Shifting Workplace Paradigms: Twitter Sentiment Insights on Work from Home

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Gap and Significance of This Paper

3. Literature Review

3.1. Research on Social Media and Twitter

3.2. WFH and Sustainable Development

3.3. Twitter and Employee Voice

3.4. Work from Home (WFH) during the COVID-19 Pandemic

3.5. Sentiment-Analysis Studies

4. Method

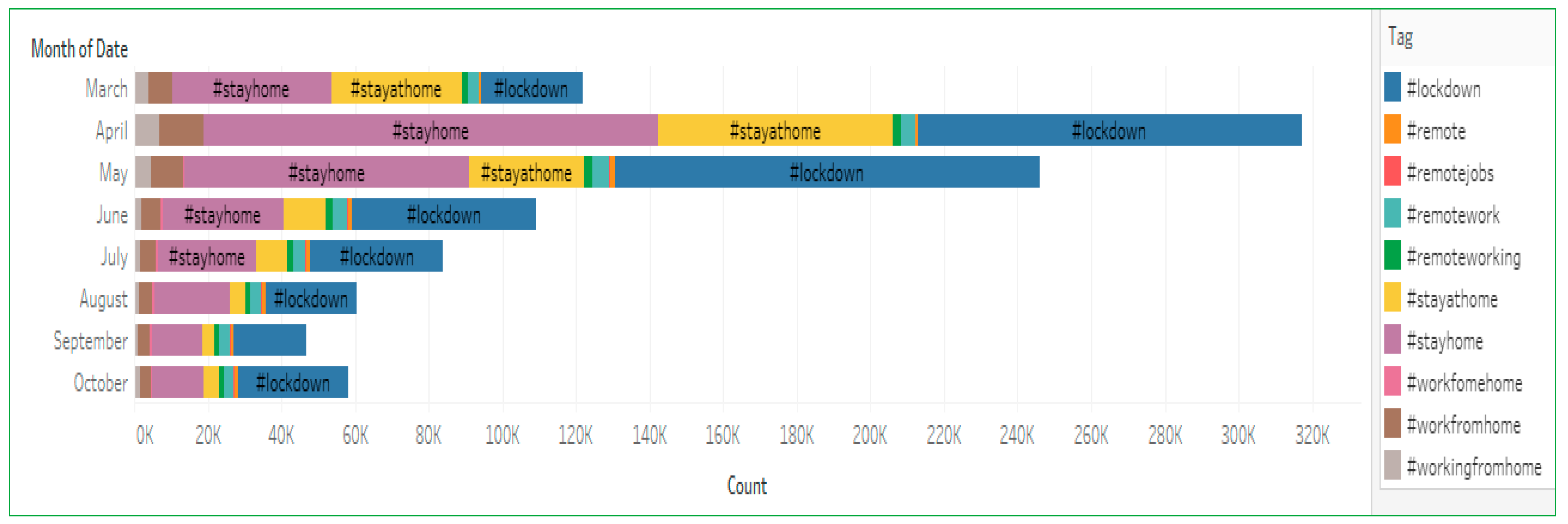

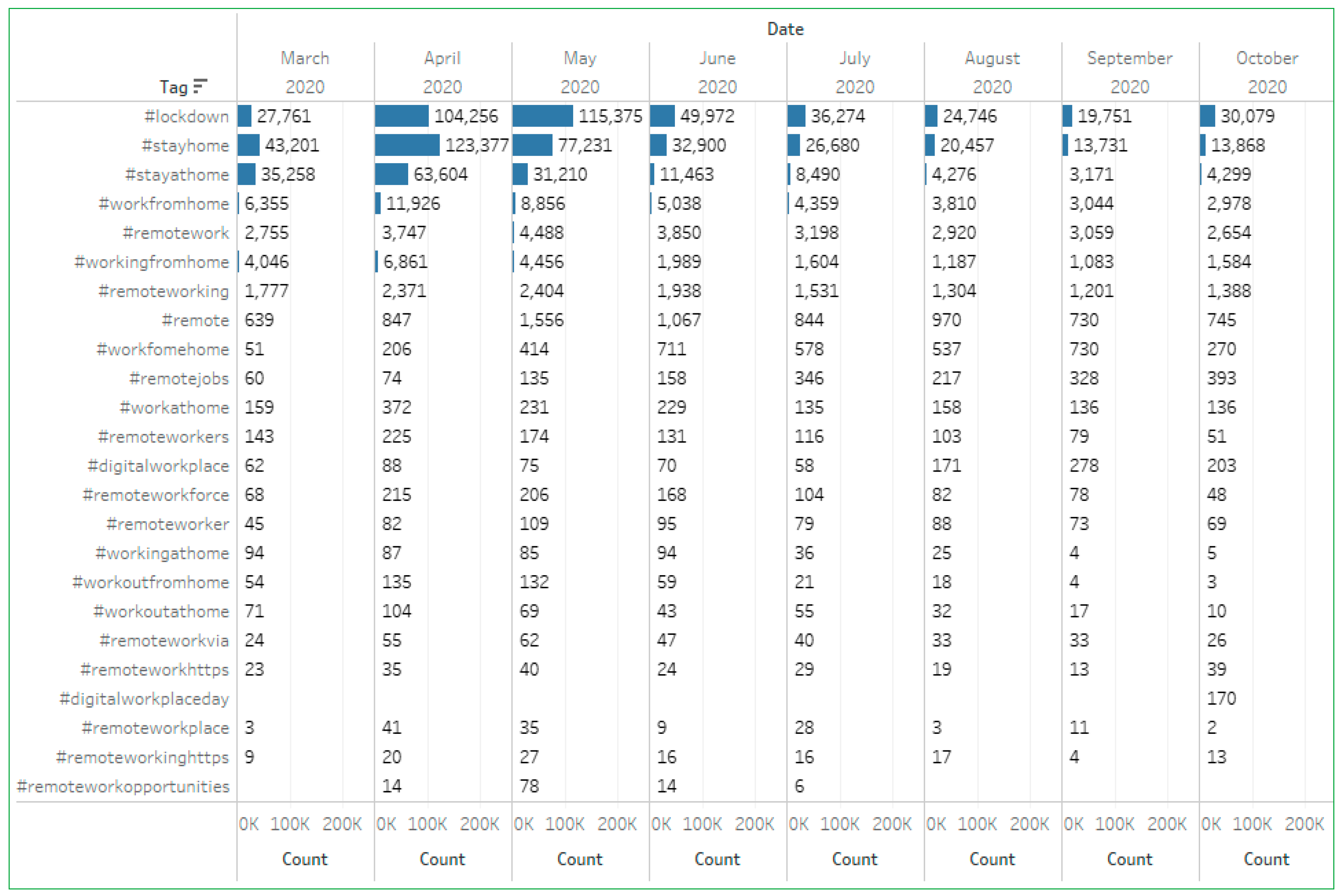

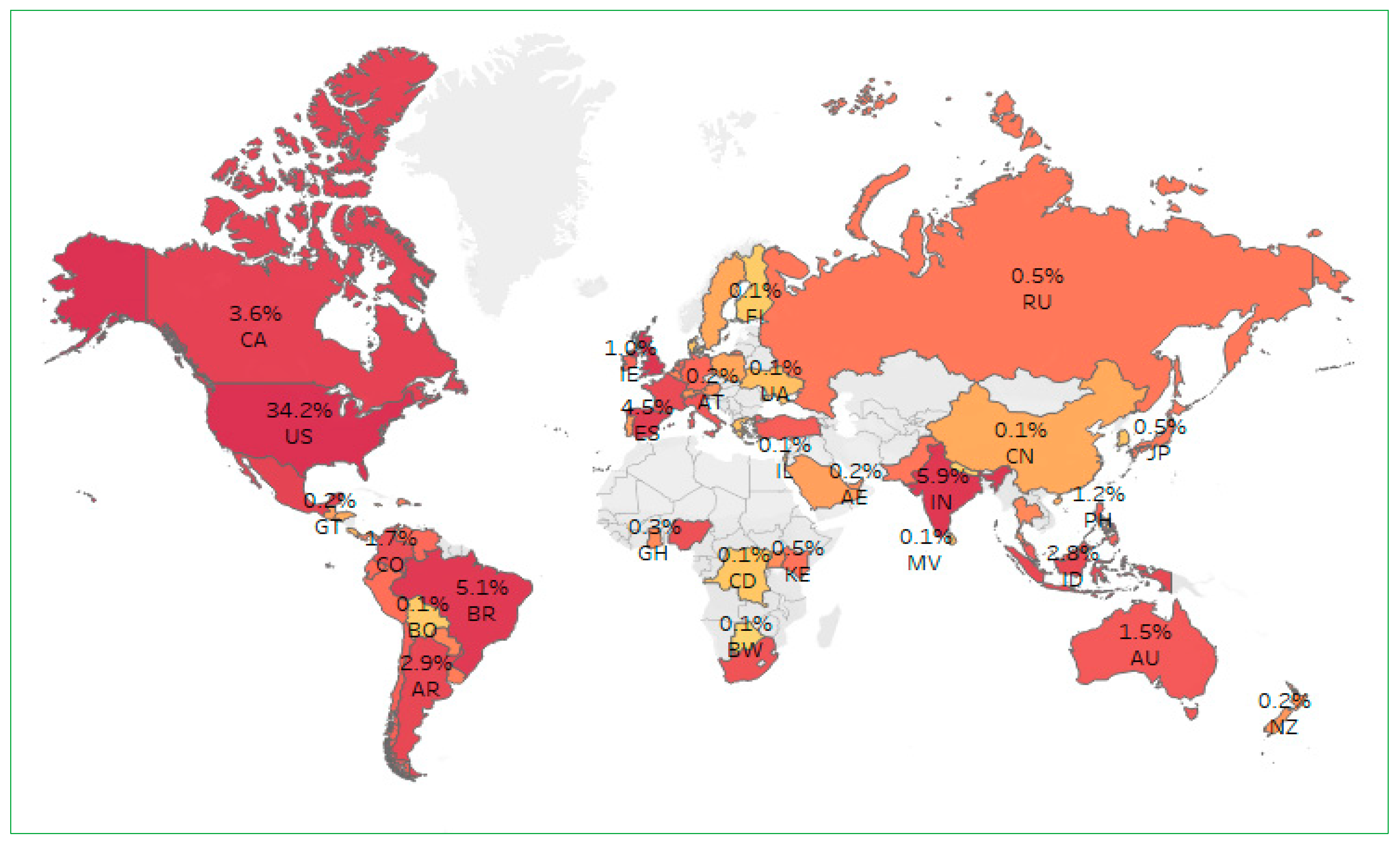

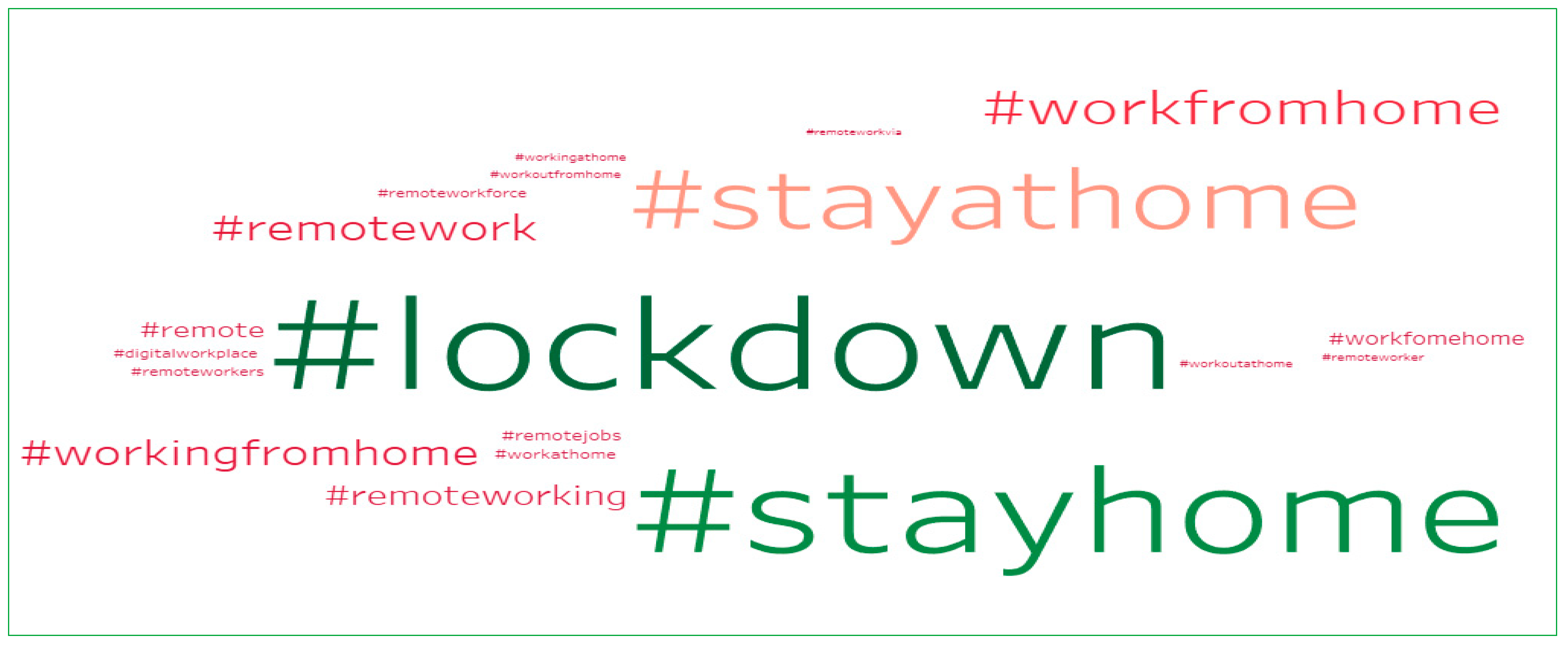

5. Results

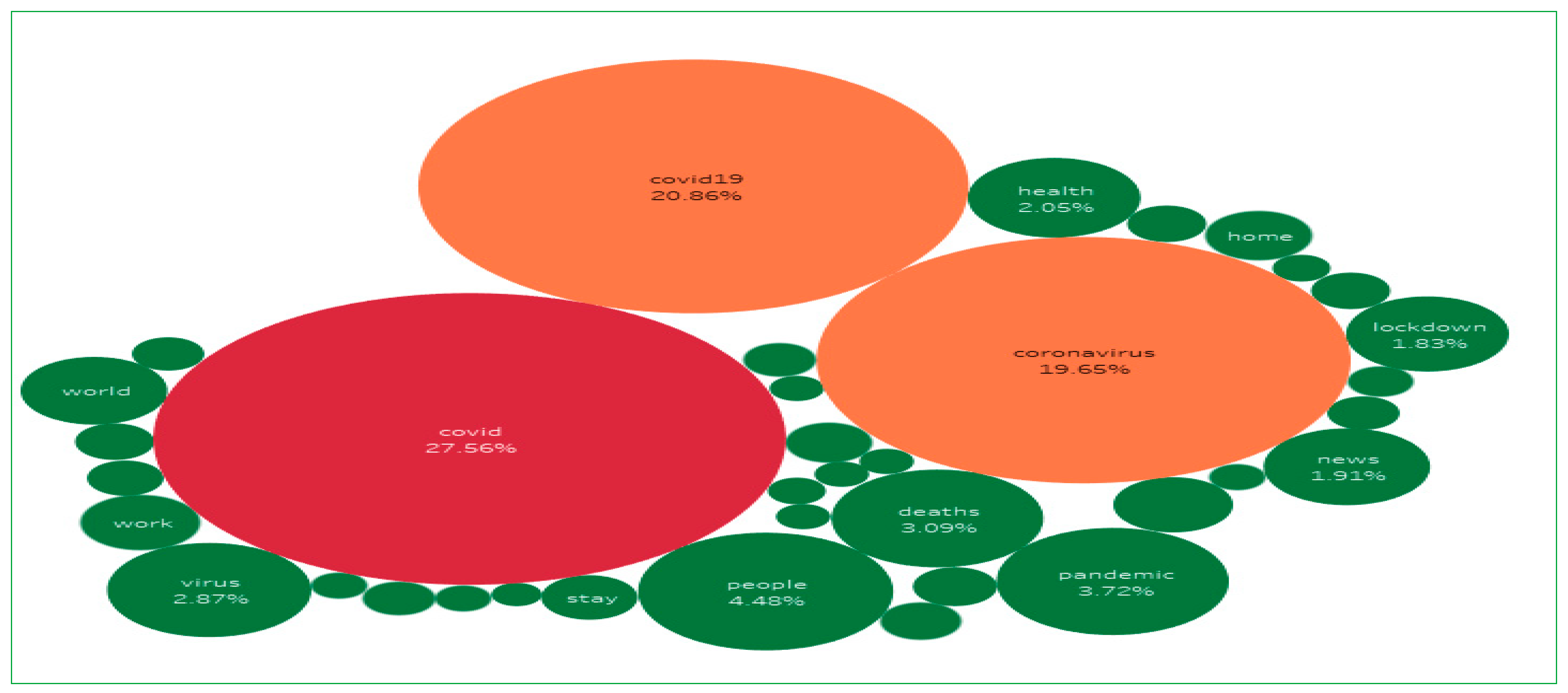

5.1. Text Mining and Word Frequency

- #stayhome or #stayathome

- #work*home” or #working*home

- #remote*work* or #remote*jobs or $#remote

- #digitalwork*

- #lockdown

5.2. Network-Mapping Analysis

5.3. Sentiment Analysis

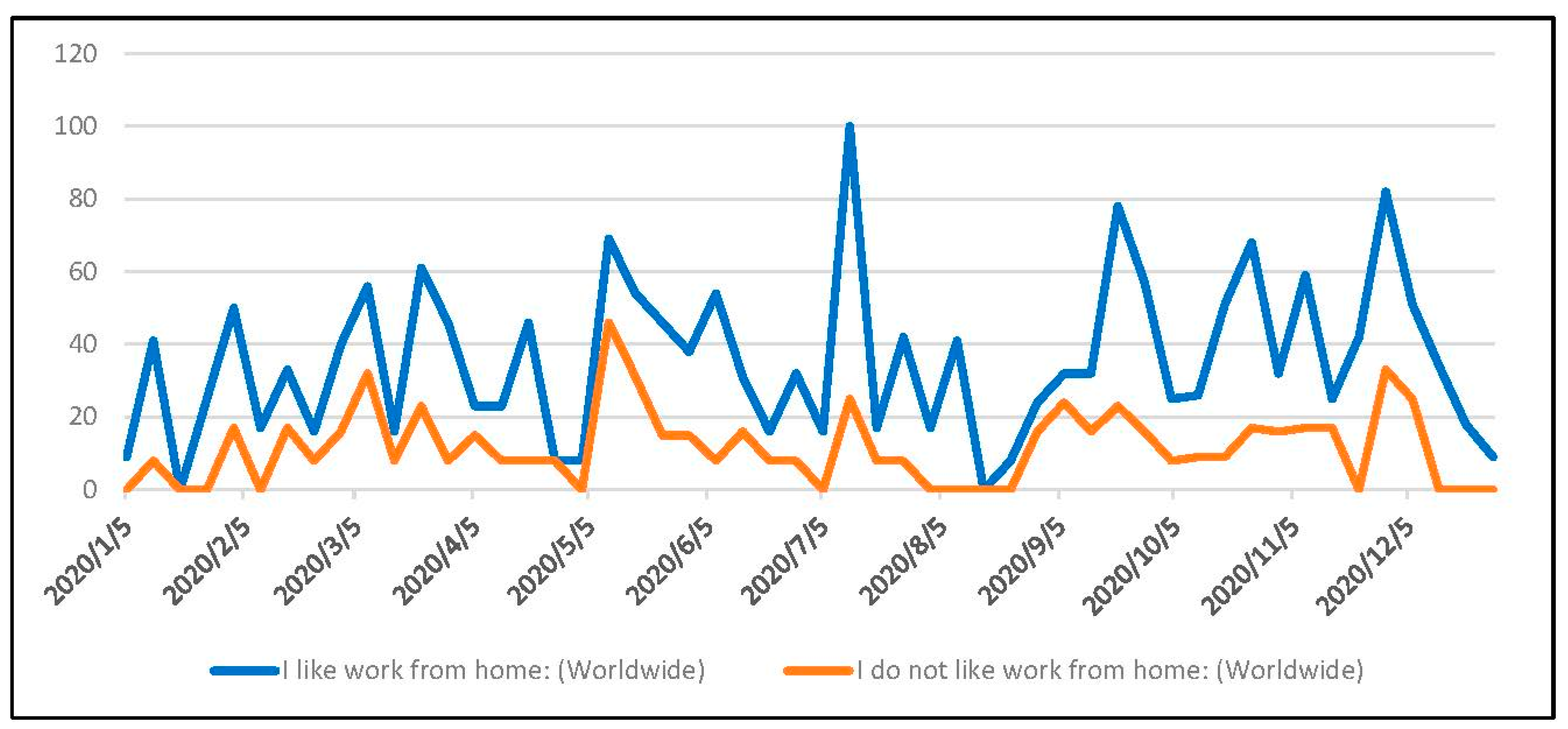

5.4. Google Trend Analysis

6. Discussion and Implications

7. Limitations, and Future Research

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lwin, M.O.; Lu, J.; Sheldenkar, A.; Schulz, P.J.; Shin, W.; Gupta, R.; Yang, Y. Global sentiments surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic on Twitter: Analysis of Twitter trends. