Pro-Environmental Behavior of Tourists in Ecotourism Scenic Spots: The Promoting Role of Tourist Experience Quality in Place Attachment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Tourist Experience Quality

2.2. Place Attachment

2.3. Pro-Environmental Behavior

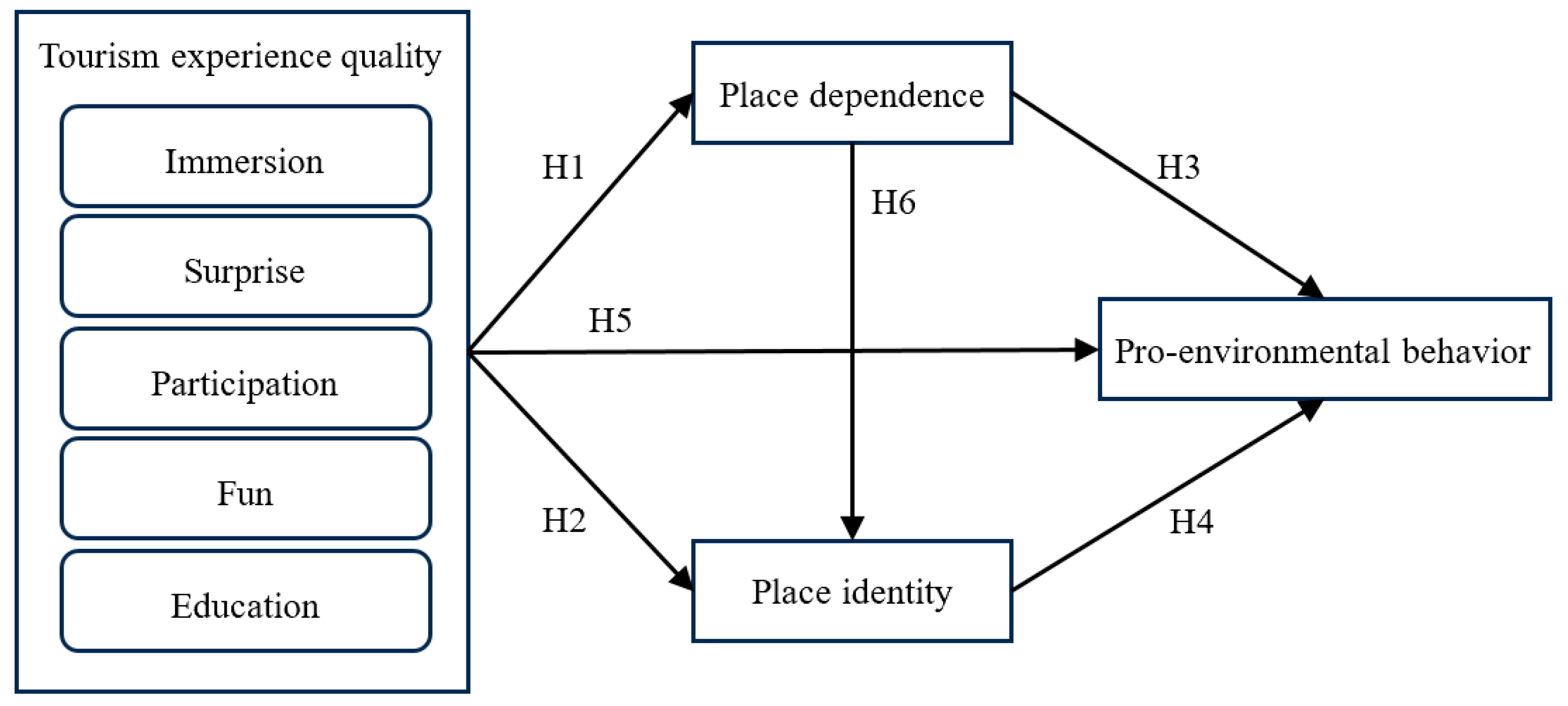

3. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

3.1. The Effect of Tourist Experience Quality on Place Attachment

3.2. The Effect of Place Attachment on Pro-Environmental Behavior

3.3. The Effect of Tourists Experience Quality on Pro-Environmental Behavior

3.4. The Influence of Place Dependence on Place Identity

4. Study Design

4.1. Study Site

4.2. Scale Development

4.3. Data Collection

4.4. Research Approach

5. Empirical Analysis

5.1. Study 1

5.1.1. Sample Profile

5.1.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis

5.1.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

5.1.4. Fit Test and Model Modification

5.1.5. Results of the Model

5.1.6. Mediation-Effect Test

5.2. Study 2

5.2.1. Sample Profile

5.2.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis

5.2.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

5.2.4. Fit Test and Model Modification

5.2.5. Results for the Model

5.2.6. Mediation-Effect Test

6. Conclusions and Recommendation

6.1. Conclusions and Discussion

6.2. Recommendation

7. Limitation and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Das, M.; Chatterjee, B. Ecotourism: A panacea or a predicament? Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2015, 14, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Jan, F.H. Can community-based tourism contribute to sustainable development? Evidence from residents’ perceptions of the sustainability. Tour. Manag. 2019, 70, 368–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, R.; Cater, C.; Zhong, L.; Chen, T. Shengtai luyou: Cross-cultural comparison in ecotourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2008, 35, 945–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deery, M.; Jago, L.; Fredline, L. Rethinking social impacts of tourism research: A new research agenda. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Ping, Y.; Pan, X.; Wang, Y. Does Ecotourism in Nature Reserves Have an Impact on Farmers’ Income? Counterfactual Estimates Based on Propensity Score Matching. Agriculture 2024, 14, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, G. Is ecotourism sustainable? Environ. Manag. 1997, 21, 483–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wondirad, A. Does ecotourism contribute to sustainable destination development, or is it just a marketing hoax? Analyzing twenty-five years contested journey of ecotourism through a meta-analysis of tourism journal publications. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 24, 1047–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, S.; Alam, K.; Beaumont, N. Environmental orientations and environmental behavior: Perceptions of protected area tourism stakeholders. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 290–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Tang, P.; Jiang, L.; Su, M. Influencing mechanism of tourist social responsibility awareness on environmentally responsible behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 271, 122565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, F.; Weaver, D.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, M.; Tang, C.; Liu, Y. Toward an ecological civilization: Mass comprehensive ecotourism indications among domestic visitors to a Chinese wetland protected area. Tour. Manag. 2019, 70, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yao, C.; Xu, D. Ecological compensation standards of national scenic spots in western China: A case study of Taibai Mountain. Tour. Manag. 2020, 76, 103950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kousis, M. Tourism and the environment: A social movements perspective. Ann. Tour. Res. 2000, 27, 468–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayati, Y.; Adrianto, L.; Krisanti, M.; Pranowo, W.; Kurniawan, F. Magnitudes and tourist perception of marine debris on small tourism island: Assessment of Tidung Island, Jakarta, Indonesia. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 158, 111393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorpas, A.A.; Voukkali, I.; Loizia, P. The impact of tourist sector in the waste management plans. Desalination Water Treat. 