Abstract

With the rapid advancement of battery technology and the demand for environmental sustainability, new energy vehicles (NEVs) are becoming more and more popular. This research paper delves into the impact of marketing strategies employed by new energy vehicle companies on consumers’ purchase intentions. This paper begins by highlighting the unique benefits of NEVs, such as energy efficiency, environmental friendliness, and improved driving experience. Then, this research identifies gaps in existing research, particularly the lack of micro-market demand data and systematic empirical analyses of consumer purchase intentions for NEVs. The paper employs a quantitative analysis approach grounded in marketing theory to address these gaps and examine the relationship between NEV companies’ marketing strategies and consumers’ purchase intentions. The research design involves a questionnaire survey based on the 4C marketing theory, focusing on consumer demand, cost, communication, and convenience. The survey targets potential NEV buyers and car owners, and 247 valid responses were analyzed. The results reveal that various factors, including the price and environmental performance of NEVs, non-fiscal policies, vehicle performance, and consumer attributes such as education level and environmental awareness, influence consumers’ willingness to purchase NEVs. This study also employs structural equation modeling to explore the correlations between different issues and identifies three main factors: basic car needs, new energy needs, and consumer subjective perception. Lastly, the study concludes that while NEV companies have made significant strides in marketing strategies, there is still room for improvement. We suggest that companies should offer competitive pricing, enhance vehicle performance, and address consumer concerns to boost purchase intentions.

1. Introduction

With the vigorous development of digital technologies such as artificial intelligence, big data, cloud computing, mobile Internet, and the Internet of Things, more and more companies are combining traditional transaction methods with new technologies, new channels, and new customer needs to explore innovative business models and marketing strategies [1]. In practice, enterprises build competitive advantages and obtain market resources through marketing strategies to achieve long-term economic benefits [2,3,4]. Companies such as Apple, Amazon, Tesla, and Alibaba have all achieved considerable development with the help of a series of successful marketing strategies. Marketing strategy and theory have always been research hotspots in academia. From the initial conceptual definition to the continuous enrichment of a large number of theoretical and practical results, marketing strategies are considered to be able to meet the personalized needs of customers in a fast and high-quality way, and improve the core competitiveness and market share of the enterprise to promote the sustainable development of the enterprise [5,6,7,8].

Take the development of the new energy automobile industry as an example. Compared with traditional fuel vehicles, new energy vehicles have apparent power, energy saving, environmental protection, driving experience, and post-maintenance advantages [9,10]. In recent years, under increasingly strengthened resource and ecological constraints, cultivating the new energy automobile industry has become an intrinsic requirement for transforming and upgrading the automobile industry and establishing new advantages in international competition [11,12]. The new energy vehicle industry is still in the “technical and commercial demonstration” stage. High prices, low market demand, high risks, and low consumer awareness are common characteristics of emerging industries. Consumer demand is still to be started. Therefore, giving full play to the driving role of market demand in the new energy vehicle industry has become a common practice in industrialized countries around the world: at the government level, from the perspectives of tax reductions and exemptions, financial subsidies, industrial policies, etc., it is necessary to support automobile companies and consumers from both sides of supply and demand [13,14,15]. At the corporate level, new energy vehicle manufacturing forces led by Tesla and BYD are actively expanding their business scope, and traditional fuel vehicle companies such as Volkswagen have also begun to spend vast sums of money to compete in the new energy vehicle sector [16].

However, although NEVs have shown strong sales momentum with the support of strong subsidy policies and promotional strategies, NEVs still have not shaken the dominance of traditional fuel vehicles. On the one hand, new energy vehicles have not achieved leapfrog development in the private consumer market. Relevant research shows that the increase in energy crisis and environmental awareness are insufficient conditions to encourage consumers to purchase new energy vehicles [17]. Consumers are very concerned about new energy vehicles. There are considerable concerns about price, cruising range, safety performance, and charging convenience [18].

On the other hand, the new energy vehicle market is low in concentration, has few well-known brands, and lacks effective marketing plans for new energy vehicles, putting it at a temporary disadvantage in competition with the traditional fuel vehicle industry. At present, the United States, Germany, France, China, and other countries have successively announced that they will tighten their subsidy policies for new energy vehicles. New energy vehicles’ sales growth has slowed, and market competition has become increasingly fierce. How new energy vehicle companies formulate reasonable and effective marketing strategies to increase consumers’ willingness to purchase new energy vehicles has become a significant problem in developing new energy vehicles.

Although some scholars have studied the factors influencing the purchase of new energy vehicles from different angles and found that economic benefits, vehicle performance, environmental protection needs, policy orientation, etc., are all critical factors affecting consumers’ purchase intention [19,20,21,22], there are still topics worthy of further exploration. First, the new energy vehicle industry lacks micro-market demand data. Scholars’ research on consumer purchase intention is primarily qualitative, and empirical analysis is relatively weak; second, existing research often focuses on the influencing factors of new energy vehicle purchases. The empirical list is not theoretical and systematic enough; thirdly, there is still a lack of research on improving consumers’ willingness to purchase new energy vehicles from a business perspective.