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020, 6, e19447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams-Prassl, A.; Boneva, T.; Golin, M.; Rauh, C. Inequality in the Impact of the Coronavirus Shock: Evidence from Real-Time Surveys. J. Public Econ. 2020, 189, 104245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foote, C.; Nordhaus, W.D.; Rivers, D. The US Employment Situation Using the Yale Labor Survey; Cowles Foundation Discussion Papers 2020, 2243. Cowles Foundation for Research in Economics; Yale University: Singapore, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Barrero, J.M.; Bloom, N.; Davis, S.J. Why Working from Home Will Stick. Unpublished Manuscript. 2021. Available online: https://nbloom.people.stanford.edu/sites/g/files/sbiybj4746/f/why_wfh_stick1_0.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Daneshfar, Z.; Asokan-Ajitha, A.; Sharma, P.; Malik, A. Work-from-home (WFH) during COVID-19 pandemic—A netnographic investigation using Twitter data. Inf. Technol. People 2023, 36, 2161–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, P.; Foroughi, C.; Larson, B. Work-from-anywhere: The productivity effects of geographic flexibility. Strateg. Manag. J. 2021, 42, 655–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddud, A.; Dugger, J.C.; Gill, P. Exploring the impact of internal social media usage on employee engagement. J. Soc. Media Organ. 