Evaluation of Urban Traditional Temples Using Cultural Tourism Potential

Abstract

1. Introduction

- ① Conducting a theoretical review on traditional temples, general temples, mountain temples, and urban temples as cultural tourism resources in Section 2.1.

- ② Deriving the attraction attributes and factors of the cultural tourism resources necessary for this study from Section 2.2 to Section 3.2 based on a literature review.

- ③ Developing indicators for each factor to construct an evaluation framework in Section 4.

- ④ Evaluating Bongeunsa and Jogyesa, which already attract many visitors, and five other urban traditional temples with significant tourism potential but fewer visitors in Section 5.

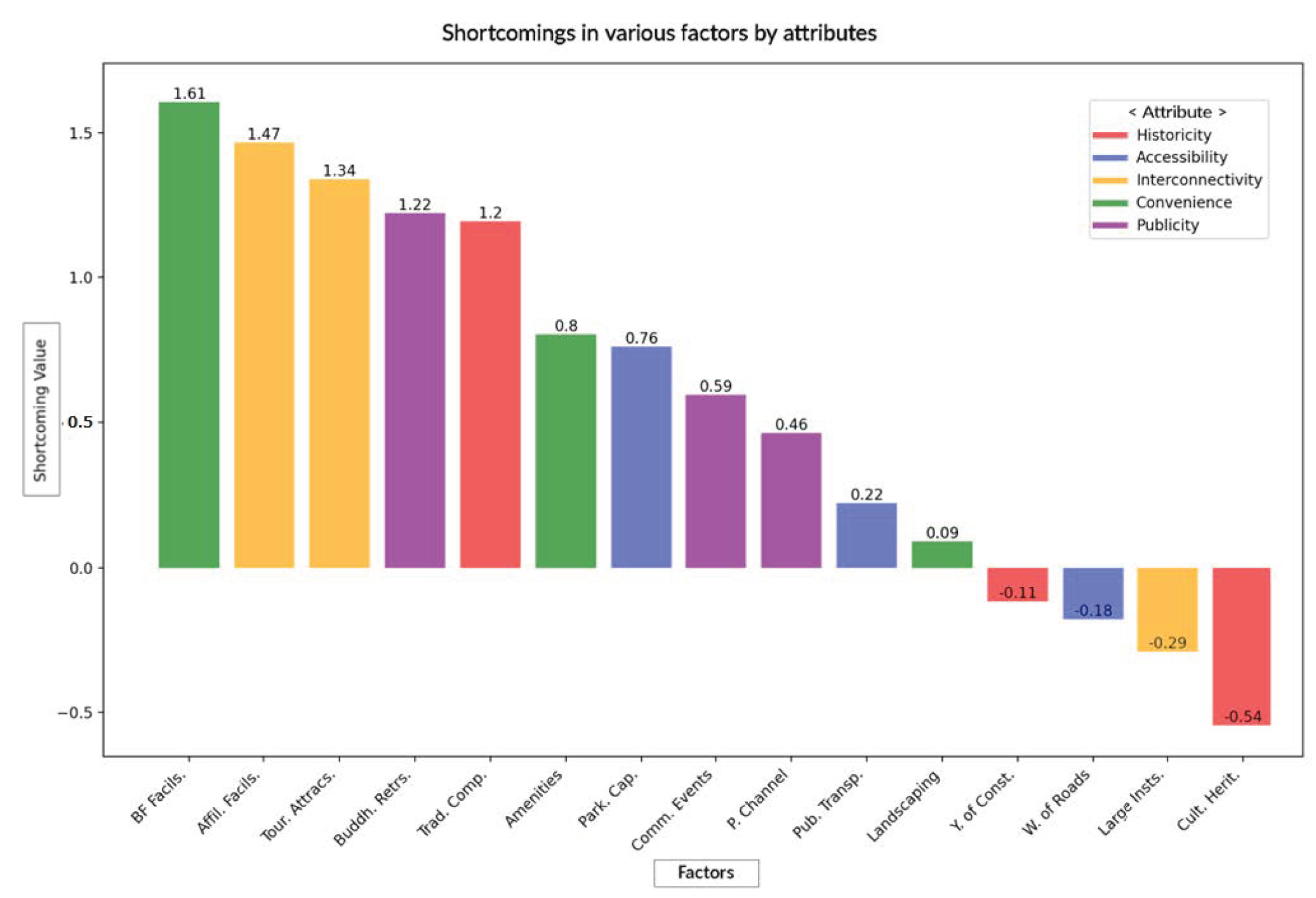

- ⑤ Executing a comparative analysis of Bongeunsa, Jogyesa, and five other temples to uncover factors that need improvement in Section 6.2.1.

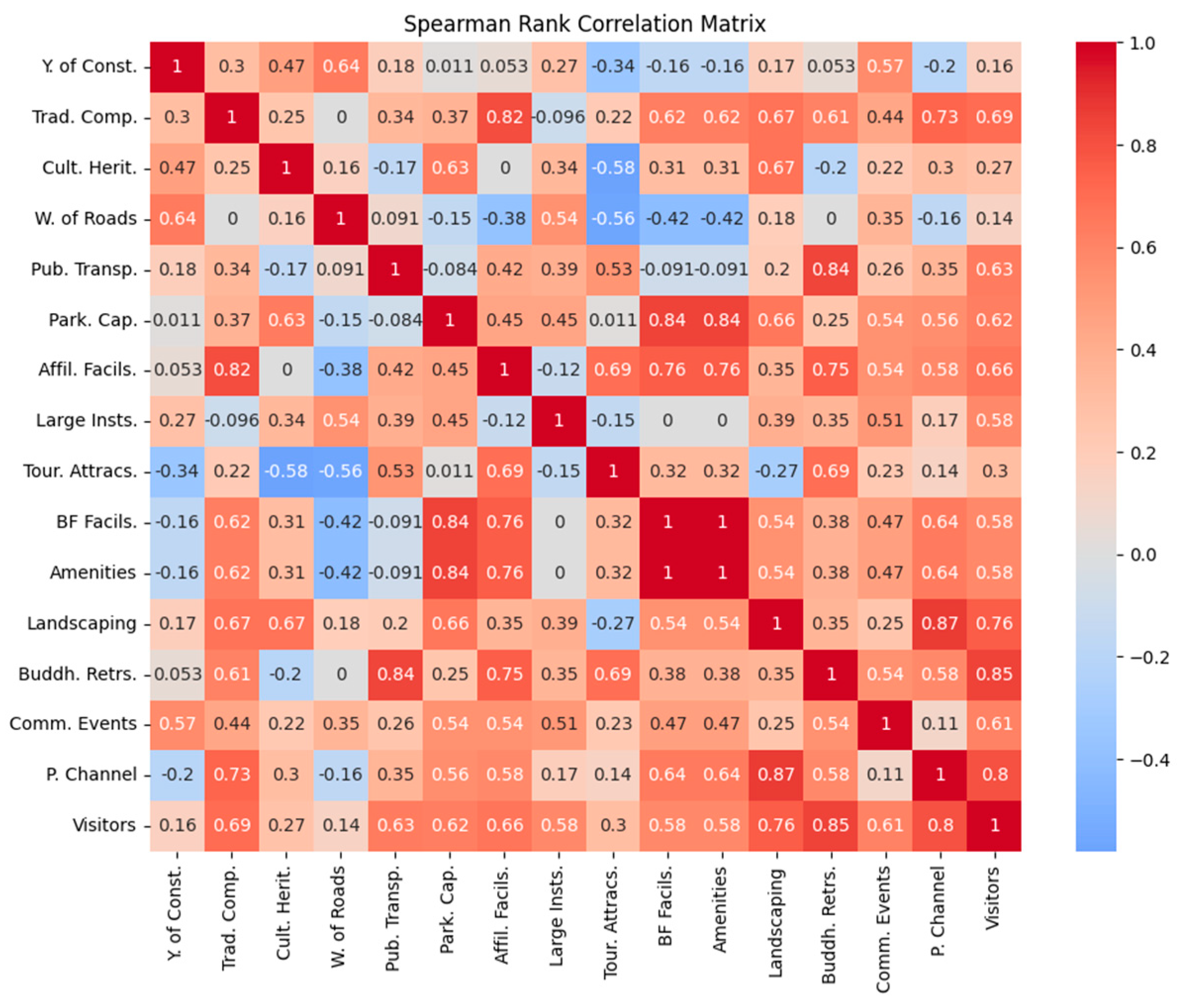

- ⑥ Using correlation analysis to identify high-priority factors for enhancing the tourism potential of urban traditional temples, while discussing the study limitations, improvement areas, and expected outcomes in Section 6.2.2.

- ⑦ Discussing the results obtained from the evaluation, including the study’s limitations, areas for improvement, and expected outcomes in Section 7. This discussion will also propose ways to apply the findings in future urban tourism research involving religious sites.

