1. Introduction

In the last decade, electronic commerce (e-commerce) has seen significant growth, leading to changes in the way businesses operate and how customers make purchases [

1]. This transformation has resulted in time and cost benefits for both buyers and sellers [

2,

3,

4]. During the past five years, there has been a significant increase in online commercial activity, which has been further accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic [

5]. The rise in e-commerce is evident in countries such as Indonesia, which has the fourth largest population globally [

6]. This growth may be attributed to the increase in smartphone use and Internet access, leading to an in-proportion growth in e-commerce transactions. The adoption rate in Indonesia jumped to 32.1% in 2023 and the trend is likely to continue, with a forecast rate of 46.5% in 2028 [

7].

Customers often encounter difficulties in trying to choose from the variety of options available online [

8]. To remain competitive in the e-commerce market, companies strive to improve the quality of their services and the experience of their customers [

9]. This is achieved by offering high-quality products at rates that are competitive with others [

10,

11,

12]. To satisfy consumers’ desire for faster delivery services, platforms often offer multiple delivery or shipping options to choose from [

13]. Maintaining customer loyalty and satisfaction is the building block of a successful e-commerce business, to ensure a high repurchase rate [

14]. Growth in e-commerce has also led to a substantial increase in demand for delivery services, including last-mile delivery [

15,

16]. However, this increase in demand can result in delays and other issues that can negatively impact the entire customer experience. Additionally, buyers may have challenges in assessing the product’s quality and may also experience complications in the process of returning products and obtaining a refund. Such actions can harm the reputation of e-commerce firms and discourage customers from making repeat purchases [

1]. Online shopping allows customers to buy various items, and if the products do not meet their expectations, they can be conveniently returned to the store. Therefore, the impact of returns on e-commerce companies may have a substantial effect on their reputation and the satisfaction of their customers. Free return rules mitigate perceived risk while making online purchases, resulting in increased sales. However, they may also stimulate wasteful product returns, as online return behavior extends beyond just returning damaged products [

17]. Enforcing a strict return policy can lead to loss due to bad return experiences, while a permissive return policy is vulnerable to abuse of returns [

18].

