The current research focuses on the success of entrepreneurial firms since they are more dynamic and willing to make risky decisions [

19]. The success of entrepreneurs has gained significant attention from researchers; however, the success of entrepreneurial firms is hardly addressed, even though it is highly linked with the performance of entrepreneurial firms [

20]. Success and performance are two similar contexts, but the difference is that in the achievement of aims and goals, the mission of the entrepreneurial firm determines the success of the firm, and, if it is achieved, the firm is supposed to be successful. As the entrepreneurial firm is created by identifying the gap in the market, therefore, the aim of the firm is to fulfill that gap; hence, the success of the entrepreneurial firm is highly dependent on the alertness of the entrepreneur [

21]. Entrepreneurial alertness serves as a valuable resource for businesses [

22]. Entrepreneurial alertness necessitates activities that may result in a competitive advantage for entrepreneurial firms [

23].

Thus, entrepreneurial attentiveness is a valuable and scarce resource among competitors. Therefore, the Resource-based View (RBV) validates the assertions made in this study that entrepreneurial awareness, as a competitive resource, can assist entrepreneurial enterprises achieve superior success. The RBV provides justification for any kind of resource that is variable, rare, imitable nonreplaceable [

15]. Furthermore, to reinforce the theoretical foundations, resource dependency theory has been utilized. Resource dependency theory was introduced by Pfeffer and Salancik (1978) [

24]. According to RDT, for the success of the organization, external support is required [

25].

The literature on the association between entrepreneurial awareness and the success of entrepreneurial firms is inconclusive and inconsistent [

1,

2,

17]. Some believe it increases profitability [

2,

6], while others argue that it is simply a cost for small businesses because of experimentation and will end up in losses [

4,

8]. Furthermore, researchers in the field of entrepreneurship discuss and highlight the importance of open innovation, which is based on the market input; similarly, Portuguez-Castro identified the same for co-creation in entrepreneurship by conducting a systematic review in which the author reviewed 53 scientific articles and also identified the same concept [

20].

In addition to that, Portuguez Castro, Scheede, and Zermeño, who conducted their research using the Delphi method on 26 participants, identified the similar skills of entrepreneurs that have been analyzed in the current research [

26]. The authors concluded that perseverance and attitude to achieve objectives, which can be reflected in linking the dots toward the achievements of goals, along with the ability to identify opportunities and motivation, which is reflected in scanning and evaluating opportunities, are those critical constructs that are studied and evaluated over empirical data.

2.1. Entrepreneurial Alertness and Success of Entrepreneurial Firms

According to earlier studies on entrepreneurial alertness, people who are alert can spot opportunities before others can [

2]. The kind of dealings that are entered in upcoming market cycles may be influenced by alertness [

5]. Scholarly research has long maintained that the ability to process information [

30], identify patterns in the environment [

31], process past knowledge and experiences [

12], and social participation [

32] are components of alertness.

Alert entrepreneurs are uniquely equipped and ready to spot an opportunity before their peers [

3]. As a result, a clear understanding of how entrepreneurial alertness affects entrepreneurial enterprises’ success has been severely constrained. Senior entrepreneurs are more likely to make fresh discoveries and expand their businesses’ inventions [

33]. Nonetheless, an entrepreneur’s possession of a resource (alertness) may not guarantee the success of their firm. Its impact on success will probably depend on how well an entrepreneur can seize an opportunity before others do [

22].

Researchers have studied the idea of entrepreneurs’ attentiveness and its possible effects in the entrepreneurship literature [

34].

