Abstract

Building upon the literature’s contribution to organizational procurement, enterprises must confront challenges derived from the uncertainty of collective decision-making and increasing efforts to scan for relevant information among providers. Especially for service products that cannot be tried in advance, how should corporate customers determine the price/performance of products before purchasing? This study explores ways to overcome the effect of these vulnerabilities and advance the quality of service and the loyalty framework to enrich the information processing theory. The results indicate that perceived value and relationship quality have greater effects on loyalty than service quality. Thus, if service providers can maintain amicable relationships and interactions with enterprise users, this will help the vendor provide enterprise users with appropriate product information in their service process, increasing the enterprise users’ loyalty. This study also proposes practical implications for the research results above, providing the information service industry with feasible service model suggestions and maintaining a sustainable competitive advantage. This study addresses relevant challenges faced by practitioners and provides managerial guidance to strengthen customer loyalty.

1. Introduction

There were more than 1.61 million SMEs in Taiwan in 2020 [1], accounting for 98.92% of all enterprises. The output value of the service industry accounted for 62.04% of Taiwan’s GDP that year [2]. Although E-commerce platforms provide sales channels that allow enterprises to exploit more markets, B2B sales still occupied a great deal of business traction sales [3]. Due to the rapid development of global information technology and changes in consumer practices, the electronic products of both consumers and the industry are being updated more rapidly than ever before [4]. This does not influence the service provider, because their goal is to help corporate customers optimize their business model to increase their competitiveness [5]. Therefore, the revenue growth of SMEs in the service industry is an important topic.

Due to the limited resources of SMEs, the expansion of operations should focus on cultivating existing customer relationships to acquire new revenue [6]. The attributes of service products can be divided into two categories: B2C and B2B. However, there are relatively few studies on B2B products. This research hypothesizes that B2B service products will encounter two problems during the repurchasing process:

- It is well known that service quality is a driver of loyalty. Service quality is defined as the customer’s thought gap before and after receiving the service [7], and such a concept is also defined as the consumer’s perception of service value [8]. However, service products cannot be used prior to purchase, so how can the customers judge the service product’s service quality? Which determinants will influence the customers’ purchasing willingness? This study believes that customers judge the service quality of the products based on their past experiences or the information they have access to.

- The organizational procurement process requires the relevant personnel to form a buying center to manage procurements [9]. However, the decisions made by these members are dependent on their existing impressions or received information. Therefore, it is worth discussing how to deliver the appropriate information that makes stakeholders feel comfortable to make a consistent procurement decision.

The above-mentioned problems and phenomena lead to high transaction costs between service providers and corporate customers due to insufficient information and other factors. This is not conducive to the development of long-term competitive advantages for service providers. Therefore, this study will use the information processing theory to explore the relationship between service quality and users’ loyalty to the service providers.

Information processing theory advocates that information exchange, communication, and coordination will be conducted when buying center members make decisions [10]. Scholars pointed out that consumer satisfaction is derived from consumers’ information processing [11]. For example, when enterprise users experience less uncertainty and higher perceived value during the procurement process, they will ultimately go through with the final purchasing decision [12]. In other words, a key factor in generating loyalty is knowing how to promote the generation of perceived value through information processing. However, service products are mainly products with high functional requirements (i.e., company system services) because they cannot be tested by users prior to purchase. Therefore, the service needs of enterprise users are not only personal preferences but are more likely to be departments’ needs.

In accordance with the B2B business model, because service products cannot be tried beforehand, the best marketing method for service providers is to enhance the perceived value for enterprise users through “external information channels”, where users can make decisions that are beneficial to manufacturers. In addition, a high level of service content can promote customer satisfaction and trust [13,14,15]. The more professional the service is, the more information will be provided to customers, establishing a greater sense of trust. In addition, scholars indicated that manufacturers’ commitment to customers helps to establish a benign relationship between them, and can promote consumers’ loyalty to manufacturers in the long run [16]. Therefore, the relationship quality between manufacturers and enterprise users is also likely to be a mediating process between service quality and loyalty.

This study defines this concept as the evaluation of relationship quality and perceived value by the consumer. There are many studies discussing that perceived value and relationship quality are the drivers of loyalty in B2C markets [13,14,17,18], but there is little research on B2B markets. However, B2C research aims to obtain the affirmation of a single consumer, but the B2B sales process may go through the decision-making process of the buying center, and the variables in the process are quite diverse. Therefore, it is crucial that service providers understand how to make customers feel that the service product can bring benefits to their enterprises [12] and can help to create trust between enterprises and providers [19]. Basic on this, this study attempts to use questionnaires to explore the factors that affect corporate clients’ loyalty. Furthermore, scholars have found that the purchasing process of some service products with high knowledge-intensiveness may rely more on external information [5]. Therefore, service providers must provide information to buying center members through appropriate and effective channels. Accordingly, this research also uses questionnaires to explore the sources of information of enterprise users and examines the information process. Based on the above phenomena, this study attempts to apply B2C market theory to the B2B market to explore the relationship between service quality, perceived value, relationship quality, and loyalty from the perspective of information processing theory and discuss the channels of information contact of enterprise users:

- Can service providers promote a positive relationship between service quality and loyalty through information delivery before and during service?

- Is there a correlation between the impact of service quality, perceived value, and relationship quality on consumer loyalty?

- What types of external information channels are trusted by buying center members? Additionally, how do service providers deliver information to facilitate the purchasing decision of buying center members?

This study provides three contributions: first, B2C marketing theory can be applied to the B2B market. The result will enable B2B merchants to expand their business size and helps researchers establish a greater understanding of B2B marketing research. Second, through the research model of this study, it is helpful for researchers to understand the possible benefits of information transmission for service products that do not have trial characteristics, and to expand the application of the information processing theory. Third, this study attempts to explore the sources of information that may affect enterprise users, thereby prompting researchers to understand what information searches enterprise users may conduct in the process of B2B marketing, thereby enriching the application of information processing theory. The above discussion will help researchers better understand how SME service providers maintain a stable source of customers through effective information transmission under the circumstances of limited resources.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Information Search Theory

Information processing theory advocates that information exchange, communication, and coordination will be conducted when organizations make decisions [20]. Scholars believe that the information processing theory is a key factor affecting decision-making [21]. Therefore, the information-processing capability of an organization (whether it can meet the needs of the organization or reduce the uncertainty of decision-making), is an important issue for all organizations [21,22]. In consumers’ information search process, they first attempt to obtain the information necessary for decision-making through their memories before considering external information [23]. Therefore, this study posits that information search behaviors may influence the perceived value of the product from the consumer’s perspective. Bettman [24] maintained that information searches can be categorized as internal and external searches and held that the consumer’s search process is an internal-to-external behavioral pattern. An internal search is a spontaneous search process in the consumer’s memory, and when the consumer realizes that their own information is insufficient to serve as the basis of a purchase decision, the consumer expands their search to include external information; this information can reduce the consumer’s uncertainty.

Moriarty and Spekman [25] distinguished sources of information into 14 items in a commercial/non-commercial and interpersonal/impersonal magic quadrant and stated that the importance a procurer attaches to an information source is affected by the procurement scenario, organizational traits, personal traits of the decision maker, and the procurement process. Finally, Fan and Hwang [5] divided external information channels into four quadrants and 10 items: there are friends, colleagues, industry peers, sales representatives, commercial magazines, exhibitions, professional magazines, the Internet, and news reports. In this study, the classification of information sources was based on Fan and Hwang’s [5] research.

