Exploring Portuguese Consumers’ Behavior Regarding Sustainable Wine: An Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Key Concepts and Literature Review

2.1. Sustainability

2.2. Sustainable Wine

2.3. Consumers’ Perceptions of Sustainable Wine

2.4. Research on Sustainable Wine

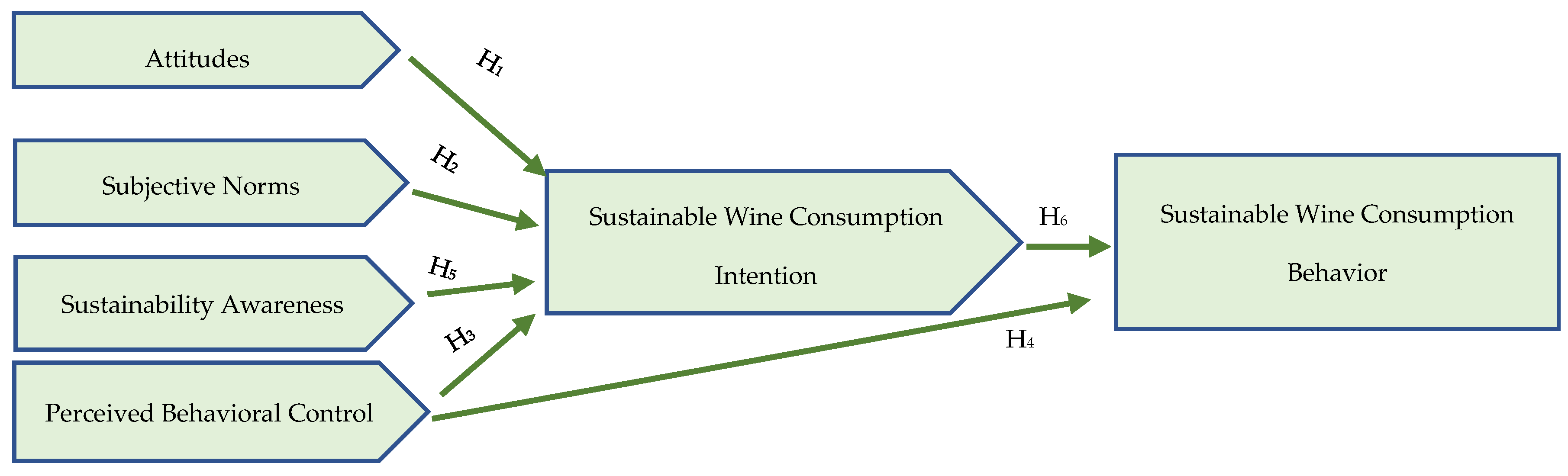

3. Theoretical Framework and Research Hypotheses

3.1. Theory of Planned Behavior

3.2. Research Hypotheses

4. Materials and Methodology

4.1. Questionnaire Design

- (i)

- It was too long, with too many questions, and it was observed that, after a while, respondents began to feel tired and bored;

- (ii)

- Some questions were confusing and unclear;

- (iii)

- The questions were asked without any distinction between those who consume and those who buy, but those who consume are not always those who buy the wine.

