Analyzing Managerial Skills for Employability in Graduate Students in Economics, Administration and Accounting Sciences

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Employability Skills

1.2. Current Labor Market

1.3. Employability

1.4. Education

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Respondent Items (English) | Respondent Items (Spanish) |

| Fundamental Skills | Habilidades Fundamentales |

| Communicate | Comunicación |

| 1. Read and understand information presented in a variety of forms (e.g., words, graphs, charts, diagrams) | 1. Leer y comprender información presentada en una variedad de formas (p. ej., palabras, gráficos, cuadros, diagramas) |

| 2. Write and speak so others pay attention and understand | 2. Al escribir y hablar, logro que los demás presten atención y comprendan |

| 3. Listen and ask questions to understand and appreciate the points of view of others | 3. Escucho y hago preguntas para comprender y apreciar los puntos de vista de los demás |

| 4. Share information using a range of information and communications technologies (e.g., voice, e-mail, computers) | 4. Comparto información utilizando una variedad de tecnologías de la información y las comunicaciones (p. ej., mensajes de voz, correo electrónico, computadoras) |

| 5. Use relevant scientific, technological and mathematical knowledge and skills to explain or clarify ideas | 5. Utilizo conocimientos, destrezas, información científica, habilidades tecnológicas y matemáticas pertinentes para explicar o aclarar ideas |

| Manage Information | Gestión de Información |

| 6. Locate, gather and organize information using appropriate technology and information systems | 6. Localizo, recopilo y organizo información utilizando la tecnología adecuada y sistemas de información |

| 7. Access, analyze and apply knowledge and skills from various disciplines (e.g., the arts, languages, science, technology, mathematics, social sciences, and the humanities) | 7. Accedo, analizo y aplico conocimientos y habilidades de diversas disciplinas (p. ej., las artes, los idiomas, la ciencia, la tecnología, las matemáticas, las 4 y las humanidades) |

| Use Numbers | Uso de Números |

| 8. Decide what needs to be measured or calculated | 8. Al usar números, decido qué debe medirse o calcularse |

| 9. Observe and record data using appropriate methods, tools and technology | 9. Observo y registro datos usando métodos, herramientas y tecnología apropiados |

| 10. Make estimates and verify calculations | 10. Hago estimaciones, pronósticos y verifico los cálculos |

| Think & Solve Problems | Pensar y Resolver Problemas |

| 11. Assess situations and identify problems | 11. Evalúo situaciones e identifico problemas |

| 12. Seek different points of view and evaluate them based on facts | 12. Busco diferentes puntos de vista y evalúo con base en hechos |

| 13. Recognize the human, interpersonal, technical, scientific and mathematical dimensions of a problem | 13. Reconozco las dimensiones humanas, interpersonales, técnicas, científicas y matemáticas de un problema |

| 14. Identify the root cause of a problem | 14. Identifico la causa raíz de un problema |

| 15. Be creative and innovative in exploring possible solutions | 15. Soy creativo e innovador al explorar posibles soluciones |

| 16. Readily use science, technology and mathematics as ways to think, gain and share knowledge, solve problems and make decisions | 16. Utilizo fácilmente la ciencia, la tecnología y las matemáticas como formas de pensar, obtener y compartir conocimientos, resolver problemas y tomar decisiones |

| 17. Evaluate solutions to make recommendations or decisions | 17. Evalúo soluciones para hacer recomendaciones que mejoren la toma de decisiones respecto a problemas y situaciones |

| 18. Implement solutions | 18. Soy capaz de implementar soluciones |

| 19. Check to see if a solution works, and act on opportunities for improvement | 19. Compruebo si una solución funciona y actúo sobre las oportunidades de mejora |

| Personal Management Skills | Habilidades de Gestión Personal |

| Demonstrate Positive Attitudes & Behaviors | Demuestra Actitud y Comportamientos Positivos |

| 20. Feel good about yourself and be confident | 20. Me siento bien conmigo mismo y tengo confianza |

| 21. Deal with people, problems and situations with honesty, integrity and personal ethics | 21. Soy capaz de tratar con personas, problemas y situaciones con honestidad, integridad y ética personal |

| 22. Recognize your own and other people’s good efforts | 22. Reconozco los buenos esfuerzos propios y de otras personas |