In summary, this study posits that when the members of buying centers are processing information, whether they can obtain accurate messages to make suitable decisions when needed is crucial. Therefore, this study focuses on how potential enterprise customers search for information through external information channels and explores how the service provider facilitates enterprise customers’ loyalty by using information search theory.

2.2. Trends in Organizational Procurement Information Systems and Research Question

Sheth [26] argued that the ultimate goal of organizational procurement is to select one or more suitable suppliers. Kotler et al. [9] defined organizational procurement as an organization’s decision-making process while procuring products and services with the goal of selecting one or more suitable suppliers. Because organizational procurement is a joint decision, the procurement process requires the relevant personnel to form a buying center to manage procurements [9,26]. Members of a buying center include initiators, influencers, deciders, buyers, users, and gatekeepers. The members are always the director of their departments. The interactions and power relations between different roles influence the organization’s procurement decisions [25]. Among them, if the service products faced by the organization are highly knowledge-intensive products, the purchasing decision of the organization will rely more on the collective decision-making of the purchasing center [5]. In other words, if we want to explore the information processing mechanism between the organization’s procurement center and service product manufacturers, it may be appropriate to further focus on the systems integration (SI) industry.

Fan and Hwang [5] argued that the SI industry can be grouped into three categories: industry-specific solutions, computer environment setups, and simple provision of computer products. Because SI requires professional knowledge of the industry in question, management across industries carries a certain level of difficulty. Currently, constructing computer environments is the service most frequently demanded by enterprises.

Thus, the procurement process of information service products faces the uncertainty of collective decision-making, and corporate users pay higher search costs to locate product information because product knowledge is too difficult to understand [27,28]. Scholars pointed out that after the establishment of the buying center, many members often try to actively search for external information based on their own knowledge (for example, check whether there are advertisements, magazines, etc.), in order to find suitable manufacturers [29]. Based on the issue, this study tries to find how the buying center members search for information from external information channels from the perspective of information processing theory, which poses the following research questions (RQ):

RQ: What are the main external information search channels for the buying center’s members?

2.3. Service Quality

Grönroos [30] stated that customers develop expectations of the service quality before receiving a service, and after receiving the service, form perceptions of the service quality. Lehtinen and Lehtinen [31] defined service quality as the quality of the process and the associated results; quality of the process generally refers to the customer’s appraisal while receiving the service, and quality of the results is the overall appraisal after the complete service has been provided. Scholars argued that service quality is measured by the customer, specifically by measuring the difference between their expectations and the actual service provided [7]. Parasuraman et al. [7] conducted a study on the conceptual model of service quality and designed a multi-dimensional research instrument to capture consumer expectations and perceptions of a service in five dimensions, which are tangibles, reliability, responsiveness, assurance, and empathy.

On the basis of the preceding discussion, this study posits that service quality is the key to a business’s success, and as such, is often seen as a critical performance indicator [32]. Therefore, if a user perceives the service quality provided by the vendor to be high, their satisfaction naturally increases; furthermore, their repurchase rate also increases [33]. The service quality in this study was mainly determined by modifying Parasuraman et al.’s [6] scale.

2.4. Loyalty

Egan [34] defined loyalty as a customer’s number of purchases and preference for a specific brand. This type of preference is typically reflected in the customer’s purchasing behaviors and subsequent repurchasing behaviors [35,36]. Therefore, loyalty can be considered the enterprise’s competitive advantage and the main source of sustainable operations [34]. Drake, Gwynne, and Waite [37] further categorized loyalty as cognitive loyalty, affective loyalty, and action loyalty. Oliver [38] expanded on the “cognitive–affective–intent” framework and, in addition to adding behavioral factors to consumers’ purchasing actions, emphasized the inclusion of the concept of loyalty in every stage. According to Oliver [38], the stages of loyalty are cognitive loyalty, affective loyalty, conative loyalty, and action loyalty.

In this study, affective loyalty and conative loyalty are posited to be part of a continuous stage. Therefore, affective loyalty and conative loyalty are regarded as one construct expressed as affective loyalty. In the action loyalty stage, consumers proceed to actual purchasing actions for specific brands and overcome obstacles developed when conducting the purchase. On the basis of Drake et al.’s [37] study and with reference to the preceding discussion, customer loyalty comprises three dimensions: cognitive loyalty, affective loyalty, and action loyalty. The loyalty in this study was mainly determined by modifying Drake et al. [37] and Oliver’s [38] scales.

2.5. Perceived Value

Perceived value is the customer’s overall appraisal of the product—that is, the benefits to the customer after receiving the service [39]. Researchers hold that perceived value is the trade-off relationship between the perceived benefits and expenditure that the consumer develops when purchasing a product [40,41]. Sweeney and Soutar [42] developed the PERVAL scale, which distinguishes perceived value into four components: emotional, social, price, and quality values. Petrick and Backman [43] also proposed the SERV-PERVAL scale, a multidimensional instrument for measuring customers’ perceived value.

This study posits that perceived value is a trade-off relationship between the perceived benefits and perceived sacrifice that the customer develops when they intend to purchase a product. This trade-off is the key factor determining customer loyalty. If the user perceives the vendor as one that provides services with high perceived values, the user naturally prioritizes products provided by that vendor, which increases the enterprise’s loyalty to the vendor. The perceived values in this study were mainly determined by modifying Petrick and Backman [43] and Sweeney and Soutar’s [42] scale.

2.6. Relationship Quality

Relationship quality refers to the overall assessment of the strength of the relationship between the buyer and seller. These are founded on both parties’ past successes and failures [44]. A higher relationship quality leads to increased customer satisfaction with the business and feelings that the business is trustworthy [44]. Therefore, relationship quality is the key to determining whether customers are likely to shift to another business, [45] so determining how to form a long-term partnership through trust with the customer is crucial [46]. Crosby et al. [44] argued that relationship quality should include two factors: trust and satisfaction. Hennig-Thurau and Klee [47] held that relationship quality should have three dimensions: cognition, trust, and satisfaction. Moreover, Itani and Inyang [48] stated that the three dimensions of relationship quality should be satisfaction, trust, and commitment.

In this study, satisfaction, trust, and commitment are regarded as the three dimensions that fully represent relationship quality and affect continued interactions in the future. If an enterprise is satisfied with the interactive relationship with the vendor and feels that the vendor is trustworthy, it will naturally commit to further relations between the two to reduce transactional uncertainties. The enterprise is also likely to prioritize the vendor’s products for their procurement cases. The relationship quality in this study was mainly determined by modifying Itani and Inyang’s [48] scale.

2.7. Hypotheses

On the basis of the aforementioned literature, seven hypotheses were proposed.

Hull [49] considers a service product as an intangible service or a service model that can attach services to tangible products. Many studies have pointed out that most service products have a certain degree of uniqueness, creating higher value for customers [50,51]. However, service quality refers to the fact that customers develop expectations of the service quality prior to receiving a service, and generate perceptions of the service quality after receiving the service [28].

