Appraising Education 4.0 in Nigeria’s Higher Education Institutions: A Case Study of Built Environment Programmes

Abstract

1. Introduction

- i.

- To appraise the current state of Education 4.0 in Nigeria’s BEPs.

- ii.

- To investigate the hindrances to implementing Education 4.0 in Nigeria’s BEPs.

- iii.

- To proffer feasible measures to improve Education 4.0 implementation in Nigeria’s BEPs.

2. Review of the Literature

2.1. Background on Education 4.0

2.2. Built Environment Education (BEE) Background

3. Theoretical Framework

4. Research Method

5. Findings and Discussion

5.1. Theme One: Current State of Education 4.0 in Nigeria’s BEPs

“… I doubt our decision-making stakeholders, such as the policymakers and political leaders, are ready for Education 4.0. My overview assessment shows that Nigeria is still struggling between Education 1.0 and 2.0 but is far from Education 3.0. Developed countries and some developing countries are implementing Education 4.0 in response to the needs of Industry 4.0. Do we have the capacity for Industry 4.0?…”

“…besides few private HEIs we (Nigerian public HEIs) are backward regarding implementing Education 4.0 if the truth must be told. Many factors such as poor budget and prolonged strike have compounded the impeding hindrances to implementing Education 4.0…” said Participant 14.

5.2. Theme Two: Hindrances

“… we have a long way to go regarding digitalising education (Education 4.0). I agree that Education 4.0 is beyond digitalisation, but do we have the capacity with the insufficient budget for education, incessant strikes, and insufficient and delipidated ICT facilities? I doubt. This is my opinion…” said Participant P4.

“… many Nigeria’s HEIs face a chronic shortage of students’ accommodation and classrooms… There are cases where students struggle to get seats for lectures. It is beyond my control…”

5.3. Theme Three: Ways to Improve Implementing Education 4.0 in Nigeria’s BEPs

“… Nigeria is far behind regarding Education 4.0 implementation and hoping the incoming government will have the political will to address some of the critical issues… I’m aware that many polytechnics could not function during the COVID crisis though the universities were on strike while elementary schools in our neighbouring countries were in operation because the infrastructure and capacity were there…”

“… ICT elements in Education 4.0 are tools and platforms and technology-based. The latter provides technology-based measures while the former combines various technologies for management and educational purposes…”

“… collaboration should integrate inputs from the industry regarding how Education 4.0 can be incorporated and integrated into the curriculum of Nigeria’s HEIs to enhance transformative competencies, technological advancement, and innovative pedagogical procedures…”

6. This Study’s Implications

7. Limitations and Areas for Further Research

8. Conclusions and Recommendations

- i.

- This study recommends that besides addressing the issues of incessant striking actions emanating from unresolved managerial disputes in Nigeria’s HEIs, especially in public HEIs, the low education budget and the issue of inadequate funding need to be addressed in line with the UNESCO recommendation. This, by extension, will facilitate the achievement of Sustainable Development Goal 4. This will improve access to ICT infrastructure and upskill and reskill academic staffers regarding integrating emerging technologies, such as IoT, machine learning, and cloud computing, in teaching and learning.

- ii.