| 23. Take care of your personal health | 23. Cuido la salud personal |

| 24. Show interest, initiative and effort | 24. Muestro interés, iniciativa y esfuerzo por el trabajo y los resultados |

| Be Responsible | Responsabilidad |

| 25. Set goals and priorities balancing work and personal life | 25. Puedo establecer metas y prioridades equilibrando el trabajo y la vida personal |

| 26. Plan and manage time, money and other resources to achieve goals | 26. Puedo planificar y administrar el tiempo, el dinero y otros recursos para alcanzar las metas |

| 27. Assess, weigh and manage risk | 27. Puedo evaluar, sopesar y gestionar el riesgo |

| 28. Be accountable for your actions and the actions of your group | 28. Puedo ser responsable de mis acciones y las acciones de mi grupo |

| 29. Be socially responsible and contribute to your community | 29. Soy socialmente responsable y contribuyo a mi comunidad |

| Be Adaptable | Adaptabilidad |

| 30. Work independently or as a part of a team | 30. Soy capaz de trabajar de forma independiente y como parte de un equipo |

| 31. Carry out multiple tasks or projects | 31. Puedo llevar a cabo múltiples tareas o proyectos |

| 32. Be innovative and resourceful: identify and suggest alternative ways to achieve goals and get the job done | 32. Soy innovador e ingenioso: identifico y sugiero formas alternativas para alcanzar las metas y hacer el trabajo |

| 33. Be open and respond constructively to change | 33. Estoy abierto y respondo constructivamente al cambio |

| 34. Learn from your mistakes and accept feedback | 34. Aprendo de mis errores y acepto comentarios |

| 35. Cope with uncertainty | 35. Soy capaz de afrontar condiciones de incertidumbre |

| Learn Continuously | Aprendizaje Continuo |

| 36. Be willing to continuously learn and grow | 36. Estoy dispuesto a aprender y crecer continuamente |

| 37. Assess personal strengths and areas for development | 37. Soy capaz de evaluar las fortalezas personales y mis áreas de desarrollo |

| 38. Set your own learning goals | 38. Puedo establecer mis propios objetivos de aprendizaje |

| 39. Identify and access learning sources and opportunities | 39. Soy capaz de identificar y de acceder a fuentes y oportunidades de aprendizaje |

| 40. Plan for and achieve your learning goals | 40. Puedo planificar y lograr mis objetivos de aprendizaje |

| Work Safely | Trabajar de Manera Segura |

| 41. Be aware of personal and group health and safety practices and procedures, and act in accordance with these | 41. Puedo trabajar de forma segura, estoy al tanto de las prácticas, procedimientos de salud y seguridad personal, grupal, y actúo en conformidad a estos |

| Teamwork Skills | Habilidades de Trabajo en Equipo |

| Work with Others | Trabajar con otros |

| 42. Understand and work within the dynamics of a group | 42. Entiendo las necesidades de los miembros del equipo y se me facilita el trabajo dentro de la dinámica de un grupo |

| 43. Ensure that a team’s purpose and objectives are clear | 43. Me aseguro de que el propósito y los objetivos de mi equipo sean claros |

| 44. Be flexible: respect, be open to and supportive of the thoughts, opinions and contributions of others in a group | 44. Soy flexible: soy respetuoso, abierto y también apoyo los pensamientos, opiniones y contribuciones de los demás en un grupo |

| 45. Recognize and respect people’s diversity, individual differences and perspectives | 45. Reconozco y respeto la diversidad de las personas, las diferencias individuales y las perspectivas |

| 46. Accept and provide feedback in a constructive and considerate manner | 46. Acepto y proporciono comentarios de manera constructiva y considerada |

| 47. Contribute to a team by sharing information and expertise | 47. Puedo contribuir a un equipo compartiendo información y experiencia |

| 48. Lead or support when appropriate, motivating a group for high performance | 48. Soy capaz de liderar o apoyar cuando sea apropiado, motivando a un grupo para un alto desempeño |

| 49. Understand the role of conflict in a group to reach solutions | 49. Comprendo cómo gestionar el conflicto en un grupo para lograr soluciones |

