Airbnb and Mountain Tourism Destinations: Evidence from an Inner Area in the Italian Alps

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. P2P Platforms

2.2. Airbnb

3. Materials and Methods

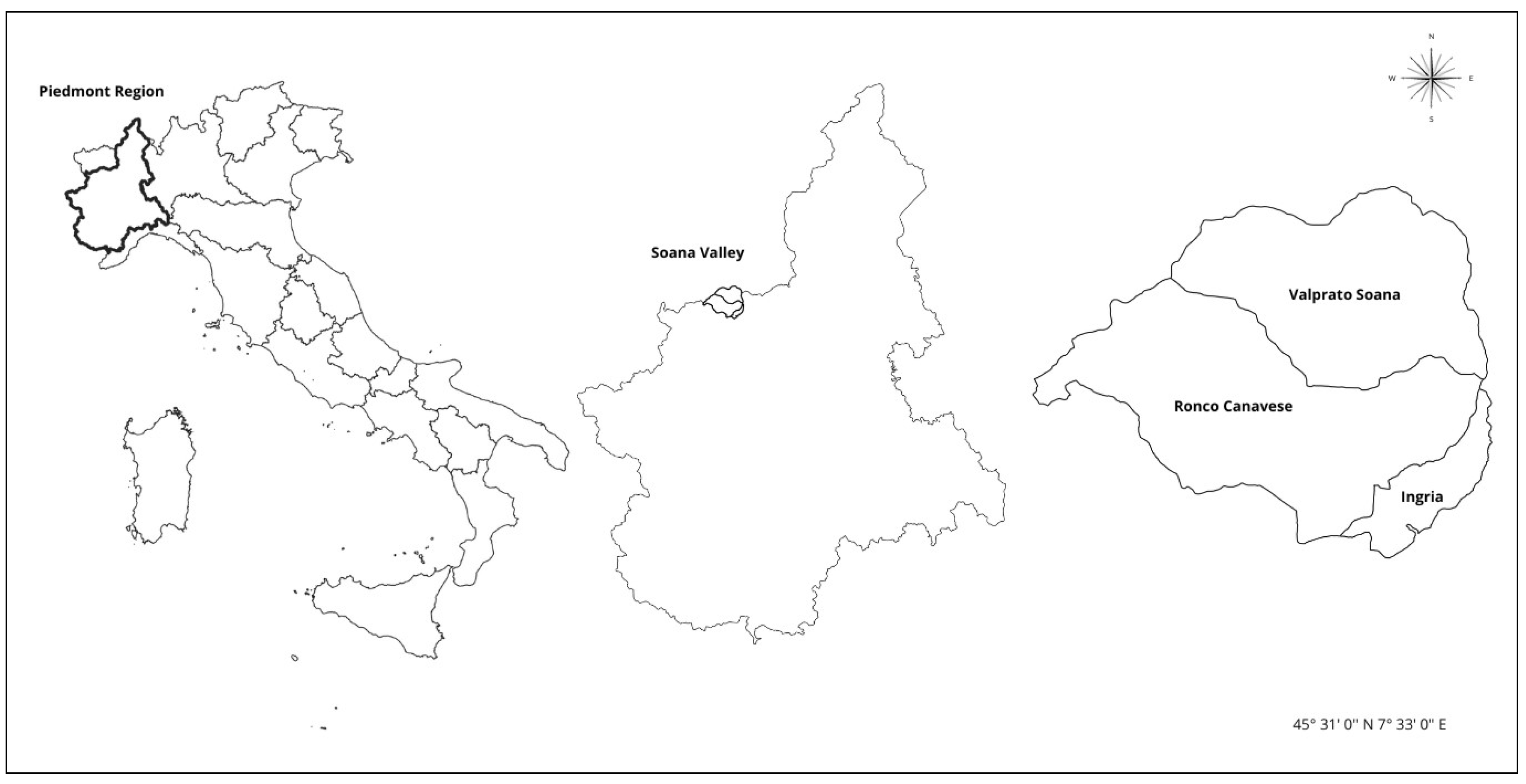

3.1. The Area of Investigation

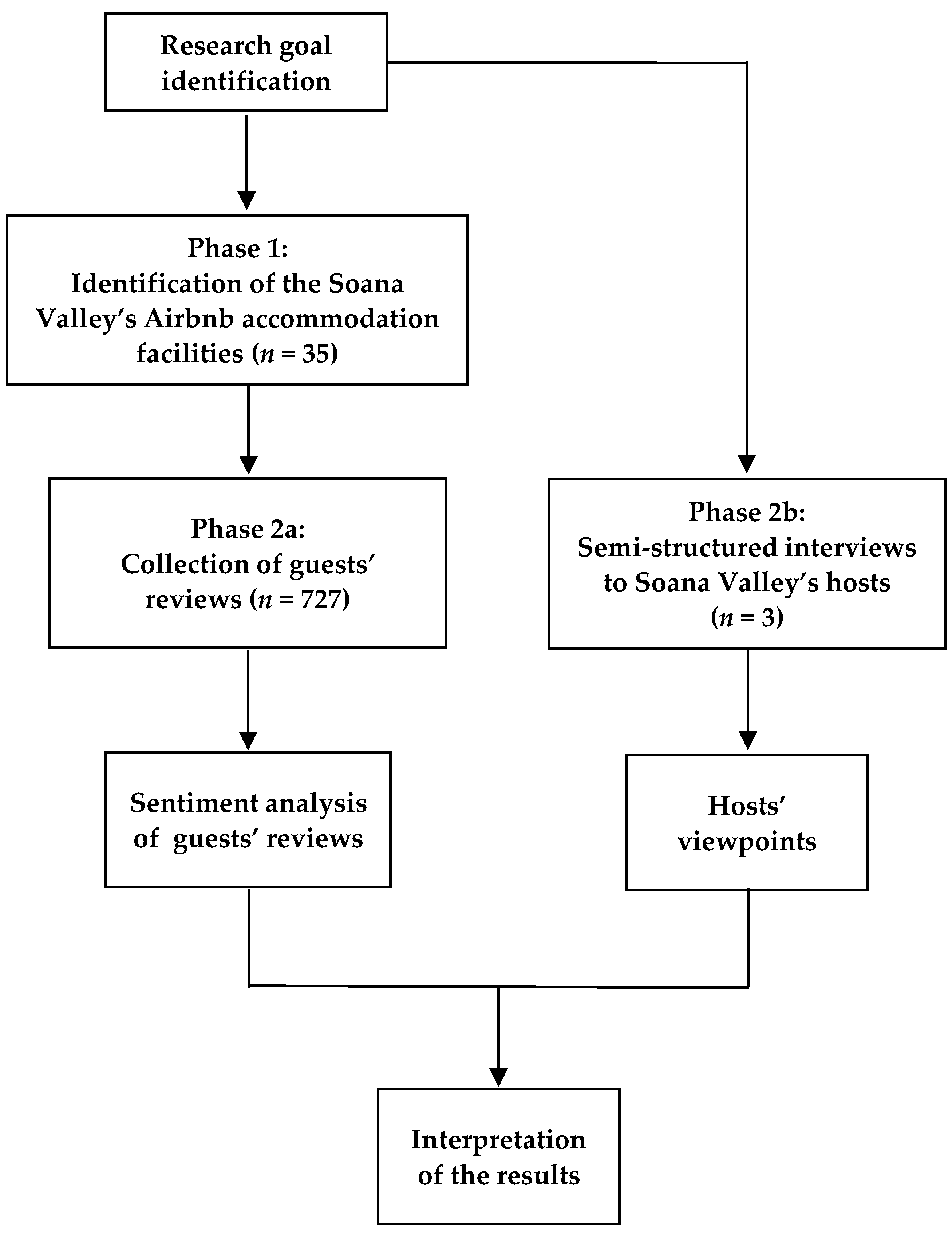

3.2. Methodology

- Location—We decided to involve one host for each municipality. Even if the valley was relatively small compared to other mountainous areas, the three municipalities had some differences and specific characteristics. Valprato Soana was the starting point for all the most interesting hiking purposes, while Ronco Canavese was the commercial hub of the valley with all the retailer activities. Ingria was the first village of the valley and, in the meantime, the only municipality with no land in the national park.

- Number of comments—For each municipality, we selected the Airbnb with the higher number of comments.

- In-the-field experience—The number of operational years was the third criterion.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Airbnb in Soana Valley

