Empowering Innovation: Advancing Social Entrepreneurship Policies in Croatia

Abstract

1. Introduction

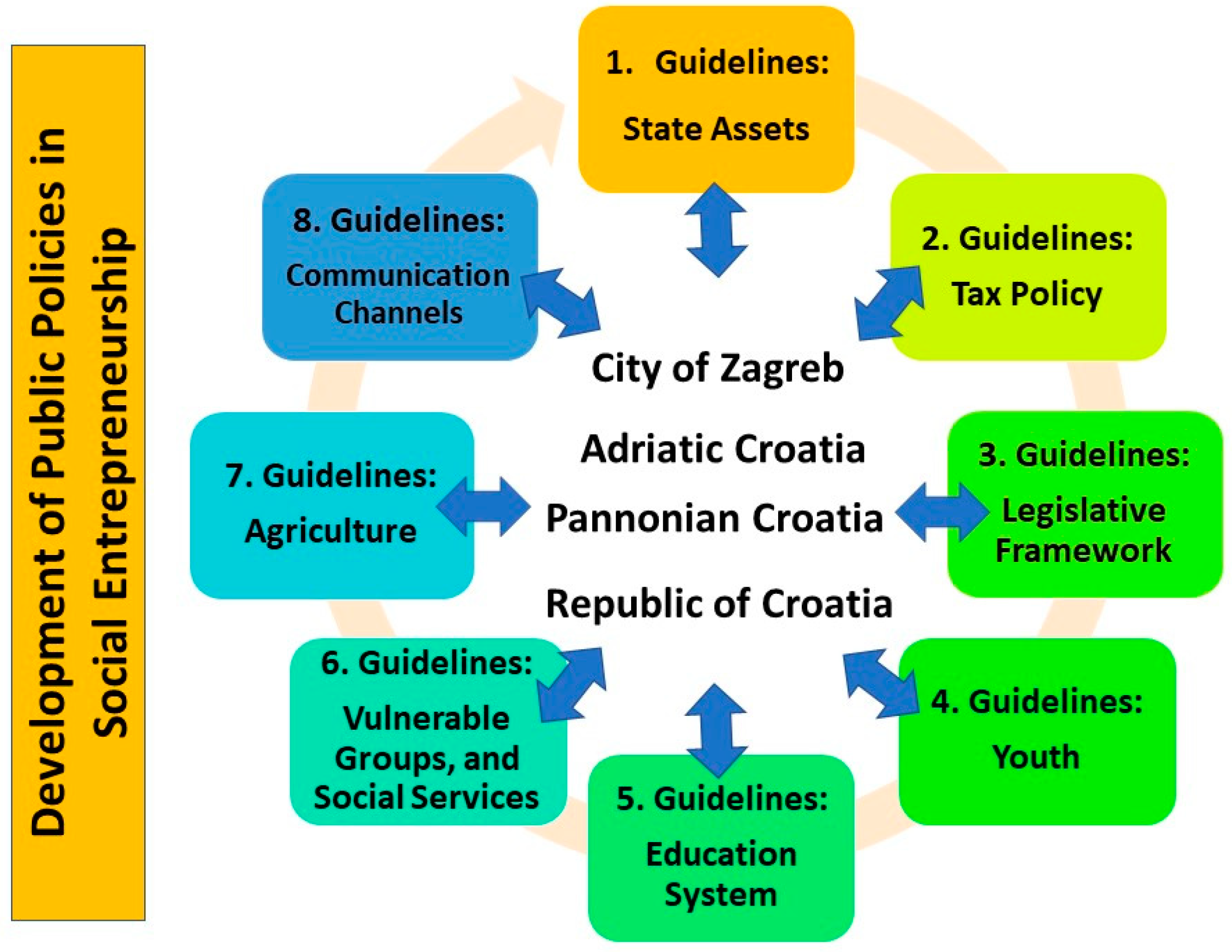

1.1. Background and Context

1.2. Research Purpose and Objectives

- To assess regional variations in the effectiveness of public policy guidelines on social entrepreneurship across Croatia;

- To evaluate how support levels for social entrepreneurship policies vary among different policy areas;

- To analyze the consistency of support levels across regions for different social entrepreneurship policy areas.

- What is the level of support for various guidelines aimed at fostering social entrepreneurship in Croatia, and how does it vary across different regions and stakeholder groups?

- How do different stakeholder groups perceive and prioritize the guidelines related to social entrepreneurship in Croatia?

- What are the key challenges and opportunities identified by stakeholders in implementing social entrepreneurship policies?

- To what extent are existing policies effective in promoting social entrepreneurship and addressing societal needs in Croatia?

- How do variations in policy support levels across regions and stakeholder groups impact the growth and sustainability of social enterprises in Croatia?

- What insights and recommendations can be drawn from the analysis to enhance the effectiveness of social entrepreneurship policies in Croatia?

- Regional Differences: There are significant regional differences in the perceptions of the effectiveness of public policy guidelines on social entrepreneurship.Regional disparities in economic development, social structures, and cultural contexts are common in many countries, including Croatia. These disparities can significantly influence how policies are perceived and implemented. Croatia, like many countries, has distinct regions (in this case, the City of Zagreb, Adriatic Croatia, and Pannonian Croatia) with varying economic conditions, historical contexts, and social needs. Understanding regional differences is crucial for crafting effective policies. What works in one region may not be as effective in another due to varying economic conditions, social structures, or cultural norms. If significant regional differences exist, it may justify allocating resources differently across regions to support social entrepreneurship more effectively. Recognizing regional differences allows policymakers to develop more targeted and contextually appropriate strategies for promoting social entrepreneurship. Addressing regional disparities in policy effectiveness can contribute to more balanced development across the country, potentially reducing economic and social inequalities.

- Impact of Policy Area on Support: The level of support for social entrepreneurship policies varies significantly depending on the policy area.Social entrepreneurship intersects with various policy domains, including education, taxation, agriculture, and social services. Each of these areas has its own stakeholders, existing policy frameworks, and perceived importance in the broader social and economic context. The literature on social entrepreneurship often emphasizes the need for supportive ecosystems that span multiple policy areas. Understanding which policy areas receive more support can help in prioritizing efforts and resources in developing social entrepreneurship policies. If support varies significantly across policy areas, it highlights the need for an interdisciplinary approach to social entrepreneurship policy. Knowing which policy areas have more or less support can guide strategies for stakeholder engagement and coalition-building. Areas with lower support might indicate knowledge gaps or areas where the relevance of social entrepreneurship is not well understood, suggesting a need for education or awareness campaigns.

- Regional Variability in Policy Support Consistency: There is a significant difference in the consistency of support levels across regions for different policy areas.This hypothesis combines elements of regional development theory with the multi-faceted nature of social entrepreneurship policy. It recognizes that not only might overall support for social entrepreneurship vary by region, but the consistency of that support across different policy areas might also vary. This can be influenced by factors such as regional economic specializations, social needs, or existing policy frameworks. Understanding how consistently different policy areas are supported across regions can help in developing more coherent national strategies that accommodate regional variations. Areas with high and consistent support across regions might indicate successful policy approaches that could be replicated. Inconsistent support across regions for certain policy areas might point to region-specific challenges or opportunities that need to be addressed. Analyzing consistency can facilitate cross-regional learning, where successful approaches in one region could be adapted for others. Understanding which policy areas have consistent support across regions versus those with high variability can inform more effective resource allocation and policy implementation strategies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Data Collection

Survey Instrument

2.3. Data Analysis

2.3.1. Quantitative Analysis

- Descriptive Statistics:

- t-tests:

- Differences in support levels between specific regions (part of Hypothesis 1).

- Differences in support levels between specific policy areas (part of Hypothesis 2).

- , : Means of the two groups

- , : Variances of the two groups

- n1, n2: Sample sizes of the two groups

- One-way ANOVA was employed to analyze the following:

- Differences in support levels across the three regions: the City of Zagreb, Adriatic Croatia, and Pannonian Croatia (Hypothesis 1).

- Differences in support levels across all policy areas (Hypothesis 2).

- Differences in the consistency of support levels across regions for different policy areas (Hypothesis 3).

- Yij: The jth observation in the ith group,

- μ: The overall mean,

- αi: The effect of the ith group,

- εij: The random error term.

2.3.2. Qualitative Analysis

- Contextual Interpretation: Researchers interpreted quantitative findings within broader contexts, considering socio-economic factors, cultural norms, and historical backgrounds to provide a nuanced understanding of the results.

- Exploring Subgroup Differences: Analysis uncovered subgroup variations within the quantitative data, revealing unique perspectives or experiences across demographic variables or stakeholder groups.

- Interpretation of Quantitative Patterns: When quantitative analysis indicated regional discrepancies in guideline support, qualitative analysis explored contextual factors or stakeholder perceptions contributing to these variations.

2.4. Reliability and Validity

2.4.1. Reliability

2.4.2. Validity

2.5. Limitations

3. Results

3.1. Regional Differences in Perceptions of Public Policy Guidelines on Social Entrepreneurship in Croatia

- Null Hypothesis (H0): There are no significant regional differences in perceptions of the effectiveness of public policy guidelines;

- Alternative Hypothesis (H1): There are significant regional differences in perceptions of the effectiveness of public policy guidelines.

- F-statistic: 4.651683267185842,

- p-value: 0.011652764386575222.