2016, 3, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Haque, A. The effect of presenteeism among Bangladeshi employees. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2023, 72, 873–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadarshini, C.; Dubey, R.K.; Kumar, Y.L.N.; Jha, R.R. Impact of a Social Media Addiction on Employees’ Wellbeing and Work Productivity. Qual. Rep. 2020, 25, 181–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, H.; Gopalan, N.; Lee, J.; Kirige, I.; Haque, A.; Yadav, V.; Lambropoulos, V. Impact of Work and Non-Work Support on Employee Well-Being: The Moderating Role of Perceived Organizational Support. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, M.M. Clustering halal food consumers: A Twitter sentiment analysis. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2019, 61, 320–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macnamara, J.; Zerfass, A. Social media communication in organizations: The challenges of balancing openness, strategy, and management. Int. J. Strateg. Commun. 2012, 6, 287–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, D. Twitter; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Anakpo, G.; Nqwayibana, Z.; Mishi, S. The Impact of Work-from-Home on Employee Performance and Productivity: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Chen, J.; Chen, C.; Zheng, C.; Li, S.; Zhu, T. Public discourse and sentiment during the COVID-19 pandemic: Using Latent Dirichlet Allocation for topic modeling on Twitter. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0239441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, J.; Chen, J.; Hu, R.; Chen, C.; Zheng, C.; Su, Y.; Zhu, T. Twitter discussions and emotions about the COVID-19 pandemic: Machine learning approach. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e20550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendradi, P.; Abd Ghani, M.K.; Mahfuzah, S.N. A Literature Review of e-Learning Technology in Higher Education. J. Comput. Sci. Technol. Stud. 2023, 5, 01–07. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asatiani, A.; Norström, L. Information systems for sustainable remote workplaces. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2023, 32, 101789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvanathan, M.; Hussin, N.A.M.; Azazi, N.A.N. Students learning experiences during COVID-19: Work from home period in Malaysian Higher Learning Institutions. Teach. Public Admin. 2023, 41, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S.; Haque, A. Faculty readiness for online crisis teaching: The role of responsible leadership and teaching satisfaction in academia. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2022, 36, 1112–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontopoulos, E.; Berberidis, C.; Dergiades, T.; Bassiliades, N. Ontology-based sentiment analysis of Twitter posts. Expert Syst. Appl. 2013, 40, 4065–4074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, D.; Bermejo, P.H.; Santos, P. Can social media reveal the preferences of voters? A comparison between sentiment analysis and traditional opinion polls. J. Inf. Technol. Politics 2017, 14, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Wu, D. Using text mining and sentiment analysis for online forums hotspot detection and forecast. Decis. Support Syst. 2010, 48, 354–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, R.; Dores, R.; Camilo-Junior, C.; Rosa, T. SentiHealth-Cancer: A sentiment analysis tool to help detecting mood of patients in online social networks. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2016, 85, 80–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brian, P.K.; Michael, O.C.; Kevin, C.B. Using Twitter Data for Cruise Tourism Marketing and Research. J. Travel Tour. Market. 2016, 33, 885–898. [Google Scholar]