2015, 56, 1141–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolnicar, S.; Leisch, F. An investigation of tourists’ patterns of obligation to protect the environment. J. Travel Res. 2008, 46, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Vlek, C. Encouraging pro-environmental behaviour: An integrative review and research agenda. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becken, S. Tourists’ perception of international air travel’s impact on the global climate and potential climate change policies. J. Sustain. Tour. 2007, 15, 351–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilynets, I.; Cvelbar, L.K. Tourist pro-environmental behaviour: The role of environmental image of destination and daily behaviour. Ann. Tour. Res. Empir. Insights 2022, 3, 100070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.; Merrilees, B.; Coghlan, A. Sustainable urban tourism: Understanding and developing visitor pro-environmental behaviours. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 26–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esfandiar, K.; Pearce, J.; Dowling, R.; Goh, E. Pro-environmental behaviours in protected areas: A systematic literature review and future research directions. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2022, 41, 100943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Swanson, S.R. The effect of destination social responsibility on tourist environmentally responsible behavior: Compared analysis of first-time and repeat tourists. Tour. Manag. 2017, 60, 308–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, J.; Yu, P.; Hu, H. The theory of planned behavior as a model for understanding tourists’ responsible environmental behaviors: The moderating role of environmental interpretations. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 194, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, J.; Cao, J.; Duan, X.; Hu, Q. The impact of behavioral reference on tourists’ responsible environmental behaviors. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 694, 133698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, V. Examining environmental friendly behaviors of tourists towards sustainable development. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 276, 111292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.; Lee, S.; Lee, C.K.; Reisinger, Y. Volunteer tourists’ environmentally friendly behavior and support for sustainable tourism development using Value-Belief-Norm theory: Moderating role of altruism. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2022, 25, 100712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, L.R.; Stedman, R.C.; Cooper, C.B.; Decker, D.J. Understanding the multi-dimensional structure of pro-environmental behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 43, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolnicar, S.; Knezevic Cvelbar, L.; Grün, B. Do pro-environmental appeals trigger pro-environmental behavior in hotel guests? J. Travel Res. 2017, 56, 988–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Huang, L.; Whitmarsh, L. Home and away: Cross-contextual consistency in tourists’ pro-environmental behavior. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 1443–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasci, A.D.; Gartner, W.C. Destination image and its functional relationships. J. Travel Res. 2007, 45, 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grove, S.J.; Fisk, R.P.; Bitner, M.J. Dramatizing the service experience: A managerial approach. Adv. Serv. Mark. Manag. 1992, 1, 91–121. [Google Scholar]

- Kao, Y.F.; Huang, L.S.; Wu, C.H. Effects of theatrical elements on experiential quality and loyalty intentions for theme parks. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2008, 13, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.C.; Li, T. A study of experiential quality, perceived value, heritage image, experiential satisfaction, and behavioral intentions for heritage tourists. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2017, 41, 904–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A. Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T. Tourist experience quality and satisfaction: Connotation, relationship and measurement. Tour. Trib. 2019, 34, 29–40. [Google Scholar]

