The Impact of Mental Health Leadership on Teamwork in Healthcare Organizations: A Serial Mediation Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Health-Oriented Leadership

1.2. Leadership and Interpersonal Conflict

1.3. Leadership and Coordination

1.4. Leadership and Teamwork

1.5. Study Hypothesis

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Measures

2.2. Participants

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Statistical Analysis

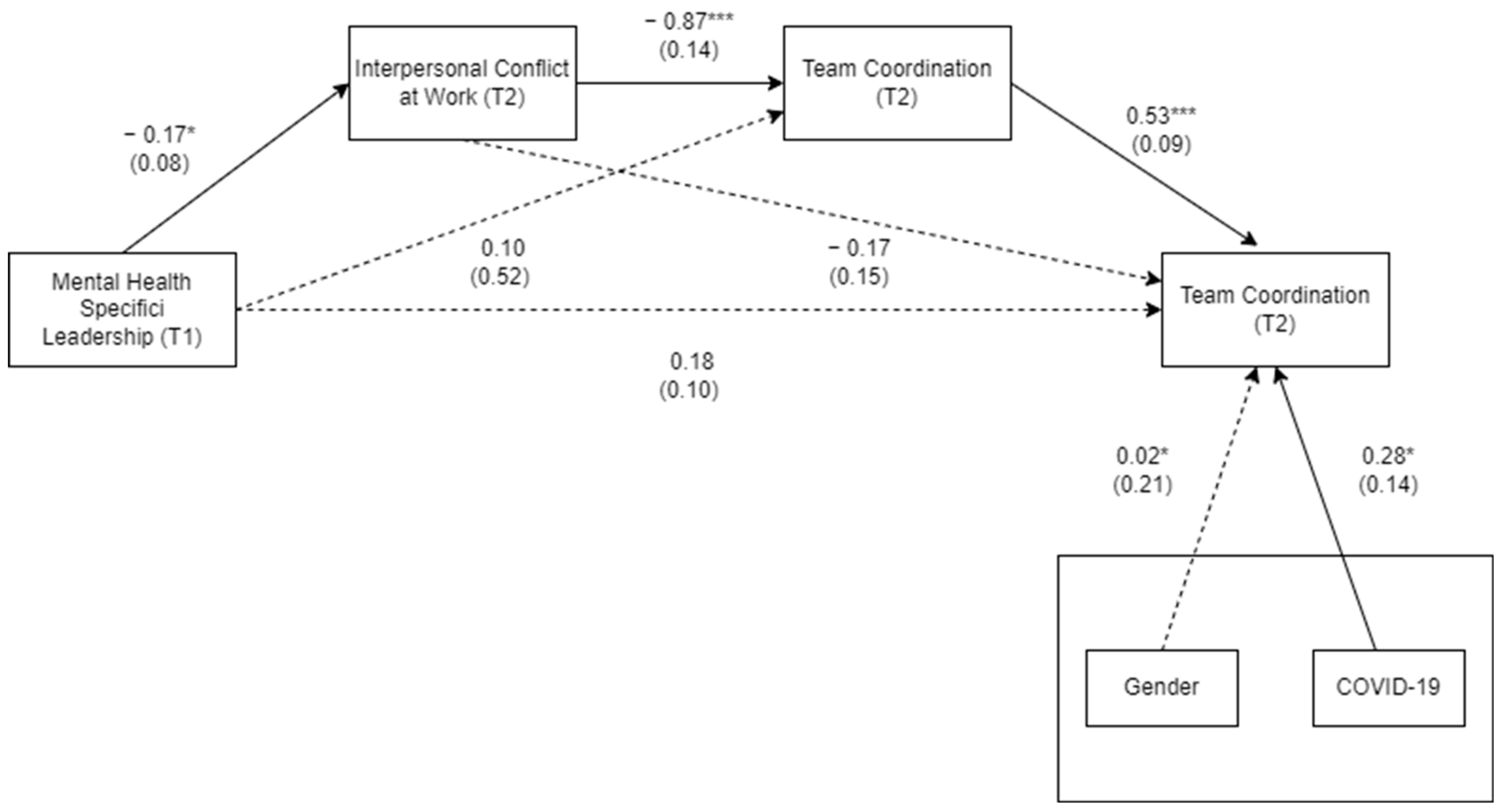

3. Results

Descriptive Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Di Fabio, A.; Rosen, M.A. Opening the Black Box of Psychological Processes in the Science of Sustainable Development: A New Frontier. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. Res. 2018, 2, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fabio, A.; Rosen, M.A. An Exploratory Study of a New Psychological Instrument for Evaluating Sustainability: The Sustainable Development Goals Psychological Inventory. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fabio, A.; Peiró, J.M. Human Capital Sustainability Leadership to Promote Sustainable Development and Healthy Organizations: A New Scale. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frykman, M.; Von Thiele Schwarz, U.; Athlin, Å.M.; Hasson, H.; Mazzocato, P. The Work Is Never Ending: Uncovering Teamwork Sustainability Using Realistic Evaluation. J. Health Organ. Manag. 2017, 31, 64–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheeler, D.; Stoller, J.K. Teamwork, Teambuilding and Leadership in Respiratory and Health Care. Can. J. Respir. Ther. 2011, 47, 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Sicotte, C.; Pineault, R.; Lambert, J. Medical Team Interdipendence as a Determinant of Use of Clinical Resources. Health Serv. Res. 1993, 28, 599–621. [Google Scholar]

- Sohmen, V. Two Sides of the Same Coin? Leadership and Organizational Culture. J. IT Econ. Dev. 2013, 4, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Luceño, L.; Talavera, B.; Yolanda, G.; Martín, J. Symptoms of Posttraumatic Stress, Anxiety, Depression, Levels of Resilience and Burnout in Spanish Health Personnel during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicola, M.; Sohrabi, C.; Mathew, G.; Kerwan, A.; Al-Jabir, A.; Griffin, M.; Agha, M.; Agha, R. Health Policy and Leadership Models during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Review. Int. J. Surg. 2020, 81, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, S.R.; Bruursema, K.; Rodopman, B.; Spector, P.E. Leadership, Interpersonal Conflict, and Counterproductive Work Behavior: An Examination of the Stressor-Strain Process. Negot. Confl. Manag. Res. 2013, 6, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, K. The Impact of Interpersonal Conflict on Team Performance. In Conflict and Problem Solving in Small Groups; Radtke, T., Ed.; Maricopa Open Digital Press: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Jerng, J.S.; Huang, S.F.; Liang, H.W.; Chen, L.C.; Lin, C.K.; Huang, H.F.; Hsieh, M.Y.; Sun, J.S. Workplace Interpersonal Conflicts among the Healthcare Workers: Retrospective Exploration from the Institutional Incident Reporting System of a University-Affiliated Medical Center. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0171696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valentine, M.A.; Nembhard, I.M.; Edmondson, A.C. Measuring Teamwork in Health Care Settings a Review of Survey Instruments. Med. Care 2015, 53, e16–e30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akerjordet, K.; Furunes, T.; Haver, A. Health-Promoting Leadership: An Integrative Review and Future Research Agenda. J. Adv. Nurs. 2018, 74, 1505–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adler, A.B.; Saboe, K.N.; Anderson, J.; Sipos, M.L.; Thomas, J.L. Behavioral Health Leadership: New Directions in Occupational Mental Health. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2014, 16, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunkl, A.; Jiménez, P.; Šarotar Žižek, S.; Milfelner, B.; Kallus, W.K. Similarities and Differences of Health-Promoting Leadership and Transformational Leadership. Naše Gospod./Our Econ. 2015, 61, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsarouha, E.; Stuber, F.; Seifried-Dübon, T.; Radionova, N.; Schnalzer, S.; Nikendei, C.; Genrich, M.; Worringer, B.; Stiawa, M.; Mulfinger, N.; et al. Reflection on Leadership Behavior: Potentials and Limits in the Implementation of Stress-Preventive Leadership of Middle Management in Hospitals—A Qualitative Evaluation of a Participatory Developed Intervention. J. Occup. Med. Toxicol. 2021, 16, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, R.N.J.; Woodhead, T. Leadership for Continuous Improvement in Healthcare during the Time of COVID-19. Clin. Radiol. 2021, 76, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas-Vallina, A.; Ferrer-Franco, A.; Herrera, J. Fostering the Healthcare Workforce during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Shared Leadership, Social Capital, and Contagion among Health Professionals. Int. J. Health Plan. Manag. 2020, 35, 1606–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent-Höper, S.; Teetzen, F.; Gregersen, S.; Nienhaus, A. Leadership and Employee Well-Being. In Research Handbook on Work and Well-Being; Burke, R.J., Page, K.M., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2017; pp. 269–291. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez, P.; Winkler, B.; Dunkl, A. Creating a Healthy Working Environment with Leadership: The Concept of Health-Promoting Leadership. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 28, 2430–2448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franke, F.; Felfe, J.; Pundt, A. The Impact of Health-Oriented Leadership on Follower Health: Development and Test of a New Instrument Measuring Health-Promoting Leadership. Ger. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. Z. Für Pers. 2014, 28, 139–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skakon, J.; Nielsen, K.; Borg, V.; Guzman, J. Are Leaders’ Well-Being, Behaviours and Style Associated with the Affective Well-Being of Their Employees? A Systematic Review of Three Decades of Research. Work Stress 2010, 24, 107–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elprana, G.; Jorg, F.; Franke, F. Gesundheitsförderliche Führung Diagnostizieren Und Umsetzen. In Handbuch Mitarbeiterführung; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 143–156. [Google Scholar]

