Abstract

Research into ecotourism behavior in China through meaningful gamification offers a promising strategy for enhancing sustainable tourism practices. With the rapid growth of China’s ecotourism sector, understanding and influencing visitor behaviors is crucial. This study focuses on meaningful gamification elements—exposition, information, engagement, and reflection—as a technique to nurture positive intentions towards ecotourism behavior, increase environmental awareness, educate tourists, and promote sustainable practices in an interactive way. Aligning with China’s technological and sustainability goals, this research introduces the Meaningful Gamification Elements for Ecotourism Behavior (mGEECO) model. This model is analyzed using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM)–Partial Least Squares (PLS) to test hypotheses related to the relationship between gamification elements and ecotourism intentions, grounded in Stimulus–Organism–Response (SOR) theory. The findings show that meaningful gamification significantly enhances positive intentions towards ecotourism by improving Environmental Attitude, Awareness of Consequences, and Ascription of Responsibilities. In conclusion, this approach raises awareness of sustainability practices and fosters a sense of responsibility, potentially leading to a more balanced and responsible ecotourism industry in China, benefiting both the environment and local communities while enhancing visitor experiences.

1. Introduction

In the field of ecotourism, environmentally responsible behavior is a significant element of sustainability, which stresses the significance of the conservation and enhancement of the environment while, at the same time, furnishing an educational experience for tourists. This involves methods for alleviating detrimental consequences on the environment, promoting natural and cultural resource conservation, and supporting local communities’ welfare and well-being. Current studies have dealt with examining the motivations behind environmentally responsible behavior, the key role that place attachment plays in promoting environmentally positive behavior, and the effects of ecotourism experiences on the attitudes and behavioral intentions of tourists [1,2,3,4]. Sustainable tourism can occur in both rural and urban settings. The distinctions between rural and urban tourism have become essential for understanding the dynamics of sustainable tourism, especially in relation to ecotourism [5]. Rural tourism, often characterized by its focus on natural landscapes and cultural immersion in rural areas, contrasts with urban tourism, which revolves around city attractions and modern amenities. However, rural tourism includes all types of tourist activities, including those that are harmful to the environment [6]. Therefore, the concept of ecotourism was formulated. Ecotourism, as an alternative form of tourism, involves visiting natural areas to learn, study, or carry out activities that are environmentally friendly, that is, a tourism based on experiences in nature, which enables the economic and social development of local communities. It focuses primarily on experiencing and learning about nature, its landscape, flora, fauna, and their habitats, as well as cultural artifacts from the locality [7]. Ecotourism, particularly in China, capitalizes on the country’s vast rural areas, integrating environmental conservation with cultural experiences [8]. With the rise in overtourism [9] to China’s urban centers and the increasing interest in nature, ecotourism in rural regions offers a sustainable alternative, drawing attention to the balance between environmental stewardship and rural development.

Chinese ecotourism has unique characteristics that set it apart from other regions, necessitating special academic attention. It has grown in popularity, with over one billion visits to ecotourism sites recorded in 2016 [8,10], and this trend has continued since the pandemic. Recently, Chinese tourists have preferred remote and less crowded ecotourism destinations, particularly in the western regions of China [11,12]. Chinese ecotourism differs from Western interpretations, in that it emphasizes the belief that it benefits human health and uses artistic elements to enhance natural beauty [13]. Ref. [11] indicated in their study that the Chinese government’s initiatives, particularly the ‘National Ecotourism Development Plan (2016–2025)’, have increased its appeal by aligning with China’s broader sustainability goals with a focus towards ecotourism whereby the government aims to improve China’s reputation for sustainable tourism [14].

Based on the related literature, ecotourism can culminate in heightened environmental awareness and environmentally responsible tourist behavior, which holds true with the promotion of tourists’ engagement and participation in educational programs and activities for the conservation and sustainability of the environment. In addition, sustainable ecotourism is a concept that has been extended to encompass a triple balance among three efforts, namely environmental conservation, cultural preservation, and economically profitable growth, which is the main objective behind ecotourism [1]. Moreover, in ecotourism, environmentally responsible behavior has multiple aspects, involving various activities and practices that are aimed towards ensuring that tourism activities’ sustainability is established. Research also calls for the importance of education, the collaboration of stakeholders, and the employment of a holistic strategy in ecotourism to develop a balanced consideration of the environment, culture, and economy [15]. Throughout recent years, there has been a notable increase in the call for action to address the severe problems faced by the environment, particularly from the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). However, owing to the increasing environmental issues that are attributable to human behaviors, the topic that has been dominating the environmental sustainability literature is environmentally responsible behavior, also known as pro-environmental behavior or ecotourism behavior [16]. This behavior is composed of behaviors that individuals practice, taking measured actions to promote positive environmental changes and minimize the impact of human negligence. However, similar to other regions in the world, the challenges in China persist, particularly due to unsustainable tourist behaviors such as littering and overcrowding, which jeopardize the ecological balance [11]. The key to ensuring the long-term sustainability of these sites is to educate tourists and promote conservation-friendly behavior, thereby mitigating human-caused damage. These factors present a need to improve and educate on tourist behavior during visits to ecotourism destinations. For this reason, this study has an essential objective which is to examine meaningful gamification elements’ role in influencing tourists’ intentions towards ecotourism behavior. This was explored through the Meaningful Gamification Elements for Ecotourism Behavior (mGEECO) model.

2. Literature Review

Generally, tourism represents one of the major and fastest-growing industries throughout the world, given that it is a crucial means for alleviating poverty via upstream and downstream effects. This is particularly notable with the influx of foreign currencies from tourists injected into emerging markets and low- and middle-income nations [17]. Nevertheless, at present, tourism industries contribute to negative environmental, economic, social, and cultural effects through the activities, accommodation, and transportation they entail [18,19,20], as manifested by pollution, losses in biodiversity, and natural habitat degradation [21]. Hence, countries all over the world are focusing on the sustainable development of tourism, with increasing recognition of ecotourism for the promotion of local lives and culture and the conservation of the environment [20,22,23]. Socially, tourism can lead to the alienation of community, degradation of culture, and dependence on low- and middle-income economies [21], and culturally, it can perpetuate losses or falsifications of customs and traditions, particularly through the promotion of mass tourism that leaves no consideration for the heritage and values of local communities [24].

In this line of argument, these challenges can be addressed through sustainable tourism practices, particularly through the use of clean energy, green technological innovation [25], and through the promotion and provision of heritage education for promoting sustainable development [24]. According to [25], the role of the tourism industry in the development of an ecological economy has been acknowledged with positive contributions to technological progress and tourism’s crowding out effect. In addition to this, Generation Z tourists have shifted towards sustainable behavior, with inclinations towards environmentally friendly travel options and experiences that are not harmful to local cultures and societies [26]. Such a shift in the behavior of tourists is important for the tourism industry to adapt and minimize its adverse effects while, at the same time, contributing positively to the environment and society.

Armed with this intention, ecotourism has been introduced as a type of responsible travel that stresses protecting the environment, the well-being of locals, and the education of tourists and tourism industries. Ecotourism is a concept that has been extended to cover three major areas, namely the environment, society, and economy, with an emphasis on the collaboration and mutual dependence of the conservation of the environment, preservation of culture, and growth of the economy in relation to sustainable development [1]. Thus, essentially, ecotourism refers to traveling to relatively undeveloped natural destinations to appreciate and enjoy the natural environment and various wildlife species therein and learn about the culture and history of the local community, with the aim of contributing to conserving the environment [7,27].