Based on these gaps, this article attempts to use marketing theory as the cornerstone, design a survey questionnaire from a more micro perspective of enterprises, and use quantitative methods to analyze the impact of marketing strategies of new energy vehicle enterprises on consumer purchase intention, thereby providing new ideas for promoting the steady development of the new energy industry. The rest of this research is structured as follows: the second part conducts a systematic review of relevant literature about NEV development; the third part introduces the questionnaire design of this survey; the fourth part performs data analysis and testing; and finally, the full-text summary and marketing suggestions are presented.

2. Related Works

Consumers’ willingness to purchase new energy vehicles is related to many factors. Scholars have extensively discussed the impact of new energy vehicle product attributes and industrial policies on consumer behavior, such as sales price, usage cost, speed performance, etc. Through an online questionnaire survey of 482 Canadian households, Potoglou et al. found that lower prices and improved environmental performance of new energy vehicles can effectively promote the use of new energy vehicles. At the same time, non-fiscal policies such as free parking and setting up dedicated lanes do not affect consumer purchases [23]. Krupa’s survey of 1000 residents in the United States shows that consumers pay more attention to the reduction in energy consumption costs of new energy vehicles but pay less attention to the environmental benefits of electric vehicles [17]. Helveston conducted a joint survey of consumers from the United States and China and found that both countries prefer new energy vehicles with lower prices and usage costs, shorter acceleration times, and faster charging processes [24]. Lane and Potter conducted a unique study on the British new energy vehicle market regarding the support effect of industrial policies. They concluded that the government’s environmental regulations, oil price policies, purchase subsidies, and infrastructure construction would significantly affect the purchase of new energy vehicles [25]. Through a survey of China’s new energy vehicle market, Zhang et al. found that government policies play a regulatory role in accepting new energy vehicles [15].

In addition to product attributes and industrial policies, sector scholars have found that consumers’ attributes also affect their preferences for new energy vehicles. Carley examined American consumers’ acceptance of new energy vehicles and found that the higher the education level of consumers, the greater the probability of purchasing new energy vehicles [26]. Kahn analyzed the willingness of American consumers to buy new energy vehicles and found that consumers’ environmental awareness is directly proportional to their preference for new energy vehicles [27]; Tu and Yang also reached similar conclusions in their survey of the Chinese market [10]. Axsen surveyed 508 households in California and found that the more substantial consumers’ sense of social responsibility, environmental awareness, and national awareness, the more likely they are to choose new energy vehicles [28].

Based on the above research, it can be seen that although scholars have conducted a lot of discussions on the influencing factors of consumers purchasing new energy vehicles, this research mainly focuses on the three directions of macro policy effects, micro consumer surveys, and new energy vehicle technology. There are few studies on the aspects of new energy vehicles. From a business perspective, we explore how to increase consumers’ willingness to purchase new energy vehicles. Based on this, this research conducts a questionnaire survey on potential buyers of new energy vehicles based on marketing theory, aiming to analyze the relationship between the marketing strategies of new energy vehicle companies and consumers’ purchase intentions. This study supplements and enriches the breadth and depth of existing research on new energy vehicle purchase intention, and also provides a new perspective for relevant research on the development of the new energy vehicle industry.

3. Research Design

3.1. Questionnaire Design

Based on the 4C marketing theory as a framework and based on the actual development of the new energy vehicle market, a new model is formulated from four aspects: consumer demand (Consumer), consumer cost (Cost), consumer communication (Communicate), and consumer convenience (Convenience)—questions from the marketing strategy questionnaire for energy vehicle companies. As a classic marketing theory, 4C marketing theory has been used since it was first proposed by American scholar Lauterborn in 1990. It is consumer demand-oriented, focuses on customer needs and satisfaction, and recommends that companies reduce consumer purchase costs. At the same time, effective consumer-centered marketing communications should also provide convenience for consumers to purchase and use [29].

- (1)

- Consumer

Consumer needs show diversity and hierarchy. According to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs theory, consumers’ demand for new energy vehicles extends from essential transportation tools to the pursuit of brand and identity. The survey shows that consumers usually have commuting, safety, environmental protection, brand, and respect needs when purchasing new energy vehicles. Based on this, this research generated questionnaire items and determined eight questions, such as “I pay attention to the appearance design of new energy vehicles”.