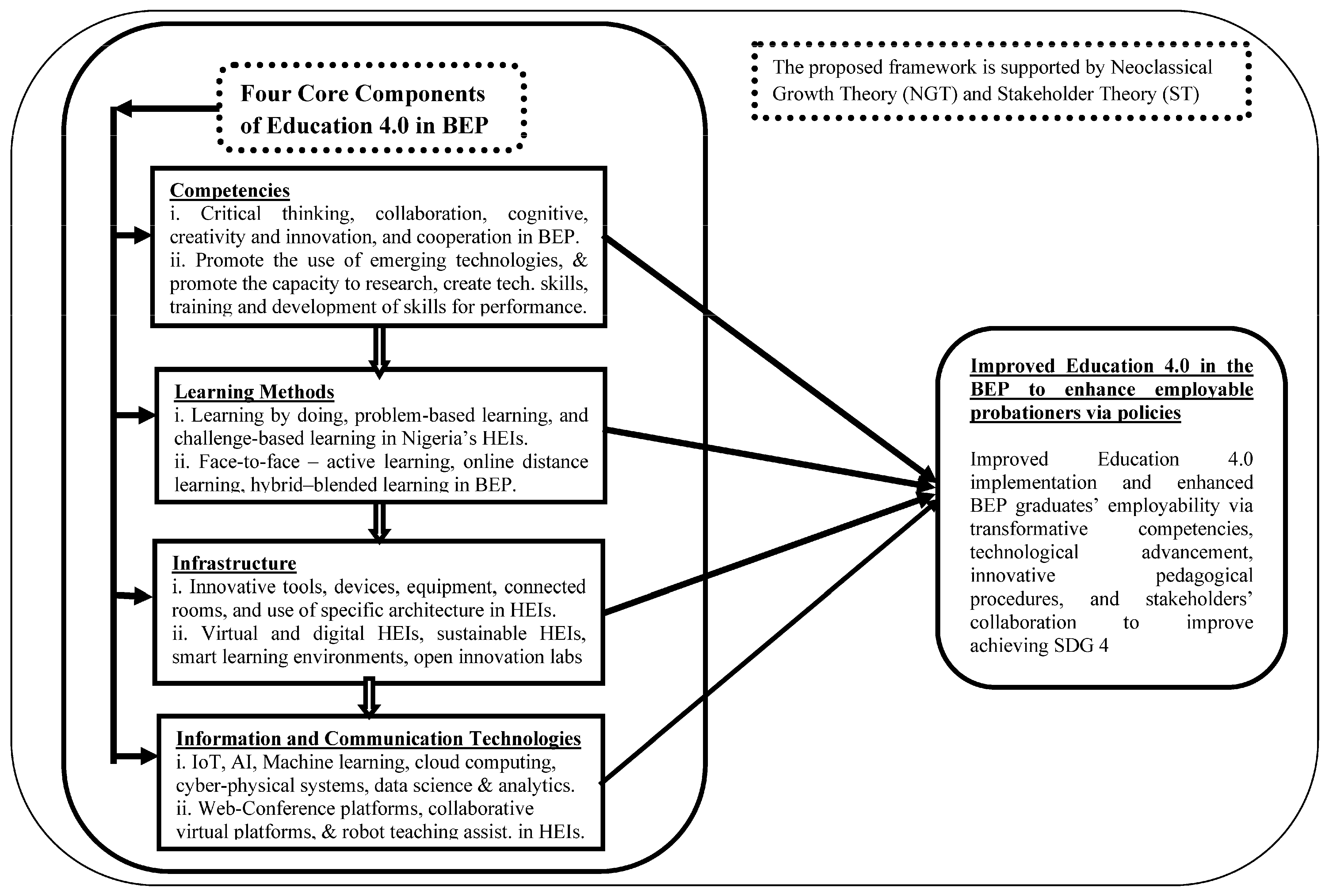

- This study suggests developing an all-inclusive framework to promote employability, industry-based collaboration, and the implementation of Education 4.0 to enhance the vision of Industry 4.0, as presented in Figure 2. This collaboration should integrate inputs from the industry regarding how Education 4.0 can be incorporated into Nigeria’s HEIs to enhance transformative competencies, technological advancement, and innovative paedagogical procedures and, by extension, improve the achievement of Sustainable Development Goal 4. Life-long learning and flexible production lines must also be emphasised. The key stakeholders, especially the government via regulatory agencies and the relevant professional bodies, have a part to play in implementing Education 4.0 in BEPs via curriculum updating.

- iii.

- Also, this study recommends that besides Education 4.0 as a means to generate a sustainable environment for future staffers’ education and align with Industry 4.0 regarding creativity and innovation, students and academic staffers in BEPs should embrace the Education 4.0 concept as a platform to acquire skills and competencies that technologies may not be able to offer in the future via problem-based learning and blended learning in BEPs.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ebekozien, A.; Samsurijan, S.M. Concession of public infrastructure: Pitfalls and solutions from construction consultants’ perspective. Asian J. Civ. Eng. 2022, 23, 753–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebekozien, A.; Aigbavboa, C.; Thwala, W.D.; Aigbedion, M.; Ogbaini, I.F. An appraisal of generic skills for Nigerian built environment professionals in workplace: The unexplored approach. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2021, 21, 1841–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebekozien, A.; Aigbavboa, C.; Nwaole, C.N.A.; Dako, O.; Awo-Osagie, I.A. Quantity surveyor’s ethical responsiveness on construction projects: Issues and solutions. Int. J. Build. Pathol. Adapt. 2021, 41, 1049–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum. Defining Education 4.0: A Taxonomy for the Future of Learning. 2023. White Paper January. Available online: https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Defining_Education_4.0_2023.pdf (accessed on 27 August 2024).