- MacKay, K.J.; Crompton, J.L. A conceptual model of consumer evaluation of recreation service quality. Leis. Stud. 1988, 7, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, J.L.; Love, L.L. The predictive validity of alternative approaches to evaluating quality of a festival. J. Travel Res. 1995, 34, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.K.L.; Baum, T. Eco-tourists’ perception of ecotourism experience in lower Kinabatangan, Sabah, Malaysia. J. Sustain. Tour. 2007, 15, 574–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, W.H.; Chan, C.C.; Han, A.C. A study of experiential quality, experiential value, trust, corporate reputation, experiential satisfaction and behavioral intentions for cruise tourists: The case of Hong Kong. Tour. Manag. 2018, 66, 200–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, J.E.; Ritchie, J.R.B. The service experience in tourism. Tour. Manag. 1996, 17, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, S.T.; Scott, D. Examining the Mediating Role of Experience Quality in a Model of Tourist Experiences. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2004, 16, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.C.; Li, M.Y.; Li, T. A study of experiential quality, experiential value, experiential satisfaction, theme park image, and revisit intention. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2018, 42, 26–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, C.D.; Camarero, C. Visitors’ experience, mood and satisfaction in a heritage context: Evidence from an interpretation center. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 525–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.F.; Chen, F.S. Experience quality, perceived value, satisfaction and behavioral intentions for heritage tourists. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, N.P.; Lee, S.; Lee, H. The effect of experience quality on perceived value, satisfaction, image and behavioral intention of water park patrons: New versus repeat visitor. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2015, 17, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, H.; Han, H. Tourist Experience Quality and Loyalty to an Island Destination: The Moderating Impact of Destination Image. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhartanto, D.; Brien, A.; Primiana, I.; Wibisono, N.; Triyuni, N.N. Tourist loyalty in creative tourism: The role of experience quality, value, satisfaction, and motivation. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 23, 867–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scannell, L.; Gifford, R. Defining place attachment: A tripartite organizing framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewicka, M. Place attachment: How far have we come in the last 40 years? J. Environ. Psychol. 2011, 31, 207–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasarda, J.D.; Janowitz, M. Community attachment in mass society. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1974, 39, 328–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stedman, R.C. Toward a social psychology of place: Predicting behavior from place-based cognitions, attitude, and identity. Environ. Behav. 2002, 34, 561–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, B.; Martín, A.M.; Ruiz, C.; Hidalgo, M.C. The role of place identity and place attachment in breaking environmental protection laws. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Pan, L.; Hu, Y. Cultural involvement and attitudes toward tourism: Examining serial mediation effects of residents’ spiritual wellbeing and place attachment. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 20, 100601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram, Y.; Bjork, P.; Weidenfeld, A. Authenticity and place attachment of major visitor attractions. Tour. Manag. 2016, 52, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, C.M.; Brown, G.; Weber, D. The measurement of place attachment: Personal, community, and environmental connections. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 422–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H.; Smith, L.D.G.; Weiler, B. Testing the dimensionality of place attachment and its relationships with place satisfaction and pro-environmental behaviours: A structural equation modelling approach. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 552–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, L.T.; Hui, D.L. Influence of residents’ place attachment on heritage forest conservation awareness in a peri-urban area of Guangzhou, China. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 33, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Lin, C.; Morais, D.B. Antecedents of Attachment to a Cultural Tourism Destination: The Case of Hakka and Non-Hakka Taiwanese Visitors to Pei-Pu, Taiwan. J. Travel Res. 2005, 44, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuksel, A.; Yuksel, F.; Bilim, Y. Destination Attachment: Effects on Consumer Satisfaction and Cognitive, Affective and Conative Loyalty. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 274–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G.; Ryan, C. Antecedents of tourists’ loyalty to Mauritius: The role and influence of destination image, place attachment, personal involvement, and satisfaction. J. Travel Res. 2012, 51, 342–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerard, K.; Alan, G.; Robert, M.; James, B. Effect of Activity Involvement and Place Attachment on Recreationists’ Perceptions of Setting Density. J. Leis. Res. 2004, 36, 209–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patwardhan, V.; Ribeiro, M.A.; Woosnam, K.M.; Payini, V.; Mallya, J. Visitors’ loyalty to religious tourism destinations: Considering place attachment, emotional experience and religious affiliation. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 36, 100737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyle, G.; Graefe, A.; Manning, R. Testing the dimensionality of place attachment in recreational settings. Environ. Behav. 2005, 37, 153–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, W.; Wei, W.; Ding, S.; Xue, J. The relationship between place attachment and tourist loyalty: A meta-analysis. Tour. Manag. 2022, 43, 100983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastenholz, E.; Marques, C.P.; Carneiro, M.J. Place attachment through sensory-rich, emotion-generating place experiences in rural tourism. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 17, 100455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vada, S.; Prentice, C.; Hsiao, A. The influence of tourism experience and well-being on place attachment. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 47, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Zhang, J. Antecedents and consequences of place attachment: A comparison of Chinese and Western urban tourists in Hangzhou, China. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2016, 5, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, L.; Wei, W. Consumers’ pro-environmental behavior and the underlying motivations: A comparison between household and hotel settings. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 32, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Park, H.; Kim, K.H.; Lee, C.K. A moderator of destination social responsibility for tourists’ pro-environmental behaviors in the vip model—Science direct. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 20, 100610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.-T.; Zhu, D.; Liu, C.; Kim, P.B. A meta-analysis of antecedents of pro-environmental behavioral intention of tourists and hospitality consumers. Tour. Manag. 2022, 93, 104566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.M.; Wu, H.C. How do environmental knowledge, environmental sensitivity, and place attachment affect environmentally responsible behavior? An integrated approach for sustainable island tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 557–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hwang, J. Cruise travelers’ environmentally responsible decision- making: An integrative framework of goal-directed behavior and norm activation process. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 53, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akintunde, A.E. Theories and concepts for human behavior in environmental preservation. J. Environ. Sci. Public Health 2017, 1, 120–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith-Sebasto, N.J.; D’Costa, A. Designing a Likert-type scale to predict environmentally responsible behavior in undergraduate students: A multistep process. J. Environ. Educ. 1995, 27, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Huang, S.; Pearce, J. How does destination social responsibility contribute to environmentally responsible behaviour? A destination resident perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 86, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.K.; Olya, H.; Ahmad, M.S.; Kim, K.H.; Oh, M.J. Sustainable intelligence, destination social responsibility, and pro-environmental behaviour of visitors: Evidence from an eco-tourism site. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 47, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, J.; Jang, S.S.; Zhao, Y. Understanding tourists’ environmentally responsible behavior at coastal tourism destinations. Mar. Policy 2022, 143, 105178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Q.; Hsu, C.H. Urban travelers’ pro-environmental behaviors: Composition and role of pro-environmental contextual force. Tour. Manag. 2022, 92, 104561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.M.; Wu, H.C.; Huang, L.M. The influence of place attachment on the relationship between destination attractiveness and environmentally responsible behavior for island tourism in Penghu, Taiwan. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 1166–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Kalof, L. Value orientations, gender, and environmental concern. Environ. Behav. 