Abstract

The fluctuating conditions of Lake Limboto have greatly affected the activities of people living around the lake. The shallowing and narrowing of the lake poses a significant problem to local people’s survival. The lake is predicted to disappear by 2030, which will consequentially lead to a diminishment in the productivity of the lake. This article aims to analyze how the communities around the lake respond in their daily activities to the transformation of the lake and the shocking prediction about its lifespan. This study uses an interdisciplinary approach by integrating multiple fields of study to understand and address the problems regarding this issue. This research comprised a literature review, field survey, and in-depth interview process around the lake. This research relied on the framework of cultural studies to analyze the survival and resilience of the people around the lake, gaining an understanding of their special daily activities. The results of this study show that some people are aware of the lake’s gradual recession, but they have not prepared for it, treating the problem as only a government affair. They continue to live at the lake’s shores, enduring even amidst impoverished conditions.

1. Introduction

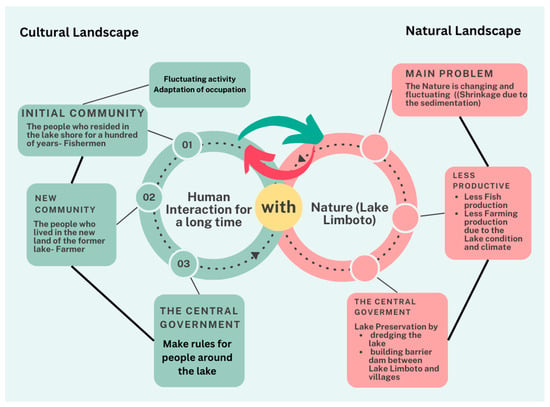

This article covers the following three topics: culture, human interaction, and nature. How the three are related and interact is important because changes and movements occur in these three things. Human interactions are always in motion, and so is culture. Culture is dynamic; it always changes [1]. Culture and human interaction with nature form cultural geography over a long period of time [2]. However, the idea of place or nature is commonly viewed as immovable, and this is problematic. Nature is considered a medium of culture which a cultural landscape produces [2], in other words, something passive. There are cultural dimensions that interact in the space of a landscape; however, despite this, nature is always seen as a neutral factor [3]. This is a critical problem because, in fact, nature and the environment are also subject to changes. This is especially true in the case of Lake Limboto, where nature constantly moves and changes.

Accordingly, the concept of landscape shaping culture, and on the contrary, culture also shaping the landscape should be considered. The idea that nature and culture are not related is the subject of criticism among cultural experts because natural landscapes shape how humans carry out activities, and in reverse, human activity influences landscapes. Humans are not just performing physical activity in a place: they also think and arrange their social lives based on the conditions in which they live. When the nature or environment where humans live changes drastically, humans must adapt, change their way of thinking, and rearrange their social lives.

In the case of Lake Limboto, we observed that from time to time the activities of people around the lake have been fluctuating depending on the lake’s circumstances. Most of the people around the lake are no longer dependent on fishing as their main source of income because the conditions of the lake are increasingly deteriorating. However, even should they have other jobs, they still occasionally go fishing on the lake, despite knowing that they would not acquire much.

The current condition of Lake Limboto is not as picturesque as in the historical documents of the Dutch and in the oral stories of the people of Gorontalo. Over the course of several centuries, the lake has seen significant transformations. Nowadays, people around the lake are confronted with numerous problems because of the condition of the lake, and these changes in environmental circumstances have resulted in changes to the activities of the people around Lake Limboto. The employment situation of the area is also changing over time: in the past, the majority of males in that particular region were engaged in the occupation of fishing. Gradually, they have been transitioning their occupations to various sectors, including agriculture and transportation, such as farmers and bentor (local public transportation) drivers, or other forms of employment that can sustain their livelihood. The condition of the lake is becoming ever the more critical, with some geologists and environmentalists even having indicated that the lake will disappear around 2025–2030 [4,5].

Based on the above issues, we can ascertain that the people living around the lake area are confronted by multiple problems, including those both environmental and socio-cultural in nature. It could therefore be said that socio-cultural problems evolve in line with the changing condition of the lake and vice versa. In light of this, our research aims to uncover how the people in the lake have maintained their lives so far, based on on-site observations, also supported by historical documents, oral stories, and accounts of the socio-cultural practices of the local community residing near the lake. Additionally, this study seeks to assess the reactions of the surrounding communities to this specific environmental phenomenon. This research is expected to provide information on how the people around the lake have anticipated and prepared for the increasingly critical lake conditions, how they will survive these changes, and how resilient they are in improving their living conditions. Also, this research is expected to act as an academic paper that records the activities of the people around the critically endangered Lake Limboto.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Study Area

Lake Limboto is located in Gorontalo Province, on the northern peninsula of Sulawesi Island. It is between 00°33′03″ and 00°37′00″ north latitude and 122°56′37″ and 123°00′57″ east longitude [4]. The area of the lake occupies two administrative areas, approximately 30% of the Gorontalo City area and 70% of the Gorontalo Regency area. The water of Lake Limboto comes from rainwater that falls directly into the lake and the 23 rivers that flow into the lake, including the Aloe, Marisa, Meluopo, Biyonga, Bulota, Talubongo, Pohu, and Ritenga rivers. The longest rivers are the Alo Molalahu River (348 km) and the Pohu River (156 km). The only river that flows all year is the Biyonga River. Nevertheless, the Biyonga River has a weak current and it covers a relatively small area of 68 km2. This river is the smallest tributary that flows into Lake Limboto [4,6,7].

Lake Limboto is regarded as one of the lakes that is considered to be in the most critical condition in Indonesia. It is difficult to determine which is the main cause of the lake’s shallowing, whether it is solely due to sedimentation or due to human activity. Nevertheless, according to Putra [5], the sedimentation actually began to occur several million years ago and has accelerated in recent times. Accordingly, the sedimentation began first, but the acceleration of sedimentation may be due in part to recent human intervention. This shallowing is a result of lake sedimentation coming from rivers as well as sedimentation caused by human activity patterns around the lake [8,9]. In this context, it is evident that the reduction in the depth of the lake is attributable not just to natural processes but also to human interactions with the environment. These two things are interrelated, resulting in complex problems.

Various factors associated with natural phenomena might contribute to the shallowing of the lake, such as sedimentation and rainfall, among others [4,9,10]. Apart from this, other factors related to human activities contribute to the shallowing of the lake, such as cultivation efforts and tree-cutting activities in the forests of the upper reaches of the Limboto watershed, which act as an area of water catchment [5,11]. Local people’s activities around the lake relate to the longstanding practice of shifting farming. As a result, environmental degradation occurs and directly impacts the waters of Lake Limboto, such as shallowing and eutrophication which occur as a result of increasing nutrients from the disposal of fish feed from aquaculture activities which were thrown into the lake, water hyacinth, etc. [12], and the discarding of pollutants into the lake’s water body. Accordingly, it has been concluded that the waters in Lake Limboto have been polluted on a variety of different levels, although heavy metal pollution is still within normal limits [12]. This condition is worrying for the sustainability of the lake and fish production from the lake, especially considering the fact that this fish is traded to the public. Moreover, the part of the lake that had dried up is now used as a residential area [13].

At the same time, socio-cultural research about humans’ activities around the lake was also carried out by socio-cultural researchers, who tried to unravel the complexity of the problems that caused the lake to become increasingly shallow. According to Hasim [13], one matter that contributes to this complexity is the regulations of government policy about natural and environmental resource management. The spatial planning of the lake area in particular and the region in general often ignores aspects of the principle of harmony of spatial functions.

Junus and Mamu [14] arrived at the same conclusion as Hasim that spatial planning policies, especially in the lake area, are unsatisfactory. Also, the management network of adaptive governance in Lake Limboto is considerably weak [15], with illegal residential development on the banks of the lake resulting in impacts upon the lake’s current ecosystem. The large number of residential buildings scattered across the areas alongside the lake area are generally permanent or semi-permanent. With the rapid growth in population, the need for land is growing based on community expectations, leading to an increase in the importance of the position of land ownership rights, especially with regard to the dried-up land along lake shores.

Sarson, who conducted research in the field of law studies, explained that Lake Limboto area is an open area [15]. Since the area of Lake Limboto is open, it has experienced a process of continuous exploitation of an excessive nature, which does not pay attention to aspects of its preservation. As a result of the silting of Lake Limboto, most of the areas around it have turned into lake settlements or have been converted into agricultural businesses. In accordance with the national land law, land arising due to the shallowing (aanslibbing) is designated as land directly controlled by the state, meaning that anyone who wishes to perform activities on the surfacing land (aanslibbing) must obtain prior permission from governmental authorities, namely the National Land Agency. In spite of this, the majority of the people who live and have built settlements on the lake shores do so without permission from the government. This is due to the fact that the land has been used as a dwelling place since the 1980s, with the land being passed down from generation to generation.

