Abstract

The study examines the crisis resilience of startup companies in Hungary among the Visegrad countries as a result of the pandemic situation. It aims to provide guidance on what support is needed for startups in the post-crisis period to re-launch the economy and to contribute to the region’s economy with positive results. The research was carried out in two stages: first, in 2021 through an online survey, and then, in 2022 in-depth interviews due to the economic crisis caused by COVID-19 and the Russian–Ukrainian war. A mixed research methodology was used, which comprised an online questionnaire administered in the Crunchbase database (n = 97) and in-depth interviews among startup founders and experts of the startup ecosystem (n = 22). The research summarizes the V4 countries’ measures to protect entrepreneurship with a particular focus on startups. The research found that a crisis such as a pandemic did not have a uniformly negative impact on startups. The winners of the economic crisis are startups in IT, healthcare (Medtech. health-tech), e-commerce and digital education, while those who fared worst are startups in tourism and hospitality. The positive impact of the crisis has been a cleansing of the startup ecosystem. Business support measures supported the viable startups and helped them survive.

Keywords:

startup; innovative enterprises; resilience; economic impacts; Hungary; Visegrad countries 1. Introduction

Since entrepreneurship is one of the most crucial factors of economic development [1], the latest research on entrepreneurial ecosystems has gained strength; however, it has barely been applied to the Visegrad countries. This research sheds light on the crisis resilience of startup companies in Hungary. It is crucial to stimulate innovative startup activity in Hungary to increase the country’s long term visibility and competitiveness in the Central–Eastern European region [2].

In the 21st century, the sudden changes in the external environment caused by COVID-19 and, more recently, the Russian–Ukrainian war have had an unprecedentedly severe impact on the economy as well as society in general [3]. The crisis has caused significant economic damage worldwide [4]. Since the WHO [5,6] announced the pandemic, increasing public attention has been paid to the dangers of economic and social crises [7]. Cities, counties and countries were placed under total lockdown in a matter of days or weeks. These lockdowns were measures of an unprecedented scale in comparison to those taken during previous pandemics, such as the Spanish flu [8].

Thus, macroeconomic factors influence the development of startups globally [9]. Although all industries feel the consequences of crises, startups, those which are younger than 10 years, feature highly innovative technologies and/or business models and strive for significant employee and/or sales growth [10], are among the most vulnerable among economic actors and are currently still facing a number of unexpected challenges—reduced production and/or demand—from both a corporate and organizational perspective [11]. They strongly feel the negative consequences of the recent events and were exposed to strong external and unexpected pressures for which they were not prepared [12,13]. These enterprises must also currently face the negative consequences on national economies, caused by what seems to be the worst geopolitical crisis in recent history [14].

Thus, resilience research is highly desirable as it addresses the urgency to investigate vulnerable situations in which enterprises act [15,16,17] and as Aldianto et al. [4] stated, the concept of business resilience studies in startups is still limited. Saad [17] calls for more research related to this topic utilizing survey-based methods, to provide more generalizable empirical evidence and to help to create more clarity on blurred issues.

Therefore, recent studies have explored the crisis and shock resilience of Hungarian startups, as well as the impact of the crisis caused by the coronavirus that was raging at the time of the research on startups. Hence, studying Hungarian startups in the Visegrad countries (V4) is relevant for these reasons:

- Startups are very fragile and hard to find. This is particularly true in a post-socialist Central and Eastern European country such as Hungary, characterized by a young startup ecosystem, where, unlike in the Western European and Anglo-Saxon ecosystems, long-term time series are not available for studying startup businesses [18].

- The research area is the V4, as these countries are, because of their historical past, the main reference group for comparative studies [19,20,21,22,23,24,25]. The strengths of the Visegrad countries included the potential of startups, in addition to internationalization and product innovation [2].

- Considering the high failure rate among startups [26] and the atmosphere of the Hungarian startup ecosystem, as well as the economic crisis in recent years, many entrepreneurs starting their business face failure or serious crisis. Thus, investigating the dimensions of entrepreneurs’ resilience and its nature among Hungarian startups is vital.

- Despite the fact that Hungary (4.5), according to Hungary National Entrepreneurship Context Index (NECI)—characterizing the entrepreneurial ecosystem—ranks in the lower-middle segment of the business ecosystems in Europe (the Central and Eastern European region has an average score of 4.2), with Hungary’s entrepreneurial ecosystem scoring the highest within the region [27], the Hungarian startup ecosystem has registered a decline in rank (Budapest, the capital of Hungary, decreased by double digits) based on the Startupblink report [28].

- This study presents the state of startups and the contemporary Hungarian startup ecosystem. It aims to explore the changes in innovative startups as a result of the crisis and to provide direction for the post-crisis economic recovery, which supports innovative startup needs to contribute to the development of the regional economy again with their positive results.

The focus of this research is on the crisis resilience of Hungarian startups, mainly to explore the most typical parameters and characteristics of Hungarian startups and their surrounding ecosystem. The paper aims to investigate the critical events faced by startups’ founders in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequently, the Russian–Ukrainian war, and how they reacted to protect their startups. Based on this, the following research questions were formulated:

RQ1: What are the characteristics of Hungarian startups after the crisis?

RQ2: How has the coronavirus crisis affected Hungarian startups?

The research aims to prove the following hypothesis:

H1:

Resilience to crisis and shocks varies in Hungary and the V4 countries.

The first part of the paper summarizes the different interpretations of business resilience with a specific focus on startups. It then presents the study area, the Hungarian startup ecosystem based on the Startupblink international ranking [28] and the business protection measures in the investigated area. The second part examines the crisis resilience of startups through an online survey of startup entrepreneurs in the Visegrad countries and in-depth interviews with experts (N = 22). The study concludes by identifying future research directions based on the findings of the research. The main finding of the paper is that the crisis resilience of startups shows fundamental sectoral differences. The crisis has brought about a cleansing among startups.

The paper is structured as follows: the second part of the study is a literature review. Section 3 presents the study area and the research methodology, and Section 4 presents the results of the survey, the in-depth interviews. Section 5 provides the discussion and presents the conclusion, with several research suggestions.

2. Literature Review

This section presents the main theoretical components regarding the impact of business resilience with a focus on startup enterprises, then the startups surrounding the startup ecosystem (the Hungarian ecosystem) and, last but not least, business protection measures in the V4 countries.

2.1. Resilience with a Focus on Startup Companies

In the 21st century, the biggest challenge of the information age is how we are able to domesticate the ‘unstable chaos’ into ‘fertile anarchy’; the ability that makes this possible is called ‘resilience’ [29]. The concept of resilience was spread in psychology in the 1950s, and in the past decades, it has taken many different forms. Resilience means the ability to be resilient, the ability to cope with challenges [29]. Resilience in general is demonstrated after an event or crisis occurs [30], while business resilience enables organizations to quickly adapt to disruptions while maintaining sustainable business operations and protecting people, assets, and overall brand equity [31]. It also means the capacity for companies to survive, adapt and grow in the face of turbulent change [32]. A variety of research studies use and define the concept of resilience; however, the definition used varies depending on the focus of each article [17,33]. Several articles examine business resilience; however, just a few papers focus on startup resilience.

We conducted a systematic literature review based on the following key words: startup, resilience, crisis, COVID and pandemic in the database Web of Science and Google Scholar. Table 1 summarizes the major challenges, the examined sectors/industries, the measures and the examined geographical areas of the recent topic.

Table 1.

The implications of the crisis for startups.

The literature review highlighted the major challenges of the startups in sectors and industries, as well as the suggested measures to encourage recovery. The issues faced by startups are digitalization, finance, management, networking, risk, sustainability factors and diverse resilience factors. At the same time, the measures to increase the recovery are suggestions and recommendations for financial support, management, strategy, new business models, networking, communication and counselling, which could lead to strengthening the resilience of startups to achieve recovery in the post-crisis period.

It is irrefutable that new companies using digital technologies, i.e., competitors from outside the industry, are emerging in traditional industries, and these startups are creating serious competition, and sometimes even displacing the former leaders of traditional industries by upturning the parameters and characteristics of competition [49]. To sum up, startups can be described as a subgroup of SMEs—young, innovative companies addressing global markets based on technological, process or business model innovation [43,48,50,51]. They differ from large companies in terms of their organizational structure, leadership style, reactions to the environment, available resources and the internal context in which they operate [52,53] especially due to the fact that startup companies lack expertise, resources, funding, and technology [54].

