1. Introduction

The different experiences of living in quarantine because of the COVID-19 pandemic continue to change perceptions of the environment. Due to faster virus transmission, small and cramped spaces are no longer accepted [

1]. Ref. [

1] also pointed out that residential buildings should provide their residents with a minimum level of health and infection protection measures, such as the use of new non-contact technologies, proper hygiene to reduce the likelihood of infections, and the creation of greener and more intimate spaces that have a positive impact on relaxation and the maintenance of mental health. The need for a comfortable yet healthy living environment is certainly very important for both physical and mental well-being [

2,

3]. We must reflect on what is enduringly valuable to us and how certain things contribute to the overall meaning of our lives, but also how satisfaction is about our current emotional state, capturing how content or fulfilled we feel in the present moment. Both concepts are crucial for overall well-being and life satisfaction.

In a short time, the rapid spread of COVID-19 led people to spend more time at home to avoid possible infections [

4]. In most countries, public offices and educational institutions remained closed, forcing people to work and study from home. Both during and after the closures, most professionals and students were forced to work or study from home. The COVID-19 pandemic forced most people to be trapped in their homes and rearrange their spaces to meet multiple needs at the same time, including active work, physical activity, study, learning, relaxation, fun and so on [

1].

As a result, residential buildings and housing in general have become important critical infrastructure, essential for balancing these fragmented activities [

5]. Residential real estate thus takes on additional roles to ensure resilience and sustainability. Residential real estate is becoming more than just a place to live. Some authors state that the technological upgrading of residential real estate therefore plays a key role in coping with the new living environment created by the COVID-19 pandemic [

6]. Consequently, the current coronavirus pandemic forces us to rethink the value of existing buildings, which must become more resilient to other possible future epidemics/disease pandemics [

1]. The houses of the future must be able to answer the questions raised by epidemic measures, such as (1) how to sustainably and successfully prevent disease transmission, (2) how to maintain a healthy living environment, (3) how to maintain or further improve the comfort of all those who spend most of their time at home, (4) how to create the best possible conditions for working from home, and (5) how to maintain the satisfaction and well-being of users as much as possible.

We are interested in the following research question: (1) did residential property satisfaction change significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic? (2) What are the property parameters (referred to in the paper as “COVID”) that significantly affect the well-being of residents of residential properties during the COVID-19 pandemic? (3) What are the statistically significant differences in the demographic characteristics of the participants in relation to the “COVID” factors?

In this study, we are focused on investigating the parameters of the interior of properties.

The study was conducted in three phases. In the first phase, we reviewed the current literature that addresses the parameters of residential properties that most influence residents’ satisfaction with residential properties during the COVID-19 pandemic. These parameters represent the preferences of temporary residents or potential buyers of properties in the post-pandemic period. We have grouped these parameters into main factors. We refer to these factors as “COVID” factors. In the second phase, we repeated the survey on expressed satisfaction with general real estate factors that we had designed and used in previous studies in 2010 (details omitted for double-anonymized peer review). We compared the results from 2021 with those from 2010 and expressed the significant statistical differences according to the observed years, i.e., the year 2010 and the COVID-19 pandemic year 2021. In the third phase, we analysed the significant statistical differences related to the demographic characteristics of the participants according to the “COVID” factors. In this context, we interpreted the results. We believe that the answers to our research questions can help in the design of future sustainable and healthy housing. Urban planners and architects are among the first to respond to natural disasters such as floods, tsunamis, storms or hurricanes, earthquakes, fires or even wars [

1]. However, it is surprising that in the case of unpredictable disasters such as pandemics, the active participation of architects and urban planners is lower. The reason for this could be that the understanding of ‘disasters’ is limited only to physical natural/anthropogenic types of disasters that directly affect spatial changes [

7]. With our study, we turn to new solutions and ideas for the design of residential buildings under the dictates of pandemics.