- Franke, F.; Felfe, J. How Does Transformational Leadership Impact Employees’ Psychological Strain? Examining Differentiated Effects and the Moderating Role of Affective Organizational Commitment. Leadership 2011, 7, 295–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, K.; Randall, R.; Yarker, J.; Brenner, S.O. The Effects of Transformational Leadership on Followers’ Perceived Work Characteristics and Psychological Well-Being: A Longitudinal Study. Work Stress 2008, 22, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, M. Impact of Interpersonal Conflict in Health Care Setting on Patient Care; the Role of Nursing Leadership Style on Resolving the Conflict. Nurs. Care Open Access J. 2017, 2, 44–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Cao, Q.; Tjosvold, D. Linking Transformational Leadership and Team Performance: A Conflict Management Approach. J. Manag. Stud. 2011, 48, 1586–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKibben, L. Conflict Management: Importance and Implications. Br. J. Nurs. 2017, 26, 100–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Men, C.; Huo, W.; Wang, J. Who Will Pay for Customers’ Fault? Workplace Cheating Behavior, Interpersonal Conflict and Traditionality. Pers. Rev. 2022, 51, 1672–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sliter, M.T.; Pui, S.Y.; Sliter, K.A.; Jex, S.M. The Differential Effects of Interpersonal Conflict from Customers and Coworkers: Trait Anger as a Moderator. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2011, 16, 424–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barki, H.; Hartwick, J. Conceptualizing the Construct of Interpersonal Conflict. Int. J. Confl. Manag. 2004, 15, 216–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jehn, K.A.; Bendersky, C. Intragroup Conflict in Organizations: A Contingency Perspective on the Conflict-Outcome Relationship. Res. Organ. Behav. 2003, 25, 187–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez Castelao, E.; Russo, S.G.; Riethmüller, M.; Boos, M. Effects of Team Coordination during Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation: A Systematic Review of the Literature. J. Crit. Care 2013, 28, 504–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Li, G. Linking Transformational Leadership and Knowledge Sharing: The Mediating Roles of Perceived Team Goal Commitment and Perceived Team Identification. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manser, T. Teamwork and Patient Safety in Dynamic Domains of Healthcare: A Review of the Literature. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 2009, 53, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, M.C.; Phillips-Bute, B.G.; Petrusa, E.R.; Griffin, K.L.; Hobbs, G.W.; Taekman, J.M. Assessing Teamwork in Medical Education and Practice: Relating Behavioural Teamwork Ratings and Clinical Performance. Med. Teach. 2009, 31, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanini, A.; Aloini, D.; Gloor, P. Silence Is Golden: The Role of Team Coordination in Health Operations. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2020, 40, 1421–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, D.C.; Benzer, J.K.; Vimalananda, V.G.; Singer, S.J.; Meterko, M.; McIntosh, N.; Harvey, K.L.L.; Seibert, M.N.; Charns, M.P. Organizational Coordination and Patient Experiences of Specialty Care Integration. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2019, 34, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmutz, J.B.; Meier, L.L.; Manser, T. How Effective Is Teamwork Really? The Relationship between Teamwork and Performance in Healthcare Teams: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e028280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavelle, M.; Darzi, A.; Starodub, R.; Anderson, J.E. The Role of Transactive Memory Systems, Psychological Safety and Interpersonal Conflict in Hospital Team Performance. Ergonomics 2022, 65, 519–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.R.; Huang, C.F.; Wu, K.S. The Association among Project Manager’s Leadership Style, Teamwork and Project Success. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2011, 29, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montes, F.J.L.; Ruiz Moreno, A.; García Morales, V. Influence of Support Leadership and Teamwork Cohesion on Organizational Learning, Innovation and Performance: An Empirical Examination. Technovation 2005, 25, 1159–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, T.H.; Rathert, C.; Ayad, S.; Messina, N. A One-Team Approach to Crisis Management: A Hospital Success Story during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Hosp. Manag. Health Policy 2021, 5, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuber, F.; Seifried-Dübon, T.; Rieger, M.A.; Gündel, H.; Ruhle, S.; Zipfel, S.; Junne, F. The Effectiveness of Health-Oriented Leadership Interventions for the Improvement of Mental Health of Employees in the Health Care Sector: A Systematic Review. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2021, 94, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosen, M.A.; DiazGranados, D.; Dietz, A.S.; Benishek, L.E.; Thompson, D.; Pronovost, P.J.; Weaver, S.J. Teamwork in Healthcare: Key Discoveries Enabling Safer, High-Quality Care. Am. Psychol. 2018, 73, 433–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heath, C.; Staudenmayer, N. Coordination Neglect: How Lay Theories of Organizing Complicate Coordination in Organizations. Res. Organ. Behav. 2000, 22, 153–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migotto, S.; Garlatti Costa, G.; Ambrosi, E.; Pittino, D.; Bortoluzzi, G.; Palese, A. Gender Issues in Physician–Nurse Collaboration in Healthcare Teams: Findings from a Cross-Sectional Study. J. Nurs. Manag. 2019, 27, 1773–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurt, J.; Schwennen, C.; Elke, G. Health-Specific Leadership: Is There an Association between Leader Consideration for the Health of Employees and Their Strain and Well-Being? Work Stress 2011, 25, 108–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, R.A.; Tidd, S.T.; Currall, S.C.; Tsai, J.C. What Goes around Comes around: The Impact of Personal Conflict Style on Work Conflict and Stress. Int. J. Confl. Manag. 2000, 11, 32–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salanova, M.; Cifre, E.; Llorens, S.; Martínez, I.M.; Lorente, L. Psychosocial Risks and Positive Factors among Construction Workers. In Occupational Health and Safety; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Salanova, M.; Llorens, S.; Cifre, E.; Martínez, I.M. Metodología RED-WoNT. In Perspectivas de Intervención en Riesgos Psicosociales; Departamento de Psicología Evolutiva, Educativa, Social y Metodología de la Universidad Jaume I de Castellón: Barcelona, Spain, 2006; p. 290. [Google Scholar]