In today’s knowledge-based economy, innovation is seen as the driving force of the economy. The high risk inherent to innovation means that inventions are brought to the market by formalized organizations, mainly startups [55]. In the post-crisis period, the re-launch of the economy should take into account that the development of startups and innovation ecosystems is not just one of many opportunities for society, but an obligation [56]. As the presence of a dominant startup ecosystem can enhance economic diversification [41], it can facilitate the emergence of a more sustainable stock of foreign capital (foreign direct investment) even if startup investment cannot be a serious competitor to a manufacturing project in any category. The importance of startups lies in knowledge sharing and talent attraction. Startups create new opportunities that traditional industries which have collapsed in the crisis are currently unable to provide. Startups can also ensure the presence of the large companies of the future [57]. As the FDI-Center aptly put it: “if you cannot convince Google to locate in your country convince the Google of the future to open its first international office in your country [58]”. “If these companies expand, the investment location will benefit more and more from their presence ([58], p.9)”. In order to achieve these ambitions, i.e., catalyzing knowledge-based economic development and innovation ecosystems, building higher education institutions as knowledge hubs will take on a new, prominent role in the coming years [59]. To sum up the scientific literature, the issue of “startup resilience” is a timely and topical one.

2.2. The Hungarian Startup Ecosystem in the International Rankings in 2021

To answer the RQ1, as first we have to define the startup ecosystem, which is a distinct and defined region where entrepreneurs and support organizations collaborate to create new startups and to help existing startups grow. The term ‘ecosystem’ is most often used to describe the network of ‘people’, ‘organizations’ and ‘resources’ that are used to create startups in the works under review. “By ‘people’, they mean entrepreneurs and investors; by ‘organizations’, they mean investing institutions, large corporations (including, of course, multinationals) and universities; by ‘resources’, they mean the supporting infrastructure provided by people and organizations to help startups to emerge [60]. Although there are several different interpretations of the concept of the entrepreneurial ecosystem in the literature [59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68], certain elements are present in all of them, such as an entrepreneurial focus (existing and potential entrepreneurs in the ecosystem), the multidimensionality of ecosystem elements (social, political, economic and cultural actors and organizations), the movement, interconnectedness and networking of actors, elements and processes that support the emergence of innovative or growth-oriented firms in a given location [69]. Overall, therefore, the emergence of entrepreneurial ecosystems is a major factor in the realization of productive entrepreneurship [70].

In 2013, the StartupBlink global ecosystem map was created, which provides an overview of the actors in each startup ecosystem. In 2017, the first Global Startup Ecosystem Index was published, which has been updated annually ever since. It is now the largest and most comprehensive ecosystem map in the world, based on an algorithm that analyses tens of thousands of data points. The ranking is based on three main criteria: quantity (how many startups there are), quality (how much influence these startups have) and business environment (how easy it is to do business in a given location based on technology infrastructure, red tape, bureaucracy, etc.). Data providers include local data providers such as accelerators, coworking offices and more than 50,000 registered members, as well as global partners such as the Crunchbase and SimilarWeb databases. In 2021, the ranking looks at the startup ecosystem of 1000 cities in 100 countries by area, sector and level of development. The StartupBlink research center has a long-term goal to support the development of each ecosystem [28].

In the Startupblink (2017–2021) reports, the North American continent accounted for the largest share of cities up to 2020 (41.2% in 2020). This trend changed in 2021—in the overall ranking, ecosystems in the North American continent were eclipsed, dropping to 29.7% in total—with the European continent accounting for 38.6% of cities. However, the North American presence in the top 100 stays stagnant, with 40 cities remaining. The presence of European cities, on the other hand, has continued to grow: in 2020, only 339 European cities (33.9%) represented their ecosystem; however, in 2021, this number had grown to 386 (38.6%). The momentum for European ecosystems is not entirely positive, perhaps due to the coronavirus epidemic. Overall, Europe’s presence in the top 1000 ranking has improved; however, only 11 of 44 ranked European countries have improved their ranking, and 25 declined in 2021 compared to the previous year.

In the Central and Eastern European region, Hungary is in a favorable position to grow its ecosystem due to its geographical location; however, to have a more competitive ecosystem it needs more successful scalable startups such as Prezi, which achieved international success in 2008 and has since had no followers, unlike Romania and Croatia, which have since launched internationally successful unicorn startups [28]. Companies with a capitalization of more than USD 1 billion are referred to as unicorns [36], with Megyeri [71] arguing that the presence of unicorns has a positive impact on the startup ecosystem. They attract more potential entrepreneurs and investors. In addition, as Goreczky [72] argued in his study, an increasing number ecosystems can produce unicorn companies. While in 2013 only four ecosystems worldwide could claim this, today more than 80 startup hubs can boast such success stories. This seems to support the view of a well-known expert in the US startup world that “startup communities can be built in any city, and the long-term economic development of cities, regions, countries, and societies depends on building and sustaining such communities ([72], p.4)”.

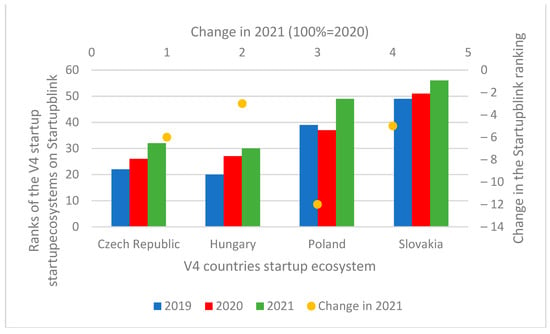

Looking at the ecosystems in the Visegrad countries, the Polish ecosystem remains the leader (ranking 30th among the hundred countries examined by the Startupblink report), followed by the Czech (36th), then the Hungarian (49th) and the Slovak (56th) [28] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Ranking of startup ecosystems in the Visegrad countries according to StartupBlink [28]. Source: Own editing based on StartupBlink [28].

Table 2 details the ranking of the V4 countries’ cities on the global list.

Table 2.

V4 countries’ rankings on StartupBlink.

Despite the pandemic and the economic crisis caused by COVID-19, the Hungarian ecosystem has continued to grow, with the number of cities that represent the Hungarian ecosystem rising to five in 2021. After Budapest, Debrecen and Szeged, two more cities, Pécs and Székesfehérvár, now represent Hungary in the ranking of the world’s top 1000 cities with startup ecosystems. Budapest has been in the top 50 of the world ranking for education for several years, 38th in 2021. According to the report, education could be a breakout point for Hungary [28]. As Endrődi and Kovács-Nagy [73] argue, promoting the accumulation of knowledge in high-tech processes and supporting entrepreneurship is essential to achieve this, and it is worth starting in primary school [74].

2.3. Business Protection Measures in the V4 Countries

The next part of the study summarizes the business protection measures in the V4 countries (Table 3) based on the following documents [75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82]. Three different forms of aid have been used grants: state aid, innovation aid and other business protection aid; public loans and loan guarantees; and tax and contribution subsidies. Within these categories, different countries provided different types of aid in different areas, such as rent subsidies for SMEs in the Czech Republic and Slovakia.

Table 3.

Business protection measures in the Visegrad countries by 2020.

To support startups, for the first time, the European Commission published on 11 March 2020 a call for an immediate EUR 164 million in funding from the European Innovation Council fund [69]. This immediate funding was open to startups and innovative SMEs working on technologies and innovations that could help combat, treat and test the coronavirus outbreak [83]. According to the call for proposals, the European Commission is looking to startups, among others, to provide solutions to the current healthcare crisis. Then, all governments in the V4 countries launched similar calls to support innovation. Just 3 weeks after the EU call, the Czech Republic became the first V4 country to launch the Czech Rise Up Program I on 2 April 2020, followed by two other programs [79]. In Slovakia, the Crisis Slovakia Program was launched on 3 April 2020 [80]. On 24 April 2020, the Hungarian government launched the COVIDEA oil and startup competition [81]. In Poland, on 4 May 2020, the Polish government announced a PLN 200 million startup funding and the launch of the Startup Poland Program [82].

3. Materials and Methods

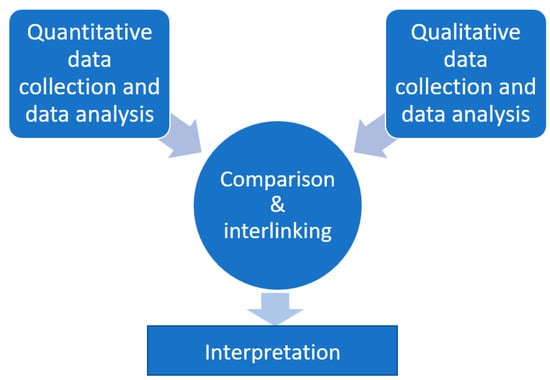

In line with the exploratory nature of the research, a mixed methodology was used, including what [84] is called a ‘convergent parallel design’, which consists of the researcher conducting quantitative and qualitative data collection and data analysis simultaneously and independently of each other, and only linking the two methodological strands when interpreting the results [85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92]. The two parts of the research carried out using the two methods are independent of each other (Figure 2); neither serves as an input to the other, so that quantitative and qualitative data collection and analysis can be carried out simultaneously, without having to wait for the other to be developed [86].