1993, 25, 322–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D.; Willits, F.K. Environmental attitudes and behavior: A Pennsylvania survey. Environ. Behav. 1994, 26, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tindall, D.B.; Davies, S.; Mauboules, C. Activism and conservation behavior in an environmental movement: The contradictory effects of gender. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2003, 16, 909–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Peterson, M.N.; Hull, V.; Lu, C.; Lee, G.D.; Hong, D.; Liu, J. Effects of attitudinal and sociodemographic factors on pro-environmental behaviour in urban China. Environ. Conserv. 2011, 38, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Huang, R. Employees’ pro-environmental behaviours at international hotel chains in China: The mediating role of environmental concerns. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2019, 39, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wu, H.C.; Hsieh, C.M.; Ramkissoon, H. Face consciousness, personal norms, and environmentally responsible behavior of Chinese tourists: Evidence from a lake tourism site. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2022, 50, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkaczynski, A.; Rundle-Thiele, S.; Truong, V.D. Influencing tourists’ pro-environmental behaviors: A social marketing application. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 36, 100740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daryanto, A.; Song, Z. A meta-analysis of the relationship between place attachment and pro-environmental behaviour. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 123, 208–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wu, J.S.; Che, T. Understanding perceived environment quality in affecting tourists’ environmentally responsible behaviors: A broken windows theory perspective. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 31, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H.; Weiler, B.; Smith, L.D. Place attachment and pro-environmental behavior in national parks: The development of a conceptual framework. J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 20, 257–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panwanitdumrong, K.; Chen, C.L. Investigating factors influencing tourists’ environmentally responsible behavior with extended theory of planned behavior for coastal tourism in Thailand. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 169, 112507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawler, E.J. An affect theory of social exchange. Am. J. Sociol. 2001, 107, 321–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubinstein, R.I.; Parmelee, P.A. Attachment to place and the representation of the life course by the elderly. In Place Attachment; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1992; pp. 139–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosany, S.; Prayag, G.; Veen, R.V.D.; Huang, S.S.; Deesilatham, S. Mediating effects of place attachment and satisfaction on the relationship between tourists’ emotions and intention to recommend. J. Travel Res. 2017, 56, 1079–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, S. Place attachment and tourism marketing: Investigating international tourists in Singapore. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2012, 14, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Io, M.-U. The relationships between positive emotions, place attachment, and place satisfaction in casino hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2018, 19, 167–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, N.; Halpenny, E.A. Tourists’ savoring of positive emotions and place attachment formation: A conceptual paper. Tour. Geogr. 2022, 24, 369–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Io, M.U.; Wan, P.Y.K. Relationships between tourism experiences and place attachment in the context of casino resorts. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2018, 19, 45–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.G.; Eves, A.; Scarles, C. Building a model of local food consumption on trips and holidays: A grounded theory approach. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 28, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton, C.E.; Lawrence, C. The relationship between place attachment, the theory of planned behaviour and residents’ response to place change. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 47, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.; Shen, G.Q.; Choi, S. The place-based approach to recycling intention: Integrating place attachment into the extended theory of planned behavior. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 169, 105549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.; Wang, X.; Morrison, A.M.; Kelly, C.; Wei, W. From ownership to responsibility: Extending the theory of planned behavior to predict tourist environmentally responsible behavioral intentions. J. Sustain. Tour. 2022, 30, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, P. Towards a developmental theory of place attachment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton, C.E.; Lawrence, C. Home is where the heart is: The effect of place of residence on place attachment and community participation. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 40, 451–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.L. What good are positive emotions? Rev. Gen. Psychol. 1998, 2, 300–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zins, A.H. Consumption emotions, experience quality and satisfaction: A structural analysis for complainers versus non-complainers. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2002, 12, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofman, K.; Walters, G.; Hughes, K. The effectiveness of virtual vs real-life marine tourism experiences in encouraging conservation behaviour. J. Sustain. Tour. 2022, 30, 742–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Chen, J.S.; Fan, L.; Lu, J. Tourist experience and wetland parks: A case of Zhejiang, China. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 1763–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, D.D.; Virden, R.J.; Van Riper, C.J. Effects of place identity, place dependence, and experience-use history on perceptions of recreation impacts in a natural setting. Environ. Manag. 2008, 42, 647–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ispas, A.; Untaru, E.N.; Candrea, A.N.; Han, H. Impact of place identity and place dependence on satisfaction and loyalty toward Black Sea Coastal Destinations: The role of visitation frequency. Coast. Manag. 2021, 49, 250–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.; Shen, G.Q.; Choi, S. Pathways of place dependence and place identity influencing recycling in the extended theory of planned behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 81, 101795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaske, J.J.; Kobrin, K.C. Place attachment and environmentally responsible behavior. J. Environ. Educ. 2001, 32, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, D.G.; Cummings, L.L.; Dunham, R.B.; Pierce, J.L. Single-item versus multiple-item measurement scales: An empirical comparison. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1998, 58, 898–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarpi, D.; Raggiotto, F. A construal level view of contemporary heritage tourism. Tour. Manag. 2023, 94, 104648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006; pp. 576–590. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, C.T. Memorable tourist experiences and place attachment when consuming local food. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 18, 536–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, L.H.; Kastenholz, E.; Barbosa, M.D.L.A.; Carvalho, M.S.E.S.C. Tourist experience, perceived authenticity, place attachment and loyalty when staying in a peer-to-peer accommodation. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2020, 6, 27–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, S.M.C. The role of the rural tourism experience economy in place attachment and behavioral intentions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 40, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlozi, S.; Pesämaa, O.; Haahti, A.; Salunke, S. Determinants of place identity and dependence: The case of international tourists in Tanzania. Tour. Cult. Commun. 2012, 12, 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Huang, L.; Xu, C.; He, K.; Shen, K.; Liang, P. Analysis of the mediating role of place attachment in the link between tourists’ authentic experiences of, involvement in, and loyalty to rural tourism. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, D.; DeSteno, D. Suffering and compassion: The links among adverse life experiences, empathy, compassion, and prosocial behavior. Emotion 2016, 16, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldassarri, D.; Grossman, G. The effect of group attachment and social position on prosocial behavior. Evidence from lab-in-the-field experiments. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e58750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharmin, F.; Sultan, M.T.; Badulescu, A.; Bac, D.P.; Li, B. Millennial tourists’ environmentally sustainable behavior towards a natural protected area: An integrative framework. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Ma, Y.; Ren, J. Influencing factors and mechanism of tourists’ pro-environmental behavior–Empirical analysis of the CAC-MOA integration model. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1060404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Value | Frequency | Percent (%) | Variable | Value | Frequency | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 173 | 43.69 | Education | Junior high school or below | 74 | 18.69 |