Looking back on past studies, many researchers have found that there are many possible antecedents of loyalty, such as service quality [52,53,54,55], information quality [56,57] and customer trust [58], and other constructs. Aside from the information processing theory, in fact, buying center members conduct information searches based on the existing environment when conducting purchasing activities [21]. Therefore, with respect to service products that cannot be physically tested, it is very important to ensure that customers’ awareness of the service is higher than expected through the transmission of information in the service process. In particular, when a service provider offers service beyond the consumer’s expectations, the consumer’s intention to repurchase in the future increases, resulting in increased customer loyalty [52]. In conclusion, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Service quality has a positive and significant effect on loyalty.

Perceived value is a value assessment based on the benefits people feel that have gained from a product (or service) [59]. Past studies have pointed out that the discovery of perceived value may be a very important construct in marketing research. For example, previous studies have found that service quality [60] may positively affect perceived value; and perceived value will further promote customer trust [58] and loyalty [61].

Jalkala and Keränen [12] believe that enterprise users’ perceived value of service products depends on whether or not the solutions provided by service providers benefit the enterprise. Information processing theory points out that in the information search process of consumers, they will first recall their own internal memories, and then explore external information [23]. When customers receive services, their main source of information will be the manufacturer. Therefore, service providers must be able to deliver accurate information to enterprise users through the service process to ensure positive customer cognition [62]. Then, empirical research has demonstrated that utilitarian value directly affects user behavior [63].

This means that when enterprise users believe that the services given by service providers can create value for them, it increases customer loyalty significantly [59,64]. The information processing viewpoint of Premkumar et al. [21] emphasizes that many buying center members will discuss the value to the organization according to the information clues around them, and finally make procurement decisions. Therefore, this research points out that creating value for customers will be the key factor to enhance consumer loyalty [61].

In summary, this study argues that perceived value can be regarded as a rational judgment of consumers on service products [65]. When buying center members perceive a product as being of higher value, they will naturally prioritize products by the same vendor when making procurement decisions, thus increasing loyalty to that vendor. Therefore, in this study, we can infer the following:

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Service quality has a positive and significant effect on perceived value.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Perceived value has a positive and significant effect on loyalty.

Relationship quality refers to the overall assessment of the strength of the relationship between the buyer and seller and is mainly based on previous successful or unsuccessful encounters between both parties [31]. Previous studies have found that relationship quality can be regarded as a very important construct due to the fact that customer experience has a positive impact on relationship quality [66], which will have a positive impact on repurchase intention and loyalty [67].

Scholars believe that the provision of superb service quality by vendors is beneficial to increasing trust and satisfaction in customers [13], and can promote long-term partnerships between both parties and lower intentions to switch vendors [46]. On the other hand, Alejandro et al. [19] think that the reciprocity between manufacturers and enterprise users helps enterprise users gain more information from manufacturers, which ultimately helps them make purchasing decisions. In addition, some scholars have also found that manufacturers’ commitment to customers helps to establish a benign relationship between the two which promotes consumers’ loyalty [16]. The theory of information processing points out that trust is a very important mechanism in the process of information transmission, which helps to promote the information receiver’s trust in the information around him [21]. Furthermore, the theory also claims that sufficient trust and satisfaction cognition can form a strong signal to maintain a mutual relationship, which is conducive to close cooperation with each other in the long run. Therefore, if the manufacturer can establish the trust of enterprise users through the information transmission mechanism of the service process, it will contribute to the generation of loyalty.

In summary, if service providers can provide good service quality in the service process and pass on the relevant knowledge of products or services to gain the trust of buying center members, it will help their future repurchase intentions. Therefore, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Service quality has a positive and significant effect on relationship quality.

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

Relationship quality has a positive and significant effect on loyalty.

These hypotheses suggest that perceived value and relationship quality should have a mediating effect on the relationship between service quality and loyalty [14,18,68]. Ergo, the following two hypotheses were raised:

Hypothesis 6 (H6).

Perceived value has a mediating effect on the relationship between service quality and loyalty.

Hypothesis 7 (H7).

Relationship quality has a mediating effect on the relationship between service quality and loyalty.

3. Research Methods

3.1. Research Framework

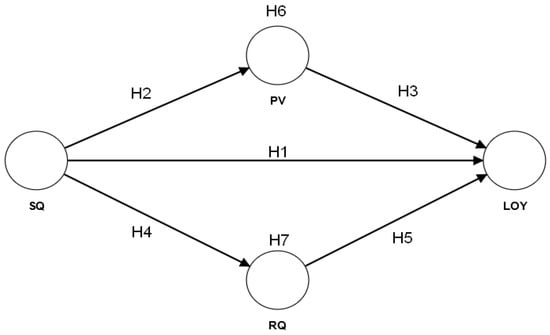

Based on the research question and hypotheses, this study proposes the following research model, as depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research framework. Note: SQ: service quality; PV: perceive value; RQ: relationship quality; LOY: loyalty.

3.2. Questionnaire Samples and Distribution Methods

The purpose of this study is to explore how the processes of purchasing decisions and sources of information influence buying center members when purchasing highly knowledge-intensive service products. Therefore, this research takes buying centers that purchase information service products as the objects of the questionnaire survey. Previous studies have found that the information service industry is a kind of knowledge-intensive industry [27,28], so it is very suitable as the questionnaire survey object of this study. However, considering there is little research on B2B markets, this study conducts a focused interview to determine the questionnaire’s content and distribution method. Since the goals of the focused interview are to confirm the literature review’s conclusion, explore the real procurement processes of buying centers, and clarify the procurement characteristics of SMEs, the study invited three experts with more than 20 years of work experience in the information system integration industry (refer to Table 1 for the background of the respondents). The top three information product buyers in Taiwan are finance, manufacturing, and government, so the three experts separately represent the three industries and are all leading service providers in their respective fields, so their opinions can reflect the real situations of buying centers. The research team will send the interview outline to the interviewees one week before the interview, and the first author and corresponding author will act as the moderators of the focus interview to lead the focus interview for about two hours.

Table 1.

Background information of experts in focus group discussions.

The five conclusions of the focused interview are recounted below:

- Most of the customers who purchase information service products are medium and large enterprises, and their annual repurchase amount is usually below TWD 500 K.

- Regardless of the budget amount, an enterprise will form a buying center for the procurement process, but the number of members depends on the procurement scale. Most members of the buying center are C-level or D-level in their department.The above results are similar to Mattson’s (1988) claim that purchasing managers usually have the final decision on purchasing activities [69].

- When purchasing information system services, members of the buying center need to understand the needs of the requesting department, then search for relevant information to make a purchasing specification.

- When the users encounter a problem with the information system, they begin by asking the IT department for assistance, and the IT department will contact the service provider if they cannot fix it.

- Many of the buying center’s members will consult the service providers to inquire about their opinions during the procurement procedure. The external information channels through which they obtain information are similar to those Fan and Hwang [5] proposed, but use advertisements instead of commercial magazines.

Therefore, this research establishes respondent eligibility through the following terms:

- The members of the buying centers and their titles must be the C-level or D-level of their department.

- The buying center’s information service products must be repeatedly bought and the total amount must be valued over TWD 1000 K in the last 2 years.

3.3. Defining and Measuring Variables

The variables were measured using a 5-point Likert scale, with 1 meaning strongly disagree and 5 meaning strongly agree. The operational definitions and dimensions of each variable are as follows:

Service quality was defined as the discrepancy between the consumer’s actual perceptions after having received a service and their expectations of that service. The survey items were modified from the research of Parasuraman et al. [6] and measured in five dimensions: tangibles, reliability, responsiveness, assurance, and empathy, for a total of 15 questions.