Figure 2.

The design of convergent parallel design. Source: own compilation based on Cresweell and Plano Clark ([85], p. 69).

The purpose of the coherent parallel design is to better understand a given social phenomenon by using both approaches. As the two methods complement each other well, their strengths add up and compensate for each other’s weaknesses; together, they can provide a more complex picture of the subject under study. In addition, the results from quantitative and qualitative methods can be used to complement, illustrate and support each other, and can also be used for comparison [84,85,86].

The study first uses the methodology of qualitative research in form of an online survey (n = 97) and then the quantitative phase in form of semi-structured in-depth interviews (n = 22).

3.1. The Research Area

The study examines Hungarian startups in comparison to the other Visegrad countries, which are also called the Visegrad Four or the Visegrad Group and have existed since 1991. The group serves as a forum for dialogue and close cooperation between three (later four, with the split of Czechoslovakia) Central European countries: the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia [88].

3.2. The Online Survey

The questionnaire survey was conducted online between June and November 2021 among startup entrepreneurs from the Visegrad countries. The questionnaire is part of the V4 Startup Survey 2021 (Section F, G) and aims to assess the crisis resilience of startups. The set of questions used in the questionnaire are validated questions based on the Design Terminal [29] study (Appendix A). Respondents rated the questions on a Likert scale of 1 to 5, where 1 = not at all affected; 5 = very affected). The questionnaire’s sample is based on the Crunchbase database, which has been cited by Block-Sanders [89], Waldner et al. [90], Kemeny et al. [91], Breschi et al. [92] and Banerji-Reimer [93] as a reliable and comprehensive source of information on startup entrepreneurship. Crunchbase is the online startup database of the American startup news portal Tech Crunch; a database that brings together startups from around the world to help them operate. The database was founded in Silicon Valley in 2007 and has grown over the years into a virtual marketplace where investors and interested parties can search for startups. Thus, keeping the database up-to-date is the responsibility and interest of the registered startup companies. The database is modeled on online platforms [94]. As the study adopted the concept of Kollmann and colleagues [10] based on international scientific literature, the Crunchbase database was filtered for startups founded after 2011 with registered offices in the Czech Republic, Poland, Hungary and Slovakia. Thus, the initial sample for the study was startups less than 10 years old, which resulted in a total of 14,610 enterprises.

All companies were contacted directly via email through the Lime survey website [95]. However, as the email availability of many companies was not working, the final sample consisted of a total of 3353 startups. The questionnaire was sent to the startups six times between 9 May and 15 December 2021. It contained, besides the basic demographic questions, nine questions related to the topic: five closed and four open questions. The information was measured on a 5-point Likert scale where a score of 1 indicated not at all important and a score of 5 indicated a very important responsibility.

One hundred and fifty-two respondents participated in the survey but fifty-five contained only partial completions and were therefore disregarded. In total, this resulted in a final questionnaire sample of 97 completions for startups under 10 years old with a ratio of 2.89%. The completion rates were 2.27–3.53% of the final per country. Of the ninety-seven respondents 20 represented Czech (3.53%, 47 Hungarian (3.07%), 24 Polish (2.27%) and 6 Slovak enterprises (3.12%) (Table 4).

Table 4.

The sample of the V5 startup survey 2021.

The questionnaire data were processed using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, (2016), Redmond, Washington, DC, USA: Microsoft) and IBM SPSS (IBM Corp., 2016, IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Armonk, NY, USA: IBM Corp.). Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the characteristics of the respondents, to compare startups in Hungary and other V4 countries. Chi-square, Fisher’s exact tests and Mann–Whitney tests were applied. The Mann–Whitney U test (also known as the Wilcoxon rank sum test) tests for differences between two groups on a single, ordinal variable with no specific distribution. In contrast, the independent samples t-test, which is also a test of two groups, requires the single variable to be measured at the interval or ratio level, rather than the ordinal level, and to be normally distributed [96,97]. The characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Characteristics of respondents and their startups in Hungary and other Visegrad countries (Czech Republic, Poland and Slovakia).

Based on the work of Kézai and Rechnitzer [98], respondents were grouped according to their main activity according to the Hungarian Unified Sectoral Classification System (TEÁOR’08) into four groups of activities that are important for urban development. Of the respondents, 49.03% were engaged in science, research and development, 37.3% in market services, 9.3% in media and publishing and 4% in arts (design, creative economy or other artistic activities).

3.3. The Semi-Structured Interviews

The qualitative data collection involved ten semi-structured interviews based on the work of Babbie [99]. The selection of participants was not based on mathematical-statistical representativeness but rather on the richness of potential data and therefore subjects were selected using a snowball method. The selection of suitable interviewees was aided by presentations at local startup events in 2022. In-depth interviews with experts were recorded on a Google Meet platform. Table 6 summarizes the interviewees and their main characteristics.

Table 6.

Respondents of the semi-structured interviews.

In accordance with a constructivist approach to interviewing, active interviewing was chosen [100]. The interview subjects and the interviewer create meaning as equal partners, participating together in the creation of knowledge in a so-called travelling interview [100]. The interviewee has the opportunity to ask back and the interviewer, avoiding focusing on their own interpretation, has the opportunity to reinterpret on-the-spot answers that may not be clear [101].

The interview thread was structured around ten questions, which can be found in Appendix B. A transcript of the 45–60 min online interviews was produced and the ad hoc analysis method from Brinkmann and Kvale [101] was used to analyze the transcript. Instead of a specific procedure, we developed our own analysis method that fits the research topic. We interpreted the information given during the interview in the context of what was already known and what became known during the analysis, i.e., the actors’ perspectives met the interpretations of other interviewees and also those of the analyst [101].

We applied an intra coding approach to the analysis, carried out a one-by-one analysis and summary interpretation of the interviews, and then organized the interviews according to eleven non-exclusive categories. The initial categories were derived from the interview questions, and some categories even emerged from the interviews. Finally, the directions were combined to search for and summarize the meanings [102].

4. Results

4.1. The Result of the Online Survey

When asked how their business was affected by the pandemic, Hungarian businesses and those in the other V4 countries—the Czech Republic, Poland and Slovakia—were equally moderately affected by the COVID pandemic and related measures (Fisher = 1.65; p = 0.82).

The survey found that Czech, Polish and Slovak startups had more difficulties in growing (Fisher = 11.64; p = 0.02) and internationalizing (Fisher = 9.12; p = 0.06), while there were no differences in the other factors. There was a strong trend, but Hungarians had more trouble with sales (Fisher = 8.4; p = 0.06). Team development (Fisher = 3.65; p = 0.47), cash flow (Fisher = 6.68; p = 0.15), and profitability (maintaining stable income) (Fisher = 2.82; p = 0.6), were equally challenging in all V4 countries (Fisher = 4.48; p = 0.36). Internal processes within the company were equally challenging, as were financing (Fisher = 2.81; p = 0.6) and product or service development (Fisher = 4.4; p = 0.36). Attracting competent staff is quite polarized (Fisher = 2.4; p = 0.69). Furthermore, there was no difference in the financial barriers (Fisher = 5.95; p = 0.2) to startups with a presence in the V4 countries, such as too little capital, and difficulties in raising capital, which were significant obstacles to their development. Regulations (Fisher = 0.82; p = 0.96), bureaucracy and red tape (Fisher = 1.68; p = 0.83), and lack of access to knowledge (Fisher = 4.03; p = 0.42) or networking (Fisher = 2.84; p = 0.61) and management skills (Fisher = 3.24; p = 0.56) were not a barrier in any country. Attracting (Fisher = 2.67; p = 0.64) and retaining (Fisher = 1.92; p = 0.83) skilled human capital is a consequence of the crisis and, to a lesser extent, a barrier, as the willingness of workers to change jobs has declined [103].