- Savage, S.; Davis, R.; Miller, E. Professional education in built environment and design. Aust. Learn. Teach. Counc. 2010, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Ebekozien, A.; Aigbavboa, C.; Aliu, J. Built environment academics for 21st century world of teaching: Stakeholders’ perspective. Int. J. Build. Pathol. Adapt. 2022, 41, 119–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, J.; Lopez, C.S.; Navarro-Tuch, S.A.; Bustamante-Bello Martin, R.; Molina, J.M.; Molina, A. Open Innovation Laboratories as Enabling Resources to Reach the Vision of Education 4.0. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Engineering, Technology and Innovation (ICE/ITMC), Valbonne, France, 17–19 June 2019; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Androsch, F.M.; Redl, U. How Megatrends Drive Innovation. BHM Berg-Und Huttenmann. Monatshefte 2019, 164, 479–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legg-Jack, D.W. Digitalisation of teaching and learning in Nigeria amid COVID-19 pandemic: Challenges and lessons for education 4.0 and 4IR. Ponte Int. J. Sci. Res. 2021, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suvin, C. Why Should Higher Education Institutions Focus on Education 4.0? 30 September 2020. Available online: https://www.creatrixcampus.com/blog/Education-4.0 (accessed on 20 January 2022).

- Hariharasudan, A.; Kot, S. A scoping review on Digital English and Education 4.0 for Industry 4.0. Soc. Sci. 2018, 7, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebekozien, A.; Aigbavboa, C.; Aliu, J.; Thwala, W.D. Generic skills of future built environment practitioners in South Africa: Unexplored mechanism via students’ perception. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2022, 22, 561–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliu, J.; Aigbavboa, C.O. Employers’ perception of employability skills among built-environment graduates. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2020, 18, 847–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oviawe, I.J.; Uwameiye, R. Approaches for developing generic skills in building technology graduates for global competitiveness. J. Vocat. Educ. Stud. 2020, 3, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stehle, S.M.; Peters-Burton, E.E. Developing student 21st Century skills in selected exemplary inclusive STEM high schools. Int. J. STEM Educ. 2019, 6, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selamat, A.; Alias, R.A.; Hikmi, S.N.; Puteh, M.; Tapsi, S.M. Higher education 4.0: Current status and readiness in meeting the fourth industrial revolution challenges. Redesigning High. Educ. Towards Ind. 2017, 4, 23–24. [Google Scholar]

- Elkington, S.; Bligh, B. Future Learning Spaces: Space, Technology and Pedagogy. Advance HE. 2019. Available online: https://research.tees.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/6770557/Future_Learning_Spaces.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2022).

- Olanrewaju, B.U.; Afolabi, J.A. Digitising education in Nigeria: Lessons from COVID-19. Int. J. Technol. Enhanc. Learn. 2022, 14, 402–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odegbesan, O.A.; Ayo, C.; Oni, A.A.; Tomilayo, F.A.; Gift, O.C.; Nnaemeka, E.U. The prospects of adopting e-learning in the Nigerian education system: A case study of Covenant University. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1299, 012058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adepoju, O.O.; Aigbavboa, C.O. Implementation of construction 4.0 in Nigeria: Evaluating the opportunities and threats on the workforce. Acad. J. Interdiscip. Stud. 2020, 9, 254–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moja, T. Nigeria education sector analysis: An analytical synthesis of performance and main issues. World Bank Rep. 2000, 3, 46–56. [Google Scholar]

- Ajuluchukwu, E.N. Assessment of Minimum Academic Standards Adopted by Universities in South-East and South-South for Undergraduate Business Education Programmes. Ph.D. Thesis, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka, Nigeria, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hussin, A.A. Education 4.0 made simple: Ideas for teaching. Int. J. Educ. Lit. Stud. 2018, 6, 92–98. [Google Scholar]

- PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC). AI Will Create as Many Jobs as It Displaces by Boosting Economic Growth. 2018. Available online: https://www.pwc.co.uk/press-room/press-releases/AI-will-create-as-many-jobs-as-it-displaces-by-boosting-economic-growth.html (accessed on 27 August 2024).