| Female | 223 | 56.31 | Senior high school | 99 | 25.00 | ||

| Age (years) | <20 | 11 | 2.78 | College degree | 172 | 43.43 | |

| 21–30 | 145 | 36.62 | Bachelor’s degree or above | 51 | 12.88 | ||

| 31–40 | 172 | 43.43 | Occupation | Farmer | 15 | 3.79 | |

| 41–50 | 34 | 8.59 | Individual operator | 20 | 5.05 | ||

| 51–60 | 20 | 5.05 | Service and sales personnel | 72 | 18.18 | ||

| >60 | 14 | 3.53 | Enterprise management personnel | 13 | 3.28 | ||

| Monthly income (CNY) | <1000 | 35 | 8.84 | Temporary unemployed | 68 | 17.17 | |

| 1001–4000 | 150 | 37.88 | Student | 70 | 17.68 | ||

| 4001–7000 | 185 | 46.72 | Civil servant/public institution (including teachers) | 119 | 30.05 | ||

| 7001–10,000 | 16 | 4.04 | Professional and technical personnel | 19 | 4.80 | ||

| >10,000 | 10 | 2.52 |

| Index | Variable | Items | Factor Loading | Eigenvalue | Variance Explained (%) | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Travel experience quality | Immersion | Playing in the scenic spot frees me from reality and helps me truly enjoy myself. | 0.932 | 7.216 | 40.932 | 0.923 |

| When I was traveling in the scenic spot, I became so immersed that I forgot everything else. | 0.906 | |||||

| Playing in the scenic spot makes me feel like I’m in another world. | 0.863 | |||||

| When I was playing in the scenic spot, I forgot that time was passing by. | 0.851 | |||||

| Surprise | There are some unexpected and unique attractions in the scenic spot. | 0.853 | 6.341 | 42.003 | 0.856 | |

| The service in the scenic spot makes me feel special and valuable. | 0.802 | |||||

| The service of the scenic spot is consistent and reliable. | 0.761 | |||||

| Participation | When traveling in scenic areas, I want to experience as many facilities as possible. | 0.811 | 5.309 | 55.778 | 0.892 | |

| I participated in the activities provided by the scenic spot. | 0.702 | |||||

| I want to become a member of the scenic spot and enjoy benefits. | 0.763 | |||||

| Fun | I had a great time playing in the scenic spot. | 0.782 | 3.288 | 62.056 | 0.877 | |

| I feel very excited while playing in the scenic spot. | 0.711 | |||||

| I really like this scenic spot. | 0.624 | |||||

| Education | Visiting this scenic spot makes me want to learn more about environmental protection knowledge. | 0.709 | 1.245 | 72.109 | 0.819 | |

| Visiting this scenic spot has made me more concerned about environmental issues. | 0.637 | |||||

| Visiting this scenic spot has expanded my understanding of nature. | 0.523 | |||||

| Variance explained (%) = 72.109, KMO = 0.902, Bartlett (df = 11.6, p = 0.000) | ||||||

| Place attachment | Place dependence | Compared to other scenic spots, I prefer this place. | 0.802 | 4.397 | 51.702 | 0.793 |

| Compared to other scenic spots, this scenic spot can better meet my touristic needs. | 0.729 | |||||

| This scenic spot has given me a sense of satisfaction that other scenic spots do not have. | 0.587 | |||||