Perceived value was defined as the gap between consumer perception and expenditure. The survey items were modified from the research of Petrick and Backman [43] and Sweeney and Soutar [42] and measured in four dimensions: emotional, social, price, and quality, for a total of 12 questions.

Relationship quality was defined as the degree of satisfaction and trust in the interactive relationship between consumers and vendors. The survey items were modified from the research of Itani and Inyang [48] and measured in three dimensions: satisfaction, trust, and promise, for a total of nine questions.

Loyalty was defined as the degree to which consumers are willing to continue buying products provided by vendors and are willing to recommend them to others. The survey items were modified from the research of Drake et al. [37] and Oliver [38] and measured in three dimensions—cognitive loyalty, affective loyalty, and conative loyalty—for a total of nine questions.

There are 11 information channel variables: 10 external information channel variables and one internal information channel, usage experience, which are defined by the focused interview in order to verify the scholar’s research. The question is the following: “This information channel is important when you search for product information.”

3.4. Questionnaire Sampling

This study was conducted in partnership with a SI firm in Taiwan. Members of the buying centers of enterprises that have purchased professional information services products valued over TWD 1000 K in the preceding 2 years were surveyed through personal visits. The survey was conducted using purposive sampling; respondents that carried out a repeated procurement of a professional service or product in the preceding 2 years and have participated in the decision-making or have been consulted in the procurement process were considered eligible for inclusion. The number of questionnaires is mainly based on the proposition of Tinsley & Tinsley [70], and the number of samples is set to be at least three to five times that of the questionnaire items. In this study, there are a total of 45 items in the questionnaire, so the research team initially set the number of questionnaire samples to at least 225. Finally, due to the buyers of information service products are large and medium-size enterprises, the population size is limited. Thus, 250 questionnaires were distributed to 84 enterprise users, and 198 questionnaires were returned, 167 questionnaires are valid.

The rate of valid return was 84.3%. In total, 76% of the respondents were employed in the information technology (IT) department. This finding may be attributed to the transaction prices of most of the respondent enterprises’ procurement cases being sufficiently low to be decided by IT personnel. In terms of descriptive statistics, the mean value of service quality was 4.05, with a standard deviation (SD) of 1.12; the mean value of perceived value was 3.93 (SD = 1.08), that of relationship quality was 4.05 (SD = 1.14), and that of loyalty was 3.88 (SD = 1.06).

3.5. Survey Reliability and Validity

The data analysis was performed in this study using partial least squares (PLS), that is, Smart PLS 4.08 was used to estimate the research model and analyze the significance of relationships among variables with bootstrapping [71].

PLS analysis is performed in two stages [72]. In the first stage, the outer model is evaluated to understand the reliability and validity of the survey items and constructs. After that, the inner model is evaluated by examining the proposed hypotheses. There are four constructs in the research model, as Figure 1. The recommendations of Straub et al. [73] and Lewis et al. [74] indicated that the outer model should report internal consistency (Cronbach’s α > 0.7), item reliability (item factor loadings > 0.7), composite reliability (>0.8) [75], convergence validity (i.e., average variance extracted, AVE, is greater than 0.5) [76] and discriminate validity.

In PLS analysis, there are three different kinds of outer for discriminant validity. 1. Cross-loading: the factor loading of the survey items in the construct should be larger than the cross-loadings. 2. Fornell and Larcker [76] suggested that if the square root of AVE of the construct is greater than the Pearson correlations of the other structures, then discriminant validity exists. 3. Henseler et al. [77] mentioned that factor loadings are overestimated in PLS analysis and the correlation between the constructs is underestimated, thus causing Fornell and Larcker’s [66] method to be prone to bias. Therefore, it is suggested to divide the average correlation of the survey items in different constructs by the average correlation of the survey items of the construct. If the value is below 0.85, discriminant validity exists. This method is called the Heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT0.85) ratio of correlations [77].

3.6. Outer Model

PLS has enjoyed increasing popularity in recent years because of its ability to model latent constructs under conditions of non-normality in some small to medium-sized samples [74]. There are four latent variables in this study and a total of 167 respondents participated in data collection, which is why PLS is suitable for this study.

3.6.1. Reliability and Convergence Validity

The analysis of the reliability of the survey items revealed Cronbach’s α values for service quality, perceived value, relationship quality, and loyalty to be 0.89, 0.88, 0.90, and 0.84, respectively. Because all the Cronbach’s α values were greater than 0.5 [78], no items were eliminated from these four dimensions. The analysis also indicated that all the measurement variables in this study were reliable.

In this study, after examining the consistency of items under each dimension through Cronbach’s α value, we also examined the composition reliability (Composite Reliability; CR) and Average Variance Extracted (AVE). From the following results, we can see that the CR value of each variable is greater than 0.6, and the AVE is greater than 0.5 [76]. This shows that the internal consistency and convergence validity of each aspect is of a certain level. The details are as follows (please refer to Table 2 and Table 3):

Table 2.

Factor loadings and significant test.

Table 3.

Reliability and convergence validity.

3.6.2. Discriminate Validity

Fornell–Larcker Criterion

The AVE is calculated by averaging the square of the factor loadings of the construct. Fornell and Larcker [76] suggest the square root of the AVE by a construct should be greater than the correlation between the construct and the other construct, as shown in Table 4. Therefore, the model constructs have good discriminant validity.

Table 4.

Fornell and Larcker criterion.

Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT0.85) Ratio of Correlations

The other method of assessing the discriminant validity was the HTMT check, which was conducted to improve the problem of overestimation of factor loadings and underestimation of construct correlation in the PLS analysis. When dividing the average correlation of survey items in different constructs by the average correlation of survey items in a construct, the lower the value, the more significant the discriminant validity. Table 5 shows the results of all HTMT comparisons which are less than 0.85, indicating that there is discriminant validity among the constructs.

Table 5.

HTMT0.85 discriminate validity.

The results of the outer model analysis indicated that all constructs have good reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity. Therefore, the analysis of the inner model can be performed to validate the hypotheses in the study.

3.7. Inner Model

It is necessary to consider whether there is a collinearity problem in the PLS analysis so that the estimation results can be interpreted correctly. PLS provides estimates of the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) of the inner model. Kock and Lynn [79] suggest that if VIF < 3.3, there is no collinearity problem between exogenous variables.

The R2 values of LOY, PV, and RQ are 0.728, 0.510, and 0.578, respectively, from the path significance analysis in Table 6. All R2 values are very high, meaning the model is accurate. Chin [75] suggests that standardized paths should be at least 0.20 and ideally above 0.30 in order to be considered meaningful. In this study, all the paths are larger than 0.3, except SQ → LOY; there is no significance, indicating that the direct effect of the model does not exist.

Table 6.

Path analysis.

Since the R2 value is an indicator of the combined explanatory ability of all the independent variables to the dependent variable, it is not possible to determine each individual contribution of the independent variables. Therefore, the estimation of the effect size f2 needs to be performed [80]. When a particular independent variable is removed from the model, R2 is reduced. The effect size, f2, is calculated by dividing the reduced value by the residual. Cohen [80] proposed that there is a weak effect size if f2 = 0.02–0.15, a medium effect size if f2 = 0.15–0.35, and a large effect size if f2 > 0.35.