- Lloyds Bank. UK Consumer Digital Index 2019: The UK’s Largest Study of Transaction, Behavioural and Attitudinal Research. 2019. Available online: https://www.lloydsbank.com/assets/media/pdfs/banking_with_us/whats-happening/lb-consumer-digital-index-2019-report.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2022).

- Microsoft. Microsoft Report. 2020. Available online: https://www.microsoft.com/investor/reports/ar20/index.html (accessed on 20 May 2022).

- Lasi, H.; Fettke, P.; Kemper, H.-G.; Feld, T.; Hoffmann, M. Industry 4.0. Bus. Inf. Syst. Eng. 2014, 6, 239–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, K.; Groß, K.; Vossen, R.; Richert, A.; Jeschke, S. Preparing for Industry 4.0—Collaborative virtual learning environments in engineering education. In Engineering Education 4.0: Excellent Teaching and Learning in Engineering Sciences; Frerich, S., Meisen, T., Richert, A., Petermann, M., Jeschke, S., Wilkesmann, U., Tekkaya, A.E., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 477–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonfield, A.C.; Salter, M.; Longmuir, A.; Benson, M.; Adachi, C. Transformation or evolution?: Education 4.0, teaching and learning in the digital age. High. Educ. Pedagog. 2020, 5, 223–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellahi, M.R.; Khan, A.U.M.; Adeel Shah, A. Redesigning Curriculum in line with Industry 4.0. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2019, 151, 699–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HolonIQ. Education in 2030—The $10 Trillion Dollar Question. 2019. Available online: https://www.holoniq.com/2030 (accessed on 20 May 2022).

- Salmon, G. May the Fourth Be with You: Creating Education 4.0. J. Learn. Dev. 2019, 6, 95–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Economic and Social Council, United Nations. 2022. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/29858SG_SDG_Progress_Report_2022.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2023).

- Million, A.; Parnell, R.; Coelen, T. Policy, practice and research in built environment education. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng.-Urban Des. Plan. 2018, 171, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamalipour, H.; Peimani, N. Towards an informal turn in the built environment education: Informality and urban design pedagogy. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bybee, R.W. The Case for STEM Education; NSTA Press: Arlington, TX, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Partnership for 21st Century Learning. Framework for 21st Century Learning. 2016. Available online: https://www.battelleforkids.org/insights/p21-resources/ (accessed on 20 May 2022).

- Asiyai, R.I. Improving quality higher education in Nigeria: The roles of stakeholders. Int. J. High. Educ. 2015, 4, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umeokafor, N.; Windapo, A. Challenges to and opportunities for establishing a qualitative approach to built environment research in higher education institutions. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2018, 16, 557–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TETFund. TETFund Act 2011; TETFund: Abuja, Nigeria, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- JISC. Preparing for Education 4.0 Times Higher Education (THE). 30 November 2018. Available online: https://www.timeshighereducation.com/hub/jisc/p/preparing-education-40 (accessed on 20 May 2022).

- JISC. NATALIE_4.0 Demo. 2019. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=11&v=gs3wMix-egA&feature=emb_logoeducation-40 (accessed on 20 May 2022).

