Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic, which has affected the entire world, has not only created a number of emerging issues for each country, especially in the field of public health, but has also provided a number of opportunities for risk management, alternative strategies and completely new ways of looking at challenges. This brief report examines the COVID-19 pandemic response in Türkiye and the possible implications of the experience for future responses to other health emergencies and disaster risk management, based on the lessons learned. This study uses publicly available literature from government, private sector and academic sources to analyse the conflicts, changes and lessons learned during the COVID-19 pandemic, which are components of the World Health Organization (WHO) Health Emergency and Disaster Risk Management (Health EDRM) framework. The COVID-19 experience in Türkiye has several aspects, including the significant role of healthcare workers, the existence of an effective health system accustomed to emergencies, applications based on information technologies, the partial transparency of public authorities in providing information and a socio-cultural environment related to cooperation on prevention strategies, including wearing masks and vaccination. Challenges in Türkiye include distance learning in schools, lockdowns that particularly affect the elderly, ensuring environmental sustainability, hesitation about the effectiveness of social/financial support programs, the socio-cultural trivialisation of pandemics after a while and the relaxation of prevention strategies. Lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic include the value of transparency in public health/healthcare information, the strengthening of all aspects of the health system in terms of health workers and the importance of a balanced economy prepared for foreseeable risks.

1. Introduction

According to the Turkish Ministry of Health (MoH), the first COVID-19 case was identified on 10 March 2020, and the first death due to COVID-19 occurred on 15 March 2020 [1,2]. The first diagnosis and the first death that immediately followed caused a shock effect in the public and society in Türkiye, as in all countries. This situation was actually not surprising, but it was not clear when it would occur. It set in motion a process in which the authorities immediately took many measures, especially in the field of health management and public health. This was to be expected, as Türkiye is located at a major international transit point. Although various facilities to detect the disease were installed at the airports, the disease spread throughout the country in a very short time. Only two months after the first case, on 11 May 2020, the MoH stated that COVID-19 cases had reached 139,771, with 3841 deaths [3].

Although different waves of pandemics are defined all over the world, it cannot be said that this distinction is clearly made in Türkiye. Being one of the centres of international human mobility, it is possible that all the variants of the pandemic arose in different regions of the country [4]. Although the MoH had been transparent in sharing information and data for some time, it has not disclosed the numbers of COVID-19 cases and deaths since 27 November 2022. In this context, the latest figures are reported as 17,042,722 cases and 101,492 deaths due to COVID-19 in Türkiye [3].

At the beginning of the emergence of COVID-19 as a public health problem, the MoH formed an expert board. “The Coronavirus Scientific Advisory Board—CSAB” is a group of scientists (including experts from pulmonology, infectious diseases and clinical microbiology, as well as legal advisers, etc.) set up by the MoH to develop measures in the fight against COVID-19 to be imposed by the government [5]. The board is semi-scientific and semi-bureaucratic in structure; surprisingly, it was set up on 10 January 2020—before the World Health Organization (WHO) confirmed the pandemic in mid-March. This board served as a high-level advisory body in all government decisions related to the process. Türkiye has taken a number of public health measures, some of which are slightly different from those seen in the rest of the world (especially in Europe). First, Türkiye closed cafes and bars, cancelled events and meetings, and restricted flights. Then, the CSAB stated that public health interventions—such as lockdowns, filiation and mask use—had led to major drops in caseloads, reducing the strain on emergency rooms and intensive-care units [6]. This process continued with lockdowns, sometimes on weekends and sometimes on weekdays. The COVID-19 vaccination campaign in the country began on 14 January 2021; 85.7% of the population was fully vaccinated (two doses) by 8 October 2023 [7].

Many countries around the world have enacted similar processes, with similar responses and challenges in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic [8,9,10,11,12]. This study aims to examine Türkiye’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic, focusing on Health Emergency and Disaster Risk Management (Health EDRM), especially human resources, health services and public–social–technical logistics.

2. Materials and Methods

This is a grey literature review of publicly available information focused on Türkiye’s COVID-19 pandemic response.

2.1. Methods Setting

According to the key questions, the literature in Türkiye was hand-searched with terms such as “COVID-19”, “human resources”, “health service delivery”, “COVID-19 public health”, “pandemic management” and “pandemics response”, using the Google search engine, DergiPark, Web of Science, literature from the government and private sector, official documents, reports and academic papers from PubMed. Various documents, both in Turkish and in English—such as health-related guidelines set out by the MoH and official guidelines from the government, academic articles by researchers, documents from public institutions and academic societies, and news articles from December 2019 to October 2023—were investigated by document analysis and reviewed.

2.2. Literature Resources

In Türkiye, the responses to COVID-19 were mainly dependent on governmental policy; thus, we mainly focused on government materials. The latest official government documents from Türkiye, from before October 2023, were subjected to analysis. The governmental documents were mostly written by the MoH, but also the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Ministry of National Education, the Ministry of Labour and Social Security, the Ministry of the Interior, the President, etc. The main challenge was related to the frequently changing situation of the COVID-19 pandemic, which made it somewhat difficult to follow the articles and documents on COVID-19 responses. The literature that could be evaluated within the framework of the study was examined with a critical approach, and some documents/reports/news containing political arguments were systematised, excluded or used only for data within the scope of the study. Reports with verifiable data, such as vaccination rates, were included in the study. However, topics such as surgery and screening procedures/cancellations were excluded as they involved different and complex parameters, and were not directly included in the main scope of the study.

3. Results

The results are divided into three sections, each focusing on Health EDRM: human resources, health service delivery and logistics. Each section is subdivided into the relevant major sub-themes, and a summary of the findings is presented in Table 1 below. This section explains the issues related to the Health EDRM, and discusses each issue, including responses, challenges and opportunities for the COVID-19 pandemic.

Table 1.

Demonstration of domains and subgroups.

3.1. Human Resources

3.1.1. Medical Staff

At the beginning the COVID-19 outbreak in Türkiye, the idea that this issue was specifically a matter for infectious disease experts was widely accepted. This approach was the first major mistake made by society and the authorities in relation to the process. Inevitably, however, it was immediately realized that the oncoming problem was not that simple, and that we faced a multidimensional situation that concerned all areas of health [13]. In particular, the emergency departments where patients first entered were the units that played the most active role in the diagnosis of COVID-19 patients in Türkiye. One of the biggest advantages of this process is that Turkish people have a unique (and also somewhat problematic) mode of using emergency services. Emergency departments play an important role in the hospital-based healthcare system in the country. Although there are many factors, overcrowding in emergency departments is a serious problem [14,15,16]. However, this extraordinary situation means that the emergency department structure and emergency department personnel are used to overcrowding; thus, the increase in the number of patients in emergency departments during the pandemic did not affect the treatment/process too much [17].