2. Literature Review

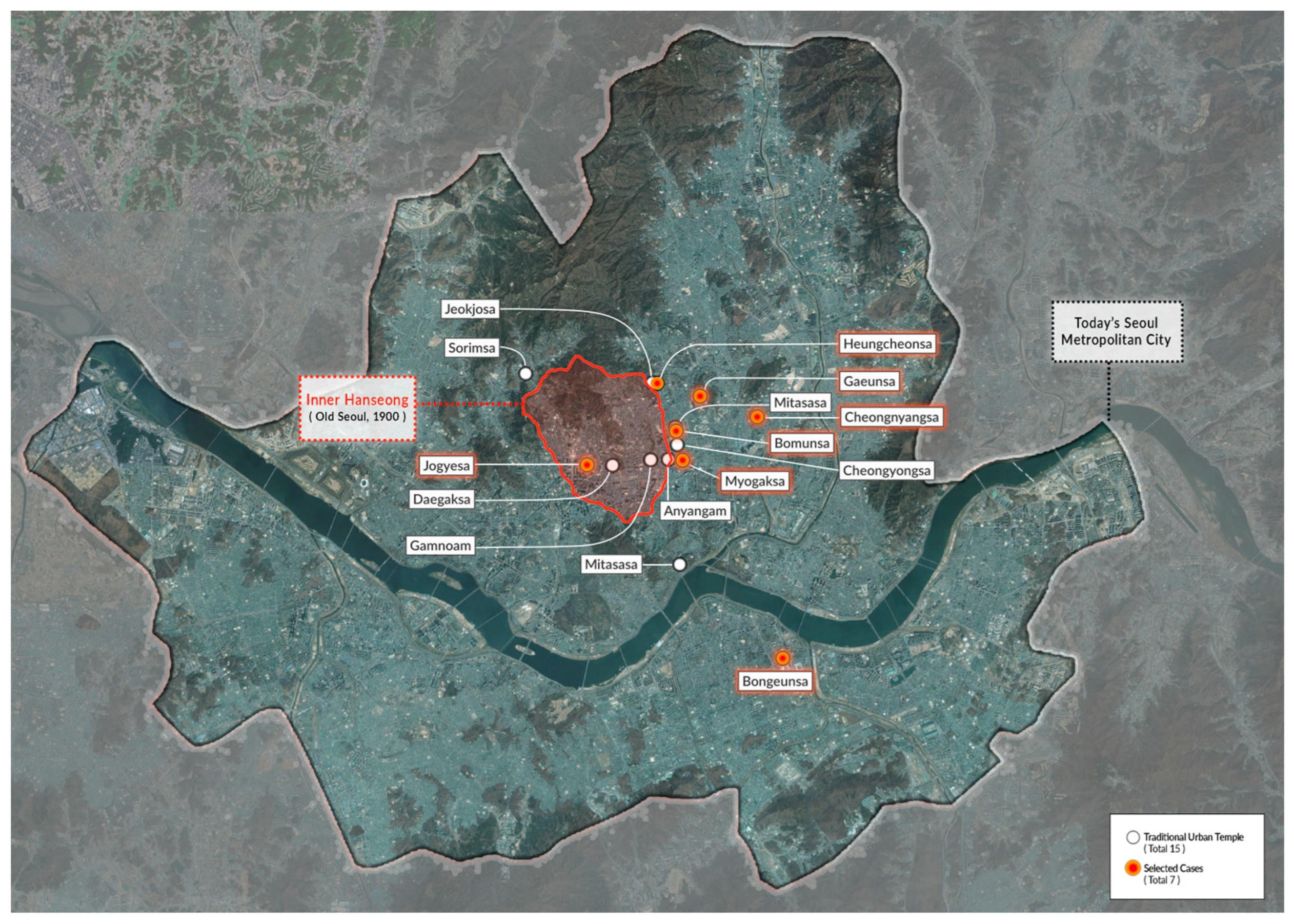

2.1. Urban Traditional Temples

2.1.1. Concept of Korean Traditional Temples

2.1.2. Classification of Temples Based on Location Conditions

| Type | Concept |

|---|---|

| Mountain traditional temple | Located in mountainous areas in natural surroundings, mountain peaks, or valleys, providing an immersive experience of Korea’s exceptional natural landscapes [20,21]. |

| Urban traditional temple | Located in the urban area, providing facilities and programs that consider urban characteristics. |

2.2. Cultural Tourism Resources in the City Center

2.2.1. Concept of Cultural Tourism Resources

2.2.2. Cultural Tourism Resource Attraction Attributes

3. Attributes of Urban Traditional Temples

3.1. Urban Traditional Temple Attraction Attributes

3.1.1. Historicity

3.1.2. Accessibility

3.1.3. Inter-Connectivity

3.1.4. Convenience

3.1.5. Publicity

3.2. Attractive Attribute Factors

4. Assessment Framework Development

4.1. The Historicity Indicator Criteria

4.1.1. Year of Construction

4.1.2. Traditional Temple Composition

4.1.3. Cultural Heritage

4.2. Accessibility Indicator Criteria

4.2.1. The Width of the Access Road

4.2.2. Public Transportation

4.2.3. Parking Capacity

4.3. Inter-Connectivity Indicator Criteria

4.3.1. Affiliate Facilities

4.3.2. Large Institutions

4.3.3. Tourist Attractions

4.4. Convenience Indicator Criteria

4.4.1. Barrier-Free Facilities

4.4.2. Amenities

4.4.3. Landscaping

4.5. Publicity Indicator Criteria

4.5.1. Buddhist Retreats

4.5.2. Community Events

4.5.3. Promotional Channels

5. Analysis and Evaluation of Urban Traditional Temples

6. Results

- -

- Cheongnyangsa scored low overall with significant room for improvement in all the evaluated attributes.

- -

- Myogaksa showed moderate accessibility and inter-connectivity but lacked convenience.

- -

- Heungcheonsa exhibited strong historicity and convenience but had low inter-connectivity.

- -

- Bomunsa had good historicity and accessibility, though inter-connectivity was low.

- -

- Gaeunsa had balanced scores with strong accessibility but needed improvements in convenience and inter-connectivity.

- -

- Jogyesa had high scores in convenience and publicity, showing strong overall performance.

- -

- Bongeunsa achieved the highest total score, excelling in historicity, accessibility, and convenience.

6.1. Reliability Assessment

6.2. Verification of the Research Hypotheses

6.2.1. Comparative Analysis of Tourism Factors

- (1)

- Data Collection and Preprocessing

- (2)

- Calculating the Average Tourism Factor for Bongeunsa and Jogyesa

- (3)

- Calculating Weighted Averages for Other Temples

- (4)

- Identifying Deficient Elements Through Comparison with Bongeunsa and Jogyesa

- (5)

- Calculating the Total “Shortcomings” Value for Each Major Attribute

- ▪

- Testing Research Hypothesis 1 (H1)

6.2.2. Correlation Analysis of Tourism Factors

- ▪

- Testing Research Hypothesis 2 (H2)

7. Discussions and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

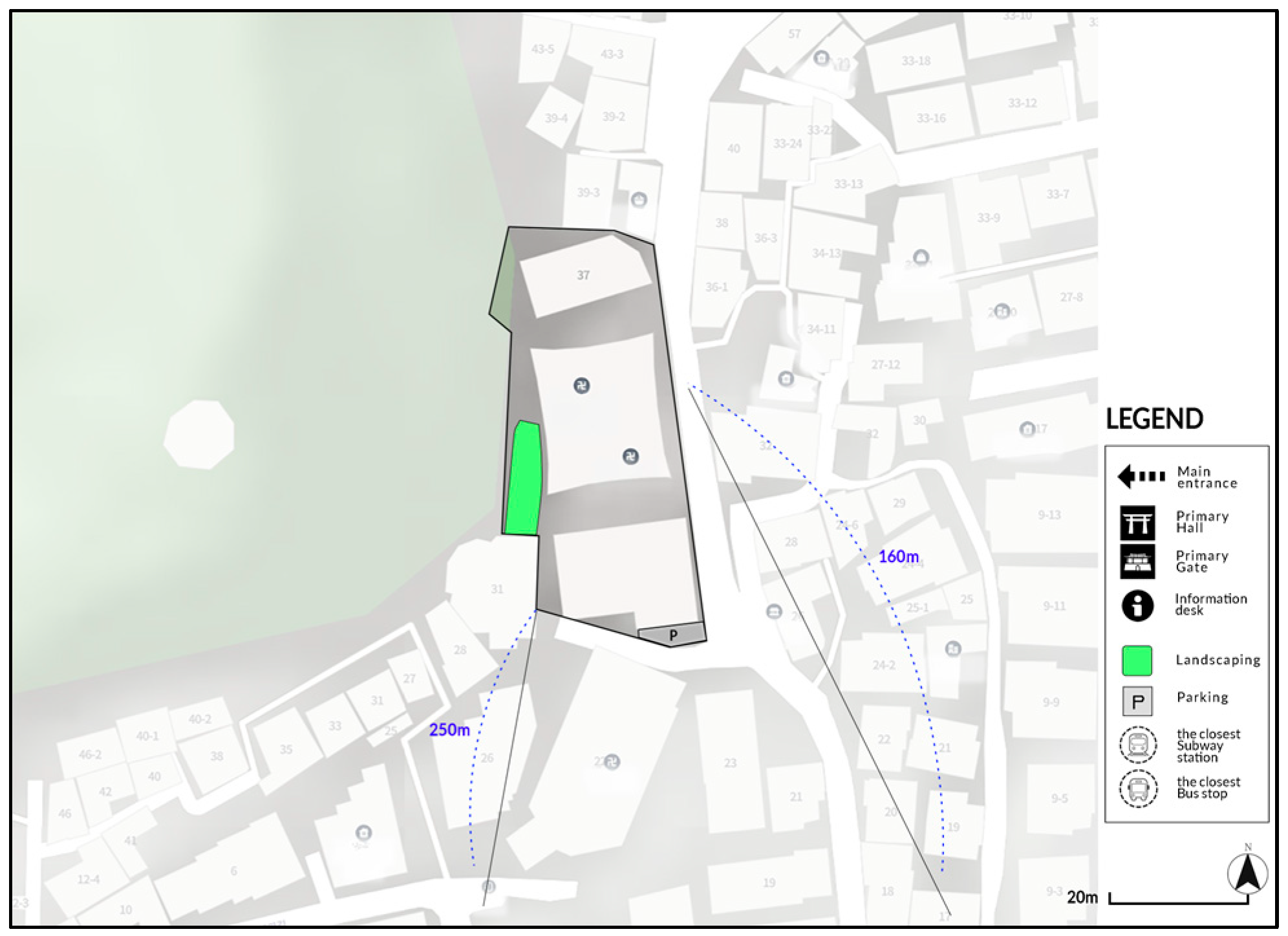

Appendix A. Case Analysis

| Attribute | Factor | Indicator | Evaluation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | |||

| H | Year of Construction | ● | Originally established at the site of Hongneung during the Silla dynasty and later moved to its current location in 1895. | ||

| Traditional Temple Composition | ● | Contains Gwaneumjeon, Geungnakbojeon, Daebeopjeon, Daeungjeon, Muryangsujeon, Seonhyewon, Yeomhwasil, Dongbyeoldang, Jabiwon, and Chilseonggak, but lacks a mountain gate in the Chil-dang garam configuration. | |||

| Cultural Heritage | ● | No national treasures or treasures. | |||

| A | Width of Access Roads | ● | The average width of the access road is 12 m. | ||

| Public Transportation | ● | There is a bus stop within 300 m of the temple. | |||

| Car Capacity | ● | Considering the total floor area of the temple, it should accommodate 17 parking spaces (2532.49/150 = 16.89), but it can only accommodate about 10, thus falling short of the installation standards. | |||

| I | Affiliate Facilities | ● | No affiliate facilities operated by the temple. | ||

| Large Institutions | ● | No large institutions within 1 km. | |||

| Tourist Attractions | ● | No tourist attractions within 1 km. | |||

| C | BF Facilities | ● | No barrier-free facilities for visitors. | ||

| Amenities | ● | No amenities for visitors. | |||

| Landscape | ● | The total floor area of the temple is 2532.49 m2, so a landscaping area of at least 1183.95 m2 (7893.00 × 0.15) is required. The actual landscaping area is 1347.40 m2, thus meeting the standards. | |||

| P | Buddhist Retreats | ● | No Buddhist retreats. | ||

| Community Events | ● | 1 community event on Buddha’s Birthday. | |||

| Promotional Channels | ● | No promotional channels. | |||

| Attribute | Factor | Indicator | Evaluation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | |||