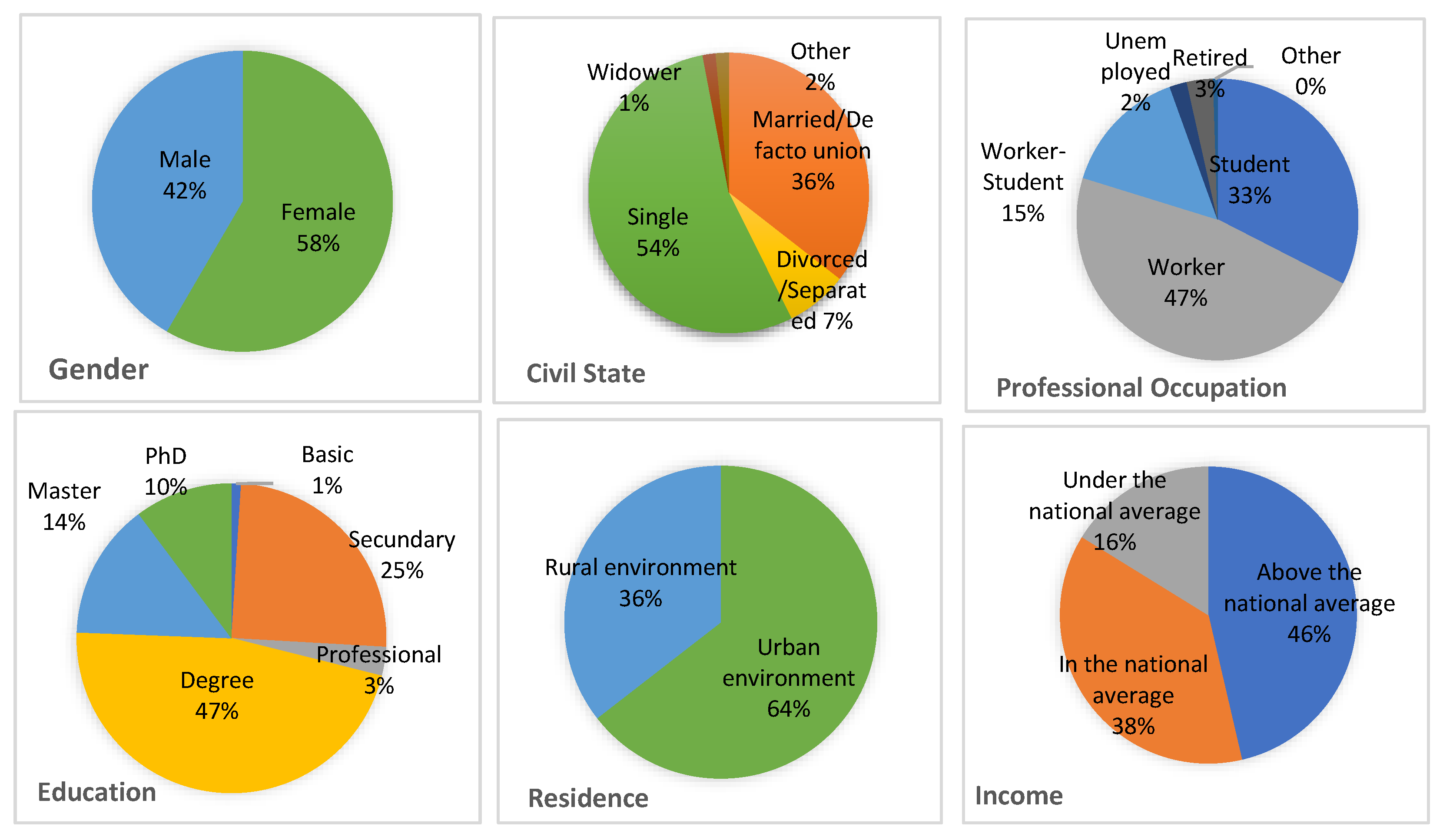

4.2. Sample Socioeconomic Description

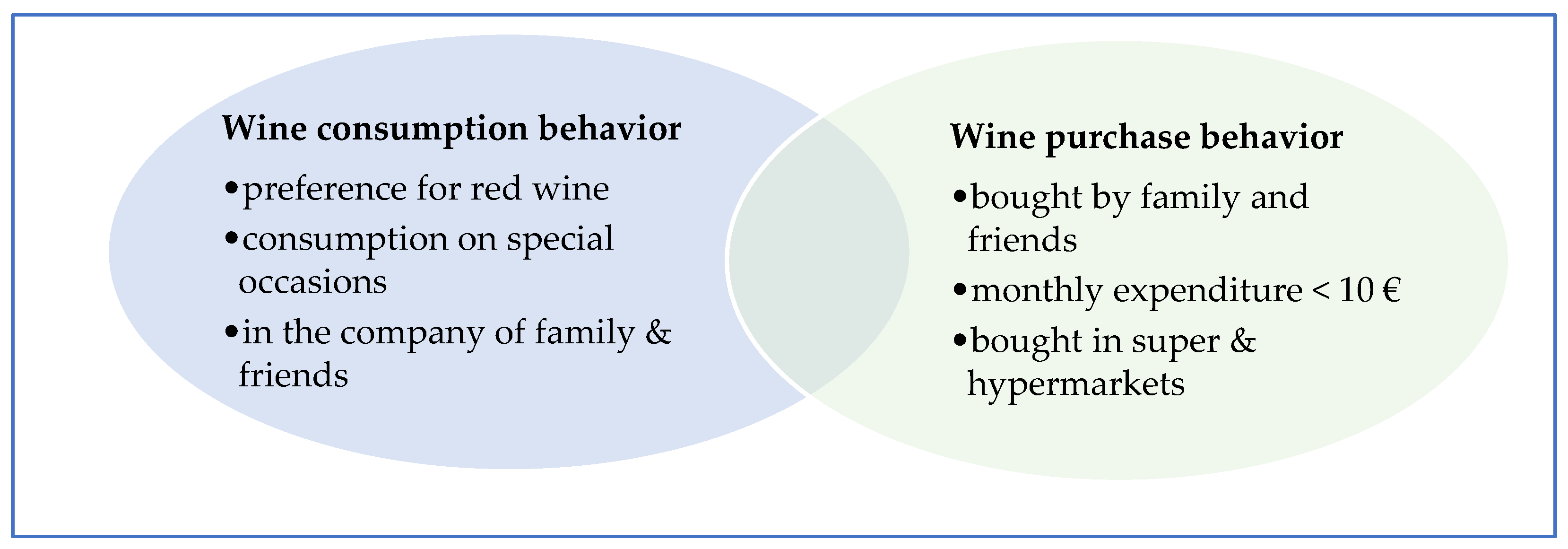

4.3. Sample Wine Consumption and Purchase Description

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Reliability and Validity

5.2. Structural Model Analysis

5.3. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO. The State of Food and Agriculture 2023. In Revealing the True Cost of Food to Transform Agrifood Systems; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Grote, U.; Neubacher, F.; Rahut, D.B.; Do, M.H.; Paudel, G.P. Security risks from climate change and environmental degradation: Implications for sustainable land use transformation in the Global South. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2023, 63, 101322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, R.d.; Bragança, L.; da Silva, M.V.; Oliveira, R.S. Challenges and Solutions for Sustainable Food Systems: The Potential of Home Hydroponics. Sustainability 2024, 16, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsellino, V.; Schimmenti, E.; El Bilali, H. Agri-Food Markets towards Sustainable Patterns. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çakmakçı, R.; Salık, M.A.; Çakmakçı, S. Assessment and Principles of Environmentally Sustainable Food and Agriculture Systems. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Díaz, F.J.; Belmonte-Ureña, L.J.; López-Serrano, M.J.; Camacho-Ferre, F. Assessment of the sustainability of the European agri-food sector in the context of the circular economy. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2023, 40, 398–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OIV. State of the World Vine and Wine Sector 2021: April 2022; International Organisation of Vine and Wine: Paris, France, 2022; Available online: https://www.oiv.int (accessed on 2 September 2024).