Secondly, the management of the pandemic is not only related to physicians, but also nurses, prehospital emergency teams, intensive care personnel, hospital cleaning/hygiene staff, social workers, filiation staff, family physicians, administrative officials, etc. It is a complex system that requires many human resources. From this perspective, it appears that healthcare personnel, resources and distribution are sufficient in Türkiye [18]. However, the challenge in this regard is that the density of COVID-19 patients increases over time in cities, and it is difficult to immediately mobilize medical staff to meet the unexpected increases in certain centres. Because of the potential need for medical personnel during the crisis, the government has also mobilized some healthcare staff, and many routine medical practices in hospitals have been regulated (such as diagnostic procedures), postponed (such as elective surgical procedures) and restricted (such as outpatient consultation) [19].

In addition, as of 28 February 2022, 506 healthcare workers in Türkiye, including physicians, nurses and other healthcare workers, had died as a result of COVID-19 infection, according to the Turkish Medical Association [20]. This number indicates a problem that needs to be considered with regard to human resources in healthcare. However, there are sometimes numerical discrepancies between the MoH and the Turkish Medical Association in terms of the statistical data released about healthcare workers who were infected and died during the pandemic. The difference in numbers sometimes leads to a conflict about the reliability of the data.

Furthermore, the other challenge faced by medical staff was anxiety and stress due to the high risk of infection when providing healthcare to patients [21,22,23]. Ayaslier et al. found that physicians and nurses are affected by burnout in different ways under the conditions of the COVID-19 pandemic, based on gender, socioeconomic status and working conditions [24]. The high workload and stress affected both healthcare workers’ relationships with their families and their physiological state [25,26]. Although the government has taken some measures, such as additional financial payments, to overcome the troubles faced by medical staff, it could have taken more functional measures to address, in particular, the psychological impact of the pandemic on healthcare workers [27,28].

3.1.2. Education and Preparation of Medical Staff

Since the first outbreak of COVID-19, the WHO has recommended the development of country-specific operational plans for COVID-19 preparedness and response, or the adaptation of the existing Influenza Pandemic Preparedness Plan [29]. The Pandemic Influenza National Pandemic Preparedness Plan drawn up by the MoH was updated in 2016 in Türkiye, just before the COVID-19 pandemic [30]. Of course, COVID-19 is not caused by the influenza virus, but the main framework of influenza preparedness also provided the main framework of the COVID-19 pandemic response. It was thus an important opportunity to provide a strong response to the current pandemic [31].

The government dispatched physicians to pandemic epicentres, screening centres, airport quarantines, hospitals and intensive care units. In this context, on-the-job training was planned and implemented online and/or face-to-face, as soon as possible. Medical education curricula and programmes have been modified in response to the pandemic, and students in many medical schools have received training on prevention, treatment and vaccination [32,33,34]. When general lockdowns began across the country, health workers were undoubtedly affected [35]. In this regard, the MoH offered various accommodation options to doctors/nurses treating COVID-19 patients in hospitals.

The impacts of these initial responses set out by the public authorities to the pandemic have diminished over time, and their scope has changed or their effectiveness has diminished. Medical education in medical schools has occasionally been disrupted, sometimes leading to severe criticism from doctors [36]. Although not directly involved in pandemic-related health services, junior doctors (internship) were encouraged to participate in other ongoing health services. This approach was based on the view that it was a good opportunity for young doctors to learn the profession “in the field”. The risks and benefits of this approach may not have been adequately discussed within the community.

3.1.3. Supports to Medical Staff

Although there were short-term problems with issues such as the supply of masks and protective equipment in the early months of the pandemic in Türkiye, in general there were no serious problems with access to the equipment required to protect healthcare workers from infection [37,38]. The country seems to have strong infrastructure support in that respect. In particular, the provision of N95 masks to healthcare workers directly treating COVID-19 patients has been very successful.

Secondly, healthcare workers were given priority for COVID-19 vaccination in the country. This was an effective government policy, given the high risk of contamination and the priority for access to the vaccine amongst healthcare workers who were actively involved in the treatment process [39,40]. The prioritised vaccination of healthcare workers and the effective maintenance of this practice also benefitted perceptions and managed public attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccination.

Thirdly, from the outset, the MoH and other health authorities in Türkiye, in consultation with global health authorities, have produced Turkish guidelines for health professionals [41,42]. These have been updated from time to time [43]. These guidelines provided essential guidance to healthcare professionals, such that similar methods in the context of COVID-19 prevention and treatment could be implemented throughout the country. In this way, any doubts that might have arisen with regard to the treatments used have been minimised.

Fourthly, humanity’s instinctive solidarity in the face of disaster was also evident in Türkiye during the pandemic. Additional government-level allowances were paid to COVID-19 medical staff who were actively involved in the fight against COVID-19. In addition to the central government’s payments to healthcare professionals, local governments and bodies also took various initiatives to express gratitude to healthcare workers. On social media, television and billboards, many advertisements and “thank you” messages were shared (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The Municipality of Afyonkarahisar Province shares a message of gratitude to healthcare workers on billboards around the city. Mayor Mehmet Zeybek thanks the health workers for their great efforts and says: “They are working on a treatment for COVID-19; we are happy to have them. Thank you”.

3.2. Health Service Delivery

3.2.1. Hospitals and Intensive Care Units

According to MoH statistics, the number of hospital beds in Türkiye in 2020 was 251,182, and the number of intensive care unit (ICU) beds was 47,700. This means the country had a large number of beds, with 30 per ten thousand people and 39.1 ICU beds per a hundred thousand people, in 2020 [44]. However, in the case of COVID-19 patients, it was difficult to secure hospital beds because of the need for specialised conditions, such as a negative pressure room.

As COVID-19 requires specialised treatment, the ICU bed capacity is critical for all countries. Understandably, these costly structures were not widely included in pre-pandemic planning. The problem of there being insufficient beds across the country has been addressed by centralising bed monitoring, bed allocation and triage systems via a dispatch centre. In particular, the triage of ICU beds, which raises ethical concerns, has often become a serious issue.

Patients with mild symptoms were placed in self-quarantine, with medical staff monitoring them once/twice a day. In addition to the use of masks and attention to social distance, the use of some oral medications was standard practice for these patients [45]. The 112 emergency dispatch centres in Türkiye also played an active role in the co-ordination of patients, hospitals and intensive care facilities where there was a shortage of beds, as well as ambulance transport and patient allocation. It has become clear that the fight against the pandemic is not a process that can be carried out by qualified hospitals alone and that more complex mechanisms are required.

The main lessons learned were the importance of structural changes in hospitals and health facilities, the importance of designing hospitals with adequate space for triage and single rooms for isolation, and the importance of clean pathways [9].

3.2.2. Vaccination

For COVID-19 vaccination in Türkiye, healthcare workers and residents of long-term care facilities were prioritised, followed by high-risk individuals, other essential workers and the general public [46]. As of October 2023, over 85% of the Turkish population had received at least two doses [7]. Despite the fact that there is a serious issue concerning vaccine hesitancy in the country, such a high vaccination rate can be considered an achievement. This success was due to the fact that the MoH and other government officials were vaccinated on television at the start of the campaign, and positive propaganda about the vaccine was spread across all media platforms. As in many countries, reasons for hesitancy included concerns about side effects and vaccine safety, a lack of trust in institutions and the belief that vaccination against COVID-19 is unnecessary [47,48,49].