V4 countries were, on average, satisfied with their growth rates (Fisher = 1.94; p = 0.78) thanks to a number of business support measures. They consider that they were moderately affected by the pandemic and related measures. Similar to the results of Juhász and Szabó [104], in addition to the negative effects of the crisis, a number of positive aspects were also uniformly mentioned, such as the time factor (more time to design the product (Z = −0.69; p = 0.49), more time and opportunity to develop new ideas, features, etc. (Z = −0.62; p = 0.53), increased time to design (Z = −0.46; p = 0.65), opportunity to fine tune the schedule (Z = −0.75; p = 0.45). The transformation of the market has also been accompanied by its expansion, which has in turn created new openings (increased market (Z = −0.35; p = 0.73), new opportunities (Z = −0.22; p = 0.82)). Opportunities to seek corporate partnerships (mentoring, assistance) have opened up, encouraging startups to work on further development (encouraged them to seek mentoring, assistance and corporate partnerships (Z = −0.61; p = 0.54), encouraged them to seek potential development opportunities (Z = −1.52; p = 0.13)).

Startup entrepreneurs in the study area also agree on the obstacles created by the crisis caused by the epidemic. In addition to the financial crisis (Z = −0.02; p = 0.99), what stood out was the lack of travel opportunities (Z = −1.39; p = 0.17), the difficulties of teleworking (Z = −0.24; p = 0.81), which in the long term created a significant emotional burden (Z = −1.3; p = 0.19), in addition to the need to constantly re-plan and often to lay off employees (Z = −0.38; p = 0.71), and other circumstances (Z = −1.58; p = 0.11) due to the constant uncertainty.

In terms of firms’ plans to raise capital, foreign start-ups are more likely to consider raising domestic venture capital (Fisher = 5.04; p = 0.03), while there is no difference in the extent to which most firms want to raise some capital (Khi-square = 0.36; p = 0.55), nor in the extent to which they know what capital they would raise (p = 0.49). There was no difference in that almost no one would consider involving a domestic accelerator (p = 1), bank (p = 1), stock exchange (p = 0.24), university incubator (p = 0.49), local government office/municipality/local government (p = 0.24), family and friends (p = 0.24). There were no differences for Hungarian startups compared to other countries, but slightly more people than above counted in the involvement of a foreign accelerator (p = 0.78), local business angel (p = 0.37), foreign business angel (p = 1), community funding (p = 1), strategic industry investor (p = 0.39), European Commission, e.g., Horizon 2020 (p = 0.58) and foreign venture capital (p = 0.79) (Appendix C). Table 7 shows the descriptive statistics of the responses to the survey questions on a Likert scale from 1 to 5 (standard deviation and mean values in Hungarian and further V4 breakdown).

Table 7.

Descriptive statistics of the answers to the questions on the coronavirus epidemic in Hungarian and in the other V4 countries (Czech Republic, Poland and Slovakia) (on a Likert scale of 1–5).

4.2. The Result of the Interviews

The crisis, just such as the outbreak of the coronavirus, caused growing uncertainty for societies, economies and businesses worldwide. To obtain a detailed insight into the crisis resilience of startups, we conducted online interviews. The important impacts highlighted by the interviewees are summarized in Table 8.

Table 8.

The impact of the crisis on startups based on the results of the interviews.

Overall, the interviews confirmed the results of previous research [4,9,12,17,27,42,43,44,45,46,47,76,105,106,107]. The crisis resilience of startups does not show a consistent picture. Several negative effects such as insecurity, mental pressure, a lack of personal presence, and a higher burden on women are typical. The gender gap may be because women are more likely to start businesses in industries more affected by the crisis, such as hospitality, leisure and retail. Another reason is the “invisible job”, which is seen as a result of the duality of working from home and women’s responsibilities as workers, which was particularly prevalent during lockdown in the pandemic.

The crisis has had several positive effects in addition to its many negative ones, such as the emergence of new opportunities—think of the emergence of online education; flexibility—the need to adapt to a changing environment, and creativity—the need for businesses to offer new, creative solutions to constant change. Additionally, the time factor, which results in more time to fine-tune the product/service. At the same time, the crisis has brought a cleansing among startups, with several business support grants helping viable ones.

Overall, therefore, the hypothesis conjectured that startups in the Visegrad countries were affected by the coronavirus measures in significantly different ways was not fulfilled. Hungarian and Czech, Polish and Slovak startups rated the impact of the coronavirus very similarly, despite the different measures. This is in line with Sass et al. [98], i.e., the economic crisis caused by the pandemic affected the Hungarian economy and Hungarian firms in a similar way in the whole Central and Eastern European region, especially in the Visegrad countries [108].

5. Discussion and Conclusions

The study aimed to present the situation of startups in Hungary and other Visegrad countries. First, it summarizes the concepts of startup resilience and the startup ecosystem, then it uses the international Startupblink ranking [28] to position the Hungarian startup ecosystem and sums up the business protection measures in the V4 countries. Then, it presents the results of the questionnaire survey of startups in the Visegrad countries (N = 97) and the in-depth interviews with Hungarian startup entrepreneurs (N = 22).

The research aimed to put the Hungarian startup ecosystem in the context of international competition. The Hungarian ecosystem is ranked third among the Visegrad countries in 2021 according to the StartupBlink [28] report. At the same time, despite the crisis, Hungary’s position in the international competition has been further strengthened, with five Hungarian cities—Budapest, Debrecen, Pécs, Szeged and Székesfehérvár—now ranked among the top 1000 cities in the world for startup ecosystems. Additionally, the capital has been in the top 50 of the world ranking in education for years.

Similar to the results [4,40,41,43,46,48,104,106,107], the research showed that the crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic, did not have a uniformly negative impact on startups. The winners of the economic crisis caused by the pandemic are companies active in the IT sector, healthcare (Medtech and health tech), e-commerce and digital education. The big losers are startups in hospitality and tourism. In her study, Karsai [109] also assessed that “the persistence of significant state dominance, which catalyzed the emergence of the startup sector after the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic and helped to counter its effects, may not only help but also hinder the development of the startup sector in the region, as the natural selection mechanism of the market is not able to operate purely”. However, in the present research the respondents considered the positive effect of the epidemic as a cleansing and natural selection of startups. The viable startups survived. To overcome their funding obstacles, startup support programs have been launched in the Visegrad countries, following the EU model, such as the Czech Rise up Program in the Czech Republic, the Hack the Crisis Slovakia competition in Slovakia, the Startup Poland Program in Poland and the COVIDEA Ideas and Startup Competition in Hungary. In addition, different business protection measures have been put in place in different countries. Such measures include non-repayable grants such as state, innovation and other business protection grants, as well as state loans and loan guarantees, and tax and contribution subsidies.

Implications, Limitations and Future Research Avenues

The research is based solely on the most comprehensive dataset of high-tech companies and investors in the US, Crunchbase, an internationally recognized database, according to Pisoni and Onetti [110]. There is no comprehensive, officially available startup data collection in the region under study, i.e., neither in Central–Eastern Europe nor in the V4 countries. The quantitative V4 startup survey was a questionnaire survey conducted by direct email to the companies filtered by the startup definition based on Kollmann et al. [10]. The willingness to respond from the contacted startup enterprises was around 3% completion rate, due to the constantly changing environment, i.e., constant challenges and re-planning, as the interviewees stated.

The study concerns Hungary, which does not represent the entire V4 startup sector. The population of startups surveyed by countries is not large enough to allow statistical analyses to be conducted at an acceptable level of reliability divided by each country, so we concentrate on Hungary and the other V4 countries, which may not be methodologically satisfactory for many scholars. Perhaps this is an exciting area of research for scholars.

Another interesting topic that could be extended as a further line of research to the cities of the Central and Eastern European region is to examine which cities served as startup hubs before and after the pandemic in the region, and where and what measures supported the development of business communities, thus strengthening the entrepreneurial ecosystem approach, or were linked to industrial development, which would support the catching-up of the CEE region with its Western counterparts. Since, as Sass [111] has noted, the V4 countries are significantly below the EU-27 average, and this problem of economic catching-up has long been a crucial issue.

