The Basic Process of Lighting as Key Factor in the Transition towards More Sustainable Urban Environments

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Vehicle speed;

- Traffic volume and composition;

- The presence of parked vehicles;

- The difficulty of navigational tasks;

- Ambient luminosity.

- The advances in our understanding of the non-visual effects of light have highlighted their impact on people’s performance [7,8,9,10], health [11,12] and physical and physiological wellbeing [13,14,15,16]. This has made illumination a much more complex challenge than simply achieving the requirements of some guidelines. The changes in human output due to lighting conditions are becoming so extensive and better understood that they cannot be neglected anymore.

- Many aspects are left out of the criteria, including both non-physical factors (such as the reputation, levels of criminality or accident rates in a given area) and physical ones like urban furniture and other elements.

- The social profile and individual characteristics or preferences of the users, such as their age, gender, cultural and socioeconomic level or vulnerability, are not taken into account in the regulations nor the plans of local administrations.

- Ideological and political factors could prevail over strictly technical criteria, especially during electoral periods.

- The shortcomings above, being rather general, leave a significant part of the decision making to the discretion of designers and politicians. This may lead to inequalities among different cities and even neighborhoods or streets within the same city [17].

- (1)

- Establish a new conceptual framework;

- (2)

- List all the potential factors that have an influence on public lighting;

- (3)

- Survey people’s feelings about these factors;

- (4)

- Assess the quality of the regulations and score them according to the results of the survey;

- (5)

- Develop methods aimed at improving the perceived quality, and;

- (6)

- Extend or amend the current legislation to include the main factors identified and the well-being of the users, a key point for Sustainable Development when considered from a more general perspective [25].

2. Materials and Methods

- How relevant for your feeling of SAFETY AND SECURITY is the WEATHER?

- How relevant for your feeling of SAFETY AND SECURITY is the presence of TREES?

- How relevant for your feeling of SAFETY AND SECURITY is the presence of TRAFFIC?

- How relevant for your feeling of SAFETY AND SECURITY is the COLOUR OF THE LIGHT emitted by the public lighting systems?

- How relevant for your feeling of SAFETY AND SECURITY is the SOCIOECONOMIC LEVEL OF THE NEIGHBOURHOOD?

- How relevant for your feeling of SAFETY AND SECURITY is the presence of SHADOWS (cast by trees, buildings, obstacles, etc.)?

- How relevant for your feeling of SAFETY AND SECURITY is the happening of RECENT INCIDENTS in the area?

- How relevant for your feeling of SAFETY AND SECURITY is the presence of PEOPLE?

- How relevant for your feeling of SAFETY AND SECURITY is the presence of PARKED CARS?

- How relevant for your feeling of SAFETY AND SECURITY is the presence of OBSTACLES (bollards, etc)?

- How relevant for your feeling of SAFETY AND SECURITY is the level of NOISE in the street?

- How relevant for your feeling of SAFETY AND SECURITY is the PAVEMENT materials and its maintenance status?

- How relevant for your feeling of SAFETY AND SECURITY is the MORPHOLOGY OF THE STREET (open, surrounded by buildings, wide, narrow, etc)?

- How relevant for your feeling of SAFETY AND SECURITY is the HOUR OF THE DAY?

- How relevant for your feeling of SAFETY AND SECURITY is the REPUTATION OF THE NEIGHBOURHOOD?

- How relevant for your feeling of SAFETY AND SECURITY are YOUR OWN personal distractions (mobile phone, music, etc)?

- How relevant for your feeling of SAFETY AND SECURITY is the CULTURAL BACKGROUND OF THE NEIGHBOURHOOD?

- How relevant for your feeling of SAFETY AND SECURITY is the CRIMINALITY RATE of the neighbourhood?

- How relevant for your feeling of SAFETY AND SECURITY is YOUR OWN age?

- How each factor influences the respondent’s sense of safety and security,

- How each factor influences the respondent’s well-being.

- —mean value for average answer (safety/security and well-being);

- —standard deviation for average answer;

- —mean value for the safety/security score;

- —standard deviation for the safety/security score;

- —mean value for the well-being score;

- —standard deviation for the well-being score.

3. Results and Discussion

- (1)

- A formal definition and extension of the Basic Process of Lighting (BPL)

- (2)

- A field study to determine the main factors influencing people under lighting installations.