| H | Year of Construction | ● | Founded in 1930 and has undergone two renovations and expansions to achieve its current appearance. | ||

| Traditional Temple Composition | ● | Consists of Daeungjeon, Daebulbojeon, Wontongbojeon, Nagaseonwon, Sansingak, Yosa, Jonggak, and Chilseonggak. In the Chil-dang garam configuration, it includes the Buddha hall, lecture hall, monks’ hall, kitchen, and toilet but it does not include the mountain gate or bathhouse. | |||

| Cultural Heritage | ● | No national treasures or treasures. | |||

| A | Width of Access Roads | ● | The average width of the access road is 4 m. | ||

| Public Transportation | ● | Public transportation options around Myogaksa Temple include a subway station and bus stops, both located within 300 m of the entrance. | |||

| Parking Capacity | ● | Considering the total floor area of the temple, it should accommodate 10 parking spaces (1695.84/150 = 9.30), but it can only accommodate about 5, thus limiting visits by private vehicles. | |||

| I | Affiliate Facilities | ● | Operates the “Seoul Buddhist Cultural University”, providing a basic education platform for the general public to systematically learn about Buddhism. | ||

| Large Institutions | ● | No large institutions within 1 km. | |||

| Tourist Attractions | ● | The Dongmyo Flea Market, Seoul Folk Flea Market, and Heunginjimun, all designated as tourist sites by the Seoul Metropolitan Government, are within 1 km. | |||

| C | BF Facilities | ● | No barrier-free facilities for visitors. | ||

| Amenities | ● | No amenities for visitors. | |||

| Landscape | ● | The total floor area of Myogaksa Temple is 1695.84 m2, so a landscaping area of at least 117.48 m2 (1174.8 × 0.1) is required. However, the actual landscaping area of Myogaksa Temple is 51.9 m2, thus falling short of the legal requirement. | |||

| P | Buddhist Retreats | ● | Myogaksa Temple regularly conducts temple stay programs and offers separate temple stay programs for foreigners. | ||

| Community Events | ● | No community events. | |||

| Promotional Channels | ● | Although Myogaksa has Instagram and Facebook channels, they have not been used since 2020. The official website is only available in Korean. | |||

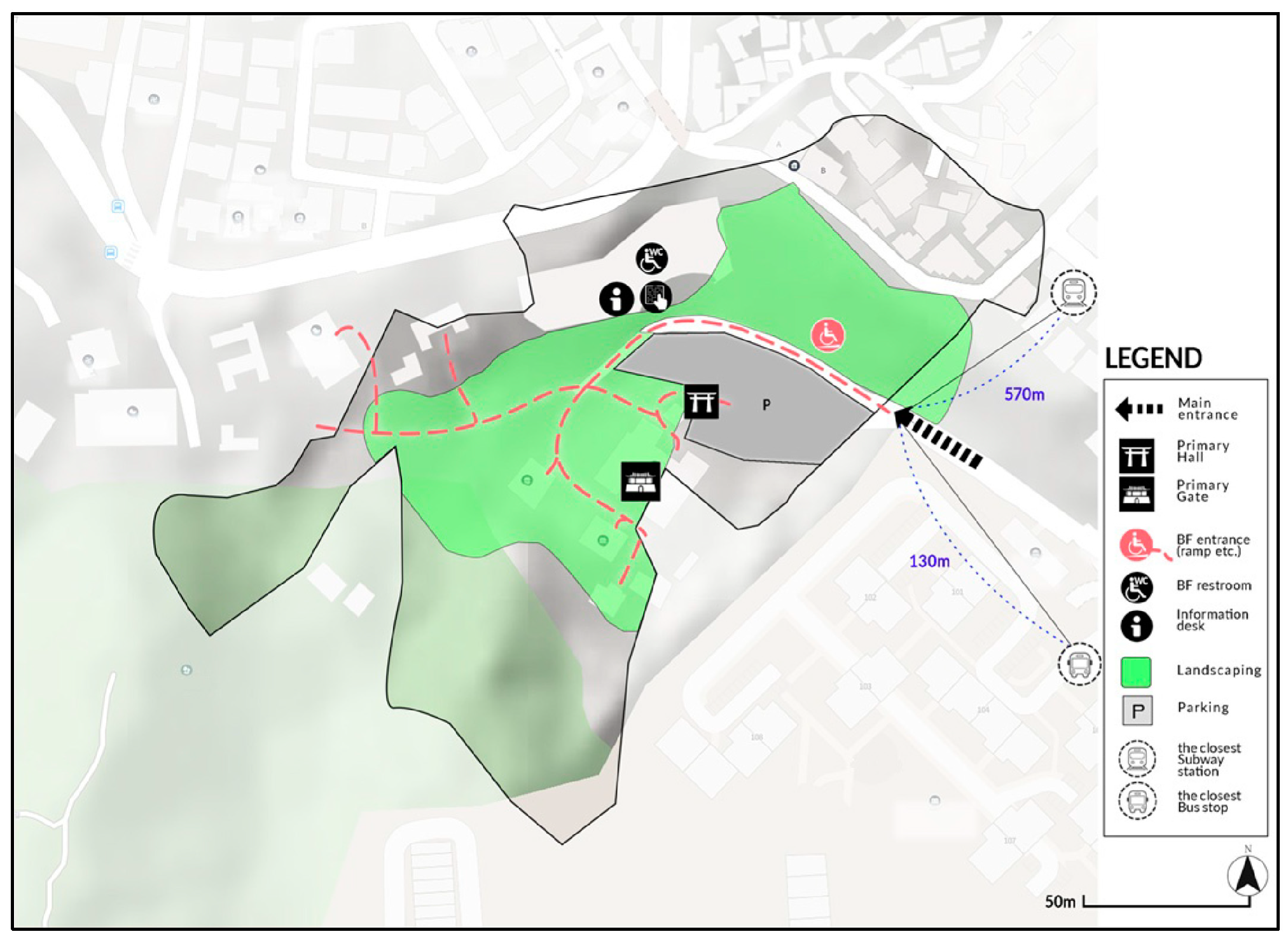

| Attribute | Factor | Indicator | Evaluation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | |||

| H | Year of Construction | ● | Founded in 1397, it has been known as Heungcheonsa since 1865. | ||

| Traditional Temple Composition | ● | Consists of Jeonbeophwajeon, Geungnakbojeon, Myeongbujeon, Daebang, Yonghwajeon, Doksunggak, Bukgeukjeon, Jonggak, Nojeon, Sangakseonwon, Neutinamu daycare center, and a seven-story stone pagoda, exceeding the configuration of Chil-dang garam. | |||

| Cultural Heritage | ● | Two treasures: The Heungcheonsa Bronze Bell (Treasure No. 1460) and The Heungcheonsa Gilt-Bronze Seated Bodhisattva of Compassion with 42 Arms (Treasure No. 1891). | |||

| A | Width of Access Roads | ● | The average width of the access road is 7 m. | ||

| Public Transportation | ● | Accessible by public transportation, including a subway station and a bus stop. The bus stop is located 100 m from the entrance, but the subway station is more than 500 m away. | |||

| Parking Capacity | ● | Considering the total floor area of the temple, it should accommodate 17 parking spaces (2518.57/150 = 16.79). Heungcheonsa has space for 40 parking spots and includes a drop zone for large buses to unload passengers. The parking lot is open to the public for free. | |||

| I | Affiliate Facilities | ● | Operates the Neutinamu daycare center, providing education for preschool children. | ||

| Large Institutions | ● | No large institutions within 1 km. | |||

| Tourist Attractions | ● | No tourist attractions within 1 km. | |||

| C | BF Facilities | ● | In 2020, Heungcheonsa implemented plans considerate of people with disabilities when constructing the Jeonbeophwajeon building. All the spaces in Heungcheonsa were made accessible by installing ramps to create barrier-free areas, and the entrance widths were made at least 1.2 m wide to accommodate wheelchair users. A disabled-access restroom was planned inside Jeonbeophwajeon, and a braille and audio signboard was installed at the temple entrance to assist with navigation. | ||

| Amenities | ● | Heungcheonsa has explanations and information boards for each building within the temple, but no directional signs on the temple grounds. The information desk, which provides visitors with information, is located inside Jeonbeophwajeon. There is a book cafe and a lounge but no nursing room. | |||

| Landscape | ● | The legal landscaping area for Heungcheonsa is 6759.15 m2 (45,061.00 × 0.15). The actual landscaping area of Heungcheonsa is 38,873.7 m2, thus exceeding 20% of the site area. | |||

| P | Buddhist Retreats | ● | No Buddhist retreats. | ||

| Community Events | ● | Heungcheonsa holds the Neutinamu Children and Family Festival annually. Although there are lantern and bell-ringing events, other events are not held regularly on a quarterly basis. | |||

| Promotional Channels | ● | Heungcheonsa uses its website and YouTube for promotional purposes, with videos being uploaded every 3 to 4 months on YouTube. However, information is not provided in languages other than Korean. | |||

| Attribute | Factor | Indicator | Evaluation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | |||

| H | Year of Construction | ● | Founded by Ven. Damjin in 1115. | ||

| Traditional Temple Composition | ● | Consists of Daeungjeon, Geungnakjeon, Seokguram, Hojimun, Seonbuljang, Bogwangjeon, Sanreungak, Seokguram Nojeon, Samseonggak, Byeoldang, and Yosache, exceeding the configuration of Chil-dang garam. | |||

| Cultural Heritage | ● | The Myobeopyeonhwagyeong Volumes 3–7 (Treasure No. 1164-2). | |||

| A | Width of Access Roads | ● | The average width of the access road is 9 m. | ||

| Public Transportation | ● | Public transportation options around Bomunsa Temple include a subway station and bus stops, with Bomun Station located approximately 285 m away and the nearest bus stop about 380 m away. | |||

| Parking Capacity | ● | Considering the total floor area of 6705.87 m2, 45 parking spaces are required (6705.87/150 = 44.71). However, since it cannot accommodate this number of vehicles, parking is only available for devotees and temple staff. | |||

| I | Affiliate Facilities | ● | Operates two facilities (Eunyoung kindergarten, Eunyoung daycare center). | ||

| Large Institutions | ● | No large institutions within 1 km. | |||

| Tourist Attractions | ● | No tourist attractions within 1 km. | |||

| C | BF Facilities | ● | No barrier-free facilities for visitors. | ||

| Amenities | ● | No amenities for visitors. | |||

| Landscape | ● | The total floor area exceeds 2000 m2, so a landscaping area of at least 4336.95 m2 (28,913 × 0.15) must be planned as a natural green space. The green area of Bomunsa is 18,576.9 m2, providing ample greenery. | |||

| P | Buddhist Retreats | ● | Bomunsa Temple regularly conducts Buddhist basic doctrine classes. | ||

| Community Events | ● | Three community events per year (winter red bean porridge sharing event, multicultural family feast on 7/7, Buddha’s Birthday) | |||

| Promotional Channels | ● | Bomunsa’s promotional channels include its official website in Korean and YouTube. | |||