- OIV. World Wine Production Outlook: OIV First Estimates. 2022. Available online: https://www.oiv.int/press/severe-drought-and-extreme-heat-pose-new-threat-wine-production (accessed on 31 October 2022).

- Chen, L.-C.; Kingsbury, A. Development of wine industries in the New-New World: Case studies of wine regions in Taiwan and Japan. J. Rural. Stud. 2019, 72, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes-Fernández, R.; Martínez-Falcó, J.; Sánchez-García, E.; Marco-Lajara, B. Does Ecological Agriculture Moderate the Relationship between Wine Tourism and Economic Performance? A Structural Equation Analysis Applied to the Ribera del Duero Wine Context. Agriculture 2022, 12, 2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L.; Santos, R.; Sempiterno, M.; Costa, R.L.d.; Dias, Á.; António, N. Pereira Problem Solving: Business Research Methodology to Explore Open Innovation. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, V.; Dias, A.; Ramos, P.; Madeira, A.; Sousa, B. Mapping the wine visit experience for tourist excitement and cultural experience. Ann. Leis. Res. 2021, 26, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springmann, M.; Clark, M.; Mason-D’Croz, D.; Wiebe, K.; Bodirsky, B.L.; Lassaletta, L.; de Vries, W.; Vermeulen, S.J.; Herrero, M.; Carlson, K.M.; et al. Options for keeping the food system within environmental limits. Nature 2018, 562, 519–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitriu, G.D.; Teodosiu, C.; Cotea, V.V. Management of Pesticides from Vineyard to Wines: Focus on Wine Safety and Pesticides Removal by Emerging Technologies; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2021; pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merli, R.; Preziosi, M.; Acampora, A. Sustainability experiences in the wine sector: Toward the development of an international indicators system. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 3791–3805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, A.; Sousa, B.; Santos, V.; Ramos, P.; Madeira, A. Wine Tourism and Sustainability Awareness: A Consumer Behavior Perspective. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigo, A.; Fragoso, R.; Marta-Costa, A. Sustainability awareness in the Portuguese wine industry: A grounded theory approach. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2022, 20, 1437–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, A.L.; Fernão-Pires, M.J.; Bianchi-de-Aguiar, F. Portuguese vines and wines: Heritage, quality symbol, tourism assets. Ciência Téc. Vitiv. 2018, 33, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swiatkiewicz, O. The Wine Sector Management in Portugal: An Overview on Its Three-Dimensional Sustainability. Manag. Sustain. Dev. Sibiu 2021, 13, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OIV. State of the World Vine and Wine Sector in 2023: April 2024; International Organisation of Vine and Wine: Paris, France, 2024; Available online: https://www.oiv.int (accessed on 2 September 2024).

- Sellers-Rubio, R.; Nicolau-Gonzalbez, J.L. Estimating the willingness to pay for a sustainable wine using a heckit model. Wine Econ. Policy 2016, 5, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäufele, I.; Hamm, U. Organic wine purchase behaviour in Germany: Exploring the attitude-behaviour-gap with data from a household panel. Food Qual. Prefer. 2018, 63, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In Action-Control: From Cognition to Behavior; Kuhl, J., Beckmann, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1985; pp. 11–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, C.; De Feo, G. Life Cycle Assessment Application to the Wine Sector: A Critical Review. Sustainability 2018, 10, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigo, A.; Silva, P. Sustainable Development Directions for Wine Tourism in Douro Wine Region, Portugal. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscovici, D.; Reed, A. Comparing wine sustainability certifications around the world: History, status and opportunity. J. Wine Res. 2018, 29, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgroi, F.; Maenza, L.; Modica, F. Exploring consumer behavior and willingness to pay regarding sustainable wine certification. J. Agric. Food Res. 2023, 14, 100681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WCED. Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- UN. Academic Impact: Sustainability. 2023. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/academic-impact/sustainability (accessed on 3 December 2023).

- Thomas, C.F. Naturalizing Sustainability Discourse: Paradigm, Practices and Pedagogy of Thoreau, Leopold, Carson and Wilson. Ph.D. Thesis, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, USA, 2015. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/79576433.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Hák, T.; Janoušková, S.; Moldan, B. Sustainable development goals: A need for relevant indicators. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 60, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delicado, A.; Domingos, N.; Sousa, L. Introduction. In Changing Societies: Legacies and Challenges. Vol. iii. The Diverse Worlds of Sustainability; Delicado, A., Domingos, N., de Sousa, L., Eds.; Imprensa de Ciências Sociais: Lisbon, Portugal, 2018; pp. 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragão, A. Desenvolvimento Sustentável em tempo de crise e em maré de simplificação. Fundamento e limites da proibição do retrocesso ambiental [Sustainable Development in times of crisis and in tide of simplification. Foundation and limits of prohibition of the environmental setback]. In Estudos em Homenagem ao Prof. Doutor José Joaquim Gomes Canotilho; Coimbra Editora: Coimbra, Portugal, 2012; Volume IV. [Google Scholar]

- Emas, R. The Concept of Sustainable Development: Definition and Defining principles, Brief for GSDR; Global Sustainable Development Report; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, L.F. A Justiça Intergeracional [Intergenerational Justice]. Master’s Thesis, University of Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal, 2016. Volume 523. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10316/31403 (accessed on 2 September 2024).

