Abstract

This study assesses the impact of a sustainability-focused residential hall in Hong Kong on the environmental awareness and adoption of sustainable practices of its student residents. The hall provides an immersive learning environment, offering hands-on activities such as eco-gardening, sustainability drives, seminars, and workshops to impart sustainability knowledge and skills. Utilizing a mixed-methods approach, this study gathered quantitative data through a questionnaire on environmental beliefs and pro-environmental intention, revealing a significant enhancement in environmental awareness among students with more than two semesters of residence in the hall. Qualitative research explored the impact of residential hall experiences on the residents’ environmental mindset, uncovering three themes: immersive experiences, long-term habituation, and the visibility of outcomes. These findings suggest that living in a sustainability-themed residential hall shapes students’ environmental attitudes and behaviors, reinforcing the value of integrating residential education within Environmental Sustainability Education (ESE) frameworks. This study highlights the potential of residential halls or communities as catalysts for fostering a culture of sustainability within academic communities, offering insights for educators and policy-makers in designing effective ESE strategies.

1. Introduction

Environmental and sustainability education shapes the attitudes and actions of university students, equipping them with essential knowledge, skills, and values for informed decision-making and responsible behavior toward maintaining environmental integrity, ensuring economic viability, and fostering a just society for both present and future generations [1,2,3]. This education prepares them to address contemporary environmental challenges and promote sustainable living practices [4].

Cultivating environmental consciousness and fostering sustainable practices in university students is a critical endeavor for modern education [5]. Innovative educational frameworks such as project-based learning, community engagement initiatives, and practical environmental activities enable students to gain environmental insight through experiential learning and hone their problem-solving skills [6]. This approach goes beyond conventional classroom instruction, melding theoretical insights with real-world applications to motivate student engagement in addressing environmental challenges [7]. Through this immersive learning journey, students come to recognize the significance and impact of their contributions, bolstering their commitment to environmental stewardship. Adopting such educational strategies is a key part of guiding society toward a more sustainable and environmentally conscious future.

Cultivating pro-environmental attitudes in university students is crucial, considering their future roles as stewards, planners, policymakers, and educators in the realm of environmental sustainability. At this pivotal stage of their lives, university students are particularly receptive to learning about environmental issues. The university environment provides an ideal setting for the exploration, discussion, and promotion of positive environmental behaviors, which can extend their influence beyond the campus and into the wider community.

This paper explores residential education as a strategic approach to Environmental Sustainability Education (ESE), underscoring its effectiveness in molding eco-conscious behaviors and attitudes among university students. Through this lens, the study provides an example of how living–learning environments can integrate sustainability into the fabric of everyday student life, thereby fostering a generation deeply committed to environmental stewardship.

2. Background and Context

2.1. Environmental and Sustainability Education in Hong Kong

The international metropolis of Hong Kong is known for its dense urban landscape, but surprisingly, about 75% of its 1108 square kilometers are rural countryside, boasting an exceptionally rich biodiversity [8]. Recognizing the importance of instilling environmental consciousness from an early age, the Environmental Protection Department, in collaboration with the Education Bureau of Hong Kong, has created educational programs tailored for students across various age groups. These initiatives are grounded in the philosophy of nurturing eco-awareness right from the outset.

Schools in Hong Kong have embraced a diverse array of school-based curricula in response to this environmental education mandate. These range from incorporating topics such as “sustainable development in eco-tourism” into general knowledge classes to engaging students in hands-on activities like cultivating organic plants in available school spaces. Other innovative approaches include integrating the theme of “building an eco-friendly city” into the broader curriculum and focusing on “sustainable education” for comprehensive learning experiences [9]. These endeavors aim to foster students’ interest in environmental stewardship and motivate them to undertake proactive measures toward environmental improvement. Furthermore, influenced by the Biophilic City movement in densely populated Singapore [10], Hong Kong is similarly embracing these principles. The city is adopting strategies to weave nature into the fabric of urban life, enhancing sustainability and improving the quality of life for its residents. This shift towards integrating green spaces and ecological practices is progressively reflected in Hong Kong’s environmental education initiatives [11].

In Hong Kong, environmental and sustainability education has been increasingly integrated into higher education, as seen with the establishment of the Hong Kong Sustainable Campus Consortium (HKSCC) by eight University Grant Committee-funded universities. The consortium represents a collaborative effort to achieve sustainable development goals and create positive social impact [12]. Moreover, specific educational programs such as the Master of Arts in Education for Sustainability at the Education University of Hong Kong aim to promulgate subject knowledge and innovative pedagogical practices in sustainability, attracting a diverse group of students and professionals [13].

Educational strategies have also been designed to address environmental challenges such as municipal solid waste (MSW). Studies indicate that environmental knowledge can improve public support for environment-related activities and that nature-rich environmental education can foster pro-environmental behavior [14]. These endeavors are indicative of a broader movement within Hong Kong’s educational sector to integrate sustainable principles and consciousness across all echelons, from strategic policy formulation to curriculum design, promoting a comprehensive sustainability ethos.