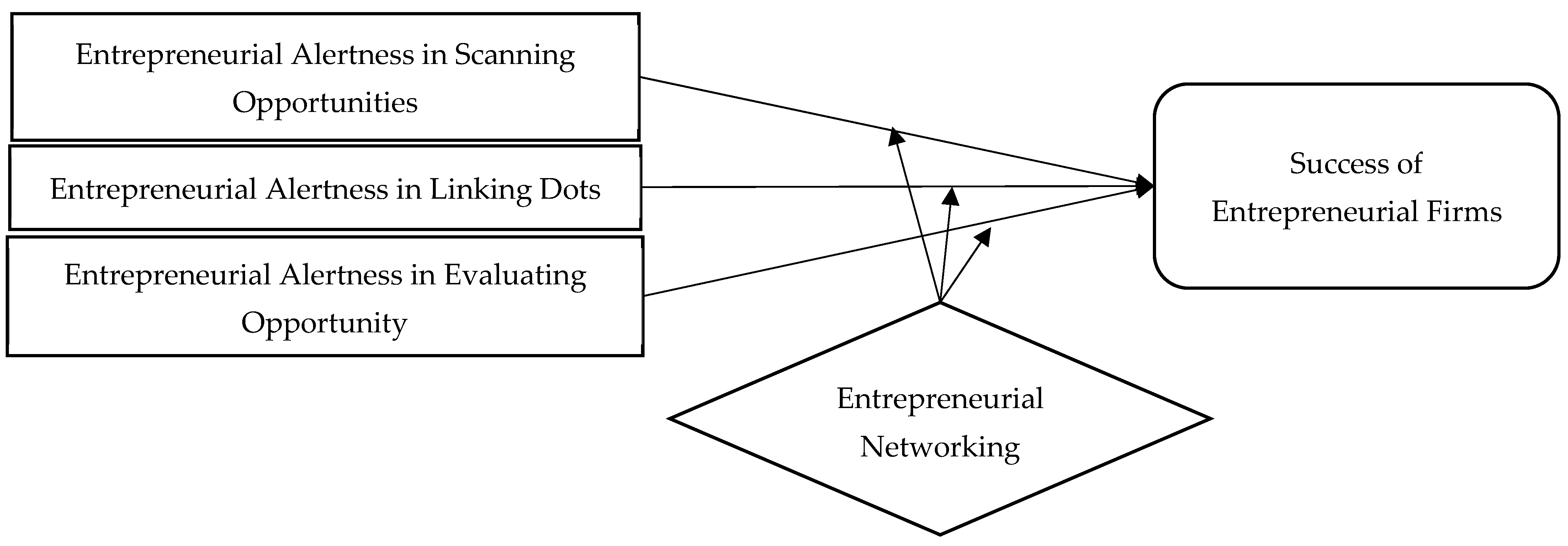

Based on an official definition of alertness in the entrepreneurship context, the ability to connect disparate pieces of information [

35], look through new information through a different lens [

36], and determine whether a fresh piece of knowledge offers a chance [

37] are the three behavioral components of entrepreneurial alertness. Therefore, it is better to divide entrepreneurial alertness into entrepreneurial alertness for scanning opportunities, entrepreneurial alertness in linking dots, and entrepreneurial alertness in evaluating opportunities.

2.1.1. Entrepreneurial Alertness in Scanning Opportunities

The procedures of noticing changes and transitions in an environment and determining if the dynamics create a business opportunity are included in the evaluation and judgment component [

38]. It is believed that high-alert business people are more likely to scan for shifts in the industry landscape to spot and grab an opportunity [

19]. Being conscious of alterations, transitions, chances, and missed opportunities can help entrepreneurs see and seize opportunities, which can bring significant value to their business [

39].

Gaining an understanding from studies on the entrepreneurial opportunity process is one approach to progressing the field’s understanding of the effects of entrepreneurial alertness on success [

40]. Although there are many different ways to conceptualize an entrepreneurial opportunity in the literature [

41,

42], hardly one prevalent theory holds a cognitive process that involves the act of identifying and then seizing an opportunity. Research has demonstrated that entrepreneurs can create opportunities or objectively find them [

43,

44]. From a discovery perspective, it would be right to claim that while entrepreneurs may identify opportunities in the market, success (i.e., entrepreneurial business success) cannot occur until the entrepreneur takes action to seize the opportunity before competitors do [

45]. Hence, the following hypothesis is developed:

H1. Entrepreneurial alertness in scanning opportunities significantly influences the success of entrepreneurial firms.

2.1.2. Entrepreneurial Alertness in Linking the Dots

Even if entrepreneurial alertness may have an impact on the success of entrepreneurial firms, the majority of research on the topic has concentrated on defining the traits of attentive entrepreneurs and the conceptual parameters of the idea [

22,

46,

47]. Additionally, several organizational outcome characteristics and entrepreneurial attentiveness have been connected in recent studies [

2,

48,

49,

50]. Considering the result of organizational success, attentive entrepreneurs move swiftly and nimbly when making decisions [

51]; hence, their firm is more likely to obtain a competitive edge. This is why entrepreneurial alertness can have an impact on the success of entrepreneurial firms.