From the various studies above, both in the natural sciences and socio-cultural sciences, we can understand the complexity of the problems in Lake Limboto. The problem of lake shallowing goes hand in hand with socio-cultural problems. Regarding the socio-cultural side, we observed that the majority of people who live on the edge of the lake do so in an attempt to maintain their livelihoods in a struggle for survival. They choose to live on the edge of the lake because this area is productive, fertile, and free, and also because there are few other places to take up residence. However, most of them do not realize the consequences of the potential outcome that the water of this place they depend on may disappear. Accordingly, this research seeks to analyze this relationship between the environmental phenomena taking place and the socio-economic circumstances of the people residing around the lake in poor conditions.

The purpose of this literature review is to define the research’s perspective, focusing on socio-cultural problems in a rapidly shifting environment. It is necessary to explain both natural and socio-cultural changes. Although, as previously stated, such studies have already been conducted, little attention has been paid to research that attempts to examine socio-cultural changes that arise from natural changes. This study aims to make this relationship clear.

2.2. Cultural Studies

In the context of this study, the people of Lake Limboto experienced two pressing conditions: natural deterioration and the threats this poses to socio-economic and cultural circumstances. The lake has reached a critical condition, by which most of the people around the lake can no longer carry out lake fishing activities, because many species of lake fish have become extinct; furthermore, the land around the lake is continually drying up. This poses a threat to both their lives and culture.

This study is conducted under an interdisciplinary framework with an emphasis on culture studies. Cultural studies observe and criticize cultural movements that cannot be separated from historical, social, political, and economic contexts [16]. However, cultural studies also study cultural geography, in other words, the connection between culture and geography. The geographical circumstances of where humans live has a large impact on the human activities that ultimately shape their culture [2]. Research within a framework of cultural studies is needed to examine phenomena related to issues of place and humans. Cultural studies also examine culture in relation to power [17]. Researchers in the field of cultural studies believe that culture moves not in a vacuum, and that there is power that makes culture move and develop which is inseparable from the historical, social, political, and economic context. Power in this case is not necessarily limited to that of the government and political regulation, but can also take the form of ideology that can drive culture [2,16,18]. Cultural studies also examine cultural geography. Cultural geography concerns humans and nature within particular regions over long periods of time [2]. Climate change, which has seen worsening symptoms in the last few decades, is occurring at a fast pace, with the environmental damage resulting from natural disasters causing significant transformations to the order of human life. At the same time, alterations in human activities as a result of changing needs also leads to transformations in the natural environment. This, in turn, shapes cultural geography. Therefore, developments in culture are not only inseparable from the historical, social, political, and economic context, but also from place or geography.

In the frame of cultural studies, this study seeks to reveal how a place provides a connotative meaning to the people who live there, as well as assess their reactions when this place undergoes changes. As stated by Giles and Middelton, what cultural geography does is focus on the context from which such connotations arise [17]. It is concerned with teasing out the way in which places and spaces are shaped by and can themselves come to shape the beliefs and values of those who inhabit them. Cultural geography, then, is concerned with the real social practices that take place in historically dependent and geographically unique situations in order to form and reproduce cultures. This idea is pertinent to the people around Lake Limboto because they actively shape their way of life based on the lake’s changing course.

3. Research Method and Data Source

This research employed an interdisciplinary method, which involves the integration of many academic disciplines to comprehensively comprehend the phenomena in the field. This research emphasizes qualitative research which relies more on interpretation of literature data and field data to use as arguments.

3.1. Literature Research Method and Field Investigation Method

The research was conducted from October to December 2022 through the literature study method and the field investigation method. The literature study method included books, old travel literature, oral stories, analysis of papers, news reports, and old collections of pictures related to the study area. This study explored old documentation describing the lake from Von Rosenberg’s [19] travel reports, oral stories, historical picture collections, as well as old maps of the lake to support the interpretation and argumentation of the field research relating to area history.

Field investigation methods included field trips and interviews. In-depth interviews are needed to obtain an overview and understanding of how the community is trying to survive in light of the lake’s critical condition and how the community deals with its impoverished circumstances, while also providing insights into the oral history of the area. The interviewed people were main informants, namely hailing from the sub-district or village government, and the residents around the lake. The interviewed respondents totaled around 102 people from all the villages that were surveyed. In addition to the research from the literature, we took pictures of villages during the interviews and also took pictures from above the villages and the lake with a drone.

3.2. Charts and Figures

Despite the fact that this study also makes use of charts and figures, these only serve to clarify the data that the field research’s findings provide. Tracing the way of life of the community and how they deal with the threat of disasters is very important. For this purpose, this research involved many parties in interviews, including both the community around the lake and the governmental staff at the sub-district and village levels.

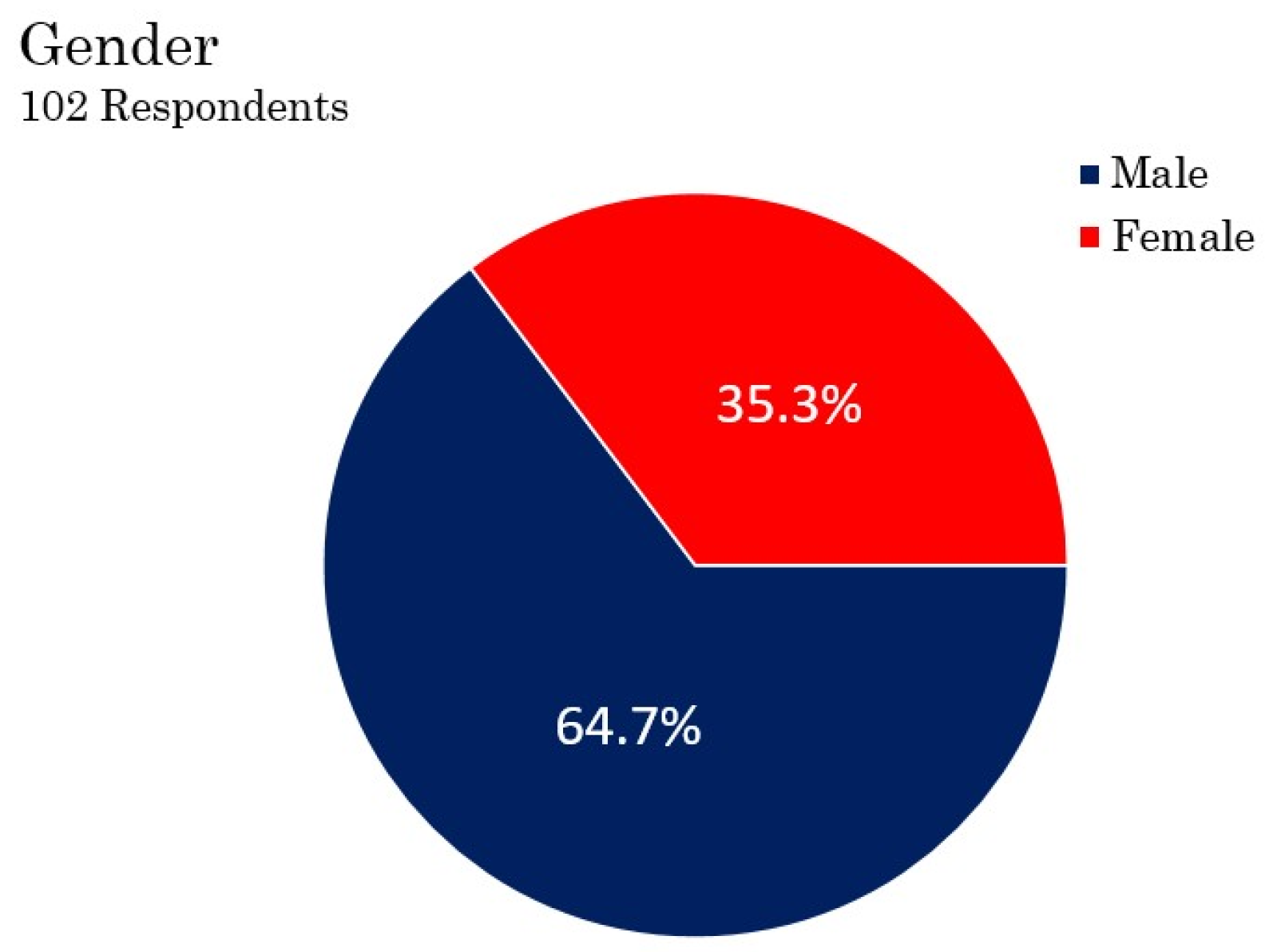

Interviews were conducted with 102 informants in 27 sub-districts and villages to find out the fluctuation in activities of the people caused by the changing circumstances of the lake, which is becoming narrower and shallower. The diagrams above show the gender of the respondent or informant who was asked about their situation. In Chart 1, most of those interviewed were men, as much as 64.7%, while women accounted for 35.3%. This happened because the researchers did not pre-determine the gender of the interviewees; the interviewees were sampled randomly to obtain information on what activities the informants would carry out if they experienced conditions that threatened their survival around the lake.

Chart 1.

Gender of respondents.