Initially, only Sinovac was used, but a variety of vaccines have since been used, most notably Pfizer-BioNTech and the nationally produced Turkovac. However, in Türkiye, as in the rest of the world, there has been a lack of vaccine efficacy studies comparing the effectiveness of different vaccines [7]. The lack of scientific evidence on this issue may also have been cited as a reason for vaccine hesitancy. There has generally been no problem with the supply of international vaccines to the country. However, it is noteworthy that the issue of national vaccine production has been advanced in a propagandistic context, including in Turkish politics [50].

3.3. Logistics

3.3.1. Public Logistics

The government has offered various forms of support, such as subsidies, tax breaks and economic incentives, to some sectors affected by the pandemic [51,52,53]. Many companies have experienced disruptions in their supply chains due to factory closures and reduced capacity [54]. For this reason, various alternatives have been suggested, such as flexible working models, working remotely and distance learning in educational institutions.

The COVID-19 pandemic was the first time that formal education was disrupted globally. Children in both developed and developing countries were unable to go to school. The development of the internet and network technology has enabled learners to study regardless of their location. Online learning has therefore been proposed as a plausible and effective alternative to face-to-face learning.

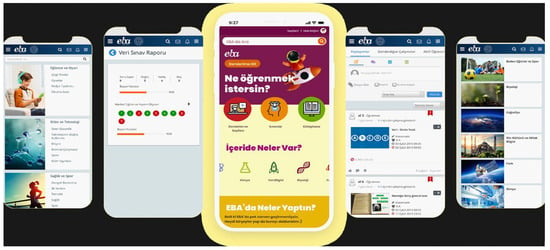

Although the Ministry of National Education closed elementary, middle and high schools for a while, it quickly introduced the distance learning system “eba” (Figure 2) [55]. For a long time, students continued their education through this system, using both television and the internet, and through various applications set up by their local schools. Issues such as the provision of both general and higher education through distance learning, and the efficiency and content of this education, have led to serious discussions across the country [56,57,58,59].

Figure 2.

Mobile app “eba” set up by The Ministry of National Education. eba, the digital education platform, is suitable for primary and secondary school classrooms. Students can access news, video, audio, visuals, documents and books at any time. This application, which has separate interfaces for students, teachers and parents, was widely used during the distance learning period. This application combines fun and educational elements for children; it is an iconic digital application of the pandemic period for children.

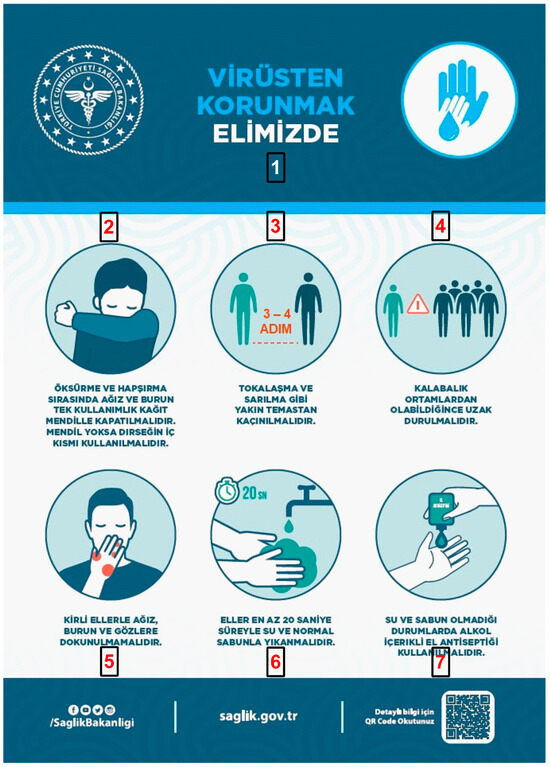

As personal protection, social distancing and hand washing are important in preventing the spread of the disease; the MoH has produced many warnings, informative publications, documents and announcements on these issues (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

An example of The MoH announcement on personal precautions against COVID-19. The English translation is; 1. Protecting from the virus in our hands, 2. Cover your mouth and nose with disposable paper tissues during coughing and sneezing. If there is no tissue, use the inner side of your elbow, 3. Avoid close contact such as handshaking and hugging, 4. Avoid crowded places as much as possible, 5. Do not touch your mouth, nose and eyes with dirty hands, 6. Wash your hands with water and regular soap for at least 20 s, 7. Use hand sanitizer if there is no water and soap.

3.3.2. Social Logistics

Immediately after the pandemic began, the government launched a campaign to provide free masks to all citizens [60]. However, this practice, which was an important exercise in public support in the beginning, was not successfully continued. Local authorities’ efforts to support food shopping, and the independence of the elderly and vulnerable, have not been successful enough. Various psychological and social support and rehabilitation activities were designed, especially for the elderly who were expected to be the most affected by the closure [61,62].

Surprisingly, artistic and literary activities and productions took on a unique form during the pandemic. Popular singers gave online concerts via social media and famous authors held book readings (Figure 4). Such activities were efforts to increase the sense of solidarity in society and were felt to partially reduce the effects of social isolation.

Figure 4.

Famous pop star Yalın gives a solo performance on Instagram at home.

In the midst of the pandemic, interest in issues related to narrative medicine increased in the country. In support of the healing function of narrative medicine, many books were published during the COVID-19 pandemic, written by both doctors and other individuals, describing their experiences [63,64]. Some initiatives organised storytelling competitions, open to everyone, for the sharing of COVID-19 experiences, maintaining the narrative tradition and proliferating the healing aspects of storytelling [65].

Another unexpected and surprising contribution came from religious institutions in Türkiye. The President of Religious Affairs called for prayers from the minarets of all mosques across the country after the night adhan for a quick end to the COVID-19 pandemic and for patients to be cured effectively [66]. This practice of collective prayer, which spread from loudspeakers to the streets, for a time stood as a symbolic and unique approach to social logistics, although it was discontinued after a short time.