- (2)

- Cost

Consumer Cost is the total cost incurred by consumers in purchasing and using products, including the time cost and learning cost for consumers to understand new energy vehicles, the actual price of purchasing new energy vehicles, and other investment opportunities lost by purchasing new energy vehicles. Cost, subsequent maintenance and repairs, and insurance costs are factors to consider. Based on this, this research generated questionnaire items and determined 3 questions, such as “I hope to provide consumers with car purchase credit, such as “zero down payment car purchase”, etc.”.

- (3)

- Communicate

Consumer Communication is establishing a two-way communication channel between enterprises and consumers. The 4C marketing theory emphasizes that everything starts from the consumer’s perspective, regularly collects consumers’ opinions and suggestions, and processes feedback promptly so as to obtain the value recognition of consumers’ emotional communication; offline 4S stores are not just physical exhibition halls but also consumer experiences. An excellent venue, explanations and promotions by excellent sales staff, and patient demonstrations and services by professional test drive guides can all increase the added value of consumer communication. Based on this, this research generated questionnaire items and determined three questions, such as “I hope to launch offline activities such as “free trial””.

- (4)

- Convenience

Consumer Convenience shortens the physical and psychological distance between consumers and products. For the new energy vehicle market, the “difficulty in charging” problem is the main reason restricting the further development of the industry. Therefore, it is imperative to improve the coverage of charging infrastructure. In addition, consumers are worried about the density of after-sales outlets and the battery life of new energy vehicles. New energy vehicle companies should actively improve the after-sales service network of new energy vehicles and reuse existing vehicle after-sales service channels and facilities as much as possible, providing means and methods of battery maintenance and upkeep to increase battery life. Based on this, this research generated questionnaire items and determined three questions, such as “I would like to provide a ‘battery rental’ service to extend the vehicle life”.

3.2. Questionnaire Basic Information

The subjects of this online questionnaire survey are potential consumers of new energy vehicles and users who have purchased cars. The content of the questionnaire was formulated by the author team after repeated revisions based on existing literature. The questionnaire was based on English and translated into Chinese. Before it was officially launched, it underwent multiple language translations and simulated filling in to ensure that the fillers could accurately understand and answer relevant questions.

This questionnaire is divided into two parts. The first part is the basic information of the respondents, and the second part is a survey of the factors that influence the respondents to purchase new energy vehicles. The scope of this survey covers Beijing, Shanghai, Jiangsu Province, and other regions in China, and a total of 265 questionnaires were collected. In order to ensure the validity of the questionnaire, this article eliminated questionnaires with incomplete answers and obvious logical errors and retained 247 valid questionnaires. The detailed results of the questionnaire are shown in Table S1.

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Analysis

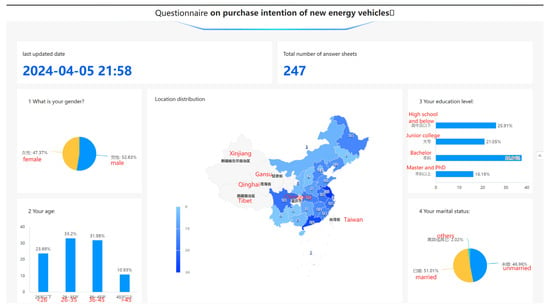

Demographic variables mainly refer to the economic, cultural, and social characteristics of the research subject. Taking into account the complexity of the survey and the main purpose of the survey, the demographic indicators of this questionnaire are divided into the following five categories: gender, age, education level, marital status, and personal income. Most of the respondents in this questionnaire survey are young people, with an average age between 26 and 45 years old. Among them, there are slightly more men than women, most of them have received higher education, and their personal incomes are mostly above the middle level. The basic information about the interviewees is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Basic information of respondents.

4.2. Questionnaire Analysis

4.2.1. Questionnaire Reliability Analysis

The second part of the questionnaire adopts the form of a five-level scale, aiming to investigate the respondents’ interest in purchasing new energy vehicles based on the 4C theory. First, a reliability analysis was conducted on the scale. The Cronbach’s α coefficient calculation table is shown in Table 1:

Table 1.

Cronbach’s α coefficient.

The Cronbach’s α coefficient value of the model is 0.982, and the standardized Cronbach’s α coefficient value is 0.985, both exceeding 0.9, indicating that the reliability of the questionnaire is very good.

Next, statistics on the deletion analysis items of the questionnaire were carried out. Through the control variable method, the correlation, Cronbach’s α coefficient, and other indicators before and after the deletion of a certain item were compared to assist in judging whether the scale items should be revised. The results are shown in Table 2:

Table 2.

Statistics on the deletion analysis items.

It can be seen that after deleting any question, the mean fluctuation of the questionnaire is extremely small, and the variance fluctuation is also within a certain range, indicating that the results obtained for each question tend to be stable as a whole. The overall correlation after deleting any item remains at a high level, and the α coefficient after deleting any item is less than the standardized Cronbach’s α coefficient value of 0.985. These two results indicate that the questionnaire questions are designed reasonably and the scale items do not need to be modified.