| 50. Manage and resolve conflict when appropriate | 50. Soy capaz de manejar y resolver conflictos cuando sea apropiado |

| Participate in Projects & Tasks | Participar en Proyectos y Tareas |

| 51. Plan, design or carry out a project or task from start to finish with well-defined objectives and outcomes | 51. Puedo planificar, diseñar o llevar a cabo un proyecto o tarea de principio a fin con objetivos y resultados bien definidos |

| 52. Develop a plan, seek feedback, test, revise and implement | 52. Puedo desarrollar un plan, buscar retroalimentación, probar, revisar e implementar |

| 53. Work to agreed quality standards and specifications | 53. Puedo trabajar según los estándares y especificaciones de calidad acordados |

| 54. Select and use appropriate tools and technology for a task or project | 54. Soy capaz de seleccionar y utilizar las herramientas y la tecnología apropiadas para una tarea o proyecto |

| 55. Adapt to changing requirements and information | 55. Puedo adaptarme a los requisitos y a información cambiante |

| 56. Continuously monitor the success of a project or task and identify ways to improve | 56. Puedo monitorear continuamente el éxito de un proyecto o tarea e identificar formas de mejorar |

References

- Sunardi, S.; Purnomo, P.; Sutadji, E. Employability skills measurement model’s of vocational student. AIP Conf. Proc. 2016, 1778, 030043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callohuanca, J.; Tantalean, L. Adaptación y validación de una escala para medir las habilidades gerenciales. An. Científicos 2020, 81, 33–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainga, W.; Murphy-Braynen, M.B.; Moxey, R.; Quddus, S.A. Graduate Employability of Business Students. Adm. Sci. 2022, 12, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, T. Desenredando la conversación sobre habilidades blandas. Dialogue 2016, 974, 28. Available online: https://acortar.link/pmQ0PH (accessed on 8 July 2024).

- Vázquez-González, L.; Clara-Zafra, M.; Céspedes-Gallegos, S.; Ceja-Romay, S.; Pacheco-López, E. Estudio sobre habilidades blandas en estudiantes universitarios: El caso del TECNM Coatzacoalcos. IPSA Sci. Rev. Científica Multidiscip. 2022, 7, 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macpherson, E.; Rizk, J. Essential Skills for Learning and Working; Conference Board of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2022; pp. 1–18. Available online: https://fsc-ccf.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/FSC_VRST_essential-skills-for-learning-and-working.pdf (accessed on 8 July 2024).

- Tito, M.D.; Serrano, B. Development of soft skills an alternative to the shortage of human talent. Innova Res. J. 2016, 1, 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín Marín, J.A. Los Entornos Virtuales de Aprendizaje. In Innnovación Educativa Para Una Educación Transformadora; Dykinson, S.L.: Madrid, Spain, 2022; pp. 155–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarta, I.M.; Suwintana, I.K. The new framework of employability skills for digital business. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1833, 012034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juárez Martínez, A.; González Fernández, M. La construcción de las competencias genéricas en el nivel superior. Cuad. Educ. Desarro. 2018, 91, 1–16. Available online: https://www.eumed.net/rev/atlante/2018/01/competencias-genericas.zip (accessed on 8 July 2024).

- Blair, P.; Deming, D. Structural increases in demand for skill after the great recession. AEA Pap. Proc. 2020, 110, 362–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Álvarez, J.; Vázquez-Rodríguez, A.; Quiroga-Carrillo, A.; Priegue Caamaño, D. Transversal Competencies for Employability in University Graduates: A Systematic Review from the Employers’ Perspective. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras-Barraza, N.; Espinosa-Cristia, J.F.; Salazar-Sepulveda, G.; Vega-Muñoz, A.; Ariza-Montes, A. A Scientometric Systematic Review of Entrepreneurial Wellbeing Knowledge Production. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 641465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rego, M.A.S.; Sáez-Gambín, D.; González-Geraldo, J.L.; García-Romero, D. Transversal Competences and Employability of University Students: Converging towards Service-Learning. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andino-González, P. Habilidades del administrador de empresas desde una perspectiva del mercado laboral actual. J. Manag. Bus. Stud. 2022, 4, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, L.M.; Silva, M.B.; Hidrobo, C.C.; Rincón, D.C.; Fuentes, G.Y.; Quintero, Y.A. Formación en Habilidades Blandas en Instituciones de Educación Superior: Reflexiones Educativas, Sociales y Políticas, 1st ed.; Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe CEPAL, Ed.; Naciones Unidas: New York, NY, USA, 2021; Volume 1, Available online: https://biblioteca-cum.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/F/?func=direct&doc_number=102284&local_base=UNM01 (accessed on 8 July 2024).