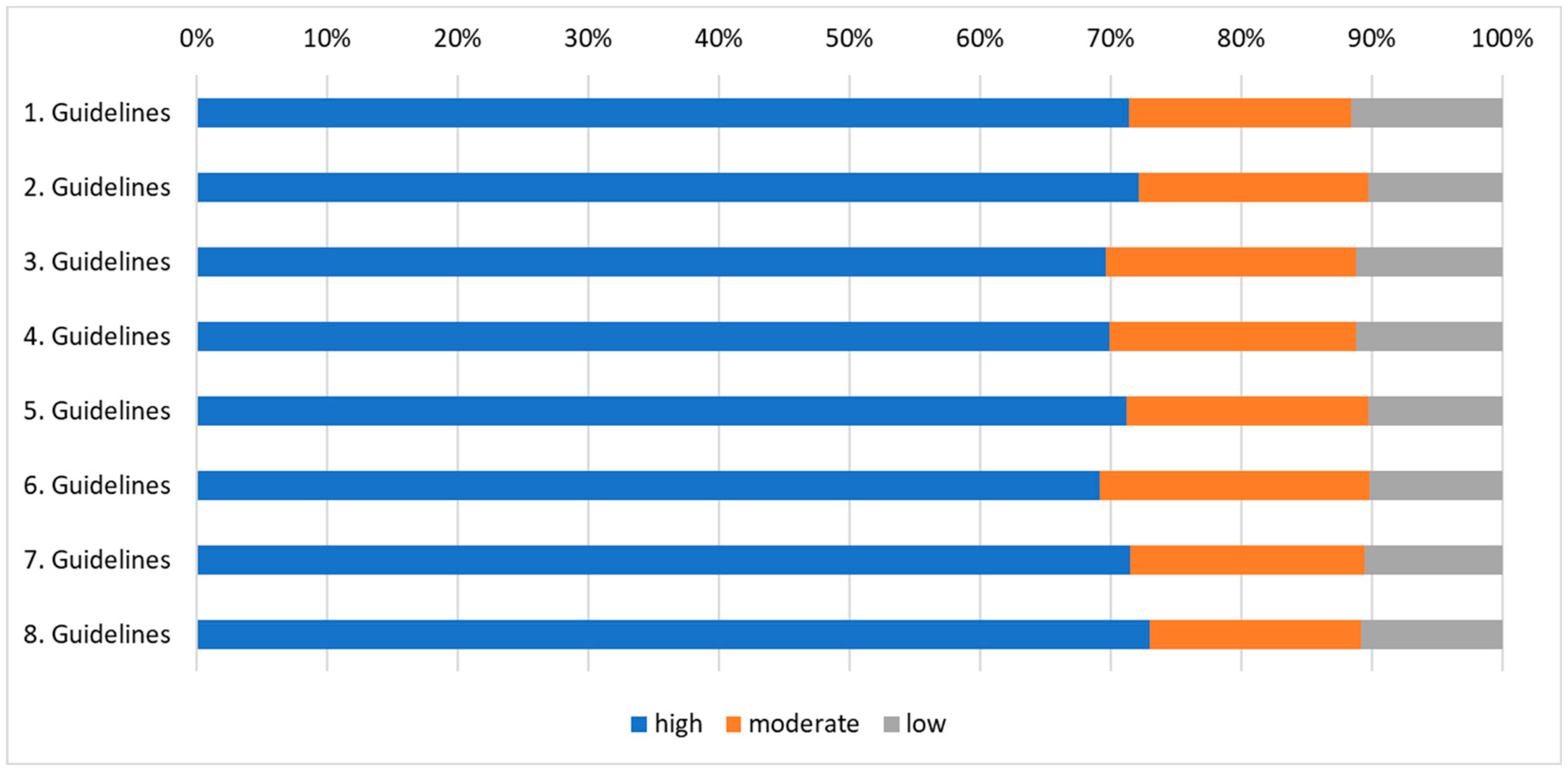

3.2. Impact of Policy Area on Support of Public Policy Guidelines on Social Entrepreneurship in Croatia

- Null Hypothesis (H0): The level of support for social entrepreneurship policies does not vary significantly by policy area;

- Alternative Hypothesis (H1): The level of support for social entrepreneurship policies varies significantly by policy area.

- F-statistic: 1.5157298037594724,

- p-value: 0.16736707670946472.

3.3. Consistency of Support across Regions for Different Public Policy Guidelines on Social Entrepreneurship in Croatia

- Null Hypothesis (H0): There is no significant difference in the consistency of support levels across regions for different policy areas when considering mean support levels;

- Alternative Hypothesis (H1): There is a significant difference in the consistency of support levels across regions for different policy areas.

- State Assets: 7.8410,

- Tax Policy: 18.9004,

- Legislative Framework: 13.1246,

- Youth: 25.2454,

- Education System: 119.6052,

- Vulnerable Groups: 42.9820,

- Agriculture: 16.9657,

- Communication: 23.6459.

3.4. Regional Variations and Policy Implications for Social Entrepreneurship in Croatia

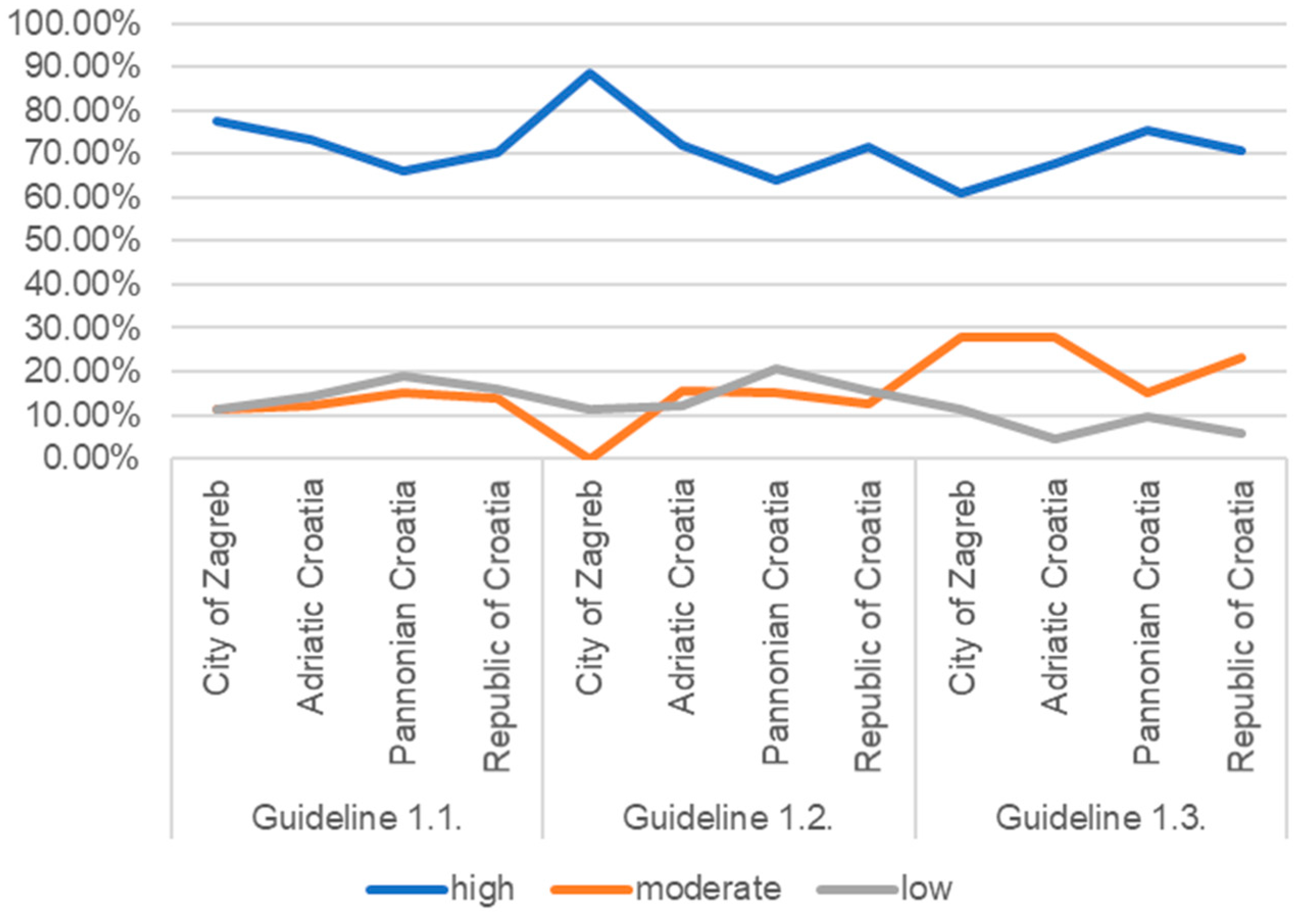

3.4.1. The Development of Public Policies in Social Entrepreneurship and State Assets

- Coordination Working Group (Guideline 1.1): Establishing a coordinated working group composed of stakeholders is viewed positively, but with regional variations. Higher support in certain regions indicates recognition of the importance of collaboration and coordination in promoting social entrepreneurship and managing state assets. However, the moderate to low levels of support in some areas suggest potential challenges in ensuring effective stakeholder engagement and cooperation.The descriptive statistics (frequency distribution analysis) for this guideline are as follows:

- City of Zagreb: High impact (77.78%), moderate (11.11%), low (11.11%);

- Adriatic Croatia: High impact (73.33%), moderate (12.22%), low (14.44%);

- Pannonian Croatia: High impact (66.04%), moderate (15.09%), low (18.87%).

- Education of Stakeholders (Guideline 1.2): Education is seen as highly impactful, especially in certain regions. Higher support in some regions may indicate greater awareness of the potential benefits of education and training in fostering innovation and project development.The descriptive statistics for this guideline are as follows:

- City of Zagreb: High impact (88.89%), no moderate impact, low impact (11.11%);

- Adriatic Croatia: High impact (72.22%), no moderate impact, low impact (12.22%);

- Pannonian Croatia: High impact (64.15%), no moderate impact, low impact (20.75%).