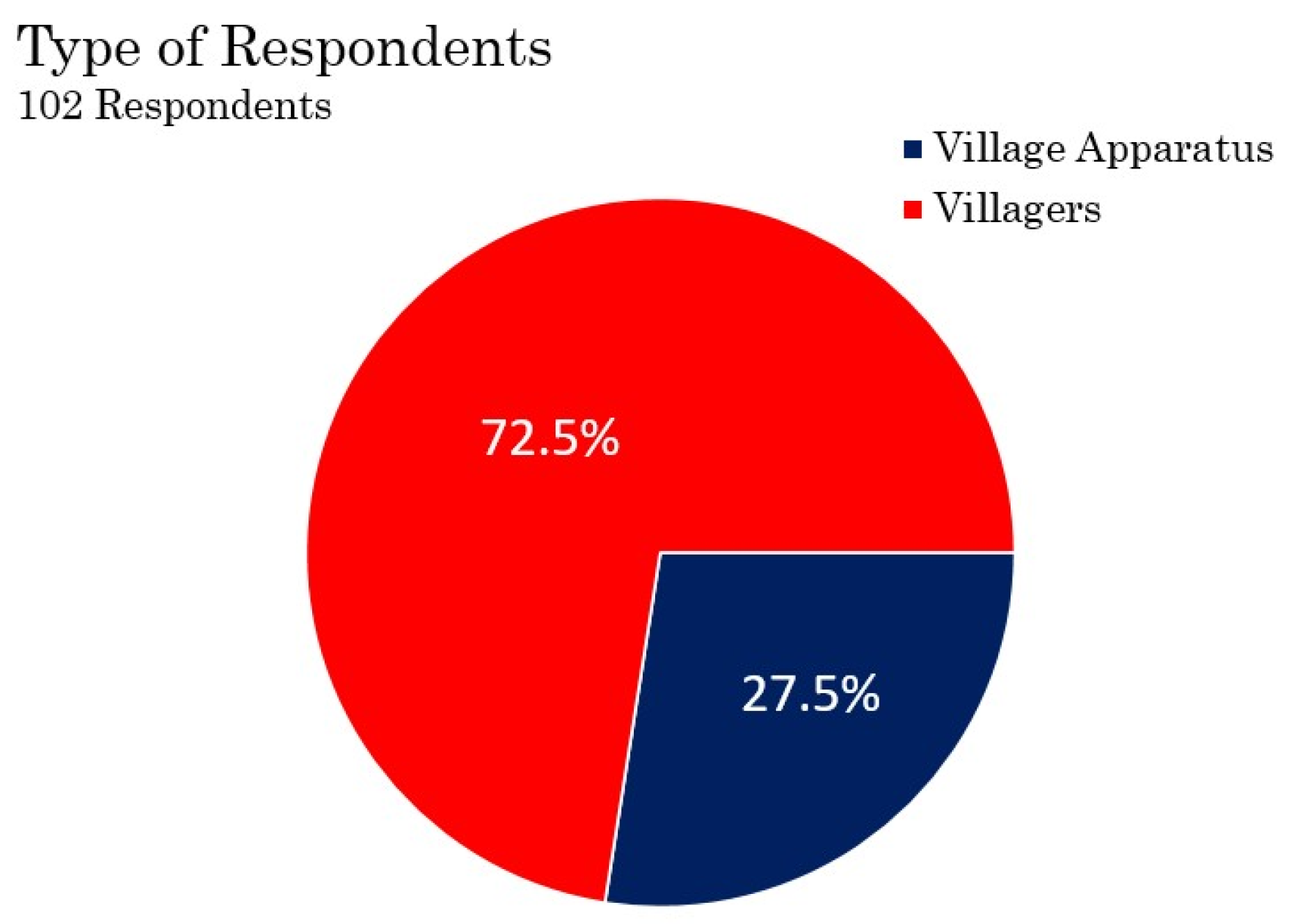

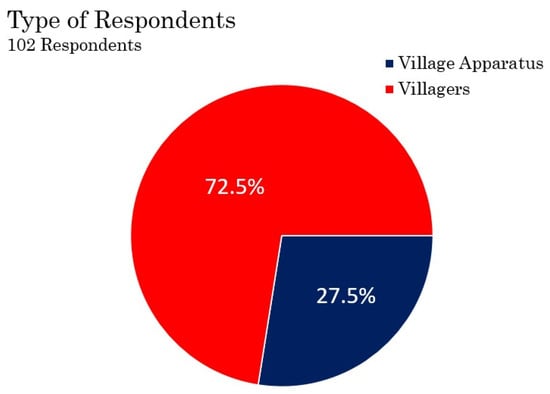

The type of informant, however, was deliberately determined because the information was extracted starting from the main informants, namely village officials who know about village developments and the condition of the lake, as well as the regional government policies in anticipating the condition of the lake, which have an impact on the circumstances of the people around the lake. In Chart 2 below, 27.5% of informants were village officials, while the remaining 72.5% consisted of the community. The community was interviewed to ascertain their preparedness towards the worsening lake situation.

Chart 2.

Type of respondents.