- Rodchenko, V.; Rekun, G.; Fedoryshyna, L.; Roshchin, I.; Gazarian, S. The effectiveness of human capital in the context of the digital transformation of the economy: The case of ukraine. J. East. Eur. Cent. Asian Res. 2021, 8, 202–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, I.A.; Odinaev, A.M.; Pulyaeva, V.N.; Gibadullin, A.A.; Vlasov, A.V. The transformation of human capital during the transition to a digital environment. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1515, 032024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sima, V.; Gheorghe, I.G.; Subić, J.; Nancu, D. Influences of the industry 4.0 revolution on the human capital development and consumer behavior: A systematic review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borowiecki, R.; Olesinski, Z.; Rzepka, A.; Hys, K. Development of Teal Organisations in Economy 4.0: An Empirical Research. Eur. Res. Stud. J. 2021, XXIV, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andino-González, P. Estudio Bibliométrico sobre empleabilidad. Ad-Gnosis 2023, 12, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vos, A.; Jacobs, S.; Verbruggen, M. Career transitions and employability. J. Vocat. Behav. 2021, 126, 103475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrier, A.; De Cuyper, N.; Akkermans, J. The winner takes it all, the loser has to fall: Provoking the agency perspective in employability research. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2018, 28, 511–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, M. Forms of Graduate Capital and their Relationship to Graduate Employability. Educ. Train. 2017, 59, 338–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organización de las Naciones Unidas [ONU]. Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible (ODS). Rev. De La Univ. De La Salle 2016, 70, 141. Available online: https://www.fuhem.es/media/cdv/file/biblioteca/revista_papeles/140/ODS-revision-critica-C.Gomez.pdf (accessed on 8 July 2024).

- UNESCO. Education for Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). In Proceedings of the European Conference on Educational Research 2017, Copenhagen, Denmark, 22–25 August 2017; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000252423 (accessed on 8 July 2024).

- Suárez-Lantarón, B. Empleabilidad: Análisis del concepto. Rev. Investig. Educ. 2016, 14, 67–84. Available online: https://reined.webs.uvigo.es/index.php/reined/article/view/225/247 (accessed on 8 July 2024).

- Guilbert, L.; Bernaud, J.L.; Gouvernet, B.; Rossier, J. Employability: Review and research prospects. Int. J. Educ. Vocat. Guid. 2015, 16, 69–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yorke, M. Employability: Aligning the message, the medium and academic values. J. Teach. Learn. Grad. Employab. 2010, 1, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thijssen, J.G.L.; Van Der Heijden, B.I.J.M.; Rocco, T.S. Toward the employability-link model: Current employment transition to future employment perspectives. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2008, 7, 165–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, E.; Nelissen, J.; De Cuyper, N.; Forrier, A.; Verbruggen, M.; De Witte, H. Employability Capital: A Conceptual Framework Tested through Expert Analysis. J. Career Dev. 2019, 46, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botero Sarassa, J.; Rentería Pérez, E. Empleabilidad y trabajo del profesorado universitario. Una revisión del Campo. Rev. Pensam. Investig. Soc. 2019, 19, e-2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idkhan, A.M.; Syam, H.; Sunardi, H.A.H. The employability skills of engineering students’: Assessment at the university. Int. J. Instr. 2021, 14, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, G.Y.; Moreno-Murcia, L.M.; Rincón-Tellez, D.C.; Silva-Garcia, M.B. Evaluation of soft skills in higher education. Form. Univ. 2021, 14, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ustundag, A.; Cevikcan, E. Lean Production Systems for Industry 4.0. In Springer Series in Advanced Manufacturing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, P.; Dalton, R. Providing Built Environment Students with the Necessary Skills for Employment: Finding the Required Soft Skills. Curr. Urban Stud. 2016, 4, 97–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Souto-Otero, M.; Białowolski, P. Graduate employability in Europe: The role of human capital, institutional reputation and network ties in European graduate labour markets. J. Educ. Work 2021, 34, 611–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucharčíková, A.; Mičiak, M.; Bartošová, A.; Budzeľová, M.; Bugajová, S.; Maslíková, A.; Pisoňová, S. Human Capital Management and Industry 4.0. SHS Web Conf. 2021, 90, 01010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coşkun, S.; Kayıkcı, Y.; Gençay, E. Adapting Engineering Education to Industry 4.0 Vision. Technologies 2019, 7, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, F.J.; Connell, P.; Thomson, L.A.; Willison, D. Empowering students by enhancing their employability skills. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2019, 43, 692–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assante, D.; Caforio, A.; Flamini, M.; Romano, E. Smart Education in the context of Industry 4.0. In Proceedings of the IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON), Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 8–11 April 2019; pp. 1140–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández Sampieri, R.; Fernández Collado, C.; del Baptista Lucio, M.P. Metodología de la Investigación, 6th ed.; McGRAW-HILL: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Palella Stracuzzi, S.; Martins Pestana, F. Metodología de la Investigación Cuantitativa—Santa Palella, Feliberto Martins.pdf (3 ed.) FEDUPEL. 2012. Available online: https://metodologiaecs.wordpress.com/2015/09/06/metodologia-de-la-investigacion-cuantitativa-3ra-ed-2012-santa-palella-stracuzzi-y-feliberto-martins-pestana-2/ (accessed on 8 July 2024).