In the future, it would make sense to expand the studies in this field to include living parameters, the building, the surroundings and the neighbourhood.

2. Residents’ Preferences for Housing Features during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Housing undoubtedly plays a significant role during the COVID-19 pandemic as it is a place where work, entertainment, learning, or relaxation are mixed daily. As such, housing is an integral part of the environment that is critical to health, well-being, social security, satisfaction, and quality of life in general [

8]. Some authors therefore recommend that the new knowledge gained from the COVID-19 pandemic, especially in relation to socio-economic factors, urban governance, and infrastructure factors, should be actively incorporated into the design of new urban housing [

9].

Ref. [

10] predicts that the design of buildings will change in many ways, especially in the direction of planning useful details. Ref. [

11] pointed out some key factors that should be given more attention in new design approaches: the promotion of self-sufficiency, inclusion of green spaces and quality of ventilation with better indoor air quality. Ref. [

12] points out that interaction with green spaces (balcony, terrace, atrium, garden) has a positive impact on people’s life satisfaction and well-being as they can grow food during self-care time, enjoy better air quality and have a sense of open space or unobstructed views. Ref. [

13] notes changes in the design of buildings in terms of ventilation and intimacy. Ref. [

14] expects changes in lightweight architecture and flexible building design. Living spaces could be functionally adapted quickly to new conditions, such as the need for solitude (isolation space). Based on a review of recent literature, [

1] highlighted the following parameters related to the residential property itself: personal comfort (personal space, outdoor space), cost of living (due to a sudden decrease in activities during a lockdown, housing costs increase) and local services (the lack of independent local shops and pharmacies could cause a crisis).

Many authors point out that as the need to work from home increases, the layout of spaces is likely to change, with more attention being paid to the design of convenient and private workspaces [

7,

12,

15,

16,

17,

18]. Intimacy and the difficulty of finding a private space during childbirth will shift the design of new homes towards more private spaces that allow everyone to have a personal space in the home [

14,

19,

20]. More attention is being given to the proper arrangement of workspace in homes. The organisation of spaces and the design of homes will change. Workplaces will be separated, well and comfortably equipped and naturally lit, with the possibility to regulate the dimming of the room [

1]. The sound insulation of the workplaces and, of course, technological equipment will also play a very important role [

7,

12]. However, for many people, it is difficult to find an isolated space for themselves when everybody is at home [

19]. The infamous flushing toilet in the background of the oral argument before the US Supreme Court underlined the dangers of inappropriate home-based workplaces. The growing number of home-based workers will challenge designers to balance the demands of the workplace with family privacy and security. It is indicated that that the assumption of being able to stay at home longer due to the COVID-19 pandemic will create new housing features that potential buyers will want. The coronavirus has triggered a home-working revolution that is likely to continue in one form or another even after the epidemic is over.

According to the same studies [

21,

22], there are two main reasons for this. The first is that employers can save on travel, overtime, and meals, as well as on smaller business premises and associated costs. In this way, employers save even if wages remain the same or even increase slightly. The second reason is that some employees want to work from home, as this lifestyle suits them better for various reasons. They have found that some companies have introduced work-from-home, but the rest of the facilities are temporarily closed. Office space rents have fallen dramatically and although it is now too early to determine how COVID-19 will affect office space use in the future, there is an emerging trend towards a decline in office space per employee [

23]. The working from home currently practised by companies is a factor that could change the behaviour of users in terms of demand in the office space market. This is due to the restrictions on home working, which may lead to a decrease in office space rentals in the future, exposing investors to risk [

24]. Public institutions such as churches that also conduct their services online might have fewer worshippers in their buildings than in the past. Schools are also working on institutionalising e-learning to reduce the number of students in classrooms [

25], which will also affect the use of school buildings. A workplace at home will not be just a desk and chair in the corner of the living room or in a dark part of the house. The workplace will be arranged in a separate, technologically equipped, naturally lit, comfortable room, which will be soundproofed and separated from children and pets. However, we must question to what extent the use of virtual technology can influence one’s investment in living space.