Q2 and R2 are similar indices in terms of predictive relevance. However, R2 refers to the explanatory ability of the model sample, while Q2 is the predictive ability of the holdout sample. Q2 uses a blindfolding procedure to perform cross-validation. A value of Q2 closer to 1 indicates a higher predictive relevance. If Q² is positive, it means that the PLS has less error in predicting the outcome than in predicting it with the mean. In this way, PLS provides better predictive performance. In particular, Q2 = 1 for a full model replication, Q2 = 0 for a model replacement with the mean, 0.02 ≤ Q2 < 0.15 for weak predictive relevance, 0.15 ≤ Q2 < 0.35 for moderate predictive relevance, and Q2 ≥ 0.35 for strong predictive relevance.

The path analysis shows that VIF is less than 3.33 [80], Q2 is greater than 0, and R2 for loyalty is 0.728, which is the sustainability explanatory ability. All paths in the model are significant (p < 0.05) except SQ→LOY, which is not significant. Consequently, most of the research hypotheses are supported.

3.8. Indirect Effect Analysis

Baron and Kenny [81] suggest the condition of indirect effect when the following conditions are met: (a) variations in levels of the independent variable significantly account for variations in the presumed mediator(s), (b) variations in the mediator significantly account for variations in the dependent variable, with independence as a control variable.

In this study, the model has two indirect effects: RQ and PV mediate the relationship between SQ and LOY. RQ and PV on SQ are significant, respectively. LOY on RQ and PV is also significant when SQ is the control.

3.9. Common Method Bias

Since this study adopted a self-report questionnaire to collect data for all the response variables, it was appropriate to examine the extent to which common method bias may have compromised the responses.

We applied a post hoc statistical procedure to evaluate the threat of common method bias. We examined the fit of one model in which all indicators were loaded on one factor, and a second model in which all indicators were fully correlated. We compared the common method bias (CMB) ( = 1106.183, df = 170) with the correlated CFA model fit statistics ( = 249.474, df = 164) which showed a significant change in model fit (Δ = 856.709 and Δdf = 6, p <0.001). The results did not indicate a significant common variance problem.

4. Research Results

4.1. Demographics and Descriptive Statistics

Since the strict sampling standard, this study just collected 167 valid questionnaires from C-level and D-level respondents. Based on the focused interview’s conclusion and Mattson’s (1988) research, this study thinks the survey result is a valid generalization of the population [69]. In total, 76% of the respondents were employed in the IT department; this finding may be attributed to the transaction prices of most of the respondent enterprises’ procurement cases being sufficiently low to be decided by IT personnel. In terms of descriptive statistics, the mean value of service quality was 4.05, with a standard deviation (SD) of 1.12; the mean value of perceived value was 3.93 (SD = 1.08), that of relationship quality was 4.05 (SD = 1.14), and that of loyalty was 3.88 (SD = 1.06). Service quality, perceived value, relationship quality, and customer loyalty had Cronbach’s α values of 0.886, 0.884, 0.901, and 0.835, respectively, which were all greater than 0.7, indicating internal consistency among the factor dimensions.

4.2. Level of Exposure of Each Role to External Information Channels

Each role’s level of exposure to external information channels was verified using the Scheffe post hoc test. The results indicated that the Internet, colleagues, sales representatives, professional magazines, industry peers, friends, advertisements, and exhibitions were all significant external information channels. Usage experience is an internal information source, whereas colleagues, industry peers, and friends are interpersonal information sources; these three information sources are difficult for vendors to control. Advertisements or exhibitions did not exhibit as high levels of significance as information sources did, and as such, the procurement decision depended on whether marketing resources were sufficient.

Among the three information sources in which vendors of service products should invest more resources, the Internet and professional magazines are considered impersonal information sources. This means that for vendors of service products, the deployment of sales staff is indispensable, and marketing resources for advertisements should be focused on the Internet and professional magazines. Respondents’ highest level of exposure was from the Internet, followed by usage experience; this also verifies Bettman’s [24] finding that when searching for information about a product, consumers first search for the necessary information in their memory before consulting an information source that they consider trustworthy.

4.3. Hypothesis Testing

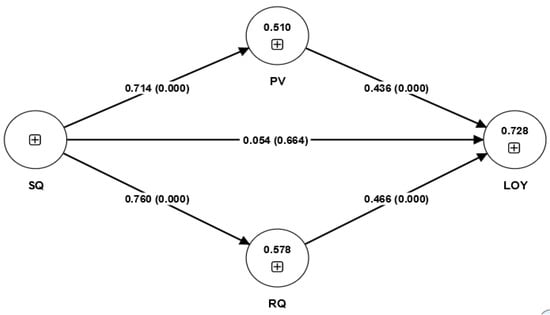

There are a total of seven hypothesis verifications in this study (see Figure 2), which are now divided into two parts. The details are provided below.

Figure 2.

Statistical model (the numbers in parentheses are p values).

4.3.1. Testing the Direct Effects

The test of whether the independent variable has a positive and significant influence on the corresponding variable hierarchical regression was used to test H1-H5 The details are as follows.

H1: Service quality has a positive and significant effect on loyalty. Table 2 indicates that the effect of service quality on loyalty has a β value of 0.054 (p > 0.05). This demonstrates that service quality has no effect on loyalty, and therefore, H1 does not hold.

H2: Service quality has a positive and significant effect on perceived value. Table 2 indicates that the effect of service quality on perceived value has a β value of 0.714 (p < 0.001). This demonstrates that service quality has a positive effect on perceived value, and therefore, H2 holds.

H3: Perceived value has a positive and significant effect on loyalty. Table 2 indicates that the effect of perceived value on loyalty has a β value of 0.760 (p < 0.001). This demonstrates that perceived value has a positive effect on loyalty, and therefore, H3 holds.

H4: Service quality has a positive and significant effect on relationship quality. Table 2 indicates that the effect of service quality on relationship quality has a β value of 0.436 (p < 0.001). This demonstrates that service quality has a positive effect on relationship quality, and therefore, H4 holds.

H5: Relationship quality has a positive and significant effect on loyalty. Table 2 indicates that the effect of relationship quality on loyalty has a β value of 0.466 (p < 0.001). This demonstrates that relationship quality has a positive effect on loyalty, and therefore, H5 holds.

4.3.2. Testing the Mediating Effects

This study will adopt Hayes’s [82] research using bootstrapping to test indirect effects.

Regarding H6, that perceived value has a mediating effect between service quality and loyalty, Table 7 indicates that the mediating effect of service quality through perceived value on loyalty has a β value of 0.312 (p < 0.001). This demonstrates that perceived value partially mediates the relationship between service quality and loyalty. Therefore, H6 is supported.

Table 7.

Indirect effect.

Regarding H7 that relationship quality has a mediating effect between service quality and loyalty, Table 7 indicates that the effect of service quality through relationship quality on loyalty has a β value of 0.354 (p < 0.001). This demonstrates that relationship quality mediates the relationship between service quality and loyalty.

In our model, two specific mediating effects were supported, but the direct effect of service quality on loyalty (H1) was not supported, meaning our model is a full mediation model.