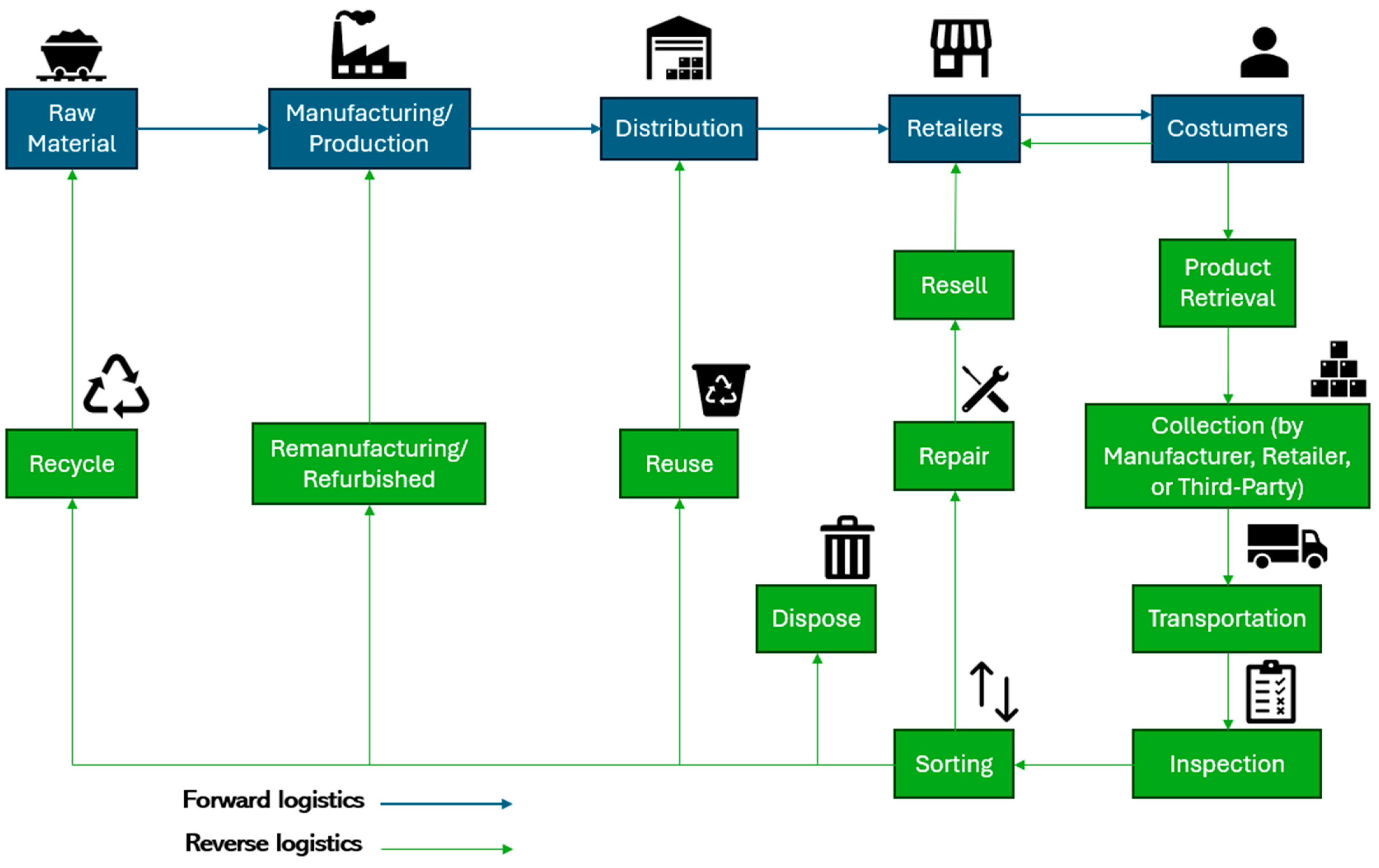

Effectively handling reverse logistics is essential for enterprises across all sectors, especially in e-commerce since consumer happiness and loyalty greatly depend on the company’s capacity to efficiently manage returns and improve the customer experience [

19]. Therefore, it is crucial for companies to effectively control the transportation of goods in both forward and reverse logistics throughout the whole supply chain [

10]. Rogers and Tibben-Lembke [

20] defined reverse logistics as the efficient transportation of finished items from their point of use back to their original site, with the purpose of either recovering their value or properly disposing of them, achieved through excellent planning. The primary goal of reverse logistics is to recover the value embodied in products, or to ensure appropriate disposal [

21]. Incorporating reverse logistics into an established supply chain is a complex procedure that requires substantial restructuring of the current supply chain framework [

21,

22,

23]. Furthermore, it includes a wide range of complicated techniques and methodologies [

19]. Improvements have focused on critical areas such as the integration and utilization of reverse logistics; the analysis and prediction of product returns; the outsourcing of tasks; the optimization of RL networks; and the creation of decision support systems to improve product recovery, transportation, and processing [

24]. Although there are many benefits and reasons for organizations to use RL, only a limited percentage of enterprises have efficient strategies to manage product return. Most organizations choose to ignore this feature, sticking to the conventional or progressive supply chain approach [

25].

Previous studies highlighted the importance of factors related to the characteristics and demography when analyzing e-commerce [

26,

27,

28,

29]. Previous research on e-commerce product returns focused predominantly on business-to-business (B2B) perspective markets and/or other geographic regions [

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36]. Despite the very large size of the market, research on e-commerce in the business-to-customer (B2C) market in Indonesia is underrepresented in the literature. Based on a literature search conducted in the Scopus and Web of Science databases, only a very few articles on product returns management and reverse logistics in Indonesia were identified. Lesmono et al. [

34] analyzed the effect of switching costs and product return management on repurchase intent with customer satisfaction and customer value playing as moderating variables in the B2B context in Indonesia. A study by Michel et al. [

37] presented the comparative analysis of the quality of e-services in Indonesia based on the type of product, which was divided into physical product and digital product. The work of Chayanon et al. [

38] included a statistical study on the nexus between green capability, product return, value chain costing, and the adoption of closed-loop supply chain in Indonesia. The study by Wilson et al. [

39] focused on factors affecting customers satisfaction in e-commerce in the Indonesian market. They highlighted the importance of factors such as the quality of the e-service, including its reliability, web design, time saved, and performance, but did not investigate in-depth issues related to product returns. These facts allow us to formulate a conclusion about the existence of a theoretical research gap. The research carried out by the authors of this article is innovative both in terms of the topic (customer perspective), spatial scope (Indonesia), and the methodological approach (AHP method—as any of the identified studies applied it in Indonesian context).