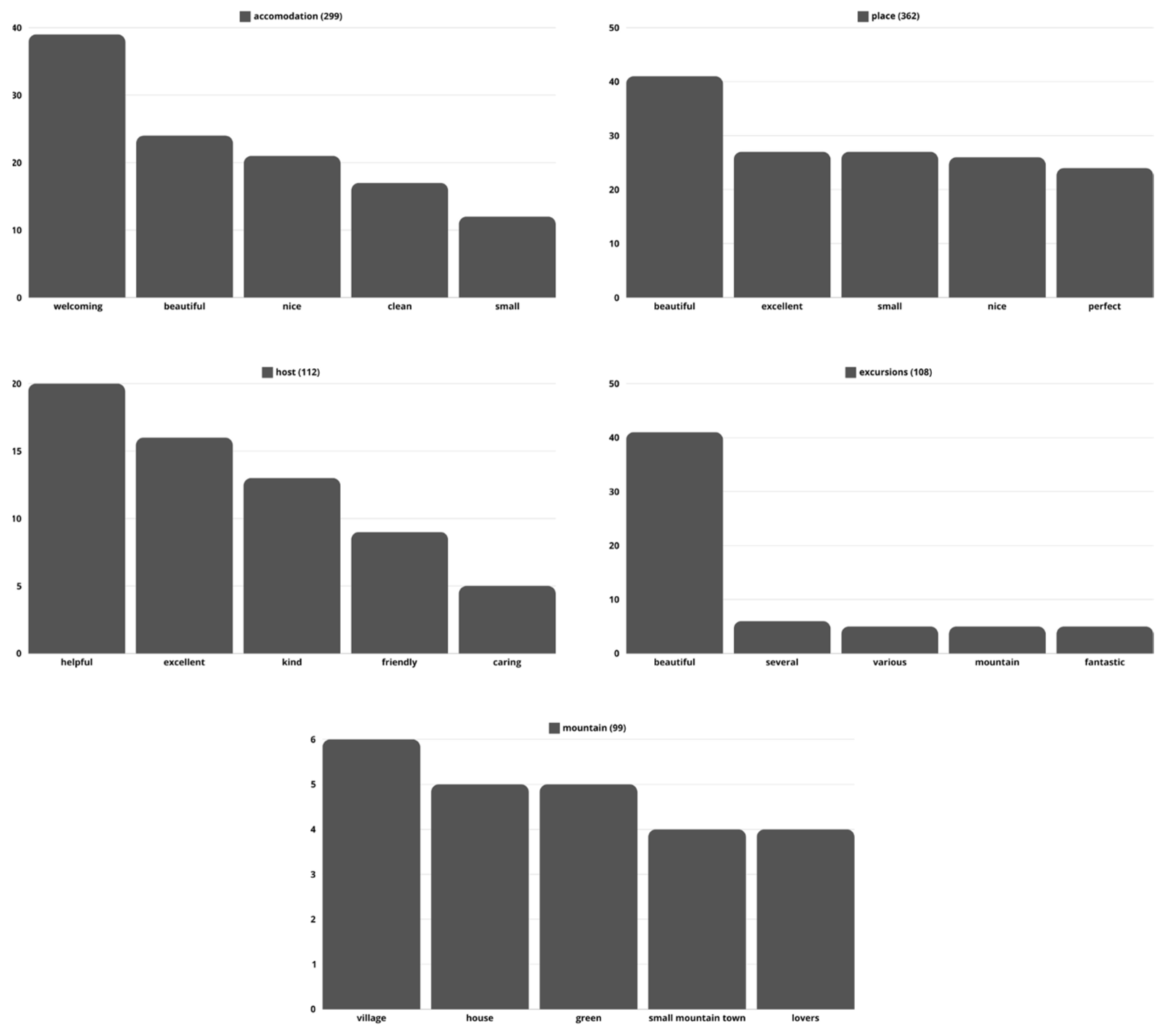

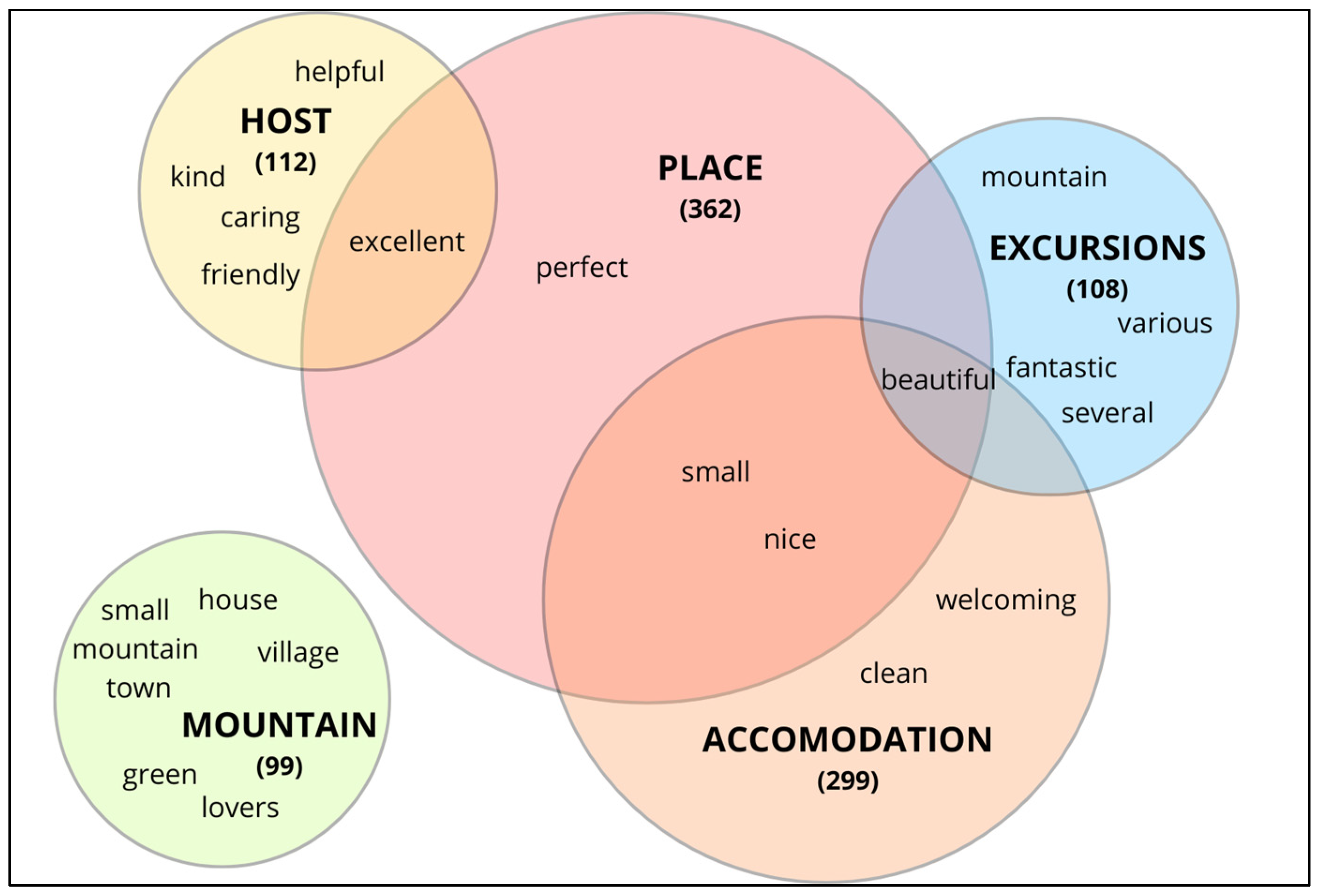

4.2. Tourists’ Feelings and Impressions

“Comfortable apartment in the center of the village, close to all the necessary services and an excellent starting point for trekking in the beautiful Soana Valley. […] was very kind and helpful and also welcomed our two big dogs with pleasure. Ideal place to immerse yourself in the mountains!”

“The well-equipped and cozy apartment is located in an (almost) uninhabited village. The only sounds that can be heard are the ringing of cowbells, birdsong and the rushing stream—wonderful! There is a pub opposite the apartment that is probably open every day, but it was very quiet there during my vacation. [...] Beautiful and difficult hikes of varying lengths are possible right from the front door. [...] [Host name]’s apartment is a very good place for peace and active nature experience in the mountains!”

“For nature lovers, the small house offered by [Host name], completely renovated, is ideally located in the Grand Paradiso National Park. Near a river you will find peace and serenity with sometimes the possibility of meeting a fox, a shepherd with his flock, beautiful different colors at all times of the day. I recommend this property.”

4.3. The Host’s Viewpoints

“All the guests who come here, they come precisely because they do like the valley.”(Host 1)

“There’s nothing here except from nature. Uncontaminated nature.”(Host 2)

“Many come because they know that the Gran Paradiso National Park is there.”(Host 1)

“They come here because they know the Gran Paradiso National Park. They don’t care if they go to Cogne or here, because they don’t know the roads, they just not that it’s inside the park and that there’s wilderness.”(Host 3)

“Airbnb is important because of that. When you’re looking for an apartment in the mountains, you look for the National Park and then you just pick something in the area. We don’t have fancy facilities, but we show pictures of our beautiful landscape, and we have fair prices.”

“That’s the point of Airbnb. You’re not going to stay in a hotel, you’re going in someone’s house. I love chatting with people and tell them about my valley.”(Host 2)

“At first the local community wasn’t 100% convinced about Airbnb. They were a bit reluctant to new people. Now the relationship with Airbnb tourists is much better than with the ones who stays in hotels. Through Airbnb you become part of the community, you know the people who actually live here.”(Host 3)

5. Conclusions

5.1. Implications

5.1.1. Theoretical Implications

5.1.2. Policy Implications

5.1.3. Managerial Implications

5.2. Limitations and Future Research Agenda

- The direct involvement of the guests with devoted questionnaires for having a better understanding of their expectations and the role of the cultural heritage in their Airbnb experience is warranted. Moreover, this analysis may help in understanding whether there are statistically significant differences depending on provenience [60].