A study by [

26], which examined how the use of virtual technologies has increased and could change people’s behaviour, shows that usually, when people have access to virtual technologies, e.g., TV or smartphones, they spend more time stationed in one place. Due to the forced imprisonment during the COVID-19 pandemic, people found themselves in a situation where they were dependent on social networks, so communication channels of technology, such as high speed internet, become key factors of home equipment. Good communication technologies, such as high-speed internet with video connections, are therefore very likely to become essential housing equipment after a pandemic [

1]. However, this change in behaviour may change the need for housing. For example, office space is no longer needed for business that can be conducted online and virtually. The transition to the digital and virtual world is now more important than ever.

An important element is the so-called “mudroom”. This post-coronavirus room focuses on isolation, cleanliness, and prevention. We envision an impeccably organised space, with a full-size sink, storage space for disinfectants and, of course, a full complement of washing machines [

27]. The term derives from the functional design of farmhouses, as practically every farmhouse has a room next to the front door to store dirty shoes, clothes, sports equipment, and so on. During the COVID-19 pandemic, this type of room was very important in practically all houses, whether it was a farmhouse or a flat in the city. It is basically a decontamination room where people can disinfect themselves (e.g., hands) and where potentially infected items such as clothes, food bags, mail, etc., can be stored. The popular trend of open living space in recent years is also changing, so there will be no more combining a central living room, kitchen and dining room in one. The pandemic dictates a different design and therefore in the future, the space will be partitioned into separate rooms, for example, the entrance space will be separate and will represent the dividing line between the outside world and home, in terms of hygiene, shoe storage, clothing and things connected directly with the street [

28].