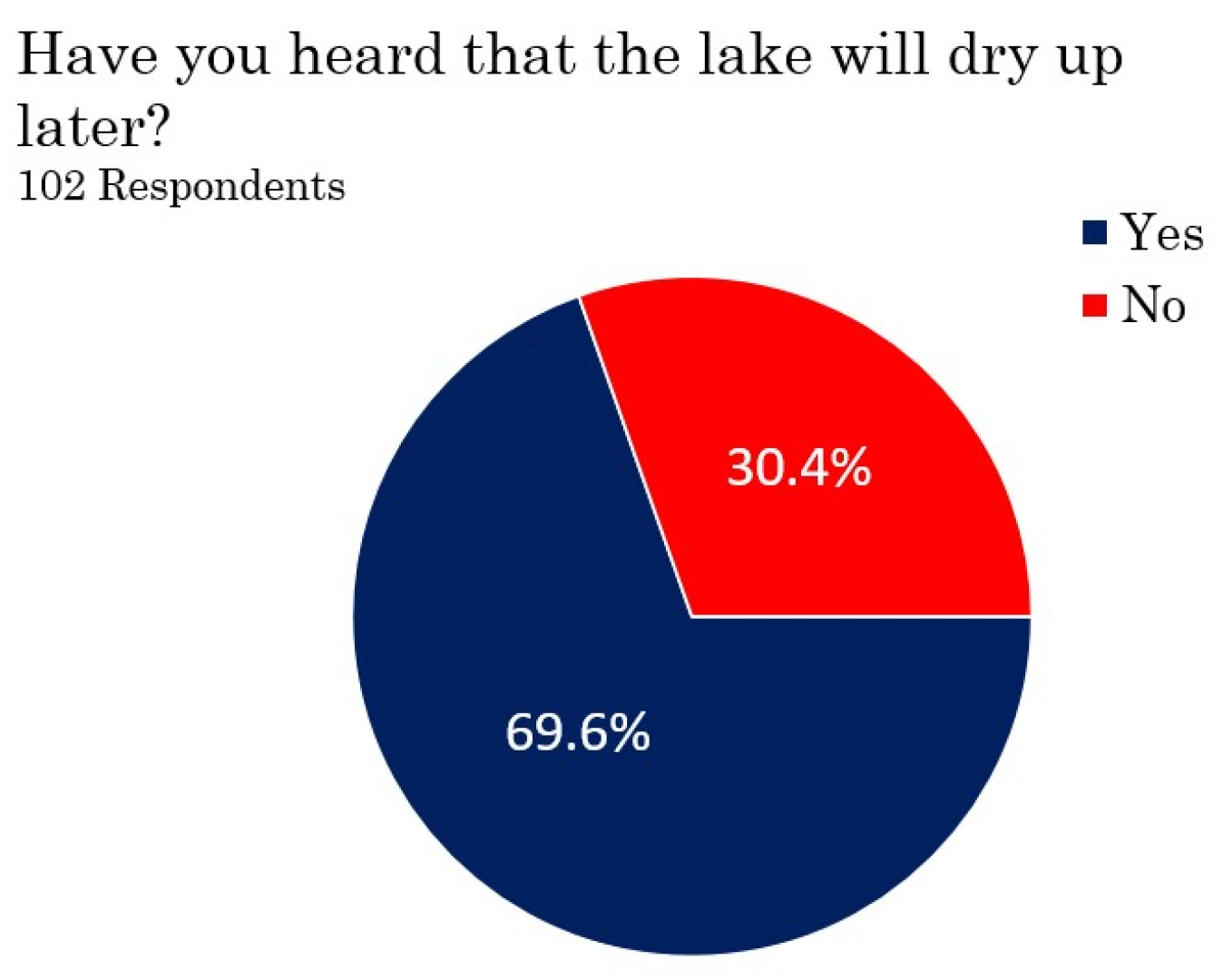

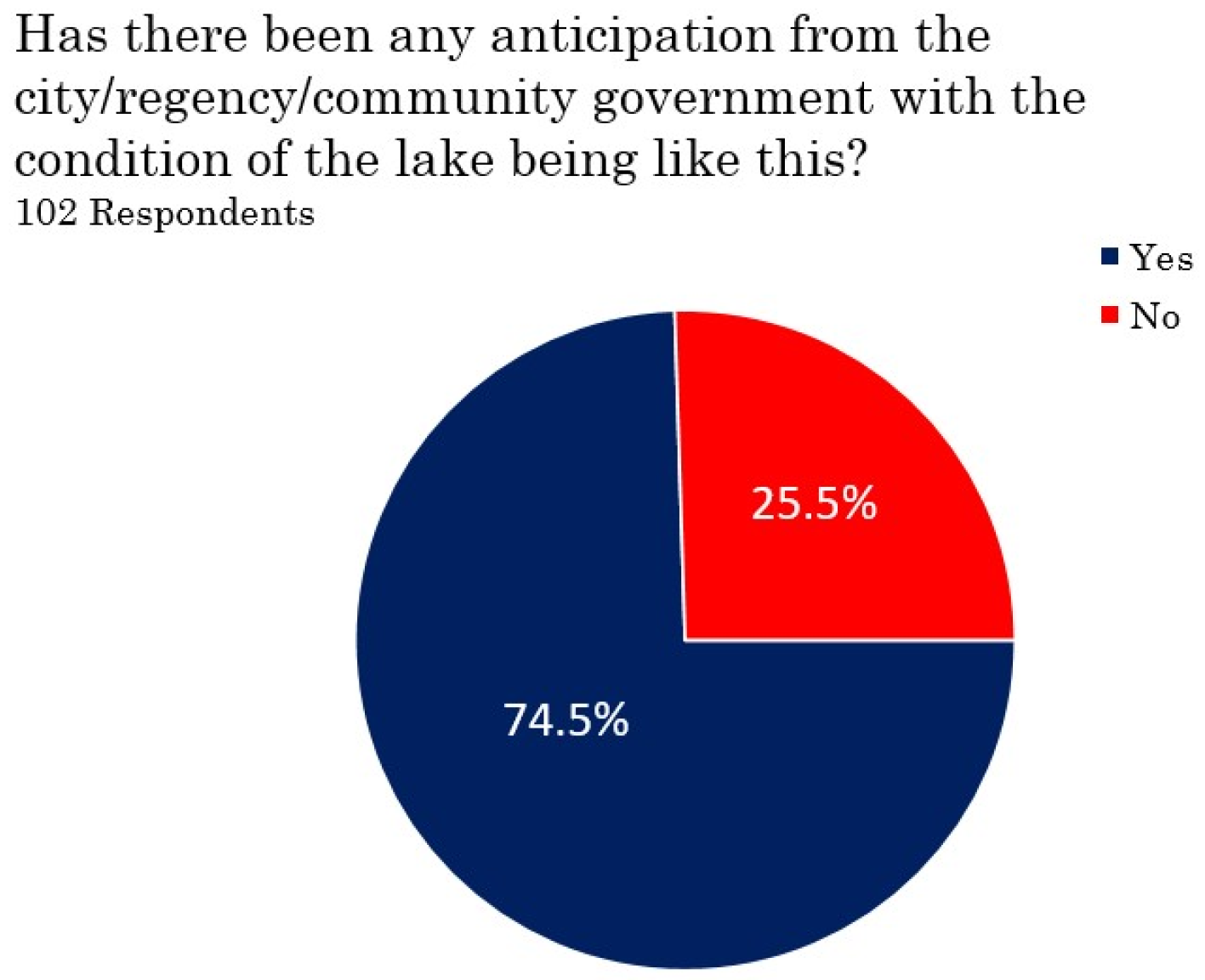

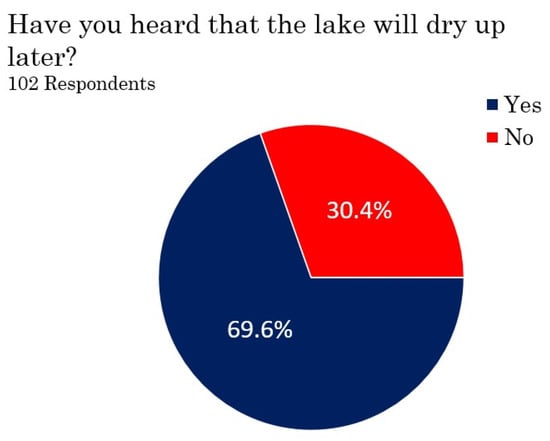

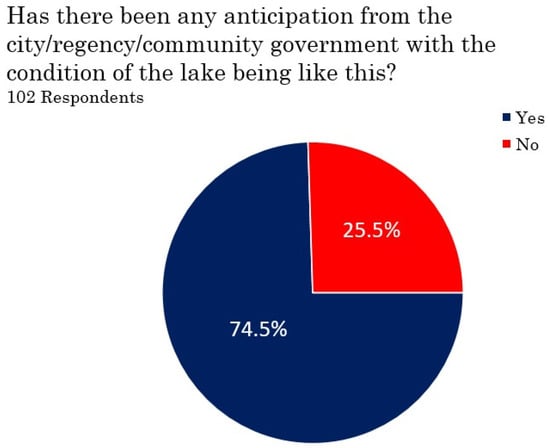

The survey of village officials and the village people allowed us to determine whether or not they have received information that Lake Limboto was predicted by scientists to disappear in a few years. From the results of interviews, more than half of the informants, as shown in Chart 3, at around 69.6%, answered that they had heard about the prediction of the loss of Lake Limboto due to shallowing and narrowing. With regard to how to anticipate and prepare for this event, as much as 74.5% answered that the government had prepared for this, as shown in Chart 4. In general, village officials and the community consider that the dredging of the lake is one of the government’s strategies for preventing a further loss of the lake. Besides dredging, the government also constructed a barrier dam between the lake and residential areas. Some people feel that this does not solve the problem because the water stagnates in residential areas for months during the rainy season. The construction of a barrier dam tries to solve the problem of the silting lake, but creates new problems for residents. Hence, despite the fact that 69.6% of the community knew about the predictions that the lake would dry up in less than ten years, any preventative measures were conducted solely by the government, while the community and the village officials have taken no action by themselves.

Chart 3.

Information about the lake.

Chart 4.

Government and community anticipation.

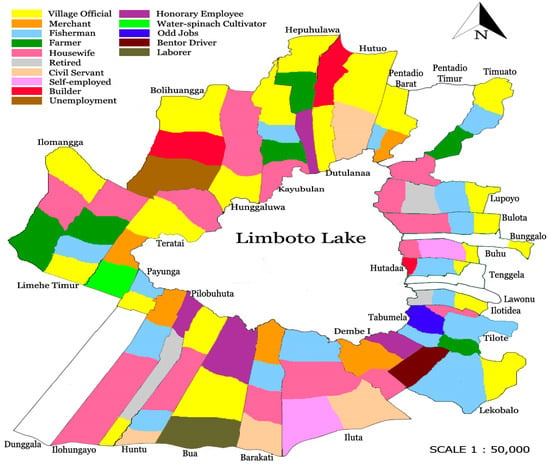

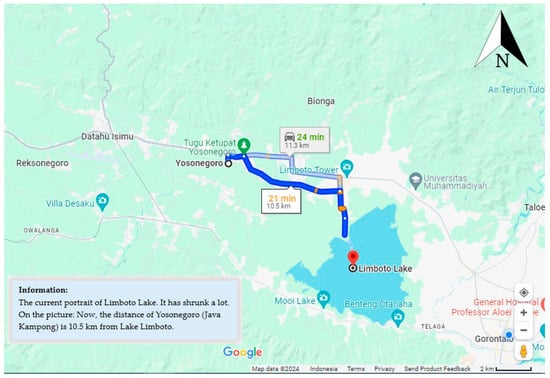

3.3. Research Locations

The interviews were mostly conducted around Limboto Lake in October 2022, in Gorontalo Province. Lake Limboto stretches more to the west into Gorontalo Regency, but also a little to the east, encroaching into the city area of Gorontalo. The research area includes sub-districts and villages located in the city and regency of Gorontalo that surround the lake, including 27 sub-districts and villages. These villages and sub-districts are (Figure 1) 1. Lekobalo sub-district, 2. Dembe 1 sub-district, 3. Iluta village, 4. Barakati village, 5. Bua village, 6. Huntu village, 7. Pilobuhuta village, 8. Ilohungayo village, 9. Payunga village, 10. Teratai village, 11. Limehe Timur village, 12. Ilomangga village, 13. Bolihuangga sub-district, 14. Hunggaluwa sub-district, 15. Kayubulan village, 16. Hepohulawa sub-district, 17. Dutulana’a sub-district, 18. Hutu’o village, 19. Pentadi’o Barat sub-district, 20. Timuato village, 21. Lupoyo village, 22. Bulota village, 23. Buhu village, 24. Hutada’a village, 25. Ilotidea village, 26. Tilote village, and 27. Tabumela village.

Figure 1.

Distribution of community work in Lake Limboto.