In recent studies, stress has been placed on environmental education and awareness in ecotourism, which suggests that ecotourism experiences lead to enhanced environmental knowledge, meaning that environmental attitudes and environmental consciousness can be transformed and developed for behavioral transformation [28]. More importantly, the ecotourism development of sustainability is considered to benefit locals’ lives as well as the environment through an enhanced business environment, service quality, and ecotourism advantages [1].

Specifically, ecotourism has been referred to by several studies [7,16,27,29,30], as the behaviors of tourists can benefit destinations in light of their economy, socio-culture, and environment and generate relevant learning experiences. Such experiences contribute to tourists’ awareness of their ecological surroundings and engagement in environmentally friendly behaviors [20,31]. Other related studies like [32] recommend promoting the ecotourism behavior of tourists to mitigate the negative effects stemming from a lack of awareness. Ecotourism behavior has been conceptualized as a concept with multiple dimensions [16], consisting of environmentally beneficial behavior (pro-environmental behavior, environmentally friendly behavior, ecotourism-guided behavior, and site-specific ecological behavior), socio-culturally beneficial behavior, economically beneficial behavior, and learning behavior.

Consequently, the ecotourism behaviors of tourists are important to sustain ecotourism development, and for this reason, this study considers ecotourism behavior to refer to environmentally responsible behaviors, which include environmentally beneficial behaviors (pro-environmental behavior, environmentally friendly behavior, and ecotourism-guided behavior) and socio-cultural beneficial behavior within China’s ecotourism sector.

2.1. Environmentally Beneficial Behavior

This research covers environmentally beneficial behavior, which refers to an individual’s environmental behaviors that can provide benefits to tourism destinations’ development and sustainability [33,34]. In relation to this, ecotourism experiences can motivate tourists’ learning concerning the natural environment, which, in turn, can boost their engagement in environmentally beneficial behaviors like respecting the local environment and lessening their impact on the destination [16,30]. Nevertheless, tourists generally have extensive impacts that can be ecological, socio-cultural, and economic [30].

2.2. Socio-Culturally Beneficial Behavior

Another construct covered in this study is socio-culturally beneficial behavior and its role in achieving sustainable development and reducing the negative environmental effects of tourists through the promotion of suitable ecotourism behavior. However, ecotourism behavior engagement among tourists generally takes a dip during tourist excursions across all types of tourism [20,35], with additional consumptions compared to those of daily lives. Past studies have also revealed several tourist behaviors such as disrespecting local cultures and environments, which negatively impact local places’ sustainability [16,20]. This shows the need for educating and guiding tourists to prevent harm and achieve a greater purpose; thus, new ways need to be developed to promote positive intentions towards ecotourism behavior, particularly in children and young adults, as they are next in line to protect the environment. Despite the visibility of ecotourism in the media, the concept is still a relatively new one that is rarely practiced in China. For the enhancement and promotion of the future development of ecotourism sustainability, ecotourism behavior knowledge needs to be inculcated in practitioners, residents, and tourists to achieve practical ecotourism behavior.

2.3. Meaningful Gamification

Gamification involves the careful selection, application, implementation, and integration of game elements to enhance user experiences, making them more engaging and enjoyable, similar to traditional gameplay. In 2016, Ref. [36] expanded the definition to include behavior changes, viewing gamification as the process by which designers embed game mechanics into daily activities to encourage and motivate changes in behavior. In the field of sustainable development, gamification has become a possible means for bridging the knowledge–action gap. This approach combines game-like elements, dynamics, and strategies into many non-game environments by extending the idea of using games to support sustainability [37].

The effectiveness of gamification in encouraging the adoption of environmentally responsible behaviors has been questioned by several studies [38]. However, studies have also indicated that it may be useful in promoting changes toward more environmentally conscious behaviors [37,39,40,41,42]. This suggests that gamification could be a useful tool to enhance the outcomes of environmental interpretation. Another strategy for nurturing behavior is fostering intrinsic motivation. In contrast to short-term behaviors motivated by external incentives and extrinsic rewards [43], long-term behaviors entail a deeper psychological journey that results in psychological changes or intrinsic motivations. This is where meaningful gamification comes into play. Meaningful gamification involves applying game design elements to increase intrinsic motivation and meaning in non-game settings. In this study, meaningful gamification consists of exposition, information, engagement, and reflection.

2.3.1. Exposition

Exposition in game design and meaningful gamification involves the utilization of game design aspects to offer narrative components. The narrative is essential in facilitating users’ comprehension of the connections between the past, present, and future [43]. Additionally, it can assist in decision making when real-life scenarios resemble those encountered in a game.

2.3.2. Information

Furnishing information in gamification systems is significant, highlighting a humanistic approach rather than a behaviorist perspective. The argument posits that providing users with the rationale and methodology behind a system, rather than solely the information and quantitative metrics, further fosters expertise and comprehension. Users can obtain real-time information concerning their progress with the exposition layer that links to actual real-world scenarios.

2.3.3. Engagement

This aspect of meaningful gamification pertains to enhancing users’ exploration and acquisition of knowledge by the creation of an engaging gameplay experience. The gamification system consists of compelling stories, progressive unfolding, and meaningful rewards to keep users engaged and challenged.

2.3.4. Reflection

The notion of reflection in gamification systems is also important, highlighting its significance in establishing a connection between gaming experiences and real-world scenarios by assisting users in finding interests and past experiences that can deepen their engagement and awareness. Reflection is an effective technique for facilitating behavioral changes [43]. Reflection can enhance tourists’ knowledge of the environmental and societal consequences of their activities and experiences, both positive and negative, by prompting them to think critically [44].

Consequently, four hypotheses were proposed in this study to uncover how meaningful gamification elements achieve the ojective. The hypotheses are as follows:

H1.

Meaningful gamification elements are positively associated with environmental attitudes.

H2.

Meaningful gamification elements are positively associated with awareness of consequences.

H3.

Meaningful gamification elements are positively associated with ascription of responsibility.

H4.

Meaningful gamification elements are positively associated with intentions towards ecotourism behavior.

2.4. Stimulus–Organism–Response Model (SOR)

In this study, the SOR model is adopted for the mGEECO model development. The SOR theory has three major fundamental elements, namely stimuli (S), organism (O), and response (R), and it is based on individual stimuli conditions that stem from the external environment [45]. To begin with, organism is based on the internal state that results from the influence of stimuli from the external environment, while response refers to the final outcome, which can be considered as an approach or avoidance behavior. According to [46], the internal state is described as an in vitro stimulation–eventual response medium, as well as mediation, with the stimulus having the ability to trigger the cognitive and affective state of a person to urge their decision to adopt or refrain from enacting a behavior [47]. Regarding stimulating factors, these may be in the form of subject and psychosocial stimulations [48], but later studies found objective and psychosocial stimuli to be triggers of individual cognitive and emotional states, resulting in behavioral tendencies and psychological results [48].