- A direct involvement of other local stakeholders, as policymakers, traditional accommodation facilities’ managers, retailers, and food producers is also warranted, in order to achieve a more complete vision of the role of peer-to-peer accommodation facilities on the area.

- A comparison with other similar mountainous areas is finally warranted for assessing if the results could be generalized for all the marginal mountain tourism destinations.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- In which year was the Airbnb opened?

- How many people can be hosted by the facility?

- How was the structure used before converting it to Airbnb?

- Is facility management your main occupation/main source of income?

- How many facilities do you manage?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of your accommodation?

- What are the most demanded/most criticized aspects of your accommodation?

- What kind of tourism do you offer?

- In your opinion, what are the strengths and weaknesses of Soana Valley from the tourists’ point of view?

References

- Daglis, T. Sharing Economy. Encyclopedia 2022, 2, 1322–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjbari, M.; Morales-Alonso, G.; Carrasco-Gallego, R. Conceptualizing the Sharing Economy through Presenting a Comprehensive Framework. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharing Economy Noun—Definition, Pictures, Pronunciation and Usage Notes|Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary at OxfordLearnersDictionaries.Com. Available online: https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/definition/english/sharing-economy (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Belarmino, A.; Koh, Y. A Critical Review of Research Regarding Peer-to-Peer Accommodations. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 84, 102315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhzady, S.; Olya, H.; Farmaki, A.; Ertaş, Ç. Sharing Economy in Hospitality and Tourism: A Review and the Future Pathways. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2021, 30, 549–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- About Us. Airbnb Newsroom. Available online: https://news.airbnb.com/about-us/ (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Garay-Tamajón, L.A.; Morales-Pérez, S. ‘Belong Anywhere’: Focusing on Authenticity and the Role of Airbnb in the Projected Destination Image. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2023, 25, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miguel, C.; Martos-Carrión, E.; Santa, M. A Conceptualisation of the Sharing Economy: Towards Theoretical Meaningfulness. In The Sharing Economy in Europe: Developments, Practices, and Contradictions; Česnuitytė, V., Klimczuk, A., Miguel, C., Avram, G., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 21–40. ISBN 978-3-030-86897-0. [Google Scholar]

- Domènech, A.; Zoğal, V. Geographical Dimensions of Airbnb in Mountain Areas: The Case of Andorra. J. Rural. Stud. 2020, 79, 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omarini, E.A. Peer-to-Peer Lending: Business Model Analysis and the Platform Dilemma. Int. J. Financ. Econ. Trade 2018, 2, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqayed, Y.; Foroudi, P.; Kooli, K.; Foroudi, M.M.; Dennis, C. Enhancing Value Co-Creation Behaviour in Digital Peer-to-Peer Platforms: An Integrated Approach. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 102, 103140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamiak, C.; Szyda, B.; Dubownik, A.; García-Álvarez, D. Airbnb Offer in Spain—Spatial Analysis of the Pattern and Determinants of Its Distribution. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2019, 8, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guttentag, D. Progress on Airbnb: A Literature Review. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2019, 10, 814–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenken, K.; Schor, J. Putting the Sharing Economy into Perspective. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2017, 23, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oskam, J.A. The Future of Airbnb and the ‘Sharing Economy’: The Collaborative Consumption of Our Cities. In The Future of Airbnb and the ‘Sharing Economy’; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2019; ISBN 978-1-84541-674-4. [Google Scholar]

- DiNatale, S.; Lewis, R.; Parker, R. Short-Term Rentals in Small Cities in Oregon: Impacts and Regulations. Land Use Policy 2018, 79, 407–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurran, N.; Phibbs, P. When Tourists Move In: How Should Urban Planners Respond to Airbnb? J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2017, 83, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamiak, C. Mapping Airbnb Supply in European Cities. Ann. Tour. Res. 2018, 71, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negi, G.; Tripathi, S. Airbnb Phenomenon: A Review of Literature and Future Research Directions. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2022, 6, 1909–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short-Stay Accommodation Offered via Online Collaborative Economy Platforms. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Short-stay_accommodation_offered_via_online_collaborative_economy_platforms (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Adamiak, C. Current State and Development of Airbnb Accommodation Offer in 167 Countries. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 25, 3131–3149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griswold, A. This New Year’s, Airbnb Got the Hockey-Stick Growth That Every Startup Envies. Available online: https://qz.com/877080/airbnbs-growth-in-guests-on-new-years-is-the-hockey-stick-curve-that-every-startup-wants (accessed on 8 April 2024).