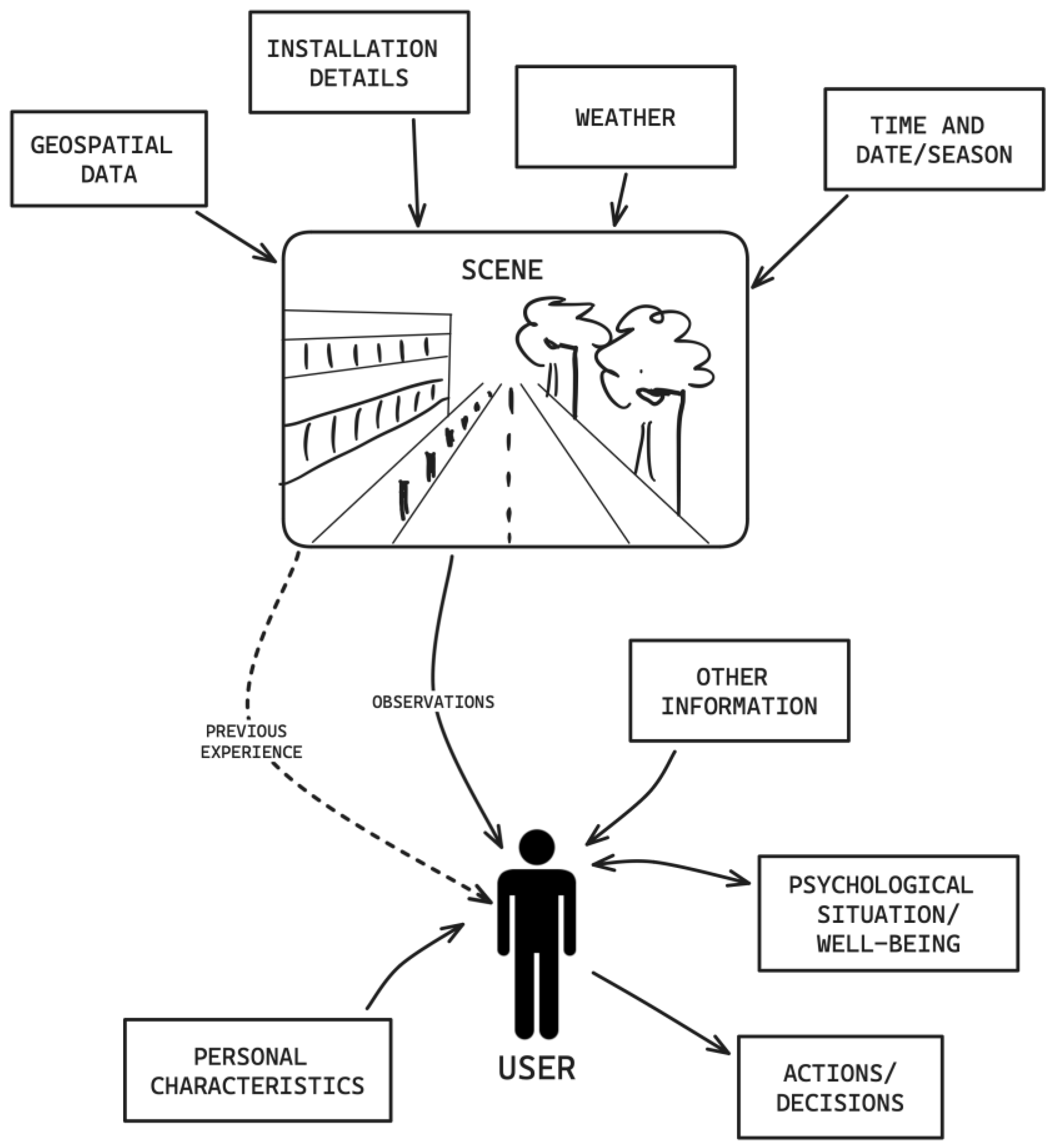

3.1. The Basic Process of Lighting (BPL)

- Luminaries emit luminous flux () with a given luminous intensity distribution I (, ).

- The pavement (visual plane) receives a given illuminance (E).

- The pavement partially reflects the illuminance according to its physical properties in terms of the amount of reflectance in each direction () and the spectral absorptance.

- A given luminance (), is directed towards the eyes of each observer.

- According to the visual input L, and other circumstances related to the situation, , each observer will have a physical and behavioural output, . Or, in a schematic way, .

3.2. Factors Impacting People under Public Lighting: Identification and Classification

- Light emission and propagation towards the visual working plane (A).