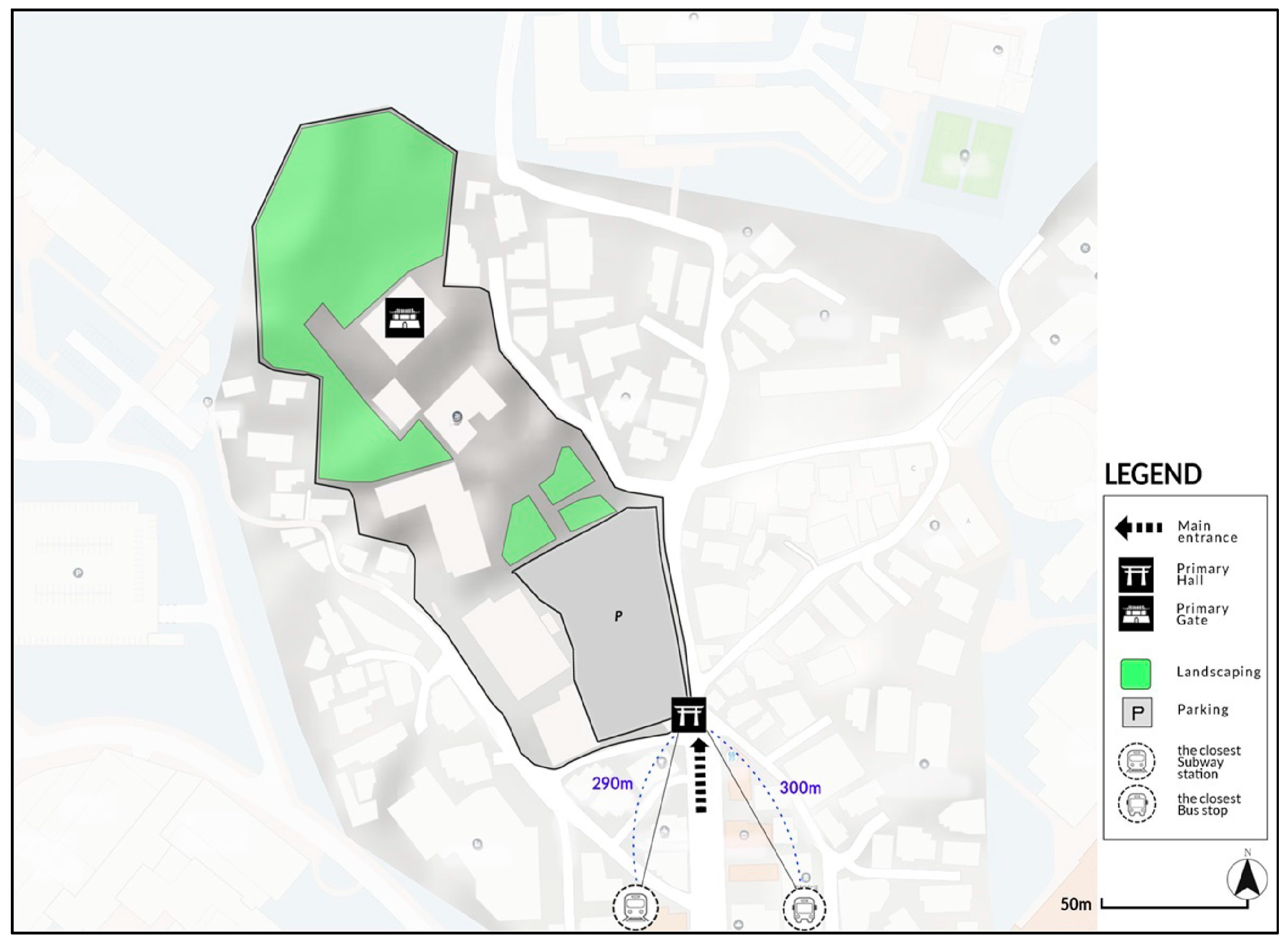

| Attribute | Factor | Indicator | Evaluation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | |||

| H | Year of Construction | ● | Founded under the name “Yeongdosa” in 1396 but relocated to its current location in 1730 according to the old document Sagi. (The exact time when it was renamed to Gaeunsa is not known). | ||

| Traditional Temple Composition | ● | Includes the main hall, lecture hall, monks’ quarters, and the temple gate among the Chil-dang-garam configuration, but the others are not present. | |||

| Cultural Heritage | ● | The Wooden Seated Amitabha Buddha Statue and Vow Document (Treasure No. 1649). | |||

| A | Width of Access Roads | ● | The average width of the access road is 12 m. | ||

| Public Transportation | ● | Public transportation options around Gaeunsa Temple include a subway station and bus stops, both located within 300 m of the entrance. | |||

| Parking Capacity | ● | Considering the total floor area of the temple, it should accommodate 30 parking spaces (4424.8/150 = 29.5), but it actually provides 95 parking spaces and has a sufficient drop zone for large buses to unload passengers. However, the parking lot is operated as a paid facility. | |||

| I | Affiliate Facilities | ● | It used to operate “Sangha University”, but the building is currently under construction for kindergarten events. | ||

| Large Institutions | ● | Korea University is located right next door, providing support for Buddhist clubs and scholarship programs. | |||

| Tourist Attractions | ● | No tourist attractions within 1 km. | |||

| C | BF Facilities | ● | No barrier-free facilities for visitors. | ||

| Universal Design | ● | No universal design for visitors. | |||

| Landscape | ● | The total floor area of Gaewoonsa exceeds 2000 m2, so it must secure at least 2507.55 m2 (16,717 × 0.15) as a landscaping area. Gaewoonsa’s landscaping area is 6361.2 m2, which constitutes more than 20% of the site area. | |||

| P | Buddhist Retreat | ● | In 2023, the Buddhist knowledge education program Gaewoon Hakdang was launched. | ||

| Community Event | ● | In 2023, Sansa Music Concert was held as a one-time event and is not a regular program. Other than this, there are no other events. | |||

| Promotional Channels | ● | Gaewoonsa has no promotional channels other than its official website, which is only available in Korean. | |||

| Attribute | Factor | Indicator | Evaluation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | |||

| H | Year of Construction | ● | Completed Daewoongjeon of Jogyesa in 1938. | ||

| Traditional Temple Composition | ● | Consists of Daeungjeon, Geungnakjeon, Daeseolbeon-jeon, Iljumun, Gwaneumjeon, Seungso, a children’s Dharma hall, a dining hall, and a pottery workshop, exceeding the configuration of Chil-dang garam. | |||

| Cultural Heritage | ● | No national treasures, treasures, or historic sites. | |||

| A | Width of Access Roads | ● | The average width of the access road is 6.5 m. | ||

| Public Transportation | ● | Public transportation options around Jogyesa Temple include a subway station and bus stops, both located within 300 m of the entrance. | |||

| Parking Capacity | ● | Considering the total floor area of the temple, it should accommodate 90 parking spaces (13,487.88/150 = 89.92), but it actually provides 130 parking spaces and has a designated area for large buses to unload passengers. However, the parking lot is operated as a paid facility. | |||

| I | Affiliate Facilities | ● | Operates five facilities(Seoul Senior Welfare Center, Jongno Senior Comprehensive Welfare Center, and three others) | ||

| Large Institutions | ● | No commercial facilities within 1 km. | |||

| Tourist Attractions | ● | Seoul Crafts Museum and Gwanghwamun area, including King Sejong Statue and Sejong Performing Arts Center. | |||

| C | BF Facilities | ● | Wheelchair rentals and ramps were planned for people with disabilities to ensure ease of movement. Braille and audio guide signs were installed, and the entrance widths were made at least 1.2 m wide. Additionally, accessible restrooms were provided. | ||

| Amenities | ● | An information desk called Gapi, benches for visitors to use freely, a nursing rooms, and children’s play facilities. | |||

| Landscape | ● | The total floor area of Jogyesa Temple is 16,022.80 m2, so a landscaping area of at least 2403.42 m2 (16,022.80 × 0.15) is required. However, the actual landscaping area of Jogyesa Temple is 7609.3 m2, thus exceeding 20% of the site area. | |||

| P | Buddhist Retreats | ● | Buddhist painting and wood carving education, pilgrimages to sacred sites, education at Baeksong University for seniors, temple stays, and calligraphy, painting, and yoga courses for non-religious individuals. | ||

| Community Events | ● | Buddha’s Birthday event and the Chrysanthemum Fragrance Sharing Festival every fall. | |||

| Promotional Channels | ● | Official website in Korean and English and a separate promotional office. | |||

| Attribute | Factor | Indicator | Evaluation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | |||

| H | Year of Construction | ● | Founded by Monk Yeonhui under the name “Gyeongseonsa” in 794. | ||

| Traditional Temple Composition | ● | Consists of JinYeomun, Seoraewon, Beopwangru, Seonbuldang, Daeungjeon, Jijangjeon, Yeongsanjeon, Unhadang, Simgeomdang, Jongnu, Jonggak, Bowoodang, and Daraeheon, exceeding the configuration of Chil-dang garam. | |||

| Cultural Heritage | ● | Two treasures: The Bongeunsa Bronze Incense Burner with Silver Inlay (Treasure No. 321) and The Bongeunsa Wooden Seated Buddha Triad (Treasure No. 1819). | |||

| A | Width of Access Roads | ● | The average width of the access road is 12 m. | ||

| Public Transportation | ● | Public transportation options around Jogyesa Temple include a subway station and bus stops, both located within 300 m of the entrance. | |||

| Parking Capacity | ● | Considering the total floor area of the temple, it should accommodate 83 parking spaces (12,360.26/150 = 82.40), but it actually provides 193 parking spaces and has a designated area for large buses to unload passengers. The parking lot is operated for free. | |||

| I | Affiliate Facilities | ● | Established the social welfare corporation “Bongeun” and operates 15 facilities, including “Pangyo” Senior Comprehensive Welfare Center, “Daechi” Senior Welfare Center, and 13 others. | ||

| Large Institutions | ● | COEX, a large-scale complex space with exhibition halls, conference centers, and an aquarium, is about 250 m away, but there are no cooperative programs with Bongeunsa Temple. | |||

| Tourist Attractions | ● | COEX, also known as “COEX Mall” is an attractive destination for domestic and international tourists due to its diverse tourism and leisure facilities, including an aquarium, a large shopping mall, and a cinema. | |||

| C | BF Facilities | ● | Help bells, braille guidance, accessible toilets (with emergency bells), and minimized obstacles for wheelchair access | ||

| Amenities | ● | Walking paths using stepping stones, two rest deck facilities, and foreigner information desk and reception | |||

| Landscape | ● | The total floor area of Jogyesa Temple is 75,636.00 m2, so a landscaping area of at least 11,345.4 m2 (75,636.00 × 0.15) is required. However, the actual landscaping area of Jogyesa Temple is 34,381.00 m2, thus exceeding 20% of the site area. | |||

| P | Buddhist Retreats | ● | Bongeunsa Temple regularly conducts temple stay programs and offers Buddhism introduction courses for non-religious individuals. | ||

| Community Events | ● | “Bongjuk Week” cultural event (Buddha’s Birthday event), academic achievement ceremonies, New Year’s temple bell-ringing ceremony, annual Baekjung festival, lotus festival, and exhibitions and assistance for the less fortunate. | |||

| Promotional Channels | ● | There is an official website, a monthly magazine, and a YouTube channel but no support for languages other than Korean. | |||