The results of the research can provide a basis for future startup entrepreneurs thinking about innovative solutions to a problem; for practitioners looking to develop their network of contacts; and for local leaders to consider what innovative startups, seen as drivers of the local economy, can be given space to join innovation support programs. After all, as highlighted in the OECD [112] study, innovation is as vital for rural areas as it is for urban economies. Their goals and challenges are the same: increasing productivity and improving the quality of public services [112]. It also provides guidance to policy makers on how to identify and support these businesses, thereby increasing the competitiveness of the area. As a policy recommendation, we call for collaboration between municipalities, public and private partners, startups and investors to jointly develop a city startup ecosystem and associated smart regional hubs adapted to changing circumstances and local conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.K.K.; Supervision, A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Agnieska Skala form the Faculty of Management, Warsaw University of Technology, Warsaw, Poland for providing the V4 startup survey and Miroslav Pavlák from the Faculty of Economics, University of West Bohemia for the selfless support.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

| Annex2: Online survey |

| D7. What sources are you looking to raise in the next 12 months? |

| We’re not going to raise any. |

| Domestic accelerator |

| Foreign accelerator |

| Business angel domestic |

| Business angel foreign |

| Bank (credit) |

| Crowdfunding |

| Stock exchange |

| Academic incubator (at a university) |

| Strategic industry investor |

| European Commission, e.g., Horizon 2020 |

| Municipal office/municipality/local government |

| Domestic VC |

| Foreign VC |

| Family and Friends |

| We do not know yet. |

| Other |

| F12. What were the main challenges of your startup in the last 12 months? Please, rate the options (1 = less challenging; 5 = very much challenging) 1 2 3 4 5 |

| Sales/client acquisition 1 2 3 4 5 |

| Funding 1 2 3 4 5 |

| Product or service development 1 2 3 4 5 |

| Growth 1 2 3 4 5 |

| Internal processes within the company 1 2 3 4 5 |

| Internationalization 1 2 3 4 5 |

| Acquiring competent employees 1 2 3 4 5 |

| Team development 1 2 3 4 5 |

| Cash flow/liquidity 1 2 3 4 5 |

| Profitability (maintaining stable income) 1 2 3 4 5 |

| F13. If other, please specify |

| F14. What are the strongest barriers to growth in your business? Please evaluate all the barriers, where 1 = no barrier at all, and 5 = serious barrier 1 2 3 4 5 |

| Regulations 1 2 3 4 5 |

| Offices and bureaucracy 1 2 3 4 5 |

| Attracting qualified staff 1 2 3 4 5 |

| Retaining qualified staff 1 2 3 4 5 |

| Financial barriers (too little capital, difficulties in obtaining it) 1 2 3 4 5 |

| Lack of access to knowledge 1 2 3 4 5 |

| Lack of networking 1 2 3 4 5 |

| Lack of management knowledge 1 2 3 4 5 |

| G1. How did the COVID-19 pandemic influence your startup? Please rate 1 = not affected at all; 5 = very much affected |

| 1 2 3 4 5 |

| G2. What were the positive impacts of COVID-19 on your startup? Please rate these impacts 1 = less important; 5 very much important! |

| More time to plan the product 1 2 3 4 5 |

| More time and opportunities on pivoting new ideas, features, etc. 1 2 3 4 5 |

| Time to concentrate on design 1 2 3 4 5 |

| Possibility to finetune the roadmap 1 2 3 4 5 |

| Our market was growing 1 2 3 4 5 |

| Opened up new opportunities 1 2 3 4 5 |

| Encouraged us to seek mentoring, assistance and corporate partnerships 1 2 3 4 5 |

| Encouraged us to look for potential development opportunities 1 2 3 4 5 |

| G3. If other positive impacts, please specify. |

| G4. What barriers did you experience during the COVID-19 pandemic, that negatively influenced your startup? Please rate these factors (1 = not influenced at all, 5 = very much influenced) |

| Financial crisis 1 2 3 4 5 |

| Lack of financial support 1 2 3 4 5 |

| No travel possibilities 1 2 3 4 5 |

| Difficulties of remote-working 1 2 3 4 5 |

| Emotional breakdown 1 2 3 4 5 |

| Employee Layoff 1 2 3 4 5 |

| Other 1 2 3 4 5 |

| G5. If other barriers, please specify. |

| G6. Are you satisfied with the growth of your business in the past year? Please rate 1 = Not satisfied at all; 5 = Very much satisfied |

| 1 2 3 4 5 |

| G7. How would you rate the likelihood of the following scenarios for your company? In each row mark only one answer |

| It will be sold 1 2 3 4 5 |

| I will stay there as a founder on a permanent basis 1 2 3 4 5 |

| It will be present on international markets 1 2 3 4 5 |

| It will be a key player in its industry 1 2 3 4 5 |

| It will become an IPO and go public 1 2 3 4 5 |

| It will become a unicorn 1 2 3 4 5 |

| G8. If other, please specify |

| G9. What would be your message for future startups? |

Appendix B

Annex 1: Semi-structured in-depth interview questions

- How would you describe the impact of the crisis (such as COVID-19 pandemic and Russian–Ukrainian war) on your startup business?

- Have there been any positive impacts from the crisis you have experienced in the past year?

- If yes, what positive impacts, please elaborate

- What difficulties have you experienced during the crisis in the last year?

- Are you satisfied with the growth of your business over the past year? Please rate on the following scale: 1 (not satisfied)–2–5 (very satisfied) Please give reasons for your answer

- What are the main challenges you are currently facing in your start-up business?

- How do you intend to overcome these challenges?

- What resources do you plan to bring into your business in the next year?

- What do you think the impact of the crisis has been on startups in general, both domestically and internationally?

- Is there any sector that has been a winner from the crisis (pandemic and Russian–Ukrainian war)?

- If so, which sector?

- Do you see a difference in how female or male startup entrepreneurs were affected by the crisis (in terms of female roles?)

- Do you see willingness to start a startup business increasing or decreasing? In general, or among women?

- What is the message for future startup entrepreneurs?

Appendix C

| Survey Question | Answer | Startups in the V4 | |||||

| Hungarian Startups | Czech, Polish and Slovakian Startups | ||||||

| N | Mean | Std. Deviation | N | Mean | Std. Deviation | ||

| What sources are you looking to raise in the next 12 months? | We’re not going to raise any. | 35 | 0.23 | 0.426 | 35 | 0.17 | 0.382 |

| Domestic accelerator | 35 | 0.09 | 0.284 | 35 | 0.11 | 0.323 | |

| Foreign accelerator | 35 | 0.20 | 0.406 | 35 | 0.26 | 0.443 | |

| Business angel domestic | 35 | 0.14 | 0.355 | 35 | 0.26 | 0.443 | |

| Business angel foreign | 35 | 0.20 | 0.406 | 35 | 0.17 | 0.382 | |

| Bank (credit) | 35 | 0.06 | 0.236 | 35 | 0.03 | 0.169 | |

| Crowdfunding | 35 | 0.14 | 0.355 | 35 | 0.11 | 0.323 | |

| Stock exchange | 35 | 0.00 | 0.000 | 35 | 0.09 | 0.284 | |

| Academic incubator (at a university) | 35 | 0.06 | 0.236 | 35 | 0.00 | 0.000 | |

| Strategic industry investor | 35 | 0.17 | 0.382 | 35 | 0.29 | 0.458 | |

| European Commission, e.g., Horizon 2020 | 35 | 0.200 | 0.4058 | 35 | 0.286 | 0.4583 | |

| Municipal office/municipality/local government | 35 | 0.09 | 0.284 | 35 | 0.00 | 0.000 | |

| Foreign VC | 35 | 0.31 | 0.471 | 35 | 0.26 | 0.443 | |

| Domestic VC | 35 | 0.23 | 0.426 | 35 | 0.49 | 0.507 | |

| Family and Friends | 35 | 0.00 | 0.000 | 35 | 0.09 | 0.284 | |

| We do not know yet. | 35 | 0.00 | 0.000 | 35 | 0.06 | 0.236 | |

| Other | 0 | 0 | |||||

| What were the main challenges of your startup in the last 12 months? Please, rate the options (1 = less challenging; 5 = very much challenging) 1 2 3 4 5 | Sales/client acquisition | 28 | 3.29 | 1.536 | 33 | 4.27 | 1.153 |

| Funding | 28 | 3.36 | 1.545 | 33 | 3.79 | 1.386 | |

| Product or service development | 28 | 3.29 | 1.436 | 33 | 3.82 | 1.334 | |

| Growth | 28 | 3.21 | 1.524 | 33 | 4.15 | 1.034 | |

| Internal processes within the company | 28 | 2.61 | 1.257 | 33 | 3.06 | 1.273 | |

| Internationalization | 28 | 2.14 | 1.325 | 33 | 3.27 | 1.442 | |

| Acquiring competent employees | 28 | 3.32 | 1.517 | 33 | 3.52 | 1.523 | |

| Team development | 28 | 3.36 | 1.224 | 33 | 3.55 | 1.348 | |

| Cash flow/liquidity | 28 | 3.25 | 1.351 | 33 | 3.97 | 1.357 | |

| Profitability (maintaining stable income) | 28 | 3.43 | 1.372 | 33 | 3.85 | 1.372 | |

