Abstract

There is minimal level of use of Computer-Assisted Audit Tools and Techniques (CAATTs) in developing nations regardless of its importance to audit productivity and cost reduction, and this holds particularly true in the public sector entities’ internal audit departments. Accordingly, this article aims to explore how technological factors, such as relative advantage, complexity, compatibility, observability, and trialability, contribute to the use of CAATTs in Jordan’s public sector internal audit during the COVID-19 pandemic and the impact of the pandemic on the profession’s outcome. The study also seeks to evaluate how the use of these tools affects the effectiveness of internal auditing, with the IT knowledge of the auditors serving as a moderating variable. This study used 91 usable responses from the internal audit managers of Jordanian public sector institutions. The study used the Diffusion of Innovation (DOI) theory to develop the proposed research model. Using Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), the study result indicated that technological factors, with the exception of complexity, had a positive and significant effect on CAATTs use in the public sector internal audit departments. Based on the findings, using CAATTs has a positive and significant effect on internal audit effectiveness and IT knowledge has a positive moderating effect on the relationship between CAATTs usage and internal audit effectiveness. Owing to the public sector significance to the economy of Jordan, the findings have implications for the internal audit profession, regulators, and decision-makers in proposing new legislation and regulations when it comes to internal audit. Further, through the lens of the social implications, this study proposed that CAATTs usage in public sector institutions can positively improve their capability to reach the role of internal audit in protective public funds and limiting corrupt practices in the public sector. The paper contributes to theory by providing insight into the effect of factors on the use of CAATTs in the public sector of Jordan. This study, to the best of the author’s knowledge, is the first study that has tackled the moderating role of auditors’ IT knowledge on the CAATTs use–internal audit effectiveness relationship in the public sector context.

1. Introduction

Audit technology has been generally used for improving the quality of audits, which is why the US Auditing Standards has mandated its use [1,2,3]. More specifically, the US Statement of Auditing Standards (SAS) No 316.52 mandates the need for the auditor to use computer-assisted audit techniques to obtain enriching evidence concerning the data of accounts and electronic transaction files [4,5] towards the identification of fraud and risks. Along the same line, CAATTs can be generally referred to as technology used for audit task completion [2,6]. Additionally, CAATTs have also been referred to as various tools, technologies, and software that auditors use towards controlling and affirming tests, analyzing and controlling financial statement information, and overseeing auditing activities [7,8,9].

Further, CAATTs are becoming increasingly important in the public sector as they can enhance the effectiveness and efficiency of internal audit activities. The use of CAATTs enables auditors to analyze large volumes of data in a more accurate and efficient manner, which is particularly important in the public sector where there are large and complex datasets [2]. In many countries, the use of CAATTs is mandatory for public sector auditors. For example, the United States Government Accountability Office (GAO) requires the use of CAATTs in its audits of federal agencies. Similarly, the International Standards for Supreme Audit Institutions (ISSAI) require that public sector auditors use CAATs where appropriate. However, the adoption and use of CAATTs in the public sector varies across countries and jurisdictions. Some public sector auditors may face challenges in adopting and using CAATTs due to a lack of resources, technical expertise, or organizational culture. In addition, there may be concerns regarding data security and privacy in the public sector, which may limit the use of CAATTs. Despite these challenges, there is a growing trend towards the use of CAATTs in the public sector. Many public sector auditors are recognizing the potential benefits of CAATTs and are investing in the necessary resources and training to support their use. Additionally, advancements in technology and data analytics are making it easier for auditors to use CAATTs and to derive insights from large datasets.

A review of relevant studies showed that CAATTs is the use of technology for the performance of auditing, and these include the use of Utility Programs, Electronic Working Papers, Electronic Spreadsheets, Purpose-Written Programs, Test Data, Parallel Simulation, Integrated Test Facility (ITF), Generalized Audit Software (GAS), and Embedded Audit Modules [9,10,11,12]. Moreover, CAATTs use effectiveness can lead to enhanced internal control, informed decision-making, and facilitated auditing task processes [13]. Such effectiveness is highlighted in the user’s capability of using audit technology to obtain information for the purpose of meeting control and improvement requirements [14,15]. Hence, auditors’ effective use of CAATTs is a must while auditing to ensure accurate and authentic evidence [13]. Lack of effectiveness among users and lack of qualification and experience may hinder the end game—auditor’s IT knowledge thus has a moderating role between CAATTs use and the effectiveness of such use.

In the case of developing nations, technology use in accounting has progressed, which has given rise to the need to examine audit technology use within them [9]. This is of urgent need concerning the importance of high-level quality audits in guaranteeing the financial reporting integrity, particularly in developing nations, wherein questionable quality and transparency has been related to financial reporting [11,16]. Notably, the recent COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on the process of accounting has been followed by the automatic development of audit processes [17,18,19], making CAATTs important to keep abreast of developments, especially because a significant relationship exists between auditing and the auditing environment [20].

More specifically, in Jordan, regardless of the advancements in information technology [21] and the evidence that using such technology can enhance the performance and effectiveness of task completion [11,12,22], the public sector of the country is still ineffective when it comes to internal audit task completion [23]. This has been exacerbated further by the COVID-19 pandemic [24].

Thus, the focus of this paper is on CAATTs use among the Jordanian public sector internal auditors [25]. Studies of this caliber in the literature evidenced that, owing to the intricacies of public sector transactions and the environmental complexity [23,26], the growth level and the extent of tool use have been left behind in public sector institutions. Thus, the question arises as to the lack of CAATTs use among auditors in the public sector, and in this paper the primary aim is to examine the factors that may have caused the issue, particularly during and following the COVID-19 pandemic.

Literature dedicated to IT use has extensively employed the Diffusion of Innovation (DOI) theory proposed by [27] to explain the use of technological innovations among firms. The theory is generally adopted to explain technology use in light of relative advantage, compatibility, observability, trialability, and complexity [28,29]—variables that can strengthen or hinder technology use [30]. Based on the theory, there are perceived innovation characteristics that can affect its adoption or rejection [31].

The lack of studies concerning the DOI theory in the field of auditing and auditing innovation has been exacerbated by the limited focus on external audit in developed nations, largely ignoring the internal audit departments for advanced technology in developing nations, particularly in the public sector [32]. Moreover, the drivers or preventers of new innovation adoption in public sector internal audit varies from one context to the next, which holds true from developed to developing nations [33]. Hence, this study examines the effect of technological factors on CAATTs use, with IT knowledge of auditors as the moderating variable in the Jordanian public sector, using the DOI theory as the underpinning theory.

Added to the above, there is a need to develop the outcomes of the effect of IT knowledge among internal auditors in explaining DOI variables. Such refinement is required to improve the DOI validity and usefulness in the field of CAATTs research, and this study minimizes the literature gap by determining if the IT knowledge of internal auditors has a moderating role on the relationship between using CAATTs and its use effectiveness. It is noteworthy to mention this pioneering study is one of the few that focused on CAATTs use and its explanation through DOI technological factors, and in turn, the effectiveness of such use—all this is encapsulated and proposed in one framework as opposed to distinct ones and is examined in the period ravaged by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The study objectives are to contribute to decision makers, including the relevant ministers, parliament and senate, upper management, and internal auditors, as well as software providers when it comes to understanding the usage decisions of CAATTs in the public sector among internal auditors during COVID-19 and its aftermath. Further, it is proposed that CAATTs usage in public sector institutions can positively improve their capability to reach the role of internal audit in protective public funds and limiting corrupt practices in the public sector. The established research objective can be achieved through addressing the research questions, “To what extend did technological factors, namely relative advantage, complexity, compatibility, observability, and trialability, directly affect the use of CAATTs in the public sector internal audit domain during the COVID-19 pandemic?”, “To what extend did the use of CAATTS affect its effectiveness of use in the public sector internal audit domain during the COVID-19 pandemic?”, and “Did the IT knowledge of internal auditors moderate the relationship between CAATTs use and its use effectiveness in the public sector internal audit domain during the COVID-19 pandemic?”.