Ref. [

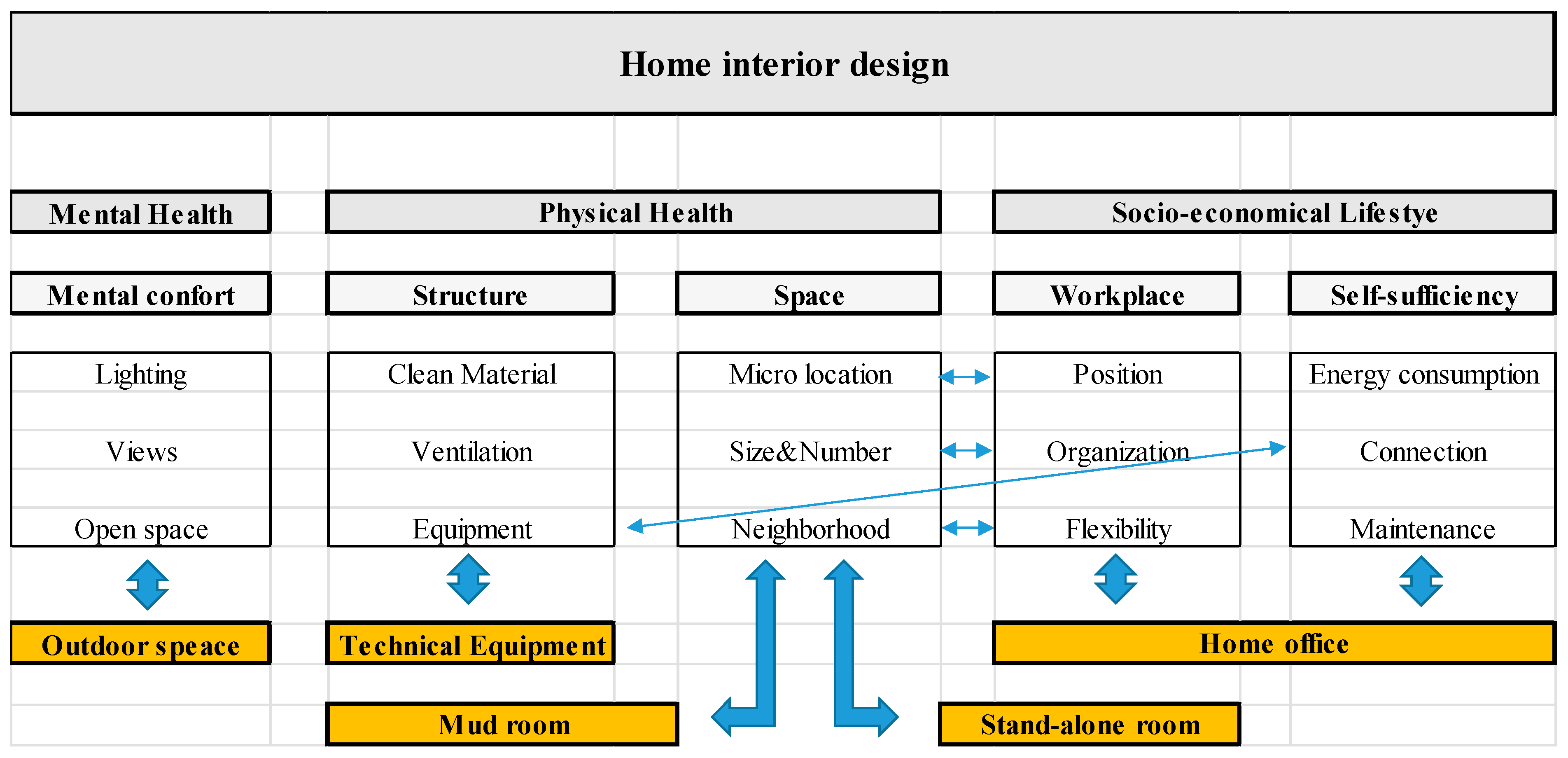

29] emphasized that the research so far has extracted three meaningful components of a healthy home: comfort, structure and equipment, and space (

Figure 1). The comfort parameters of lighting [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34] and air quality [

33,

35] were considered. Technical conditions [

32], heating and ventilation systems [

33,

35] and material [

32] are parameters of structure and equipment. Room size [

32,

34], privacy [

33,

35], private outdoor space or balconies [

31,

33], spatial organisation [

33,

35], green spaces [

31,

35] and adaptability [

31] were studied as spatial parameters.

According to a study by [

36], in the dramatically changed world of 2020, the ideal shared flat is no longer a cosy flat close to an underground or train station, which were once the most popular features. Now, it is a spacious property (38%), a garden or balcony (30%), less than a 10-min walk to a large green space (53%), half an hour from the great outdoors (22%) and within 10 min of a supermarket (53%). According to [

29], these dimensions could be grouped and evaluated into five categories: mental comfort, structure of building, space, workplace, and self-sufficiency.

The classification of the criteria related to the interior of the house, which formed the basis for the questions in this study, is shown in

Figure 2, according to what was mentioned above.

Figure 2 shows the grouped reference factors, which we refer to as “COVID” factors and which represent the preferences of residents in terms of housing features during the COVID-19 pandemic.

According to apartment users, during the COVID-19 pandemic, the most important factors proved to be the possibility of setting up a home office, the internet, the possibility of installing a mudroom, a separate space and contact with nature, which could include a balcony, terrace, atrium or just good natural lighting and ventilation space. Ref. [

37] pointed out that interest in gardening and urban farming—hobbies—has increased. People may not have had the time to pursue these hobbies with the fast pace of life they had lived before the pandemic [

37].

When choosing, buying, or renting a house, people always look for the most suitable place [

29]. Therefore, housing preferences are important for designers, planners, and sociologists. Housing preferences reflect the mental and ideal conceptions of individuals and show what can happen. Therefore, it is preferences that determine a person’s goals when choosing a house [

38].