2.2. Residential Education as a Pedagogy for ESE

Residential halls at universities are extensions of the traditional academic environment, providing a holistic setting that cultivates not only academic knowledge but also essential life skills such as communication, self-reliance, critical thinking, and an appreciation for diverse viewpoints [15]. The experiences gained within these communal living spaces enrich students’ social and personal growth, fostering a sense of community and mutual respect.

The University of Hong Kong, accommodating a substantial segment of its student population with 1800 beds in residential colleges as of June 2023, effectively addresses the challenges of high living costs and a competitive housing market in the city [16]. The university’s residential culture is rooted in engaging students in active hall life, underscored by re-admission policies that promote participation in a wide array of hall-centric activities [15].

Thematic engagements within the University of Hong Kong’s residential halls are strategically designed to complement ESE objectives. For example, community service projects often involve sustainability efforts such as waste reduction campaigns, green space enhancement, and energy conservation initiatives, allowing students to apply ESE principles to real-world contexts. Similarly, discussions and activities centered around religious education themes can foster a deeper ethical contemplation about human–nature relationships, encouraging sustainable living practices. These experiences, facilitated within the unique communal setting of the residential halls, provide an immersive learning environment where sustainability concepts are not only taught but lived, embodying the essence of residential education as a dynamic pedagogical framework for ESE.

2.3. Description of Study Area

This study focuses on New College at the University of Hong Kong, which is strategically positioned in Kennedy Town on the coast. With a deep-rooted commitment to environmental protection and sustainability, New College is known for eco-conscious education. It offers an immersive learning environment where students are encouraged to actively engage in sustainable living practices through a variety of well-designed activities and discussion forums, fostering respect and care for the natural world. These sustainability initiatives, based on research and consideration of the local context, form the cornerstone of New College’s educational ethos, seamlessly integrating environmental stewardship into the daily lives of the residential community. The college’s warden, a professor from HKU’s environmental department, plays a pivotal role in guiding these efforts.

2.3.1. Welcome Event at Mai Po Nature Reserve

The welcome event for new residents begins with an orientation at the Mai Po Nature Reserve, a site of global ecological significance in the northwest New Territories. Recognized as a Ramsar Site, Mai Po is a critical habitat for aquatic birds and a key stopover for migratory species along the East Asia Australasia Flyway. Each season, it becomes a sanctuary for many rare and endangered birds. The residence hall uses this event as an introduction to environmental awareness, offering students an impactful first experience with the program.

2.3.2. Eco-Farming Team

Just steps from New College, the Eco-Farming Team has transformed an adjacent plot into a biodiversity garden, cultivating more than 40 types of fruits and vegetables. This initiative not only enhances local biodiversity with native flora but also educates team members on sustainable farming techniques, utilizing organic compost made from the college’s kitchen waste.

2.3.3. Sustainability Drive

To instill eco-friendly living habits within the college, the Sustainability Drive encourages the community to minimize waste by selling and repurposing unwanted items during student transitions. The initiative not only reduces waste but also funds further sustainable projects through the proceeds, reinforcing a cycle of environmental responsibility.

2.3.4. Seminar and Nature Appreciation

To deepen understanding of local conservation issues, New College organizes seminars and field trips that merge theoretical knowledge with practical exploration. These include indoor lectures coupled with field excursions to significant ecological sites such as Long Valley, a crucial wetland for Hong Kong’s biodiversity. Additionally, activities such as coastal clean-ups and tours of recycling facilities offer students tangible experiences of environmental stewardship, underscoring the importance of integrating sustainable practices with biodiversity conservation.

Through these curated programs, New College not only educates but also empowers its students to become active participants in the global sustainability movement, equipped with the knowledge and experience to make a meaningful impact.

As shown in Figure 1, New College’s residential hall is situated in Kennedy Town near the coastline, with convenient access to the abundant natural resources of the surrounding hills. The green spaces around indicate areas for environmental study and leisure, emphasizing the college’s connection to both urban and natural environments. The hall frequently organizes clean-up activities for students along the beaches and hiking trails, contributing to the cleanliness and environmental stewardship of the entire Kennedy Town area. The student village in Kennedy Town consists of four residence halls. Admission to New College is random, which ensures that students with a prior interest in environmental topics are not specifically chosen to reside there.

Figure 1.

Location of New College. Source: © Google Map.