2. Literature Review

There exists a fairly extensive literature on IT audit, albeit those dedicated to the factors driving and inhibiting CAATTs use are still limited [8]. For instance, the factors influencing IT audit quality, using support tools, were the focus of [34] work, but the authors did not address the factors of CAATTs use among auditors. Studies concerning CAATTs development and application auditors are plentiful [2,9,13,20,35,36], but they have been largely conducted among external auditors [33,34,37,38]. Such studies include documented instances as to the reasons behind CAATTs adoption among external auditors [1,4,39,40], with only a few dedicated to internal auditors [41,42,43,44]. Aside from this, prior literature on the subject is limited to the private sectors of developed nations, with the public sector being the recipient of minimal attention, particularly when it comes to the internal audit public sector in Jordan.

Research on the factors influencing CAATTs use does exist in the literature, with the majority of them focusing on the individual level rather than on the organizational one. In this regard, the acceptance of CAATTs needs to begin from the decision of the organization to obtain it through an investment and facilitate its use for individual working within the organization. Moreover, theories abound concerning technology use in the IS research field [45], with the most extensively adopted being [46] TAM, Ajzen’s [47] TPB, and Venkatesh et al.’s [48] Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology. In addition to the above are Rogers’s [27] Diffusion of Innovation (DOI) theory and Tornatzky and Fleischer’s [49] TOE framework. From these theories, both DOI and TOE are firm-level theories, while TAM, TPB, and UTAUT are individual-level ones. Prior studies using TOE for examining CAATTs use or a combination of TOE and DOI are few and far between, with each study employing various factors on the basis of the studies’ contexts. Limited studies are more pronounced when it comes to using DOI in the internal audit case and, thus, this study attempts to shed light on the use of CAATTs on the organizational level.

Furthermore, studies concerning IT use has adopted Rogers’s [27] DOI to explain technology use among firms; in fact, DOI is a commonly utilized theory of the same, with the main focus on technological characteristics, namely relative advantage, complexity, observability, compatibility, and trialability [28,29]—factors that either promote or inhibit the use of technology [30]. Several studies acknowledge and accept the critical innovation characteristics that may influence its adoption/rejection [31], and thus, DOI is used in this study to explain the determinants of CAATTs use among public sector internal auditors in Jordan.

The Computer-Assisted Audit Tools and Techniques (CAATT)

CAATTs have been generally referred to as technology that assists in audit task completion [6]. This definition was followed by the one using the term ‘different tools, technologies, and software’ that assist auditors to directly control and affirm tests, analysis and monitor financial statement information, and oversee auditing activities [7]. Based on the above, this paper defines CAATTs as the technology use that assists auditors to perform audit, including Utility Programs, Electronic Working Papers, Electronic Spreadsheets, Parallel Simulation Software, Purpose-Written Programs, Audit Automation, Test Data, Embedded Audit Modules, Integrated Test Facility, Integrated Test Facility, and Generalized Audit Software [10].

CAATTs enable the freedom to obtain information in the system while being independent of the user, confirm the used software quality, and enhance the accuracy of audit tests and their efficiency, leading to a long-term, low-cost audit. In the same way, CAATTs enable the auditor to save time by facilitating the above, and in the majority of cases they supplant manual testing methods with strategies, sparing the auditor hours/days on the audit process. For instance, CAATTs can be used in two sheets generated in a couple of seconds to determine if any invoice contains irrelevant order/goods receipts, a far-cry from the generation of 25 invoices and wasting resources on the items in order to confirm the same in a three-way coordination. Thus, using CAATTs allows auditors to reap advantages while arranging and directing audits and reporting the audit findings [50]. As such, this study attempts to shed light on the factors preventing/promoting internal audit departments in the Jordanian public sector to reap the benefits of CAATTs, and to determine the effect on its use effectiveness. The study also attempts to determine the moderating role of IT knowledge among auditors in the CAATTs use–use effectiveness relationship.

The public sector’s internal audit task effectiveness and the use of Computer-Assisted Audit Tools and Techniques (CAATTs) could be influenced by auditors’ IT knowledge. Auditors’ IT knowledge can have two potential impacts: it can either enhance the benefits of CAATTs use or mitigate their limitations. When IT knowledge is high, auditors can utilize CAATTs more efficiently and gain superior insights for decision-making. This can lead to improved overall audit quality and increased effectiveness of internal audit tasks. On the other hand, low IT knowledge may result in challenges when using CAATTs, forcing auditors to rely on manual testing procedures or misinterpret CAATTs-generated results. Consequently, this may reduce internal audit task effectiveness and result in inaccuracies or errors during the audit process. Therefore, auditors’ IT knowledge level plays a pivotal role in moderating the relationship between CAATTs use and internal audit task effectiveness in the Jordanian public sector. Higher IT knowledge levels can increase the benefits of CAATTs and reduce their limitations. Conversely, lower IT knowledge levels may limit the advantages of CAATTs, exacerbate their limitations, and diminish internal audit task effectiveness.

3. Underpinning Theory and Hypotheses Development

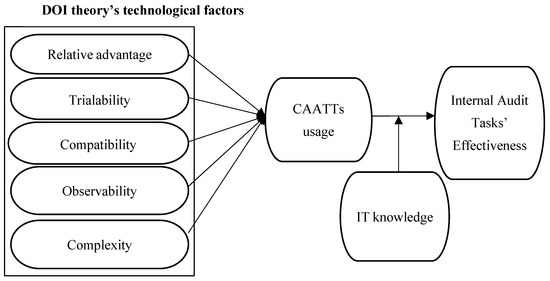

Diffusion of Innovation Theory (DOI) has its basis in sociology and was first proposed in the 1960s for examining different technology types [49]. It was proposed to develop the innovation decision process, and according to Moore and Benbasat [29] the theory is built on five innovation characteristics, namely, relative advantage, complexity, compatibility, observability, and trialability. The authors proposed the theory in the field of IS to predict the use of technologies among users. The DOI theory framework sheds light on various influences on technology use (e.g., CAATTs), and these include the mentioned characteristics of innovation, which are relative advantage, complexity, compatibility, observability, and trialability [51]. Studies have validated such characteristics and their role in technology use [9,29,48,52,53]. Thus, this study extends the work on the characteristics validity by determining their influence on CAATTs use among internal auditors in the public sector of Jordan. The study proposes five hypotheses explaining the technological factors influence on the use of CAATTs (see Figure 1). This study contributes to the DOI theory literature by extending its use to CAATTs and by testing the IT knowledge of internal auditors as a moderating variable that plays a role in the relationship between CAATTs use and such use effectiveness. In other words, the study seeks to test the variables of DOI theory on a new area of study.

Figure 1.

Research Model.

3.1. Relative Advantage

According to Rogers [51], the relative advantage is the level to which an innovation is viewed to be better than its predecessor [54]. Generally speaking, IT is an instrument that is utilized to obtain sustainable relative advantage [55,56,57,58]. Studies on this effect have evidenced the positive perceived gain of technology use–relative advantage of IT innovation relationship [59], and as such innovative practices and the use of technology generally provide users with a sustainable advantage [60,61].

In the case of using CAATTs in public organizations, the benefits from its use need to be understood by the internal audit departments in such organizations [9] in order so that they can obtain differentiation, facilitate it for their tasks, and use creative techniques to best meet the stakeholders’ demands [62]. This may be exemplified by eyewear shops that differentiate themselves from their rivals by using technology to enable shoppers to test their items prior to buying them [63]. Added to this, Chandra and Kumar [60] found that relative advantage has a significant effect on the augmented reality use intention, and in the context of CAATTs use, Siew et al. [9] revealed that relative advantage, as a control variable, significantly and positively affected the use of CAATTs. It is thus proposed in this paper that relative advantage will boost the public sector to adopt the technology in internal audit departments, in other words:

H1.

Relative advantage had a positive effect on the use of CAATTs in the public sector during the COVID-19 pandemic.

3.2. Complexity

Complexity refers to the level to which an innovation is viewed to be difficult to understand and use. According to Rogers [51], new technology/system use may end in failure if it is viewed to be too challenging to use—for instance, challenges in process changes to work in tandem and thus, ease of use of technology facilitate its improved use level [64,65]. It is important for users to understand new technology, because the newer the technology, the more sophisticated it will be, and the higher level of uncertainty could lead to its complex use process [66,67].

