Bottom-Up Initiatives for Sustainable Mountain Development in Italy: An Interregional Explorative Survey

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Mountain Sustainable Development in Italy

2.2. Bottom-Up Initiatives for Sustainable Development

3. Materials and Methods

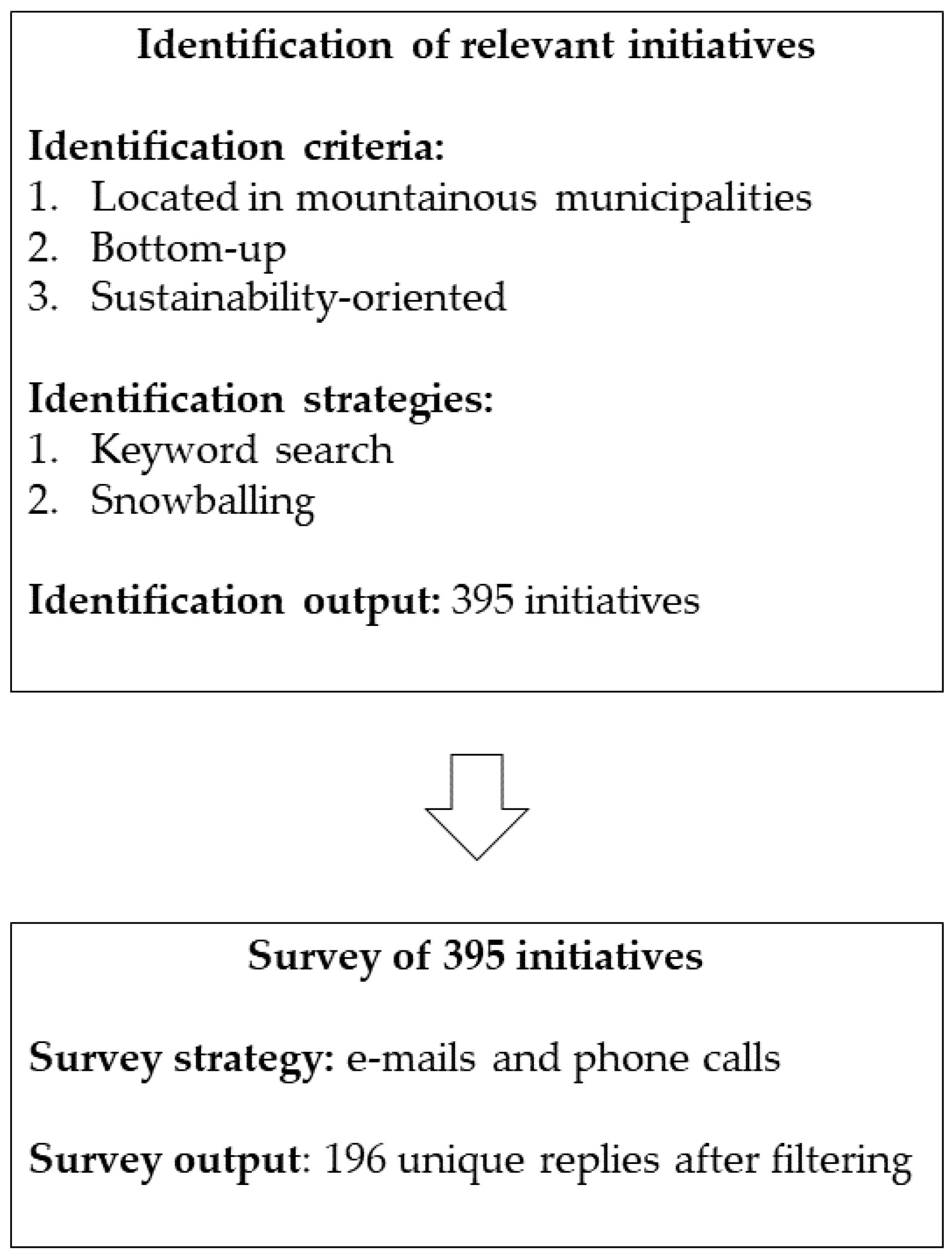

3.1. Database Construction

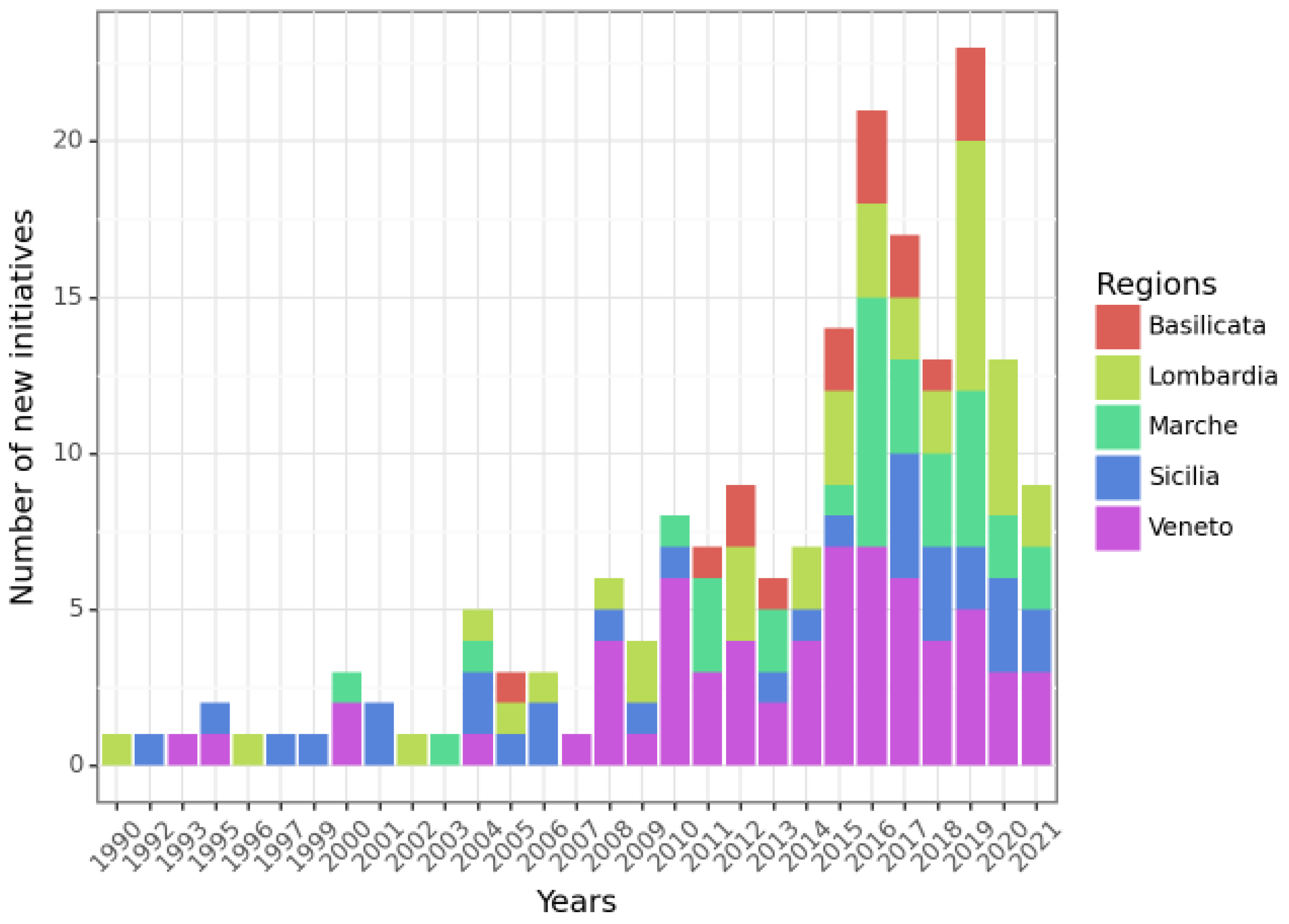

- What is their spread across regions, and what trends do they show over time?

- What type of economic activity is carried out, what are the main characteristics and challenges they must face, and what are the long-term perspectives?

- Are there common visions and values across initiatives in different regions?

- How can their contributions to the promotion of sustainable local development be assessed?