3. Method

The main instrument used to measure participants’ satisfaction was a questionnaire from our previous study in 2010 (details omitted for double-anonymized peer review). The questionnaire was validated in two phases. First, a factor analysis of the questionnaire and a reliability analysis of the questionnaire (Cronbach’s alpha) were performed. Descriptive statistics and analysis of variance followed. A five-point Likert scale was used, where a value of 5 expressed complete agreement with the statement and a value of 1 completely disagreed with the statement.

The questionnaire combines physical factors, environmental factors, and socio-economic factors. Physical factors characterize the physical characteristics of the property (micro location of the apartment, size, presence of terrace or balcony, lighting, noise, age of the building, parking, technological equipment), environmental factors are significant for the neighbourhood (proximity to vital facilities, schools, hospitals, police, accessibility and transport links) and socio-economic factors concern the user (sense of belonging to the neighbourhood, quality of neighbourly relations, sense of security, sense of belonging to economic status, maintenance costs) (details omitted for double-anonymized peer review). The questionnaire includes 34 variables. Eight factors were extracted that explain more than 60% of the variation [

39]. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin sampling rate is 0.7 and the Bartlett test (BT = 2178.1), which is statistically significant, shows that the excluded factors can be interpreted [

40]. The reliability of the questionnaire, determined by the internal consistency method or the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, shows that the questionnaire has high reliability. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the questionnaire is 0.8. In the first survey in 2010, 1006 Slovenian participants actively participated, and in the repeated survey in 2021, 716 Slovenian participants were recorded. The structures of the demographic characteristics of the participants in 2010 and 2021 are shown in

Table 1.

We are aware that the characteristics of the participants may influence the results. Therefore, we pay attention to the demographic differences between participants in 2010 and in 2021, but do not specifically address these influences in our study. How these observed demographic differences between the 2010 and 2021 participants might influence the results is the subject of further research. In 2021, compared to 2010, more participants were older than 41 and more participants lived in rural areas. We can see significant differences between participants in terms of home ownership. In 2021, there were more participants who are homeowners than in 2010. We explain this mainly by the fact that most participants in 2021 (in contrast to participants in 2010) live outside urban centres, where, as is typical for Slovenia, most properties are individual, owner-occupied houses [

41]. On the other hand, many participants in 2021 are men, who anecdotally own homes at a higher percentage than women (details omitted for double-anonymized peer review). In terms of the participants’ level of education or the monthly use of their funds to meet housing needs, we find no significant differences between the participants in the different times periods observed.

4. Results and Discussion

Statistically, the results were analysed by analysis of variance, which is often used in research as a statistical method to compare the average of three or more groups. The year of observation was chosen as the dependent variable, i.e., 2010 and 2021 in relation to the living conditions in the property (satisfaction with current living conditions, physical characteristics of the property, proximity to important access points, maintenance costs, unneighbourly relations and sense of security and belonging to the neighbourhood). The results are shown in

Table 2.

Interestingly, the results show that statistically significant differences between the observed year 2010 and 2021 are expressed mainly in terms of the living conditions in the property, which is associated with expressed satisfaction with living conditions, natural lighting and airiness, proximity to key infrastructure, maintenance costs and a sense of belonging to the neighbourhood.

Regarding satisfaction with their current living conditions, participants in 2021 expressed higher average agreement (1.71) than participants in 2010 (1.36). This result is somewhat surprising, but we explain this mainly by the fact that in Slovenia, the proportion of homeowners is high [

41]. Research shows that a high share of owner-occupied housing has a positive effect on the expressed satisfaction of housing users (details omitted for double-anonymized peer review). The study by [

42] examined the social benefits of homeownership and found that, compared to renters, homeowners express greater satisfaction with their living environment, are more socially active in their living environment, move less, and contribute more to the social stability of the neighbourhood. The survey found that 86 per cent of respondents in the US believe that owning a home is better than living in a rental property from a social security perspective. In addition, 74 percent of respondents believe that people should buy a home as soon as they can afford it. However, of the respondents who live in rented accommodation, 64 per cent answered that they only live in rented accommodation because they cannot afford to own their own home [

42]. They found that levels of satisfaction were higher among homeowners [

43]. Self-satisfaction was defined as a combination of general satisfaction with life and satisfaction with their living conditions and neighbourhood [

43]. From this, we conclude that a high percentage of home ownership has a positive effect on the satisfaction of the participants (the percentage of home ownership in Slovenia is over 80%).