- Menash, J.; Enu-Kwesi, F. Implications of environmental sanitation management for sustainable livelihoods in the catchment area of Benya Lagoon in Ghana. J. Integr. Environ. Sci. 2019, 16, 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spijkers, O. Intergenerational Equity and the Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiano, A. An Overview on Sustainability in the Wine Production Chain. Beverages 2021, 7, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, C.P.V.; Nodari, E.S. Winemaking, Environmental Impacts and Sustainability: New Pathways from Vineyard to Glass? Historia Ambiental Latinoamericana Y Caribeña (HALAC). Rev. Solcha 2020, 10, 223–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandinelli, R.; Acuti, D.; Fani, V.; Bindi, B.; Aiello, G. Environmental practices in the wine industry: An overview of the Italian market. Br. Food J. 2020, 122, 1625–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacharof, M.P. Grape Winery Waste as Feedstock for Bioconversions: Applying the Biorefinery Concept. Waste Biomass Valorization 2017, 8, 1011–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsato, E.; Zucchinelli, M.; D’Ammaro, D.; Giubilato, E.; Zabeo, A.; Criscione, P.; Pizzol, L.; Cohen, Y.; Tarolli, P.; Lamastra, L.; et al. Use of multiple indicators to compare sustainability performance of organic vs. conventional vineyard management. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 711, 135081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Point, E.; Tyedmers, P.; Naugler, C. Life cycle environmental impacts of wine production and consumption in Nova Scotia, Canada. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 27, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, B.; Dias, A.C.; Machado, M. Life cycle assessment of the supply chain of a Portuguese wine: From viticulture to distribution. Int. J. Life Cycle Ass. 2013, 18, 590–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, S.S. What is sustainability in the wine world? A cross-country analysis of wine sustainability frameworks. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 2301–2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gbejewoh, O.; Keesstra, S.; Blancquaert, E. The 3Ps (Profit, Planet, and People) of Sustainability amidst Climate Change: A South African Grape and Wine Perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellers, R. Would you pay a price premium for a sustainable wine? The voice of the Spanish Consumer. Agric. Agric. Sci. Procedia 2016, 8, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Falcó, J.; Sánchez-García, E.; Marco-Lajara, B.; Georgantzis, N. The interplay between competitive advantage and sustainability in the wine industry: A bibliometric and systematic review. Discov. Sustain. 2024, 5, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montalvo-Falcón, J.V.; Sánchez-García, E.; Marco-Lajara, B.; Martínez-Falcó, J. Sustainability Research in the Wine Industry: A Bibliometric Approach. Agronomy 2023, 13, 871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela, L.; Ortega, R.; Moscovici, D.; Gow, J.; Alonso Ugaglia, A.; Mihailescu, R. Consumer Willingness to Pay for Sustainable Wine—The Chilean Case. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäufele, I.; Hamm, U. Consumers’ perceptions, preferences and willingness-to-pay for wine with sustainability characteristics: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 147, 379–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchio, R.; Annunziata, A.; Dans, E.P.; González, P.A. Drivers of consumer willingness to pay for sustainable wines: Natural, biodynamic, and organic. Org. Agric. 2023, 13, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broccardo, L.; Truant, E.; Dana, L.-P. The sustainability orientation in the wine industry: An analysis based on age as a driver. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 30, 1300–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucca, G.; Smith, D.; Mitry, D.J. Sustainable viticulture and winery practices in California: What is it, and do customers care? Int. J. Wine Res. 2009, 1, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Forbes, S.L.; Cohen, D.A.; Cullen, R.; Wratten, S.D.; Fountain, J. Consumer attitudes regarding environmentally sustainable wine: An exploratory study of the New Zealand marketplace. J. Clean. Prod. 2009, 17, 1195–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleby, C.; Costanigro, M.; Thilmany, D.; Menke, S. Measuring consumer willingness to pay for low-sulfite wine: A conjoint analysis. Am. Assoc. Wine Econ. Work. Pap. Econ. 2012, 117, 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Ginon, E.; Gastòn, A.; Laboissière, L.H.E.S.; Brouard, J.; Issanchou, S.; Deliza, R. Logos indicating environmental sustainability in wine production: An exploratory study on how do Burgundy wine consumers perceive them. Food Res. Int. 2014, 62, 837–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomarici, E.; Vecchio, R. Millennial generation attitudes to sustainable wine: An exploratory study on Italian consumers. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 66, 537–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Salvo, M.; Capitello, R.; Begalli, D. How CS can be used for gaining info about consumers and the market? In Case Studies in the Wine Industry, 1st ed.; Santini, C., Cavicchi, A., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2018; ISBN 9780081009444. [Google Scholar]