3.2. Survey Preparation and Analysis

4. Results

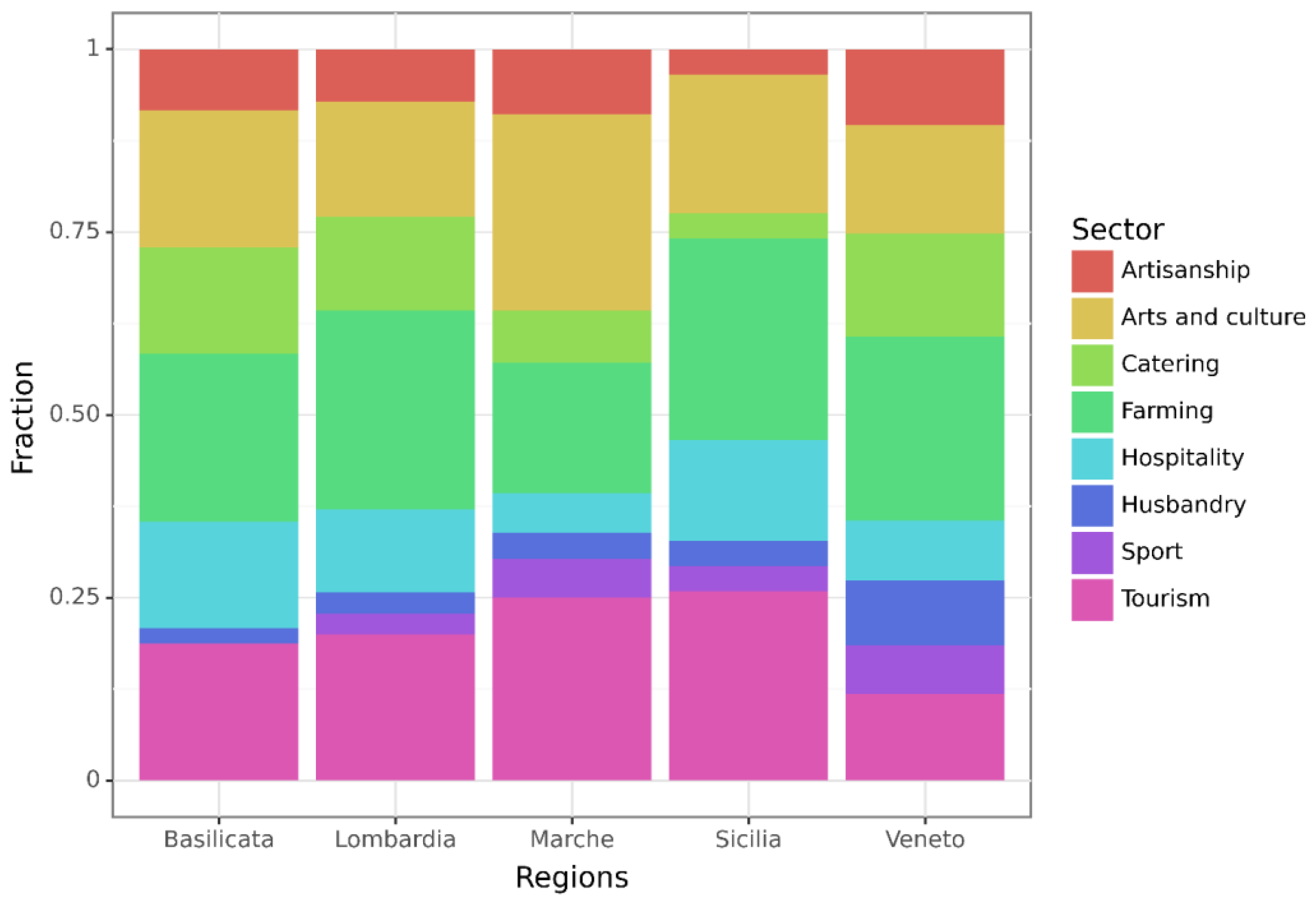

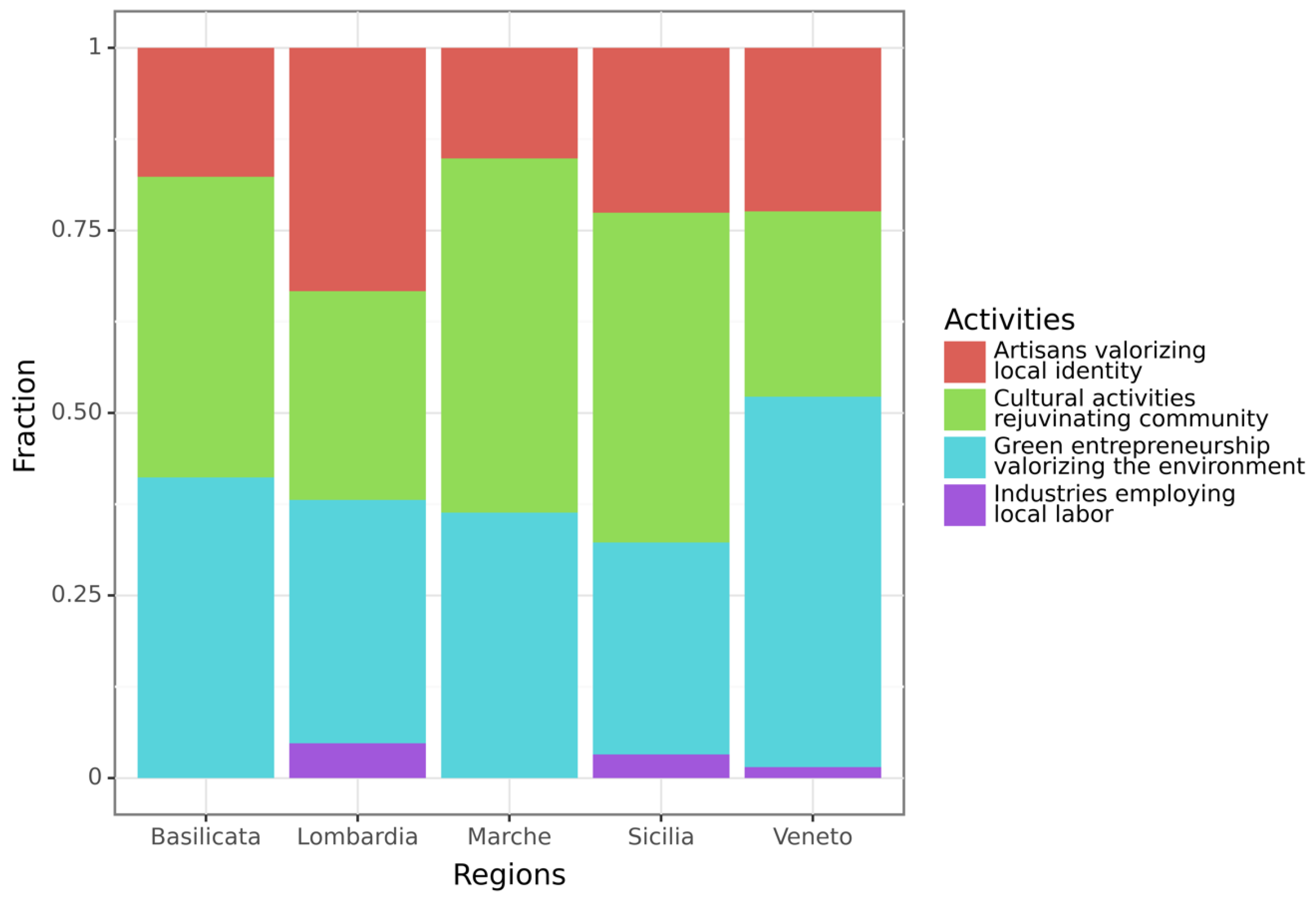

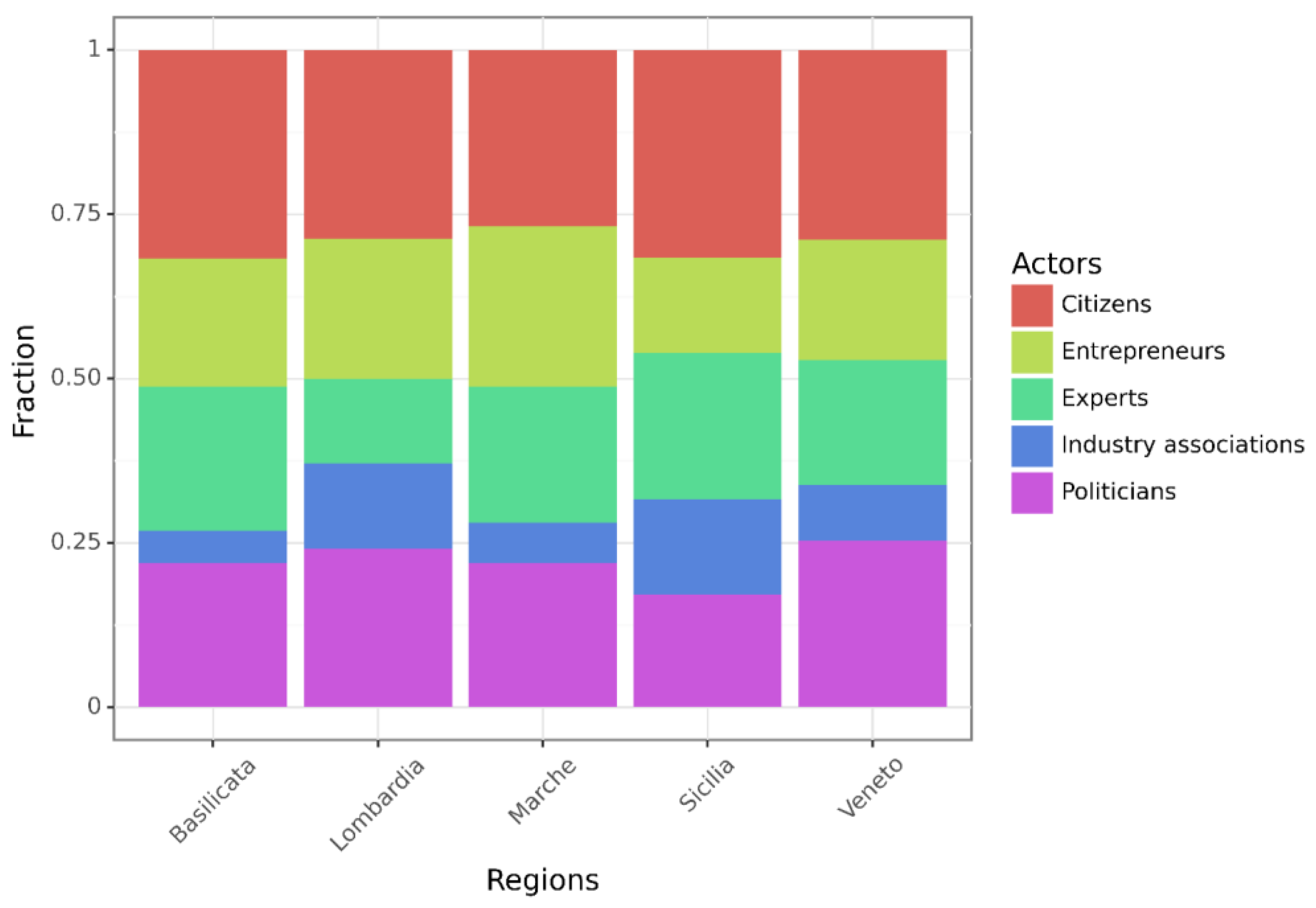

4.1. Bottom-Up Sustainable Initiatives’ Profile

4.2. Hindering and Supporting Factors in Bottom-Up Initiatives’ Success and Survival

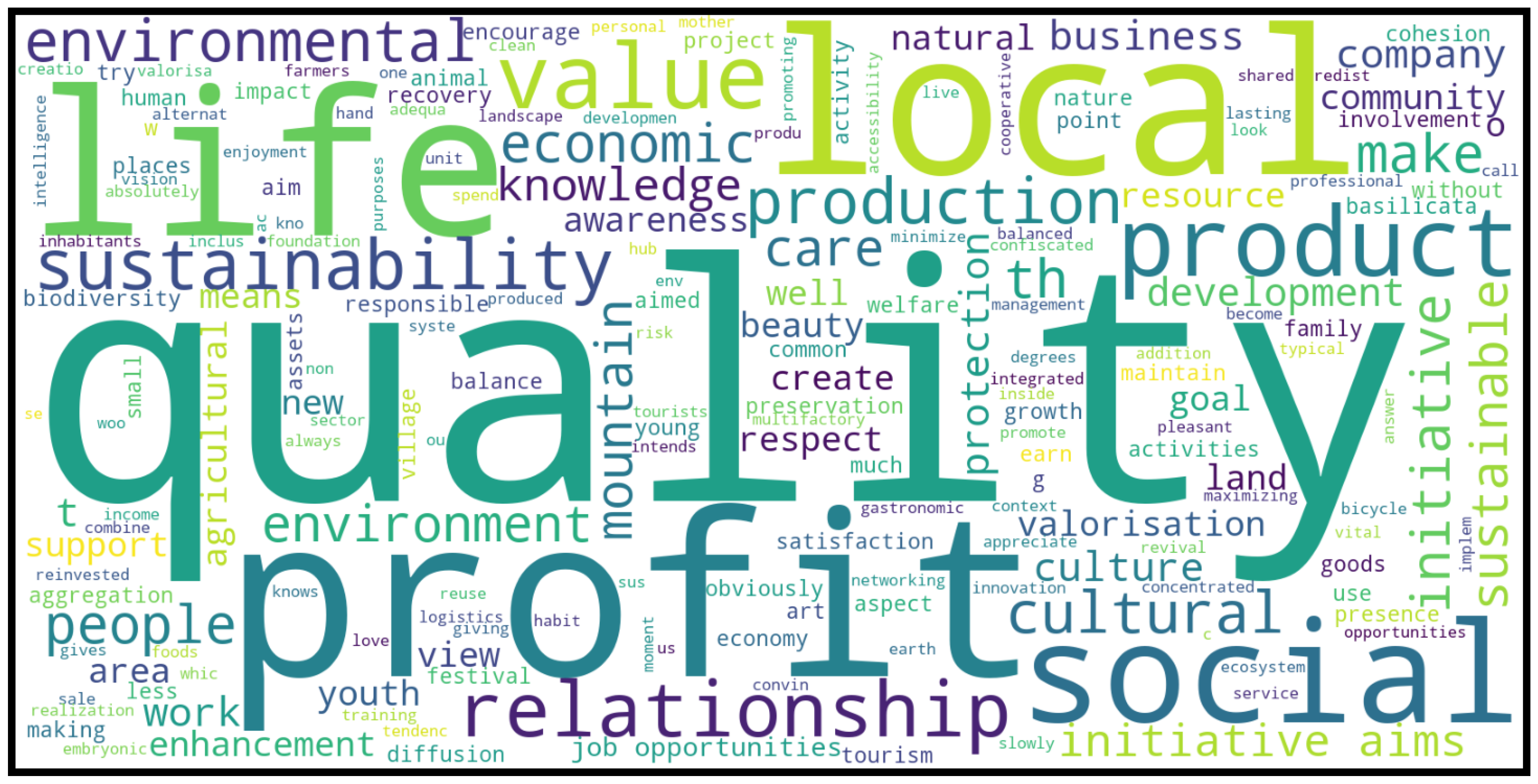

4.3. Bottom-Up Initiatives’ Sustainable Mountain Development Vision

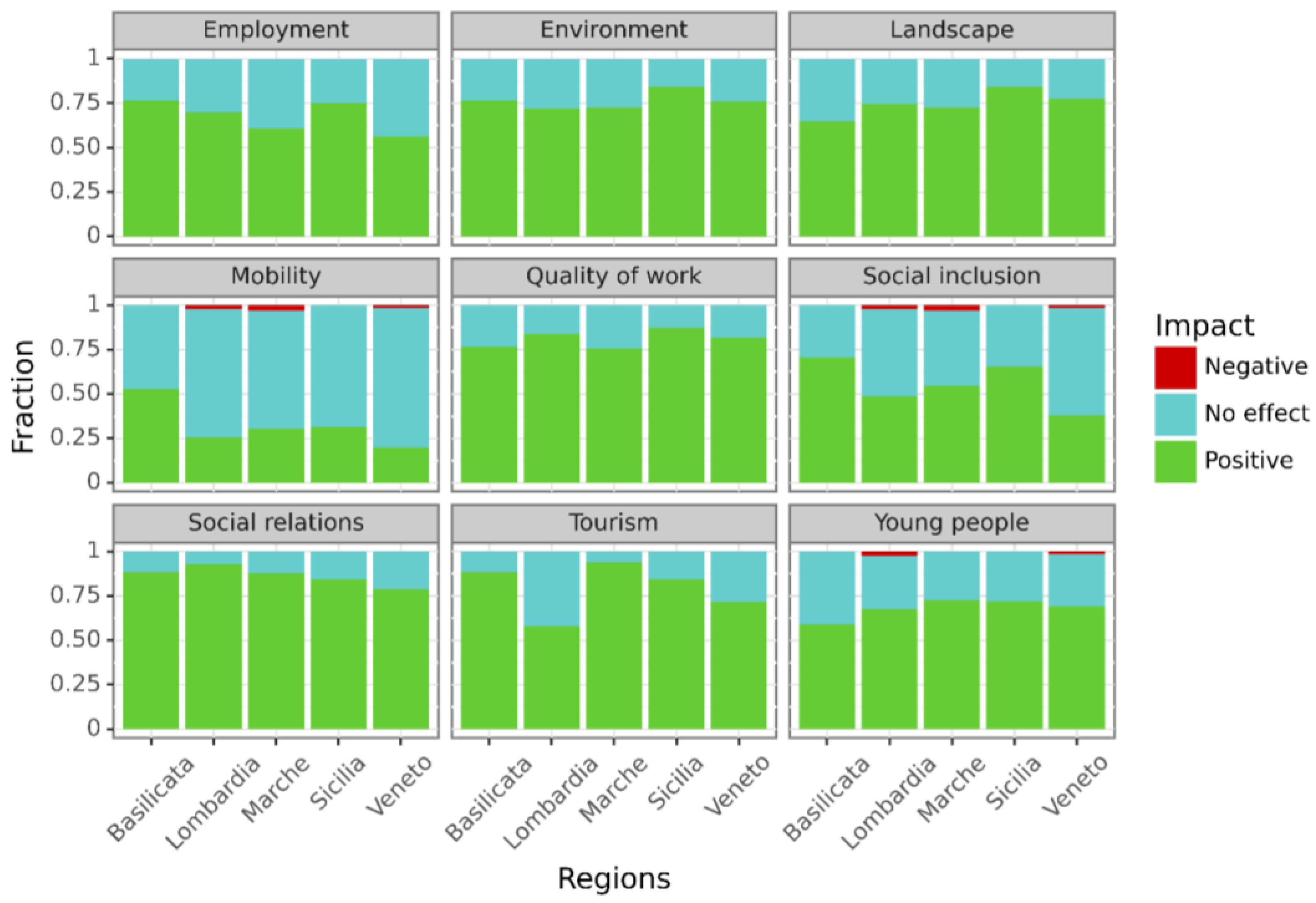

4.4. Bottom-Up Initiatives’ Impact Self-Assessment

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Questionnaire “We, Pioneers of Mountain Care”

- What is the name of the initiative you are implementing in the mountain area?

- What is the legal form of the initiative? Mark only one option.

- Sole Proprietorship; Simple Partnership; General Partnership; Limited Partnership with Shares; Limited Partnership; Limited Liability Company; Joint-Stock Company; Cooperative Association; Public Entity; Other.

- What role do you play within the initiative?

- Where is the initiative based (street, house number, municipality)? If the activity takes place in more than one municipality, indicate them.

- What is the business sector of the initiative? Select all applicable options.

- Agriculture; Livestock; Herding; Hospitality; Gastronomy; Arts and Culture; Handicrafts; Sports; Tourism; Services; Public Administration; Other.

- What is the starting year of the initiative?

- Is/was the founder/originator of the initiative a “mountain man”? Mark only one option.

- No; Yes.

- Since the initiative was started, have there been generational changes in management? Mark only one option.

- No; Yes, but the change in management did not affect the initiative; Yes, and the change in management did affect the initiative.

- Are young people (under 30) involved in the initiative? Mark only one option.

- No; Yes, but they make a negligible contribution; Yes, and they make a major contribution; Yes, and they make an essential contribution.

- Are women involved in the initiative? Mark only one option.

- No; Yes, but they make a negligible contribution; Yes, and they make a major contribution; Yes, and they make an essential contribution.

- If the initiative targets particular segments of the population, could you identify them from the following? Select all applicable options.

- Elderly; Disabled; Women; Youth; Migrants; Other.

- In pursuing this initiative, the main support (e.g., economic, psychological, local, legal, social) came from:

- In pursuing this initiative, the main obstacle (e.g., economic, psychological, local, legal, social) has been:

- How do you envision the initiative developing 10 years from now?

- What are the main purposes the initiative seeks to pursue? Select all applicable options.

- Environmental; Economic; Social.

- Was it necessary to turn to the banking system to meet investments? Mark only one option.

- No; Yes, but requests were not fulfilled; Yes, and requests were fulfilled in part; Yes, and requests were fulfilled in full.

- Has the initiative received any public contributions? Select all applicable options.

- No; Yes, the initiative received local contributions; Yes, the initiative received regional contributions; Yes, the initiative received national contributions; Yes, the initiative received European contributions.

- Have financial resources been raised through crowdfunding campaigns? Mark only one option.

- No; Yes; I am not familiar with these campaigns.

- Do you think crowdfunding could be useful for the initiative?

- Does the initiative aspire to combine tradition and innovation? Mark only one option.

- No; Yes.

- If you answered positively to the previous question, could you indicate what tradition you are carrying on and what element of innovation you are experimenting with?

- Is the initiative collaborating with other actors in the area (other associations, businesses, public agencies, etc.)?

- No; Yes.

- If you answered positively to the previous question, could you indicate which actors?

- In your opinion, would it be possible to carry out the initiative with the same goals and results in a different mountain setting?

- Could you justify your previous answer?

- In your opinion, would it be possible to implement the initiative with the same aims and results in a non-mountain setting? Mark only one option.

- No; Yes; Don’t know.

- Could you justify your previous answer?

- Is caring for the mountain landscape one of the values of the initiative?

- For each of the following, could you tell whether the initiative is having spillover effects? Mark only one option (Positive; No effect; Negative; Not applicable) per line.

- Local employment; Social relations among villagers; Quality of the environment; Sustainable tourism; Professional opportunities for young people to stay in the mountains; Local mobility; Quality of the landscape; Quality of your work and the people you work with; Social inclusion of vulnerable groups.

- Generally, economic activities pursue profit maximization; what does this initiative want to “maximize”?

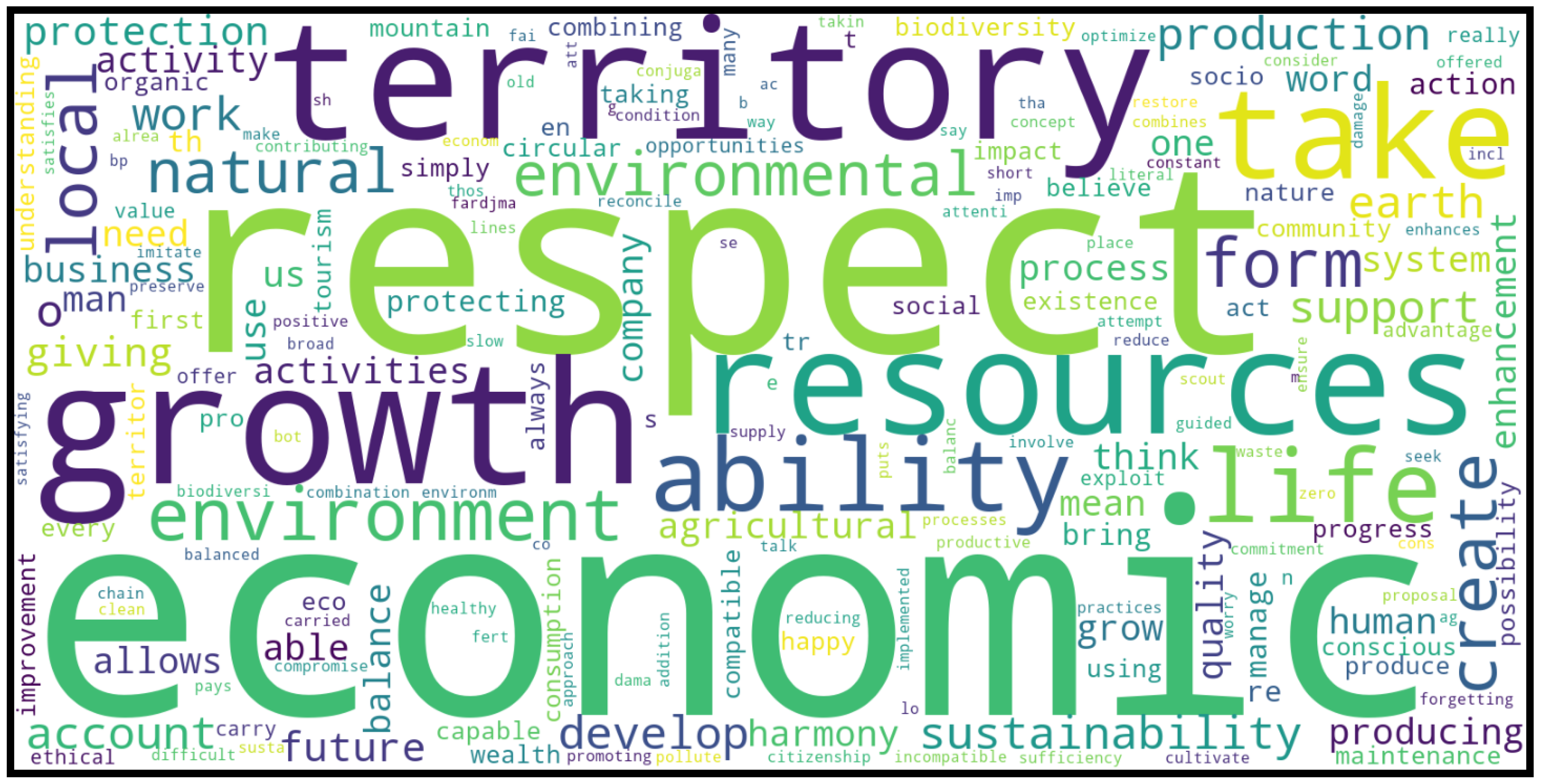

- Could you describe, in a few words, what “sustainable development” is to you?