| Place identity | This scenic spot is very special to me. | 0.741 | 1.275 | 62.385 | 0.802 | |

| I have a strong sense of identification with this scenic spot. | 0.624 | |||||

| I really enjoy playing in this scenic spot. | 0.595 | |||||

| Variance explained (%) = 62.385, KMO = 0.882, Bartlett (df = 32, p = 0.000) | ||||||

| Pro-environmental behavior | Pro-environmental behavior | I won’t litter while traveling. | 0.842 | 2.973 | 60.274 | 0.817 |

| I abide by the regulations of the scenic spot, not picking flowers or stepping on grass. | 0.741 | |||||

| I will remind fellow travelers not to damage the environment. | 0.736 | |||||

| When I see garbage on the ground during sightseeing, I will pick it up. | 0.711 | |||||

| I actively learn about environmental protection related knowledge. | 0.667 | |||||

| Variance explained (%) = 60.274, KMO = 0.809, Bartlett (df = 14, p = 0.000) | ||||||

| Variable | Items | Factor Loading | AVE | CR | KMO | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall scale | - | - | - | 0.945 | 0.921 | |

| Immersion | Playing in the scenic spot frees me from reality and helps me truly enjoy myself. | 0.823 | 0.632 | 0.839 | 0.863 | 0.901 |

| When I was traveling in the scenic spot, I became so immersed that I forgot everything else. | 0.719 | |||||

| Playing in the scenic spot makes me feel like I’m in another world. | 0.641 | |||||

| When I was playing in the scenic spot, I forgot that time was passing by. | 0.627 | |||||

| Surprise | There are some unexpected and unique attractions in the scenic spot. | 0.830 | 0.613 | 0.811 | 0.856 | 0.867 |

| The service in the scenic spot makes me feel special and valuable. | 0.756 | |||||

| The service of the scenic spot is consistent and reliable. | 0.589 | |||||

| Participation | When traveling in scenic areas, I want to experience as many facilities as possible. | 0.771 | 0.588 | 0.809 | 0.851 | 0.843 |

| I participated in the activities provided by the scenic spot. | 0.654 | |||||

| I want to become a member of the scenic spot and enjoy benefits. | 0.624 | |||||

| Fun | I had a great time playing in the scenic spot. | 0.787 | 0.562 | 0.799 | 0.822 | 0.837 |

| I feel very excited while playing in the scenic spot. | 0.681 | |||||

| I really like this scenic spot. | 0.665 | |||||

| Education | Visiting this scenic spot makes me want to learn more about environmental protection knowledge. | 0.839 | 0.531 | 0.739 | 0.753 | 0.796 |

| Visiting this scenic spot has made me more concerned about environmental issues. | 0.665 | |||||

| Visiting this scenic spot has expanded my understanding of nature. | 0.564 | |||||

| Place dependence | Compared to other scenic spots, I prefer this place. | 0.798 | 0.641 | 0.854 | 0.868 | 0.874 |

| Compared to other scenic spots, this scenic spot can better meet my tourism needs. | 0.771 | |||||

| This scenic spot has given me a sense of satisfaction that other scenic spots do not have. | 0.607 | |||||

| Place identity | This scenic spot is very special to me. | 0.852 | 0.591 | 0.827 | 0.804 | 0.828 |

| I have a strong sense of identification with this scenic spot. | 0.812 | |||||

| I really enjoy playing in this scenic spot. | 0.707 | |||||

| Pro-environmental behavior | I won’t litter while traveling. | 0.842 | 0.547 | 0.772 | 0.784 | 0.796 |

| I abide by the regulations of the scenic spot, not picking flowers or stepping on grass. | 0.741 | |||||

| I will remind fellow travelers not to damage the environment. | 0.736 | |||||

| When I see garbage on the ground during sightseeing, I will pick it up. | 0.711 | |||||

| I actively learn about environmental protection related knowledge. | 0.667 |

| Variable | Immersion | Surprise | Participation | Fun | Education | Place Dependence | Place Identity | Pro-Environmental Behavior |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immersion | 0.687 | |||||||

| Surprise | 0.573 | 0.731 | ||||||

| Participation | 0.528 | 0.215 | 0.763 | |||||

| Fun | 0.592 | 0.427 | 0.588 | 0.735 | ||||

| Education | 0.427 | 0.439 | 0.526 | 0.705 | 0.719 | |||

| Place dependence | 0.711 | 0.522 | 0.409 | 0.272 | 0.525 | 0.793 | ||

| Place identity | 0.544 | 0.478 | 0.376 | 0.396 | 0.568 | 0.517 | 0.713 | |

| Pro-environmental behavior | 0.603 | 0.493 | 0.483 | 0.486 | 0.531 | 0.496 | 0.469 | 0.647 |

| Hypothesis | Paths | β | S.E. | t | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Tourists experience quality→ Place dependence | 0.428 *** | 0.087 | 6.142 | Supported |

| H2 | Tourists experience quality→ Place identity | 0.235 ** | 0.072 | 2.973 | Supported |

| H3 | Place dependence→Pro-environmental behavior | 0.517 *** | 0.091 | 7.381 | Supported |

| H4 | Place identity→Pro-environmental behavior | 0.183 ** | 0.054 | 3.472 | Supported |

| H5 | Tourists experience quality→ Pro-environmental behavior | 0.196 ** | 0.068 | 3.689 | Supported |

| H6 | Place dependence→Place identity | 0.233 ** | 0.070 | 4.015 | Supported |

| Effect | Path | β | 95% Confidenceinterval |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total effect | TEQ→PEB | 0.131 | (0.1078, 0.1521) |