Regarding satisfaction with brightness, participants in 2021 expressed higher average agreement (natural lighting; 4.29) than participants in 2010 (4.12). During the pandemic and probably long after, many people will work from home. However, according to Statistics Norway, not all employees rate their work efficiency from home as worse [

44]. Although the pandemic clearly meant an upheaval for the home office, many employees returned to work after the closure. According to the Mannheim Corona study [

45], the percentage of employees working from home in Germany was 28%, slightly lower than during the quarantine period—even without activating the back-to-office strategy. Therefore, it is crucial to understand the potential downsides of the home office and take measures to minimize these impacts [

46]. Lighting is an area that is often not thought about [

47]. The most significant issues in home workplaces include temperature, air quality, lighting, and noise conditions [

48]. The increase in home working certainly means that these are precisely the problems that are at the forefront. This is also confirmed by the participants of 2021 with great agreement.

On the other hand, participants in 2021 expressed lower average agreement with the proximity of kindergartens and schools (3.91), opinions about jobs (3.11) and health centres (3.55) than participants in 2010 (4.11, 4.02 and 3.79). As a result of COVID-19, several countries have taken local or national measures, even lockdowns, since the start of the pandemic in 2020. One of the most important measures taken during the lockdown was the closure of schools, educational institutions, and other public institutions [

49]. Given the technological tools available today, such as the internet, telephone and television, new methods of learning have developed, such as distance learning [

50]. Building maintenance is closely related to essential functions that ensure the building’s original intended performance, its safety, and the quality of life of its occupants [

51]. Participants in 2021 expressed lower average agreement regarding satisfaction with maintenance costs (3.42) than participants in 2010 (3.59). The results are explained by the fact that people spend more time at home, which in turn is reflected in operating costs (mobile or landline costs, internet costs, personal computer or table, software, or hardware for teleconferencing) and in the long run in material wear and tear (computers, printers, other equipment). Participants in 2021 expressed higher average agreement with the sense of belonging to the neighbourhood (3.65) than participants in 2010 (3.48). This new situation as a result of the crisis and social chaos created by the pandemic COVID-19 has led to a very rapid neighbourhood response in many cities, as evidenced by the activation of mutual support and solidarity by the state [

52]. Ref. [

52] identified parallels between the 2008 crisis and the 2012 austerity period, showing that neighbourhood and citizen creativity is an important driver and multiplier of social change, providing empirical evidence that could also be recognised in the context of a pandemic. This is also confirmed by our findings, with participants expressing through a higher level of expressed satisfaction in 2021. It is important that when a need is met (e.g., shopping), social relationships and social capital are strengthened at the same time, increasing territorial belonging to the neighbourhood and district. In this way, strengthening ties to the community acts as a method to reduce social vulnerability (health, economic, social, and interpersonal) that can be caused by total isolation [

52].

We suspect that these differences are mainly due to the occurrence of the COVID-19 pandemic, which had a strong impact on all of us. We therefore analyse in more detail the influences of factors in the post-pandemic period, as shown in

Figure 1. Statistically significant differences in age, residence, and ownership of real estate property and “COVID” factors in the post-pandemic period are shown in

Table 3.