3.3.3. Technical Logistics

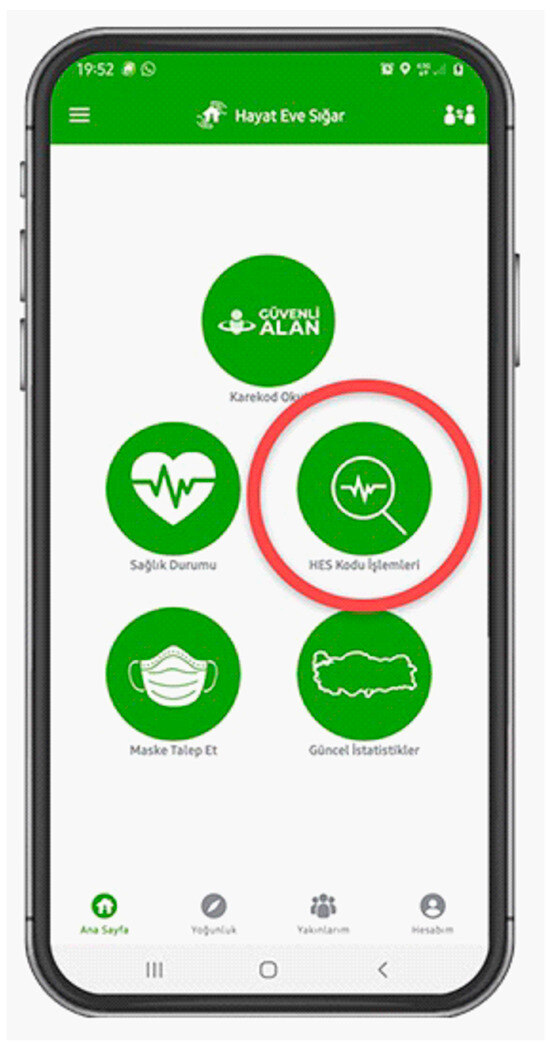

The pandemic has highlighted the importance of digital health records and digital data. A powerful dataset, both individual and social, has been created with the contribution of internet-based information technologies. Among these technologies, the most notable programme in Türkiye was the mobile application “Life Fits Home (HES)”, designed by the MoH, which was made available to all individuals (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

The screen of “Life Fits Home (HES)” app.

“Life Fits Home (HES)” is a mobile application developed by the MoH to inform and guide citizens living within the country’s borders about COVID-19, and to minimise the risks associated with the epidemic and prevent its spread. The application was offered by the MoH to all citizens, and it required verification with a phone number and the answering of questions in order to provide guidance in relation to coronavirus. This application, which also keeps personal health records related to COVID-19, also generates a code that citizens are asked to use during some of their travels and when entering some institutions, shopping centres, etc. Although this application was a unique tool that emerged during the pandemic, it also raised ethical debates about issues such as data sharing and personal privacy.

4. Discussion

4.1. Ethics

A wide range of ethical conflicts arose around the world during the pandemic, involving physicians, nurses, administrators and others. These (and undoubtedly other) issues can be identified under the following headings: mandating vaccination; triage, including ICU triage; justice; placebo-controlled trials of COVID-19 vaccines; clinical trials; health management, including honesty, trust, accountability and transparency; balancing the interests of patients and the entire community in relation to stay-at-home orders and social distancing requirements; the risks and anxiety levels experienced by healthcare workers related to heavy workloads, stress, risk of contracting infectious diseases, etc. [67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74].

The COVID-19 pandemic is demanding ethical reflections with new dimensions. During health crises, the need for ethical standards and accountability becomes imperative [75]. Healthcare providers, governments and policy-makers worldwide have a responsibility—a duty of care—to protect public health, and they are ethically required to focus on “the common good”. The pandemic has demanded difficult but unavoidable political and social decisions of ethical importance and complexity, involving many different sectors [9].

Ongoing ethical debates have become more visible since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, and new issues (such as curfews) have been added to these debates. Public health ethics has accordingly become a special issue, involving individuals beyond bioethicists and challenging decision-makers. The challenge is that decisions on ethical issues have to be made in a short time, and it is almost impossible to reach a consensus. Türkiye, along with the rest of the world, is encountering similar conflicts and discussions with regard to the pandemic and ethical issues.

With regard to the Health EDRM, the ethical lessons learned during the COVID-19 pandemic in Türkiye relate to core values such as transparency, accountability and trust; the difficulties in implementing equality and related concepts; and the need for policy decisions to be guided by ethical values with the broad participation of society. The CSAB scientific committee made very valuable steps in this regard in the country, but it was always questionable as to whether the committee included enough experts on the ethical and sociological dimensions of the pandemic. Addressing this is important because it can ensure that the same responses are deployed in similar crises in the future, and it will aid in the development of more comprehensive central decision-making mechanisms in the context of possible future disasters.

4.2. Vulnerability

It is well known that in some public health crises, vulnerable populations, due to their age, disability, gender, income level, etc., are much more exposed to adverse health effects than the general population. Considering vulnerability only in terms of health is definitely not sufficient; it should take into account the socioeconomic and cultural structures of these people. Vulnerability should therefore be considered as comprising different dimensions, such as health vulnerability (chronically ill or disabled people), social vulnerability (encountering disadvantages in the distribution of social services), economic vulnerability (low-income or dependent people) and institutional vulnerability (such as prisoners) [76].

Actually, when major global shocks occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic, people generally tended to become more vulnerable [77]. Increasingly, the conditions of social, economic and political hardship have a strong impact on individuals’ health, increasing physical vulnerability and thus the likelihood of disease [78]. The COVID-19 pandemic disproportionately affected certain populations and created conditions that either gave rise to new forms of vulnerability, or exacerbated existing ones. Strict quarantine measures placed vulnerable groups in a more precarious position, increasing risks and threats to their well-being [79]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, as stated above, vulnerable groups included not only the elderly, those with ill health and co-morbidities, or those who were homeless or unhoused but also people from a range of socioeconomic groups who may have found it difficult to cope with the crisis financially, mentally or physically [80]. Similarly, due to restrictions and the need for distance learning, children and health workers are also included in these groups, as they are at risk of illness/death and have lost many of their colleagues.

Firstly, the inequalities encountered by children during the distance learning period represented one of the most important issues during the COVID-19 pandemic in Türkiye; this issue was not sufficiently reflected in the government agenda. During the distance learning period, the main manifestation of vulnerability affected children who did not have the same equipment as other children in the classroom. It seems that the government has not made sufficient efforts in this regard. It was expected that the Ministry of National Education would put this inequality on the agenda when implementing and developing the distance learning model [81].

In addition, the elderly population was at a significantly higher risk of severe COVID-19 outcomes and at the greatest risk of mortality. Older people faced the most threats and challenges during the pandemic [82]. Amongst the elderly, several measures were taken, including social distancing, encouraging people to stay at home, cancelling mass gatherings, etc. [83]. All these restrictions, plus the fear/possibility of contracting the disease, have made the elderly in Türkiye vulnerable. Some polices and social packages were developed by the government for older people [61,84,85]. However, the effectiveness of these supports appears to be controversial, as they were mostly palliative and temporary.

Furthermore, COVID-19 patients face serious risks of vulnerability, including stigmatisation, from the beginning of the disease process to during and after their treatment by the healthcare system [86,87]. Similarly, the greatest risk of death in COVID-19, reflecting vulnerability, was among patients with chronic diseases and healthcare workers. The level of anxiety experienced by healthcare workers during the pandemic was the most important factor of their vulnerability in Türkiye [88]. Due to the high number of COVID-19 patients and their long shifts, physicians and nurses experienced anxiety, depression and poor mental health [89,90,91]. During the COVID-19 period, studies showed an increase in anxiety, especially among nurses in Türkiye [92,93].