3. Theoretical Frameworks

This study is situated at the intersection of Residential Education and ESE, drawing on a range of theoretical perspectives to explore the pedagogical potential of university residential halls in fostering sustainability consciousness among students. Central to our exploration is the concept of Community-Based Learning, which posits that learning occurs within a social context and is enhanced by community engagement [17]. This theory supports our examination of residential halls as dynamic learning environments where students engage with peers, participate in sustainability initiatives, and develop communal values toward environmental stewardship. In the current literature, residential halls are recognized not only as living spaces for students but also as pivotal environments for developing social interactions and identity, thus influencing students’ university experiences [18]. Building on this idea, we explored the significance of the residential hall experience and its impact on students’ environmental ideologies. We also drew on Social Learning Theory [19], which emphasizes the role of social interaction in learning and the adoption of sustainable behaviors. Additionally, we considered how the Community of Practice framework could be applied to examine how residential hall-based shared learning fosters a collective understanding and implementation of sustainability practices [20]. This framework is instrumental in understanding how residential educational experiences might shape students’ attitudes toward sustainability and their propensity to engage in pro-environmental behaviors.

By integrating these theoretical perspectives, our study aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of how residential education can serve as an effective pedagogical framework for ESE, potentially transforming students’ environmental awareness and behaviors.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Design

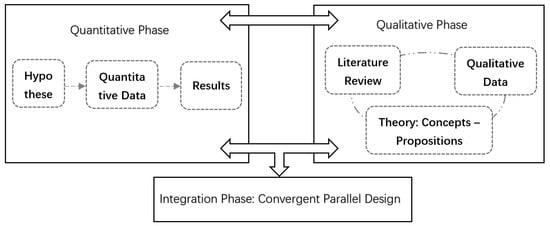

The study employed a convergent parallel design, where both quantitative and qualitative elements were conducted simultaneously during the same phase of the research process [21]. Informed by a comprehensive review of the existing literature, the design of the quantitative surveys and the focus of the qualitative interviews were carefully structured to explore different facets of students’ environmental beliefs and behaviors. This iterative approach ensured that the insights from the literature review were integrated into every stage of the research, shaping both the development of survey questions and the thematic focus of the interviews. Quantitative data were subjected to statistical analysis to identify significant patterns and relationships, while qualitative data were analyzed thematically to extract key themes and narratives. Findings from one method were used to refine and focus the other in real time, ensuring that our approach adapted to emerging insights. For example, preliminary quantitative results highlighting particular areas of interest or concern were followed up with targeted questions in subsequent qualitative interviews to deepen our understanding of those specific issues. This dynamic interaction between the two methods provided a broad overview from the quantitative data and added depth and context from the qualitative portion, enhancing the robustness and comprehensiveness of our conclusions.

A questionnaire anchored the quantitative analysis, providing a structured measure of students’ environmental beliefs and pro-environmental behavioral intentions. Qualitative insights were derived from in-depth interviews, allowing participants to express their experiences and perceptions as well as the details of their eco-friendly actions at New College. The quantitative research addressed the question of whether residential hall experiences affect students’ sense of sustainability; the qualitative research sought to elucidate how residential hall experiences influence students’ sense of sustainability.

To bolster the scientific validity of our mixed-methods design, we employed triangulation as a fundamental strategy. This involves the integration of findings from both the questionnaire and interviews to solidify and deepen our understanding of student environmental behaviors. Through the juxtaposition of quantitative metrics and qualitative narratives, we aim to authenticate our results across diverse data sources, enhancing the reliability and comprehensiveness of our conclusions (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Mixed-methods study design.

4.2. Instrumentation

4.2.1. Environmental Beliefs and Pro-Environmental Intention Questionnaire

The questionnaire was made up of three sections, comprising 15 items total: environmental beliefs (5 items), pro-environmental behaviors (5 items), and demographic information (3 items) (see Figure A1). Respondents rated their agreement on a 7-point Likert scale, from “totally disagree (1)” to “totally agree (7)”.

The scales utilized in the questionnaire were grounded in prior research and exhibited high reliability and validity. As English is the working language of universities in Hong Kong, there was no need to translate the items. The environmental beliefs scale was adapted from Dunlap [22], and the pro-environmental behavioral intention scale was adopted from Mateer [23], originally comprising 27 items (e.g., “Cut down on heating or air conditioning to limit energy use”; “Composted food or yard and garden refuse”.) The Pro-Environmental Behavior Scale (PEBS) was initially developed by primarily conducting research with college students as participants [23,24]. Similarly, the respondents in our study are also students, which underscores the scale’s direct relevance and proven applicability to this demographic group.

Given that students residing in the hall participated in compulsory environmental activities overlapping with the original scale’s items, this study focused on measuring behavioral intentions rather than actual behaviors. For example, one adapted item was, for the upcoming 2024–2025 academic year: “I would like to reuse shopping bags”.