| Direct effect | TEQ→PEB | 0.093 | (0.0685, 0.1186) |

| Indirect effect | TEQ→PD→PEB | 0.037 | (0.0227, 0.0519) |

| TEQ→PI→PEB | 0.129 | (0.1081, 0.1522) | |

| TEQ→PD→PI→PEB | 0.092 | (0.0653, 0.1174) |

| Variable | Value | Frequency | Percent (%) | Variable | Value | Frequency | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 194 | 47.32 | Education | Junior high school or below | 3 | 0.73 |

| Female | 216 | 52.68 | Senior high school | 34 | 8.29 | ||

| Age (years) | <20 | 10 | 2.44 | College degree | 119 | 29.02 | |

| 21–30 | 53 | 12.93 | Bachelor’s degree or above | 254 | 61.96 | ||

| 31–40 | 184 | 44.88 | Occupation | Farmer | 10 | 2.44 | |

| 41–50 | 128 | 31.22 | Individual operator | 66 | 16.10 | ||

| 51–60 | 31 | 7.56 | Service and sales personnel | 92 | 22.44 | ||

| >60 | 4 | 0.97 | Enterprise management personnel | 65 | 15.85 | ||

| Monthly income (CNY) | <1000 | 53 | 12.93 | Temporary unemployed | 31 | 7.56 | |

| 1001–4000 | 177 | 43.17 | Student | 34 | 8.29 | ||

| 4001–7000 | 120 | 29.27 | Civil servant/public institution (including teachers) | 54 | 13.17 | ||

| 7001–10,000 | 31 | 7.56 | Professional and technical personnel | 58 | 14.15 | ||

| >10,000 | 29 | 7.07 |

| Index | Variable | Items | Factor Loading | Eigenvalue | Variance Explained (%) | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Travel experience quality | Immersion | Playing in the scenic spot frees me from reality and helps me truly enjoy myself. | 0.878 | 5.285 | 36.849 | 0.907 |

| When I was traveling in the scenic spot, I became so immersed that I forgot everything else. | 0.822 | |||||

| Playing in the scenic spot makes me feel like I’m in another world. | 0.803 | |||||

| When I was playing in the scenic spot, I forgot that time was passing by. | 0.769 | |||||

| Surprise | There are some unexpected and unique attractions in the scenic spot. | 0.865 | 4.472 | 43.227 | 0.852 | |

| The service in the scenic spot makes me feel special and valuable. | 0.813 | |||||

| The service of the scenic spot is consistent and reliable. | 0.739 | |||||

| Participation | When traveling in scenic areas, I want to experience as many facilities as possible. | 0.804 | 4.119 | 57.688 | 0.878 | |

| I participated in the activities provided by the scenic spot. | 0.793 | |||||

| I want to become a member of the scenic spot and enjoy benefits. | 0.722 | |||||

| Fun | I had a great time playing in the scenic spot. | 0.732 | 3.037 | 68.394 | 0.830 | |

| I feel very excited while playing in the scenic spot. | 0.709 | |||||

| I really like this scenic spot. | 0.637 | |||||

| Education | Visiting this scenic spot makes me want to learn more about environmental protection knowledge. | 0.728 | 1.538 | 75.296 | 0.811 | |

| Visiting this scenic spot has made me more concerned about environmental issues. | 0.703 | |||||

| Visiting this scenic spot has expanded my understanding of nature. | 0.648 | |||||

| Variance explained (%) = 75.296, KMO = 0.931, Bartlett (df = 21, p = 0.000) | ||||||

| Place attachment | Place dependence | Compared to other scenic spots, I prefer this place. | 0.798 | 3.025 | 53.297 | 0.804 |

| Compared to other scenic spots, this scenic spot can better meet my tourism needs. | 0.768 | |||||

| This scenic spot has given me a sense of satisfaction that other scenic spots do not have. | 0.652 | |||||

| Place identity | This scenic spot is very special to me. | 0.733 | 1.337 | 65.032 | 0.793 | |

| I have a strong sense of identification with this scenic spot. | 0.680 | |||||

| I really enjoy playing in this scenic spot. | 0.526 | |||||

| Variance explained (%) = 65.032, KMO = 0.875, Bartlett (df = 25, p = 0.000) | ||||||

| Pro-environmental behavior | Pro-environmental behavior | I won’t litter while traveling. | 0.871 | 2.072 | 63.941 | 0.856 |

| I abide by the regulations of the scenic spot, not picking flowers or stepping on grass. | 0.784 | |||||

| I will remind fellow travelers not to damage the environment. | 0.745 | |||||

| When I see garbage on the ground during sightseeing, I will pick it up. | 0.704 | |||||

| I actively learn about environmental protection related knowledge. | 0.658 | |||||

| Variance explained (%) = 63.941, KMO = 0.832, Bartlett (df = 11, p = 0.000) | ||||||

| Variable | Items | Factor Loading | AVE | CR | KMO | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall scale | - | - | - | 0.839 | 0.919 | |

| Immersion | Playing in the scenic spot frees me from reality and helps me truly enjoy myself. | 0.823 | 0.761 | 0.945 | 0.901 | 0.943 |

| When I was traveling in the scenic spot, I became so immersed that I forgot everything else. | 0.813 | |||||

| Playing in the scenic spot makes me feel like I’m in another world. | 0.783 | |||||