The wide application of SOR theory in different fields like service, education, and tourism is notable, and so is its importance as an analytical framework for explaining the behavioral processes of individuals [49,50]. Studies dedicated to tourism, such as [51], contend that the SOR model is one of the top extensively adopted frameworks for predicting tourist behavior. The SOR model was adopted by [52] as a theoretical framework to determine the relationship between amusement tourist experiences, brand satisfaction, brand identity, and brand loyalty in the Chinese context. They assigned a significant mediating role to brand satisfaction. Several other scholars have also used SOR as a theoretical underpinning in their studies to examine individual behavior, among which is [53], who used it to determine the effect of tourist experiences and integrated marketing communications on ecotourism satisfaction and intentions among Indonesian tourists. The findings supported a positive relationship between ecotourism experience and ecotourism satisfaction, and the mediating role that ecotourism satisfaction played in the relationship between ecotourism experience and intentions of tourists. Along the same line of study, Ref. [54] revealed the partial significant effects of stimulus factors on the perception and satisfaction of tourists, while [46]’s examination of tourists’ behavioral intentions regarding heritage conservation using 563 participating tourists in Mount SanQingShan National Park concluded that behavioral intentions towards protecting world heritage sites, tourists’ value perceptions, and destinations were all positively affected by outstanding universal value, heritage conservation was positively affected by outstanding universal value, and tourist behavioral intentions were positively influenced by heritage conservation education and knowledge. In a study of the same caliber, Ref. [55] investigated the integrated social cognitive theory and Stimulus–Organism–Response model to predict tourists’ planned behavior on ecotourism trips in a Thai context. Based on the results, stimulus factors affected tourists’ eco-travel engagement and level of satisfaction. Ref. [55] included a comprehensive literature review involving a decade of studies, showing a lack of tourist behavioral studies within the topic of ecotourism, with very view studies adopting the SOR model to examine the factors influencing tourists’ attitudes and ecotourism behavior. Consequently, to guide this investigation and achieve our objective, the following hypotheses were developed to understand this further:

H5.

Environmental attitudes are positively associated with intentions towards ecotourism behavior.

H6.

Awareness of consequences is positively associated with intentions towards ecotourism behavior.

H7.

Ascription of responsibility is positively associated with intentions towards ecotourism behavior.

However, the prediction of meaningful gamification implementation has different outcomes, ranging from positive perspectives to less favorable ones, and, thus, the discussion surrounding the topic is meaningful but divergent. Clearly, gamification has attracted increasing interest and opinions, but there still a need for a clear conceptual understanding of it [56], and empirical studies examining its effects are still scarce [57]. Hence, it is important to determine if meaningful gamification lives up to the optimistic assumed results of its effectiveness with the adoption of SOR, embedded in the mGEECO model as a fundamental inclusion.

In the context of tourism, ecotourism stresses conserving the environment, preserving the local culture, and developing the economy through profitable growth. Gamification can be integrated into ecotourism to improve the engagement, learning, and behavioral changes of visitors regarding sustaining the environment. Based on relevant studies, ecotourism is driven by the appreciation of nature, health benefits, social interactions, and escape from routine [58,59]. Techniques applied in gamification in light of rewards, challenges, and educational quests can be created to be consistent with motivations in order to generate a meaningful and interactive experiences that boost responsibility for the environment [60]. In another study by [40,61], they conclude that gamification approaches have the potential to educate and encourage pro-environmental behavioral changes, with suitable extrinsic and intrinsic motivational elements, immediate and sustained factors, and game attributes that encourage real life behavior.

In addition to the above, the use of meaningful gamification in ecotourism can reinforce the achievement of a triple balance among environmental conservation, cultural preservation, and economic growth, which is required for the ecotourism development of sustainability [1]. This may be exemplified through gamified activities that can motivate tourists to take part in conservation efforts, gain knowledge regarding local cultures, and contribute to the local economy via sustainable activities and practices [15]. In this regard, gamification application in ecotourism can be used as a strategic tool to promote tourists’ engagement in sustainable practices, improve their knowledge concerning the environment, and bring about the sustainable development of tourism sites. More importantly, gamified experiences need to be designed to be in line with the motivations behind ecotourism so that they can enable the triple balance of sustainability for worthwhile outcomes [1,15,58,59,60].

Additionally, meaningful gamification use in the promotion of positive intentions towards environmentally responsible behavior in ecotourism has garnered little attention in China [8,62]. Having an extensive area with the potential for ecotourism, it is crucial for China to address the lack of environmental education that has led to ecotourism development lagging behind in the country. Many locals are ignorant of the harm caused to the environment [63]. This has been attributed to the low environmental awareness and environmental values among people. Ref. [64] stressed the importance of the long-term effects of gamification on engagement in ecotourism cases and called for more investigations.

Moreover, few empirical studies have tackled meaningful gamification, particularly its effect on users and considering targeting behavior changes. Meaningful gamification has been applied in a number of areas, such as the promotion of consuming greener energy, healthcare, tourism, and life habits. Hence, in this study, meaningful gamification’s role in influencing tourists’ intention towards ecotourism behavior is explored through the Meaningful Gamification Elements for Ecotourism Behavior (mGEECO) model.

Besides the hypotheses regarding direct effects and indirect effects, relationships between the variable were also developed, which are as follows:

H8.

The relationship between meaningful gamification elements and intentions towards ecotourism behavior is mediated by environmental attitudes.

H9.

The relationship between meaningful gamification elements and intentions towards ecotourism behavior is mediated by awareness of consequences.

H10.

The relationship between meaningful gamification elements and intentions towards ecotourism behavior is mediated by ascription of responsibility.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Design and Setting

A quasi-experimental design was used. The study was conducted among Chinese students from China at Malaysian universities, as many Chinese students are enrolled in Malaysian universities. This helped the researchers to implement the study and achieve its objectives.

3.2. Population and Sampling

The population of this study consists of Chinese students studying at Malaysian universities. An mGEECO prototype embedded with meaningful gamification elements was developed to support the results in this study. mGEECO, which uses the Firebase database platform, is apparently blocked from running in China due to firewall restrictions. In addition, it is not permissible to distribute the third-party application in China without obtaining a proper license. Hence, data were gathered from Chinese students enrolled in Malaysian educational institutions, and a purposive sample was selected from this population based on their desire to participate in the study prototype and their accessibility to the researchers. In this research, 284 respondents whose aged ranged from 18 to 36 years old were chosen by the researcher, guaranteeing that all statements’ statistical criteria were used to select the sample size.

3.3. Data Collection Technique

This study uses survey as the quantitative method to collect data. Ref. [65] stated that the survey method is suitable for gathering in-depth data regarding individual views and beliefs. Furthermore, a close look at the literature reveals that there is a need to use quantitative methods while studying ecotourism behavior for model measurement.

A survey questionnaire was implemented. Several measurements were identified within the literature and were adapted to assess the variables of this research. For the collection of data, five measurements were used. The instruments included a demographic questionnaire, gamification elements, environmental attitude, awareness of consequences, ascription of responsibilities, intentions towards ecotourism behavior, and socio-culturally beneficial behavior. Data were collected by using an online survey from WenJuanXing (问卷星) and Google Form platforms with Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5. The information letter describing the study and the consent form were written and published on the first page of the questionnaire. Both documents were also translated into Chinese.

3.4. Data Collection Procedure

A total of 284 participants were enrolled. The participants were assigned to the prototype design in a random manner and then split into the two following groups: the experimental group, which utilized the mGEECO application with meaningful gamification elements, and the control group, which utilized the same app, but without any meaningful gamification elements. A two-week interval was established between the pre-test and post-test to ensure accurate results of both evaluations. The research commenced with the provision of information, outlining the objectives and delineating the duties involved. Upon reaching a mutual agreement and expressing their willingness to participate, the individuals were requested to complete a consent form before participating in this research. It was made clear to the respondents that their identities would remain anonymous during the course of this research.

Subsequently, the participants in both the treatment and control groups were instructed to download and initiate engagement with the application. Upon finishing the exercises, the participants were required to respond to an online survey regarding their experience with the application. Their results were collected through online surveys conducted on the Wenjuanxing and Google Form platforms.