- Sogari, G.; Mora, C.; Menozzi, D. Factors driving sustainable choice: The case of wine. Br. Food J. 2016, 118, 632–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, I.; Stumpf, T.; Reynolds, D. A Comparison of the Influence of Purchaser Attitudes and Product Attributes on Organic Wine Preferences. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2014, 55, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sogari, G.; Corbo, C.; Macconi, M.; Menozzi, D.; Mora, C. Consumer attitude towards sustainable-labelled wine: An exploratory approach. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2015, 27, 312–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonn, M.A.; Kim, W.G.; Kang, S.; Cho, M. Purchasing Wine Online: The Effects of Social Influence, Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and Wine Involvement. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2015, 25, 841–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, M.; Di Vita, G.; Monaco, L. Exploring environmental consciousness and consumer preferences for organic wines without sulfites. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 120, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sogari, G.; Pucci, T.; Aquilani, B.; Zanni, L. Millennial Generation and Environmental Sustainability: The Role of Social Media in the Consumer Purchasing Behavior for Wine. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capitello, R.; Sirieix, L. Consumers’ Perceptions of Sustainable Wine: An Exploratory Study in France and Italy. Economies 2019, 7, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Vita, G.; Caracciolo, F.; Brun, F.; D’Amico, M. Picking out a wine: Consumer motivation behind different quality wines choice. Wine Econ. Policy 2019, 8, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tait, P.; Saunders, C.; Dalziel, P.; Rutherford, P.; Driver, T.; Guenther, M. Estimating wine consumer preferences for sustainability attributes: A discrete choice experiment of Californian Sauvignon blanc purchasers. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 233, 412–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caliskan, A.; Celebi, D.; Pirnar, I. Determinants of organic wine consumption behavior from the perspective of the theory of planned behavior. Int. J. Wine Res. 2021, 33, 360–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabina del Castillo, E.J.; Díaz Armas, R.J.; Gutiérrez Taño, D. An Extended Model of the Theory of Planned Behaviour to Predict Local Wine Consumption Intention and Behaviour. Foods 2021, 10, 2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerro, M.; Yeh, C.H.; Klink-Lehmann, J.; Vecchio, R.; Hartmann, M.; Cembalo, L. The effect of moderating variables on consumer preferences for sustainable wines. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 94, 104336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nave, A.; Laurett, R.; Do Paço, A. Relation between antecedents, barriers and consequences of sustainable practices in the wine tourism sector. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 20, 100584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, G. Consumer engagement with sustainable wine: An application of the Transtheoretical Model. Food Res. Int. 2023, 174 Pt 1, 113555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rui, M.; Rosa, F.; Viberti, A.; Brun, F.; Massaglia, S.; Blanc, S. Understanding Factors Associated with Interest in Sustainability-Certified Wine among American and Italian Consumers. Foods 2024, 13, 1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, M.; Armitage, C.J. Extending the theory of planned behavior: A review and avenues for further research. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 28, 1429–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, T.; Dennis, C. Unethical Consumers: Deshopping Behaviour Using the Qualitative Analysis of Theory of Planned Behaviour and Accompanied (de) Shopping. Qual. Mark. Res. 2006, 9, 282–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, T.; Zhou, M.; Noyes, J. Teachers and technology: Development of an extended theory of planned behaviour. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2016, 64, 1033–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Fan, J.; Zhao, D.; Yang, S.; Fu, Y. Predicting consumers’ intention to adopt hybrid electric vehicles: Using an extended version of the theory of planned behavior model. Transportation 2016, 43, 123–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimy, M.; I Zareban, I.; Araban, M.; Montazeri, A. An extended theory of planned behavior (TPB) used to predict smoking behavior amng a sample of Iranian medical students. Int. J. High Risk Behav. Addict. 2015, 4, e24715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, H.; Shi, J.-G.; Tang, D.; Wen, S.; Miao, W.; Duan, K. Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior in Environmental Science: A Comprehensive Bibliometric Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tommasetti, A.; Singer, P.; Troisi, O.; Maione, G. Extended Theory of Planned Behavior (ETPB): Investigating Customers’ Perception of Restaurants’ Sustainability by Testing a Structural Equation Model. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuriev, A.; Dahmen, M.; Paillé, P.; Boiral, O.; Guillaumie, L. Pro-environmental behaviors through the lens of the theory of planned behavior: A scoping review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 155, 104660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwell, R.D.; Miniard, P.W.; Engel, J.F. Consumer Behavior; Thomson South-Western: Mason, OH, USA, 2006; p. 774. ISBN 9780324271973. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Bravo, P.; Chambers, V.E.; Noguera-Artiaga, L.; Sendra, E.; Chambers, E.E., IV; Carbonell-Barrachina, A.A. Consumer understanding of sustainability concept in agricultural products. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 89, 104136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghikhah, F.; Voinov, A.; Shukla, N.; Filatova, T. Exploring consumer behavior and policy options in organic food adoption: Insights from the Australian wine sector. Environ. Sci. Policy 2020, 109, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlay, K.A.; Trafimow, D.; Moroi, E. The Importance of Subjective Norms on Intentions to Perform Health Behaviors. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 29, 2381–2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Swidi, A.; Mohammed Rafiul Huque, S.; Haroon Hafeez, M.; Noor Mohd Shariff, M. The role of subjective norms in theory of planned behavior in the context of organic food consumption. Br. Food J. 2014, 116, 1561–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnoli, L.; Capitello, R.; Begalli, D. Behind intention and behaviour: Factors influencing wine consumption in a novice market. Br. Food J. 2016, 118, 660–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maksan, M.T.; Kovačić, D.; Cerjak, M. The influence of consumer ethnocentrism on purchase of domestic wine: Application of the extended theory of planned behaviour. Appetite 2019, 142, 104393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijekoon, R.; Sabri, M.F. Determinants That Influence Green Product Purchase Intention and Behavior: A Literature Review and Guiding Framework. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.; Johnson, K.K.P. Influences of environmental and hedonic motivations on intention to purchase green products: An extension of the theory of planned behavior. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2019, 18, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerri, J.; Testa, F.; Rizzi, F. The more I care, the less I will listen to you: How information, environmental concern and ethical production influence consumers’ attitudes and the purchasing of sustainable products. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 175, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brugarolas, M.; Martinez-Carrasco, L.; Bernabeu, R.; Martinez-Poveda, A. A contingent valuation analysis to determine profitability of establishing local organic wine markets in Spain. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2010, 25, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishore, J.; Vasundhra, S.; Anand, T. Formulation of a Research Question. Ind. J. Med. Spec. 2011. Available online: http://www.ijms.in/articles/2/2/formulation-of-a-research-question.html (accessed on 3 September 2024). [CrossRef]