- National Bureau of Economic Research. Trevor Swan and the Neoclassical Growth Model (n.d.). Abstract & Pages 1 & 11. Available online: https://www.nber.org/papers/w13950.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- Jia, W.; Collins, A.; Liu, W. Digitalisation and economic growth in the new classical and new structural economics perspectives. DESD 2023, 1, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, N.; Zou, P.X.W.; Griffin, M.A.; Wang, X.; Zhong, R. Towards integrating construction risk management and stakeholder management: A systematic literature review and future research agendas. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2018, 36, 701–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kujala, J.; Sachs, S.; Leinonen, H.; Heikkinen, A.; Laude, D. Stakeholder engagement: Past, present, and future. Bus. Soc. 2022, 61, 1136–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Pitman: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Project Management Institute. Project Management Body of Knowledge; PMI: Newtown Square, PA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Shen, Q.; Ho, M. An overview of previous studies in stakeholder management and its implications for the construction industry. J. Facil. Manag. 2009, 7, 159–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strand, R.; Freeman, R.E. Scandinavian cooperative advantage: The theory and practice of stakeholder engagement in Scandinavia. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 127, 65–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). The Future of Education and Skills 2030, Conceptual Learning Framework: Skills for 2030. Expert Consultation. 2019. Available online: http://t4.oecd.org/education/2030-project/ (accessed on 20 May 2022).

- Economic Themes. Technological Changes in Economic Growth Theory: Neoclassical, Endogenous, and Evolutionary-Institutional Approach. 2016, pp. 177–178. Available online: https://content.sciendo.com/view/journals/ethemes/54/2/article-p177.xml (accessed on 27 August 2024).

- Becerik-Gerber, B.; Rice, S. The perceived value of building information modelling in the US building industry. J. Inf. Technol. Constr. 2010, 15, 185–201. [Google Scholar]

- Ebekozien, A.; Aigbavboa, C. Improving quantity surveying education through continually updating curriculum digitalisation to meet industry requirements. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2023, 22, 1523–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, W.J.; Creswell, D.J. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 5th ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jaafar, M.; Ebekozien, A.; Mohamad, D. Community participation in environmental sustainability: A case study of proposed Penang Hill Biosphere Reserve, Malaysia. J. Facil. Manag. 2021, 19, 527–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldana, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers, 3rd ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, F.S.; Ebekozien, A.; Khan, P. Appraising fourth industrial revolution technologies’ role in the construction sector: How prepared is the construction consultants? Facilities 2022, 40, 515–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plano-Clark, V.L.; Creswell, J.W. Understanding Research: A Consumer Guide, 2nd ed.; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 5th ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Akinyemi, I.A.; Amaechi, L.I.; Etoh, L.C. Digitalisation of education in Nigerian secondary schools: Benefits & challenges. JEHR J. Educ. Humanit. Res. Univ. Balochistan 2022, 13, 34–42. [Google Scholar]

- Okure, D.U. Impacts of organisational culture on academic efficiency and productivity in selected private universities in the Niger delta region of Nigeria. High. Educ. Q. 2023, 77, 298–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olafare, F.O.; Adeyanju, L.O.; Fakorede, S.O.A. Colleges of education lecturers attitude towards the use of information and communication technology in Nigeria. Malays. Online J. Educ. Sci. 2018, 5, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Tolu-Kolawole, D. AUSS Embarks on 16 Strikes in 23 Years, FG, Lecturers Disagree over 13-Year MOU, Punch. May 2022. Available online: https://punchng.com/asuu-embarks-on-16-strikes-in-23-years-fg-lecturers-disagree-over-13-year-mou/ (accessed on 20 May 2023).

- Dawson, S.; Osborne, A. Re-shaping built environment higher education: The impact of degree apprenticeships in England. Int. J. Constr. Educ. Res. 2020, 16, 102–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oesterreich, D.T.; Teuteberg, F. Understanding the implications of digitalisation and automation in the context of Industry 4.0: A triangulation approach and elements of a research agenda for the construction industry. Comput. Ind. 2016, 83, 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohlenz, P.; Felix, A.; Berndt, S.; Seyfried, M. How do students deal with forced digitalisation in teaching and learning? Implications for quality assurance. Qual. Assur. Educ. 2023, 31, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Challenge | Emergent Technologies |

|---|---|

| Student experience | AI, chatbots, learning analytics |

| Skills gap | Immersive technologies, simulations, AI |

| Data and Estates | Big data, robotics, smart library management |

| Innovations in teaching and learning | AI, personalised learning environments, chatbots, immersive technologies |

| Metrics | Data analytics |

| Open science and research infrastructure | AI, machine learning, robotics, automated experimentation, knowledge discovery, connected research equipment |