- Raising Public Awareness (Guideline 1.3): Public awareness efforts are crucial, but vary in perceived impact across regions. Higher support in some regions may indicate greater recognition of the importance of public awareness initiatives for promoting social entrepreneurship.The descriptive statistics for this guideline are:

- City of Zagreb: High impact (61.11%), moderate impact (27.78%), low impact (11.11%);

- Adriatic Croatia: High impact (67.78%), moderate impact (27.78%), low impact (4.44%);

- Pannonian Croatia: High impact (75.47%), moderate impact (15.09%), low impact (9.43%).

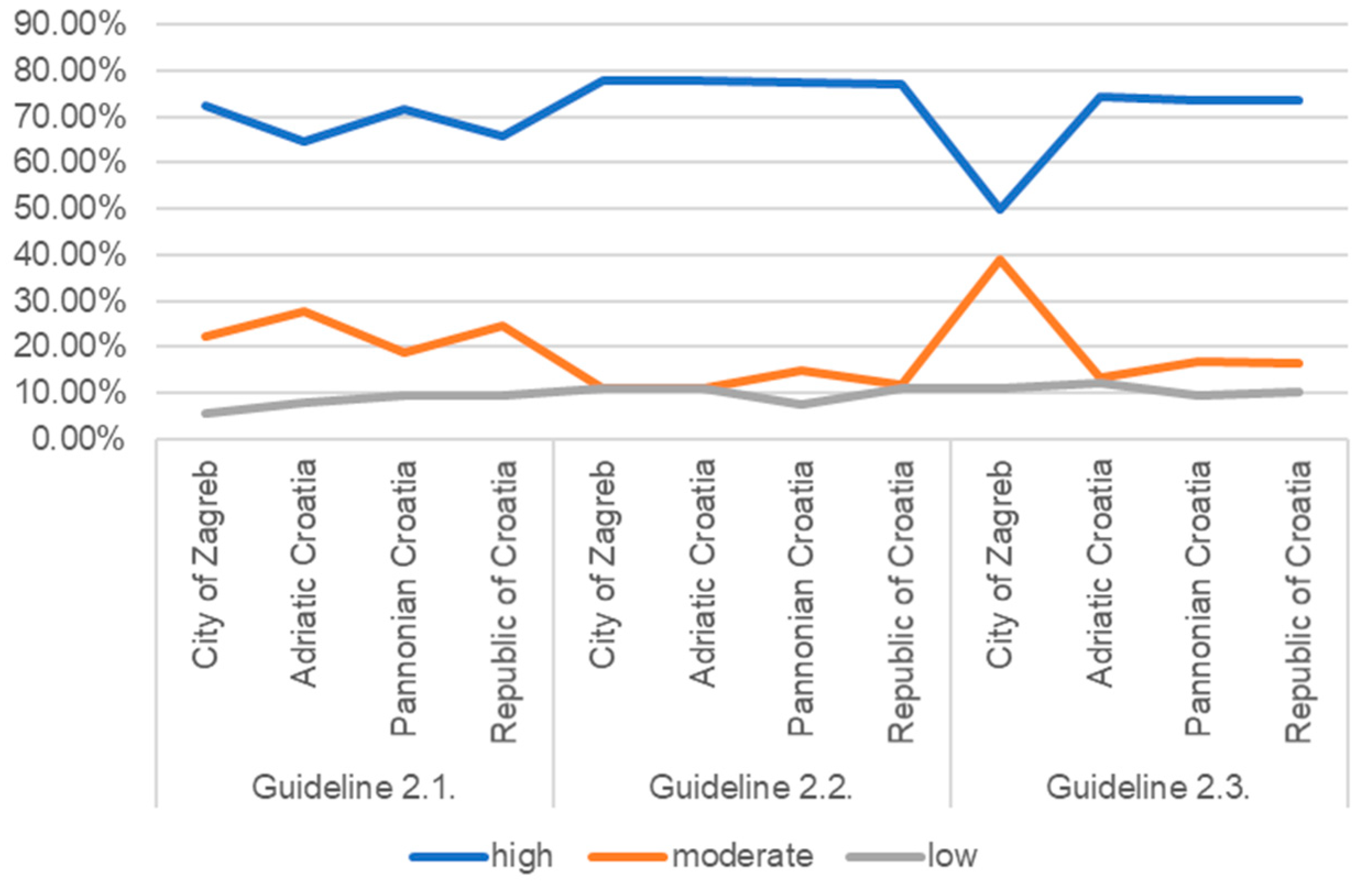

3.4.2. The Development of Public Policies in Social Entrepreneurship and Tax Policy

- Specific Tax Reliefs and Exemptions for Social Entrepreneurs (Guideline 2.1): The relatively high levels of support across regions indicate recognition of the significance of tax incentives in fostering a conducive environment for social entrepreneurship.The City of Zagreb and Pannonian Croatia show higher support, possibly reflecting greater awareness of the potential benefits of tax reliefs and exemptions for social entrepreneurs in urban and rural settings. In contrast, Adriatic Croatia exhibits slightly lower but still moderate support, which may be attributed to differing economic structures and priorities in coastal regions.The data suggest that there is a consensus on the importance of further elaborating specific tax measures to support social entrepreneurship, indicating an opportunity for policymakers to prioritize this area in policy formulation.

- Strengthening Specific Tax Reliefs and Exemptions (Guideline 2.2): The high levels of support across regions demonstrate a clear acknowledgment of the role of tax policies in incentivizing social entrepreneurship. Consistency in support levels across regions suggests a shared understanding of the importance of maintaining and potentially expanding existing tax incentives for social entrepreneurs.The data indicate that there is a strong consensus on the need to further elaborate and strengthen specific tax reliefs and exemptions for social entrepreneurs, highlighting a potential area for policy refinement and enhancement.

- Strengthening Capacity to Raise Financial Resources (Guideline 2.3): The varying levels of support across regions suggest differences in perceptions regarding the effectiveness of policies aimed at strengthening the capacity of social entrepreneurs to raise financial resources. While the City of Zagreb exhibits relatively lower support (50%), the Adriatic and the Pannonian Croatia show higher levels of endorsement, possibly reflecting regional differences in access to financial markets and funding opportunities.

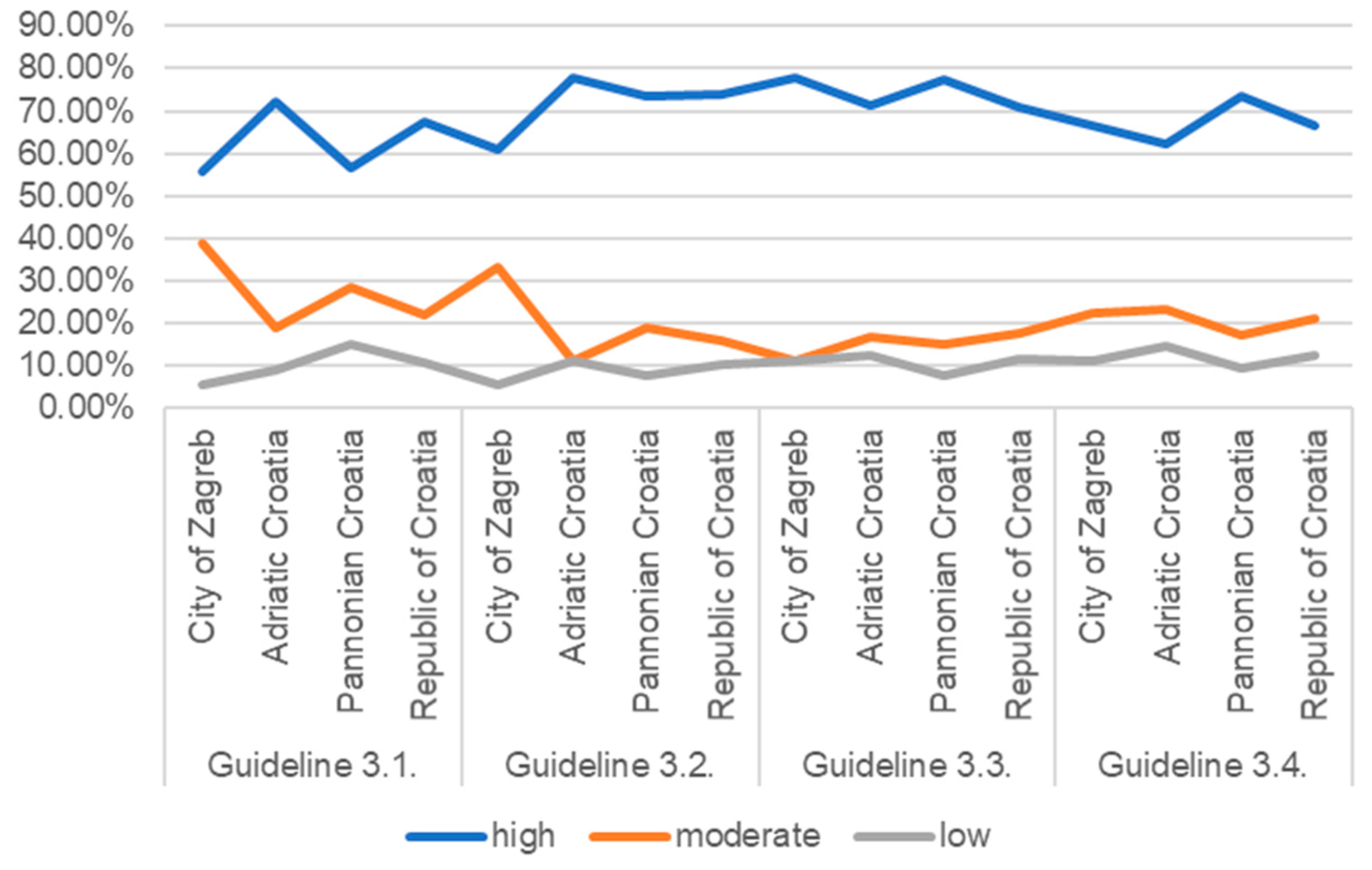

3.4.3. The Development of Public Policies in Social Entrepreneurship and Legislative Frameworks

- Mapping and Analysis of Social Enterprises, and Development of an Official Registry (Guideline 3.1):The varying levels of support across regions suggest differing perceptions regarding the importance and feasibility of mapping and analyzing social enterprises and establishing an official registry.While support is generally high, there are notable disparities, with higher levels of endorsement in Adriatic Croatia compared to Pannonian Croatia, for instance.To address these disparities and enhance effectiveness, policymakers could explore the underlying reasons for differing levels of support and tailor strategies to overcome barriers to implementation. This could involve capacity-building initiatives, stakeholder consultations, and targeted investments in data collection and analysis infrastructure.