- Sandberg, J.; Alvesson, M. Ways of constructing research questions: Gap-spotting or problematization? Organization 2011, 18, 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, A. The Research Question in Social Research: What is its Role? Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2007, 10, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericsson, K.A.; Simon, H.A. Verbal reports on thinking. In Introspection in Second Language Research; Faerch, C., Kasper, G., Eds.; Multilingual Matters, Ltd.: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1987; pp. 24–53. [Google Scholar]

- Harte, J.M.; Westenberg, M.R.M.; van Someren, M. Process models of decision making. Acta Psychol. 1994, 87, 95–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilhooly, K.J.; Fioratou, E.; Anthony, S.H.; Wynn, V. Divergent thinking: Strategies and executive involvement in generating novel uses for familiar objects. Br. J. Psychol. 2007, 98, 611–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, M.; Watson, V.; Entwistle, V. Rationalising the ‘irrational’: A think aloud study of discrete choice experiment responses. Health Econ. 2009, 18, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putri, C.H.; Rosa, A.D.E. Impact of Sustainability Awareness in Fashion on Purchase Intention: Mediating Variable of Sustainability Commitment. J. Bus. Manag. Soc. Stud. 2023, 3, 146–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, G.J.; Best, M. An exploration of consumer perceptions of sustainable wine. J. Wine Res. 2023, 34, 232–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonn, A.; Allott, T.; Evans, M.; Joosten, H.; Stoneman, R. Peatland restoration and ecosystem services: An introduction. In Peatland Restoration and Ecosystem Services: Science, Policy and Practice. Ecological Reviews; Bonn, A., Allott, T., Evans, M., Joosten, H., Stoneman, R., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.; Li, C.; Khan, A.; Qalati, S.A.; Naz, S.; Rana, F. Purchase intention toward organic food among young consumers using theory of planned behavior: Role of environmental concerns and environmental awareness. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2021, 64, 796–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Cengage: Boston, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- St James, M.; Christodoulidou, N. Factors influencing wine consumption in Southern California consumers. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2011, 23, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Zanten, R. Drink Choice: Factors Influencing the Intention to Drink Wine. Int. J. Wine Mark. 2005, 17, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruzgys, S.; Pickering, G.J. Gen Z and sustainable diets: Application of The Transtheoretical Model and the theory of planned behaviour. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 434, 140300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francesca, A.; Massari, S.; Francesca, R.; Domenico, D. Empathy, food systems and design thinking for fostering youth agency in sustainability: A new pedagogical model. In Transdisciplinary Case Studies on Design for Food and Sustainability; Woodhead Publishing: Sutton, UK, 2021; pp. 197–216. [Google Scholar]

- Capitello, R.; Agnoli, L.; Begalli, D. Determinants of consumer behaviour in novice markets: The case of wine. J. Res. Mark. Entrep. 2015, 17, 110–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.P.; Figueiredo, I.; Hogg, T.; Sottomayor, M. Young adults and wine consumption a qualitative application of the theory of planned behavior. Br. Food J. 2014, 116, 832–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garanti, Z. Impact of sustainability awareness and attitudes on intention to purchase sustainable fashion clothing: Mediating role of sustainability commitment. Pazarlama Pazarlama Araştırmaları Derg. 2020, 13, 29–48. [Google Scholar]

| Authors | Country | Methodology | Main Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ginon et al. [57] | France | Online survey 127 respondents | There are considerable differences in the way consumers perceive logos. These do not convey a message about environmental sustainability, reaffirming the necessity to provide consumers with proper information on environmental sustainability. |

| Pomarici & Vecchio [58] | Italy | Online survey 500 respondents | When analyzing Millennials’ interest and wtp for wines with certain labels certifying ethical, social and environmental attributes, it is observed that labels related to social features show the greatest interest. Residing in urban areas, being female, and older increases the likelihood of purchasing sustainable wines. |