Execution of Experiment through Meaningful Gamification (mGEECO)

The application began with mGEECO running on an Android or iOS device where users were greeted with a landing page asking them to either Sign Up (for first-time users) or Login (for returning users). Upon first-time login, users were asked to go through the introduction page, where they could choose their language of preference (Chinese or English), choose a character, and answer several questions regarding their understanding of ecotourism. Users then arrived at the Home page, where it highlighted an ecosite with problems that the user needed to fix. To be able to fix it, the user first had to go on an Adventure, where they could freely explore the area of their choice. Each adventure presented came with issues caused by tourists that are happening in the real world. By completing each adventure, the users could understand the impact and the importance of practicing appropriate ecotourism behavior. To reward their accomplishment of finishing the adventure, users were rewarded with ecopoints and ecosupply, which could be used to fix the ecosite problem, as well as contribute to a real-world mission. By having enough ecopoints to contribute to this mission, the global warming index would also decrease, mimicking real-world conditions. The challenge that users faced in mGEECO is that they had to understand and apply the correct ecosupply that they earned after each adventure to fix the ecosite problem.

This gamification elements were added to make sure that the users not only learned about ecotourism in a theoretical sense, but also applied their knowledge in a practical, engaging, and impactful manner. This ensured that the users were not passive recipients of information, but active participants in solving real-world environmental problems. By gamifying the awareness process and tying virtual accomplishments to real-world outcomes, mGEECO aims to foster a deeper understanding and commitment to sustainable tourism practices among its users. The ultimate goal is to create a community of environmentally conscious individuals who can contribute positively to the global effort of protecting the environment during travel.

3.5. Data Analysis

The analyses of the data collected for the purpose of model measurement were performed through the Partial Least Square–Structural Equation Modeling (PLS–SEM) version v4.0.0.9. The rationale behind choosing PLS–SEM was to evaluate the data quality based on the model characteristics. Additionally, the model goodness of fit was measured.

Moreover, to analyze the research model constructs, the developed research model consists of several exogenous variables (meaningful gamification elements which are exposition, information, engagement, and reflection) and one endogenous variable (intentions towards ecotourism). Furthermore, the mediator variables consist of three variables, which are environmental attitudes, awareness of consequences, and ascription of responsibility. In PLS–SEM, Ref. [66] states that the PLS–SEM model evaluates mediation effects through analyzing the direct and indirect connections between the study variables. Ref. [67] states that the algorithm for PLS–SEM helps to estimate the path coefficients and other model parameters in a way that maximizes the explained variance of the dependent variables, as well as identifying the relationships in both the measurement and structural models.

Measurement Model—Confirmatory Factor Analysis CFA

All variables were analyzed by confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). CFA seeks to determine if the number of factors and the loading of the measured (indicators) variables conform to what is expected based on pre-established theory [68]. Therefore, validity tests were conducted to determine the extent to which the measurement tool of this research measured what it claimed to measure. CFA examined the validity and the reliability of the measurement model through several criteria, such as the convergent and discriminant validity of the composite reliability with the average variance extracted (AVE).

4. Results

4.1. Assessment of the Validity and Reliability of the Study Variables

4.1.1. Meaningful Gamification Elements (MG)

Confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to evaluate whether the four dimensions of meaningful gamification were sufficiently loaded on the scale. The result showed a good fit to the data. Cronbach’s alpha for the meaningful gamification elements yielded a suggestion value of 0.953. Next, in terms of convergent and discriminant validity, several items on the meaningful gamification elements scale provided evidence for the convergent and discriminant validity of the composite reliability with the average variance extracted (AVE), as shown in Table 1 below. In terms of convergent validity, all items exceeded the acceptable loading of >0.40 on their factor, as shown in Table 2. The composite reliability score for the meaningful gamification elements construct was 0.955. Furthermore, the correlation among meaningful gamification elements items indicated discrimination. The average variance extracted (AVE) value for the meaningful gamification elements construct was 0.87.

Table 1.

Confirmatory factor analysis factor loading results for meaningful gamification elements.

Table 2.

Confirmatory factor analysis factor loading results for meaningful gamification elements.

4.1.2. Environmental Attitudes (EA)

Confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to evaluate whether the 15 items were loaded on one factor. The result showed a good fit to the data. Cronbach’s alpha for the environmental attitudes yielded a suggestion value of 0.969. Next, in terms of convergent and discriminant validity, several items on the environmental attitudes scale provided evidence for the convergent and discriminant validity of the composite reliability with the average variance extracted (AVE). In terms of convergent validity, all items exceeded the acceptable loading of >0.40 on their factor, as shown in Table 3. The composite reliability score for the environmental attitudes construct was 0.969. Furthermore, the correlation among environmental attitudes items indicated discrimination. The average variance extracted (AVE) value for the environmental attitudes construct was 0.699.

Table 3.

Confirmatory factor analysis factor loading results for environmental attitudes.

4.1.3. Awareness of Consequences (AoC)

Confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to evaluate whether the five items were loaded on one factor. The result showed a good fit to the data. Cronbach’s alpha for the awareness of consequences yielded a suggested value of 0.896. Next, in terms of convergent and discriminant validity, several items on the awareness of consequences scale provided evidence for the convergent and discriminant validity of the composite reliability with the average variance extracted (AVE). In terms of convergent validity, all items exceeded the acceptable loading of >0.40 on their factor, as shown in Table 4. The composite reliability score for the awareness of consequences construct was 0.924. Furthermore, the correlation among awareness of consequences items indicated discrimination. The average variance extracted (AVE) value for the awareness of consequences construct was 0.711.

Table 4.

Confirmatory factor analysis factor loading results for awareness of consequences.

4.1.4. Ascription of Responsibility (AoR)

Confirmatory factor analysis was performed on the data set measuring the ascription of responsibility in this research to evaluate whether the four items were loaded on one factor, as developed by [69]. The result showed a good fit to the data. Cronbach’s alpha for the ascription of responsibility yielded a suggested value of 0.914. Next, in terms of convergent and discriminant validity, several items on the ascription of responsibility scale provided evidence for the convergent and discriminant validity of the composite reliability with the average variance extracted (AVE). In terms of convergent validity, all items exceeded the acceptable loading of >0.40 on their factor, as shown in Table 5. The composite reliability score for the ascription of responsibility construct was 0.940. Furthermore, the correlation among the ascription of responsibility items indicated discrimination. The average variance extracted (AVE) value for the ascription of responsibility construct was 0.796.

Table 5.

Confirmatory factor analysis factor loading results for ascription of responsibility.

4.1.5. Intentions towards Ecotourism (ITE)

Confirmatory factor analysis was performed on the data set measuring intentions towards ecotourism in this research to evaluate whether the 13 items were loaded on two factors, as developed by [27,45]. The result showed a good fit to the data. Cronbach’s alpha for the ascription of responsibility yielded a suggested value of 0.950. Next, in terms of convergent and discriminant validity, several items on the intentions towards ecotourism scale provided evidence for the convergent and discriminant validity of the composite reliability with the average variance extracted (AVE). In terms of convergent validity, all items exceeded the acceptable loading of >0.40 on their factor, as shown in Table 6. The composite reliability score for the intentions towards ecotourism construct was 0.956. Furthermore, the correlation among the intentions towards ecotourism items indicated discrimination. The average variance extracted (AVE) value for the ascription of responsibility construct was 0.952.

Table 6.

Confirmatory factor analysis factor loading results for intentions towards ecotourism.

4.2. Discriminants Validity

The discriminant validity was subjected to CFA to establish the construct validity. As shown in Table 7, all variables were found to have a standards relation above the cut-off of 0.50 and were statistically significant, with a p value of less than 0.90.

Table 7.

Construct validity for the study variables.

