Segments of Environmental Concern in Kuwait

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Environmental Attitudes Inventory (EAI) Scale

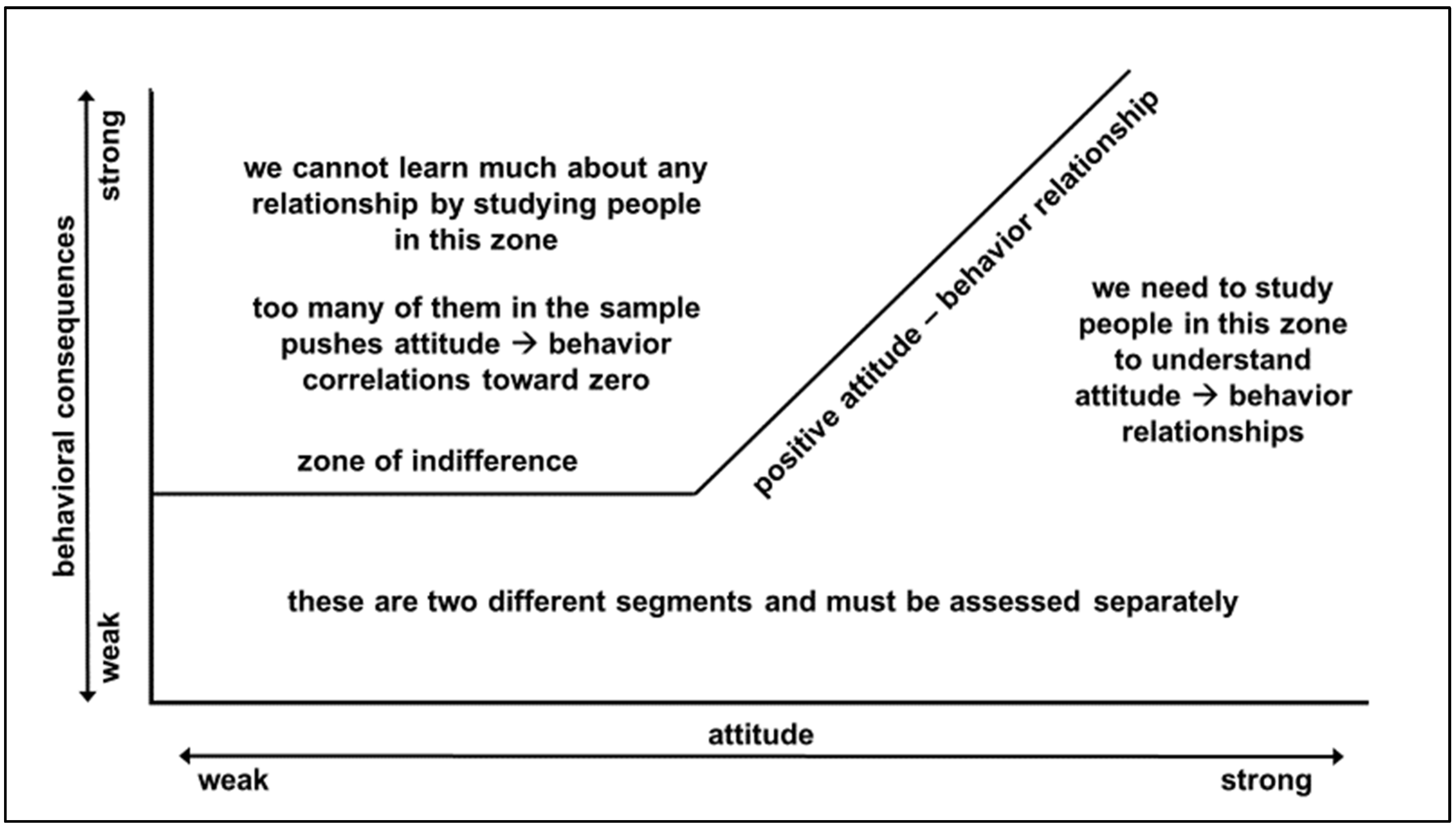

2.2. Environmental Consciousness and the Attitude–Behavior Gap

2.3. Conceptualizing Concerns of Green-Oriented Consumers

3. Methodology

Sampling and Sample Characteristics

4. Results

4.1. Mapping Attitude Dimensions to the Broader Sustainability Debate

- f1: Unconcerned about environment: no information about views on socio-economic axis (q19, q21, and q22)