- Mayorga-Ponce, R.; Ita-León, R.; Martínez-Alamilla, A.; Salazar-Valdez, D. Cuadro comparativo Hipótesis de investigación/Hipótesis Nula. Educ. Salud—Boletín Científico Inst. Cienc. Salud Univ. Autónoma Estado Hidalgo 2020, 9, 76–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunus, M.M.; Ang, W.S.; Hashim, H. Factors affecting teaching english as a second language (TESL) postgraduate students’ behavioural intention for online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perreten, N.A.; Domínguez-Berjón, M.F.; Mochales, J.A.; Esteban-Vasallo, M.D.; Ancos, L.M.B.; Pérez, M.Á.L. Tasas de respuesta a tres estudios de opinión realizados mediante cuestionarios en línea en el ámbito sanitario. Gac. Sanit. 2012, 26, 477–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fincham, J.E. Response rates and responsiveness for surveys, standards, and the Journal. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2008, 72, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seniuk Ciceka, J.; Peto, L.; Ingram, S. Linking the CEAB Graduate Attribute Competencies To Employability Skills 2000+: Equipping Students with The Language And Tools For Career/Employment Success. In Proceedings of the Actas de La Asociación Canadiense de Educación En Ingeniería (CEEA), Halifax, NS, Canada, 19–22 June 2016; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andino-González, P.; Vega-Muñoz, A.; Salazar-Sepúlveda, G. How to Measure Management Skills: Systematic Review. Preprints 2024, 2024012044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schermelleh-Engel, K.; Moosbrugger, H.; Müller, H. Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: Tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. MPR-Online 2003, 8, 23–74. Available online: https://www.stats.ox.ac.uk/~snijders/mpr_Schermelleh.pdf (accessed on 8 July 2024).

- Kalkan, Ö.K.; Kelecioğlu, H. The effect of sample size on parametric and nonparametric factor analytical methods. Kuram Ve Uygulamada Egit. Bilim. 2016, 16, 153–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ventura-León, J.; Mamani-Benito, O. Diseño y validación de una rúbrica analítica para evaluar manuscritos científicos. Rev. Habanera De Cienc. Méd. 2022, 21, 1–8. Available online: https://revhabanera.sld.cu/index.php/rhab/article/view/4752 (accessed on 8 July 2024).