Complexity has been illustrated as a significant factor in innovation use [65,68], and this is why decision-makers face the question as to whether or not to adopt innovation [69,70,71]. In comparison to other innovation elements, prior studies have confirmed that complexity negatively relates to new technology use [64,72,73,74,75]. In CAATTs use among internal auditors of the public sector, the perception of CAATTs use is full of complexity and, thus, the likelihood of adoption is lower. This leads to the following hypothesis:

H2.

Complexity had a negative effect on the use of CAATTs in the public sector during the COVID-19 pandemic.

3.3. Compatibility

Compatibility refers to the perception that the innovation matches the values, past experiences, and needs of potential users [51]. With regards to the use of CAATTs in the public sector, compatibility is the level to which the technology fits with the existing infrastructure, practices, values, and culture of the public institutions [51,76]. Past studies on technology innovation adoption have revealed mixed results, with some findings indicating no effect of compatibility on CAATTs use [77,78], while others support its negative effect [9]. According to Martinez et al. [79], compatibility forms a bottleneck that could affect the use of new technology.

The majority of studies examined compatibility as one of the major factors that influence innovation use (e.g., CAATTs) [64,74,80]. More specifically, Zhu et al. [80] reported that it is the top factor that influences the post-use of digital transformation in European enterprises. Meanwhile, Rogers [51] insisted that compatibility between technology (CAATTs) and company policies would make its adoption easier. It is thus argued that public sector internal audit departments consider CAATTs as compatible if it is aligned with their current needs, values, and culture, and thus, it is proposed that:

H3.

Compatibility had a positive effect on the use of CAATTs in the public sector during the COVID-19 pandemic.

3.4. Trialability

According to Rogers [51], trialability refers to the level to which an innovation may be tested and experimented with prior to actual use, and this trial or experimentation is important to the decision of the organization to adopt the innovation [9,81]. In a related study, Alshamaila et al. [64] revealed that trialability can minimize uncertainties in the use of cloud computing among SMEs, and thus, it is a significant factor that influences technology systems usage [78,82,83,84,85,86]. With regards to the use of CAATTs, the public sector internal audit departments need to test the system prior to its adoption to ensure its usefulness and reliability in task completion and to justify its adoption. Hence, in this study, the trialability of CAATTs is argued to support the adopt it for the use of internal audit departments in the public sector and, as such, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H4.

Trialability had a positive effect on the use of CAATTs in the public sector during the COVID-19 pandemic.

3.5. Observability

Generally speaking, observability is the extent of people’s view of the effect of using technology. Successful use of new technology mitigates uncertainty and makes individuals and the whole organization willing to adopt it [27]. Based on a review of innovation articles, Kapoor et al. [87] proposed observability as a driver of innovation use among organizations, while empirical testing of the variable by several authors [9,74,78,88,89] revealed its significant relationship with technology use. The majority of the studies, however, reported a weak relationship between the two variables, such as Ramdani and Kawalek [90] and Sun et al. [91], indicating inconclusive findings concerning the role of observability in using technology [92,93]. This study contends that if CAATTs use and its advantages are observed by the public sector institutions and their internal audit departments, their likelihood to adopt it will heighten and, thus, this study proposes that:

H5.

Observability had a positive effect on the CAATTs use in the public sector during the COVID-19 pandemic.

3.6. CAATTs Usage and Internal Audit Tasks’ Effectiveness

In several countries, including Belgium, Hungary, Denmark, Malaysia, the US, and Switzerland, CAATTs have been legally accepted, with its audit databases used to record audits. Meanwhile, in the UK, CAATTs is employed for data analysis development and for obtaining documentation outcome, and in South Africa, it is used for security analysis, audit planning, and audit-related documents preparation.

The literature on CAATTs use among auditors for their auditing tasks is extensive [6], even during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. CAATTs cover processes including e-worksheets, artificial intelligence tools, and statistical analysis software predicting breaches or failures in financial statements [6,94,95]. Both auditor circles and audit firms reap the benefits from CAATTs as it enables them to decrease audit cost, enhance audit and productivity quality, maintain audit reports, and enhance the effectiveness of the overall audit [96]. It also allows them to carry out complex tax calculations manually and to examine the internal controls set up by the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) towards facilitating effective control based on the Sarbanes–Oxley Act (Section 404) and towards enhancing the detection of fraud [97].

It is without doubt that technology-based auditing generates higher effectiveness and capability when it comes to carrying out internal audit tasks, within which IT works towards minimizing time to complete tasks, minimizing costs spent, enhancing the audit quality, lessening the risks, and maximizing profitability and market shares [5,98,99]. Performance improvement is significant for minimizing the gap between the internal auditors’ use of CAATTs and its effectiveness. The DOI posits a positive relationship between the two variables (CAATTs use and its effectiveness) [29,100]. Added to this, Daouda et al. [20] showed that CAATTs use among audit firms in Jordan positively affects the performance and effectiveness of the audit, which means there is a fit between the users and technology, and this influences performance. The study therefore proposes that CAATTs use influences internal audit effectiveness among internal auditors in public institutions in Jordan. Thus, this study proposes the following hypothesis for testing:

H6.

CAATTs use had a positive effect on the audit task effectiveness in the public sector during the COVID-19 pandemic.

3.7. Auditors’ IT Knowledge Moderates the Relationship between CAATTs Use and Internal Audit Task Effectiveness

The extensive use of computerized IS paves the way for auditors to efficiently and effectively obtain audit evidence, and this is clear from the interrogation and use of test data files that is possible through CAATTs. Nevertheless, using CAATTs and other technologies of its kind also has its disadvantages and its complex requirements (e.g., experts’ involvement), which could take time and be costly, particularly in the first phase of installation. Lack of experts would lead to the need for existing staff training in CAATTs use in auditing tasks, and this takes financial resources, auditors’ commitment, and time [101]. In the same line of study, Merhout and Buchman [102] explained that in understanding technologies and their use in the business environment, auditors need to be equipped with IT knowledge and technological skills in order to use technology for better and more accurate auditing [103]. Moreover, the established standards from the Standards for Information Systems Auditing (SISA) 040: Competence issued by ISACA [4] mandates that information system auditors have to be qualified with technical knowledge and skills to conduct auditing work, and such skills and knowledge need to be upgraded and updated through ongoing training and education levels.

Therefore, the relationship between the use of CAATTs and internal audit task effectiveness in the public sector could be influenced by the level of auditors’ IT knowledge. Auditors’ IT knowledge can moderate this relationship in two ways: by enhancing the benefits of CAATTs use or by reducing their limitations. On one hand, when auditors have a higher level of IT knowledge, they are more likely to effectively use CAATTs and derive greater benefits from their use. For example, auditors with high IT knowledge may be able to more effectively analyze and interpret the data generated by CAATTs, leading to greater insights and more informed decision-making. This, in turn, can enhance the effectiveness of internal audit tasks and improve overall audit quality. On the other hand, when auditors have a lower level of IT knowledge, they may struggle to effectively use CAATTs and derive benefits from their use. This can lead to limitations such as increased reliance on manual testing procedures or the misinterpretation of results generated by CAATTs. These limitations can reduce the effectiveness of internal audit tasks and may result in errors or inaccuracies in the audit process. Therefore, the level of auditors’ IT knowledge can moderate the relationship between CAATTs use and internal audit task effectiveness in the Jordanian public sector. When auditors have a higher level of IT knowledge, the benefits of CAATTs use are likely to be enhanced, while their limitations are likely to be reduced. In contrast, when auditors have a lower level of IT knowledge, the benefits of CAATTs use may be limited, and their limitations may be exacerbated, resulting in lower levels of internal audit task effectiveness.

Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the importance of IT knowledge in organizations at all levels and sectors, considering the shift towards online works. In the case of internal audit, IT knowledge among auditors has led to enhanced CAATTs effectiveness, and the lack of it affected such effectiveness in a negative direction. In other words, technology availability makes no difference if its proper use is not followed, just as a smartphone buyer who does not know how to use it will not obtain any benefit from it. Based on the above, it can be contended that the use of CAATTs has a significant effect on its use effectiveness among auditors equipped with a good level of IT knowledge, compared to the same among auditors lacking such knowledge. This study thus determines if the IT knowledge of auditors has a moderating role in the relationship between CAATTs use and its use effectiveness during the COVID-19 pandemic among Jordanian public sector internal auditing institutions. Thus, this study proposes that:

H7.