Consultations with environmental experts from Hong Kong universities resulted in the selection of five items from the ‘Pro-environmental Intention’ dimension of the Pro-Environmental Behavior Scale (PEBS), identified as most suitable for the local context. Selection criteria were rigorously applied to ensure that items were relevant to Hong Kong, as pro-environmental behavior is significantly influenced by cultural and contextual factors. For instance, considerations such as the absence of bicycle lanes, minimal car usage, limited private yard space, and the high cost of vegetables making organic options less accessible were crucial in selecting contextually appropriate scale items. According to researchers like Deltomme [25], validating an existing pro-environmental behavior scale for the specific study context is essential to ensure all items accurately reflect local environmental engagement.

To mitigate social desirability bias—where respondents may answer in a manner that conforms more closely to socially accepted norms, particularly when addressing socially sensitive constructs—this study employed anonymous, self-administered surveys [26]. Before distributing the survey, participants were assured that their responses would remain confidential and used solely for research purposes. This approach was intended to encourage honest responses. Additionally, electronic questionnaires were used [27], and the item wording was carefully neutral to minimize the influence of social desirability bias on the results.

A pilot test conducted on 30 September 2022 in the dormitory resulted in 46 valid questionnaires. Feedback indicated that the questions were specifically and clearly worded, requiring no adjustments.

Table 1 illustrates the reliability and validity of the constructs ‘Environmental Beliefs’ and ‘Pro-environmental Intentions’ within our study. It provides the Standardized Factor Loadings, Cronbach’s α, Composite Reliability (CR), and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) for each item within these constructs. Cronbach’s α assesses internal consistency, where values above 0.7 typically indicate good reliability, suggesting that the items within each latent variable are closely related. Composite Reliability further evaluates the consistency of these constructs, with values also above 0.7 reflecting acceptable reliability. The AVE measures the amount of variance that a construct captures from the variables it is presumed to measure versus the variance due to measurement error, with values above 0.5 deemed adequate. The ‘Environmental Beliefs’ construct, for example, displays a Cronbach’s α of 0.852, CR of 0.881, and an AVE of 0.521, indicating robust measurement properties and affirming that each construct demonstrates good internal consistency and convergent validity, thereby meeting the rigorous standards required for research reliability.

Table 1.

Item wording and reliability values of the scale.

4.2.2. Semi-Structured Interview

Semi-structured interviews based on environmental awareness were used to better understand and interpret students’ perspectives. Semi-structured interviews, facilitated by open-ended questions, allow participants to express their perceptions in their own words [28]. Participants were asked to elaborate on their residential experience and involvement in hall activities either in English or Cantonese, with each interview lasting around 20 min.

Questions included probes to enrich the data and deepen articulation of participants’ views. Depending on the flow of the conversation, follow-up questions sought further clarification, asked for examples, or probed specific details. To fully capture their experiences, participants were also asked “why” and “how” questions to enhance the data quality.

The interview comprised four open-ended questions: (1) What environmental activities have you participated in at the hall? (2) Could you describe any changes in your environmental awareness before and after moving into New College? (3) Were there specific events or activities that contributed to these changes? (4) During your time in the hall, have you made any adjustments to your daily habits to be more environmentally friendly? How did these adjustments gradually develop? We asked additional questions based on the positions and responses of the interviewees.

4.3. Data Collection and Analysis

4.3.1. Participants and Procedures

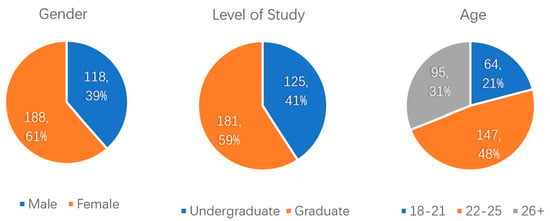

Figure A1 shows a summary of the demographic characteristics of the 306 students who participated in the study, with a gender ratio of 61% female to 39% male. This distribution aligns with the gender composition of the residential halls involved in the study, ensuring that our sample accurately reflects the population of our specific research environment.

The questionnaires were created using Google Forms and the link was distributed to participants who had lived in the dormitory for over two years via WhatsApp, as each dormitory floor has its own dedicated WhatsApp group with all students included. The dormitory building renews its resident list and admits new students every summer. Consequently, we conducted a pre-test in September 2022, with 317 participants completing the questionnaire. In June 2023, we conducted a post-test with the same group and obtained 306 valid responses.