| What are the strongest barriers of the growth of your business? Please evaluate all the barriers, where 1 = no barrier at all, and 5 = serious barrier 1 2 3 4 5 | Regulations | 28 | 2.36 | 1.496 | 33 | 2.45 | 1.416 |

| Offices and bureaucracy | 28 | 2.39 | 1.397 | 33 | 2.45 | 1.416 | |

| Attracting qualified staff | 28 | 2.86 | 1.325 | 33 | 2.88 | 1.244 | |

| Retaining qualified staff | 28 | 2.25 | 1.041 | 33 | 2.52 | 1.253 | |

| Financial barriers (too little capital, difficulties in obtaining it) | 28 | 3.36 | 1.339 | 33 | 3.70 | 1.132 | |

| Lack of access to knowledge | 28 | 1.61 | 0.916 | 33 | 2.12 | 1.293 | |

| Lack of networking! | 28 | 2.29 | 1.301 | 33 | 2.79 | 1.364 | |

| Lack of management knowledge | 28 | 1.96 | 0.962 | 33 | 2.42 | 1.275 | |

| How did the COVID-19 pandemic influence your startup? | Please rate 1 = not affected at all; 5 = very much affected | 28 | 2.71 | 1.384 | 33 | 3.18 | 1.446 |

| What were the positive impacts of COVID-19 on your startup? Please rate these impacts 1 = less important; 5 very much important | More time to plan the product | 28 | 2.68 | 1.416 | 33 | 2.45 | 1.502 |

| More time and opportunities on pivoting new ideas, features, etc. | 28 | 2.50 | 1.171 | 33 | 2.76 | 1.437 | |

| Time to concentrate on design | 28 | 2.18 | 1.219 | 33 | 2.30 | 1.185 | |

| Possibility to finetune the roadmap | 28 | 2.29 | 1.272 | 33 | 2.55 | 1.325 | |

| Our market was growing | 28 | 2.79 | 1.343 | 33 | 2.70 | 1.591 | |

| Opened up new opportunities | 28 | 2.93 | 1.489 | 33 | 3.00 | 1.479 | |

| Encouraged us to seek mentoring, assistance and corporate partnerships | 28 | 1.96 | 1.170 | 33 | 2.09 | 1.100 | |

| Encouraged us to look for potential development opportunities | 28 | 2.29 | 1.329 | 33 | 2.76 | 1.146 | |

| What barriers did you experience during the COVID-19 pandemic, that negatively influenced your startup? Please rate these factors (1 = not influenced at all, 5 = very much influenced) | Financial crisis | 28 | 2.64 | 1.420 | 33 | 2.67 | 1.614 |

| Lack of financial support | 28 | 2.29 | 1.329 | 33 | 2.85 | 1.623 | |

| No travel possibilities | 28 | 3.11 | 1.685 | 33 | 3.61 | 1.391 | |

| Difficulties of remote-working | 28 | 2.04 | 1.201 | 33 | 2.09 | 1.182 | |

| Emotional breakdown | 28 | 2.36 | 1.420 | 33 | 1.85 | 1.004 | |

| Employee Layoff | 28 | 1.86 | 1.268 | 33 | 1.88 | 1.139 | |

| Other | 28 | 1.25 | 0.844 | 33 | 1.58 | 1.119 | |

| Are you satisfied with the growth of your business in the past year? | Please rate 1 = Not satisfied at all; 5 = Very much satisfied 1 2 3 4 5 | 28 | 2.93 | 1.303 | 33 | 2.88 | 1.193 |

References

- Illés, B.C.; Dunay, A.; Jelonek, D. The entrepreneurship in Poland and in Hungary: Future entrepreneurs education perspective. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2015, 12, 48–58. [Google Scholar]

- Gál, Z.; Lux, G. FDI-based regional development in Central and Eastern Europe: A review and an agenda. Tér És Társadalom 2022, 36, 68–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopaničová, J.; Vokounova, D. Cultural Differences in Coping with Changes in the External Environment—A Case of Behavioural Segmentation of Senior Consumers Based on Their Reaction to the Covid-19 Pandemic. Cent. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2022, 12, 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldianto, L.; Anggadwita, G.; Permatasari, A.; Mirzanti, I.R.; Williamson, I.O. Toward a Business Resilience Framework for Startups. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-sopening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-1282020#:~:text=WHO%20has%20been%20assessing%20this,to%20use%20lightly%20or%20carelessly (accessed on 4 January 2022).

- WHO. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation Report 51. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situationreports/20200311-sitrep51-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=1ba62e57_10percent20access (accessed on 4 January 2022).

- Sady, M. Significance of startups’ dual mission during the times of crisis. In Współczesne Problemy Zarządzania Publicznego i Przedsiębiorczości Społecznej; Ćwiklicki, M., Frączkiewicz-Wronka, A., Pacut, A., Sienkiewicz-Małyjurek, K., Eds.; Małopolska Szkoła Administracji Publicznej Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego w Krakowie: Krakow, Poland, 2020; ISBN 978-83-89410-29-0. Available online: http://koncepcje.uek.krakow.pl/wpcontent/uploads/2021/01/4_Sady_2020.pdf (accessed on 21 May 2022).

- Baker, S.R.; Bloom, N.; Davis, S.J.; Kost, K.; Sammon, M.; Viratyosin, T. The unprecedented stock market reaction to COVID-19. Rev. Asset Pricing Stud. 2020, 10, 742–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridho, W.; Azizah, N. Factor analysis of the phenomenon of mass layoffs at startups: Mixed approach with structural equation modeling. J. MEBIS (Manaj. Bisnis) 2022, 7, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmann, T.; Stöckmann, C.; Hensellek, S.; Kensbock, J. European Startup Monitor 2016. Available online: http://europeanstartupmonitor.com/fileadmin/esm_2016/report/ESM_2016.pdf (accessed on 2 October 2018).

- Davis, J.; Thilagaraj, A. India: Impact of Covid-19 on entrepreneurship and start-up ecosystem. Wesley. J. Res. 2021, 14, 115–120. [Google Scholar]

- Kuckertz, A.; Brandle, L.; Gaudig, A.; Hinderer, S.; Reves, C.A.M.; Prochotta, A.; Berger, E.S. Startups in times of crisis–A rapid response to the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Bus. Ventur. Insights 2020, 13, e00169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Leung, T.Y.; Kingshott, R.P.J.; Davcik, N.S.; Cardinali, S. Managing uncertainty during a global pandemic. An international business perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 116, 188–192. [Google Scholar]

- Foris, T.; Tecău, A.S.; Dragomir, C.-C.; Foris, D. The Start-Up Manager in Times of Crisis: Challenges and Solutions for Increasing the Resilience of Companies and Sustainable Reconstruction. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ates, A.; Bititci, U. Change process: A key enabler for building resilient SMEs. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2011, 49, 5601–5618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantur, D.; Say, A.I. Measuring Organizational Resilience: A Scale Development. J. Bus. Econ. Financ. 2015, 4. Available online: https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/jbef/issue/32406/360419 (accessed on 4 January 2022).

- Saad, M.H.; Hagelaar, G.; van der Velde, G.; Omta, S.W.F.; Foroudi, P. Conceptualization of SMEs’ business resilience: A systematic literature review. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2021, 8, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radácsi, L.; Csákné Filep, J. Survival and growth of Hungarian start-ups. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2021, 8, 262–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egri, Z.; Tánczos, T. The spatial peculiarities of economic and social convergence in Central and Eastern Europe. Reg. Stat. 2018, 8, 49–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotosz, B.; Lengyel, I. Térségek konvergenciájának vizsgálata a V4-országokban. Stat. Rev. 2018, 96, 1069–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuttor, D. (Ed.) Visegrad Mosaic—New Colours and Old Contours: Observing and Understanding the Spatial Features of Socio-Economic Processes in East Central Europe; University of Miskolc Faculty of Economics: Miskolc, Hungary, 2018; Available online: https://gtk.uni-miskolc.hu/files/13015/ivf_v4_book_finalv2_25.pdf (accessed on 4 January 2022).

- Majerová, I. Regional development and its measurement in Visegrad Group countries. Deturope–Cent. Eur. J. Reg. Dev. Tour. 2018, 10, 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szennay, Á. A startupok helyzete a közép-és kelet-európai piacgazdaságokban. Prosperitas 2019, 6, 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zsibók, Z.; Páger, B. Hosszú távú, előretekintő regionális növekedési pályák vizsgálata a visegrádi országokban az útfüggőség kontextusában. In Magyarok a Kárpát-medencében 4; Szónokyné Ancsin, G., Ed.; Közép Európai Monográfiák. Innovariant Kft.: Szeged, Hungary, 2020; Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/11155/2301 (accessed on 4 January 2022).