In terms of the Health EDRM, the lessons learned about vulnerability during the COVID-19 pandemic in Türkiye included awareness, stress management skills, the importance of economic and social support, and solidarity. Although some of the measures taken by the government made a serious contribution, vaccination and support for vulnerable groups in particular could have been made more transparent at a level that would have satisfied the public. The pandemic period was a serious lesson for the government and decision-makers. It is hoped that this experience will improve preparedness for future crises.

4.3. Sustainability

As the COVID-19 pandemic caused involuntary and/or voluntary changes around the world, many governments and authorities, such as the WHO, adopted specific plans and strategies. Various psychological and social support and rehabilitation mechanisms/activities were implemented, especially for the elderly, children and vulnerable groups affected by the outbreak [94]. In addition to practices in the health sector, changes were also made in areas as diverse as education, the economy, working life, the environment, social life and risk management [86].

During this critical period, various practices were implemented in the country, mostly by public authorities. Community support was one of the most important elements in sustaining these practices. It was probably considered normal that some decisions were made quickly, and instructions were implemented immediately, due to the conditions of the pandemic period. However, participation in decision-making processes, the right to appeal and the transparent reviewing of the results of applications are now considered fundamental values of modern societies. These core values are also essential to the sustainability of these practices, particularly as regards environmental sustainability. The increase in the consumption of disposable materials and masks during the COVID-19 pandemic caused the pollution of the environment [95]. Looking at the Turkish example, there are aspects that can be improved in terms of community participation in decision-making.

The crisis preparedness of hospitals, intensive care units and the health system in general, as well as support for technical infrastructure and facilities, and the numbers and degree of training of health workers, are the most important achievements made in sustainable development during COVID-19 in Türkiye. This valuable experience made a positive contribution to the response to the 6 February earthquake, which occurred immediately after the pandemic and has been considered the largest disaster in the country’s history.

The foundation of sustainability is that people believe in this goal and its positive effects, i.e., they understand the importance of changing perceptions. In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, it can be said that Türkiye partially achieved this. For example, the distance learning model launched during the pandemic period has been expanded into a hybrid model, especially in higher education, throughout the country [96]. The above discussion shows that similar lasting changes were made in almost all areas where the pandemic has affected human life in Türkiye [97].

4.4. Management

In relation to the understanding of democracy and sociology in Türkiye, the word “management” primarily refers to the perceptions of the central government and its duties and responsibilities, hence the instinct to approach issues such as disasters, pandemics and risk management from a traditional, centralised perspective. The impact of this approach was seen in the country during the COVID-19 pandemic. Under this semi-structured system, where the main decision-maker was the government and the implementers of decisions were local authorities, some practices, such as curfews, were easily implemented without much objection from the public. Therefore, the discussions around the Health EDRM in Türkiye were mainly held through this framework.

In this context, issues such as contingency plans and risk management tend to be addressed from a centralised perspective, despite the contributions and efforts of local stakeholders. During COVID-19, strategies at the level of healthcare workers and organisation management were important, but system-level coordination is needed to support sustainability [98]. Thus, during the COVID-19 pandemic experience, many contingency plans announced in previous periods contributed significantly to Türkiye’s response. In particular, the contingency plans of the official institutions related to disaster and emergency management indicated comprehensive preparation [99]. These plans had been detailed, studied and, in some cases, tested against different scenarios, and they were an important guide, especially for health emergency management, during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, it is highly unlikely that any country can be totally prepared for a global severe pandemic.

In the run-up to the pandemic, various risk management and preparedness plans were drawn up by official, semi-official and NGO institutions, although they were not specific to the pandemic [100,101,102]. During the pandemic, awareness of the issue increased, and a wide range of action/management/risk plans were put in place [97,103,104,105]. Finally, it is essential that all these processes are carried out with ethical sensitivity in the future and that risk plans are developed with the participation and cooperation of practitioners in the field [106].

5. Conclusions

It may be concluded that the COVID-19 pandemic encouraged many necessary and unpredictable changes in Türkiye, as in all countries. Therefore, it made heavy demands on the government, individuals and society. Such responsibilities raised ethical issues in terms of public health, vulnerability, management, vaccination and environmental sustainability. On the other hand, they also had a positive effect in terms of raising public awareness of the issues, and creating a sense of social cohesion and collaboration. This positive effect was verified during the earthquake that shook eleven provinces on 6 February 2023 in Türkiye. However, there are still significant challenges to be met in ensuring that these ethical issues are addressed around the world and that lessons can be learned to control the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and future pandemics.

The COVID-19 pandemic had a devastating impact on the physical and mental health of all those involved, especially the most vulnerable and healthcare workers. This pandemic has been a difficult experience for humanity, with the complexities of treatment, vaccination, clinical trials, efforts made to limit the spread of the pandemic, economic, social and environmental impacts, and perhaps many other issues that have not yet emerged. Türkiye, in terms of its government and society, has also learnt various lessons from this complex and challenging experience, especially in the context of the Health EDRM. Some of these experiences can be successfully sustained, and alternative strategies can be developed, but others require more effort, awareness and a broader perspective in order to learn from.

Management issues related to the following three topics are the most striking learning points for Türkiye following the COVID-19 pandemic: human resources related to health workers and vulnerability; health service delivery related to hospitals, intensive care units, vaccination and triage; and logistics in the public, social and technical dimensions.

Funding

This study was funded by the World Health Organization Kobe Centre for Health Development (WKC-HEDRM-K21001).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Kisa, S.; Kisa, A. Under-Reporting of COVID-19 Cases in Turkey. Int. J. Health Plan. Manag. 2020, 35, 1009–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aykaç, N.; Yasin, Y. Rethinking the First COVID-19 Death in Turkey. Turk. Thorac. J. 2020, 21, 291–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Ministry of Health Current Status in Türkiye. Available online: https://covid19.saglik.gov.tr/TR-66935/genel-koronavirus-tablosu.html (accessed on 17 October 2023).

- Sirkeci, I.; Murat Yüceşahin, M. Coronavirus and Migration: Analysis of Human Mobility and the Spread of COVID-19. Migr. Lett. 2020, 17, 379–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yener, D. Türkiye’nin Koronavirüsle Mücadele Politikasına “Bilim Kurulu” Yön Veriyor; Anadolu Agency: Ankara, Türkiye, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cantekin, K. Turkey: Government Takes Extraordinary Administrative Measures for the Coronavirus Pandemic. Available online: https://www.loc.gov/item/global-legal-monitor/2020-03-24/turkey-government-takes-extraordinary-administrative-measures-for-the-coronavirus-pandemic/ (accessed on 17 October 2023).