The custom at universities in Hong Kong is that monthly high-table dinners are mandatory, ensuring broad access to dormitory residents and enhancing sample representation. Originating from a formal meal tradition in the dining rooms of British colleges, high-table dinners are reserved for the residential master, fellows, and their distinguished guests—a tradition that began at Oxford and Cambridge and has since spread to many colleges and universities in Hong Kong [15] (The term “ high-table dinners “ originally refers to a formal meal in the dining room of a British college, reserved for the residential master, fellows, and their distinguished guests. This tradition, which began at Oxford and Cambridge, has since spread to many colleges and universities in Hong Kong [15]). These two-hour dinners, held from March to June 2023, provided ample time for our interviews. Conducting interviews in such a relaxed dining environment allowed students to express their views more naturally. During the dinners, we randomly selected interviewees to avoid bias. The eligibility of participants was verified by first asking how long they had been living in the hall, ensuring that they had resided there for over two semesters. Conducting face-to-face interviews at the event also allowed us to observe non-verbal cues, providing a better understanding of the participants’ genuine thoughts. Each interview lasted around 15 min. In selecting participants for the semi-structured interviews, we also considered gender and ethnicity to ensure diversity, including individuals of Indian, Caucasian, and local Hong Kong backgrounds, based on appearance. In total, we interviewed 32 students (see Table A1). After each interview, the data were translated and transcribed for further analysis.

4.3.2. Analysis

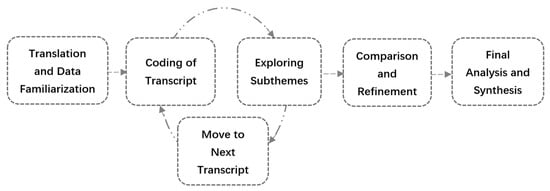

The qualitative data from the interviews were analyzed using NVivo 12. All of the interview recordings were transcribed and translated into English if they were in Cantonese. Two independent coders who were fluent in both Chinese and English analyzed the data using a thematic analytical approach [29]. The two transcribers read and reread the interview transcripts to increase their familiarity with the data and to identify general themes. They independently coded the transcripts manually, identified key themes, and categorized them by research question. Representative quotations of each theme and category were also highlighted during this process. Coding was the fundamental process whereby the concepts or phenomena were named and were subsumed under the major categories. This process of data analysis involved constant comparisons between the categories [30]. Both of the transcribers continually coded and categorized the information until notable categories called “core categories” emerged and no further categories or subcategories were expected to emerge. The coding notes and summaries were exchanged between the coders to allow them to discuss differences and similarities. Through this continuing comparison, key themes that answered the research questions were identified, with representative quotations from the participants. The transcribed data were analyzed using the constant comparative method [31]. In other words, the data were collected and examined simultaneously as trends, themes, and patterns in the data were ascertained (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Data analysis process.

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Quantitative Research: Do Residential Hall Experiences Affect Residents’ Attitudes toward Sustainability?

The analysis of pre-test and post-test results demonstrates that both environmental beliefs and pro-environmental behavioral intentions among participants improved significantly over the course of the study (refer to Table 2). This statistical analysis confirms the effectiveness of the educational program implemented during the study. Notably, the increase in students’ scores on environmental beliefs before and after seminars and other activities in the hall suggests that these events positively influenced students’ environmental ideologies. It is likely that during outings to wetlands, students experienced the vulnerability of natural environments, further reinforcing their awareness and commitment to environmental issues.

Table 2.

Paired samples t-test and Cohen’s d effect size of the pre- and post-test results (N = 306).

The observed changes in mean scores and reduced variability indicate impact on participants’ attitudes and behaviors concerning environmental sustainability. This pattern suggests that sustainability programs within residential halls are essential to shaping students’ environmental practices, not just supplementary experiences.

These effect sizes highlight the practical significance of the educational and experiential interventions provided in the residential halls. They provide empirical support that the observed changes are not only statistically significant but also meaningful in terms of real-world implications. This strengthens the argument that targeted educational programs within residential settings can profoundly impact students’ environmental attitudes and behaviors.

5.2. Qualitative Research: How do Residential Hall Experiences Affect Residents’ Attitudes toward Sustainability?

Comments related to this main theme were grouped into three subthemes: immersive experiences, long-term habituation, and the visibility of outcomes (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Thematic coding framework (N = 32).

5.2.1. Immersive Experiences

Participants expressed that engaging in environmental activities at the dorm immersed them in an eco-friendly environment beyond theoretical knowledge. Working in the eco-garden and attending sustainability workshops deepened their understanding and passion for environmental conservation. One student noted, for example, “Working in the eco-garden allowed me to physically engage with the soil and plants, an experience that goes far beyond the theoretical knowledge learned in classrooms”. (S9) “Living here, surrounded by green initiatives and eco-conscious peers, has been like a continuous, hands-on workshop in sustainability. Every day offers a new lesson in living harmoniously with our environment”. (S31)

Additionally, participants were profoundly impacted by field trips to places like the Hong Kong wetlands: “Our dorm’s initiative to conduct nature explorations in nearby natural reserves brought the textbook concepts of biodiversity and ecosystems to life for me. These experiences have not just educated me but have emotionally connected me with the cause of environmental preservation”. (S12)

5.2.2. Long-Term Habituation

Living in the sustainability-themed dorm for about one year led participants to unconsciously adopt more eco-friendly practices in their daily lives. Recycling, conserving energy, and opting for greener choices became routine habits. Participation in environmental projects transformed their lifestyles, extending sustainability practices beyond campus and even influencing choices during visits home, illustrating the lasting influence of residential education.