- The flux that is received and processed by the surface. The reflective and colorimetric properties of the surface where the illuminance is received process the luminous flux by absorbing and reflecting some or all wavelengths and reflecting them in one spatial pattern. The luminance towards the eye of each individual will determine his perception (B).

- Visual perception with physiological and neural processing of the luminous input received (C).

- Psychological processing and output, resulting from the perceived scene (D).

3.3. Scoring of Factors according to People Perception and Feelings

- The surveyed people are mainly concerned with criminality and threats from people.

- The six top factors have an exclusively social, sociological or economic nature, making up 31.6 per cent of the total. Fear of threats from other people is not an isolated high-ranked item, but a clear fact that arises from all of the perspectives and the modality of the questions.

- Only one factor of this nature (cultural background of the neighborhood) is surpassed by other factors of more technical or urban nature.

- The relevance of technical factors directly related to sight and visual performance is, by far, much lower than the relevance of social factors. This seems to be a clear indication of the initial hypothesis of this work: regulations on lighting should consider people’s feelings, even if it is not easy.

- is the normalized answer;

- is the raw answer.

4. Conclusions

- Defining the Basic Process of Lighting (BPL) as a chain of core stages going from the physical installation to the human output.

- Taking the classic BPL as a departing point and extending it to a human-centered perspective that can become a reference and guide for the design of lighting installations where the global dimensions of people and sustainable development really matter.

- Identifying all of the aspects that participate in the BPL with a survey, and finding their real weights in the perceived safety, security and well-being of the people developing their activities under the public lighting to suggest that the authorities implement these factors in future standards.

- The BPL is the central element in public lighting. It has been extended to a human-centered perspective, which allowed us to identify several questions that could be answered by street users.

- The number and variety of factors determining the feelings of safety and security and the well-being of the users of public lighting is much wider and more complex than considered in the design of cities and neighborhoods to date.

- According to the results obtained from the 133 survey participants, the fear of crime and potential offenses from other people, are, by far, the main concerns of people walking on the street at night. This feeling of safety is strongly attached to well-being; that is, feeling good, optimistic, and free of worries when walking along the street at night.

- Some factors objectively impacting the work of public lighting and hence, the visual perception of people, are perceived as less important. These are the presence of parked cars, obstacles, shadows, the weather and trees, which occupy the last positions almost exclusively. This result is surprising because of the lack of uniformity and visibility introduced by parked cars, trees and even the explicit presence of shadows impairing vision, but the respondents did not seem to worry very much about these factors.

- The high capacity of the human visual system to adapt to a very wide range of luminance can explain why the visual factors are below the social and socioeconomic ones in this survey. The results show that people are not very concerned about how they see when compared to conflict with other people.

- The conclusions above highlight the deep gap between objective visual circumstances and people’s preferences. It can be due to cultural or ideological background, personal experiences or other factors. No doubt, it is necessary to carry out more research in this field.

- In summary, the disagreement between the expectations from engineering and behavioral perspectives must lead designers, researchers, rulemaking bodies and public administrations to answer the one question of the highest importance: when defining installations of public lighting, must we consider just the classical parameters or take into account people’s preferences and intimate feelings of safety, security and well-being? According to the results obtained in this work, it seems clear that the correct choice is the second one.

- Potential biases due to national and cultural peculiarities of the surveyed people. This potential limitation will be checked and corrected if applicable, by distributing the translated version of the survey among people in other countries. Future research will focus on a multinational survey and the analysis of the data.

- Distractions or a lack of defined opinions among respondents while filling out the survey. Other strategies like professional survey takers asking people face to face and alleviating any doubts that might arise should be used in future research to collect subjective comments and other impressions from the people.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Painter, K. The impact of street lighting on crime, fear, and pedestrian street use. Secur. J. 1994, 5, 116–124. [Google Scholar]

- Boyce, P.R.; Eklund, N.H.; Hamilton, B.J.; Bruno, L.D. Perceptions of safety at night in different lighting conditions. Light. Res. Technol. 2000, 32, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalfin, A.; Hansen, B.; Lerner, J.; Parker, L. Reducing Crime Through Environmental Design: Evidence from a Randomized Experiment of Street Lighting in New York City. J. Quant. Criminol. 2022, 38, 127–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svechkina, A.; Trop, T.; Portnov, B.A. How Much Lighting is Required to Feel Safe When Walking Through the Streets at Night? Sustainability 2020, 12, 3133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portnov, B.A.; Saad, R.; Trop, T.; Kliger, D.; Svechkina, A. Linking nighttime outdoor lighting attributes to pedestrians’ feeling of safety: An interactive survey approach. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0242172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CEN/TR 13201-1; Road Lighting—Part 1: Guidelines on Selection of Lighting Classes. European Committee for Standarization: Brussels, Belgium, 2014.