References

- Jeon, M.S.; Jeong, M.U. A study on urban tourism resources development in Seoul City. Acad. Korea Tour. Policy 2003, 9, 217. [Google Scholar]

- Urošević, M.; Stanojević, M.; Đorđević, D. Urban tourism destinations in the world. Econ. Themes 2023, 61, 343–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D. How visitors perceive heritage value—A quantitative study on visitors’ perceived value and satisfaction of architectural heritage through SEM. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangchaoy, T. Tourism Industry and Services; Silpakorn University: Phetchaburi, Thailand, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Guriţă, D.; Scortescu, F.I. Religious tourism and sustainable development of the economy in the context of globalization in the northeast area of Romania. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visarado, P.R. Buddhist tourism management for sustainable community development. Int. J. Multidiscip. Cult. Relig. Stud. 2021, 2, 79–88. [Google Scholar]

- Dumitrașcu, A.V.; Teodorescu, C.; Cioclu, A. Accessibility and tourist satisfaction—Influencing factors for tourism in Dobrogea, Romania. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, T.; Iida, A.; Hino, K.; Murayama, A.; Hiroi, U.; Terada, T.; Koizumi, H.; Yokohari, M. Use of urban green spaces in the context of lifestyle changes during the COVID-19 pandemic in Tokyo. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venter, Z.S.; Barton, D.N.; Gundersen, V.; Figari, H.; Nowell, M. Urban nature in a time of crisis: Recreational use of green space increases during the COVID-19 outbreak in Oslo, Norway. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 104075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jim, C.; Chen, W.Y. Recreation–amenity use and contingent valuation of urban greenspaces in Guangzhou, China. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2006, 75, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krushelnickaya, E.I. Features of the Natural Framework of the Belgorod Region as a Basis for the Development of Recreation and Tourism Areas; Bulletin of the Belgorod State Technological University named after V.G. Shukhov: Belgorod, Russia, 2016; Volume 7, pp. 59–65. [Google Scholar]

- Danilina, N.; Tsurenkova, K.; Berkovich, V. Evaluating urban green public spaces: The case study of Krasnodar Region cities, Russia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 14059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, J.; Chen, Y. A Creative Analysis of Factors Affecting the Landscape Construction of Urban Temple Garden Plants Based on Tourists’ Perceptions. Sustainability 2022, 14, 991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Wang, L. Research on integral protection of urban temple gardens—A case study of Guodusi Temple in Wuhan City. J. Huazhong Agric. Univ. 2016, 35, 50–54. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Kostopoulou, S. Architectural heritage and tourism development in urban neighborhoods: The case of Upper City, Thessaloniki, Greece. In Conservation of Architectural Heritage; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 139–152. [Google Scholar]

- National Law Information Center. Traditional Temple Preservation Act. 2020. Available online: https://www.law.go.kr/LSW//lsInfoP.do?lsId=000784&ancYnChk=0#0000 (accessed on 22 May 2024).

- Cha, J.; The Reason Temples Moved to the Mountains. Cultural Heritage Newspaper. Available online: https://kchn.kr/column/?q=YToyOntzOjEyOiJrZXl3b3JkX3R5cGUiO3M6MzoiYWxsIjtzOjQ6InBhZ2UiO2k6Njt9&bmode=view&idx=1865578&t=board&category=x88Q147i47 (accessed on 19 June 2024).

- Choi, W.S. Fengshui’s interaction with Buddhism in Korea. J. Korean Geogr. Soc. 2009, 44, 77–88. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.S. The history of space organization in construction of temple and the possibility of continuance and transformation. Namdo Cult. Stud. 2017, 32, 57–88. [Google Scholar]

- Academy of Korean Studies. Sansa, Korea’s Mountain Monasteries. Available online: https://dh.aks.ac.kr/~heritage/wiki/index.php/Sansa,_Korea’s_Mountain_Monasteries (accessed on 23 June 2024).

- Korean Buddhist Temple Preservation Project. What Is a Sansa, Korea’s Mountain Monastery? Available online: http://www.koreansansa.net/ktp/sansa/sansa_01.do (accessed on 23 June 2024).

- Choi, O.Y. A study on the physical peculiarity and space constitution of Buddhist temples in the modern city. J. Archit. Inst. Korea 1994, 14, 195–198. [Google Scholar]

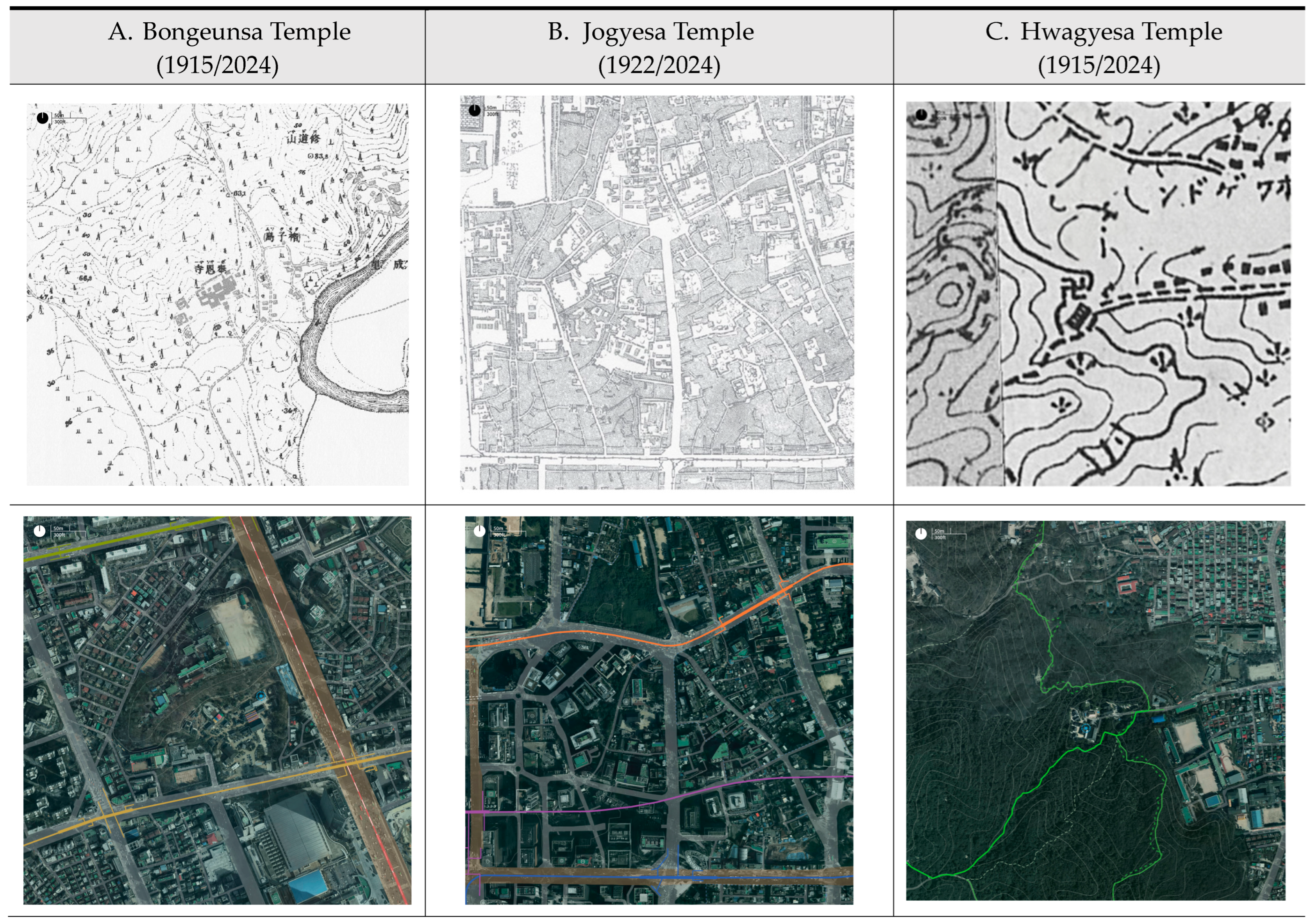

- Kim, I.R.; Jung, W.J. Reinterpretation of Seoul’s traditional Buddhist temples through ancient documents and old maps. Landsc. Geogr. 2021, 31, 36–50. [Google Scholar]

- Seoul Metropolitan Government. Old Maps Showing the History of Seoul. Smart Seoul Map. Available online: https://map.seoul.go.kr/smgis2/short/6N28l (accessed on 23 June 2024).

- Zhu, H.; Liu, J.-m.; Tao, H.; Zhang, J. Evaluation and spatial analysis of tourism resources attraction in Beijing based on Internet information. J. Nat. Resour. 2015, 30, 2081–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teshome, E.; Dereje, M.; Asfaw, Y. Potentials, challenges and economic contributions of tourism resources in the South Achefer district, Ethiopia. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2022, 8, 2041290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denman, R. Guidelines for Community-Based Ecotourism Development; WWF International: Ledbury, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Paudel, T.; Lee, G. The cognitive effects of a skyscraper landmark of traditional design on city image and place dependence: The moderating effect of cultural sphere. J. Korean Tour. Res. 2020, 34, 37–59. [Google Scholar]

- Park, H.J. A study on the research method for the value evaluation of tourism resources in the capital. Acad. Korea Tour. Policy 2000, 6, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.; Han, B. Perception of convention destination image based on evaluation dimensions. J. Tour. Res. 2007, 22, 441–459. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie, J.R.B.; Goeldner, C.R.; McIntosh, R.W. Tourism: Principles, Practices, Philosophies; John and Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, H. Redefining Cultural Tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1996, 23, 707–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Tourism Organization. The State’s Role in Protecting and Promoting Culture as a Factor of Tourism Development and the Proper Use and Exploitation of the National Cultural Heritage of Sites and Monuments for Tourism; WTO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, G. ATLAS Cultural Tourism Project. Available online: https://www.richardstourism.com/atlas-cultural-tourism-project (accessed on 21 June 2024).