IT knowledge had a moderating effect on the relationship between CAATTs use and internal audit task effectiveness in public sector during the COVID-19 pandemic.

4. Methodology

The present study population includes all of the Jordanian public sector institutions (due to the small size of the population), except for the Ministry of Interior and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Expatriates due to the confidential nature of their data [104]. The sample frame includes 23 ministries, 218 governorates, 27 independent bodies, and 10 universities. Hence, the study sample includes 278 entities distributed in the Kingdom of Jordan. For the purpose of achieving the study objectives, surveys were distributed to 278 internal audit departments in the public sector of Jordan from 20 May to 25 August 2022. The author made two follow-up reminders through email, WhatsApp, and phone calls. From the analysis of the demographic data, the majority of respondents (66.8%) were male respondents, while the rest (33.2%) were female respondents, and the majority of them worked as internal audit department managers (54.8%), with some being financial audit managers (32.4%) and others managerial audit managers (12.8%). The majority of respondents (45.3%) held master degrees, several (38.6%) held bachelor degrees, while a few (6.9%) were PhD holders and diploma degree holders (9.2%).

There were 94 responses, out of which two were found to be incomplete, in a way that 15% of the questions had no responses and thus missing data was calculated by construct and were revealed to be below 1% [105]. Because this was the case, mean value replacement rather than case-wise deletion was used in rectifying the issue [105]. The study followed Hair et al.’s [106] recommendation of mean replacement in SPSS software for missing values. One outlier response was also eliminated based on extreme values exclusion in SPSS boxplot [107]. Following the process of data cleaning, the total useable responses for analysis numbered a total of 91 responses.

The sample size was tested through power-analysis (G*Power) software, and the responses were revealed to be sufficient for the use of PLS-SEM [108,109,110,111,112]. Wherein, PLS-SEM was used for analyzing the relationships between latent variables in a structural model. It is a form of structural equation modelling that is particularly useful for analyzing complex models with small to medium-sized samples. The PLS-SEM approach involves two main models: the measurement model and the structural model. The measurement model is concerned with the relationship between the observed indicators and the underlying latent constructs. It is used to establish the validity and reliability of the measurement instruments used to measure the constructs of interest. The measurement model specifies the factor loadings, the convergent validity, and the discriminant validity of the latent constructs. On the other hand, the structural model is concerned with the relationships between the latent constructs. It specifies the path coefficients and R-squared values for the endogenous constructs. Additionally, the early responses were compared with late responses for non-response bias determination, and no significant differences were found [113].

4.1. Measurement of Variables

The items in the developed questionnaire were mainly adopted from past survey instruments in the literature that were already validated [114]. Additionally, a pilot study was carried out in the audit departments prior to the actual survey to test the questionnaire survey items’ reliability and the instructions and items’ clarity.

In designing the research procedures and statistical controls, the study followed Podsakoff et al.’s [115] recommendations to manage Common Method Variance. Specifically, two different measurements of independent and dependent variables were adopted in the questionnaire—for the independent variables, the scale endpoints and formats varied from bipolar measurement scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree, while for the dependent variables they varied from unipolar measurement from never used at all to extensively used. This method ensures minimized biases in the method, stemming from the commonalities in the scale endpoint. Another detail adopted was that the instructions clarified the absence of right and wrong answers when it came to their perceptions regarding using audit technology so that they could answer freely without bias [115].

The study’s dependent variable Is the level of CAATTs use among internal auditors in the departments of public sector institutions in Jordan, and based on this, the major applications of CAATTs were included, and they are as follows: Audit Automation Software (which generates a trial balance and schedules relevant to keeping evidence of audit/assurance engagement), Test Data (a set of transaction input data that the auditor prepares for testing the application program/procedural processes), Generalized Audit Software (which assists the auditor in accessing the system database of the client for extracting data and performing audit function analysis), Embedded Audit Modules (which is a programmed audit module integrated in the application program of the client and is used to determine transactions that meet the measures of the auditor). Such transactions are reviewed in actual real-time or in stages. The final application is Parallel Simulation Software (the abstraction of the real application of the client that is developed to mimic the client application generated results). A model may be utilized for comparison of the results and evaluation of the information reliability—information produced by the system of the client [6,8,9,94,116]. This variable was measured by instruments adopted from relevant studies [117,118], which measured it as the total product score of the number of CAATTs applications adopted and the level of audit tasks carried out through their use. Such aggregate score is a sufficiently robust measure for assessing the level of technology use implementation and use, and such operationalization covers two essential IT/IS use characteristics [118].

Moreover, each CAATT’s score was aggregated to form one item total score for the dependent variable (CAATTs use). Aligned with the IS use studies [117,118,119], the percentage of the carried-out audit tasks using CAATTs was analyzed in light of five groups (0% depicting never use, 1–25%, 26.5%, 51.75%, and 76–100% depicting extensively used) ranging from 1 to 5. Each CAATTs application response was aggregated to develop a single-item total score for the dependent variable.

Aside from the above, the independent variable items were gauged using a 5-point bipolar scale that ranged from strongly disagree, depicted by 1, to strongly agree, depicted by 5, following Venkatesh and Bala [118] and Moore and Benbasat [29]. The items of each variable are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Measurements of Constructs.

4.2. Data Analysis Technique

The study carried out data statistical analysis with the help of PLS-SEM, which is suitable considering that the research has a small sample size [105]. PLS-SEM is a suitable technique to be applied to situations that are exploratory in nature [106] and when the study objectives stress the prediction and explanation of the variance of the main dependent variable by various independent variables. These conditions match the present study, with the main objective being to determine the influencing factors of DOI on CAATTs usage in the internal audit departments.

5. Result

At the item level, the loadings were obtained, and the results are tabulated in Table 2, within which six indicators (CMPX1, RA3, IATE1, IATE12, IATE13, and IATE 15) obtained values that did not meet the acceptable 0.7 standard loading and were hence excluded from analysis following Hair et al. [105]. All the results satisfy the discriminant validity condition, with the entire items loading higher on their respective constructs compared to other model constructs [106]. This left the examination and analysis of the measurement model and the structural model in that order, as per Hair et al.’s [105] suggestion.

Table 2.

Loadings, AVEs, Composite Reliability, and Cronbach’s alpha for measurement items.

5.1. Measurement Model

The measurement model’s convergent validity test results are displayed in Table 2, covering the loadings, composite reliability, and Cronbach’s alpha values of the items. The Cronbach’s alpha values exceeded 0.70 and the AVE values were higher than 0.5—both establishing convergent validity [105].

The study also tested the measurement model’s discriminant validity in order to establish the distinction of each variable from the model variables. This was achieved at both levels (item and construct) using cross-loadings in Fornell–Larcker criterion values, the result of which are displayed in Table 3. Squared AVE for the pairs of constructs were higher than the constructs’ correlations, thus establishing discriminant validity [105,121].

Table 3.

The square roots of AVE.

Prior to the assessment of the structural model, the study examined the inner variance inflation factor (VIF) values of the independent variables. According to past studies [105], VIF values ranging from 1.25 to 4.7 are acceptable as they are lower than 5.0, which is the maximum value. The acceptable values indicate the absence of collinearity issues.

5.2. Structural Model

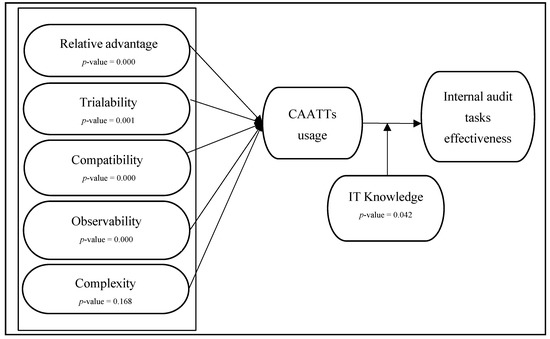

The analysis of the structural model was required for testing the hypotheses regarding the use of CAATTs (see Figure 2). Based on the results, relative advantage, compatibility, trialability, and observability had significant effects on CAATTs use (β = 0.311, p < 0.01, β = 0.252, p < 0.01, β = 0.210, p < 0.01, and β = 0.264, p < 0.01, respectively) but complexity had no effect (β = 0.061, p > 0.05). Added to this, CAATTs use has a significant positive effect on the effectiveness of internal audit tasks (β = 0.237, p < 0.01). Table 4 shows that H1, H3, H4, H5, and H6 are all supported.