3.4. Adaptation of Occupations

Figure 1 offers us an understanding of how the people living around the lake were living while the lake was narrowing and shallowing. This figure shows the distribution of community work in the villages around Lake Limboto, but does not currently show the percentage of community employment because this research is qualitative in nature. This study does not intend to measure the percentage of what work is occupied by the people around the lake, only showing the results of interviews which show how the people who were generally lake fishermen in the past have changed their jobs due to the narrowing and silting of the lake.

The description of the distribution of community work in the villages around the lake in Figure 1 demonstrates that their work currently varies. In the southeastern region of the lake, there are generally still many fishermen. Lake Limboto fishermen include two types of fishermen: catcher fishermen and aquaculture fishermen. Aquaculture fishermen are predominantly located in Dembe, Iluta, and Barakati villages, while catcher fishermen are primarily located in the villages of Tabumela, Ilotidea, Tilote, Hutada’a, Buhu, and Lupoyo. The latter villages are riddled with poverty. The further the distance from the deep lake area, the more difficult it is to find fish. Ironically, however, these villages were predominantly occupied by fishermen. In the northern region, specifically in Ilomangga, East Limehe, Teratai, Bolihuangga, Hunggaluwa, and other areas, it is very rare for communities from those places to work as fishermen at present. Moreover, Ilomangga and Teratai are new villages, which established housing and plantations on new land upon the dried-up areas of the lake in the 1970s. Generally, people moved to this place because of the empty land that could be cultivated.

The nature of the inhabitants’ employment has become more varied as the lake has gradually become narrower. A few of the villagers work as village and government officials, then generally becoming civil servants. The villagers around the lake used to be fishermen, before switching professions to other jobs. This is one way of surviving the increasingly uncertain lake conditions. Despite this, in the Ilotide’a village, there are those who have continued to be fishermen to this day, though some of them go fishing in Gorontalo Bay, not in Lake Limboto, while still living around the lake. Likewise, some inhabitants subsidize their livelihoods via folk gold mining. However, based on the research of Maryati [20], folk gold mining in Gorontalo uses mercury, which is dangerous for the environment because it produces environmental pollution. Despite their workplace being located at a considerable distance from the lake, these people continue to commute from their residences close to the lake.

4. Culture Fluctuation, Surface Fluctuation

Culture around the lake is fluctuating in line with the narrowing and shallowing of the lake. From the interviews conducted, it appears that the people around the lake are changing their jobs based on the conditions of the season and the surface of the lake. If the lake is full of water, they go fishing. On the contrary, if the lake is drying, they engage in agriculture. Nevertheless, this alternation is difficult to maintain because, occasionally, the rainy season brings much precipitation and results in flooding, or the dry season makes the lake have insufficient water to irrigate the land for agriculture.

Several studies have shown that the shallowing of Lake Limboto is caused primarily by rainfall and sedimentation. However, a detailed discussion of rainfall and sedimentation itself showed that they are not an independent cause. According to the study conducted by Eraku et al. [10], the influence of precipitation on the variation of the lake inundation area has diminished significantly, only by 35%. There is an accumulation of other factors that have greater influence and contribute to large alternation in the inundation area of the lake, which has experienced many fluctuations. The result of the research demonstrated that the inundation area of the lake widens or shrink almost three times in less than a year.

Originally, the condition of the ebb and flow of the lake was described in a historical document from 1865 written by Von Rosenberg [19] (pp. 62–63).

De vergaderbak zijnde van een tal van riviertjes en beken, die uit het omringende gebergte naar het meer stroomen, is het uit dien hoofde aan een periodiek rijzen en dalen onderhevig, afhankelijk van de in het gebergte gevallen hoeveelheid regen. Aan den zuidoostkant ontlast het zich door twee smalle natuurlijke kanalen, welke zich nabij de kampong Potanga vereenigen en vervolgens voor dit dorp door de Tapa- of Bolangorivier verzwolgen worden.

In the quote above, Von Rosenberg explains that Lake Limboto is a confluence of a number of rivers from the surrounding mountains that empty into the lake. However, at certain times the surface fluctuates depending on the rainfall in the mountains around the lake. Then, the lake water flows out through two natural canals to the southeast, before merging near the village of Potanga. Furthermore, in this village, the channel meets the Tapa or Bolango River. This information about the number of rivers from the historical documents of the Dutch matches with the research of more recent studies undertaken by experts [4,5,8]. The fluctuations in the ebb and flow of the lake have also been discussed by Eraku et al. [10] in relation to the inundation area of the lake.

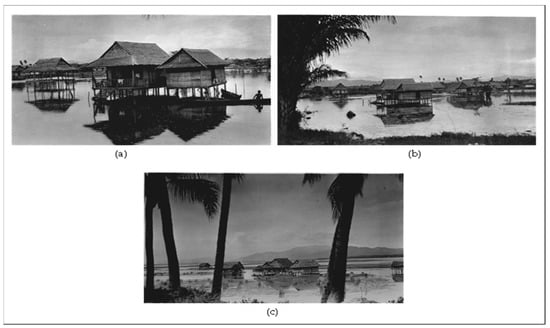

Documentations obtained from the Tropenmuseum [21,22,23], as shown in Figure 2, prove that people have always lived on the shores of Lake Limboto since past times, residing in stilt houses upon the shallow water.

Figure 2.

(a) Plank houses on Lake Limboto circa 1900–1930. (b) Plank houses on Lake Limboto around 1924. (c) Plank houses on Limboto Lake circa 1924.

In the above images from the year 1900 onwards, it is obvious that the people who dwelled near Lake Limboto built wooden plank houses in the shallower regions of the lake. In the past, people anticipated the ebb and flow of the lake water because, even long ago, the water level was always subject to fluctuations. However, the presence of elevated plank houses mitigated the impact of flooding since these structures were situated at a higher elevation than the lake level. Accordingly, the flooding did not lead to significant impacts. Moreover, in the past, the lake was much deeper, and the process of sedimentation was comparatively less significant than its current state.

From Von Rosenberg’s description [19] (pp. 56–58) about his trip around the lake, information about the settlements on the lake can be obtained. Von Rosenberg embarked on his voyage using a vessel known as a blotto (the name for a boat used by native people, originally called bulotu). This voyage took place along the Tapa (Bolango) River, leading to the Potanga region, before arriving at the lake. It indicates that during that period, the rivers in Gorontalo were used as a mode of transportation to access the Limboto region. He saw houses dispersed close to the riverbank, where the riverbanks were planted with various crops such as bananas, corn, coconuts, and other plant species. Upon the boat’s arrival at the lake, Rosenberg’s attention was drawn to the presence of the residences close to the lake. He anchored in Bolilla village (now known as Bulila). He stayed in a guest house situated at a distance of approximately a hundred meters from the lake. This description refers to the fact that, since the 19th century, the lake area has always been inhabited. In another part of Von Rosenberg’s writing, it is depicted that houses in Limboto, Gorontalo were generally stilt houses and built of planks and bamboo, with even Radja’s house being constructed from similar materials, though the difference being that it was a pavilion and there was a mosque. The images sourced from the Tropenmuseum also strengthen the customs of the local inhabitants residing near the lake, building their stilt plank houses.

Currently, people around the lake construct houses made of bricks or permanent houses on the site of the dried-up lake [14,15]. Consequently, during the rainy season and when the lake overflows, their residences are inundated by floodwaters reaching up to the level of the roofs. These circumstances were not taken into consideration by the community when they built permanent houses at the location of the dried lake. Accordingly, in the event of a water overflow, a disaster cannot be avoided because the community is situated in dried-up parts of the lake.

Based on the interview with the former village head of Ilotidea, it was made clear that people around the lake in the 1980s built stilt houses on the lake. The houses reached up to two meters from ground level, but when the lake began to dry, they built bricks houses on the surface of the lake area. As a result, if flooding occurred, the houses would sink, submerged by water up to the roof. The research of Kasamatsu et al. [4] and S. S. Putra et al. [5] state that floods are frequent and affect human life and the ecosystem. When floods occur, water remains around houses for months. Due to this, residents must vary their lives and occupations, especially fishers and farmers. It can therefore be said that the rapid decrease in lake area has a significant influence on the surrounding community’s lives.

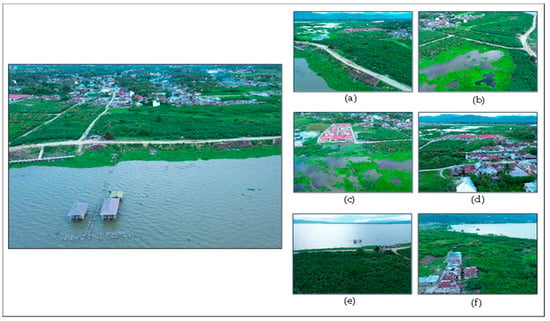

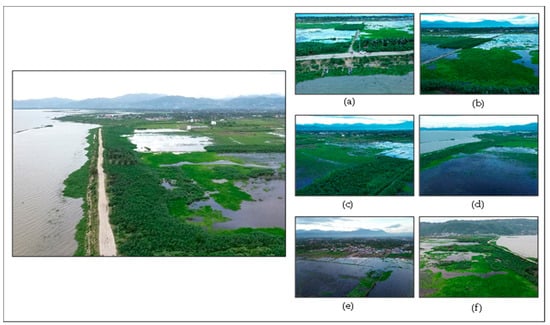

People in the past were well protected from the unstable water level in the lake because they lived in stilt or plank houses, so the fluctuations in the ebb and flow of the lake water did not have much impact on them. Currently, in the era of Lake Limboto’s shallowing and narrowing, there has been a notable trend towards the construction of permanent structures on the formerly submerged portions of the lake. As a representation of villages around the lake, we sampled two villages: Hutada’a and Ilotide’a villages (Figure 3 and Figure 4), which both suffer notable flooding in the rainy season, with the water remaining around their houses even after the rainy season has ended. These two villages are located on the southeast side of the lake.