- Ferrando, P.J.; Lorenzo-Seva, U. Program FACTOR at 10: Origins, development and future directions. Psicothema 2017, 29, 236–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harman, H. Modern Factor Analysis, 3rd ed.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley, T.L. Essential Traits of Mental Life; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1935. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-Seva, U.; Timmerman, M.E.; Kiers, H.A.L. The hull method for selecting the number of common factors. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2011, 46, 340–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freiberg Hoffmann, A.; Stover, J.B.; De la Iglesia, G.; Fernández Liporace, M. Correlaciones Policóricas Y Tetracóricas En Estudios Factoriales Exploratorios Y Confirmatorios. Cienc. Psicológicas 2013, 21, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M. Factor simplicity index and transformations. Psychometrika 1977, 42, 277–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo-Seva, U. A factor simplicity index. Psychometrika 2003, 68, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Véliz Capuñay, C. Análisis Multivariante; Aires, C.L.B., Ed.; Biblioteca Hernán Malo González: Cuenca, Ecuador, 2016; Available online: https://biblioteca.uazuay.edu.ec/buscar/item/83075 (accessed on 8 July 2024).

- Romero Suárez, N. Estadística en la Toma de Decisiones: El p-valor. Telos 2012, 14, 439–446. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/993/99324907004.pdf (accessed on 8 July 2024).

- Molina-Arias, M. Lectura crítica en pequeñas dosis. Pediatría Atención Primaria 2017, 19, 377–381. Available online: https://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?pid=S1139-76322017000500014&script=sci_arttext&tlng=pt (accessed on 8 July 2024).

- Lorenzo-Seva, U.; Ferrando, P.J. Supplementary materials to: A simulation-based scaled test statistic for assessing model-data fit in least-squares unrestricted factor-analysis solutions. Methodology 2023, 19, 96–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, M.R.; Kitagawa, K.G. Understanding Employability Skills; Conference Board of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1999; pp. 1–29. Available online: https://www.uwinnipeg.ca/edpd/docs/Conference%20Board%20of%20Canada%20Understanding%20Employability%20Skills.pdf (accessed on 8 July 2024).

- Ogbonna, C.G. Synchronous versus asynchronous e-learning in teaching word processing: An experimental approach. South Afr. J. Educ. 2019, 39, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Paula, A. Adopting distributed pair Programming as an effective team learning activity: A systematic review. J. Comput. High. Educ. 2024, 36, 320–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parra-González, M.E.; Rodríguez-Sabiote, C.; Aguaded-Ramírez, E.M.; Cuevas-Rincón, J.M. Analysis of the variables that promote professional insertion based on critical thinking. Front. Educ. 2023, 8, 1160023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwan, M.; Ahmad, N.; Amiruddin, M.; Ismail, M.; Harun, H. Identifying the Employment Skills Among Malaysian Vocational Students: An Analysis of Gender Differences. J. Tech. Educ. Train. 2019, 11, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qostal, A.; Sellamy, K.; Sabri, Z.; Nouib, H.; Lakhrissi, Y.; Moumen, A. Perceived Employability of Moroccan Engineering Students: A PLS-SEM Approach. Int. J. Instr. 2024, 17, 259–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiraly, R.; Mahdaviazad, H.; Pakdin, A. Doctor patient communication skills: A survey on knowledge and practice of Iranian family physicians. BMC Fam. Pract. 2021, 22, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyki, M.; Singorahardjo, M.; Cotronei-Baird, V.S. Preparing graduates with the employability skills for the unknown future: Reflection on assessment practice during COVID-19. Account. Res. J. 2021, 34, 229–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Arias, J.M.; Rodríguez-Esteban, A. Competencias socioemocionales de los educadores sociales: La influencia del contexto laboral. Educar 2022, 58, 535–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, M.E.; Mosquera, P. Linking development of skills and perceptions of employability: The case of Erasmus students. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraživanja 2020, 33, 2769–2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macanović, N.; Petrović, J.; Dragojević, A. Professional Competence of Experts In Psychosocial Work. Int. Rev. 2022, 3, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basir, N.M.; Zubairi, Y.Z.; Jani, R.; Wahab, D.A. Soft Skills and Graduate Employability: Evidence from Malaysian Tracer Study. Pertanika J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2022, 30, 1975–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, W.F.W.; Salleh, K.M.; Sulaiman, N.L.; Kamarrudin, M. Employability Skills in the TVET Trainer Training Program: The perception Between Experienced Trainers and Novices Trainers. J. Tech. Educ. Train. 2022, 14, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Cespón, J.; Alonso-Rodríguez, J.A.; Rodríguez-Barcia, S.; Gallego, P.P.; Pino-Juste, M.R. Employability Skills of Biology Graduates through an Interdisciplinary Project-Based Service-Learning Experience with Engineering and Translation Undergraduate Students. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrantes, P.; Silva, A.P.; Backstrom, B.; Neves, C.; Falé, I.; Jacquinet, M.; Ramos, M.d.R.; Magano, O.; Henriques, S. Transversal Competences and Employability: The Impacts of Distance Learning University According to Graduates’ Follow-Up. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Fundamental Skills | Personal Management Skills | Teamwork Skills |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| Authors | Country | Sample | χ2/df | RMSEA | GFI | CFI | NNFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Idkhan et al. [33] | Indonesia | 528 | 0.943 ** | 0.006 ** | 0.912 * | 0.974 ** | 0.972 ** |