4.3. Coefficient of Determination (R2)

The coefficient of determination (R2) represents the percentage of variance in the dependent variable. The R2 helps in computing the squared correlation between the dependent variables actual and expected values. Ref. [70] recommended that R2 values of 0.75 correspond to a strong influence, 0.50 represents a moderate influence, and 0.25 corresponds to a weak influence. However, this study calculated the R2 using Smart PLS, and the results of the model are shown in Table 8.

Table 8.

Coefficient of determination, R2.

4.4. Analysis of the Structural Model

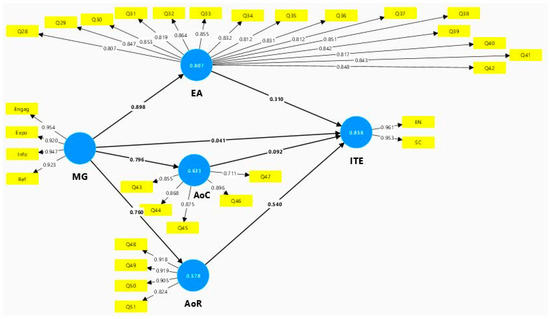

The structural model was examined to validate the conceptual model and test the research hypotheses [70]. Regarding the path coefficients analyses, as shown in Table 9, the coefficient values of the paths starting with meaningful gamification and ending in environmental attitudes had a positive impact with (Beta = 0.898, p < 0.05). The coefficient values of the paths starting with meaningful gamification and ending in awareness of consequences had a positive impact with (Beta = 0.796, p < 0.05). The coefficient values of the paths starting with meaningful gamification and ending in ascription of responsibility had a positive impact with (Beta = 0.760, p < 0.05). Nevertheless, the coefficient values of the paths starting with meaningful gamification and ending in intentions towards ecotourism had no significant impact with (Beta = 0.041, p > 0.05). The coefficient values of the paths starting with environmental attitudes and ending in intentions towards ecotourism had a positive impact with (Beta = 0.310, p < 0.05). The coefficient values of the paths starting with awareness of consequences and ending in intentions towards ecotourism had no significant impact with (Beta = 0.092, p > 0.05). The coefficient values of the paths starting with ascription of responsibility and ending in intentions towards ecotourism had a positive impact with (Beta = 0.540, p < 0.05) (Figure 1).

Table 9.

Structural model results.

Figure 1.

Direct effects of Meaningful Gamification for Ecotourism behavior (mGEECO) model.

Mediation Analysis

The last step in the PLS–SEM structural model was to test the hypothesized relationships by running a bootstrapping algorithm in Smart PLS version v4.0.0.9. Using the bootstrapping method in the assessment of path coefficients entails a lease bootstrap sample of 5000, and the number of cases should be equal to the number of observations in the original sample [70]. The PLS–SEM model evaluates mediation effects by analyzing the direct and indirect connections between variables. Mediation analysis centers on discerning if the impact of an independent variable on a dependent variable operates through a mediator variable. Using [71] as a guideline, the mediation effect occurs when the direct and indirect paths from the independent and mediator variables to the dependent variable are significant, indicating partial mediation. If the direct path from the independent variable is significant and the indirect path through the mediator is not, no mediation is evidenced. On the other hand, when the direct path from the independent variable to the dependent variable is not significant but the mediator path is significant, full mediation is evidenced. Lastly, when neither the direct nor indirect paths are significant, no mediation effect is observed.

In the first step, with regard to the direct effect of meaningful gamification elements (exposition, information, engagement, and reflection) on intentions towards ecotourism, environmental attitudes, awareness of consequences, and ascription of responsibility, as mentioned on Table 9, the results confirmed the postulated hypotheses that meaningful gamification elements significantly impact environmental attitudes (Beta = 0.898, p < 0.05), awareness of consequences (Beta = 0.796, p < 0.05), and ascription of responsibility (Beta = 0.760, p < 0.05). Thus, the hypotheses (H1, H2, and H3) were supported. Also mentioned in Table 9, the result did not support that meaningful gamification impacted intentions towards ecotourism (Beta = 0.041, p > 0.05), thus, hypothesis 4 was not supported.

In the second step, with regard to the direct effects of environmental attitudes, awareness of consequences, and ascription of responsibility on intentions towards ecotourism, as mentioned on Table 9, the result confirmed the postulated hypotheses that environmental attitudes significantly impact (Beta = 0.310, p < 0.05) ascription of responsibility (Beta = 0.540, p < 0.05). Thus, the hypotheses (H5 and H7) were supported. Also mentioned in Table 9, the result did not support that awareness of consequences impacted intentions towards ecotourism (Beta = 0.092, p > 0.05), thus, hypothesis 6 was not supported.

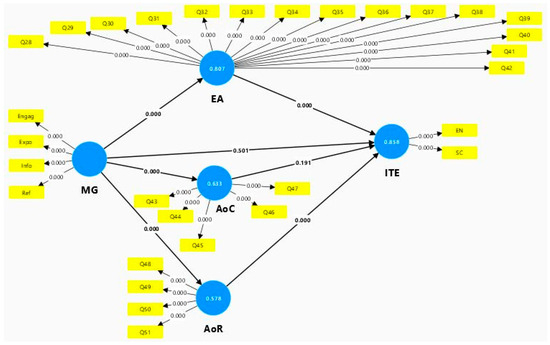

In the third step, with regard to the indirect effects of meaningful gamification elements on intentions towards ecotourism through environmental attitudes, the results in Table 10, as visualized in Figure 2, confirmed the postulated hypotheses that environmental attitudes significantly partially mediate the relationship between meaningful gamification elements and intentions towards ecotourism (Beta = 0.279, t = 4.859, p. 0.000 < 0.05), therefore, H8 was supported. In regard to the indirect effects of meaningful gamification elements on intentions towards ecotourism through awareness of consequences, the results in Table 10 did not confirm the postulated hypotheses that awareness of consequences does not significantly mediate the relationship between meaningful gamification elements and intentions towards ecotourism (Beta = 0.073, t = 1.303, p. 0.193 > 0.05), therefore, H9 was not supported. With regard to the indirect effects of meaningful gamification elements on intentions towards ecotourism through ascription of responsibilities, the results in Table 10 confirmed the postulated hypotheses that ascription of responsibilities significantly partially mediate the relationship between meaningful gamification elements and intentions towards ecotourism (Beta = 0.410, t = 6.808, p. 0.000 < 0.05), therefore, H10 was supported.

Table 10.

Mediation model results.

Figure 2.

Indirect effects (mediation) of Meaningful Gamification for Ecotourism behavior (mGEECO) model.

5. Discussion

5.1. Direct Effect

5.1.1. Meaningful Gamification (MG) to Environmental Attitudes (EA)

H1.

Meaningful gamification elements are positively associated with environmental attitudes.

Considering the robust relationship between Meaningful Gamification (MG) and Environmental Attitudes (EA) in the context of ecotourism, with a strong beta value of 0.890, this study suggests a significant correlation between the implementation of meaningful gamification techniques and shifts in environmental perspectives. Recent research supports this finding, with [72] demonstrating that interactive, challenge-based learning experiences lead to more positive attitudes towards environmental protection compared to traditional educational methods.

Equally important, it also highlights the potential of gamification to target specific components of environmental attitudes, as categorized by [73] as follows: cognitive, affective, and behavioral. However, the effectiveness of gamification may vary across demographic groups, as noted by [74]. While the strong correlation between MG and EA presents promising opportunities for ecotourism providers to enhance guest experiences and environmental appreciation, the document emphasizes the importance of the careful and deliberate implementation of gamification techniques to avoid shallow engagement or the trivialization of significant environmental issues.