- Éltető, A.; Sass, M.; Götz, M. The dependent Industry 4.0 development path of the Visegrád countries. Intersect. East Eur. J. Soc. Politics 2022, 8, 147–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefian Arani, V.; Fayyazi, M.; Amin, F.; Davari, A. Identifying the dimensions of personal resilience model of Iranian startup founders. J. Bus. Manag. 2022, 14, 741–769. [Google Scholar]

- Csákné Filep, J.; Gosztonyi, M.; Radácsi, L.; Szennay, Á.; Tímár, G. Entrepreneurial Environment and Attitudes in Hungary. In Global Entrepreneurship Monitor National Report; Budapest Business School: Budapest, Hungary, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Startupblink. 2021. Available online: https://report.startupblink.com (accessed on 5 January 2023).

- Kollár, D.; Kollár, J. The Art of Shipwrecking: The Information Society and the Rise of Exaptive Resilience. Dialogue Univers. 2020, 30, 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wildavsky, A.B. Searching for Safety; Transaction Publishers: New Brunswick, NJ, USA; London, UK, 1998; Volume 10. [Google Scholar]

- Simeone, C.L. Business resilience: Reframing healthcare risk management. J. Healthc. Risk Manag. 2015, 35, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamel, G.; Välikangas, L. The quest for resilience. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2003, 81, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Haase, A.; Eberl, P. The challenges of routinizing for building resilient startups. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2019, 57, 579–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okafor, L.; Khalid, U.; Gama, L.E.M. Do the size of the tourism sector and level of digitalization affect COVID-19 economic policy response? Evidence from developed and developing countries. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemell, K.-K.; Wang, X.; Nguyen-Duc, A.; Grendus, J.; Tuunanen, T.; Abrahamsson, P. Startup metrics that tech entrepreneurs need to know. In Fundamentals of Software Startups; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 111–127. [Google Scholar]

- Kenney, M.; Zysman, J. Unicorns, Chesire cats, and the new dilemmas of entrepreneurial finance. Ventur. Cap. 2019, 21, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaldo, A.; Pittiglio, R.; Reganati, F.; Sarno, D. Access to Bank Financing and Start-Up Resilience: A Survival Analysis Across Business Sectors in a Time of Crisis. Manch. Sch. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croteau, M.; Grant, K.A.; Rojas, C.; Abdelhamid, H. The lost generation of entrepreneurs? The impact of COVID-19 on the availability of risk capital in Canada. J. Entrep. Emerg. Econ. 2021, 13, 606–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilloni, M.; Kádár, J.; Abu Hamed, T. The Impact of COVID-19 on Energy Start-Up Companies: The Use of Global Financial Crisis (GFC) as a Lesson for Future Recovery. Energies 2022, 15, 3530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olszewski, M. Odporność start-upów na kryzys wywołany przez pandemię COVID-19. Przykład Branży Turystycznej. Pr. Kom. Geogr. Przemysłu Pol. Tow. Geogr. 2022, 36, 190–202. [Google Scholar]

- Budden, P.; Murray, F.; Ukuku, O. Differentiating Small Enterprises in the Innovation Economy: Start-Ups, New SMEs & Other Growth Ventures. 2021. Available online: https://innovation.mit.edu/assets/BuddenMurrayUkuku_SME-IDE_WorkingPaper__Jan2021.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2023).

- Paoloni, P.; Modaffari, G.; Paoloni, N.; Ricci, F. The strategic role of intellectual capital components in agri-food firms. Br. Food J. 2022, 124, 1430–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skala, A. Sustainable Transport and Mobility—Oriented Innovative Startups and Business Models. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota, R.d.O.; Bueno, A.; Gonella, J.d.S.L.; Ganga, G.M.D.; Godinho Filho, M.; Latan, H. The effects of the COVID-19 crisis on startups’ performance: The role of resilience. Manag. Decis. 2022, 60, 3388–3415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuckertz, A.; Brandle, L. Creative reconstruction: A structured literature review of the early empirical research on the COVID-19 crisis and entrepreneurship. Manag. Rev. Q. 2022, 72, 281–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kézai, P.K.; Szombathelyi, M.K. Factors effecting female startuppers in Hungary. Econ. Sociol. 2021, 14, 186–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreenivasan, A.; Shah, B.; Suresh, M. Modeling of factors affecting supplier selection on start-ups during frequent pandemic episodes like COVID-19. Benchmarking 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naděžda, P.; Pavlák, M.; Polák, J. Factors impacting startup sustainability in the Czech Republic. Innov. Mark. 2019, 15, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szalavetz, A. Technológiai vállalatok—Vissza az alapokhoz? Körkérdés: A pandémia utáni kibontakozás dilemmáiról. Külgazdaság 2022, 66, 128–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aulet, W.; Murray, F. A Tale of Two Entrepreneurs: Understanding Differences in the Types of Entrepreneurship in the Economy; Martin Trust Center for MIT Entrepreneurship: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skala, A. The startup as a result of innovative entrepreneurship. In Digital Startups in Transition Economies; Palgrave Pivot: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 1–40. ISBN 978-3-030-01500-8. [Google Scholar]

- Man, T.W.; Lau, T.; Chan, K.F. The competitiveness of small and medium enterprises: A conceptualization with focus on entrepreneurial competencies. J. Bus. Ventur. 2002, 17, 123–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebben, J.J.; Johnson, A.C. Efficiency, flexibility, or both? Evidence linking strategy to performance in small firms. Strategy Manag. J. 2005, 26, 1249–1259. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20142308 (accessed on 7 January 2023). [CrossRef]

- Setioningtyas, W.P.; Illés, C.B.; Dunay, A.; Hadi, A.; Wibowo, T.S. Environmental Economics and the SDGs: A Review of Their Relationships and Barriers. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lányi, B. A startup vállalkozók személyiségjellemzőinek hatása az innovatív piaci jelenlétre-különös tekintettel az egészségügyi és orvosi biotechnológiai ágazatra. Közép Európai Közlemények 2017, 10, 77–90. [Google Scholar]

- Nagy, S. Az innovációs startup ökoszisztémák gazdasági és társadalmi hatásai és fejlesztésük egyes aspektusai. Curr. Soc. Econ. Process. 2020, 15, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goreczky, P. Új stratégiák a beruházásösztönzésben: Fókuszban a fenntartható FDI. KKI ELEMZÉSEK 2021, 18, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FDI Center. Why Attracting Startups Is More Important than Ever. Available online: https://fdi-center.com/why-attracting-startups-is-more-important-than-ever/ (accessed on 17 January 2022).

- Vasvári, B.; Mayer, G.; Vasa, L. A tudományos és innovációs parkok szerepe a tudásgazdaság és az innovációs ökoszisztéma fejlesztésében. Tér Gazdaság Ember 2020, 8, 95–107. [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi, N.; Seppanen, P.; Boominathan, G.; Oivo, M.; Liukkunen, K. Insights into startup ecosystems through exploration of multi-vocal literature. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2019, 105, 56–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, J. Predators and Prey: A New Ecology of Competition. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1993, 71, 75–86. [Google Scholar]

- Isenberg, D.J. How to Start an Entrepreneurial Revolution. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2010, 88, 41–50. [Google Scholar]

- Isenberg, J. Introducing the Entrepreneurship Ecosystem: Four Defining Characteristics. 2011. Available online: http://www.forbes.com/sites/danisenberg/2011/05/25/introducingthe-entrepreneurship-ecosystem-four-defining-characteristics/#1e4fa52e38c4 (accessed on 17 July 2021).

- Feld, B. Startup Communities: Building an Entrepreneurial Ecosystem in Your City; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Vogel, P. The Employment Outlook for Youth: Building Entrepreneurial Ecosystems as a Way Forward. An Essay for the G20 Youth Forum 2013. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2357856 (accessed on 14 July 2021).

- Mason, C.; Brown, R. Entrepreneurial ecosystems and growth oriented entrepreneurship. Background paper prepared for the workshop organised by the OECD LEED Programme and the Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs on Entrepreneurial Ecosystems and Growth Oriented Entrepreneurship. Final Rep. OECD Paris 2013, 30, 77–102. [Google Scholar]

- Ács, Z.J.; Autio, E.; Szerb, L. National Systems of Entrepreneurship: Measurement issues and policy implications. Res. Policy 2014, 43, 476–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stam, E. Entrepreneurial Ecosystems and Regional Policy: A Sympathetic Critique. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2015, 23, 1759–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szerb, L.; Lukovszki, L.; Páger, B.; Varga, A. A Vállalkozás Egyéni és Intézményi Tényezői a Pécsi Városrégióban; Regionális Innováció- és Vállalkozáskutatási Központ: Pécs, Hungary, 2020; Available online: http://open-archive.rkk.hu:8080/jspui/bitstream/11155/2372/1/szerb-rierc-2020.pdf (accessed on 23 May 2022).