- Travis, A. Tourism and Cultural Change. In Proceedings of the Tourism and Cultural Change, Llangollen, UK, 8–10 September 1989; F.J. Stummann and European Centre for Traditional and Regional Cultures: Llangollen, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Yeo, B.; Choi, I. Cases and implications for the use of historical & cultural heritage in China: Focusing on the case of developing “cultural tourism” resources using China’s four major historical novels. J. Chin. Cult. Stud. 2022, 55, 29–52. [Google Scholar]

- Bachleitner, R.; Zins, A.H. Cultural tourism in rural communities: The residents’ perspective. J. Bus. Res. 1999, 44, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T. Competitiveness strategies for developing tourism resources in island regions. In Proceedings of the Seoul Association for Public Administration 2007 Winter Conference, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 15–16 February 2007; pp. 363–396. Available online: https://www.dbpia.co.kr/journal/articleDetail?nodeId=NODE00818324 (accessed on 23 June 2024).

- Kim, G.S.; Ahn, Y.J. The relationships of cultural tourism attraction attributes, resources interpretation and tourist satisfaction. J. Tour. Stud. 2005, 19, 247–272. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, T.-H.; Yu, W.-D. A study on the landscape attractions evaluative systems of Gyeongju historic heritage sites. J. Korean Inst. Landsc. Archit. 2014, 42, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Y. A Study on the Relationship between Experience Factors and Value of Experience in Cultural Heritage Tourism. Master’s Thesis, Chonnam National University, Gwangju, Republic of Korea, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Park, E.; Choi, B.; Ka, J. The effects of the attractiveness of a cultural heritage site on visitors’ satisfaction and post-purchase behavior intentions: Focused on visitors to Gyeongbok Palace. J. Tour. Leis. Res. 2010, 22, 211–229. [Google Scholar]

- Kerstetter, D.L.; Confer, J.J.; Graefe, A.R. An exploration of the specialization concept within the context of heritage tourism. J. Travel Res. 2001, 39, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josiam, B.M.; Mattson, M.; Sullivan, P. The Historaunt: Heritage tourism at Mickey’s Dining Car. Tour. Manag. 2004, 25, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, Z. Search of Politics; Stanford University Press: Redwood City, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Mousavi, S.S.; Doratli, N.; Mousavi, S.N.; Moradiahari, F. Defining cultural tourism. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Civil, Architecture and Sustainable Development (CASD-2016), London, UK, 1–2 December 2016; pp. 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.S. A study on the resource development of cultural tourism. J. Tour. Inf. 1999, 3, 211–241. [Google Scholar]

- Santana, J.M. Managing Conflict in User-Oriented Development Environments: Effects on Information Systems Success. Ph.D. Dissertation, Florida International University, Miami, FL, USA, 1997; p. 9726723. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.; Perdue, R.R. The influence of image on destination attractiveness. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2011, 28, 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formica, S.; Uysal, M. Destination attractiveness based on supply and demand evaluations: An analytical framework. J. Travel Res. 2006, 44, 418–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, L.; Mellor, R.; Livaic, Z.; Edwards, D.; Kim, C. Attributes of destination competitiveness: A factor analysis. Tour. Anal. 2004, 9, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.; Yoon, Y.; Park, N. A study on travel satisfaction for segmented groups of cultural destination attributes: Focusing on the moderating effect using Fisher’s Z value. J. Korean Geogr. Soc. 2008, 43, 938–950. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M. A study on the tourism information service system in a tourist resort. J. Tour. Leis. Res. 1994, 6, 69–92, Korean Tourism and Leisure Society. [Google Scholar]

- Korean Tourism and Leisure Society. A study on the satisfaction assessment of cultural tourism interpretation. J. Tour. Leis. Res. 1999, 11, 23–47. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, G.; Choi, N. The influences of the ecotourism motive on the attitude, resource interpretation, and satisfaction of tourists. J. Tour. Food Beverage Manag. 2001, 12, 97–117. [Google Scholar]

- Sparks, B. Planning a wine tourism vacation? Factors that help to predict tourist behavioural intentions. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 1180–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Lu, L.; Tong, S.-R.; Lu, S.; Yang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Liang, D.-d. Residents’ attitudes to tourism development in ancient village resorts: Case study of World Cultural Heritage of Xidi and Hong villages. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2004, 14, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoica, G.D.; Andreiana, V.-A.; Duica, M.C.; Stefan, M.-C.; Susanu, I.O.; Coman, M.D.; Iancu, D. Perspectives for the development of sustainable cultural tourism. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, G. Cultural Tourism: Global and Local Perspectives; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Haahti, A.J. Finland’s competitive position as a destination. Ann. Tour. Res. 1986, 13, 11–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, A. Environmental aesthetics and the dilemma of aesthetic education. J. Aesthetic Educ. 1976, 10, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojanic, D.C. The use of advertising in managing destination image. Tour. Manag. 1991, 12, 352–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, J.R.B.; Zins, M. Culture as determinant of the attractiveness of a tourism region. Ann. Tour. Res. 1978, 5, 252–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, G.S. A study on the tourism perception of American tourists. J. Hotel. Tour. Manag. Stud. 1987, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Gunn, C.A. Tourism Planning, 2nd ed.; Taylor and Francis: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, A.J. A Study on Tourism Destination Choice. Ph.D. Thesis, Sejong University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Inskeep, E. Tourism Planning: An Integrated and Sustainable Development Approach; John Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, G.S. On the program improvement of event tourism. J. Tour. Manag. Stud. 1995, 18, 159–186. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. International Cultural Tourism Charter; International Council on Monuments and Sites: Paris, France, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Keon, J.T. The Impact of the Post-Image and Motivation of Tourism-Event Upon Satisfaction and Revisit Intention. Ph.D. Thesis, Daegu University, Daegu, Republic of Korea, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, S.; Cai, L. Travel motivations and destination choice: A study of British outbound market. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2002, 13, 111–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, J. Effects on Tourist’s Satisfaction from Expectation and Perceived Performance in Cultural Destination. Master’s Thesis, Hanyang University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2002; pp. 12–27. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Vienna Memorandum; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization: Paris, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, M.; Lee, J. The influences of the attraction on tourist satisfaction and revisit intention in culture tourism festival: Focused on the 2004 Gyeongju Korean traditional liquor and rice cake festival. Tour. Manag. Res. 2005, 9, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, R.; Chung, B. A study on the cultural tourism resource development of filming locations. J. Soc. Sci. 2011, 17, 141–166. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, S.; Park, J.; Lee, C. Analysis of the relationships between the attractiveness attributes, satisfaction, and loyalty as cultural tourism resources—Focused on visitors of Gyeongbokgung Palace. Seoul Urban Res. 2012, 13, 149–166. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, L. An analysis on the influence of historical characteristics and cultural tourism sites based on visitors’ satisfaction and behavior intention: For the West Lake (Hangzhou) and East Lake (Wuhan). Master’s Thesis, Hanyang University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Law, C.M. Urban Tourism: Attracting Visitors to Large Cities; Mansell: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Jung, D. The influence of traditional culture landmark cognitive attributes and images on tourism satisfaction and behavioral intention: Focusing on Cheong Wa Dae. J. Hotel. Tour. Manag. 2022, 31, 253–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldie, C.F. Alternative visions of post-war reconstruction: Creating the modern townscape. Plan. Theory Pract. 2016, 17, 314–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolini, L.; le Clercq, F.; Kapoen, L. Sustainable accessibility: A conceptual framework to integrate transport and land use plan-making. Two test applications in the Netherlands and a reflection on the way forward. Transp. Policy 2005, 12, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.H. New Tourism Resources: Development, Utilization, and Management; Myungbo Publishing: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 1990; ISBN 2002012000144. [Google Scholar]

- Uysal, M.; Jurowski, C. Testing the push and pull factors. Ann. Tour. Res. 1994, 21, 844–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartner, W.C. Tourism image: Attribute measurement of state tourism products using multidimensional scaling techniques. J. Travel Res. 1989, 28, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freudendal-Pedersen, M. Sustainable urban futures from transportation and planning to networked urban mobilities. Transp. Res. D Transp. Environ. 2020, 82, 102310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, C.; Webster, C.; Pryor, M.; Tang, D.; Melbourne, S.; Zhang, X.H.; Liu, J.Z. Exploring associations between urban green, street design and walking: Results from the Greater London boroughs. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 143, 112–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danilina, N.; Vlasov, D.; Teplova, I. Social-oriented approach to street public spaces design. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 1030, 012059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schipperijn, J.; Cerin, E.; Adams, M.A.; Reis, R.; Smith, G.; Cain, K.; Christiansen, L.B.; Dyck, D.V.; Gidlow, C.; Frank, L.D.; et al. Access to parks and physical activity: An eight country comparison. Urban For. Urban Green. 2017, 27, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yue, W.; Fan, P.; Gao, J. Measuring the accessibility of public green spaces in urban areas using web map services. Appl. Geogr. 2021, 126, 102381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zou, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Guo, X.; Feng, X. Evaluating pedestrian environment using DeepLab models based on street walkability in small and medium-sized cities: Case study in Gaoping, China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. An analysis of satisfaction of urban tourism influenced by convenience of transportation: Mokpo City in Jeonnam Province. Culin. Sci. Hosp. Res. 2019, 25, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Sinha, K.C. Sustainability and urban public transportation. J. Transp. Eng. 2003, 129, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Jung, B. A study on the evaluation of urban tourist destination accessibility: A case study of Yangnim Modern History and Culture Village in Gwangju Metropolitan City. In Proceedings of the Korean Regional Development Association 2018 Spring Conference, Gwangju, Republic of Korea, 20 April 2018; pp. 327–339. Available online: https://www.dbpia.co.kr/journal/articleDetail?nodeId=NODE07564411 (accessed on 23 June 2024).