- Van Bommel, W.J.M.; Tekelenburg, J. Visibility research for road lighting based on a dynamic situation. Light. Res. Technol. 1986, 18, 37–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ödemis, K.; Yener, C.; Olguntürk, N. Effects of Different Lighting Types on Visual Performance. Archit. Sci. Rev. 2004, 47, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rea, M.S.; Bullough, J.D.; Zhou, Y. A method for assessing the visibility benefits of roadway lighting. Light. Res. Technol. 2010, 42, 215–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremond, R. Visual performance models in road lighting: A historical perspective. Leukos 2020, 17, 212–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyce, P. Light, lighting and human health. Light. Res. Technol. 2022, 54, 101–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiro, M. Nonvisual Lighting Effects and Their Impact on Health and Well-Being. In Encyclopedia of Color Science and Technology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 1236–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, R.J.; Peirson, S.N.; Berson, D.M.; Brown, T.M.; Cooper, H.M.; Czeisler, C.A.; Figueiro, M.G.; Gamlin, P.D.; Lockley, S.W.; O’Hagan, J.B.; et al. Measuring and using light in the melanopsin age. Trends Neurosci. 2013, 37, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiro, M.G.; Nagare, R.; Price, L. Non-visual effects of light: How to use light to promote circadian entrainment and elicit alertness. Light. Res. Technol. 2018, 50, 38–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, L.; Figueiro, M. A 24-hour lighting scheme to promote alertness and circadian entrainment in railroad dispatchers on rotating shifts: A field study. Light. Res. Technol. 2021, 54, 441–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohashi, M.; Eto, T.; Takasu, T.; Motomura, Y.; Higuchi, S. Relationship between Circadian Phase Delay without Morning Light and Phase Advance by Bright Light Exposure the Following Morning. Clocks Sleep 2023, 5, 615–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haifler, Y.T.; Fisher-Gewirtzman, D. Spatial Parameters Determining Urban Wellbeing: A Behavioral Experiment. Buildings 2024, 14, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, T.; Yoshioka, Y. Effectiveness of Bollards in Deterring Pedestrians from Running into the Roadway. Hum. Factors Transp. 2022, 60, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iravani, S.N.; Sohrabi, S.A.; Gheitarani, N.; Dehghan, S. Providing a Pattern and Planning Method for Footpaths and Sidewalks to Protect Deteriorated and Vulnerable Urban Contexts. Eur. Online J. Nat. Soc. Sci. 2024, 13, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo-Martínez, A.; Peña-García, A. Influence of Groves on Daylight Conditions and Visual Performance of Users of Urban Civil Infrastructures. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouratidis, K. The impact of urban tree cover on perceived safety. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 44, 126434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdejo-Espinola, V.; Zahnow, R.; Fuller, R. Physical and social disorder, but not tree cover, contribute to lower perceptions of safety in urban green spaces. Research Square 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhulaifi, A.; Jamal, A.; Ahmad, I. Predicting Traffic Sign Retro-Reflectivity Degradation Using Deep Neural Networks. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 11595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, A.; Reza, I.; Shafiullah, M. Modeling retroreflectivity degradation of traffic signs using artificial neural networks. IATSS Res. 2022, 46, 499–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Commission on Environment and Development. Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Peña-García, A.; Salata, F. Indoor Lighting Customization Based on Effective Reflectance Coefficients: A Methodology to Optimize Visual Performance and Decrease Consumption in Educative Workplaces. Sustainability 2021, 13, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-García, A. Sustainability as the Key Framework of a Total Lighting. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-García, A. Towards Total Lighting: Expanding the frontiers of Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-García, A.; Salata, F. The perspective of Total Lighting as a key factor to increase the Sustainability of strategic activities. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierre, D. Long Live the Likert Scale: Designing survey questions. In Proceedings of the CACUSS 2023: Honour, Engage, Evolve, Niagara Falls, ON, Canada, 4–7 June 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arduini, A.; Pinneo, L.R. Properties of the retina in response to steady illumination. Arch. Ital. Biol. 1962, 100, 425–448. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pinneo, L.R.; Heath, R.G. Human visual system activity and perception of intermittent light stimuli. J. Neurol. Sci. 1967, 5, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Posner, M.I.; Snyder, C.R.R.; Davidson, B.J. Attention and the detection of signals. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 1980, 109, 160–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, A.G. Human Response to Visual Stimuli. In The Perception of Visual Information; Hendee, W.R., Wells, P.N.T., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Ridder, H.; Pont, S. The influence of lighting on visual perception of material qualities. In Proceedings of the SPIE—The International Society for Optical Engineering, San Francisco, CA, USA, 17 March 2015; Volume 9394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasauskaite, R.; Cajochen, C. Influence of lighting color temperature on effort-related cardiac response. Biol. Psychol. 2018, 132, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castilla, N.; Blanca-Giménez, V.; Pérez-Carramiñana, C.; Llinares, C. The Influence of the Public Lighting Environment on Local Residents’ Subjective Assessment. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siraji, M.A.; Lazar, R.R.; van Duijnhoven, J.; Schlangen, L.J.; Haque, S.; Kalavally, V.; Vetter, C.; Glickman, G.L.; Smolders, K.C.; Spitschan, M. An inventory of human light exposure behaviour. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 22151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, M. Impulsive Buying Behaviour Factors Generalisation and How to Improve. Lect. Notes Educ. Psychol. Public Media 2024, 39, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jedon, R.; Haans, A.; de Kort, Y. Pedestrians’ Alertness and Perceived Environmental Safety Under Non-Uniform Urban Lighting. Glob. Environ. Psychol. 2024, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Jägerbrand, A.K. New framework of sustainable indicators for outdoor LED (light emitting diodes) lighting and SSL (solid state lighting). Sustainability 2015, 7, 1028–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jägerbrand, A.K. Synergies and Trade-Offs Between Sustainable Development and Energy Performance of Exterior Lighting. Energies 2020, 13, 2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, S.; Kotulski, L.; Sędziwy, A.; Wojnicki, I. Graph-Based Computational Methods for Efficient Management and Energy Conservation in Smart Cities. Energies 2023, 16, 3252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Liu, Q.; Hang, T.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Cao, L. Integrating restorative perception into urban street planning: A framework using street view images, deep learning, and space syntax. Cities 2024, 147, 104791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathesh Raaj, R.; Vijayprasath, S.; Ashokkumar, S.R.; Anupallavi, S.; Vijayarajan, S.M. Energy Management System of Luminosity Controlled Smart City Using IoT. EAI Endorsed Trans. Energy Web 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielinska-Dabkowska, K.M.; Bobkowska, K. Rethinking Sustainable Cities at Night: Paradigm Shifts in Urban Design and City Lighting. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnejem, M.; Rehan, G.; Taghipour, M.; Alhabsi, F. Urban Street Principles as an Effective Strategy for Improving Environmental Sustainability. In Proceedings of the Oman Conference for Environmental Sustainability, Muscat, Oman, 26–28 February 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Shavkatov, S. Adaptive Illumination: Designing a Smart Street Lighting System for Sustainable Urban Environments. MATRIX Acad. Int. Online J. Eng. Technol. 2023, 6, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deodati, A.; Petrachi, E.; Vendramin, G.; Cosma, L.; Bene, P. Urban Lighting: An Innovative Solution, Eco-Sustainable and Resistant to Corrosion. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1099, 012016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, W.; Wen, Y.; Chen, Z.-L. Sustainable Development of Urban Lighting Systems. J. Cent. South Univ. Technol. 2006, 13, 17–20. [Google Scholar]