Figure 3.

Hutada’a village on the shore of Lake Limboto blocked by a built barrier dam to the lake: (a) the village and stagnant water, (b) stagnant water, (c) housing surrounded by water, (d) Hutada’a village, and (e,f) the lake as seen from Hutada’a village.

Figure 4.

Ilotide’a village blocked by a built barrier dam to the lake: (a) Ilotide’a village seen from the lake. At the edge of barrier, fishermen park their boats; (b) stagnant water close to the village houses; (c) stagnant water forms swamps; (d) no exit for the water; (e) water at the edge of the village; (f) at the southern natural water channel for the lake not for the swamp.

Based on the field observation, the anticipation of changing water levels by the community around the lake was commonplace in the past, shaped by past habits of living in the lake area. However, considering the current circumstances of the lake, preparations now need to be improved because the lake basin has flattened, while the local people have built permanent and low-standing buildings. These new conditions have led to unexpected problems in the present day.

5. Changing of Lake Size and Changing of Settlements Model

The current dimensions of the lake have experienced a reduction of over two-thirds compared to its dimensions in the year 1863 based on the writing of Von Rosenberg. According to the data from 1991, the lake has narrowed by about 4000 hectares, from an original extent of 7000 hectares to 3644.5 hectares, and is still declining as of 2017, with the lake area barely reaching 2639 hectares. This shrinking process is further supported by the findings that the shrinkage of Lake Limboto is driven by sedimentation causes and the withdrawal of land from the northern side of Sulawesi [24].

The findings of Kasamatsu et al. [4] demonstrate that a significant amount of sediment flows into the lake every year, resulting in a reduction in water depth and a narrowing of the lake’s surface area. The quantity of sediment is estimated at 1.5 million m3 per year, and it is estimated that the lake will disappear in a time frame of 10–20 years. Segmentation is a significant and substantial challenge. The cause of the erosion can be attributed to agricultural activities in the mountainous area. Since several rivers flow to the lake, they bring much sediment to the lake, with the Alo-Pohu River from the west area of the lake being the primary one, bringing 63.8% of sediment with it. The shrinkage of the lake has seen exponential growth. It was 7000 ha in 1932, 4000 ha in 1960, and 1900–3000 ha in 1999. In line with Kasamatsu et al., the results of a study by Alfianto et al. [11] stated that the Alo River has the greatest potential for channeling sedimentation from upstream and towards Lake Limboto. This research also shows that the Biyonga Baluta River has the greatest potential to carry sediment resulting from land erosion.

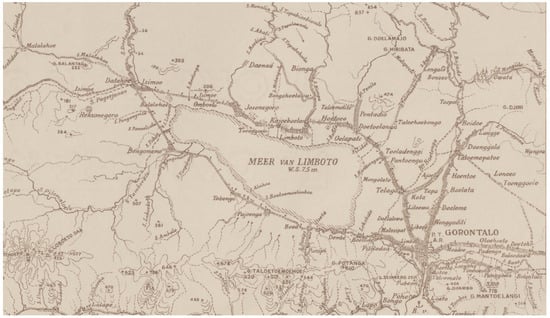

This information is important because the lifestyles of people around the lake change alongside transformations in the size of the lake. According to mapping work dating from the period of 1941 [25], as seen in the Dutch colonial map in Figure 5, it is evident that the size of Lake Limboto was much wider in the past.

Figure 5.

The size of Lake Limboto in 1941.

The provided map visually illustrates the presence of Lake Limboto’s northern section traversing the Josonegoro (also known as Javanese Kampong) region. The travel report by Von Rosenberg [19] (p. 62) provides a description of the lake’s dimensions and depth. He illustrated that Lake Limboto, better known by the natives as “Bulalo Mopatu” (Warm Lake), protruded slightly to the west. The lake was elliptical in shape without a deep curve. The length of the lake was approximately 18 km and had a width of 7.5 km. Von Rosenberg did not provide the exact depth of the lake, only offering an estimate of around 2½ fathoms plus a few feet. This was the size in 1863 when Von Rosenberg visited Gorontalo; his book was published in 1865 [19].

Figure 6 demonstrates how Lake Limboto has drastically shrunk by more than two-thirds of its original size in less than a hundred years when compared with the map in Figure 5. Consequentially, the lake areas that have dried up have turned into settlements. Based on the findings derived from field interviews, it was discovered that in the 1970s, the area of the lake that had dried up was used as a settlement by the local community. Notably, there were people from Suwawa, the eastern part of Gorontalo, that moved to the former lake area. A specific instance of this migration can be found in Ilomangga village, situated to the northwest of the lake.

Figure 6.

The current size of Limboto Lake, which has decreased by more than two-thirds.

The area, now including Teratai, Ilomangga, and East Limehe villages (see Figure 1), was once part of the lake. When the area dried up, people built settlements and established fields here. However, according to the community, these areas still had water in the form of swamps in the 1970s, but the area was already very shallow. When patches of land became completely dry, people came to occupy it. After all, at that time, there was no prohibition on establishing settlements in the former body of the lake, so many people moved to occupy the lake area that had dried up.

Based on the observed changes in the dimensions of Lake Limboto, it is evident that in less than a hundred years, the lake has transformed drastically in terms of size and depth. This transformation provided various opportunities for people residing on the new land. In spite of this, should high levels of precipitation come to fill the lake plains, this may pose significant risk of flooding disasters for the settlements around the lake because the surface of the lake, which has flattened, is no longer in the form of a basin.

6. Power of Place, Power of Belonging: Survival and Resilience

Considering the concept outlined by Baldwin et al. [2] (pp. 140–145) about the power of place, places are sites which are granted meaning. Here, “place” in terms of power, resistance, and representation does much to explain how cultural worlds are constructed and contested. In this sense, “places” are an arena of cultural struggle. In relation to Lake Limboto, we found out how this place is given meaning and what powers are struggling to occupy it. The way in which culture struggles for space can be seen in the societal life taking place around Lake Limboto, where the culture of people fluctuates in tandem with the condition of the lake.

People living around the lake are generally poor (see Figure 7). Moreover, the current water quality of the lake is also unsatisfactory, so it cannot provide sufficient productivity with regard to fishing. Even when researchers came to request permission to interview them, residents thought they were being interviewed for the acquisition of basic provisions. With the election season approaching, many think that some political parties will offer some basic provisions in order to secure their votes. The reality of poverty forces them to do whatever they can and expect help from others.

Figure 7.

Impoverished conditions of one village at the rear of the permanent house is built of brick. (a) Deteriorated plank house, (b) permanent houses, and (c) low-plank house.

Surprisingly, people still live next to the lake in spite of the impoverished conditions. This implies the existence of the aforementioned power of place, as people attribute meaning to the place, leading to a sense of belonging. The term “place” has more complexity than the word “location” implies, according to Yi-Fu Tuan in Baldwin et al. [2]. It is a distinct thing, a special ensemble that has a history and meaning. Place incarnates the experience and aspiration of people. It is a reality to be clarified and understood from the perspectives of the people who have given it meaning [2].

It is known from Von Rosenberg’s old travel report from 1865 [19] that there were people living along the shores of Lake Limboto since more than 150 years ago. Photos and maps from the early twentieth century show that there were houses on stilts built on the shores of the lake. This shows that the lake area is considered to belong to the community because they have been there for hundreds of years. They live in the lake area because, historically, there has been a tradition of fishermen residing there for generations. This sense of belonging has been inherited alongside the tradition of fishing, and has been passed down from generation to generation. This is the main reason why they do not have an inclination to move to another place despite the condition of the lake and the poverty which accompanies it.

The second reason is that the lake is productive and fertile, so the lake shapes their lives: the evolution of the lake goes hand in hand with the evolution of the inhabitants’ lives. The inhabitants try to adapt to the condition of the lake following the changes of the season. By following the lake’s fluctuating conditions based on the weather, local residents take advantage of it to survive. However, with the lake’s narrowing, its function as a water reservoir began to diminish. As a result, it became less productive and fertile. In response to this, it can be seen that local residents are trying to reposition themselves in the face of the situation they are encountering. In the rainy season, they become fishermen, while in the dry season, they engage in farming. The survival and resilience of the people are therefore maintained by reconfigurations of labor. The ability to adapt to the environmental challenges by reconfiguring labor can be interpreted as the resilience of the lake people. So far, this method has been successful in overcoming their life difficulties [26]. These two reasons above show how the people around the lake granted meaning to Lake Limboto as a place, given that they have been there for hundreds of years, and in that place, they based their lives.