4.2.2. Questionnaire Results Analysis

According to the data on the five-level scale, it can be calculated that the average score of each question ranges from 3.18 to 3.40 points. In general, all questions exceed 3 points (average score on the five-level scale). This shows that the above issues are all considered by potential consumers of new energy vehicles to a certain extent.

The questions with the highest scores were “The price of new energy vehicles is higher than my psychological expectations”, “I attach great importance to the energy saving and environmental protection of new energy vehicles”, and “I hope to launch offline activities such as ‘free trial’”, “I pay attention to new energy vehicles”. “The cruising range of energy vehicles” and “I am concerned about the intelligent services of new energy vehicles” also exceeded 3.35 points. These results fully demonstrate consumers’ attention to aspects such as price, sustainability, trial services, battery life, and intelligence. New energy vehicle companies can conduct more in-depth marketing and more detailed introductions in these areas.

On the other hand, “I hope to provide consumers with car purchase credit, such as ‘zero down payment car purchase’”, “I hope to launch exclusive insurance for new energy vehicles”, “I hope to add brand exclusive experience stores and community after-sales service points”, and “I value the “safety of new energy vehicles” scores were all below 3.22 points. This part of the results reflects that credit plans, exclusive insurance, exclusive experience stores, and the safety of new energy vehicles are of little significance in stimulating consumers’ purchase interest. In fact, many traditional vehicle companies will also provide similar services. New energy vehicle companies may consider more innovative marketing policies, such as “launching exclusive insurance” instead of “buying a car and getting insurance”, and “purchasing a car with zero down payment” instead of “purchasing a car with a low-down payment and low interest rate”.

4.2.3. Structural Equation Modeling

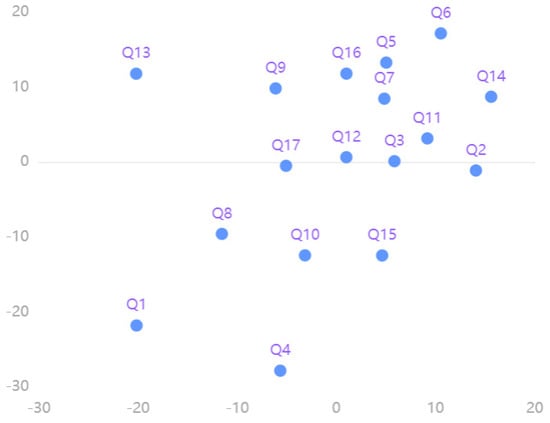

In order to further explore the correlation between problems, this study was then factor analyzed using structural equation modeling. Prior to this, this study used multidimensional scaling analysis to obtain the distance matrix (in Table S2) between each problem, reflecting the degree of difference between the problems. The spatial perception map obtained by the analysis is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Spatial perception map.

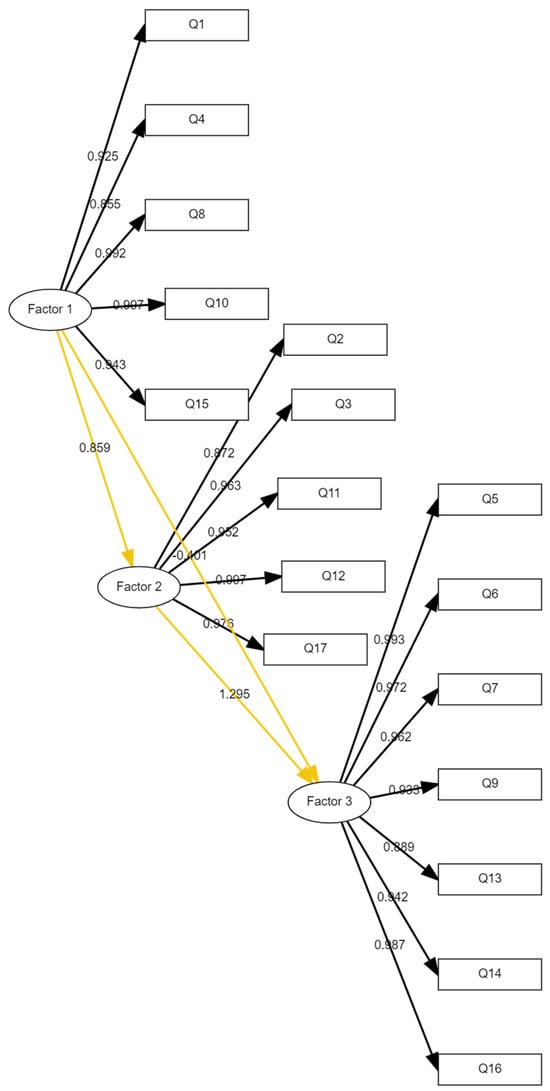

Combining Table S2 and Figure 2, this study divided factors according to the vertical dimension and determined that Q1, Q4, Q8, Q10, and Q15 are factor 1; Q17, Q12, Q3, Q11, and Q2 are factor 2; and Q13, Q9, Q16, Q5, Q7, Q6, and Q14 are factor 3. After bringing these factors into the structural equation model (SEM), the results are shown in Figure 3 and Table 3.