Therefore, the purpose of this paper is to fill the theoretical research gaps by defining the key factors that influence the returns of products in reverse logistics in the e-commerce market in Indonesia, specifically focusing on the customer experience (B2C). After scoping the study of the literature [

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39], two research questions are stated as follows:

RQ1: What are the key factors that influence a customer’s experience when returning products in e-commerce in Indonesia?

RQ2: What solutions are the most suitable to improve the customer’s experience and thus reduce the volume of product returns in reverse logistics in e-commerce in Indonesia?

This study proposes an approach that is based on the analytical hierarchy process (AHP). The analytic hierarchy process (AHP) is a reliable method for evaluating intangible elements, using a discrete scale [

40]. The AHP is often used to tackle complex decision-making situations that involve uncertain information [

17]. Previous studies on returns management in e-commerce have employed the AHP approach [

2,

10,

17,

41,

42,

43], but to the best of our knowledge, no research has particularly investigated and identified the factors that influence product returns in the e-commerce sector in Indonesia.

The reminder of the article is structured as follows:

Section 2 summarizes the literature review.

Section 3 discusses the materials and methods.

Section 4 presents the results of this study.

Section 5 includes a discussion of the results. In

Section 6, the final conclusions are stated, and further research is presented.

3. Materials and Methods

Prioritizing the criteria (

Table 3) and alternatives (

Table 4) can be accomplished through a variety of different approaches known as multiple criteria decision making (MCDM). There are different methodologies established for the purpose of tackling MCDM, such as the analytical hierarchy process (AHP) [

18], analytical network model (ANP) [

63], fuzzy-technique for order preference by similarity to ideal solution (TOPSIS) [

60], and grey-based decision making trial and evaluation laboratory (DEMATEL) [

58]. Hybrid combinations of MCDM can be utilized as well, such as AHP and criteria importance through intercriteria correlation (CRITIC) [

1], the fuzzy AHP and TOPSIS approach [

10], and fuzzy VIKOR and fuzzy TOPSIS [

32].

AHP was previously used in related research by Aggarwal and Aakash [

60], who applied it to discover the key factors for business-to-customer (B2C) e-commerce websites. They identified and ranked 23 key factors for supporting the effectiveness of B2C e-commerce systems. The findings indicated that the most important aspects for the success of an e-commerce website were timeliness, up-to-datedness, understandability, and preciseness in the content quality criteria. Lamba et al. [

40] used the AHP to prioritize obstacles in the reverse logistics of e-commerce. They conducted an analysis of 16 obstacles in five distinct categories. The findings revealed that the three main obstacles were insufficient investment in RL, inadequate understanding of optimal methodologies, and unpredictable market demand. Naseem et al. [

17] using the AHP to identify obstacles in the adoption of blockchain technology in RL. The mentioned research proofed the usefulness of AHP method in the identification of key factors based on expert survey. This method is an effective technique for assessing intangible attributes by employing a discrete scale. It is commonly employed to address intricate decision-making difficulties that involve uncertain information [

10,

41].

The main goal of the analytic hierarchy process (AHP) is to rank the different options by combining many levels of data into a unified score. The main feature of this is its dependence on matrices for pairwise comparisons. Hence, the utilization of the analytic hierarchy process (AHP) is applied to tackle the difficulties associated with decision making that involves several criteria in practical situations. The justifications for using AHP were the required small sample size, high level of consistency, simplicity, and availability of user-friendly software, as indicated by Darko et al. [

64]. The quantitative research requires in order to ensure representativeness requires purposeful sampling and experts (informants) who are articulate, reflective, and interested in sharing the information [

65]. The systematic literature review on practical applications of AHP by Ishizaka and Labib [

66] indicate that involving three to seven experts is common practice to ensure diverse input and maintain practical manageability. Some case studies demonstrate the use of larger groups in AHP (e.g., studies involving public participation in urban planning or large organizational decision making) [

67]. While a larger sample size can provide more diverse perspectives and improve the robustness of the decision, it also introduces challenges in terms of coordination, consistency, and analysis of the data [

68].