Places have two types, namely public symbols and fields of care, according to Yi-Fu Tuan in Baldwin et al. [2]. Firstly, public symbols are places that can organize space into a center of meaning. These places are consciously created, and their meanings are consciously manipulated. Secondly, fields of care are places that gain meaning through repetition and familiarity in an emotionally charged relationship between people and a particular site. Baldwin et al. [2] provided as examples sacred places as public symbols, and homes as fields of care.

Amidst this framework, we can infer how people around Lake Limboto were tied with this place. It is a field of care for them since it has acted as a home for them for centuries. At the same time, the lake is also a public symbol that was created centuries ago. The lake has been valued as a blessed site, if we connect the two oral stories about the lake, namely the legend of Mbui Bungale and Du Panggola [27,28]. Lake Limboto is part of significant narratives that are regarded as mythical and legendary tales by the local people. In the “Legend of Lake Limboto”, the main character in this oral story was a female called Mbui Bungale, who stated that the presence of this lake was regarded as a blessing for the local community. She also outlined the moral principles that the residents of the lake must uphold. She emphasized that only good people with honesty and integrity can reside in the area. This comes from the belief that the region is sacred [7,27]. This statement clarified the expected behavior of people residing around Lake Limboto, among others. This also shows how important the role of Lake Limboto is for the sustainability of the social and cultural life of the community. This lake is an integral part of the lives of not only the people around the lake, but also the people of Gorontalo.

Another oral story that resides inside the collective minds of the lake-dwelling community is the “Legend of Du Panggola.” This legend is about an old man who looked after the lake. He provided advice on how to protect the lake and maintain kinship with it [7,28]. This legend exemplifies the significance of Lake Limboto for the inhabitants of Gorontalo. Oral stories serve as a means of transmitting historical messages from prior generations within a certain region. Through these narratives, we are able to gain insight into the local wisdom and intelligence of a particular society [7,29].

Though rarely do the current people of the lake remember and know about these legends, the legacy of the ancestors residing around the lake still lingers in the generational memory of its inhabitants. This legacy involves the preservation of the lake and the tradition of being a fisherman. Some interviewees stated that they had known since they were born that they were fishermen. Although they seek to preserve the lake and the tradition of fishermen, many do not realize the future fate of the lake.

It should be noted that in accordance with the way of thinking of the inhabitants, they feel tied to the lake area as both a public symbol and a field of care. In spite of the lake’s diminishing size, they still firmly believe that they can maintain their survival in this place. They do not move in order to sustain their livelihoods, despite the spaciousness of the Gorontalo area. Instead, they simply change jobs following the fluctuation of the lake’s conditions; some even remain as fishermen, either lake fishermen or sea fishermen, but they still belong to the lake area.

However, the two types of places defined above, public symbols and fields of care, are described in a universal manner, which does not consider cultural context. It is also important to see how different people provides meaning to a place. Although the meaning of public symbols and fields of care are important to take into consideration, places must be examined contextually and not separate from the culture of the relevant site. This understanding of place cannot be separated from social, economic, political, and cultural relations, which implies the existence of power relations [2]. The context of social, economic, political, and cultural relations is bound together to make meaning to the place.

In the case of Lake Limboto, there are at least three interest groups which must be considered when interpreting this place: the initial group of people who have lived in the lake environment for hundreds of years, the new communities living on new lands that have emerged since the 1970s, and the government. These three groups have their own sense of place at Lake Limboto, each offering different meanings for this place. The overall meaning attributed to the lake was constructed through the social interactions among these three groups in the context of the lake environment.

For the initial community groups who felt they belonged to the lake, the government did not offer any solutions to their problems. The initial group of people no longer sees the lake as a place to live prosperous lives, but rather as a home and a sacred place (a field of care and a public symbol) because they have survived in that place even though they are no longer lake fishermen. Historically, they have lived in that place for centuries, so the lake is home for them: both the happiness and pain experienced offers more meaning than a land certificate. Likewise, the new community groups that began to occupy the dry lake initially did so in order to survive due to economic problems, establishing agricultural land on the former lake land. They view the new land as home because they have been living in the area for more than fifty years, though the lake area may not yet have become a public symbol for them.

There is an intense interaction between the government and the two groups of society around the lake because the government is involved in a situation of fluctuating natural and socio-cultural conditions. The government always views the community as having to be regulated politically in the interests of preserving the lake, without considering the community’s sense of place. In the case of the construction of a barrier dam, this actually creates new problems, and the issue of land rights shows how the government interprets the lake from their perspective.

7. Government versus People of Lake Limboto: Power of Rules

Although there was no outright resistance from the lake community towards government intervention in the deteriorating condition of the lake, the community became confused about the government’s plans because they were not directly involved. However, they always assume that the government has good intentions for revitalizing the lake through building dams and dredging, which is arguably true.

The government here refers to the central government, not the regency or municipal government, nor even the provincial government. In relation to preserving lakes, because Lake Limboto is considered one of the most critically endangered lakes in Indonesia, the central government has been implementing grand projects to save the lake since 2012 [30]. The lake community has been aware of this scheme for a very long time. This was expressed by an artist and lake fisherman in a Lohidu (a type of traditional poem). This poem was sung during the year of planning in 2012. This poem criticizes the government for its lack of clarity in planning regarding the lake, and was recorded and noted by Tuloli [31,32]. The verses in the poem are as follows:

Bulalo (The Lake)

….

(Stanza 12)

Naqo-naqo to dalalo (A walk on the road)

Patuju motali putito (Want to buy eggs)

Didu mali pohalalo (No more places to hook)

Bulalo ma yilotipoto (The lake is already full of bushy grass)

(Stanza 13)

Patuju mo tali putito (Want to buy eggs)

Putito u ma yilahe (Boiled eggs)

Bulalo ma yilotipoto (The lake is already full of bushy grass)

U dudulaqa hi tuluhe (The leaders only sleep)

(Stanza 14)

Donggo u masahurulio (How famous)

Delo tola to patali (Like fish in the market)

Habari koroqolio (Reportedly it will be dredged)

Debo di:po yilowali (But apparently it hasn’t happened yet)

….

(Stanza 16)

Rencana di: la opulito (Plans never end) (57)

Patuju momongu lipu (Want to develop the country) (58)

Bulalo di:du otaluhulio (The lake no longer has water) (59)

Tuangio ma lolopu (The contents have perished) (60)

Even though the lake was finally dredged for revitalization and a barrier was built between residents’ houses and the lake, to this day, people still do not know what the master plan actually was. The revitalization of the lake taking place for more than ten years, but the people around the lake are only spectators to it, bystanders to the implementation of rules.

As an example, when the researchers asked one of the village heads (a woman) in Ilomangga village whether she had heard that the lake was predicted to dry up, she did not know because there was no information provided by the regency government. This village head has a father who was also the village head there. However, there is no information regarding the lake, except that people are not allowed to cross the lake boundaries, since there is a lake dredging. In fact, there have been predictions that the lake will disappear for some time now, as far back as Putra et al.’s article in 2013 [5].

As Tania Murray Li [33] (pp. 2–12) stated in her book, the will to improve shown by the Indonesia government from time to time is primarily centered on the use of the word “development”, which raises new problems in and of itself. The all-encompassing word “development” is used throughout the country, but none of the development schemes directed at improvement have reached any form of completion. Up until the present day, these improvement plans have continued to be implemented. Although not all improvement plans are bad, the meaning is in accordance with the wishes of the community, such as good roads and bridge repairs, flood control, waste management, and corruption eradication. However, in tandem with such development, new problems arise. Often, the reality of the development does not align with the original plan. In addition, the government frequently shows a disregard for regional customs and cultural identity. Residents are rarely consulted about how to improve their village or region, which has led to conflicts over the territories that simultaneously protected their culture. As such, power has shaped both their living conditions and surroundings.

Tania Murray Li conducted her research in the Central Sulawesi area several decades ago, but her statement remains valid even in the present day, as each time there is planning undertaken by the Indonesian government for an area, the people at that place do not know anything about it. This is especially the case in the revitalization of Lake Limboto. When the lake was dredged and the barrier was built between public housing and Limboto Lake, the community had no idea what would happen. They simply assumed that everything would be fine, as the government’s intentions were good. The government is revitalizing the lake so that sedimentation, which causes the lake to become shallow, is reduced, and that much is true. However, when there is heavy rainfall, additional small lakes are created between the barrier and Lake Limboto. These small lakes submerge houses because the water has no way to escape. The small lakes and swamps exist at the edge of the housing villages. In the dry season, the swamps evaporate and the lake water boundary becomes very far from the villages, even from the lake barrier. According to villagers, it can reach up to two kilometers away from the village edge. The platform in Hutada’a village (see Figure 3) during the dry season will be dry, and the lake water will be very far from that place. In Figure 3, the platform is submerged by water and fishing boats are lined up on the edge of the barrier dam.