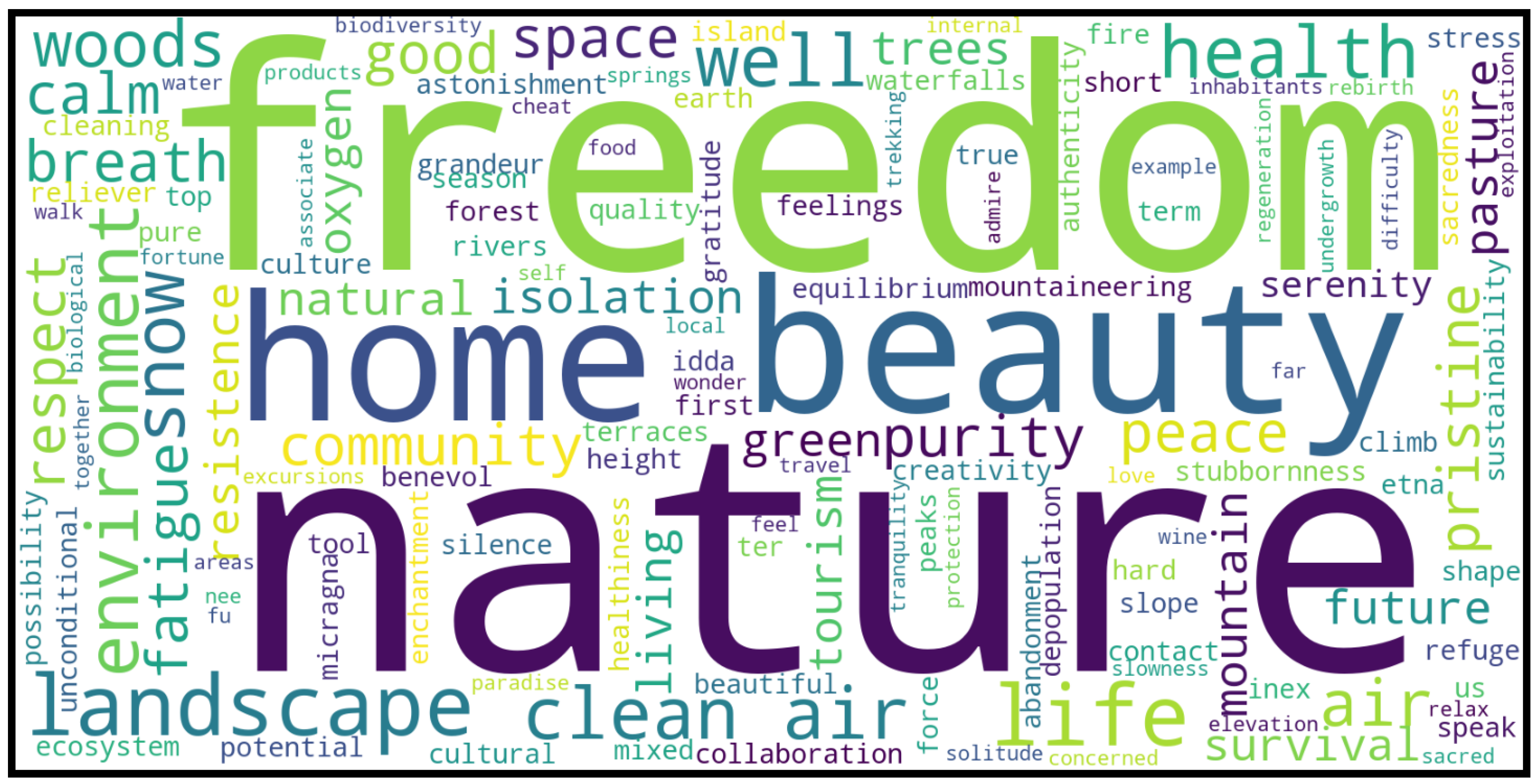

- What is the first word you associate with the term “mountain”?

- What does the area in which the initiative takes place mean to you?

- In your opinion, what is the most important thing likely to promote the sustainable development strategy of the area where the initiative is implemented? Select the main one.

- “Green” business activities that can enhance the environment and mountain landscape; Industrial/commercial activities that employ local workforce; Craft activities that enhance local knowledge and identities; Artistic and cultural activities that can weave community networks and open up new prospects for tourism.

- In general, when selecting projects with local impact, which aspect do you think is most relevant? Mark only one option.

- Creation of new jobs; Environmental protection; Preservation of local identity and historical and cultural heritage of the community.

- In the local development process, which actors in the area do you think should be involved? Select the two most important ones.

- Politicians and administrators; Entrepreneurs; Citizens; Industry associations; Experts/scholars/researchers; Other.

- The survey is finished, we thank you for your time. We would love to stay in touch to share future developments in our research project. Would you be interested in being contacted again? Please mark only one option.

- No; Yes.