- f2: Eco-centered/deep ecology: environment > socio-economic (q7, q8, and q9)

- f3: Techno-centered approach (q10, q11r, and q12)

- f4: Humans must adapt to nature (q14, q17, and q20)

- f5: Willing to engage (q4r and q6r)

- f6: Socialist cornucopia: social reform > environment (q15, q16, and q18)

- f7: Libertarian: not specified about environment, but anti-government intervention (q1 and q2)

4.2. Identifying Attitude Segments

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Questionnaire Item | Mean | Std. Dev |

|---|---|---|

| f1: Unconcerned about environment: no information about views on socio-economic axis (q19, q21, and q22) | ||

| q22: It does not make me sad to see recyclable plastic go to waste and destroy the natural environment | 1.98 | 1.189 |

| q21: It does not make me sad to see natural environments destroyed | 1.95 | 1.184 |

| q19: I do not believe protecting the environment is an important issue | 1.99 | 1.191 |

| f2: Eco-centered/deep ecology: environment > socio-economic (q7, q8, and q9) | ||

| q9: We should protect the environment even if it means people’s welfare will suffer | 3.15 | 1.165 |

| q7: Conservation is important even if it lowers people’s standard of living | 3.18 | 1.153 |

| q8: We need to keep the Arabian Gulf clean to protect the environment and not as places for people to enjoy water sports | 3.45 | 1.241 |

| f3: Techno-centered approach (q10, q11r, and q12) | ||

| q10: Science and technology will eventually solve our problems with pollution and diminishing resources | 3.33 | 1.146 |

| q12: Modern science will solve our environmental problems | 3.34 | 1.145 |

| q11r: The belief that advances in science and technology can solve our environmental problems is completely wrong and misguided | 3.22 | 1.184 |

| f4: Humans must adapt to nature (q14, q17, and q20) | ||

| q20: Despite our special abilities, humans are still subject to the laws of nature | 3.26 | 1.143 |

| q17: Humans do not have the right to damage the environment just to get greater benefits and promote economic prosperity | 3.48 | 1.207 |

| q14: Human beings should not tamper with nature even when nature is uncomfortable and inconvenient for us | 3.17 | 1.166 |

| f5: Willing to engage (q4r and q6r) | ||

| q6r: I would not want to donate money to support an environmentalist cause | 3.48 | 1.146 |

| q4r: I would not get involved in an environmentalist organization | 3.57 | 1.217 |

| f6: Socialist cornucopia: social reform > environment (q15, q16, and q18) | ||

| q16: Protecting people’s jobs is more important than protecting the environment | 2.70 | 1.103 |

| q15: When nature is uncomfortable and inconvenient for humans, we have every right to change and remake it to suit ourselves | 3.05 | 1.187 |

| q18: The benefits of modern consumer products are more important than the pollution that results from their production and use | 2.45 | 1.151 |

| f7: Libertarian: not specified about environment, but anti-government intervention (q1 and q2) | ||

| q2: I am opposed to governments controlling and regulating the way raw materials are used to try and make them last longer | 2.96 | 1.141 |

| q1: Factories and industries should be able to use raw materials rather than recycled ones if this leads to lower prices and costs, even if it means the raw materials will eventually be used up | 2.68 | 1.211 |