- The Ministry of Health. COVID-19 Vaccination Information Platform—Last Report; The Ministry of Health: Ankara, Türkiye, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ghotbi, N. The COVID-19 Pandemic Response and Its Impact on Post-Corona Health Emergency and Disaster Risk Management in Iran. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamberti-Castronuovo, A.; Parotto, E.; Della Corte, F.; Hubloue, I.; Ragazzoni, L.; Valente, M. The COVID-19 Pandemic Response and Its Impact on Post-Corona Health Emergency and Disaster Risk Management in Italy. Front. Public. Health 2022, 10, 1034196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.P.; Hansoti, B.; Hsu, E.B. The COVID-19 Pandemic Response and Its Impact on Post-Pandemic Health Emergency and Disaster Risk Management in the United States. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Min, J.; Song, J.H.; Park, M.Y.; Yoo, H.; Kwon, O.; Yang, M.; Kim, S.; Lee, J.; Myong, J.P. The COVID-19 Pandemic Response and Its Impact on Post-Corona Health Emergency and Disaster Risk Management in Republic of Korea. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishimaru, T.; Shimizu, S.; Teshima, A.; Ibayashi, K.; Arikado, M.; Tsurugi, Y.; Tateishi, S.; Okawara, M. The Impact of COVID-19 Outbreak on Health Emergency and Disaster in Japan. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirbilek, Y.; Pehlivantürk, G.; Özgüler, Z.Ö.; Meşe, E.A.L.P. COVID-19 Outbreak Control, Example of Ministry of Health of Turkey. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 50, 489–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ülker, V.; Taşkın, H.C.; Yardımcı, N.; Hocagil, A.C.; Hocagil, H. Overcrowding Is Still a Big Problem for Our Emergency Services, Real Disaster Is in Our Emergency Departments in Turkey. Prehospital Disaster Med. 2017, 32, S32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erenler, A.K.; Akbulut, S.; Guzel, M.; Cetinkaya, H.; Karaca, A.; Turkoz, B.; Baydin, A. Reasons for Overcrowding in the Emergency Department: Experiences and Suggestions of an Education and Research Hospital. Turk. J. Emerg. Med. 2014, 14, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cakir, O.D.; Cevik, S.E.; Bulut, M.; Guneyses, O.; Aydin, S.A. Emergency Department Overcrowding in Turkey: Reasons, Facts and Solutions. J. Nepal. Med. Assoc. 2014, 52, 878–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çirakli, Ü.; Orhan, M.; Sayar, B.; Demiray, E.K.D. Impact of COVID-19 on Emergency Service Usage in Turkey: Interrupted Time Series Analysis. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2023, 18, 2105–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çınaroğlu, S. Distribution of Health Human Resources in Turkey in Provincial Level and a Need for More Effective Policy. Hacet. J. Health Adm. 2021, 24, 235–254. [Google Scholar]

- The Ministry of Health. Elektif İşlemlerin Ertelenmesi ve Diğer Alınacak Tedbirler; The Turkish Ministry of Health: Ankara, Türkiye, 2020; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Nesanır, N.; Bahadır, A.; Karcıoğlu, Ö.; Korur Fincancı, Ş. Pandemi Sürecinde Türkiye’de Sağlık Çalışanı Ölümlerinin Anlattığı; Turkish Medical Association (TTB): Ankara, Türkiye, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Selçuk, F.Ü.; Solak Grassie, S. Psychosocial Predictors and Mediators Relating to the Preventive Behaviors of Hospital Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Turkey. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2023, 65, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kackin, O.; Ciydem, E.; Aci, O.S.; Kutlu, F.Y. Experiences and Psychosocial Problems of Nurses Caring for Patients Diagnosed with COVID-19 in Turkey: A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2021, 67, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, M.K.; Aker, S.; Şahin, G.; Karabekiroğlu, A. Prevalence of Depression, Anxiety, Distress and Insomnia and Related Factors in Healthcare Workers During COVID-19 Pandemic in Turkey. J. Community Health 2020, 45, 1168–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayaslıer, A.A.; Albayrak, B.; Çelik, E.; Özdemir, Ö.; Özgür, Ö.; Klrlmll, E.; Kayl, İ.; Sakarya, S. Burnout in Primary Healthcare Physicians and Nurses in Turkey during COVID-19 Pandemic. Prim. Health Care Res. Dev. 2023, 24, e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batu, M.; Kalaman, S.; Tos, O.; Subaşı, H. Active Healthcare Professionals’ Perception of COVID-19 and Their Communication with Their Children: A Qualitative Analysis of the Background of the Pandemic. Türk. İlet. Araştırmaları Derg. 2021, 8, 35–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özlü, A.; Akdeniz Leblebicier, M.; Ünver, G.; Bulut Özkaya, D. Evaluation of Musculoskeletal Pain and Physical Activity of Health Care Workers Taking Part in the Covid-19 Pandemia. Kocatepe Med. J. 2023, 24, 105–111. [Google Scholar]

- The Ministry of Health. Sağlık Bakanlığına Bağlı Sağlık Tesislerinde Görevli Personele Ek Ödeme Yapılmasına Dair Yönetmelik; The Ministry of Health: Ankara, Türkiye, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Arık, Ö.; Aydoğdu, A. Investigation of Opinions of Health Staff about COVID-19 Additional Payment by the Ministry of Health. Int. J. Acad. Value Stud. (JAVStudies JAVS) 2021, 3, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). COVID-19 Strategic Preparedness and Response Plan: Operational Planning Guidelines to Support Country Preparedness and Response; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- The Ministry of Health. Pandemic Influenza National Preparedness Plan; The Ministry of Health: Ankara, Turkey, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kartoglu, U.; Pala, K. Evaluation of COVID-19 Pandemic Management in Türkiye. Front. Public. Health 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezircioğlu, I.; Dinç Horasan, G.; Seval-Çelik, Y.; Güner Akdoğan, G.; Hayran, M.; İnan, S.; Şemin, İ.; Dayanç, B.E.; Demir, A.B.; Abacıoğlu, Y.H. COVID-19 Pandemic Effect in Medical Education: “Izmir University of Economics Experience. Tıp Eğitimi Dünyası 2021, 20, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selçuk University. Faculty of Medicine Activity Report on Medical Education during Pandemic; Selçuk University: Konya, Türkiye, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Higher Education (YÖK). YÖK’ten Salgın Sürecinde Doktor Adaylarının Mezuniyetlerini Kolaylaştıracak Yeni Karar; General Secreteriat of Council of Higher Education: Ankara, Türkiye, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- The Ministry of the Interior. Koronavirüs ile Mücadele Kapsamında-Yeni Kısıtlama ve Tedbirler Genelgeleri; The Ministry of the Interior: Ankara, Türkiye, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Turkish Medical Association (TTB). Tıp Fakültesi Son Sınıf Eğitiminde Yaratılan Kargaşa Giderilmeli, Öğrencilerin Mağdur Olmaları Önlenmelidir; Statement of Turkish Medical Association (TTB): Ankara, Türkiye, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- (TEB), T.P.A. Maske Teminindeki Sorunlar Çözülmelidir. Available online: https://covid19.teb.org.tr/news/8833/Maske_Teminindeki_Sorunlar_Çözülmelidir (accessed on 17 October 2023).