| Cyber security | IoT (security risks) |

| Participant | Rank/Firm | Years of Experience | Geopolitical Zone/Location and Participant Code | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SS | SW | SE | NW | NC | NE | ||||

| Built Environment Professionals in Academics | Not below (NB) Lecturer 1 rank (State and Federal) | NB 10 years | 1–2 | 3–6 | 7–8 | 9–11 | 12–14 | 15 | 15 |

| Built Environment Professionals in Practice | Directors, Managing Partners, Partners | NB 25 years | 16–17 | 18–21 | 22 | 23–24 | 25–29 | 30 | 15 |

| Professional Elected/Appointed Officials | Past and serving Exco National Members | NB 28 years | - | - | - | - | 31–34 | - | 4 |

| HEI Regulatory Agencies | NB Senior Staff | NB 15 years | - | - | - | 35 | 36 | - | 2 |

| Property Developers | Directors/Operational Managers/CEO, Managing Directors | NB 27 years | 37 | 38 | - | - | 39–40 | - | 4 |

| Total | 40 | ||||||||

| Method | Assessment Strategies | Phase of Research, Including Techniques Used |

|---|---|---|

| Reliability | Consistent structure of interview. | Data collection |

| Consistent interviewer (lead investigator). | Data collection | |

| Validity | Utilisation of recognised strategy. | Data collection |

| Semi-structured virtual interview. | Data collection | |

| Credibility | Pattern matching using the theme method. | Data analysis |

| Dependability | Developing interview guidelines. | Research design |

| Ease of independent review of data collection trial. | Research design | |

| Data collection/analysis |

| S/Nos | Hindrances That Emerged | Categorisation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Govt/Regulatory Agency-Related | HEI Management-Related | BEP Student-Related | ||

| 1 | Lack of access to IT infrastructure | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 2 | Inadequate funding: the Education 4.0 project is capital-intensive | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 3 | Lax government and management lead/direction | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 4 | Cost of training for staff/lecturers (“train the trainers” scheme) | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 5 | Diverse access to technology skills acquisition | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 6 | Poor/weak internet access/data | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 7 | Lax accreditation standards and requirements as a framework for Education 4.0 implementation in HEIs | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 8 | Erratic electric power supply | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 9 | Lax collaboration between industry professionals and the academic world regarding Education 4.0 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 10 | Lack of digital literacy/competence skills | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 11 | High security risks regarding data protection and cyber issues | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 12 | Academic staff and students’ resistance/experience | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 13 | Unequal access to educational opportunities | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 14 | Low awareness of the relevance of Education 4.0 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 15 | Inadequate investment in research and development | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 16 | Unclear benefits and gains to many stakeholders | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 17 | Absence of enabling environment (frequent academic labour crises) | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 18 | Absence of political will | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Total | 18 | 18 | 7 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ebekozien, A.; Hafez, M.A.; Aigbavboa, C.; Samsurijan, M.S.; Al-Hasan, A.Z.; Nwaole, A.N.C. Appraising Education 4.0 in Nigeria’s Higher Education Institutions: A Case Study of Built Environment Programmes. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8878. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16208878

Ebekozien A, Hafez MA, Aigbavboa C, Samsurijan MS, Al-Hasan AZ, Nwaole ANC. Appraising Education 4.0 in Nigeria’s Higher Education Institutions: A Case Study of Built Environment Programmes. Sustainability. 2024; 16(20):8878. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16208878

Chicago/Turabian StyleEbekozien, Andrew, Mohamed Ahmed Hafez, Clinton Aigbavboa, Mohamad Shaharudin Samsurijan, Abubakar Zakariyya Al-Hasan, and Angeline Ngozika Chibuike Nwaole. 2024. "Appraising Education 4.0 in Nigeria’s Higher Education Institutions: A Case Study of Built Environment Programmes" Sustainability 16, no. 20: 8878. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16208878

APA StyleEbekozien, A., Hafez, M. A., Aigbavboa, C., Samsurijan, M. S., Al-Hasan, A. Z., & Nwaole, A. N. C. (2024). Appraising Education 4.0 in Nigeria’s Higher Education Institutions: A Case Study of Built Environment Programmes. Sustainability, 16(20), 8878. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16208878