- Guttentag, D. Airbnb: Disruptive Innovation and the Rise of an Informal Tourism Accommodation Sector. Curr. Issues Tour. 2015, 18, 1192–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanli, N.; Small, J.; Darcy, S. The Representation of Airbnb in Newspapers: A Critical Discourse Analysis. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 25, 3186–3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dann, D.; Teubner, T.; Weinhardt, C. Poster Child and Guinea Pig—Insights from a Structured Literature Review on Airbnb. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 31, 427–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, R. Authenticity for Rent? Airbnb Hosts and the Commodification of Urban Displacement. Proc. ACM Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2022, 6, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belotti, S. “Sharing” Tourism as an Opportunity for Territorial Regeneration: The Case of Iseo Lake, Italy. Hung. Geogr. Bull. 2019, 68, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güçlü, B.; Roche, D.; Marimon, F. City Characteristics That Attract Airbnb Travellers: Evidence from Europe. Int. J. Qual. Res. 2020, 14, 271–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, J.; García-Palomares, J.C.; Romanillos, G.; Salas-Olmedo, M.H. The Eruption of Airbnb in Tourist Cities: Comparing Spatial Patterns of Hotels and Peer-to-Peer Accommodation in Barcelona. Tour. Manag. 2017, 62, 278–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quattrone, G.; Proserpio, D.; Quercia, D.; Capra, L.; Musolesi, M. Who Benefits from the “Sharing” Economy of Airbnb? In Proceedings of the WWW ’16: Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on World Wide Web, Montreal, QC, Canada, 11–15 May 2016; pp. 1385–1393. [Google Scholar]

- Roelofsen, M. Exploring the Socio-Spatial Inequalities of Airbnb in Sofia, Bulgaria. Erdkunde 2018, 72, 313–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strommen-Bakhtiar, A.; Vinogradov, E. The Adoption and Development of Airbnb Services in Norway: A Regional Perspective. In Destination Management and Marketing: Breakthroughs in Research and Practice; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 32–44. ISBN 978-1-79982-469-5. [Google Scholar]

- Eugenio-Martin, J.L.; Cazorla-Artiles, J.M.; González-Martel, C. On the Determinants of Airbnb Location and Its Spatial Distribution. Tour. Econ. 2019, 25, 1224–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contu, G.; Conversano, C.; Frigau, L.; Mola, F. The Impact of Airbnb on Hidden and Sustainable Tourism: The Case of Italy. Int. J. Tour. Policy 2019, 9, 99–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crescimanno, A.; Ferlaino, F.; Rota, F. StrumentIRES. Marginalità Dei Piccoli Comuni Del Piemonte 2008; Iris Piemonte: Piemonte, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Duglio, S.; Bonadonna, A.; Letey, M.; Peira, G.; Zavattaro, L.; Lombardi, G. Tourism Development in Inner Mountain Areas—The Local Stakeholders’ Point of View through a Mixed Method Approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duglio, S.; Bonadonna, A.; Letey, M. The Contribution of Local Food Products in Fostering Tourism for Marginal Mountain Areas: An Exploratory Study on Northwestern Italian Alps. Mt. Res. Dev. 2022, 42, R1–R10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltramo, R.; Bonadonna, A.; Duglio, S.; Peira, G.; Vesce, E. Local Food Heritage in a Mountain Tourism Destination: Evidence from the Alagna Walser Green Paradise Project. Br. Food J. 2023, 126, 309–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duglio, S.; Letey, M. The Role of a National Park in Classifying Mountain Tourism Destinations: An Exploratory Study of the Italian Western Alps. J. Mt. Sci. 2019, 16, 1675–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandara, H.M.A.P.; Charles, J.; Lekamge, L.S. Using Sentiment Analysis to Explore the Accommodation Experience in the Sharing Economy through Topic Modeling. In Proceedings of the 2022 4th International Conference on Advancements in Computing (ICAC), Colombo, Sri Lanka, 9–10 December 2022; pp. 156–161. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, L.; Lin, Y.; Cheng, M. Sentiment and Guest Satisfaction with Peer-to-Peer Accommodation: When Are Online Ratings More Trustworthy? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 86, 102369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Teotia, Y.; Singh, T.; Bhardwaj, P. COVID-19 Pandemic: A Sentiment and Emotional Analysis of Modified Cancellation Policy of Airbnb. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Computing Informatics and Networks; Abraham, A., Castillo, O., Virmani, D., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 633–644. [Google Scholar]