The connection between performance and entrepreneurial alertness has not yet been fully specified theoretically, despite scholarly efforts to increase knowledge in this area [

34]. According to this theoretical viewpoint, when alert people take advantage of possibilities, alertness turns into an entrepreneurial tendency, which leads to success. It gives business owners the ability to apply their creative thinking to identify and analyze data in a variety of knowledge areas linked to the creation of new prospects [

52]. Thus, the following hypothesis is made:

H2. Entrepreneurial alertness in linking the dots significantly influences the success of entrepreneurial firms.

2.1.3. Entrepreneurial Alertness in Evaluating Opportunities

Furthermore, a tendency to grasp a fresh product–market opportunity is a necessary component of entrepreneurial activity [

46]. Successful entrepreneurs are best at judging the opportunities about their outcomes. This core act of entrepreneurship can be the introduction of a new product via internal corporate venturing or through an already-existing firm [

37]. Essentially, finding new possibilities and acting on them are the two main components of entrepreneurship [

53]. Although several research frameworks used a resource-based view and offered a more thorough account of how alertness influences the success of entrepreneurial firms than any other theory, they have hardly identified the need and importance of networking in exploiting how alertness impacts success of the entrepreneurial firms. According to the resource-based approach, resources are assets that business owners can utilize to identify and seize market opportunities [

15]. It is believed that these resources are dispersed differently across business owners and could even be particular to oneself [

36]. One of the main tenets is that success variance is not caused by entrepreneurial resources per se, but rather by the intentional efforts of entrepreneurs to develop, expand, and alter entrepreneurial resources [

8].

Because alert entrepreneurs are more likely to act quickly to seize opportunities in the market before others do, it is reasonable to assume that a rise in entrepreneurial alertness will result in the success of entrepreneurial firms [

43]. According to research, highly vigilant entrepreneurs can take advantage of expanding market segments [

54] before their rivals because they can better observe market trends and changes [

35] and can react to them sooner than their rivals. Therefore, a cunning entrepreneur can start a profitable new business before other entrepreneurs by acting to exploit a new market value proposition from a recognized opportunity [

55]. Consequently, the following hypothesis is developed:

H3. Entrepreneurial alertness in evaluating opportunity significantly influences the success of entrepreneurial firms.

2.2. Moderating Role of Entrepreneurial Networking

Growing an entrepreneurial firm is a social process that involves efforts by entrepreneurs to harness their networks to mobilize and deploy resources to exploit an opportunity [

13]. Most research on the topic has focused on the structural and relational networks that entrepreneurs are involved in and their outcomes, although entrepreneurial networking has significant implications for the success of entrepreneurial firms and has the potential to shed new light on the conditions under which opportunity exploitation affects the success of entrepreneurial firms [

56]. More relational linkages, structural gaps, and network diversity enable entrepreneurs to obtain a variety of network-based resources that improve the success of their entrepreneurial firms [

57]. The idea that all entrepreneurs can use network resources to achieve desired entrepreneurial business success is implicit [

58].

Researchers studying entrepreneurial networks, however, contend that success in entrepreneurial firms may not be significantly impacted by network resource availability in and of itself; rather, success is more likely to result from entrepreneurs’ capacity to take advantage of opportunities before others do by using their networks to mobilize resources [

59]. This suggests that the capacity of entrepreneurs to leverage resources contained in networks to seize entrepreneurial opportunities and attain entrepreneurial firm success outcomes may vary [

60]. However, only a few prior studies have concentrated on elucidating how business owners apply their networking activities to support the advantages they learn from their endeavors [

13,

61,

62]. To fill this vacuum in the literature on entrepreneurship, we integrate resource dependency theory with resource-based theory in this study. We investigate whether degrees of entrepreneurial networking influence the connection between entrepreneurial alertness and the success of entrepreneurial firms.

Entrepreneurial networking is the ability of an entrepreneur to mobilize resources available within an entrepreneurial network structure. This notion aligns with the academic discourse surrounding the creation and utilization of resources by entrepreneurs that are inherent in their network relationships [

63,

64,

65]. Accordingly, the current study sees entrepreneurial networking as a means for business owners to gather and integrate various resources and information for a desired purpose by taking advantage of their ties to local social peers and community leaders [

66].