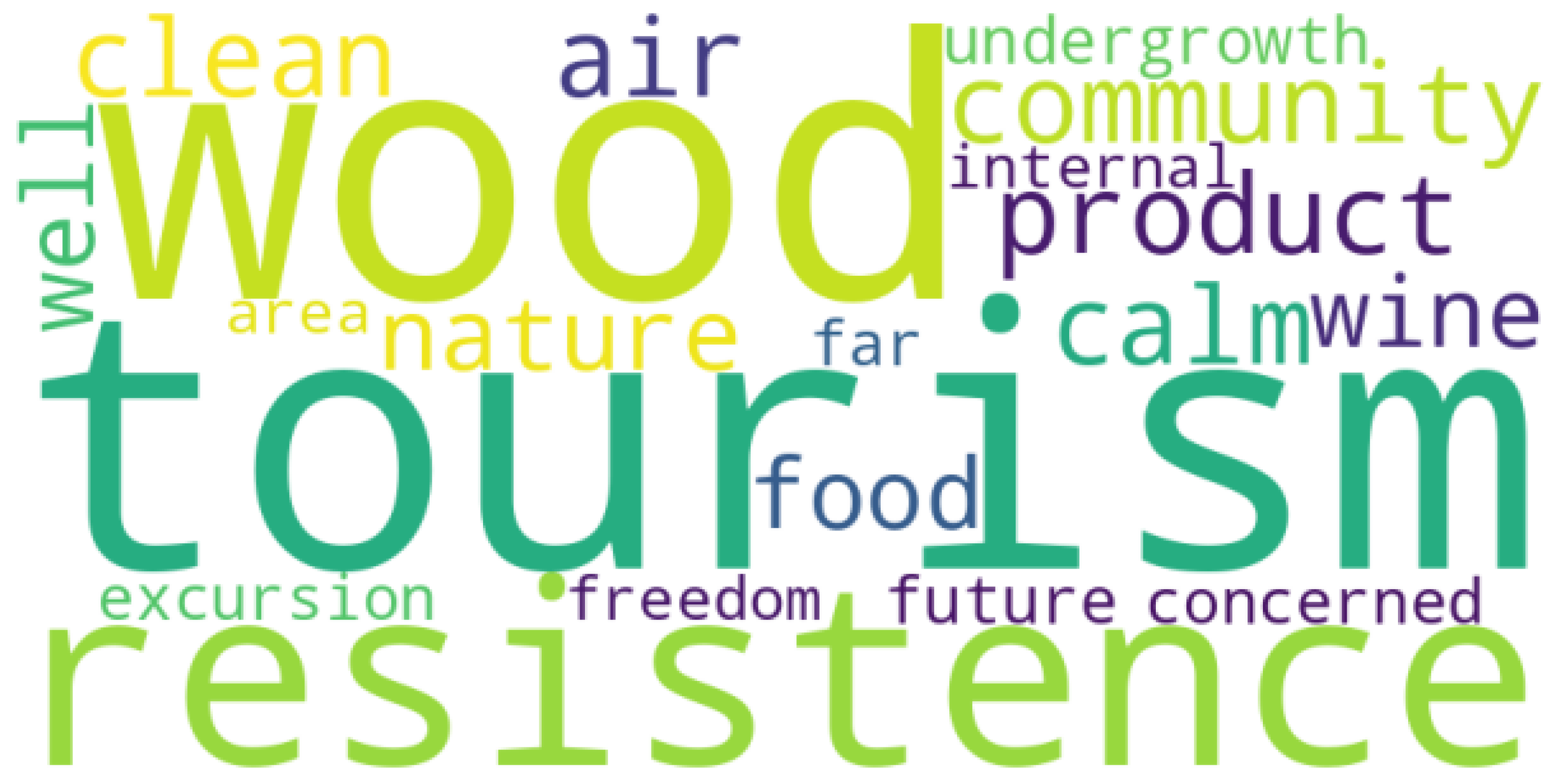

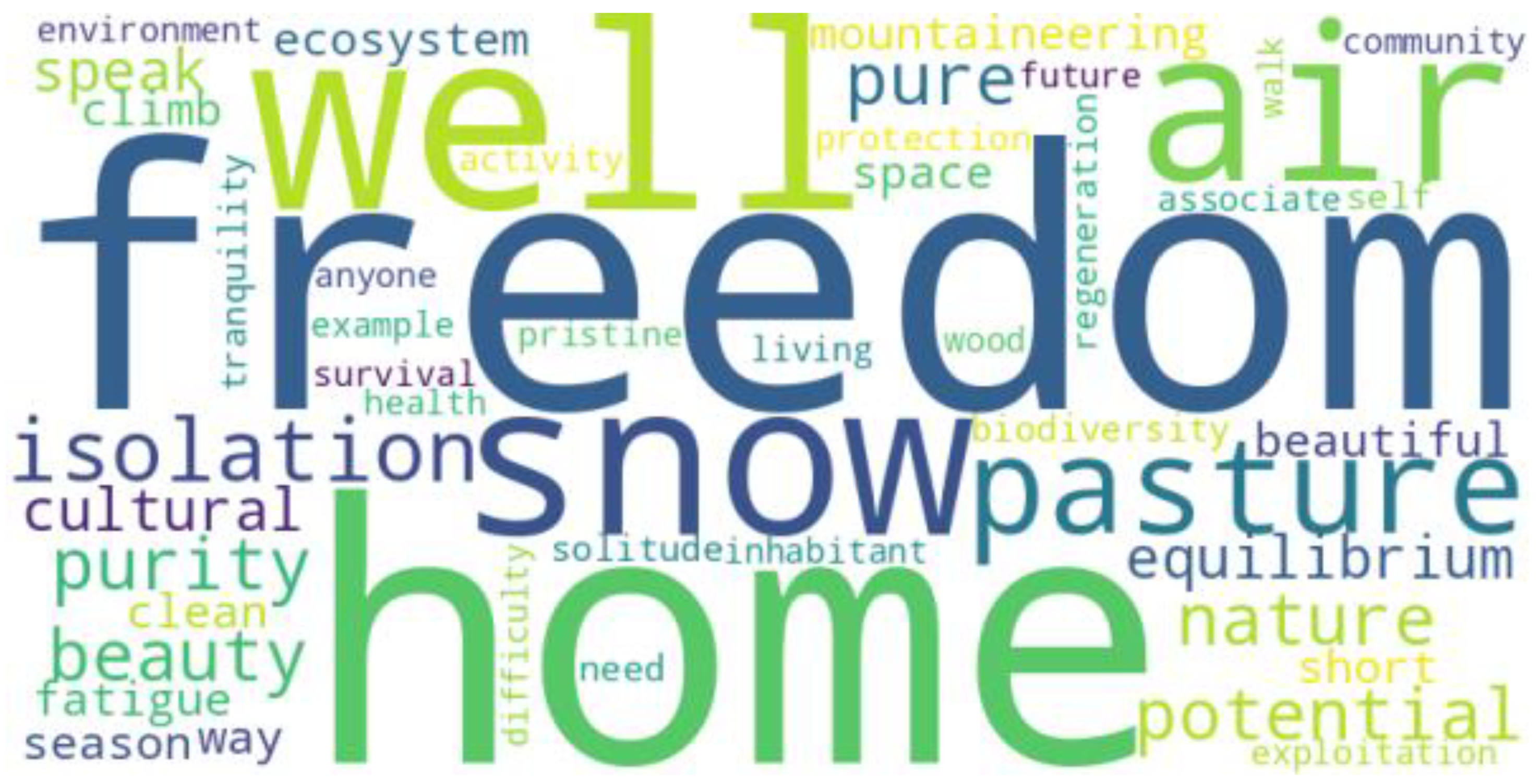

Appendix B. Wordclouds for Answers to “What Terms Do You Associate with Mountains?”