Figure 3.

SEM path diagram.

Table 3.

SEM factor loading coefficient.

The following can be seen from the model path coefficient table: Based on Q4 (significant p-value is 0.002 ***), Q8 (significant p-value is 0.000 ***), Q10 (significant p-value is 0.000 ***), Q15 (significant p-value is 0.000 ***), and factor 2 (significant p-value is 0.003 ***), the null hypothesis is rejected, and its standard loading coefficients are all greater than 0.4. It can be considered that it has a sufficient variance explanation rate to express the ability of each variable displayed on the same factor. Based on Q12 (significant p-value is 0.000 ***), Q3 (significant p-value is 0.000 ***), Q11 (significant p-value is 0.000 ***), Q2 (significant p-value is 0.000 ***), and factor 3 (significant p-value is 0.000 ***), the null hypothesis is rejected, and its standard loading coefficients are all greater than 0.4. It can be considered that it has a sufficient variance explanation rate to express the ability of each variable displayed on the same factor. Based on Q6 (significant p-value is 0.000 ***), Q7 (significant p-value is 0.000 ***), Q9 (significant p-value is 0.000 ***), Q13 (significant p-value is 0.000 ***), Q14 (significant p-value is 0.000 ***), and Q16 (significant p-value is 0.000 ***), the null hypothesis is rejected, and its standard loading coefficients are all greater than 0.4. It is considered that it has a sufficient variance explanation rate to show that each variable can be displayed on the same factor. In short, the factor loading coefficients and significance of each question performed very well, indicating that the factor division was reasonable and effective.

4.2.4. Factor Analysis

Next is the path analysis between factors. The regression coefficient of the path node can be considered as a linear regression using the least squares method. Usually, it is only necessary to observe the p-value and the standardized path coefficient to determine whether the path (X→Y) has a direct linear impact. If there is significance, it means that there is an influencing relationship between variables, and the standardized path coefficient can be used to conduct an in-depth analysis of the influencing efficiency. The regression coefficient is shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Regression coefficient.

It can be seen from the model path coefficient table that based on the paired item factor 1→factor 2, the significant p-value is 0.003 ***, showing a strong significance level, then the null hypothesis is rejected, so this path is valid, and its influence coefficient is 0.859. Based on the paired term factor 1→factor 3, the significant p-value is 0.10, and there is a certain level of significance, then the null hypothesis is rejected, so this path is valid, and its influence coefficient is −0.401. Based on the paired term factor 2→factor 3, the significant p-value is 0.000 ***, showing a strong significance level, then the null hypothesis is rejected, so this path is valid, and its influence coefficient is 1.295.

Factor 1: Basic Car Needs

According to the empirical results, the cruising range, safety, group friendliness, credit services, and product after-sales of new energy vehicles are summarized into factor 1, reflecting consumers’ basic needs for new energy vehicles as personal transportation tools.

First, cruising range and safety are the primary factors new energy vehicle consumers consider. Since the cruising range of new energy vehicles directly affects consumers’ convenience of daily use, the longer the cruising range, the higher the practicality of the vehicle, and the stronger the consumer’s willingness to purchase. Consumers have doubts about the safety of new energy vehicles. This is mainly affected by the spread of the insufficient collision resistance of new energy vehicles and the explosion of electric vehicle batteries in online media.

Secondly, new energy vehicles are increasingly attractive to female consumers. Studies have shown that women are gradually becoming decision-makers in family car purchases, and the proportion of female drivers also increases yearly. Therefore, more female-friendly model designs will help meet consumer demand for new energy vehicles.

Thirdly, credit services and product after-sales are essential decision-making factors when purchasing new energy vehicles. At this stage, new energy vehicles’ production costs and sales prices are generally high, and relatively higher-end fuel vehicles can be purchased at the same price. Consumers hope to alleviate the pressure of paying out-of-pocket for car purchases through consumption activities such as “zero down payment car purchase”. For emerging industries, perfect after-sales service can bring more protection to consumers. The insufficient density of new energy vehicle after-sales service outlets and high maintenance costs are important reasons why consumers are reluctant to buy new energy vehicles.

What is not very consistent with theoretical expectations is that energy conservation and environmental protection awareness are not common demands among new energy vehicle consumers. Although low-carbon products are welcomed by consumers, the quality of new energy vehicles themselves is the ultimate guarantee for the industry’s sustainable development.