- Meluch, A.; Kallis, R. Where and why coworkers connect on social media: Examining employees’ motivations for connecting with coworkers on social media. J. Soc. Media Soc. 2023, 12, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Thelwall, M.; Buckley, K.; Paltoglou, G. Sentiment in Twitter events. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2011, 62, 406–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, B.J.; Zhang, M.; Sobel, K.; Chowdury, A. Twitter power: Tweets as electronic word of mouth. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2009, 60, 2169–2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, H.; Lee, C.; Park, H.; Moon, S. What is Twitter, a social network or a news media? In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on World Wide Web, Raleigh, NC, USA, 26–30 April 2010; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 591–600. [Google Scholar]

- Bouncken, R.B.; Lapidus, A.; Qui, Y. Organizational Sustainability Identity: ‘New Work’ of Home Offices and Coworking Spaces as Facilitators. Sustain. Technol. Entrep. 2022, 1, 100011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.I.; Haque, A.; Bartram, T. Unleashing Employee Potential: A Mixed-Methods Study of High-Performance Work Systems in Bangladeshi Banks. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, B.W.; Kee, K.F. Social media at work: The roles of job satisfaction, employment status, and Facebook use with co-workers. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 70, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, A.; Khan, S.I. Promoting meaningfulness in work for higher job satisfaction: Will intent to quit make trouble for business managers? J. Organ. Eff. People Perform. 2023, 10, 455–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, P.; Cooper, B.K.; Hecker, R. Use of social media at work: A new form of employee voice? Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 27, 2621–2634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerbe, W.J.; Paulhus, D.L. Socially desirable responding in organizational behavior: A reconception. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1987, 12, 250–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, L.G.; Li, Y.; Luo, Y. Production and dissemination of corporate information in social media: A review. J. Account. Lit. 2019, 42, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llewellyn, S. COVID-19: How to be careful with trust and expertise on social media. BMJ 2020, 25, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balnave, N.; Barnes, A.; MacMillan, R.; Thornthwaite, L. E-voice: How network and media technologies are shaping employee voice. In Handbook of Research on Employee Voice: Elgar Original Reference; Edward Elgar Publishing: Northampton, MA, USA, 2014; p. 439. [Google Scholar]

- Budd, J.; Gollan, P.; Wilkinson, A. New approaches to employee voice and participation in organizations. Hum. Relat. 2010, 63, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dingel, J.; Neiman, B. How many jobs can be done at home? J. Public Econ. 2020, 189, 104235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrot, J.N.; Grassi, B.; Sauvagnat, J. Sectoral effects of social distancing. In AEA Papers and Proceedings; American Economic Association: Nashville, TN, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Boeri, T.; Caiumi, A.; Paccagnella, M. Mitigating the Work-Security Trade-Off While Rebooting the Economy; Covid Economics Vetted and Real-Time Papers No. 2; Center for Economic Policy Research-CEPR: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mateyka, P.J.; Rapino, M.; Landivar, L.C. Home-Based Workers in the United States: 2010; US Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, US Census Bureau: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb, C.; Grobovsek, J.; Poschke, M. Working from home across countries. Covid Econ. 2020, 1, 71–91. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, R.; Heide, M.; Simonsson, C. 2. Digital corporate communication and internal communication. In Handbook Digital Corporate Communication; Edward Elgar: London, UK,, 2023; p. 18. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, L.S.; Reiners, S.; Becker, J.; Hertel, G. Long-term effects of COVID-19 on work routines and organizational culture–A case study within higher education’s administration. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 163, 113927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herd, C. The Cost of the Office vs. Remote Work. 2020. Available online: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/cost-office-vs-remote-work-chris-herd/ (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Yu, Y.; Duan, W.; Cao, Q. The impact of social and conventional media on firm equity value: A sentiment analysis approach. Decis. Support Syst. 2013, 55, 919–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamy, F.; Daniulaityte, R.; Sheth, A.; Nahhas, R.; Martins, S.; Boyer, E.; Carlson, R. “Those edibles hit hard”: Exploration of Twitter data on cannabis edibles in the U.S. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016, 164, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.; Pang, B.; Lee, L. Get out the vote: Determining support or opposition from congressional floor-debate transcripts. In Proceedings of the 2006 Conference Empirical Methods Natural Language Processing, Sydney, Australia, 22–23 July 2006; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2006; pp. 190–197. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, K.; Xia, Y.; Xu, R.; Wu, M.; Li, W. Pattern-based opinion mining for stock market trend prediction. Int. J. Comput. Process. Lang. 2008, 21, 347–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghiassi, M.; Skinner, J.; Zimbra, D. Twitter brand sentiment analysis: A hybrid system using n-gram analysis and dynamic artificial neural network. Expert Syst. Appl. 2013, 40, 6266–6282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banda, J.M.; Tekumalla, R.; Wang, G.; Yu, J.; Liu, T.; Ding, Y.; Artemova, E.; Tutubalina, E.; Chowell, G. A large-scale COVID-19 Twitter chatter dataset for open scientific research—An international collaboration. Epidemiologia 2021, 2, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruns, A.; Stieglitz, S. Towards more systematic Twitter analysis: Metrics for tweeting activities. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2013, 16, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, M.; Hale, S.A.; Gaffney, D. Where in the world are you? Geolocation and language identification in Twitter. Prof. Geogr. 2014, 66, 568–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowri, S.; Jabez, J.; Vimali, J.S.; Sivasangari, A.; Srinivasulu, S. Sentiment Analysis of Twitter Data Using Techniques in Deep Learning. In Data Intelligence Cognitive Informatics; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 613–623. [Google Scholar]