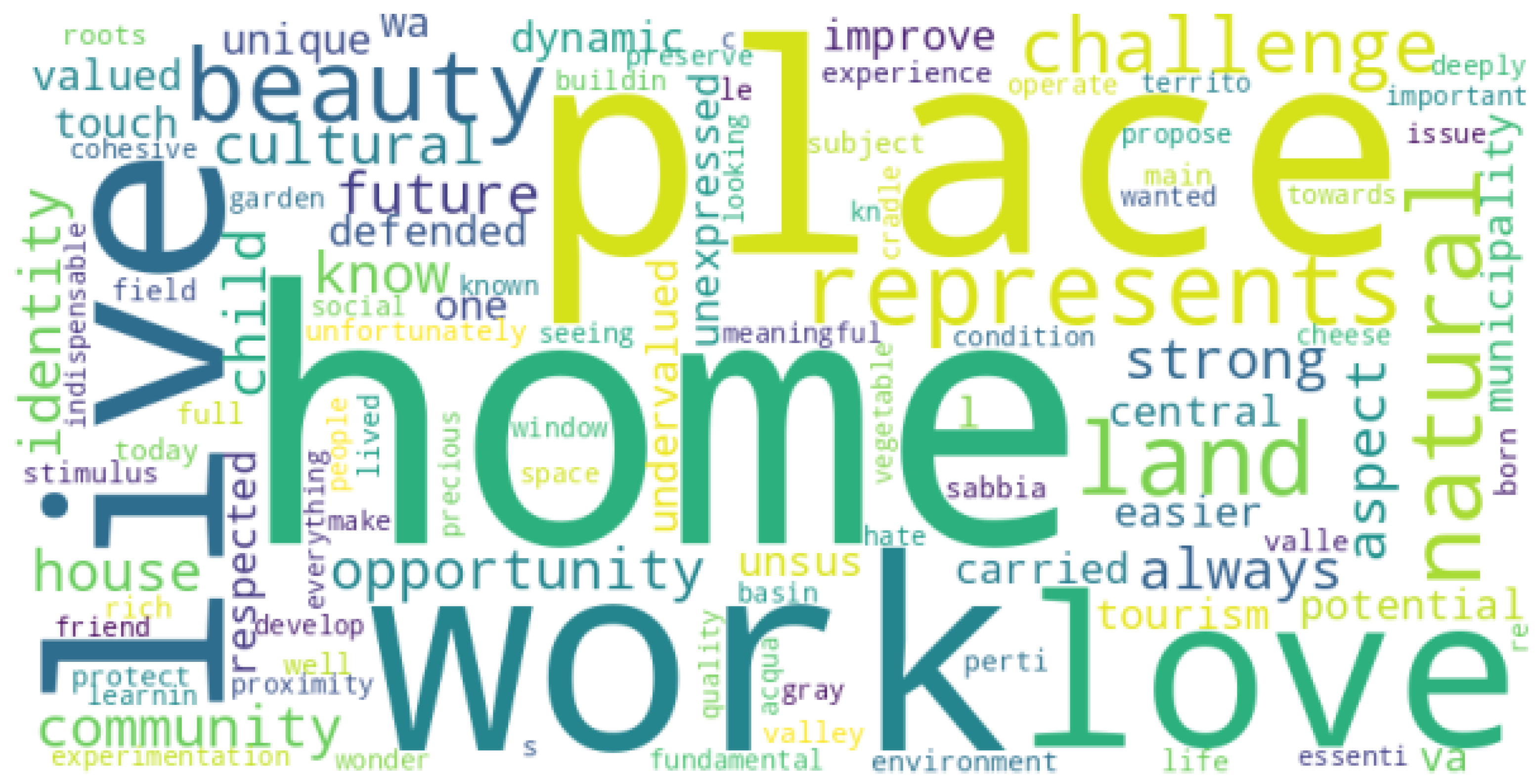

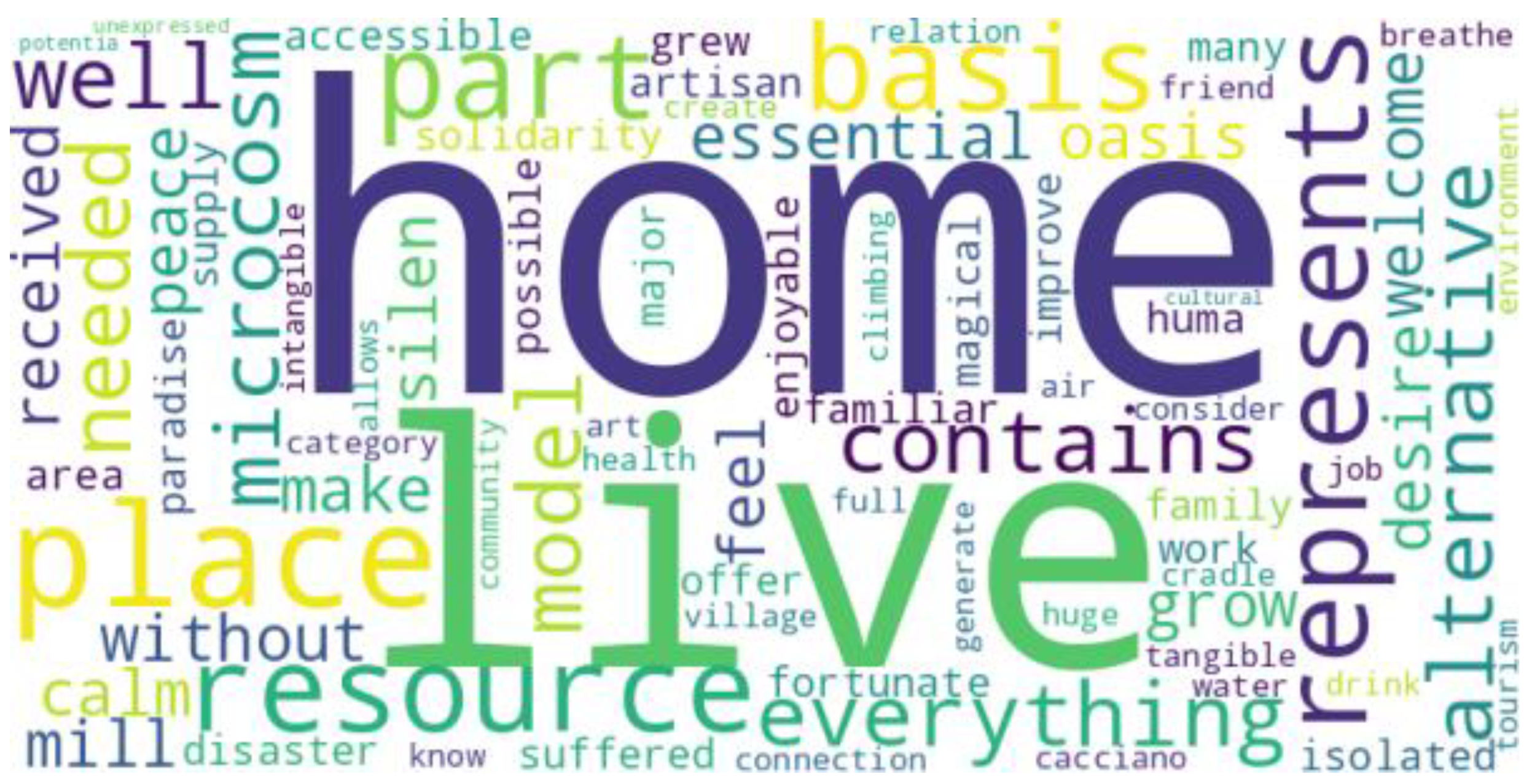

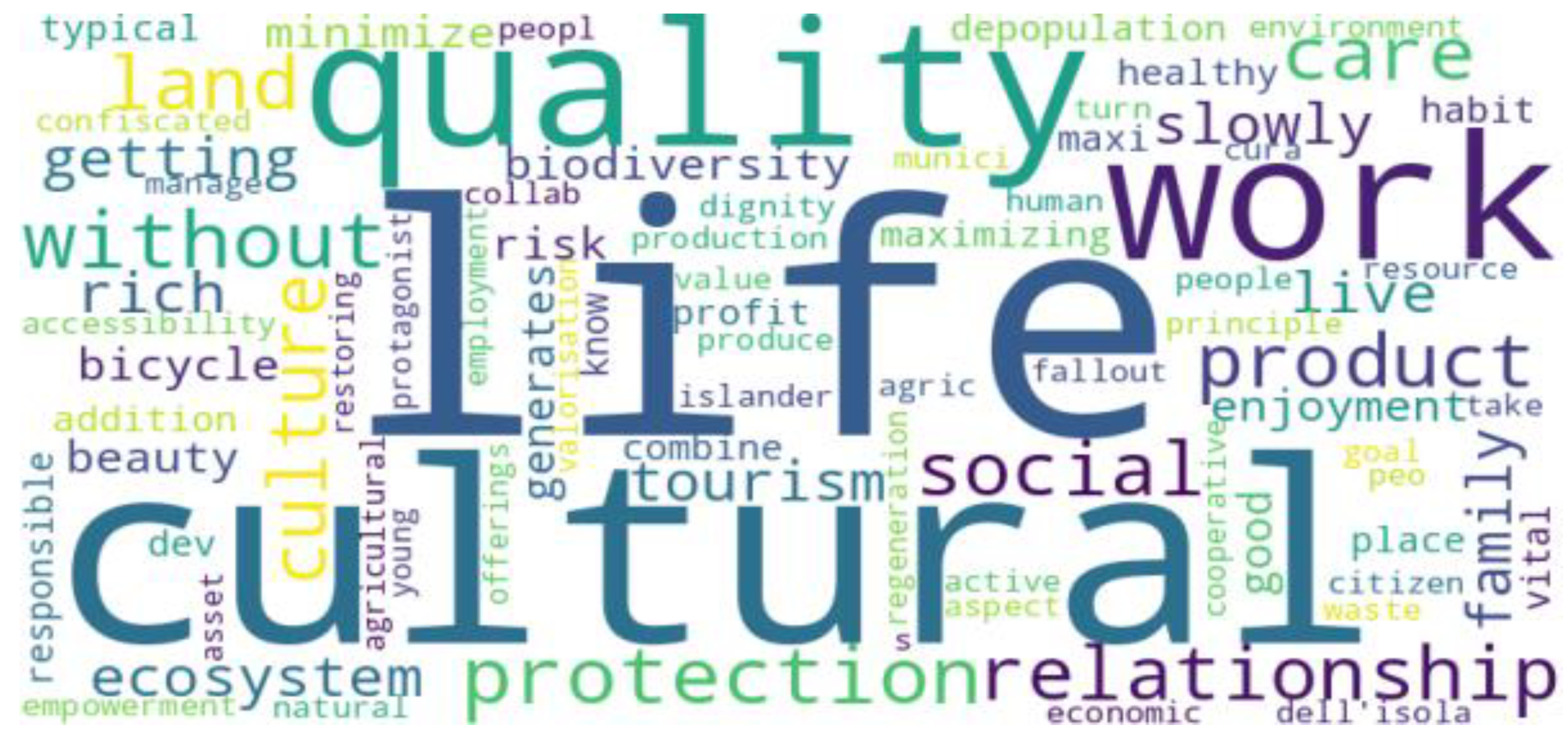

Appendix C. Wordclouds for Answers to “What Does the Territory of the Initiative Represent for You?”

Appendix D. Wordclouds for Answers to “How Do You Think the Initiative Will Look Like in Ten Years?”

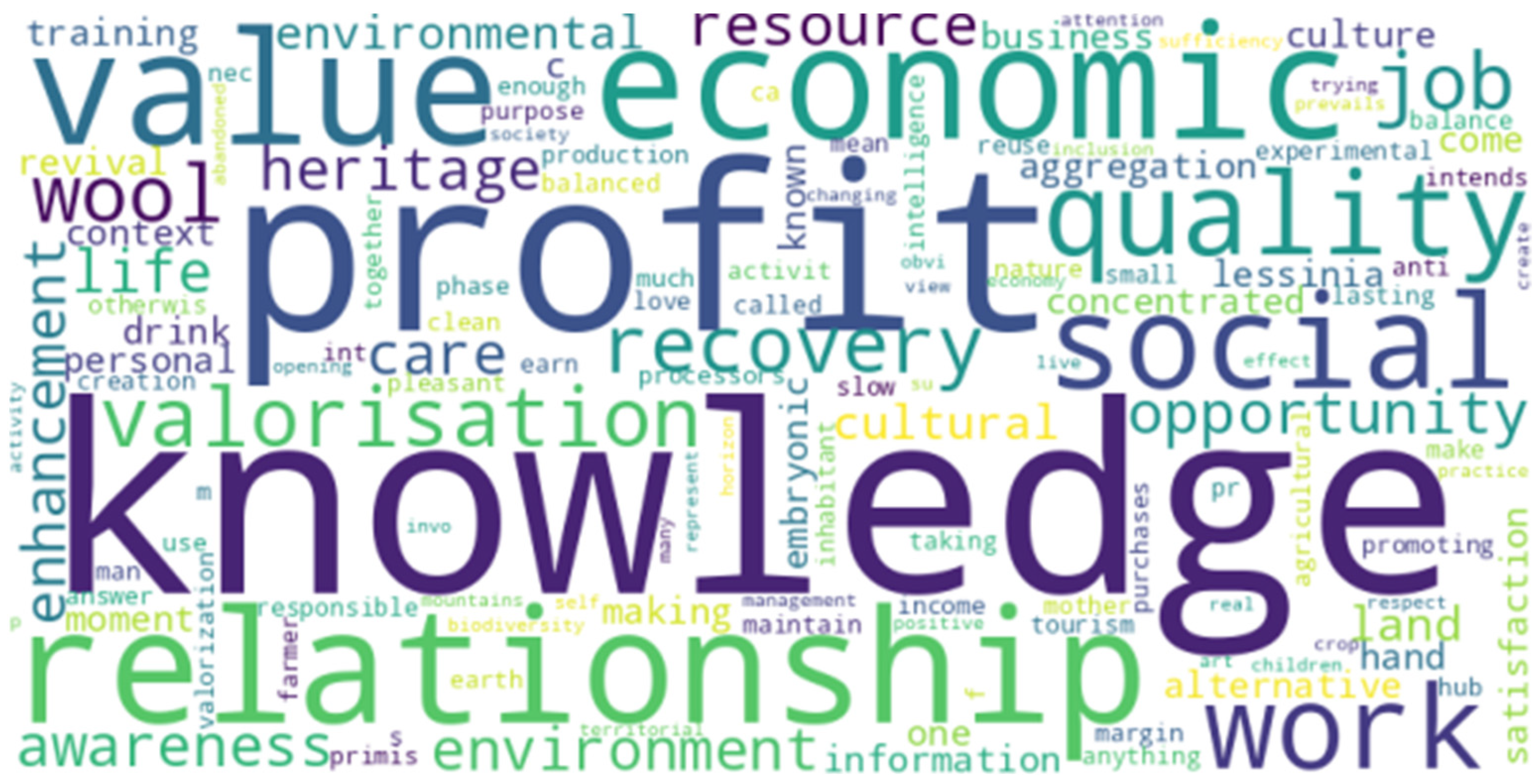

Appendix E. Wordclouds for Answers to “What Terms Do You Associate with Sustainable Development?”

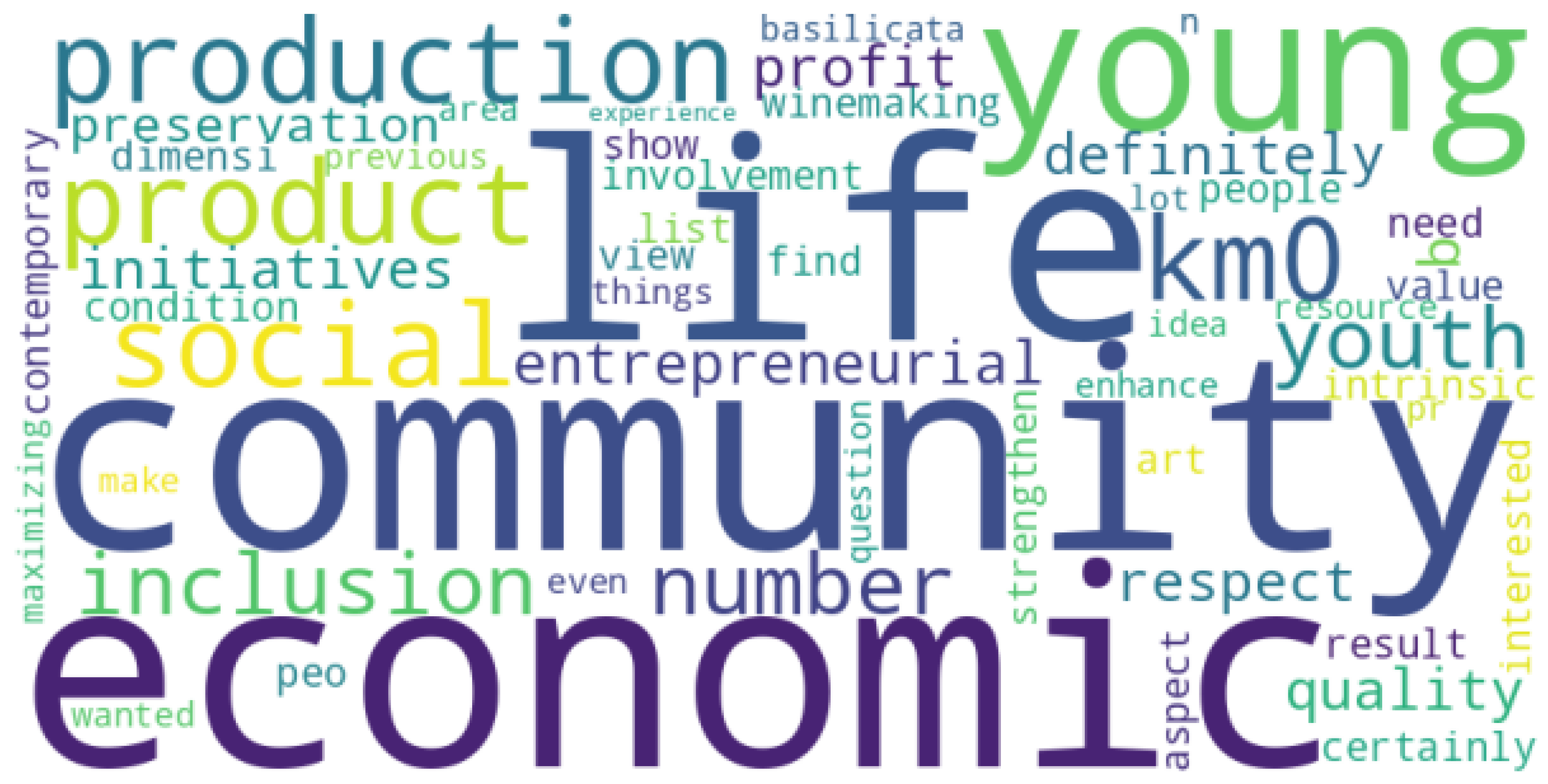

Appendix F. Wordclouds for Answers to “What Does Your Initiative Aim to Maximise?”

References

- Gretter, A.; Ciolli, M.; Scolozzi, R. Governing Mountain Landscapes Collectively: Local Responses to Emerging Challenges within a Systems Thinking Perspective. Landsc. Res. 2018, 43, 1117–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerea, G.; Marcantoni, M. La Montagna Perduta: Come La Pianura Ha Condizionato Lo Sviluppo Italiano; FrancoAngeli: Milan, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Revelli, N.; Fazio, M. Il Mondo dei Vinti: Testimonianze di Vita Contadina; Einaudi: Turin, Italy, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Varotto, M. Montagne Di Mezzo: Una Nuova Geografia; Einaudi: Torino, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- De Rossi, A. Riabitare l’Italia: Le Aree Interne tra Abbandoni e Riconquiste; Donzelli Editore: Rome, Italy, 2018; ISBN 9788868439330. [Google Scholar]

- Barca, F. Disuguaglianze Territoriali e Bisogno Sociale; Fondazione Ermanno Gorrieri: Modena, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Barca, F.; Casavola, P.; Lucatelli, S. Strategia Nazionale per le Aree Interne: Definizione, Obiettivi, Strumenti e Governance/[a Cura di Fabrizio Barca, Paola Casavola e Sabrina Lucatelli]; Ministero dello Sviluppo Economico, Dipartimento per lo Sviluppo e la Coesione Economica, Unità di Valutazione degli Investimenti Pubblici: Rome, Italy, 2014.