Figure 2.

PLS estimate’s.

Table 4.

Result of Hypotheses Testing (Direct Effect).

On the whole, based on the results, the constructs’ path coefficients were significant and robust. Specifically, the path coefficient for the relative advantage to CAATTs use is positive and significant, which indicates support for H1. Based on this result, internal audit managers’ perception of the relative advantage of CAATT use will contribute to enhancing its adoption among internal audit departments.

Moving on to H3, based on the results, there is a positive and significant relationship between compatibility and the use of CAATTs, which shows that CAATTs’ increased compatibility will lead to its increased use. For H4, a positive and significant result was obtained for trialability and its effect on CAATTs use, indicating an increase in such use with the increase in the level of trialability and opportunities for testing. Similarly, observability was found to have a significant positive relationship with CAATTs, which shows that with observability comes CAATTs usage in institutions. There is also a significant positive effect of CAATTs use on internal audit task effectiveness—in other words, using CAATTs would lead to increased effectiveness of internal audit task achievement. The PLS algorithm presents the model with 0.43 explained variances.

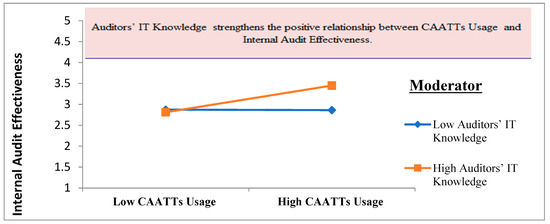

Following the direct effects, the indirect effect model was tested through the application of the interaction effects of IT knowledge on the relationship between CAATTs use and the effectiveness of internal audit task performance. The bootstrap procedure was used with 5000 re-samples [105] and was based on the specifications that acceptable t-values are from 0.963 to 4.27 at the significance level of p < 0.05. In this study, the moderating effect of auditors’ IT knowledge (H6) on the relationship between CAATTs use and internal audit task effectiveness was significant at (t-value = 3.83, p < 0.5) (refer to Figure 2), indicating that the positive effect of the use of CAATTs on the effectiveness of audit tasks is stronger when the auditors’ IT knowledge is of a high level (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Interaction effect between Knowledge Sharing and Employee Engagement.

6. Discussion

The study results found that technological factors have a significant influence over CAATTs use in the public sector institutions of Jordan. More specifically, from the five technological factors, four had a significant influence on such use, including relative advantage, compatibility, observability, and trialability. Moreover, CAATTs use was found to have a significant and positive effect on the audit task effectiveness, with auditors’ IT knowledge as the moderating variable on their relationship.

Specifically, based on the findings, the relative advantages of CAATTs use in the internal departments of Jordanian public sector institutions contribute towards its actual use (H1). As the government of Jordan acknowledges the benefits of CAATTs use among internal audit departments, the relative advantage of such use will follow suite in the people’s perception, and they will be more inclined towards investing in such technology and its adoption. Consistent with the DOI theory assumptions and the findings reported by Chandra and Kumar [60] and Siew et al. [9], the present study findings show that using CAATTs as a novel innovation is beneficial to the departments.

As for CAATTs’ compatibility, it appears that this has a significant and positive effect on their use within the Jordanian public sector internal audit departments (H3). Internal audit departments care about the use of new methods and their fit with the existing procedures and practices. This result means that if the public entity’s values and beliefs as well as their prior experiences are consistent with the process of CAATTs, then a positive mindset is developed concerning its eventual adoption within the audit department. The DOI theory and prior literature [70] argue that CAATT is a unique innovation to be utilized within the departments based on its compatibility.

Additionally, CAATTs trialability has a significant influence over its adoption and use during the COVID-19 pandemic in the public sector of Jordan. This can be attributed to the need of the public sector internal audit departments or any unit for that matter to try the innovation for its usefulness and reliability prior to adopting it. Aside from these variables, observability was also found to have a positive significant effect on using CAATTs during the COVID-19 pandemic in the public sector of Jordan. Apparently, observing other sectors/countries successful CAATTs use mitigates the uncertainty level among internal auditors and increases their likelihood to adopt it. The findings are consistent with the arguments in prior research [9,78,88,91], and DOI theory.

Moreover, on the basis of the obtained results, using CAATTs during the COVID-19 pandemic had a significant effect on the internal audit task effectiveness in the public sector of Jordan. Several challenges and hindrances were faced in internal audit during the pandemic owing primarily to the shift to remote and online working from face-to-face working because of the eventual lockdowns to contain the pandemic. It became necessary to deal with the circumstances and use of online auditing methods. Indubitably, using technology-based auditing enhances the internal audit processes’ effectiveness and capabilities. Consistent with the DOI theory [29] and findings reported by past literature [20], there was a positive CAATTs use–audit effectiveness relationship during and post the COVID-19 pandemic.

As for the indirect effect, specifically the moderating role of IT knowledge on the CAATTs use–internal audit task effectiveness relationship, a positive and significant result was found. This finding shows that the IT knowledge of internal auditors could enhance the use of CAATTs, which enhances the internal audit task effectiveness. Technology availability is useless without its proper usage. In other words, using CAATTs in the internal audit departments of Jordanian public sector institutions would affect their internal audit task effectiveness if their auditors are equipped with IT knowledge—this was particularly true during the COVID-19 pandemic when technology-based auditing processes were required for the shift to online workings.

Only one result in this study was inconsistent with those reported by prior studies—complexity was found to have an insignificant effect on the use of CAATTs in the Jordanian public sector during COVID-19 pandemic. Past studies of this caliber showed the significant negative influence of complexity on technology use and adoption [29,51]. However, other studies [9,41] revealed no relationship between CAATTs use and complexity. This unexpected result may be justified by the fact that this study focuses on the public sector’s internal audit departments, which may differ from other contexts. The majority of the study respondents found complexity to be of little importance to using CAATTs during COVID-19 as opposed to the importance they placed on the rest of the variables (relative advantage, trialability, compatibility, and observability).

Accounting, IS, and auditing studies are extended through the contribution of this study, as it provides evidence concerning the influence of technological factors (compatibility, trialability, relative advantage, and observability) on CAATTs use during the COVID-19 pandemic in the public sector in Jordan, a developing nation. The study similarly contributes to DOI theory [29] by validating its usefulness in explaining CAATTs use in the public sector. In addition, the study extends the literature regarding the moderating role of auditors’ IT knowledge on the relationship between CAATTs use and internal audit task effectiveness. Lastly, within the context of the public sector internal audit department, the majority of the past studies focused on the private sector when studying CAATTs adoption, and none investigated the public sector during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Furthermore, this study has several contributions to the literature, the first of which is the use of CAATTs explained in light of a developing nation, because the majority of the studies have focused on Western developed nations [9,97,101]. The level of importance to the developing nations of past studies thus remains inconsistent, as exemplified by the fact that, in Jordan, CAATTs use is a relative novelty compared to the same use in the UK. The study also contributes to validating the DOI theory in its explanation of the CAATTs use in selecting internal audit settings in the public sector domain. It also contributes by providing insight into the use of CAATTs in public sector internal auditing in Jordan, and, in effect, in other developing nations with similar internal audit processes. The study paves the way for a more in-depth understanding of the technological factors that drive or prevent the use of CAATTs. The study outcomes are expected to guide professional entities on use decisions when it comes to CAATTs among internal auditors. Lastly, the study provides a theoretical framework for a testable model to support CAATTs usage among internal auditors during COVID-19 and in its aftermath.

7. Limitations and Future Research

The limitations of the present study are our presumption that participants will be able to accurately and correctly report different levels of CAATT usage during COVID-19 at the level of an institution, because obtaining the actual use of CAATTs data was not possible. We specifically focused on the envisioning of CAATT adoption in the public sector context because of its unique environment post-COVID-19. Therefore, the results of the current study might not be suitable to be generalized for other contexts. Future research could investigate the adoption of CAATT at a more precise level. For instance, which specific CAATTs are approved by diverse audit firm sizes, such as the Big 4 and local and national companies? How do CAATT tools differ across different customer accounting information system industries in light of COVID-19, such as manufacturing, banking, retail, and hospitals? In addition, future research could consider the determinants of the perception of professional accounting body support post-COVID-19. Future studies need to determine the drivers of the perception of professional accounting bodies support during the pandemic, and this can be done through in-depth qualitative studies and explanation theory.