- Birjali, M.; Kasri, M.; Beni-Hssane, A. A comprehensive survey on sentiment analysis: Approaches, challenges and trends. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2021, 226, 107134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasanth, S.; Singh, U.; Kumar, Y.L.N.; Jha, R.R. Forecasting spread of COVID-19 using Google Trends: A hybrid GWO-Deep learning approach. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2020, 142, 110336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamulka, J.; Jeruszka-Bielak, M.; Górnicka, M.; Drywień, M.E.; Zielinska-Pukos, M.A. Dietary Supplements during COVID-19 outbreak. Results of Google Trends analysis supported by PLifeCOVID-19 online studies. Nutrients 2021, 13, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanti, T.; Guidetti, G.; Mazzei, E.; Zappalà, S.; Toscano, F. Work from Home during the COVID-19 Outbreak: The Impact on Employees’ Remote Work Productivity, Engagement and Stress. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2021, 63, 426–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irawanto, D.W.; Novianti, K.R.; Roz, K. Work from home: Measuring satisfaction between work–life balance and work stress during the COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesia. Economies 2021, 9, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowell, C.P.; Herring, M.P.; Lansing, J.; Brower, C.; Meyer, J.D. Working From Home and Job Loss Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic Are Associated With Greater Time in Sedentary Behaviors. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 597619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, A.D.; Tripathi, S. Analyzing the Sentiments towards Work-From-Home Experience during COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Innov. Manag. 2020, 8, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linacre, S. Facebook, Twitter and the future of HR. Hum. Resour. Manag. Int. Dig. 2017, 25, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boxall, P.; Huo, M. Fostering the high-involvement model of human resource management: What have we learnt and what challenges do we face? Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2022, 60, 41–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, A. Strategic Human Resource Management and Presenteeism: A Conceptual Framework to Predict Human Resource Outcomes. N. Z. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2020, 18, 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Vega, R.P.; Anderson, A.J.; Kaplan, S.A. A Within-Person Examination of the Effects of Telework. J. Bus. Psychol. 2015, 30, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, T.D.; Golden, T.D.; Shockley, K.M. How effective is telecommuting? Assessing the status of our scientific findings. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 2015, 16, 40–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darouei, M.; Pluut, H. Work from home today for a better tomorrow! How working from home influences work-family conflict and employees’ start of the next workday. Stress Health 2021, 37, 986–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, M.; Cho, Y.; Song, H. How do managerial, task, and individual factors influence flexible work arrangement participation and abandonment? Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2021, 59, 645–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Stepchenkova, S. User-generated content as a research mode in tourism and hospitality applications: Topics, methods, and software. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2014, 23, 108–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blei, D.M. Probabilistic topic models. Commun. ACM 2012, 55, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvin, S.W.; Goldsmith, R.E.; Pan, B. Electronic word-of-mouth in hospitality and tourism management. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 458–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stieglitz, S.; Dang-Xuan, L. Emotions and information diffusion in social media—Sentiment of microblogs and sharing behavior. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2013, 29, 217–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. Twitter: Most Users by Country. 2021. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/242606/number-of-active-twitter-users-in-selected-countries/ (accessed on 15 December 2022).

| Text message | RT @HyperNephroma_: Those who can work from home its better to do so. You guys are privileged in this regards. I wish I could work from home but I can’t. Please visit health institutions only when truly needed. Otherwise, The Covid Tsunami can hit us badly. |

| Time frame | March 2020 to October 2020 |

| User’s screen name | asjha |

| Hashtags | #stayhome OR #stayathome, #work*home” OR #working*home, #remote*work* OR #remote*jobs OR $#remote, #digitalwork* (N.B: * represents a wild card) |

| Number of retweets | 18 |

| Language | English |

| Months and Total Hashtags | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| March | April | May | June | July | August | September | October |

| 122,829 | 319,072 | 247,747 | 110,286 | 84,769 | 61,361 | 47,720 | 59,142 |

| I hope you all work hard at home. You will see my efficiency increase by a lot. #workfromhome #office #manager #vacation #holiday #chill #dance |