- Creation of a Stimulating Legal Act Defining Social Enterprises (Guideline 3.2):The high levels of support across regions suggest a consensus on the importance of creating a legal framework that defines social enterprises and provides recommendations for amending the legislative framework.Notably, Adriatic Croatia exhibits particularly strong support for this guideline compared to other regions.To capitalize on this consensus and enhance effectiveness, policymakers should prioritize the development and implementation of a comprehensive legal act that provides clarity and incentives for social entrepreneurship. This could involve collaborating with stakeholders to identify key priorities and drafting legislation that addresses the specific needs and challenges of social enterprises.

- Establishment of a Unified Coordination Body for Social Entrepreneurship (Guideline 3.3):The data indicate relatively high levels of support across regions for the establishment of a unified body for coordinating and developing social entrepreneurship.While there are slight variations in support levels, particularly in Adriatic Croatia and the Republic of Croatia, overall, there is a recognition of the importance of coordination in advancing social entrepreneurship initiatives.To leverage this support and enhance effectiveness, policymakers could focus on establishing clear governance structures, defining the roles and responsibilities of the coordination body, and ensuring representation from diverse stakeholders. This could facilitate cohesive and collaborative efforts in promoting social entrepreneurship across different sectors and regions.

- Raising Public Awareness about Social Entrepreneurship (Guideline 3.4):The data indicate moderate to high levels of support for raising public awareness about the importance and role of social entrepreneurship.To maximize the impact of awareness-raising efforts, policymakers could develop targeted communication strategies that resonate with local communities and address region-specific concerns. This could involve leveraging diverse communication channels, collaborating with local influencers and media outlets, and integrating storytelling and testimonials to illustrate the tangible benefits of social entrepreneurship.

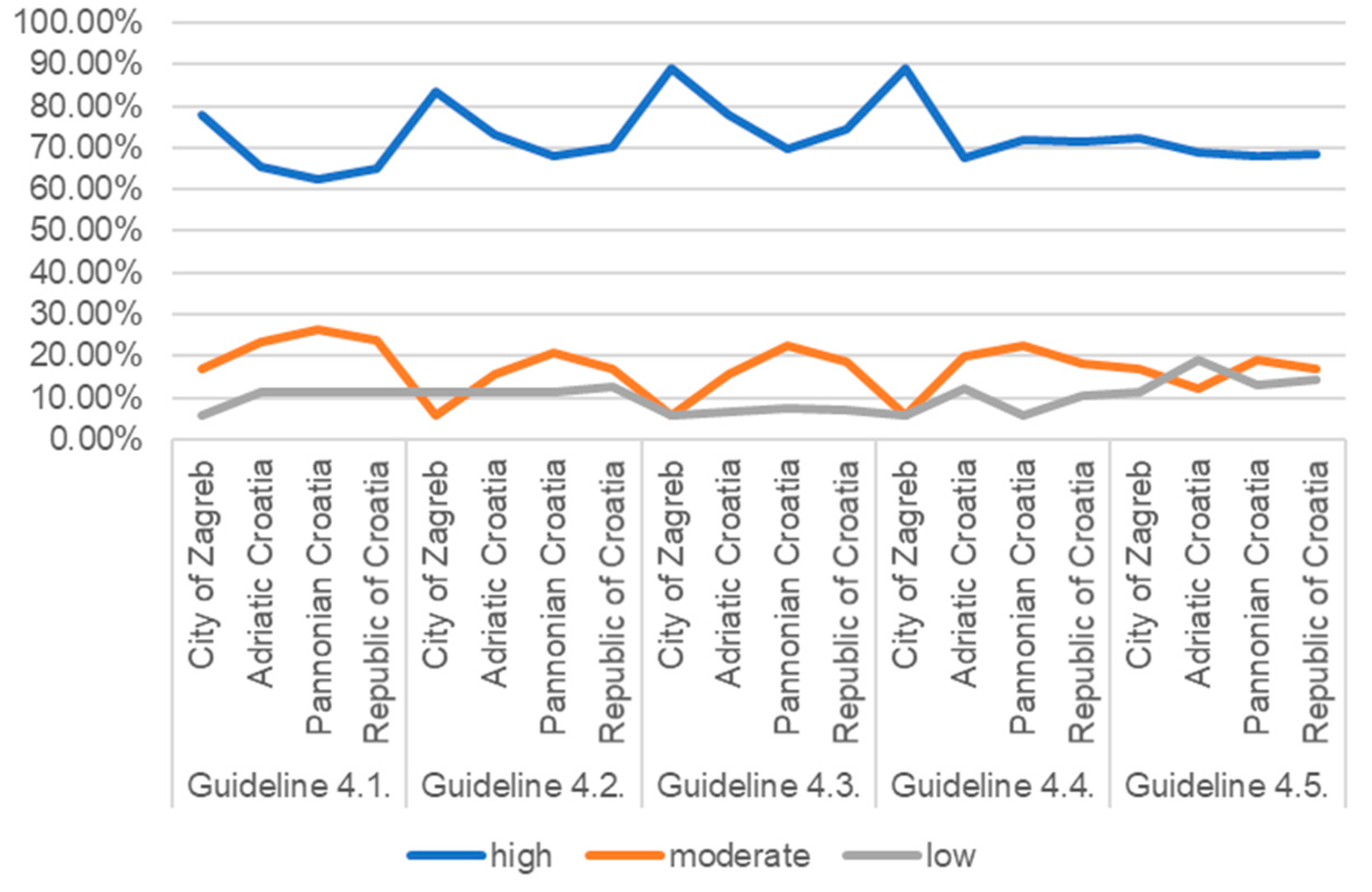

3.4.4. The Development of Public Policies in Social Entrepreneurship and Youth

- Mapping of Social Enterprises (Guideline 4.1):The data indicate varying levels of support for mapping social enterprises across regions.While the City of Zagreb shows the highest support, other regions exhibit moderate to high levels of endorsement.To enhance effectiveness, policymakers could prioritize investment in comprehensive mapping initiatives, ensuring accurate and up-to-date information to inform policy-making and resource allocation.

- Clear Strategic Framework for Youth Employment and Social Entrepreneurship (Guideline 4.2):The high levels of support across regions indicate a consensus on the importance of establishing a clear strategic framework to encourage youth employment and social entrepreneurship.To maximize impact, policymakers should focus on developing comprehensive strategies that address the unique needs and aspirations of young people, integrating elements of education, skills development, mentorship, and access to finance.

- Promotion and Visibility of Social Entrepreneurship Concept (Guideline 4.3):The data show strong support for promoting and enhancing the visibility of social entrepreneurship among entrepreneurs and citizens across regions.To capitalize on this support, policymakers could leverage communication strategies, public campaigns, and educational initiatives to raise awareness about the benefits and opportunities of social entrepreneurship, fostering a culture of innovation and social impact.

- Reform of Active Labor Market Policies (Guideline 4.4):The data indicate relatively high levels of support for reforming active labor market policies, including the Croatian Employment Service, across regions.To ensure effectiveness, policymakers should prioritize evidence-based reforms that enhance the responsiveness, efficiency, and inclusivity of labor market policies, aligning them with the evolving needs of the workforce and the changing nature of work.

- Reform of the Educational System (Guideline 4.5):The data highlight moderate to high levels of support for reforming the educational system to better prepare young people for entrepreneurship and employment opportunities. To drive meaningful change, policymakers should prioritize reforms that foster entrepreneurship education, practical skills development, and experiential learning opportunities within the formal education system, equipping students with the tools and mindset needed for success in the 21st-century economy [35].