5.1.2. Meaningful Gamification (MG) to Awareness of Consequences (AoC)

H2.

Meaningful gamification elements are positively associated with awareness of consequences.

The study proposes a model that utilizes four key elements of meaningful gamification—exposition, information, reflection, and interaction—to enhance the understanding of the environmental impacts of ecotourism. The analysis reveals a significant positive impact of MG on AoC, suggesting that gamified experiences can effectively increase tourists’ awareness of the environmental consequences of their actions. This finding is supported by recent research, such as [75]’s study, which demonstrated that interactive, game-like elements in eco-educational programs can significantly enhance participants’ environmental awareness.

These elements are described as “market-interfering devices” that influence consumer behavior and decision making in the ecotourism market. The model suggests that incorporating these factors can lead to a heightened understanding of the repercussions of behaviors among visitors in China’s ecotourism industry.

The study in [76] found that acquiring environmental knowledge can enhance individuals’ consciousness of environmental concerns, leading to an increase in pro-environmental conduct. The success of the meaningful gamification platform is attributed to its ability to provide tailored, real-time feedback and challenge-based activities that can enhance tourists’ understanding of their environmental impact.

Overall, the model aims to utilize gamification to enhance the effectiveness of and engagement with increasing awareness about the effects of ecotourism. The ultimate goal is to promote a more sustainable and responsible ecotourism sector by enhancing awareness and concern among all parties involved, as supported by [77]. This approach is presented as an effective method for increasing ecotourists’ awareness of the consequences of their actions, ultimately promoting responsible and sustainable behavior in ecotourism settings.

5.1.3. Meaningful Gamification (MG) to Ascription of Responsibilities (AoR)

H3.

Meaningful gamification elements are positively associated with ascription of responsibility.

In the context of ecotourism, particularly within China’s rapidly growing tourism industry, this study suggests that MG emerged as a powerful tool for fostering environmental accountability, surpassing basic point systems by creating engaging experiences that significantly impact tourists’ ascription of their responsibilities regarding the environmental consequences of their actions. There are four key components of meaningful gamification that contribute to enhancing the ascription of responsibility, as follows:

- Narrative experiences: These help users to develop a heightened sense of personal responsibility by emphasizing the consequences of individual actions on the environment.

- Information provision through points, levels, and feedback: This strengthens the connection between behavior and consequences by providing explicit and measurable data on the impact of user actions.

- Reflection on progress monitoring and mastery: This enhances users’ understanding of their contributions to environmental conservation by prompting them to reflect on their achievements and personal growth.

- Engagement through challenges, rewards, and social interaction: This fosters a sense of personal investment in environmental outcomes and allows users to share their commitment and achievements.

Additionally, another study by [78] found that internal motivation stimulated by game features like feedback and challenge is more effective in promoting lasting behavioral changes compared to external rewards. Another key point in [61] indicated that eco-gamification is most effective when locations demonstrate authentic dedication to the environment. The implementation of context-specific gamification in Chinese nature reserves was shown to enhance visitors’ perception of responsibility towards local conservation initiatives.

The study emphasizes that the effectiveness of meaningful gamification depends on carefully designing game elements to align with intended behaviors while avoiding the pitfalls of “ludictatorship”, where game elements become manipulative. When properly implemented, meaningful gamification can foster a collective sense of responsibility and empowerment in promoting eco-friendly actions.

Overall, this concludes that meaningful gamification shows significant potential in improving the allocation of responsibilities in ecotourism, particularly in China’s expanding tourism industry. By utilizing narratives, information systems, reflection tools, engagement mechanisms, and meaningful contexts, gamification can help visitors to internalize their responsibility for sustainable travel behaviors. This approach not only enhances the engagement and effectiveness of environmental education, but also has the potential to bring about significant transformation in people’s attitudes towards and involvement in ecotourism activities, ultimately contributing to the conservation of natural environments and the advancement of sustainable tourism practices.

5.1.4. Meaningful Gamification (MG) to Intentions towards Ecotourism Behavior (ITE)

H4.

Meaningful gamification elements are positively associated with intentions towards ecotourism behavior.

Revealing a surprising lack of a direct significant effect (β = 0.041, p > 0.05), this finding contradicts previous research, such as that conducted by [79], which established a clear correlation between gamified experiences and intentions to engage in ecotourism. This discrepancy highlights the need for further research in this domain, as noted by [80,81].

Furthermore, it can serve as a responsible and ethical interface connecting travelers, organizations, and communities [82,83]. However, the effectiveness of gamification in encouraging sustainable tourist behaviors is not guaranteed [84]. This study emphasizes that, while MG can enhance ascription, attitudes, and sense of responsibility, it does not necessarily translate into actual changes in behavioral intentions or intentions to engage in ecotourism. Factors such as individual beliefs, surrounding circumstances, and the specific structure and implementation of gamified experiences can all influence whether meaningful gamification results in tangible ecotourism objectives.

Another key point is that this result suggests that deeper psychological factors like intrinsic motivation, self-efficacy, and perceived behavioral control may need to be considered for gamification to have a direct effect on ecotourism intentions. It also notes that meaningful gamification has the potential to impede ecologically advantageous behaviors in some cases. The authors stress the importance of analyzing the intricacies of the relationship between the tourism industry and gamification. They caution against the assumption that gamification always results in positive effects, emphasizing the need for a thorough analysis of the complexities and limitations of this relationship.

5.1.5. Environmental Attitude (EA) to Intentions towards Ecotourism Behavior (ITE)

H5.

Environmental attitudes are positively associated with intentions towards ecotourism behavior.

The statistical finding suggests that, as people’s environmental sentiments improve, their inclination to participate in ecotourism activities rises. The magnitude of this link (β = 0.310) indicates a moderate to significant impact size, emphasizing the significance of environmental beliefs in influencing ecotourism ambitions.

Moreover, this discovery is supported by a recent study conducted by [85], which offers a thorough analysis of the connection between pro-environmental beliefs and sustainable tourism activities. The study discovered a strong correlation between positive environmental attitudes and a greater inclination to engage in sustainable tourism activities, such as ecotourism. This significantly enhances the significance of the observed correlation, as meta-analyses consolidate findings from various studies, yielding a more resilient and widely applicable conclusion.

Accordingly, Intentions towards Ecotourism Behavior consist of two primary elements, as follows: Environmentally beneficial behavior and Socio-culturally Beneficial Behavior. The issue of environmentally helpful behavior encompasses pro-environmental behavior, overall, environmentally friendly behavior, and behavior driven by ecotourism principles. The diverse nature of ecotourism objectives implies that having favorable environmental attitudes might impact many eco-friendly behaviors in tourism settings, encompassing both overall environmental awareness and specialized ecotourism practices.

The correlation between EAs (environmental attitudes) and ITEs (intentions to engage in ecotourism) is consistent with the established principles in the fields of environmental psychology and tourism studies. It implies that developing positive environmental attitudes through education, awareness campaigns, or personal experiences could be a successful approach to encourage ecotourism and sustainable travel habits. These findings have significant ramifications for the management of tourism, attempts to conserve the environment, and the development of policies in the sustainable tourism industry.

In short, the statistical data from the study, along with the subsequent meta-analytic findings, strongly support the idea that there is a direct and positive relationship between Environmental Attitudes and Intentions towards Ecotourism. This relationship highlights the significance of fostering favorable environmental attitudes as a method to stimulate engagement in ecotourism and advocate for more environmentally friendly travel behaviors.

5.1.6. Awareness of Consequences (AoC) to Intentions towards Ecotourism Behavior (ITE)

H6.

Awareness of consequences positively is associated with intentions towards ecotourism behavior.