5. Conclusions and Suggestions

5.1. Conclusions

5.1.1. The Service Quality of a Vendor Has Positive Effects on the Perceived Value, and Relationship Quality among Their Corporate Clients; However, the Positive Relationship with Loyalty Is Not Significant

This study found that service quality has positive effects on perceived value and relationship quality, but not on loyalty. This finding is consistent with Ou et al. [13]’s research, that there should be a “process mechanism” in the process of service quality generating loyalty. From the insignificant positive relationship between service quality and loyalty, it can be found that good service quality is the basic procurement requirement of an enterprise, but cannot be a driver of loyalty. Loyalty formation must be based on sufficient information transmission.

5.1.2. Perceived Value and Relationship Quality among Corporate Clients Have Mediating Effects on the Relationship between Service Quality and Loyalty

The results indicated that perceived value and relationship quality have positive effects on loyalty and mediating effects on the relationship between service quality and loyalty. This finding is consistent with Giovanis et al. [14], Jiang et al. [18], and Menon’s [68] research. This finding may be attributed to the fact that most of the respondents are IT personnel and are typically not transferred to other departments. Most of them have built trusting partnerships and relationships with the vendors. It can be seen that for the knowledge-intensive characteristic of service products, it is very important to deliver IT personnel’s positive cognition information of the product’s perceived value through information channels and establish a good relationship through the process. Additionally, information service vendors should release product information that the enterprise user requires to increase the enterprise user’s grasp of the product information, which in turn enhances the perceived value and relationship quality to achieve the positive effect of increased loyalty.

5.1.3. Service Providers Should Provide Information Beneficial to Themselves through Information Search Channels Used by Their Clients

Bettman [24] argued that when searching for information about a product, consumers first search for necessary information in their memory before consulting an information source that they consider trustworthy. This is consistent with the findings of his study. The principal information acquisition sources ordered by trustworthiness to the clients are the Internet, colleagues, and sales representatives. This suggests that vendors should provide sufficient information to their corporate clients through their trusted external information channels to help them understand their products and provide high-quality services, thereby achieving the goal of increasing loyalty.

5.2. Academic Implications

This study uses the information processing theory to explore how corporate customers generate loyalty formation mechanisms. The results show that both perceived value and relationship quality have mediating effects between service quality and loyalty. However, the positive relationship between service quality and loyalty is not significant. Based on the above results, this study has the following academic implications.

First of all, the service provided by the service provider must have a service quality that exceeds the expectations of enterprise users, so that the perceived value and relationship quality of enterprise users to the service provider can be improved. In addition, this study found that in previous research, few scholars have explored the mediating effect of perceived value and the relationship between service quality and loyalty at the same time. This is believed to be because perceived value and relationship quality originate from rational and perceptual consumer decision-making perspectives. However, for non-triable service products, both perceived value and relational quality are important for procurement decisions. Specifically, service providers must continuously deliver information during the service process so that consumers can improve their perceived value, or establish a positive relationship through customers’ evaluation of their services, which can promote the cycle of repeat purchases. In other words, the results of this study revealed that the method by which manufacturers address customers’ concerns through information delivery is very important.

The most important contribution of this study is that H1 was not confirmed. The established hypotheses essentially contain known facts, currently not only reported in professional literature but also taught at universities as part of marketing subjects. Although it would certainly be surprising, the B2B market situation is, in fact, not totally similar to the B2C market. Organizational procurement is a rational decision-making process, and service quality is the basic procurement requirement. If the service product’s service quality cannot meet the purchase acceptance criteria, the buyer will refuse the payment. On the other side, there are many users of a service product, so it’s very difficult to get a unanimous evaluation of service quality. As a result, this study concludes that the B2C market theory cannot be 100% applied to the B2B market.

In summary, the research framework proposed in this study not only expands the application of the information processing mechanism but also proposes a new theoretical perspective on the marketing strategy of service products.

Regarding the mediating effect of perceived value between service quality and loyalty, some scholars have proposed that if manufacturers can influence customers’ perceptions of the benefits of the products they provide, it will help to ensure their continued use in the future [59,65]. Explaining this phenomenon via the information processing theory illustrates that the information that the service providers transmit to the enterprise user through the service process is very important because it plays a key role in the consumer’s expectations. When consumers are unfamiliar with the product they are buying, they tend to evaluate its external attributes before purchasing it [83,84]. However, knowledge of service products is complicated and cannot be experienced by users in advance, therefore, service providers are unable to grasp the perceived value of customers. The results of this study indicate that, if service providers offer customers a good service experience and correct information during the service process, they can prevent the perceived value of corporate customers from being reduced due to excessive expectations.

On the other hand, this study also found that relationship quality has a mediating effect between service quality and loyalty. This is supported by Ou et al. [13], Giovanis et al. [14], and Menon [68]. This means that if the service provider can deliver positive and accurate product information about the provider’s products during the service process, the customer will naturally have a better service experience, establishing long-term mutual trust with the service provider and enhancing the quality of the relationship, thereby improving the enterprise user’s loyalty.

From the perspective of information search, this research proposes two points to explain the enterprise procurement behaviors as below:

- Information processing method of buying center members: When the relationship quality between the staff of the IT department and the service provider is strong, if the company’s information system encounters issues that they cannot resolve themselves, members of the IT department will directly contact the service provider. When the buying center proceeds with procurement, the IT department members will consult the service provider to ask for their opinion. Such interactions not only help to reduce the misunderstandings caused by members of the buying center due to external searches (i.e., Internet inquiries), but also help to increase the chances of repeat purchases of the service provider’s products. In other words, relationship quality helps to promote the information processing path that allows enterprise users to actively interact with the service providers, helping both parties to improve the quality of their relationship and enhancing customer loyalty.

- Internal information dissemination of buying center members: Fan, Hwang, and Lee [28], pointed out that the objective product knowledge of procurement center members is relatively low, coupled with time pressure and other factors. Thus, when they conduct external information searches, they will generally begin by consulting the IT department members’ recommendations to develop product specifications. Therefore, when the service provider establishes a good relationship with the members of the IT department during the service process, it will help the decision-makers of the buying center to obtain information that is beneficial to the service provider, so as to generate repeat purchase intention. Furthermore, if the service provider can provide the correct information to the enterprise users through the correct channel during the process of service delivery, when the customer experiences the service, the experience of the customer will meet their expectations—or even surpass them. This will naturally increase the perceived value. Thus, the quality of the relationship with the service provider will improve due to satisfaction with the service.

Based on the above arguments, this study finds that during service provision, perceived value and relationship quality will be simultaneously embedded in the information processing mechanism of customers.

The former mainly needs to consider how service providers can reduce enterprise users’ false expectations of service quality, which can negatively affect perceived value, by transmitting information beforehand and during the service process. The latter emphasizes that the establishment of relationship quality can reduce the need for enterprise users to search for unnecessary external information so that service providers can deliver the correct knowledge. This will ensure that enterprise users understand the service content, thereby enhancing loyalty. In other words, from the above two mediation effects and the fact that the direct relationship between service quality and loyalty does not hold, it can be found that this study extends the viewpoint of Brown et al. [85] to some extent. The study argues that information processing not only involves a rational decision-making perspective but also includes irrational cognition of service products and service processes. However, the results of this study show that enterprise procurement has a basic service quality acceptance standard for service products; service quality cannot drive loyalty and only contributes through the mediation effect of perceived value and relationship quality.