Appendix B

| item | f1 | f2 | f3 | f4 | f5 | f6 | f7 | Comm. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| q9.22 | 0.874 | 0.788 | ||||||

| q9.21 | 0.883 | 0.808 | ||||||

| q9.19 | 0.737 | 0.672 | ||||||

| q9.9 | 0.780 | 0.633 | ||||||

| q9.7 | 0.724 | 0.551 | ||||||

| q9.8 | 0.681 | 0.586 | ||||||

| q9.10 | 0.761 | 0.663 | ||||||

| q9.12 | 0.769 | 0.678 | ||||||

| q9.11r | 0.533 | 0.543 | ||||||

| q9.20 | 0.758 | 0.618 | ||||||

| q9.17 | 0.695 | 0.592 | ||||||

| q9.14 | 0.526 | 0.462 | ||||||

| q9.6r | 0.771 | 0.653 | ||||||

| q9.4r | 0.764 | 0.635 | ||||||

| q9.16 | 0.685 | 0.568 | ||||||

| q9.15 | 0.684 | 0.612 | ||||||

| q9.18 | 0.434 | 0.530 | 0.540 | |||||

| q9.2 | 0.836 | 0.723 | ||||||

| q9.1 | 0.738 | 0.643 | ||||||

| rotated % variance | 13.020 | 10.708 | 8.456 | 7.874 | 7.801 | 7.666 | 7.456 |

References

- Franzen, A.; Vogl, D. Two decades of measuring environmental attitudes: A comparative analysis of 33 countries. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 1001–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, L.B.; Rice, R.E.; Gustafson, A.; Goldberg, M.H. Relationships among environmental attitudes, environmental efficacy, and pro-environmental behaviors across and within 11 countries. Environ. Behav. 2022, 54, 1063–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisano, I.; Lubell, M. Environmental behavior in cross-national perspective: A multilevel analysis of 30 countries. Environ. Behav. 2017, 49, 31–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golob, U.; Kronegger, L. Environmental consciousness of European consumers: A segmentation-based study. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 221, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmazsoy, B.; Schmidbauer, H.; Rosch, A. Green segmentation: A cross-national study. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2015, 33, 961–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.P. Consumers’ purchase behaviour and green marketing: A synthesis, review and agenda. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2021, 45, 1217–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milfont, T.L.; Duckitt, J. The environmental attitudes inventory: A valid and reliable measure to assess the structure of environmental attitudes. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlMenhali, E.A.; Khalid, K.; Iyanna, S. Testing the psychometric properties of the Environmental Attitudes Inventory on undergraduate students in the Arab context: A test-retest approach. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0195250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopwood, B.; Mellor, M.; O’Brien, G. Sustainable development: Mapping different approaches. Sustain. Dev. 2005, 13, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whyte, P.; Lamberton, G. Conceptualising sustainability using a cognitive mapping method. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemper, J.A.; Ballantine, P.W. What do we mean by sustainability marketing? J. Mark. Manag. 2019, 35, 277–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Climate-data.org. Kuwait City Climate. 2023. Available online: https://en.climate-data.org/asia/kuwait/kuwait-city/kuwait-city-4807/ (accessed on 17 July 2024).

- Abulibdeh, A.; Zaidan, E.; Al-Saidi, M. Development drivers of the water-energy-food nexus in the Gulf Cooperation Council region. Dev. Pract. 2019, 29, 582–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgomeo, E.; Jägerskog, A.; Talbi, A.; Wijnen, M.; Hejazi, M.; Miralles-Wilhelm, F. The Water-Energy-Food Nexus in the Middle East and North Africa; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/927041530193545554/pdf/127749-WP-28-6-2018-1-16-49-WeBook.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2023).

- Al-Saidi, M. Cooperation or competition? State environmental relations and the SDGs agenda in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) region. Environ. Dev. 2021, 37, 100581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AFED (Arab Forum for Environment and Development). Environmental Education for Sustainable Development in Arab Countries. In 2019 Report of the Arab Forum for Environment and Development; Saab, N., Badran, A., Sadik, A., Eds.; AFED: Beirut, Lebanon, 2019; Available online: http://www.afedonline.org/en/reports/details/environmental-education-for-sustainable-development-in-arab-countries (accessed on 15 November 2023).