| Factor | Category |

|---|---|

| Criminality (Real) | D |

| Cultural background | C, D |

| Personal distractions (music, messaging) | C, D |

| Fame of area | C, D |

| Hour | C, D |

| Morphology of zone | A, B, D |

| Nature and status of pavement | B |

| Noise | C |

| Other obstacles | A, B, D |

| Parked cars | A, B, D |

| Presence of people | A, B, C, D |

| Recent incidents | C, D |

| Shadows | A, B, C, D |

| Socioeconomic level area | D |

| Spectral Power Distribution | A, B, C |

| Traffic | A, B, C, D |

| Trees | A, B, D |

| Weather | A, B, C, D |

| Factor | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criminality rate of neighborhood | 4.45 | 0.76 | 4.53 | 0.77 | 4.37 | 0.87 |

| Hour of the day | 4.18 | 0.82 | 4.50 | 0.81 | 3.87 | 1.15 |

| Recent incidents | 4.13 | 0.90 | 4.26 | 0.95 | 3.99 | 1.09 |

| Reputation of neighborhood | 4.11 | 0.82 | 4.23 | 0.87 | 3.99 | 0.93 |

| Socioeconomic level of neighborhood | 3.98 | 0.85 | 4.22 | 0.89 | 3.75 | 1.08 |

| Other people | 3.89 | 0.82 | 4.02 | 0.93 | 3.75 | 0.93 |

| Morphology of the street | 3.78 | 0.82 | 3.94 | 0.89 | 3.62 | 1.00 |

| Pavement materials and state | 3.71 | 0.97 | 3.74 | 1.07 | 3.68 | 1.09 |

| Color of light | 3.68 | 0.91 | 3.59 | 1.07 | 3.77 | 0.99 |

| Noise | 3.63 | 0.81 | 3.49 | 0.93 | 3.77 | 1.10 |

| Cultural background of neighborhood | 3.59 | 0.94 | 3.61 | 1.05 | 3.56 | 1.05 |

| Traffic | 3.56 | 0.92 | 3.82 | 1.04 | 3.31 | 1.23 |

| Trees | 3.49 | 0.87 | 3.18 | 1.09 | 3.80 | 1.09 |

| Weather | 3.44 | 0.83 | 3.26 | 1.01 | 3.61 | 1.04 |

| Own age | 3.44 | 1.02 | 3.49 | 1.10 | 3.39 | 1.19 |

| Personal distractions | 3.41 | 1.04 | 3.48 | 1.16 | 3.35 | 1.12 |

| Shadows | 3.31 | 0.98 | 3.44 | 1.12 | 3.18 | 1.15 |

| Parked cars | 3.06 | 0.85 | 3.17 | 0.96 | 2.95 | 1.06 |

| Obstacles | 3.05 | 1.07 | 3.04 | 1.15 | 3.07 | 1.23 |

| Factor | Total | Safety and Security | Well-Being |

|---|---|---|---|

| Criminality rate of neighborhood | 1.47 | 1.56 | 1.41 |

| Hour of the day | 1.23 | 1.54 | 1.05 |

| Recent incidents | 1.20 | 1.35 | 1.14 |

| Reputation of neighborhood | 1.16 | 1.27 | 1.08 |

| Socioeconomic level of neighborhood | 1.04 | 1.27 | 0.92 |

| Other people | 0.97 | 1.11 | 0.86 |

| Pavement materials and state | 0.88 | 0.92 | 0.88 |

| Morphology of the street | 0.86 | 1.02 | 0.79 |

| Color of light | 0.80 | 0.79 | 0.89 |

| Cultural background of neighborhood | 0.74 | 0.80 | 0.77 |

| Noise | 0.73 | 0.64 | 0.95 |

| Traffic | 0.72 | 0.95 | 0.67 |

| Own age | 0.67 | 0.73 | 0.68 |

| Personal distractions | 0.65 | 0.75 | 0.62 |

| Trees | 0.64 | 0.50 | 0.95 |

| Weather | 0.58 | 0.53 | 0.79 |

| Shadows | 0.56 | 0.68 | 0.53 |

| Obstacles | 0.46 | 0.45 | 0.53 |

| Parked cars | 0.35 | 0.43 | 0.35 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Peña-García, A.; Castillo-Martínez, A.; Ernst, S. The Basic Process of Lighting as Key Factor in the Transition towards More Sustainable Urban Environments. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4028. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16104028

Peña-García A, Castillo-Martínez A, Ernst S. The Basic Process of Lighting as Key Factor in the Transition towards More Sustainable Urban Environments. Sustainability. 2024; 16(10):4028. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16104028

Chicago/Turabian StylePeña-García, Antonio, Agustín Castillo-Martínez, and Sebastian Ernst. 2024. "The Basic Process of Lighting as Key Factor in the Transition towards More Sustainable Urban Environments" Sustainability 16, no. 10: 4028. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16104028

APA StylePeña-García, A., Castillo-Martínez, A., & Ernst, S. (2024). The Basic Process of Lighting as Key Factor in the Transition towards More Sustainable Urban Environments. Sustainability, 16(10), 4028. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16104028