On the other hand, this study found that enterprise users mainly use the Internet, colleagues, and sales representatives as external information channels when seeking product information. Although there are many studies that found the same results, to some extent, this study further fills the research gap. Fan et al. [29] aimed to explore the extent to which members of the buying center’s knowledge are related to the source of information contact. Moriarty and Spekman [25] and Fan and Hwang’s [5] found that the sources of information contact play a key role in consumers’ purchase intentions. These studies all aim to explore the extent to which members of the buying center’s knowledge is related to the sources and which categories and external information channels they contact, but the studies do not go deep into how the information processing mechanism embeds the perceived value and relationship quality framework to enhance customer loyalty. Therefore, the results of this study help scholars better understand which members of the buying center may request information through external channels, thereby expanding researchers’ understanding of B2B marketing-related fields.

Further focusing on the point of SME’s view, the study pointed out that for information or system service products, the service providers’ service quality can make enterprise users feel positive about the service items through the positive psychological cognition of enterprise users (for example, whether the service content meets their expectations). Satisfaction is very important [86]. Some scholars also argue that if SMEs can promote customer satisfaction with service through service quality, it will help generate greater loyalty [87]. This study explores the relationship between service quality and loyalty through the mediation of perceived value and relationship quality, which extends the viewpoint of Gandhi et al. [87], who have a deeper understanding.

This study found that the main external information channels for most buying center members are the Internet, colleagues, and sales representatives. This means that establishing a good relationship between sales staff and IT department personnel is very important because vendors can lead the sales staff’s behavior. Such results also bring forward new discoveries for B2B service product sales and further enable researchers to establish a deeper understanding of the information transmission process of B2B sales.

All in all, the research contributions of this study are as follows: 1. Breaking down the past argument that service quality can directly affect loyalty because the theory may not apply in the B2B market. 2. The study explores the mediating effect of perceived value and relationship quality between service quality and loyalty, providing new arguments for information processing mechanisms and related research on service product marketing. 3. The study uses the information processing mechanism to explore how service providers transmit information to promote the improvement of perceived value and relationship quality, thereby generating customer loyalty. 4. Service providers should interact with members of the buying center when providing services to deliver information that is beneficial to itself and transmit it to corporate users, thereby enhancing loyalty. 5. Learn more about the sources of information that enterprise users may contact before choosing information service products. Discuss information sources and research hypotheses from information processing theory to help understand how SMEs can make users feel good about service and generate loyalty under the condition of limited resources.

5.3. Practical Implications

The main finding of this study is that service quality can promote loyalty only through perceived value and relationship quality. Among them, the mediating effect of relationship quality is more obvious. It implies that SMEs should pay more attention to the establishment of relationship quality in addition to working on good work processes to promote competitive advantages [88]. In light of this fact, the following suggestions for management practices are proposed:

Vendors should use sales staff to provide useful information about the company’s products and improve the relationship quality. When deciding to procure products, customers value relationship quality over service quality and perceived value. This is because the IT department is a technical department within an enterprise, and IT staff typically remain in the IT department throughout their career, developing relationships of mutual trust with vendors on whom they rely for professional services. Thus, vendors that provide a service should consider how their sales staff can gain the trust of enterprise users during the organization’s purchasing process through the disclosure of useful information, thus increasing loyalty.

On the other hand, the results show that perceived value and relationship quality have a mediating effect on the relationship between service quality and loyalty. This means that information delivery can help enterprise users to acquire an accurate understanding of the quality of the services they have received so that they can continue to use the service based on their positive experience cognition and their trust in the service provider. Therefore, service providers must consider how they serve content. Service providers can implement mentorship within their companies to enhance communication with customers [60]. Specifically, the former is mainly responsible for business contact and communication; the latter is responsible for complicated troubleshooting and establishing an information system plan. In this way, the process of delivering correct and positive information to customers will increase customers’ perceived value and relationship quality, as well as increase the likelihood of repeated purchasing in the future.

Furthermore, this study found that enterprise users mainly use the Internet, colleagues, and sales representatives as external information channels when seeking product information. The above results mean that members of the buying center may begin by searching for relevant information on the Internet in the early stage of procurement, and then discuss the issue with colleagues with relevant backgrounds in the company (for example, personnel in the IT department). When personnel in the IT department face uncertainty, confirmation will be sought from the service providers. In conclusion, service providers must maintain a good relationship with the members of the buying center and provide positive information frequently, so they can generate positive perceived value and quality relationships, which generate loyalty. This is why IBM, the world’s largest B2B information service provider, has developed a set of SSM (Signature Selling Methodology) B2B sales kits for their salesmen. These sales kits are applied to the sales work of a Taiwanese bank through a Taiwanese information service provider [53,89]. It is a pity that these sales are only one-time transactions and not repeat purchases.

In the process of communicating with the IT department, can the service provider try to analyze the advantages that will be provided to the service with the information system from the IT department? What are the benefits for enterprise customers? Additionally, would teaching the IT department personnel how to use the service provider’s services optimize the IT department’s process? All in all, if the IT department personnel can gain an in-depth understanding of the service provider’s services and the benefits to its department and companies, it will help them gain the trust of the organization’s buying center and maintain a long-term competitive advantage.

In summary, this study argues that, while service quality remains the foundation for vendors maintaining their long-term competitive edge, understanding the main search pathways used by clients is likely to increase the value perceived by existing enterprise users, increasing potential clients’ understanding of professional service vendors. Moreover, the cultivation of long-term relationship quality helps vendors rapidly understand their clients’ problems, thereby increasing customer trust and satisfaction, which in turn helps increase loyalty. Therefore, perceived value and relationship quality play key roles in the relationship between service quality and loyalty, and whether a vendor can gain insight into their users’ information search behaviors is the key factor that affects future procurement performance.

5.4. Research Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study investigated the relationships between service quality, perceived value, relationship quality, and loyalty observed among the respondents, who are the buying center members when they procure service products. The concrete management implications proposed in this study are based on the information search intentions adopted by procurement personnel when faced with organizational decision-making, which was explored using the characteristics of information search behaviors. Therefore, the current results may not necessarily apply to other types of service industries. For example: If the results of this study are applied to service products with relatively low knowledge intensity (for example, the tourism service industry), it may not be applicable. Because the knowledge threshold of the tourism service industry is not as high as that of the information service industry, the degree of influence on the information processing process between sales personnel and customers may not be as direct, and customers are more likely to choose services based on their past understanding of the tourism industry. In other words, if the research results of this study are to be applied to service products with relatively low knowledge intensity, they should be used with caution.

Furthermore, in this study, the correlations were mainly explored using quantitative research methods; therefore, the current study cannot determine the real underlying causes of the correlations. Future studies can further use qualitative research, which is conducted on the buying center of various enterprises to investigate procurement phenomena and the reasons behind them.

This research aims to explore the information processing interaction between service product providers and buying centers. Since the information service industry with high degrees of knowledge-intensive products and corporate clients is limited, this results in a low number of effective samples. Although some studies have suggested that small sample data can be solved through SMART PLUS software [90]. Recently, some researchers have also used this method to deal with fewer samples [91]. However, when the number of samples is insufficient, many potential problems will indeed be extended. Furthermore, it is indeed difficult to avoid the specific impact on the research results due to the characteristics of the industry by only focusing on specific industries for questionnaire distribution. Therefore, researchers are advised to use the research results with caution.