There are statistically significant differences regarding the possibility of walking access to vital facilities according to the age of the participants, with the highest average value of agreement expressed by the youngest participants (4.43), and the lowest by the middle generation (2.15). For the home office option, the percentage of average agreement increases with the age of the participants. The highest average agreement is expressed by participants aged 41 and over (3.87). A similar observation is also made regarding technological equipment (3.85) and a separate room (4.13).

A series of studies show large differences between age groups in the impact this pandemic has had [

53]. Research shows that older age has a strong influence on the seriousness of risks regarding specific jobs, the possibility of increased unemployment and poor chances of re-employment, negative perception of the experience of working from home and early retirement [

54]. On the other hand, the same study shows that younger age groups faced greater job insecurity and negative stereotypes towards older workers, which triggered tensions and deterioration of communication. Our findings confirm this issue, which is why we believe that even more attention should be paid to it in the future.

Depending on the place of residence, all observed factors show a statistically significant difference in relation to the “COVID” factors. The expressed level of satisfaction with access to vital facilities (access by foot) is significantly more reflected in urban centers (4.28) than in rural areas (2.67). The opposite applies to the expression of feelings about the cleanliness of users or the environment. Here, residents of urban centres voluntarily give a significantly lower mean value (3.59) than residents of scattered rural areas (4.50). In terms of technological amenities, residents of scattered rural areas report a higher level of agreement (4.5) than participants living in urban centres (3.46). Participants living outside the centers also express a higher average agreement regarding satisfaction with the accessibility of space to retreat (4.50), while participants living in the centers express a lower average agreement (3.58).

Regarding property ownership, all observed factors show statistically significant differences from COVID-19 factors. Regarding the ability to reach important facilities on foot, on average, property owners stand out (3.97), in addition to tenants stand (3.18). The same is reflected in the feeling of cleanliness (4.08), the home office (3.94) and the quality of technical equipment (4.19). For all of these parameters, the level of agreement of owners is significantly higher than the level of agreement of real estate tenants. In summary, the result shows that the highest agreement on walking distance to important facilities by age and property ownership is expressed by the youngest participants and those who live in the city centre. In terms of cleanliness, the highest average agreement is expressed by those living outside the city centre and property owners. Regarding the furnishing of the home office (and technical equipment), the highest average agreement is expressed by older participants, participants living outside city centres and property owners. Regarding the mudroom and the detached room, older participants, participants living outside city centres and property owners express the highest agreement.

Table 4 shows the correlations between age, place of residence and property ownership and COVID-19 factors.

The results show the correlation between age and the ability to reach vital objects on foot (*). In addition, researchers [

53,

55] have pointed out that cities are expected to shift from cars to more walking and cycling, which is both environmentally friendly and beneficial to citizens’ physical and mental health. There is also a slightly stronger correlation between age and having a home office, good technical equipment, and self-contained space (**). There is little research on the impact of working from home, partly because working from home was rare until this spring. There are correlations by home location with walking distance, perception of cleanliness, home office, technical equipment, and self-contained space (**). There are correlations by ownership, perception of cleanliness and single room (**). If you live with elderly parents or children who do not understand the concept of ‘working from home’, you may want to live alone instead (details omitted for double-anonymized peer review). While the appeal of an open-plan living concept will most likely never disappear, we predict isolated spaces separated from common areas. As the whole family spends more and more time at home working, going to school and pursuing hobbies, personal space will become a must [

45]. There is also a correlation with technological equipment (*), which is to be expected given the importance of internet connections at the time of the pandemic.

Striking a balance by aligning our activities and relationships with long-term meaning and immediate satisfaction can contribute to a more fulfilling and balanced life. By expressing the level of satisfaction with the observed “Covid factors”, the participants also express the importance of their presence. If we can incorporate elements into our lives that are both meaningful and fulfilling, we are more likely to experience holistic well-being. The correlation shows that both concepts are crucial for overall well-being and life satisfaction.