- De Angelis, M.; Giusino, D.; Nielsen, K.; Aboagye, E.; Christensen, M.; Innstrand, S.T.; Mazzetti, G.; van den Heuvel, M.; Sijbom, R.B.L.; Pelzer, V.; et al. H-Work Project: Multilevel Interventions to Promote Mental Health in Smes and Public Workplaces. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. SPSS and SAS Procedures for Estimating Indirect Effects in Simple Mediation Models. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 2004, 36, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole, M.S.; Walter, F.; Bruch, H. Affective Mechanisms Linking Dysfunctional Behaviour to Performance in Work Teams: A Moderated Mediation Study. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 945–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeVellis, R.F.; Thorpe, C.T. Scale Development: Theory and Applications; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Elkomy, S.; Murad, Z.; Veleanu, V. Does Leadership Matter for Healthcare Service Quality? Evidence from NHS England. Int. Public Manag. J. 2023, 26, 147–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grubaugh, M.L.; Flynn, L. Relationships among Nurse Manager Leadership Skills, Conflict Management, and Unit Teamwork. J. Nurs. Adm. 2018, 48, 383–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doucet, O.; Poitras, J.; Chênevert, D. The Impacts of Leadership on Workplace Conflicts. Int. J. Confl. Manag. 2009, 20, 340–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoch, J.E.; Pearce, C.L.; Welzel, L. Is the Most Effective Team Leadership Shared? The Impact of Shared Leadership, Age Diversity, and Coordination on Team Performance. J. Pers. Psychol. 2010, 9, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, P.; Bregenzer, A.; Kallus, K.W.; Fruhwirth, B.; Wagner-Hartl, V. Enhancing Resources at the Workplace with Health-promoting Leadership. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, L.; Li, P.; Wildy, H. Health-Promoting Leadership: Concept, Measurement, and Research Framework. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 602333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klug, K.; Felfe, J.; Krick, A. Caring for Oneself or for Others? How Consistent and Inconsistent Profiles of Health-Oriented Leadership Are Related to Follower Strain and Health. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almost, J.; Wolff, A.C.; Stewart-Pyne, A.; McCormick, L.G.; Strachan, D.; D’Souza, C. Managing and Mitigating Conflict in Healthcare Teams: An Integrative Review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2016, 72, 1490–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, M.B.; Tolsgaard, M.G.; Dieckmann, P.; Østergaard, D.; White, J.; Plenge, P.; Ringsted, C.V. Social Ties Influence Teamwork When Managing Clinical Emergencies. BMC Med. Educ. 2020, 20, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Parker, S.H.; Manser, T. Teamwork and Collaboration. Rev. Hum. Factors Ergon. 2013, 8, 55–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehder, K.J.; Adair, K.C.; Eckert, E.; Lang, R.W.; Frankel, A.S.; Proulx, J.; Sexton, B. Teamwork before and during COVID-19: The Good, the Same, and the Ugly…. J. Patient Saf. 2023, 19, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordan, P.J.; Troth, A.C. Common Method Bias in Applied Settings: The Dilemma of Researching in Organizations. Aust. J. Manag. 2020, 45, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mean/ Freq. | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | 79% (F) | - | - | |||||