- Asu, G.; Gemlik, H.N. A Qualitative Study on the Problems and Solution Proposals of Healthcare Employees in the Field during the COVID-19 Pandemic Process. J. Health Serv. Educ. 2020, 4, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kader, C.; Erbay, A.; Demirel, M.S.; Kocabiyik, O.; Ciftci, E.; Yalcın-Colak, N.; Unsal, G.; Eren-Gok, S. Evaluation of Attitudes and Behaviors of Healthcare Professionals towards COVID-19 Vaccination. Klimik Derg./Klimik J. 2022, 35, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sert Karaaslan, Y. Sağlık Çalışanlarına Yönelik Ilk doz Aşılamada Sona Gelindi; Anadolu Agency: Ankara, Türkiye, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- (TEB) Turkish Pharmacists’ Association. FIP Sağlık Danışmanlığı COVID-19 Kılavuzları; Turkish Pharmacists’ Association: Ankara, Türkiye, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- The Ministry of Health. COVID-19 Rehberi; The Ministry of Health: Ankara, Türkiye, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- KLIMIK—Turkish Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. COVID-19: Bilgi Notları ve Dernek Görüşleri; General Secreteriat of Turkish Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases: Ankara, Türkiye, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- The Ministry of Health. Health Statistics Yearbook—2020; The Ministry of Health: Ankara, Türkiye, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- The Ministry of Health. COVID-19: Temaslı Takibi, Salgın Yönetimi, Evde Hasta İzlemi ve Filyasyon; The Ministry of Health: Ankara, Türkiye, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- The Ministry of Health. COVID-19 National Strategy for the Implementation of Vaccines; The Ministry of Health: Ankara, Türkiye, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Haznedaroğlu Benlioğlu, E.; Bayrak Durmaz, S.; Göksal, K. COVID-19 Vaccination Hesitancy among Patients Admitted to the Immunology and Allergy Clinic with Drug Allergies. Health Sci. Q. 2023, 3, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, H. The Reasons for the COVID-19 Anti-Vaccine in Turkey: Twitter Example. Anemon 2022, 10, 579–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonmezer, M.C.; Sahin, T.K.; Erul, E.; Ceylan, F.S.; Hamurcu, M.Y.; Morova, N.; Al, I.R.; Unal, S. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Perception towards COVID-19 Vaccination among the Adult Population: A Cross-Sectional Study in Turkey. Vaccines 2022, 10, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erciyes University COVID-19 Aşı Yerli ve Milli Aşısı Hakkında. Available online: https://ikum.erciyes.edu.tr/tr/duyuru-detay/covid-19-asi-yerli-ve-milli-asisi-hakkinda (accessed on 17 October 2023).

- Official Newspaper. Bazı Alacakların Yeniden Yapılandırılması İle Bazı Kanunlarda Değişiklik Yapılması Hakkında Kanun; Türkiye, 2020. Available online: https://www.resmigazete.gov.tr/eskiler/2023/03/20230312-14.htm (accessed on 17 October 2023).

- Ergezen, A.K. Social Support Programs during COVID-19 Outbreak in Turkey. Gazi Med. J. 2020, 31, 322–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derneği, İ.H.; Dertli, N. COVID-19 Pandemisi Sürecinde Ekonomik ve Sosyal Haklar Raporu; Turkish Human Rights Association: Ankara, Türkiye, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bulut, H.G.; Demir, M. Social Support Polcies Applied in Türkiye during the COVID-19 Pandemin Process. J. Bus. Entrep. Res. 2022, 1, 36–47. [Google Scholar]

- The Ministry of National Education. Eba. Available online: https://www.eba.gov.tr/ (accessed on 17 October 2023).

- Boylu, E.; Isık, P.; Isık, Ö.F. COVID-19 Pandemic and Emergency Distance Turkish Teaching. Turk. Online J. Distance Educ. 2022, 23, 212–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Işık, O.; Tengilimoğlu, D.; Şenel Tekin, P.; Tosun, N.; Zekioğlu, A. Evaluation of Students’ Opinions Regarding Distance Learning Practices in Turkish Universities during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Yuksekogretim Derg. 2021, 11, 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alan, Ü. Distance Education during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Turkey: Identifying the Needs of Early Childhood Educators. Early Child. Educ. J. 2021, 49, 987–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaylak, E. Distance Education in Turkiye During the COVID-19 Pandemic: What Do Stakeholders Think? Turk. Online J. Distance Educ. 2022, 23, 65–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünal, E.C. Ücretsiz Maske Dağıtımında Başvurular E-Devlet Kapısı Üzerinden Alınacak; Anadolu Agency: Ankara, Türkiye, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Demirel, A.C.; Sütçü, S. Evaluation of Applications and Services for the Elderly during the COVID-19 Outbreak in Turkey. OPUS Int. J. Soc. Res. 2021, 17, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çimen, H. Rethinking the Importance of Social Assistance in Turkey During the Pandemic That Shocked the World (COVID 19). Anadolu Üniversitesi İktisadi ve İdari Bilim. Fakültesi Derg. 2021, 22, 15–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erbay, H. On Medical Ethics, Story and Narrating. Turk. J. Bioeth. 2017, 4, 29–35. [Google Scholar]

- Çamlıtepe, M. The Effect of Digital Technologies About Performing Arts and Music Practices in the Pandemic Process. Balk. Music. Art. J. 2022, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission. COVID-19 Stories, 1st ed.; Cander, B., Yakıncı, C., Eds.; Inonu University Press: Malatya, Turkey, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- The Presidency of Religious Affairs Prayers Rose from the Minarets. Available online: https://diyanet.gov.tr/tr-TR/Kurumsal/Detay/29429/minarelerden-semaya-dualar-yukseldi# (accessed on 17 October 2023).

- Largent, E.A.; Miller, F.G. The Legality and Ethics of Mandating COVID-19 Vaccination. Perspect. Biol. Med. 2021, 64, 479–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erbay, H. Herding Cats: Ethics in Prehospital Triage. Signa Vitae 2022, 18, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, A.C.A.X.; Paumgartten, F.J.R. Ethical Issues in Placebo-Controlled Trials of COVID-19 Vaccines. Cad. Saude Publica 2021, 37, e00007221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freckelton, I. Human Challenge Trials: Ethical and Legal Issues for COVID-19 Research. J. Law. Med. 2021, 28, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Öncü, M.A.; Yildirim, S.; Bostanci, S.; Erdoğan, F. The Effect of COVID-19 Pandemic on Health Management and Health Services: A Case of Turkey. Duzce Med. J. 2021, 23, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coccolini, F.; Cicuttin, E.; Cremonini, C.; Tartaglia, D.; Viaggi, B.; Kuriyama, A.; Picetti, E.; Ball, C.; Abu-Zidan, F.; Ceresoli, M.; et al. A Pandemic Recap: Lessons We Have Learned. World J. Emerg. Surg. 2021, 16, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yildirim, D.; Kocatepe, V. Professional Values and Ethical Sensitivities of Nurses in COVID-19 Pandemic. Nurs. Forum 2022, 57, 1111–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soylar, P.; Ulucan, M.; Dogan Yuksekol, O.; Baltaci, N.; Ersogutcu, F. Ethical Problems among Nurses during Pandemics: A Study from Turkey. Ethics Med. Public. Health 2022, 22, 100796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliyu, A.A. Public Health Ethics and the COVID-19 Pandemic. Ann. Afr. Med. 2021, 20, 157–163. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, S.Y.; De Foo, C.; Verma, M.; Hanvoravongchai, P.; Cheh, P.L.J.; Pholpark, A.; Marthias, T.; Hafidz, F.; Prawidya Putri, L.; Mahendradhata, Y.; et al. Mitigating the Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Vulnerable Populations: Lessons for Improving Health and Social Equity. Soc. Sci. Med. 2023, 328, 116007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, T.; Yang, L. Vulnerability and Fraud: Evidence from the COVID-19 Pandemic. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2022, 9, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girotto, S. Vulnerability and the COVID-19 Pandemic: Educating to a New Notion of Health. Int. J. Ethics Educ. 2023, 8, 291–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñalba, E. Pandemic and Social Vulnerability: The Case of the Philippines. In The Societal Impacts of COVID-19: A Transnational Perspective; Istanbul University Press: Istanbul, Türkiye, 2021; pp. 203–219. [Google Scholar]