Finally, since this study found that the organization’s procurement process is likely to be affected by rational and irrational phenomena during the research process, it is suggested that future researchers can do further research on this part. Specifically, researchers can try to use decision-making theory to explore how buying centers make purchasing decisions, so as to make further academic contributions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.-Y.F. and S.-D.T.; Data curation, T.-Y.F., B.-Y.P. and S.-D.T.; Formal analysis, B.-Y.P.; Methodology, T.-Y.F. and B.-Y.P.; Project administration, T.-Y.F. and L.-P.C.; Writing—original draft, T.-Y.F., B.-Y.P., S.-D.T. and L.-P.C.; Writing—review and editing, T.-Y.F., B.-Y.P. and L.-P.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ministry of Economic Affairs, ROC. 2022 Special Issue on the Achievements of the Ministry of Economic Affairs in Guiding Small and Medium-sized Enterprise. Available online: https://book.moeasmea.gov.tw/book/doc_detail.jsp?pub_SerialNo=2022A01686&click=2022A01686 (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- Chen, P.F. The Output Value of the Service Industry Is Approaching 12 Trillion. Commercial Times. Available online: https://www.chinatimes.com/newspapers/20211201000156-260210?chdtv (accessed on 11 July 2022).

- Zhang, X.; Chen, H.; Liu, Z. Operation strategy in an E-commerce platform supply chain: Whether and how to introduce live streaming services? Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2022, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.M.; Li, Q.W.; Liu, Z.; Chang, C.T. Optimal pricing and remanufacturing mode in a closed-loop supply chain of WEEE under government fund policy. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 151, 106951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, T.Y.; Hwang, I.S. A study on information searching behavior of organization service buying. Web J. Chin. Manag. Rev. 2014, 17, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Gallo, A. The Value of Keeping the Right Customers, Harvard Business Review. Available online: https://hbr.org/2014/10/the-value-of-keeping-the-right-customers (accessed on 11 January 2023).

- Parasuraman, A.; Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L. SERVOUAL: A multiple–item scale for measuring consumer perception of service quality. J. Retail. 1988, 64, 12–40. [Google Scholar]

- Faraj, K.M.; Faeq, D.K.; Abdulla, D.F.; Ali, B.J.; Sadq, Z.M. Total Quality Management And Hotel Employee Creative Performance: The Mediation Role Of Job Embeddedment. J. Contemp. Issues Bus. Gov. 2021, 27, 3838–3855. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, P.; Keller, K.L.; Ang, S.H.; Tan, C.T.; Leong, S.M. Marketing Management—An Asian Perspective, 3rd ed.; Prentice Hall: Singapore, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.J.; Hernandez, M.D.; Minor, M.S. Web aesthetics effects on perceived online service quality and satisfaction in an e-tail environment: The moderating role of purchase task. J. Bus. Res. 2010, 63, 935–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, T.A. Relationship Governance Perspective of Organizational Buyers’ Supplier Choice Decisions. J. Relatsh. Mark. 2017, 16, 328–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalkala, A.M.; Keränen, J. Brand positioning strategies for industrial firms providing customer solutions. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2014, 29, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, W.M.; Shih, C.M.; Chen, C.Y.; Wang, K.C. Relationship among customer loyalty programs, service quality, relationship quality and loyalty: An empirical study. Chin. Manag. Stud. 2011, 5, 194–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovanis, A.; Athanasopoulou, P.; Tsoukatos, E. The role of service fairness in the service quality–relationship quality–customer loyalty chain: An empirical study. J. Serv. Theory Pract. 2015, 25, 744–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, C.G.Q.; Wen, B.; Ouyang, Z. Developing relationship quality in economy hotels: The role of perceived justice, service quality, and commercial friendship. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2020, 29, 1027–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menidjel, C.; Bilgihan, A.; Benhabib, A. Exploring the impact of personality traits on perceived relationship investment, relationship quality, and loyalty in the retail industry. Int. Rev. Retail. Distrib. Consum. Res. 2021, 31, 106–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edward, M.; George, B.P.; Sarkar, S.K. The impact of switching costs upon the service quality–perceived value–customer satisfaction–service loyalty chain: A study in the context of cellular services in India. Serv. Mark. Q. 2010, 31, 151–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Jun, M.; Yang, Z. Customer-perceived value and loyalty: How do key service quality dimensions matter in the context of B2C e-commerce? Serv. Bus. 2016, 10, 301–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alejandro, T.B.; Kowalkowski, C.; Ritter, J.G.D.S.F.; Marchetti, R.Z.; Prado, P.H. Information search in complex industrial buying: Empirical evidence from Brazil. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2011, 40, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbraith, J.R. Organization Design; Addison-Wesley Publishing Company: Boston, MA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Premkumar, G.; Ramamurthy, K.; Saunders, C.S. Information processing view of organizations: An exploratory examination of fit in the context of interorganizational relationships. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2005, 2, 257–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlikowski, W.J.; Robey, D. Information technology and the structuring of organizations. Inf. Syst. Res. 1991, 2, 143–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellish, H. From information science to informatics: A terminological investigation. J. Librariansh. 1972, 4, 157–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettman, J.R. An Information Processing Theory of Consumer Choice; Addison–Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Moriarty, R.T., Jr.; Spekman, R.E. An empirical investigation of the information sources used during the industrial buying process. J. Mark. Res. 1984, 21, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, J.N. A model of industrial buyer behavior. J. Mark. 1973, 37, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- den Hertog, P. Knowledge–intensive business services as co–producers of innovation. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2000, 4, 491–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, T.S.; Yu, Y. Online buying behavior: A transaction cost economics perspective. Omega 2005, 33, 451–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, T.Y.; Hwang, I.S.; Lee, H.M. The Effects of Product Knowledge and Purchasing Involvement on Buyer Center Members’ Pre-purchasing Information Searching Behavior. Soochow J. Econ. Bus. 2011, 72, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Grönroos, C. A service quality model and its marketing implications. Eur. J. Mark. 1984, 18, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehtinen, U.; Lehtinen, J.R. Two approaches to service quality dimensions. Serv. Ind. J. 1991, 11, 287–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A.; Parasuraman, A.; Malhotra, A. Service quality delivery through web sites: A critical review of extant knowledge. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2002, 30, 362–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jen, W.; Hu, K.C. Application of perceived value model to identify factors affecting passengers’ repurchase intentions on city bus: A case of the Taipei metropolitan area. Transportation 2003, 30, 307–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egan, J. Relationship Marketing: Exploring Relational Strategies in Marketing, 2nd ed.; Prentice Hall: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, G.F.; Beck, J.T.; Henderson, C.M.; Palmatier, R.W. Building, measuring, and profiting from customer loyalty. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 790–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stading, G.L.; Johnson, M. An examination of the relationship between a firm’s offerings and different customer loyalty segments. J. Bus-Bus. Mark. 2012, 19, 367–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drake, C.; Gwynne, A.; Waite, N. Barclays life: Customer satisfaction and loyalty tracking survey. Int. J. Bank Mark. 1998, 16, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. Whence consumer loyalty? J. Mark. 1999, 63, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellier, P.K.; Geursen, G.M.; Carr, R.A.; Rickard, J.A. Customer repurchase intention: A general structural equation model. Eur. J. Mark. 2003, 37, 1762–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]