“Over time, I‘ve realized that participating in the dorm’s environmental projects is not just a one-off activity; they have actually transformed my lifestyle. Now, even outside campus, I instinctively opt for greener choices”.(S4)

“I didn’t realize the impact of our dorm until I found myself automatically segregating waste and reducing plastic use, even when visiting my family during holidays”.(S31)

“I‘ve noticed myself unconsciously adopting more eco-friendly practices in my daily life. Because of the posters in the dorm, I now always think about using reusable shopping bags instead of disposable plastic ones, and sometimes I actually do it”.(S17)

Moreover, students reported that they became more attentive to and engaged with environmental topics, comparing the information they saw in dorm activities with public campaigns such as those seen on the Hong Kong metro.

5.2.3. The Visibility of Outcomes

Participants expressed pride in witnessing tangible outcomes of their collective efforts such as environmental improvements in the whole neighborhood. Projects like food composting demonstrated how small actions can yield significant environmental impacts, fostering a sense of achievement and motivation to continue environmental endeavors. The communal garden’s flourishing as a result of collective composting efforts served as a tangible reminder of the hall’s potential to effect positive change. Visible outcomes, including reduced energy bills and waste generation, validated the effectiveness of collective green initiatives, fostering communal pride and responsibility.

Some students noted that while they had previously encountered environmental initiatives, seeing concrete results in a localized community context, such as cleaning the Kennedy Town waterfront, made the impact more visible and meaningful: “Seeing the amount of waste we reduced at the end of the semester was incredible. It’s rewarding to see the actual results of our recycling efforts”. (S23) “Our work has made the coastline more attractive”. (S15)

Visible environmental achievements can foster a sense of pride and cohesion within a community. When community members see actual, positive results from their environmental efforts, such evidence supports the success of these initiatives. Witnessing the fruits of collective efforts not only strengthens community bonds but also serves as tangible evidence of the success of such strategies, encouraging further collaborative actions toward sustainability. Observing the positive outcomes of sustainable practices can inspire individuals to adopt more eco-friendly behaviors in their daily lives, thereby creating a norm within the community that values and prioritizes environmental stewardship.

6. Discussions

This study, examining ESE within a sustainability-focused residential hall in Hong Kong, highlights the unique value and efficacy of immersive, community-based learning environments for promoting environmental awareness and sustainable practices. University residential halls, known for their role in fostering social networks [32], provide fertile ground for students to learn from each other’s eco-friendly habits through peer influence and the reinforcement of social norms [33,34]. Living among like-minded individuals who prioritize sustainability enhances learning through social interaction, creating a network that encourages the sharing of ideas and best practices.

This communal setting allows for continuous, hands-on engagement and motivates students toward sustainable behaviors more effectively than traditional classroom-based learning alone. Translating environmental knowledge into action is inherently challenging [35]; knowledge alone is often insufficient to drive behavioral change [36]. Rather, emotional engagement is crucial [37]. The immersive experiences, long-term habituation, and visible outcomes observed in this study created an emotional resonance, reinforcing students’ commitment to environmental stewardship.

Research emphasizes that effective ESE should focus on emotional and action-oriented outcomes and recommends prioritizing locally relevant topics and harnessing unique learner environments [38]. The residential hall approach aligns perfectly with these recommendations. By offering a comprehensive, immersive, and practical learning environment, the two-year residency program provides an innovative ESE model that fosters long-term behavioral change, encourages community engagement, and leverages visible outcomes to reinforce sustainable practices. This serves as a powerful framework for future ESE strategies.

Moreover, the visibility of sustainability outcomes highlighted in this study aligns with the principles of Social Learning Theory, emphasizing the importance of observable and reinforced models of behavior. The significant role of visible outcomes in motivating students supports the idea that when individuals see the tangible results of their actions, they are more likely to continue engaging in pro-environmental behaviors. This highlights the need for educational programs to integrate feedback mechanisms that allow students to see the immediate impact of their actions, thereby enhancing the learning and behavior modification process.

To significantly enhance the efficacy of ESE, educational institutions should consider expanding interactive learning opportunities and fostering deeper community engagement. Interactive learning can be promoted through the integration of practical, hands-on sustainability activities within the educational curriculum such as recycling workshops, eco-gardening, and local environmental clean-ups. These activities not only enrich the students’ learning experience by applying theoretical knowledge in real-world contexts but also help in embedding sustainable habits. Additionally, fostering community engagement by encouraging student participation in local environmental projects can enhance their understanding of real-world sustainability challenges and foster a stronger sense of community responsibility. Such engagement can be facilitated through partnerships with local environmental organizations, which can offer students practical experiences that complement their academic learning. The community-driven models used in residential halls can be adapted and replicated in other areas such as corporate settings, high schools, and neighborhoods. These models work well in contexts that feature long-term and community-oriented characteristics, leveraging extended engagement and peer influence to cultivate sustainable practices.