8. Conclusions

The use of CAATTs in the literature has primarily focused on developed nations, the private sector, and the perspective of external auditors. Despite the importance of CAATTs in developing nations, their adoption remains low, particularly in public sector internal audit departments that have been overlooked. To address this gap in the literature, this paper investigates the factors influencing CAATTs use in Jordan’s public sector internal audit departments. The study found that technological factors significantly influence CAATTs use in Jordan’s public sector institutions. Specifically, four out of the five technological factors, namely relative advantage, compatibility, observability, and trialability, had a significant impact on CAATTs use. Moreover, the study revealed that CAATTs use had a positive and significant effect on the effectiveness of audit tasks. The relationship between the two was moderated by auditors’ IT knowledge.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.A.; Methodology, A.L.; Software, H.A.; Validation, A.L.; Formal analysis, H.A.; Investigation, A.L.; Resources, H.A.; Writing—original draft, H.A.; Writing—review & editing, A.L.; Funding acquisition, A.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors extend their appreciation to the deputyship of Research & Innovation, Ministry of Education in Saudi Arabia for funding this research through project number INST200.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the deanship of the scientific research ethical committee, King Faisal University (project number: INST200, date of approval: 22 December 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available upon request from researchers who meet the eligibility criteria. Kindly contact the first author privately through e-mail.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges the deputyship of Research & Innovation, Ministry of Education in Saudi Arabia for funding this research through project number INST200.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Debreceny, R.; Lee, S.L.; Neo, W.; Toh, J.S. Employing Generalized Audit Software in the Financial Services Sector: Challenges and Opportunities. Manag. Audit. J. 2005, 20, 605–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaber, R.J.; Wadi, R.M.A. Auditors’ usage of computer-assisted audit techniques (caats): Challenges and opportunities. In Proceedings of the Conference on E-Business, E-Services and E-Society, Kuwait City, Kuwait, 30 October–1 November 2018; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 365–375. [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell, E.; Schultz, J.J. The Influence of Business-Process-Focused Audit Support Software on Analytical Procedures Judgments. Audit. J. Pract. Theory 2003, 22, 265–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marei, A.; Iskandar, E.D.T.B.M. The impact of Computer Assisted Auditing Techniques (CAATs) on development of audit process: An assessment of Performance Expectancy of by the auditors. Int. J. Manag. Commer. Innov. 2019, 7, 1199–1205. [Google Scholar]

- Alqudah, H.M.; Amran, N.A.; Hassan, H. Factors Affecting the Internal Auditors’ Effectiveness in the Jordanian Public Sector: The Moderating Effect of Task Complexity. EuroMed J. Bus. 2019, 14, 251–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, R.L.; Davis, H.E. Computer-Assisted Audit Tools and Techniques: Analysis and Perspectives. Manag. Audit. J. 2003, 18, 725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Wang, C.H. A Selection Model for Auditing Software. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2011, 111, 776–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahzan, N.; Lymer, A. Examining the Adoption of Computer-Assisted Audit Tools and Techniques. Manag. Audit. J. 2014, 29, 327–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siew, E.G.; Rosli, K.; Yeow, P.H. Organizational and environmental influences in the adoption of computer-assisted audit tools and techniques (CAATTs) by audit firms in Malaysia. Int. J. Account. Inf. Syst. 2020, 36, 100445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, E.M. Factors Affecting the Adoption of Computer Assisted Audit Techniques in Audit Process: Findings from Jordan. Bus. Econ. Res. 2016, 6, 248–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widuri, R.; O’Connell, B.; Yapa, P.W. Adopting Generalized Audit Software: An Indonesian Perspective. Manag. Audit. J. 2016, 31, 821–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicaksono, A.; Laurens, S.; Novianti, E. Impact Analysis of Computer Assisted Audit Techniques Utilization on Internal Auditor Performance. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Information Management and Technology (ICIMTech), Jakarta, Indonesia, 3–5 September 2018; pp. 267–271. [Google Scholar]

- Bierstaker, J.; Janvrin, D.; Lowe, D.J. What Factors Influence Auditors’ Use of Computer-Assisted Audit Techniques? Adv. Account. 2014, 30, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghanzade, H.; Moradi, M.A.; Raghibi, M. A Survey of Human Factors’ Impacts on the Effectiveness of Accounting Information Systems. Int. J. Bus. Adm. 2011, 2, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khassawneh, A.A.L. The Influence of Organizational Factors on Accounting Information Systems (AIS) Effectiveness: A Study of Jordanian SMEs. Int. J. Mark. Technol. 2014, 4, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Zaitoun, M.; Alqudah, H. The Impact of Liquidity and Financial Leverage on Profitability: The Case of Listed Jordanian Industrial Firm’s. Int. J. Bus. Digit. Econ. 2020, 1, 29–35. [Google Scholar]

- Castka, P.; Searcy, C.; Fischer, S. Technology-Enhanced Auditing in Voluntary Sustainability Standards: The Impact of COVID-19. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutfi, A.; Alkilani, S.Z.; Saad, M.; Alshirah, M.H.; Alshirah, A.F.; Alrawad, M.; Al-Khasawneh, M.A.; Ibrahim, N.; Abdelhalim, A.; Ramadan, M.H. The Influence of Audit Committee Chair Characteristics on Financial Reporting Quality. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2022, 15, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutfi, A.; Alkelani, S.N.; Alqudah, H.; Alshira’h, A.F.; Alshirah, M.H.; Almaiah, M.A.; Alsyouf, A.; Alrawad, M.; Montash, A.; Abdelmaksoud, O. The Role of E-Accounting Adoption on Business Performance: The Moderating Role of COVID-19. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2022, 15, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daoud, L.; Marei, A.; Al-Jabaly, S.; Aldaas, A. Moderating the Role of Top Management Commitment in Usage of Computer-Assisted Auditing Techniques. Accounting 2020, 7, 457–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutfi, A. Understanding the Intention to Adopt Cloud-Based Accounting Information System in Jordanian SMEs. Int. J. Digit. Account. Res. 2022, 22, 47–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, Z.; Khan, I.U.; Islam, T.; Sheikh, Z.; Khan, S.U. Corporate Social Responsibility and Employee Pro-Environmental Behaviors: The Role of Perceived Organizational Support and Organizational Pride. South Asian J. Bus. Stud. 2019, 8, 246–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqudah, H.M. Factors Affecting Internal Audit Effectiveness Jordanian Public Sector: Moderating Effect of Task Complexity. Ph.D. Thesis, University Utara Malaysia, Kedah, Malaysia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Saad, M.; Lutfi, A.; Almaiah, M.; Alshira’h, A.; Alshirah, M.; Alqudah, H.; Alkhassawneh, A.; Alsyouf, A.; Alrawad, M.; Abdelmaksoud, O. Assessing the Intention to Adopt Cloud Accounting during COVID-19. Electronics 2022, 11, 4092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norwahida, H.; Shukeri, B. The Role of Data Quality and Internal Control in Raising the Effectiveness of Ais in Jordan Companies. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Res. 2014, 3, 298–303. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Khasawneh, A.; Eyadat, H.; Elayan, M. The Preferred Leadership Styles in Vocational Training Corporations: Case of Jordan. Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2021, 19, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E.M. Diffusion of Innovations: Modifications of a model for telecommunications. In Die Diffusion von Innovationen in der Telekommunikation; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1995; pp. 25–38. [Google Scholar]

- Idris, K.M.; Mohamad, R. The influence of technological, organizational and environmental factors on accounting information system usage among Jordanian small and medium-sized enterprises. Int. J. Econ. Financ. Issues 2016, 6, 240–248. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, G.C.; Benbasat, I. Development of an Instrument to Measure the Perceptions of Adopting an Information Technology Innovation. Inf. Syst. Res. 1991, 2, 192–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fichman, R.G. Going beyond the dominant paradigm for information technology innovation research: Emerging concepts and methods. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2004, 5, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoti, E. Complexity and Timing of Technological Innovation in Small and Medium Enterprises and Their Relationship to External Communication and Organizational Activities. Proc. ICABR 2015, 2015, 335. [Google Scholar]