- Hou, L.; Wu, L.; Ju, S.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Lai, Z. The evolution patterns of tourism integration driven by regional tourism-economic linkages—Taking Poyang Lake Region, China, as an example. Growth Chang. 2021, 52, 1914–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T. An analysis on regional cultural policy and its developmental alternatives: With linkage to tourism. Korean Soc. Public Adm. Acad. J. 2003, 13, 247–274. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, G. The actual condition and development of programs for participation of temple in local community. J. Seon Cult. Stud. 2010, 9, 37–64. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, B.R. A study on the architectural planning and elements of contemporary Buddhist temples in urban area. J. Archit. Inst. Korea 1995, 11, 109–118. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, M. Zoning, tourism. In Encyclopedia of Tourism; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, K.; Hack, G. Site Planning, 3rd ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, J. Convenience is an important indicator of tourism quality. Guangming Daily. 2019. Available online: https://news.gmw.cn/2020-01/02/content_33447428.htm (accessed on 22 May 2024).

- Switzerland Tourism. Convenience. Annual Report 2019. Available online: https://report.stnet.ch/en/2019/convenience/ (accessed on 22 May 2024).

- Laws, E. Conceptualizing visitor satisfaction management in heritage settings: An exploratory blueprinting analysis of Leeds Castle, Kent. Tour. Manag. 1998, 19, 545–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, B.H.; Hong, G.P. A study on the external spaces of contemporary urban temples. In Proceedings of the Korean Society of Landscape Architecture 2002 Fall Conference, October, 2002, Seoul, Republic of Korea; pp. 33–37. Available online: https://www.dbpia.co.kr/journal/articleDetail?nodeId=NODE09421164 (accessed on 22 May 2024).

- Dore, L.; Crouch, G.I. Promoting destinations: An exploratory study of publicity programmes used by national tourism organisations. J. Vacat. Mark. 2003, 9, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen-Verbeke, M. Cultural tourism in the 21st century. World Leis. Recreat. 1996, 38, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, H.J.; Park, E.G. A study on the spatial composition of the contemporary Buddhist temple in urban context. Proc. Archit. Inst. Korea Conf.—Plan. Conf. Mater. 2000, 20, 163–166. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, K.-R. How Will Korean Buddhism Missionary in the Corona Era? Korean Assoc. Buddh. Profr. 2021, 27, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Encyclopedia of Korean Folk Culture. Chilseong Garam. Available online: https://encykorea.aks.ac.kr/Article/E0049782 (accessed on 22 May 2024).

- Ministry of Government Legislation. National Heritage Basic Act. 2024. Available online: https://www.law.go.kr/LSW/LsiJoLinkP.do?docType=JO&lsNm=%EA%B5%AD%EA%B0%80%EC%9C%A0%EC%82%B0%EA%B8%B0%EB%B3%B8%EB%B2%95&joNo=000300000&languageType=KO¶s=1 (accessed on 22 May 2024).

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport. Road Act [Effective from 17 May 2024] [Act No. 19587, 8 August 2023, Amended by Other Act]. 2023. Available online: https://www.law.go.kr (accessed on 22 May 2024).

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport. Regulations on the Decision, Structure, and Installation Standards for Urban Planning Facilities. 2021. Available online: https://www.law.go.kr/LSW/lsInfoP.do?lsId=009453&ancYnChk=0 (accessed on 22 May 2024).

- Seoul Metropolitan Government. Seoul Traffic Information System. Available online: https://topis.seoul.go.kr/map/openBusMap.do (accessed on 22 May 2024).

- U.S. Green Building Council. LEED v4 for Building Operations and Maintenance [Korean Version]. 2021. Available online: https://greenlog.or.kr/uploads/bbs/63/LEED_v4_EBOM_Korean.pdf (accessed on 22 May 2024).

- Ministry of Government Legislation. Installation Targets and Standards for Auxiliary Parking Facilities (Article 6, Paragraph 1 Related). Available online: https://www.law.go.kr/lsInfoP.do?lsId=004946&ancYnChk=0#0000 (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Oh, B.R. Establishment of the scope of neighborhood unit based on actual travel distance by using the data of Household Travel Daily Survey in Incheon. Incheon Stud. 2015, 23, 219–248. [Google Scholar]

- Jogyesa. Open Jogyesa with Citizens. Jogyesa News. Available online: https://www.jogyesa.kr/board/news/board_view.php?search_category=3&search_forward=previous&page=54&num=5567 (accessed on 25 June 2024).

- Seoul Metropolitan Government. 2040 Seoul Plan; Chapter 5.3.3 Northeastern Region; Seoul Metropolitan Government: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2023; pp. 150–155. [Google Scholar]

- Culture Tourism Industries Research Institute. Overview of the MICE Tourism Industry Research Institute. Dongguk University WISE Campus Industry-Academia Cooperation Foundation. Available online: https://iacf.dongguk.ac.kr/iacf/support_center/research/normal_research.html?idx=12&category=%EC%9D%BC%EB%B0%98%EC%97%B0%EA%B5%AC%EA%B8%B0%EA%B4%80&mode=view (accessed on 23 June 2024).

- Seoul Metropolitan Government. Seoul Tourist Guide & Map 2024. 2024. Available online: https://korean.visitseoul.net/map-guide-book (accessed on 22 May 2024).

- Korea Disabled People’s Development Institute. Barrier-Free (BF) Certification System Evaluation Items; Korea Disabled People’s Development: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, H.-J.; Ryoo, S.-L. An analysis of barrier-free design on accessibility of Han-ok style public buildings. J. Archit. Inst. Korea 2021, 37, 43–54. [Google Scholar]

- Seoul Public Design Guidelines 2020. Available online: https://news.seoul.go.kr/culture/archives/511341 (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Seoul Universal Design Application Guidelines 2022. Available online: https://news.seoul.go.kr/culture/archives/522959 (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Study on Universal Design of Traditional Cultural Heritage Tourism Facilities—Focusing on Joseon Dynasty Palaces. Available online: https://kiss.kstudy.com/Detail/Ar?key=3900474 (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Seoul Metropolitan Government. Seoul Building Ordinance: Article 24 (Landscaping on the Site). 2024. Available online: https://legal.seoul.go.kr/legal/english/front/page/law.html?pAct=lawView&pPromNo=166 (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Korea Institute of Civil Engineering and Building Technology. G-SEED 2016-2 v1.1: Green Building Certification Criteria Commentary; New Residential Buildings; Korea Institute of Civil Engineering and Building Technology: Goyang, Republic of Korea, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bongeunsa. Events. Available online: http://www.bongeunsa.org:90/ (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Jogyesa. Events. Available online: https://www.jogyesa.kr/ (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Gaeunsa. Gaeunsa: Official Website. Available online: http://www.gaeunsa.org/ (accessed on 23 June 2024).

- Bomunsa. Bomunsa: Official Website. Available online: http://www.bomunsa.or.kr/ (accessed on 23 June 2024).

- Heungcheonsa. Heungcheonsa: Official Website. Available online: http://www.heungcheonsa.net (accessed on 23 June 2024).

- Myogaksa. Myogaksa: Official Website. Available online: http://www.myogaksa.net/main_1.html (accessed on 23 June 2024).

- Cheongryangsa. Bomunsa: Official Website. Available online: http://www.cheongryangsa.org/htm/main.htm (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Ministry of Culture, Sports, and Tourism. List of Designated Traditional Temples. Available online: https://www.mcst.go.kr/kor/s_policy/dept/deptView.jsp?pSeq=1694&pDataCD=0417000000&pType=03 (accessed on 22 May 2024).

- Korea Tourism Organization. Korea Tourism Data Lab: Visitor Statistics for Traditional Temples in Seoul. Available online: https://datalab.visitkorea.or.kr/datalab/portal/loc/getTourDataFormBeta.do (accessed on 23 June 2024).

| Type | Concept |

|---|---|

| Traditional temple | Possesses historical characteristicsEssential for understanding the flow of Korean Buddhism, culture, arts, and architectural historyA typical model for examining the generation and transformation of Korean cultureHolds high cultural value |

| General temple | Not designated as a traditional temple |

| Researcher (Year) | Cultural Tourism Resource Attributes |

|---|---|

| Carlson (1976) | historic, culture, art, education [61] |

| Ritchie; Zins (1978) | social and cultural attributes, tradition, food, history, architectural styles, crafts, recreational activities, art and music, language, habiliment, education, religion [63] |

| Haahti (1986) | accessibility, cultural experience [60] |

| Jeon (1987) | safety and security, historical and cultural attractions, residents’ attitudes [64] |

| Gunn (1988) | history, archeology, legend, folk [65] |

| Lee (1988) | historically and culturally interesting streets [66] |

| Inskeep (1991) | archeological, historical sites, unique cultural forms, arts and crafts, distinctive economic activity, distinctive urban area, museums and cultural facilities, cultural celebration [67] |

| Bojanic (1991) | interesting cities, historic sites, safety, hospitality, language, historic ruins [62] |

| Kim (1995) | diversity, convenience, comfort, friendliness, experience and education, historical and cultural value, uniqueness, informativeness, accessibility, local character, folklore [68] |

| ICOMOS (1999) | natural and cultural heritage, diversity, living cultures [69] |

| Keon (2000) | historical and cultural activities, educational value of history, regional characteristics [70] |

| Jang; Cai (2002) | natural and historical environment [71] |

| Im (2002) | surrounding environment, preservation status, atmosphere, souvenirs, rest and convenience facilities, signage and service, programs, buildings, cultural experience [72] |

| UNESCO (2005) | character-defining elements of the urban structure, urban environmental quality, social and cultural vitality [73] |

| Kwon; Lee (2005) | celebrations, street snacks, education, particularity [74] |

| Lee; Chung (2011) | extensive differentiation, destination value without 3S (sand, sun, sea), activity and environmental friendliness [75] |

| Yoon; Park; Lee (2012) | interpretation, educability, uniqueness, programs, convenience, hospitality [76] |

| Kim (2011) | accessibility, service, convenience, surrounding environment, storytelling, historicity and uniqueness, programs, information [49] |

| Kang; Yu (2014) | urban historical and cultural heritage resources, urban environment [40] |

| Sunli (2019) | natural landscape characteristics, historical and cultural characteristics, convenience [77] |

| Attributes | Factor | Concept |

|---|---|---|

| Historicity | Year of Construction | Year of construction based on current location, not the original founding date |

| Traditional Temple Composition | Adherence to the elements of the traditional composition of Korean Buddhist architecture known as “Chil-dang garam” | |

| Cultural Heritage | Existence of national treasures/treasures/historic sites | |

| Accessibility | Width of Access Road | Width of the main access road to the temple |

| Public Transportation | Number of available modes of transportation and existence of the facilities within 1 km (bus stops or subway stations, etc.) | |

| Parking Capacity | Existence of a parking lot and its fee | |

| Inter-connectivity | Affiliate Facilities | Operation under delegation of facilities that provide public services or contribute to public welfare |

| Large Institutions | Presence of institutions that often serve as stimulants of major economic, educational, or social drivers within a city near temples, within one kilometer of the temple (universities, hospitals, complex facilities, etc.) | |