| 2. COVID-19 Impact on Work | 2.56 | 0.70 | −0.19 * | (0.75) | ||||

| 3. Mental Health-Specific Leadership T1 (Mhsl1) | 1.12 | 0.94 | −0.02 | 0.04 | (0.95) | |||

| 4. Interpersonal Conflict at Work T2 (ICW2) | 2.87 | 0.72 | 0.04 | −0.18 | −0.22 * | (0.89) | ||

| 5. Team Coordination T2 (TC2) | 3.76 | 1.15 | 0.06 | 0.14 | 0.21 * | −0.55 ** | (0.82) | |

| 6. Teamwork T2 (Tw2) | 3.51 | 1.16 | 0.01 | 0.20 * | 0.30 ** | −0.48 ** | 0.64 ** | (0.79) |

| Indirect Effects Health-Promoting Leadership (HpL) | Est. | SE | CI 95% |

|---|---|---|---|

| MHSL → ICW → TW | 0.16 | 0.03 | (−0.02, 0.11) |

| MHSL → TC → TW | 0.03 | 0.08 | (−0.05, 0.17) |

| MHSL → ICW → TC → TW | 0.08 | 0.05 | (0.01, 0.18) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Paganin, G.; De Angelis, M.; Pische, E.; Violante, F.S.; Guglielmi, D.; Pietrantoni, L. The Impact of Mental Health Leadership on Teamwork in Healthcare Organizations: A Serial Mediation Study. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7337. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097337

Paganin G, De Angelis M, Pische E, Violante FS, Guglielmi D, Pietrantoni L. The Impact of Mental Health Leadership on Teamwork in Healthcare Organizations: A Serial Mediation Study. Sustainability. 2023; 15(9):7337. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097337

Chicago/Turabian StylePaganin, Giulia, Marco De Angelis, Edoardo Pische, Francesco Saverio Violante, Dina Guglielmi, and Luca Pietrantoni. 2023. "The Impact of Mental Health Leadership on Teamwork in Healthcare Organizations: A Serial Mediation Study" Sustainability 15, no. 9: 7337. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097337

APA StylePaganin, G., De Angelis, M., Pische, E., Violante, F. S., Guglielmi, D., & Pietrantoni, L. (2023). The Impact of Mental Health Leadership on Teamwork in Healthcare Organizations: A Serial Mediation Study. Sustainability, 15(9), 7337. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097337