The correlation between awareness of consequences and intentions towards ecotourism is not statistically significant (β = 0.092, p > 0.05). Therefore, possessing information alone regarding ecological consequences may not be enough to inspire travelers to participate in ecotourism. This discovery contradicts recent research, such as [86]’s study, which found a significant association between environmental knowledge and the desire to participate in sustainable tourism. This mismatch may indicate the presence of unaccounted intervening factors in the model, highlighting the need for additional inquiry.

This research integrated the extended personal norm activation of pro-environmental action with the consideration of future implications and societal value orientation. An individual’s conscience and the environmental impact of their acts are influenced by their personal norms [87]. This application implemented meaningful gamification features through various activities in the prototype. The duration of the relevant gamification experience was a two-week interval compared to the control group. Given these circumstances, time played a crucial part in diminishing the significance of intentions towards ecotourism due to the awareness of its consequences. Users did not develop and cultivate a gradual understanding of ecotourism in their lives, which led them to fully recognize the significance of intentional ecotourism behavior at ecosites.

This research highlights the complex and often contradictory connection between environmental ideals, the assignment of outcomes, and the motivations behind ecotourism behavior. Environmental concerns and values can directly influence pro-environmental behavior, although psychological factors like perceived self-efficacy and general environmental worries seem to play roles in mediating this connection. However, the research findings do not offer definitive proof to support the claim of a significant difference between attitudes and behavior. The correlation between the ascription of outcomes and the inclination to participate in eco-friendly actions may be less complex than previously believed. A thorough examination of the available information reveals that acknowledging the environmental impacts and importance can have a substantial and immediate impact on individuals’ intentions to support the environment and engage in eco-friendly actions.

The relationship between environmental values, ascription of consequences, and ecotourism behavioral intentions may be affected by factors like perceived barriers, social norms, and situational restrictions. Nonetheless, these factors do not necessarily erase the underlying connection. Further investigation is necessary to fully comprehend the complex interaction between psychological, social, and contextual elements. However, the existing evidence suggests a stronger and more direct association between these essential concepts than what is suggested in the research.

5.1.7. Ascription of Responsibilities (AoR) to Intentions towards Ecotourism Behavior (ITE)

H7.

Ascription of responsibility is positively associated with intentions towards ecotourism behavior.

The model shows a strong positive relationship between ascription of responsibility and intentions towards ecotourism behavior. It established a strong connection between ascription responsibilities and the will to engage in eco-friendly behavior under environmental consciousness. It shows that persons who possess a strong feeling of responsibility towards the environment are more inclined to establish intentions to actively participate in pro-environmental behaviors [88]. The motivation for individuals to take action to reduce their environmental impact stems from a strong sense of duty, also known as the “ascription of responsibilities”.

Moreover, the inclination to engage in eco-friendly actions, often known as “intention towards ecotourism behavior”, is a significant indicator of one’s real pro-environmental conduct [88]. To clarify, individuals with a robust inclination to participate in environmentally friendly actions, such as recycling, conserving energy, or decreasing waste, are more inclined to actively implement and demonstrate those behaviors. These findings indicate that it is essential to cultivate a strong feeling of environmental responsibility and enhance individuals’ intentions to engage in eco-friendly behavior in order to encourage environmentally conscious actions [89].

The connection between the ascription of responsibilities and intentions towards ecotourism behavior is reinforced by the idea of ecological philosophy, which highlights the interdependence of species and their environment. By cultivating a sense of accountability and purpose towards environmentally friendly behavior, individuals can cultivate a more profound comprehension of their position within the wider ecological system and undertake measures to save the environment.

This research indicates that there are various crucial characteristics that determine pro-environmental intentions, which are a form of environmentally beneficial behavior. Research has indicated that individuals with greater levels of innate intelligence, often known as “naturalistic intelligence”, and stronger intentions to engage in pro-environmental actions are more likely to exhibit responsible environmental behavior. These findings indicate that both cognitive ability and motivational factors contribute to the development of environmentally advantageous behaviors.

In order to create successful treatments that encourage the continued adoption and practice of environmentally beneficial behaviors, it is crucial to comprehend the intricacies of these behaviors and the diverse elements that impact them [90]. Presenting information regarding the environmental repercussions of engaging in or abstaining from a certain behavior can serve as a powerful approach to promoting pro-environmental intentions and actions.

Meanwhile, the ascription of responsibilities and its impact on intentions towards ecotourism behavior in the context of socio-culturally beneficial behavior is that the ascription of responsibilities is favorably associated with environmental concerns and pro-environmental acts. The ascription of responsibilities, as defined by [91], pertains to individuals’ convictions regarding their personal obligations to reduce environmental harm. Individuals who have a feeling of accountability towards the adverse effects of their own actions on the environment are more inclined to participate in environmentally friendly behaviors to mitigate such effects [92]. These findings indicate that promoting a feeling of individual accountability for environmental concerns can result in higher levels of pro-environmental intents and actions, ultimately contributing to socio-cultural sustainability.

The study also suggests that an individual’s environmental consciousness affects their attitude towards responsible activities [91]. When individuals acknowledge the detrimental effects of their lifestyle choices, they are more inclined to assume accountability for mitigating these effects through their own behavior. This emphasizes the significance of increasing knowledge and educating individuals on the environmental repercussions of their actions to encourage behaviors that are beneficial both socially and culturally.

Environmentally and socially beneficial behavior are intricately connected. Participating in pro-environmental behavior, such as minimizing waste and preserving resources, not only has favorable effects on the environment, but also yields beneficial socio-cultural outcomes. Studies indicate that engaging in prosocial behavior, such as making charitable donations and displaying altruistic actions, can lead to indirect advantages for the overall welfare of both the benefactor and the recipient. Moreover, older individuals with a greater cognitive ability are more likely to exhibit altruistic decision-making behaviors, indicating that societally beneficial behavior can be impacted by personal characteristics [93].

5.2. Indirect Effect (Mediation)

5.2.1. Meaningful Gamification (MG) Elements on Intentions towards Ecotourism Behavior through Environmental Attitudes (EA)

H8.

The relationship between meaningful gamification elements and intentions towards ecotourism behavior is mediated by environmental attitudes.

Meaningful gamification (MG) has emerged as a powerful tool in shaping environmental attitudes (EAs) and promoting sustainable behaviors in the context of ecotourism, particularly in China. Recent studies have demonstrated that integrating engaging gamification elements into ecotourism experiences can significantly enhance visitor engagement, foster learning, and encourage conservation-supporting behaviors [77,94]. This approach extends beyond individual tourists, benefiting local communities and the broader tourism industry through improved visitor satisfaction and economic gains [72]. The implementation of MG strategies, such as augmented reality apps in national parks and sustainability measures in eco-lodges, has shown promising results in data collection, allowing for personalized experiences and more efficient ecotourism management [63]. Importantly, environmental attitudes act as a crucial mediator between gamified experiences and eco-friendly behaviors, leading to longer-lasting behavioral changes that extend beyond the immediate tourism context. This multifaceted approach not only serves as a model for promoting environmental awareness and sustainable travel habits globally, but also demonstrates the potential to balance tourism expansion with environmental preservation, ultimately contributing to the long-term viability of ecological sites and local communities.

5.2.2. Meaningful Gamification (MG) Elements on Intentions towards Ecotourism Behavior through Awareness of Consequences (AoC)

H9.

The relationship between meaningful gamification elements and intentions towards ecotourism behavior is mediated by awareness of consequences.