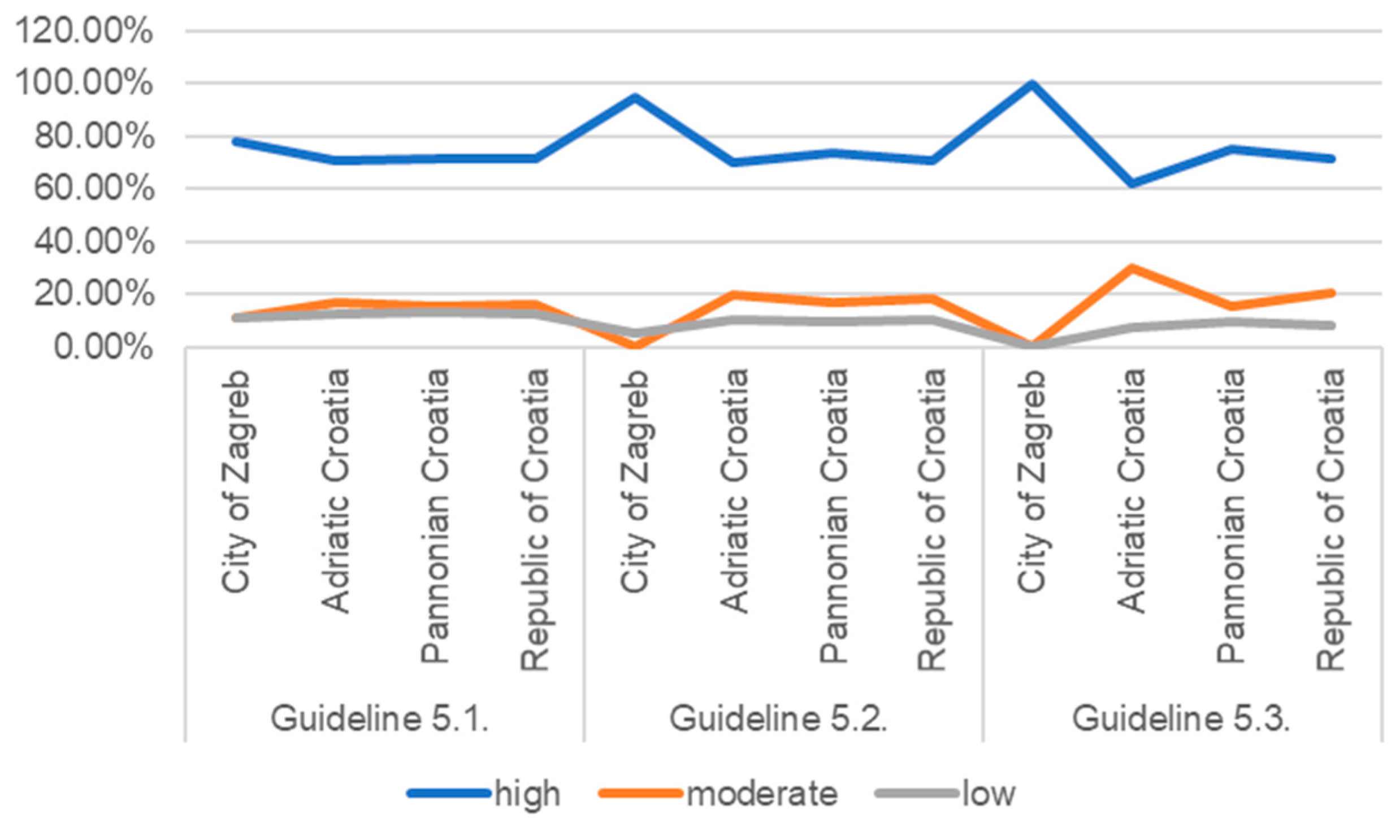

3.4.5. The Development of Public Policies in Social Entrepreneurship and the Education System

- Greater Visibility and Promotion of Service-Learning (Guideline 5.1):The data indicate moderate to high levels of support for the necessity of greater visibility and promotion of service-learning across regions.While the City of Zagreb exhibits the highest support, other regions also show notable endorsement, highlighting the perceived importance of integrating service-learning into educational curricula.To enhance effectiveness, policymakers could prioritize initiatives that promote experiential learning opportunities, community engagement, and social impact projects within schools and universities, fostering a culture of civic responsibility and active citizenship among students.

- Encouraging the Educational Community in Social Engagement (Guideline 5.2):The data show strong support for encouraging the educational community in social engagement, with the City of Zagreb demonstrating particularly high levels of endorsement.Other regions also exhibit moderate to high levels of support, indicating a recognition of the role of educational institutions in promoting social entrepreneurship and community development.To leverage this support, policymakers could implement incentives, recognition programs, and capacity-building initiatives to empower educators and students to engage in social entrepreneurship and community service activities, fostering a culture of social innovation and collaboration within educational settings.

- Reform of the Educational System (Guideline 5.3):The data reveal widespread support for the reform of the educational system across regions, with the City of Zagreb showing unanimous endorsement.Other regions also demonstrate notable levels of support, underscoring the perceived importance of updating educational curricula and methodologies to better prepare students for the challenges and opportunities of the 21st century.To capitalize on this consensus, policymakers should prioritize evidence-based reforms that promote entrepreneurship education, critical thinking skills, digital literacy, and socio-emotional learning within the educational system. This could involve curriculum revisions, teacher training programs, and partnerships with industry and civil society to ensure relevance and responsiveness to evolving societal needs.

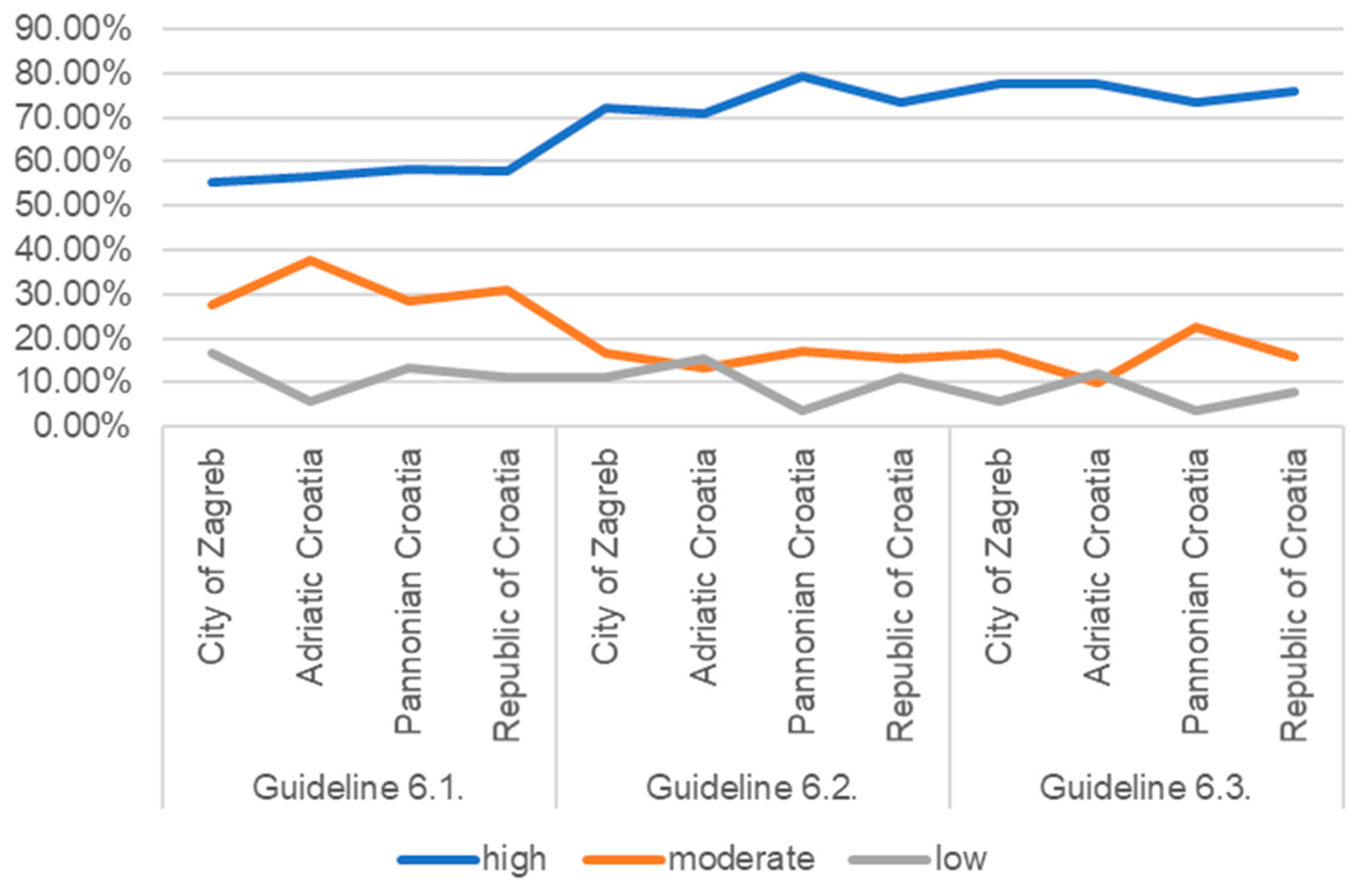

3.4.6. The Development of Public Policies in Social Entrepreneurship, Vulnerable Groups, and Social Services

- Ensuring Participatory Involvement of Citizens (Guideline 6.1):The data reveal moderate levels of support for ensuring participatory and systematic involvement of citizens in projects related to social entrepreneurship and vulnerable groups across regions.While support varies slightly between regions, there is a general recognition of the importance of citizen engagement in social initiatives.To enhance effectiveness, policymakers could prioritize mechanisms for meaningful citizen participation, such as community forums, stakeholder consultations, and participatory budgeting processes. This could foster ownership, accountability, and sustainability of social projects while addressing the diverse needs and perspectives of vulnerable groups.

- Adherence to Evaluation Guidelines of the Strategy for Social Entrepreneurship (Guideline 6.2):The data indicate moderate to high levels of support for acting in accordance with evaluation guidelines of the Strategy for Social Entrepreneurship in the segment of vulnerable groups and social services.There is a consensus on the importance of monitoring and evaluating social entrepreneurship initiatives to ensure their effectiveness and impact.To maximize the utility of evaluation guidelines, policymakers could invest in capacity-building for data collection and analysis, establish transparent reporting mechanisms, and use evaluation findings to inform evidence-based decision-making and policy adjustments.

- Direction of Local and Regional Governments Towards Supporting Social Associations (Guideline 6.3):The data show relatively high levels of support for directing local and regional self-government units towards raising awareness of social entrepreneurship and supporting social associations and cooperatives.This indicates a recognition of the role of local governance in fostering a conducive environment for social entrepreneurship and community development.To capitalize on this support, policymakers could provide targeted incentives, capacity-building support, and technical assistance to local governments to enhance their engagement with social associations and cooperatives. This could involve sharing best practices, facilitating networking opportunities, and streamlining administrative procedures to facilitate collaboration and resource mobilization.