| Suffering from WFH burnout? @TalentCulture offers some practical tips in this article, including initiating formal virtual #mentorship relationships and conducting weekly check-ins #WFH #burnout #HR #leadership https://t.co/0mPPPyvMx2 (accessed on 15 December 2022) |

| When the pandemic began, virtual meetings became all the rage. But soon, companies were holding too many meetings, and it led to “Zoom fatigue.” Gradually, people have realized that virtual meetings are not a panacea. Read more at https://t.co/734wqnzRBK #workfromhome #zoom (accessed on 15 December 2022) |

| These are rough times for workers & those running business. Here are the details of the income support & business support for those affected by lockdown. Thx @DanielAndrewsMP for securing this support for Victorians. #stayathome #GetVaccinated #springst #auspol #support #CovidVic https://t.co/9NLpvUaLb0 (accessed on 15 December 2022) |

| Feels like I am doing makeup more now, for zoom conferences, than when I actually worked in an office 😂😂 even life got weird or me 😂 #pandemiclife #workfromhome #workingremotely #conferencespeaker |

| Term | % | Frequency | Hashtag | % | Frequency | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | covid | 27.56% | 1,198,638 | #lockdown | 38.77% | 408,214 |

| 2 | covid19 | 20.86% | 907,130 | #stayhome | 33.38% | 351,445 |

| 3 | coronavirus | 19.65% | 854,450 | #stayathome | 15.36% | 161,771 |

| 4 | people | 4.48% | 195,033 | #workfromhome | 4.40% | 46,366 |

| 5 | pandemic | 3.72% | 161,591 | #remotework | 2.53% | 26,671 |

| 6 | deaths | 3.09% | 134,584 | #workingfromhome | 2.17% | 22,810 |

| 7 | virus | 2.87% | 124,834 | #remoteworking | 1.32% | 13,914 |

| 8 | health | 2.05% | 89,295 | #remote | 0.70% | 7398 |

| 9 | news | 1.91% | 83,028 | #workfomehome | 0.33% | 3497 |

| 10 | lockdown | 1.83% | 79,384 | #remotejobs | 0.16% | 1711 |

| 11 | world | 1.48% | 64,567 | #workathome | 0.15% | 1556 |

| 12 | work | 0.99% | 43,061 | #remoteworkers | 0.10% | 1022 |

| 13 | pandemia | 0.99% | 42,879 | #digitalworkplace | 0.10% | 1005 |

| 14 | home | 0.79% | 34,322 | #remoteworkforce | 0.09% | 969 |

| 15 | stay | 0.64% | 27,908 | #remoteworker | 0.06% | 640 |

| 16 | COVID_19 | 0.52% | 22,617 | #workingathome | 0.04% | 430 |

| 17 | school | 0.49% | 21,374 | #workoutfromhome | 0.04% | 426 |

| 18 | schools | 0.46% | 19,821 | #workoutathome | 0.04% | 401 |

| 19 | healthcare | 0.45% | 19,542 | #remoteworkvia | 0.03% | 320 |

| 20 | immunity | 0.44% | 19,013 | #remoteworkhttps | 0.02% | 222 |

| 21 | working | 0.43% | 18,820 | #digitalworkplaceday | 0.02% | 170 |

| 22 | workers | 0.40% | 17,589 | #remoteworkplace | 0.01% | 132 |

| 23 | community | 0.38% | 16,568 | #remoteworkinghttps | 0.01% | 122 |

| 24 | united | 0.37% | 15,943 | #remoteworkopportunities | 0.01% | 112 |

| 25 | worse | 0.36% | 15,708 | #workflowfromhome | 0.01% | 110 |

| 26 | lockdowns | 0.35% | 15,013 | #digitalworkspace | 0.01% | 92 |

| 27 | lockdown2 | 0.30% | 13,010 | #remoteworklife | 0.01% | 87 |

| 28 | covidiots | 0.24% | 10,500 | #remoteworkingapps | 0.01% | 56 |

| 29 | homes | 0.23% | 10,104 | #digitalworkforce | 0.01% | 56 |

| 30 | pandemic | 0.23% | 9975 | #remoteonlinejobs | 0.01% | 53 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Haque, A.; Singh, K.; Kaphle, S.; Panchasara, H.; Tseng, W.-C. Shifting Workplace Paradigms: Twitter Sentiment Insights on Work from Home. Sustainability 2024, 16, 871. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16020871

Haque A, Singh K, Kaphle S, Panchasara H, Tseng W-C. Shifting Workplace Paradigms: Twitter Sentiment Insights on Work from Home. Sustainability. 2024; 16(2):871. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16020871

Chicago/Turabian StyleHaque, Amlan, Kishore Singh, Sabi Kaphle, Heena Panchasara, and Wen-Chun Tseng. 2024. "Shifting Workplace Paradigms: Twitter Sentiment Insights on Work from Home" Sustainability 16, no. 2: 871. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16020871

APA StyleHaque, A., Singh, K., Kaphle, S., Panchasara, H., & Tseng, W.-C. (2024). Shifting Workplace Paradigms: Twitter Sentiment Insights on Work from Home. Sustainability, 16(2), 871. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16020871