| Rahman et al. [61] | USA | Online survey and sensory evaluation 224 respondents | Despite theoretical evidence reinforcing that wine consumers’ purchase decisions are influenced by whether a wine is organic and by personal attitudes, it is observed that taste overwhelmed the other influences in respondents’ wine selection. |

| Sogari et al. [62] | Italy | Online survey 495 respondents | The cluster analysis confirms the existence of different consumer segments named as well-disposed; not interested; skeptical; and adverse. Also, consumers with a positive attitude regarding sustainable wine and stronger beliefs on environmental protection have higher wtp for sustainable wine. |

| Bonn et al. [63] | USA | Face-to-face survey Unknown number of respondents | Consumer perceptions of wine producers’ sustainable practices affect their decision making on organic wine. Moreover, consumer’s attitudes on organic wine attributes related to price, health, and environment have important effects on behavioral intentions. Also, consumers who trust wine retailers are more likely to engage in positive results. |

| D’Amico et al. [64] | Italy | Face-to-face survey 201 respondents | Environmental consciousness and curiosity lead consumers to pay a higher price for organic wines, while naturalness and origin designation are the characteristics positively related to the wtp a premium price for organic wines. |

| Sogari et al. [65] | Italy | Online survey 2597 respondents | The greater the importance the consumer attributes to the product/process dimension of environmental sustainability, the higher the self-selection in market segments. Social media has the power to increase sustainability awareness, influencing the consumer’s wine purchasing behavior. |

| Capitello & Sirieix [66] | France & Italy | Online survey 210 Italian and 148 French respondents | Consumers involved with wine are more able to evaluate product-attribute associations for sustainable wines than ethically minded consumers who are not involved with wine. Sustainable wine marketers should pay more attention to the consumer involvement with wine. |

| Di vita et al. [67] | Italy | Online survey 1200 respondents | The wine consumption determinants vary according to each range of wine quality and hence support a hierarchical scale of quality wines. Consumers’ motivation progressively changes as the wine quality scales increase or decrease. Regarding bulk wine consumption, it is closely associated to wine tourism and the intention to purchase locally produced wines. |

| Tait et al. [68] | USA | Online survey 766 respondents | The presence of sustainability attributes may influence the Sauvignon blanc choice and consumers have a relevant positive wtp for many of these attributes. Price is the main attribute, and wtp significantly varies depending on where a wine is made, and the critical score a wine receives. |

| Caliskan et al. [69] | Turkey | TPB Online survey 317 respondents | Individuals’ attitude has the strongest impact on intention and indirect effect on organic wine consumption. Subjective norms also have a significant impact on intention and organic wine consumption. Perceived behavioral control has the least impact, focusing on a person’s perceived convenience and challenges in carrying out a behavior. |

| Sabina del Castillo et al. [70] | Canary Island | TPB Online survey 762 respondents | There is a relationship between intention and perceived behavioral control. Additionally, the ethnocentric personality has a positive influence, and the cosmopolitan personality has a negative influence. The personal norm and place identity are also related to attitudes regarding such behavior. |

| Lerro et al. [71] | Italy & German | Experimental session and online survey 93 Italian and 85 German respondents | Sustainability allows for the possibility of a premium, despite the fact that its full potential can only be achieved for producers satisfying consumers’ sensory expectations. Consumers’ involvement with sustainable wine offers the potential for an above average premium. Consumers with a high level of sustainability concerns have a high wtp for wine sustainability characteristics. |

| Nave et al. [72] | Portugal | Primary data from 103 Portuguese wine tourism companies | Internal and external pressures influence the adoption of sustainable practices in wine tourism, which can result in benefits for companies in this sector. It is also concluded that even if some barriers are perceived by entrepreneurs, they tend to persist adopting sustainable practices in wine tourism. |

| Valenzuela et al. [50] | Chile | Online survey 526 respondents | Most respondents have already purchased wines with ecological certification and intend to buy wines with ecological certification in the future, particularly organic and sustainable wines. A significant percentage of respondents revealed a wtp a premium price, ranging between 5 and 16 US dollars and more, for organic and sustainable wines. |

| Trigo et al. [17] | Portugal | Face-to-face interviews with leading wine specialists 33 respondents | Sustainability perception by the Portuguese wine sector can be sliced into three core domains of concern that resemble the so-called ESG factors. It is suggested that the approaches that go beyond ESG factors, by integrating social, environmental, and corporate governance with political orientations, are adopted. |

| Sgroi et al. [27] | Italy | Online survey 528 respondents | Consumers are not very aware of sustainability and this lack of awareness regarding sustainable wine is, at least in part, attributable to confusion within the industry. |

| Pickering [73] | Canada | Online survey 727 respondents | Consumers are changing regarding sustainable wine, as the development of education and sustainable certification initiatives are important. It is observed that wine involvement and sustainability cues in wine purchase are the most consistent predictors of both action and inaction, while age, taste expectation, and perceived quality are predictive for some behaviors in sustainable wine consumption. |

| Rui et al. [74] | USA & Italy | Online survey 1000 USA and 1250 Italian respondents | There is a deeper relationship between demographics and interest in sustainability-certified wine among US consumers than Italian consumers. The link patterns between consumers’ wine-buying behavior and interest in sustainable wine are similar for the two countries. In particular, consumers who buy wine weekly have a keen interest, and those who buy wine sporadically have no or little interest. |