- Saura, J.R.; Palos-Sanchez, P.; Rios Martin, M.A. Attitudes Expressed in Online Comments about Environmental Factors in the Tourism Sector: An Exploratory Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, F.M.; Khan, S.A.; Shamim, K.; Gupta, Y.; Sherwani, S.I. Analysing Customers’ Reviews and Ratings for Online Food Deliveries: A Text Mining Approach. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2023, 47, 953–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes Pereira Santos, A.I.; Costa Perinotto, A.R.; Renner Rodrigues Soares, J.; Savi Mondo, T. Feeling at Home while Traveling: An Analysis of the Experiences of Airbnb Users. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 28, 167–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmberg, J.; Lundqvist, U.; Robèrt, K.-H.; Wackernagel, M. The Ecological Footprint from a Systems Perspective of Sustainability. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 1999, 6, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halog, A. Models for Evaluating Energy, Environmental and Sustainability Performance of Biofuels Value Chain. Int. J. Glob. Energy Issues 2009, 32, 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senthil, V.; Goswami, S. An Exploratory Study of Twitter Sentiment Analysis During COVID-19: #TravelTomorrow and #UNWTO. In Re-Imagining Diffusion and Adoption of Information Technology and Systems: A Continuing Conversation; Sharma, S.K., Dwivedi, Y.K., Metri, B., Rana, N.P., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 487–498. [Google Scholar]

- Mondal, S.; Samaddar, K. Future of Sharing Economy and Its Resilience Post Pandemic: A Study on Indian Travel and Tourism Industry. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2022, 33, 1591–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surugiu, C.; Surugiu, M.-R.; Grădinaru, C. Targeting Creativity Through Sentiment Analysis: A Survey on Bucharest City Tourism. SAGE Open 2023, 13, 21582440231167346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voicu, M.-C.; Babonea, A.-M. Using the Snowball Method in Marketing Research on Hidden Populations. Chall. Knowl. Soc. 2011, 1, 1341–1351. [Google Scholar]

- Duglio, S.; Salotti, G.; Mascadri, G. Conditions for Operating in Marginal Mountain Areas: The Local Farmer’s Perspective. Societies 2023, 13, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilińska, K.; Pabian, B.; Pabian, A.; Reformat, B. Development Trends and Potential in the Field of Virtual Tourism after the COVID-19 Pandemic: Generation Z Example. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Mengoni, P. What Do Airbnb Users Care About Before, During and After the COVID-19? An Analysis of Online Reviews. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/WIC International Conference on Web Intelligence and Intelligent Agent Technology (WI-IAT), Venice, Italy, 26–29 October 2023; pp. 409–414. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.; Cheng, M.; Wang, Y. What Makes People Recommend Airbnb Online Experiences: The Moderating Effect of Host. Curr. Issues Tour. 2023, 27, 2250–2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munasinghe, L.M.; Gunawardhana, T.; Wickramaarachchi, N.C.; Ariyawansa, R.G. Peer-to-Peer Accommodation User Experience: Evidence from Sri Lanka. SAGE Open 2023, 13, 21582440231199324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Ayllon, S. Urban Transformations as an Indicator of Unsustainability in the P2P Mass Tourism Phenomenon: The Airbnb Case in Spain through Three Case Studies. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grisdale, S. Displacement by Disruption: Short-Term Rentals and the Political Economy of “Belonging Anywhere” in Toronto. Urban Geogr. 2021, 42, 654–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smigiel, C. Touristification, Rent Gap and the Local Political Economy of Airbnb in Salzburg (Austria). Urban Geogr. 2024, 45, 713–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, R.W.; Mok, C.; Go, F.M.; Chan, A. The Importance of Cross-Cultural Expectations in the Measurement of Service Quality Perceptions in the Hotel Industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 1997, 16, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Municipality | No. of Airbnbs | Total Beds | Average Beds | No. of Comments | Average Rating out of 5 | % Star-Rated Answers per Municipality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ingria | 2 | 8 | 4 | 171 | 4.91 | 100 |

