J. Digital transformation, sustainability, and purpose in the multinational enterprise. J. World Bus. 2022, 57, 101326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellemans, I.; Porter, A.J.; Diriker, D. Harnessing digitalization for sustainable development: Understanding how interactions on sustainability-oriented digital platforms manage tensions and paradoxes. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 668–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasiri, M.; Saunila, M.; Rantala, T.; Ukko, J. Sustainable innovation among small businesses: The role of digital orientation, the external environment, and company characteristics. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 30, 703–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendig, D.; Schulz, C.; Theis, L.; Raff, S. Digital orientation and environmental performance in times of technological change. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 188, 122272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Close, K.; Faure, N.; Hutchinson, R. How Tech Offers a Faster Path to Sustainability; Boston Consulting Group: Boston, MA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee, L.; Feng, C.; Nakata, C.; Sivakumar, K. The environmental turbulence concept in marketing: A look back and a look ahead. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 161, 113775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wang, L. Strategic choices of exploration and exploitation alliances under market uncertainty. Manag. Decis. 2019, 57, 3112–3133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohli, A.K.; Jaworski, B.J. Market orientation: The construct, research propositions, and managerial implications. J. Mark. 1990, 54, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L. Digital transformation and sustainable performance: The moderating role of market turbulence. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2022, 104, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drobyazko, S.; Okulich-Kazarin, V.; Rogovyi, A.; Goltvenko, O.; Marova, S. Factors of influence on the sustainable development in the strategy management of corporations. Acad. Strateg. Manag. J. 2019, 18, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- World Commission on Environment and Development. Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Goyal, P.; Rahman, Z.; Kazmi, A.A. Corporate sustainability performance and firm performance research: Literature review and future research agenda. Manag. Decis. 2013, 51, 361–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusliza, M.Y.; Yong, J.Y.; Tanveer, M.I.; Ramayah, T.; Faezah, J.N.; Muhammad, Z. A structural model of the impact of green intellectual capital on sustainable performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 249, 119334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Linde, C.v.d. Toward a new conception of the environment-competitiveness relationship. J. Econ. Perspect. 1995, 9, 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrone, P.; Fosfuri, A.; Gelabert, L.; Gomez-Mejia, L.R. Necessity as the mother of ‘green’inventions: Institutional pressures and environmental innovations. Strateg. Manag. J. 2013, 34, 891–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, M.A.; Toffel, M.W. Organizational responses to environmental demands: Opening the black box. Strateg. Manag. J. 2008, 29, 1027–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Cantor, D.E.; Montabon, F.L. How environmental management competitive pressure affects a focal firm‘s environmental innovation activities: A green supply chain perspective. J. Bus. Logist. 2015, 36, 242–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Marchi, V. Environmental innovation and R&D cooperation: Empirical evidence from Spanish manufacturing firms. Res. Policy 2012, 41, 614–623. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, C. Strategic responses to institutional processes. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1991, 16, 145–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Business models and dynamic capabilities. Long Range Plan. 2018, 1, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudsen, E.S.; Lien, L.B.; Timmermans, B.; Belik, I.; Pandey, S. Stability in turbulent times? The effect of digitalization on the sustainability of competitive advantage. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 128, 360–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzidia, S.; Makaoui, N.; Bentahar, O. The impact of big data analytics and artificial intelligence on green supply chain process integration and hospital environmental performance. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 165, 120557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias-Pérez, J.; Vélez-Jaramillo, J. Ignoring the three-way interaction of digital orientation, Not-invented-here syndrome and employee‘s artificial intelligence awareness in digital innovation performance: A recipe for failure. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 174, 121305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Zhang, L.; Lei, Z.; Huang, X. Investigating the impact of digital orientation on economic and environmental performance based on a strategy-structure-performance framework. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2023, 26, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danneels, E.; Sethi, R. New product exploration under environmental turbulence. Organ. Sci. 2011, 22, 1026–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, S.; Meyer, K.; Day, M. Building dynamic capabilities of adaptation and innovation: A study of micro-foundations in a transition economy. Long Range Plan. 2014, 47, 186–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Guo, F.; Shi, Q. Ranking effect in air pollution governance: Evidence from Chinese cities. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 251, 109600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Shu, C.; Jiang, W.; Gao, S. Green management, firm innovations, and environmental turbulence. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 567–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Wang, A.X.; Zhou, K.Z.; Jiang, W. Environmental strategy, institutional force, and innovation capability: A managerial cognition perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 159, 1147–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y. E-Commerce in China—Statistics & Facts; Statista: Hamburg, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; He, Y.; Song, M. Global value chains, technological progress, and environmental pollution: Inequality towards developing countries. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 277, 110999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, S.S.; Lew, Y.K.; Park, B.I. International network searching, learning, and explorative capability: Small and medium-sized enterprises from China. Manag. Int. Rev. 2020, 60, 597–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.; Mollah, M.A.; Choi, J. Sustainability and organizational performance in South Korea: The effect of digital leadership on digital culture and employees’ digital capabilities. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mithas, S.; Tafti, A.; Mitchell, W. How a firm‘s competitive environment and digital strategic posture influence digital business strategy. MIS Q. 2013, 37, 511–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.-J.; Van Witteloostuijn, A.; Eden, L. Common method variance in international business research. In Research Methods in International Business; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 385–398. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. Int. J. E-Collab. 2015, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wetzels, M.; Odekerken-Schröder, G.; van Oppen, C. Using PLS path modeling for assessing hierarchial construct models: Guidelines and impirical illustration. MIS Q. 2009, 33, 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Hubona, G.; Ray, P.A. Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: Updated guidelines. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2016, 116, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geisser, S. A predictive approach to the random effect model. Biometrika 1974, 61, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, M. Cross-validation and multinomial prediction. Biometrika 1974, 61, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. The partial least squares approach for structural equation modeling. In Modern Methods for Business Research; Marcoulides, G.A., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1998; pp. 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fauzi, A.A.; Sheng, M.L. The digitalization of micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs): An institutional theory perspective. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2022, 60, 1288–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, M.C. Big data and service operations. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2018, 27, 1709–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, J. How does digital leadership improve organizational sustainability: Theory and evidence. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 434, 140148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, M.; Kruschwitz, N.; Bonnet, D.; Welch, M. Embracing digital technology: A new strategic imperative. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2014, 55, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Ch’ng, P.-C.; Cheah, J.; Amran, A. Eco-innovation practices and sustainable business performance: The moderating effect of market turbulence in the Malaysian technology industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 283, 124556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, K.-H.; Yang, S.-Y. Firm innovativeness and business performance: The joint moderating effects of market turbulence and competition. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2013, 42, 1279–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raguseo, E.; Vitari, C. Investments in big data analytics and firm performance: An empirical investigation of direct and mediating effects. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2018, 56, 5206–5221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, Q.; Ahmad, N.H.; Li, Z. Frugal-based innovation model for sustainable development: Technological and market turbulence. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2021, 42, 396–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogbeibu, S.; Emelifeonwu, J.; Senadjki, A.; Gaskin, J.; Kaivo-oja, J. Technological turbulence and greening of team creativity, product innovation, and human resource management: Implications for sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 244, 118703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Mavondo, F.T.; Saunders, S.G. The relationship between marketing agility and financial performance under different levels of market turbulence. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2019, 83, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.J.; Kim, Y.; Roh, T. Exploring the role of digital servitization for green innovation: Absorptive capacity, transformative capacity, and environmental strategy. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2024, 207, 123614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Frequency (N) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Industry type | ||