It is important to realizethat the complex relationship between meaningful gamification (MG) elements and intentions to engage in ecotourism behavior is mediated by Awareness of Consequences (AoC). Contrary to initial expectations, this study reveals an adverse indirect impact, suggesting that gamification may not effectively bolster eco-friendly objectives by raising awareness of environmental effects in certain contexts. This phenomenon is attributed to several factors, including the oversimplification of complex environmental issues through gamification [95], the potential for eco-anxiety resulting from heightened awareness, misalignment with users’ intrinsic motivations [63], and cognitive overload from overly complex gamified platforms. This research highlights the need for a more nuanced approach to incorporating gamification into environmental education and ecotourism, emphasizing the importance of balancing engagement with education, integrating reflective practices, aligning gamification features with users’ inherent incentives, and combining gamification with other educational methods. These findings underscore the complexity of utilizing gamification for environmental education and behavior modification, calling for the careful design of gamification elements to effectively convey the intricacies of environmental issues while promoting sustainable behaviors and attitudes.

5.2.3. Meaningful Gamification (MG) Elements on Intentions towards Ecotourism Behavior through Ascription of Responsibilities (AoR)

H10.

The relationship between meaningful gamification elements and intentions towards ecotourism behavior is mediated by ascription of responsibility.

The relationship between meaningful gamification (MG) elements and intentions towards ecotourism behavior is mediated by the ascription of responsibilities [96]. Recent studies (2023–2024) have provided substantial evidence supporting the efficacy of gamification in promoting environmental awareness and sustainable actions. This study found that MG elements significantly impact participants’ sense of accountability towards environmental issues, while [97] noted that MG was most effective when directly linking users’ actions to environmental outcomes. In [74], cultural variables were highlighted as influencing MG’s effectiveness, with a more pronounced mediation effect in collectivist cultures. This research also explored the implications for environmental policy and education, suggesting the integration of MG elements into public awareness campaigns, educational curricula, corporate sustainability initiatives, and community engagement programs. These findings emphasize the potential of MG as a tool for environmental education and behavior changes, with AoR serving as a crucial psychological mechanism linking gamification features with ecotourism behavioral outcomes. However, this study notes that, while the direct effect of MG on ecotourism behavior is significant, its indirect effect through AoR as a mediator is negative, indicating the complex nature of this relationship and the need for further investigation.

6. Conclusions

Considering the effects of meaningful gamification (MG) elements on ecotourism behavior, this research indicates that MG positively influences individuals’ desire to engage in eco-friendly behavior, with game-like aspects such as exposition, information, engagement, and reflection effectively enhancing ecosite experiences. The study highlights the substantial influence of gamification on environmental attitudes, which acts as a mediator between gamification and intentions to engage in eco-friendly behaviors. The cognitive–emotional perspective of gamification emphasizes its ability to evoke both positive and negative emotions, impacting behavior.

All things considered, several recent studies support these findings. For instance, Ref. [98] found that incorporating relevant gamification features can enhance pro-environmental intentions and actions. Ref. [99] emphasized the importance of using a theoretical framework in developing and implementing gamification interventions. To support and prove studies from [1,4,6,45,47], meaningful experiences and motivations must be synchronized to obtain the virtue of balancing in sustainability, showing that this study echoes that these GE elements bring about a balance in sustainability. Through GE in mGEECO as part of the respondents’ experiences, it indicates a very positive result in instilling intentions towards ecotourism behavior.

As a matter of fact, recent studies have emphasized the capacity for favorable transformations in tourist conduct. The research conducted by [8,11] identified particular activities, such as disregarding local culture and causing harm to the environment, that have negative effects on sustainability. These findings provide a basis for implementing focused MG interventions. With the mGEECO app, this heightened awareness presents opportunities for the advancement of education and the formulation of policies that are designed to foster responsible tourism. Consequently, destinations can now employ more efficient tactics to safeguard their cultural legacy and natural resources while also reaping economic benefits from tourism.

Despite differing opinions on gamification, recent empirical research has consistently shown favorable results of implementing meaningful gamification. The expanding amount of research offers a distinct conceptual comprehension of gamification and its impacts, eliminating previous doubts. Multiple meticulously conducted studies have demonstrated that, when applied correctly, this is proven, such as the study in [44], in which its effects were still uncommon. Nevertheless, the findings of this study show that meaningful gamification greatly improves user engagement, motivation, and performance in diverse fields. The use of the Stimulus–Organism–Response (SOR) theory, integrated into the mGEECO model, demonstrated its effectiveness in the design and assessment of gamified systems. Theoretical underpinnings, along with increasing evidence, validate that meaningful gamification not only meets, but frequently extends beyond the positive expected outcomes of its efficacy. As such, the discussion surrounding gamification has evolved from speculative debate to a more unified recognition of its tangible benefits and the best practices for its implementation.

However, the study also noted a negative result regarding the awareness of consequences as a mediator between MG and intentions towards ecotourism behavior, suggesting the need for further investigation. The ascription of responsibilities was identified as a significant mediating factor between MG and behavioral intentions, indicating that storytelling elements can positively impact eco-friendly behavioral intentions. Furthermore, additional studies from 2022 to 2024 corroborate these outcomes, including research on consumer behavior [78], entrepreneurial education [100], and the importance of psychological mediators in understanding gamification effects [101]. Overall, the document underscores the potential of meaningful gamification in promoting eco-friendly behaviors while acknowledging the need for further research to fully understand its mechanisms and optimal strategies.

This finding has a notable positive effect and important implications for promoting intentions to engage in eco-friendly behavior, especially in the Chinese context. This subsequent analysis will examine the potential practical environmental advantages that could arise from these discoveries in the specific setting of China, based on current research conducted between 2018 and 2024. Besides China being the most densely populated nation on Earth and possessing one of the largest economies, it also faces substantial environmental obstacles. Favorable changes in environmental attitudes fostered by initiatives such as mGEECO could have a vital impact on tackling these issues. In a study conducted in 2018, Ref. [102] discovered a significant correlation between enhanced environmental views among Chinese people and a greater inclination to participate in eco-friendly activities. These findings indicate that the changes in attitudes caused by mGEECO could result in observable changes in behavior among China’s younger population.

The gamification components of mGEECO have a particularly strong impact in the Chinese environment. In a study conducted in 2024, Ref. [103] found that using gamification tactics specifically designed for the Chinese culture can greatly increase the levels of interest and involvement of Chinese people in environmental issues. The researchers discovered that integrating aspects of Chinese culture and values with environmental gamification resulted in an increased determination to embrace environmentally responsible actions [103]. Implementing mGEECO in China and aligning its content with Chinese cultural values could enhance its positive influence on environmental attitudes and behavioral intentions. This was also proven by the study from [104], which indicated that gamification affordances positively affect users’ value perceptions, which, in turn, promote environmental concerns.

Furthermore, the portability of mGEECO is well-suited to China’s extensive adoption of smartphones and the widespread use of mobile applications among young Chinese individuals. In 2018, a research from the China Internet Network Information Centre (CNNIC) emphasized that more than 98% of internet users in China utilize mobile devices to access the internet [105]. The extensive use of mobile devices provides an ideal opportunity for initiatives such as mGEECO to effectively reach a wide audience and potentially impact national environmental views. The potential influence of enhanced environmental views on intentions to engage in eco-friendly behavior in China is significant. In a thorough investigation conducted in 2018, Ref. [14] revealed a significant positive relationship between environmental knowledge and environmental attitudes, as well as between environmental knowledge and behavioral intentions. The researchers observed that interventions aimed at influencing environmental attitudes through environmental education could have a ripple impact on various elements of everyday living [14], thus contributing to broader sustainability initiatives in Chinese cities.