As stated by Dong et al. [

68], the selection of experts and the importance of their knowledge and expertise is crucial to ensure the quality of AHP outcomes. In this study, we applied purposive sampling with the target of sample size of 10 experts, which exceeds the minimal required sample size for AHP of 3–7 experts. Previous research recommended objective sampling, as this method can improve the reliability and quality of AHP analysis by focusing on the expertise and relevance of the participants rather than the number of respondents [

66,

67]. The choice of experts in the purposive sampling in AHP involved the deliberate selection of experts based on their relevant knowledge, experience, and ability to provide informed judgments on the management of product returns in e-commerce in Indonesia. The following criteria were applied for the purposive sampling in this study: (1) spatial scope—to be located in Indonesia; (2) time scope—to have at least 3 years of experience in making product returns in e-commerce; (3) to be familiar with the pairwise comparison concept.

The procedure consists of the following phases [

3]:

Step 1: Create hierarchical structure.

The first step includes identifying the hierarchical structure of the problem. The hierarchical framework comprises three levels: objective, standards, and options. The objective of the selection process is to identify the factors that the impact product returns in the reverse logistics of the Indonesian e-commerce business. This study introduces six key factors (from

Table 3) and alternatives (

Table 4) as potential solutions following a comprehensive assessment of the literature.

Figure 2 depicts the hierarchical structure of the criteria selection.

Step 2: Construct matrices through pairwise comparison.

In the following stage, the key factor weights are obtained through the pairwise comparisons. Upper-level urgency and criteria are assessed by performing paired comparisons to evaluate each criterion. This is based on the assessment of matrices performed by 10 experts. As mentioned above, we applied the purposive sampling. The spatial scope of the research was limited to the Indonesian e-commerce B2C market. Data were collected via survey form for pairwise comparison and interviews conducted online in March–April 2024. The paired comparison matrices are generated using the standardized comparison scale outlined in

Table 4. Let

} be the key factor set and

A be the evaluation matrix with relative weight (

) of the key factor, where

[

3].

Step 3: Normalized matrix and calculation of priority vector .

The normalization process begins by computing the total of values in each column. Hence, the normalization for the first column when

is specified as [

69]

The normalization for the

column is specified as [

45]

Then the normalization of matrix

is written as [

45]

The priority vector

W is constructed by taking the arithmetic mean of the rows of the normalized matrix

A [

45]:

Step 4: Calculation of .

The formula for computing the eigenvector of a matrix

A is specified as [

3]

is computed by taking the sum of the product of each element of the eigenvector with the sum of the columns of the pairwise matrix A.

Step 5: Consistency test for pairwise matrix.

Assessing the consistency of the pairwise matrix

A is a crucial step in AHP. It helps determine if the specific decision matrix should be accepted or rejected. Two parameters are computed to evaluate and confirm the coherence of the matrix, as outlined below [

3]:

The value of the random index (

RI) is contingent upon the number of key factor (

n). The predefined random index (

RI) values, as suggested by Saaty [

67], are presented in the subsequent

Table 5.

Step 6: Calculation of the final alternative value.

Calculation utilizing a weighted sum is necessary in this phase to obtain the final priority value for alternatives. The formula for the weighted total of alternative

n is described as follows, assuming m represents the number of key factors [

69]:

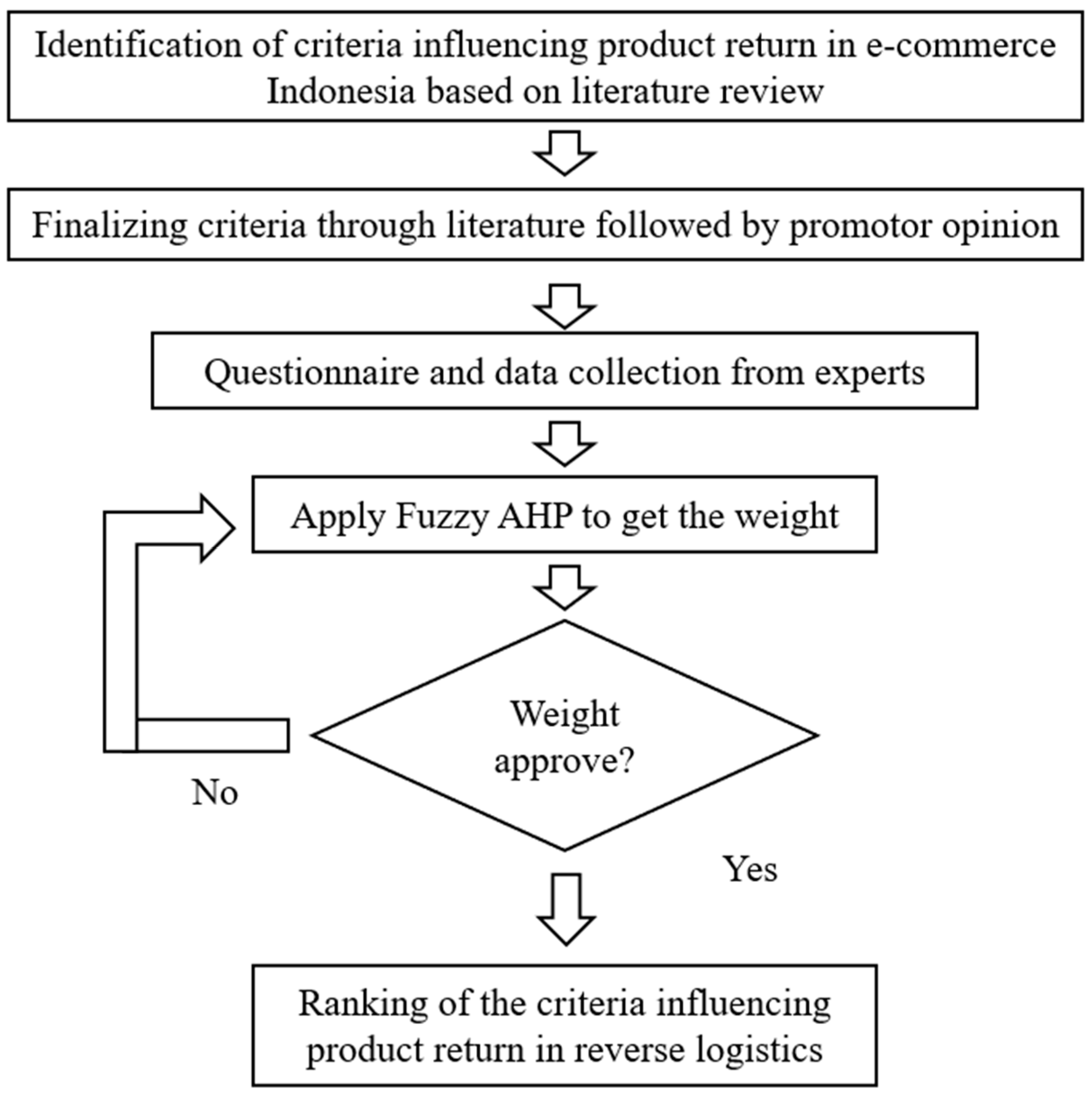

For the research methodology, this study employs a two-phase approach that is shown in

Figure 3.

4. Results

The AHP analysis aimed to rank the key factors influencing the product returns in Indonesian e-commerce and to link them with most suitable solutions to reduce the volume of returns. An e-commerce company can use the results to efficiently handle returns and improve customer satisfaction. Moreover, the act of prioritizing the key factors is crucial for understanding the concept of returns management in the context of Indonesian e-commerce.

This study follows the methodology shown in

Figure 3.

Phase 1: Selection Criterion Identification and Evaluation

The factors that affect product returns in reverse logistics in Indonesian e-commerce were identified and selected in the initial stage through critical literature research. Subsequently, these factors were assessed by experts using a questionnaire form. This study presents six parameters that have an influence on product returns in reverse logistics. The key factors encompass shipping and handling, timeliness, precision of product description, return policy, product quality, and order of fulfillment.

Phase 2: Application of AHP

In this step, the analytic hierarchy process (AHP) approach was used to prioritize the factors that impact product return in reverse logistics in the e-commerce industry in Indonesia. The 10 experts assessed the key factors and their alternatives as potential solutions. The selection of experts was based on the number of years of using e-commerce platform and the experiences of returning the purchased product.