Factor 2: New Energy Needs

The appearance design, smart services, exclusive insurance, publicity and promotion, and battery rental services of new energy vehicles are classified into factor 2, reflecting consumers’ special needs for new energy vehicles as emerging products that are different from traditional fuel vehicles.

First of all, the appearance design and intelligent services of new energy vehicles are important factors that attract consumers. By using high-tech materials and novel design techniques, new energy vehicles present a more fashionable image in appearance, which is in line with the external image that some consumers pursue. Compared with traditional fuel vehicles, new energy vehicles usually have more intelligent functions, such as smart cockpits, intelligent assisted driving, etc., which not only provide consumers with an excellent car experience but also allow them to experience the charm of technology.

Secondly, the supporting insurance and battery leasing business of new energy vehicles will also affect consumers’ purchase intention. At present, the new energy automobile insurance service and pricing system are in their infancy. The pricing of automobile insurance is on the high side, far exceeding consumers’ expectations. Problems such as “expensive automobile insurance and difficulty in settling claims” hinder consumers’ willingness to purchase. Models such as battery leasing can reduce the one-time cost investment of new energy vehicle consumers, thereby increasing consumers’ desire to purchase.

Thirdly, increasing the publicity and promotion of new energy vehicles can also improve consumer acceptance. Consumers have a relatively mature understanding of traditional fuel vehicles, but less knowledge of new energy vehicles. During the car purchase process, they will have doubts about the brand, quality, price, and after-sales service of new energy vehicles. Car companies have stepped up publicity efforts to help consumers learn more about new energy vehicles, thereby eliminating concerns about the safety and reliability of new energy vehicles.

Factor 3: Consumer Subjective Perception

The opinions of people around new energy vehicles, brand awareness, offline activities, comfort, energy conservation and environmental protection, price, and charging pile construction are summarized into factor 3, reflecting that consumers’ subjective attitudes play an important role in their purchasing behavior.

First of all, the opinions of surrounding people, brand awareness, and offline promotion activities all affect consumers’ purchase intention to a certain extent. Due to the lack of purchasing experience, product-related knowledge, and cognitive abilities, consumers will be affected by the opinions or behaviors of relevant groups when purchasing new energy vehicles. Some consumers may even be forced to purchase new energy vehicles due to social norms and pressure from surrounding groups. The popularity of famous brands and the organization of offline trial driving activities can enhance consumers’ trust from a psychological level, thus increasing their purchase intention.

Secondly, as new energy vehicles are green innovative products, consumers’ purchasing behavior will be affected by personal environmental awareness. Consumers who advocate for environmental awareness are more inclined to purchase new energy vehicles. At the same time, consumers who pursue a high-comfort experience are also more inclined to purchase new energy vehicles. In addition, the perceived value of new energy vehicles is also an important factor affecting consumers’ purchase intention.

Finally, as an important part of the new energy vehicle consumption chain, the coverage of charging facilities is also a matter of concern to consumers. The popularization of charging piles and the development of fast charging technology can improve the experience of using new energy vehicles and have a positive impact on consumers’ purchasing intentions.

Interaction between Factors

There is a significant positive correlation between the characteristic demand for new energy vehicles and consumers’ subjective attitudes (p = 0.000 ***). The above results illustrate the importance of the quality of new energy vehicles in the consumer purchase decision-making process, because its product characteristics will directly affect consumers’ purchasing attitude. In the fierce competition with the traditional fuel vehicle market, the unique advantages of new energy vehicles in terms of design, performance, configuration, etc., are the key factors in attracting consumers to purchase.

In addition, the correlation analysis results show that the basic needs of traditional automobiles promote consumers’ subjective attitudes, but this is not very significant (p = 0.10 *). On the one hand, consumers have increasingly higher functional requirements for new energy vehicles, and functional improvements based on traditional vehicles cannot fully meet their purchase needs; on the other hand, basic needs have not been directly transformed into purchase intentions for new energy vehicles, and it is because consumers are concerned about issues such as insufficient safety protection, imperfect after-sales service, and inconvenient charging of new energy vehicles.

5. Conclusions

Cultivating the new energy automobile industry is not only a need to deal with energy and environmental sustainability issues but also an intrinsic requirement to promote the transformation and upgrading of the automobile manufacturing industry and the sustainable development of the transportation industry. In order to clarify the impact of new energy vehicle companies’ marketing strategies on consumers’ purchase intentions, this article designed a questionnaire on many marketing factors involved in the purchase process of new energy vehicles, used structural equation modeling to conduct an empirical test on the influencing factors of consumers’ purchase intentions, the heterogeneous impact of different marketing strategies on consumers’ purchase intentions was examined, and the following conclusions were drawn: (1) the primary demand for traditional cars, the characteristic demand for new energy vehicles, and consumers’ subjective attitudes all influence consumer purchases and are essential factors in willingness to purchase; (2) energy saving and environmental protection needs are not the primary factors that consumers consider when purchasing new energy vehicles; (3) consumer demand for new energy vehicles is in line with Maslow’s hierarchy of needs theory, starting from basic transportation needs developing towards higher-level characteristic demands; (4) compared with traditional fuel vehicles, the unique advantages of new energy vehicles in design, performance, configuration, etc., are the key to attracting consumers to buy.