With the construction of a barrier between the village and the lake, new problems arose, in conjunction with the already-existing issues caused by fluctuations in lake conditions. They must now survive on livelihoods other than fishing, while also having to deal with the government’s grand plans for lake revitalization, all the while knowing nothing about the plans themselves. In addition, they must also face the inability to overcome the swamps surrounding their villages. Thus, the instability of their lives is not only caused by the fluctuation of Lake Limboto’s condition, but also the intransparent planning of the central government.

In brief description, the reciprocal relationship between humans and Lake Limboto form a cultural landscape, as shown below (Chart 5):

Chart 5.

Reciprocal relationship between humans and nature.

8. Conclusions

Based on the findings and discussion above, we discovered that transformations in the activity around the lake follow directly in tandem with the fluctuating circumstances of the lake itself. The varying occupations of the people, which were formerly made up of lake fisherman but had to diversify in order to survive, demonstrate how the relationships and activities of the communities around the lake fluctuate and change along with the changes in the lake’s shape and circumstances over time.

The critical condition of the lake and the threat of it disappearing entirely are not enough of an impetus to make people leave the lake location. In fact, the socio-cultural meaning of the lake for its residents remains fully intact. They make great efforts to survive and have the resilience to stay in the lake area in spite of generally poor living conditions. A sense of belonging which has formed throughout history, familiarity, and repeated interaction with the place, forms a connection between the community and the lake because the lake is their home. The feeling of being at home and the existence of a culture of building permanent houses relates directly to notions of prosperity, as the modification of residences into permanent buildings has ties to perceived social class. There is also a desire for permanent residence, regardless of the threat which potential flooding poses.

By looking at the fluctuating activity patterns of the lake community, we can see that the community has actually responded to the deteriorating situation of the lake; however, they do not imagine that the lake will truly disappear for good because their lives have been marked by a historical cycle of dry and rainy seasons, all the while not noticing that the size of the lake was becoming smaller. Residents should have been made aware of the potential disappearance of the lake, as this would directly result in the loss of “their homes”, alongside the loss of their culture and social interactions.

Nevertheless, the intervention of the central government towards the revitalization of the lake must not ignore the historical existence of the society of those living around the lake. The government should not only monitor and improve the natural condition of the lake, but also pay attention to the humanitarian aspects of this crisis: how the community interprets the lake in historical, social, economic, political, and cultural contexts. The disappearance of the lake will be both an environmental disaster, as well as a socio-cultural one.

As such, the central government should offer more involvement to the lake-dwelling society and greater transparency with regard to its planning. It must also address the newly arisen problems caused by the development of a barrier between the lake and the villages: the swamps. The residents of Lake Limboto, having already endured decades of poverty, should be provided with hope and assurance for their social and cultural wellbeing via the improvement of the environment in which they live.

Author Contributions

M.B.: research design, data collection, and data analysis; M.J.: project administration and investigation of old and current lake size and dimension in the field with the supervision of M.S.; M.S. and H.K.: conceptual advice and critical comments; M.S.: funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was financially supported by the Research Institute for Humanity and Nature (RIHN: a constituent member of NIHU), project no. 14200102.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors of this article would like to acknowledge the support of this research collaboration with the Universitas Negeri Gorontalo (UNG).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Clair, R.N.S.; Williams, A.C. The framework of cultural space. J. Intercult. Community 2018, 17, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin, E.; Longhurst, B.; McCracken, S.; Ogburn, M.; Smith, G. Introducing Cultural Studies; Pearson Education Limited: Edinburg, TX, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M. Relocating Location: Cultural Geography, the Specificity of Place and the City Habitus. In Cultural Methodologies; McGuigan, J., Ed.; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, CA, USA; New Delhi, India, 1997; p. 215. [Google Scholar]

- Kasamatsu, H.; Jahja, M.; Arifin, Y.I.; Baga, M.; Shimagami, M.; Sakakibara, M. Prior Study for the Biology and Economic Condition as Rapidly Environmental Change of Limboto Lake in Gorontalo, Indonesia. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 536, 012005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putra, S.S.; Hassan, C.; Suryatmojo, H. Reservoir Saboworks Solutions in Limboto Lake Sedimentations, Northern Sulawesi, Indonesia. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2013, 17, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nontji, A. Natural Lakes of the Archipelago; Pusat Penelitian Limnologi, LIPI: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2016. (In Indonesian) [Google Scholar]

- Baga, M.; Usu, N.R. Tracing collective memory and social change in the communities around Limboto Lake, Gorontalo. Int. J. Soc. Sci. 2023, 6, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, S.L.; Achmad, N. Analisis Dinamik Model Pendangkalan Danau Pengerukan Endapan Dynamical Analysis of Mathematical Model of Limboto Lake Silting with Water Hyacinth Cleaning Solution. BAREKENG J. Ilmu Mat. Terap. 2020, 14, 597–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, S.L.; Achmad, N.; Panigoro, H.S. Revitalisasi Danau Limboto dengan Pengerukan Endapan di Danau: Pemodelan, Analisis, dan Simulasinya. Jambura J. Biomath. 2020, 1, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eraku, S.; Akase, N.; Koem, S. Analyzing Limboto lake inundation area using landsat 8 OLI imagery and rainfall data. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1317, 012111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfianto, A.; Cecilia, S.; Ridwan, B.W. Pemodelan Potensi Erosi Dan Sedimentasi Hulu Danau Limboto Dengan Watem/Sedem. J. Tek. Hidraul. 2020, 11, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, S.Y.; Ngabito, M. Tingkat Pencemaran Perairan Danau Limboto Gorontalo. Gorontalo Fish. J. 2018, 1, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasim, H. Perspektif Ekologi Politik Kebijakan Pengelolaan Danau Limboto. Publik J. Ilmu Adm. 2018, 7, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junus, N.; Mamu, K.Z. Arrangement and Regulation of Lake Area Policy. J. Yuridis 2019, 6, 136–156. [Google Scholar]

- Sarson, M.T.Z. The Legal Status of Certified Land Ownership of People Inhabiting around Limboto Lake. Indones. J. Advocacy Leg. Serv. 2020, 2, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, C. Cultural Studies: Theory and Practice; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Giles, T.; Middleton, J. Sudying Culture: A Practical Introduction; Blackwell Publisher: Oxford, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Oswell, D. Culture and Society; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Von Rosenberg, C. Reistogten in de Afdeling Gorontalo Gedaan op Last der Nederlandsch Indische Regering; Frederik Muller: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1865. [Google Scholar]

- Maryati, S.; Lihawa, F.; Yusuf, D.; Pratama, M.I.L.; Kasim, M.; Akase, N.; Hubaib, N.M. Improving community environmental literacy regarding the impact of mercury use in the artisanal small-scale gold mining sector (A study in Sumalata Timur District, North Gorontalo Regency, Gorontalo Province). J. Pengelolaan Sumberd. Alam Lingkung. 2022, 12, 633–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collectie Tropenmuseum. Paalwoningen in Het Meer van Limboto TMnr 60014256; Collectie Tropenmuseum: Gorontalo, Indonesia, 1924. [Google Scholar]

- Collectie Troppenmuseum. Paalwoningen in Het Meer van Limboto TMnr 60014257; Collectie Troppenmuseum: Gorontalo, Indonesia, 1900. [Google Scholar]

- Collectie Tropenmuseum. Paalwoningen in Het Meer van Limboto TMnr 60014261; Collectie Tropenmuseum: Gorontalo, Indonesia, 1924. [Google Scholar]

- Umar, I.; Marsoyo, A.; Setiawan, B. Analisis Perubahan Penggunaan Lahan Sekitar Danau Limboto Di Kabupaten Gorontalo. J. Tata Kota Drh. 2019, 10, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Batavia, T.D. Gorontalo; Universitaire Bibliotheken Leiden: Leiden, The Netherlands, 1941. [Google Scholar]

- Mathé, A.A. Understanding resilience. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oputu, A. The Legend of Lake Limboto. UPT.TIK UNG. 2012. Available online: https://mahasiswa.ung.ac.id/821412081/home/2012/9/7/asal_mula_danau_limboto.html (accessed on 28 October 2023).

- Tuloli, N. Heroic Stories of Gorontalo; Lamahu: Jakarta, Indonesia, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Vansina, J.M. Oral Tradition as History; University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Prasetyadi, K.O. Limboto Lake Shackled by Sedimentation; P.T Kompas Media Nusantara: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2019. (In Indonesian) [Google Scholar]

- Tuloli, N. Study of the Gorontalo Pantun Structure (System Formula); Gorontalo, Indonesia, 2013. (In Indonesian) [Google Scholar]

- Tuloli, N. Collection and Translation of Various Pantun Gorontalo Lohidu, Paantungi, Paqia lo Hungo lo Poli; Gorontalo Provincial Language Office: Gorontalo, Indonesia, 2013. (In Indonesian) [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.M. The Will to Improve, 1st ed.; Marjin Kiri: Tangerang Selatan, Indonesia, 2012. (In Indonesian) [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).