- Chen, M.F. Selecting environmental psychology theories to predict people’s consumption intention of locally produced organic foods. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2020, 44, 455–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, J.; Szuster, B.W. The new environmental paradigm scale: Reassessing the operationalization of contemporary environmentalism. J. Environ. Educ. 2019, 50, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajdukovic, I.; Gilibert, D.; Fointiat, V. Structural confirmation of the 24-item Environmental Attitude Inventory/Confirmación estructural del Inventario de Actitudes Ambientales de 24 ítems. Psyecology 2019, 10, 184–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ienna, M.; Rofe, A.; Gendi, M.; Douglas, H.E.; Kelly, M.; Hayward, M.W.; Callen, A.; Klop-Toker, K.; Scanlon, R.J.; Howell, L.G.; et al. The relative role of knowledge and empathy in predicting pro-environmental attitudes and behavior. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawcroft, L.J.; Milfont, T.L. The use (and abuse) of the new environmental paradigm scale over the last 30 years: A meta-analysis. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milfont, T.L.; Schultz, P.W. Culture and the natural environment. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2016, 8, 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosler, H.J.; Martens, T. Designing environmental campaigns by using agent-based simulations: Strategies for changing environmental attitudes. J. Environ. Manag. 2008, 88, 805–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, P.; Chahal, H.S. Consumer attitude towards green products: Revisiting the profile of green consumers using segmentation approach. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2021, 32, 902–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Doorn, J.; Verhoef, P.C.; Bijmolt, T.H. The importance of non-linear relationships between attitude and behaviour in policy research. J. Consum. Policy 2007, 30, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, G.A. Framing a model for green buying behavior of Indian consumers: From the lenses of the theory of planned behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 295, 126487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechler, C.J.; Tormala, Z.L.; Rucker, D.D. The attitude–behavior relationship revisited. Psychol. Sci. 2021, 32, 1285–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNDP. Sustainable Development Goals: The SDGs in Action. 2022. Available online: https://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/sustainable-development-goals.html (accessed on 7 July 2024).

- Clune, W.H.; Zehnder, A.J. The Evolution of Sustainability Models, from Descriptive, to Strategic, to the Three Pillars Framework for Applied Solutions. Sustain. Sci. 2020, 15, 1001–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalampira, E.S.; Nastis, S.A. Mapping sustainable development goals: A network analysis framework. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 28, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purvis, B.; Mao, Y.; Robinson, D. Three pillars of sustainability: In search of conceptual origins. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavalittumrong, P.; Speece, M. Three-Pillar Sustainability and Brand Image: A Qualitative Investigation in Thailand’s Household Durables Industry. Sustainability 2022, 14, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED). Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987; Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/5987our-common-future.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- IUCN; UNEP; WWF. Caring for the Earth: A Strategy for Sustainable Living; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- IUCN; UNEP; WWF. World Conservation Strategy: Living Resource Conservation for Sustainable Development; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher, E. Small Is Beautiful: Economics as If People Mattered; Abacus: London, UK, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Kemper, J.A.; Hall, C.M.; Ballantine, P.W. Marketing and sustainability: Business as usual or changing worldviews? Sustainability 2019, 11, 780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemper, J.A.; Ballantine, P.W.; Hall, C.M. Sustainability worldviews of marketing academics: A segmentation analysis and implications for professional development. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 271, 122568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, J.N.; Parvatiyar, A. Sustainable Marketing: Market-Driving, Not Market-Driven. J. Macromarketing 2021, 41, 150–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K.; Habib, R.; Hardisty, D.J. How to SHIFT consumer behaviors to be more sustainable: A literature review and guiding framework. J. Mark. 2019, 83, 22–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, J.W.; Toms, L.C.; Green, K.W. Market-oriented sustainability: Moderating impact of stakeholder involvement. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2014, 114, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.W.; Wooliscroft, B.; Higham, J. Sustainable market orientation: A new approach to managing marketing strategy. J. Macromarketing 2010, 30, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- hofstede-insights.com. Tools: Compare Countries. 2022. Available online: https://www.hofstede-insights.com/country-comparison/ (accessed on 15 April 2022).

- Sutton, S.G.; Gyuris, E. Optimizing the environmental attitudes inventory: Establishing a baseline of change in students’ attitudes. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2015, 16, 16–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingues, R.B.; Gonçalves, G. Assessing environmental attitudes in Portugal using a new short version of the Environmental Attitudes Inventory. Curr. Psychol. 2018, 39, 629–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, I.; The Persian Gulf Cultural World. Maps and Statistics Collection, The Gulf/2000 Project, Columbia University. 2008. Available online: https://gulf2000.columbia.edu/images/maps/GulfCultralWorld0804_lg.png (accessed on 17 July 2024).