- Tóth-Pajor, Á.; Farkas, R. A vállalkozói ökoszisztémák térbeli megjelenésének modellezési lehetőségei–tények és problémák. Közgazdasági Szle. 2017, 64, 123–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megyeri, G. Hogyan segíthetik a távdolgozók a cégek növekedését? Közgazdaság 2020, 15, 73–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goreczky, P. A hazai startup-ökoszisztéma fejlődését meghatározó körülmények nemzetközi összehasonlításban. KKI ELEMZÉSEK 2021, 23, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endrődi-Kovács, V.; Nagy, G.S. A kelet-közép-európai kis-és középvállalkozások versenyképességi környezete az Európai Unióban. Közgazdasági Szle. 2022, 69, 314–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hortoványi, L.; Szabó, Z.R.; Nagy, S.G.; Strukovszky, T. A digitális transzformáció munkahelyekre gyakorolt hatásai. Felkészültek-e a hazai vállalatok a benne rejlő nagy lehetőségre (vagy a veszélyekre)? Külgazdaság 2020, 64, 73–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parliament Office. Vállalkozásvédelmi Intézkedések Járványhelyzetben egyes EU Tagállamokba 2020. Available online: https://www.parlament.hu/documents/10181/25287874/Elemzes_2020_COVID-19_vallalkozasvedelem.pdf/f8df28b7-7757-1709-efa8-482c17402028?t=1600425820799 (accessed on 30 December 2022).

- MKIK GVI. A Koronavírus-Járvány Gazdasági Hatásai a Magyarországi Vállalkozások Körében—ÉRINTETTSÉG és Válságkezelő Intézkedések. 2020. Available online: https://gvi.hu/kutatas/628/a-koronavirus-jarvany-gazdasagi-hatasai-a-magyarorszagi-vallalkozasok-koreben-2020-oktoberig-kapacitaskihasznaltsag-valsagkezelo-eszkozok-bervaltozasok-es-ertekesitesi-arak (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- KPMG. Összefoglaló Állami Támogatásokról. 2020. Available online: https://assets.kpmg/content/dam/kpmg/hu/pdf/szakertoi_anyagok/osszefoglalo-az-allami-tamogatasokrol.pdf (accessed on 13 December 2022).

- Tóth, T. Állami támogatások versenyjoga a vírusválság idején. Európai Tükör 2020, 3, 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.vlada.cz/en/media-centrum/aktualne/measures-adopted-by-the-czech-government-against-coronavirus-180545/#economic (accessed on 15 October 2022).

- Available online: www.slovakstartup.com/2020/04/02/hack-corona-crisis-slovakia-hackathon/ (accessed on 5 May 2021).

- Available online: https://nkfih.gov.hu/covidea (accessed on 15 October 2022).

- Available online: https://itkey.media/200m-pln-for-polish-startups-fighting-the-covid-19-crisis/ (accessed on 15 October 2022).

- European Commission. Applications Welcome from Startups and SMEs with Innovative Solutions to Tackle Coronavirus OUTBREAK. European Commission. 2020. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/news/startups-and-smes-innovative-solutions-welcome-2020-mar-13_en (accessed on 15 April 2021).

- Teddlie, C.; Tashakkori, A. A General Typology of Research Designs Featuring Mixed Methods. Res. Sch. 2006, 13, 12–28. [Google Scholar]

- Cresweell, J.W. Research Design. In Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cresweell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V.L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Teddlie, C.; Tashakkori, A. Foundations of Mixed Methods Research: Integrating Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches in the Social and Behavioral Sciences; Sage Publications Inc.: Thousand Oak, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Visegrad Group. 2023. Available online: http://www.visegradgroup.eu/ (accessed on 5 January 2023).

- Block, J.; Sandner, P. What is the effect of the financial crisis on venture capital financing? Empirical evidence from US Internet start-ups. Ventur. Cap. Int. J. Entrep. Financ. 2009, 11, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldner, F.; Zsifkovits, M.; Heidenberger, K. Emerging Service-Based Business Models in the Music Industry: An Exploratory Survey. In Exploring Services Science. IESS 2012; Lecture Notes in Business Information Processing; Snene, M., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; Volume 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemeny, T.; Nathan, M.; Almeer, B. Using Crunchbase to Explore Innovative Ecosystems in the US and UK; Birmingham Business School Discussion Paper Series; University of Birmingham; Birmingham Business School: Birmingham, UK, 2017; Available online: http://epapers.bham.ac.uk/3051/ (accessed on 20 March 2019).

- Breschi, S.J.; Lassébie, C.; Menon, C. A Portrait of Innovative Start-Ups across Countries (OECD Science, Technology and Industry Working Papers); OECD: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Baneriji, D.; Reimer, T. Startup founders and their LinkedIn connections: Are well-connected entrepreneurs more successful? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 90, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crunchbase. 2020. Available online: www.crunchbase.com (accessed on 4 January 2020).

- Available online: https://kwest.limequery.com/surveyAdministration/view?surveyid=938769 (accessed on 16 December 2021).

- Mann, H.B.; Whitney, D.R. On a test of whether one of two random variables is stochastically larger than the other. Ann. Math. Stat. 1947, 18, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcoxon, F. Some uses of statistics in plant pathology. Biom. Bull. 1945, 1, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kézai, P.K.; Rechnitzer, J. Performance of enterprises in cultural and creative industries in large Hungarian cities between 2008 and 2018. Reg. Stat. 2023, 13, 167–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babbie, E. The Basics of Social Research, 15th ed.; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Holstein, J.A.; Gubrium, J.F. The Active Interview; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995; Volume 37. [Google Scholar]

- Brinkmann, S.; Kvale, S. Interviews. In Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research Interviewing; Sage Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kvale, S. InterViews. In An Introduction to Qualitative Research Interviewing; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Farkas, T. Az Employer Branding Átalakulása a COVID-19 Hatására a Technológiai Iparágakban; Traumatic Marketing: Tokyo, Japan, 2021; p. 154. Available online: http://unipub.lib.uni-corvinus.hu/6811/1/ArielMitev-TamsCsords-DraHorvth-KittiBoros-Post-traumaticmarketingvirtualityandreality.pdf#page=154 (accessed on 2 November 2022).

- Juhász, P.; Szabó, Á. A koronavírus-járvány okozta válság vállalati kockázati térképe az első hullám hazai tapasztalatai alapján. Közgazdasági Szle 2021, 68, 126–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Design Terminal. Startup Crisis Report 2020. Available online: https://designterminal.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/STARTUP-CRISIS-REPORT.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2020).

- Nyikos, G.; Soha, B.; Béres, A. Entrepreneurial resilience and firm performance during the COVID-19 crisis-evidence from Hungary. Reg. Stat. 2021, 11, 29–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szepesi, B.; Pogácsás, P. A Koronavírusjárvány Hatása a Magyar Vállalkozásokra. 2021. Available online: https://ifka.hu/medias/970/akoronavirus-jarvanyhatasaamagyarvallalkozasokra.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2023).

- Sass MGál, Z.; SGubik, A.; Szunomár, Á.; Túry, G. A koronavírus-járvány kezelése a külföldi tulajdonú magyarországi vállalatoknál. Közgazdasági Szle. 2022, 69, 758–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karsai, J. A Kockázati Tőke Gazdaságfejlesztő Hatása Kelet-Közép-Európában. 2021. Available online: https://www.hvca.hu/documents/A_kock%C3%A1zati_t%C5%91ke_fejleszt%C5%91_szerepe_Kelet-K%C3%B6z%C3%A9p-Eur%C3%B3p%C3%A1ban_%281%29.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2022).

- Pisoni, A.; Onetti, A. When startups exit: Comparing strategies in Europe and the USA. J. Bus. Strategy 2018, 39, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sass, M. Jobb Ma Egy Veréb, Mint Holnap Egy Túzok? Alternatív Növekedési Utak Keresése a Visegrádi Országokban; Workshop Studies 137; Centre for Economic and Regional Studies Institute of World: Barcelona, Spain, 2020; pp. 1–70. Available online: https://oszkdk.oszk.hu/storage/00/03/03/55/dd/1/Sass_szerk__m__hely_137_v__gs___pdf.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2022).

- OECD. Innovation and Modernising the Rural Economy, OECD Rural Policy Reviews; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).