| Martínez-Falcó et al. [48] | World | Bibliometric and systematic review | It provides an analysis of how sustainable practices may be integrated into winemaking, which is to the determinant of industry practitioners. To encourage sustainable practices in the wine industry, it is essential to promote innovation, technology, policies and collaborative strategies among different stakeholders, namely researchers, industry professionals and policy makers. |

| Latent Variables | Items |

|---|---|

| Attitudes (ATT) | ATT1: I believe that consuming sustainable wine contributes to protecting the environment. ATT2: I think it is essential for wine producers to adopt sustainability initiatives/practices. ATT3: I think it is very important that consumers value sustainability in their wine consumption decisions. |

| Subjective Norms (SN) | SN1: My family thinks I should always choose to consume sustainable wine. SN2: Most of the people I care about consume sustainable products. SN3: My closest friends think I should consume sustainable wine. |

| Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC) | PBC1: If I want to, I can consume sustainable wine. PBC2: I think it is easy for me to consume sustainable wine. PBC3: It is essentially up to me whether I consume sustainable wine. |

| Sustainability Awareness (SUS) | SUS1: It is very important that the wine I consume be produced without the use of artificial inorganic fertilizers, pesticides, herbicides, and fungicides. SUS2: It is very important to the environment that the wine I consume be produced with minimal use of water and energy. SUS3: It is very important that the wine I consume be produced in a form that supports the local economy and local communities. SUS4: It is very important that the wine I consume be produced by a company that respects human rights. SUS5: It is very important that the wine I consume be produced by a company that promotes health and safety conditions for workers. SUS6: It’s very important that the wine I consume be produced by a company that contributes to the economy and improves the lives of society in general. |

| Sustainable Wine Consumption Intention (INT) | INT1: I intend to consume sustainable wine soon. INT2: I drink sustainable wine whenever I can, and I intend to continue doing so. INT3: I really want to drink sustainable wine. |

| Sustainable Wine Consumption Behavior (BEH) | BEH1: I usually consume sustainable wine. BEH2: I prefer sustainable wine to conventional wine. BEH3: For the last six months, I have been drinking sustainable wine. |

| Latent Variables | Items | Loading | AVE | CR | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitudes (ATT) | ATT1 | 0.856 | 0.747 | 0.899 | 0.897 |

| ATT2 | 0.894 | ||||

| ATT3 | 0.842 | ||||

| Subjective Norms (SN) | SN1 | 0.813 | 0.684 | 0.867 | 0.866 |

| SN2 | 0.859 | ||||

| SN3 | 0.814 | ||||

| Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC) | PBC1 | 0.857 | 0.702 | 0.876 | 0.876 |

| PBC2 | 0.880 | ||||

| PBC3 | 0.785 | ||||

| Sustainability Awareness (SUS) | SUS1 | 0.689 | 0.709 | 0.935 | 0.935 |

| SUS2 | 0.762 | ||||

| SUS3 | 0.840 | ||||

| SUS4 | 0.897 | ||||

| SUS5 | 0.943 | ||||

| SUS6 | 0.895 | ||||

| Sustainable Wine Consumption Intention (INT) | INT1 | 0.797 | 0.663 | 0.855 | 0.853 |

| INT2 | 0.813 | ||||

| INT3 | 0.831 | ||||

| Sustainable Wine Consumption Behavior (BEH) | BEH1 | 0.901 | 0.683 | 0.863 | 0.844 |

| BEH2 | 0.659 | ||||

| BEH3 | 0.880 |

| ATT | SN | PBC | SUST | INT | BEH | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATT | 0.865 | |||||

| SN | 0.429 | 0.827 | ||||

| PBC | 0.426 | 0.510 | 0.838 | |||

| SUST | 0.477 | 0.443 | 0.450 | 0.812 | ||

| INT | 0.600 | 0.558 | 0.369 | 0.552 | 0.814 | |

| BEH | 0.246 | 0.580 | 0.389 | 0.469 | 0.680 | 0.827 |

| Path | Coefficient | t-Statistics | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1: ATT ⟶ INT | 0.280 | 3.969 | 0.000 |

| H2: SN ⟶ INT | 0.309 | 4.095 | 0.000 |

| H3: PBC ⟶ INT | −0.056 | −0.883 | 0.377 |

| H5: SUS ⟶ INT | 0.242 | 3.546 | 0.000 |

| H6: INT ⟶ BEH | 0.855 | 7.746 | 0.000 |

| H4: PBC ⟶ BEH | 0.181 | 2.281 | 0.023 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sousa, S.; Correia, E.; Viseu, C. Exploring Portuguese Consumers’ Behavior Regarding Sustainable Wine: An Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8813. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16208813

Sousa S, Correia E, Viseu C. Exploring Portuguese Consumers’ Behavior Regarding Sustainable Wine: An Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior. Sustainability. 2024; 16(20):8813. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16208813

Chicago/Turabian StyleSousa, Sara, Elisabete Correia, and Clara Viseu. 2024. "Exploring Portuguese Consumers’ Behavior Regarding Sustainable Wine: An Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior" Sustainability 16, no. 20: 8813. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16208813

APA StyleSousa, S., Correia, E., & Viseu, C. (2024). Exploring Portuguese Consumers’ Behavior Regarding Sustainable Wine: An Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior. Sustainability, 16(20), 8813. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16208813