Table 6 displays the pairwise comparison and decision matrix of the key factors, together with their estimated weight and ranking.

In order to answer the research question RQ1, we assessed by application of AHP the importance of factors that influence a customer’s experience when returning a product in e-commerce in Indonesia. As shown in

Table 6, the weightage value was used to rank the key factors in descending order. Product quality (QP) obtained the highest weightage, followed in descending order by procedure and guideline for returning items (PGR); level of order fulfillment (LOF); shipping and handling (SH); and precision of the product description (PPD). Punctuality (Pu) was ranked the lowest with respect to its importance in product return in reverse logistics from a consumer perspective.

In order to find the answer to RQ2, we assessed alternative solutions to find out those that are the most suitable to improve the customer’s experience and thus reduce returns in reverse logistics in e-commerce in Indonesia. Potential solutions were assessed based on all key factors, starting from SH and ending with LOF. Consequently, alternatives were ranked based on each individual criterion (as shown in

Table 7,

Table 8,

Table 9,

Table 10,

Table 11,

Table 12 and

Table 13).

After all the pairwise comparison matrices were completed, the value of each alternative was determined in the last phase of the computation by applying formula 9. The rank of alternatives was then displayed, as shown in

Table 13. The alternatives were prioritized in a decreasing sequence based on their weightage value. The alternative with the highest weightage was clear return policy (CRP), followed by standardized reverse logistics process (SRL), management awareness (MA), collaboration with logistics partners (CRL), IT implementation (IT), and establishing a good catalog (CAT), in that specific order.

5. Discussion

This study applied the AHP approach to identify key factors from the customer perspective that influence product returns in reverse logistics in Indonesian e-commerce. Furthermore, the most suitable solutions were linked. A clear return policy was ranked as the most important solution. This solution had a favorable weight to overcome issues related to the lack of the precision of product description (PPD), the procedures and guidelines for returning items (PGR), and the insufficient quality of the product (QP).

The standardization of reverse logistics procedures was ranked as the most preferable solution. This solution was deemed suitable to overcome the problems associated with shipping and handling (SH) and to ensure the quality of the product (QP). This aims to improve the management of return operations by developing their own protocols and standards. Standardizing practices in the field of reverse logistics has several benefits. The initial advantage of standardization is the improved visibility of returns. At the same time, it has the capacity to improve operational adaptability and boost operational effectiveness. Lastly, incorporating established procedures can help minimize ambiguity and discord in reverse logistics activities. To minimize ambiguity and uncertainties in reverse logistics, it is crucial to have a thorough comprehension of the procedures to control the flow of returns.

The third preferable solution is the enhancement of managerial awareness (MA). This demonstrates a high suitability to mitigate the issues related to lack of appropriate procedure and guidelines for returning items (PGR), troubles with the product quality (QP), and low level of order fulfillment (LOF). Returns management is not just an operational concern but also a strategic one. Companies that recognize this can better align their resources and create higher customer value, reduce costs, and enhance competitive advantage [

70]. There are studies that indicate that with the increasing automation of returns management processes in e-commerce, the system has the potential to work effectively even with low involvement of top managers [

71,

72,

73]. However, these studies do not take into account the perspective of customers and their satisfaction.

Engaging in collaboration with reverse logistics partners was the solution that was ranked fourth. This solution was most suitable to mitigate issues with the level of order fulfillment (LOF) and punctuality (Pu). Most previous studies proved that the collaboration with specialized logistics partners allowed for the improving of delivery time, as well as the accurateness and reliability of deliveries, especially in urban areas where customers might prefer to have multiple options to receive and eventually return products [

35]. Previous studies on the B2C market in e-commerce in other countries were not conclusive on the level of importance of this solution. For example, Naseem et al. [

10] have shown that establishing a favorable relationship with a third party logistics supplier was one of the top alternatives. On the contrary, Sirisawat and Kiatcharoenpol [

41] assessed its importance as relatively low.