This study underscores the importance of emotions and beliefs in nurturing eco-friendly attitudes [37]. The findings offer educators and policymakers valuable insights into creating impactful ESE strategies and suggest that integrating ESE within residential halls can act as a catalyst, fostering a sustainability culture within academic communities.

7. Conclusions

By integrating Community-Based Learning Theory and Social Learning Theory, our findings provide an understanding of how sustainable behaviors are not only learned but can also become embedded in students’ daily lives. The observed immersive experiences, long-term habituation, and visibility of outcomes collectively illustrate that residential halls act as social learning environments where sustainable practices are both observed and performed.

This study supports and extends the theory of Community-Based Learning by demonstrating that sustainability education is most effective when it is contextually embedded within the student’s living environment. The practical engagement with sustainability initiatives allows for an experiential learning process that deepens the student’s commitment and understanding, transforming theoretical knowledge into actionable behavior. These findings suggest that educational frameworks should incorporate more experiential and community-focused elements to foster deeper ecological literacy and behavior change.

This study acknowledges certain limitations that may influence the interpretation and generalizability of the results. Primarily, the voluntary nature of participation in this research could have created a self-selection bias, as individuals who chose to participate likely already possessed a heightened environmental consciousness. This predisposition could have skewed the results, potentially overestimating the impact of the residential hall on fostering sustainable behaviors. Additionally, because this study is based on self-reported surveys, the level of action considered may not accurately reflect the actual action levels.

Future research could benefit from adopting a longitudinal approach, tracking students’ environmental behaviors and commitments after graduation. Such studies would provide insights into the long-term efficacy of educational interventions provided in residential settings and their adaptability across diverse geographical and cultural landscapes. This would help in understanding the sustained impact of immersive educational experiences on environmental actions in varied contexts.

In conclusion, this paper underscores the significance of introducing young university students to innovative environmental education methods through a series of sustainability-focused activities and educational events within a residential setting. By embedding environmental consciousness into the daily lives and communal experiences of students, this approach aims to cultivate a deeper, more practical understanding of sustainability practices, thereby equipping the next generation with the knowledge and skills necessary to make environmentally responsible decisions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.L. (Xunqian Liu) and Y.Y.; methodology, X.L. (Xunqian Liu); software, X.L. (Xiaoqing Liu); writing—review and editing, X.L. (Xunqian Liu). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to ethical approval of HKU.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Demographics of study participants (N = 306).

Table A1.

Demographics of study participants (N = 32).

Table A1.

Demographics of study participants (N = 32).

| Demographics | Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 16 | 50% |

| Female | 16 | 50% | |

| Major | STEM | 13 | 40.6% |

| Non-STEM | 19 | 59.4% | |

| Level of Study | Undergraduate | 22 | 68.8% |

| Graduate | 10 | 31.2% | |

| Age | 18–21 | 13 | 40.6% |

| 22–25 | 16 | 50% | |

| 26+ | 3 | 9.4% | |

| Ethnicity | Local Hong Kong | 13 | 40.6% |

| Other Asia | 10 | 31.2% | |

| India | 5 | 15.6% | |

| Caucasian | 4 | 21.5% | |

References

- Ajaps, S. Deconstructing the constraints of justice-based environmental sustainability in higher education. Teach. High. Educ. 2023, 28, 1024–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pache, A.; Glaudel, A.; Partoune, C. Editorial: Environmental and sustainability education in compulsory education: Challenges and practices in Francophone Europe. Environ. Educ. Res. 2023, 29, 1043–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kioupi, V.; Voulvoulis, N. Education for Sustainable Development: A Systemic Framework for Connecting the SDGs to Educational Outcomes. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niesenbaum, R.A.; Gorka, B. Community-Based Eco-Education: Sound Ecology and Effective Education. J. Environ. Educ. 2001, 33, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotz-Sisitka, H.; Rosenberg, E.; Ramsarup, P. Environment and sustainability education research as policy engagement: (re-) invigorating ‘politics as potentia’ in South Africa. Environ. Educ. Res. 2021, 27, 525–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casinader, N. What Makes Environmental and Sustainability Education Transformative: A Re-Appraisal of the Conceptual Parameters. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Y.W. Developing youth toward pluralistic environmental citizenship: A Taiwanese place-based curriculum case study. Environ. Educ. Res. 2023, 29, 121–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GovHK. An Overview on Nature Conservation and Countryside Conservation in Hong Kong. 2023. Available online: https://www.eeb.gov.hk/sc/conservation/conservation_maincontent.html (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- Environmental Protection Department. Environmental Education & Awareness in Hong Kong. 2023. Available online: https://www.epd.gov.hk/epd/tc_chi/envir_education/enviredu_aware/overview.html (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- Newman, P. Biophilic urbanism: A case study on Singapore. Aust. Plan. 2013, 51, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, C. Earth.org. Biophilia Design and Biophilic Cities: Can Hong Kong Become One? 2022. Available online: https://earth.org/biophilia-design-biophilic-cities-hong-kong/ (accessed on 1 July 2024).