The results of this study provide data samples for the adjustment and upgrade of new energy vehicle companies’ marketing strategies: (1) Consumers are very concerned about the price, cruising range, and intelligent services of new energy vehicles. The team recommends that relevant companies reward consumers with more favorable prices and vigorously develop batteries with better battery life and more convenient “human–vehicle system” interconnection. (2) Consumers are also very concerned about the environmental sustainability of new energy vehicles. Compared with price and technology, environmental sustainability seems to be often ignored by the companies involved. The results of this study mean that companies should not overlook this critical factor in consumers’ purchase intentions. Our team suggests that car companies can use public service advertisements or engaging animations to introduce the environmental friendliness of each model to potential buyers in addition to data-based indicators such as price and technology. (3) New energy vehicle companies should pay attention to in-depth analyses of consumer demand psychology. This study shows that consumers’ subjective attitudes affect their willingness to purchase cars. Consumers not only pursue high-quality products and services but also pay attention to factors such as brand awareness, opinions of surrounding people, and brand reputation. Therefore, companies must uphold an attitude of integrity, have the courage to assume environmental responsibilities, promote the positive role of new energy vehicles in environmental protection, and demonstrate the large amount of resources and efforts invested in product innovation, so as to gain the trust of consumers and promote consumers’ willingness to purchase new energy vehicles.

Regarding the marketing strategies of new energy vehicle companies, this study suggests that companies can adopt a “factor interaction” strategy and use combination marketing methods to expand vehicle sales and brand influence further. The results show a significant positive correlation between the demand for new energy vehicle features and consumers’ subjective attitudes, so car companies can increase their efforts to promote the features unique to new energy vehicles differentially. For example, automobile products related to mobile phone giants such as Xiaomi and Huawei can vigorously promote special functions such as cockpit interconnection, car–machine systems, and tablet controls to highlight the differences between the products and fuel vehicles, thereby affecting consumers’ subjective purchase intentions. On the other hand, the basic needs of traditional cars have a promoting effect on consumers’ subjective attitudes, but it is not very significant. This study believes that some NEV brands place too much emphasis on racing parameters, such as an acceleration time of 100 km. In fact, it is almost entirely unused in daily urban traffic. The insignificant results also illustrate the consumer’s attitude towards basic parameters. To sum up, this study believes that NEV companies should have differentiated publicity and introduce the unique functions that fuel vehicles do not yet have on a large scale to promote consumers’ purchase intention and achieve better sales performance.