- The Lancet Redefining Vulnerability in the Era of COVID-19. Lancet 2020, 395, 1089. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özer, M. Educational Policy Actions by the Ministry of National Education in the Times of COVID-19 Pandemic in Turkey. Kastamonu Eğitim Derg. 2020, 28, 1124–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Delivers Advice and Support for Older People during COVID-19. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/who-delivers-advice-and-support-for-older-people-during-covid-19 (accessed on 17 October 2023).

- Ilgili, Ö.; Gökçe Kutsal, Y. Impact of COVID-19 among the Elderly Population. Turk. J. Geriatr. 2020, 23, 419–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Ministry of Family and Social Services Engelli ve Yaşlı Gündüz Yaşam Merkezleri Yeniden Hizmet Vermeye Başladı. Available online: https://www.aile.gov.tr/eyhgm/haberler/engelli-ve-yasli-gunduz-yasam-merkezleri-yeniden-hizmet-vermeye-basladi/ (accessed on 17 October 2023).

- Demir, B.; Mandıracıoğlu, A. Discriminatory Practices towards the Elderly during the COVID-19 Pandemic and Assessment of the Situation on the Elderly People. Ege J. Med. 2021, 60, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyszyński, M.; Grudziński, M.; Pokonieczny, K.; Kaszubowski, M. The Assessment of COVID-19 Vulnerability Risk for Crisis Management. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 4090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaşar, Ö.; Avcı, N. Changing Elderliness Perception: The Elders Stigmatized By COVID-19. J. Turk. Stud. 2020, 15, 1251–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasu, F.; Öztürk Çopur, E.; Ayar, D. The Impact of COVID-19 on Healthcare Workers’ Anxiety Levels. J. Public Health 2022, 30, 1399–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokkaya, B.; Yazici, T.N.; Kargul, B. Perceived Stress and Perceived Vulnerability at Healthcare Workers during COVID-19 Pandemic. Clin. Exp. Health Sci. 2022, 12, 431–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onan, N.; Dinc, S.; Demir, Z. Pandemic Process from the Window of Healthcare Professionals. Value Health Sci. 2022, 12, 474–482. [Google Scholar]

- Keten Edis, E. Experiences of Intensive Care Nurses in the COVID-19 Process: A Qualitative Study. Gümüşhane Univ. J. Health Sci. 2022, 11, 476–486. [Google Scholar]

- Dincer, B.; Inangil, D. The Effect of Emotional Freedom Techniques on Nurses’ Stress, Anxiety, and Burnout Levels during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Explore 2021, 17, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murat, M.; Köse, S.; Savaşer, S. Determination of Stress, Depression and Burnout Levels of Front-Line Nurses during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2021, 30, 533–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahraman, B.; Uğur, T.D.; Girgin, D.; Koçak, A.B. COVID-19 Döneminde Yaşlı Olmak: 65 Yaş ve Üzeri Bireylerin Pandemi Sürecinde Yaşadığı Sorunlar. Hacet. Univ. Edeb. Fak. Derg. 2022, 39, 124–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurtsever, M. Short-Term Effects of COVID-19 Pandemic on the Environment. Uludağ Univ. J. Fac. Eng. 2020, 25, 1611–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Higher Education (YÖK). Yükseköğretim Kurumlarında Uzaktan Öğretime İlişkin Usul ve Esaslar; Council of Higher Education (YÖK): Ankara, Turkey, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ahsan, M. Strategic Decisions on Urban Built Environment to Pandemics in Turkey: Lessons from COVID-19. J. Urban. Manag. 2020, 9, 281–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimed-Ochir, O.; Amarsanaa, J.; Ghotbi, N.; Yumiya, Y.; Kayano, R.; Van Trimpont, F.; Murray, V.; Kubo, T. Impact of COVID-19 on Health Emergency and Disaster Risk Management System: A Scoping Review of Healthcare Workforce Management in COVID-19. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Ministry of Interior. AFAD-Strategic Plan 2019–2023; The Ministry of Interior: Ankara, Türkiye, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Commission Ethical Disaster Resilience for Our Global Community: Tenth Youth Looking Beyond Disaster (LBD19) Training Workshop-Istanbul. Available online: https://www.eubios.info/youth_looking_beyond_disaster_lbd/lbd10_istanbul (accessed on 17 October 2023).

- The Ministry of Health Pandemik Influenza Ulusal Hazırlık Planı. Available online: https://hsgm.saglik.gov.tr/depo/Yayinlarimiz/Eylem_Planlari/Ulusal_Pandemi_Hazirlik_Plani.pdf (accessed on 17 October 2023).

- AFAD Kahramanmaraş 2019 Ulusal TAMP Tatbikatı Gerçekleştirildi. Available online: https://kahramanmaras.afad.gov.tr/kahramanmaras-ulusal-deprem-tatbikati-gerceklestirildi (accessed on 17 October 2023).

- The Governorship of Osmaniye COVID-19 Pandemi Acil Durum Planı. Available online: https://osmaniyeisg.meb.gov.tr/meb_iys_dosyalar/2020_04/20115003_ACYL_DURUM_EYLEM_PLANI_COVYD_19-SON.pdf (accessed on 17 October 2023).

- Gürbüz, Y.; Şencan, İ. Pandemic Preparedness and Action Plan. Türk. Klin. J. Inf. Dis. 2010, 3, 40–48. [Google Scholar]

- The Ministry of Family and Social Services COVID-19 Pandemisi Yönetimi ve Eylem Planı Rehberi. Available online: https://www.csgb.gov.tr/media/68340/kiplas-covid-19-pandemisi-yonetimi-ve-eylem-plani-26022021.pdf (accessed on 17 October 2023).

- Mert, S.; Sayilan, A.A.; Karatoprak, A.P.; Baydemir, C. The Effect of COVID-19 on Ethical Sensitivity. Nurs. Ethics 2021, 28, 1124–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).