Information technology ranked fifth among all the alternatives analyzed. The solution effectively addressed both order fulfillment level (LOF) and on-time performance (Pu) issues. To better manage product returns, companies must strengthen their ties with their supply chain partners through regular information exchange to improve real-time traceability. Furthermore, the use of data analytics and visibility technologies, including predictive forecasting, can improve collaboration and information sharing among multiple supply chain participants through the use of the RFID (radio frequency identification system). From the customer’s perspective, easy access to e-commerce delivery status information reduces uncertainty and allows for proactive management of product delivery and making returns. However, some researchers have highlighted that information technology can also negatively impact the customer experience when returning e-commerce products in the B2C market. This can happen when, due to extended automation (for example chatbots), poor platform design, and outdated information, customers may find it difficult to return and reach a real person for assistance, leading to frustration and dissatisfaction [

1].

The creation of catalog of products is the final solution to the issue of product returns in e-commerce on the B2C market in Indonesia. By creating a catalog of items on the e-commerce platform, it is feasible to effectively minimize the number of product returns caused by customers obtaining the wrong item. Using high-resolution images captured from diverse angles, along with a comprehensive description detailing the size, colors, and materials, can help to reduce the volume of returns. In addition, sellers can employ product information management systems to ensure that product descriptions are accurate and uniform across any e-commerce platform.

6. Conclusions

Despite the very large size of the market, research on e-commerce in the business-to-customer (B2C) market in Indonesia is underrepresented in the literature. This paper aimed to identify key factors from the customer’s perspective that influence product returns in B2C in Indonesian e-commerce. Furthermore, we explored the suitability of potential solutions derived from a critical review of the literature in regard to mitigate the issues related to the identified key factors. The AHP is applied to cope with information uncertainty in multi-criteria decision making. In the context of the research gap diagnosed in the Introduction, this article provides knowledge on product returns management in relation to the Indonesian e-commerce market. The geographical scope is relevant, as the size of population and rapid growth of the Internet and mobile accessibility in Indonesia increases the scale of the return problem, hence the need to address this in research. The novelty of this study comes from the focus on the customer’s perspective on product returns in B2C when shopping online and the spatial scope. The novel contribution to theory is the ranking of key factors that influence the customer’s experience when returning products in the context of the Indonesian e-commerce in B2C market (answer to RQ1). This study identified six factors that influence product returns in the reverse logistics of Indonesian e-commerce. They were prioritized using the analytical hierarchy approach (AHP). In terms of key factors, the results show that product quality (QP) received the highest importance, followed by the procedure and return guideline (PGR), the level of order fulfillment (LOF), the shipping and handling (SH), the precision of the product description (PPD), and punctuality (PU). To answer RQ2, we analyzed the set of suitable solutions to reduce the volume of returns. The results show that the clear return policy (CRP) had the highest level of importance, followed by the implementation of a standardized reverse logistics process (SRL), management awareness (MA), collaboration with logistics partners (CRL), IT implementation (IT), and product catalog of goods (CAT).

These results can also be useful for managers in e-commerce in Indonesia to better understand the customer’s perspective and proactively implement solutions that help to reduce the volume of returns. The results support the choice of the most suitable actions to mitigate the issues related to six key factors that influence the customers experience and satisfaction of customers when making a return in the context of Indonesian e-commerce in the B2C market.

Limitation and Future Research Direction

Despite the contribution to identify key factors influencing product return in Indonesian e-commerce, this study has limitations. First, the key factors were obtained from previously published scholarly studies. As these factors were not originally intended for the Indonesian market, it is probable that they may contain biases. Although attempts have been made to select reliable sources, it is not feasible to entirely eliminate the potential for biases. The methodological choice adopted to address the formulated research problem is one of the multi-criteria analysis methods. It should be emphasized at this point that the results obtained were directly determined by the data adopted. Hence, in the case of AHP, as in other multi-criteria methods, the step of assigning objective evaluations is crucial for the value of the results and their subsequent interpretation. The group of ten experts, who are frequent online shoppers on e-commerce platforms and have previous experience with product returns, assessed the key factors and their possible alternatives. Thus, there might be other factors that had not been considered in this research.

This study specifically examined the factors that influence product returns in reverse logistics in Indonesian e-commerce, with an emphasis on the customer’s viewpoint. However, a future study might explore the criteria from the company’s perspective and compare the findings of both studies. Moreover, the proposed framework outcome may be compared to the outcomes of other methodologies, such as ANP and ELECTRE, which can be used for future analysis.