5. Conclusions and Recommendation

Today, we know from experience that various forces such as natural disasters, climate change and, finally, human intervention in nature and its habitats can also cause pandemics in the future. It is therefore crucial that we develop effective weapons based on the already identified patterns and dynamics of pandemics to be prepared for rapid and effective responses and to adapt when and if necessary [

56]. For example, it was the social distancing necessary to contain the spread of SARS-CoV-2 that created an unforeseen natural experimental environment that can be used to identify the disaster and misery to which the entire population was exposed [

56]. However, the lessons learned during the current COVID-19 pandemic are a great opportunity to use them to plan sustainable housing policies that are more equitable, sustainable, and naturally resilient to such phenomena. This is followed by the future design of working environments, workplaces, time flexibility of working hours, organisation of work from home and, more generally, creating conditions for working from home for as many people as possible [

57]. The home is becoming more than just a living space. This paper addresses the following research questions: (1) Has residential real estate satisfaction changed significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic? (2) What are the real estate parameters that significantly influence the satisfaction and well-being of residential real estate users during the COVID-19 pandemic? (3) What are the expectations for the design of future residential properties considering the COVID-19 pandemic?

The main instrument used to measure participants’ satisfaction was a questionnaire from our previous study in 2010. The participants expressed as the most important “COVID” factors the possibility of setting up a home office, good technological equipment in the flat, the possibility of setting up a mudroom, a separate, independent space and contact with nature, which can include good natural lighting and ventilation. The results show that the expressed statistically significant differences between the year 2010 and 2021 in terms of living conditions in the property are expressed in satisfaction with their current living conditions, brightness or natural light, proximity to kindergartens, schools, work opinions and health centres, maintenance costs and sense of belonging to the neighbourhood. We suspect that these differences are mainly due to the occurrence of the COVID-19 pandemic, which had a major impact on all of us. In the study, we filtered out key factors that had a decisive influence on residents’ satisfaction with their property during the COVID-19 pandemic. These factors are the possibility of setting up a home office, good technological equipment in the property (internet), the possibility of setting up a mudroom, a detached space, and the possibility of contact with nature and natural lighting and ventilation. These factors are called “COVID” factors. Statistically significant differences were analysed in relation to age, place of residence and property ownership and “COVID” factors. The results showed that the highest average agreement in terms of walking distance to important facilities by age and property ownership was expressed by the youngest participants and those living in city centres. In terms of cleanliness, the highest level of agreement was expressed by those living outside town centres and property owners. Regarding the home office facilities (technical equipment), the highest level of agreement was expressed by older participants, participants living outside city centres and property owners. Regarding the concept of a clean room and rest room, the highest agreement was expressed by older participants, participants living outside city centres and property owners.

We believe that the answers to our research questions can help in the design of future sustainable and healthy housing. We argue that such studies are very important for both researchers and planners of spatial and housing policies. We hope that reading this article will provide investors with an idea of the fundamentals of the property market and the longer-term dynamics that the pandemic will leave behind. Our study investigates the parameters of the interior of properties, so in the future, it would make sense to expand the studies in this field to include living parameters, the building, the surroundings and the neighbourhood. Our study investigates the impact of the real estate COVID-19 factor on the expressed satisfaction of residents during the COVID-19 pandemic. In the future, it would be very interesting to observe what changes the post-COVID-19 period will bring.

Future scenarios regarding the possible upcoming new pandemics may not be very precise, as we need to be aware that the behaviour, spread and consequences left behind by the existing coronavirus are still the subject of research and explanation [

1]. The fact is, however, that humanity should be prepared for possible recurrent COVID-19 outbreaks or similar pandemics. That is why it is crucial to understand the importance of creating scenarios that are based on the facts revealed so far, and based on which we can develop resilient solutions. Such models are underused today but are an essential part of future planning [

51].

COVID-19 has dramatically changed housing policy in much of the world. Good housing has proven to be the foundation of strong communities. Understanding this gives our study a special significance.