- Keshavarzian, A. From Port Cities to Cities with Ports: Toward a Multiscalar History of Persian Gulf Urbanism in the Twentieth Century. In Gateways to the World: Port Cities in the Persian Gulf; Kamrava, M., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; pp. 19–41. [Google Scholar]

- Michael, H. The Wages of Oil: Parliaments and Economic Development in Kuwait and the UAE; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- van Meter, K. Methodological and design issues: Techniques for assessing the representatives of snowball samples. In The Collection and Interpretation of Data from Hidden Populations; Lambart, E.Y., Ed.; NIDA Research Monograph; National Institute on Drug Abuse: Rockville, MD, USA, 1990; Volume 98, pp. 31–43. Available online: https://archives.nida.nih.gov/sites/default/files/monograph98.pdf#page=38 (accessed on 17 July 2024).

- Kirchherr, J.; Charles, K. Enhancing the sample diversity of snowball samples: Recommendations from a research project on anti-dam movements in Southeast Asia. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0201710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, A.R.; Shanine, K.K.; Leon, M.R.; Whitman, M.V. Student-recruited samples in organizational research: A review, analysis, and guidelines for future research. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2014, 87, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadler, G.R.; Lee, H.C.; Lim, R.S.H.; Fullerton, J. Recruitment of hard-to-reach population subgroups via adaptations of the snowball sampling strategy. Nurs. Health Sci. 2010, 12, 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abalkhail, J.M.; Allan, B. ‘Wasta’ and women’s careers in the Arab Gulf States. Gend. Manag. Int. J. 2016, 31, 162–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Salem, A.; Speece, M. Women in leadership in Kuwait: A research agenda. Gend. Manag. Int. J. 2017, 32, 141–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, E.; Buil, I.; de Chernatony, L.; Hogan, M. Who ‘likes’ you...and why? A typology of Facebook fans: From ‘fan’-atics and self-expressives to utilitarians and authentics. J. Advert. Res. 2014, 54, 92–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljamal, A.; Speece, M.; Bagnied, M. Sustainable policy for water pricing in Kuwait. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljamal, A.; Speece, M.; Bagnied, M. Understanding resistance to reductions in water subsidies in Kuwait. Local Environ. 2022, 27, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Description | |

|---|---|

| segment1 | Very unconcerned about environment. No other dimension goes beyond fairly weak attitudes, whether positive or negative. Strongly status quo in [9]. |

| segment2 | Strong thinking that humans must adapt to nature and strong thinking that environment takes priority over socio-economic concerns. This is deep ecology in [9]. |

| segment3 | Mostly fairly strong attitudes, positive for willing to engage, socio-economic, and libertarian; somewhat strong for eco-oriented. Strong disagreement about being unconcerned with environment. This borders on transformation in [9]. |

| segment4 | Strong to somewhat strong disagreement with most elements. Slightly willing to engage and disagree with a libertarian approach. Citizens and the government should both do something but nothing radical. Status quo bordering on reform in [9]. |

| segment5 | Fairly strong disagreement that they are not concerned with environment but not willing to get engaged. Strongest belief of any segment that technology can solve things. Status quo bordering on reform in [9]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Speece, M.; Aljamal, A.; Bagnied, M. Segments of Environmental Concern in Kuwait. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7080. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16167080

Speece M, Aljamal A, Bagnied M. Segments of Environmental Concern in Kuwait. Sustainability. 2024; 16(16):7080. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16167080

Chicago/Turabian StyleSpeece, Mark, Ali Aljamal, and Mohsen Bagnied. 2024. "Segments of Environmental Concern in Kuwait" Sustainability 16, no. 16: 7080. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16167080

APA StyleSpeece, M., Aljamal, A., & Bagnied, M. (2024). Segments of Environmental Concern in Kuwait. Sustainability, 16(16), 7080. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16167080