| Variable | Category | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 121 | 53.8 |

| Female | 104 | 46.2 | |

| Total | 225 | 100 | |

| Work Experience | Less than 1 year | 37 | 16.4 |

| Between 1 and 10 years | 101 | 44.9 | |

| More than 10 years | 87 | 38.7 | |

| Total | 225 | 100 | |

| Employment Status | No Employability | 84 | 37.3 |

| Employability | 141 | 62.7 | |

| Total | 225 | 100 |

| Models | Country | Sample | χ2/df | RMSEA | GFI | CFI | NNFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Idkhan et al. [33] | Indonesia | 528 | 0.943 | 0.006 | 0.912 | 0.974 | 0.972 |

| Proposed Model | Honduras | 225 | 1.226 1 | 0.032 | 0.993 | 0.986 | 0.997 |

| Variable | F1 | F2 | F3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| V30 | 0.661 | ||

| V32 | 0.593 | ||

| V33 | 0.567 | ||

| V34 | 0.869 | ||

| V37 | 0.798 | ||

| V38 | 0.438 | ||

| V5 | 0.854 | ||

| V7 | 0.714 | ||

| V10 | 0.871 | ||

| V13 | 0.681 | ||

| V16 | 0.533 | ||

| V21 | 0.481 | ||

| V29 | 0.637 | ||

| V41 | 0.778 | ||

| V23 | 0.466 | ||

| V25 | 0.860 | ||

| V26 | 0.571 | ||

| V44 | 0.581 | ||

| V45 | 0.687 | ||

| V46 | 0.616 | ||

| V49 | 0.568 | ||

| Eigenvalue | 12.182 | 1.533 | 1.226 |

| Proportion of variance | 58.01% | 7.30% | 5.84% |

| Fraction of 71.15%. | 81.53% | 10.26% | 8.21% |

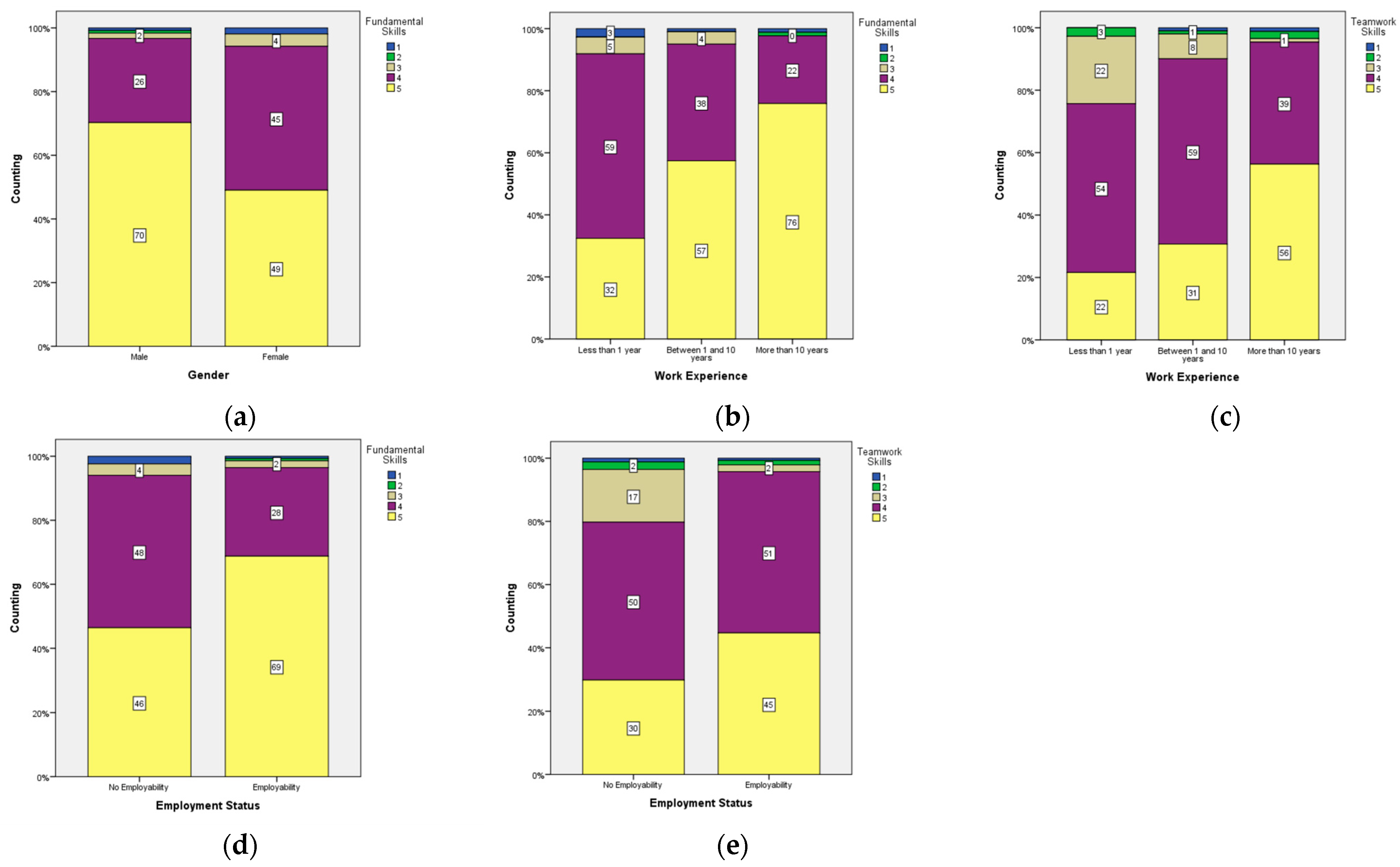

| Demographic Variables (dvj) | Parameters | F1: Personal Management Skills | F2: Fundamental Skills | F3: Teamwork Skills | FT: Employability Skills |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Value | 5.307 | 12.133 | 8.224 | 5.307 |