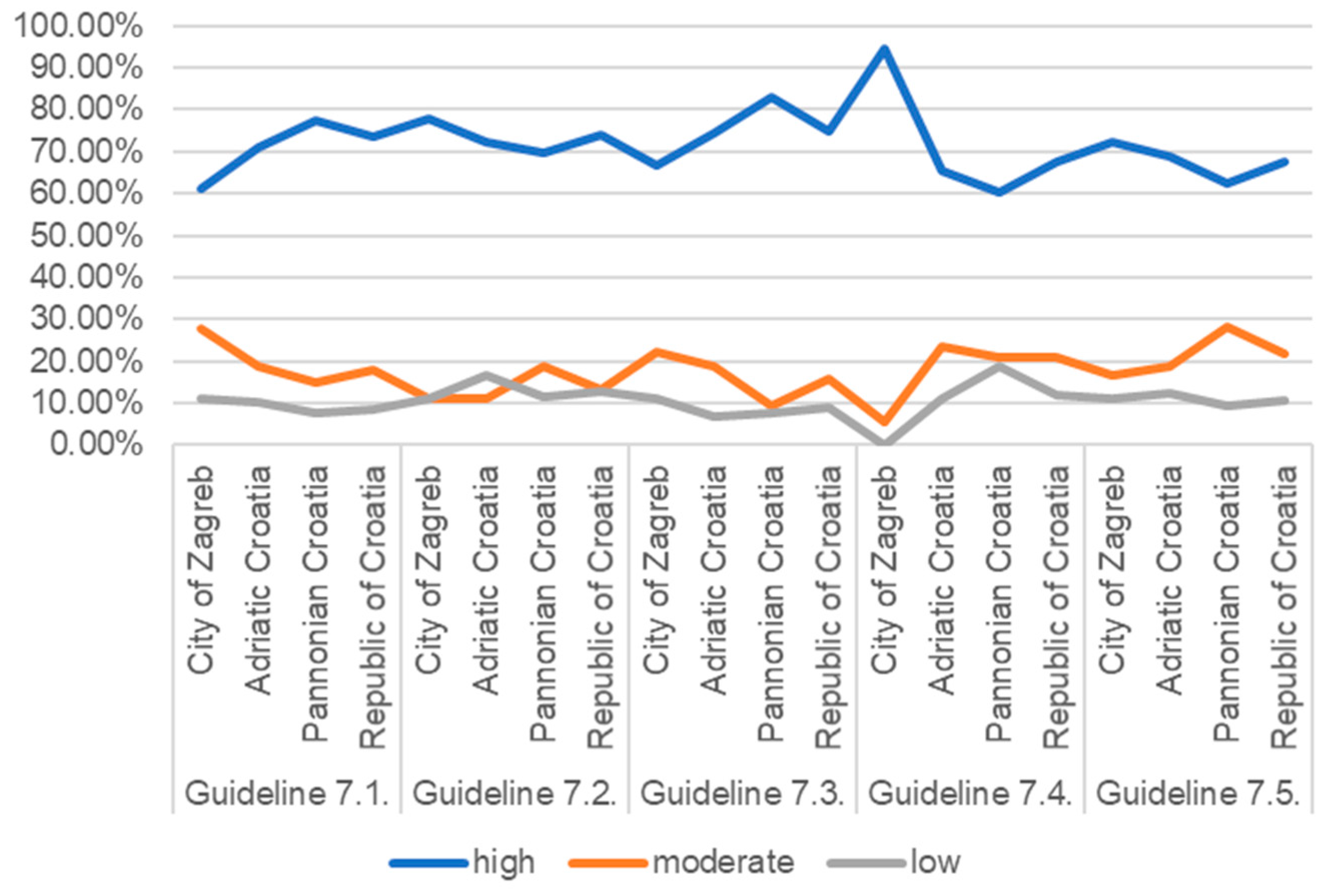

3.4.7. The Development of Public Policies in Social Entrepreneurship in Agriculture

- Complementarity of Measures for Social Entrepreneurship in Agriculture (Guideline 7.1):The data indicate moderate to high levels of support for ensuring complementarity of measures and initiatives linked to development policies relevant for social entrepreneurship in agriculture across regions.This suggests a recognition of the need for coordinated efforts and synergy between various policy measures to support social entrepreneurship in agriculture effectively.To enhance effectiveness, policymakers could prioritize collaboration and coordination among relevant stakeholders, aligning policies, programs, and resources to create a supportive ecosystem for social entrepreneurs in agriculture.

- Strengthening Agricultural Cooperatives (Guideline 7.2):The data reveal moderate to high levels of support for strengthening agricultural cooperatives, with the City of Zagreb and Pannonian Croatia showing particularly strong endorsement.This indicates recognition of the role of cooperatives in fostering collaboration, sharing resources, and empowering farmers, especially in regions with a strong agricultural base.To capitalize on this support, policymakers could invest in capacity-building programs, provide financial incentives, and facilitate networking opportunities to strengthen the resilience and sustainability of agricultural cooperatives.

- Enhancing Community-Led Local Development (CLLD) and Supporting Local Action Groups (LAGs) (Guideline 7.3):The data show moderate to high levels of support for enhancing CLLD and supporting LAGs with relevant results, with Pannonian Croatia demonstrating particularly strong endorsement.This suggests a recognition of the importance of bottom-up approaches and community engagement in driving local development initiatives.To leverage this support, policymakers could provide technical assistance, training, and funding opportunities to empower LAGs, enabling them to lead inclusive and participatory development processes that address the specific needs and priorities of rural communities.

- Strengthening Support for Social Entrepreneurship in Agriculture at All Governance Levels (Guideline 7.4):The data indicate high levels of support for strengthening support for social entrepreneurship in agriculture across all governance levels, with the City of Zagreb showing unanimous endorsement.This underscores the importance of multi-level governance frameworks and coordinated action to create an enabling environment for social entrepreneurship in agriculture.To translate this support into tangible outcomes, policymakers could implement targeted policies, allocate dedicated funding, and establish support mechanisms at the local, regional, and national levels to facilitate the growth and success of social enterprises in agriculture.

- Exploitation of Developmental Potential for Social Entrepreneurship in Agriculture (Guideline 7.5):The data reveal moderate to high levels of support for enhancing the exploitation of developmental potential for further development of social entrepreneurship in agriculture.This suggests a recognition of untapped opportunities and the need to leverage agricultural resources and innovation for social and economic development.To unlock this potential, policymakers could promote research and innovation, facilitate access to markets and finance, and provide targeted support for value-added agricultural activities and sustainable business models that benefit both farmers and local communities.

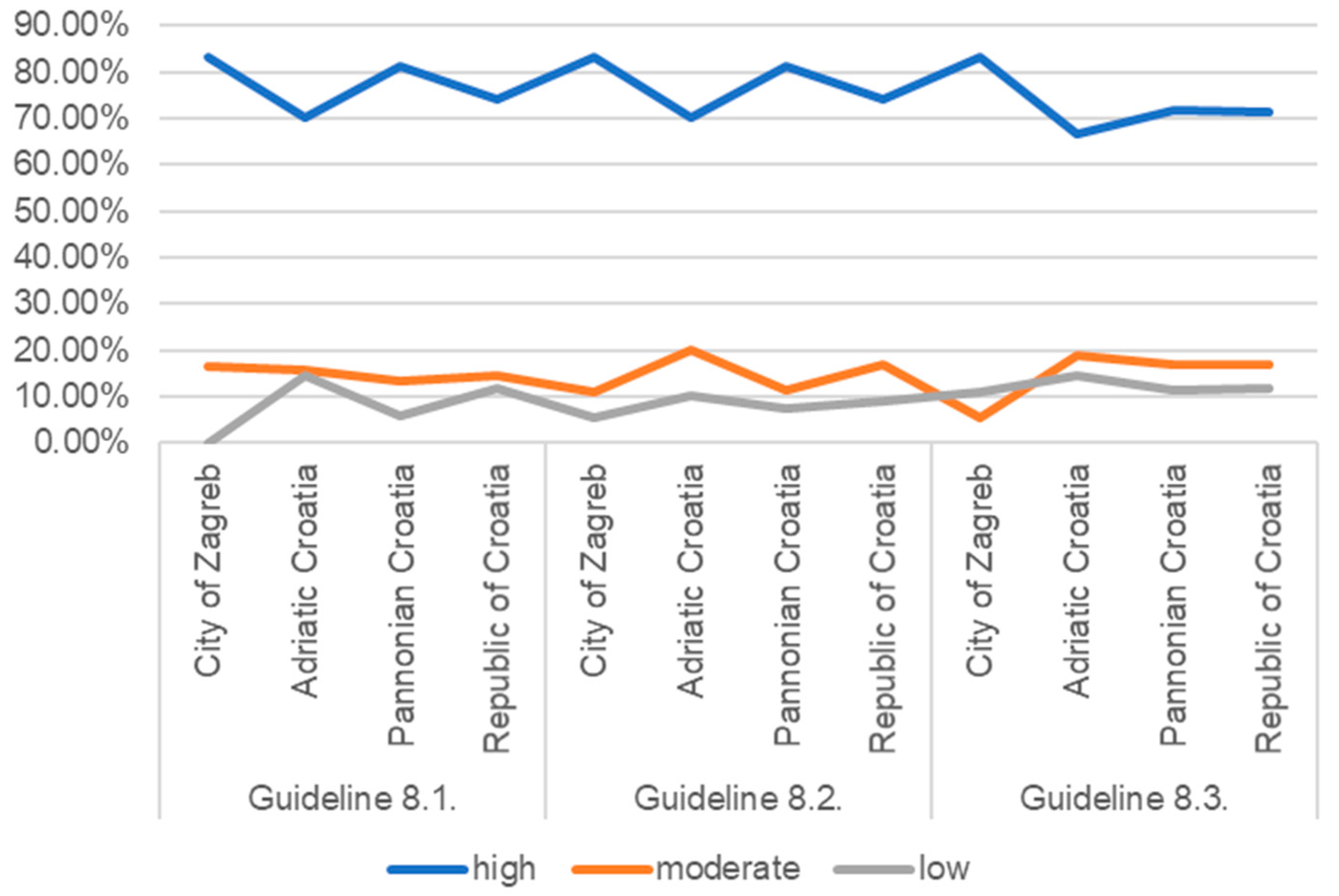

3.4.8. The Development of Public Policies in Communication Channels of Social Entrepreneurship and Public Policy Holders and Support Institutes

- Improving Management Quality for Communication Channels (Guideline 8.1):The data indicate high levels of support for improving management quality to strengthen communication channels across all regions, particularly in the City of Zagreb and Pannonian Croatia.This suggests a recognition of the importance of effective management in facilitating communication and collaboration between stakeholders in the social entrepreneurship ecosystem.To capitalize on this support, policymakers could prioritize capacity-building programs, provide training in communication and leadership skills, and establish clear governance structures to enhance the effectiveness of communication channels.