This study also has certain limitations. On the one hand, although this study raises the statement of “I value the brand awareness of new energy vehicles” related to the brand, with the direct or indirect participation of Internet giants such as Huawei, Xiaomi, and Alibaba, brand awareness will be further refined. Transformation is no longer limited to car brands. For example, Changan Automobile uses Huawei’s smart driving solution in two models, and some Shanghai Automobile models use Alibaba’s cloud computing services. Therefore, these models that integrate the giants’ resources do not fully represent their brands. In subsequent research, our team will further explore this “giant crossover” model. On the other hand, since the author team mainly focuses on management background, the design of some questions is relatively superficial and can be further refined in the future. For example, in the question “Infrastructure supporting facilities”, we chose to construct charging piles. In fact, more technical means can be considered for this topic, such as 800 V high-voltage platforms and car body-integrated die-casting. We plan to cooperate with scholars in vehicle engineering, energy and power engineering, and mechanical engineering in the future to investigate more detailed technical solutions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su16104119/s1, Table S1: Questionnaire on purchase intention of new energy vehicles; Table S2: Distance matrix.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.X.; methodology, S.W., H.X. and S.Z.; validation, S.W. and J.C.; formal analysis, S.W.; investigation, S.W. and S.Z.; writing—original draft, S.W. and J.C.; writing—review & editing, H.X. and S.Z.; funding acquisition, H.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Jiangsu University of Science and Technology, grant number 1122932310, title: “Doctoral Research Start-up Fund of Jiangsu University of Science and Technology: 1122932310”.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The questionnaire data used in this study and related analysis results are presented in the Supplementary Materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Grondys, K. Implementation of the Sharing Economy in the B2B Sector. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, R.G.; Ioannou, I.; Serafeim, G. The Impact of Corporate Sustainability on Organizational Processes and Performance. Manag. Sci. 2014, 60, 2835–2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketprapakorn, N.; Kantabutra, S. Sustainable Social Enterprise Model: Relationships and Consequences. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, M.Y.-P.; Lin, K.-H.; Peng, D.L.; Chen, P. Linking Organizational Ambidexterity and Performance: The Drivers of Sustainability in High-Tech Firms. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharadwaj, A.S. A resource-based perspective on information technology capability and firm performance: An empirical investigation. Mis Q. 2000, 24, 169–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crick, J.M.; Crick, D. Coopetition and COVID-19: Collaborative business-to-business marketing strategies in a pandemic crisis. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020, 88, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pansari, A.; Kumar, V. Customer engagement: The construct, antecedents, and consequences. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2017, 45, 294–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, B.L.; Freeman, R.E.; Harrison, J.S.; Wicks, A.C.; Purnell, L.; de Colle, S. Stakeholder Theory: The State of the Art. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2010, 4, 403–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Wu, Q.; Li, M.; Gu, Y.; Yang, J. What Is Affecting the Popularity of New Energy Vehicles? A Systematic Review Based on the Public Perspective. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, J.-C.; Yang, C. Key Factors Influencing Consumers’ Purchase of Electric Vehicles. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeydeera, L.H.U.W.; Mesthrige, J.W.; Samarasinghalage, T.I. Global Research on Carbon Emissions: A Scientometric Review. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Wu, M.; Tian, X.; Zheng, G.; Du, Q.; Wu, T. China’s Provincial Vehicle Ownership Forecast and Analysis of the Causes Influencing the Trend. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denstadli, J.M.; Julsrud, T.E. Moving Towards Electrification of Workers’ Transportation: Identifying Key Motives for the Adoption of Electric Vans. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Bai, X. Incentive policies from 2006 to 2016 and new energy vehicle adoption in 2010-2020 in China. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 70, 24–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, K.; Hao, Y.; Fan, J.-L.; Wei, Y.-M. The impact of government policy on preference for NEVs: The evidence from China. Energy Policy 2013, 61, 382–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapustin, N.O.; Grushevenko, D.A. Long-term electric vehicles outlook and their potential impact on electric grid. Energy Policy 2020, 137, 111103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupa, J.S.; Rizzo, D.M.; Eppstein, M.J.; Lanute, D.B.; Gaalema, D.E.; Lakkaraju, K.; Warrender, C.E. Analysis of a consumer survey on plug-in hybrid electric vehicles. Transp. Res. Part A-Policy Pract. 2014, 64, 14–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, J.; Golob, T.F. Clean air forever? A longitudinal analysis of opinions about air pollution and electric vehicles. Transp. Res. Part D-Transp. Environ. 1998, 3, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Liu, D.; Sovacool, B.K.; Wang, Y.; Ma, S.; Li, R.Y.M. Who buys New Energy Vehicles in China? Assessing social-psychological predictors of purchasing awareness, intention, and policy. Transp. Res. Part F-Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2018, 58, 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, S.-f.; Zhao, D.; Luo, R.-j. Evolutionary game analysis on local governments and manufacturers’ behavioral strategies: Impact of phasing out subsidies for new energy vehicles. Energy 2019, 189, 116064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhao, C.; Yin, J.; Zhang, B. Purchasing intentions of Chinese citizens on new energy vehicles: How should one respond to current preferential policy? J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 161, 1000–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Xu, M.; Li, R.; Yu, L. Research on Group Choice Behavior in Green Travel Based on Planned Behavior Theory and Complex Network. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potoglou, D.; Kanaroglou, P.S. Household demand and willingness to pay for clean vehicles. Transp. Res. Part D-Transp. Environ. 2007, 12, 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helveston, J.P.; Liu, Y.; Feit, E.M.; Fuchs, E.; Klampfl, E.; Michalek, J.J. Will subsidies drive electric vehicle adoption? Measuring consumer preferences in the US and China. Transp. Res. Part A-Policy Pract. 2015, 73, 96–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, B.; Potter, S. The adoption of cleaner vehicles in the UK: Exploring the consumer attitude-action gap. J. Clean. Prod. 2007, 15, 1085–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carley, S.; Krause, R.M.; Lane, B.W.; Graham, J.D. Intent to purchase a plug-in electric vehicle: A survey of early impressions in large US cites. Transp. Res. Part D-Transp. Environ. 2013, 18, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, M.E. Do greens drive Hummers or hybrids? Environmental ideology as a determinant of consumer choice. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2007, 54, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axsen, J.; Kurani, K.S. Hybrid, plug-in hybrid, or electric-What do car buyers want? Energy Policy 2013, 61, 532–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauterborn, B. New marketing litany: Four Ps passé: C-words take over. Advert. Age 1990, 61. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).