- Xiong, W.; Mok, K.H. Sustainability Practices of Higher Education Institutions in Hong Kong: A Case Study of a Sustainable Campus Consortium. Sustainability 2020, 12, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EdUHK. Master of Arts in Education for Sustainability. 2023. Available online: https://maefs.eduhk.hk/ (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- Cheng, C.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, L. Sustainable Environmental Management Through a Municipal Solid Waste Charging Scheme: A Hong Kong Perspective. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 919683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, E.; Chu, S.; Chau, A.; Chung, R. The Impact of Relationships with Hall Mates, Tutors, and Wardens on the Residence Hall Experience in Hong Kong. High. Educ. Q. 2020, 47, 35–48. [Google Scholar]

- Accommodation at the University of Hong Kong. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Accommodation_at_the_University_of_Hong_Kong (accessed on 2 July 2024).

- O’Connor, A. Beyond the Four Walls: Community-Based Learning and Languages. Lang. Learn. J. 2012, 40, 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paine, D.E. An Exploration of Three Residence Hall Types and the Academic and Social Integration of First Year Students. Master’s Thesis, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Akers, R.L. Social Learning Theory. In Explaining Criminals and Crime: Essays in Contemporary Criminological Theory; Paternoster, R., Bachman, R., Eds.; Roxbury: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2001; pp. 192–210. [Google Scholar]

- Anil, B.; Tonts, M.; Siddique, K.H.M. Strengthening the performance of farming system groups: Perspectives from a Communities of Practice framework application. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2015, 22, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Educational Research: Planning, Conducting, and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Research; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap, R.E.; Van Liere, K.D.; Mertig, A.G.; Jones, R.E. New trends in measuring environmental attitudes: Measuring endorsement of the new ecological paradigm: A revised NEP scale. J. Soc. Issuess 2000, 56, 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateer, T.J.; Melton, T.N.; Miller, Z.D.; Lawhon, B.; Agans, J.P.; Taff, B.D. A Multi-Dimensional Measure of Pro-Environmental Behavior for Use Across Populations with Varying Levels of Environmental Involvement in the United States. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0274083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markle, G.L. Pro-Environmental Behavior: Does It Matter How It’s Measured? Development and Validation of the Pro-Environmental Behavior Scale (PEBS). Hum. Ecol. 2013, 41, 905–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deltomme, B.; Gorissen, K.; Weijters, B. Measuring Pro-Environmental Behavior: Convergent Validity, Internal Consistency, and Respondent Experience of Existing Instruments. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodou, D.; de Winter, J.C. Social desirability is the same in offline, online, and paper surveys: A meta-analysis. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 36, 487–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, L.R.; Usher, L.E.; Chapmon, T. Surfers as environmental stewards: Understanding place-protecting behavior at Cape Hatteras National Seashore. Leis. Sci. 2018, 40, 442–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeşilyurt, M.; Özdemir Balakoğlu, M.; Erol, M. The Impact of Environmental Education Activities on Primary School Students’ Environmental Awareness and Visual Expressions. Qual. Res. Educ. 2020, 9, 188–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, I. Using Quantitative Data in Mixed-Design Grounded Theory Studies: An Enhanced Path to Formal Grounded Theory in Information Systems. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2015, 24, 531–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B.; Strauss, A. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Sociology Press: Mill Valley, CA, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, S. Social networks, social capital, social support and academic success in higher education: A systematic review with a special focus on ‘underrepresented’ students. Educ. Res. Rev. 2020, 29, 100307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.W.; Chan, C.K. Do university residential experiences contribute to holistic education? J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 2020, 42, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanada, M.; Norman, P.; Kaida, N.; Carver, S. Linking environmental knowledge, attitude, and behavior with place: A case study for strategic environmental education planning in Saint Lucia. Environ. Educ. Res. 2023, 29, 929–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the Gap: Why Do People Act Environmentally and What Are the Barriers to Pro-Environmental Behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmi, N.; Arnon, S.; Orion, N. Transforming environmental knowledge into behavior: The mediating role of environmental emotions. J. Environ. Educ. 2015, 46, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasimov, N.; Malkhazova, S.; Romanova, E. The Role of Environmental Education for Sustainable Development in Russian Universities. Planet 2002, 8, 24–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, S.; Watted, S.; Zion, M. Contribution of an intergenerational sustainability leadership project to the development of students’ environmental literacy. Environ. Educ. Res. 2021, 27, 1723–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).