- AlQudah, N.F.; Mathani, B.; Aldiabat, K.; Alshakary, K.; Alqudah, H.M. Knowledge Sharing and Self-Efficacy Role in Growing Managers’ Innovation: Does Job Satisfaction Matter? Hum. Syst. Manag. 2022, 41, 643–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmi, A.; Saidin, S.Z.; Abdullah, A. IT adoption by internal auditors in public sector: A conceptual study. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 164, 591–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omonuk, J. Computer Assisted Audit Techniques and Audit Quality in Developing Countries: Evidence from Nigeria. J. Internet Bank. Commer. 2015, 20, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Janvrin, D.; Bierstaker, J.; Lowe, D.J. An Investigation of Factors Influencing the Use of Computer-Related Audit Procedures. J. Inf. Syst. 2009, 23, 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrosa, I.; Costa, C.J.; Aparicio, M. Determinants adoption of computer-assisted auditing tools (CAATs). Cogn. Technol. Work. 2019, 22, 565–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedard, J.C.; Graham, L.E. The Effects of Decision Aid Orientation on Risk Factor Identification and Audit Test Planning. Audit. J. Pract. Theory 2002, 21, 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javnrin, D.J.B.; Bierstaker, J.; Lowe, J.L. An Examination of Audit Information Technology Use and Perceived Importance. Account. Horiz. 2008, 22, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Paukowits, F. Bridging CAATTS and Risk. Intern. Audit. 2000, 57, 27. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson, M.E. CAATTs and Compliance. Intern. Audit. 1998, 55, 25–27. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S.-M.; Hung, Y.-C.; Tsao, H.-H. Examining the determinants of computer-assisted audits techniques acceptance from internal auditors viewpoints. Int. J. Serv. Stand. 2008, 4, 377–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Mannino, M.; Nieschwietz, R.J. Information Technology Acceptance in the Internal Audit Profession: Impact of Technology Features and Complexity. Int. J. Account. Inf. Syst. 2009, 10, 214–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahzan, N.; Lymer, A. Adoption of computer assisted audit tools and techniques (CAATTs) by internal auditors: Current issues in the UK. In Proceedings of the 1st Global Academic Conference on International Audit and Corporate Governance, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 20–22 April 2008; pp. 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, G.C.; Sharma, P.N.; Galletta, D.F. The Antecedents of the Use of Continuous Auditing in the Internal Auditing Context. Int. J. Account. Inf. Syst. 2012, 13, 248–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, M.; Hulland, J. The Resource-Based View and Information Systems Research: Review, Extension, and Suggestions for Future Research. MIS Q. 2004, 28, 107–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behaviour. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User Acceptance of Information Technology: Toward a Unified View. MIS Q. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornatzky, L.G.; Klein, K.J. Innovation Characteristics and Innovation Adoption-Implementation: A Meta-Analysis of Findings. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 1982, EM-29, 28–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coderre, D. Internal Audit: Efficiency through Automation; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E.M. Diffusion of Innovations, 5th ed.; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Pole, J.D.; Bondy, S.J. Control Variables. In Encyclopedia of Research Design; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2010; pp. 253–255. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M.; Abdullah, Z.; Abdul Razak, R. The Diffusion of Technological and Management Accounting Innovation: Malaysian Evidence. Asian Rev. Account. 2008, 16, 197–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, J.T. Diffusion of innovations and HIV/AIDS. J. Health Commun. 2004, 9, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, G.D.; Grover, V. Types of Information Technology Capabilities and Their Role in Competitive Advantage: An Empirical Study. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2005, 22, 253–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, H.; Liu, S.; Zhang, J.; Deng, Z. Information Technology Resource, Knowledge Management Capability, and Competitive Advantage: The Moderating Role of Resource Commitment. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2016, 36, 1062–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsyouf, A.; Ishak, A.K. Acceptance of Electronic Health Record System among Nurses: The Effect of Technology Readiness. Asian J. Inf. Technol. 2017, 16, 414–421. [Google Scholar]

- Alsyouf, A. Mobile Health for COVID-19 Pandemic Surveillance in Developing Countries: The Case of Saudi Arabia. Solid State Technol 2020, 63, 2474–2485. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, K.Y.; Cruickshank, D.; Anderson, A.R. The Adoption of E-Trade Innovations by Korean Small and Medium Sized Firms. Technovation 2009, 29, 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, S.; Kumar, K.N. Exploring Factors Influencing Organizational Adoption of Augmented Reality in E-Commerce: Empirical Analysis Using Technology-Organization-Environment Model. J. Electron. Commer. Res. 2018, 19, 237–265. [Google Scholar]

- Almaiah, M.A.; Al-Rahmi, A.M.; Alturise, F.; Alrawad, M.; Alkhalaf, S.; Al-Rahmi, W.M.; Awad, A.B. Factors Influencing the Adoption of Internet Banking: An Integration of ISSM and UTAUT with Price Value and Perceived Risk. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 919198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hiyari, A.; Al Said, N.; Hattab, E. Factors That Influence the Use of Computer Assisted Audit Techniques (CAATs) by Internal Auditors in Jordan. Acad. Account. Financ. Stud. J. 2019, 23, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Lutfi, A.; Alrawad, M.; Alsyouf, A.; Almaiah, M.A.; Al-Khasawneh, A.; Al-Khasawneh, A.L.; Alshira’h, A.F.; Alshirah, M.H.; Saad, M.; Ibrahim, N. Drivers and Impact of Big Data Analytic Adoption in the Retail Industry: A Quantitative Investigation Applying Structural Equation Modeling. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 70, 103129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshamaila, Y.; Papagiannidis, S.; Li, F. Cloud Computing Adoption by SMEs in the North East of England: A Multi-Perspective Framework. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2013, 26, 250–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandil, A.M.N.A.; Ragheb, M.A.; Ragab, A.A.; Farouk, M. Examining the Effect of TOE Model on Cloud Computing Adoption in Egypt. Bus. Manag. Rev. 2018, 9, 113–123. [Google Scholar]

- Alsyouf, A.; Alsubahi, N.; Alhazmi, F.N.; Al-Mugheed, K.; Anshasi, R.J.; Alharbi, N.I.; Albugami, M. The Use of a Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) to Predict Patients’ Usage of a Personal Health Record System: The Role of Security, Privacy, and Usability. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2023, 20, 1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsyouf, A.; Ishak, A.K. Understanding EHRs Continuance Intention to Use from the Perspectives of UTAUT: Practice Environment Moderating Effect and Top Management Support as Predictor Variables. Int. J. Electron. Healthc. 2018, 10, 24–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harindranath, G.; Dyerson, R.; Barnes, D. ICT in Small Firms: Factors Affecting the Adoption and Use of ICT in Southeast England SMEs. In Proceedings of the 16th European Conference on Information Systems, ECIS 2008, Galway, Ireland, 9–11 June 2008; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Asiaei, A.; Rahim, N.Z. A Multifaceted Framework for Adoption of Cloud Computing in Malaysian SMEs. J. Sci. Technol. Policy Manag. 2019, 10, 708–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutfi, A.; Alsyouf, A.; Almaiah, M.A.; Alrawad, M.; Abdo, A.A.K.; Al-Khasawneh, A.L.; Ibrahim, N.; Saad, M. Factors Influencing the Adoption of Big Data Analytics in the Digital Transformation Era: Case Study of Jordanian SMEs. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaiah, M.A.; Al-Rahmi, A.; Alturise, F.; Hassan, L.; Alrawad, M.; Alkhalaf, S.; Al-Rahmi, W.M.; Al-sharaieh, S.; Aldhyani, T.H.H. Investigating the Effect of Perceived Security, Perceived Trust, and Information Quality on Mobile Payment Usage through Near-Field Communication (NFC) in Saudi Arabia. Electronics 2022, 11, 3926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangwar, H. Understanding the Determinants of Big Data Adoption in India: An Analysis of the Manufacturing and Services Sectors. Inf. Resour. Manag. J. IRMJ 2018, 31, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.; Sun, H.; Ren, J. Understanding the Determinants of Big Data Analytics (BDA) Adoption in Logistics and Supply Chain Management: An Empirical Investigation. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2018, 29, 676–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.S.; Chong, S.C.; Lin, B.; Eze, U.C. Internet-Based ICT Adoption: Evidence from Malaysian SMEs. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2009, 109, 224–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrawashdeh, N.; Alsmadi, A.A.; Anwar, A.L. FinTech: A Bibliometric Analysis for the Period of 2014–2021. Qual Access Success 2022, 23, 176–188. [Google Scholar]