- Lopolito, A.; Sisto, R.; Barbuto, A.; Da Re, R. What Is the Impact of LEADER on the Local Social Resources? Some Insights on Local Action Group’s Aggregative Role. Riv. Econ. Agrar. 2015, 70, 55–75. [Google Scholar]

- Vitale Brovarone, E.; Cotella, G. La Strategia Nazionale per Le Aree Interne: Una Svolta Place-Based per Le Politiche Regionali in Italia. Arch. Studi Urbani Reg. 2020, 3, 22–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckerberg, K.; Bjärstig, T.; Zachrisson, A. Incentives for Collaborative Governance: Top-Down and Bottom-Up Initiatives in the Swedish Mountain Region. Mt. Res. Dev. 2015, 35, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gretter, A.; Torre, C.D.; Maino, F.; Omizzolo, A. New Farming as an Example of Social Innovation Responding to Challenges of Inner Mountain Areas of Italian Alps. Rev. Geogr. Alp. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Membretti, A.; Krasteva, A.; Dax, T. The Renaissance of Remote Places: MATILDE Manifesto; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; ISBN 9781003260486. [Google Scholar]

- Cersosimo, D.; Donzelli, C. Manifesto per Riabitare L’Italia: Con un Dizionario di Parole Chiave e Cinque Commenti di Tomaso Montanari, Gabriele Pasqui, Rocco Sciarrone, Nadia Urbinati, Gianfranco Viesti; Donzelli Editore: Rome, Italy, 2020; ISBN 9788855221092. [Google Scholar]

- Lucatelli, S.; Luisi, D.; Tantillo, F. L’Italia Lontana: Una Politica per Le Aree Interne; Donzelli Editore: Rome, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Barbera, F.; De Rossi, A. Metromontagna: Un Progetto per Riabitare L’Italia; Donzelli Editore: Rome, Italy, 2021; ISBN 9788855222570. [Google Scholar]

- Marradi, C.; Mulder, I. Scaling Local Bottom-Up Innovations through Value Co-Creation. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2022, 14, 11678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sati, V.P. Sustainable Mountain Development: Challenges and Opportunities. In Towards Sustainable Livelihoods and Ecosystems in Mountain Regions; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 123–135. ISBN 9783319035321. [Google Scholar]

- Streifeneder, T. Cooperative Systems in Mountain Regions: A Governance Instrument for Smallholder Entrepreneurs. Rev. Geogr. Alp. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Aceituno, A.; Peterson, G.D.; Norström, A.V.; Wong, G.Y.; Downing, A.S. Local Lens for SDG Implementation: Lessons from Bottom-up Approaches in Africa. Sustain. Sci. 2020, 15, 729–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrado, F.; Dematteis, G.; Di Gioia, A. Nuovi Montanari. Abitare le Alpi nel XXI Secolo; FrancoAngeli: Milan, Italy, 2014; ISBN 9788820471118. [Google Scholar]

- Membretti, A.; Kofler, I.; Viazzo, P. Per Forza o per Scelta. L’immigrazione Straniera Nelle Alpi e Negli Appennini; Aracne: Lanuvio, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pettenati, G. I Nuovi Montanari. Q. J. Cult. Politics 2020, 6, 977–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Membretti, A.; Leone, S.; Lucatelli, S.; Storti, D.; Urso, G. Voglia di Restare: Indagine sui Giovani Nell’Italia dei Paesi; Donzelli Editore: Rome, Italy, 2023; ISBN 9788855224840. [Google Scholar]

- Barbera, F.; Parisi, T. Innovatori Sociali. La Sindrome di Prometeo Nell’Italia che Cambia; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 2019; 221p, ISBN 9788815280275. [Google Scholar]

- Barbera, F.; Bacchetti, E.; Membretti, A.; Spirito, A.; Orestano, L. Vado a Vivere in Montagna. Risposte Innovative per Sviluppare Nuove Economie Nelle Aree Interne. 2019. Available online: https://socialfare.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/InnovAree_report_web.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- Varotto, M. La Montagna che Torna a Vivere. Testimonianze e Progetti per la Rinascita Delle Terre Alte; Nuovadimensione: Portogruaro, Italy, 2013; ISBN 9788889100806. [Google Scholar]

- Polin, V.; Patanè, S. Orientare Pratiche di Valorizzazione Aziendale per Uno Sviluppo Sostenibile del Territorio. Una Ricerca-Azione Sull’identità Economica Locale Delle Imprese Artigianali del Monte Baldo; Final Report; Università di Verona: Verona, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Fondazione Montagne Italia. Rapporto Montagne Italia 2017: Le Montagne Della Diversità; Rubettino: Rome, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cavalli, L.; Polin, V.; Spinazzola, M. Quali Ingredienti per Una Buona Economia Delle Aree Montane? Voce Agli Esperti. 2022. Available online: https://iris.univr.it/bitstream/11562/1068413/1/feem-brief-01-2022_Polin%20et%20al.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- Polin, V.; Cavalli, L. MostraTi. Noi Pionieri della Buona Economia di Montagna; Visual research project; University of Verona-Fondazione Eni Enrico Mattei: Verona, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Cavalli, L.; Lizzi, G.; Polin, V. Quale Visione di Sostenibilità per i Territori Montani? Voce Agli Esperti; FEEM Policy Briefs; Fondazione Eni Enrico Mattei: Milano, Italia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Boeri, C.; Cavalli, L.; Polin, V. La Montagna Sull’Isola: La Rotta Verso la Sostenibilità, PNRR e Oltre (The Mountain on the Island: Toward Sustainability, NRRP and Beyond); FEEM Policy Brief; Fondazione Eni En rico Mattei: Milano, Italia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Barca, F.; McCann, P.; Rodríguez-Pose, A. The Case for Regional Development Intervention: Place-based versus Place-neutral Approaches. J. Reg. Sci. 2012, 52, 134–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucia, M.G.; Rota, F.S. Others La Protezione e Lo Sviluppo Delle Aree Montane Nella Prospettiva Del Piano Italiano Di Ripresa e Resilienza. Doc. Geogr. 2022, 1, 175–204. [Google Scholar]

- Spinazzola, M.; Cavalli, L. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the WEF Nexus. In Connecting the Sustainable Development Goals: The WEF Nexus; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 3–12. ISBN 9783031013355. [Google Scholar]

- Pahl-Wostl, C. Governance of the Water-Energy-Food Security Nexus: A Multi-Level Coordination Challenge. Environ. Sci. Policy 2019, 92, 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biermann, F.; Hickmann, T.; Sénit, C.-A.; Beisheim, M.; Bernstein, S.; Chasek, P.; Grob, L.; Kim, R.E.; Kotzé, L.J.; Nilsson, M.; et al. Scientific Evidence on the Political Impact of the Sustainable Development Goals. Nat. Sustain. 2022, 5, 795–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickmann, T.; Biermann, F.; Spinazzola, M.; Ballard, C.; Bogers, M.; Forestier, O.; Kalfagianni, A.; Kim, R.E.; Montesano, F.S.; Peek, T.; et al. Success Factors of Global Goal-setting for Sustainable Development: Learning from the Millennium Development Goals. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 31, 1214–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, M.; Keiler, M. International Frameworks for Disaster Risk Reduction: Useful Guidance for Sustainable Mountain Development? Mt. Res. Dev. 2015, 35, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stäubli, A.; Nussbaumer, S.U.; Allen, S.K.; Huggel, C.; Arguello, M.; Costa, F.; Hergarten, C.; Martínez, R.; Soto, J.; Vargas, R.; et al. Analysis of Weather- and Climate-Related Disasters in Mountain Regions Using Different Disaster Databases. In Climate Change, Extreme Events and Disaster Risk Reduction; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 17–41. ISBN 9783319564685. [Google Scholar]

- Perlik, M. The Spatial and Economic Transformation of Mountain Regions. Landscapes as Commodities; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Buran, P.; Aimone, S.; Ferlaino, F.; Migliore, M.C. Le Misure Della Marginalità 1998. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/199702896.pdf (accessed on 17 November 2023).

- Omizzolo, A.; Streifeneder, T. Lo Sviluppo Territoriale Nelle Regioni Montane Italiane Dal 1990 Ad Oggi. Available online: https://agriregionieuropa.univpm.it/it/content/article/31/27/lo-sviluppo-territoriale-nelle-regioni-montane-italiane-dal-1990-ad-oggi (accessed on 1 December 2023).

- Ferlaino, F.; Rota, F.S. La Montagna Nell’ordinamento Italiano: Un Racconto in Tre Atti. 2010. Available online: http://www.grupposervizioambiente.it/aisre/pendrive2010/pendrive/Paper/Ferlaino1.pdf (accessed on 11 October 2023).

- Baldi, M.; Marcantoni, M. La ‘Quota’ Dello Sviluppo. Una Nuova Mappa so-Cio-Economica Della Montagna Italiana; FrancoAngeli: Milano, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fondazione Montagne Italia. Rapporto Montagne Italia 2016. 2016. Available online: https://montagneitalia.it/rapporto-montagne-italia-2016/ (accessed on 9 November 2023).