| When I was playing in the scenic spot, I forgot that time was passing by. | 0.738 | |||||

| Surprise | There are some unexpected and unique attractions in the scenic spot. | 0.881 | 0.785 | 0.839 | 0.851 | 0.925 |

| The service in the scenic spot makes me feel special and valuable. | 0.872 | |||||

| The service of the scenic spot is consistent and reliable. | 0.765 | |||||

| Participation | When traveling in scenic areas, I want to experience as many facilities as possible. | 0.863 | 0.750 | 0.904 | 0.843 | 0.928 |

| I participated in the activities provided by the scenic spot. | 0.859 | |||||

| I want to become a member of the scenic spot and enjoy benefits. | 0.721 | |||||

| Fun | I had a great time playing in the scenic spot. | 0.866 | 0.811 | 0.934 | 0.836 | 0.935 |

| I feel very excited while playing in the scenic spot. | 0.853 | |||||

| I really like this scenic spot. | 0.802 | |||||

| Education | Visiting this scenic spot makes me want to learn more about environmental protection knowledge. | 0.877 | 0.833 | 0.918 | 0.742 | 0.921 |

| Visiting this scenic spot has made me more concerned about environmental issues. | 0.842 | |||||

| Visiting this scenic spot has expanded my understanding of nature. | 0.787 | |||||

| Place dependence | Compared to other scenic spots, I prefer this place. | 0.841 | 0.772 | 0.921 | 0.737 | 0.903 |

| Compared to other scenic spots, this scenic spot can better meet my tourism needs. | 0.765 | |||||

| This scenic spot has given me a sense of satisfaction that other scenic spots do not have. | 0.712 | |||||

| Place identity | This scenic spot is very special to me. | 0.883 | 0.834 | 0.903 | 0.729 | 0.889 |

| I have a strong sense of identification with this scenic spot. | 0.825 | |||||

| I really enjoy playing in this scenic spot. | 0.767 | |||||

| Pro-environmental behavior | I won’t litter while traveling. | 0.827 | 0.865 | 0.927 | 0.701 | 0.857 |

| I abide by the regulations of the scenic spot, not picking flowers or stepping on grass. | 0.769 | |||||

| I will remind fellow travelers not to damage the environment. | 0.743 | |||||

| When I see garbage on the ground during sightseeing, I will pick it up. | 0.701 | |||||

| I actively learn about environmental protection related knowledge. | 0.665 |

| Variable | Immersion | Surprise | Participation | Fun | Education | Place Dependence | Place Identity | Pro-Environmental Behavior |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immersion | 0.732 | |||||||

| Surprise | 0.667 | 0.802 | ||||||

| Participation | 0.671 | 0.339 | 0.792 | |||||

| Fun | 0.539 | 0.475 | 0.593 | 0.812 | ||||

| Education | 0.406 | 0.468 | 0.545 | 0.765 | 0.784 | |||

| Place dependence | 0.728 | 0.527 | 0.438 | 0.736 | 0.596 | 0.835 | ||

| Place identity | 0.567 | 0.483 | 0.373 | 0.828 | 0.553 | 0.679 | 0.782 | |

| Pro-environmental behavior | 0.642 | 0.477 | 0.406 | 0.594 | 0.517 | 0.571 | 0.537 | 0.768 |

| Hypothesis | Paths | β | S.E. | t | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Tourists experience quality→ Place dependence | 0.345 ** | 0.072 | 5.978 | Supported |

| H2 | Tourists experience quality→ Place identity | 0.174 * | 0.013 | 2.763 | Supported |

| H3 | Place dependence→Pro-environmental behavior | 0.258 ** | 0.034 | 4.599 | Supported |

| H4 | Place identity→Pro-environmental behavior | 0.216 ** | 0.026 | 4.527 | Supported |

| H5 | Tourists experience quality→ Pro-environmental behavior | 0.542 *** | 0.091 | 7.428 | Supported |

| H6 | Place dependence→Place identity | 0.257 ** | 0.031 | 4.015 | Supported |

| Effect | Path | β | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total effect | TEQ→PEB | 0.079 | (0.0508, 0.1021) |

| Direct effect | TEQ→PEB | 0.043 | (0.0203, 0.0692) |

| Indirect effect | TEQ→PD→PEB | 0.036 | (0.0211, 0.0511) |

| TEQ→PI→PEB | 0.044 | (0.0127, 0.0634) | |

| TEQ→PD→PI→PEB | 0.041 | (0.0269, 0.0581) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, J.; Jin, L.; Pan, X.; Wang, Y. Pro-Environmental Behavior of Tourists in Ecotourism Scenic Spots: The Promoting Role of Tourist Experience Quality in Place Attachment. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8984. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16208984

Zhang J, Jin L, Pan X, Wang Y. Pro-Environmental Behavior of Tourists in Ecotourism Scenic Spots: The Promoting Role of Tourist Experience Quality in Place Attachment. Sustainability. 2024; 16(20):8984. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16208984

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Jiantao, Li Jin, Xinning Pan, and Yang Wang. 2024. "Pro-Environmental Behavior of Tourists in Ecotourism Scenic Spots: The Promoting Role of Tourist Experience Quality in Place Attachment" Sustainability 16, no. 20: 8984. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16208984

APA StyleZhang, J., Jin, L., Pan, X., & Wang, Y. (2024). Pro-Environmental Behavior of Tourists in Ecotourism Scenic Spots: The Promoting Role of Tourist Experience Quality in Place Attachment. Sustainability, 16(20), 8984. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16208984