| Ronco C.se | 16 | 58 | 3.625 | 189 | 4.751 | 56.3 |

| Valprato Soana | 17 | 74 | 4.353 | 371 | 4.547 | 64.7 |

| Total/Average | 35 | 140 | 4 | 731 | 4.736 | 73.7 |

| Word | Count | Italian Guests | Foreign Guests |

|---|---|---|---|

| beautiful | 237 | 120 | 117 |

| excellent | 203 | 113 | 90 |

| welcoming | 157 | 105 | 51 |

| clean | 156 | 113 | 43 |

| village | 141 | 58 | 83 |

| perfect | 131 | 73 | 58 |

| well | 128 | 87 | 40 |

| kind | 123 | 97 | 26 |

| nice | 120 | 63 | 57 |

| helpful | 119 | 94 | 25 |

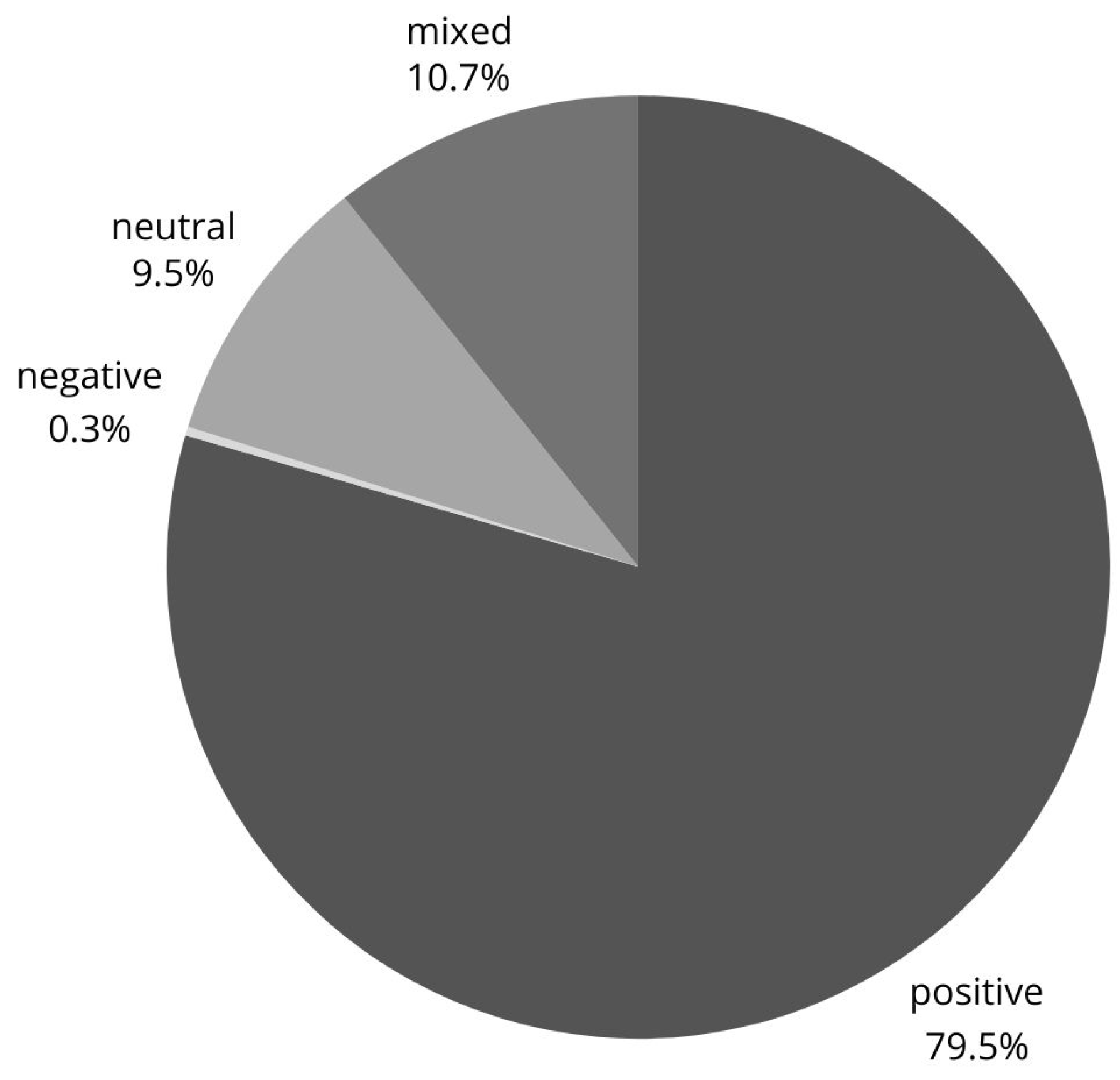

| Sentiment Analysis | Count | % |

|---|---|---|

| positive | 578 | 79.5% |

| negative | 2 | 0.3% |

| neutral | 69 | 9.5% |

| mixed | 78 | 10.7% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Duglio, S.; Mascadri, G.; Salotti, G. Airbnb and Mountain Tourism Destinations: Evidence from an Inner Area in the Italian Alps. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5593. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16135593

Duglio S, Mascadri G, Salotti G. Airbnb and Mountain Tourism Destinations: Evidence from an Inner Area in the Italian Alps. Sustainability. 2024; 16(13):5593. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16135593

Chicago/Turabian StyleDuglio, Stefano, Giulia Mascadri, and Giulia Salotti. 2024. "Airbnb and Mountain Tourism Destinations: Evidence from an Inner Area in the Italian Alps" Sustainability 16, no. 13: 5593. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16135593

APA StyleDuglio, S., Mascadri, G., & Salotti, G. (2024). Airbnb and Mountain Tourism Destinations: Evidence from an Inner Area in the Italian Alps. Sustainability, 16(13), 5593. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16135593