| Asymptotic significance (bilateral) | 0.257 | 0.016 * | 0.084 | 0.257 | |

| Work Experience | Value | 5.050 | 25.383 | 30.727 | 5.050 |

| Asymptotic significance (bilateral) | 0.752 | 0.001 ** | 0.000 ** | 0.752 | |

| Employment Status | Value | 0.902 | 12.440 | 18.146 | 0.902 |

| Asymptotic significance (bilateral) | 0.924 | 0.014 * | 0.001 ** | 0.924 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Andino-González, P.; Vega-Muñoz, A.; Salazar-Sepúlveda, G. Analyzing Managerial Skills for Employability in Graduate Students in Economics, Administration and Accounting Sciences. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6725. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16166725

Andino-González P, Vega-Muñoz A, Salazar-Sepúlveda G. Analyzing Managerial Skills for Employability in Graduate Students in Economics, Administration and Accounting Sciences. Sustainability. 2024; 16(16):6725. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16166725

Chicago/Turabian StyleAndino-González, Patricia, Alejandro Vega-Muñoz, and Guido Salazar-Sepúlveda. 2024. "Analyzing Managerial Skills for Employability in Graduate Students in Economics, Administration and Accounting Sciences" Sustainability 16, no. 16: 6725. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16166725

APA StyleAndino-González, P., Vega-Muñoz, A., & Salazar-Sepúlveda, G. (2024). Analyzing Managerial Skills for Employability in Graduate Students in Economics, Administration and Accounting Sciences. Sustainability, 16(16), 6725. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16166725