| Manufacturing | 249 | 49.0 |

| Service industry | 139 | 27.4 |

| Others (construction, transportation, energy, etc.) | 120 | 23.6 |

| Firm size (number of full-time employees) | ||

| Less than 100 people | 46 | 9.1 |

| 100–199 | 86 | 16.9 |

| 200–499 | 70 | 13.8 |

| 500–999 | 212 | 41.7 |

| More than 1000 people | 94 | 18.5 |

| Firm age | ||

| Less than 10 years | 182 | 35.8 |

| 10–19 | 181 | 35.6 |

| 20–29 | 47 | 9.3 |

| More than 30 years | 98 | 19.3 |

| N | 508 | 100 |

| Construct | 01 | 02 | 03 | 04 | 05 | 06 | 07 | 08 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01. RP | 0.942 | |||||||

| 02. NP | 0.261 | 0.917 | ||||||

| 03. CP | 0.273 | 0.730 | 0.952 | |||||

| 04. DL | 0.299 | 0.646 | 0.660 | 0.906 | ||||

| 05. ET | 0.307 | 0.615 | 0.576 | 0.657 | 0.901 | |||

| 06. ECP | 0.350 | 0.695 | 0.687 | 0.704 | 0.701 | 0.939 | ||

| 07. SOP | 0.352 | 0.695 | 0.689 | 0.750 | 0.695 | 0.802 | 0.966 | |

| 08. ENP | 0.316 | 0.681 | 0.659 | 0.723 | 0.672 | 0.766 | 0.806 | 0.962 |

| Cronbach’s alpha | 0.937 | 0.905 | 0.949 | 0.927 | 0.923 | 0.933 | 0.964 | 0.960 |

| rho_a | 0.948 | 0.905 | 0.952 | 0.929 | 0.923 | 0.933 | 0.964 | 0.960 |

| AVE | 0.887 | 0.840 | 0.907 | 0.821 | 0.812 | 0.882 | 0.932 | 0.926 |

| R2 | 0.611 | 0.623 | 0.662 | 0.616 | ||||

| Q2 | 0.593 | 0.595 | 0.609 | 0.578 | ||||

| HTMT < 0.85 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Path | β | S.E. | t-Statistic | p-Value | BCCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RP → DL | 0.006 | 0.032 | 0.180 | 0.857 | |

| NP → DL | 0.130 | 0.044 | 2.967 | 0.003 | |

| CP → DL | 0.222 | 0.043 | 5.111 | 0.000 | |

| DL → ECP | 0.313 | 0.040 | 7.761 | 0.000 | |

| DL → SOP | 0.400 | 0.047 | 8.527 | 0.000 | |

| DL → ENP | 0.383 | 0.038 | 10.009 | 0.000 | |

| ET → DL | 0.209 | 0.056 | 3.707 | 0.000 | |

| ET → ECP | 0.306 | 0.048 | 6.412 | 0.000 | |

| ET → SOP | 0.243 | 0.043 | 5.625 | 0.000 | |

| ET → ENP | 0.237 | 0.043 | 5.464 | 0.000 | |

| RP → DL → ECP | 0.002 | 0.010 | 0.178 | 0.859 | −0.017, 0.023 |

| RP → DL → SOP | 0.002 | 0.013 | 0.177 | 0.860 | −0.021, 0.031 |

| RP → DL → ENP | 0.002 | 0.012 | 0.178 | 0.859 | −0.021, 0.028 |

| NP → DL → ECP | 0.040 | 0.016 | 2.587 | 0.010 | 0.013, 0.074 |

| NP → DL → SOP | 0.052 | 0.020 | 2.553 | 0.010 | 0.017, 0.097 |

| NP → DL → ENP | 0.050 | 0.019 | 2.666 | 0.008 | 0.017, 0.089 |

| CP → DL → ECP | 0.069 | 0.017 | 4.047 | 0.000 | 0.038, 0.105 |

| CP → DL → SOP | 0.089 | 0.022 | 3.959 | 0.000 | 0.048, 0.136 |

| CP → DL → ENP | 0.085 | 0.019 | 4.502 | 0.000 | 0.050, 0.123 |

| RP × ET → DL | −0.012 | 0.019 | 0.642 | 0.521 | |

| NP × ET → DL | −0.121 | 0.046 | 2.637 | 0.008 | |

| CP × ET → DL | −0.052 | 0.041 | 1.274 | 0.209 | |

| DL × ET → ECP | −0.126 | 0.023 | 5.454 | 0.000 | |

| DL × ET → SOP | -0.126 | 0.023 | 5.592 | 0.000 | |

| DL × ET → ENP | −0.122 | 0.021 | 5.878 | 0.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

He, Y.; Liu, Z.; Lee, M.-J. Navigating Sustainable Value Creation Through Digital Leadership Under Institutional Pressures: The Moderating Role of Environmental Turbulence. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9169. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16219169

He Y, Liu Z, Lee M-J. Navigating Sustainable Value Creation Through Digital Leadership Under Institutional Pressures: The Moderating Role of Environmental Turbulence. Sustainability. 2024; 16(21):9169. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16219169

Chicago/Turabian StyleHe, Yan, Zhaoshu Liu, and Min-Jae Lee. 2024. "Navigating Sustainable Value Creation Through Digital Leadership Under Institutional Pressures: The Moderating Role of Environmental Turbulence" Sustainability 16, no. 21: 9169. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16219169

APA StyleHe, Y., Liu, Z., & Lee, M.-J. (2024). Navigating Sustainable Value Creation Through Digital Leadership Under Institutional Pressures: The Moderating Role of Environmental Turbulence. Sustainability, 16(21), 9169. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16219169