- Strengthening Networking, Media Representation, and Information Dissemination (Guideline 8.2):The data reveal moderate to high levels of support for strengthening networking, media representation, and information dissemination among social entrepreneurs across regions.This underscores the importance of leveraging communication channels to foster connections, raise awareness, and share knowledge and best practices within the social entrepreneurship community.To enhance effectiveness, policymakers could invest in networking events, create platforms for knowledge exchange, and collaborate with media outlets to amplify the voices of social entrepreneurs and showcase their impact.

- Intensifying Cooperation across Sectors (Guideline 8.3):The data indicate moderate to high levels of support for intensifying cooperation between social entrepreneurs, the economy, the public sector, and the academic community across regions.This highlights the recognition of the value of cross-sectoral collaboration in driving innovation, scaling impact, and addressing complex social challenges.To leverage this support, policymakers could facilitate platforms for multi-stakeholder dialogue, incentivize collaboration through funding mechanisms, and promote joint initiatives that harness the strengths of different sectors to achieve common goals.

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparison with Previous Studies

4.2. Implications of Findings

4.3. Role of Digital Technologies

- Operational Efficiency: Digital tools, such as project management software, customer relationship management (CRM) systems, and financial management applications, streamline operations and improve efficiency. These tools help social enterprises manage resources more effectively and focus on their core mission [54,55].

- Impact Measurement: Digital technologies facilitate the collection and analysis of data on social impact. Advanced analytics and data visualization tools enable social enterprises to measure their impact more accurately, providing insights that can guide strategic decisions and demonstrate value to stakeholders [56].

- Innovation and Collaboration: Digital platforms support innovation by enabling collaboration across geographical boundaries. Social entrepreneurs can leverage digital tools to co-create solutions, share best practices, and collaborate with diverse stakeholders, fostering a culture of innovation and continuous improvement [57,58,59,60].

- Digital Divide: Disparities in digital access and literacy can limit the benefits of digital technologies for some regions and groups. Efforts should be made to bridge this digital divide through targeted interventions and capacity-building initiatives [58].

- Data Security and Privacy: The increasing reliance on digital tools raises concerns about data security and privacy. Social enterprises must implement robust data protection measures to safeguard sensitive information and maintain stakeholder trust [59].

4.4. Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

- Regional Variations in Support: The level of support for various guidelines varied significantly across different regions. Pannonian Croatia showed the highest support for public awareness initiatives, indicating a strong belief in the importance of raising awareness about social entrepreneurship’s role and benefits. Adriatic Croatia demonstrated a strong preference for guidelines related to general policy issues, reflecting regional priorities and socio-economic conditions.

- Stakeholder Perceptions: Different stakeholder groups, including local authorities, social entrepreneurs, and community organizations, exhibited varied perceptions and priorities regarding the guidelines. In Zagreb, the emphasis was on establishing a coordinating body and providing education to stakeholders, highlighting the region’s focus on structured support and capacity building.

- Challenges and Opportunities: Key challenges identified include the need for more comprehensive legislative frameworks and financial incentives to support social enterprises. Opportunities lie in enhancing public awareness and education, which are seen as critical for fostering a supportive ecosystem for social entrepreneurship.

- Effectiveness of Existing Policies: This study found that existing policies are moderately effective in promoting social entrepreneurship and addressing societal needs. However, there is a need for more targeted and region-specific policies to enhance their impact.

- Impact of Policy Support Levels: Variations in policy support levels across regions and stakeholder groups significantly impact the growth and sustainability of social enterprises. Regions with higher support levels tend to have more vibrant and sustainable social entrepreneurship ecosystems.

- Policy Design and Implementation: Policymakers should consider regional specificities when designing and implementing social entrepreneurship policies. Tailored approaches that address local needs and priorities are more likely to succeed.

- Education and Awareness: Investing in public awareness campaigns and educational programs can significantly enhance the visibility and understanding of social entrepreneurship. These efforts can help build a supportive ecosystem and encourage more individuals to engage in social enterprises.

- Legislative and Financial Support: Strengthening legislative frameworks and providing financial incentives are crucial for supporting the growth of social enterprises. Policymakers should focus on creating enabling environments that facilitate the sustainability of social enterprises.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Doherty, B.; Haugh, H.; Lyon, F. Social enterprises as hybrid organizations: A review and research agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2014, 16, 417–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, A. The legitimacy of social entrepreneurship: Reflexive isomorphism in a pre-paradigmatic field. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2010, 34, 611–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saebi, T.; Foss, N.J.; Linder, S. Social entrepreneurship research: Past achievements and future promises. J. Manag. 2019, 45, 70–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerlin, J.A. Defining social enterprise across different contexts: A conceptual framework based on institutional factors. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2013, 42, 84–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission; Directorate-General for Employment; Social Affairs and Inclusion; Carini, C.; Borzaga, C.; Chiomento, S.; Franchini, B.; Galera, G.; Nogales, R. Social Enterprises and Their Ecosystems in Europe—Comparative Synthesis Report; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020; Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2767/567551 (accessed on 31 May 2024).

- Liptrap, J.S. The social enterprise company in Europe: Policy and theory. J. Corp. Law Stud. 2020, 20, 495–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defourny, J.; Nyssens, M. Fundamentals for an International Typology of Social Enterprise Models. VOLUNTAS Int. J. Volunt. Nonprofit Organ. 2017, 28, 2469–2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, E.; Andreaus, M. Social impact and performance measurement systems in an Italian social enterprise: A participatory action research project. J. Public Budg. Account. Financ. Manag. 2020, 33, 289–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, J.G.; Olsen, J.P. Rediscovering Institutions: The Organizational Basis of Politics; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsson, K.; Saxonberg, S. (Eds.) Beyond NGO-Ization: The Development of Social Movements in Central and Eastern Europe; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lasinska, K. Social Capital in Eastern Europe: Poland an Exception? Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Baturina, D. ‘The New Kid in Town’: Towards Shaping the Understanding of Social Entrepreneurship in Croatia. In Social Enterprise Developments in the Balkans: Joint Volume by the Balkan Social Enterprise Research Network; Baglioni, S., Roy, M., Mazzei, M., Srbijanko, J.K., Bashevska, M., Eds.; Reactor—Research in Action: Skopje, North Macedonia, 2017; pp. 81–99. [Google Scholar]

- Bacq, S.; Eddleston, K.A. A resource-based view of social entrepreneurship: How stewardship culture benefits scale of social impact. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 152, 589–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, A.; Teasdale, S. Neoliberalism by stealth? Exploring continuity and change within the UK social enterprise policy paradigm. Policy Politics 2017, 45, 323–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadaoui, S.; Belgaroui, R. Social Entrepreneurship: Concept Clarification. In Economics & Strategic Management of Business Process (ESMB): Proceedings of the International Conference on Business, Economics, Marketing & Management Research (BEMM’13); Volume 2, pp. 36–40. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/349088499_Social_entrepreneurship_concept_clarification (accessed on 31 May 2024).

- Bacq, S.; Wasieleski, D.M.; Weber, J. Preface—Social Entrepreneurship: Origins, Trends, and Future Directions. In Social Entrepreneurship (Business and Society 360); Wasieleski, D.M., Weber, J., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2021; pp. xi–xviii. [Google Scholar]

- Hertel, C.; Bacq, S.; Lumpkin, G. Social Performance and Social Impact in the Context of Social Enterprises—A Holistic Perspective. 2020. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/343126135_Social_Performance_and_Social_Impact_in_the_Context_of_Social_Enterprises-A_Holistic_Perspective (accessed on 31 May 2024).

- Bacq, S.; Janssen, F. The multiple faces of social entrepreneurship: A review of definitional issues based on geographical and thematic criteria. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2011, 23, 373–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 3rd ed.; Knight, V., Connely, S., Eds.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, J.C.; Kreider, H.; Mayer, E. Combining Qualitative and Quantitative Methods in Social Inquiry. In Research Methods in the Social Sciences; Somekh, B., Lewin, C., Eds.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005; pp. 274–282. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, M.L.; Jolley, J.M. Research Design Explained, 7th ed.; Potter, J., Rosenberg, R., Eds.; Wadsworth Cengage Learning: Belmont, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Defourny, J.; Nyssens, M.; Brolis, O. Testing the Relevance of Major Social Enterprise Models in Western Europe. In Social Enterprise in Western Europe; Defourny, J., Nyssens, M., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 333–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bejaković, P. Vodič za Analizu Socijalnih Utjecaja; Institut za Javne Financije: Zagreb, Croatia, 2009; Available online: https://dokumen.tips/documents/vodic-za-analizu-socijalnih-utjecaja-ijfhr-socijalnihnadalje-kroz-analizu.html?page=12 (accessed on 31 May 2024).