Furthermore, personal information might reach entrepreneurs through the channels that entrepreneurial networking offers [

67]. To the extent that an awareness of how skillfully an entrepreneur uses pertinent market data during the exploitation phase will determine their capacity to take advantage of an entrepreneurial opportunity [

68,

69]. Since entrepreneurship entails a great deal of risk-taking and uncertainty, information is a vital tool for reducing uncertainty [

70,

71]. This argument is predicated on the knowledge that an entrepreneur’s capacity to use logic to select entrepreneurial networks can improve opportunities.

An increased impact of opportunity exploitation on new venture success results from the expansion of rationality’s bounds, which also improves the entrepreneur’s ability to screen and evaluate new venture ideas, possibilities, and possible sources of competitive advantages [

72]. Furthermore, an entrepreneur would likely rely on a variety of information to make decisions when pursuing an opportunity because they are exposed to new and varied business ideas, viewpoints from around the world, and a broader frame of reference through networking with social peers [

73]. Quality knowledge about entrepreneurial prospects is difficult to come by in less developed societies like Pakistan [

31] because it is typically held informally by important non-market actors like local market leaders.

However, these societies also heavily rely on kinship ties and collectivistic cultures [

74]. Entrepreneurs can use familial affinities to their advantage by using them as a source of information on significant factors that contribute to market success [

75,

76]. An entrepreneur can also leverage the sympathies formed in these types of networks to create unofficial rules that will keep trading partners from acting opportunistically and increase the chances of a venture’s success [

77].

Formal or informal contacts between suppliers and customers, for instance, are also considered to be the elements of entrepreneurial networking [

63]. The ability of an entrepreneur to build connections with important suppliers, competitors, and customers within a given industry is defined as entrepreneurial networking in this study, which is based on the body of existing literature on managerial linkages [

78]. Entrepreneurial networks give business owners access to resources and knowledge about the market that may not be available in the open market [

79]. Entrepreneurs can gain from a multidivisional structure that lowers transaction costs and offers economies of scale and breadth with the aid of entrepreneurial networking [

80].

Underdeveloped factor markets make it more difficult for entrepreneurs in developing nations like Pakistan to effectively purchase resources. Entrepreneurs can interact with banks, suppliers, distributors, buyers, and customers through entrepreneurial networking, which also helps them to overcome institutional barriers [

58]. In developing economies, entrepreneurs often face barriers to entry when trying to access vital markets [

45]. Within this setting, entrepreneurial networks serve to bridge gaps in the institution and promote the sharing of resources needed to start and expand profitable new businesses [

81].

To take advantage of business prospects in a local market, astute entrepreneurs need to have local business expertise, which is what entrepreneurial networking offers [

82]. The empirical research provides some insights into how entrepreneurial networking might enhance the success benefits of entrepreneurial firms [

13,

14,

61,

65]. We contend that the advantages (such as lower transaction costs) resulting from entrepreneurial networks [

80], the lowering of institutional barriers [

58], and the lowered risks and uncertainties [

70] associated with entrepreneurship brought about by having close relationships with industry leaders may increase the likelihood of seizing an opening for the success of an entrepreneurial firm.

One important realization is that networking with other entrepreneurs can help entrepreneurs learn about upcoming and present business prospects as well as industry trends, which can improve the quality of information that new entrepreneurs have access to when looking to take advantage of new chances [

61]. An entrepreneur may find it easier to begin a new business with improved insights into potential industry trends if they rely on high-quality market data [

83]. Entrepreneurs with connections in the entrepreneurial community have access to resources, guidance, and problem-solving abilities [

84]. With less time and effort required, entrepreneurs can develop an entrepreneurial opportunity by utilizing such an external network resource, as suggested by RDT. Thus, we propose the following three hypotheses:

H4. The entrepreneurial network moderates the positive relationship between entrepreneurial alertness in scanning opportunities and the success of entrepreneurial firms.

H5. The entrepreneurial network moderates the positive relationship between entrepreneurial alertness in linking the dots and the success of entrepreneurial firms.

H6. The entrepreneurial network moderates the positive relationship between entrepreneurial alertness in evaluating opportunities and the success of entrepreneurial firms.