- Morteza, G.; Daniel, A.A.; Jose, B.A. Adoption of e-commerce applications in SMEs. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2011, 111, 1238–1269. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya, M.; Wamba, S.F. A conceptual framework of RFID adoption in retail using TOE framework. In Technology Adoption and Social Issues: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools, and Applications; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2018; pp. 69–102. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, C.-Y.; Chen, S.; Chen, C.-L. An Integrated Perspective of TOE Framework and Innovation Diffusion in Broadband Mobile Applications Adoption by Enterprises. Int. J. Manag. Econ. Soc. Sci. IJMESS 2017, 6, 14–39. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, H.; Skournetou, D.; Hyppölä, J.; Laukkanen, S.; Heikkilä, A. Drivers and Bottlenecks in the Adoption of Augmented Reality Applications. J. ISSN 2014, 2368, 5956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.; Kraemer, K.L.; Xu, S. The Process of Innovation Assimilation by Firms in Different Countries: A Technology Diffusion Perspective on E-Business. Manag. Sci. 2006, 52, 1557–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramdani, B.; Kawalek, P.; Lorenzo, O. Predicting SMEs’ Adoption of Enterprise Systems. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2009, 22, 10–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrawd, M.; Lutf, A.; Almaieh, M.A.; Alsyouf, A.; Al-Khasawneh, A.L.; Arafa, H.M.; Ahmed, N.A.; AboAlkhair, A.M.; Tork, M. Managers’ Perception and Attitude toward Financial Risks Associated with SMEs: Analytic Hierarchy Process Approach. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2023, 16, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaiah, M.A.; Alfaisal, R.; Salloum, S.A.; Al-Otaibi, S.; Al Sawafi, O.S.; Al-Maroof, R.S.; Lutfi, A.; Alrawad, M.; Mulhem, A.A.; Awad, A.B. Determinants Influencing the Continuous Intention to Use Digital Technologies in Higher Education. Electronics 2022, 11, 2827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaiah, M.A.; Hajjej, F.; Al-Khasawneh, A.; Alkhdour, T.; Almomani, O.; Shehab, R. A Conceptual Framework for Determining Quality Requirements for Mobile Learning Applications Using Delphi Method. Electronics 2022, 11, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabaai, A.; Al-lozi, E.; Hammouri, Q.; Muhammad, N.; Alsmadi, A.; Al-Gasawneh, J. Continuance Intention to Use Smartwatches: An Empirical Study. Int. J. Data Netw. Sci. 2022, 6, 1643–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsmadi, A.; Al-Gasaymeh, A.; Alrawashdeh, N.; Alhwamdeh, L. Financial Supply Chain Management: A Bibliometric Analysis for 2006-2022. Uncertain Supply Chain Manag. 2022, 10, 645–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, K.K.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Williams, M.D. Rogers’ Innovation Adoption Attributes: A Systematic Review and Synthesis of Existing Research. Inf. Syst. Manag. 2014, 31, 74–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakar, A.R.; Ahmad, S.Z.; Ahmad, N. SME Social Media Use: A Study of Predictive Factors in the United Arab Emirates. Glob. Bus. Organ. Excell. 2019, 38, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochieng, G.F. The Adoption of Big Data Analytics by Supermarkets in Kisumu County. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ramdani, B.; Kawalek, P. SME Adoption of Enterprise Systems in the Northwest of England. In Proceedings of the IFIP International Working Conference on Organizational Dynamics of Technology-Based Innovation, Manchester, UK, 14–16 June 2007; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2007; pp. 409–429. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, S.; Cegielski, C.G.; Jia, L.; Hall, D.J. Understanding the Factors Affecting the Organizational Adoption of Big Data. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2018, 58, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baig, M.I.; Shuib, L.; Yadegaridehkordi, E. Big Data Adoption: State of the Art and Research Challenges. Inf. Process. Manag. 2019, 56, 102095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroufkhani, P.; Tseng, M.L.; Iranmanesh, M.; Ismail, W.K.W.; Khalid, H. Big data analytics adoption: Determinants and performances among small to medium-sized enterprises. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 54, 102190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J. Information Technology Auditing, International, 3rd ed.; Cengage: Mason, OH, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Alkhazaleh, A.M.K.; Marei, A. Would irregular auditing implements impact the quality of financial reports: Case study in jordan practice. J. Manag. Inf. Decis. Sci. 2021, 24, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Dowling, C.; Leech, S. Audit Support Systems and Decision Aids: Current Practice and Opportunities for Future Research. Int. J. Account. Inf. Syst. 2007, 8, 92–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, M.B.; Payne, E.A. An examination of contextual factors and individual characteristics affecting technology implementation decisions in auditing. Int. J. Account. Inf. Syst. 2008, 9, 104–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil Abdo, A.A.; Ibrahim, N.M.E. Effect of Adopting the Criterion of Revenue from Contracts with Clients on Accounting Conservatism. In Artificial Intelligence for Sustainable Finance and Sustainable Technology. ICGER 2021; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Shatnawi, S.; Marei, A.; Daoud, L.; Alkhodary, D.; Shehadeh, M. Effectiveness of the Board of Directors’ Performance in Jordan: The Moderating Effect of Enterprise Risk Management. Int. J. Data Netw. Sci. 2022, 6, 823–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharasis, E.E.; Tarawneh, A.S.; Shehadeh, M.; Haddad, H.; Marei, A.; Hasan, E.F. Reimbursement Costs of Auditing Financial Assets Measured by Fair Value Model in Jordanian Financial Firms’ Annual Reports. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmi, A.; Kent, S. The Utilisation of Generalized Audit Software (GAS) by External Auditors. Manag. Audit. J. 2013, 28, 88–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merhout, J.W.; Buchman, S.E. Requisite Skills and Knowledge for Entry-Level IT Auditors. J. Inf. Syst. Educ. 2007, 18, 469. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Ansi, A.A.; Ismail, N.A.B.; Al-Swidi, A.K. The Effect of IT Knowledge and IT Training on the IT Utilization among External Auditors: Evidence from Yemen. Asian Soc. Sci. 2013, 9, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khasawneh, A.L.; Al-Jammal, H.R.; Najadat, A.M.; Ababneh, A.M. Extent of Applicability of Requisites for Excellence and Obstacles Encountered by Jordanian Private Universities: Empirical Study in Northern Region of Jordan. Eur. J. Econ. Finance Adm. Sci. 2012, 50, 52. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. Rethinking Some of the Rethinking of Partial Least Squares. Eur. J. Mark. 2019, 53, 566–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Partial Least Squares: The Better Approach to Structural Equation Modeling? Long Range Plan 2012, 45, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukey, J.W. Exploratory Data; Analysis Addison Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Khasawneh, A.L.; Eyadat, H.M.; Alrawad, M.; Almaiah, M.; Lutfi, A.A. The Impact of Organizational Training Operations Management on Job Performance: An Empirical Study on Jordanian Government Institutions. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2022, 09721509221133514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Khattab, A.; Aldehayyat, J.; Alrawad, M.; Al-Yatama, S.; Al Khattab, S. Executives’ Perception of Political-Legal Business Environment in International Projects. Int. J. Commer. Manag. 2012, 22, 168–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rawad, M.; Al Khattab, A. Risk Perception in a Developing Country: The Case of Jordan. Int. Bus. Res. 2015, 8, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillside, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Goodhue, D.L.; Lewis, W.; Thompson, R. Statistical Power in Analyzing Interaction Effects: Questioning the Advantage of PLS with Product Indicators. Inf. Syst. Res. 2007, 18, 211–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sax, L.J.; Gilmartin, S.K.; Bryant, A.N. Assessing Response Rates and Nonresponse Bias in Web and Paper Surveys. Res. High. Educ. 2003, 44, 409–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Syouf, A. Personality, Top Management Support, Continuance Intention to Use Electronic Health Record System among Nurses in Jordan. Ph.D. Thesis, Universiti Utara Malaysia, Changlun, Malaysia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]