- Bucci, G. L’indicazione Facoltativa “Prodotto Di Montagna”: Una Nuova Etichetta per Promuovere Lo Sviluppo Sostenibile Delle Aree Montane. Econ. Marche J. Appl. Econ. 2017, 36, 55–75. [Google Scholar]

- Modica, M.; Solero, E. Brownfield Transformation in Fragile Territories: An Inter-Reg-Based Action Research; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Modica, M. Alpine Industrial Landscapes. Towards a New Approach for Brownfield Redevelopment in Mountain Regions; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Membretti, A. Le Popolazioni Metromontane: Relazioni, Biografie, Bisogni”. In Metromontagna. Un Progetto per Riabitare L’Italia; Barbera, F., De, R.A., Eds.; Donzelli: Rome, Italy, 2021; pp. 173–200. [Google Scholar]

- De Matteis, G. Montanari per Scelta. Indizi Di Rinascita Nella Montagna Piemontese; Franco Angeli: Milano, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Dematteis, M.; Di Gioia, A.; Membretti, A. Montanari per Forza. Richiedenti Asilo e Rifugiati Nelle Montagna Italiana; Aracne: Rome, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Perlik, M.; Membretti, A. Migration by Necessity and by Force to Mountain Areas: An Opportunity for Social Innovation. Mt. Res. Dev. 2018, 38, 250–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teti, V. La Restanza; Einaudi: Torino, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Salvo, C.; Tomnyuk, V.; Membretti, A. Immobility Aspirations among Young Adults in Italian Inner Areas: Towards a «Capability to Stay». Sci. Reg. 2023; early access. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrario, V.; Manzo, M.C. La Montagna Che Produce. In La Montagna che Produce; Mimesis International: Milan, Italy, 2020; ISBN 9788857573564. [Google Scholar]

- Bolognesi, M.; Corrado, F. La Nuova Centralità Della Montagna. Sci. Territ. 2021, 9, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Matteis, G.; Magnaghi, A. La Visione Della Montagna Nel Manifesto Di Camaldoli, in La Nuova Centralità Della Montagna. Sci. Territ. 2021, 9, 18–24. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Political Economy of Institutions and Decisions: Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990; ISBN 9780521371018. [Google Scholar]

- Scolozzi, R.; Soane, I.D.; Gretter, A. Multiple-Level Governance Is Needed in the Social-Ecological System of Alpine Cultural Landscapes. In Scale-sensitive Governance of the Environment; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 90–105. ISBN 9781118567135. [Google Scholar]

- Dalla Torre, C.; Ravazzoli, E.; Omizzolo, A.; Gretter, A.; Membretti, A. Questioning Mountain Rural Commons in Changing Alpine Regions. An Exploratory Study in Trentino, Italy. Rev. Geogr. Alp. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliorati, L. Moving Alps. Le Conseguenze Sociali della Dismissione Industriale Nello Spazio Alpino Europeo; FrancoAngeli: Milan, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Migliorati, L.; Polin, V.; Veronesi, L. Il disegno della ricerca e la metodologia. In Moving Alps. Le Conseguenze Sociali della Dismissione Industriale Nello Spazio Alpino Europeo; Migliorati, L., Ed.; FrancoAngeli: Milan, Italy, 2021; pp. 27–37. [Google Scholar]

- Lompech, M. Mountain Cooperatives in Slovakia. Rev. Geogr. Alp. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lehner, O.M. Crowdfunding Social Ventures: A Model and Research Agenda. Venture Cap. 2013, 15, 289–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfang, G.; Smith, A. Grassroots Innovations for Sustainable Development: Towards a New Research and Policy Agenda. Environ. Polit. 2007, 16, 584–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniloska, N. Decentralized Environmental Decision Making. Econ. Dev. 2012, 14, 135–142. [Google Scholar]

- Liwanag, H.J.; Wyss, K. What Conditions Enable Decentralization to Improve the Health System? Qualitative Analysis of Perspectives on Decision Space after 25 Years of Devolution in the Philippines. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0206809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahl-Wostl, C.; Lebel, L.; Knieper, C.; Nikitina, E. From Applying Panaceas to Mastering Complexity: Toward Adaptive Water Governance in River Basins. Environ. Sci. Policy 2012, 23, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueff, H.; Inam-ur-Rahim; Kohler, T.; Mahat, T.J.; Ariza, C. Can the Green Economy Enhance Sustainable Mountain Development? The Potential Role of Awareness Building. Environ. Sci. Policy 2015, 49, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcantoni, M.; Vetritto, G. Montagne di Valore. Una Ricerca Sul Sale Alchemico Della Montagna Italiana; FrancoAngeli: Milan, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- UNCEM Verso la Nuova Strategia per le Montagne e le Aree Interne 2021. Available online: https://uncem.it/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/UNCEM-Strategia-Montagne-e-Aree-interne-futuro-giu2021.pdf (accessed on 13 July 2023).

- Li, Y.; Westlund, H.; Zheng, X.; Liu, Y. Bottom-up Initiatives and Revival in the Face of Rural Decline: Case Studies from China and Sweden. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 47, 506–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgroi, F. Forest Resources and Sustainable Tourism, a Combination for the Resilience of the Landscape and Development of Mountain Areas. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 736, 139539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevalier, M. Les phénomènes néo-ruraux. Espace Geogr. 1981, 10, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinelli, L. L’Italia è Bella Dentro: Storie di Resilienza, Innovazione e Ritorno Nelle Aree Interne; Altreconomia: Milan, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- ISTAT. Annuario Statistico Italiano 2020; ISTAT: Rome, Italy, 2020.

- Mens, J.; van Bueren, E.; Vrijhoef, R.; Heurkens, E. A Typology of Social Entrepreneurs in Bottom-up Urban Development. Cities 2021, 110, 103066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayring, P.A.E. Qualitative Content Analysis. In International Encyclopedia of Education, 4th ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 314–322. ISBN 9780128186299. [Google Scholar]

- Schreier, M. Qualitative Content Analysis. In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Analysis; SAGE Publications, Inc.: London, UK, 2014; pp. 170–183. ISBN 9781446208984. [Google Scholar]

- Löffler, R.; Beismann, M.; Walder, J.; Steinicke, E. New Highlanders in Traditional Outmigration Areas in the Alps. J. Alp. Res. 2014, 102, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, J.; Liang, M.; Zhang, C.; Rong, D.; Guan, H.; Mazeikaite, K.; Streimikis, J. Assessment of Corporate Social Responsibility by Addressing Sustainable Development Goals. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 686–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, H.L. Conducting Online Surveys. J. Hum. Lact. 2019, 35, 413–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V.; Boulton, E.; Davey, L.; McEvoy, C. The Online Survey as a Qualitative Research Tool. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2020, 24, 641–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, G. Bridging the Urban–Rural Digital Divide: In Frequencies; MQUP: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2020; pp. 162–186. ISBN 9780228003120. [Google Scholar]

- Teram, E.; Schachter, C.L.; Stalker, C.A. The Case for Integrating Grounded Theory and Participatory Action Research: Empowering Clients to Inform Professional Practice. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1129–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elmi, M.; Streifeneder, T.; Ravazzoli, E.; Laner, P.; Petitta, M.; Renner, K.; Garegnani, G.; D’alonzo, V.; Brambilla, A.; Bassano, B.; et al. The Alps in 25 Maps; Alpine Convention: Bolzano-Bozen, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Valentinov, V. Why Are Cooperatives Important in Agriculture? An Organizational Economics Perspective. J. Inst. Econ. 2007, 3, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. EIP-AGRI Focus Group New Entrants into Farming: Lessons to Foster Innovation and Entrepreneurship; Final Report; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Guiomar, N.; Godinho, S.; Pinto-Correia, T.; Almeida, M.; Bartolini, F.; Bezák, P.; Biró, M.; Bjørkhaug, H.; Bojnec, Š.; Brunori, G.; et al. Typology and Distribution of Small Farms in Europe: Towards a Better Picture. Land Use Policy 2018, 75, 784–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbera, F.; Membretti, A. Alla Ricerca Della Distanza Perduta. Rigenerare Luoghi, Persone e Immaginari Del Riabitare Alpino. Archalp 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastings, L.; Barrett, L.; Barbuto, J.; Bell, L. Developing a Paradigm Model of Youth Leadership Development and Community Engagement: A Grounded Theory. J. Agric. Educ. 2011, 52, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noack, A.; Federwisch, T. Social Innovation in Rural Regions: Urban Impulses and Cross-Border Constellations of Actors. Sociol. Ruralis 2019, 59, 92–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumeier, S. Why Do Social Innovations in Rural Development Matter and Should They Be Considered More Seriously in Rural Development Research?—Proposal for a Stronger Focus on Social Innovations in Rural Development Research. Sociol. Ruralis 2012, 52, 48–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolo, D.; Ricca, B.; Nicolò, D. Under-Capitalization and Other Factors That Influence the Survival of Young Italian Companies. Available online: https://iris.unime.it/retrieve/handle/11570/3137677/231693/568-1782-1-PB.pdf (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- Giaccio, V.; Giannelli, A.; Mastronardi, L. Explaining Determinants of Agri-Tourism Income: Evidence from Italy. Tour. Rev. 2018, 73, 216–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, S.R.; Bloom, N.; Davis, S.J.; Terry, S.J. COVID-Induced Economic Uncertainty 2020; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gruber, M.; Lardiés-Bosque, R.; Membretti, A. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Remote and Rural Regions of Europe: Foreign Immigration and Local Development; Gran Sasso Science Institute: L’Aquila, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gallegati, S. Opportunità e Sfide per Lo Sviluppo Del Turismo Sostenibile: Il Caso Della Regione Marche. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Padua, Padua, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Pencarelli, T.; Dini, M. Idee e proposte per lo sviluppo del turismo nelle Marche post COVID-19. In Una Regione in Metamorfosi e la Necessità di Delineare Percorsi Evolutivi; ITA: Rome, Italy, 2021; pp. 53–73. ISBN 9788860567604. [Google Scholar]

- Membretti, A.; Viazzo, P.P. Negotiating the Mountains. Foreign Immigration and Cultural Change in the Italian Alps. Martor 2017, 22, 93–107. [Google Scholar]

- Zanon, B. Territorial Innovation in the Alps. Heterodox Reterritorialization Processes in Trentino. Ital. J. Plan. Pract. 2018. Available online: https://iris.unitn.it/handle/11572/198838 (accessed on 12 September 2023).

- Bosworth, G.; Rizzo, F.; Marquardt, D.; Strijker, D.; Haartsen, T.; Aagaard Thuesen, A. Identifying Social Innovations in European Local Rural Development Initiatives. Innovation 2016, 29, 442–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, M.A.; Bresciani, S. Crowdfunding Small Businesses and Startups: A Systematic Review, an Appraisal of Theoretical Insights and Future Research Directions. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2022; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böckel, A.; Hörisch, J.; Tenner, I. A Systematic Literature Review of Crowdfunding and Sustainability: Highlighting What Really Matters. Manag. Rev. Q. 2021, 71, 433–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, W.; Brundtland, G.H. Our Common Future (‘the Brundtland Report’): World Commission on Environment and Development. In The Top 50 Sustainability Books; Greenleaf Publishing Limited: South Yorkshire, UK, 2013; pp. 52–55. ISBN 9781907643446. [Google Scholar]

- Alhaddi, H. Triple Bottom Line and Sustainability: A Literature Review. Bus. Manag. Stud. 2015, 1, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasselbalch, J.A.; Kranke, M.; Chertkovskaya, E. Organizing for Transformation: Post-Growth in International Political Economy. Rev. Int. Political Econ. 2023, 30, 1621–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamagni, S. Beni Comuni Territoriali e Economia Civile. SdT 2018, 6, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Basilicata | Lombardia | Marche | Sicilia | Veneto | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 50 | 79 | 58 | 94 | 114 | 395 |

| Basilicata | Lombardia | Marche | Sicilia | Veneto | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 17 | 43 | 33 | 32 | 71 | 196 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Polin, V.; Cavalli, L.; Spinazzola, M. Bottom-Up Initiatives for Sustainable Mountain Development in Italy: An Interregional Explorative Survey. Sustainability 2024, 16, 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16010093

Polin V, Cavalli L, Spinazzola M. Bottom-Up Initiatives for Sustainable Mountain Development in Italy: An Interregional Explorative Survey. Sustainability. 2024; 16(1):93. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16010093

Chicago/Turabian StylePolin, Veronica, Laura Cavalli, and Matteo Spinazzola. 2024. "Bottom-Up Initiatives for Sustainable Mountain Development in Italy: An Interregional Explorative Survey" Sustainability 16, no. 1: 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16010093

APA StylePolin, V., Cavalli, L., & Spinazzola, M. (2024). Bottom-Up Initiatives for Sustainable Mountain Development in Italy: An Interregional Explorative Survey. Sustainability, 16(1), 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16010093