| Tourist Attractions | Presence of facilities supporting tourism activities within one kilometer of the temple (museums, galleries, shopping malls, etc.) | |

| Convenience | Barrier-Free Facilities | Facilities for individuals with disabilities (accessible parking spaces and restrooms, wheelchair ramps, tactile blocks, etc.) |

| Amenities | Consideration of amenities in temples (information and guidance signs, information desks, safety/rest areas, nursing rooms, etc.) | |

| Landscape | The ratio of the area of landscaping facilities installed within the inner part of the outermost temple building to the total area of the temple | |

| Publicity | Buddhist Retreats | Buddhist programs offered by temples that are open to the general public (temple stays, scripture class, etc.) |

| Community Events | Non-religious local events conducted by the temple which are open to the public (Buddha’s Birthday festival, sharing events, etc.) | |

| Promotional Channels | Promotional means for domestic and international visitors |

| Attribute | Factor | Indicator | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | ||

| H | Year of Construction | Modern (after 1910) | Joseon dynasty (before 1910) | Before Goryeo dynasty (before 1392) |

| Traditional Temple Composition | Non-compliant with Chil-dang garam | Compliant with Chil-dang garam | Additional traditional compositions beyond Chil-dang garam | |

| Cultural Heritage | None | Possessing treasures or historic Site | Possessing national treasures | |

| A | Width of Access Roads | Less than 4 m | 4~8 m | More than 8 m |

| Public Transportation | More than 400 m away | At least 1 mode, within 400 m | More than 2 modes, both within 300 m | |

| Parking Capacity | Parking lot non-compliant with standard | Parking lot exceeding standards, paid | Parking lot exceeding standards, free | |

| I | Affiliate Facilities | None | 1 facility | 2 or more facilities |

| Large Institutions | None | Present | Present with cooperation or linkage programs | |

| Tourism Attractions | None | 1 attraction within 1 km | 2 or more attractions within 1 km | |

| C | Barrier-Free Facilities | Absent | 1 to 3 facilities | 4 or more facilities |

| Amenities | Absent | 1 to 3 facilities | 4 or more facilities | |

| Landscape | Below legal standards | Meets legal standards | 20% or more landscaping area | |

| P | Buddhist Retreats | None | 1 program | 2 or more programs |

| Community Events | None | At least once a year | At least once every quarter | |

| Promotional Channels | None | Utilizing 2 or more channels | Utilizing 2 or more channels, with two languages | |

| Barrier-Free Design Evaluation Items |

|---|

|

| Amenity Evaluation Items |

|---|

|

| Name | Location | Land Area (m2) | Total Floor Area (m2) | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cheongnyangsa | Dongdaemun | 7893 | 2536.49 | 1895 |

| Myogaksa | Jongno | 1174.80 | 1395.04 | 1942 |

| Heungcheonsa | Seongbuk | 45,061.00 | 2518.57 | 1397 |

| Bomunsa | Seongbuk | 28,913.00 | 6705.87 | 1115 |

| Gaeunsa | Seongbuk | 16,717.00 | 4424.80 | 1730 |

| Jogyesa | Jongno | 16,022.80 | 13,487.88 | 1938 |

| Bongeunsa | Gangnam | 75,636.00 | 12,360.26 | 794 |

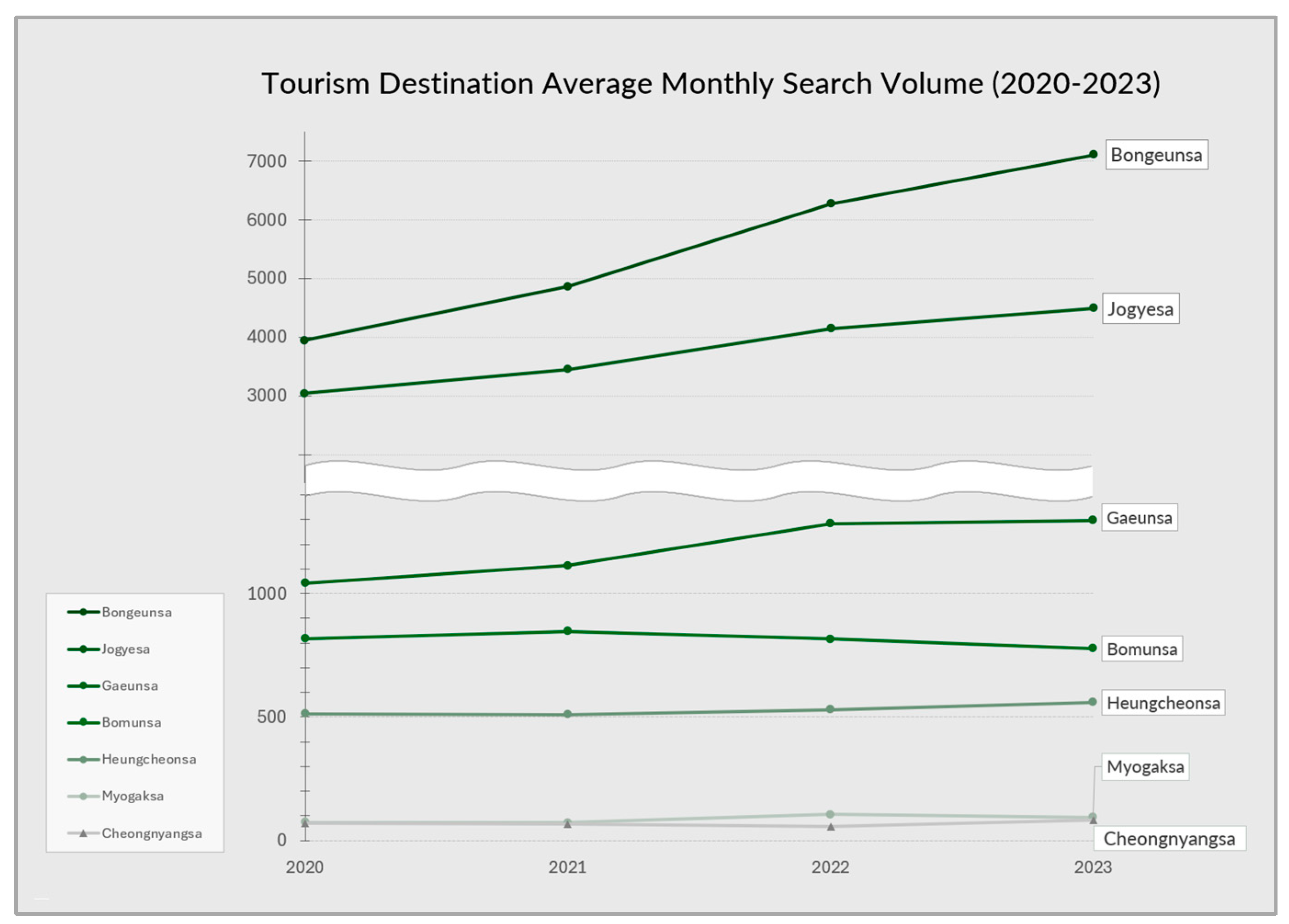

| Name | Bongeunsa | Jogyesa | Gaeunsa | Bomunsa | Heungcheonsa | Myogaksa | Cheongnyangsa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | ||||||||

| 2020 | 3950 | 3041 | 1043 | 812.75 | 514 | 74 | 69 | |

| 2021 | 4863 | 3452 | 1114 | 862.08 | 510 | 73 | 67 | |

| 2022 | 6277 | 4149 | 1284 | 825.00 | 530 | 106 | 57 | |

| 2023 | 7114 | 4495 | 1298 | 802.67 | 560 | 93 | 83 | |

| Average of 4 years | 5551 | 3784 | 1185 | 815 | 529 | 87 | 69 | |

| Temple | Bongeun-sa | Jogyesa | Gaeunsa | Bomunsa | Heungcheon-sa | Myogak-sa | Cheongnyang-sa | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attribute and Factor | Sco. | Sum | Sco | Sum | Sco | Sum | Sco | Sum | Sco | Sum | Sco | Sum | Sco | Sum | |

| H | Y. of Const. | 2 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Trad. Comp. | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||

| Cult. Herit. | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||

| A | W. of Roads | 2 | 6 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 3 |

| Pub. Transp. | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | ||||||||

| Park. Cap. | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||

| I | Affil. Facils. | 2 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Large Insts. | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||

| Tour. Attracs. | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | ||||||||

| C | BF Facils. | 2 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Amenities | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||

| Landscaping | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | ||||||||

| P | Buddh. Retrs. | 2 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| Comm. Events | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| P. Channel | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||

| Total | 25 | 20 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 9 | 6 | ||||||||

| Temple | Gaeunsa | Bomunsa | Heungcheonsa | Myogaksa | Cheongnyangsa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | ||||||

| Y. of Const. | 0.189 | −0.811 | 0.189 | 0.189 | 0.189 | |

| Trad. Comp. | 2.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 2.000 | 2.000 | |

| Cult. Herit. | −0.405 | −0.405 | −1.405 | 0.595 | 0.595 | |

| W. of Roads | −0.405 | −0.405 | 0.595 | 0.595 | −0.405 | |

| Pub. Transp. | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | |

| Park. Cap. | 0.595 | 1.595 | −0.405 | 1.595 | 1.595 | |

| Affil. Facils. | 2.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 2.000 | |

| Large Insts. | −1.405 | 0.595 | 0.595 | 0.595 | 0.595 | |

| Tour. Attracs. | 1.405 | 1.405 | 1.405 | −0.595 | 1.405 | |

| BF Facils. | 2.000 | 2.000 | 0.000 | 2.000 | 2.000 | |

| Amenities | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | |

| Landscaping | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 2.000 | 1.000 | |

| Buddh. Retrs. | 1.000 | 1.000 | 2.000 | 1.000 | 2.000 | |

| Comm. Events | 0.595 | 0.595 | 0.595 | 0.595 | 0.595 | |

| P. Channel | 0.405 | 0.405 | 0.405 | 1.405 | 1.405 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, S.; Lee, J.; Kim, Y. Evaluation of Urban Traditional Temples Using Cultural Tourism Potential. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6375. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16156375

Kim S, Lee J, Kim Y. Evaluation of Urban Traditional Temples Using Cultural Tourism Potential. Sustainability. 2024; 16(15):6375. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16156375

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Sio, Jaeseong Lee, and Youngsuk Kim. 2024. "Evaluation of Urban Traditional Temples Using Cultural Tourism Potential" Sustainability 16, no. 15: 6375. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16156375

APA StyleKim, S., Lee, J., & Kim, Y. (2024). Evaluation of Urban Traditional Temples Using Cultural Tourism Potential. Sustainability, 16(15), 6375. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16156375