- Tišma, S.; Maleković, S.; Jelinčić, D.A.; Mileusnić Škrtić, M.; Keser, I. From Science to Policy: How to Support Social Entrepreneurship in Croatia. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2022, 15, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidović, D.; Baturina, D. Social Enterprise in Croatia. In Social Enterprise in Central and Eastern Europe: Charting New Territories; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 40–55. [Google Scholar]

- Wirth, S.; Tschumi, P.; Mayer, H.; Bandi Tanner, M. Change agency in social innovation: An analysis of activities in social innovation processes. Reg. Stud. Reg. Sci. 2023, 10, 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baturina, D.; Mihály, M.; Haska, E.; Ciepielewska-Kowalik, A.; Kiss, J.; Agolli, A.; Bashevska, M.; Srbijanko, J.; Rakin, D.; Radojičić, V. The Role of External Financing in the Development of Social Entrepreneurship in CEE Countries. In Social Enterprise in Central and Eastern Europe; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 218–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, G.; Kaeding, N. Tax Policy and Entrepreneurship: A Framework for Analysis; FISCAL FACT No. 647; Tax Foundation: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; Available online: https://files.taxfoundation.org/20190403131203/Tax-Policy-and-Entrepreneurship-A-Framework-for-Analysis1.pdf (accessed on 31 May 2024).

- Jelinčić, D.A. Procjena društvenog utjecaja smjernica za razvoj javnih politika—društveno poduzetništvo i mladi. In Dijalogom do Hrvatske Mreže za Društveno Poduzetništvo; Centar za Ruralni Razvoj CERURA HR: Sinj, Croatia, 2023; Available online: https://www.socialbiz.cerura.hr/images/Science/Intervencije/7_ADU_DP_i_mladi.pdf (accessed on 31 May 2024).

- Kraus, S.; McDowell, W.; Ribeiro-Soriano, D.E.; Rodríguez-García, M. The role of innovation and knowledge for entrepreneurship and regional development. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2021, 33, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavel, R. Social entrepreneurship and vulnerable groups. J. Community Posit. Pract. 2011, 2, 59–77. [Google Scholar]

- Pallavi, G.; Santosh, D.T.; Ashoka, N. Agricultural Entrepreneurship: Exploring Opportunities, Challenges, and Impacts. In Recent Advances in Agricultural Sciences and Technology; Biradar, N., Shah, R.A., Ahmad, A., Eds.; Dilpreet Publishing House: New Delhi, India, 2023; pp. 599–608. [Google Scholar]

- Gadanakis, Y.; Campos-González, J.; Jones, P. Linking Entrepreneurship to Productivity: Using a Composite Indicator for Farm-Level Innovation in UK Agriculture with Secondary Data. Agriculture 2024, 14, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gossel, B.M. Analogies in Entrepreneurial Communication and Strategic Communication: Definition, Delimitation of Research Programs and Future Research. Int. J. Strateg. Commun. 2022, 16, 134–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepoutre, J.; Justo, R.; Terjesen, S.; Bosma, N. Designing a Global Standardized Methodology for Measuring Social Entrepreneurship Activity: The Global Entrepreneurship Monitor Social Entrepreneurship Study. Small Bus. Econ. 2013, 40, 693–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, F.M. A positive theory of social entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 111, 335–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, O.R. Institutional Dynamics: Emergent Patterns in International Environmental Governance; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012; p. 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killian, S.; O’Regan, P. Taxation and Social Enterprise: Constraint or Incentive for the Common Good. J. Social. Entrep. 2018, 10, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolaković, M.; Turuk, M.; Turčić, I. Social Entrepreneurship: Perspective of Croatia. In Entrepreneurship Development in the Balkans: Perspective from Diverse Contexts; Ramadani, V., Kjosev, S., Sergi, B.S., Eds.; Emerald Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2023; pp. 113–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolk, A. Advancing Social Entrepreneurship: Recommendations for Policy Makers and Government Agencies. In Advancing Innovation for Social Impact; Kreitz, K., Ebinger, C.G., Eds.; The Aspen Institute and Rootcause: Washington, DC, USA, 2008; Available online: https://www.aspeninstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/files/content/docs/pubs/AdvSocEntrp%20FINAL.pdf (accessed on 31 May 2024).

- Patel, A.; Ambati, N.R. Policy Ecosystem of Social Entrepreneurship for Sustainable and Resilient Development: A Doctrinal Review. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Symposium on Disaster Resilience and Sustainable Development, Virtual, 24–25 June 2021; Pal, I., Kolathayar, S., Tawhidul Islam, S., Mukhopadhyay, A., Ahmed, I., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Civil, Engineering. Springer: Singapore, 2023; Volume 294, pp. 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg-Postweiler, J.; Leicht-Scholten, C. Investigating the Institutional Embedding of Social Innovation at Five Leading Technical Universities in Europe. J. Social. Entrep. 2024, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verick, S.S. The Challenge of Youth Employment: New Findings and Approaches. Ind. J. Labour Econ. 2023, 66, 421–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, M.S.; Ghadah, A. Social entrepreneurship education: A conceptual framework and review. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2021, 19, 100533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indarti, N.; Anggadwita, G.; Purnomo, R.A.; Tomlins, R. Breaking Barriers! Social Entrepreneurship in Empowering People with Disabilities. J. Social. Entrep. 2024, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, J.; Stevenson, H.; Wei–Skillern, J. Social and Commercial Entrepreneurship: Same, Different, or Both? Entrep. Theory Pract. 2006, 30, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, R.; Fink, M.; Lang, R.; Maresch, D. Rural Social Enterprise: An Emerging Strategic Action Field. In Social Entrepreneurship and Innovation in Rural Europe, 1st ed.; Defourny, J., Hulgård, L., Nogales, R., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 142–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deže, J.; Sudarić, T.; Tolić, S. Social Innovations for the Achievement of Competitive Agriculture and the Sustainable Development of Peripheral Rural Areas. Economies 2023, 11, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Assessing the framework conditions for social innovation in rural areas. In OECD Local Economic and Employment Development (LEED) Papers; No. 2024/04; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2024; Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/content/paper/74367d76-en (accessed on 31 May 2024). [CrossRef]

- Si, S.; Hall, J.; Suddaby, R.; Ahlstrom, D.; Wei, J. Technology, entrepreneurship, innovation and social change in digital economics. Technovation 2023, 119, 102484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambisan, S.; Wright, M.; Feldman, M. The digital transformation of innovation and entrepreneurship: Progress, challenges and key themes. Res. Policy 2019, 48, 103773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Chauhan, S.; Paul, J.; Jaiswal, M.P. Social entrepreneurship research: A review and future research agenda. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 113, 209–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, T.; Liu, M.J.; Phang, C.W.; Luo, J. Toward social enterprise sustainability: The role of digital hybridity. Technol. Forecast. Social. Chang. 2022, 175, 121360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallmuenzer, A.; Mikhaylov, A.; Chelaru, M.; Czakon, W. Adoption and performance outcome of digitalization in small and medium-sized enterprises. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2024, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menter, M. From technological to social innovation: Toward a mission-reorientation of entrepreneurial universities. J. Technol. Transf. 2023, 49, 104–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosário, A.T.; Dias, J.C. How has data-driven marketing evolved: Challenges and opportunities with emerging technologies. Int. J. Inf. Manag. Data Insights 2023, 3, 100203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schöning, M. Social Entrepreneurs as Main Drivers of Social Innovation. In Social Innovation. CSR, Sustainability, Ethics & Governance; Osburg, T., Schmidpeter, R., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandna, V. Social entrepreneurship and digital platforms: Crowdfunding in the sharing-economy era. Bus. Horiz. 2022, 65, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, S.; Vonmetz, K.; Bullini Orlandi, L.; Zardini, A.; Rossignoli, C. Digital entrepreneurship: The role of entrepreneurial orientation and digitalization for disruptive innovation. Technol. Forecast. Social. Chang. 2023, 193, 122638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sufyan, M.; Degbey, W.Y.; Glavee-Geo, R.; Zoogah, B.D. Transnational digital entrepreneurship and enterprise effectiveness: A micro-foundational perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 160, 113802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, W.; Zhou, L.; Shi, Q. Inclusion We Stand, Divide We Fall: Digital Inclusion from Different Disciplines for Scientific Collaborations. In Wisdom, Well-Being, Win-Win. iConference 2024. Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Sserwanga, I., Joho, H., Ma, J., Hansen, P., Wu, D., Koizumi, M., Gilliland, A.J., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 14596, pp. 398–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, N.; Wang, C. Managing privacy in the digital economy. Fundam. Res. 2021, 1, 543–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Guadaño, J.; Diez, R.M. Social Entrepreneurship Impact in Ten EU Countries with Supportive Regulations. J. Knowl. Econ. 2023, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Li, G.; Zhang, X. Comparison of social entrepreneurship courses in different disciplines: Teaching approach and learning process. Entrep. Educ. 2023, 6, 245–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tišma, S.; Mileusnić Škrtić, M.; Maleković, S.; Jelinčić, D.A.; Keser, I. Empowering Innovation: Advancing Social Entrepreneurship Policies in Croatia. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6650. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16156650

Tišma S, Mileusnić Škrtić M, Maleković S, Jelinčić DA, Keser I. Empowering Innovation: Advancing Social Entrepreneurship Policies in Croatia. Sustainability. 2024; 16(15):6650. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16156650

Chicago/Turabian StyleTišma, Sanja, Mira Mileusnić Škrtić, Sanja Maleković, Daniela Angelina Jelinčić, and Ivana Keser. 2024. "Empowering Innovation: Advancing Social Entrepreneurship Policies in Croatia" Sustainability 16, no. 15: 6650. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16156650

APA StyleTišma, S., Mileusnić Škrtić, M., Maleković, S., Jelinčić, D. A., & Keser, I. (2024). Empowering Innovation: Advancing Social Entrepreneurship Policies in Croatia. Sustainability, 16(15), 6650. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16156650